William Of Ireland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England.

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England.

Eleanor of Castile died on 28 November 1290 at

Eleanor of Castile died on 28 November 1290 at

The twelve crosses were erected to mark the places where Eleanor's funeral procession had stopped overnight. Their construction is documented in the executors' account rolls, which survive from 1291 to March 1294, but not thereafter. By the end of that period, the crosses at Lincoln, Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans and Waltham were complete or nearly so, and those at Cheapside and Charing in progress; but those at Grantham, Stamford and Geddington apparently not yet begun. It is assumed that these last three were erected in 1294 or 1295, and that they were certainly finished before the financial crisis of 1297 which brought a halt to royal building works.Colvin 1963, pp. 483–4. A number of artists worked on the crosses, as the account rolls show, with a distinction generally drawn between the main structures, made locally under the direction of master masons appointed by the King, and the statues of Eleanor, made of Caen stone, and other sculptural details, brought from London. Master masons included Richard of Crundale, Roger of Crundale (probably Richard's brother), Michael of Canterbury, Richard of Stow, John of Battle and Nicholas Dymenge. Sculptors included Alexander of Abingdon and William of Ireland, both of whom had worked at Westminster Abbey, who were paid £3 6s. 8d. apiece for the statues; and Ralph of Chichester.

The twelve crosses were erected to mark the places where Eleanor's funeral procession had stopped overnight. Their construction is documented in the executors' account rolls, which survive from 1291 to March 1294, but not thereafter. By the end of that period, the crosses at Lincoln, Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans and Waltham were complete or nearly so, and those at Cheapside and Charing in progress; but those at Grantham, Stamford and Geddington apparently not yet begun. It is assumed that these last three were erected in 1294 or 1295, and that they were certainly finished before the financial crisis of 1297 which brought a halt to royal building works.Colvin 1963, pp. 483–4. A number of artists worked on the crosses, as the account rolls show, with a distinction generally drawn between the main structures, made locally under the direction of master masons appointed by the King, and the statues of Eleanor, made of Caen stone, and other sculptural details, brought from London. Master masons included Richard of Crundale, Roger of Crundale (probably Richard's brother), Michael of Canterbury, Richard of Stow, John of Battle and Nicholas Dymenge. Sculptors included Alexander of Abingdon and William of Ireland, both of whom had worked at Westminster Abbey, who were paid £3 6s. 8d. apiece for the statues; and Ralph of Chichester.

()

()

Eleanor rested on the first night of the journey at The Priory of Saint Katherine without Lincoln and her viscera were buried in

()

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 4 December 1290 in

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 5 December 1290, and possibly also that of 6 December, in

()

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of either 6 or 7 December 1290, or possibly both, in Geddington,

()

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 8 December 1290, and perhaps also that of 7 December, at

(plaque at )

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 9 December 1290 at

(plaque at )

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 9 December 1290 at

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 12 December 1290 at

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 12 December 1290 at

()

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 13 December 1290 in the parish of

()

Eleanor's bier reached the

()

Eleanor's bier reached the

()

Eleanor's bier spent the final night of its journey, 16 December 1290, in the

()

Eleanor's bier spent the final night of its journey, 16 December 1290, in the

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England.

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England. King Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

had them built between 1291 and about 1295 in memory of his beloved wife Eleanor of Castile

Eleanor of Castile (1241 – 28 November 1290) was Queen of England as the first wife of Edward I, whom she married as part of a political deal to affirm English sovereignty over Gascony.

The marriage was known to be particularly close, and ...

. The King and Queen had been married for 36 years and she stayed by the King’s side through his many travels. While on a royal progress, she died in the East Midlands

The East Midlands is one of nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. It comprises the eastern half of the area traditionally known as the Midlands. It consists of Leicestershire, Derbyshire, L ...

in November 1290. The crosses, erected in her memory, marked the nightly resting-places along the route taken when her body was transported to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

near London.

The crosses stood at Lincoln, Grantham

Grantham () is a market and industrial town in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, situated on the banks of the River Witham and bounded to the west by the A1 road. It lies some 23 miles (37 km) south of the Lincoln a ...

and Stamford, all in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-we ...

; Geddington and Hardingstone

Hardingstone is a village in Northamptonshire, England. It is on the southern edge of Northampton, and now forms a suburb of the town. It is about from the town centre. The Newport Pagnell road (the B526, formerly part of the A50) separates ...

in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It ...

; Stony Stratford

Stony Stratford is a constituent town of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. Historically it was a market town on the important route from London to Chester ( Watling Street, now the A5). It is also the name of a civil parish with a town ...

in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-e ...

; Woburn and Dunstable

Dunstable ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Bedfordshire, England, east of the Chiltern Hills, north of London. There are several steep chalk escarpments, most noticeable when approaching Dunstable from the north. Dunstable is t ...

in Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

; St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major town on the old Roman ...

and Waltham (now Waltham Cross

Waltham Cross is a town in the Borough of Broxbourne, Hertfordshire, England, located north of central London. In the south-eastern corner of Hertfordshire, it borders Cheshunt to the north, Waltham Abbey to the east, and Enfield to the sou ...

) in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

; Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, whe ...

in London; and Charing (now Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City ...

) in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

.

Three of the medieval monuments – those at Geddington, Hardingstone and Waltham Cross – survive more or less intact; but the other nine, other than a few fragments, are lost. The largest and most ornate of the twelve was the Charing Cross. Several memorials and elaborated reproductions of the crosses have been erected including, the Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross at Charing Cross Station (built 1865).

Background

Procession and burials

Eleanor of Castile died on 28 November 1290 at

Eleanor of Castile died on 28 November 1290 at Harby, Nottinghamshire

Harby is the easternmost village in the English county of Nottinghamshire. The nearest city is Lincoln, over the border in Lincolnshire. According to the 2011 census, it had a population of 336, up from 289 at the 2001 census.

Heritage Eleanor ...

. Edward and Eleanor loved each other and much like his father, Edward was very devoted to his wife and remained faithful to her throughout their married lives. He was deeply affected by her death and displayed his grief by erecting twelve so-called Eleanor crosses, one at each place where her funeral cortège stopped for the night.

Following her death the body of Queen Eleanor was carried to Lincoln, about away, where she was embalmed – probably either at the Gilbertine

The Gilbertine Order of Canons Regular was founded around 1130 by Saint Gilbert in Sempringham, Lincolnshire, where Gilbert was the parish priest. It was the only completely English religious order and came to an end in the 16th century at t ...

priory of St Catherine in the south of the city, or at the priory of the Dominicans. Her viscera

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a f ...

, less her heart, were buried in the Angel Choir of Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln Minster, or the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln and sometimes St Mary's Cathedral, in Lincoln, England, is a Grade I listed cathedral and is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Lincoln. Construc ...

on 3 December. Eleanor's other remains were carried to London, a journey of about , that lasted 12 days. Her body was buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, at the feet of her father-in-law King Henry III on 17 December; while her heart was buried in the church of the London Dominicans' priory at Blackfriars (a house that she and Edward had heavily patronised) on 19 December, along with those of her young son Alphonso, Earl of Chester

Alphonso or Alfonso (24 November 1273 – 19 August 1284), also called Alphonsus and Alphonse and styled Earl of Chester, was an heir apparent to the English throne who never became king.

