War of the Bar Confederation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

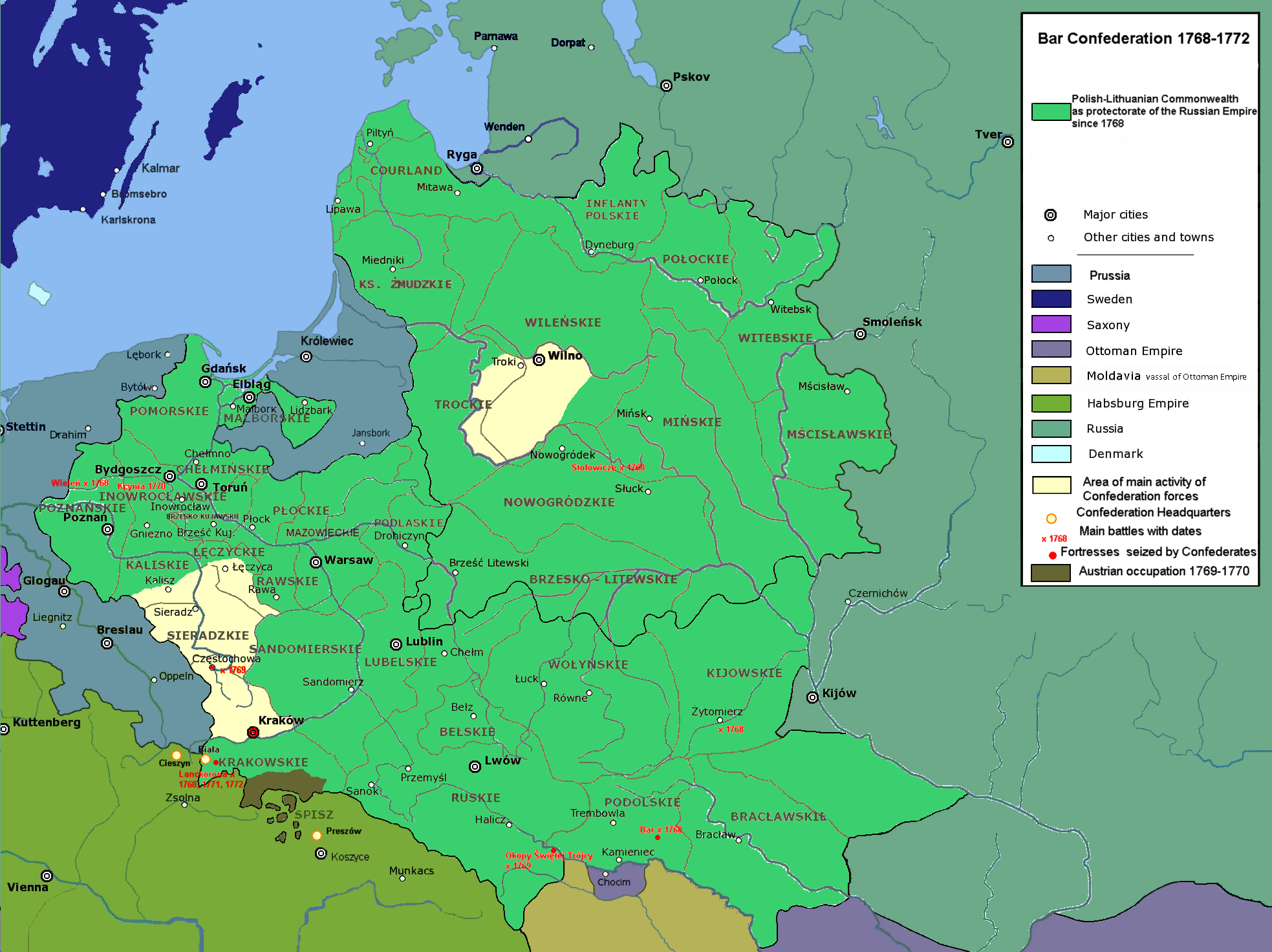

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of

Wikisource

/ref>'') which the Repnin Sejm accepted without debate on 27 February 1768.

An attempt of Bar Confederates (including

An attempt of Bar Confederates (including

Although for a few decades (since the times of the

Although for a few decades (since the times of the

''Radom i Bar 1767-1768: dziennik wojennych działań jenerał-majora Piotra Kreczetnikowa w Polsce w r. 1767 i 1768 korpusem dowodzącego i jego wojenno-polityczną korespondencyą z księciem Mikołajem Repninem'' Poznań 1874

{{Authority control Polish confederations Polish–Russian wars Uprisings of Poland History of Galicia (Eastern Europe) 1760s in Poland 1770s in Poland Wars involving Russia Wars involving Poland Conflicts in 1768 Conflicts in 1769 Conflicts in 1770 Conflicts in 1771 Conflicts in 1772 1768 establishments in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Warfare of the Early Modern period Articles containing video clips Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth–Russian Empire relations

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

nobles (szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in the ...

) formed at the fortress of Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

in Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

(now part of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

against Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

influence and against King Stanislaus II Augustus with Polish reformers, who were attempting to limit the power of the Commonwealth's wealthy magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s. The founders of the Bar Confederation included the magnates Adam Stanisław Krasiński

Adam Stanisław Krasiński (1714–1800) was a Polish noble of Ślepowron coat of arms, bishop of Kamieniec (1757–1798), Great Crown Secretary (from 1752), president of the Crown Tribunal in 1759 and one of the leaders of Bar Confederation (17 ...

, Bishop of Kamieniec, Karol Stanisław Radziwiłł, Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski of the Ślepowron coat of arms (; ''Casimir Pulaski'' ; March 4 or March 6, 1745 Makarewicz, 1998 October 11, 1779) was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called, tog ...

, his father and brothers and Michał Krasiński Michał () is a Polish and Sorbian form of Michael and may refer to:

* Michał Bajor (born 1957), Polish actor and musician

* Michał Chylinski (born 1986), Polish basketball player

* Michał Drzymała (1857–1937), Polish rebel

* Michał Heller ( ...

. Its creation led to a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and contributed to the First Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Maurice Benyovszky

Count Maurice Benyovszky de Benyó et Urbanó ( hu, Benyovszky Máté Móric Mihály Ferenc Szerafin Ágost; pl, Maurycy Beniowski; sk, Móric Beňovský; 20 September 1746 – 24 May 1786) was a renowned military officer, adventurer, and writ ...

was the best known European Bar Confederation volunteer, supported by Roman Catholic France and Austria. Some historians consider the Bar Confederation the first Polish uprising

This is a chronological list of military conflicts in which Polish armed forces fought or took place on Polish territory from the reign of Mieszko I (960–992) to the ongoing military operations.

This list does not include peacekeeping operation ...

.

Background

Abroad

At the end of theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

(1756-1763), Russia, first allied with Austria and France, had decided to support Prussia, allowing a victory of the Prussians (allied with Great-Britain) over the Austrians (allied with France).

On 11 April 1764, a new treaty was signed between Frederick of Prussia and Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

, choosing Stanislaus Poniatowski Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cali ...

(ex-lover of Catherine II) as the future king of Poland after Augustus III

Augustus III ( pl, August III Sas, lt, Augustas III; 17 October 1696 5 October 1763) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1733 until 1763, as well as Elector of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire where he was known as Frederick Augu ...

's death (October 1763).

Neither France nor Austria were able to challenge this candidate and Stanislas was elected in October 1764.

In the Commonwealth

In the early 18th century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had declined from the status of a major European power to that of a Russiansatellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting ...

, with the Russian tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

effectively choosing Polish–Lithuanian monarchs during the "free" elections and deciding the direction of much of Poland's internal politics, for example during the Repnin Sejm

The Repnin Sejm ( pl, Sejm Repninowski) was a Sejm (session of the parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place between 1767 and 1768 in Warsaw. This session followed the Sejms of 1764 to 1766, where the newly elected King ...

(1767-1768), named after the Russian ambassador who unofficially presided over the proceedings.

During this session, the Polish parliament

The parliament of Poland is the bicameral legislature of Poland. It is composed of an upper house (the Senate) and a lower house (the Sejm). Both houses are accommodated in the ''Sejm'' complex in Warsaw. The Constitution of Poland does not ref ...

(Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

) was forced to pass resolutions demanded by the Russians. Many of the conservative nobility felt anger at that foreign interference, at the perceived weakness of the government under king Stanislaus Augustus Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cali ...

, and at the provisions, particularly the ones that empowered non-Catholics, and at other reforms which they saw as threatening the Golden Freedoms

Golden Liberty ( la, Aurea Libertas; pl, Złota Wolność, lt, Auksinė laisvė), sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth ( pl, Rzeczpospolita Szlachecka or ''Złota wolność szlachecka'') was a pol ...

of the Polish nobility.

The protectorate of Russia over Poland became official with the "Treaty of perpetual friendship between Russia and the Commonwealth" (''Traktat wieczystej przyjaźni pomiędzy Rosją a RzecząpospolitąCfWikisource

/ref>'') which the Repnin Sejm accepted without debate on 27 February 1768.

Creation of the Bar Confederation (29 February 1768)

In response to that, and particularly after Russian troops arrested and exiled several vocal opponents (namely bishop of KyivJózef Andrzej Załuski

Józef Andrzej Załuski (12 January 17029 January 1774) was a Polish Catholic priest, Bishop of Kiev, a sponsor of learning and culture, and a renowned bibliophile. A member of the Polish nobility (''szlachta''), bearing the hereditary Junosza ...

, bishop of Cracow

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

Kajetan Sołtyk

Kajetan Ignacy Sołtyk (12 November 1715 – 30 July 1788) was a Polish Catholic priest, bishop of Kiev from 1756, bishop of Kraków from 13 March 1759.

Biography

Son of Józef Sołtyk, castellan of Lublin and court marshal to primate of Pola ...

, and Field Crown Hetman

Field may refer to:

Expanses of open ground

* Field (agriculture), an area of land used for agricultural purposes

* Airfield, an aerodrome that lacks the infrastructure of an airport

* Battlefield

* Lawn, an area of mowed grass

* Meadow, a grass ...

Wacław Rzewuski

Wacław Piotr Rzewuski (1706–1779) was a Polish dramatist and poet as well as a military commander and a Grand Crown Hetman. As a notable nobleman and magnate, Rzewuski held a number of important posts in the administration of the Polish–Li ...

with his son Seweryn Seweryn may refer to:

* Seweryn Berson (1858–1917), Polish lawyer and composer

* Seweryn Bialer (born 1926), emeritus professor of political science at Columbia University, expert on the Communist parties of the Soviet Union and Poland

* Seweryn ...

), a group of Polish magnates decided to form a '' confederatio'' - a military association opposing the government in accordance with Polish constitutional traditions. The articles of the confederation were signed on 29 February 1768 at the fortress of Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

in Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

.

The instigators of the confederation included Adam Krasiński

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

, Bishop of Kamieniec, his brother Michał Hieronim Krasiński

Michał Hieronim Krasiński (1712 – May 25, 1784) was a Polish noble, cześnik of Stężyca, podkomorzy of Różan, starost of Opiniogóra, deputy to many Sejms, one of the leaders of Bar Confederation (1768–1772).

He was a captain in Augus ...

, Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski of the Ślepowron coat of arms (; ''Casimir Pulaski'' ; March 4 or March 6, 1745 Makarewicz, 1998 October 11, 1779) was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called, tog ...

, Kajetan Sołtyk

Kajetan Ignacy Sołtyk (12 November 1715 – 30 July 1788) was a Polish Catholic priest, bishop of Kiev from 1756, bishop of Kraków from 13 March 1759.

Biography

Son of Józef Sołtyk, castellan of Lublin and court marshal to primate of Pola ...

, Wacław Rzewuski

Wacław Piotr Rzewuski (1706–1779) was a Polish dramatist and poet as well as a military commander and a Grand Crown Hetman. As a notable nobleman and magnate, Rzewuski held a number of important posts in the administration of the Polish–Li ...

, Michał Jan Pac

Michał Jan Pac (1730–1787) was a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, Lithuanian Marshal of the Bar Confederation from 1769 until 1772, Chamberlain of King Augustus.

He lived in exile in France after the defeat of the Confederation.

In 1780, he bought ...

, Jerzy August Mniszech, Joachim Potocki and Teodor Wessel. Priest Marek Jandołowicz was a notable religious leader, and Michał Wielhorski the Confederation's political ideologue.

Civil war and foreign interventions

1768

The confederation, encouraged and aided by Roman Catholic France and Austria, declared a war on Russia. Its irregular forces, formed from volunteers, magnate militias and deserters from the royal army, soon clashed with the Russian troops and units loyal to the Polish crown. Confederation forces underMichał Jan Pac

Michał Jan Pac (1730–1787) was a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, Lithuanian Marshal of the Bar Confederation from 1769 until 1772, Chamberlain of King Augustus.

He lived in exile in France after the defeat of the Confederation.

In 1780, he bought ...

and Prince Karol Stanisław Radziwiłł roamed the land in every direction, won several engagements with the Russians, and at last, utterly ignoring the King, sent envoys on their own account to the principal European powers, i.e. Ottoman Empire, the major ally of Bar confederation, France and Austria.

King Stanislaus Augustus was at first inclined to mediate between the Confederates and Russia, the latter represented by the Russian envoy to Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, Prince Nikolai Repnin

Prince Nikolai Vasilyevich Repnin (russian: Никола́й Васи́льевич Репни́н; – ) was an Imperial Russian statesman and general from the Repnin princely family who played a key role in the dissolution of the Polish–Lith ...

; but finding this impossible, he sent a force against them under Grand Hetman

( uk, гетьман, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military ...

Franciszek Ksawery Branicki

Franciszek Ksawery Branicki (1730–1819) was a Polish nobleman, magnate, French count, diplomat, politician, military commander, and one of the leaders of the Targowica Confederation. Many consider him to have been a traitor who participated wit ...

and two generals against the confederates. This marked the Ukrainian campaign, which lasted from April till June 1768, and was ended with the capture of Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

on 20 June. Confederation forces retreated to Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

. There was also a pro-Confederation force in Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a s ...

, that operated from June till August, that ended with the royal forces securing Kraków on 22 August, followed by a period of conflict in Belarus (August–October), that ended with the surrender of Nesvizh

Nesvizh, Niasviž ( be, Нясві́ж ; lt, Nesvyžius; pl, Nieśwież; russian: Не́свиж; yi, ניעסוויז; la, Nesvisium) is a city in Belarus. It is the administrative centre of the Nyasvizh District (''rajon'') of Minsk Region a ...

on 26 October.

However, the simultaneous outbreak of the Koliyivschyna

The Koliivshchyna ( uk, Коліївщина, pl, koliszczyzna) was a major haidamaky rebellion that broke out in Right-bank Ukraine in June 1768, caused by money (Dutch ducats coined in Saint Petersburg) sent by Russia to Ukraine to pay for th ...

in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

(May 1768 – June 1769) made major confederation forces retreat to Ottoman Empire beforehand and kept the Confederation alive.

The Confederates appealed for help from abroad and contributed to bringing about war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 was a major armed conflict that saw Russian arms largely victorious against the Ottoman Empire. Russia's victory brought parts of Moldavia, the Yedisan between the rivers Bug and Dnieper, and Crimea into the ...

that began in September).

1769–1770

The retreat of some Russian forces needed on the Ottoman front bolstered the confederates, who reappeared in force in Lesser Poland and Great Poland by 1769. In 1770 the Council of Bar Confederation transferred from its original seat in Austrian part ofSilesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, whence it conducted diplomatic negotiations with France, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

with a view to forming a stable league against Russia. The council proclaimed the king dethroned on 22 October 1770. The court of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

sent Charles François Dumouriez

Charles-François du Périer Dumouriez (, 26 January 1739 – 14 March 1823) was a French general during the French Revolutionary Wars. He shared the victory at Valmy with General François Christophe Kellermann, but later deserted the Revo ...

to act as an aid to the Confederates, and he helped them to organize their forces. The Confederates also began to operate in Lithuania, although after early successes that direction too met with failures, with defeats at Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok Up ...

on 16 July and Orzechowo on 13 September 1769. Early 1770 saw the defeats of confederates in Greater Poland, after the battle of Dobra (20 January) and Błonie (12 February), which forced them into a mostly defensive, passive stance.

Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski of the Ślepowron coat of arms (; ''Casimir Pulaski'' ; March 4 or March 6, 1745 Makarewicz, 1998 October 11, 1779) was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called, tog ...

) to kidnap king Stanislaus II Augustus on 3 November 1771 led the Habsburgs to withdraw their support from the confederates, expelling them from their territories. It also gave the three courts another pretext to showcase the " Polish anarchy" and the need for its neighbors to step in and "save" the country and its citizens. The king thereupon reverted to the Russian faction, and for the attempt of kidnapping their king, the Confederation lost much of the support it had in Europe.

1771–1772

Nevertheless, its army, thoroughly reorganized by Dumouriez, maintained the fight. 1771 brought further defeats, with the defeat atLanckorona

Lanckorona is a village located south-west of Kraków in Lesser Poland. It lies on the Skawinka river, among the hills of the Beskids, above sea level. It is known for the Lanckorona Castle, today in ruins. Lanckorona is also known for the Bat ...

on 21 May and Stałowicze at 23 October. The final battle of this war was the siege of Jasna Góra Jasna may refer to:

Places

* Jasna, a village in Poland

* Jasná, a village and ski resort in Slovakia

Other uses

* Jasna (given name), a Slavic female given name

* JASNA, the Jane Austen Society of North America

See also

* Yasna

Yasna (;

, which fell on 13 August 1772. The regiments of the Bar Confederation, whose executive board had been forced to leave Austria (which previously supported them) after that country joined the Prusso-Russian alliance, did not lay down their arms. Many fortresses in their command held out as long as possible; Wawel Castle

The Wawel Royal Castle (; ''Zamek Królewski na Wawelu'') and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established on ...

in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

fell only on 28 April; Tyniec

Tyniec is a historic village in Poland on the Vistula river, since 1973 a part of the city of Kraków (currently in the district of Dębniki). Tyniec is notable for its Benedictine abbey founded by King Casimir the Restorer in 1044.

Etymology

...

fortress held until 13 July 1772; Częstochowa

Częstochowa ( , ; german: Tschenstochau, Czenstochau; la, Czanstochova) is a city in southern Poland on the Warta River with 214,342 inhabitants, making it the thirteenth-largest city in Poland. It is situated in the Silesian Voivodeship (admin ...

, commanded by Casimir Pulaski

Kazimierz Michał Władysław Wiktor Pułaski of the Ślepowron coat of arms (; ''Casimir Pulaski'' ; March 4 or March 6, 1745 Makarewicz, 1998 October 11, 1779) was a Polish nobleman, soldier, and military commander who has been called, tog ...

, held until 18 August. Overall, around 100,000 nobles fought 500 engagements between 1768 and 1772. Perhaps the last stronghold of the confederates was in the monastery in Zagórz

Zagórz ( uk, Загі́р'я; german: Sagor) is a town in Sanok County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, Poland, on the river Osława in the Bukowsko Upland mountains, located south-east of Sanok on the way to Ustrzyki Dolne, distance. The neare ...

, which fell only on 28 November 1772. In the end, the Bar Confederation was defeated, with its members either fleeing abroad or being deported to Siberia, Volga region, Urals by the Russians.

In the meantime, taking advantage of the confusion in Poland, already by 1769–71, both Austria and Prussia had taken over some border territories of the Commonwealth, with Austria taking Szepes County

Szepes ( sk, Spiš; la, Scepusium, pl, Spisz, german: link=no, Zips) was an administrative county of the Kingdom of Hungary, called Scepusium before the late 19th century. Its territory today lies in northeastern Slovakia, with a very small are ...

in 1769-1770 and Prussia incorporating Lauenburg and Bütow

Lauenburg (), or Lauenburg an der Elbe ( en, Lauenberg on the Elbe), is a town in the state of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is situated on the northern bank of the river Elbe, east of Hamburg. It is the southernmost town of Schleswig-Holstein ...

. On 19 February 1772, the agreement of partition was signed in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. A previous secret agreement between Prussia and Russia had been made in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

on 6 February 1772. Early in August, Russian, Prussian, and Austrian troops fighting the Bar confederation in the Commonwealth occupied the provinces agreed upon among themselves. On 5 August, the three parties issued a manifesto about their respective territorial gains on the Commonwealth's expense.

Bar Confederates taken as prisoners by the Russians, together with their families, formed the first major group of Poles exiled to Siberia. It is estimated that about 5,000 former confederates were sent there. Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

organized 3 concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

s in Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

for Polish captives, where these concentrated persons have been waiting for their deportation there.

International situation after the defeat of Bar confederation and its Ottoman allies

Around the middle of the 18th century the balance of power in Europe shifted, with Russian victories against theOttomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 was a major armed conflict that saw Russian arms largely victorious against the Ottoman Empire. Russia's victory brought parts of Moldavia, the Yedisan between the rivers Bug and Dnieper, and Crimea into the ...

strengthening Russia and endangering Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

interests in that region (particularly in Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and so ...

). At that point Habsburg Austria started to consider waging a war against Russia. France, friendly towards both Prussia and Austria, suggested a series of territorial adjustments, in which Austria would be compensated by parts of Prussian Silesia

The Province of Silesia (german: Provinz Schlesien; pl, Prowincja Śląska; szl, Prowincyjŏ Ślōnskŏ) was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1919. The Silesia region was part of the Prussian realm since 1740 and established as an official p ...

, and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

in turn would receive Polish Ermland (Warmia) and parts of the Polish fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an Lord, overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a for ...

, Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia ( la, Ducatus Curlandiæ et Semigalliæ; german: Herzogtum Kurland und Semgallen; lv, Kurzemes un Zemgales hercogiste; lt, Kuršo ir Žiemgalos kunigaikštystė; pl, Księstwo Kurlandii i Semigalii) was ...

—already under Baltic German

Baltic Germans (german: Deutsch-Balten or , later ) were ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their coerced resettlement in 1939, Baltic Germans have markedly declined ...

hegemony. King Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

had no intention of giving up Silesia gained recently in the Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars (german: Schlesische Kriege, links=no) were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg Austria (under Archduchess Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

; he was, however, also interested in finding a peaceful solution — his alliance with Russia would draw him into a potential war with Austria, and the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

had left Prussia's treasury and army weakened. He was also interested in protecting the weakening Ottoman Empire, which could be advantageously utilized in the event of a Prussian war either with Russia or Austria. Frederick's brother, Prince Henry Prince Henry (or Prince Harry) may refer to:

People

*Henry the Young King (1155–1183), son of Henry II of England, who was crowned king but predeceased his father

*Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (1394–1460)

*Henry, Duke of Cornwall (Ja ...

, spent the winter of 1770–71 as a representative of the Prussian court at Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. As Austria had annexed 13 towns in the Hungarian Szepes region in 1769 (violating the Treaty of Lubowla

Treaty of Lubowla of 1412 was a treaty between Jogaila, Władysław II, King of Poland, and Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund of Luxemburg, King of Kingdom of Hungary, Hungary. They Negotiated in the town of Lublo (today Stará Ľubovňa, ...

), Catherine II of Russia

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

and her advisor General Ivan Chernyshyov

Count Ivan Grigoryevich Chernyshyov (1726 – 1797; russian: Граф Иван Григорьевич Чернышёв) was an Imperial Russian Field Marshal and General Admiral, prominent during the reign of Empress Catherine the Great.

Life and ...

suggested to Henry that Prussia claim some Polish land, such as Ermland. After Henry informed him of the proposal, Frederick suggested a partition of the Polish borderlands by Austria, Prussia, and Russia, with the largest share going to Austria. Thus Frederick attempted to encourage Russia to direct its expansion towards weak and non-functional Poland instead of the Ottomans.

Silent Sejm

Silent Sejm ( pl, Sejm Niemy; lt, Nebylusis seimas), also known as the Mute Sejm, is the name given to the session of the Sejm parliament of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of 1 February 1717 held in Warsaw. A civil war in the Commonwealth wa ...

) Russia had seen weak Poland as its own protectorate, Poland had also been devastated by a civil war in which the forces of the Bar Confederation attempted to disrupt Russian control over Poland. The recent Koliyivschyna

The Koliivshchyna ( uk, Коліївщина, pl, koliszczyzna) was a major haidamaky rebellion that broke out in Right-bank Ukraine in June 1768, caused by money (Dutch ducats coined in Saint Petersburg) sent by Russia to Ukraine to pay for th ...

peasant and Cossack uprising in Ukraine also weakened Polish position. Further, the Russian-supported Polish king, Stanislaus Augustus Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cali ...

, was seen as both weak and too independent-minded; eventually the Russian court decided that the usefulness of Poland as a protectorate had diminished. The three powers officially justified their actions as a compensation for dealing with troublesome neighbor and restoring order to Polish anarchy (the Bar Confederation provided a convenient excuse); in fact all three were interested in territorial gains.

After Russia occupied the Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th ce ...

, Henry convinced Frederick and Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' ( ...

that the balance of power would be maintained by a tripartite division of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth instead of Russia taking land from the Ottomans. Under pressure from Prussia, which for a long time wanted to annex the northern Polish province of Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia ( pl, Prusy Królewskie; german: Königlich-Preußen or , csb, Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) was a ...

, the three powers agreed on the First Partition of Poland. This was in light of the possible Austrian-Ottoman-Bar confederation alliance with only token objections from Austria, which would have instead preferred to receive more Ottoman territories in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, a region which for a long time had been coveted by the Habsburgs, including Bukovina. The Russians also withdrew from Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

and Wallachia away from the Austrian border.

Legacy

Until the times of the Bar Confederation, confederates – especially operating with the aid of outside forces – were seen as unpatriotic antagonists. But in 1770s, during the times that theRussian Army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �В Sukhoputnyye voyska V, also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Gro ...

marched through the theoretically independent Commonwealth, and foreign powers forced the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

to agree to the First Partition of Poland, the confederates started to create an image of Polish exiled soldiers, the last of those who remained true to their Motherland, an image that would in the next two centuries lead to the creation of Polish Legions and other forces in exile.

The Confederation has generated varying assessments from the historians. All admit its patriotic desire to free the Commonwealth from outside (primarily-Russian) influence. Some, such as Jacek Jędruch

Jacek Jędruch (Warsaw, Poland, 1927 – Athens, Greece, 1995) was a Polish-American nuclear engineer and historian of Polish representative government.

Life

During World War II, Jędruch participated in the Polish Resistance movement. After ...

, criticise its regressive stance on civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

issues, primarily with regards to religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

(Jędruch writes of "religious bigotry" and a "narrowly Catholic" stance), and assert that to have contributed to the First Partition. Others, such as Bohdan Urbankowski

Bohdan Urbankowski (19 May 1943 – 15 June 2023) was a Polish writer, poet, and philosopher.

An opposition activist in the People's Republic of Poland, he received several awards for his publications, most of which were published underground ( ...

, applaud it as the first serious national military effort to restore Polish independence.

The Bar Confederation has been described as the first Polish uprising

This is a chronological list of military conflicts in which Polish armed forces fought or took place on Polish territory from the reign of Mieszko I (960–992) to the ongoing military operations.

This list does not include peacekeeping operation ...

and the last mass movement of szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in the ...

. It is also commemorated on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Warsaw

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier ( pl, Grób Nieznanego Żołnierza) is a monument in Warsaw, Poland, dedicated to the unknown soldiers who have given their lives for Poland. It is one of many such national tombs of unknowns that were erected af ...

, with the inscription "".

See also

*Aleksandr Bibikov

Aleksandr Ilyich Bibikov (russian: Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Би́биков) (, Moscow – , Bugulma) was a Russian statesman and military officer.

Bibikov came from an old noble family; Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov was his brother-i ...

* Anna Jabłonowska

Princess Anna Paulina Jabłonowska (22 June 1728, Wołpa - 7 February 1800, Ostroróg coat of arms), was a Polish magnate and politician. She was known for her remarkable activity on her estates, in which she introduced social inventions as wel ...

* Józef Sawa-Caliński

Józef Sawa-Caliński (about 1736 – May 1771) was a Polish noble and a prominent leader of the Confederation of Bar, a movement aimed against the Polish king and his close relations with Russia.

Born in Stepashky on Southern Bug to colo ...

* Koliyivshchyna

The Koliivshchyna ( uk, Коліївщина, pl, koliszczyzna) was a major haidamaky rebellion that broke out in Right-bank Ukraine in June 1768, caused by money (Dutch ducats coined in Saint Petersburg) sent by Russia to Ukraine to pay for t ...

References

Further reading

* * Aleksander Kraushar, ''Książę Repnin i Polska w pierwszem czteroleciu panowania Stanisława Augusta (1764-1768)'', (Prince Repin and Poland in the first four years of rule of Stanislaw August (1764–1768)) ** 2nd edition, corrected and expanded. vols. 1–2, Kraków 1898, G. Gebethner i Sp. ** Revised edition, Warszawa: Gebethner i Wolff; Kraków: G. Gebethner i Spółka, 1900. * F. A. Thesby de Belcour, ''The Confederates of Bar'' (in Polish) (Cracow, 1895) * Charles Francois Dumouriez, ' (Paris, 1834).''Radom i Bar 1767-1768: dziennik wojennych działań jenerał-majora Piotra Kreczetnikowa w Polsce w r. 1767 i 1768 korpusem dowodzącego i jego wojenno-polityczną korespondencyą z księciem Mikołajem Repninem'' Poznań 1874

External links

{{Authority control Polish confederations Polish–Russian wars Uprisings of Poland History of Galicia (Eastern Europe) 1760s in Poland 1770s in Poland Wars involving Russia Wars involving Poland Conflicts in 1768 Conflicts in 1769 Conflicts in 1770 Conflicts in 1771 Conflicts in 1772 1768 establishments in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Warfare of the Early Modern period Articles containing video clips Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth–Russian Empire relations