William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, (16 October 1396 – 2 May 1450), nicknamed Jackanapes, was an English magnate, statesman, and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. He became a

William de la Pole was born in Cotton, Suffolk, the second son of Michael de la Pole, 2nd Earl of Suffolk by his wife Katherine de Stafford, daughter of

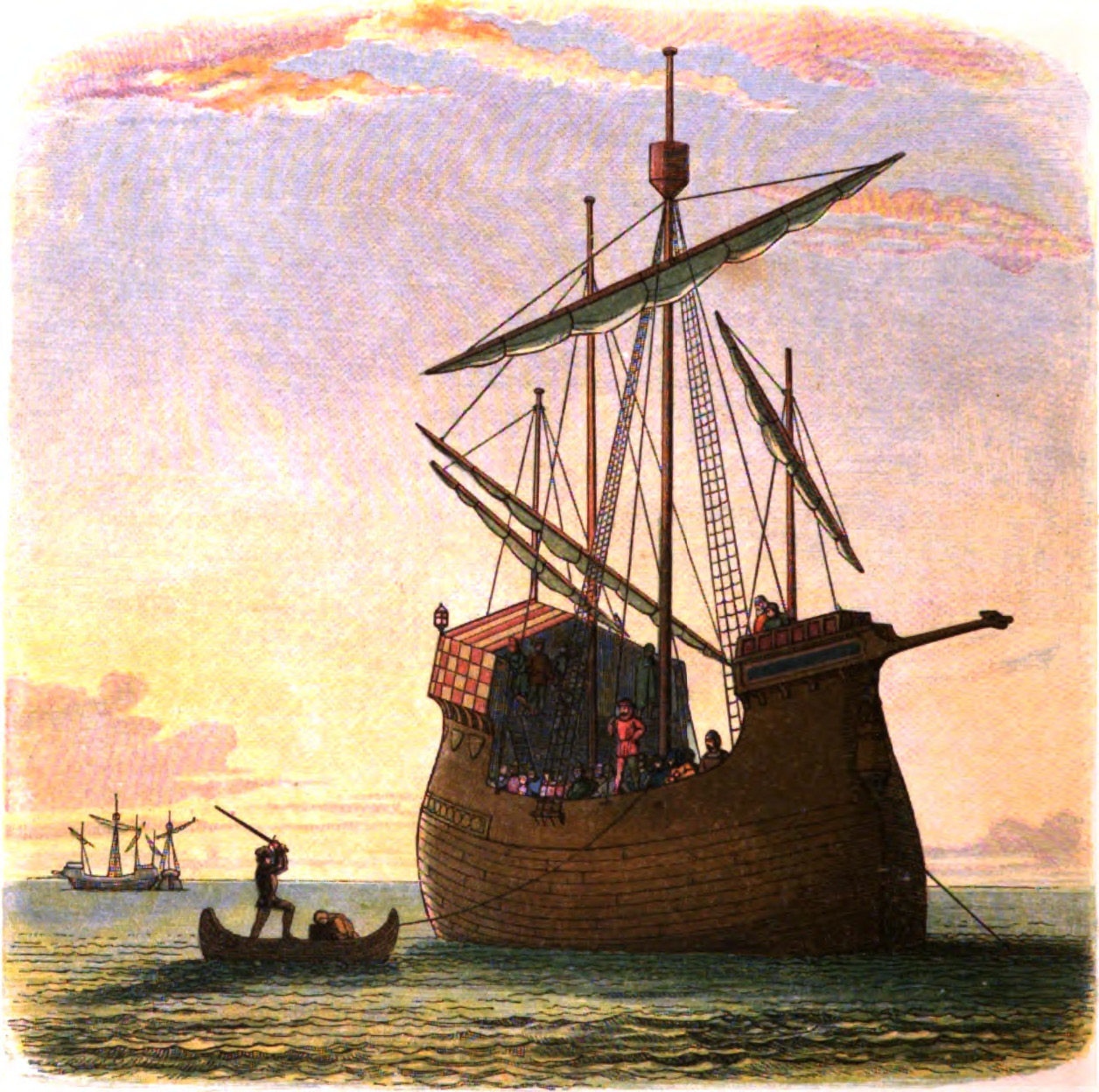

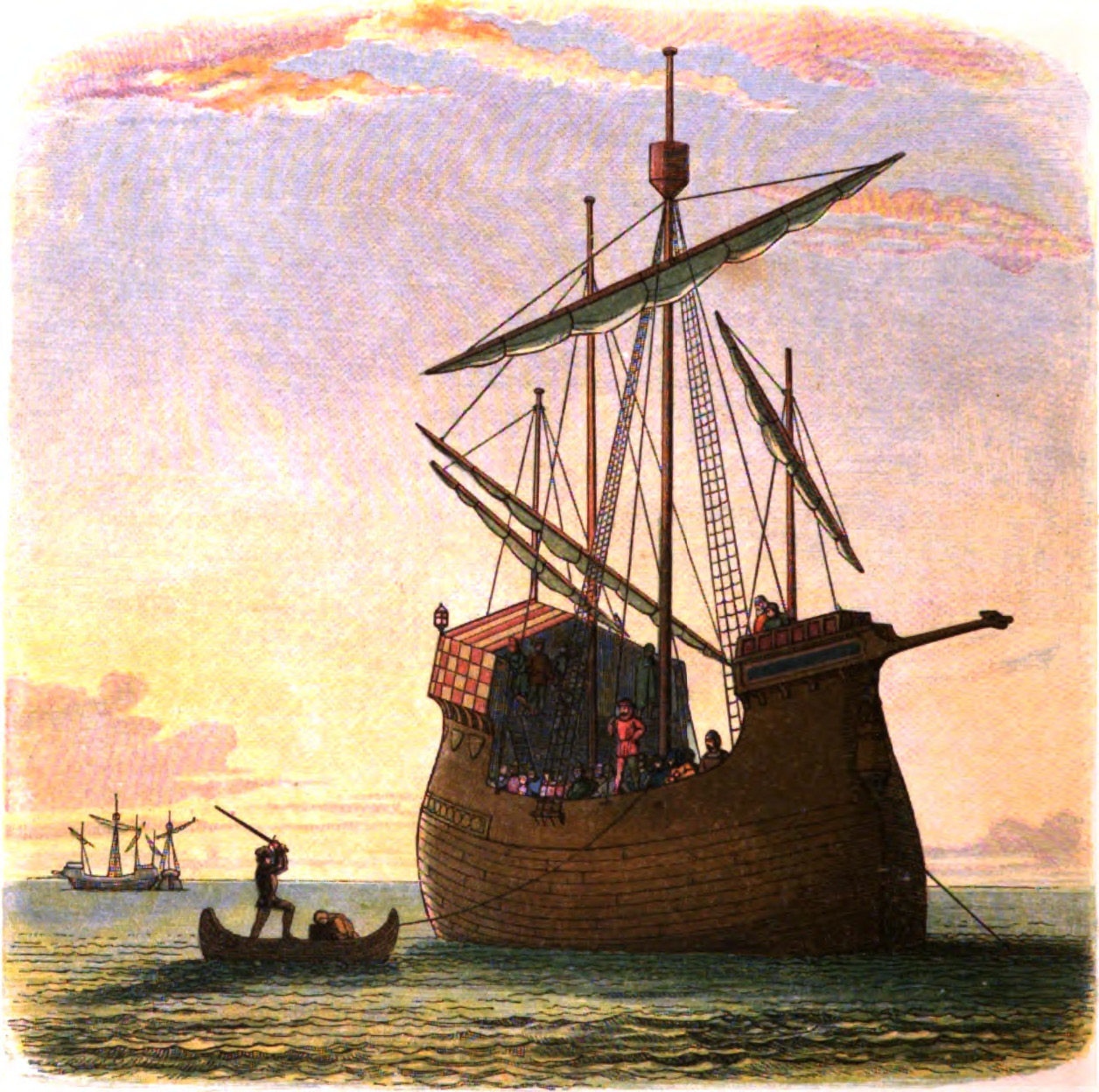

William de la Pole was born in Cotton, Suffolk, the second son of Michael de la Pole, 2nd Earl of Suffolk by his wife Katherine de Stafford, daughter of  The King intervened to protect his favourite, who was banished for five years, but on his journey to Calais his ship was intercepted by the ship ''Nicholas of the Tower''. Suffolk was captured, subjected to a mock trial, and executed by beheading. His body was later found on the sands near Dover, and was probably brought to a church in Suffolk, possibly Wingfield. He was interred in the Carthusian Priory in Hull by his widow Alice, as was his wish, and not in the church at Wingfield, as is often stated. The Priory, founded in 1377 by his grandfather the first Earl of Suffolk, was dissolved in 1539, and most of the original buildings did not survive the two Civil War sieges of Hull in 1642 and 1643.

The King intervened to protect his favourite, who was banished for five years, but on his journey to Calais his ship was intercepted by the ship ''Nicholas of the Tower''. Suffolk was captured, subjected to a mock trial, and executed by beheading. His body was later found on the sands near Dover, and was probably brought to a church in Suffolk, possibly Wingfield. He was interred in the Carthusian Priory in Hull by his widow Alice, as was his wish, and not in the church at Wingfield, as is often stated. The Priory, founded in 1377 by his grandfather the first Earl of Suffolk, was dissolved in 1539, and most of the original buildings did not survive the two Civil War sieges of Hull in 1642 and 1643.

Suffolk's nickname "Jackanapes" came from "Jack of Naples", a slang name for a monkey at the time. This was probably due to his heraldic badge, which consisted of an "ape's clog", i.e. a wooden block chained to a pet monkey to prevent it escaping. The phrase "jackanape" later came to mean an impertinent or conceited person, due to the popular perception of Suffolk as a ''

Suffolk's nickname "Jackanapes" came from "Jack of Naples", a slang name for a monkey at the time. This was probably due to his heraldic badge, which consisted of an "ape's clog", i.e. a wooden block chained to a pet monkey to prevent it escaping. The phrase "jackanape" later came to mean an impertinent or conceited person, due to the popular perception of Suffolk as a ''

favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated s ...

of the weak king Henry VI of England, and consequently a leading figure in the English government where he became associated with many of the royal government's failures of the time, particularly on the war in France. Suffolk also appears prominently in Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's '' Henry VI'', parts 1 and 2.

He fought in the Hundred Years' War and participated in campaigns of Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1 ...

