A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held

captive

Captive or Captives may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Captive'' (1980 film), a sci-fi film, starring Cameron Mitchell and David Ladd

* ''Captive'' (1986 film), a British-French film starring Oliver Reed

* ''Captive'' (1991 ...

by a

belligerent power during or immediately after an

armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war in custody for a range of legitimate and illegitimate reasons, such as isolating them from the enemy

combatants still in the field (releasing and

repatriating them in an orderly manner after hostilities), demonstrating military victory, punishing them, prosecuting them for

war crimes,

exploiting them for their labour, recruiting or even

conscripting them as their own combatants, collecting military and political intelligence from them, or

indoctrinating them in new political or religious beliefs.

Ancient times

For most of human history, depending on the culture of the victors, enemy fighters on the losing side in a battle who had surrendered and been taken as prisoners of war could expect to be either slaughtered or

enslaved. Early Roman

gladiators could be prisoners of war, categorised according to their ethnic roots as

Samnites,

Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

, and

Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

(''Galli''). Homer's ''

Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' describes Greek and Trojan soldiers offering rewards of wealth to opposing forces who have defeated them on the battlefield in exchange for mercy, but their offers are not always accepted; see

Lycaon for example.

Typically, victors made little distinction between enemy combatants and enemy civilians, although they were more likely to spare women and children. Sometimes the purpose of a battle, if not of a war, was to capture women, a practice known as ''

raptio

''Raptio'' (in archaic or literary English rendered as ''rape'') is a Latin term for the large-scale abduction of women, i.e. kidnapping for marriage, concubinage or sexual slavery. The equivalent German term is ''Frauenraub'' (literally '' ...

''; the

Rape of the Sabines

The Rape of the Sabine Women ( ), also known as the Abduction of the Sabine Women or the Kidnapping of the Sabine Women, was an incident in Roman mythology in which the men of Rome committed a mass abduction of young women from the other citi ...

involved, according to tradition, a large mass-abduction by the founders of Rome. Typically women had no

rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory ...

, and were held legally as

chattels.

In the fourth century AD, Bishop

Acacius of Amida

Acacius of Amida (died 425) was bishop of Amida, Mesopotamia (modern-day Turkey) from 400 to 425, during the reign of the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II. He has no extant writings, but his life is documented by Socrates Scholasticus, in th ...

, touched by the plight of Persian prisoners captured in a recent war with the Roman Empire, who were held in his town under appalling conditions and destined for a life of slavery, took the initiative in ransoming them by selling his church's precious gold and silver vessels and letting them return to their country. For this he was eventually

canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

According to legend, during

Childeric's siege and blockade of

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

in 464 the nun

Geneviève

Genevieve (french: link=no, Sainte Geneviève; la, Sancta Genovefa, Genoveva; 419/422 AD –

502/512 AD) is the patroness saint of Paris in the Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Her feast is on 3 January.

Genevieve was born in Nanterre an ...

(later canonised as the city's patron saint) pleaded with the Frankish king for the welfare of prisoners of war and met with a favourable response. Later,

Clovis I () liberated captives after Genevieve urged him to do so.

[Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. ''The Penguin Dictionary of Saints''. 3rd edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. .]

King

Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1 ...

's English army killed many French prisoners of war after the

Battle of Agincourt in 1415. This was done in retaliation for the French killing of the boys and other non-combatants handling the baggage and equipment of the army, and because the French were attacking again and Henry was afraid that they would break through and free the prisoners to fight again.

In the later

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

a number of

religious war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

s aimed to not only defeat but also to eliminate enemies. Authorities in

Christian Europe

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

often considered the extermination of

heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

and

heathens desirable. Examples of such wars include the 13th-century

Albigensian Crusade in

Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (; , ; oc, Lengadòc ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately ...

and the

Northern Crusades

The Northern Crusades or Baltic Crusades were Christian colonization and Christianization campaigns undertaken by Catholic Christian military orders and kingdoms, primarily against the pagan Baltic, Finnic and West Slavic peoples around th ...

in the

Baltic region. When asked by a Crusader how to distinguish between the Catholics and

Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. F ...

following the projected capture (1209) of the city of

Béziers, the papal legate

Arnaud Amalric allegedly replied, "

Kill them all, God will know His own".

Likewise, the inhabitants of conquered cities were frequently massacred during Christians'

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

against

Muslims in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Noblemen

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characterist ...

could hope to be

ransomed; their families would have to send to their captors large sums of wealth commensurate with the social status of the captive.

Feudal Japan

The first human inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago have been traced to prehistoric times around 30,000 BC. The Jōmon period, named after its cord-marked pottery, was followed by the Yayoi period in the first millennium BC when new inve ...

had no custom of ransoming prisoners of war, who could expect for the most part summary execution.

In the 13th century the expanding

Mongol Empire famously distinguished between cities or towns that surrendered (where the population was spared but required to support the conquering Mongol army) and those that resisted (in which case the city was

ransacked and destroyed, and all the population killed). In

Termez

Termez ( uz, Termiz/Термиз; fa, ترمذ ''Termez, Tirmiz''; ar, ترمذ ''Tirmidh''; russian: Термез; Ancient Greek: ''Tàrmita'', ''Thàrmis'', ) is the capital of Surxondaryo Region in southern Uzbekistan. Administratively, it i ...

, on the

Oxus

The Amu Darya, tk, Amyderýa/ uz, Amudaryo// tg, Амударё, Amudaryo ps, , tr, Ceyhun / Amu Derya grc, Ὦξος, Ôxos (also called the Amu, Amo River and historically known by its Latin name or Greek ) is a major river in Central Asi ...

: "all the people, both men and women, were driven out onto the plain, and divided in accordance with their usual custom, then they were all slain".

The

Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl ...

s

warred constantly with neighbouring tribes and groups, aiming to collect live prisoners for

sacrifice. For the re-consecration of

Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed.

During the

early Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of 622–750, Muslims routinely captured large numbers of prisoners. Aside from those who converted, most were ransomed or

enslaved. Christians captured during the Crusades were usually either killed or sold into slavery if they could not pay a ransom. During his lifetime ( – 632),

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

made it the responsibility of the Islamic government to provide food and clothing, on a reasonable basis, to captives, regardless of their religion; however, if the prisoners were in the custody of a person, then the responsibility was on the individual. The freeing of prisoners was highly recommended as a charitable act.

