William Friese-Greene on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Friese-Greene (born William Edward Green, 7 September 1855 – 5 May 1921) was a prolific English inventor and professional photographer. He was known as a pioneer in the field of motion pictures, having devised a series of cameras in 1888–1891 and shot moving pictures with them in London. He went on to patent an early two-colour filming process in 1905. Wealth came with inventions in printing, including photo-typesetting and a method of printing without ink, and from a chain of photographic studios. However, he spent it all on inventing, went bankrupt three times, was jailed once, and died in poverty.

William Friese-Greene (born William Edward Green, 7 September 1855 – 5 May 1921) was a prolific English inventor and professional photographer. He was known as a pioneer in the field of motion pictures, having devised a series of cameras in 1888–1891 and shot moving pictures with them in London. He went on to patent an early two-colour filming process in 1905. Wealth came with inventions in printing, including photo-typesetting and a method of printing without ink, and from a chain of photographic studios. However, he spent it all on inventing, went bankrupt three times, was jailed once, and died in poverty.

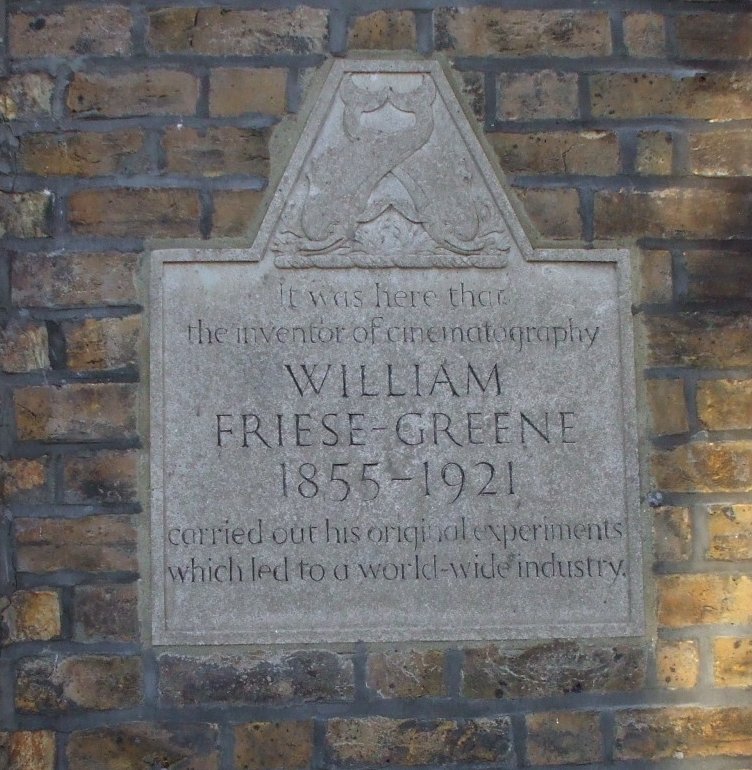

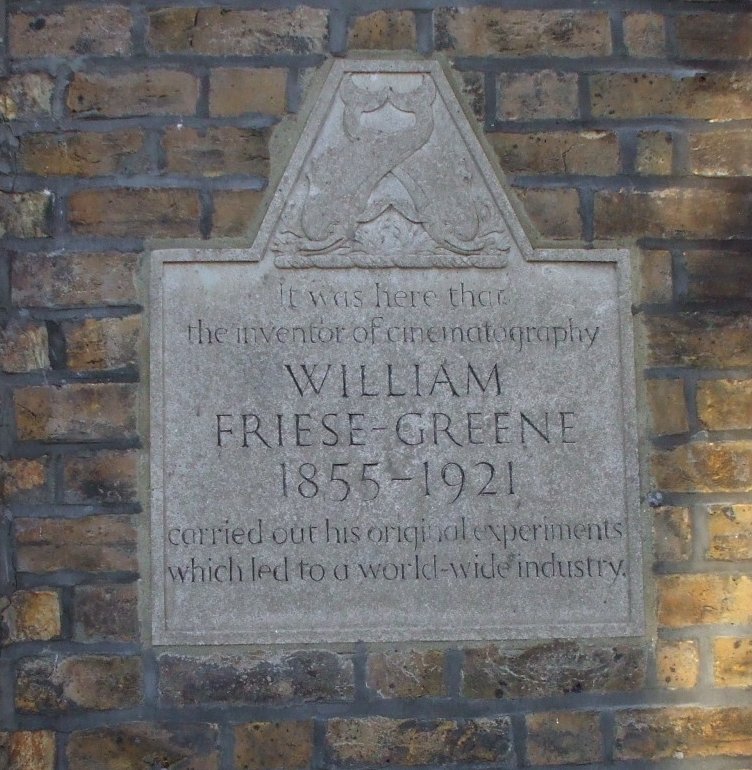

(reprinted by Arno Press Cinema Program (1972) acsimile, Hardcover) which was then turned into an even more misleading film, ''The Magic Box''." Nonetheless, Martin Scorsese has many times cited it as one of his favourite films, and one that inspired him. Despite a campaign by Bristol photographer Reece Winstone for the retention of Friese-Greene's birthplace for use as a Museum of Cinematography, among other purposes, it was demolished by Bristol Corporation in 1958 to provide parking space for six cars. Premises in Brighton's Middle Street where Friese-Greene had a workshop for several years are often wrongly described as his home. They bear a plaque in a 1924 design by

Premises in Brighton's Middle Street where Friese-Greene had a workshop for several years are often wrongly described as his home. They bear a plaque in a 1924 design by

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

''King's Road 1891''

Early Friese-Greene test film, shot in London on perforated celluloid

William Friese-Greene & Me

Blog covering latest research on Friese-Greene

Friese-Greene on Timeline of Historical Film Colors