, and then continued to serve in France for King Henry VI. He was one of the English commanders at the failed Siege of Orléans

The siege of Orléans (12 October 1428 – 8 May 1429) was the watershed of the Hundred Years' War between France and England. The siege took place at the pinnacle of English power during the later stages of the war. The city held strategic an ...

. He favoured a diplomatic rather than military solution to the deteriorating situation in France, a stance which would later resonate well with King Henry VI.

Suffolk became a dominant figure in the government, and was at the forefront of the main policies conducted during the period. He played a central role in organizing the Treaty of Tours

The Treaty of Tours was an attempted peace agreement between Henry VI of England and Charles VII of France, concluded by their envoys on 28 May 1444 in the closing years of the Hundred Years' War. The terms stipulated the marriage of Charles ...

(1444), and arranged the king's marriage to Margaret of Anjou. At the end of Suffolk's political career, he was accused of maladministration

Maladministration is the actions of a government body which can be seen as causing an injustice. The law in the United Kingdom says Ombudsmen must investigate maladministration.

The definition of maladministration is wide and can include:

*Delay ...

by many and forced into exile. At sea on his way out, he was caught by an angry mob, subjected to a mock trial

A mock trial is an act or imitation trial. It is similar to a moot court, but mock trials simulate lower-court trials, while moot court simulates appellate court hearings. Attorneys preparing for a real trial might use a mock trial consisti ...