On certain occasions where Muhammad felt the enemy had broken a treaty with the Muslims he endorsed the mass execution of male prisoners who participated in battles, as in the case of the

Banu Qurayza

The Banu Qurayza ( ar, بنو قريظة, he, בני קוריט'ה; alternate spellings include Quraiza, Qurayzah, Quraytha, and the archaic Koreiza) were a Jewish tribe which lived in northern Arabia, at the oasis of Yathrib (now known as ...

in 627. The Muslims divided up the females and children of those executed as ''ghanima'' (spoils of war).

Modern times

In Europe, the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly centralized, in the time period between the 16th and late 18th century. Whereas prisoners of war had previously been regarded as the private property of the captor, captured enemy soldiers became increasingly regarded as the property of the state. The European states strove to exert increasing control over all stages of captivity, from the question of who would be attributed the status of prisoner of war to their eventual release. The act of surrender was regulated so that it, ideally, should be legitimized by officers, who negotiated the surrender of their whole unit. Soldiers whose style of fighting did not conform to the battle line tactics of regular European armies, such as

Cossacks and Croats, were often denied the status of prisoners of war.

In line with this development the treatment of prisoners of war became increasingly regulated in interactional treaties, particularly in the form of the so-called cartel system, which regulated how the exchange of prisoners would be carried out between warring states. Another such treaty was the 1648

Peace of Westphalia, which ended the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

. This treaty established the rule that prisoners of war should be released without ransom at the end of hostilities and that they should be allowed to return to their homelands.

There also evolved the

right of ''parole'', French for "discourse", in which a captured officer surrendered his sword and gave his word as a gentleman in exchange for privileges. If he swore not to escape, he could gain better accommodations and the freedom of the prison. If he swore to cease hostilities against the nation who held him captive, he could be repatriated or exchanged but could not serve against his former captors in a military capacity.

European settlers captured in North America

Early historical narratives of captured European settlers, including perspectives of literate women captured by the

indigenous peoples of North America

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the Am ...

, exist in some number. The writings of

Mary Rowlandson

Mary Rowlandson, née White, later Mary Talcott (c. 1637January 5, 1711), was a colonial American woman who was captured by Native Americans in 1676 during King Philip's War and held for 11 weeks before being ransomed. In 1682, six years after h ...

, captured in the chaotic fighting of

King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

, are an example. Such narratives enjoyed some popularity, spawning a genre of the

captivity narrative

Captivity narratives are usually stories of people captured by enemies whom they consider uncivilized, or whose beliefs and customs they oppose. The best-known captivity narratives in North America are those concerning Europeans and Americans ta ...

, and had lasting influence on the body of early American literature, most notably through the legacy of

James Fenimore Cooper's ''

The Last of the Mohicans

''The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757'' is a historical romance written by James Fenimore Cooper in 1826.

It is the second book of the ''Leatherstocking Tales'' pentalogy and the best known to contemporary audiences. '' The Pathfinder ...

''. Some Native Americans continued to capture Europeans and use them both as labourers and bargaining chips into the 19th century; see for example

John R. Jewitt

John Rodgers Jewitt (21 May 1783 – 7 January 1821) was an English armourer who entered the historical record with his memoirs about the 28 months he spent as a captive of Maquinna of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people on what is now the Britis ...

, a sailor who wrote a memoir about his years as a captive of the

Nootka people on the

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Tho ...

coast from 1802 to 1805.

French Revolutionary wars and Napoleonic wars

The earliest known purpose-built

prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. ...

was established at

Norman Cross

Norman Cross Prison in Huntingdonshire, England, was the world's first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp or "depot", built in 1796–97 to hold prisoners of war from France and its allies during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic War ...

in Huntingdonshire, England in 1797 to house the increasing number of prisoners from the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

and the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. The average prison population was about 5,500 men. The lowest number recorded was 3,300 in October 1804 and 6,272 on 10 April 1810 was the highest number of prisoners recorded in any official document.

Norman Cross Prison

Norman Cross Prison in Huntingdonshire, England, was the world's first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp or "depot", built in 1796–97 to hold prisoners of war from France and its allies during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wa ...

was intended to be a model depot providing the most humane treatment of prisoners of war. The British government went to great lengths to provide food of a quality at least equal to that available to locals. The senior officer from each quadrangle was permitted to inspect the food as it was delivered to the prison to ensure it was of sufficient quality. Despite the generous supply and quality of food, some prisoners died of starvation after gambling away their rations. Most of the men held in the prison were low-ranking soldiers and sailors, including midshipmen and junior officers, with a small number of

privateers. About 100 senior officers and some civilians "of good social standing", mainly passengers on captured ships and the wives of some officers, were given ''parole'' outside the prison, mainly in

Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

although some further afield. They were afforded the courtesy of their rank within English society.

During the

Battle of Leipzig both sides used the

city's cemetery as a

lazaret

A lazaretto or lazaret (from it, lazzaretto a diminutive form of the Italian word for beggar cf. lazzaro) is a quarantine station for maritime travellers. Lazarets can be ships permanently at anchor, isolated islands, or mainland buildings. ...

and prisoner camp for around 6,000 POWs who lived in the

burial vaults

A burial vault (also known as a burial liner, grave vault, and grave liner) is a container, formerly made of wood or brick but more often today made of metal or concrete, that encloses a coffin to help prevent a grave from sinking. Wooden coffin ...

and used the coffins for firewood. Food was scarce and prisoners resorted to eating horses, cats, dogs or even human flesh. The bad conditions inside the graveyard contributed to a city-wide epidemic after the battle.

Prisoner exchanges

The extensive period of conflict during the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

and

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

(1793–1815), followed by the

Anglo-American

Anglo-Americans are people who are English-speaking inhabitants of Anglo-America. It typically refers to the nations and ethnic groups in the Americas that speak English as a native language, making up the majority of people in the world who spe ...

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, led to the emergence of a

cartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collude with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. Cartels are usually associations in the same sphere of business, and thus an alliance of rivals. Mos ...

system for the

exchange of prisoners, even while the belligerents were at war. A cartel was usually arranged by the respective armed service for the exchange of like-ranked personnel. The aim was to achieve a reduction in the number of prisoners held, while at the same time alleviating shortages of skilled personnel in the home country.

