In physics,

In physics,  A physical wave field (physics), field is almost always confined to some finite region of space, called its ''domain''. For example, the seismic waves generated by earthquakes are significant only in the interior and surface of the planet, so they can be ignored outside it. However, waves with infinite domain, that extend over the whole space, are commonly studied in mathematics, and are very valuable tools for understanding physical waves in finite domains.

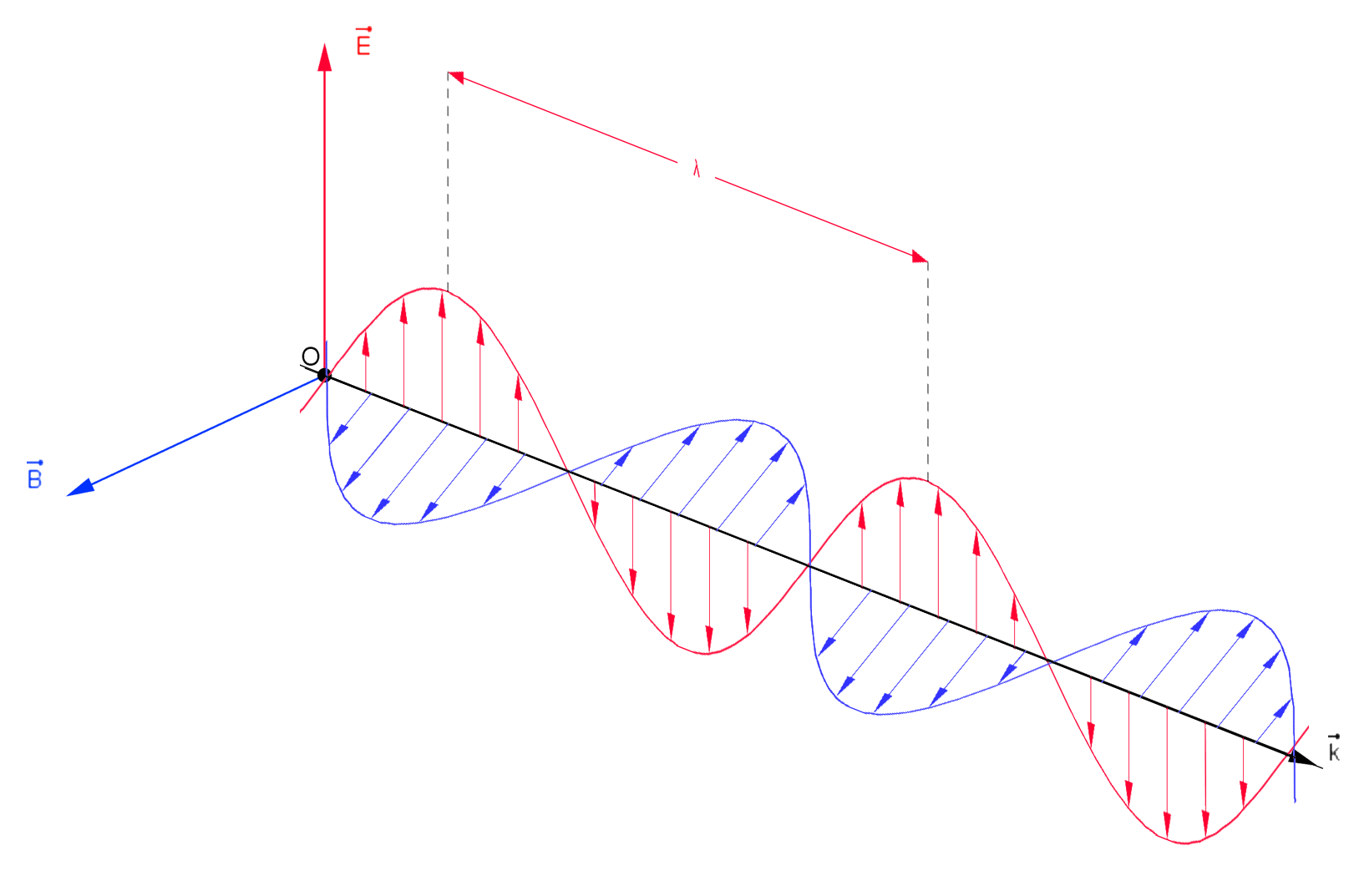

A ''plane wave'' is an important mathematical idealization where the disturbance is identical along any (infinite) plane Normal (geometry), normal to a specific direction of travel. Mathematically, the simplest wave is a ''sinusoidal plane wave'' in which at any point the field experiences simple harmonic motion at one frequency. In linear media, complicated waves can generally be decomposed as the sum of many sinusoidal plane waves having Angular spectrum method, different directions of propagation and/or Fourier transform, different frequencies. A plane wave is classified as a ''transverse wave'' if the field disturbance at each point is described by a vector perpendicular to the direction of propagation (also the direction of energy transfer); or ''longitudinal wave'' if those vectors are aligned with the propagation direction. Mechanical waves include both transverse and longitudinal waves; on the other hand electromagnetic plane waves are strictly transverse while sound waves in fluids (such as air) can only be longitudinal. That physical direction of an oscillating field relative to the propagation direction is also referred to as the wave's ''polarization (waves), polarization'', which can be an important attribute.

A physical wave field (physics), field is almost always confined to some finite region of space, called its ''domain''. For example, the seismic waves generated by earthquakes are significant only in the interior and surface of the planet, so they can be ignored outside it. However, waves with infinite domain, that extend over the whole space, are commonly studied in mathematics, and are very valuable tools for understanding physical waves in finite domains.

A ''plane wave'' is an important mathematical idealization where the disturbance is identical along any (infinite) plane Normal (geometry), normal to a specific direction of travel. Mathematically, the simplest wave is a ''sinusoidal plane wave'' in which at any point the field experiences simple harmonic motion at one frequency. In linear media, complicated waves can generally be decomposed as the sum of many sinusoidal plane waves having Angular spectrum method, different directions of propagation and/or Fourier