social critic

Social criticism is a form of academic or journalistic criticism focusing on social issues in contemporary society, in particular with respect to perceived injustices and power relations in general.

Social criticism of the Enlightenment

The or ...

, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects", and he is perhaps best known for his series '' A Harlot's Progress'', '' A Rake's Progress'' and '' Marriage A-la-Mode''. Knowledge of his work is so pervasive that satirical political illustrations in this style are often referred to as "Hogarthian".

Hogarth was born in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

to a lower-middle-class family. In his youth he took up an apprenticeship with an engraver, but did not complete the apprenticeship. His father underwent periods of mixed fortune, and was at one time imprisoned in lieu of outstanding debts, an event that is thought to have informed William's paintings and prints with a hard edge.

Influenced by French and Italian painting and engraving, Hogarth's works are mostly satirical caricatures, sometimes bawdily sexual, mostly of the first rank of realistic portraiture. They became widely popular and mass-produced via prints in his lifetime, and he was by far the most significant English artist of his generation. Charles Lamb deemed Hogarth's images to be books, filled with "the teeming, fruitful, suggestive meaning of words. Other pictures we look at; his pictures we read."

Early life

William Hogarth was born at Bartholomew Close in London to Richard Hogarth, a poorLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

school teacher and textbook writer, and Anne Gibbons. In his youth he was apprenticed to the engraver Ellis Gamble in Leicester Fields, where he learned to engrave trade cards and similar products.

Young Hogarth also took a lively interest in the street life of the metropolis and the London fairs, and amused himself by sketching the characters he saw. Around the same time, his father, who had opened an unsuccessful Latin-speaking coffee house at St John's Gate, was imprisoned for debt in the Fleet Prison for five years. Hogarth never spoke of his father's imprisonment.

In 1720, Hogarth enrolled at the original St Martin's Lane Academy in Peter Court, London, which was run by Louis Chéron and John Vanderbank. He attended alongside other future leading figures in art and design, such as Joseph Highmore, William Kent, and Arthur Pond

Arthur Pond (–1758) was an English painter and engraver.

Life

Born about 1705, he was educated in London, and stayed for a time in Rome studying art, in company with the sculptor Roubiliac. He became a successful portrait-painter.

From ...

. However, the academy seems to have stopped operating in 1724, at around the same time that Vanderbank fled to France in order to avoid creditors. Hogarth recalled of the first incarnation of the academy: "this lasted a few years but the treasurer sinking the subscription money the lamp stove etc were seized for rent and the whole affair put a stop to." Hogarth then enrolled in another drawing school, in Covent Garden, shortly after it opened in November 1724, which was run by Sir James Thornhill

Sir James Thornhill (25 July 1675 or 1676 – 4 May 1734) was an English painter of historical subjects working in the Italian baroque tradition. He was responsible for some large-scale schemes of murals, including the "Painted Hall" at the R ...

, serjeant painter

The Serjeant Painter was an honourable and lucrative position as court painter with the English monarch. It carried with it the prerogative of painting and gilding all of the King's residences, coaches, banners, etc. and it grossed over £1,000 ...

to the king In the British English-speaking world, The King refers to:

* Charles III (born 1948), King of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms since 2022

As a nickname

* Michael Jackson (1958–2009), American singer and pop icon, nicknamed "T ...

. On Thornhill, Hogarth later claimed that, even as an apprentice, "the painting of St Pauls and gree ich hospital … were during this time runing in my head", referring to the massive schemes of decoration painted by Thornhill for the dome of St Paul's Cathedral, and Greenwich Hospital.

Hogarth became a member of the Rose and Crown Club, with Peter Tillemans, George Vertue, Michael Dahl, and other artists and connoisseurs.

Career

By April 1720, Hogarth was an engraver in his own right, at first engraving coats of arms and shop bills and designing plates for booksellers. In 1727, he was hired by Joshua Morris, a tapestry worker, to prepare a design for the ''Element of Earth''. Morris heard that he was "an engraver, and no painter", and consequently declined the work when completed. Hogarth accordingly sued him for the money in the Westminster Court, where the case was decided in his favour on 28 May 1728.Ronald Paulson, ''Hogarth'', vol. 3 (New Brunswick 1993), pp. 213–216.Early works

Early satirical works included an '' Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme'' (c. 1721, published 1724), about the disastrous stock market crash of 1720, known as the South Sea Bubble, in which many English people lost a great deal of money. In the bottom left corner, he shows

Early satirical works included an '' Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme'' (c. 1721, published 1724), about the disastrous stock market crash of 1720, known as the South Sea Bubble, in which many English people lost a great deal of money. In the bottom left corner, he shows Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

, and Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

figures gambling, while in the middle there is a huge machine, like a merry-go-round, which people are boarding. At the top is a goat, written below which is "Who'l Ride". The people are scattered around the picture with a sense of disorder, while the progress of the well dressed people towards the ride in the middle shows the foolishness of the crowd in buying stock in the South Sea Company, which spent more time issuing stock than anything else.

Other early works include ''The Lottery'' (1724); ''The Mystery of Masonry brought to Light by the Gormagons

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in En ...

'' (1724); ''A Just View of the British Stage

''A Just View of the British Stage'' or ''Three Heads are Better than One'' is an unsigned 1724 engraving attributed to the English artist William Hogarth. It is a satirical view of the management of British plays and mocks the subjects as dege ...

'' (1724); some book illustrations; and the small print '' Masquerades and Operas'' (1724). The latter is a satire on contemporary follies, such as the masquerades of the Swiss impresario John James Heidegger, the popular Italian opera singers, John Rich's pantomimes at Lincoln's Inn Fields, and the exaggerated popularity of Lord Burlington's protégé, the architect and painter William Kent. He continued that theme in 1727, with the ''Large Masquerade Ticket

Large means of great size.

Large may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Arbitrarily large, a phrase in mathematics

* Large cardinal, a property of certain transfinite numbers

* Large category, a category with a proper class of objects and morphisms (o ...

