The history of water supply and sanitation is one of a

logistical

Logistics is generally the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation. In a general business sense, logistics manages the flow of goods between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet the requirements of ...

challenge to provide

clean water

Drinking water is water that is used in drink or food preparation; potable water is water that is safe to be used as drinking water. The amount of drinking water required to maintain good health varies, and depends on physical activity level, ag ...

and

sanitation systems since the dawn of

civilization. Where water resources, infrastructure or sanitation systems were insufficient, diseases spread and people fell sick or died prematurely.

Major human settlements could initially develop only where fresh surface water was plentiful, such as near rivers or

natural springs. Throughout history, people have devised systems to make getting water into their communities and households and disposing of (and later also treating)

wastewater more convenient.

The historical focus of

sewage treatment was on the conveyance of raw sewage to a natural body of water, e.g. a

river or

ocean, where it would be diluted and dissipated. Early

human habitations were often built next to water sources. Rivers would often serve as a crude form of natural sewage disposal.

Over the millennia, technology has dramatically increased the distances across which water can be relocated. Furthermore, treatment processes to purify

drinking water and to treat wastewater have been improved.

Prehistory

During the

Neolithic era, humans dug the first permanent

water wells, from where vessels could be filled and carried by hand. Wells dug around 6500 BC have been found in the

Jezreel Valley. The size of human settlements was largely dependent on nearby available water.

A primitive indoor, tree bark lined, two-channel, stone, fresh and wastewater system appears to have featured in the houses of

Skara Brae, and the

Barnhouse Settlement

The Neolithic Barnhouse Settlement is sited by the shore of Loch of Harray, Orkney Mainland, Scotland, not far from the Standing Stones of Stenness, about 5 miles north-east of Stromness.

It was discovered in 1984 by Colin Richards. Excavation ...

, from around 3000 BCE, along with a cell-like enclave in a number of houses, of Skara Brae, that it has been suggested may have functioned as an early indoor

latrine.

Wastewater reuse activities

Waste

water reuse is an ancient practice, which has been applied since the dawn of human history, and is connected to the development of sanitation provision. Reuse of untreated

municipal wastewater has been practiced for many centuries with the objective of diverting

human waste

Human waste (or human excreta) refers to the waste products of the human digestive system, menses, and human metabolism including urine and faeces. As part of a sanitation system that is in place, human waste is collected, transported, treated a ...

outside of urban settlements. Likewise, land application of domestic wastewater is an old and common practice, which has gone through different stages of development.

Domestic wastewater was used for irrigation by prehistoric civilizations (e.g.

Mesopotamian,

Indus valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

, and

Minoan

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450B ...

) since the Bronze Age (ca. 3200–1100 BC). Thereafter, wastewater was used for

disposal,

irrigation, and

fertilization purposes by Hellenic civilizations and later by Romans in areas surrounding cities (e.g. Athens and Rome).

Bronze and early Iron Ages

Ancient Americas

In

ancient Peru, the

Nazca people employed a system of interconnected wells and an underground watercourse known as

puquios.

Ancient Near East

Mesopotamia

The Mesopotamians introduced the world to clay sewer pipes around 4000 BCE, with the earliest examples found in the Temple of Bel at

Nippur

Nippur (Sumerian language, Sumerian: ''Nibru'', often logogram, logographically recorded as , EN.LÍLKI, "Enlil City;"The Cambridge Ancient History: Prolegomena & Prehistory': Vol. 1, Part 1. Accessed 15 Dec 2010. Akkadian language, Akkadian: '' ...

and at

Eshnunna,

utilised to remove wastewater from sites, and capture rainwater, in wells. The city of

Uruk also demonstrates the first examples of brick constructed

latrines, from 3200 BCE. Clay pipes were later used in the

Hittite city of

Hattusa. They had easily detachable and replaceable segments, and allowed for cleaning.

Ancient Persia

The first sanitation systems within

prehistoric Iran

The prehistory of the Iranian plateau, and the wider region now known as Greater Iran, as part of the prehistory of the Near East is conventionally divided into the Paleolithic, Epipaleolithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age peri ...

were built near the city of

Zabol.

Persian

qanats and

ab anbars have been used for

water supply and cooling.

Ancient Egypt

The ,

Pyramid of Sahure, and adjoining temple complex at

Abusir

Abusir ( ar, ابو صير ; Egyptian ''pr wsjr'' cop, ⲃⲟⲩⲥⲓⲣⲓ ' "the House or Temple of Osiris"; grc, Βούσιρις) is the name given to an Egyptian archaeological locality – specifically, an extensive necropolis of ...

, was discovered to have a network of copper drainage pipes.

Ancient East Asia

Ancient China

Some of the earliest evidence of water wells are located in China. The Neolithic Chinese discovered and made extensive use of deep drilled groundwater for drinking. The Chinese text ''

The Book of Changes'', originally a divination text of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 BC), contains an entry describing how the ancient Chinese maintained their wells and protected their sources of water. Archaeological evidence and old Chinese documents reveal that the prehistoric and ancient Chinese had the aptitude and skills for digging deep water wells for drinking water as early as 6000 to 7000 years ago. A well excavated at the

Hemedu excavation site was believed to have been built during the Neolithic era.

The well was caused by four rows of logs with a square frame attached to them at the top of the well. Sixty additional tile wells southwest of Beijing are also believed to have been built around 600 BC for drinking and irrigation.

Plumbing is also known to have been used in

East Asia since the

Qin Qin may refer to:

Dynasties and states

* Qin (state) (秦), a major state during the Zhou Dynasty of ancient China

* Qin dynasty (秦), founded by the Qin state in 221 BC and ended in 206 BC

* Daqin (大秦), ancient Chinese name for the Roman Emp ...

and

Han

Han may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Han Chinese, or Han People (): the name for the largest ethnic group in China, which also constitutes the world's largest ethnic group.

** Han Taiwanese (): the name for the ethnic group of the Taiwanese p ...

Dynasties of China.

Indus Valley Civilization

The

Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

in Asia shows early evidence of public water supply and sanitation. The system the Indus developed and managed included a number of advanced features. An exceptional example is the Indus city of

Lothal (c. 2350–1810 BCE). In Lothal the ruler's house had their own private bathing platform and latrine, which was connected to an open street drain that discharged into the towns dock. A number of the other houses of the acropolis had burnished brick bathing platforms, that drained into a covered brick sewer, held together with a gypsum-based mortar, that ran to a

soak pit outside the towns walls, while the lower town offered soak jars (large buried urns, with a hole in the bottom to permit liquids to drain), the latter of which were regularly emptied and cleaned. Water was supplied from two wells in the town, one in the acropolis, and the other on the edge of the dock.

The urban areas of the Indus Valley civilization included public and private baths. Sewage was disposed through underground drains built with precisely laid bricks, and a sophisticated water management system with numerous reservoirs was established. In the drainage systems, drains from houses were connected to wider public drains. Many of the buildings at Mohenjo-daro had two or more stories. Water from the roof and upper storey bathrooms was carried through enclosed terracotta pipes or open chutes that emptied out onto the street drains.

The earliest evidence of urban sanitation was seen in

Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

,

Mohenjo-daro, and the recently discovered

Rakhigarhi of Indus Valley civilization. This urban plan included the world's first urban sanitation systems. Within the city, individual homes or groups of homes obtained water from

wells

Wells most commonly refers to:

* Wells, Somerset, a cathedral city in Somerset, England

* Well, an excavation or structure created in the ground

* Wells (name)

Wells may also refer to:

Places Canada

*Wells, British Columbia

England

* Wells ...

. From a room that appears to have been set aside for bathing, waste water was directed to covered drains, which lined the major streets.

Devices such as

shadoofs were used to lift water to ground level. Ruins from the Indus Valley Civilization like

Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan and

Dholavira in

Gujarat in India had settlements with some of the ancient world's most sophisticated sewage systems. They included drainage channels,

rainwater harvesting, and street ducts.

Stepwells have mainly been used in the Indian subcontinent.