American Civil War

At the start of the American Civil War a system of paroles operated. Captives agreed not to fight until they were officially exchanged. Meanwhile, they were held in camps run by their own army where they were paid but not allowed to perform any military duties. The system of exchanges collapsed in 1863 when the Confederacy refused to exchange black prisoners. In the late summer of 1864, a year after the

Dix–Hill Cartel

The Dix–Hill Cartel was the first official system for exchanging prisoners during the American Civil War. It was signed by Union Major General John A. Dix and Confederate Major General D. H. Hill at Haxall's Landing on the James River in Vi ...

was suspended, Confederate officials approached Union General Benjamin Butler, Union Commissioner of Exchange, about resuming the cartel and including the black prisoners. Butler contacted Grant for guidance on the issue, and Grant responded to Butler on 18 August 1864 with his now famous statement. He rejected the offer, stating in essence, that the Union could afford to leave their men in captivity, the Confederacy could not. After that about 56,000 of the 409,000 POWs died in prisons during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, accounting for nearly 10% of the conflict's fatalities. Of the 45,000 Union prisoners of war confined in

Camp Sumter, located near

Andersonville, Georgia

Andersonville is a city in Sumter County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 237. It is located in the southwest part of the state, approximately southwest of Macon on the Central of Georgia railroad. ...

, 13,000 (28%) died. At

Camp Douglas in Chicago, Illinois, 10% of its Confederate prisoners died during one cold winter month; and

Elmira Prison

Elmira Prison was originally a barracks for "Camp Rathbun" or "Camp Chemung", a key muster and training point for the Union Army during the American Civil War, between 1861 and 1864. The site was selected partially due to its proximity to the E ...

in New York state, with a death rate of 25% (2,963), nearly equalled that of Andersonville.

Amelioration

During the 19th century, there were increased efforts to improve the treatment and processing of prisoners. As a result of these emerging conventions, a number of international conferences were held, starting with the Brussels Conference of 1874, with nations agreeing that it was necessary to prevent inhumane treatment of prisoners and the use of weapons causing unnecessary harm. Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, work was continued that resulted in new

conventions being adopted and becoming recognized as

international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

that specified that prisoners of war be treated humanely and diplomatically.

Hague and Geneva Conventions

Chapter II of the Annex to the

1907 Hague Convention ''IV – The Laws and Customs of War on Land'' covered the treatment of prisoners of war in detail. These provisions were further expanded in the

1929 Geneva Convention on the Prisoners of War and were largely revised in the

Third Geneva Convention

The Third Geneva Convention, relative to the treatment of prisoners of war, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was first adopted in 1929, but significant ...

in 1949.

Article 4 of the

Third Geneva Convention

The Third Geneva Convention, relative to the treatment of prisoners of war, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was first adopted in 1929, but significant ...

protects captured

military personnel

Military personnel are members of the state's armed forces. Their roles, pay, and obligations differ according to their military branch (army, navy, marines, air force, space force, and coast guard), rank (officer, non-commissioned officer, or ...

, some

guerrilla fighters, and certain

civilians

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not " combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant ...

. It applies from the moment a prisoner is captured until their release or repatriation. One of the main provisions of the convention makes it illegal to

torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. definitions of tortur ...

prisoners and states that a prisoner can only be required to give their

name,

date of birth

A birthday is the anniversary of the birth of a person, or figuratively of an institution. Birthdays of people are celebrated in numerous cultures, often with birthday gifts, birthday cards, a birthday party, or a rite of passage.

Many re ...

,

rank

Rank is the relative position, value, worth, complexity, power, importance, authority, level, etc. of a person or object within a ranking, such as:

Level or position in a hierarchical organization

* Academic rank

* Diplomatic rank

* Hierarchy

* ...

and

service number

A service number is an identification code used to identify a person within a large group. Service numbers are most often associated with the military; however, they may be used in civilian organizations as well. National identification numbers may ...

(if applicable).

The

ICRC

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

has a special role to play, with regards to

international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pro ...

, in

restoring and maintaining family contact in times of war, in particular concerning the right of prisoners of war and internees to send and receive letters and cards (Geneva Convention (GC) III, art.71 and GC IV, art.107).

However, nations vary in their dedication to following these laws, and historically the treatment of POWs has varied greatly. During World War II,

Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

and

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

(towards Soviet POWs and Western Allied commandos) were notorious for atrocities against prisoners of war. The German military used the Soviet Union's refusal to sign the Geneva Convention as a reason for not providing the necessities of life to Soviet POWs; and the Soviets also used Axis prisoners as forced labour. The Germans also routinely executed Allied commandos captured behind German lines per the

Commando Order.

Qualifications

To be entitled to prisoner-of-war status, captured persons must be

lawful combatant

Combatant is the legal status of an individual who has the right to engage in hostilities during an armed conflict. The legal definition of "combatant" is found at article 43(2) of Additional Protocol I (AP1) to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. It ...

s entitled to combatant's privilege—which gives them immunity from punishment for crimes constituting lawful acts of war such as killing

enemy combatant

Enemy combatant is a person who, either lawfully or unlawfully, engages in hostilities for the other side in an armed conflict. Usually enemy combatants are members of the armed forces of the state with which another state is at war. In the case ...

s. To qualify under the

Third Geneva Convention

The Third Geneva Convention, relative to the treatment of prisoners of war, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was first adopted in 1929, but significant ...

, a combatant must be part of a

chain of command

A command hierarchy is a group of people who carry out orders based on others' authority within the group. It can be viewed as part of a power structure, in which it is usually seen as the most vulnerable and also the most powerful part.

Milit ...

, wear a "fixed distinctive marking, visible from a distance", bear arms openly, and have conducted military operations according to the

laws and customs of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territor ...

. (The Convention recognizes a few other groups as well, such as "

habitants of a non-occupied territory, who on the approach of the enemy spontaneously take up arms to resist the invading forces, without having had time to form themselves into regular armed units".)

Thus, uniforms and badges are important in determining prisoner-of-war status under the Third Geneva Convention. Under

Additional Protocol I, the requirement of a distinctive marking is no longer included. ''

Francs-tireurs

(, French for "free shooters") were irregular military formations deployed by France during the early stages of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). The term was revived and used by partisans to name two major French Resistance movements set ...

'',

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s,

insurgents,

terrorists

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

,

saboteurs

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identiti ...

,

mercenaries, and

spies

Spies most commonly refers to people who engage in spying, espionage or clandestine operations.

Spies or The Spies may also refer to:

* Spies (surname), a German surname

* Spies (band), a jazz fusion band

* Spies (song), "Spies" (song), a song by ...

generally do not qualify because they do not fulfill the criteria of Additional Protocol 1. Therefore, they fall under the category of

unlawful combatant

An unlawful combatant, illegal combatant or unprivileged combatant/belligerent is a person who directly engages in armed conflict in violation of the laws of war and therefore is claimed not to be protected by the Geneva Conventions.