, and beheaded.

His estates were forfeited to the crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

but later restored to his only son, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

. His political successor was the Duke of Somerset

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

.

Biography

Hugh de Stafford, 2nd Earl of Stafford

Hugh may refer to:

*Hugh (given name)

Noblemen and clergy French

* Hugh the Great (died 956), Duke of the Franks

* Hugh Magnus of France (1007–1025), co-King of France under his father, Robert II

* Hugh, Duke of Alsace (died 895), modern-day ...

, KG, and Philippa de Beauchamp

Philippa de Stafford, Countess of Stafford (before 1344 – 6 April 1386), was a late medieval English noblewoman and the daughter of Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick, KG, and Katherine Mortimer. Her maternal grandfather was the po ...

.

Almost continually engaged in the wars in France, he was seriously wounded during the Siege of Harfleur

The siege of Harfleur (18 August – 22 September 1415) was conducted by the English army of King Henry V in Normandy, France, during the Hundred Years' War. The defenders of Harfleur surrendered to the English on terms and were treated as pr ...

(1415), where his father died from dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

. Later that year his older brother Michael, 3rd Earl of Suffolk, was killed at the Battle of Agincourt, and William succeeded as 4th earl. He served in all the later French campaigns of the reign of Henry V, and in spite of his youth held high command on the marches of Normandy in 1421–22.

In 1423 he joined Thomas, Earl of Salisbury in Champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, ...

. He fought under John, Duke of Bedford, at the Battle of Verneuil

The Battle of Verneuil was a battle of the Hundred Years' War, fought on 17 August 1424 near Verneuil-sur-Avre in Normandy between an English army and a combined Franco- Scottish force, augmented by Milanese heavy cavalry. The battle was a s ...

on 17 August 1424, and throughout the next four years was Salisbury's chief lieutenant in the direction of the war. He became co-commander of the English forces at the Siege of Orléans

The siege of Orléans (12 October 1428 – 8 May 1429) was the watershed of the Hundred Years' War between France and England. The siege took place at the pinnacle of English power during the later stages of the war. The city held strategic an ...

(1429), after the death of Salisbury.

When the city was relieved by Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronat ...

in 1429, he managed a retreat to Jargeau

Jargeau () is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France.

It lies about south of Paris.

Geography

The town is located in the French natural region of the Loire Valley, the former province of Orleans and the urban area of Orl ...

where he was forced to surrender on 12 June. He was captured by a French squire named . Admiring the young soldier's bravery, the earl decided to knight him before surrendering. This dubbing has remained famous in French history and literature and has been recounted by the writer Alexandre Dumas. He remained a prisoner of Charles VII for two years, and was ransomed in 1431, after fourteen years' continuous field service.

After his return to the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various History of Anglo-Saxon England, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, ...

in 1434, he was made Constable of Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

. He became a courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the official ...

and a close ally of Cardinal Henry Beaufort

Cardinal Henry Beaufort (c. 1375 – 11 April 1447), Bishop of Winchester, was an English prelate and statesman who held the offices of Bishop of Lincoln (1398) then Bishop of Winchester (1404) and was from 1426 a Cardinal of the Church of Ro ...

. Despite the diplomatic failure of the Congress of Arras, the cardinal's authority remained strong and Suffolk gained increasing influence.

His most notable accomplishment in this period was negotiating the marriage of King Henry VI with Margaret of Anjou in 1444, which he achieved despite initial reluctance, and included a two years' truce. This earned him a promotion from Earl to Marquess of Suffolk. However, a secret clause was put in the agreement which gave Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

and Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

* County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duk ...

back to France, which was to contribute to his downfall.

With the deaths in 1447 of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester

Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester (3 October 139023 February 1447) was an English prince, soldier, and literary patron. He was (as he styled himself) "son, brother and uncle of kings", being the fourth and youngest son of Henry IV of E ...

(shortly after his arrest for treason), and Cardinal Beaufort, Suffolk became the principal power behind the throne

The phrase "power behind the throne" refers to a person or group that informally exercises the real power of a high-ranking office, such as a head of state. In politics, it most commonly refers to a relative, aide, or nominal subordinate of a poli ...

of the weak and compliant Henry VI. In short order, he was appointed Chamberlain, Admiral of England, and to several other important offices. He was created Earl of Pembroke

Earl of Pembroke is a title in the Peerage of England that was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title, which is associated with Pembroke, Pembrokeshire in West Wales, has been recreated ten times from its origin ...

in 1447, and Duke of Suffolk

Duke of Suffolk is a title that has been created three times in the peerage of England.

The dukedom was first created for William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, William de la Pole, who had already been elevated to the ranks of earl and marquess ...

in 1448. However, Suffolk was suspected of responsibility in Humphrey's death, and later of being a traitor.

On 16 July he met in secret with Jean, Count de Dunois, at his mansion of the Rose in Candlewick Street, the first of several meetings in London at which they planned a French invasion. Suffolk passed Council minutes to Dunois, the French hero of the Siege of Orleans. It was rumoured that Suffolk never paid his ransom of £20,000 owed to Dunois. The Lord Treasurer, Ralph Cromwell Ralph de Cromwell may refer to:

*Ralph de Cromwell, 1st Baron Cromwell (died 1398)

*Ralph de Cromwell, 2nd Baron Cromwell

*Ralph de Cromwell, 3rd Baron Cromwell

Ralph de Cromwell, 3rd Baron Cromwell ( – 4 January 1456) was an English politic ...

, wanted heavy taxes from Suffolk; the duke's powerful enemies included John Paston and Sir John Fastolf

Sir John Fastolf (6 November 1380 – 5 November 1459) was a late medieval English landowner and knight who fought in the Hundred Years' War. He has enjoyed a more lasting reputation as the prototype, in some part, of Shakespeare's charact ...

. Many blamed Suffolk's retainers for lawlessness in East Anglia.

The following three years saw the near-complete loss of the English possessions in northern France (Rouen, Normandy etc.). Suffolk could not avoid taking the blame for these failures, partly because of the loss of Maine and Anjou through his marriage negotiations regarding Henry VI. When parliament met in November 1449, the opposition showed its strength by forcing the treasurer, Adam Moleyns

Adam Moleyns (died 9 January 1450), Bishop of Chichester, was an English bishop, lawyer, royal administrator and diplomat. During the minority of Henry VI of England, he was clerk of the ruling council of the Regent.

Life

Moleyns had the livin ...

, to resign.

Moleyns was murdered by sailors at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

on 9 January 1450. Suffolk, realizing that an attack on himself was inevitable, boldly challenged his enemies in parliament, appealing to the long and honourable record of his public services. However, on 28 January he was arrested, imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

and impeached in parliament by the Commons.

The King intervened to protect his favourite, who was banished for five years, but on his journey to Calais his ship was intercepted by the ship ''Nicholas of the Tower''. Suffolk was captured, subjected to a mock trial, and executed by beheading. His body was later found on the sands near Dover, and was probably brought to a church in Suffolk, possibly Wingfield. He was interred in the Carthusian Priory in Hull by his widow Alice, as was his wish, and not in the church at Wingfield, as is often stated. The Priory, founded in 1377 by his grandfather the first Earl of Suffolk, was dissolved in 1539, and most of the original buildings did not survive the two Civil War sieges of Hull in 1642 and 1643.

The King intervened to protect his favourite, who was banished for five years, but on his journey to Calais his ship was intercepted by the ship ''Nicholas of the Tower''. Suffolk was captured, subjected to a mock trial, and executed by beheading. His body was later found on the sands near Dover, and was probably brought to a church in Suffolk, possibly Wingfield. He was interred in the Carthusian Priory in Hull by his widow Alice, as was his wish, and not in the church at Wingfield, as is often stated. The Priory, founded in 1377 by his grandfather the first Earl of Suffolk, was dissolved in 1539, and most of the original buildings did not survive the two Civil War sieges of Hull in 1642 and 1643.

Marriage and descendants

Suffolk was married on 11 November 1430 (date of licence), to (as her third husband) Alice Chaucer (1404–1475), daughter ofThomas Chaucer

Thomas Chaucer (c. 136718 November 1434) was an English courtier and politician. The son of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer and his wife Philippa Roet, Thomas was linked socially and by family to senior members of the English nobility, though h ...

of Ewelme

Ewelme () is a village and civil parish in the Chiltern Hills in South Oxfordshire, north-east of the market town of Wallingford. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 1,048. To the east of the village is Cow Common and to the ...

, Oxfordshire, and granddaughter of the notable poet Geoffrey Chaucer and his wife, Philippa Roet

Philippa de Roet (also known as Philippa Pan or Philippa Chaucer; – c. 1387) was an English courtier, the sister of Katherine Swynford, third wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (a son of King Edward III), and the wife of the poet Geoffre ...

. In 1437, Henry VI licensed the couple to establish a chantry and almshouse for thirteen poor men at Ewelme, which they endowed with land at Ewelme and in Buckinghamshire, Hampshire and Wiltshire; the charitable trust continues to this day.

Suffolk's only known legitimate son, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, became the second Duke of Suffolk in 1463. Suffolk also fathered an illegitimate daughter, Jane de la Pole. Her mother is said to have been a nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

, Malyne de Cay. "The nighte before that he was yolden Franco-Scottish forces ofJane de la Pole (died 28 February 1494) was married before 1450 to Thomas Stonor (1423–1474), of Stonor inJoan of Arc Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronat ...on 12 June 1429] he laye in bed with a nonne whom he toke oute of holy profession and defouled, whose name was Malyne de Cay, by whom he gate a daughter, now married to Stonard of Oxonfordshire."

Pyrton

Pyrton is a small village and large civil parish in Oxfordshire about north of the small town of Watlington and south of Thame. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 227. The toponym is from the Old English meaning "pear-tre ...

, Oxfordshire.

Jackanapes

Suffolk's nickname "Jackanapes" came from "Jack of Naples", a slang name for a monkey at the time. This was probably due to his heraldic badge, which consisted of an "ape's clog", i.e. a wooden block chained to a pet monkey to prevent it escaping. The phrase "jackanape" later came to mean an impertinent or conceited person, due to the popular perception of Suffolk as a ''

Suffolk's nickname "Jackanapes" came from "Jack of Naples", a slang name for a monkey at the time. This was probably due to his heraldic badge, which consisted of an "ape's clog", i.e. a wooden block chained to a pet monkey to prevent it escaping. The phrase "jackanape" later came to mean an impertinent or conceited person, due to the popular perception of Suffolk as a ''nouveau riche

''Nouveau riche'' (; ) is a term used, usually in a derogatory way, to describe those whose wealth has been acquired within their own generation, rather than by familial inheritance. The equivalent English term is the "new rich" or "new money" ( ...

'' upstart; his great-grandfather

Grandparents, individually known as grandmother and grandfather, are the parents of a person's father or mother – paternal or maternal. Every sexually-reproducing living organism who is not a genetic chimera has a maximum of four genetic gra ...

had been a wool merchant from Hull.

Portrayals in drama, verse and prose

*Suffolk is a major character in twoShakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

plays. His negotiation of the marriage of Henry and Margaret is portrayed in ''Henry VI, Part 1

''Henry VI, Part 1'', often referred to as ''1 Henry VI'', is a history play by William Shakespeare—possibly in collaboration with Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Nashe—believed to have been written in 1591. It is set during the lifetime ...

''. Shakespeare's version has Suffolk fall in love with Margaret. He negotiates the marriage so that he and she can be close to one another. His disgrace and death are depicted in ''Henry VI, Part 2

''Henry VI, Part 2'' (often written as ''2 Henry VI'') is a Shakespearean history, history play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1591 and set during the lifetime of King Henry VI of England. Whereas ''Henry VI, Part 1'' ...

''. Shakespeare departs from the historical record by having Henry banish Suffolk for complicity in the murder of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. Suffolk is murdered by a pirate named Walter Whitmore (fulfilling a prophecy given earlier in the play proclaiming he will "die by Water"), and Margaret later wanders to her castle carrying his severed head and grieving.

*His murder is the subject of the traditional English folk ballad "Six Dukes Went a-Fishing

"Six Dukes Went a-Fishing" (Roud 78) is a traditional English folk ballad.

Synopsis

Six dukes go to the coast on a fishing trip but find the body of another duke, that of Grantham, washed up on the shore. They take him away, embalm his remains wit ...

" (Roud

The Roud Folk Song Index is a database of around 250,000 references to nearly 25,000 songs collected from oral tradition in the English language from all over the world. It is compiled by Steve Roud (born 1949), a former librarian in the London ...

#78)

*Suffolk is the protagonist in Susan Curran's historical novel ''The Heron's Catch'' (1989).

* He plays a role in many of the seventeen Dame Frevisse detective novels of Margaret Frazer

Margaret Frazer, born Gail Lynn Brown (November 26, 1946 – February 4, 2013), was an American historical novelist, best known for more than twenty historical mystery novels and a variety of short stories. The pen name was originally shared by Fr ...

, set in England in the 1440s.

*Suffolk is a significant character in Cynthia Harnett

Cynthia Harnett (22 June 1893 – 25 October 1981) was an English author and illustrator, mainly of children's books. She is best known for six historical novels that feature ordinary teenage children involved in events of national significance, ...

's historical novel for children, '' The Writing on the Hearth'' (1971)

*Suffolk is one of the three dedicatees of Geoffrey Hill

Sir Geoffrey William Hill, FRSL (18 June 1932 – 30 June 2016) was an English poet, professor emeritus of English literature and religion, and former co-director of the Editorial Institute, at Boston University. Hill has been considered to be ...

's sonnet sequence, "Funeral Music" (first published in ''Stand'' magazine; collected in ''King Log'', Andre Deutsch 1968). Hill speculates about him in the essay appended to the poems.

*Suffolk is one of the main characters in Conn Iggulden

Connor Iggulden (; born ) is a British author who writes historical fiction, most notably the ''Emperor'' series and ''Conqueror'' series. He also co-authored '' The Dangerous Book for Boys'' along with his brother Hal Iggulden. In 2007, Iggul ...

's '' Wars of the Roses: Stormbird'', about the end of the Hundred Years' War and the start of the Wars of the Roses.

See also

* Battle of Jargeau *Battle of Patay

The Battle of Patay, fought on 18 June 1429 during the Hundred Years' War, was the culmination of the Loire Campaign between the French and English in north-central France. In this engagement, the horsemen of the French vanguard inflicted heavy ...

*Battle of Cravant

The Battle of Cravant was fought on 31 July 1423, during the Hundred Years' War between English and French forces at the village of Cravant in Burgundy, at a bridge and ford on the banks of the river Yonne, a left-bank tributary of the Seine, ...

*Siege of Montargis

The siege of Montargis (15 July – 5 September 1427) took place during the Hundred Years War. A French relief army under Jean de Dunois routed an English force led by the Earl of Warwick.

Prelude

In June 1427, John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford ...

* John and William Merfold

*Jack Cade's Rebellion

Jack Cade's Rebellion was a popular revolt in 1450 against the government of England, which took place in the south-east of the country between the months of April and July. It stemmed from local grievances regarding the corruption, maladmin ...

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Bibliography

* * * * * *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Suffolk, William De La Pole, 1st Duke Of 1396 births 1450 deaths 15th-century English Navy personnel Lord High Admirals of England 101William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

Earls of Pembroke

Knights of the Garter

People executed by decapitation

People from Mid Suffolk District

Holders of the Honour of Wallingford

Military personnel from Suffolk