William Beach Thomas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

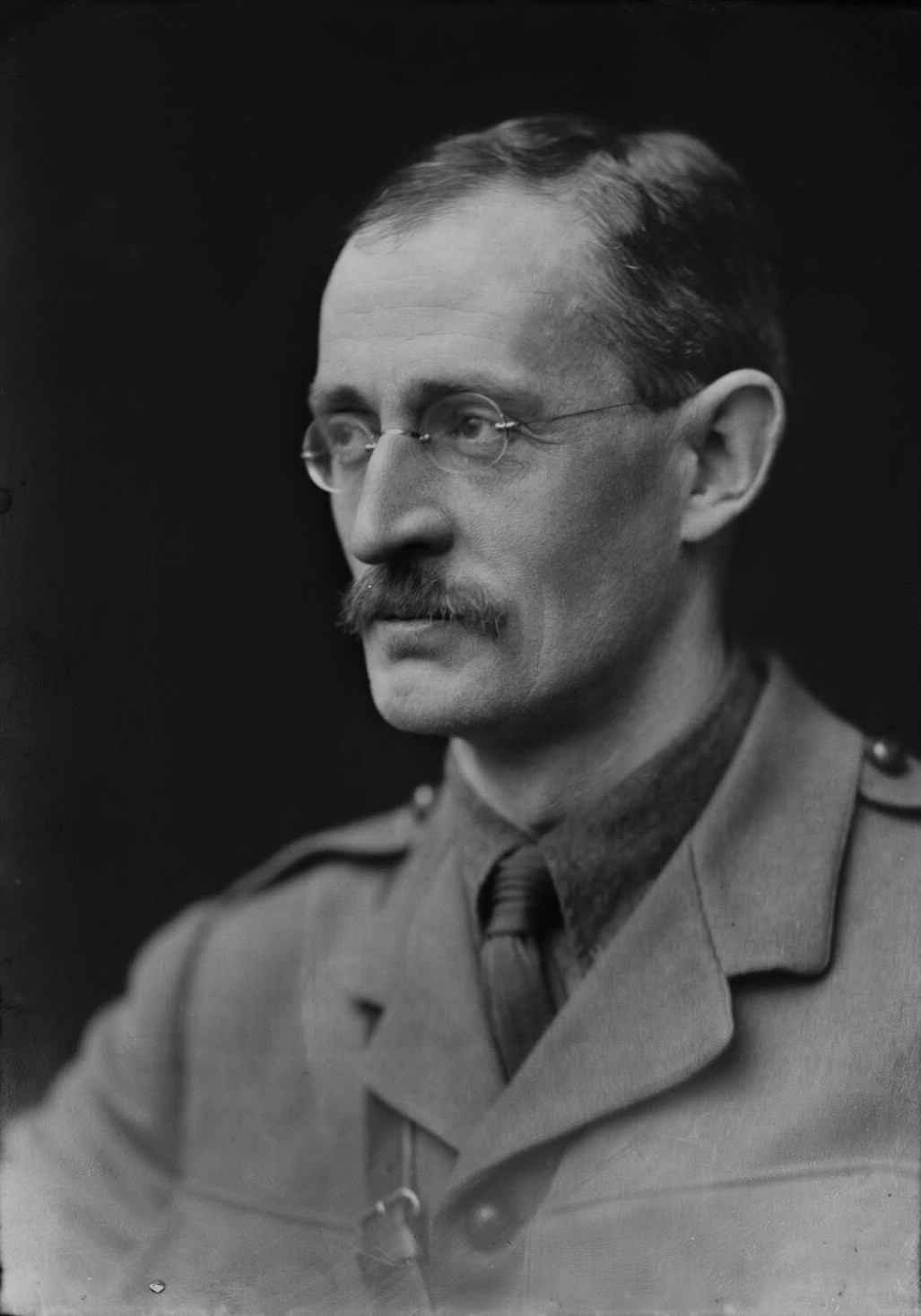

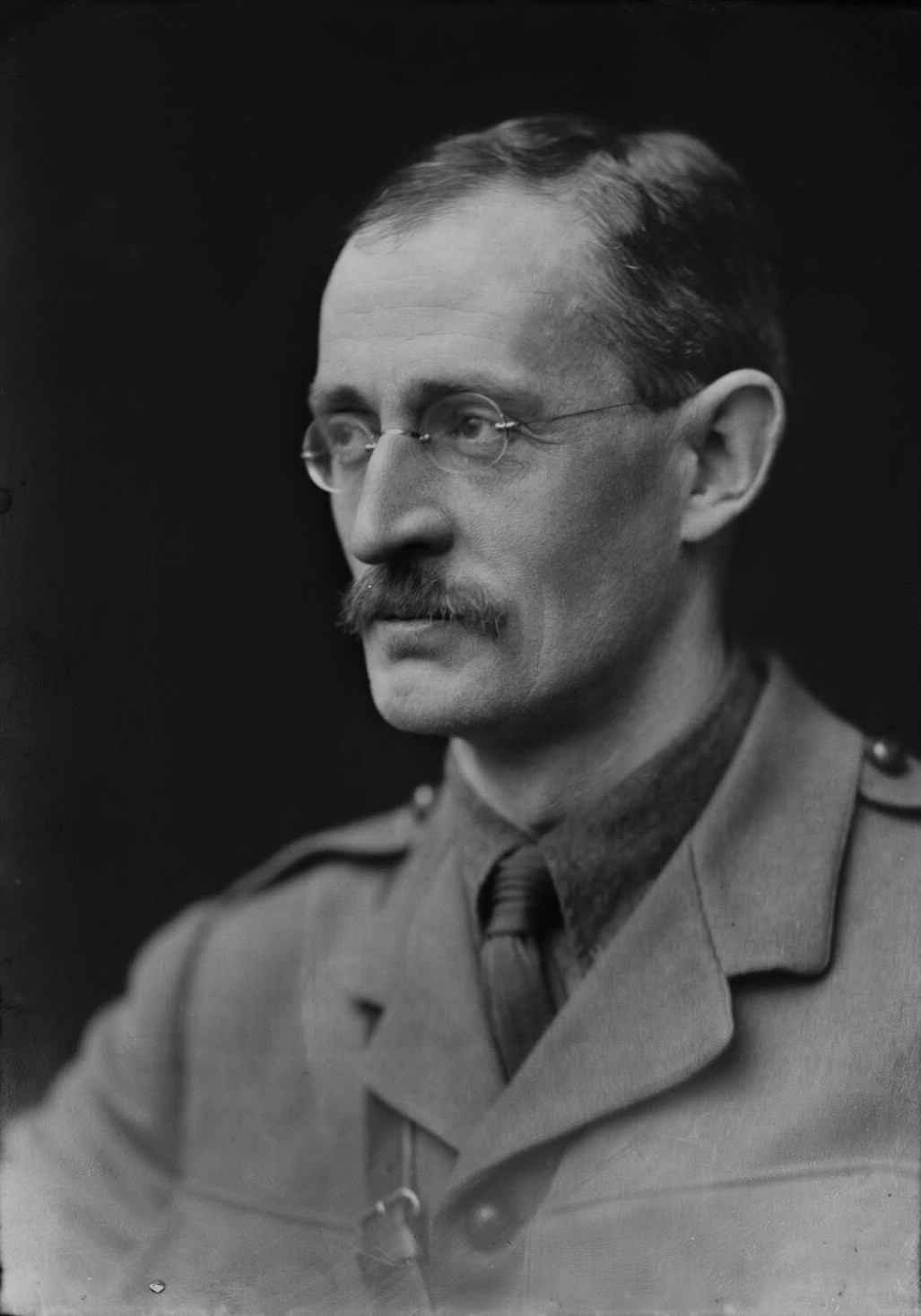

Sir William Beach Thomas, (22 May 186812 May 1957) was a British author and journalist known for his work as a war correspondent and his writings about nature and country life.

Thomas was the son of a clergyman in

Sir William Beach Thomas, (22 May 186812 May 1957) was a British author and journalist known for his work as a war correspondent and his writings about nature and country life.

Thomas was the son of a clergyman in

The ''Daily Mail'' sent William Beach Thomas to France as a war correspondent during the First World War. Many newspapers were keen to support the war effort and to take advantage of the demand for news from the

The ''Daily Mail'' sent William Beach Thomas to France as a war correspondent during the First World War. Many newspapers were keen to support the war effort and to take advantage of the demand for news from the  Northcliffe's brother,

Northcliffe's brother,  In 1918, William Beach Thomas published a book based on his wartime experiences, entitled ''With the British on the Somme''. It was a favourable depiction specifically of the English soldier, somewhat contrary to the official line that tried to emphasise that this was a British war rather than an English one. A review in ''The Times Literary Supplement'' noted that Thomas

In 1918, Northcliffe asked Thomas to travel to the US. According to Thomas, the rationale for the trip was that "he didn't know what the Americans were doing, and they did not know what we were thinking". He met with influential people such as

In 1918, William Beach Thomas published a book based on his wartime experiences, entitled ''With the British on the Somme''. It was a favourable depiction specifically of the English soldier, somewhat contrary to the official line that tried to emphasise that this was a British war rather than an English one. A review in ''The Times Literary Supplement'' noted that Thomas

In 1918, Northcliffe asked Thomas to travel to the US. According to Thomas, the rationale for the trip was that "he didn't know what the Americans were doing, and they did not know what we were thinking". He met with influential people such as