Ancient Mediterranean

Ancient Greece

The ancient Greek civilization of

Crete, known as the

Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450BC ...

, built advanced underground clay pipes for sanitation and water supply.

Their capital,

Knossos, had a well-organized water system for bringing in clean water, taking out waste water and storm sewage canals for overflow when there was heavy rain. People constructed flushed toilets in ancient Crete, like in ancient Egypt and before them at places of the Indus Civilization, with the facilities on Crete possibly having a first

flush installation for pouring water into, dating back to 16th century BC.

These Minoan sanitation facilities were connected to stone sewers that were regularly flushed by rain, flowing in through the collection system.

In addition to sophisticated water and sewer systems they devised elaborate heating systems. The Ancient Greeks of

Athens and

Asia Minor also used an indoor plumbing system, used for pressurized showers. The Greek inventor

Heron

The herons are long-legged, long-necked, freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae, with 72 recognised species, some of which are referred to as egrets or bitterns rather than herons. Members of the genera ''Botaurus'' and ''Ixobrychus ...

used pressurized piping for fire fighting purposes in the City of

Alexandria. The Mayans were the third earliest civilization to have employed a system of indoor plumbing using pressurized water.

An inverted siphon system, along with glass covered clay pipes, was used for the first time in the palaces of Crete, Greece. It is still in working condition, after about 3000 years.

Roman Empire

In ancient Rome, the

Cloaca Maxima, considered a marvel of engineering, discharged into the

Tiber. Public

latrines were built over the Cloaca Maxima.

Beginning in the

Roman era

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

a

water wheel device known as a

noria supplied water to

aqueducts and other water distribution systems in major cities in Europe and the Middle East.

The

Roman Empire had

indoor plumbing, meaning a system of aqueducts and pipes that terminated in homes and at public wells and fountains for people to use. Rome and other nations used

lead pipes; while commonly thought to be the cause of lead poisoning in the Roman Empire, the combination of running water which did not stay in contact with the pipe for long and the deposition of

precipitation scale actually mitigated the risk from lead pipes.

Roman towns and garrisons in the

United Kingdom between 46 BC and 400 AD had complex sewer networks sometimes constructed out of hollowed-out

elm logs, which were shaped so that they butted together with the down-stream pipe providing a socket for the upstream pipe.

Medieval and early modern ages

Nepal

In Nepal the construction of water conduits like drinking fountains and wells is considered a pious act.

[UN-HABITAT, 2007. Water Movement in Patan with reference to Traditional Stone Spouts]

, [Water Nepal: A Historical Perspective](_blank)

GWP Nepal / Jalsrot Vikas Sanstha, September 2018, retrieved 11 September 2019

A drinking water supply system was developed starting at least as early as 550 AD.

[Disaster Risk Management for the Historic City of Patan, Nepal]

by Rits-DMUCH, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan and Institute of Engineering, Tribhuvan University,Kathmandu, Nepal, 2012, retrieved 16 September 2019 This ''

dhunge dhara'' or ''hiti'' system consists of carved stone fountains through which water flows uninterrupted from underground sources. These are supported by numerous ponds and canals that form an elaborate network of water bodies, created as a water resource during the dry season and to help alleviate the water pressure caused by the monsoon rains. After the introduction of modern, piped water systems, starting in the late 19th century, this old system has fallen into disrepair and some parts of it are lost forever.

Nevertheless, many people of Nepal still rely on the old hitis on a daily basis.

[Traditional stonespouts]

Posted by Administrator of NGOforum.net, 28 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

In 2008 the dhunge dharas of the Kathmandu Valley produced 2.95 million

litres of water per day.

[Kathmandu Valley Groundwater Outlook]

. Shrestha S., Pradhananga D., Pandey V.P. (Eds.), 2012, Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), The Small Earth Nepal (SEN), Center of Research for Environment Energy and Water (CREEW), International Research Center for River Basin Environment-University of Yamanashi (ICRE-UY), Kathmandu, Nepal

Of the 389 stone spouts found in the Kathmandu Valley in 2010, 233 were still in use, serving about 10% of Kathmandu's population. 68 had gone dry, 45 were lost entirely and 43 were connected to the municipal water supply instead of their original source.

Islamic world

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

stresses the importance of cleanliness and personal hygiene.

Islamic hygienical jurisprudence, which dates back to the 7th century, has a number of elaborate rules.

Taharah (ritual purity) involves performing

wudu (ablution) for the five daily

salah

(, plural , romanized: or Old Arabic ͡sˤaˈloːh, ( or Old Arabic ͡sˤaˈloːtʰin construct state) ), also known as ( fa, نماز) and also spelled , are prayers performed by Muslims. Facing the , the direction of the Kaaba wit ...

(prayers), as well as regularly performing

ghusl

( ar, غسل ', ) is an Arabic term to the full-body ritual purification mandatory before the performance of various rituals and prayers, for any adult Muslim after sexual intercourse/ejaculation or completion of the menstrual cycle.

The washin ...

(bathing), which led to

bathhouses being built across the

Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

.

Islamic toilet hygiene also requires

washing with water after using the toilet, for purity and to minimize germs.

In the

Abbasid Caliphate (8th-13th centuries), its capital city of

Baghdad (Iraq) had 65,000 baths, along with a sewer system. Cities of the

medieval Islamic world

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

had

water supply systems powered by

hydraulic technology that supplied

drinking water along with much greater quantities of water for ritual washing, mainly in

mosques

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, i ...

and

hammams (baths). Bathing establishments in various cities were rated by Arabic writers in

travel guides. Medieval Islamic cities such as Baghdad,

Córdoba (

Islamic Spain),

Fez

Fez most often refers to:

* Fez (hat), a type of felt hat commonly worn in the Ottoman Empire

* Fez, Morocco (or Fes), the second largest city of Morocco

Fez or FEZ may also refer to:

Media

* ''Fez'' (Frank Stella), a 1964 painting by the moder ...

(Morocco) and

Fustat (Egypt) also had sophisticated

waste disposal and

sewage systems with interconnected networks of sewers. The city of Fustat also had multi-storey

tenement buildings (with up to six floors) with

flush toilets, which were connected to a water supply system, and

flues on each floor carrying waste to underground channels.

Al-Karaji

( fa, ابو بکر محمد بن الحسن الکرجی; c. 953 – c. 1029) was a 10th-century Persian people, Persian mathematician and engineer who flourished at Baghdad. He was born in Karaj, a city near Tehran. His three principal sur ...

(c. 953–1029) wrote a book, ''The Extraction of Hidden Waters'', which presented ground-breaking ideas and descriptions of hydrological and hydrogeological perceptions such as components of the hydrological cycle, groundwater quality, and driving factors of groundwater flow. He also gave an early description of a

water filtration

A water filter removes impurities by lowering contamination of water using a fine physical barrier, a chemical process, or a biological process. Filters cleanse water to different extents, for purposes such as: providing agricultural irrigation ...

process.

Sub-Saharan Africa

In post-classical

Kilwa

Kilwa Kisiwani (English: ''Kilwa Island'') is an island, national historic site, and hamlet community located in the township of Kilwa Masoko, the district seat of Kilwa District in the Tanzanian region of Lindi Region in southern Tanzania. K ...

plumbing was prevalent in the stone homes of the natives.

The Husani Kubwa Palace as well as other buildings for the ruling elite and wealthy included the luxury of indoor plumbing.

In the

Ashanti Empire, toilets were housed in two story buildings that were flushed with gallons of boiling water.

Medieval Europe

Christianity

Christianity places an

emphasis on hygiene.

Despite the denunciation of the

mixed bathing

Mixed bathing is the sharing of a pool, beach or other place by swimmers of both sexes. Mixed bathing usually refers to swimming or other water-based recreational activities in public or semi-public facilities, such as hotel or holiday resort pool ...

style of Roman pools by

early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

clergy, as well as the pagan custom of women naked bathing in front of men, this did not stop the Church from urging its followers to go to public baths for bathing,

which contributed to hygiene and good health according to the

Church Fathers,

Clement of Alexandria and

Tertullian.

The Church built

public bathing facilities that were separate for both sexes near

monasteries and pilgrimage sites; also, the

popes

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

situated baths within church

basilicas and monasteries since the early Middle Ages.

Pope

Gregory the Great urged his followers on value of

bathing as a bodily need.

Contrary to popular belief

bathing and

sanitation were not lost in Europe with the collapse of the

Roman Empire.

Public bathhouses were common in medieval

Christendom larger towns and cities such as

Constantinople,

Paris,

Regensburg

Regensburg or is a city in eastern Bavaria, at the confluence of the Danube, Naab and Regen rivers. It is capital of the Upper Palatinate subregion of the state in the south of Germany. With more than 150,000 inhabitants, Regensburg is the f ...

,

Rome and

Naples. And great bathhouses were built in

Byzantine centers such as

Constantinople and

Antioch.

There is little record of other sanitation systems (apart of

sanitation in ancient Rome) in most of Europe until the

High Middle Ages. Unsanitary conditions and overcrowding were widespread throughout

Europe and

Asia during the

Middle Ages. This resulted in

pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic (epidemiology), endemic disease wi ...

s such as the

Plague of Justinian (541–542) and the

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

(1347–1351), which killed tens of millions of people. Very high infant and child mortality prevailed in Europe throughout

medieval times, due partly to deficiencies in sanitation.