The Internat ...

s, or more properly they are not combatants. Captured soldiers who do not get prisoner of war status are still protected like civilians under the

Fourth Geneva Convention.

The criteria are applied primarily to ''international'' armed conflicts. The application of prisoner of war status in non-international armed conflicts like

civil wars

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

is guided by

Additional Protocol II, but

insurgents

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irr ...

are often treated as

traitors,

terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

s or

criminals

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Can ...

by government forces and are sometimes executed on spot or tortured. However, in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, both sides treated captured troops as POWs presumably out of

reciprocity, although the

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

regarded

Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

personnel as separatist rebels. However, guerrillas and other irregular combatants generally cannot expect to receive benefits from both civilian and military status simultaneously.

Rights

Under the

Third Geneva Convention

The Third Geneva Convention, relative to the treatment of prisoners of war, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was first adopted in 1929, but significant ...

, prisoners of war (POW) must be:

* Treated humanely with respect for their persons and their honor

* Able to inform their next of kin and the

International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

of their capture

* Allowed to communicate regularly with relatives and receive packages

* Given adequate food, clothing, housing, and medical attention

* Paid for work done and not forced to do work that is dangerous, unhealthy, or degrading

* Released quickly after conflicts end

* Not compelled to give any information except for name, age, rank, and service number

In addition, if wounded or sick on the battlefield, the prisoner will receive help from the International Committee of the Red Cross.

When a country is responsible for breaches of prisoner of war rights, those accountable will be punished accordingly. An example of this is the

Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

and

Tokyo Trials

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

. German and Japanese military commanders were prosecuted for preparing and initiating a

war of aggression

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation.

Wars without international legality (i.e. not out of self-defense nor san ...

,

murder, ill treatment, and

deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

of individuals, and

genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Lat ...

during World War II. Most were executed or sentenced to life in prison for their crimes.

U.S. Code of Conduct and terminology

The United States Military Code of Conduct

The Code of the U.S. Fighting Force is a code of conduct that is an ethics guide and a United States Department of Defense directive consisting of six articles to members of the United States Armed Forces, addressing how they should act in combat ...

was promulgated in 1955 via

Executive Order 10631

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive dir ...

under

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

to serve as a moral code for United States service members who have been taken prisoner. It was created primarily in response to the breakdown of leadership and organization, specifically when U.S. forces were POWs during the

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

.

When a military member is taken prisoner, the Code of Conduct reminds them that the chain of command is still in effect (the highest ranking service member eligible for command, regardless of service branch, is in command), and requires them to support their leadership. The Code of Conduct also requires service members to resist giving information to the enemy (beyond identifying themselves, that is, "name, rank, serial number"), receiving special favours or parole, or otherwise providing their enemy captors aid and comfort.

Since the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

, the official U.S. military term for enemy POWs is EPW (Enemy Prisoner of War). This name change was introduced in order to distinguish between enemy and U.S. captives.

In 2000, the U.S. military replaced the designation "Prisoner of War" for captured American personnel with "Missing-Captured". A January 2008 directive states that the reasoning behind this is since "Prisoner of War" is the international legal recognized status for such people there is no need for any individual country to follow suit. This change remains relatively unknown even among experts in the field and "Prisoner of War" remains widely used in the Pentagon which has a "POW/Missing Personnel Office" and awards the

Prisoner of War Medal

The Prisoner of War Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was authorized by Congress and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on 8 November 1985. The United States Code citation for the POW Medal statute is .

The ...

.