*. {{DEFAULTSORT:Friese-Greene, William 1855 births 1921 deaths Photographers from Bristol People from Maida Vale Burials at Highgate Cemetery People educated at Queen Elizabeth's Hospital, Bristol Cinema pioneers British inventors

William Friese-Greene (born William Edward Green, 7 September 1855 – 5 May 1921) was a prolific English inventor and professional photographer. He was known as a pioneer in the field of motion pictures, having devised a series of cameras in 1888–1891 and shot moving pictures with them in London. He went on to patent an early two-colour filming process in 1905. Wealth came with inventions in printing, including photo-typesetting and a method of printing without ink, and from a chain of photographic studios. However, he spent it all on inventing, went bankrupt three times, was jailed once, and died in poverty.

William Friese-Greene (born William Edward Green, 7 September 1855 – 5 May 1921) was a prolific English inventor and professional photographer. He was known as a pioneer in the field of motion pictures, having devised a series of cameras in 1888–1891 and shot moving pictures with them in London. He went on to patent an early two-colour filming process in 1905. Wealth came with inventions in printing, including photo-typesetting and a method of printing without ink, and from a chain of photographic studios. However, he spent it all on inventing, went bankrupt three times, was jailed once, and died in poverty.

Early life

William Edward Green was born on 7 September 1855, inBristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

. He studied at the Queen Elizabeth's Hospital

Queen Elizabeth's Hospital (also known as QEH) is an independent day school in Clifton, Bristol, England, founded in 1586. QEH is named after its original patron, Queen Elizabeth I. Known traditionally as "The City School", Queen Elizabeth's Hos ...

school. In 1871, he was apprenticed to the Bristol photographer Marcus Guttenberg, but later successfully went to court to be freed early from the indentures of his seven-year apprenticeship. He married the Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

*Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internati ...

, Helena Friese (born Victoria Mariana Helena Friese), on 24 March 1874 and, in a remarkable move for the era, decided to add her maiden name to his surname. In 1876, he set up his own studio in Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

and, by 1881, had expanded his business, having more studios in Bath, Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

and Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymout ...

.