''.

In 1726, Hogarth prepared twelve large engravings illustrating Samuel Butler's '' Hudibras''.

These he himself valued highly, and they are among his best early works, though they are based on small book illustrations.

In the following years, he turned his attention to the production of small " conversation pieces" (i.e., groups in oil of full-length portraits from high. Among his efforts in oil between 1728 and 1732 were '' The Fountaine Family'' (c.1730), ''

In 1726, Hogarth prepared twelve large engravings illustrating Samuel Butler's '' Hudibras''.

These he himself valued highly, and they are among his best early works, though they are based on small book illustrations.

In the following years, he turned his attention to the production of small " conversation pieces" (i.e., groups in oil of full-length portraits from high. Among his efforts in oil between 1728 and 1732 were '' The Fountaine Family'' (c.1730), ''The Assembly at Wanstead House

''The Assembly at Wanstead House'' is a c. 1728–1732 group portrait painting by the English artist William Hogarth. It is now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylv ...

'', ''The House of Commons examining Bambridge

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in E ...

'', and several pictures of the chief actors in John Gay's popular '' The Beggar's Opera''. One of his real-life subjects was Sarah Malcolm, whom he sketched two days before her execution.

One of Hogarth's masterpieces of this period is the depiction of an amateur performance by children of John Dryden's '' The Indian Emperour, or The Conquest of Mexico by Spaniards, being the Sequel of The Indian Queen'' (1732–1735) at the home of John Conduitt

John Conduitt (; c. 8 March 1688 – 23 May 1737), of Cranbury Park, Hampshire, was a British landowner and Whig politician. He sat in the House of Commons from 1721 to 1737. He was married to the half-niece of Sir Isaac Newton, whom Conduitt ...

, master of the mint, in St George's Street, Hanover Square.

Hogarth's other works in the 1730s include '' A Midnight Modern Conversation'' (1733), ''Southwark Fair

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed d ...

'' (1733), '' The Sleeping Congregation'' (1736), ''Before'' and ''After'' (1736), ''Scholars at a Lecture

A scholar is a person who pursues academic and intellectual activities, particularly academics who apply their intellectualism into expertise in an area of study. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researche ...

'' (1736), '' The Company of Undertakers'' (1736), ''The Distrest Poet

''The Distrest Poet'' is an oil painting produced sometime around 1736 by the British artist William Hogarth. Reproduced as an etching and engraving, it was published in 1741 from a third state plate produced in 1740. The scene was probably insp ...

'' (1736), ''The Four Times of the Day

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in En ...

'' (1738), and '' Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn'' (1738). He might also have printed ''Burlington Gate'' (1731), evoked by Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

's Epistle to Lord Burlington, and defending Lord Chandos, who is therein satirized. This print gave great offence, and was suppressed. However, modern authorities such as Ronald Paulson no longer attribute it to Hogarth.

Moralizing art

''Harlot's Progress'' and ''Rake's Progress''

In 1731, Hogarth completed the earliest of his series of moral works, a body of work that led to wide recognition. The collection of six scenes was entitled '' A Harlot's Progress'' and appeared first as paintings (now lost) before being published as engravings. ''A Harlot's Progress'' depicts the fate of a country girl who begins prostituting – the six scenes are chronological, starting with a meeting with a

In 1731, Hogarth completed the earliest of his series of moral works, a body of work that led to wide recognition. The collection of six scenes was entitled '' A Harlot's Progress'' and appeared first as paintings (now lost) before being published as engravings. ''A Harlot's Progress'' depicts the fate of a country girl who begins prostituting – the six scenes are chronological, starting with a meeting with a bawd

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

and ending with a funeral ceremony that follows the character's death from venereal disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and ora ...

.

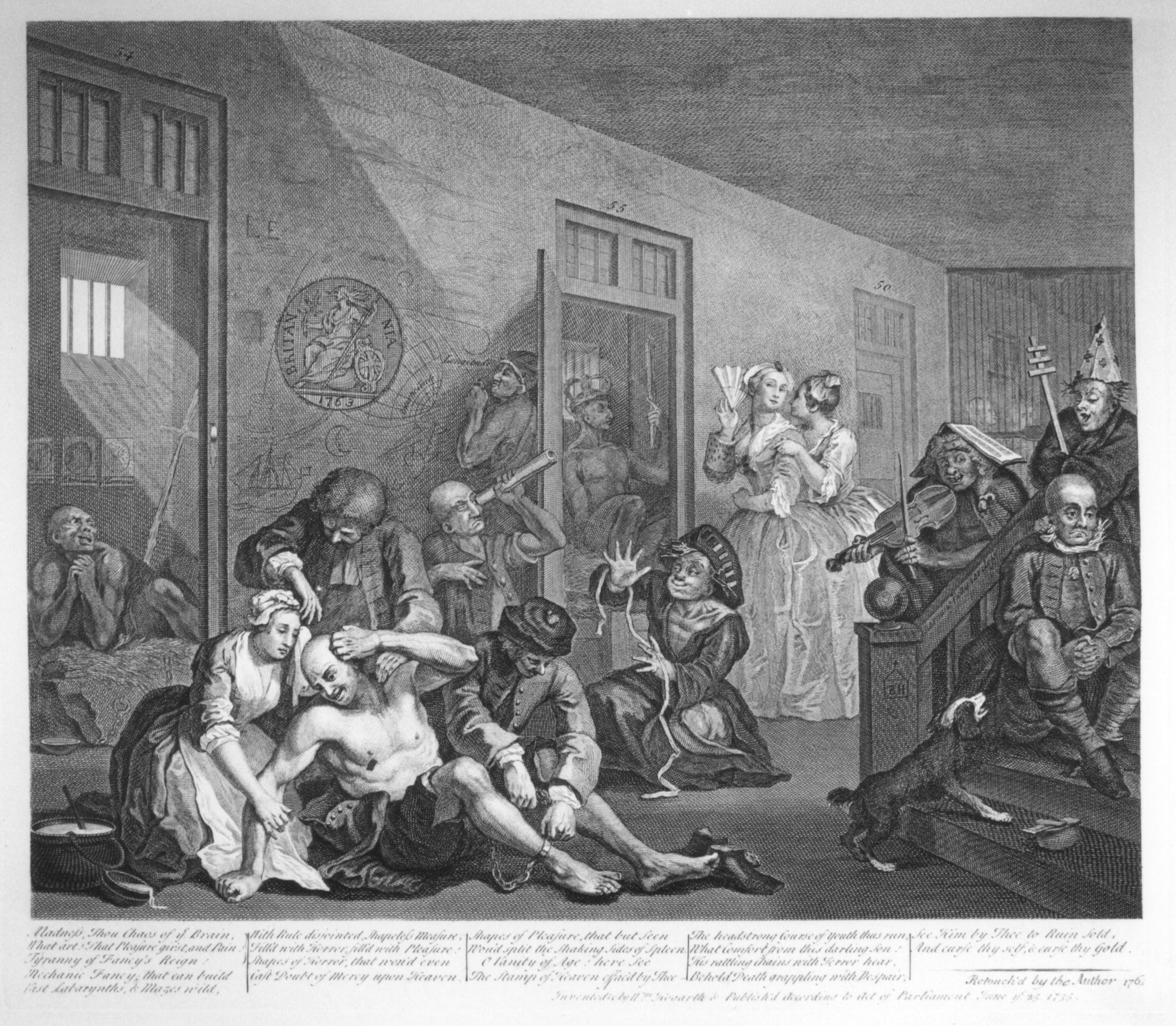

The inaugural series was an immediate success and was followed in 1733–1735 by the sequel '' A Rake's Progress''. The second instalment consisted of eight pictures that depicted the reckless life of Tom Rakewell, the son of a rich merchant, who spends all of his money on luxurious living, services from prostitutes, and gambling – the character's life ultimately ends in Bethlem Royal Hospital. The original paintings of ''A Harlot's Progress'' were destroyed in the fire at Fonthill House in 1755; the oil paintings of ''A Rake's Progress'' (1733–34) are displayed in the gallery room at Sir John Soane's Museum, London, UK.

When the success of ''A Harlot's Progress'' and ''A Rake's Progress'' resulted in numerous pirated reproductions by unscrupulous printsellers, Hogarth lobbied in parliament for greater legal control over the reproduction of his and other artists' work. The result was the Engravers' Copyright Act

The Engraving Copyright Act 1734 or Engravers' Copyright Act (8 Geo.2 c.13) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain first read on 4 March 1734/35 and eventually passed on 25 June 1735 to give protections to producers of engravings. It is al ...

(known as 'Hogarth's Act'), which became law on 25 June 1735 and was the first copyright law to deal with visual works as well as the first to recognise the authorial rights of an individual artist.

''Marriage A-la-Mode''

In 1743–1745, Hogarth painted the six pictures of '' Marriage A-la-Mode'' ( National Gallery, London), a pointed skewering of upper-class 18th-century society. This moralistic warning shows the miserable tragedy of an ill-considered marriage for money. This is regarded by many as his finest project and may be among his best-planned story serials.

Marital ethics were the topic of much debate in 18th-century Britain. The many marriages of convenience and their attendant unhappiness came in for particular criticism, with a variety of authors taking the view that love was a much sounder basis for marriage. Hogarth here painted a satire – a genre that by definition has a moral point to convey – of a conventional marriage within the English upper class. All the paintings were engraved and the series achieved wide circulation in print form. The series, which is set in a Classical interior, shows the story of the fashionable marriage of Viscount Squanderfield, the son of bankrupt Earl Squander, to the daughter of a wealthy but miserly city merchant, starting with the signing of a marriage contract at the Earl's grand house and ending with the murder of the son by his wife's lover and the suicide of the daughter after her lover is hanged at Tyburn for murdering her husband.

In 1743–1745, Hogarth painted the six pictures of '' Marriage A-la-Mode'' ( National Gallery, London), a pointed skewering of upper-class 18th-century society. This moralistic warning shows the miserable tragedy of an ill-considered marriage for money. This is regarded by many as his finest project and may be among his best-planned story serials.

Marital ethics were the topic of much debate in 18th-century Britain. The many marriages of convenience and their attendant unhappiness came in for particular criticism, with a variety of authors taking the view that love was a much sounder basis for marriage. Hogarth here painted a satire – a genre that by definition has a moral point to convey – of a conventional marriage within the English upper class. All the paintings were engraved and the series achieved wide circulation in print form. The series, which is set in a Classical interior, shows the story of the fashionable marriage of Viscount Squanderfield, the son of bankrupt Earl Squander, to the daughter of a wealthy but miserly city merchant, starting with the signing of a marriage contract at the Earl's grand house and ending with the murder of the son by his wife's lover and the suicide of the daughter after her lover is hanged at Tyburn for murdering her husband.

William Makepeace Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his Satire, satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel ''Vanity Fair (novel), Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portra ...

wrote: This famous set of pictures contains the most important and highly wrought of the Hogarth comedies. The care and method with which the moral grounds of these pictures are laid is as remarkable as the wit and skill of the observing and dexterous artist. He has to describe the negotiations for a marriage pending between the daughter of a rich citizen Alderman and young Lord Viscount Squanderfield, the dissipated son of a gouty old Earl ... The dismal end is known. My lord draws upon the counsellor, who kills him, and is apprehended while endeavouring to escape. My lady goes back perforce to the Alderman of the City, and faints upon reading Counsellor Silvertongue's dying speech at Tyburn (place of execution in old London), where the counsellor has been 'executed for sending his lordship out of the world. Moral: don't listen to evil silver-tongued counsellors; don't marry a man for his rank, or a woman for her money; don't frequent foolish auctions and masquerade balls unknown to your husband; don't have wicked companions abroad and neglect your wife, otherwise you will be run through the body, and ruin will ensue, and disgrace, and Tyburn.

''Industry and Idleness''

In the twelve prints of ''Industry and Idleness

''Industry and Idleness'' is the title of a series of 12 plot-linked engravings created by William Hogarth in 1747, intending to illustrate to working children the possible rewards of hard work and diligent application and the sure disasters at ...

'' (1747), Hogarth shows the progression in the lives of two apprentices, one of whom is dedicated and hard working, while the other, who is idle, commits crime and is eventually executed. This shows the work ethic of Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

England, where those who worked hard were rewarded, such as the industrious apprentice who becomes Sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

(plate 8), Alderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members them ...

(plate 10), and finally the Lord Mayor of London in the last plate in the series. The idle apprentice, who begins "at play in the church yard" (plate 3), holes up "in a Garrett with a Common Prostitute" after turning highwayman (plate 7) and "executed at Tyburn" (plate 11). The idle apprentice is sent to the gallows

A gallows (or scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended (i.e., hung) or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sacks ...

by the industrious apprentice himself. For each plate, there is at least one passage from the Bible at the bottom, mostly from the Book of Proverbs

The Book of Proverbs ( he, מִשְלֵי, , "Proverbs (of Solomon)") is a book in the third section (called Ketuvim) of the Hebrew Bible and a book of the Christian Old Testament. When translated into Greek and Latin, the title took on differ ...

, such as for the first plate:

:"Industry and Idleness, shown here, 'Proverbs Ch:10 Ver:4 The hand of the diligent maketh rich.'"

''Beer Street'' and ''Gin Lane''

Later prints of significance include his pictorial warning of the consequences of alcoholism in ''Beer Street'' and ''Gin Lane'' (1751). Hogarth engraved ''Beer Street'' to show a happy city drinking the 'good' beverage, English beer, in contrast to ''Gin Lane'', in which the effects of drinking gin are shown – as a more potent liquor, gin caused more problems for society. There had been a sharp increase in the popularity of gin at this time, which was called the ' Gin Craze.' It started in the early 18th century, after a series of legislative actions in the late 17th century impacted the importation and manufacturing of alcohol in London. Among these, were the

Later prints of significance include his pictorial warning of the consequences of alcoholism in ''Beer Street'' and ''Gin Lane'' (1751). Hogarth engraved ''Beer Street'' to show a happy city drinking the 'good' beverage, English beer, in contrast to ''Gin Lane'', in which the effects of drinking gin are shown – as a more potent liquor, gin caused more problems for society. There had been a sharp increase in the popularity of gin at this time, which was called the ' Gin Craze.' It started in the early 18th century, after a series of legislative actions in the late 17th century impacted the importation and manufacturing of alcohol in London. Among these, were the Prohibition of 1678

The Prohibition of 1678 (29 & 30 Cha. 2 c. 1) was an Act of the Parliament of England. Its full title was "An Act for raising Money by a Poll and otherwise, to enable His Majesty to enter into an actual War against the French King, and for prohi ...

, which barred popular French brandy imports, and the forced disbandment, in 1690, of the London Guild of Distillers

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major se ...

, whose members had previously been the only legal manufacturers of alcohol, leading to an increase in the production and then consumption of domestic gin.

In ''Beer Street'', people are shown as healthy, happy and prosperous, while in ''Gin Lane'', they are scrawny, lazy and careless. The woman at the front of ''Gin Lane'', who lets her baby fall to its death, echoes the tale of Judith Dufour, who strangled her baby so she could sell its clothes for gin money. The prints were published in support of the Gin Act 1751.

Hogarth's friend, the magistrate Henry Fielding, may have enlisted Hogarth to help with propaganda for the Gin Act; ''Beer Street'' and ''Gin Lane'' were issued shortly after his work ''An Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers, and Related Writings'', and addressed the same issues.

''The Four Stages of Cruelty''

Other prints were his outcry against inhumanity in '' The Four Stages of Cruelty'' (published 21 February 1751), in which Hogarth depicts the cruel treatment of animals which he saw around him and suggests what will happen to people who carry on in this manner. In the first print, there are scenes of boys torturing dogs, cats and other animals. It centers around a poorly dressed boy committing a violent act of torture upon a dog, while being pleaded with to stop, and offered food, by another well-dressed boy. A boy behind them has graffitied a hanged stickman figure upon a wall, with the name "Tom Nero" underneath, and is pointing to this dog torturer. The second shows Tom Nero has grown up to become a Hackney coach driver. His coach has overturned with a heavy load and his horse is lying on the ground, having broken its leg. He is beating it with the handle of his whip; its eye severely wounded. Other people around him are seen abusing their work animals and livestock, and a child is being run over by the wheel of adray

Dray may refer to:

* Cart, also called dray in Australia and New Zealand

* Dray horse, a horse that pulls a dray, also called a draft horse

* Dray (name)

* Dray Prescot series, science fiction novels by Kenneth Bulmer under the pseudonym Alan Burt ...

, as the drayman dozes off on the job.

In the third print, Tom is shown to be a murderer, surrounded by a mob of accusers. The woman he has apparently killed is lying on the ground, brutally slain, with a trunk and sack of stolen goods near by. One of the accusers holds a letter from the woman to Tom, speaking of how wronging her mistress upsets her conscience, but that she is resolved to do as he would have her, closing with: "I remain yours till death."

The fourth, titled ''The Reward of Cruelty'', shows Tom's withering corpse being publicly dissected by scientists after his execution by hanging; a noose still around his neck. The dissection reflects the Murder Act 1751, which allowed for the public dissection of criminals who had been hanged for murder.

Portraits

Hogarth was also popular portrait painter. In 1745, he painted actor David Garrick as Richard III, for which he was paid £200, "which was more", he wrote, "than any English artist ever received for a single portrait." In 1746, a sketch of Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat, afterwards beheaded on Tower Hill, had an exceptional success.

Hogarth was also popular portrait painter. In 1745, he painted actor David Garrick as Richard III, for which he was paid £200, "which was more", he wrote, "than any English artist ever received for a single portrait." In 1746, a sketch of Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat, afterwards beheaded on Tower Hill, had an exceptional success.

In 1740, he created a truthful, vivid full-length portrait of his friend, the philanthropic Captain Coram, for the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, now in the Foundling Museum. This portrait, and his unfinished oil sketch of a young fishwoman, entitled '' The Shrimp Girl'' ( National Gallery, London), may be called masterpieces of

In 1740, he created a truthful, vivid full-length portrait of his friend, the philanthropic Captain Coram, for the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, now in the Foundling Museum. This portrait, and his unfinished oil sketch of a young fishwoman, entitled '' The Shrimp Girl'' ( National Gallery, London), may be called masterpieces of British painting

The Art of the United Kingdom refers to all forms of visual art in or associated with the United Kingdom since the formation of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707 and encompasses English art, Scottish art, Welsh art and Irish art, and forms ...

. There are also portraits of his wife, his two sisters, and of many other people; among them Bishop Hoadly Hoadly is a surname, derived from the village of West Hoathly in Sussex. Notable people with the surname include:

*Benjamin Hoadly (1676–1761), English clergyman

* Benjamin Hoadly (physician) (1706–1757), English physician and dramatist

*Charl ...

and Bishop Herring.

Historical subjects

For a long period, during the mid-18th century, Hogarth tried to achieve the status of a history painter, but did not earn much respect in this field. The painter, and later founder of the Royal Academy of Arts, Joshua Reynolds, was highly critical of Hogarth's style and work. According to art historian David Bindman, in Dr Johnson's serial of essays for London's ''Universal Chronicle'', '' The Idler'', the three essays written by Reynolds for the months of September through November 1759 are directed at Hogarth. In them, Reynolds argues that this "connoisseur" has a "servile attention to minute exactness" and questions their idea of the imitation of nature as "the obvious sense, that objects are represented naturally when they have such relief that they seem real." Reynolds rejected "this kind of imitation", favouring the "grand style of painting" which avoids "minute attention" to the visible world. In Reynolds' ''Discourse XIV'', he grants Hogarth has "extraordinary talents", but reproaches him for "very imprudently, or rather presumptuously, attempt ngthe great historical style." Writer, art historian and politician, Horace Walpole, was also critical of Hogarth as a history painter, but did find value in his satirical prints.Biblical scenes

Hogarth's history pictures include ''The Pool of Bethesda'' and ''The Good Samaritan'', executed in 1736–1737 for St Bartholomew's Hospital; ''Moses brought before Pharaoh's Daughter'', painted for the Foundling Hospital (1747, formerly at the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, now in the Foundling Museum); ''Paul before Felix'' (1748) at Lincoln's Inn; and his altarpiece forSt. Mary Redcliffe

St Mary Redcliffe is an Anglican parish church located in the Redcliffe district of Bristol, England. The church is a short walk from Bristol Temple Meads station. The church building was constructed from the 12th to the 15th centuries, and it ...

, Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

(1755–56).

''The Gate of Calais''

'' The Gate of Calais'' (1748; now in Tate Britain) was produced soon after his return from a visit to France. Horace Walpole wrote that Hogarth had run a great risk to go there since the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle:he went to France, and was so imprudent as to be taking a sketch of the drawbridge atBack home, he immediately executed a painting of the subject in which he unkindly represented his enemies, the Frenchmen, as cringing, emaciated and superstitious people, while an enormous sirloin of beef arrives, destined for the English inn as a symbol of British prosperity and superiority. He claimed to have painted himself into the picture in the left corner sketching the gate, with a "soldier's hand upon my shoulder", running him in.Calais Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. The p .... He was seized and carried to the governor, where he was forced to prove his vocation by producing several caricatures of the French; particularly a scene of the shore, with an immense piece of beef landing for the ''Lion d'argent'', the English inn at Calais, and several hungry friars following it. They were much diverted with his drawings, and dismissed him.

Other later works

Notable Hogarth engravings in the 1740s include ''The Enraged Musician

''The Enraged Musician'' is a 1741 etching and engraving by English artist William Hogarth which depicts a comic scene of a violinist driven to distraction by the cacophony outside his window. It was issued as companion piece to the third state ...

'' (1741), the six prints of '' Marriage à-la-mode'' (1745; executed by French artists under Hogarth's inspection), and '' The Stage Coach or The Country Inn Yard'' (1747).

In 1745, Hogarth painted a self-portrait with his pug dog, Trump (now also in Tate Britain), which shows him as a learned artist supported by volumes of Shakespeare, Milton and Swift. In 1749, he represented the somewhat disorderly English troops on their ''March of the Guards to Finchley

''The March of the Guards to Finchley'', also known as ''The March to Finchley'' or ''The March of the Guards'', is a 1750 oil-on-canvas painting by English artist William Hogarth, owned by and on display at the Foundling Museum. Hogarth was well ...

'' (formerly located in Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, now Foundling Museum).

Others works included his ingenious ''Satire on False Perspective

''Satire on False Perspective'' is the title of an engraving produced by William Hogarth in 1754 for his friend Joshua Kirby's pamphlet on linear perspective.

The intent of the work is clearly given by its caption:

Summary

The work shows a sc ...

'' (1754); his satire on canvassing in his ''Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

'' series (1755–1758; now in Sir John Soane's Museum); his ridicule of the English passion for cockfighting in ''The Cockpit'' (1759); his attack on Methodism in ''Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism

''Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism'' is a satirical print by the English artist William Hogarth. It ridicules secular and religious credulity, and lampoons the exaggerated religious "enthusiasm" (excessive emotion, not keenness) of the Met ...

'' (1762); his political anti-war satire in ''The Times'', plate I (1762); and his pessimistic view of all things in '' Tailpiece, or The Bathos'' (1764).

In 1757, Hogarth was appointed Serjeant Painter

The Serjeant Painter was an honourable and lucrative position as court painter with the English monarch. It carried with it the prerogative of painting and gilding all of the King's residences, coaches, banners, etc. and it grossed over £1,000 ...

to the King.

Writing

Hogarth wrote and published his ideas of artistic design in his book '' The Analysis of Beauty'' (1753). In it, he professes to define the principles of beauty and grace which he, a real child of

Hogarth wrote and published his ideas of artistic design in his book '' The Analysis of Beauty'' (1753). In it, he professes to define the principles of beauty and grace which he, a real child of Rococo

Rococo (, also ), less commonly Roccoco or Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and theatrical style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, ...

, saw realized in serpentine lines (the Line of Beauty). By some of Hogarth's adherents, the book was praised as a fine deliverance upon aesthetics; by his enemies and rivals, its obscurities and minor errors were made the subject of endless ridicule and caricature. For instance, Paul Sandby produced several caricatures against Hogarth's treatise. Hogarth wrote also a manuscript called ''Apology for Painters'' (c.1761) and unpublished "autobiographical notes".

Painter and engraver of modern moral subjects

Hogarth lived in an age when artwork became increasingly commercialized, being viewed in shop windows, taverns, and public buildings, and sold in printshops. Old hierarchies broke down, and new forms began to flourish: the ballad opera, the bourgeois tragedy, and especially, a new form of fiction called thenovel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

with which authors such as Henry Fielding had great success. Therefore, by that time, Hogarth hit on a new idea: "painting and engraving modern moral subjects ... to treat my subjects as a dramatic writer; my picture was my stage", as he himself remarked in his manuscript notes.

He drew from the highly moralizing Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

tradition of Dutch genre painting, and the very vigorous satirical traditions of the English broadsheet and other types of popular print. In England the fine arts had little comedy in them before Hogarth. His prints were expensive, and remained so until early 19th-century reprints brought them to a wider audience.

Parodic borrowings from Old Masters

When analysing the work of the artist as a whole, Ronald Paulson says, "In '' A Harlot's Progress'', every single plate but one is based on Dürer's images of the story of the Virgin and the story of the Passion." In other works, he parodiesLeonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially re ...

's Last Supper. According to Paulson, Hogarth is subverting the religious establishment and the orthodox belief in an immanent God who intervenes in the lives of people and produces miracles. Indeed, Hogarth was a Deist, a believer in a God who created the universe but takes no direct hand in the lives of his creations. Thus, as a "comic history painter", he often poked fun at the old-fashioned, "beaten" subjects of religious art in his paintings and prints. Hogarth also rejected Lord Shaftesbury's then-current ideal of the classical Greek male in favour of the living, breathing female. He said, "Who but a bigot, even to the antiques, will say that he has not seen faces and necks, hands and arms in living women, that even the Grecian Venus doth but coarsely imitate."

Personal life

On 23 March 1729, Hogarth eloped with Jane Thornhill at Paddington Church, against the wishes of her father, the artist

On 23 March 1729, Hogarth eloped with Jane Thornhill at Paddington Church, against the wishes of her father, the artist Sir James Thornhill

Sir James Thornhill (25 July 1675 or 1676 – 4 May 1734) was an English painter of historical subjects working in the Italian baroque tradition. He was responsible for some large-scale schemes of murals, including the "Painted Hall" at the R ...

.

Sir James saw the match as unequal, as Hogarth was a rather obscure artist at the time. However, when Hogarth started on his series of moral prints, ''A Harlot's Progress'', some of the initial paintings were placed either in Sir James' drawing room or dining room, through the conspiring of Jane and her mother, in the hopes of reconciling him with the couple. When he saw them, he inquired as to the artist's name and, upon hearing it, replied: "Very well; the man who can produce such representations as these, can also maintain a wife without a portion." However, he soon after relented, becoming more generous to, and living in harmony with the couple until his death.

Hogarth was initiated as a Freemason before 1728 in the Lodge at the Hand and Apple Tree Tavern, Little Queen Street, and later belonged to the Carrier Stone Lodge and the Grand Stewards' Lodge; the latter still possesses the 'Hogarth Jewel' which Hogarth designed for the Lodge's Master to wear. Today the original is in storage and a replica is worn by the Master of the Lodge. Freemasonry was a theme in some of Hogarth's work, most notably 'Night', the fourth in the quartet of paintings (later released as engravings) collectively entitled the '' Four Times of the Day''.

Sir James saw the match as unequal, as Hogarth was a rather obscure artist at the time. However, when Hogarth started on his series of moral prints, ''A Harlot's Progress'', some of the initial paintings were placed either in Sir James' drawing room or dining room, through the conspiring of Jane and her mother, in the hopes of reconciling him with the couple. When he saw them, he inquired as to the artist's name and, upon hearing it, replied: "Very well; the man who can produce such representations as these, can also maintain a wife without a portion." However, he soon after relented, becoming more generous to, and living in harmony with the couple until his death.

Hogarth was initiated as a Freemason before 1728 in the Lodge at the Hand and Apple Tree Tavern, Little Queen Street, and later belonged to the Carrier Stone Lodge and the Grand Stewards' Lodge; the latter still possesses the 'Hogarth Jewel' which Hogarth designed for the Lodge's Master to wear. Today the original is in storage and a replica is worn by the Master of the Lodge. Freemasonry was a theme in some of Hogarth's work, most notably 'Night', the fourth in the quartet of paintings (later released as engravings) collectively entitled the '' Four Times of the Day''.

His main home was in Leicester Square (then known as Leicester Fields), but he bought a country retreat in Chiswick in 1749, the house now known as Hogarth's House and preserved as a museum, and spent time there for the rest of his life.

The Hogarths had no children, although they fostered foundling children. He was a founding Governor of the Foundling Hospital.

Among his friends and acquaintances were many English artists and satirists of the period, such as Francis Hayman, Henry Fielding, and Laurence Sterne.

His main home was in Leicester Square (then known as Leicester Fields), but he bought a country retreat in Chiswick in 1749, the house now known as Hogarth's House and preserved as a museum, and spent time there for the rest of his life.

The Hogarths had no children, although they fostered foundling children. He was a founding Governor of the Foundling Hospital.

Among his friends and acquaintances were many English artists and satirists of the period, such as Francis Hayman, Henry Fielding, and Laurence Sterne.

Death

On 25 October 1764, Hogarth was conveyed from his villa in Chiswick to his home in Leicester Fields, in weak condition. He had been in a weakened state for a while by this time, but was said to be in a cheerful mood and was even still working—with some help; doing more retouches on '' The Bench'' on this same day. On 26 October, he received a letter from

On 25 October 1764, Hogarth was conveyed from his villa in Chiswick to his home in Leicester Fields, in weak condition. He had been in a weakened state for a while by this time, but was said to be in a cheerful mood and was even still working—with some help; doing more retouches on '' The Bench'' on this same day. On 26 October, he received a letter from Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a m ...

and wrote up a rough draught in reply. Before going to bed that evening, he'd boasted about eating a pound of beefsteaks for dinner and reportedly looked more robust than he had in a while at this time. However, when he went to bed, he suddenly began vomiting; something that caused him to ring his bell so forcefully that it broke. Hogarth passed away around two hours later, in the arms of his servant, Mrs Mary Lewis. John Nichols claimed that he died of an aneurysm, which he said took place in the "chest." Horace Walpole claimed that he died of "a dropsy of his breast."

Mrs Lewis, who stayed on with Jane Hogarth in Leicester Fields, was the only non-familial person acknowledged financially in Hogarth's will and was left £100 (approximately £18,651.61 in 2020) for her "faithful services."

Hogarth was buried at

Hogarth was buried at St. Nicholas Church, Chiswick

St Nicholas Church, Chiswick is a Grade II* listed Anglican church in Church Street, Chiswick, London, near the River Thames. Old Chiswick developed as a village around the church from c. 1181. The tower was built at some time between 1416 and ...

, now in the west of London. His friend, actor David Garrick, composed the following inscription for his tombstone:

Influence and reputation

Hogarth's works were a direct influence onJohn Collier John Collier may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*John Collier (caricaturist) (1708–1786), English caricaturist and satirical poet

*John Payne Collier (1789–1883), English Shakespearian critic and forger

*John Collier (painter) (1850–1934), ...

, who was known as the "Lancashire Hogarth". The spread of Hogarth's prints throughout Europe, together with the depiction of popular scenes from his prints in faked Hogarth prints, influenced Continental book illustration through the 18th and early 19th centuries, especially in Germany and France. He also influenced many caricaturists of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Hogarth's influence lives on today as artists continue to draw inspiration from his work.

Hogarth's paintings and prints have provided the subject matter for several other works. For example, Gavin Gordon's 1935 ballet '' The Rake's Progress'', to choreography by Ninette de Valois, was based directly on Hogarth's series of paintings of that title. Igor Stravinsky's 1951 opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a libre ...

'' The Rake's Progress'', with libretto by W. H. Auden, was less literally inspired by the same series. Hogarth's engravings also inspired the BBC radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

play ''The Midnight House'' by Jonathan Hall, based on the M. R. James ghost story " The Mezzotint" and first broadcast on BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of Talk radio, spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history fro ...

in 2006.

Russell Banks' short story "Indisposed" is a fictional account of Hogarth's infidelity as told from the viewpoint of his wife, Jane. Hogarth was the lead character in Nick Dear's play '' The Art of Success'', whilst he is played by Toby Jones in the 2006 television film '' A Harlot's Progress''.

Hogarth's House in Chiswick, west London, is now a museum; the major road junction next to it is named the Hogarth Roundabout. In 2014 both Hogarth's House and the Foundling Museum held special exhibitions to mark the 250th anniversary of his death.

In 2019, Sir John Soane's Museum, which owns both ''The Rake's Progress'' and '' The Humours of an Election'', held an exhibition which assembled all Hogarth's series of paintings, and his series of engravings, in one place for the first time.

Stanley Kubrick based the cinematography of his 1975 period drama film, '' Barry Lyndon'', on several Hogarth paintings.

In Roger Michell's 2003 film '' The Mother'', starring Anne Reid and Daniel Craig, the protagonists visit Hogarth's tomb during their first outing together. They read aloud the poem inscribed there and their shared admiration of Hogarth helps to affirm their connection with one another.

Selected works

;''Paintings''March of the Guards to Finchley

''The March of the Guards to Finchley'', also known as ''The March to Finchley'' or ''The March of the Guards'', is a 1750 oil-on-canvas painting by English artist William Hogarth, owned by and on display at the Foundling Museum. Hogarth was well ...

'' (1750), a satirical depiction of troops mustered to defend London from the 1745 Jacobite rebellion

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took pl ...

File:William Hogarth by William Hogarth.jpg, '' Hogarth Painting the Comic Muse''. A self-portrait depicting Hogarth painting Thalia, the muse of comedy and pastoral poetry, 1757–1758

File:William Hogarth 004.jpg, '' The Bench'', 1758

File:Hogarths-Servants.jpg, '' Hogarth's Servants'', mid-1750s.

File:William Hogarth 028.jpg, '' An Election Entertainment'' featuring the anti-Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years di ...

banner " Give us our Eleven Days", 1755.

File:William Hogarth 032.jpg, William Hogarth's Election series, '' Humours of an Election'', plate 2

File:William Hogarth - The Sleeping Congregation - 58.10 - Minneapolis Institute of Arts.jpg, ''The Sleeping Congregation'', 1728, Minneapolis Institute of Art

A Just View of the British Stage

''A Just View of the British Stage'' or ''Three Heads are Better than One'' is an unsigned 1724 engraving attributed to the English artist William Hogarth. It is a satirical view of the management of British plays and mocks the subjects as dege ...

''

File:William Hogarth - Industry and Idleness, Plate 11; The Idle 'Prentice Executed at Tyburn.png, ''Industry and Idleness

''Industry and Idleness'' is the title of a series of 12 plot-linked engravings created by William Hogarth in 1747, intending to illustrate to working children the possible rewards of hard work and diligent application and the sure disasters at ...

'', plate 11, ''The Idle 'Prentice executed at Tyburn''

Image:William Hogarth - Simon, Lord Lovat.png, William Hogarth's engraving of the Jacobite

Jacobite means follower of Jacob or James. Jacobite may refer to:

Religion

* Jacobites, followers of Saint Jacob Baradaeus (died 578). Churches in the Jacobite tradition and sometimes called Jacobite include:

** Syriac Orthodox Church, sometimes ...

Lord Lovat prior to his execution

File:John Wilkes Esq by William Hogarth.JPG, Hogarth's satirical engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design onto a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an i ...

of the radical politician John Wilkes.

File:Hogarth Before.jpg, Engraving, ''Before'' the 1736 print, based on the earlier "oyl"

File:Hogarth After.jpg, Engraving, ''After''

See also

* English art *List of works by William Hogarth

This is a list of works by William Hogarth by publication date (if known).

As a printmaker Hogarth often employed other engravers to produce his work and frequently revised his works between one print run and the next, so it is often difficult t ...

* Ronald Paulson, the world's leading expert on Hogarth

* Judy Egerton, Hogarth curator, cataloguer, and commentator

Notes

References

* William Hogarth,John Bowyer Nichols

John Bowyer Nichols (1779–1863) was an English printer and antiquary.

Life

The eldest son of John Nichols, by his second wife, Martha Green (1756–1788), he was born at Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, London, on 15 July 1779. He spent his e ...

, ed. ''Anecdotes of William Hogarth, Written by Himself'' (J. B. Nichols and Son, 25 Parliament Street, London, 1833)

* Peter Quennell, ''Hogarth's Progress'' (London, New York, Ayer Co., 1955, )

* Quennell, Peter. "Hogarth's Election Series." ''History Today'' (Apr 1953) 3#4 pp 221–232

* Frederick Antal, ''Hogarth and His Place in European Art'' (London 1962).

* Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, ''Ausführliche Erklärung der Hogarthischen Kupferstiche'' (Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag, 1972, )

* Sean Shesgreen, ''Hogarth 101 Prints'' (New York: Dover 1973).

* David Bindman, ''Hogarth'' (London 1981).

* Sean Shesgreen, ''Hogarth and the Times-of-the-Day Tradition'' (Ithaca, New York: Cornell UP, 1983).

* Ronald Paulson, ''Hogarth's Graphic Works'' (3rd edn, London 1989).

* Ronald Paulson, ''Hogarth'', 3 vols. (New Brunswick 1991–93).

* Elizabeth Einberg, ''Hogarth the Painter'' (London: Tate Gallery, 1997).

* Jenny Uglow, ''Hogarth: A Life and a World'' (London 1997).

* Frédéric Ogée and Hans-Peter Wagner, eds., ''William Hogarth: Theater and the Theater of Life'' (Los Angeles, 1997).

* Hans-Peter Wagner, ''William Hogarth: Das graphische Werk'' (Saarbrücken, 1998; revised edition, Trier 2013).

* David Bindman, Frédéric Ogée and Peter Wagner, eds. ''Hogarth: Representing Nature's Machines'' (Manchester, 2001)

* Bernadette Fort, and Angela Rosenthal, eds., ''The Other Hogarth: Aesthetics of Difference'' (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001)

* Christine Riding and Mark Hallet, "Hogarth" ( Tate Publishing, London, 2006).

* Robin Simon''Hogarth, France and British Art: The rise of the arts in eighteenth-century Britain''

(London, 2007) * Ilias Chrissochoidis,

Handel, Hogarth, Goupy: Artistic intersections in Handelian biography

, ''Early Music'' 37/4 (November 2009), 577–596. * Bernd W. Krysmanski, ''Hogarth's Hidden Parts: Satiric Allusion, Erotic Wit, Blasphemous Bawdiness and Dark Humour in Eighteenth-Century English Art'' (Hildesheim, Zurich, New York: Olms-Verlag, 2010 ) * Johann Joachim Eschenburg, ''Über William Hogarth und seine Erklärer'', ed. Till Kinzel (Hanover: Wehrhahn, 2013 ) * Cynthia Ellen Roman, ed., ''Hogarth's Legacy'' (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016) * Elizabeth Einberg, ''William Hogarth: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings'' (New Haven and London, Yale University Press for Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2016)

External links

* *''The Works of William Hogarth'', 1822 Heath edition (engravings, with commentaries by John Nichols)

William Hogarth's biography, style, artworks and influences

William Hogarth at The National Gallery

The Site for Research on William Hogarth

(annotated online bibliography)

Print series in detail

Hogarth exhibition at Tate Britain, London

(7 February – 29 April 2007)

William Hogarth at Wikigallery

* *

Location of Hogarth's grave on Google Maps

''The Analysis of Beauty'', 1753

(abridged 1909 edition)

'Hogarth's London'

lecture by Robin Simon at Gresham College, 8 October 2007 (available for download as MP3, MP4 or text files)

Hogarth's London video

hosted at Tate Britain's website by Martin Rowson

William Hogarth's Works

hosted at The Victorian Web {{DEFAULTSORT:Hogarth, William 1697 births 1764 deaths 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers 18th-century English male artists Painters from London English caricaturists English cartoonists English engravers English illustrators English satirists English printmakers 18th-century English painters English male painters Court painters Artist authors Political artists Social critics Freemasons of the Premier Grand Lodge of England