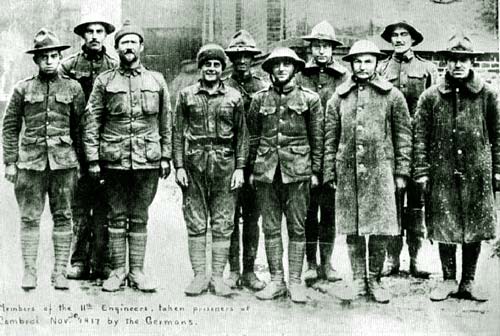

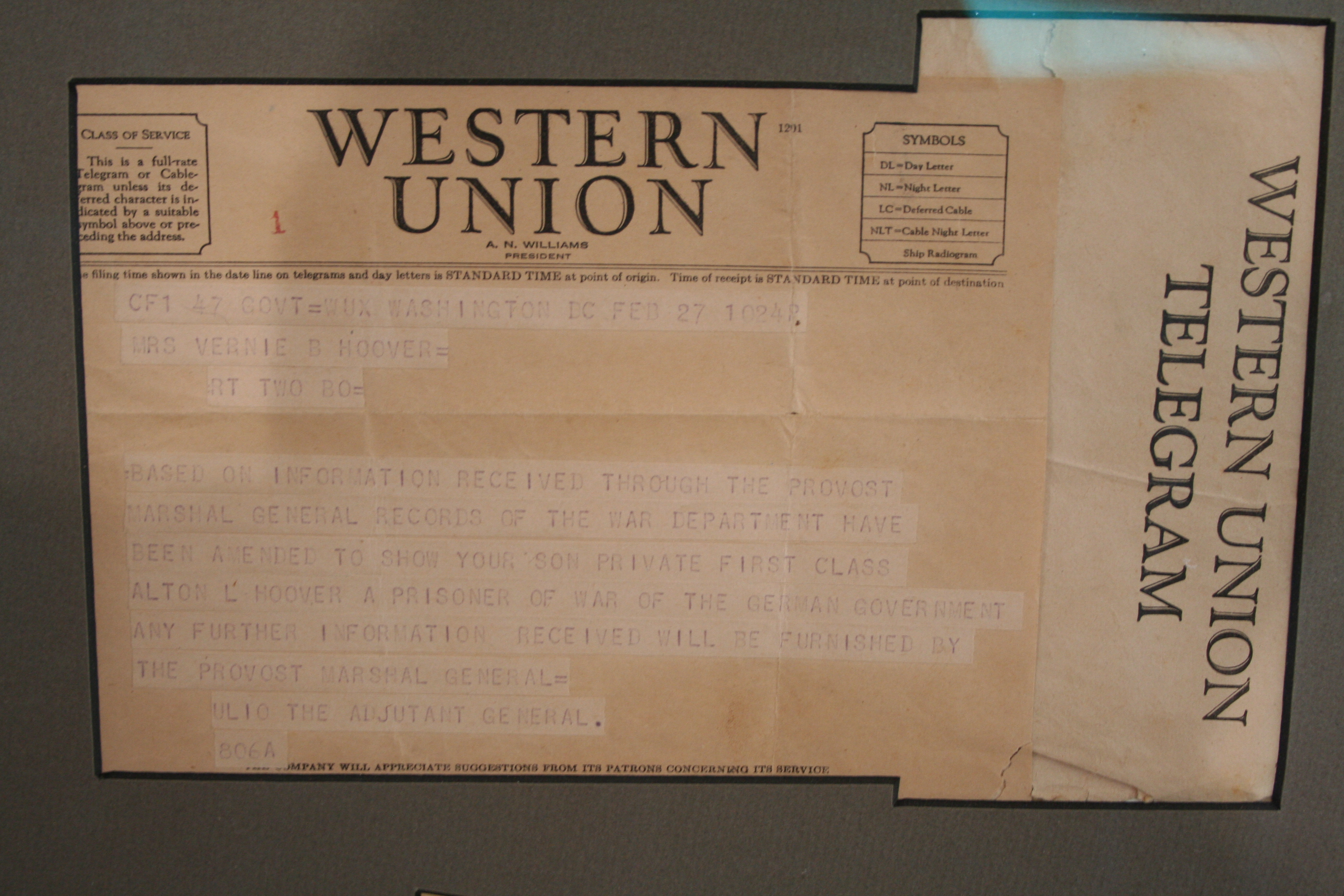

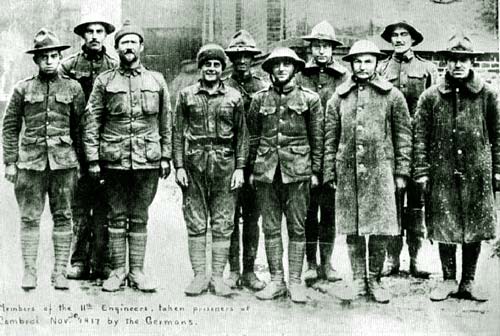

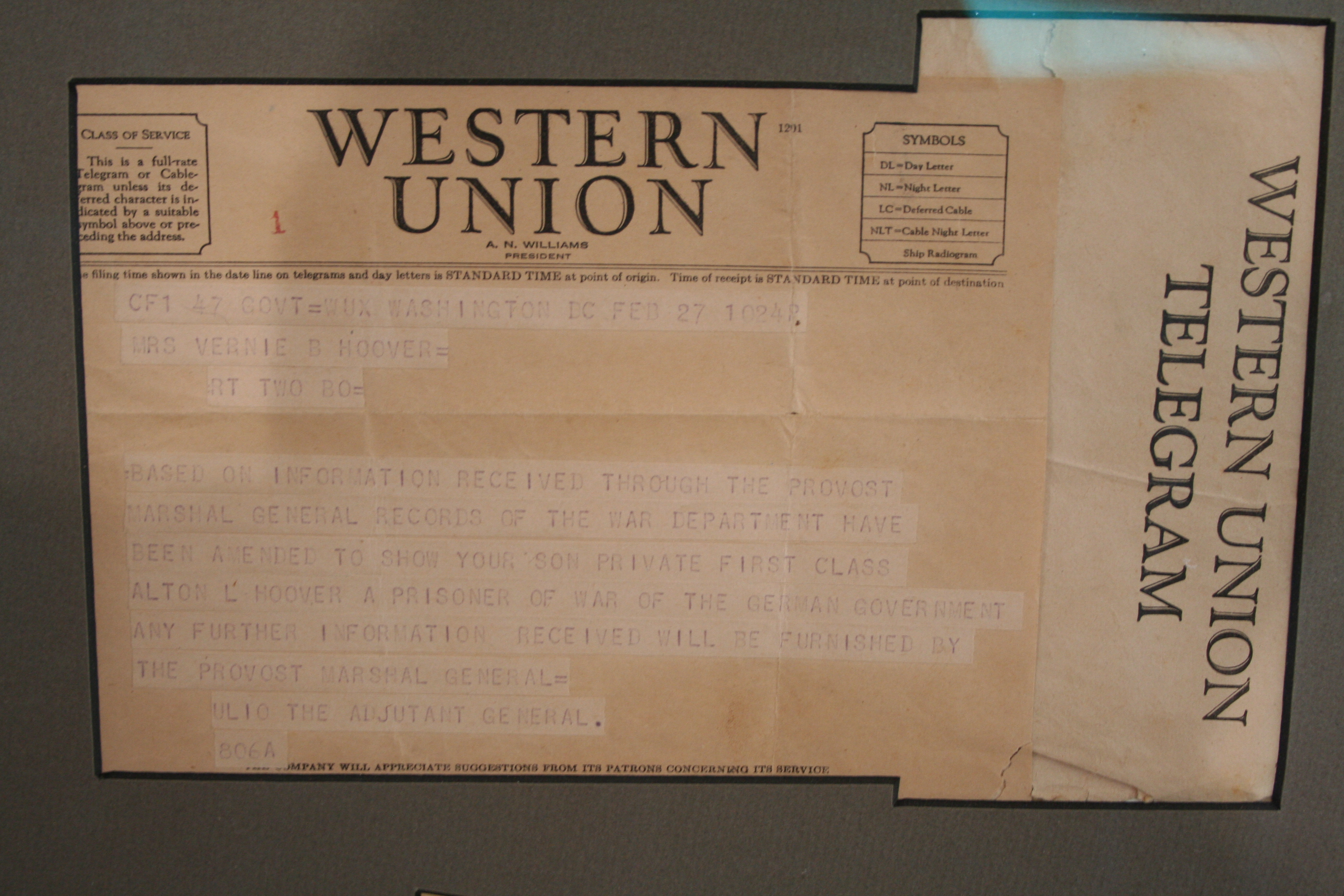

World War I

During World War I, about eight million men surrendered and were held in POW camps until the war ended. All nations pledged to follow the Hague rules on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and in general the POWs had a much higher survival rate than their peers who were not captured. Individual surrenders were uncommon; usually a large unit surrendered all its men. At

Tannenberg 92,000 Russians surrendered during the battle. When the besieged garrison of

Kaunas surrendered in 1915, 20,000 Russians became prisoners. Over half the Russian losses were prisoners as a proportion of those captured, wounded or killed. About 3.3 million men became prisoners.