Cinematic inventor

Experiments with magic lanterns

In Bath he came into contact with John Arthur Roebuck Rudge. Rudge was a scientific instrument maker who also worked with electricity andmagic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lens (optics), lenses, and a light source. ...

s to create popular entertainments. Rudge built what he called the Biophantic Lantern, which could display seven photographic slides in rapid succession, producing the illusion of movement. It showed a sequence in which Rudge (with the invisible help of Friese-Greene) apparently took off his head. Friese-Greene was fascinated by the machine and worked with Rudge on a variety of devices over the 1880s, various of which Rudge called the Biophantascope. Moving his base to London in 1885, Friese-Greene realised that glass plates would never be a practical medium for continuously capturing life as it happens. Hence he began experiments with the new Eastman paper roll film, made transparent with castor oil, before turning his attention to experimenting with celluloid

Celluloids are a class of materials produced by mixing nitrocellulose and camphor, often with added dyes and other agents. Once much more common for its use as photographic film before the advent of safer methods, celluloid's common contemporar ...

as a medium for motion picture cameras.

Movie cameras

In 1888, Friese-Greene had some form of moving picture camera constructed, the nature of which is not known. On 21 June 1889, Friese-Greene was issued patent no. 10131 for a motion-picture camera, in collaboration with a civil engineer, Mortimer Evans. It was apparently capable of taking up to ten photographs per second using paper and celluloid film. An illustrated report on the camera appeared in the British ''Photographic News'' on 28 February 1890. On 18 March, Friese-Greene sent details of it toThomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These invent ...

, whose laboratory had begun developing a motion picture system, with a peephole viewer, later christened the Kinetoscope

The Kinetoscope is an early motion picture exhibition device, designed for films to be viewed by one person at a time through a peephole viewer window. The Kinetoscope was not a movie projector, but it introduced the basic approach that woul ...

. The report was reprinted in ''Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many famous scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it. In print since 1845, it i ...

'' on 19 April. In 1890 he developed a camera with Frederick Varley to shoot stereoscopic

Stereoscopy (also called stereoscopics, or stereo imaging) is a technique for creating or enhancing the illusion of depth in an image by means of stereopsis for binocular vision. The word ''stereoscopy'' derives . Any stereoscopic image is ...

moving images. This ran at a slower frame rate, and although the 3D arrangement worked, there are no records of projection. Friese-Greene worked on a series of moving picture cameras into 1891, but although many individuals recount seeing his projected images privately, he never gave a successful public projection of moving pictures. Friese-Greene's experiments with motion pictures were to the detriment of his other business interests and in 1891 he was declared bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debto ...

. To cover his debts he had sold the rights to the 1889 moving picture camera patent for £500 to investors in the City of London. The renewal fee was never paid and the patent lapsed.

Colour film

Friese-Greene's later exploits were in the field of colour in motion pictures. From 1904 he lived in Brighton where there were a number of experimenters developing still and moving pictures in colour. Initially working withWilliam Norman Lascelles Davidson

Captain William Norman Lascelles Davidson (c.1871 – 31 January 1935) was an English soldier who was an early experimenter in color cinematography.

Davidson was born in Notting Hill, London''1911 England Census'' to Col. Alfred Augustus Davids ...

, Friese-Greene patented a two-colour moving picture system using prisms in 1905. He and Davidson gave public demonstrations of this in January and July 1906 and Friese-Greene held screenings at his photographic studio.

He also experimented with a system which produced the illusion of true colour by exposing each alternate frame of ordinary black-and-white film stock through two or three different coloured filters. Each alternate frame of the monochrome print was then stained red or green (and/or blue). Although the projection of prints did provide an impression of colour, it suffered from red and green fringing when the subject was in rapid motion, as did the more popular and famous system, Kinemacolor

Kinemacolor was the first successful colour motion picture process, used commercially from 1908 to 1914. It was invented by George Albert Smith in 1906. He was influenced by the work of William Norman Lascelles Davidson and, more directly, Ed ...

.

In 1911, Charles Urban filed a lawsuit against Harold Speer, who had purchased rights in Friese-Greene's 1905 patent and created a company 'Biocolour', claiming that this process infringed upon the Kinemacolor

Kinemacolor was the first successful colour motion picture process, used commercially from 1908 to 1914. It was invented by George Albert Smith in 1906. He was influenced by the work of William Norman Lascelles Davidson and, more directly, Ed ...

patent of George Albert Smith

George Albert Smith Sr. (April 4, 1870 – April 4, 1951) was an American religious leader who served as the eighth president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church).

Early life

Born in Salt Lake City, Utah Territo ...

, despite the fact that Friese-Greene had both patented and demonstrated his work before Smith. Urban was granted an injunction against Biocolour in 1912, but the Sussex-based, racing driver Selwyn Edge

Selwyn Francis Edge (1868–1940) was a British businessman, racing driver, cyclist and record-breaker. He is principally associated with selling and racing De Dion-Bouton, Gladiator; Clemént-Panhard, Napier and AC cars.

Personal life

Edge w ...

funded an appeal to the High Court. This overturned the original verdict on the grounds that Kinemacolor made claims for itself which it could not deliver. Urban fought back and pushed it up to the House of Lords, which in 1915 upheld the decision of the High Court. The decision benefited nobody. For Urban it was a case of hubris because now he could no longer exercise control over his own system, so it became worthless. For Friese-Greene, the arrival of the war and personal poverty meant there was nothing more to be done with colour for some years.

His son Claude Friese-Greene continued to develop the system with his father, after whose death in the early 1920s he called it "The Friese-Greene Natural Colour Process" and shot with it the documentary films " The Open Road", which offer a rare portrait of 1920s Britain in colour. These were featured in a BBC series '' The Lost World of Friese-Greene'' and then issued in a digitally restored form by the BFI on DVD in 2006.

Death

On 5 May 1921, Friese-Greene – then a largely forgotten figure – attended a stormy meeting of the cinema trade at the Connaught Rooms in London. The meeting had been called to discuss the current poor state of British film distribution and was chaired by Lord Beaverbrook. Disturbed by the tone of the proceedings, Friese-Greene got to his feet to speak. The chairman asked him to come forward onto the platform to be heard better, which he did, appealing for the two sides to come together. Shortly after returning to his seat, he collapsed. People went to his aid and took him outside, but he died almost immediately of heart failure. Given his dramatic death, surrounded by film industry representatives who had almost entirely forgotten about his role in motion pictures, there was a spasm of collective shock and guilt. A very grand funeral was staged for him, with the streets of London lined by the curious. A two-minute silence was observed in some cinemas, and a fund was raised to commission a memorial for his grave. He was buried in the eastern section of London'sHighgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in north London, England. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East Cemeteries. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for some of the people buried there as ...

, just south of the entrance and visible from the street through the railings. However, his memorial was not designed by Edwin Lutyens, as is often stated. It describes him as "The Inventor of Kinematography", a term Friese-Greene never used in talking about his achievements. Indeed, he often spoke generously about other workers in the field of capturing movement.

His second wife, Edith Jane, died a few months later of cancer and is buried with him, as are some of his children.

Family

After the death of his first wife, with whom he had one daughter, Friese-Greene married Edith Jane Harrison (1875–1921) and they had six sons, one dying in infancy. The eldest, Claude (1898–1943), and the youngest, Vincent (1910–1943), are buried with their parents. Vincent was killed in action during theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

His great-grandson is Tim Friese-Greene

Timothy Alan Friese-Greene is an English musician and producer. He worked with the band Talk Talk from 1983 to their breakup in 1991. He currently releases solo albums under the name "Heligoland". He is the grandson of filmmaker Claude Friese-Gr ...

.

Legacy

In 1951 a biopic was made, starringRobert Donat

Friedrich Robert Donat (18 March 1905 – 9 June 1958) was an English actor. He is best remembered for his roles in Alfred Hitchcock's '' The 39 Steps'' (1935) and '' Goodbye, Mr. Chips'' (1939), winning for the latter the Academy Award for ...

, as part of the Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

...

. The film, ''The Magic Box

''The Magic Box'' is a 1951 British Technicolor biographical drama film directed by John Boulting. The film stars Robert Donat as William Friese-Greene, with numerous cameo appearances by performers such as Peter Ustinov and Laurence Ol ...

,'' was not shown until the festival was nearly over and only went on full release after it had finished. Despite the all-star cast and much praise for Robert Donat's performance, it was a box office flop. Domankiewicz and Herbert wrote, "He was the subject of a romantic and unreliable biography, ''Friese-Greene, Close-Up of an Inventor'',Ray Allister (pseudonym for Muriel Forth) (1948) ''Friese-Greene, Close Up of An Inventor'', Marsland Publications, London(reprinted by Arno Press Cinema Program (1972) acsimile, Hardcover) which was then turned into an even more misleading film, ''The Magic Box''." Nonetheless, Martin Scorsese has many times cited it as one of his favourite films, and one that inspired him. Despite a campaign by Bristol photographer Reece Winstone for the retention of Friese-Greene's birthplace for use as a Museum of Cinematography, among other purposes, it was demolished by Bristol Corporation in 1958 to provide parking space for six cars.

Premises in Brighton's Middle Street where Friese-Greene had a workshop for several years are often wrongly described as his home. They bear a plaque in a 1924 design by

Premises in Brighton's Middle Street where Friese-Greene had a workshop for several years are often wrongly described as his home. They bear a plaque in a 1924 design by Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill, (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as ″the greatest artist-cra ...

commemorating Friese-Greene's achievements, wrongly stating that it is the place where he invented cinematography. The plaque was unveiled by Michael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave CBE (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English stage and film actor, director, manager and author. He received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in '' Mourning Becomes El ...

, who had appeared in ''The Magic Box

''The Magic Box'' is a 1951 British Technicolor biographical drama film directed by John Boulting. The film stars Robert Donat as William Friese-Greene, with numerous cameo appearances by performers such as Peter Ustinov and Laurence Ol ...

'', in September 1951. A modern office building a few yards away is named Friese-Greene House. Other plaques include the 1930s Odeon Cinema in Kings Road, Chelsea, London, with its iconic façade, which carries high upon it a large sculpted head-and-shoulders medallion of "William Friese-Greene" and his years of birth and death. There are busts of him at Pinewood Studios

Pinewood Studios is a British film and television studio located in the village of Iver Heath, England. It is approximately west of central London.

The studio has been the base for many productions over the years from large-scale films to ...

and Shepperton Studios

Shepperton Studios is a film studio located in Shepperton, Surrey, England, with a history dating back to 1931. It is now part of the Pinewood Studios Group. During its early existence, the studio was branded as Sound City (not to be confused ...

.

In 2006 the BBC ran a series of programmes called '' The Lost World of Friese-Greene'', presented by Dan Cruickshank about Claude Friese-Greene's road trip from Land's End to John o' Groats

Land's End to John o' Groats is the traversal of the whole length of the island of Great Britain between two List of extreme points of the United Kingdom#Extreme points within the UK, extremities, in the southwest and northeast. The tradition ...

, entitled ''The Open Road'', which he filmed from 1924 to 1926 using The Friese-Greene Natural Colour Process. Modern television production techniques meant they were able to remove the problems of flickering and colour fringing around moving objects, which Kinemacolor and this process had when projected. The result was a unique view of Britain in colour in the mid-1920s.

William Friese-Greene was more or less banished to obscurity by film historians from 1955 onwards, but new research is rehabilitating him, giving a better understanding of his achievements and influence on the technical development of cinema.Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

See also

*History of film technology

The history of film technology traces the development of techniques for the recording, construction and presentation of motion pictures. When the film medium came about in the 19th century, there already was a centuries old tradition of screening ...

References

External links

''King's Road 1891''

Early Friese-Greene test film, shot in London on perforated celluloid

William Friese-Greene & Me

Blog covering latest research on Friese-Greene

Friese-Greene on Timeline of Historical Film Colors

*. {{DEFAULTSORT:Friese-Greene, William 1855 births 1921 deaths Photographers from Bristol People from Maida Vale Burials at Highgate Cemetery People educated at Queen Elizabeth's Hospital, Bristol Cinema pioneers British inventors