Much of one of Thomas's books, ''The English Landscape'' (1938), had previously appeared in various issues of ''Country Life'' magazine, and in part echoed concerns raised by

Much of one of Thomas's books, ''The English Landscape'' (1938), had previously appeared in various issues of ''Country Life'' magazine, and in part echoed concerns raised by

''On Taking a House''

(Edward Arnold: 1905) *''From a Hertfordshire Cottage'' (Alston Rivers: 1908) *Preface to C. D. McKay's ''The French Garden: A Diary and Manual of Intensive Cultivation'' (Associated Newspapers: 1908, reprinted as ''The French Garden In England'', 1909) *''Our Civic Life'' (Alston Rivers: 1908) *''The English Year'' (three volumes, co-authored with A. K. Collett; T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1913–14)

''Autumn and Winter''''Spring''''Summer''

*''With the British on the Somme'' (Methuen: 1917)

''Birds Through The Year''

(co-authored with A. K. Collett; T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1922) *''An Observer's Twelvemonth'' (Collins: 1923) *''A Traveller in News'' (Chapman and Hall: 1925) *''England Becomes Prairie'' (Ernest Benn: 1927) *''The Story of the 'Spectator'

Sir William Beach Thomas, (22 May 186812 May 1957) was a British author and journalist known for his work as a war correspondent and his writings about nature and country life.

Thomas was the son of a clergyman in

Sir William Beach Thomas, (22 May 186812 May 1957) was a British author and journalist known for his work as a war correspondent and his writings about nature and country life.

Thomas was the son of a clergyman in Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and North ...

. He was educated at Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into th ...

and Christ Church, Oxford, before he embarked on a short-lived career as a schoolmaster. Finding that work unpleasant, he turned his attention to writing articles for newspapers and periodicals and began to write books.

During the early part of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

, Thomas defied military authorities to report news stories from the Western Front for his employer, the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

''. As a result, he was briefly arrested before being granted official accreditation as a war correspondent. His reportage for the remainder of the war received national recognition, despite being criticised by some and parodied by soldiers. His book ''With the British on the Somme'' (1917) portrayed the English soldier in a very favourable light. Both France and Britain rewarded him with knighthoods after the war, but Thomas regretted some of his wartime output.

Thomas's primary interest as an adult was in rural matters. He was conservative in his views and after the Second World War feared that the Labour government regarded the countryside only from an economic perspective. He was an advocate for the creation of national parks in England and Wales

National parks of the United Kingdom ( cy, parciau cenedlaethol; gd, pàircean nàiseanta) are areas of relatively undeveloped and scenic landscape across the country. Despite their name, they are quite different from national parks in many ot ...

and mourned the decline of traditional village society. He wrote extensively, particularly for ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper Sunday editions, published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group, Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. ...

'' newspaper and ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''Th ...

'', a conservative magazine. His book ''The English Landscape'' (1938) included selections from his contributions to '' Country Life'' magazine.

Childhood and education

William Beach Thomas was born on 22 May 1868 inGodmanchester

Godmanchester ( ) is a town and civil parish in the Huntingdonshire district of Cambridgeshire, England. It is separated from Huntingdon, to the north, by the valley of the River Great Ouse. Being on the Roman road network, the town has a lo ...

, in the county of Huntingdonshire

Huntingdonshire (; abbreviated Hunts) is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire and a historic county of England. The district council is based in Huntingdon. Other towns include St Ives, Godmanchester, St Neots and Ramsey. The p ...

, England. He was the second son of Daniel George Thomas and his wife, Rosa Beart. In 1872, his father was appointed rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Hamerton

Hamerton is a village in and former civil parish, now in the parish of Hamerton and Steeple Gidding, in Cambridgeshire, England. Hamerton lies approximately north-west of Huntingdon. Hamerton is situated within Huntingdonshire which is a non-m ...

and the countryside location of that parish inspired an affection in Beach Thomas which greatly influenced his later observational writings about natural history and rural subjects. Beach Thomas was not a hyphenated double-barrelled name

A double-barrelled name is a type of compound surname, typically featuring two words (occasionally more), often joined by a hyphen. Examples of some notable people with double-barrelled names include Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Sacha Baron ...

; he used his middle name, Beach, as part of his name as a writer, and in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

his name is "Thomas, William Beach".

Thomas attended Shrewsbury School from 1882. He was a keen sportsman there and was appointed huntsman to the Royal Shrewsbury School Hunt, the world's oldest cross-country running

Cross country running is a sport in which teams and individuals run a race on open-air courses over natural terrain such as dirt or grass. The course, typically long, may include surfaces of grass and earth, pass through woodlands and open coun ...

club. He continued his interest in sports after earning an exhibition

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibiti ...

to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1887 and became a Blue

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model. It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when ...

, representing the university in various running events over several years. He became president of the Oxford University Athletics Club and played association football

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 players who primarily use their feet to propel the ball around a rectangular field called a pitch. The objective of the game is t ...

, rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a Contact sport#Terminology, close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the Comparison of rugby league and rugby union, two codes of ru ...

, and cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

at college level. J. B. Atkins, who competed against him for the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

athletics team, said: "With his stately height and gigantic stride, he was magnificent in action; his final effort, always, triumphant, when he saw the goal of all, the tape, waiting for him, was a sight never to be forgotten – though I had a strong reason for regretting it at the time." His exhibition was superseded by a scholarship but he was not academically successful, managing only a third-class degree

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

.

Early career

Athletic prowess and the time spent in achieving it may have contributed to Thomas's poor academic performance, but probably also assisted him in getting his first job. He taught atBradfield College

Bradfield College, formally St Andrew's College, Bradfield, is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) for pupils aged 11–18, located in the small village of Bradfield in the English county of Berkshire. It is not ...

, a public school, after leaving Oxford in 1891. Although he described teaching as "uncongenial", he subsequently took a similar position at Dulwich College

Dulwich College is a 2–19 independent, day and boarding school for boys in Dulwich, London, England. As a public school, it began as the College of God's Gift, founded in 1619 by Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn, with the original purpose o ...

in 1897, where he remained until the following year. Journalism became the object of his interest; he contributed columns for '' The Globe'', '' The Outlook'' and '' The Saturday Review'', as well as for many other publications of which he was not a member of staff. He also wrote a book entitled ''Athletics'', published by Ward Lock & Co

Ward, Lock & Co. was a publishing house in the United Kingdom that started as a partnership and developed until it was eventually absorbed into the publishing combine of Orion Publishing Group.

History

Ebenezer Ward and George Lock started a p ...

in 1901, following his contribution of a chapter titled "Athletics and Schools" to the ''Athletics'' volume in the Badminton Library

The ''Badminton Library'', called in full ''The Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes'', was a sporting and publishing project conceived by Longmans Green & Co. and edited by Henry Somerset, 8th Duke of Beaufort (1824–1899). Between 1885 a ...

series, published by Longman, Green & Co in 1900 and edited by Montague Shearman

Sir Montague Shearman (7 April 1857 – 6 January 1930) was an English judge and athlete. He is best remembered as co-founder of the Amateur Athletics Association in 1880.

Biography

Early life and career

Shearman was the second son of ...

. He became a regular reviewer for ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication ...

'' from its formation in 1902.

The ''Daily Mail'' took on Thomas as a writer of material relating to the countryside. Lord Northcliffe

Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (15 July 1865 – 14 August 1922), was a British newspaper and publishing magnate. As owner of the ''Daily Mail'' and the ''Daily Mirror'', he was an early developer of popular journal ...

, who owned the newspaper, recognised that Thomas needed to live in a rural environment if he was to perform his duties well. This understanding delighted Thomas, because it meant he could limit his visits to London. He moved to the Mimram Valley in Hertfordshire, and thereafter held Northcliffe in high regard. Thomas reported on the 78th meeting of the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scien ...

in Dublin in 1908.

Thomas's ''From a Hertfordshire Cottage'' was published in 1908, followed by a three-volume collaboration with A. K. Collett, ''The English Year'' (1913–14). He did not entirely abandon his interest in athletics and was one of those in Britain who criticised his country

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, ...

's poor performance in the 1912 Olympic Games

Year 191 ( CXCI) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Apronianus and Bradua (or, less frequently, year 944 ''Ab urbe condi ...

. Writing that the Olympics were by then being seen as a measure of "national vitality", he explained

War correspondent

The ''Daily Mail'' sent William Beach Thomas to France as a war correspondent during the First World War. Many newspapers were keen to support the war effort and to take advantage of the demand for news from the

The ''Daily Mail'' sent William Beach Thomas to France as a war correspondent during the First World War. Many newspapers were keen to support the war effort and to take advantage of the demand for news from the front

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* '' The Front'', 1976 film

Music

*The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and e ...

. The British military authorities were opposed to the presence of journalists, preferring instead to control the media by issuing official press releases. Lord Kitchener Lord Kitchener may refer to:

* Earl Kitchener, for the title

* Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener

Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, (; 24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916) was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator. ...

in particular was opposed to their presence, having had bad experiences of journalists during the South African War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

. He formed a press bureau headed by , and demanded that all reports be channelled through the bureau, for review by censors; the resulting output was bland and impersonal. The newspapers countered with subterfuge. Thomas was one of several journalists who managed to reach the front lines in Belgium. He was discovered there and imprisoned for some time by the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

. He described the episode as "the longest walking tour of my life, and the queerest". Even these early unapproved reports, which consisted mostly of human interest stories

In journalism, a human-interest story is a feature story that discusses people or pets in an emotional way. It presents people and their problems, concerns, or achievements in a way that brings about interest, sympathy or motivation in the reader o ...

because there was little opportunity for contact with the British Expeditionary Force, were censored at home owing to a paradox that Thomas described: "the censors would not publish any article if it indicated that the writer had seen what he wrote of. He must write what he thought was true, not what he knew to be true."

When the British government relented in mid-1915, having been warned by Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

that the reporting limitations were affecting public opinion in the United States, Valentine Williams

George Valentine Williams, (1883–1946) was a journalist and writer of popular fiction.

Williams was born in 1883. He was the eldest son of the chief editor at Reuters; both his brother and an uncle were also journalists. He replaced Austin Har ...

became the ''Daily Mail's'' first accredited war correspondent. No longer in prison, Thomas resumed his war reporting in December of the same year, when Williams enlisted in the Irish Guards

("Who Shall Separate s")

, colors =

, identification_symbol_2 Saffron (pipes), identification_symbol_2_label = Tartan

, identification_symbol =

, identification_symbol_label = Tactical Recognition F ...

. As with the other accredited journalists, Thomas was paid by the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), Ministry of Defence (MoD ...

rather than by his newspaper, and all the correspondents were assured that they would be able to publish memoirs of their service to offset the differential between an officer's pay and that of a journalist. Thomas filed reports from places such as the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place be ...

in a format matching that of his colleagues, who regularly downplayed the unpleasant aspects of the conflict, such as the nature of death. His reports were published in the ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily tabloid. Founded in 1903, it is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the title on its masthead was simply ''The Mirror''. It had an average daily print ci ...

'' as well as the ''Daily Mail''.

The soldiers derided the attempts that were made to indoctrinate them, but the British public was more susceptible. Philip Gibbs

Sir Philip Armand Hamilton Gibbs KBE (1 May 1877 – 10 March 1962) was an English journalist and prolific author of books who served as one of five official British reporters during the First World War. Four of his siblings were also write ...

, a fellow war correspondent, noted that he and his colleagues "identified absolutely with the Armies in the field ... There was no need of censorship in our despatches. We were our own censors." The journalistic support for the cause was appreciated by military commanders such as Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, (; 19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 unti ...

, who saw the propaganda generated by the correspondents as an integral part of the Allies' efforts. Haig eventually went so far as to ask Gibbs and Thomas to produce his own weekly news-sheet. Public opinion at home may have been mollified, even uplifted, by the efforts of the correspondents, but the morale of the troops was not, despite the high demand among them for newspapers from home. One soldier, Albert Rochester, was court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of me ...

led for attempting to send to the ''Daily Mail'' a letter that stated the realities as he saw them and was critical of Thomas's work, noting the "ridiculous reports regarding the love and fellowship existing between officers and men". William Beach Thomas himself later regretted his wartime reports from the Somme, saying, "I was thoroughly and deeply ashamed of what I had written for the good reason that it was untrue ... the vulgarity of enormous headlines and the enormity of one's own name did not lessen the shame."

Northcliffe's brother,

Northcliffe's brother, Lord Rothermere

Viscount Rothermere, of Hemsted in the county of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1919 for the press lord Harold Harmsworth, 1st Baron Harmsworth. He had already been created a baronet, of Horsey in t ...

, expressed frustration with the war correspondents: "They don't know the truth, they don't speak the truth, and we know that they don't." Stephen Badsey, a historian who specialises in the First World War, has noted that their situation was not easy as they "found themselves as minor players trapped in a complicated hierarchical structure dominated by politicians, generals and newspaper owners". Thomas received particular opprobrium. Paul Fussell

Paul Fussell Jr. (22 March 1924 – 23 May 2012) was an American cultural and literary historian, author and university professor. His writings cover a variety of topics, from scholarly works on eighteenth-century English literature to commentar ...

, the historian, describes him as "notoriously fatuous" during the war period. Peter Stothard

Sir Peter Stothard (born 28 February 1951) is a British author, journalist and critic. From 1992 to 2002 he was editor of ''The Times'' and from 2002 to 2016 editor of ''The Times Literary Supplement'', the only journalist to have held both role ...

, editor of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ...

'' between 1992 and 2002, describes him as "a quietly successful countryside columnist and literary gent who became a calamitous ''Daily Mail'' war correspondent" and believes that he may have been the inspiration for the character of William Boot

William Boot is a fictional journalist who is the protagonist in the 1938 Evelyn Waugh comic novel ''Scoop.''

Character

Boot is the young author of a regular column on country life for a London newspaper named the ''Daily Beast''. His affected st ...

in Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires '' Decl ...

's novel ''Scoop

Scoop, Scoops or The scoop may refer to:

Objects

* Scoop (tool), a shovel-like tool, particularly one deep and curved, used in digging

* Scoop (machine part), a component of machinery to carry things

* Scoop stretcher, a device used for casualty ...

''. John Simpson, a war correspondent, describes Thomas as "charming but unlovable" and thinks that the soldiers despised him more than they did the other British war correspondents, even though all those journalists were playing a similar disinformation role. They considered his writing to be a trivialisation of the realities of war, jingoistic, pompous and particularly self-promoting, often giving the reader an impression that he was writing from the battlefield when in fact he was being fed information of dubious value by the military authorities while based in their headquarters.

An example of Thomas's reporting is as follows:

Thomas's style was parodied using the by-line of ''Teech Bomas'' in the '' Wipers Times'', a trench newspaper, but he was lauded by the readers back in Britain. One example from the ''Wipers Times'', based on a report published in the ''Daily Mail'' of 18 September 1916, reads:

In 1918, William Beach Thomas published a book based on his wartime experiences, entitled ''With the British on the Somme''. It was a favourable depiction specifically of the English soldier, somewhat contrary to the official line that tried to emphasise that this was a British war rather than an English one. A review in ''The Times Literary Supplement'' noted that Thomas

In 1918, Northcliffe asked Thomas to travel to the US. According to Thomas, the rationale for the trip was that "he didn't know what the Americans were doing, and they did not know what we were thinking". He met with influential people such as

In 1918, William Beach Thomas published a book based on his wartime experiences, entitled ''With the British on the Somme''. It was a favourable depiction specifically of the English soldier, somewhat contrary to the official line that tried to emphasise that this was a British war rather than an English one. A review in ''The Times Literary Supplement'' noted that Thomas

In 1918, Northcliffe asked Thomas to travel to the US. According to Thomas, the rationale for the trip was that "he didn't know what the Americans were doing, and they did not know what we were thinking". He met with influential people such as Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of ...

, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

during this visit.

William Beach Thomas sometimes accompanied King George V and the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

on their visits to France, noting on one occasion a situation he considered reminiscent of Henry II and Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

:

Thomas's war work led to official recognition, as it did for many of the correspondents and newspaper owners; France made him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

in 1919 and he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(KBE) in 1920. In 1923, Gibbs said of the KBE, which he too received: "I was not covetous of that knighthood and indeed shrank from it so much that I entered into a compact with Beach Thomas to refuse it. But things had gone too far, and we could not reject the title with any decency." This quandary was caused by realisation of the gulf between what they had reported and what had actually happened.

Later years

After the war, Thomas stayed in Germany until 1919 and returned there in 1923 at the time of theOccupation of the Ruhr

The Occupation of the Ruhr (german: link=no, Ruhrbesetzung) was a period of military occupation of the Ruhr region of Germany by France and Belgium between 11 January 1923 and 25 August 1925.

France and Belgium occupied the heavily indus ...

. He also undertook a tour of the world for the ''Daily Mail'' and ''The Times'' in 1922. His main focus returned to his lifelong interest in matters of the countryside, notably in his writings for ''The Observer'' from 1923 to 1956. Thomas was also a regular contributor of notes on nature, gardening and country life to ''The Spectator'' for almost thirty years, with some short breaks between 1935 and 1941, when H. E. Bates

Herbert Ernest Bates (16 May 1905 – 29 January 1974), better known as H. E. Bates, was an English writer. His best-known works include ''Love for Lydia'', '' The Darling Buds of May'', and '' My Uncle Silas''.

Early life

H.E. Bates was ...

took over responsibility. In 1928 Thomas produced a history of the magazine under the title of ''The Story of the 'Spectator'', in commemoration of its centenary. He wrote many more books and articles in his later years, as well as two autobiographical books: ''A Traveller in News'' (1925) and ''The Way of a Countryman'' (1944). Fond of peppering quotations throughout his writing, his style was considered to be clear but his hand was poor; a profile of him in ''The Observer'' said "perhaps he gave less pleasure to those who had to decipher his handwriting. Rarely has more limpid English been conveyed in a script more obscure."

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalita ...

wrote in the ''Manchester Evening News

The ''Manchester Evening News'' (''MEN'') is a regional daily newspaper covering Greater Manchester in North West England, founded in 1868. It is published Monday–Saturday; a Sunday edition, the ''MEN on Sunday'', was launched in February 201 ...

'':

Even as traditional English village life was in collapse, Thomas saw the romanticised paternalism and general life of the village as the epitome of English society and equivalent to anything that might be found elsewhere in the world. He said that one of the aspects of village life he admired was that "comparative wealth here

Here is an adverb that means "in, on, or at this place". It may also refer to:

Software

* Here Technologies, a mapping company

* Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps), a mobile app and map website by Here

Television

* Here TV (formerly "here!"), a ...

is admired, not envied". He also viewed the natural world as something to be wondered at rather than scientifically examined. In his last column for ''The Spectator'', written in September 1950, he wrote:

In his desire to encourage a love of the countryside, especially during the Second World War, William Beach Thomas was similar to other writers on rural matters, such as G. M. Trevelyan

George Macaulay Trevelyan (16 February 1876 – 21 July 1962) was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the ...

and H. J. Massingham

Harold John Massingham (25 March 1888 – 22 August 1952) was a prolific British writer on ruralism, matters to do with the countryside and agriculture. He was also a published poet.

Life

Massingham was the son of the journalist H. W. Massingha ...

. He described Massingham as "perhaps the best of all present writers on Rural England" and considered him among those writers who were "so fond of the past that they seem sometimes almost to despair of the future". Malcolm Chase

Malcolm Sherwin Chase (3 February 1957 – 29 February 2020) was a social historian noted especially for his work on Chartism.

Early life and education

Chase was born in Grays to the carpenter (later building surveyor) Sherwin Chase and bank cle ...

, a historian, says that these authors, including Thomas himself, advocated an ultra-conservative, socially reactionary and idealistic philosophy that formed an important part of a national debate about the future of the land and agriculture. This attitude was coupled with an increasing public interest in pastimes such as cycling, motoring and walking; it was supported by the publication of popular, fairly cheap and colourful articles, books and maps that catered both to those pursuing such interests and those who were concerned about conservation and the effects of the influx of urban and suburban visitors. John Musty, in his comparative literary review of the works of Thomas and Massingham, believes that Thomas had a more "gentle touch" than Massingham, whose writings have "frequently been judged as narrow and reactionary"; he quotes Thomas as saying of the likes of Massingham that they "preach an impossible creed, albeit an attractive one".

Much of one of Thomas's books, ''The English Landscape'' (1938), had previously appeared in various issues of ''Country Life'' magazine, and in part echoed concerns raised by

Much of one of Thomas's books, ''The English Landscape'' (1938), had previously appeared in various issues of ''Country Life'' magazine, and in part echoed concerns raised by Clough Williams-Ellis

Sir Bertram Clough Williams-Ellis, CBE, MC (28 May 1883 – 9 April 1978) was a Welsh architect known chiefly as the creator of the Italianate village of Portmeirion in North Wales. He became a major figure in the development of Welsh architec ...

in works such as his ''England and the Octopus'' (1928). Williams-Ellis believed that building on greenfield land

Greenfield land is a British English term referring to undeveloped land in an urban or rural area either used for agriculture or landscape design, or left to evolve naturally. These areas of land are usually agricultural or amenity properties ...

was too great a price to pay for socio-economic progress. Thomas argued in favour of protecting open spaces by creating national parks, for which he thought that the coastline would be the most suitable candidate. He stressed the relationship between the people and the land and saw a need for planning control to manage human ingress into areas that remained mostly untouched. In 1934 he supported the Nature Lovers Association in its appeal to make the mountainous Snowdonia

Snowdonia or Eryri (), is a mountainous region in northwestern Wales and a national park of in area. It was the first to be designated of the three national parks in Wales, in 1951.

Name and extent

It was a commonly held belief that the na ...

region, near the coast of North Wales

North Wales ( cy, Gogledd Cymru) is a region of Wales, encompassing its northernmost areas. It borders Mid Wales to the south, England to the east, and the Irish Sea to the north and west. The area is highly mountainous and rural, with Snowdonia N ...

, such an entity. He also supported the Commons, Open Spaces and Footpaths Preservation Society.

In 1931 Thomas lamented the inability of the National Farmers Union of England and Wales

The National Farmers' Union (NFU) is a member organisation/industry association for farmers in England and Wales. It is the largest farmers' organisation in the countries, and has over 300 branch offices.

History

On 10 December 1908, a meetin ...

to hold up what he saw as the decline of the farming industry. In ''A Countryman's Creed'' (1946) he harked back to a lost world, perhaps even a world that was more of his imagination than it was ever real. As F. R. Leavis

Frank Raymond "F. R." Leavis (14 July 1895 – 14 April 1978) was an English literary critic of the early-to-mid-twentieth century. He taught for much of his career at Downing College, Cambridge, and later at the University of York.

Leavis r ...

had done before him, Thomas sought a rural revival to curtail what he saw as the rapid changes to traditional ways of life that had been evident in particular in the aftermath of the First World War and which were now ideologically challenged following the substantial victory of the socialist Labour Party in the 1945 general election. The new government was a threat to Thomas's view of the world because, in the words of the literary critic Robert Hemmings, it saw the countryside "as merely a giant dairy and granary for the city".

Thomas was opposed to the use of the toothed steel trap for catching rabbits, supporting the RSPCA

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) is a charity operating in England and Wales that promotes animal welfare. The RSPCA is funded primarily by voluntary donations. Founded in 1824, it is the oldest and largest a ...

in its efforts to outlaw the device and noting that it inflicted unnecessary pain and was indiscriminate in nature, sometimes trapping other animals, such as domesticated cattle and pet dogs.

Personal life and death

William Beach Thomas married Helen Dorothea Harcourt, a daughter ofAugustus George Vernon Harcourt

Augustus George Vernon Harcourt Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (24 December 1834 – 23 August 1919) was an English chemist who spent his career at Oxford University. He was one of the first scientists to do quantitative work in the field of c ...

, in April 1900, and with her had three sons and a daughter. Their second son, Michael Beach Thomas, was killed in 1941 while serving as a naval officer during the Second World War. Helen survived her husband, who died on 12 May 1957 at their home, "High Trees", Gustardwood, Wheathampstead

Wheathampstead is a village and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England, north of St Albans. The population of the ward at the 2001 census was 6,058. Included within the parish is the small hamlet of Amwell.

History

Settlements in this area were ...

, Hertfordshire. He was buried in the village churchyard at St Helen's Church. Among the obituaries of William Beach Thomas were those published in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans ar ...

'' and ''The Times''.

Books

Aside from his journalism, Thomas wrote and contributed to many books, all published in London and some also in New York. These include: *''Athletics at School'' (chapter in ''Athletics'', ed. Montague Shearman, Longmans, Green & Co.: 1898) *''Athletics'' (Ward, Lock & Co.: 1901) *''The Road to Manhood'' (G. Allen: 1904)''On Taking a House''

(Edward Arnold: 1905) *''From a Hertfordshire Cottage'' (Alston Rivers: 1908) *Preface to C. D. McKay's ''The French Garden: A Diary and Manual of Intensive Cultivation'' (Associated Newspapers: 1908, reprinted as ''The French Garden In England'', 1909) *''Our Civic Life'' (Alston Rivers: 1908) *''The English Year'' (three volumes, co-authored with A. K. Collett; T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1913–14)

''Autumn and Winter''

*''With the British on the Somme'' (Methuen: 1917)

''Birds Through The Year''

(co-authored with A. K. Collett; T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1922) *''An Observer's Twelvemonth'' (Collins: 1923) *''A Traveller in News'' (Chapman and Hall: 1925) *''England Becomes Prairie'' (Ernest Benn: 1927) *''The Story of the 'Spectator'

Viscount Astor

Viscount Astor, of Hever Castle in the County of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1917 for the financier and statesman William Waldorf Astor, 1st Baron Astor. He had already been created Baron Astor, of ...

and Keith Murray., Gollancz: 1932)

*''The Yeoman's England'' (A. Maclehose & Co.: 1934)

*''Village England'' (A. Maclehose & Co.: 1935)

*''The Squirrel's Granary: A Countryman's Anthology'' (A. Maclehose & Co.: 1936, republished by A. & C. Black in 1942 as ''A Countryman's Anthology'')

*''Hunting England: A Survey of the Sport and of Its Chief Grounds Etc'' (B. T. Batsford: 1936)

*''The Home Counties'' (chapter in ''Britain and the Beast'', ed. Clough Williams-Ellis, B. T. Batsford: 1937)

*''The English Landscape'' (Country Life: 1938)

*''The Way of a Countryman'' (M. Joseph: 1944)

*''The Poems of a Countryman'' (M. Joseph: 1945)

*''A Countryman's Creed'' (M. Joseph: 1946)

*''In Praise of Flowers'' (Evans Bros.: 1948)

*''The English Counties Illustrated'' (Odhams: 1948, ed. C. E. M. Joad; chapters on Hertfordshire and Huntingdonshire

Huntingdonshire (; abbreviated Hunts) is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire and a historic county of England. The district council is based in Huntingdon. Other towns include St Ives, Godmanchester, St Neots and Ramsey. The p ...

)

*''The Way of a Dog'' (M. Joseph: 1948)

*''Hertfordshire'' (R. Hale: 1950)

*''A Year in the Country'' (A. Wingate: 1950)

*''Gardens'' (Burke: 1952)

*Introduction to ''The New Forest and Hampshire in Pictures'' (Odhams: 1952)

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * in p. 132 ''The Wipers Times: The Complete Series of the Famous Wartime Trench Newspaper'' (2006), Hislop, Ian, Brown, Malcolm, Beaver, Patrick (compilers), Little Books, * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Thomas, William Beach 1868 births 1957 deaths People educated at Shrewsbury School Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford People from Godmanchester Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur British nature writers War correspondents of World War I English war correspondents Daily Mail journalists Masters of Dulwich College The Observer people People from Wheathampstead The Spectator people People from Hamerton