The

German Empire held 2.5 million prisoners;

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

held 2.9 million, and

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

held about 720,000, mostly gained in the period just before the

Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

in 1918. The US held 48,000. The most dangerous moment for POWs was the act of surrender, when helpless soldiers were sometimes killed or mistakenly shot down. Once prisoners reached a POW camp conditions were better (and often much better than in World War II), thanks in part to the efforts of the

International Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

and inspections by neutral nations.

There was much harsh treatment of POWs in Germany, as recorded by the American ambassador (prior to America's entry into the war), James W. Gerard, who published his findings in "My Four Years in Germany". Even worse conditions are reported in the book "Escape of a Princess Pat" by the Canadian George Pearson. It was particularly bad in Russia, where starvation was common for prisoners and civilians alike; a quarter of the over 2 million POWs held there died. Nearly 375,000 of the 500,000

Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war taken by Russians perished in

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

from

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and

typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

. In Germany, food was short, but only 5 per cent died.

The

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

often treated prisoners of war poorly. Some 11,800 British soldiers, most from the

British Indian Army, became prisoners after the five-month

Siege of Kut

The siege of Kut Al Amara (7 December 1915 – 29 April 1916), also known as the first battle of Kut, was the besieging of an 8,000 strong British Army garrison in the town of Kut, south of Baghdad, by the Ottoman Army. In 1915, its population ...

, in

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, in April 1916. Many were weak and starved when they surrendered and 4,250 died in captivity.

During the

Sinai and Palestine campaign 217 Australian and unknown numbers of British, New Zealand and Indian soldiers were captured by Ottoman forces. About 50 per cent of the Australian prisoners were light horsemen including 48 missing believed captured on 1 May 1918 in the Jordan Valley.

Australian Flying Corps

The Australian Flying Corps (AFC) was the branch of the Australian Army responsible for operating aircraft during World War I, and the forerunner of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The AFC was established in 1912, though it was not until ...

pilots and observers were captured in the Sinai Peninsula, Palestine and the Levant. One third of all Australian prisoners were captured on Gallipoli including the crew of the submarine AE2 which made a passage through the Dardanelles in 1915. Forced marches and crowded railway journeys preceded years in camps where disease, poor diet and inadequate medical facilities prevailed. About 25 per cent of other ranks died, many from malnutrition, while only one officer died. The most curious case came in Russia where the

Czechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion (Czech language, Czech: ''Československé legie''; Slovak language, Slovak: ''Československé légie'') were volunteer armed forces composed predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Allies of World ...

of

Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

**Fourth Czechoslovak Repub ...

prisoners (from the

Austro-Hungarian army) who were released and armed to fight on the side of the Entente, who briefly served as a military and diplomatic force during the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

.

Release of prisoners

At the end of the war in 1918 there were believed to be 140,000 British prisoners of war in Germany, including thousands of internees held in neutral Switzerland. The first British prisoners were released and reached

Calais on 15 November. Plans were made for them to be sent via

Dunkirk to

Dover and a large reception camp was established at Dover capable of housing 40,000 men, which could later be used for

demobilisation

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and milit ...

.

On 13 December 1918, the armistice was extended and the Allies reported that by 9 December 264,000 prisoners had been repatriated. A very large number of these had been released ''en masse'' and sent across Allied lines without any food or shelter. This created difficulties for the receiving Allies and many ex-prisoners died from exhaustion. The released POWs were met by

cavalry troops and sent back through the lines in lorries to reception centres where they were refitted with boots and clothing and dispatched to the ports in trains.

Upon arrival at the receiving camp the POWs were registered and "boarded" before being dispatched to their own homes. All

commissioned officers had to write a report on the circumstances of their capture and to ensure that they had done all they could to avoid capture. Each returning officer and man was given a message from King

George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

, written in his own hand and reproduced on a lithograph.

While the Allied prisoners were sent home at the end of the war, the same treatment was not granted to

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

prisoners of the Allies and Russia, many of whom had to serve as

forced labour, e.g. in France, until 1920. They were released after many approaches by the

ICRC

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

to the

Allied Supreme Council

The Supreme War Council was a central command based in Versailles (city), Versailles that coordinated the military strategy of the principal Allies of World War I: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Britain, French Third Republic, Franc ...

.

World War II

Historian

, in addition to figures from

Keith Lowe, tabulated the total death rate for POWs in World War II as follows:

Treatment of POWs by the Axis

Empire of Japan

The

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

, which had signed but never ratified the

1929 Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War, did not treat prisoners of war in accordance with international agreements, including provisions of the

Hague Conventions, either during the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

or during the

Pacific War, because the Japanese viewed surrender as dishonorable. Moreover, according to a directive ratified on 5 August 1937 by

Hirohito, the constraints of the Hague Conventions were explicitly removed on Chinese prisoners.

Prisoners of war from China, the United States, Australia, Britain, Canada, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the Philippines held by Japanese imperial armed forces were subject to murder, beatings, summary punishment, brutal treatment,

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

,

medical experiments, starvation rations, poor medical treatment and

cannibalism. The most notorious use of forced labour was in the construction of the Burma–Thailand

Death Railway

The Burma Railway, also known as the Siam–Burma Railway, Thai–Burma Railway and similar names, or as the Death Railway, is a railway between Ban Pong, Thailand and Thanbyuzayat, Burma (now called Myanmar). It was built from 1940 to 1943 ...

. After 20 March 1943, the Imperial Navy was ordered to kill prisoners taken at sea. After the

Armistice of Cassibile, Italian soldiers and civilians in East Asia were taken as prisoners by Japanese armed forces and subject to the same conditions as other POWs.

According to the findings of the

Tokyo Tribunal

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conve ...

, the death rate of Western prisoners was 27.1 per cent, seven times that of POWs under the Germans and Italians.

The death rate of Chinese was much higher. Thus, while 37,583 prisoners from the United Kingdom, Commonwealth, and Dominions, 28,500 from the Netherlands, and 14,473 from the United States were released after the

surrender of Japan, the number for the Chinese was only 56.

[ The 27,465 ]United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

and United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

POWs in the Pacific Theater had a 40.4 per cent death rate. The War Ministry in Tokyo issued an order at the end of the war to kill the remaining POWs.

No direct access to the POWs was provided to the International Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

. Escapes among Caucasian prisoners were almost impossible because of the difficulty of hiding in Asiatic societies.

Allied POW camps and ship-transports were sometimes accidental targets of Allied attacks. The number of deaths which occurred when Japanese "hell ship

A hell ship is a ship with extremely inhumane living conditions or with a reputation for cruelty among the crew. It now generally refers to the ships used by the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army to transport Allied prisoners o ...

s"—unmarked transport ships in which POWs were transported in harsh conditions—were attacked by U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

submarines was particularly high. Gavan Daws has calculated that "of all POWs who died in the Pacific War, one in three was killed on the water by friendly fire". Daws states that 10,800 of the 50,000 POWs shipped by the Japanese were killed at sea while Donald L. Miller states that "approximately 21,000 Allied POWs died at sea, about 19,000 of them killed by friendly fire."

Life in the POW camps was recorded at great risk to themselves by artists such as Jack Bridger Chalker

Jack Bridger Chalker (10 October 1918 – 15 November 2014), was a British artist and teacher best known for his work recording the lives of the prisoners of war building the Burma Railway during World War II.

Biography

Chalker was born in Lo ...

, Philip Meninsky

Philip Meninsky (born 1919 in Fulham, England, died in 2007) was the son of Bernard Meninsky. Despite an early passion for art, at his father's wish, he initially trained as an accountant, before being called up for National Service.

After a firs ...

, Ashley George Old

Ashley George Old (born 1913, d. 2001) was an artist best known for documenting the lives of prisoners of war forced to construct the Thailand-Burma Railway.

During World War II he was stationed in Singapore, and when it fell to the Japanese in F ...

, and Ronald Searle

Ronald William Fordham Searle, CBE, RDI (3 March 1920 – 30 December 2011) was an English artist and satirical cartoonist, comics artist, sculptor, medal designer and illustrator. He is perhaps best remembered as the creator of St Trinian's S ...

. Human hair was often used for brushes, plant juices and blood for paint, toilet paper as the "canvas". Some of their works were used as evidence in the trials of Japanese war criminals.

Female prisoners (detainees) at Changi Prison

Changi Prison Complex, often known simply as Changi Prison, is a prison in Changi in the eastern part of Singapore.

History First prison

Before Changi Prison was constructed, the only penal facility in Singapore was at Pearl's Hill, beside ...

in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, recorded their ordeal in seemingly harmless prison quilt embroidery.

Research into the conditions of the camps has been conducted by The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

File:Bosbritsurrendergroup.jpg, Troops of the Suffolk Regiment surrendering to the Japanese, 1942

File:March of Death from Bataan to the prison camp - Dead soldiers.jpg, Many US and Filipino POWs died on the Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March (Filipino: ''Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan''; Spanish: ''Marcha de la muerte de Bataán'' ; Kapampangan: ''Martsa ning Kematayan quing Bataan''; Japanese: バターン死の行進, Hepburn: ''Batān Shi no Kōshin'') wa ...

, in May 1942

File:Portrait of "Dusty" Rhodes by Ashley George Old.jpg, Water colour sketch of "Dusty" Rhodes by Ashley George Old

Ashley George Old (born 1913, d. 2001) was an artist best known for documenting the lives of prisoners of war forced to construct the Thailand-Burma Railway.

During World War II he was stationed in Singapore, and when it fell to the Japanese in F ...

File:POWs Burma Thai RR.jpg, Australian and Dutch POWs at Tarsau, Thailand in 1943

File:Army nurses rescued from Santo Tomas 1945h.jpg, U.S. Army Nurses in Santo Tomas Internment Camp

Santo Tomas Internment Camp, also known as the Manila Internment Camp, was the largest of several camps in the Philippines in which the Japanese interned enemy civilians, mostly Americans, in World War II. The campus of the University of Santo ...

, 1943

File:Navy Nurses Rescued from Los Banos.jpg, U.S. Navy nurses rescued from Los Baños Internment Camp, March 1945

File:Gaunt allied prisoners of war at Aomori camp near Yokohama cheer rescuers from U.S. Navy. Waving flags of the United... - NARA - 520992.tif, Allied prisoners of war at Aomori camp

is the capital city of Aomori Prefecture, in the Tōhoku region of Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 278,964 in 136,457 households, and a population density of 340 people per square kilometer spread over the city's total are ...

near Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

, Japan waving flags of the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands in August 1945.

File:Canadian POWs at the Liberation of Hong Kong.gif, Canadian POWs at the Liberation of Hong Kong

File:Aso Mining POWs.jpg, Malnourished Australian POWs forced to work at the Aso mining company, August 1945.

File:Giving a sick man a drink as US POWs of Japanese, Philippine Islands, Cabanatuan prison camp.jpg, POW art depicting Cabanatuan prison camp, produced in 1946

File:LeonardGSiffleet.jpg, Australian POW Leonard Siffleet captured at New Guinea moments before his execution with a Japanese shin gunto sword in 1943.

File:Japanese atrocities imperial war museum K9923.jpg, Captured soldiers of the British Indian Army executed by the Japanese.

Germany

=French soldiers

=

After the French armies surrendered in summer 1940, Germany seized two million French prisoners of war and sent them to camps in Germany. About one third were released on various terms. Of the remainder, the officers and non-commissioned officers were kept in camps and did not work. The privates were sent out to work. About half of them worked for German agriculture, where food supplies were adequate and controls were lenient. The others worked in factories or mines, where conditions were much harsher.

=Western Allies' POWs

=

Germany and Italy generally treated prisoners from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and Commonwealth, France, the U.S., and other western Allies in accordance with the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conve ...

, which had been signed by these countries. Consequently, western Allied officers were not usually made to work and some personnel of lower rank were usually compensated, or not required to work either. The main complaints of western Allied prisoners of war in German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

POW camps—especially during the last two years of the war—concerned shortages of food.

Only a small proportion of western Allied POWs who were

Only a small proportion of western Allied POWs who were Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s—or whom the Nazis believed to be Jewish—were killed as part of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

or were subjected to other antisemitic policies. For example, Major Yitzhak Ben-Aharon

Yitzhak Ben-Aharon ( he, יצחק בן אהרון;17 July 1906 – 19 May 2006) was an Israeli left-wing politician.

He was a Knesset member from the first to the fifth Knessets and in the seventh and eighth, and a former Minister of Transpo ...

, a Palestinian Jew who had enlisted in the British Army, and who was captured by the Germans in Greece in 1941, experienced four years of captivity under entirely normal conditions for POWs.

A small number of Allied personnel were sent to concentration camps, for a variety of reasons including being Jewish. As the US historian Joseph Robert White put it: "An important exception ... is the sub-camp for U.S. POWs at Berga an der Elster, officially called ''Arbeitskommando

''Arbeitslager'' () is a German language word which means labor camp. Under Nazism, the German government (and its private-sector, Axis, and collaborator partners) used forced labor extensively, starting in the 1930s but most especially duri ...

625'' lso_known_as_''Stalag_IX-B''.html" ;"title="Stalag_IX-B.html" ;"title="lso known as ''Stalag IX-B">lso known as ''Stalag IX-B''">Stalag_IX-B.html" ;"title="lso known as ''Stalag IX-B">lso known as ''Stalag IX-B'' Berga was the deadliest work detachment for American captives in Germany. 73 men who participated, or 21 percent of the detachment, perished in two months. 80 of the 350 POWs were Jews." Another well-known example was a group of 168 Australian, British, Canadian, New Zealand and US aviators who were held for two months at Buchenwald concentration camp; two of the POWs died at Buchenwald. Two possible reasons have been suggested for this incident: German authorities wanted to make an example of '' Terrorflieger'' ("terrorist aviators") or these aircrews were classified as spies, because they had been disguised as civilians or enemy soldiers when they were apprehended.

Information on conditions in the stalags is contradictory depending on the source. Some American POWs claimed the Germans were victims of circumstance and did the best they could, while others accused their captors of brutalities and forced labour. In any case, the prison camps were miserable places where food rations were meager and conditions squalid. One American admitted "The only difference between the stalags and concentration camps was that we weren't gassed or shot in the former. I do not recall a single act of compassion or mercy on the part of the Germans." Typical meals consisted of a bread slice and watery potato soup which was still more substantial than what Soviet POWs or concentration camp inmates received. Another prisoner stated that "The German plan was to keep us alive, yet weakened enough that we wouldn't attempt escape."

As the Red Army approached some POW camps in early 1945, German guards forced western Allied POWs to walk long distances towards central Germany, often in extreme winter weather conditions. It is estimated that, out of 257,000 POWs, about 80,000 were subject to such marches and up to 3,500 of them died as a result.

Information on conditions in the stalags is contradictory depending on the source. Some American POWs claimed the Germans were victims of circumstance and did the best they could, while others accused their captors of brutalities and forced labour. In any case, the prison camps were miserable places where food rations were meager and conditions squalid. One American admitted "The only difference between the stalags and concentration camps was that we weren't gassed or shot in the former. I do not recall a single act of compassion or mercy on the part of the Germans." Typical meals consisted of a bread slice and watery potato soup which was still more substantial than what Soviet POWs or concentration camp inmates received. Another prisoner stated that "The German plan was to keep us alive, yet weakened enough that we wouldn't attempt escape."

As the Red Army approached some POW camps in early 1945, German guards forced western Allied POWs to walk long distances towards central Germany, often in extreme winter weather conditions. It is estimated that, out of 257,000 POWs, about 80,000 were subject to such marches and up to 3,500 of them died as a result.

=Italian POWs

=

In September 1943 after the Armistice, Italian officers and soldiers many places waiting for orders were arrested by Germans and Italian fascists and taken to internment camps in Germany or Eastern Europe, where they were held for the duration of the war. The International Red Cross could do nothing for them, as they were not regarded as POWs, but the prisoners held the status of " military internees". Treatment of the prisoners was generally poor. The author Giovannino Guareschi

Giovannino Oliviero Giuseppe Guareschi (; 1 May 1908 – 22 July 1968) was an Italian journalist, cartoonist and humorist whose best known creation is the priest Don Camillo.

Life and career

Giovannino Guareschi was born into a middle-class famil ...

was among those interned and wrote about this time in his life. The book was translated and published as ''My Secret Diary''. He wrote about semi-starvation, the casual murder of individual prisoners by guards and how, when they were released (now from a German camp), they found a deserted German town filled with foodstuffs that they (with other released prisoners) ate.. It is estimated that of the 700,000 Italians taken prisoner by the Germans, around 40,000 died in detention and more than 13,000 lost their lives during the transportation from the Greek islands to the mainland.

=Eastern European POWs

=

Germany did not apply the same standard of treatment to non-western prisoners, especially many Polish and Soviet POWs who suffered harsh conditions and died in large numbers while in captivity.

Between 1941 and 1945 the Axis powers took about 5.7 million Soviet prisoners. About one million of them were released during the war, in that their status changed but they remained under German authority. A little over 500,000 either escaped or were liberated by the Red Army. Some 930,000 more were found alive in camps after the war. The remaining 3.3 million prisoners (57.5% of the total captured) died during their captivity. Between the launching of

Germany did not apply the same standard of treatment to non-western prisoners, especially many Polish and Soviet POWs who suffered harsh conditions and died in large numbers while in captivity.

Between 1941 and 1945 the Axis powers took about 5.7 million Soviet prisoners. About one million of them were released during the war, in that their status changed but they remained under German authority. A little over 500,000 either escaped or were liberated by the Red Army. Some 930,000 more were found alive in camps after the war. The remaining 3.3 million prisoners (57.5% of the total captured) died during their captivity. Between the launching of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

in the summer of 1941 and the following spring, 2.8 million of the 3.2 million Soviet prisoners taken died while in German hands. According to Russian military historian General Grigoriy Krivosheyev

Grigoriy Fedotovich Krivosheyev (russian: Григорий Федотович Кривошеев, 15 September 1929 – 29 April 2019) was a Russian military historian and a Colonel General of the Russian military. He is mostly known in the West, ...

, the Axis powers took 4.6 million Soviet prisoners, of whom 1.8 million were found alive in camps after the war and 318,770 were released by the Axis during the war and were then drafted into the Soviet armed forces again. The Germans officially justified their policy on the grounds that the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention. Legally, however, under article 82 of the

The Germans officially justified their policy on the grounds that the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention. Legally, however, under article 82 of the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conve ...

, signatory countries had to give POWs of all signatory and non-signatory countries the rights assigned by the convention.International Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; french: Comité international de la Croix-Rouge) is a humanitarian organization which is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and it is also a three-time Nobel Prize Laureate. State parties (signato ...

– made several efforts to regulate reciprocal treatment of prisoners until early 1942, but received no answers from the Soviet side. Further, the Soviets took a harsh position towards captured Soviet soldiers, as they expected each soldier to fight to the death, and automatically excluded any prisoner from the "Russian community".

Some Soviet POWs and forced labourers whom the Germans had transported to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

were, on their return to the USSR, treated as traitors and sent to gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

prison-camps.

Treatment of POWs by the Soviet Union

Germans, Romanians, Italians, Hungarians, Finns

According to some sources, the Soviets captured 3.5 million

According to some sources, the Soviets captured 3.5 million Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics