The Province of Westphalia () was a

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

of the

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

and the

Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (german: Freistaat Preußen, ) was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the domina ...

from 1815 to 1946. In turn, Prussia was the largest component state of the

German Empire from 1871 to 1918, of the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

and from 1918 to 1933, and of

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

from 1933 until 1945.

The province was formed and awarded to Prussia at the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815, in the aftermath of the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. It combined some territories that had previously belonged to Prussia with a range of other territories that had previously been independent principalities. The population included a large population of Catholics, a significant development for Prussia, which had hitherto been almost entirely Protestant. The politics of the province in the early nineteenth century saw local expectations of Prussian reforms, increased self-government, and a constitution largely stymied. The

Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

led to an effervescence of political activity in the province, but the failure of the revolution was accepted with little resistance.

Before the nineteenth century, the region's economy had been largely agricultural and many rural poor travelled abroad to find work. However, from the late eighteenth century, the coal mining and metalworking industries of the

Ruhr in the south of the province expanded rapidly, becoming the centre of the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

in Germany. This resulted in rapid population growth and the establishment of several new cities which formed the basis of the modern Ruhr urban area. It also led to the development of a strong labour movement, which led several large strikes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the province was combined with the

northern portion of

Rhine Province and the

Free State of Lippe

The Free State of Lippe (german: Freistaat Lippe) was a German state formed after the Principality of Lippe was abolished following the German Revolution of 1918.

After the end of World War II and Nazi regime, Lippe was restored. This autonom ...

to form the modern

German state of

North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia (german: Nordrhein-Westfalen, ; li, Noordrien-Wesfale ; nds, Noordrhien-Westfalen; ksh, Noodrhing-Wäßßfaale), commonly shortened to NRW (), is a state (''Land'') in Western Germany. With more than 18 million inha ...

.

Early history

Foundation and structure

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

founded the

Kingdom of Westphalia

The Kingdom of Westphalia was a kingdom in Germany, with a population of 2.6 million, that existed from 1807 to 1813. It included territory in Hesse and other parts of present-day Germany. While formally independent, it was a vassal state of the ...

as a

client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

of the

First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental E ...

in 1807. Although named for the historical region of

Westphalia

Westphalia (; german: Westfalen ; nds, Westfalen ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the regio ...

, it contained mostly

Hessian,

Angrian and

Eastphalia

Eastphalia (german: Ostfalen; Eastphalian: ''Oostfalen'') is a historical region in northern Germany, encompassing the eastern '' Gaue'' (shires) of the historic stem duchy of Saxony, roughly confined by the River Leine in the west and the Elbe ...

n territories and only a relatively small part of the region of Westphalia. After the reconquest of the region by the

Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor six ...

in 1813, it was put under the administration of the .

It was not until the

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815 that the Province of Westphalia came into being. Although Prussia had long owned territory in Westphalia, King

Frederick William III

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

made no secret of the fact that he would have preferred to annex the entirety of the

Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony (german: Königreich Sachsen), lasting from 1806 to 1918, was an independent member of a number of historical confederacies in Napoleonic through post-Napoleonic Germany. The kingdom was formed from the Electorate of Saxo ...

.

The province was formed from several territories:

* regions in Westphalia under Prussian rule since before 1800 (the

Principality of Minden

The Prince-Bishopric of Minden (german: Fürstbistum Minden; Bistum Minden; Hochstift Minden; Stift Minden) was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire. It was progressively secularized following the Protestant Reformation when ...

and the counties of

Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* F ...

,

Ravensberg and

Tecklenburg

Tecklenburg () is a town in the district of Steinfurt, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Its name comes from the ruined castle around which it was built. The town is situated on the Hermannsweg hiking trail.

The coat of arms shows an anchor ...

)

* the

Prince-Bishoprics

Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

and

Paderborn

Paderborn (; Westphalian: ''Patterbuorn'', also ''Paterboärn'') is a city in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader and ''Born'', an old German term for t ...

, acquired by Prussia in 1802–03; the northernmost parts of the geographically enormous Bishopric of Münster, however, became part of the

Kingdom of Hanover

The Kingdom of Hanover (german: Königreich Hannover) was established in October 1814 by the Congress of Vienna, with the restoration of George III to his Hanoverian territories after the Napoleonic era. It succeeded the former Electorate of Ha ...

or the

Grand Duchy of Oldenburg

The Grand Duchy of Oldenburg (, also known as Holstein-Oldenburg) was a grand duchy within the German Confederation, North German Confederation and German Empire that consisted of three widely separated territories: Oldenburg, Eutin and Bi ...

* the small

County of Limburg

Hagen-Hohenlimburg (formerly known as Limburg an der Lenne, changed to Hohenlimburg in 1903; Westphalian: ''Limmerg''), on the Lenne river, is a borough of the city of Hagen in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Hohenlimburg was formerly the ch ...

, acquired in 1808

* the portions of the

Principality of Salm

The Principality of Salm was a short-lived client state of Napoleonic France located in Westphalia.

History

Salm was created in 1802 as a state of the Holy Roman Empire in order to compensate the princes of Salm-Kyrburg and Salm-Salm, who ha ...

which had been annexed by France in 1810 and the southern part of the

Duchy of Arenberg were acquired by Prussia in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna,

* the

Duchy of Westphalia, placed under Prussian rule in 1816 following the Congress of Vienna

* the

Sayn-Wittgenstein

Sayn-Wittgenstein was a county of medieval Germany, located in the Sauerland of eastern North Rhine-Westphalia.

History

Sayn-Wittgenstein was created when Count Salentin of Sayn-Homburg, a member of the House of Sponheim, married the heiress Co ...

er principalities of

Hohenstein and

Berleburg

Bad Berleburg (, earlier also Berleburg) is a town, in the district of Siegen-Wittgenstein, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is one of Germany's largest towns by land area. It is located approximately northeast of Siegen and northwest of ...

, along with the principality of

Nassau-Siegen

Nassau-Siegen was a principality within the Holy Roman Empire that existed between 1303 and 1328, and again from 1606 to 1743. From 1626 to 1734, it was subdivided into Catholic and Protestant parts. Its capital was the city of Siegen, found ...

(in 1817)

In 1816, the district of

Essen was transferred to the

Rhine Province.

The new province had an area of . The establishment of Westphalia and the neighbouring Rhine Province marked a decisive economic and demographic shift to the west for Prussia. It also marked a significant expansion of the number of

Catholics in Prussia, which had hitherto been nearly exclusively

Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

. At the beginning of Prussian rule, the province had around 1.1 million inhabitants, of which 56% were Catholic, 43% Protestant, and 1%

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

.

With the foundation of the province, the new administrative structure created during the

Prussian reforms

The Prussian Reform Movement was a series of constitutional, administrative, social and economic reforms early in nineteenth-century Prussia. They are sometimes known as the Stein-Hardenberg Reforms, for Karl Freiherr vom Stein and Karl August ...

was introduced. The administrative incorporation of the province into the Prussian state was chiefly accomplished by the first ,

Ludwig von Vincke

Friedrich Ludwig Wilhelm Philip Freiherr von Vincke (23 December 1774 – 2 December 1844) was a Prussian statesman. Born as a member of an old Westphalian noble family and educated at three universities in a broad variety of subjects, he ...

. The province was divided administratively into three ("government districts"):

Arnsberg

Arnsberg (; wep, Arensperg) is a town in the Hochsauerland county, in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It is the location of the Regierungsbezirk Arnsberg administration and one of the three local administration offices of the Hoch ...

,

Minden, and

Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

. The borders of the province were slightly altered in 1851 and during the Weimar Republic.

In general, the Prussian administration focussed on the alignment of political institutions and administration, but legally they were distinct. In most parts of Westphalia, the

General State Laws for the Prussian States

The General State Laws for the Prussian States (german: Allgemeines Landrecht für die Preußischen Staaten, ALR) were an important code of Prussia, promulgated in 1792 and codified by Carl Gottlieb Svarez and Ernst Ferdinand Klein, under the ...

(PrALR) were the fundamental basis of the law. In the Duchy of Westphalia and the two Sayn-Wittgensteiner principalities, however, the old regional legal traditions were retained until the introduction of the (civil law code) on 1 January 1900.

Reaction to the establishment of the province

The establishment of the province provoked different reactions in the region. In areas that had already been under Prussian control, like

Minden-Ravensberg

Minden-Ravensberg was a Prussian administrative unit consisting of the Principality of Minden and the County of Ravensberg from 1719–1807. The capital was Minden. In 1807 the region became part of the Kingdom of Westphalia, a client state ...

and the

County of Mark

The County of Mark (german: Grafschaft Mark, links=no, french: Comté de La Marck, links=no colloquially known as ) was a county and state of the Holy Roman Empire in the Lower Rhenish–Westphalian Circle. It lay on both sides of the Ruhr Rive ...

, the return to their old connection with Prussia was celebrated. In

Siegerland, acceptance of Prussian rule was eased by the fact that Protestantism was the main religion. Catholic areas, like the former prince-bishoprics of Münster and Paderborn and the Duchy of Westphalia, were particularly sceptical of the new lords. The Catholic nobility, which had played a leading role in the old prince-bishoprics, were mostly hostile. Twenty years after the province's establishment,

Jacob Venedey called the Rhenanians and Westphalians ("have-to-be-Prussians").

In practice, the incorporation of the region into the Prussian state faced a number of problems. Firstly, the administrative unification was opposed by the

mediatised houses

The mediatised houses (or mediatized houses, german: Standesherren) were ruling princely and comital-ranked houses that were mediatised in the Holy Roman Empire during the period 1803–1815 as part of German mediatisation, and were later recognis ...

(). These nobles, who had ruled small principalities of their own before the Napoleonic Wars, retained special privileges of their own well into the nineteenth century. They maintained a certain amount of control or oversight over schools and churches. The second major problem for unification was the question of the redemption of manorial rights by the peasants within the context of

peasant liberation. Although a law was passed in 1820 that allowed for redemption through monetary rents, there were also numerous individual regulations and regional peculiarities. Redemption remained controversial until 1848 and prompted significant conflicts in the provincial Landtags in the

period before 1848, since these bodies were dominated by the landed nobility. The uncertainties surrounding land ownership were a cause of rural uprisings at the beginning of the

Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

. In the longer term, the fear that the peasants would be expelled from their land by great estates was not fulfilled. Instead, the two western provinces of Prussia remained the areas with the lowest numbers of large estates.

One thing that initially contributed to the acceptance of Prussia was the policy of reform which aimed at the establishment of a "civic order". This involved the creation of a predictable system of administration and justice, rights of self-administration for communities, the

emancipation of the Jews

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It incl ...

, and the liberation of the economy from

guilds. The educated bourgeois class (the ), both Protestant and Catholic, recognised that the Prussian government was the prime motor of change. In the longer term, the combination of such different territories into a single province had consequences for identity and self-perception. Throughout the 19th century, there always remained a consciousness of the old territories' pasts, but alongside this a Westphalian self-perception also developed (fostered by the Prussian government). This often came into competition with the developing German national consciousness.

Constitutional debate and the Restoration Period

Bourgeois Westphalians like and

Benedikt Waldeck were particularly hopeful for the promulgation of a constitution. In newspapers like the and , the desire for a constitution was clearly articulated from the beginning. Draft constitutions were issued by Sommer and of

Dortmund. Other participants in the debate included and . This optimistic attitude shifted with the beginning of the Restoration Period, when the absence of a national constitution and the

censorship of the press became clear. , who was later a member of the

Reichstag, wrote as a schoolboy in 1820, that it was not for the "pathetic squabbles of princes" that people had fought in 1813, but so that "justice and law would have to be the foundation of public life as well as citizenship."

The establishment of provincial parliaments () in 1823 had little impact on the criticism, since they lacked central legislative powers. They had no right to raise taxes, were not involved in the drafting of laws, and had only advisory functions on important matters. The representatives were not allowed to discuss administrative matters and their minutes were subject to censorship.

The first met in the

Münster City Hall in 1826. The high voter turnout shows that, despite all the restrictions, the bourgeoisie saw the Landtag as a forum for the expression of their views (the lower classes had no voting rights). The

Baron vom Stein as first (presiding officer of the Landtag) did not restrict discussion to purely local matters, and under the surface the constitutional question played an important role in discussions in the Landtag in 1826 and in the next Landtag in 1828. This became even clearer during the Landtag of 1830/31, when and even the noble Baron of Fürstenberg openly called for the establishment of a constitution for Prussia. The question of what such a constitution should look like was fiercely debated. Most nobles, including Fürstenberg, sought a restoration of the old order, while the bourgeoisie pursued early

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

ideas. In this, Bracht was supported by industrialist

Friedrich Harkort

Friedrich Harkort (February 22, 1793, Hagen - March 6, 1880), known as the "Father of the Ruhr," was an early prominent German industrialist and pioneer of industrial development in the Ruhr region.(29 December 2009)Friedrich Harkort - Vorbild u ...

and publisher among others. Other members of the "opposition" included the mayor of

Hagen, and the mayor of

Telgte

Telgte (German pronunciation: �tɛlktə regionally �tɛlçtə is a town in the Warendorf district, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, on the river Ems 12 km east of Münster and 15 km west of Warendorf. Telgte is famous as a place o ...

, . Even among the landed nobility, there were supporters of liberalism, such as

Georg von Vincke

Georg von Vincke (5 May 1811 – 3 June 1875) was a Prussian politician, officer, landowner and aristocrat of the Vincke family. As a political figure he was associated with the Old Liberals.

Biography

He was born in Hagen. He was the son of Ludw ...

.

The

district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municipa ...

ordinance () of 1827 also clearly diverged from the basic ideas of the Prussian reformers. It provided for the election of district councils which were basically drawn from the circle of the landed nobility and gave the people of the districts only a right to present their views for consideration; the appointment was reserved for the king. Equally untimely was the revised civic ordinance () of 1831, which heavily restricted the voting right for town councils and provided for organs of self-government which were really just offices of the central government. The

municipality

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the go ...

ordinance () was similar.

Lead-up to the 1848 Revolution

During the

Vormärz

' (; English: ''pre-March'') was a period in the history of Germany preceding the 1848 March Revolution in the states of the German Confederation. The beginning of the period is less well-defined. Some place the starting point directly after the ...

, the period leading up to the

German revolutions of 1848–1849

The German revolutions of 1848–1849 (), the opening phase of which was also called the March Revolution (), were initially part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many European countries. They were a series of loosely coordinated pro ...

, the importance of the constitutional question in Westphalia was not matched by interest in

German unification

The unification of Germany (, ) was the process of building the modern German nation state with federal features based on the concept of Lesser Germany (one without multinational Austria), which commenced on 18 August 1866 with adoption of t ...

, which was very low. The mayor of

Rhede

Rhede () is a municipality in the district of Borken in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located near the border with the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivis ...

in

Münsterland wrote in 1833, "The

Hambach Festival and

Burschenschaft

A Burschenschaft (; sometimes abbreviated in the German ''Burschenschaft'' jargon; plural: ) is one of the traditional (student associations) of Germany, Austria, and Chile (the latter due to German cultural influence).

Burschenschaften were fo ...

colours have no meaning to the peace-loving inhabitants of this land." Public feeling in

Sauerland and

Minden-Ravensberg

Minden-Ravensberg was a Prussian administrative unit consisting of the Principality of Minden and the County of Ravensberg from 1719–1807. The capital was Minden. In 1807 the region became part of the Kingdom of Westphalia, a client state ...

seemed similar. German nationalism only became a force in Westphalia in the 1840s. In many municipalities, singing clubs were formed, which nurtured national myths. Westphalian participation in the

Cologne Cathedral

Cologne Cathedral (german: Kölner Dom, officially ', English: Cathedral Church of Saint Peter) is a Catholic cathedral in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the administration of the Archdiocese o ...

construction festival and the gatherings in support of the

Hermannsdenkmal

The ''Hermannsdenkmal'' (German for "Hermann Monument") is a monument located southwest of Detmold in the district of Lippe (North Rhine-Westphalia), in Germany. It stands on the densely forested ', sometimes also called the ''Teutberg'' or ''Te ...

was considerable. A lively mass of associations and clubs developed.

In addition to the disappointment about the failure of the promised reforms to materialise, the arrest of

Archbishop of Cologne Clemens August Droste zu Vischering in 1837, during the "" led to a greater politicisation of Westphalian Catholicism. The liberal Catholic journalist, Johann Friedrich Joseph Sommer wrote "contemporary events, like those of the last ten years, have stirred up the docile Westphalian and have contributed no little degree to bring a kind of religious somnolence to an end." At the same time, Sommer saw the mass unrest in connection with the riots as a precursor of the revolutions of 1848. The "state must give way, for the first time, power quakes before the popular mood." In the 1830s and 1840s, the discussion circles of liberals, democrats, and even some socialists consolidated (e.g. the journal ').

In addition, the agrarian reforms which were negatively received by many rural groups, led to growing dissatisfaction. To this were added several bad harvests in the 1840s, which caused the price of food to rise notably, particularly in the cities. Traditional manufacturing also faced a stark structural crisis. A consequence of the difficult social situation was the high level of

emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanent ...

. Between 1845 and 1854, around 30,000 people left the province, most heading overseas. Almost half of these people came from the crisis-ridden linen-producing areas in the eastern part of Westphalia.

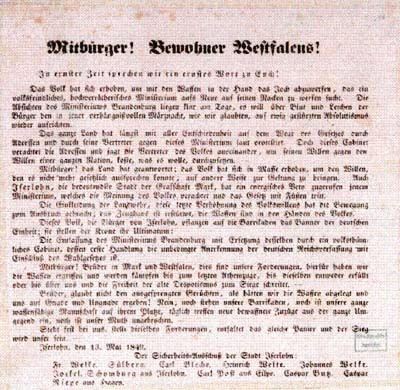

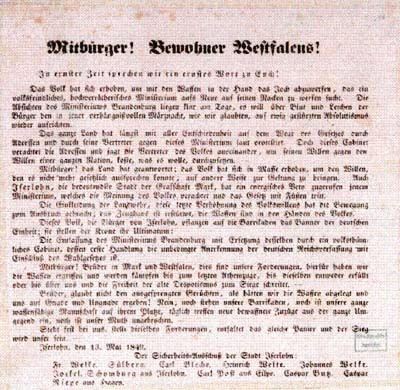

Revolution of 1848-1849 in Westphalia

In Westphalia, there were very diverse reactions to the outbreak of revolution in 1848. The democratic left of the "Rhede Circle" celebrated the coming of a new era in the , "The people of Europe, freed from the oppressive nightmare, have almost caught their breath." The journal ''Hermann'', published in

Hamm supported the introduction of a new

calendar era

A calendar era is the period of time elapsed since one '' epoch'' of a calendar and, if it exists, before the next one. For example, it is the year as per the Gregorian calendar, which numbers its years in the Western Christian era (the Copti ...

, on the model of the

French revolutionary calendar. The left also looked to France for their political programme and called for "Wealth, Education, and Freedom for all." There were also countervailing opinions, like that of

Bielfeld superintendent and later member of the

Prussian National Assembly

The Prussian National Assembly (German: ''Preußische Nationalversammlung''), came into being after the revolution of 1848 and was tasked with drawing up a constitution for Prussia. It first met in the building of the '' Sing-Akademie zu Berlin ...

, , who spoke of a "disgraceful event", in which the "simple

Philistine" expected "that a constitution would sweep all misery and inequality from the world." He feared instead the "collapse of all order" and general "disorder."

After news reached Westphalia of the

February Revolution in Paris and the

March Revolution in various parts of Germany, including

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

and

Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, rural uprisings broke out in parts of Westphalia, especially in the

Sauerland, the , and

Paderborn

Paderborn (; Westphalian: ''Patterbuorn'', also ''Paterboärn'') is a city in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader and ''Born'', an old German term for t ...

. Some of the buildings of the stewards of in

Olsberg were attacked and the documents inside were burnt, as people sung songs of freedom. Manors were attacked elsewhere, also, for example in

Dülmen

Dülmen () is a town in the district of Coesfeld, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Geography

Dülmen is situated in the south part of the Münsterland area, between the Lippe river to the south, the Baumberge hills to the north and the Ems ri ...

. This rural revolt was quickly defeated by the military. In the areas of Westphalia where

industrialisation was beginning to take hold, like the County of Mark, some factories were attacked. In the cities, there was talk of the appointment of a liberal government and the victory of the revolution was celebrated almost everywhere with parades and

black-red-gold flags. However, there was also an anti-revolutionary movement, especially in the old Prussian parts of the province. In the County of Mark, this centred around the industrialist

Friedrich Harkort

Friedrich Harkort (February 22, 1793, Hagen - March 6, 1880), known as the "Father of the Ruhr," was an early prominent German industrialist and pioneer of industrial development in the Ruhr region.(29 December 2009)Friedrich Harkort - Vorbild u ...

, who promoted his views in his famous (Workers' Letters).

In the elections to the

Prussian National Assembly

The Prussian National Assembly (German: ''Preußische Nationalversammlung''), came into being after the revolution of 1848 and was tasked with drawing up a constitution for Prussia. It first met in the building of the '' Sing-Akademie zu Berlin ...

and the

Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

, the political leanings of the candidates were not the decisive factor. Rather, their reputation among the people played a central role in their nomination. In Sauerland, therefore, the conservative

Joseph von Radowitz

Joseph Maria Ernst Christian Wilhelm von Radowitz (6 February 1797 – 25 December 1853) was a conservative Prussian statesman and general famous for his proposal to unify Germany under Prussian leadership by means of a negotiated agreemen ...

, the liberal /

ultramontanist

Ultramontanism is a clerical political conception within the Catholic Church that places strong emphasis on the prerogatives and powers of the Pope. It contrasts with Gallicanism, the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by th ...

Johann Friedrich Sommer, and the democrat were all elected. Leading Westphalians in the Prussian National Assembly included the democrats

Benedikt Waldeck and . In constitutional discussions in Berlin, Waldeck and Sommer played notable roles on the left and right respectively. In Frankfurt, Westphalia's representatives included

Georg von Vincke

Georg von Vincke (5 May 1811 – 3 June 1875) was a Prussian politician, officer, landowner and aristocrat of the Vincke family. As a political figure he was associated with the Old Liberals.

Biography

He was born in Hagen. He was the son of Ludw ...

, , and the later bishop

Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler

Baron Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler (25 December 181113 July 1877) was a German theologian and politician who served as Bishop of Mainz. His social teachings became influential during the papacy of Leo XIII and his encyclical ''Rerum novarum''. ...

.

In the province itself, political clubs and journals of every stripe were established. The spectrum ranged from Catholic and liberal pamphlets to

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

's radical '. The range of political opinions was as diverse as the media landscape. However, conservative groups generally included only protestant officers and officials of the central government. A notable exception was the conservative attitude of rural people in the

pietistic Lutheran milieu of Minden-Ravensberg. The vast majority of politically active bourgeoisie joined constitutional or democratic clubs. The liberals founded an

umbrella organisation

An umbrella organization is an association of (often related, industry-specific) institutions who work together formally to coordinate activities and/or pool resources. In business, political, and other environments, it provides resources and ofte ...

of constitutional societies in the provinces of Rhineland and Westphalia at a congress in

Dortmund in July 1848. In the district of Arnsberg alone, there were twenty-eight such societies by October. In the other two districts, the number of societies was clearly lower and in Münster the local association was split by internal conflicts. The democratic societies only managed to reach an agreement at a congress in September 1848. In Münster, the local democratic association had at least 350 members. The

labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

, in the form of the (''General German Workers' Brotherhood'') had very little representation in Westphalia, compared with the Rhineland. There was a strong labour association in Hamm, which played a leading role in the democratic camp and maintained contacts with the Arbeiterverbrüderung at the same time. In total, the number of democratic and republican associations remained substantially lower than the liberal ones. In the Catholic parts of Westphalia, the first organisations of political Catholicism also developed at this time. The

Pius Associations were established in many places, but were focused on the association in the provincial capital.

In petitions, workers' groups and community representatives called on their delegates to speak on behalf of their demands in the national assemblies. In the following months, the political excitement declined markedly. In Catholic areas, the election of

Archduke John of Austria as regent (''

Reichsverweser

A ''Reichsverweser'' (German pronunciation: ) or imperial regent represented a monarch when there was a vacancy in the throne, such as during a prolonged absence or in the period between the monarch's death and the accession of a successor. The t ...

'') of the new

German Empire by the Frankfurt Parliament was met with great enthusiasm and patriotic celebrations were held in

Winterberg and Münster, for example. However, the reaction to this election showed that the difference between Catholics and Protestants in Westphalia was as great as ever. In the old Prussian areas, the duty of establishing unity and freedom was seen as resting above all with Prussia, while in Catholic Westphalia, the establishment of the Frankfurt Parliament was seen as a step towards a united state under Catholic leadership. Thus, the conflict between supporters of the little or greater solutions to the

German question

The "German question" was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve a unification of all or most lands inhabited by Germans. From 1815 to 1866, about 37 independent German-speaking sta ...

intersected with religious affiliation.

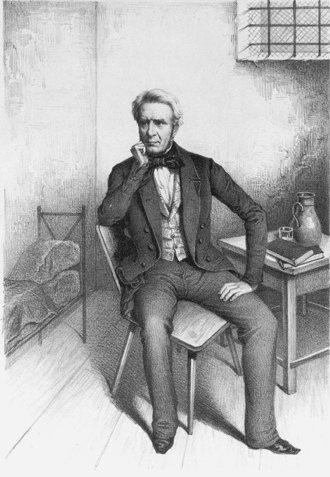

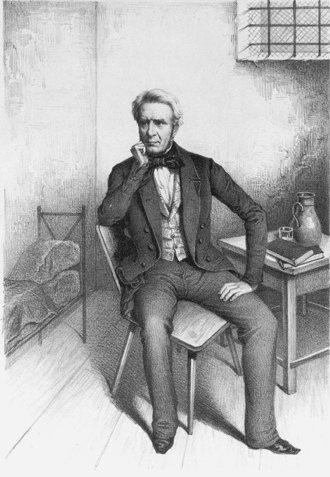

Only the beginning of the counter-revolution notably increased political excitement. In many parts of Westphalia, the power of the democrats increased, while the discontent of the people with hesitant liberals like Johan Sommer was palpable. In the face of the threat to the revolution's accomplishments, the democrats and constitutional rebels resolved to cooperate, culminating in the "Congress for the matter and rights of the Prussian National Assembly and of the Prussian People" in Münster in 1848. After the Prussian National Assembly was dissolved on 5 December 1848, democratic candidates like managed to win election to the

lower chamber

A lower house is one of two chambers of a bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has come to wield more power or oth ...

of the

Landtag of Prussia

The Landtag of Prussia (german: Preußischer Landtag) was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameral legislature consisting of the upper House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower House of Represent ...

. The end of the revolution in Westphalia came with the comprehensive defeat of the in June 1849. A few Westphalian revolutionaries, like Temme and Waldeck, were later subject to political prosecutions. By summer 1849, Westphalian democrats had already begun departing for

America.

Economy and society

Pre-industrial period

At the beginning of the 19th century, Westphalia was already a very economically and socially diverse region. Agriculture was dominant and in many places it was still practiced in very traditional and ineffective ways. In most areas, small and medium farms were most common. Only in the Münsterland and Paderborn regions were larger establishments widespread. These areas, as well as the

Soest Börde

The Soest Börde (german: Soester Börde) is an historical territorial lordship and a cultural landscape in the centre of the German region of Westphalia, between Sauerland in the south and Münsterland in the north. It is known nationally for b ...

, were especially suitable for agriculture. On the other hand, agriculture in Minden-Ravensberg and the southern

Bergisches Land

The Bergisches Land (, ''Berg Country'') is a low mountain range region within the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, east of Rhine river, south of the Ruhr. The landscape is shaped by woods, meadows, rivers and creeks and contains ...

was fairly unproductive. Even in the pre-industrial period, some agricultural products were exported. Westphalian ham was a known export commodity, for example.

Industrialisation encouraged the integration of agricultural activity with the new centres of industrial production. The increased demand led to an expansion of

pig farm

Pig farming or pork farming or hog farming is the raising and breeding of domestic pigs as livestock, and is a branch of animal husbandry. Pigs are farmed principally for food (e.g. pork: bacon, ham, gammon) and skins.

Pigs are amenable to ...

ing. Cereals produced in the province were an important raw material for the

brewing industry

Beer is one of the oldest and the most widely consumed type of alcoholic drink in the world, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches, mainly derived from cerea ...

that developed first in the

Ruhr and later elsewhere. In

Dortmund alone, there were more than eighty individual breweries. The huge market for agricultural goods in the nearby industrial areas meant that in the fertile parts of the province, agriculture was the dominant industry well into the twentieth century and that it remained a profitable economic sector everywhere.

In many places, yields at the beginning of the nineteenth century were insufficient to support the growing population. The number of poor and landless peasants grew. Many of them sought opportunities to work outside their home regions. Travelling merchants like the and the became a symbol of the region. In the northern part of the province, the

travelled to work in the Netherlands. from east Westphalia and the neighbouring

principality of Lippe also migrated to work. The , in which men would make

linen at home in winter and then travel to the Netherlands to sell it the following summer, developed from the Hollandgänger.

Within Westphalia, the low cost of labour enabled the expansion of pre-industrial manufacturing, which made products for export. In the "Northwest German linen belt," which stretched from western Münsterland, through

Tecklenburg

Tecklenburg () is a town in the district of Steinfurt, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Its name comes from the ruined castle around which it was built. The town is situated on the Hermannsweg hiking trail.

The coat of arms shows an anchor ...

,

Osnabrück

Osnabrück (; wep, Ossenbrügge; archaic ''Osnaburg'') is a city in the German state of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the river Hase in a valley penned between the Wiehen Hills and the northern tip of the Teutoburg Forest. With a population ...

, and Minden-Ravensberg, to modern

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony (german: Niedersachsen ; nds, Neddersassen; stq, Läichsaksen) is a German state (') in northwestern Germany. It is the second-largest state by land area, with , and fourth-largest in population (8 million in 2021) among the 16 ...

, household production developed into

proto-industrial levels. Especially in Minden-Ravensberg, pre-industrial linen production played an important role. The fabric was bought up and sold on by (transporters).

In southern Westphalia, there was a major

iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

extraction and processing region in

Siegerland, parts of the Duchy of Westphalia, and the Sauerland, which extended over the provincial borders to the

Bergisches Land

The Bergisches Land (, ''Berg Country'') is a low mountain range region within the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, east of Rhine river, south of the Ruhr. The landscape is shaped by woods, meadows, rivers and creeks and contains ...

and

Altenkirchen

Altenkirchen () is a town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, capital of the district of Altenkirchen. It is located approximately 40 km east of Bonn and 50 km north of Koblenz. Altenkirchen is the seat of the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' ("co ...

. The

iron ore extracted in and was

smelt

Smelt may refer to:

* Smelting, chemical process

* The common name of various fish:

** Smelt (fish), a family of small fish, Osmeridae

** Australian smelt in the family Retropinnidae and species ''Retropinna semoni''

** Big-scale sand smelt ''Ath ...

ed at places like

Wendener Hütte

Wendener Hütte is a retired Industrial Age ironworks and hammer mill located near Wenden, Germany. The complete site, supported and run by Museumsverein Wendener Hütte e.V., is open to visitors from April to October.

History

The birth of a ...

and made into finished products in the western part of the region (e.g.

wire drawing

Wire drawing is a metalworking process used to reduce the cross-section of a wire by pulling the wire through a single, or series of, drawing die(s). There are many applications for wire drawing, including electrical wiring, cables, tension-loa ...

in

Altena

Altena (; Westphalian: ''Altenoa'') is a town in the district of Märkischer Kreis, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. The town's castle is the origin for the later Dukes of Berg. Altena is situated on the Lenne river valley, in the northern stre ...

, Iserlohn, and

Lüdenscheid

Lüdenscheid () is a city in the Märkischer Kreis district, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located in the Sauerland region.

Geography

Lüdenscheid is located on the saddle of the watershed between the Lenne and Volme rivers which ...

, or at Iserlohn). These businesses were partially cooperative and organised into a network by

Reidemeisters. In the southern part of the Ruhr,

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

was exported for neighbouring regions from early times. in

Sprockhövel

Sprockhövel is a town in the district of Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Geography

Sprockhövel is located in the southern suburban part of the Ruhr area. It is 6 km southeast of Hattingen, 8 km northwest of Gevels ...

was active from the beginning of the 17th century, for example.

Industrialisation

At the start of the nineteenth century, parts of the province were the first areas to see the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

in Germany and in the it was among the economic hubs of the German Empire.

The end of Napoleon's

Continental System

The Continental Blockade (), or Continental System, was a large-scale embargo against British trade by Napoleon Bonaparte against the British Empire from 21 November 1806 until 11 April 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon issued the Berli ...

opened the region up to English industrial products. Household-based textile production in particular was not able to compete with this in the long term and eventually disappeared from the market. Conversion to industrial forms of production in and around

Bielefeld

Bielefeld () is a city in the Ostwestfalen-Lippe Region in the north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population of 341,755, it is also the most populous city in the administrative region (''Regierungsbezirk'') of Detmold and the ...

enabled a transition to the new circumstances. The , founded in 1854 by , was the largest

flax mill

Flax mills are mills which process flax. The earliest mills were developed for spinning yarn for the linen industry.

John Kendrew (an optician) and Thomas Porthouse (a clockmaker), both of Darlington developed the process from Richard Ar ...

in Europe. In 1862, the "Bielfeld Action Society for Mechanical Weaving" () was established. The success of textile enterprises was subsequently a basis for the establishment of iron and metalworking industries in the region. However, the new mechanised industry could not employ the available workforce like the old cottage industry. In the linen-producing areas of Westphalia, poverty and overseas emigration from rural areas rose sharply in the 1830s and 1840s.

In the ironworking and metalworking areas in southwestern Westphalia, industrial competition from overseas initially had only negative consequences. Some pre-industrial enterprises, like

sheet metal

Sheet metal is metal formed into thin, flat pieces, usually by an industrial process. Sheet metal is one of the fundamental forms used in metalworking, and it can be cut and bent into a variety of shapes.

Thicknesses can vary significantly; ex ...

production in and around

Olpe, disappeared. More devastating for the old village

smithies and cottage metalworking enterprises was the establishment of a modern metalworking industry in Westphalia itself, based on

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

from the Ruhr. Decisive for the development of the was the invention of

longwall mining, which allowed the removal of the ore without stripping off the surface layer. This was employed for the first time in 1837 in the Ruhr region near

Essen. In Westphalia, the first

shaft mine

Shaft mining or shaft sinking is the action of excavating a mine shaft from the top down, where there is initially no access to the bottom. Shallow shafts, typically sunk for civil engineering projects, differ greatly in execution method from ...

was in

Bochum, opened in 1841.

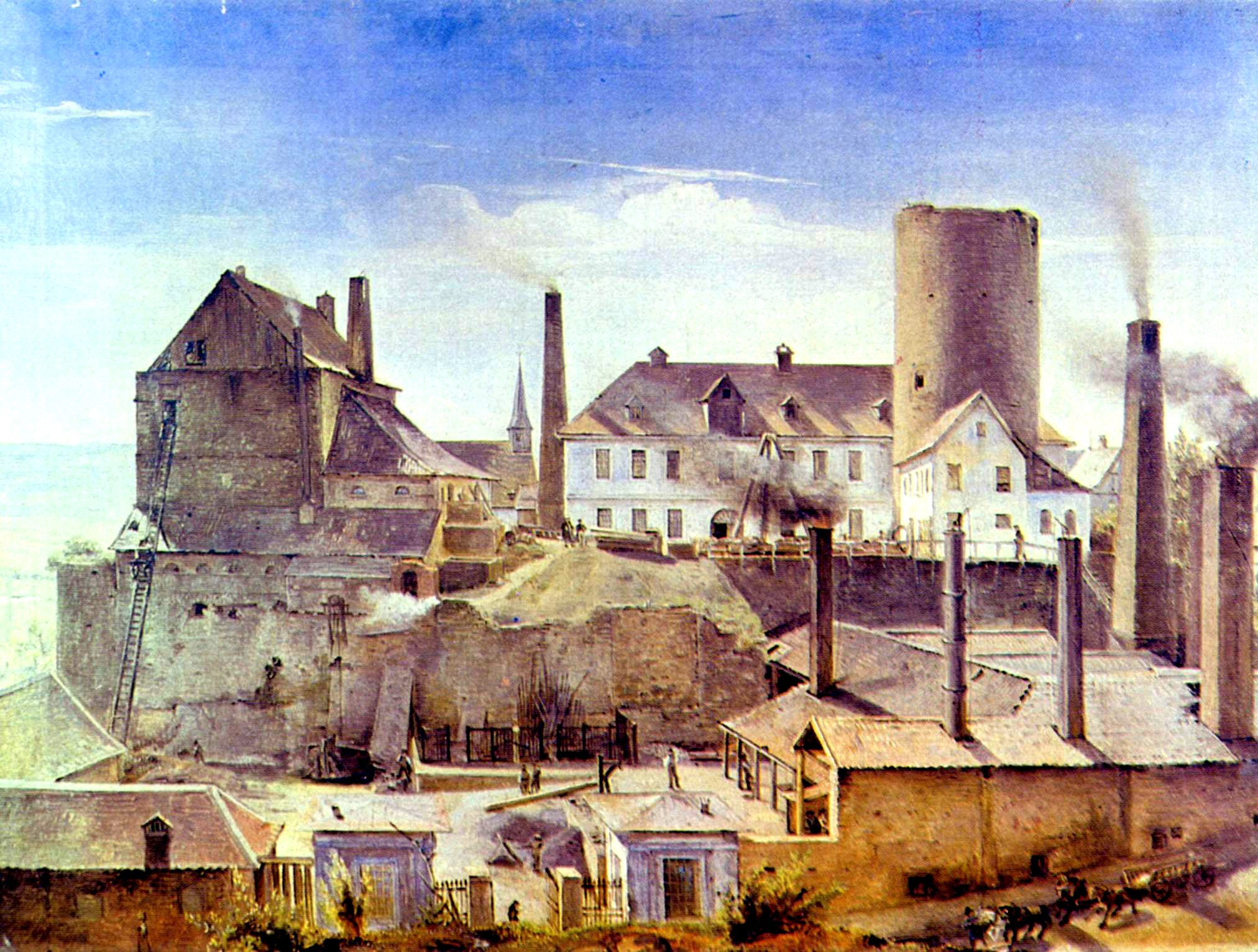

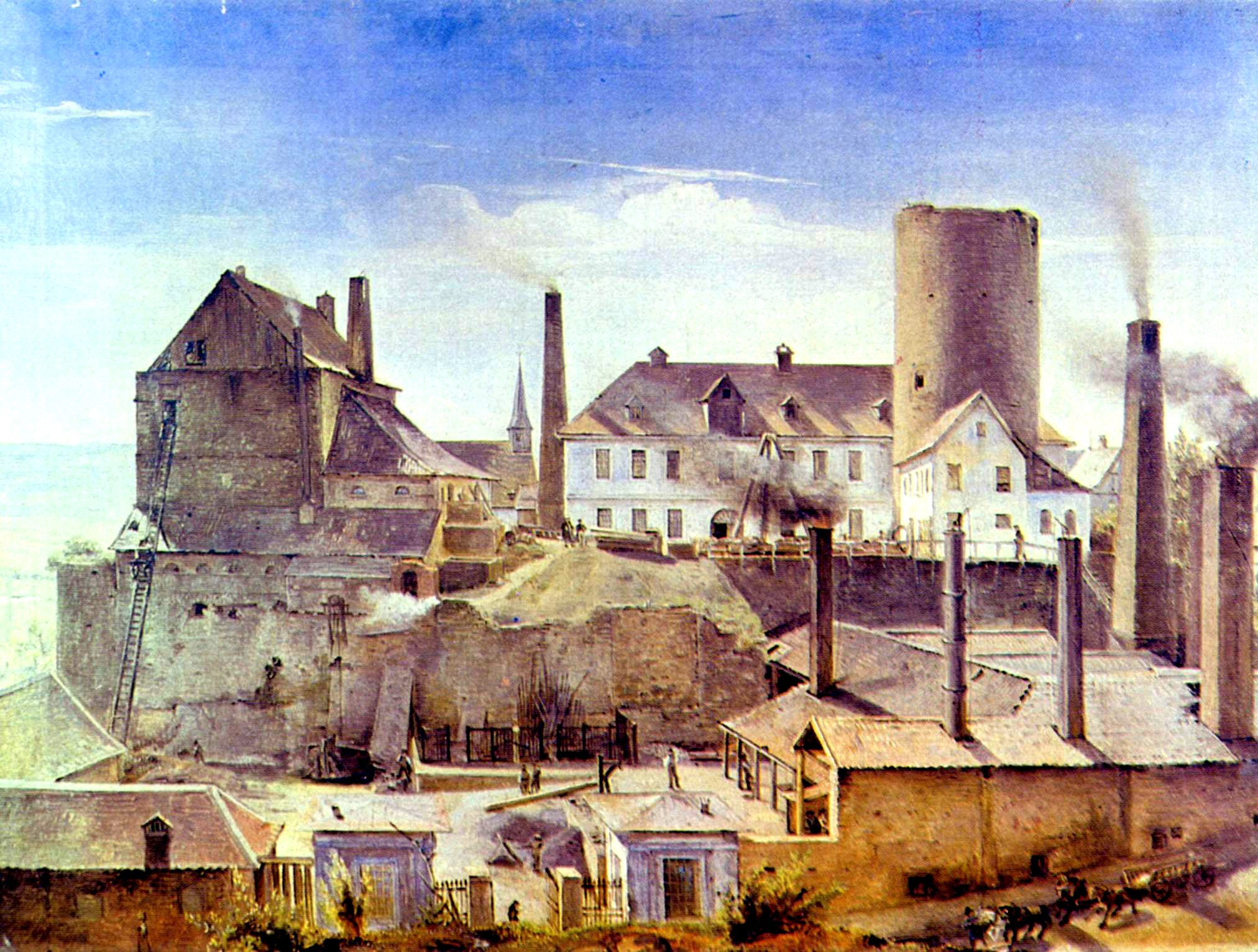

In 1818,

Friedrich Harkort

Friedrich Harkort (February 22, 1793, Hagen - March 6, 1880), known as the "Father of the Ruhr," was an early prominent German industrialist and pioneer of industrial development in the Ruhr region.(29 December 2009)Friedrich Harkort - Vorbild u ...

and established , a mechanised ironworks, in

Wetter and in 1826 in the same place they established the first

puddling furnace in Westphalia. Later, the works were relocated to

Dortmund where they developed into

Rothe Erde

Rothe Erde is a district of Aachen, Germany with large-scale development in heavy industry. It is sub-district 34 of the Aachen-Mitte Stadtbezirk (which is roughly equivalent to a city borough). It lies between the districts of Forst and Eilen ...

. Further ironworks were established in

Hüsten (),

Warstein

Warstein () is a municipality with town status in the district of Soest, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located at the north end of Sauerland.

Geography

Warstein is located north of the Arnsberger Wald (forest) at a brook called Wäs ...

,

Lünen

Lünen is a town in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located north of Dortmund, on both banks of the River Lippe. It is the largest town of the Unna district and part of the Ruhr Area.

In 2009 a biogas plant was built to provide elect ...

(

Westfalia Hütte),

Hörde

Hörde is a ''Stadtbezirk'' ("City District") and also a ''Stadtteil'' ('' Quarter'') in the south of the city of Dortmund, in Germany.

Hörde is situated at 51°29' North, 7°30' West, and is at an elevation of 112 metres above mean sea level. ...

(),

Haspe (), Bochum (), and other places. These new coal-powered ironworks were far more productive than their

charcoal-based pre-industrial equivalents.

A precondition for industrial development was the expansion of transport infrastructure. From the end of the 18th century, rural highways () began to be constructed, rivers in the lower part of the Ruhr were made navigable for ship traffic, and canals were built. Most of all,

railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s were the motor of industrial development. In 1847, the

Cologne-Minden Railway Company

The Cologne-Minden Railway Company (German, old spelling: ''Cöln-Mindener Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft'', ''CME'') was along with the Bergisch-Märkische Railway Company and the Rhenish Railway Company one of the railway companies that in the mid-19th ...

completed a west-east branch line from the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

to the

Weser

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports o ...

. The

Bergisch-Markisch Railway Company

The Bergisch-Markisch Railway Company (german: Bergisch-Märkische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft, BME), also referred to as the Berg-Mark Railway Company or, more rarely, as the Bergisch-Markische Railway Company, was a German railway company that togeth ...

's

Elberfeld–Dortmund railway

The Elberfeld–Dortmund railway is a major railway in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It is part of a major axis for long distance and regional rail services between Wuppertal and Cologne, and is served by Intercity Express, InterCit ...

followed in 1849 and the

Royal Westphalian Railway Company

The Royal Westphalian Railway (german: Königlich-Westfälische Eisenbahn, KWE) was a German rail company established in 1848 with funding from the Prussian government, which later became part of the Prussian State Railways. The network eventuall ...

was established in the same year.

Regions like Sauerland, which were only connected to the railway network in the 1860s or 1870s, remained economically marginal even in this age of economic growth. Some parts of these regions experienced a marked process of

deindustrialisation. Instead, in many places,

forestry

Forestry is the science and craft of creating, managing, planting, using, conserving and repairing forests, woodlands, and associated resources for human and environmental benefits. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands. ...

took over, from that point on practiced in a sustainable manner. Only a few places, like

Schmallenberg with its concentration on , saw new industrial developments. The expansion of also slowed.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the coal mining industry in the Ruhr grew ever stronger. In the 1850s, Hermannshütte, Rothe Erde, , , and in

Hattingen

Hattingen is a town in the northern part of the Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis district, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

History

Hattingen is located on the south bank of the River Ruhr in the south of the Ruhr region. The town was first mentioned in 1 ...

were established. As a result, some of the pre-industrial areas in Westphalia became marginal and were only able to succeed by concentrating on particular products (e.g. lead production in ). Even more new pit mines and mining companies were established in the Ruhr region in the following years, such as the . Moreover, older factories grew into massive enterprises with several thousand employees. By the middle of the nineteenth century at the latest, the Westphalian portion of the Ruhr was clearly the economic centre of the province.

Population growth and social change

The developing industry initially pulled numerous jobseekers mostly from the agriculturally and economically stagnant parts of the province. From around the 1870s, the supply of workers within Westphalia was exhausted and companies increasingly drew workers in from the

eastern provinces of Prussia and beyond. The large number of

Polish-speaking workers established their own societies,

labour union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

s and pastoral care organisations, which operated in their own language. A particular population profile developed in the mining districts, which differed from the rest of Westphalia in some respects, such as dialect (

Ruhrdeutsch). In 1871, the province of Westphalia had 1.78 million inhabitants, around 14% more than in 1858. By 1882, the population had grown more than 20% and the growth from then to 1895 was similarly high. In the ten years between 1895 and 1905, the population grew by more than 30%, surpassing 3.6 million. The highest growth took place in Arnsberg district, the centre of Westphalian industry. Between 1818 and 1905, the population of Münster and Minden districts grew by slightly more than 100%, but that of Arnsberg grew by over 400%.

In all the industrialised areas of Westphalia, but especially in the Ruhr, the social consequences of industrialisation were substantial. In these areas, the working class became the largest social group by some margin. Immigration meant that the population growth over time was erratic. The supply of housing was insufficient and, in the Ruhr,

lodgers and (people who rented a room for only a couple of hours a day) were common. Corporations sought to plug this gap to some extent with company housing or workers' settlements. The ulterior motive for this was the creation of a workforce that was loyal to the corporation and would not engage with the

labour movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

.

The population growth led to the development of a number of towns and villages into large cities. While some cities, like Dortmund and Bochum, had a long civic heritage to look back on, places like

Gelsenkirchen and

Recklinghausen grew from small villages to major centres in a matter of decades. Other settlements that became major industrial cities included

Witten

Witten () is a city with almost 100,000 inhabitants in the Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis (district) in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Geography

Witten is situated in the Ruhr valley, in the southern Ruhr area.

Bordering municipalities

* Bochum

* Dortmun ...

,

Hamm,

Iserlohn

Iserlohn (; Westphalian: ''Iserlaun'') is a city in the Märkischer Kreis district, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is the largest city by population and area within the district and the Sauerland region.

Geography

Iserlohn is locat ...

,

Lüdenscheid

Lüdenscheid () is a city in the Märkischer Kreis district, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located in the Sauerland region.

Geography

Lüdenscheid is located on the saddle of the watershed between the Lenne and Volme rivers which ...

, and

Hagen (now on the edge of the mining area), as well as

Bielefeld

Bielefeld () is a city in the Ostwestfalen-Lippe Region in the north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population of 341,755, it is also the most populous city in the administrative region (''Regierungsbezirk'') of Detmold and the ...

.

Urban life

A characteristic of the rapidly growing industrial cities was the general absence of the bourgeoisie. The middle class was notably weak. The cities concentrated at first on the most essential infrastructure, like supply routes, rubbish collection, public transport, schools, etc. Improved hygiene conditions brought the death rate down markedly, especially among children. Epidemics like

cholera ceased to play a significant role. On the other hand, the limits of these positive developments are clear from the continued prevalence of

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

, work-related illnesses like

silicosis, and the general strain on the environment from mining and industry.

The new industrial cities only acquired cultural infrastructure, like museums and theatres later on. These were concentrated in the old cities, which had a civic tradition, and did not appear in the newly formed industrial centres until well into the twentieth century. There was little provision for

higher education

Higher education is tertiary education leading to award of an academic degree. Higher education, also called post-secondary education, third-level or tertiary education, is an optional final stage of formal learning that occurs after comple ...

. Although the universities of

Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

and

Paderborn

Paderborn (; Westphalian: ''Patterbuorn'', also ''Paterboärn'') is a city in eastern North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, capital of the Paderborn district. The name of the city derives from the river Pader and ''Born'', an old German term for t ...

were established in the 18th century, these were reduced to "rump universities" with only a limited offering of courses at the beginning of Prussian rule. Münster was only promoted to full university status in 1902. The establishment of higher education in the Ruhr area only really began during the expansion of higher education in the 1960s.

Social disruption and unionisation

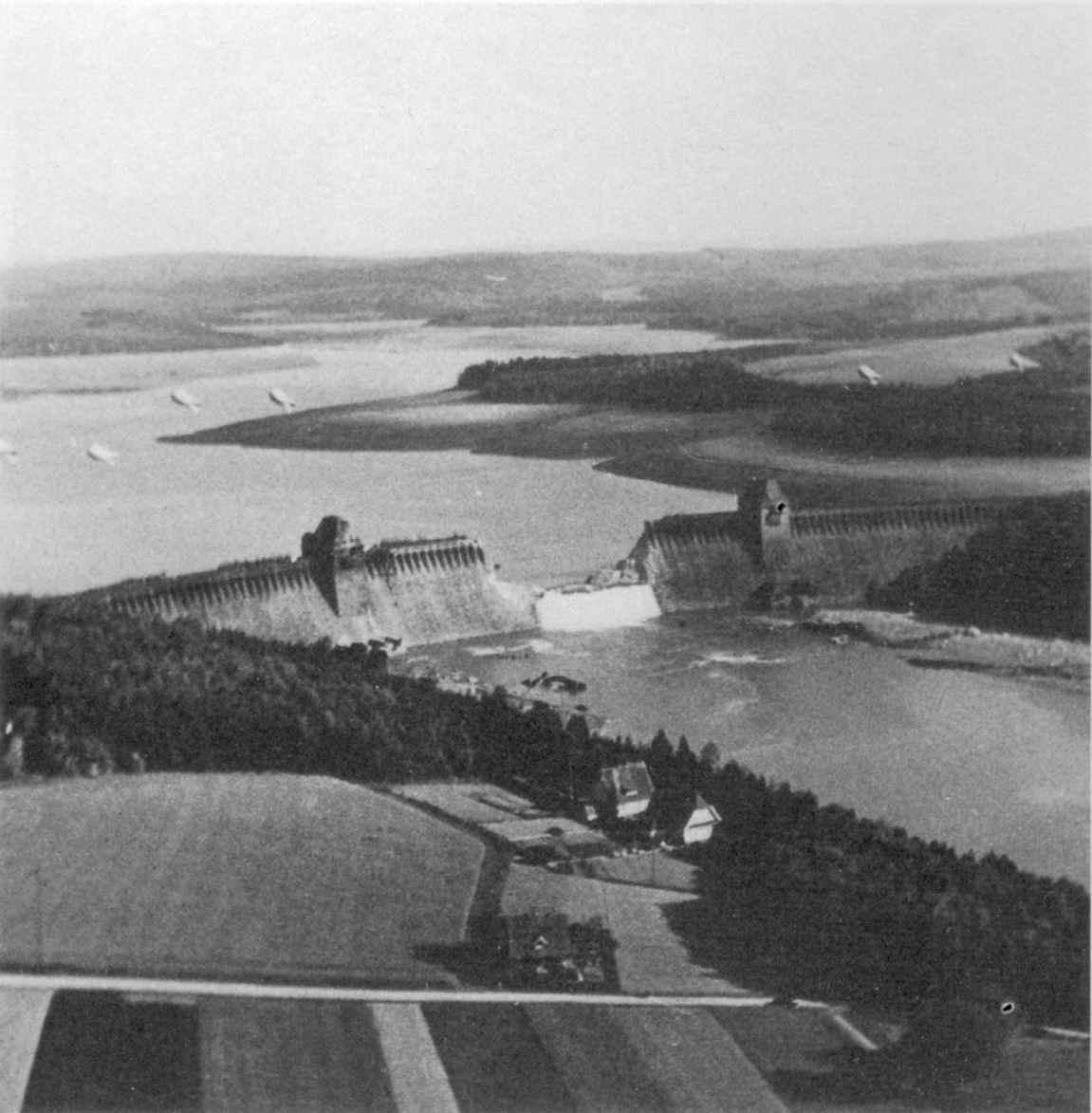

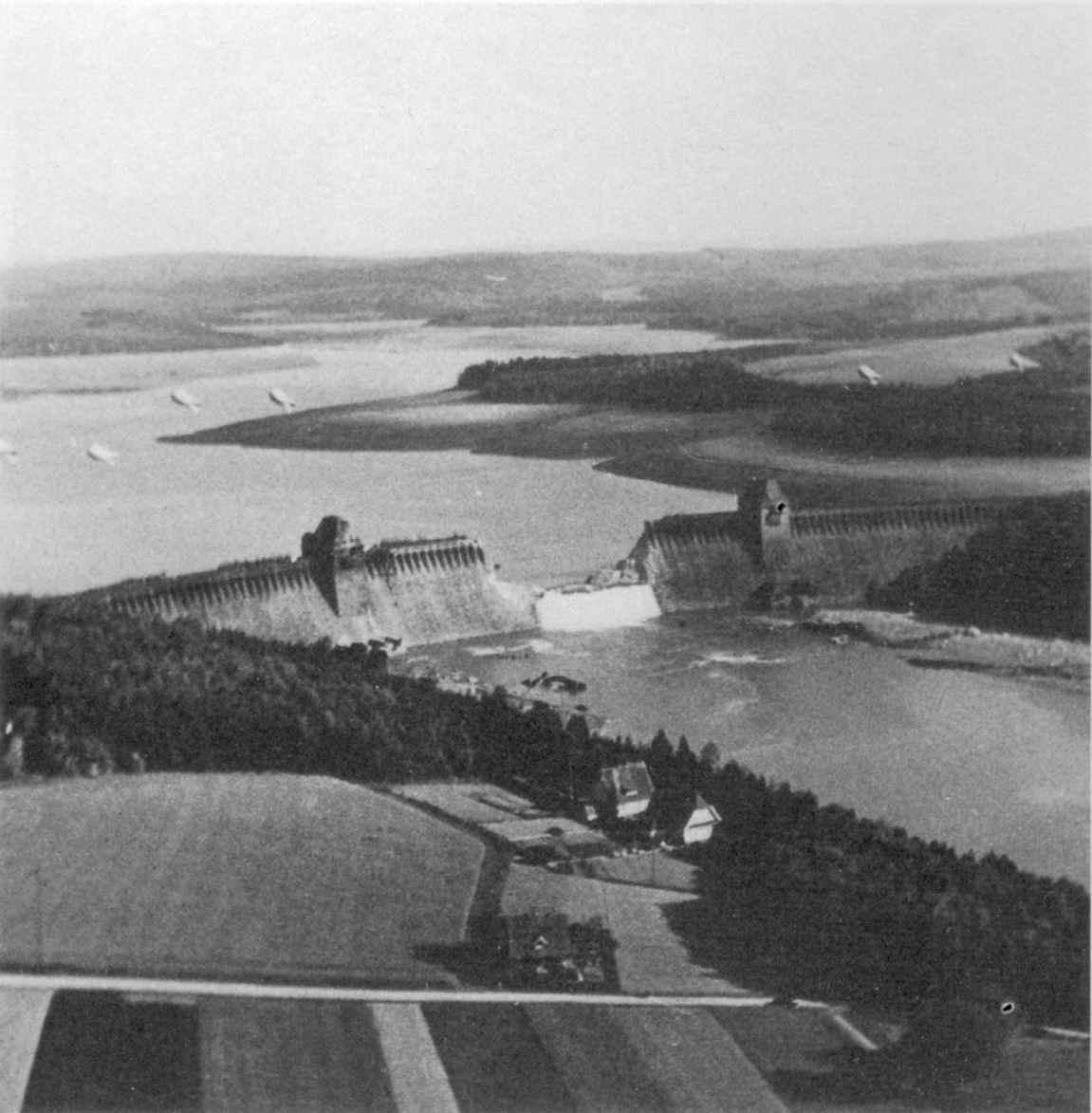

The rapid expansion of mining and industry in the

Ruhr region in the context of the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

led to a drastic transformation of the province's society and economy and massive population growth. With the introduction of the General

Mining Act The main purpose of mining acts (german: Berggesetze) in law is to govern the structure of mining authorities and their responsibilities, the entitlement to mining and the oversight of safety in and around the mines. With the introduction of parliam ...

in 1865, the privileges of the "Bergknappen" ("ordinary miners") came to an end, and thereafter miners did not differ from other workers in their employment rights. Initially, they reacted to falling wages, extended hours and other issues as normal, with – generally unsuccessful – petitions to government administration. Increasingly, they began to adopt the forms of action used by other groups of workers. The first took place in 1872. It was local, limited, and unsuccessful.

In 1889, the pent-up anger of the previous decades was unleashed in , in which roughly 90% of the 104,000 miners then working in the region participated. The strike began in

Bochum on 24 April and

Essen on 1 May. They were joined spontaneously by numerous other workers. A central strike committee was formed. The workers sought higher wages, the introduction of an

eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

, and various other changes. That the miners' old loyalty to authority had not been forgotten is shown by the fact that the strike committee sent a deputation to

Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

. Although he criticised the strike, he agreed to launch an official investigation of the strikes. Since the indicated a willingness to make concessions, the strike gradually petered out.

The strike in the Westphalian and Rheinish coal mining areas provided a model for miners in Sauerland, the , and even in

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

in the same year. Moreover, the strike had clearly shown that organisation was necessary to advocate for workers' interests. On 18 August 1889, what which would later be known as the "Alte Verband" ("Old Union") was established in Dotmund-

Dorstfeld. The Christian Miners' Union was founded in 1894 and a Polish Union in 1902. The began attempts at organisation in the 1880s, but remained insignificant. With respect to unionisation, the miners also provided a model for other groups of workers.

In 1905, broke out in the Bochum region, which grew into a

general strike of all mining unions. In total, around 78% of miners in the region participated in the strike. Although it eventually had to break up, it had indirect success, since the Prussian government met many of the workers' demands through revisions to the General Mining Act. In 1912, the Alte Verband, Polish Union and the Hirsch-Dunckersche Union joined together in a , although the Christian Miners' Union refused to lend its support. As a result, strike participation reached only about 60%. The strike was prosecuted with great bitterness and violent riots led the police and military to intervene in the end. The strike eventually broke up without success.

Alongside the miners, Westphalian workers in other areas also participated in the labour movement. In the metal industry, these actions were focused on small and medium-sized enterprises and the labour movement was not able to establish a toehold in the larger companies for various reasons. In particular, employers in the iron and steel industry defended their "Lord-of-the-Manor position" by firing workers as necessary. This was enabled by the starkly differentiated internal structure of these companies, which militated against the establishment of a sense of common purpose like that of the miners.

Political culture

The political culture of Westphalia, reflected above all in the long-term shifts in electoral results, was closely linked to the religious and social structure of the province, but also to the political debates of the first half of the nineteenth century. In particular, religion played a central role in Westphalia. As in the rest of Germany this led to the formation of Catholic and

social democrat

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soc ...

ic milieus, which heavily shaped the lives of their members "from the cradle to the grave." This tendency was less marked among the

liberals and

conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

. On 1 August 1886, the

districts and cities of Westphalia formed a ("provincial union"), a body whose members henceforth met as the Westphalian provincial Landtag. Henceforth, the Landtag consisted of the representatives of the districts and cities, elected by means of the

Prussian three-class franchise

The Prussian three-class franchise (German: ''Preußisches Dreiklassenwahlrecht'') was an indirect electoral system used from 1848 until 1918 in the Kingdom of Prussia and for shorter periods in other German states. Voters were grouped by distric ...

. The Landtag elected a

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, ...

for the province, known as the Landeshauptman or "Headman of the State" (Landesdirektor before 1889).

Centre Party

Especially following the

Kulturkampf, the

Centre Party (''Zentrum''), based on the traditional patterns from the early nineteenth century and the Revolution of 1848, largely monopolised politics in the Catholic parts of the province. The party was focussed on religious confession and was supported regardless of social class by Catholic workers, farmers, bourgeoisie, and nobility. Westphalia was the party's heartland. The party grew out of a meeting of politicians in

Soest in the 1860s, to discuss the foundation of a Catholic political party. The 1870

Soest Programme was one of the founding documents of the party.

Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler

Baron Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler (25 December 181113 July 1877) was a German theologian and politician who served as Bishop of Mainz. His social teachings became influential during the papacy of Leo XIII and his encyclical ''Rerum novarum''. ...

and

Hermann von Mallinckrodt Hermann von Mallinckrodt (5 February 1821, Minden – 26 May 1874) was a German parliamentarian from the Province of Westphalia.

His father, Detmar von Mallinckrodt, was vice-governor at Minden (1818–23) and also at Aachen (1823–29); and wa ...

were among the leading politicians in the establishment of the party who came from the province of Westphalia.

From the 1890s, social differences led to a clear regional differentiation within the party. In the predominantly rural areas, the Centre Party was usually rather conservative and the ("Westphalian Farmer's Association") had an influential role. The Association primarily represented small- and medium-scale farmers; the landed nobility remained influential well into the Weimar Republic and could take care of themselves politically. In the Münster-Coesfeld electorate, someone like

Georg von Hertling

Georg Friedrich Karl Freiherr von Hertling, from 1914 Count von Hertling, (31 August 1843 – 4 January 1919) was a German politician of the Catholic Centre Party. He was foreign minister and minister president of Bavaria, then chancellor of t ...

(later Minister-President of Bavaria and Imperial Chancellor) stood as a candidate from 1903 to 1912. Similarly, the later Chancellor

Franz von Papen, who belonged to the far right wing of the party, came from rural

Werl

Werl (; Westphalian: ''Wiärl'') is a town located in the district of Soest in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

Geography

Werl is easily accessible because it is located between the Sauerland, Münsterland, and the Ruhr Area. The Hellweg road ...

and had his political base in Münsterland.

On the other hand, in the industrialised parts of the province, social Catholicism was very strong. This current was particularly strong in the Ruhr and in Sauerland. The

Christian unions there were mostly stronger than their social-democratic competitors. Westphalian Catholics like

August Pieper and , who were both leaders of the

People's Association for Catholic Germany, were prominent individuals who were engaged in social politics.

Alongside increasing secularisation, the social focus of political Catholicism was a reason why the Centre Party lost support in middle-class areas during the Weimar Republic. In Sauerland, the party's support in 1933 had fallen to around 20% of what it had been in 1919. Nevertheless, in Catholic areas it generally remained the leading political force and remained the leading party in both of the province's electorates in the

1930 German federal election

Federal elections were held in Germany on 14 September 1930.Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p762 Despite losing ten seats, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) remained the largest party ...

.

Social democrats and communists

The Centre Party's dominance in Westphalia meant that liberal, conservative, and social democratic movements were restricted to Protestant Westphalia. Thus, leading early social democrats, like

Carl Wilhelm Tölcke and

Wilhelm Hasenclever, came from Catholic Sauerland, but began their careers in the neighbouring Protestant areas.

The County of Mark and the area around Bielfeld were early hotbeds of

social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

. In Mark,

Ferdinand Lassalle's

General German Workers' Association

The General German Workers' Association (german: Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein, ADAV) was a German political party founded on 23 May 1863 in Leipzig, Kingdom of Saxony by Ferdinand Lassalle. It was the first organized mass working-class ...

(ADAV) and its successors were strong from its foundation in 1863. Above all, Tölcke was responsible for the establishment of local branches of the party in Iserlohn, Hagen,

Gelsenkirchen, Bochum, Minden and

Oeynhausen by 1875. The ADAV merged with the

Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands, SDAP) was a Marxist socialist political party in the North German Confederation during unification.

Founded in Eisenach in 1869, the SDAP e ...

(SDAP) in 1875 to form the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SAP), which was later redubbed the

Social Democratic Party of Germany (SDP). After this, Tölcke ran as the party's main candidate in Westphalia. In Bielefeld, personalities like

Carl Severing

Carl Wilhelm Severing (1 June 1875, Herford, Westphalia – 23 July 1952, Bielefeld) was a German Social Democrat politician during the Weimar era.

He was seen as a representative of the right wing of the party. Over the years, he took a leadi ...

had a substantial impact on political life from the Empire until the early years of the

Federal Republic of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

.

Before 1933, the Westphalian portion of the Ruhr was in no way a "heartland" of the SPD. Although the social democratic "Old Union" was the first workers' union, it was weaker than the Christian unions by the turn of the century, and was subsequently also challenged by a significant Polish workers' association. Only in Protestant parts of the coalfields, like Dortmund, was the SPD able to achieve significant power in the period before World War I. The mining workers' leaders, and

Fritz Husemann were among the leading social democrats in the Ruhr.

In the Ruhr, the SPD was even more directly affected by the crises of the Weimar Republic than the Centre Party. Disenchantment with the party's approach to the