transform, different frequencies. A plane wave is classified as a ''transverse wave'' if the field disturbance at each point is described by a vector perpendicular to the direction of propagation (also the direction of energy transfer); or ''longitudinal wave'' if those vectors are aligned with the propagation direction. Mechanical waves include both transverse and longitudinal waves; on the other hand electromagnetic plane waves are strictly transverse while sound waves in fluids (such as air) can only be longitudinal. That physical direction of an oscillating field relative to the propagation direction is also referred to as the wave's ''polarization (waves), polarization'', which can be an important attribute.

Mathematical description

Single waves

A wave can be described just like a field, namely as a function (mathematics), function where is a position and is a time. The value of is a point of space, specifically in the region where the wave is defined. In mathematical terms, it is usually a vector (mathematics), vector in the analytic geometry, Cartesian three-dimensional space . However, in many cases one can ignore one dimension, and let be a point of the Cartesian plane . This is the case, for example, when studying vibrations of a drum skin. One may even restrict to a point of the Cartesian line — that is, the set of real numbers. This is the case, for example, when studying vibrations in a string (music), violin string or recorder (musical instrument), recorder. The time , on the other hand, is always assumed to be a scalar (physics), scalar; that is, a real number. The value of can be any physical quantity of interest assigned to the point that may vary with time. For example, if represents the vibrations inside an elastic solid, the value of is usually a vector that gives the current displacement from of the material particles that would be at the point in the absence of vibration. For an electromagnetic wave, the value of can be the electric field vector , or the magnetic field vector , or any related quantity, such as the Poynting vector . In fluid dynamics, the value of could be the velocity vector of the fluid at the point , or any scalar property like pressure, temperature, or density. In a chemical reaction, could be the concentration of some substance in the neighborhood of point of the reaction medium. For any dimension (1, 2, or 3), the wave's domain is then a subset of , such that the function value is defined for any point in . For example, when describing the motion of a drumhead, drum skin, one can consider to be a disk (mathematics), disk (circle) on the plane with center at the origin , and let be the vertical displacement of the skin at the point of and at time .Wave families

Sometimes one is interested in a single specific wave. More often, however, one needs to understand large set of possible waves; like all the ways that a drum skin can vibrate after being struck once with a drum stick, or all the possible radar echos one could get from an airplane that may be approaching an airport. In some of those situations, one may describe such a family of waves by a function that depends on certain parameters , besides and . Then one can obtain different waves — that is, different functions of and — by choosing different values for those parameters. For example, the sound pressure inside a recorder (musical instrument), recorder that is playing a "pure" note is typically a

For example, the sound pressure inside a recorder (musical instrument), recorder that is playing a "pure" note is typically a Differential wave equations

Another way to describe and study a family of waves is to give a mathematical equation that, instead of explicitly giving the value of , only constrains how those values can change with time. Then the family of waves in question consists of all functions that satisfy those constraints — that is, all solution (mathematics), solutions of the equation. This approach is extremely important in physics, because the constraints usually are a consequence of the physical processes that cause the wave to evolve. For example, if is the temperature inside a block of some homogeneous and isotropic solid material, its evolution is constrained by the partial differential equation : where is the heat that is being generated per unit of volume and time in the neighborhood of at time (for example, by chemical reactions happening there); are the Cartesian coordinates of the point ; is the (first) derivative of with respect to ; and is the second derivative of relative to . (The symbol "" is meant to signify that, in the derivative with respect to some variable, all other variables must be considered fixed.) This equation can be derived from the laws of physics that govern the heat diffusion, diffusion of heat in solid media. For that reason, it is called the heat equation in mathematics, even though it applies to many other physical quantities besides temperatures. For another example, we can describe all possible sounds echoing within a container of gas by a function that gives the pressure at a point and time within that container. If the gas was initially at uniform temperature and composition, the evolution of is constrained by the formula : Here is some extra compression force that is being applied to the gas near by some external process, such as a loudspeaker or piston right next to . This same differential equation describes the behavior of mechanical vibrations and electromagnetic fields in a homogeneous isotropic non-conducting solid. Note that this equation differs from that of heat flow only in that the left-hand side is , the second derivative of with respect to time, rather than the first derivative . Yet this small change makes a huge difference on the set of solutions . This differential equation is called "the" wave equation in mathematics, even though it describes only one very special kind of waves.Wave in elastic medium

Consider a traveling transverse wave (which may be a pulse (physics), pulse) on a string (the medium). Consider the string to have a single spatial dimension. Consider this wave as traveling * in the direction in space. For example, let the positive direction be to the right, and the negative direction be to the left.

* with constant amplitude

* with constant velocity , where is

** independent of wavelength (no dispersion relation, dispersion)

** independent of amplitude (linear media, not nonlinear).

* with constant waveform, or shape

This wave can then be described by the two-dimensional functions

: (waveform traveling to the right)

: (waveform traveling to the left)

or, more generally, by d'Alembert's formula:

:

representing two component waveforms and traveling through the medium in opposite directions. A generalized representation of this wave can be obtained as the partial differential equation

:

General solutions are based upon Duhamel's principle.

Beside the second order wave equations that are describing a standing wave field, the one-way wave equation describes the propagation of single wave in a defined direction.

* in the direction in space. For example, let the positive direction be to the right, and the negative direction be to the left.

* with constant amplitude

* with constant velocity , where is

** independent of wavelength (no dispersion relation, dispersion)

** independent of amplitude (linear media, not nonlinear).

* with constant waveform, or shape

This wave can then be described by the two-dimensional functions

: (waveform traveling to the right)

: (waveform traveling to the left)

or, more generally, by d'Alembert's formula:

:

representing two component waveforms and traveling through the medium in opposite directions. A generalized representation of this wave can be obtained as the partial differential equation

:

General solutions are based upon Duhamel's principle.

Beside the second order wave equations that are describing a standing wave field, the one-way wave equation describes the propagation of single wave in a defined direction.

Wave forms

Amplitude and modulation

The amplitude of a wave may be constant (in which case the wave is a ''c.w.'' or ''continuous wave''), or may be ''modulated'' so as to vary with time and/or position. The outline of the variation in amplitude is called the ''envelope'' of the wave. Mathematically, the Amplitude modulation, modulated wave can be written in the form:

:

where is the amplitude envelope of the wave, is the ''wavenumber'' and is the ''phase (waves), phase''. If the group velocity (see below) is wavelength-independent, this equation can be simplified as:

:

showing that the envelope moves with the group velocity and retains its shape. Otherwise, in cases where the group velocity varies with wavelength, the pulse shape changes in a manner often described using an ''envelope equation''.

The amplitude of a wave may be constant (in which case the wave is a ''c.w.'' or ''continuous wave''), or may be ''modulated'' so as to vary with time and/or position. The outline of the variation in amplitude is called the ''envelope'' of the wave. Mathematically, the Amplitude modulation, modulated wave can be written in the form:

:

where is the amplitude envelope of the wave, is the ''wavenumber'' and is the ''phase (waves), phase''. If the group velocity (see below) is wavelength-independent, this equation can be simplified as:

:

showing that the envelope moves with the group velocity and retains its shape. Otherwise, in cases where the group velocity varies with wavelength, the pulse shape changes in a manner often described using an ''envelope equation''.

Phase velocity and group velocity

There are two velocities that are associated with waves, the phase velocity and the group velocity. Phase velocity is the rate at which the phase (waves), phase of the wave Wave propagation, propagates in space: any given phase of the wave (for example, the crest (physics), crest) will appear to travel at the phase velocity. The phase velocity is given in terms of the wavelength (lambda) and Wave period, period as : Group velocity is a property of waves that have a defined envelope, measuring propagation through space (that is, phase velocity) of the overall shape of the waves' amplitudes – modulation or envelope of the wave.Special waves

Sine waves

Plane waves

A plane wave is a kind of wave whose value varies only in one spatial direction. That is, its value is constant on a plane that is perpendicular to that direction. Plane waves can be specified by a vector of unit length indicating the direction that the wave varies in, and a wave profile describing how the wave varies as a function of the displacement along that direction () and time (). Since the wave profile only depends on the position in the combination , any displacement in directions perpendicular to cannot affect the value of the field. Plane waves are often used to model electromagnetic waves far from a source. For electromagnetic plane waves, the electric and magnetic fields themselves are transverse to the direction of propagation, and also perpendicular to each other.Standing waves

A standing wave, also known as a ''stationary wave'', is a wave whose Envelope (waves), envelope remains in a constant position. This phenomenon arises as a result of Interference (wave propagation), interference between two waves traveling in opposite directions.

The ''sum'' of two counter-propagating waves (of equal amplitude and frequency) creates a ''standing wave''. Standing waves commonly arise when a boundary blocks further propagation of the wave, thus causing wave reflection, and therefore introducing a counter-propagating wave. For example, when a violin string is displaced, transverse waves propagate out to where the string is held in place at the Bridge (instrument), bridge and the Nut (string instrument), nut, where the waves are reflected back. At the bridge and nut, the two opposed waves are in antiphase and cancel each other, producing a node (physics), node. Halfway between two nodes there is an antinode, where the two counter-propagating waves ''enhance'' each other maximally. There is no net Energy transfer, propagation of energy over time.

A standing wave, also known as a ''stationary wave'', is a wave whose Envelope (waves), envelope remains in a constant position. This phenomenon arises as a result of Interference (wave propagation), interference between two waves traveling in opposite directions.

The ''sum'' of two counter-propagating waves (of equal amplitude and frequency) creates a ''standing wave''. Standing waves commonly arise when a boundary blocks further propagation of the wave, thus causing wave reflection, and therefore introducing a counter-propagating wave. For example, when a violin string is displaced, transverse waves propagate out to where the string is held in place at the Bridge (instrument), bridge and the Nut (string instrument), nut, where the waves are reflected back. At the bridge and nut, the two opposed waves are in antiphase and cancel each other, producing a node (physics), node. Halfway between two nodes there is an antinode, where the two counter-propagating waves ''enhance'' each other maximally. There is no net Energy transfer, propagation of energy over time.

Physical properties

Waves exhibit common behaviors under a number of standard situations, for example:Transmission and media

Waves normally move in a straight line (that is, rectilinearly) through a ''transmission medium''. Such media can be classified into one or more of the following categories: * A ''bounded medium'' if it is finite in extent, otherwise an ''unbounded medium'' * A ''linear medium'' if the amplitudes of different waves at any particular point in the medium can be added * A ''uniform medium'' or ''homogeneous medium'' if its physical properties are unchanged at different locations in space * An ''anisotropic medium'' if one or more of its physical properties differ in one or more directions * An ''isotropic medium'' if its physical properties are the ''same'' in all directionsAbsorption

Waves are usually defined in media which allow most or all of a wave's energy to propagate without Insertion loss, loss. However materials may be characterized as "lossy" if they remove energy from a wave, usually converting it into heat. This is termed "absorption." A material which absorbs a wave's energy, either in transmission or reflection, is characterized by a refractive index which is Complex number, complex. The amount of absorption will generally depend on the frequency (wavelength) of the wave, which, for instance, explains why objects may appear colored.Reflection

When a wave strikes a reflective surface, it changes direction, such that the angle made by the incident ray, incident wave and line perpendicular, normal to the surface equals the angle made by the reflected wave and the same normal line.Refraction

Refraction is the phenomenon of a wave changing its speed. Mathematically, this means that the size of the phase velocity changes. Typically, refraction occurs when a wave passes from one Transmission medium, medium into another. The amount by which a wave is refracted by a material is given by the refractive index of the material. The directions of incidence and refraction are related to the refractive indices of the two materials by Snell's law.

Refraction is the phenomenon of a wave changing its speed. Mathematically, this means that the size of the phase velocity changes. Typically, refraction occurs when a wave passes from one Transmission medium, medium into another. The amount by which a wave is refracted by a material is given by the refractive index of the material. The directions of incidence and refraction are related to the refractive indices of the two materials by Snell's law.

Diffraction

A wave exhibits diffraction when it encounters an obstacle that bends the wave or when it spreads after emerging from an opening. Diffraction effects are more pronounced when the size of the obstacle or opening is comparable to the wavelength of the wave.Interference

When waves in a linear medium (the usual case) cross each other in a region of space, they do not actually interact with each other, but continue on as if the other one weren't present. However at any point ''in'' that region the ''field quantities'' describing those waves add according to the superposition principle. If the waves are of the same frequency in a fixed phase (waves), phase relationship, then there will generally be positions at which the two waves are ''in phase'' and their amplitudes ''add'', and other positions where they are ''out of phase'' and their amplitudes (partially or fully) ''cancel''. This is called an Interference (wave propagation), interference pattern.Polarization

Dispersion

A wave undergoes dispersion when either the phase velocity or the group velocity depends on the wave frequency.

Dispersion is most easily seen by letting white light pass through a prism (optics), prism, the result of which is to produce the spectrum of colors of the rainbow. Isaac Newton performed experiments with light and prisms, presenting his findings in the ''Opticks'' (1704) that white light consists of several colors and that these colors cannot be decomposed any further.

A wave undergoes dispersion when either the phase velocity or the group velocity depends on the wave frequency.

Dispersion is most easily seen by letting white light pass through a prism (optics), prism, the result of which is to produce the spectrum of colors of the rainbow. Isaac Newton performed experiments with light and prisms, presenting his findings in the ''Opticks'' (1704) that white light consists of several colors and that these colors cannot be decomposed any further.

Mechanical waves

Waves on strings

The speed of a transverse wave traveling along a vibrating string (''v'') is directly proportional to the square root of the Tension (mechanics), tension of the string (''T'') over the linear mass density (''μ''): : where the linear density ''μ'' is the mass per unit length of the string.Acoustic waves

Acoustic or sound waves travel at speed given by : or the square root of the adiabatic bulk modulus divided by the ambient fluid density (see speed of sound).Water waves

* ripple tank, Ripples on the surface of a pond are actually a combination of transverse and longitudinal waves; therefore, the points on the surface follow orbital paths.

* Sound – a mechanical wave that propagates through gases, liquids, solids and plasmas;

* Inertial waves, which occur in rotating fluids and are restored by the Coriolis effect;

* Ocean surface waves, which are perturbations that propagate through water.

* ripple tank, Ripples on the surface of a pond are actually a combination of transverse and longitudinal waves; therefore, the points on the surface follow orbital paths.

* Sound – a mechanical wave that propagates through gases, liquids, solids and plasmas;

* Inertial waves, which occur in rotating fluids and are restored by the Coriolis effect;

* Ocean surface waves, which are perturbations that propagate through water.

Seismic waves

Seismic waves are waves of energy that travel through the Earth's layers, and are a result of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, magma movement, large landslides and large man-made explosions that give out low-frequency acoustic energy.Doppler effect

The Doppler effect (or the Doppler shift) is the change in frequency of a wave in relation to an observer (physics), observer who is moving relative to the wave source. It is named after the Austrian physicist Christian Doppler, who described the phenomenon in 1842.Shock waves

Other

* Waves of Traffic wave, traffic, that is, propagation of different densities of motor vehicles, and so forth, which can be modeled as kinematic waves And: * metachronal rhythm, Metachronal wave refers to the appearance of a traveling wave produced by coordinated sequential actions.Electromagnetic waves

An electromagnetic wave consists of two waves that are oscillations of the electric field, electric and magnetic field, magnetic fields. An electromagnetic wave travels in a direction that is at right angles to the oscillation direction of both fields. In the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell showed that, in vacuum, the electric and magnetic fields satisfy the wave equation both with speed equal to that of the speed of light. From this emerged the idea that visible light, light is an electromagnetic wave. Electromagnetic waves can have different frequencies (and thus wavelengths), giving rise to various types of radiation such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and Gamma rays.

An electromagnetic wave consists of two waves that are oscillations of the electric field, electric and magnetic field, magnetic fields. An electromagnetic wave travels in a direction that is at right angles to the oscillation direction of both fields. In the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell showed that, in vacuum, the electric and magnetic fields satisfy the wave equation both with speed equal to that of the speed of light. From this emerged the idea that visible light, light is an electromagnetic wave. Electromagnetic waves can have different frequencies (and thus wavelengths), giving rise to various types of radiation such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and Gamma rays.

Quantum mechanical waves

Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation describes the wave-like behavior of particles in quantum mechanics. Solutions of this equation are wave functions which can be used to describe the probability density of a particle.Dirac equation

The Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation detailing electromagnetic interactions. Dirac waves accounted for the fine details of the hydrogen spectrum in a completely rigorous way. The wave equation also implied the existence of a new form of matter, antimatter, previously unsuspected and unobserved and which was experimentally confirmed. In the context of quantum field theory, the Dirac equation is reinterpreted to describe quantum fields corresponding to spin- particles.

de Broglie waves

Louis de Broglie postulated that all particles with momentum have a wavelength : where ''h'' is Planck's constant, and ''p'' is the magnitude of the momentum of the particle. This hypothesis was at the basis of quantum mechanics. Nowadays, this wavelength is called the de Broglie wavelength. For example, the electrons in a cathode-ray tube, CRT display have a de Broglie wavelength of about 10−13 m. A wave representing such a particle traveling in the ''k''-direction is expressed by the wave function as follows: : where the wavelength is determined by the wave vector k as: : and the momentum by: : However, a wave like this with definite wavelength is not localized in space, and so cannot represent a particle localized in space. To localize a particle, de Broglie proposed a superposition of different wavelengths ranging around a central value in a wave packet, a waveform often used in quantum mechanics to describe the wave function of a particle. In a wave packet, the wavelength of the particle is not precise, and the local wavelength deviates on either side of the main wavelength value. In representing the wave function of a localized particle, the wave packet is often taken to have a Gaussian function, Gaussian shape and is called a ''Gaussian wave packet''. See for example and ,. Gaussian wave packets also are used to analyze water waves. For example, a Gaussian wavefunction ''ψ'' might take the form: : at some initial time ''t'' = 0, where the central wavelength is related to the central wave vector ''k''0 as λ0 = 2π / ''k''0. It is well known from the theory of Fourier analysis, or from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle (in the case of quantum mechanics) that a narrow range of wavelengths is necessary to produce a localized wave packet, and the more localized the envelope, the larger the spread in required wavelengths. The Fourier transform of a Gaussian is itself a Gaussian. Given the Gaussian: : the Fourier transform is: : The Gaussian in space therefore is made up of waves: : that is, a number of waves of wavelengths λ such that ''k''λ = 2 π. The parameter σ decides the spatial spread of the Gaussian along the ''x''-axis, while the Fourier transform shows a spread in wave vector ''k'' determined by 1/''σ''. That is, the smaller the extent in space, the larger the extent in ''k'', and hence in λ = 2π/''k''.

Gravity waves

Gravity waves are waves generated in a fluid medium or at the interface between two media when the force of gravity or buoyancy tries to restore equilibrium. A ripple on a pond is one example.Gravitational waves

gravitational radiation, Gravitational waves also travel through space. The first observation of gravitational waves was announced on 11 February 2016. Gravitational waves are disturbances in the curvature of spacetime, predicted by Einstein's theory of general relativity.See also

* Index of wave articlesWaves in general

Parameters

Waveforms

Electromagnetic waves

In fluids

* Airy wave theory, in fluid dynamics * Capillary wave, in fluid dynamics * Cnoidal wave, in fluid dynamics * Edge wave, a surface gravity wave fixed by refraction against a rigid boundary * Faraday wave, a type of wave in liquids * Gravity wave, in fluid dynamics * Sound wave, a wave of sound through a medium such as air or water * Sea wave spectrum * Shock wave, in aerodynamics * Internal wave, a wave within a fluid medium * Tidal wave, a scientifically incorrect name for a tsunami * Tollmien–Schlichting wave, in fluid dynamicsIn quantum mechanics

In relativity

Other specific types of waves

* Alfvén wave, in plasma physics * Atmospheric wave, a periodic disturbance in the fields of atmospheric variables * Fir wave, a forest configuration * Lamb waves, in solid materials * Rayleigh waves, surface acoustic waves that travel on solids * Spin wave, in magnetism * Spin density wave, in solid materials * Trojan wave packet, in particle science * Waves in plasmas, in plasma physicsRelated topics

* Beat (acoustics) * Cymatics * Doppler effect * Envelope detector * Fourier transform for computing periodicity in evenly spaced data * Group velocity * Harmonic * Index of wave articles * Inertial wave * Least-squares spectral analysis for computing periodicity in unevenly spaced data * List of waves named after people * Phase velocity * Reaction–diffusion system * Resonance * Ripple tank * Rogue wave * Shallow water equations * John N. Shive#Shive wave machine, Shive wave machine * Sound * Standing wave * Transmission medium * Wave turbulence * Wind waveReferences

Sources

* * * * . * * . *External links

The Feynman Lectures on Physics: Waves

Linear and nonlinear waves

{{Authority control Waves, Differential equations Articles containing video clips