Alphonso was the ninth child of King Edward I of Engla ...

, who had died in 1284, and of John de Vesci, who had died in 1289.Cockerill 2014, p. 344.

Commemoration

Tomb monuments

Both the burial of Eleanor's body at Westminster and her visceral burial at Lincoln were subsequently marked by ornate effigial monuments, both with similar life-sized gilt bronze effigies cast by the goldsmith William Torell. Her heart burial at the Blackfriars was marked by another elaborate monument, but probably not with a life-sized effigy.Colvin 1963, pp. 482–83.Galloway 1914, pp. 79–80. The Blackfriars monument was lost following the priory's dissolution in 1538. The Lincoln monument was destroyed in the 17th century, but was replaced in 1891 with a reconstruction, not on the site of the original. The Westminster Abbey monument survives.Crosses

The twelve crosses were erected to mark the places where Eleanor's funeral procession had stopped overnight. Their construction is documented in the executors' account rolls, which survive from 1291 to March 1294, but not thereafter. By the end of that period, the crosses at Lincoln, Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans and Waltham were complete or nearly so, and those at Cheapside and Charing in progress; but those at Grantham, Stamford and Geddington apparently not yet begun. It is assumed that these last three were erected in 1294 or 1295, and that they were certainly finished before the financial crisis of 1297 which brought a halt to royal building works.Colvin 1963, pp. 483–4. A number of artists worked on the crosses, as the account rolls show, with a distinction generally drawn between the main structures, made locally under the direction of master masons appointed by the King, and the statues of Eleanor, made of Caen stone, and other sculptural details, brought from London. Master masons included Richard of Crundale, Roger of Crundale (probably Richard's brother), Michael of Canterbury, Richard of Stow, John of Battle and Nicholas Dymenge. Sculptors included Alexander of Abingdon and William of Ireland, both of whom had worked at Westminster Abbey, who were paid £3 6s. 8d. apiece for the statues; and Ralph of Chichester.

The twelve crosses were erected to mark the places where Eleanor's funeral procession had stopped overnight. Their construction is documented in the executors' account rolls, which survive from 1291 to March 1294, but not thereafter. By the end of that period, the crosses at Lincoln, Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St Albans and Waltham were complete or nearly so, and those at Cheapside and Charing in progress; but those at Grantham, Stamford and Geddington apparently not yet begun. It is assumed that these last three were erected in 1294 or 1295, and that they were certainly finished before the financial crisis of 1297 which brought a halt to royal building works.Colvin 1963, pp. 483–4. A number of artists worked on the crosses, as the account rolls show, with a distinction generally drawn between the main structures, made locally under the direction of master masons appointed by the King, and the statues of Eleanor, made of Caen stone, and other sculptural details, brought from London. Master masons included Richard of Crundale, Roger of Crundale (probably Richard's brother), Michael of Canterbury, Richard of Stow, John of Battle and Nicholas Dymenge. Sculptors included Alexander of Abingdon and William of Ireland, both of whom had worked at Westminster Abbey, who were paid £3 6s. 8d. apiece for the statues; and Ralph of Chichester.

Purpose and parallels

Eleanor's crosses appear to have been intended in part as expressions of royal power; and in part ascenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

s to encourage prayers for her soul from travellers. On the pedestal of each was inscribed the phrase ''Orate pro anima'' ("Pray for ersoul").

It was not unknown for memorial cross

A memorial cross (sometimes called an intending cross) is a cross-shaped memorial to commemorate a special event or an incident, typically where one or more people died. It may also be a simple form of headstone to commemorate the dead.

File

I ...

es to be constructed in the middle ages, although they were normally isolated instances and relatively simple in design. A cross in the Strand, near London, was said to have been erected by William II in memory of his mother, Queen Matilda (d. 1083). Henry III erected one at Merton, Surrey, for his cousin the Earl of Surrey (d. 1240). Another was erected at Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of letters, symbols, etc., especially by sight or touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process involving such areas as word recognition, orthography (spell ...

for Edward I's sister Beatrice (d. 1275). Yet another, almost contemporary with the Eleanor crosses, was erected near Windsor for Edward's mother, Eleanor of Provence

Eleanor of Provence (c. 1223 – 24/25 June 1291) was a French noblewoman who became Queen of England as the wife of King Henry III from 1236 until his death in 1272. She served as regent of England during the absence of her spouse in 1253.

A ...

(d.1291).Colvin 1963, pp. 484–85.

The closest precedent for the Eleanor crosses, and almost certainly their model, was the series of nine crosses known as ''montjoies'' erected along the funeral route of King Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the d ...

in 1271. These were elaborate structures incorporating sculptural representations of the King, and were erected in part to promote his canonisation (a campaign that in 1297 succeeded). Eleanor's crosses never aspired to this last purpose, but in design were even larger and more ornate than the ''montjoies'', being of at least three rather than two tiers.

Locations

Lincoln

()

()Eleanor rested on the first night of the journey at The Priory of Saint Katherine without Lincoln and her viscera were buried in

Lincoln Cathedral

Lincoln Cathedral, Lincoln Minster, or the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln and sometimes St Mary's Cathedral, in Lincoln, England, is a Grade I listed cathedral and is the seat of the Anglican Bishop of Lincoln. Construc ...

on 3 December 1290. The Lincoln cross was built between 1291 and 1293 by Richard of Stow at a total recorded cost of over £120, with sculptures by William of Ireland.Colvin 1963, p. 483. John Leland, in the early 1540s, noted that "a litle without Barre ateis a very fair crosse and large". It stood at Swine Green, St Catherine's, an area just outside the city at the southern end of the High Street, but had disappeared by the early 18th century. The only surviving piece is the lower half of one of the statues, rediscovered in the 19th century and now in the grounds of Lincoln Castle

Lincoln Castle is a major medieval castle constructed in Lincoln, England, during the late 11th century by William the Conqueror on the site of a pre-existing Roman fortress. The castle is unusual in that it has two mottes. It is one of only ...

.

Grantham

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 4 December 1290 in

Grantham

Grantham () is a market and industrial town in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, situated on the banks of the River Witham and bounded to the west by the A1 road. It lies some 23 miles (37 km) south of the Lincoln a ...

, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-we ...

.Powrie 1990, p. 194.Cockerill 2014, p. 345. The master mason for the cross here is not known: it was probably constructed in 1294 or 1295. It stood at the upper end of the High Street. It was pulled down during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, but in February 1647 Grantham Corporation ordered that any stones that could be traced should be recovered for public use. No part is known to survive, but it is conceivable that the substantial steps of the standing Market Cross comprise stones that originally belonged to the Eleanor Cross. A letter from the 18th-century antiquary William Stukeley

William Stukeley (7 November 1687 – 3 March 1765) was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric ...

(now untraceable) is alleged to have stated that he had one of the lions from Eleanor's coats of arms in his garden.

A modern relief stone plaque to Eleanor was installed at the Grantham Guildhall in 2015.

Stamford

()Eleanor's bier spent the night of 5 December 1290, and possibly also that of 6 December, in

Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish in the South Kesteven District of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber-framed ...

. The master mason for the cross here is not known: it was probably constructed in 1294 or 1295. There is conflicting evidence about its precise location, but it is now generally agreed that it stood just outside the town on the Great North Road (modern Casterton Road, the B1081), in what is today the Foxdale area.

The cross was in decay by the early 17th century, and in 1621 the town council ordered some restoration work, although it is unclear whether this was carried out. Richard Symonds reported in 1645: "In the hill before ye come into the towne, stands a lofty large crosse built by Edward III, in memory of Elianor his queene, whose corps rested there coming from the North." In 1646 Richard Butcher, the Town Clerk, described it as "so defaced, that only the Ruins appeare to my eye". It had probably been destroyed by 1659, and certainly by the early 18th century.

In 1745, William Stukeley

William Stukeley (7 November 1687 – 3 March 1765) was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric ...

attempted to excavate the remains of the cross, and succeeded in finding its hexagonal base and recovering several fragments of the superstructure. His sketch of the top portion, which seems to have stylistically resembled the Geddington Cross, is found in his diaries in the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

, Oxford. A single small fragment from among Stukeley's finds, a carved Purbeck marble

Purbeck Marble is a fossiliferous limestone found in the Isle of Purbeck, a peninsula in south-east Dorset, England. It is a variety of Purbeck stone that has been quarried since at least Roman times as a decorative building stone.

Geology

Strat ...

rose, was rediscovered in about 1976, and identified as part of the cross in 1993. Following the closure of Stamford Museum

Stamford Museum was located in Stamford, Lincolnshire, in Great Britain. It was housed in a Victorian building in Broad Street, Stamford, and was run by the museum services of Lincolnshire County Council from 1980 to 2011.

The building and are ...

in 2011, this fragment is now displayed in the Discover Stamford area at the town's library.

A modern monument was erected in Stamford in 2009 in commemoration of Eleanor: see Replicas and imitations below.

Geddington

()

()Eleanor's bier spent the night of either 6 or 7 December 1290, or possibly both, in Geddington,

Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It ...

. The master mason for the cross here is not known: it was probably constructed in 1294 or 1295. It was recorded by William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Annal ...

in 1607; and still stands in the centre of the village, the best-preserved of the three survivors. It is unique among the three in having a triangular plan, and a taller and more slender profile with a lower tier entirely covered with rosette diapering

Diaper is any of a wide range of decorative patterns used in a variety of works of art, such as stained glass, heraldic shields, architecture, and silverwork. Its chief use is in the enlivening of plain surfaces.

Etymology

For the full etymolog ...

, instead of the arch-and-gable motif with tracery which appears on both the others; and canopied statues surmounted by a slender hexagonal pinnacle. It is possible that the other northern crosses (Lincoln, Grantham and Stamford) were in a similar relatively simple style; and that this reflects either the need to cut back expenditure in the latter stages of the project for financial reasons, or a decision taken at the planning stage to make the crosses progressively larger and more ornate as the sequence proceeded south.

An engraving of the Geddington cross (drawn by Jacob Schnebbelie

Jacob Schnebbelie (30 August 1760 – 21 February 1792) was an English draughtsman, specialising in monuments and other historical subjects.

Early life

Jacob Schnebbelie was born in Duke's Court, St Martin's Lane, London, on 30 August 1760. His fa ...

and engraved by James Basire

James Basire (1730–1802

London), also known as James Basire Sr., was a British engraver. He is the most significant of a family of engravers, and noted for his apprenticing of the young William Blake.

Early life

His father was Isaac Basire ...

) was published by the Society of Antiquaries in its ''Vetusta Monumenta

''Vetusta Monumenta'' is the title of a published series of illustrated antiquarian papers on ancient buildings, sites and artefacts, mostly those of Britain, published at irregular intervals between 1718 and 1906 by the Society of Antiquaries o ...

'' series in 1791.Alexander and Binski 1987, p. 362. It was "discreetly" restored in 1892.

Hardingstone, Northampton

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 8 December 1290, and perhaps also that of 7 December, at

Hardingstone

Hardingstone is a village in Northamptonshire, England. It is on the southern edge of Northampton, and now forms a suburb of the town. It is about from the town centre. The Newport Pagnell road (the B526, formerly part of the A50) separates ...

, on the outskirts of Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

. The cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a sa ...

here was constructed between 1291 and 1292 by John of Battle, at a total recorded cost of over £100. William of Ireland and Ralph of Chichester carved the statues.Powrie 1990, pp. 124–26. A causeway leading from the town to the cross was constructed by Robert son of Henry.Hunter 1842, p. 183. The cross is still standing, close to Delapré Abbey

Delapré Abbey is an English neo-classical mansion in Northamptonshire.

The mansion and outbuildings incorporate remains of a former monastery, the Abbey of St Mary de la Pré (the suffix meaning "in or of the Meadow"), near the River Nene s ...

, on the side of the A508 leading out of Northampton, and just north of the junction with the A45. The King stayed nearby at Northampton Castle

Northampton Castle at Northampton, was one of the most famous Norman castles in England. The castle site was outside the western city gate, and defended on three sides by deep trenches. A branch of the River Nene provided a natural barrier on the ...

.

The monument is octagonal in shape and set on steps; the present steps are replacements. It is built in three tiers, and originally had a crowning terminal, presumably a cross. The terminal appears to have gone by 1460: there is mention of a "headless cross" at the site from which Thomas Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury, watched Margaret of Anjou

Margaret of Anjou (french: link=no, Marguerite; 23 March 1430 – 25 August 1482) was Queen of England and nominally Queen of France by marriage to King Henry VI from 1445 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471. Born in the Duchy of Lorrain ...

's flight following the Battle of Northampton. The monument was restored in 1713, to mark the Peace of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne of ...

and the end of the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

, and this work included the fitting of a new terminal in the form of a Maltese cross

The Maltese cross is a cross symbol, consisting of four " V" or arrowhead shaped concave quadrilaterals converging at a central vertex at right angles, two tips pointing outward symmetrically.

It is a heraldic cross variant which developed f ...

. Further repairs were undertaken in 1762. At a later restoration in 1840, under the direction of Edward Blore

Edward Blore (13 September 1787 – 4 September 1879) was a 19th-century English landscape and architectural artist, architect and antiquary.

Early career

He was born in Derby, the son of the antiquarian writer Thomas Blore.

Blore's backg ...

, the Maltese cross was replaced by the picturesque broken shaft which is seen today. Later, less intrusive restorations were undertaken in 1877 and 1986. Further restoration work was completed in 2019.

The bottom tier of the monument features open books. These probably included painted inscriptions of Eleanor's biography and of prayers for her soul to be said by viewers, now lost.

John Leland, in the early 1540s, recorded it as "a right goodly crosse, caullid, as I remembre, the Quenes Crosse", although he seems to have associated it with the 1460 Battle of Northampton. It is also referred to by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

in his '' Tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain'', in reporting the Great Fire of Northampton in 1675: "... a townsman being at Queen's Cross upon a hill on the south side of the town, about two miles () off, saw the fire at one end of the town then newly begun, and that before he could get to the town it was burning at the remotest end, opposite where he first saw it."

Celia Fiennes

Celia Fiennes (7 June 1662 – 10 April 1741) was an English traveller and writer. She explored England on horseback at a time when travel for its own sake was unusual, especially for women.

Early life

Born at Newton Tony, Wiltshire,"June 7th ...

in 1697 describes it as "a Cross, a mile off the town call'd High-Cross – it stands just in the middle of England – its all stone 12 stepps which runs round it, above that is the stone carv'd finely and there are 4 large Nitches about the middle, in each is the statue of some queen at length which encompasses it with other carvings as garnish, and so it rises less and less to the top like a tower or Piramidy."

An engraving of the Hardingstone cross (drawn by Jacob Schnebbelie

Jacob Schnebbelie (30 August 1760 – 21 February 1792) was an English draughtsman, specialising in monuments and other historical subjects.

Early life

Jacob Schnebbelie was born in Duke's Court, St Martin's Lane, London, on 30 August 1760. His fa ...

and engraved by James Basire

James Basire (1730–1802

London), also known as James Basire Sr., was a British engraver. He is the most significant of a family of engravers, and noted for his apprenticing of the young William Blake.

Early life

His father was Isaac Basire ...

) was published by the Society of Antiquaries in its ''Vetusta Monumenta

''Vetusta Monumenta'' is the title of a published series of illustrated antiquarian papers on ancient buildings, sites and artefacts, mostly those of Britain, published at irregular intervals between 1718 and 1906 by the Society of Antiquaries o ...

'' series in 1791.

Stony Stratford

(plaque at )

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 9 December 1290 at

(plaque at )

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 9 December 1290 at Stony Stratford

Stony Stratford is a constituent town of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. Historically it was a market town on the important route from London to Chester ( Watling Street, now the A5). It is also the name of a civil parish with a town ...

, Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-e ...

. The cross here was built between 1291 and 1293 by John of Battle at a total recorded cost of over £100. The supplier of the statues is uncertain, but some smaller carvings were provided by Ralph of Chichester. The cross stood at the lower end of the town, towards the River Ouse, on Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main R ...

(now the High Street), although its exact location is debated. It is said to have been of a tall elegant design (perhaps similar to that at Geddington). It was described by William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Annal ...

in 1607 as ''minus elegantem'' ("none of the fairest"), suggesting that it was by this date in a state of decay. It is said to have been demolished in about 1643. In 1735, William Hartley, a man of nearly 80, could remember only the base still standing.Galloway 1914, p. 73. Any trace has now vanished.

The cross is commemorated by a brass plaque on the wall of 157 High Street.

Woburn

(approximately at ) Eleanor's bier spent the night of 10 December 1290 at Woburn,Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

. Work on the cross here started in 1292, later than some of the others, and was completed in the spring of 1293. It was built by John of Battle, at a total recorded cost of over £100. As at Stony Stratford, the supplier of the statues is uncertain, but some of the carvings were provided by Ralph of Chichester. No part of the cross survives. Its precise location, and its fate, are unknown.

Dunstable

() Eleanor's bier spent the night of 11 December 1290 atDunstable

Dunstable ( ) is a market town and civil parish in Bedfordshire, England, east of the Chiltern Hills, north of London. There are several steep chalk escarpments, most noticeable when approaching Dunstable from the north. Dunstable is t ...

, Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

. It rested first in the market place, before being carried into Dunstable Priory

The Priory Church of Saint Peter, St Peter with its monastery (Dunstable Priory) was founded in 1132 by Henry I of England, Henry I for Augustinians, Augustinian Canons Regular#Canons Regular, Canons in Dunstable, Bedfordshire, England. St Pete ...

church, where the canons prayed in an overnight vigil

A vigil, from the Latin ''vigilia'' meaning ''wakefulness'' (Greek: ''pannychis'', or ''agrypnia'' ), is a period of purposeful sleeplessness, an occasion for devotional watching, or an observance. The Italian word ''vigilia'' has become genera ...

. The cross was built between 1291 and 1293 by John of Battle at a total recorded cost of over £100. Some of the sculpture was supplied by Ralph of Chichester.Hunter 1842, p. 184. It is thought to have been located in the middle of the town, probably in the market place, and was reported by William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Annal ...

as still standing in 1586. It is said to have been demolished in 1643 by troops under the Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

. No part survives, although some of the foundations are reported to have been discovered during roadworks at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Eleanor's Cross Shopping Precinct in High Street North contains a modern statue of Eleanor, erected in 1985.

St Albans

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 12 December 1290 at

()

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 12 December 1290 at St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major town on the old Roman ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

. The cross here was built between 1291 and 1293 by John of Battle at a total recorded cost of over £100, with some of the sculpture supplied by Ralph of Chichester.Powrie 1990, p. 141.Galloway 1914, p. 74. It was erected at the south end of the Market Place, and for many years stood in front of the fifteenth-century Clock Tower

Clock towers are a specific type of structure which house a turret clock and have one or more clock faces on the upper exterior walls. Many clock towers are freestanding structures but they can also adjoin or be located on top of another buildi ...

in the High Street, opposite the Waxhouse Gateway entrance to the Abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conce ...

.

In 1596, it was described as "verie stately". However, having fallen into decay, and having probably been further damaged during the Civil War, it was eventually demolished in 1701–02, to be replaced by a market cross

A market cross, or in Scots, a mercat cross, is a structure used to mark a market square in market towns, where historically the right to hold a regular market or fair was granted by the monarch, a bishop or a baron.

History

Market crosse ...

. This was demolished in turn in 1810, although the town pump it contained survived a little longer. A drinking fountain

A drinking fountain, also called a water fountain or water bubbler, is a fountain designed to provide drinking water. It consists of a basin with either continuously running water or a tap. The drinker bends down to the stream of water and s ...

was erected on the site by philanthropist Isabella Worley in 1874: this was relocated to Victoria Square nearby in the late 20th century.

A late 19th-century ceramic plaque on the Clock Tower commemorates the Eleanor cross.

Waltham (now Waltham Cross)

Eleanor's bier spent the night of 13 December 1290 in the parish of

Cheshunt

Cheshunt ( ) is a town in Hertfordshire, England, north of London on the River Lea and Lee Navigation. It contains a section of the Lee Valley Park, including much of the River Lee Country Park. To the north lies Broxbourne and Wormley, Hertfor ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

. The cross here was built in about 1291 by Roger of Crundale and Nicholas Dymenge at a total recorded cost of over £110. It probably became known as ''Waltham Cross'' because it stood at the way to Waltham Abbey

Waltham Abbey is a town and civil parish in the Epping Forest District of Essex, within the metropolitan and urban area of London, England, north-east of Charing Cross. It lies on the Greenwich Meridian, between the River Lea in the west and E ...

, across the River Lea

The River Lea ( ) is in South East England. It originates in Bedfordshire, in the Chiltern Hills, and flows southeast through Hertfordshire, along the Essex border and into Greater London, to meet the River Thames at Bow Creek. It is one of t ...

in Essex, which was clearly visible from its site. The sculpture was by Alexander of Abingdon, with some items supplied by Robert of Corfe. The cross was located outside the village of Waltham, but as the village grew into a town in the 17th and 18th centuries, it began to suffer damage from passing traffic. In 1721, at the instigation of William Stukeley

William Stukeley (7 November 1687 – 3 March 1765) was an English antiquarian, physician and Anglican clergyman. A significant influence on the later development of archaeology, he pioneered the scholarly investigation of the prehistoric ...

and at the expense of the Society of Antiquaries, two oak bollard

A bollard is a sturdy, short, vertical post. The term originally referred to a post on a ship or quay used principally for mooring boats. It now also refers to posts installed to control road traffic and posts designed to prevent automotive v ...

s were erected "to secure Waltham Cross from injury by carriages". The bollards were subsequently removed by the turnpike commissioners, and in 1757 Stukeley arranged for a protective brick plinth to be erected instead, at the expense of Lord Monson.Alexander and Binski 1987, p. 363. The cross is still standing, but has been restored on several occasions, in 1832–34, 1885–92, 1950–53, and 1989–90.

The Society of Antiquaries published an engraving of the cross by George Vertue

George Vertue (1684 – 24 July 1756) was an English engraver and antiquary, whose notebooks on British art of the first half of the 18th century are a valuable source for the period.

Life

Vertue was born in 1684 in St Martin-in-the-Fields, ...

from a drawing by Stukeley in its ''Vetusta Monumenta

''Vetusta Monumenta'' is the title of a published series of illustrated antiquarian papers on ancient buildings, sites and artefacts, mostly those of Britain, published at irregular intervals between 1718 and 1906 by the Society of Antiquaries o ...

'' series in 1721; and another, engraved by James Basire

James Basire (1730–1802

London), also known as James Basire Sr., was a British engraver. He is the most significant of a family of engravers, and noted for his apprenticing of the young William Blake.

Early life

His father was Isaac Basire ...

from a drawing by Jacob Schnebbelie

Jacob Schnebbelie (30 August 1760 – 21 February 1792) was an English draughtsman, specialising in monuments and other historical subjects.

Early life

Jacob Schnebbelie was born in Duke's Court, St Martin's Lane, London, on 30 August 1760. His fa ...

, in the same series in 1791.

The original statues of Eleanor, which were extremely weathered, were replaced by replicas at the 1950s restoration. The originals were kept for some years at Cheshunt Public Library; but they were removed, possibly in the 1980s, and are now held by the Victoria & Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

. A photograph formerly on the Lowewood Museum website shows one of the original statues in front of a staircase at the library.

Westcheap (now Cheapside)

()

Eleanor's bier reached the

()

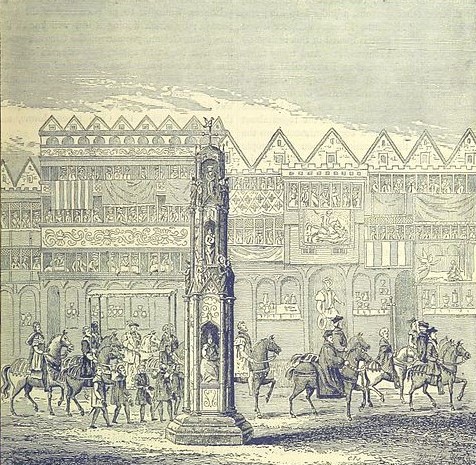

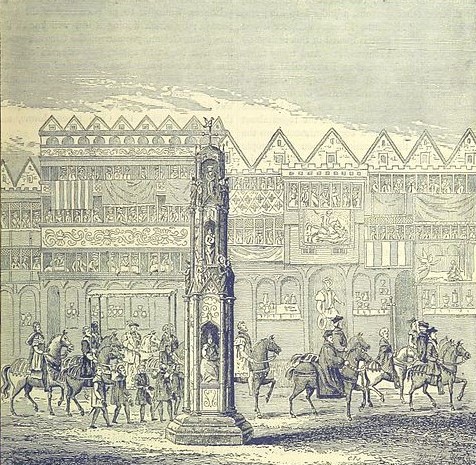

Eleanor's bier reached the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

on 14 December 1290, and a site for the cross was selected in Westcheap (now Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, whe ...

). Her heart was buried in the Blackfriars priory on 19 December. The Cheapside cross was built from 1291 onwards by Michael of Canterbury at a total recorded cost of £226 13s. 4d.Powrie 1990, p. 165.

Under a licence granted by Henry VI in 1441, the cross was extensively restored or rebuilt in 1484–86. It was subsequently regilded several times in the 16th century on the occasion of coronations and royal visits to the City.Powrie 1990, pp. 165–66. John Stow

John Stow (''also'' Stowe; 1524/25 – 5 April 1605) was an English historian and antiquarian. He wrote a series of chronicles of English history, published from 1565 onwards under such titles as ''The Summarie of Englyshe Chronicles'', ''The C ...

included a detailed account of the cross and its history in his ''Survay of London'' of 1598, updating it in 1603.

Although a number of images of the cross and its eventual destruction are known, these all postdate its various refurbishments, and so provide no certain guide to its original appearance. However, the chronicler Walter of Guisborough

Walter of GuisboroughWalter of Gisburn, Walterus Gisburnensis. Previously known to scholars as Walter of Hemingburgh (John Bale seems to have been the first to call him that).Sometimes known erroneously as Walter Hemingford, Latin chronicler of t ...

refers to this and Charing Cross as being fashioned of "marble"; and it is likely that it was similar to the Hardingstone and Waltham Crosses, but even more ornate and boasting some Purbeck marble

Purbeck Marble is a fossiliferous limestone found in the Isle of Purbeck, a peninsula in south-east Dorset, England. It is a variety of Purbeck stone that has been quarried since at least Roman times as a decorative building stone.

Geology

Strat ...

facings.

The cross came to be regarded as something of a public hazard, both as a traffic obstruction and because of concerns about fragments of stone falling off; while in the post-Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

period some of its Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

imagery aroused resentment, and elements were defaced in 1581, 1599 and 1600–01. Matters came to a head during the years leading up to the Civil War. To puritanical reformers, it was identified with Dagon

Dagon ( he, דָּגוֹן, ''Dāgōn'') or Dagan ( sux, 2= dda-gan, ; phn, 𐤃𐤂𐤍, Dāgān) was a god worshipped in ancient Syria across the middle of the Euphrates, with primary temples located in Tuttul and Terqa, though many attes ...

, the ancient god of the Philistines

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

, and was seen as the embodiment of royal and Catholic tradition. At least one riot was fought in its shadow, as opponents of the cross descended upon it to pull it down, and supporters rallied to stop them. After Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

had fled London to raise an army, the destruction of the cross was almost the first order of business for the Parliamentary Committee for the Demolition of Monuments of Superstition and Idolatry, led by Sir Robert Harley

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English language, English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist i ...

, and it was demolished on 2 May 1643. The downfall of the Cheapside Cross is an important episode of iconoclasm

Iconoclasm (from Ancient Greek, Greek: grc, wikt:εἰκών, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, wikt:κλάω, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, wikt:εἰκών, εἰκών + wi ...

in English history.

Two Purbeck marble fragments of the original cross, displaying shields bearing the royal arms of England

The royal arms of England are the Coat of arms, arms first adopted in a fixed form at the start of the age of heraldry (circa 1200) as Armorial of the House of Plantagenet, personal arms by the House of Plantagenet, Plantagenet kings who ruled ...

and of Castile and León

Castile and León ( es, Castilla y León ; ast-leo, Castiella y Llión ; gl, Castela e León ) is an autonomous community in northwestern Spain.

It was created in 1983, eight years after the end of the Francoist regime, by the merging of the ...

, were recovered in 1838 during reconstruction of the sewer in Cheapside. They are now held by the Museum of London

The Museum of London is a museum in London, covering the history of the UK's capital city from prehistoric to modern times. It was formed in 1976 by amalgamating collections previously held by the City Corporation at the Guildhall, London, Gui ...

.

Charing (now Charing Cross)

()

Eleanor's bier spent the final night of its journey, 16 December 1290, in the

()

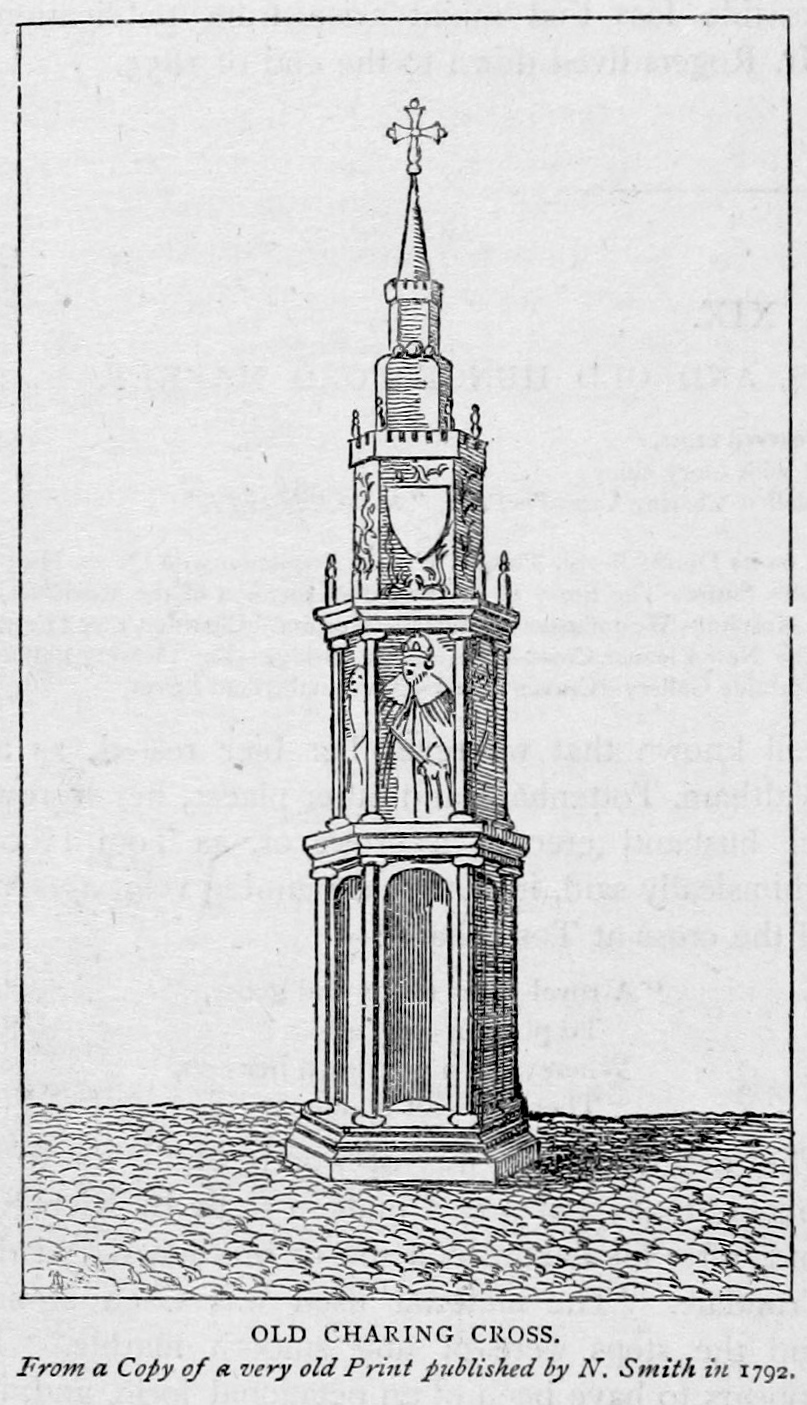

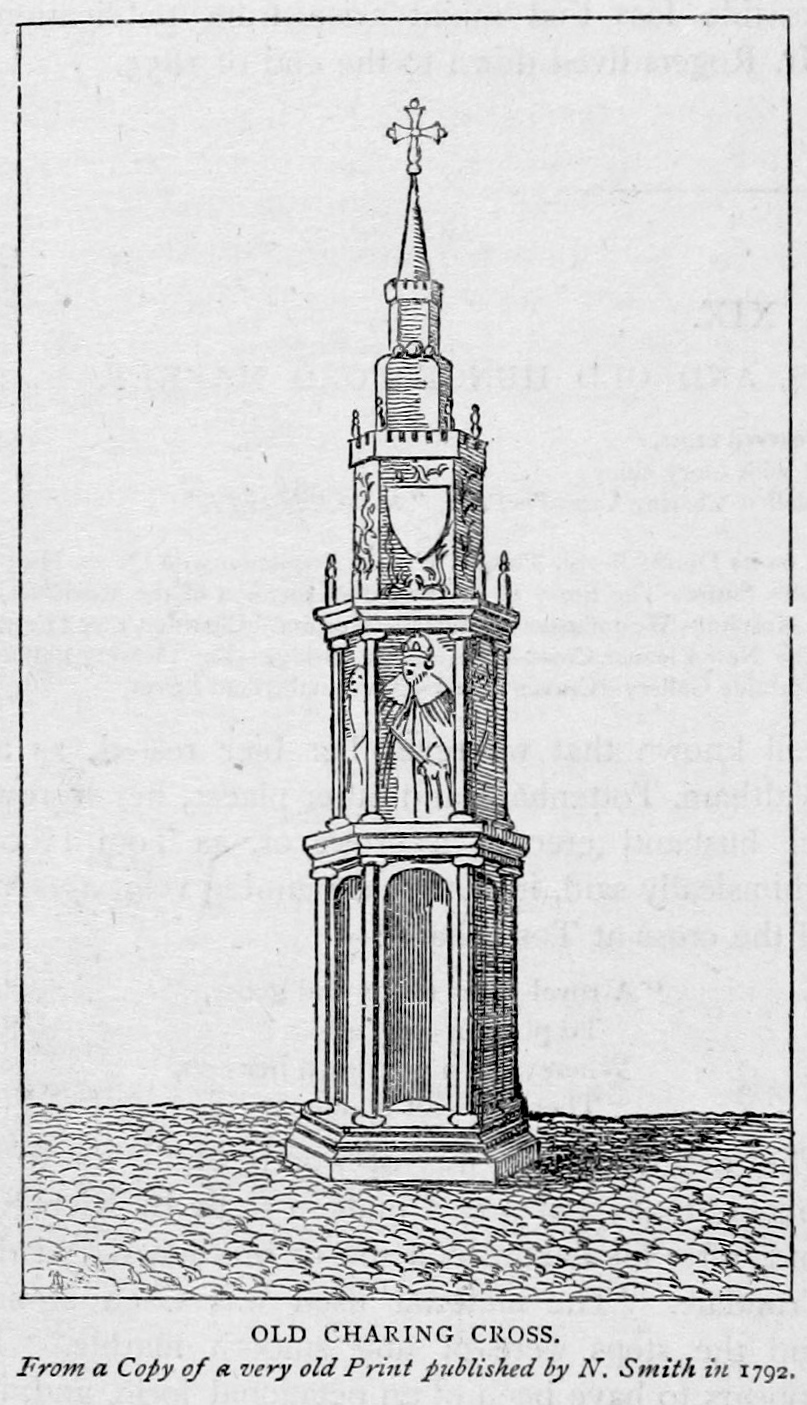

Eleanor's bier spent the final night of its journey, 16 December 1290, in the Royal Mews

The Royal Mews is a mews, or collection of equestrian stables, of the British Royal Family. In London these stables and stable-hands' quarters have occupied two main sites in turn, being located at first on the north side of Charing Cross, an ...

at Charing, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, a few hundred yards north of Westminster Abbey. The area subsequently became known as Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City ...

. The cross here was the most expensive of the twelve, built of Purbeck marble

Purbeck Marble is a fossiliferous limestone found in the Isle of Purbeck, a peninsula in south-east Dorset, England. It is a variety of Purbeck stone that has been quarried since at least Roman times as a decorative building stone.

Geology

Strat ...

from 1291 onwards by Richard of Crundale, the senior royal mason, with the sculptures supplied by Alexander of Abingdon, and some items by Ralph de Chichester. Richard died in the autumn of 1293, and the work was completed by Roger of Crundale, probably his brother. The total recorded cost was over £700.

The cross stood outside the Royal Mews, at the top of what is now Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

, and on the south side of what is now Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson commemo ...

. John Norden

John Norden (1625) was an English cartographer, chorographer and antiquary. He planned (but did not complete) a series of county maps and accompanying county histories of England, the '' Speculum Britanniae''. He was also a prolific writer ...

in about 1590 described it as the "most stately" of the series, but by this date so "defaced by antiquity" as to have become "an old weather-beaten monument". It was also noted by William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Annal ...

in 1607.

It was ordered to be taken down by Parliament in 1643, and was eventually demolished in 1647. Following the demolition, a contemporary ballad ran:

After theUndone! undone! the lawyers cry, They ramble up and down; We know not the way to ''Westminster'' Now ''Charing-Cross'' is down.

Restoration of Charles II

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to be ...

, an equestrian statue of Charles I by Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur (c. 1580 – 1658) was a French sculptor with the contemporaneous reputation of having trained in Giambologna's Florentine workshop. He assisted Giambologna's foreman, Pietro Tacca, in Paris, in finishing and erecting the equestr ...

was erected on the site of the cross in 1675, and this still stands. The location is still known as Charing Cross, and since the early 19th century this point has been regarded as the official centre of London, in legislation and when measuring distances from London.

A new Eleanor cross was erected in 1865 outside Charing Cross railway station

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via Ashf ...

, several hundred yards from the original site: see Replicas and imitations below.

A mural by David Gentleman

David William Gentleman (born 11 March 1930) is an English artist. He studied art and painting at the Royal College of Art under Edward Bawden and John Nash. He has worked in watercolour, lithography and wood engraving, at scales ranging from ...

on the platform walls of Charing Cross underground station

Charing Cross (sometimes informally abbreviated as Charing +, Charing X, CHX or CH+) is a London Underground station at Charing Cross in the City of Westminster. The station is served by the Bakerloo and Northern lines and provides an inter ...

, commissioned by London Transport in 1978, depicts, in the form of wood engraving

Wood engraving is a printmaking technique, in which an artist works an image or ''matrix'' of images into a block of wood. Functionally a variety of woodcut, it uses relief printing, where the artist applies ink to the face of the block and ...

s, the story of the building of the medieval cross by stonemasons and sculptors.

Folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

holds that the name Charing derives from French ' (dear queen); but the name "Charing" for the area in fact pre-dates Eleanor's death and probably comes from the Anglo-Saxon word ', meaning a bend, as it stands on the outside of a sharp bend in the River Thames (compare Charing

Charing is a village and civil parish in the Ashford District of Kent, in south-east England. It includes the settlements of Charing Heath and Westwell Leacon. It is located at the foot of the North Downs and reaches up to the escarpment.

T ...

in Kent).

Replicas and imitations

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries several replica Eleanor crosses, or monuments more loosely inspired by them, were erected. *The cross atIlam, Staffordshire

Ilam () is a village in the Staffordshire Peak District of England, lying on the River Manifold. The population of the civil parish as taken at the 2011 census was 402.

Ilam village

Ilam is best known as the location of the neo-Gothic Ilam ...

, was built in 1840 by Jesse Watts-Russell of Ilam Hall

Ilam Park is a country park situated in Ilam, on both banks of the River Manifold five miles (8 km) north west of Ashbourne, England, and in the ownership of the National Trust. The property is managed as part of the Trust's White Peak E ...

to commemorate his wife, Mary.

*The Martyrs' Memorial

The Martyrs' Memorial is a stone monument positioned at the intersection of St Giles' Street, Oxford, St Giles', Magdalen Street and Beaumont Street, to the west of Balliol College, Oxford, England. It commemorates the 16th-century Oxford Mar ...

in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, commemorating the 16th-century Oxford Martyrs

The Oxford Martyrs were Protestants tried for heresy in 1555 and burnt at the stake in Oxford, England, for their religious beliefs and teachings, during the Marian persecution in England.

The three martyrs were the Church of England bishop ...

, was erected in 1841–43 to the designs of George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

.

*The Glastonbury Market Cross

Glastonbury Market Cross is a market cross in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Erected in 1846, it was designed by the English architect Benjamin Ferrey and has been a Grade II listed structure since 1950.

History

Glastonbury's cross replaced an e ...

, Somerset, was erected in 1846 to the designs of Benjamin Ferrey

Benjamin Ferrey FSA FRIBA (1 April 1810–22 August 1880) was an English architect who worked mostly in the Gothic Revival.

Family

Benjamin Ferrey was the youngest son of Benjamin Ferrey Snr (1779–1847), a draper who became Mayor of Christc ...

.

*Banbury Cross

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshire ...

, Oxfordshire, was erected in 1859 to commemorate the marriage of Victoria, Princess Royal

Victoria, Princess Royal (Victoria Adelaide Mary Louisa; 21 November 1840 – 5 August 1901) was German Empress and Queen of Prussia as the wife of German Emperor Frederick III. She was the eldest child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingd ...

to Prince Frederick of Prussia: it was designed by John Gibbs.

*The Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross at Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City ...

in London was erected in 1865 outside Charing Cross railway station

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via Ashf ...

on the Strand, a few hundred yards to the east of the site of the medieval cross. It does not pretend to be a faithful copy of the original, being larger and more ornate. It stands high and was commissioned by the South Eastern Railway Company for their newly opened Charing Cross Hotel. The cross was designed by the hotel architect, E. M. Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

, who is also known for his work on Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

. It was constructed by Thomas Earp Thomas Earp may refer to:

* Thomas Earp (politician)

* Thomas Earp (sculptor)

Thomas Earp (1828–1893) was a British sculptor and architectural carver who was active in the late 19th century. His best known work is his 1863 reproduction of t ...

of Lambeth from Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building sto ...

, Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market tow ...

stone (a fine sandstone) and Aberdeen granite. It was restored to a substantial extent in 2009–10.

*The Ellesmere Memorial at Walkden

Walkden is a town in the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England, northwest of Salford, and of Manchester.

Historically in the township of Worsley in Lancashire, Walkden was a centre for coal mining and textile manufacture.

In 2014, ...

, Lancashire, was erected in 1868 to the designs of T. G. Jackson to commemorate Harriet (d. 1866), wife of the 1st Earl of Ellesmere. It originally stood at a road junction, but was moved into the churchyard in 1968.

*The Albert Memorial

The Albert Memorial, directly north of the Royal Albert Hall in Kensington Gardens, London, was commissioned by Queen Victoria in memory of her beloved husband Prince Albert, who died in 1861. Designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the Gothic ...

, in Kensington Gardens

Kensington Gardens, once the private gardens of Kensington Palace, are among the Royal Parks of London. The gardens are shared by the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and sit immediately to the west of Hyde P ...

, London, commissioned by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

in memory of her husband Prince Albert, and opened in 1872, was a far larger structure than any of the Eleanor crosses, but took inspiration from them. Its architect, Sir Gilbert Scott, claimed to have "adopt din my design the style at once most congenial with my own feelings, and that of the most touching monuments ever erected in this country to a Royal Consort – the exquisite 'Eleanor Crosses'".

* The Loudoun Monument, Ashby-de-la-Zouch

Ashby-de-la-Zouch, sometimes spelt Ashby de la Zouch () and shortened locally to Ashby, is a market town and civil parish in the North West Leicestershire district of Leicestershire, England. The town is near to the Derbyshire and Staffordshire ...

, Leicestershire, was designed by Sir Gilbert Scott and erected in 1879 to commemorate Edith Rawdon-Hastings, 10th Countess of Loudoun

Edith Maud Rawdon-Hastings, 10th Countess of Loudoun (10 December 1833 – 23 January 1874) was a Scottish peer. She died aged 40 after caring for Rowallan Castle. Sir George Gilbert Scott designed an Eleanor Cross style monument to her which w ...

(d. 1874), wife of Charles Frederick Abney-Hastings.

*The Sledmere Cross

A replica Eleanor Cross was erected in Sledmere, East Riding of Yorkshire, in 1896–98. The tall stone structure was constructed by the Sykes family of Sledmere. Engraved monumental brasses were added after the First World War, converting ...

was erected in Sledmere

Sledmere is a village in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, about north-west of Driffield on the B1253 road.

The village lies in a civil parish which is also officially called "Sledmere" by the Office for National Statistics, although th ...

, East Riding of Yorkshire

The East Riding of Yorkshire, or simply East Riding or East Yorkshire, is a ceremonial county and unitary authority area in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and west, South Yorkshire to t ...

, in 1896–8, commissioned by Sir Tatton Sykes and designed by Temple Lushington Moore

Temple Lushington Moore (7 June 1856 – 30 June 1920) was an English architect who practised in London. He is famed for a series of fine Gothic Revival churches built between about 1890 and 1917 and also restored many churches and designed c ...

. Sir Tatton's son, Sir Mark Sykes, later added engraved brasses to turn it into a war memorial.

*The Queen Victoria Monument, Birkenhead, Wirral, Merseyside, designed by Edmund Kirby

Edmund Kirby (8 April 1838 – 24 April 1920) was an English architect. He was born in Liverpool, and educated at Oscott College in Birmingham. He was articled to E. W. Pugin in London, then became an assistant to John Douglas in Chest ...

, was unveiled in 1905.

*A modern monument inspired by the lost medieval cross was erected in Stamford in 2009. It was designed by Wolfgang Buttress

Wolfgang Buttress (born 1965) is an English artist. He creates multi-sensory artworks that draw inspiration from our evolving relationship with the natural world. Buttress explores and interprets scientific discoveries, collaborating with archi ...

and sponsored by the Smith of Derby Group

Founded in 1856, the Smith of Derby Group are clockmakers based in Derby, England. Smith of Derby has been in operation continuously under five generations of the Smith family.

History

John Smith (21 December 1813 - 1886)

Ilam.jpg, Ilam Cross, 1840

Martyrs' Memorial, Oxford, UK - 20130709.JPG,

A link to a short article with images describing the likely circumstances surrounding the transfer of Queen Eleanor's body to Westminster

*

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Eleanor Cross Buildings and structures completed in the 13th century Monuments and memorials in England Death customs Medieval European sculptures Grade I listed buildings in Hertfordshire British sculpture History of Lincolnshire History of Northamptonshire History of Hertfordshire Monumental crosses in England Edward I of England Scheduled monuments in Hertfordshire Wayside crosses Stone crosses in the United Kingdom Lost works of art

Martyrs' Memorial, Oxford

The Martyrs' Memorial is a stone monument positioned at the intersection of St Giles', Magdalen Street and Beaumont Street

Beaumont Street is a street in the centre of Oxford, England.

The street was laid out from 1828 to 1837 with el ...

, 1841

Glastonbury. Market Cross 1.jpg, Glastonbury Market Cross

Glastonbury Market Cross is a market cross in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Erected in 1846, it was designed by the English architect Benjamin Ferrey and has been a Grade II listed structure since 1950.

History

Glastonbury's cross replaced an e ...

, 1846

Banbury Cross 1.JPG, Banbury Cross

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshire ...

, 1859

Eleanor Cross, Strand (geograph 5380147).jpg, Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City; ...

, London, 1865

Ellesmere Memorial, Walkden.jpg, Ellesmere Memorial, Walkden

Walkden is a town in the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England, northwest of Salford, and of Manchester.

Historically in the township of Worsley in Lancashire, Walkden was a centre for coal mining and textile manufacture.

In 2014, ...

, 1868

Albert Memorial, London - May 2008.jpg, Albert Memorial

The Albert Memorial, directly north of the Royal Albert Hall in Kensington Gardens, London, was commissioned by Queen Victoria in memory of her beloved husband Prince Albert, who died in 1861. Designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the Gothic ...

, London, 1872

Loudon Monument.jpg, Loudoun Memorial, Ashby-de-la-Zouch

Ashby-de-la-Zouch, sometimes spelt Ashby de la Zouch () and shortened locally to Ashby, is a market town and civil parish in the North West Leicestershire district of Leicestershire, England. The town is near to the Derbyshire and Staffordshire ...

, 1879

War Memorial, Sledmere.JPG, Sledmere Cross

A replica Eleanor Cross was erected in Sledmere, East Riding of Yorkshire, in 1896–98. The tall stone structure was constructed by the Sykes family of Sledmere. Engraved monumental brasses were added after the First World War, converting ...

, 1896

Monument to Queen Victoria, Hamilton Square, Birkenhead 2.JPG, Queen Victoria Monument, Birkenhead, 1905

Stamford Eleanor cross modern sculpture.JPG, The modern sculpture to Eleanor in Stamford, 2009

References

Further reading

* * n edition of the account rolls documenting payments for the construction of the crosses and monuments, 1291–94* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

A link to a short article with images describing the likely circumstances surrounding the transfer of Queen Eleanor's body to Westminster

*

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Eleanor Cross Buildings and structures completed in the 13th century Monuments and memorials in England Death customs Medieval European sculptures Grade I listed buildings in Hertfordshire British sculpture History of Lincolnshire History of Northamptonshire History of Hertfordshire Monumental crosses in England Edward I of England Scheduled monuments in Hertfordshire Wayside crosses Stone crosses in the United Kingdom Lost works of art