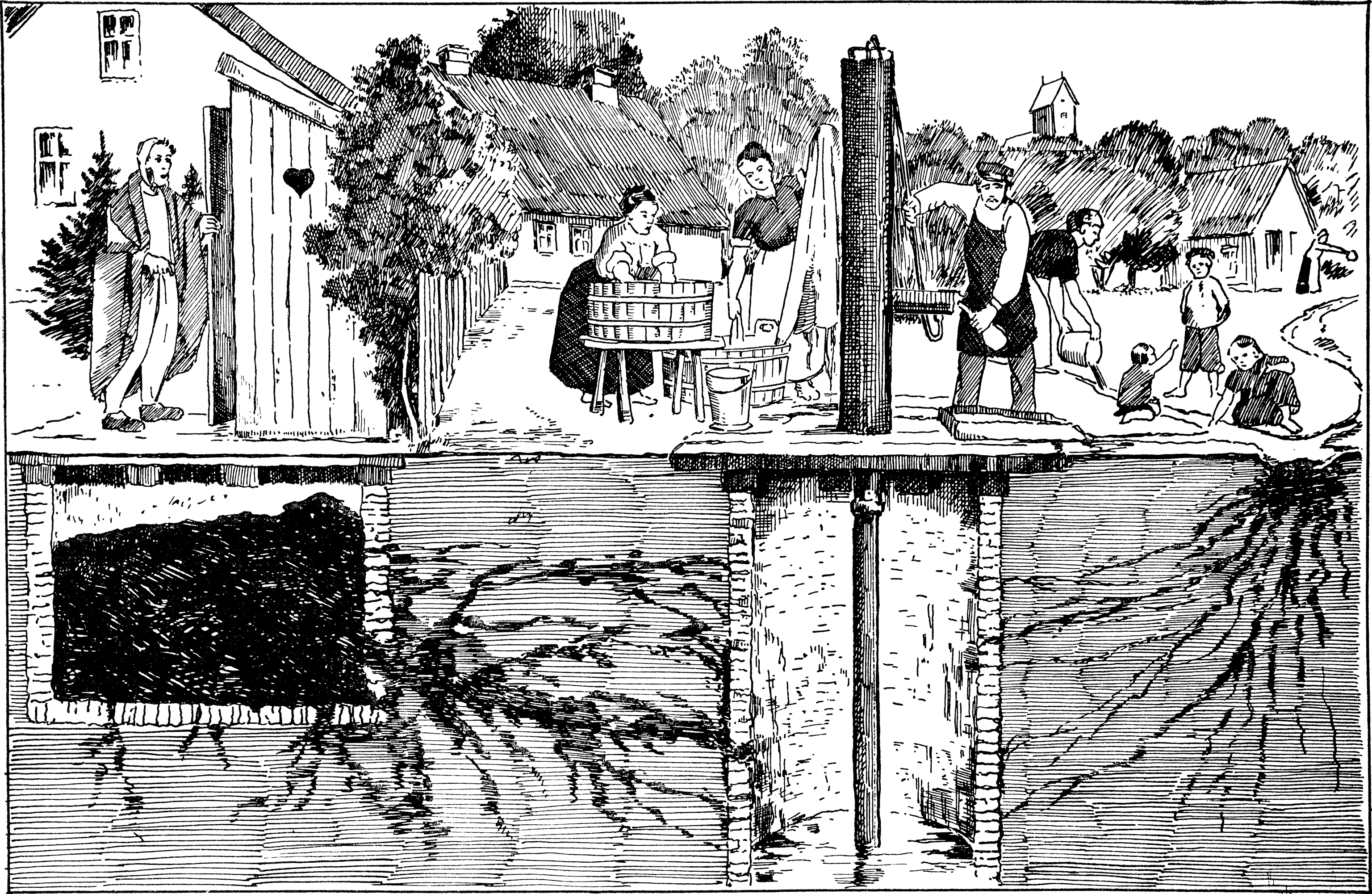

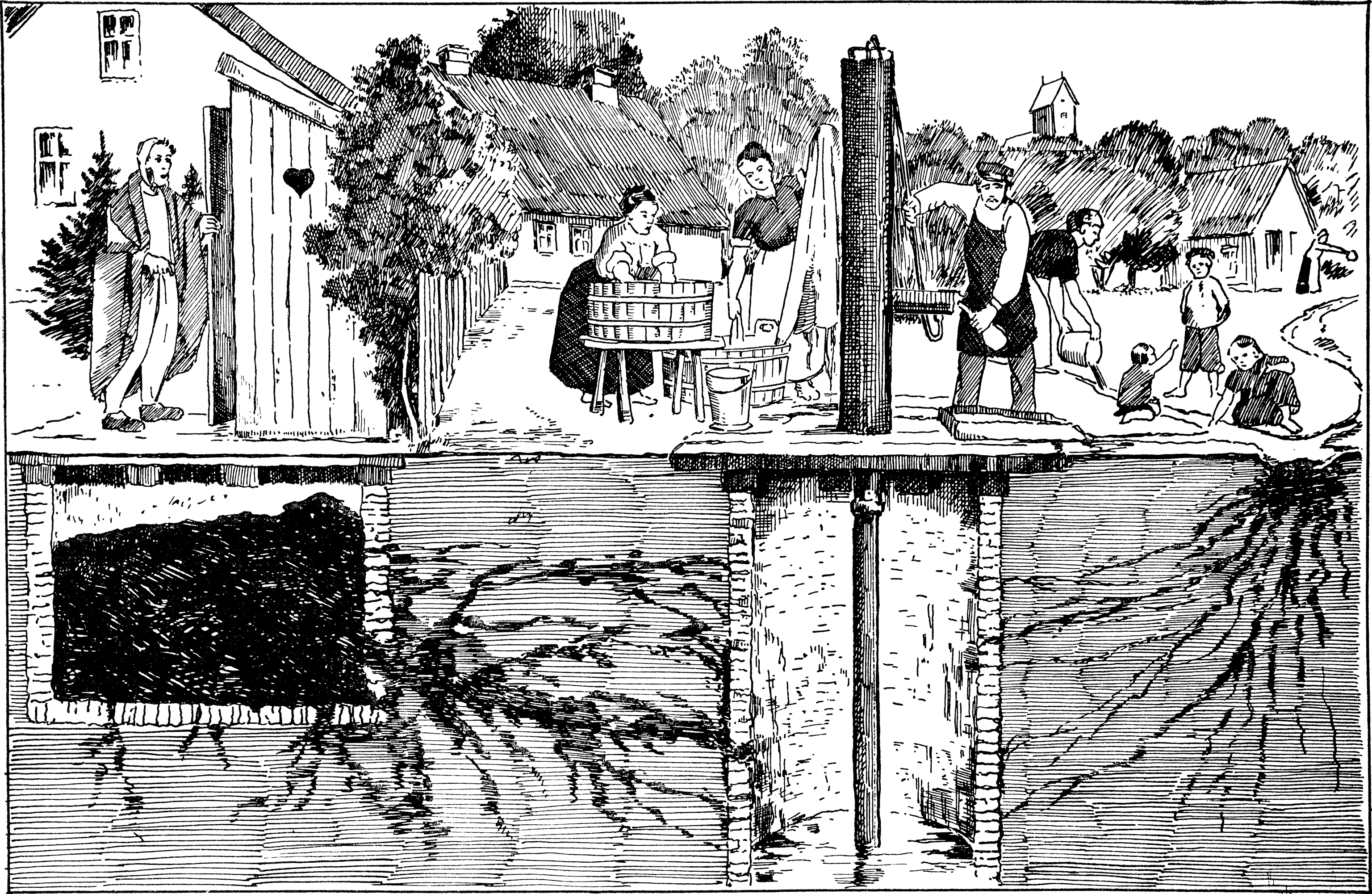

In medieval European cities, small natural waterways used for carrying off

wastewater were eventually covered over and functioned as sewers.

London's

River Fleet is such a system. Open drains, or gutters, for waste water run-off ran along the center of some streets. These were known as "kennels" (i.e., canals, channels), and in Paris were sometimes known as “split streets,” as the waste water running along the middle physically split the streets into two halves. The first closed sewer constructed in Paris was designed by Hugues Aubird in 1370 on

Rue Montmartre

Boulevard Montmartre is one of the four grands boulevards of Paris. It was constructed in 1763. Contrary to what its name may suggest, the road is not situated on the hills of Montmartre. It is the easternmost of the grand boulevards.

History

...

(Montmartre Street), and was 300 meters long. The original purpose of designing and constructing a closed sewer in Paris was less-so for waste management as much as it was to hold back the stench coming from the odorous waste water.

[George Commair, "The Waste Water Network: and underground view of Paris," in Great Rivers History: Proceedings and Invited Papers for the EWRI Congress and History Symposium, May 17–19, 2009, Kansas City, Missouri, ed. Jerry R. Roger, (Reston: American Society of Civil Engineers, 2009), 91–96]

In

Dubrovnik, then known as Ragusa (Latin name), the Statute of 1272 set out the parameters for the construction of septic tanks and channels for the removal of dirty water. Throughout the 14th and 15th century the sewage system was built, and it is still operational today, with minor changes and repairs done in recent centuries.

Pail closets,

outhouses, and

cesspits were used to collect human waste. The use of human waste as

fertilizer was especially important in China and Japan, where cattle manure was less available. However, most cities did not have a functioning sewer system before the

Industrial era , relying instead on nearby rivers or occasional

rain showers to wash away the sewage from the streets . In some places,

waste water simply ran down the streets, which had

stepping stones to keep pedestrians out of the muck, and eventually drained as runoff into the local watershed.

In the 16th century,

Sir John Harington invented a flush toilet as a device for

Queen Elizabeth I (his godmother) that released wastes into

cesspools.

After the adoption of

gunpowder, municipal outhouses became an important source of raw material for the making of

saltpeter in European countries.

In London, the contents of the city's outhouses were collected every night by commissioned wagons and delivered to the nitrite beds where it was laid into specially designed soil beds to produce earth rich in mineral nitrates. The nitrate rich-earth would be then further processed to produce saltpeter, or

potassium nitrate, an important ingredient in

black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

that played a part in the making of gunpowder.

Classic and early modern Mesoamerica

The

Classic Maya

A classic is an outstanding example of a particular style; something of lasting worth or with a timeless quality; of the first or highest quality, class, or rank – something that exemplifies its class. The word can be an adjective (a ''c ...

at

Palenque had underground aqueducts and

flush toilets; the Classic Maya even used household water filters using locally abundant limestone carved into a porous cylinder, made so as to work in a manner strikingly similar to Modern

ceramic water filter

Ceramic water filters (CWF) are an inexpensive and effective type of water filter that rely on the small pore size of ceramic material to filter dirt, debris, and bacteria out of water. This makes them ideal for use in developing countries, and po ...

s.

In

Spain and

Spanish America, a community operated watercourse known as an

acequia, combined with a simple sand filtration system, provided

potable water.

Sewage farms for disposal and irrigation

“

Sewage farms” (i.e. wastewater application to the land for disposal and agricultural use) were operated in Bunzlau (Silesia) in 1531, in Edinburgh (Scotland) in 1650, in Paris (France) in 1868, in Berlin (Germany) in 1876 and in different parts of the USA since 1871, where wastewater was used for beneficial crop production. In the following centuries (16th and 18th centuries) in many rapidly growing countries/cities of Europe (e.g. Germany, France) and the United States, “sewage farms” were increasingly seen as a solution for the disposal of large volumes of the wastewater, some of which are still in operation today. Irrigation with sewage and other wastewater effluents has a long history also in China and India; while also a large “sewage farm” was established in Melbourne, Australia, in 1897.

Modern age

Water supply

Until the

Enlightenment era, little progress was made in water supply and sanitation and the engineering skills of the Romans were largely neglected throughout Europe. It was in the 18th century that a rapidly growing population fueled a boom in the establishment of private

water supply networks in

London.

London water supply infrastructure

London's water supply infrastructure has developed over the centuries in line with the expansion of London. For much of London's history, private companies supplied fresh water to various parts of London from wells, the River Thames and the Rive ...

developed over many centuries from early mediaeval conduits, through major 19th-century treatment works built in response to

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

threats, to modern, large-scale reservoirs. The first screw-down

water tap was patented in 1845 by Guest and Chrimes, a brass foundry in

Rotherham.

The first documented use of

sand filters to purify the water supply dates to 1804, when the owner of a bleachery in

Paisley, Scotland, John Gibb, installed an experimental filter, selling his unwanted surplus to the public. The first treated public water supply in the world was installed by engineer

James Simpson for the

Chelsea Waterworks Company in London in 1829.

The practice of water treatment soon became mainstream, and the virtues of the system were made starkly apparent after the investigations of the physician

John Snow

John Snow (15 March 1813 – 16 June 1858) was an English physician and a leader in the development of anaesthesia and medical hygiene. He is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology, in part because of his work in tracing the so ...

during the

1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak

Events

January–March

* January 4 – The McDonald Islands are discovered by Captain William McDonald aboard the ''Samarang''.

* January 6 – The fictional detective Sherlock Holmes is perhaps born.

* January 9 – The ...

demonstrated the role of the water supply in spreading the cholera epidemic.

Sewer systems

A significant development was the construction of a network of sewers to collect wastewater. In some cities, including

Rome,

Istanbul (

Constantinople) and

Fustat, networked ancient sewer systems continue to function today as collection systems for those cities' modernized sewer systems. Instead of flowing to a river or the sea, the pipes have been re-routed to modern sewer treatment facilities.

Basic sewer systems were used for waste removal in ancient

Mesopotamia, where vertical shafts carried the waste away into cesspools. Similar systems existed in the

Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

civilization in modern-day Pakistan and in Ancient

Crete and

Greece. In the

Middle Ages the sewer systems built by the

Romans fell into disuse and waste was collected into cesspools that were periodically emptied by workers known as 'rakers' who would often sell it as

fertilizer to farmers outside the city.

Archaeological discoveries have shown that some of the earliest sewer systems were developed in the third millennium BCE in the ancient cities of

Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

and

Mohenjo-daro in present-day

Pakistan. The primitive sewers were carved in the ground alongside buildings. This discovery reveals the conceptual understanding of waste disposal by early civilizations.

However, until the

Enlightenment era, little progress was made in water supply and sanitation and the engineering skills of the Romans were largely neglected throughout Europe. This began to change in the 17th and 18th centuries with a rapid expansion in waterworks and

pumping systems.

The tremendous

growth of cities in Europe and North America during the

Industrial Revolution quickly led to crowding, which acted as a constant source for the outbreak of disease.

As cities grew in the 19th century concerns were raised about

public health.

As part of a trend of municipal

sanitation programs in the late 19th and 20th centuries, many cities constructed extensive

gravity sewer systems to help control outbreaks of

disease such as

typhoid and

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

.

and

sanitary sewers were necessarily developed along with the growth of cities. By the 1840s the luxury of

indoor plumbing, which mixes human waste with water and flushes it away, eliminated the need for

cesspools.

Modern sewerage systems were first built in the mid-nineteenth century as a reaction to the exacerbation of sanitary conditions brought on by heavy

industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and

urbanization. Baldwin Latham, a British civil engineer contributed to the rationalization of sewerage and house drainage systems and was a pioneer in sanitary engineering. He developed the concept of oval sewage pipe to facilitate sewer drainage and to prevent sludge deposition and flooding.

Due to the contaminated water supply,

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

outbreaks occurred in

1832, 1849 and 1855 in

London, killing tens of thousands of people. This, combined with the

Great Stink

The Great Stink was an event in Central London during July and August 1858 in which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent that was present on the banks of the River Thames. The problem had been m ...

of 1858, when the smell of untreated human waste in the

River Thames became overpowering, and the report into sanitation reform of the

Royal Commissioner

Edwin Chadwick

Sir Edwin Chadwick KCB (24 January 18006 July 1890) was an English social reformer who is noted for his leadership in reforming the Poor Laws in England and instituting major reforms in urban sanitation and public health. A disciple of Uti ...

,

led to the

Metropolitan Commission of Sewers appointing

Joseph Bazalgette

Sir Joseph William Bazalgette CB (; 28 March 181915 March 1891) was a 19th-century English civil engineer. As chief engineer of London's Metropolitan Board of Works, his major achievement was the creation (in response to the Great Stink of 1 ...

to construct a vast underground sewage system for the safe removal of waste. Contrary to Chadwick's recommendations, Bazalgette's system, and others later built in

Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

, did not pump the sewage onto farm land for use as fertilizer; it was simply piped to a natural waterway away from population centres, and pumped back into the environment.

Liverpool, London and other cities in the UK

As recently as the late 19th-century sewerage systems in some parts of the rapidly industrializing

United Kingdom were so inadequate that

water-borne disease

Waterborne diseases are conditions (meaning adverse effects on human health, such as death, disability, illness or disorders) caused by pathogenic micro-organisms that are transmitted in water. These diseases can be spread while bathing, washing ...

s such as

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

and

typhoid remained a risk.

From as early as 1535 there were efforts to stop polluting the

River Thames in

London. Beginning with an Act passed that year that was to prohibit the dumping of excrement into the river. Leading up to the Industrial Revolution the River Thames was identified as being thick and black due to sewage, and it was even said that the river “smells like death.” As Britain was the first country to industrialize, it was also the first to experience the disastrous consequences of major

urbanization and was the first to construct a modern sewerage system to mitigate the resultant unsanitary conditions.

[Abellán, Javier (2017)]

"Water supply and sanitation services in modern Europe: developments in 19th–20th centuries"

12th International Congress of the Spanish Association of Economic History: University of Salamanca, Spain. During the early 19th century, the River Thames was effectively an open sewer, leading to frequent outbreaks of

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemics. Proposals to modernize the sewerage system had been made during 1856 but were neglected due to lack of funds. However, after the ''

Great Stink

The Great Stink was an event in Central London during July and August 1858 in which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent that was present on the banks of the River Thames. The problem had been m ...

'' of 1858,

Parliament realized the urgency of the problem and resolved to create a modern sewerage system.

= Liverpool

=

However, ten years earlier and 200 miles to the north, James Newlands, a Scottish Engineer, was one of a celebrated trio of pioneering officers appointed under a private Act, the Liverpool Sanitory Act by the Borough of Liverpool Health of Towns Committee. The other officers appointed under the Act were William Henry Duncan, Medical Officer for Health, and Thomas Fresh, Inspector of Nuisances (an early antecedent of the environmental health officer). One of five applicants for the post, Newlands was appointed Borough Engineer of Liverpool on 26 January 1847.

He made a careful and exact survey of Liverpool and its surroundings, involving approximately 3,000 geodetical observations, and resulting in the construction of a contour map of the town and its neighbourhood, on a scale of one inch to 20 feet (6.1 m). From this elaborate survey Newlands proceeded to lay down a comprehensive system of outlet and contributory sewers, and main and subsidiary drains, to an aggregate extent of nearly 300 miles (480 km). The details of this projected system he presented to the Corporation in April 1848.

In July 1848 James Newlands' sewer construction programme began, and over the next 11 years 86 miles (138 km) of new sewers were built. Between 1856 and 1862 another 58 miles (93 km) were added. This programme was completed in 1869. Before the sewers were built, life expectancy in Liverpool was 19 years, and by the time Newlands retired it had more than doubled.

= London

=

Joseph Bazalgette

Sir Joseph William Bazalgette CB (; 28 March 181915 March 1891) was a 19th-century English civil engineer. As chief engineer of London's Metropolitan Board of Works, his major achievement was the creation (in response to the Great Stink of 1 ...

, a

civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

and Chief Engineer of the

Metropolitan Board of Works, was given responsibility for

similar work in London. He designed an extensive underground sewerage system that diverted waste to the

Thames Estuary, downstream of the main center of population. Six main interceptor sewers, totaling almost 100 miles (160 km) in length, were constructed, some incorporating stretches of

London's 'lost' rivers. Three of these sewers were north of the river, the southernmost, low-level one being incorporated in the

Thames Embankment. The Embankment also allowed new roads, new public gardens, and the

Circle Line of the

London Underground.

The intercepting sewers, constructed between 1859 and 1865, were fed by 450 miles (720 km) of main sewers that, in turn, conveyed the contents of some 13,000 miles (21,000 km) of smaller local sewers. Construction of the interceptor system required 318 million bricks, 2.7 million cubic metres of excavated earth and 670,000 cubic metres of

concrete.

Gravity allowed the sewage to flow eastwards, but in places such as

Chelsea,

Deptford and

Abbey Mills, pumping stations were built to raise the water and provide sufficient flow. Sewers north of the Thames feed into the

Northern Outfall Sewer, which fed into a major treatment works at

Beckton. South of the river, the

Southern Outfall Sewer

The Southern Outfall Sewer is a major sewer taking sewage from the southern area of central London to Crossness in south-east London. Flows from three interceptory sewers combine at a pumping station in Deptford and then run under Greenwich, ...

extended to a similar facility at

Crossness. With only minor modifications, Bazalgette's engineering achievement remains the basis for sewerage design up into the present day.

= other cities in the UK

=

In

Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydf ...

, a large town in

South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

, most houses discharged their sewage to individual

cess-pit

A cesspit (or cesspool or soak pit in some contexts) is a term with various meanings: it is used to describe either an underground holding tank (sealed at the bottom) or a soak pit (not sealed at the bottom). It can be used for the temporary co ...

s which persistently overflowed causing the pavements to be awash with foul sewage.

Paris, France

In 1802,

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

built the

Ourcq canal

The Canal de l'Ourcq is a long canal in the Île-de-France region (greater Paris) with 10 locks. It was built at a width of but was enlarged to 3.7 m (12 ft), which permitted use by more pleasure boats. The canal begins at Port-au ...

which brought 70,000 cubic meters of water a day to Paris, while the

Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributarie ...

river received up to of wastewater per day. The Paris cholera epidemic of 1832 sharpened the public awareness of the necessity for some sort of drainage system to deal with sewage and wastewater in a better and healthier way. Between 1865 and 1920

Eugene Belgrand lead the development of a large scale system for water supply and wastewater management. Between these years approximately 600 kilometers of aqueducts were built to bring in potable spring water, which freed the poor quality water to be used for flushing streets and sewers. By 1894 laws were passed which made drainage mandatory. The treatment of Paris sewage, though, was left to natural devices as 5,000 hectares of land were used to spread the waste out to be naturally purified.

Further, the lack of sewage treatment left Parisian sewage pollution to become concentrated downstream in the town of Clichy, effectively forcing residents to pack up and move elsewhere.

The 19th century brick-vaulted

Paris sewers serve as a tourist attraction nowadays.

Hamburg and Frankfurt, Germany

The first comprehensive sewer system in a German city was built in

Hamburg, Germany

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, in the mid-19th century.

[ Vol. I: Design of Sewers.]

In 1863, work began on the construction of a modern sewerage system for the rapidly growing city of

Frankfurt am Main, based on design work by

William Lindley

William Lindley (7 September 1808 in London – 22 May 1900 in Blackheath, London), was an English engineer who together with his sons designed water and sewerage systems for over 30 cities across Europe.

Life

As a young engineer he worked t ...

. 20 years after the system's completion, the

death rate from

typhoid had fallen from 80 to 10 per 100,000 inhabitants.

United States

The first sewer systems in the United States were built in the late 1850s in

Chicago and

Brooklyn.

In the United States, the first sewage treatment plant using

chemical precipitation was built in

Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1890.

Sewage treatment

Initially the gravity sewer systems discharged sewage directly to

surface water

Surface water is water located on top of land forming terrestrial (inland) waterbodies, and may also be referred to as ''blue water'', opposed to the seawater and waterbodies like the ocean.

The vast majority of surface water is produced by prec ...

s without treatment.

Later, cities attempted to treat the sewage before discharge in order to prevent

water pollution and

waterborne diseases. During the half-century around 1900, these

public health interventions succeeded in drastically reducing the incidence of water-borne diseases among the urban population, and were an important cause in the increases of

life expectancy experienced at the time.

Application on agricultural land

Early techniques for

sewage treatment involved land application of sewage on agricultural land.

One of the first attempts at diverting sewage for use as a fertilizer in the farm was made by the

cotton mill owner

James Smith in the 1840s. He experimented with a piped distribution system initially proposed by

James Vetch

James Vetch (1789–1869) was a Scottish army officer and civil engineer. A veteran of the Peninsular War in the Royal Engineers, in later life he took on a wide range of engineering work, including mining in Mexico. He was a Fellow of the Royal S ...

that collected sewage from his factory and pumped it into the outlying farms, and his success was enthusiastically followed by Edwin Chadwick and supported by organic chemist

Justus von Liebig

Justus Freiherr von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 20 April 1873) was a German scientist who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and is considered one of the principal founders of organic chemistry. As a professor at t ...

.

The idea was officially adopted by the

Health of Towns Commission, and various schemes (known as

sewage farms) were trialled by different municipalities over the next 50 years. At first, the heavier solids were channeled into ditches on the side of the farm and were covered over when full, but soon flat-bottomed tanks were employed as reservoirs for the sewage; the earliest patent was taken out by William Higgs in 1846 for "tanks or reservoirs in which the contents of sewers and drains from cities, towns and villages are to be collected and the solid animal or vegetable matters therein contained, solidified and dried..." Improvements to the design of the tanks included the introduction of the horizontal-flow tank in the 1850s and the radial-flow tank in 1905. These tanks had to be manually de-sludged periodically, until the introduction of automatic mechanical de-sludgers in the early 1900s.

Chemical treatment and sedimentation

As

pollution of water bodies became a concern, cities attempted to treat the sewage before discharge.

In the late 19th century some cities began to add chemical treatment and

sedimentation systems to their sewers.

In the United States, the first sewage treatment plant using

chemical precipitation was built in

Worcester, Massachusetts in 1890.

During the half-century around 1900, these

public health interventions succeeded in drastically reducing the incidence of water-borne diseases among the urban population, and were an important cause in the increases of

life expectancy experienced at the time.

Odor was considered the big problem in waste disposal and to address it, sewage could be drained to a

lagoon, or "settled" and the solids removed, to be disposed of separately. This process is now called "primary treatment" and the settled solids are called "sludge." At the end of the 19th century, since primary treatment still left odor problems, it was discovered that bad odors could be prevented by introducing oxygen into the decomposing sewage. This was the beginning of the biological aerobic and anaerobic treatments which are fundamental to wastewater processes.

The precursor to the modern

septic tank was the

cesspool in which the water was sealed off to prevent contamination and the solid waste was slowly liquified due to anaerobic action; it was invented by L.H Mouras in France in the 1860s. Donald Cameron, as

City Surveyor for

Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

patented an improved version in 1895, which he called a 'septic tank'; septic having the meaning of 'bacterial'. These are still in worldwide use, especially in rural areas unconnected to large-scale sewage systems.

Biological treatment

It was not until the late 19th century that it became possible to treat the sewage by biologically decomposing the organic components through the use of

microorganisms and removing the pollutants. Land treatment was also steadily becoming less feasible, as cities grew and the volume of sewage produced could no longer be absorbed by the farmland on the outskirts.

Edward Frankland conducted experiments at the sewage farm in

Croydon, England, during the 1870s and was able to demonstrate that filtration of sewage through porous gravel produced a nitrified effluent (the ammonia was converted into nitrate) and that the filter remained unclogged over long periods of time. This established the then revolutionary possibility of biological treatment of sewage using a contact bed to oxidize the waste. This concept was taken up by the chief chemist for the London

Metropolitan Board of Works, William Libdin, in 1887:

:...in all probability the true way of purifying sewage...will be first to separate the sludge, and then turn into neutral effluent... retain it for a sufficient period, during which time it should be fully aerated, and finally discharge it into the stream in a purified condition. This is indeed what is aimed at and imperfectly accomplished on a sewage farm.

From 1885 to 1891 filters working on this principle were constructed throughout the UK and the idea was also taken up in the US at the

Lawrence Experiment Station

The Lawrence Experiment Station, now known as the Senator William X. Wall Experiment Station, was the world's first trial station for drinking water purification and sewage treatment. It was established in 1887 in Lawrence, Massachusetts. A new, ...

in

Massachusetts, where Frankland's work was confirmed. In 1890 the LES developed a '

trickling filter' that gave a much more reliable performance.

Contact beds were developed in

Salford,

Lancashire and by scientists working for the

London City Council in the early 1890s. According to Christopher Hamlin, this was part of a conceptual revolution that replaced the philosophy that saw "sewage purification as the prevention of decomposition with one that tried to facilitate the biological process that destroy sewage naturally."

Contact beds were tanks containing an inert substance, such as stones or slate, that maximized the surface area available for the microbial growth to break down the sewage. The sewage was held in the tank until it was fully decomposed and it was then filtered out into the ground. This method quickly became widespread, especially in the UK, where it was used in

Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

,

Sheffield,

Manchester and

Leeds. The bacterial bed was simultaneously developed by Joseph Corbett as Borough Engineer in

Salford and experiments in 1905 showed that his method was superior in that greater volumes of sewage could be purified better for longer periods of time than could be achieved by the contact bed.

The Royal Commission on Sewage Disposal published its eighth report in 1912 that set what became the international standard for sewage discharge into rivers; the '20:30 standard', which allowed "''2 parts per hundred thousand"'' of

Biochemical oxygen demand and ''"3 parts per hundred thousand"'' of suspended solid.

=Activated sludge process

=

Most cities in the Western world added more effective systems for sewage treatment in the early 20th century, after scientists at the

University of Manchester discovered the sewage treatment process of

activated sludge in 1912.

Toilets

With the onset of the

Industrial Revolution and related advances in technology, the

flush toilet began to emerge into its modern form in the late 18th century, (''See''

Development of the modern flush toilet.) In urban areas, toilets are typically connected to a municipal

sanitary sewer system, while in more rural areas they are usually connected to an

onsite sewage facility (septic system). Where this is not feasible or desired,

dry toilets are an alternative option.

Water supply

An ambitious engineering project to bring fresh water from

Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

to

London was undertaken by

Hugh Myddleton, who oversaw the construction of the

New River between 1609 and 1613. The

New River Company became one of the largest private water companies of the time, supplying the

City of London and other central areas.

The first civic system of piped water in England was established in

Derby in 1692, using wooden pipes, which was common for several centuries. The Derby Waterworks included waterwheel-powered pumps for raising water out of the

River Derwent and storage tanks for distribution.

It was in the 18th century that a rapidly growing population fueled a boom in the establishment of private water supply networks in

London. The

Chelsea Waterworks Company was established in 1723 "for the better supplying the

City

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

and

Liberties of

Westminster and parts adjacent with water".

[''The London Encyclopaedia'', Ben Weinreb & Christopher Hibbert, Macmillan, 1995, ] The company created extensive ponds in the area bordering

Chelsea and

Pimlico

Pimlico () is an area of Central London in the City of Westminster, built as a southern extension to neighbouring Belgravia. It is known for its garden squares and distinctive Regency architecture. Pimlico is demarcated to the north by London V ...

using water from the

tidal Thames. Other waterworks were established in London, including at

West Ham in 1743, at

Lea Bridge

Lea Bridge is a district in the London Borough of Hackney and the London Borough of Waltham Forest in London, England. It lies 7 miles (11.3 km) northeast of Charing Cross.

The area it takes its name from a bridge built over the River ...

before 1767,

Lambeth Waterworks Company in 1785,

West Middlesex Waterworks Company

The West Middlesex Waterworks Company was a utility company supplying water to parts of west London in England. The company was established in 1806 with works at Hammersmith and became part of the publicly owned Metropolitan Water Board in 1904 ...

in 1806 and

Grand Junction Waterworks Company

The Grand Junction Waterworks Company was a utility company supplying water to parts of west London in England. The company was formed as an offshoot of the Grand Junction Canal Company in 1811 and became part of the publicly owned Metropoli ...

in 1811.

The

S-bend

In plumbing, a trap is a U-shaped portion of pipe designed to trap liquid or gas to prevent unwanted flow; most notably sewer gases from entering buildings while allowing waste materials to pass through. In oil refineries, traps are used to p ...

pipe was invented by

Alexander Cummings in 1775 but became known as the U-bend following the introduction of the U-shaped trap by

Thomas Crapper in 1880. The first screw-down

water tap was patented in 1845 by Guest and Chrimes, a brass foundry in

Rotherham.

Water treatment

Sand filter

Sir

Francis Bacon attempted to

desalinate

Desalination is a process that takes away mineral components from saline water. More generally, desalination refers to the removal of salts and minerals from a target substance, as in soil desalination, which is an issue for agriculture. Saltwa ...

sea water by passing the flow through a

sand filter. Although his experiment did not succeed, it marked the beginning of a new interest in the field.

The first documented use of

sand filters to purify the water supply dates to 1804, when the owner of a bleachery in

Paisley, Scotland, John Gibb, installed an experimental filter, selling his unwanted surplus to the public.

This method was refined in the following two decades by engineers working for private water companies, and it culminated in the first treated public water supply in the world, installed by engineer

James Simpson for the

Chelsea Waterworks Company in London in 1829.

This installation provided filtered water for every resident of the area, and the network design was widely copied throughout the

United Kingdom in the ensuing decades.

The

Metropolis Water Act introduced the regulation of the

water supply companies in

London, including minimum standards of water quality for the first time. The Act "made provision for securing the supply to the Metropolis of pure and wholesome water", and required that all water be "effectually filtered" from 31 December 1855. This was followed up with legislation for the mandatory inspection of water quality, including comprehensive chemical analyses, in 1858. This legislation set a worldwide precedent for similar state public health interventions across

Europe. The

Metropolitan Commission of Sewers was formed at the same time, water filtration was adopted throughout the country, and new water intakes on the

Thames were established above

Teddington Lock. Automatic pressure filters, where the water is forced under pressure through the filtration system, were innovated in 1899 in England.

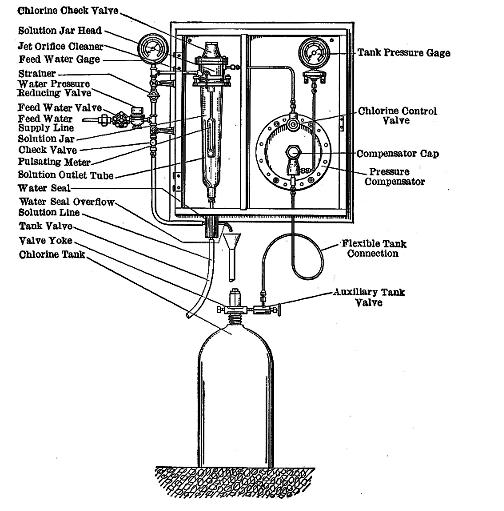

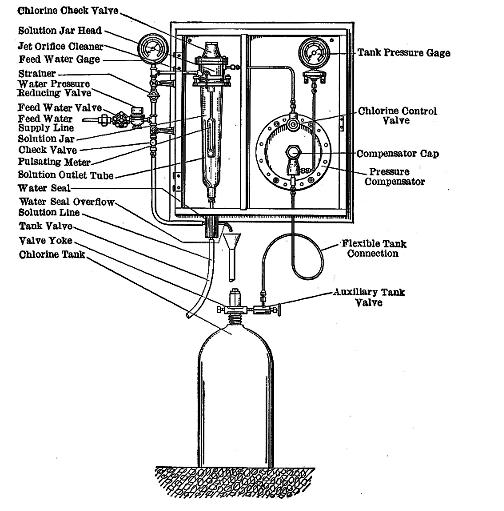

Water chlorination

In what may have been one of the first attempts to use chlorine, William Soper used chlorinated lime to treat the sewage produced by

typhoid patients in 1879.

In a paper published in 1894,

Moritz Traube

Moritz Traube (12 February 1826 in Ratibor, Province of Silesia, Prussia (now Racibórz, Poland) – 28 June 1894 in Berlin, German Empire) was a German chemist (physiological chemistry) and universal private scholar.

Traube worked on chemical, ...

formally proposed the addition of chloride of lime (

calcium hypochlorite

Calcium hypochlorite is an inorganic compound with formula Ca(OCl)2. It is the main active ingredient of commercial products called bleaching powder, chlorine powder, or chlorinated lime, used for water treatment and as a bleaching agent. Thi ...

) to water to render it "germ-free." Two other investigators confirmed Traube's findings and published their papers in 1895. Early attempts at implementing water chlorination at a water treatment plant were made in 1893 in

Hamburg,

Germany, and in 1897 the town of

Maidstone, in

Kent,

England, was the first to have its entire water supply treated with chlorine.

Permanent water chlorination began in 1905, when a faulty

slow sand filter and a contaminated water supply led to a serious typhoid fever epidemic in

Lincoln, England

Lincoln () is a cathedral city, a non-metropolitan district, and the county town of Lincolnshire, England. In the 2021 Census, the Lincoln district had a population of 103,813. The 2011 census gave the Lincoln Urban Area, urban area of Lincoln, ...

. Dr. Alexander Cruickshank Houston used chlorination of the water to stem the epidemic. His installation fed a concentrated solution of chloride of lime to the water being treated. The chlorination of the water supply helped stop the epidemic and as a precaution, the chlorination was continued until 1911 when a new water supply was instituted.

The first continuous use of chlorine in the

United States for disinfection took place in 1908 at Boonton Reservoir (on the

Rockaway River

The Rockaway River is a tributary of the Passaic River, approximately 35 mi (56 km) long, in northern New Jersey in the United States. The upper course of the river flows through a wooded mountainous valley, whereas the lower course flo ...

), which served as the supply for

Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.[calcium hypochlorite

Calcium hypochlorite is an inorganic compound with formula Ca(OCl)2. It is the main active ingredient of commercial products called bleaching powder, chlorine powder, or chlorinated lime, used for water treatment and as a bleaching agent. Thi ...]

) at doses of 0.2 to 0.35 ppm. The treatment process was conceived by Dr. John L. Leal and the chlorination plant was designed by

George Warren Fuller. Over the next few years, chlorine disinfection using chloride of lime were rapidly installed in drinking water systems around the world.

The technique of purification of drinking water by use of compressed liquefied chlorine gas was developed by a British officer in the

Indian Medical Service, Vincent B. Nesfield, in 1903. According to his own account, "It occurred to me that chlorine gas might be found satisfactory ... if suitable means could be found for using it.... The next important question was how to render the gas portable. This might be accomplished in two ways: By liquefying it, and storing it in lead-lined iron vessels, having a jet with a very fine capillary canal, and fitted with a tap or a screw cap. The tap is turned on, and the cylinder placed in the amount of water required. The chlorine bubbles out, and in ten to fifteen minutes the water is absolutely safe. This method would be of use on a large scale, as for service water carts."

U.S. Army Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Carl Rogers Darnall

Brigadier General Carl Rogers Darnall (December 25, 1867 in Weston, Texas – January 18, 1941 in Washington, D.C.) was a United States Army chemist and surgeon credited with originating the technique of liquid chlorination of drinking wate ...

, Professor of Chemistry at the

Army Medical School

Founded by U.S. Army Brigadier General George Miller Sternberg, MD in 1893, the Army Medical School (AMS) was by some reckonings the world's first school of public health and preventive medicine. (The other institution vying for this distinction ...

, gave the first practical demonstration of this in 1910. Shortly thereafter, Major William J. L. Lyster of the

Army Medical Department used a solution of

calcium hypochlorite

Calcium hypochlorite is an inorganic compound with formula Ca(OCl)2. It is the main active ingredient of commercial products called bleaching powder, chlorine powder, or chlorinated lime, used for water treatment and as a bleaching agent. Thi ...

in a linen bag to treat water. For many decades, Lyster's method remained the standard for U.S. ground forces in the field and in camps, implemented in the form of the familiar Lyster Bag (also spelled Lister Bag). This work became the basis for present day systems of municipal water purification.

Fluoridation

Water fluoridation is a practice adding fluoride to drinking water for the purpose of decreasing

tooth decay.

The architect of these first fluoride studies was Dr. H. Trendley Dean, head of the Dental Hygiene Unit at the National Institute of Health (NIH). Dean began investigating the epidemiology of fluorosis in 1931. By the late 1930s, he and his staff had made a critical discovery. Namely, fluoride levels of up to 1.0 ppm in drinking water did not cause enamel fluorosis in most people and only mild enamel fluorosis in a small percentage of people. Proof That Fluoride Prevents Caries This finding sent Dean's thoughts spiraling in a new direction. He recalled from reading McKay's and Black's studies on fluorosis that mottled tooth enamel is unusually resistant to decay. Dean wondered whether adding fluoride to drinking water at physically and cosmetically safe levels would help fight tooth decay. This hypothesis, Dean told his colleagues, would need to be tested. In 1944, Dean got his wish. That year, the City Commission of Grand Rapids, Michigan-after numerous discussions with researchers from the PHS, the Michigan Department of Health, and other public health organizations-voted to add fluoride to its public water supply the following year. In 1945, Grand Rapids became the first city in the world to fluoridate its drinking water. The Grand Rapids water fluoridation study was originally sponsored by the U.S. Surgeon General, but was taken over by the NIDR shortly after the institute's inception in 1948.

Trends

The

Sustainable Development Goal 6

Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6 or Global Goal 6) is about "clean water and sanitation for all". It is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, the official wording is: "Ensure ava ...

formulated in 2015 includes targets on access to water supply and sanitation at a global level. In

developing countries,

self-supply of water and sanitation

Self-supply of water and sanitation (also called household-led water supply or individual supply) refers to an approach of incremental improvements to water and sanitation services, which are mainly financed by the user. People around the world h ...

is used as an approach of incremental improvements to water and sanitation services, which are mainly financed by the user.

Decentralized wastewater systems are also growing in importance to achieve

sustainable sanitation

Sustainable sanitation is a sanitation system designed to meet certain criteria and to work well over the long-term. Sustainable sanitation systems consider the entire "sanitation value chain", from the experience of the user, Human excreta, exc ...

.

Understanding of health aspects

The Greek historian

Thucydides (

c. 460 –

c. 400 BC) was the first person to write, in his account of the

plague of Athens, that diseases could spread from an infected person to others.

The Mosaic Law, within the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, contains the earliest recorded thoughts of contagion in the spread of disease. Specifically, it presents instructions on quarantine and washing in relation to leprosy and venereal disease

One theory of the spread of contagious diseases that were not spread by direct contact was that they were spread by

spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, f ...

-like "seeds" (

Latin: ''semina'') that were present in and dispersible through the air. In his poem, ''

De rerum natura

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7 ...

'' (On the Nature of Things, c. 56 BC), the Roman poet

Lucretius (

c. 99 BC –

c. 55 BC) stated that the world contained various "seeds", some of which could sicken a person if they were inhaled or ingested.

The Roman statesman

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) wrote, in his ''Rerum rusticarum libri III'' (Three Books on Agriculture, 36 BC): "Precautions must also be taken in the neighborhood of swamps ... because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases."

The Greek physician Galen (AD 129 –

c. 200/216) speculated in his ''On Initial Causes'' (

c. 175 AD that some patients might have "seeds of fever". In his ''On the Different Types of Fever'' (

c. 175 AD), Galen speculated that plagues were spread by "certain seeds of plague", which were present in the air. And in his ''Epidemics'' (

c. 176–178 AD), Galen explained that patients might relapse during recovery from fever because some "seed of the disease" lurked in their bodies, which would cause a recurrence of the disease if the patients did not follow a physician's therapeutic regimen.

The

fiqh scholar

Ibn al-Haj al-Abdari

Moḥammed ibn al-Hajj al-Abdari al-Fasi (or Mohammed Ibn Mohammed ibn Mohammed Abu Abdallah Ibn al-Hajj al-Abdari al-Maliki al-Fassi; ar, إبن الحاج العبدري الفاسي) also known simply as Ibn al-Haj or Ibn al-Hajj was a Morocca ...

(c. 1250–1336), while discussing

Islamic diet and hygiene, gave advice and warnings about impurities that contaminate water, food, and garments, and could spread through the water supply.

Long before studies had established the

germ theory of disease, or any advanced understanding of the nature of water as a vehicle for transmitting disease, traditional beliefs had cautioned against the consumption of water, rather favoring processed beverages such as

beer,

wine and

tea. For example, in the

camel caravans that crossed

Central Asia along the

Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

, the explorer

Owen Lattimore noted, "The reason we drank so much tea was because of the bad water. Water alone, unboiled, is never drunk. There is a superstition that it causes blisters on the feet."

One of the earliest understandings of waterborne diseases in Europe arose during the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution took over Europe.

, such as

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, were once wrongly explained by the

miasma theory

The miasma theory (also called the miasmatic theory) is an obsolete medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or the Black Death—were caused by a ''miasma'' (, Ancient Greek for 'pollution'), a noxious form of "bad ...

, the theory that bad air causes the spread of diseases.

However, people started to find a correlation between

water quality and waterborne diseases, which led to different

water purification methods, such as

sand filtering and

chlorinating their drinking water.

Founders of

microscopy

Microscopy is the technical field of using microscopes to view objects and areas of objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye (objects that are not within the resolution range of the normal eye). There are three well-known branches of micr ...

,

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek ( ; ; 24 October 1632 – 26 August 1723) was a Dutch microbiologist and microscopist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology. A largely self-taught man in science, he is commonly known as " the ...

and

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, used the newly invented

microscope to observe for the first time small material particles that were suspended in the water, laying the groundwork for the future understanding of waterborne pathogens and

waterborne diseases.

In the 19th century, Britain was the center for rapid

urbanization, and as a result, many health and sanitation problems manifested, for example

cholera outbreaks and pandemics

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organizat ...

. This resulted in Britain playing a large role in the development for public health.

Before discovering the link between contaminated drinking water and diseases, such as cholera and other waterborne diseases, the

miasma theory