William Ros, 6th Baron Ros on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Ros, 6th Baron Ros (c. 1370 – 1 November 1414) was a medieval English

William Ros, 6th Baron Ros (c. 1370 – 1 November 1414) was a medieval English

John of Gaunt—the most powerful noble in the country and second only to the crown in wealth—died in February 1399. Bolingbroke and King Richard had fallen out the previous year, and Richard had exiled Bolingbroke for six years the previous September. Instead of allowing Bolingbroke to succeed to his father's estates and titles, says Given-Wilson, Richard "succumb dto the temptation" to confiscate the Duchy of Lancaster. Richard proclaimed that Bolingbroke's exile was now a life sentence, and cancelled his writs of seisin. He further decreed that Bolingbroke could only request his inheritance at the

John of Gaunt—the most powerful noble in the country and second only to the crown in wealth—died in February 1399. Bolingbroke and King Richard had fallen out the previous year, and Richard had exiled Bolingbroke for six years the previous September. Instead of allowing Bolingbroke to succeed to his father's estates and titles, says Given-Wilson, Richard "succumb dto the temptation" to confiscate the Duchy of Lancaster. Richard proclaimed that Bolingbroke's exile was now a life sentence, and cancelled his writs of seisin. He further decreed that Bolingbroke could only request his inheritance at the

For the duration of Henry's reign, Ros was "high in the King's confidence and enjoyed especially trusted positions". The historian Mark Arvanigian summarises Ros's position as "clearly a reliable and trusted servant, as well as being a reasonably talented administrator and royal councillor". Henry continued relying on loans to carry out policy, and Ros's loan funded the Calais garrison. Unlike many—and indicating the favour with which the King held him in—Ros was promised repayment, manifested in the royal patronage he continued to receive. By 1409, for example, he had been appointed to the lucrative positions of master forester and constable of

For the duration of Henry's reign, Ros was "high in the King's confidence and enjoyed especially trusted positions". The historian Mark Arvanigian summarises Ros's position as "clearly a reliable and trusted servant, as well as being a reasonably talented administrator and royal councillor". Henry continued relying on loans to carry out policy, and Ros's loan funded the Calais garrison. Unlike many—and indicating the favour with which the King held him in—Ros was promised repayment, manifested in the royal patronage he continued to receive. By 1409, for example, he had been appointed to the lucrative positions of master forester and constable of

Despite his aptitude for dispute resolution, Ros was not exempt from local conflict. He became involved in a dispute with his Lincolnshire neighbour, Sir Robert Tirwhit, in 1411. Tirwhit was a newly appointed royal justice and a well-known figure in the county. He and Ros fell out over conflicting claims to common grazing and associated hay-mowing and turf-digging rights in

Despite his aptitude for dispute resolution, Ros was not exempt from local conflict. He became involved in a dispute with his Lincolnshire neighbour, Sir Robert Tirwhit, in 1411. Tirwhit was a newly appointed royal justice and a well-known figure in the county. He and Ros fell out over conflicting claims to common grazing and associated hay-mowing and turf-digging rights in

William Ros, 6th Baron Ros (c. 1370 – 1 November 1414) was a medieval English

William Ros, 6th Baron Ros (c. 1370 – 1 November 1414) was a medieval English nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

, politician and soldier. The second son of Thomas Ros, 4th Baron Ros

Thomas Ros, 4th Baron Ros of Helmsley (13 January 1335 – 8 June 1384) was the son of William Ros, 2nd Baron Ros and Margery de Badlesmere.

In 1364, he accompanied the king of Cyprus to the Holy Land; and was in the French wars, from 1369 to 1 ...

and Beatrice Stafford, William inherited his father's barony Barony may refer to:

* Barony, the peerage, office of, or territory held by a baron

* Barony, the title and land held in fealty by a feudal baron

* Barony (county division), a type of administrative or geographical division in parts of the British ...

and estates (with extensive lands centred on Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

) in 1394. He married Margaret, daughter of Baron Fitzalan

The title Baron FitzAlan has been created either once or twice in the Peerage of England.

1295 creation

The first creation was in 1295, when Bryan FitzAlan, Lord FitzAlan was summoned to Parliament as Lord FitzAlan. On his death in 1306, the ...

, shortly afterwards. The Fitzalan family, like that of Ros, was well-connected at the local and national level. They were implacably opposed to King Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

, and this may have soured Richard's opinion of the young Ros.

The late 14th century was a period of political crisis in England. Richard II confiscated the estates of his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of Fran ...

, Duke of Lancaster

The Dukedom of Lancaster is an English peerage merged into the crown. It was created three times in the Middle Ages, but finally merged in the Crown when Henry V succeeded to the throne in 1413. Despite the extinction of the dukedom the title h ...

, in 1399 and exiled him. Bolingbroke invaded England several months later, and Ros took his side almost immediately. Richard's support had deserted him; Ros was alongside Henry when Richard surrendered his throne to the invader, becoming King Henry IV, and later voted in the House of Lords for the former king's imprisonment. Ros benefited from the new Lancastrian regime, achieving far more than he had ever done under Richard. He became an important aide and counsellor to King Henry and regularly spoke for him in parliament. He also supported Henry in his military campaigns, participating in the invasion of Scotland in 1400 and assisting in the suppression of Richard Scrope, Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

's rebellion five years later.

In return for his loyalty to the new regime, Ros received extensive royal patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

. This included lands, grants, wardships and the right to arrange the wards' marriages. Ros performed valuable service as an adviser and ambassador (perhaps most importantly to Henry, who was often in a state of near-penury; Ros was a wealthy man, and regularly loaned the crown large amounts of money). Important as he was in government and the regions, Ros was unable to avoid the tumultuous regional conflicts and feuds which were rife at this time. In 1411 he was involved in a land dispute with a powerful Lincolnshire neighbour, and narrowly escaped an ambush; he sought—and received—redress in parliament. Partly because of Ros's restraint in not seeking the severe penalties available to him, he was described by a twentieth-century historian as a particularly wise and forbearing figure for his time.

King Henry IV died in 1413. Ros did not long survive him, and played only a minor role in government during the last year of his life. He may have been out of favour with the new king, Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

. Henry—as Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

—had fallen out with his father a few years before, and Ros had supported King Henry over his son. William Ros died in Belvoir Castle

Belvoir Castle ( ) is a faux historic castle and stately home in Leicestershire, England, situated west of the town of Grantham and northeast of Melton Mowbray. The Castle was first built immediately after the Norman Conquest of 1066 an ...

on 1 November 1414. His wife survived him by twenty-four years; his son and heir, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, was still a minor

Minor may refer to:

* Minor (law), a person under the age of certain legal activities.

** A person who has not reached the age of majority

* Academic minor, a secondary field of study in undergraduate education

Music theory

*Minor chord

** Barb ...

. John later fought at Agincourt in 1415, and died childless in France in 1421. The Barony of Ros was then inherited by William's second son, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

, who also died in military service in France seven years after his brother.

Background and career under Richard II

The exact date of William Ros's birth is unknown. He was described in 1394 as about twenty-three years old, which would place his birth year around 1370. The Ros family was an important one inLincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

and Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, and the historian Chris Given-Wilson

Chris Given-Wilson (born 1949) is a British historian and academic, specialising in medieval history. He was Professor of History of the University of St Andrews, where he is now professor emeritus. He is the author of a number of books.

Car ...

has described them as one of the greatest fourteenth-century baronial families to never receive an earldom. Ros's father was Thomas Ros, 4th Baron Ros

Thomas Ros, 4th Baron Ros of Helmsley (13 January 1335 – 8 June 1384) was the son of William Ros, 2nd Baron Ros and Margery de Badlesmere.

In 1364, he accompanied the king of Cyprus to the Holy Land; and was in the French wars, from 1369 to 1 ...

, who fought in the Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of England and France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French throne between the English House of Plantagen ...

under Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

(particularly in the Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglomerat ...

campaign of 1356). Several years before William's birth, King Edward instructed Thomas Ros to remain with his army on his Irish estates "to prevent the loss and destruction of the country". Thomas married Beatrice, the widow of Maurice Fitzgerald, Earl of Desmond and daughter of the first Earl of Stafford. He died in Uffington, Lincolnshire

Uffington is a village and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 686. It is in the valley of the River Welland, between Stamford and The Deepings.

Geo ...

in June 1384, and his eldest son John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

—William's elder brother—inherited the title as fifth Baron Ros.

Ros also had two younger brothers, Robert and Thomas, "of whom nothing is known". John's career was brief. By 1382 he had married Mary, half-sister of the Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

. John fought for the new king, Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

(heir of Edward III, who died in 1377), in the 1385–86 Scottish campaign and with the Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The e ...

in France the following year. During the early 1390s, John made a pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

to Jerusalem; he died in Paphos

Paphos ( el, Πάφος ; tr, Baf) is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and New Paphos.

The current city of Pap ...

on 6 August 1393, on his return journey to England. John and Mary had not produced an heir, and (although he was never expected to succeed to the barony) Ros was next in line. He inherited as sixth Baron Ros, by which time he had been knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

and appointed to the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

.

Inheritance and marriage

The Ros estates were primarily in the east and north of England. William receivedlivery

A livery is an identifying design, such as a uniform, ornament, symbol or insignia that designates ownership or affiliation, often found on an individual or vehicle. Livery will often have elements of the heraldry relating to the individual or ...

of them in January 1384, which gave him an extensive sphere of influence around Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The traditi ...

, and eastern Yorkshire. By this time, the estate had two dowager

A dowager is a widow or widower who holds a title or property—a "dower"—derived from her or his deceased spouse. As an adjective, ''dowager'' usually appears in association with monarchy, monarchical and aristocracy, aristocratic Title#Aristocr ...

baronesses to support: his deceased brother's wife Mary and their mother, Beatrice. Mary died within a year of her husband, and her extensive inheritance was divided among her Percy relations. Ros received her dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law.

...

lands, which included the ancient Barony of Helmsley Barony may refer to:

* Barony, the peerage, office of, or territory held by a baron

* Barony, the title and land held in fealty by a feudal baron

* Barony (county division), a type of administrative or geographical division in parts of the British ...

. Beatrice, on the other hand, had outlived three husbands and would outlive William; she was assigned her dower lands in December 1384. This meant that Ros would never hold a large swath of land, predominantly in the East Riding of Yorkshire

The East Riding of Yorkshire, or simply East Riding or East Yorkshire, is a ceremonial county and unitary authority area in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and west, South Yorkshire to t ...

.

Ros received ''seisin Seisin (or seizin) denotes the legal possession of a feudal fiefdom or fee, that is to say an estate in land. It was used in the form of "the son and heir of X has obtained seisin of his inheritance", and thus is effectively a term concerned with co ...

'' of his estates on 11 February 1394, which included custody of several Clifford family

Baron de Clifford is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1299 for Robert de Clifford (''c.''1274–1314), feudal baron of Clifford in Herefordshire, feudal baron of Skipton in Yorkshire and feudal baron of Appleby in Westmo ...

estates; his sister had married Thomas de Clifford, 6th Baron de Clifford

Thomas de Clifford, 6th Baron de Clifford, also 6th Lord of Skipton (c. 1363 – 1391) was a Knight of The Chamber, hereditary Sheriff of Westmorland, Governor of Carlisle Castle, and Warden of the West Marches.

Life

He was the son of Roger d ...

around 1379. He held the latter lands until their son

''Their Son'' (also known as ''Sensation im Wintergarten'') is a 1929 silent film directed by Gennaro Righelli.

Synopsis

The son of the Countess Mensdorf runs away when he can no longer stand her relationship with the Baron Von Mallock. The son ...

came of age around 1411. Ros married Margaret, daughter of John Fitzalan, 1st Baron Arundel

John Fitzalan, 1st Baron Arundel (c. 1348 – 1379), also known as Sir John Arundel, was an English soldier.

Lineage

He was born in Etchingham, Sussex, England to Richard Fitzalan, 3rd Earl of Arundel (c. 1313 – 1376), and his second wife ...

and Eleanor Maltravers

Eleanor Maltravers, or Mautravers, ( 1345 – January 1405) was an English noblewoman. The granddaughter and eventual heiress of the first Baron Maltravers, she married two barons in succession and passed her grandfather's title to her grandson. ...

, soon after he inherited. She was already in receipt of a 40-mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Fi ...

annuity

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals.Kellison, Stephen G. (1970). ''The Theory of Interest''. Homewood, Illinois: Richard D. Irwin, Inc. p. 45 Examples of annuities are regular deposits to a savings account, mo ...

from King Richard II because she had been in the household

A household consists of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling. It may be of a single family or another type of person group. The household is the basic unit of analysis in many social, microeconomic and government models, and is im ...

of Richard's recently deceased queen, Anne of Bohemia

Anne of Bohemia (11 May 1366 – 7 June 1394), also known as Anne of Luxembourg, was Queen of England as the first wife of King Richard II. A member of the House of Luxembourg, she was the eldest daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and ...

. His wife gave Ros what may have appeared to be a useful connection to the crown. Also useful to William was the fact that his wife's father had recently died, so Ros now had the Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The e ...

as a brother-in-law. His new connections and the higher political profile they brought may account for the royal grants he soon received of Clifford manors in Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Worcestershire. These had been the dower lands of Euphemia (widow of Robert, Lord Clifford), who had died in November 1393. Ros attended the king's wedding to his second wife—the French King's daughter, Isabella of Valois

Isabella of France (9 November 1389 – 13 September 1409) was Queen of England as the wife of Richard II, King of England between 1396 and 1399, and Duchess (consort) of Orléans as the wife of Charles, Duke of Orléans from 1406 until her ...

—in Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

in December 1396. His wife's grandfather died the following year, and she became Lady Maltravers ''suo jure

''Suo jure'' is a Latin phrase, used in English to mean 'in his own right' or 'in her own right'. In most nobility-related contexts, it means 'in her own right', since in those situations the phrase is normally used of women; in practice, especi ...

''.

Although Ros received some royal favour, Charles Ross has suggested that he may not have been doing as well as expected for a man in his position. Ross suggests that William's Fitzalan connections might have worked against him with the king. Arundel was a staunch political opponent of Richard's, and Ros's marrying into this politically unpopular family may account for the few offices the king granted him. "It seems strange", says Ross, "that a wealthy young lord, who later proved himself both active and able in the royal service, had no public, and very little local employment during the later years of Richard II". Ros's situation would not change until the accession of Arundel's political ally, Henry Bolingbroke

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of Fran ...

, as King Henry IV in 1399. He was rarely appointed to peace commissions and did not sit on many ''oyer and Terminer

In English law, oyer and terminer (; a partial translation of the Anglo-French ''oyer et terminer'', which literally means "to hear and to determine") was one of the commissions by which a judge of assize sat. Apart from its Law French name, the ...

'' arrays, even in his own counties.

Regime change and career under Henry IV

John of Gaunt—the most powerful noble in the country and second only to the crown in wealth—died in February 1399. Bolingbroke and King Richard had fallen out the previous year, and Richard had exiled Bolingbroke for six years the previous September. Instead of allowing Bolingbroke to succeed to his father's estates and titles, says Given-Wilson, Richard "succumb dto the temptation" to confiscate the Duchy of Lancaster. Richard proclaimed that Bolingbroke's exile was now a life sentence, and cancelled his writs of seisin. He further decreed that Bolingbroke could only request his inheritance at the

John of Gaunt—the most powerful noble in the country and second only to the crown in wealth—died in February 1399. Bolingbroke and King Richard had fallen out the previous year, and Richard had exiled Bolingbroke for six years the previous September. Instead of allowing Bolingbroke to succeed to his father's estates and titles, says Given-Wilson, Richard "succumb dto the temptation" to confiscate the Duchy of Lancaster. Richard proclaimed that Bolingbroke's exile was now a life sentence, and cancelled his writs of seisin. He further decreed that Bolingbroke could only request his inheritance at the king's pleasure

At His Majesty's pleasure (sometimes abbreviated to King's pleasure or, when the reigning monarch is female, at Her Majesty's pleasure or Queen's pleasure) is a legal term of art referring to the indeterminate or undetermined length of service of c ...

. Bolingbroke, in Paris, joined forces with the also-exiled Thomas Arundel

Thomas Arundel (1353 – 19 February 1414) was an English clergyman who served as Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of York during the reign of Richard II, as well as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1397 and from 1399 until his death, an outspoken o ...

. Arundel had been Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, and was Ros's wife's uncle; he lost his office because of his involvement with the Lords Appellant

The Lords Appellant were a group of nobles in the reign of King Richard II, who, in 1388, sought to impeach some five of the King's favourites in order to restrain what was seen as tyrannical and capricious rule. The word ''appellant'' — still u ...

, and been exiled since 1397. With Arundel and a small group of followers, Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspur

Ravenspurn was a town in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, which was lost due to coastal erosion, one of more than 30 along the Holderness Coast which have been lost to the North Sea since the 19th century. The town was located close to the ...

in Yorkshire in late June 1399. Ros, bringing a large retinue

A retinue is a body of persons "retained" in the service of a noble, royal personage, or dignitary; a ''suite'' (French "what follows") of retainers.

Etymology

The word, recorded in English since circa 1375, stems from Old French ''retenue'', it ...

, joined Bolingbroke's army almost immediately (as did much of the northern nobility). Richard was campaigning in Ireland at the time, and unable to defend his throne. Henry initially announced that he intended only to reclaim his rights as Duke of Lancaster

The Dukedom of Lancaster is an English peerage merged into the crown. It was created three times in the Middle Ages, but finally merged in the Crown when Henry V succeeded to the throne in 1413. Despite the extinction of the dukedom the title h ...

, although he quickly gained enough power and support (including that of Ros) to claim the throne in Richard's stead and have himself proclaimed King Henry IV. In June, Ros was present at Berkeley Castle

Berkeley Castle ( ; historically sometimes spelled as ''Berkley Castle'' or ''Barkley Castle'') is a castle in the town of Berkeley, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom. The castle's origins date back to the 11th century, and it has been desi ...

when Henry and Richard met for the first time since Henry was exiled; de Ros witnessed their final meeting on 6 September at the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, when Richard resigned the throne. Bolingbroke's accession as Henry IV saw an uplift in Ros's fortunes and those of the Fitzalans. Ros now had strong connections with important figures at court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance ...

and a relatively close friendship with the new king. In contrast to his treatment by Richard, Ros's previous loyal service to Henry—and the king's father—earned him significant royal patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

. In the first parliament of the new reign—held at Westminster in October 1399—he was appointed a Trier of Petitions, and was one of the lords who voted to imprison Richard (who later died in Pontefract Castle

Pontefract (or Pomfret) Castle is a castle ruin in the town of Pontefract, in West Yorkshire, England. King Richard II is thought to have died there. It was the site of a series of famous sieges during the 17th-century English Civil War. ...

of unknown causes). Ros's new position at the centre of government was highlighted in December 1399, when he was appointed to Henry's first royal council.

Ros's motives for joining Bolingbroke's invasion so swiftly are unknown but, says Given-Wilson, this should be no surprise; for most of Henry's new-found allies, "it is only possible to speculate as to their political allegiance". Ros may have felt generally aggrieved by Richard's poor treatment of Gaunt and Bolingbroke, and his own lack of promotion under Richard was doubtless influential. Whatever his reasons were for rebelling in 1399, Ros and his father had been Lancastrian (rather than Ricardian) in their loyalties. His father had been one of John of Gaunt's earliest retainers when the young Gaunt was Earl of Richmond

The now-extinct title of Earl of Richmond was created many times in the Peerage of England. The earldom of Richmond was initially held by various Breton nobles; sometimes the holder was the Breton duke himself, including one member of the cad ...

, and Ros had also been retained by Gaunt in the late fourteenth century. Service to the duke had involved Ros accompanying the duke abroad and travelling on his business on at least five occasions in the last years of Gaunt's life. For his services Ros received annuities of £40 to £50, and was one of only two knights banneret

A knight banneret, sometimes known simply as banneret, was a medieval knight ("a commoner of rank") who led a company of troops during time of war under his own banner (which was square-shaped, in contrast to the tapering standard or the penn ...

whom Gaunt retained.

Local administration and political crisis

Ros was an active royal official in the local administration and became a leading member of political society in the northMidlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

and Yorkshire, where he regularly headed royal commissions. He was frequently appointed a justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

, particularly in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

. Ros's service to the crown was not confined to the regions; in 1401, he directed the king's attempts to increase the royal income. He was appointed Henry's negotiator with the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, to persuade the Commons to agree to a subsidy for the king's intended invasion of Scotland later that summer. Ros and the Commons representatives met in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

's refectory. Emphasising "favourable consideration" the Commons would receive from the king, he played heavily on the king's expenses in defending the Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

and Scottish Marches

Scottish Marches was the term used for the Anglo-Scottish border during the late medieval and early modern eras, characterised by violence and cross-border raids. The Scottish Marches era came to an end during the first decade of the 17th century ...

. Each party was wary of the other; the king did not wish to set a precedent, and the Commons were traditionally wary of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

. Six years later, Ros played much the same role—with the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was Du ...

and the Archbishop of Canterbury, on a committee hearing the Commons' complaints. The result of these discussions was an altercation in which the Commons, reports the parliament roll, were "hugely disturbed". This disturbance, according to J. H. Wylie, was probably the result of something Ros said and would account for the Commons' reluctance to meet him or his committee. Ros's remit was to persuade the Commons to grant as substantial a tax—in exchange for as few liberties granted—as possible. An experienced parliamentarian, he attended most parliaments from 1394 to 1413.

Almost from the beginning of his reign, Henry faced problems. Most stemmed from financial insecurity since by 1402 his treasury was empty. Around this time, Ros was appointed Lord Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in ...

. Charles Ross suggests that this demonstrated the king's increased confidence in Ros, who occupied the post for the next four years. He was unable to substantially improve Henry's financial situation, and relations with the Commons worsened. During the 1404 parliament, speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** In ...

Arnold Savage

Sir Arnold Savage of Bobbing, Kent (8 September 13581410) was the English Speaker of the House of Commons from 1400 to 1402 and then again from 1403 to 1404 and a Knight of the Shire of Kent who was referred to as "the great comprehensive sym ...

confronted the king over his lack of money (and repeated demands for taxation), which Savage said could be ameliorated by reducing the number of annuities paid by the crown. Savage also condemned an unnamed crown minister for owing royal creditors over £6,000. The House of Commons' dissatisfaction was obvious to the king, who responded within the week. He despatched Ros, accompanied by Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Henry Beaufort

Cardinal Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 – 11 April 1447), Bishop of Winchester, was an English prelate and statesman who held the offices of Bishop of Lincoln (1398) then Bishop of Winchester (1404) and was from 1426 a Cardinal of the Church of Ro ...

, to the Commons with a comprehensive breakdown of the king's financial requirements. According to Ian Mortimer, "Savage, having attacked royal policy in the King's presence, had no compunction about speaking his mind to the chancellor and treasurer". Henry's government continued to subsist on poor revenues. As Given-Wilson put it, the treasury became "largely reliant on a diminishing circle of the faithful" (which included Ros). He made numerous loans to the king, and temporarily surrendered his councillor's salary for the sake of the royal finances.

Ros also performed extensive military service. In 1400, he contracted with the king to bring a fully crewed ship of twenty men at arms

A man-at-arms was a soldier of the High Medieval to Renaissance periods who was typically well-versed in the use of arms and served as a fully-armoured heavy cavalryman. A man-at-arms could be a knight, or other nobleman, a member of a knig ...

and forty archers to Henry's Scottish invasion. Although the campaign fizzled out, Ros played a part in it. Returning to Westminster, he resumed his office of councillor and participated in Henry's Great Council the following year. In 1402 Owain Glyndŵr

Owain ap Gruffydd (), commonly known as Owain Glyndŵr or Glyn Dŵr (, anglicised as Owen Glendower), was a Welsh leader, soldier and military commander who led a 15 year long Welsh War of Independence with the aim of ending English rule in Wa ...

rebelled

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

, which impacted Ros personally. His brother-in-law, Reginald, Lord Grey of Ruthin—who had married Ros's youngest sister, Margaret—was captured and imprisoned by Glyndŵr; personal animosity between Grey and Glyndŵr may have been to blame for the outbreak of the rebellion. The Welsh demanded a 10,000-mark ransom from the king, who agreed to pay. Ros, because of his relationship to Grey, also agreed to contribute and led the commission which negotiated with Glyndŵr over its payment and his brother-in-law's release. A friend of Ros, fellow Midlands baron Robert, Lord Willoughby, accompanied him in the negotiations.

Ros was also elected to the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George C ...

in 1402, and was granted an annuity of 100 marks a year as the king's retainer

Retainer may refer to:

* Retainer (orthodontics), devices for teeth

* RFA ''Retainer'' (A329), a ship

* Retainers in early China, a social group in early China

Employment

* Retainer agreement, a contract in which an employer pays in advance for ...

two years later. In May of that year another rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

broke out in the north, led by Richard Scrope, Archbishop of York and the disaffected Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland. One of their first acts was to kidnap the king's envoy. Ros was part of an extensive network of north Lancastrian loyalists who gathered around the king's cousin Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland to suppress the rebellion. Henry entrusted Ros to meet with Westmorland, commander of the king's armies in the north. Ros was probably chosen because of the king's intimate advisors, his local knowledge would have been the most valuable. The mission was a success; Ros witnessed the Earl of Northumberland surrendering Berwick Castle

Berwick Castle is a ruined castle in Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, England.

History

The castle was commissioned by the Scottish David I of Scotland, King David I in the 1120s. It was taken by the English forces under the terms of the Tr ...

to the king, and sat on the commission which condemned Scrope to death without trial in early June 1405. When the king arrived in York to oversee the execution of the rebels, Ros brought Percy's bonds to him.

Since Ros had been instructed only to engage the rebels on the king's express instruction, it is difficult to ascertain the role that he and Gascoigne played in the rebellion's suppression. Unlike the Earl of Westmorland, "no more is heard of their activities" in the north until after the confrontation at Shipton Moor. Ros's role may have been to oversee the later judicial commissions over the rebels, and he was authorised to pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

those who rejected rebellion and wished to return to the king's grace. The fact that so little of their work remains visible to historians may suggest surreptitiousness; possibly, says Given-Wilson, they were little more than spies tailing their prey until the king's main army caught up.

The following year, the king's health (which had not been strong for some time) broke down for good. At the parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

of 1406, Henry IV agreed that since it was clear that poor health prevented him from ruling, a Grand Council should be established to assist him in governing. Although Ros was on the original list presented to parliament of those to be appointed to the council, how long he served is subject to conjecture. He was attending its meetings in late 1406 (since he was an unofficial "chaperone" for his successor as Lord Treasurer, Lord Furnivall), and may have still been on the council the following June. Ros regularly witnessed royal charters, and continued his role as the king's spokesman to the Commons. He probably assisted the Lord Chancellor through an increasingly difficult and uncertain period (due to the King's ill health), but it is uncertain whether he chose—or was instructed—to do so.

Royal favour

For the duration of Henry's reign, Ros was "high in the King's confidence and enjoyed especially trusted positions". The historian Mark Arvanigian summarises Ros's position as "clearly a reliable and trusted servant, as well as being a reasonably talented administrator and royal councillor". Henry continued relying on loans to carry out policy, and Ros's loan funded the Calais garrison. Unlike many—and indicating the favour with which the King held him in—Ros was promised repayment, manifested in the royal patronage he continued to receive. By 1409, for example, he had been appointed to the lucrative positions of master forester and constable of

For the duration of Henry's reign, Ros was "high in the King's confidence and enjoyed especially trusted positions". The historian Mark Arvanigian summarises Ros's position as "clearly a reliable and trusted servant, as well as being a reasonably talented administrator and royal councillor". Henry continued relying on loans to carry out policy, and Ros's loan funded the Calais garrison. Unlike many—and indicating the favour with which the King held him in—Ros was promised repayment, manifested in the royal patronage he continued to receive. By 1409, for example, he had been appointed to the lucrative positions of master forester and constable of Pickering Castle

Pickering Castle is a motte-and-bailey fortification in Pickering, North Yorkshire, England.

Design

Pickering Castle was originally a timber and earth motte and bailey castle. It was developed into a stone motte and bailey castle which had ...

. These offices strengthened his influence in the region, allowed him to appoint deputies, and gave him another patronage of his own to dispense. In October of that year, Ros paid £80 for the custody of Giffard family lands in the South Midlands

The South Midlands is an area of England which includes Northamptonshire, the northern parts of Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire and the western part of Bedfordshire. Unlike the East Midlands or West Midlands (region), West Midlands, the South M ...

. John Tuchet, Lord Audley died in December, and Ros was granted Audley's lands while the Audley heir was a minor

Minor may refer to:

* Minor (law), a person under the age of certain legal activities.

** A person who has not reached the age of majority

* Academic minor, a secondary field of study in undergraduate education

Music theory

*Minor chord

** Barb ...

. Ros also paid £2,000 for the right to arrange the heir's marriage. The Audley estates from which Ros intended to get his money back were greatly overvalued, and he was charged only half the original amount. These grants were in addition to his annual conciliar salary of £100, and he held the manor of Chingford

Chingford is a town in east London, England, within the London Borough of Waltham Forest. The town is approximately north-east of Charing Cross, with Waltham Abbey to the north, Woodford Green and Buckhurst Hill to the east, Walthamstow to the ...

to quarter A quarter is one-fourth, , 25% or 0.25.

Quarter or quarters may refer to:

Places

* Quarter (urban subdivision), a section or area, usually of a town

Placenames

* Quarter, South Lanarkshire, a settlement in Scotland

* Le Quartier, a settlement ...

himself and his men when he was regularly in the south on royal business. Ros remained an active councillor and undertook significant military and diplomatic roles. He was one of Henry's few advisors who, even when the king's council was not sitting, remained a close counsellor.

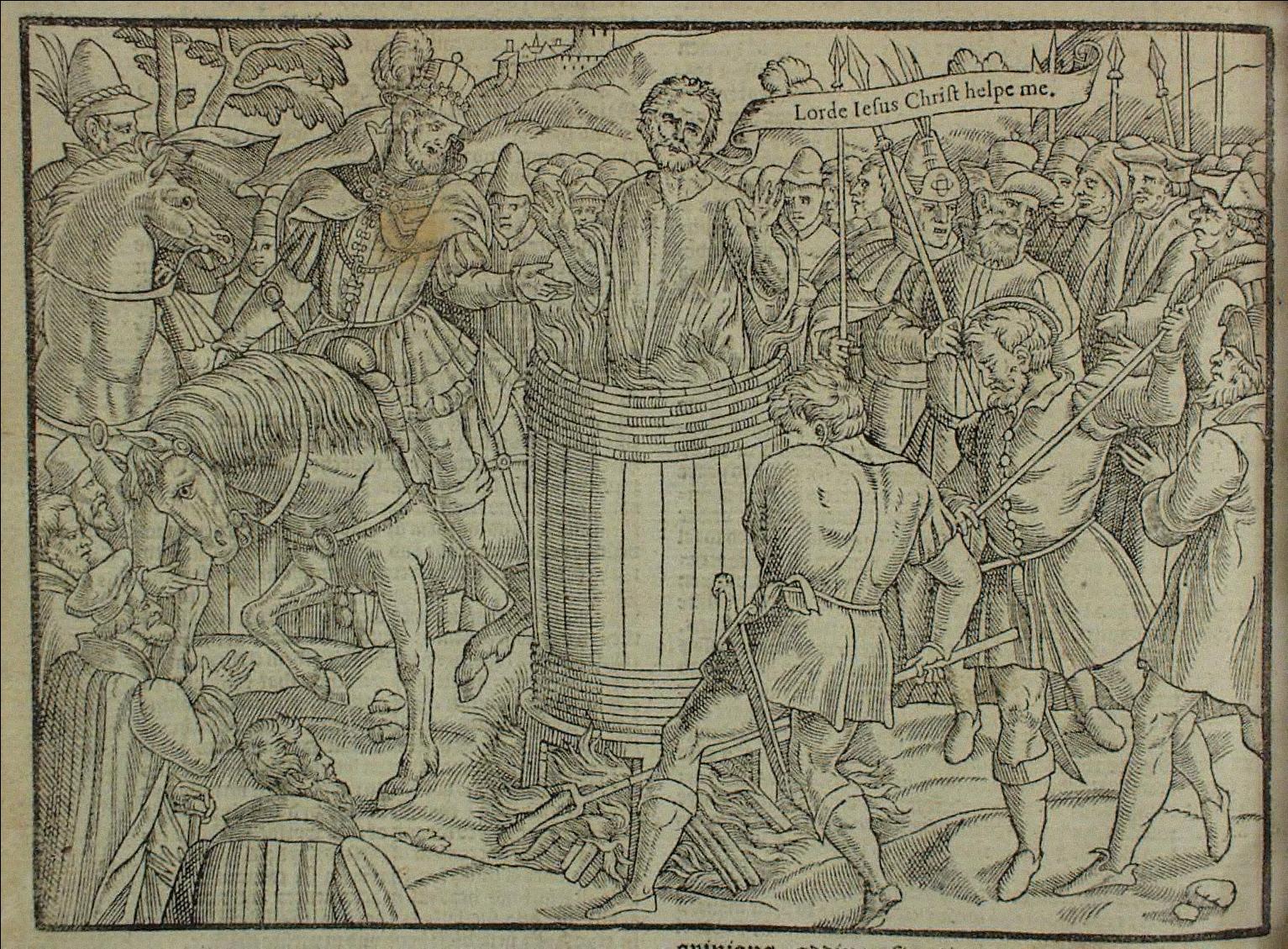

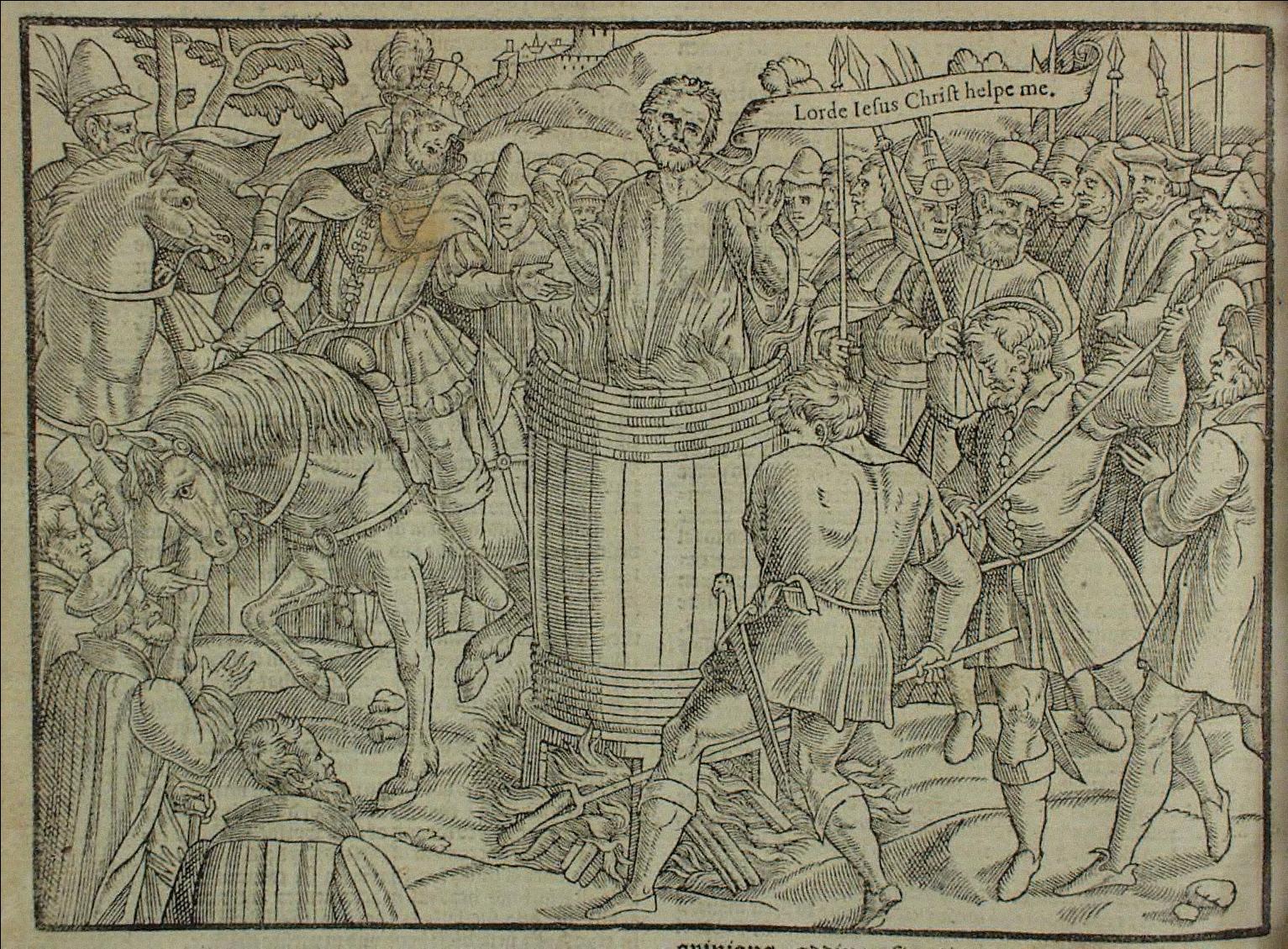

Ros remained in the King's favour through the final years of Henry's reign. As a trusted counsellor, in 1410 he participated in what has been described as "a show trial of national importance". The previous year, an ecclesiastical court

An ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain courts having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the Middle Ages, these courts had much wider powers in many areas of Europe than be ...

had found John Badby

John Badby (1380–1410), one of the early Lollard martyrs, was a tailor (or perhaps a blacksmith) in the west Midlands, and was condemned by the Worcester diocesan court for his denial of transubstantiation.

Badby bluntly maintained that when C ...

of Evesham

Evesham () is a market town and parish in the Wychavon district of Worcestershire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is located roughly equidistant between Worcester, Cheltenham and Stratford-upon-Avon. It lies within the Vale of Evesha ...

guilty of Lollardy

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

. According to church custom, Badby had been given a year's grace to recant. He refused; if anything, his opinions were more entrenched than before. On 1 March 1410, Badby was brought before a convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a speci ...

at the Friars-Preachers

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of Cal ...

House. Ros and his fellow barons found Badby guilty and passed secular judgement. He was burnt to death

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an list of execution methods, execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have em ...

(possibly, according to sixteenth-century martyrologist

A martyrology is a catalogue or list of martyrs and other saints and beati arranged in the calendar order of their anniversaries or feasts. Local martyrologies record exclusively the custom of a particular Church. Local lists were enriched by na ...

John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the su ...

, in a barrel

A barrel or cask is a hollow cylindrical container with a bulging center, longer than it is wide. They are traditionally made of wooden staves and bound by wooden or metal hoops. The word vat is often used for large containers for liquids, ...

) in Smithfield.

Regional disorder

After the death of theEarl of Stafford

Baron Stafford, referring to the town of Stafford, is a title that has been created several times in the Peerage of England. In the 14th century, the barons of the first creation were made earls. Those of the fifth creation, in the 17th century ...

in 1403 (whose infant heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officiall ...

had a twenty-year minority), Ros was the leading baron in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

. He was responsible for upholding the king's peace during a period that has been a by-word for the kind of pervasive lawlessness that Ros, like all regional magnates, was expected to suppress. Particularly well-known is the frequency with which the baronage and gentry indulged in internecine fighting. In 1411, his intervention averted a tense situation which was likely to erupt into armed conflict between local gentry Alexander Mering and John Tuxford. This was only a temporary ceasefire, however; the following year, Ros sponsored a second arbitration between the parties with which they promised to abide on pain of a 500-mark fine. In early 1411 Sir Walter Tailboys caused a riot in Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

, attacked the sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

s, killed two men, and lay in wait outside the city in ambush (preventing its residents from leaving). Lincoln's citizens petitioned the king for justice and explicitly requested that Ros and his kinsman, Lord Beaumont, be appointed to investigate. They found in favour of the Lincoln citizenry and, reflecting the severity of Tailboy's offence, he was bound over

In the law of England and Wales and some other common law jurisdictions, binding over is an exercise of certain powers by the criminal courts used to deal with low-level public order issues. Both magistrates' courts and the Crown Court may issue b ...

to keep the peace for £3,000. Due to such efforts, Simon Payling

Simon may refer to:

People

* Simon (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name Simon

* Simon (surname), including a list of people with the surname Simon

* Eugène Simon, French naturalist and the genus ...

has suggested that Ros's "reputation for fair-mindedness" made him a popular figure for settling gentry disputes.

Despite his aptitude for dispute resolution, Ros was not exempt from local conflict. He became involved in a dispute with his Lincolnshire neighbour, Sir Robert Tirwhit, in 1411. Tirwhit was a newly appointed royal justice and a well-known figure in the county. He and Ros fell out over conflicting claims to common grazing and associated hay-mowing and turf-digging rights in

Despite his aptitude for dispute resolution, Ros was not exempt from local conflict. He became involved in a dispute with his Lincolnshire neighbour, Sir Robert Tirwhit, in 1411. Tirwhit was a newly appointed royal justice and a well-known figure in the county. He and Ros fell out over conflicting claims to common grazing and associated hay-mowing and turf-digging rights in Wrawby

Wrawby is a village in North Lincolnshire, England. It lies east of Brigg and close to Humberside Airport, on the A18. The 2001 Census recorded a village population of 1,293, in around 600 homes, which increased to 1,469 at the 2011 census. W ...

. An arbitration

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or 'arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ' ...

took place before Justice William Gascoigne

Sir William Gascoigne (c. 135017 December 1419) was Chief Justice of England during the reign of King Henry IV.

Life and work

Gascoigne (alternatively spelled Gascoyne) was a descendant of an ancient Yorkshire family. He was born in Gawthor ...

, who ordered a Loveday arranged. The Loveday was intended to offer both parties the opportunity to demonstrate their support for the arbitration process; the two men were expected to attend with companions (or followers), keeping their numbers to a minimum. Tirwhit, however, brought a small army of about 500 men. Later justifying the size, he claimed not to have agreed to the Loveday in the first place. Ros kept to the arrangement ''vis á vis'' his retinue, bringing with him only Lords Beaumont and de la Warre (the latter, like Beaumont, a relative).

He and his companions escaped Tirwhit's ambush unharmed. Given-Wilson has argued that, although the case was not uncommon in its basic facts, "the personal involvement of a royal justice in such a calculated act of violence, and the status of the protagonists, clearly gave it an interest above the usual". On 4 November 1411, Ros petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to some offici ...

ed parliament—at which he was appointed a Trier of Petitions—for satisfaction. The case was heard before the Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Sovereign of the United Kingdom while also acting as the main cha ...

and the Archbishop of Canterbury, and took over three weeks to determine. The Chamberlain and Archbishop requested the attendance of Ros and all the "knyghtes and Esquiers and Yomen that had ledynge of men" for him. After deliberating, they found firmly in Ros's favour. Tirwhit was bound to give Ros a quantity of Gascon wine

Gascon may refer to:

* Gascony, an area of southwest France

* Gascon language

* Gascon cattle

* Gascon pig

* Gascon (grape), another name for the French wine grape Mondeuse noire

People

*Elvira Gascón (1911–2000), Spanish painter and engraver

...

and provide the food and drink for the next Loveday, where he would publicly apologise to Ros. In his apology, Tirwhit acknowledged that a nobleman of Ros's position could also have brought an army and he had shown forbearance in not doing so. The only responsibility Ros was given as part of the arbitration award was that at the second Loveday, he would provide the entertainment.

Later years and death

Although the King's health continued to decline, he improved sufficiently in 1411 to direct the formation of a new council of his loyal councillors; this intentionally excluded his son, Prince Henry and the prince's associates, Henry and Thomas Beaufort, from power. Ros—the "reliable royalist"—sat on the council for the next fifteen months with other "unswervingly loyal" officials, such as the Bishops ofDurham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

*Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in No ...

and Bath and Wells

The Diocese of Bath and Wells is a diocese in the Church of England Province of Canterbury in England.

The diocese covers the county of Somerset and a small area of Dorset. The Episcopal seat of the Bishop of Bath and Wells is located in the C ...

and the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

. Ros and the others now signed administrative documents which had required the king's signet seal. A. L. Brown and Henry Summerson

Henry Summerson is an English historian. He is the author of a number of books.

Summerson worked for the Carlisle Archaeological Unit and wrote a history of medieval Carlisle (1993). He was then employed by English Heritage writing a number of g ...

, two of the king's recent biographers, note that "at the end of his reign, as at its beginning, Henry placed his trust principally in his Lancastrian retainers".

Henry IV died on 20 March 1413. William Ros played no significant role in government from then on, after probably attending his last council meeting in 1412. Charles Ross posits that he was "no particular favourite" of the new king, Henry V, which Ross attributed to Henry V's distrust of his father's loyalists (who, in his eyes, kept him from what he felt was his rightful position at the head of government during his father's illness). Whether or not Henry excluded him from the government, Ros lived only eighteen months into the new reign. His mother had drawn up her will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

in January 1414, of which Ros was an executor

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty. The feminine form, executrix, may sometimes be used.

Overview

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker of a ...

. Early that year, Ros sat on a final anti-Lollard

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

commission and was tasked with investigating the murder of an MP in the Midlands.

Ros died in Belvoir Castle

Belvoir Castle ( ) is a faux historic castle and stately home in Leicestershire, England, situated west of the town of Grantham and northeast of Melton Mowbray. The Castle was first built immediately after the Norman Conquest of 1066 an ...

on 1 November 1414. He had drawn up his will two years earlier, and added a codicil

Codicil may refer to:

* Codicil (will), subsequent change or modification of terms made and appended to an existing trust or will and testament

* A modification of terms made and appended to an existing constitution, treaty, or standard form c ...

in February 1414. He died a wealthy man, with one of Yorkshire's highest disposable income

Disposable income is total personal income minus current income taxes. In national accounts definitions, personal income minus personal current taxes equals disposable personal income. Subtracting personal outlays (which includes the major c ...

s.

Three of William Ros's children fought in the last period of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

. John, his heir, was born in 1397 and was legally a minor when Ros died. The Earl of Dorset

Earl of Dorset is a title that has been created at least four times in the Peerage of England. Some of its holders have at various times also held the rank of marquess and, from 1720, duke.

A possible first creation is not well documented. About ...

, the king's cousin, received custody of the Ros estates. Before he inherited, John travelled to France with the new king in 1415 and fought at the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; french: Azincourt ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected English victory against the numerica ...

at the age of seventeen or eighteen. He died in 1421 at the Battle of Baugé

The Battle of Baugé, fought between the English and a Franco- Scots army on 22 March 1421 at Baugé, France, east of Angers, was a major defeat for the English in the Hundred Years' War. The English army was led by the king's brother Thomas, ...

with the king's brother, Thomas, Duke of Clarence and Sir Gilbert V de Umfraville

Gilbert V de Umfraville (July 1390 – 22 March 1421), popularly styled the "Earl of Kyme", was an English noble who took part in the Hundred Years War. He was killed during the Battle of Baugé in 1421 fighting a Franco-Scots army.

Life

Gilber ...

. William Ros's second son Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

was only fourteen at John's death, and fought with Thomas, Earl of Salisbury, at the siege of Orléans

The siege of Orléans (12 October 1428 – 8 May 1429) was the watershed of the Hundred Years' War between France and England. The siege took place at the pinnacle of English power during the later stages of the war. The city held strategic and ...

in 1428; he died after a skirmish outside Paris two years later. Thomas' heir (also named Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

) inherited the lordship as 9th baron and played an important role in the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

fighting for the Lancastrian king, Henry VI; he was beheaded

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

after his defeat by the Yorkists

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, t ...

at the Battle of Hedgeley Moor

The Battle of Hedgeley Moor, 25 April 1464, was a battle of the Wars of the Roses. It was fought at Hedgeley Moor, north of the villages of Glanton and Powburn in Northumberland, between a Yorkist army led by John Neville, Lord Montagu and a ...

in 1464. Ros's wife, Margaret Fitzalan, lived until 1438. She had received her dower by February 1415 and, at the marriage of Henry V to Catherine of Valois

Catherine of Valois or Catherine of France (27 October 1401 – 3 January 1437) was Queen of England from 1420 until 1422. A daughter of Charles VI of France, she was married to Henry V of England and gave birth to his heir Henry VI of Englan ...

in 1420, entered the new queen's service as a lady-in-waiting

A lady-in-waiting or court lady is a female personal assistant at a court, attending on a royal woman or a high-ranking noblewoman. Historically, in Europe, a lady-in-waiting was often a noblewoman but of lower rank than the woman to whom sh ...

. Margaret attended Katherine's coronation and travelled with her to see Henry in France two years later.

Family and bequests

With his wife, Margaret Fitzalan, William Ros had four sons:John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

, Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

and Richard. They also had four daughters: Beatrice, Alice, Margaret and Elizabeth. Ros also had an illegitimate son, John, by a now-unknown woman. Charles Ross suggests that he "provides full confirmation of what the scanty evidence as to the character of his earlier career suggests, that Ros was a man of just and equitable temperament" by the nature and extent of his bequests. His heir, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, inherited his father's lordship and patrimony and his armour and a gold sword. His third son, Robert—whom Ross describes as "evidently his favourite"—also inherited a quantity of land. Ros made this provision for Robert from John's patrimony, a decision described by G. L. Harriss as "overrid ngboth family duty and convention". His younger three sons (Thomas, Robert, and Richard) received a third of Ros's goods among them; Thomas, traditional for a younger son, was intended for an ecclesiastical career. Ros's wife, Margaret, received another third of his goods. His illegitimate son, John, received £40 towards his upkeep. Loyal retainers received benefices, and Ros's "humbler dependents"—for instance, the poor on his Lincolnshire estates—received often-massive sums among them. His executors—one of whom was his heir, John—received £20 each for their services. Ros was buried in Belvoir Priory

Belvoir Priory (pronounced ''Beaver'') was a Benedictine priory near to Belvoir Castle. Although once described as within Lincolnshire, it is currently located in Leicestershire, near the present Belvoir Lodge.

History

The priory was establ ...

, and an alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral or rock that is soft, often used for carving, and is processed for plaster powder. Archaeologists and the stone processing industry use the word differently from geologists. The former use it in a wider sense that includes ...

effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

was erected in St Mary the Virgin's Church, Bottesford, on the right side of the altar. Seven years later, after his death at Baugé, an effigy of his son John was placed on the left. William Ros left £400 to pay ten chaplains for eight years to educate his sons.

In Shakespeare

William Ros appears inWilliam Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father died ...

'' as Lord Ross. His character performs a double act

A double act (also known as a comedy duo) is a form of comedy originating in the British music hall tradition, and American vaudeville, in which two comedians perform together as a single act. Pairings are typically long-term, in some cases f ...

of sorts with Lord Willoughby in their (ultimately successful) attempts to persuade the Earl of Northumberland to revolt against Richard, although as one reviewer has noted, indicating "little sense of rebels carefully testing the political water" before doing so. Together, the three of them are the core of the conspiracy to overthrow Richard. In their colloquies—for which R. F. Hill has compared them to a Senecan Chorus

Chorus may refer to:

Music

* Chorus (song) or refrain, line or lines that are repeated in music or in verse

* Chorus effect, the perception of similar sounds from multiple sources as a single, richer sound

* Chorus form, song in which all verse ...

— they provide the audience with a catalogue of Richard's misdeeds by re-telling his history of poor governance. Ross, says Hill, is "lured" by the earl into conversation, which results in their plotting. Ross tells Northumberland, "The commons hath ing Richardpill'd with grievous taxes / And quite lost their hearts: the nobles hath he fined / For ancient quarrels, and quite lost their hearts" and is portrayed as an overt follower of Henry Bolingbroke from the beginning. Shakespeare has this discussion take place in the north; in this way, says Hill, their separation from the King emphasises their geographical closeness to Bolingbroke.

The speed with which Ross deserts Richard and joins Henry is in stark contrast to the themes of loyalty and honour that the play deals with, suggests Margaret Shewring. Described by Shakespeare (based on Raphael Holinshed

Raphael Holinshed ( – before 24 April 1582) was an English chronicler, who was most famous for his work on ''The Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande'', commonly known as ''Holinshed's Chronicles''. It was the "first complete printe ...

's chronicle) as "fiery-red with haste", Ross joins Bolingbroke at Berkeley, Gloucestershire

Berkeley ( ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, parish in the Stroud (district), Stroud District in Gloucestershire, England. It lies in the Vale of Berkeley between the east bank of the River Severn and the M5 motorway. The town is ...

. In 1738—when the public image of the King, George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria ( fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

, was poor—the play was put on by John Rich

John Rich (born January 7, 1974) is an American country music singer-songwriter. From 1992 to 1998, he was a member of the country music band Lonestar, in which he played bass guitar and alternated with Richie McDonald as lead vocalist. After d ...

, in the knowledge that it was "dangerously topical in terms of contemporary politics". The discussion between Ross, Willoughby and Northumberland on the faults of the King—"basely led/by flatterers"—has been argued to have reflected contemporary disfavour with George, who was widely believed to be under the influence of his chief minister, Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole (), 4th Earl of Orford (24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English writer, art historian, man of letters, antiquarian, and Whigs (British political party), Whig politician.

He had Strawb ...

. A contemporary, Thomas Davies, watched the performance and later wrote how "almost every line that was spoken to the occurrences of the time, and to the measures and character of the ministry".

The text of ''Richard II'' is often cut by directors, either to tighten the plot or to avoid problems with weak casting, and the role of Lord Ross is occasionally omitted. For example, in the 1981 Bard Productions film, Ross' part was given to the Exton character, and in the Erickson-Farrell 2001 film, Ross was one of seven characters dropped, his part again given to Exton. He has still been played by several actors in post-war performances. At the 1947 Avignon Festival

The ''Festival d'Avignon'', or Avignon Festival, is an annual arts festival held in the French city of Avignon every summer in July in the courtyard of the Palais des Papes as well as in other locations of the city. Founded in 1947 by Jean Vila ...

, Pierre Lautrec played to Jean Vilar

Jean Vilar (25 March 1912– 28 May 1971) was a French actor and theatre director.

Vilar trained under actor and theatre director Charles Dullin, then toured with an acting company throughout France. His directorial career began in 1943 in a sma ...

's Richard; Vilar also directed the play. The same year, Walter Hudd

Walter Hudd (20 February 1897 – 20 January 1963) was a British actor and director.

Stage career

Hudd made his stage debut in ''The Manxman'' in 1919, and later toured as part of the Fred Terry Company; first attracting serious attention play ...

directed it with the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre