Walter Rathenau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

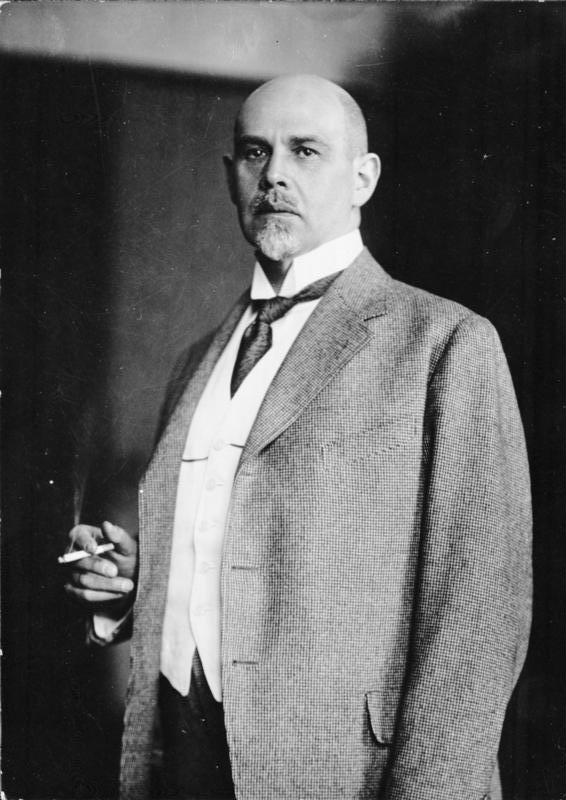

Walther Rathenau (29 September 1867 – 24 June 1922) was a German industrialist, writer and liberal politician.

During the

Rathenau wrote about personal and social responsibility to the community at a time when solidarity was required to keep the peace. His characteristics were courage, vision, imagination, tenacity and creativity; yet he insisted technology come to the aid of manual labourers. So one of the joys of work included "pleasure from profit" to elevate society. According to one biographer he is said to have identified a sense of inferiority in society due to his Jewishness, writing that he:

Rathenau wrote about personal and social responsibility to the community at a time when solidarity was required to keep the peace. His characteristics were courage, vision, imagination, tenacity and creativity; yet he insisted technology come to the aid of manual labourers. So one of the joys of work included "pleasure from profit" to elevate society. According to one biographer he is said to have identified a sense of inferiority in society due to his Jewishness, writing that he:

Rathenau's assassination was but one in a series of terrorist attacks by Organisation Consul. Most notable among them had been the assassination of former finance minister

Rathenau's assassination was but one in a series of terrorist attacks by Organisation Consul. Most notable among them had been the assassination of former finance minister  The terrorists' aims were not achieved, however, and civil war did not come. Instead, millions of Germans gathered on the streets to express their grief and to demonstrate against counter-revolutionary terrorism. When the news of Rathenau's death became known in the Reichstag, the session turned into turmoil.

The terrorists' aims were not achieved, however, and civil war did not come. Instead, millions of Germans gathered on the streets to express their grief and to demonstrate against counter-revolutionary terrorism. When the news of Rathenau's death became known in the Reichstag, the session turned into turmoil.  When the crime was brought to court in October 1922, Ernst Werner Techow was the only defendant charged with murder. Twelve more defendants were arraigned on various charges, among them Hans Gerd Techow and Ernst von Salomon, who had spied out Rathenau's habits and kept up contact with the Organisation Consul, as well as the commander of the Organisation Consul in Western Germany, Karl Tillessen, a brother of Erzberger's assassin Heinrich Tillessen, and his adjutant Hartmut Plaas. The prosecution left aside the political implications of the plot, but focused upon the issue of antisemitism. Ahead of his assassination, Rathenau had indeed been the frequent target of vicious antisemitic attacks, and the assassins had also been members of the violently antisemitic

When the crime was brought to court in October 1922, Ernst Werner Techow was the only defendant charged with murder. Twelve more defendants were arraigned on various charges, among them Hans Gerd Techow and Ernst von Salomon, who had spied out Rathenau's habits and kept up contact with the Organisation Consul, as well as the commander of the Organisation Consul in Western Germany, Karl Tillessen, a brother of Erzberger's assassin Heinrich Tillessen, and his adjutant Hartmut Plaas. The prosecution left aside the political implications of the plot, but focused upon the issue of antisemitism. Ahead of his assassination, Rathenau had indeed been the frequent target of vicious antisemitic attacks, and the assassins had also been members of the violently antisemitic  Initially, the reactions to Rathenau's assassination strengthened the Weimar Republic. The most notable reaction was the enactment of the ' (Law for the Defense of the Republic), which took effect on 22 July 1922. As long as the Weimar Republic existed, the date 24 June remained a day of public commemorations. In public memory, Rathenau's death increasingly appeared to be a martyr-like sacrifice for democracy.

The situation changed with the

Initially, the reactions to Rathenau's assassination strengthened the Weimar Republic. The most notable reaction was the enactment of the ' (Law for the Defense of the Republic), which took effect on 22 July 1922. As long as the Weimar Republic existed, the date 24 June remained a day of public commemorations. In public memory, Rathenau's death increasingly appeared to be a martyr-like sacrifice for democracy.

The situation changed with the

The New Society

' translated by Arthur Windham, (1921) New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co. * ''Der neue Staat'' (1919) * ''Der Kaiser'' (1919) * ''Kritik der dreifachen Revolution'' (1919) * ''Was wird werden'' (1920, a

Walther Rathenau Gesellschaft e. V.

* * *

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rathenau, Walther 1867 births 1922 deaths Assassinated German diplomats Assassinated German politicians Assassinated Jews Businesspeople from Berlin Engineers from Berlin Deaths by firearm in Germany Foreign Ministers of Germany German anti-communists German male writers German science fiction writers German terrorism victims Government ministers of Germany Jewish German politicians Male murder victims Organisation Consul victims People from Steglitz-Zehlendorf People from the Province of Brandenburg People murdered in Berlin Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion Weimar Republic politicians Writers from Berlin 1922 murders in Germany 1920s murders in Berlin

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

of 1914–1918 he was involved in the organization of the German war economy

A war economy or wartime economy is the set of contingencies undertaken by a modern state to mobilize its economy for war production. Philippe Le Billon describes a war economy as a "system of producing, mobilizing and allocating resources t ...

. After the war, Rathenau served as German Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

(February to June 1922) of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

.

Rathenau initiated the 1922 Treaty of Rapallo, which removed major obstacles to trading with Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. Although Russia was already aiding Germany's secret rearmament programme, right-wing nationalist groups branded Rathenau a revolutionary, also resenting his background as a successful Jewish businessman.

Two months after the signing of the treaty, Rathenau was assassinated by the right-wing paramilitary group Organisation Consul

Organisation Consul (O.C.) was an ultra-nationalist and anti-Semitic terrorist organization that operated in the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1922. It was formed by members of the disbanded Freikorps group Marine Brigade Ehrhardt and was respons ...

in Berlin. Some members of the public viewed Rathenau as a democratic martyr; after the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

came to power in 1933 they banned all commemoration of him.

Early life

Rathenau was born inBerlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

to Emil Rathenau

Emil Moritz Rathenau (11 December 1838 – 20 June 1915) was a German entrepreneur, industrialist, mechanical engineer. He was a leading figure in the early European electrical industry.

Early life

Rathenau was born in Berlin, into a w ...

, a prominent Jewish businessman and founder of the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft

Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft AG (AEG; ) was a German producer of electrical equipment founded in Berlin as the ''Deutsche Edison-Gesellschaft für angewandte Elektricität'' in 1883 by Emil Rathenau. During the World War II, Second W ...

(AEG), an electrical engineering company, and Mathilde Nachmann.

He studied physics, chemistry, and philosophy in Berlin and Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

, and received a doctorate in physics in 1889 after studying under August Kundt

August Adolf Eduard Eberhard Kundt (; 18 November 183921 May 1894) was a Germans, German physicist.

Early life

Kundt was born at Schwerin in Mecklenburg. He began his scientific studies at Leipzig, but afterwards went to Berlin University. At fi ...

. His German Jewish

The history of the Jews in Germany goes back at least to the year 321, and continued through the Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (''circa'' 1000–1299 CE) when Jewish immigrants founded the Ashkenazi Jewish ...

heritage and his accumulated wealth were both factors in establishing his deeply divisive reputation in German politics at a time of increasing widespread Antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

.

He summed up his thoughts on growing up Jewish in Germany; communicating how his patriotism and loyalty to his country were no different than that of any fellow German regardless of religion or ethnicity:

I am a German of Jewish origin. My people are the German people, my home is Germany, my faith is German faith, which stands above all denominations.He worked as a technical engineer in a Swiss aluminium factory, and then as a manager in a small electro-chemical firm in

Bitterfeld

Bitterfeld () is a town in the district of Anhalt-Bitterfeld, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Since 1 July 2007 it has been part of the town of Bitterfeld-Wolfen. It is situated approximately 25 km south of Dessau, and 30 km northeast of Halle ( ...

, where he conducted experiments in electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of elements from n ...

. He returned to Berlin and joined the AEG board in 1899, becoming a leading industrialist in the late German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and early Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

periods. In 1903 his younger and much more entrepreneurial brother Erich Rathenau died. Heart-broken, his father had to be satisfied with Walther's help instead. Walther Rathenau was a successful industrialist: in only a decade he set up power stations in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, Buenos Aires, and Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world a ...

. AEG acquired ownership of a streetcar company in Madrid; and in East Africa he purchased a British firm. In total he was involved with 84 companies worldwide. AEG was particularly praised for vertical integration methods and a strong emphasis on supply chain management. Rathenau developed an expertise in business restructuring, turning companies around. High organizational capabilities made his company very rich, and it produced the standards for new chemicals development, such as acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscib ...

in Manchester. He made large profits from commercial lending on a wide industrial scale, and those profits were reinvested in capital and assets.

Supply chains for the World War

An experienced journalist, Rathenau published in the ''Berliner Tageblatt

The ''Berliner Tageblatt'' or ''BT'' was a German language newspaper published in Berlin from 1872 to 1939. Along with the '' Frankfurter Zeitung'', it became one of the most important liberal German newspapers of its time.

History

The ''Berlin ...

'' an article accusing his own country of manipulating politics in Vienna. As the dual monarchy's relations with Russia drifted, the paper described a secret conspiracy at work in Moltke's War department in which he had taken part. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

his opinions hardened. He held senior posts in the Raw Materials Department of the War Ministry and became chairman of AEG upon his father's death in 1915. Rathenau played a key role in convincing the War Ministry to set up the War Raw Materials Department ('' Kriegsrohstoffabteilung'', KRA), of which he was put in charge from August 1914 to March 1915 and established the fundamental policies and procedures. His senior staff were on loan from industry. The KRA focused on raw materials threatened by the British blockade, as well as supplies from occupied Belgium and France. It set prices and regulated the distribution to vital war industries. It began the development of '' Ersatzkaisertum'' raw materials, developing supply chains to bring peace and for regime change within Germany. The KRA suffered many inefficiencies caused by the complexity and selfishness encountered from commerce, industry, and the government itself.

Personal character

Rathenau wrote about personal and social responsibility to the community at a time when solidarity was required to keep the peace. His characteristics were courage, vision, imagination, tenacity and creativity; yet he insisted technology come to the aid of manual labourers. So one of the joys of work included "pleasure from profit" to elevate society. According to one biographer he is said to have identified a sense of inferiority in society due to his Jewishness, writing that he:

Rathenau wrote about personal and social responsibility to the community at a time when solidarity was required to keep the peace. His characteristics were courage, vision, imagination, tenacity and creativity; yet he insisted technology come to the aid of manual labourers. So one of the joys of work included "pleasure from profit" to elevate society. According to one biographer he is said to have identified a sense of inferiority in society due to his Jewishness, writing that he:

realised completely for the first time that he had come into this world as a second-class citizen and that no amount of ability and merit could ever free him from this condition.One heavy criticism which he bore was the implication that Jews could never put Germany first; the idea that the Jews were "our misfortune", as the German nationalist historian

Heinrich Treitschke

Heinrich Gotthard Freiherr von Treitschke (; 15 September 1834 – 28 April 1896) was a German historian, political writer and National Liberal member of the Reichstag during the time of the German Empire. He was an extreme nationalist, who fav ...

wrote, led to the proliferation from 1880s of anti-Semitic parties. There were no Jewish officers in the whole Prussian Army – the ruling-class in the Imperial Officer Corps was both blatantly and latently anti-Semitic, eventually supporting the Nazis' anti-Semitic policies.

After Versailles (1919) he founded a "League for Industry", an offshoot of internationalism that blamed German defeat on a lack of industrial readiness. He wished to exculpate the blame for Germany's war guilt articulated through an acquaintance with Colonel House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his rank was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a highl ...

.

Postwar statesman

Rathenau was a moderate liberal in politics, and after World War I, he was one of the founders of theGerman Democratic Party

The German Democratic Party (, or DDP) was a center-left liberal party in the Weimar Republic. Along with the German People's Party (, or DVP), it represented political liberalism in Germany between 1918 and 1933. It was formed in 1918 from the ...

(German: Deutsche Demokratische Partei, DDP), but he moved to the Left in the advent of post-war chaos. Passionate about rights of social equality, he rejected state ownership of industry and instead advocated greater worker participation in the management of companies. His ideas were influential in postwar governments. He was put forward as a socialist candidate for first President; but on standing in the Reichstag was dismissed amid "rows and shrieks of laughter" which visibly upset the man. Ebert's election by the Left failed to heal the deep rifts and social divisions in German society that occurred throughout the Weimar. Rathenau advised that a small town in central Germany was the wrong place for the capital and seat of Government. But his own adequacy was under-appreciated; immediately giving rise to extreme right-wing organizations within months of the Communist-inspired Spartacist Revolt, "the product of a state in which for centuries no one has ruled who was not a member of, or a convert to military feudalism...," he told the Reichstag, at once deploring the foundation of the Fatherland Party in 1917. In 1918 he established the ZAG living through his philosophy of Deutsche Gemeinwirtschaft a collective economic community.

Rathenau encouraged free traders and believed in the efficacy of "preparedness and directional efficiency". AEG was influential: his colleague Wichard von Moellendorff was appointed as Undersecretary of the Reich Economy Office; for a time in July 1919 they worked closely for Weimar with republican Rudolf Wissell

Rudolf Wissell (8 March 1869 – 13 December 1962) was a German politician in the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). During the Weimar Republic, he held office as the Minister for Economic Affairs and Minister for Labour.

Early lif ...

. But Hindenburg's technocratic rational economic Programme was borrowed; while Rathenau, being democratic, warned against short-termism. Berlin's March Days

The March Days or March Events () was a period of inter-ethnic strife and clashes which led to the death of about 12,000 Azerbaijani: "The results of the March events were immediate and total for the Musavat. Several hundreds of its members wer ...

was a consequence of the internal struggle between Finance and Economic ministries. On 20 February 1919 he proposed workers councils. The plan for a Socialist League of nations was overtly pro-Union mocked as the "Paris League" – a throwback to the Second Communist International – they challenged openly for democratic ideas. But a rapprochement with Soviet Union was inspired by Rathenau; it tried to prevent an expansive 'Greater Germany'.

Rathenau was appointed Minister of Reconstruction and in May 1921 held a second meeting with Lloyd George and the Reparations Committee. He established good relations with Aristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

who praised "a strong, healthy, booming Germany". The era of ''Erfüllungspolitik'' was high, altruistic self-confidence; he shared a pre-war fascination for the Hegelian Complex for a corporate Germany chastised by a reverence to a Supreme Being. He was wary of allied decadence, complacent, corrosive of an innocent romanticism expanded into mysticism. His ideas were challenged as "objectively impossible"; Weimar lacked clarity and leadership, while Rathenau was deterministic, and robust over the details. A ''Levée en masse'' would be part of this utilitarianism that bestrode his ''Menschen'' philosophies. This contradistinction about an "unravelled" Versailles which was incompatible with Fulfillment and the role of Reconstruction. Bravely Rathenau held out against the partition of Poland, despite Erzberger's assassination; and threats for extreme National Bolshevists when he joined Joseph Wirth's government after Cannes on 31 January 1922 led to a horrible fear that his days were numbered.

In 1922 he became Foreign Minister. Writing before the Genoa Conference that concern for his personal safety was prescient of a foreboding for his own death. The insistence that Germany should fulfill its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, but work for a revision of its terms, infuriated extreme German nationalists. He also angered such extremists by negotiating the Treaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugoslav ...

with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, which was signed on 16 April 1922, although the treaty implicitly recognized secret German–Soviet collaboration begun in 1921 that provided for the rearmament of Germany, including German-owned aircraft being manufactured in Russian territory. The leaders of the (still obscure) National Socialist German Workers' Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

(German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, abbreviated NSDAP) and other extremist groups falsely claimed he was part of a " Jewish-Communist conspiracy," despite the fact that he was a liberal German nationalist who had bolstered the country's recent war effort. The British politician Robert Boothby

Robert John Graham Boothby, Baron Boothby, (12 February 1900 – 16 July 1986), often known as Bob Boothby, was a British Conservative politician.

Early life

The only son of Sir Robert Tuite Boothby, KBE, of Edinburgh and a cousin of Rosalind ...

wrote of him, "He was something that only a German Jew could simultaneously be: a prophet, a philosopher, a mystic, a writer, a statesman, an industrial magnate of the highest and greatest order, and the pioneer of what has become known as 'industrial rationalization'." Despite his desire for economic and political co-operation between Germany and the Soviet Union, Rathenau remained skeptical of the methods of the Soviets:

The question of war reparations vexed Rathenau: Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles

Article often refers to:

* Article (grammar), a grammatical element used to indicate definiteness or indefiniteness

* Article (publishing), a piece of nonfictional prose that is an independent part of a publication

Article may also refer to:

G ...

imposed repayments that would take Germany decades to repay. Expunging war guilt, converting it into financial and economic responsibility was critical to relations with the Big Four. Yet Rathenau was unable to convince Germans of its applicability. He talked in his "apocalyptic way about society, politics and the problems of responsibility." He was persuasive; the Entente would recognise, he urged, that Germany had to be "capable of discharging its obligations."

Philosophy of imagery

Philosopher for socialism

Although he never married, Rathenau did fall in love with Elisabeth 'Lili' Franziska Deutsch, (née Kahn), a society beauty and the wife of his father's business partner Felix Deutsch. She was the daughter of Bernhard and Emma Kahn (née Eberstadt) of Mannheim and the sister of, among others, composer Robert Kahn and Wall St. financierOtto Hermann Kahn

Otto Hermann Kahn (February 21, 1867 – March 29, 1934) was a German-born American investment banker, collector, philanthropist, and patron of the arts. Kahn was a well-known figure, appearing on the cover of ''Time'' magazine and was sometimes ...

. He related in a notebook titled ''Brevarium Mysticum'' finding revealed love in the sight of a soaring eagle, a soulful dedication on a sojourn in the Harz Mountains. Walther was highly literate and intelligent, wrote several books with deep philosophical overtones. In ''Zur Kritik der Zeit'' contemporary human conditioning was critically examined on a sociological basis found in a life of business. This put together another critique into an intellectual context of 'mind over matter', social wisdom and corporate discipline as a framework in the socialistic sciences – ''Zur Mechanik des Geistes''. Rathenau moved ever closer to a rejection of religion, embracing the power of science. He tried to bring people's attention to what changes would be required for a futuristic romantic movement in ''Von Kommenden Dingen'' to openly challenge the living of lives. Mechanistics rejected the central feature of Malthusian thoughts on human progress motivated by population growth. His focus was the importance of technology, rather than abstinence for standardisation, specialization and abstraction with positive approbation. The corollary for Rathenau of information-gathering was an exponential explosive growth in data that would enrich globalization. Rathenau delineated his arguments by dividing men into classifications: ''Mutmenschen'' and ''Furchtmenschen'' outlined the problems of mass migration across Europe which had resonance with the past. But he saw real significance for ''Zweckmenschen'' as utilitarian cunning to set the men of fear in motion. The philosophy amounted to Social Darwinism but there was an unaccredited presumption of delphic adoration for the Greek ''Parnassus

Mount Parnassus (; el, Παρνασσός, ''Parnassós'') is a mountain range of central Greece that is and historically has been especially valuable to the Greek nation and the earlier Greek city-states for many reasons. In peace, it offers ...

''.

The theories of mechanization argued that competition could not go on forever as it died in love. Intellectual perorations were reached in pronouncements preceding a great vision for the future of German business. He cannot be directly held responsible for the mechanization of the Panzers movement, for his social idealism was grounded in Rousseau's Great Enlightenment Path. Pure mechanization would have to transmogrify psychological mutation, risk tragedy, and plunging into the abyss. Rathenau was assimilated by a love for St Francis Assisi, a message of service dedicated to the community that restricted his ambitions. A modified or applied mysticism, Rathenau's idea always expressed work as "a joy", and like Schopenhauer he rejected materialism and recognised its pitfalls, using a deep knowledge of technology to simultaneously warn of its dangers. This distinction with Soviet working methods of dialectical materialism was unwelcome in a Germany seeking to rearm. Thus he rallied ideas for management and control as Head of Raw Materials and efficacy of science.

Assassination and aftermath

On 24 June 1922, two months after the signing of theTreaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugoslav ...

(which renounced German territorial claims from World War I), Rathenau was assassinated. On this Saturday morning, Rathenau had himself chauffeured from his house in Berlin-Grunewald

Grunewald () is a locality (''Ortsteil'') within the Berlin borough (''Bezirk'') of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Famous for the homonymous forest, until 2001 administrative reform it was part of the former district of Wilmersdorf.

Next to Licht ...

to the Foreign Office in Wilhelmstraße

Wilhelmstrasse (german: Wilhelmstraße, see ß) is a major thoroughfare in the central Mitte (locality), Mitte and Kreuzberg districts of Berlin, Germany. Until 1945, it was recognised as the centre of the government, first of the Kingdom of Pru ...

. During the trip, his NAG Convertible

A convertible or cabriolet () is a passenger car that can be driven with or without a roof in place. The methods of retracting and storing the roof vary among eras and manufacturers.

A convertible car's design allows an open-air driving expe ...

was passed by a Mercedes touring car

Touring car and tourer are both terms for open cars (i.e. cars without a fixed roof).

"Touring car" is a style of open car built in the United States which seats four or more people. The style was popular from the early 1900s to the 1930s.

Th ...

with Ernst Werner Techow

Ernst Werner Techow (12 October 1901 – 9 May 1945) was a German right-wing assassin. In 1922, he took part in the assassination of the Foreign Minister of Germany Walther Rathenau. After his release from prison Techow initially joined the Nazi p ...

behind the wheel and Erwin Kern and Hermann Fischer in the backseats. Kern opened fire with an MP 18

The MP 18, manufactured by Theodor Bergmann ''Abteilung Waffenbau'', was arguably the first submachine gun used in combat. It was introduced into service in 1918 by the German Army during World War I as the primary weapon of the '' Sturmtruppen ...

submachine gun

A submachine gun (SMG) is a magazine-fed, automatic carbine designed to fire handgun cartridges. The term "submachine gun" was coined by John T. Thompson, the inventor of the Thompson submachine gun, to describe its design concept as an autom ...

at close range, killing Rathenau almost instantly, while Fischer threw a hand grenade into the car before Techow quickly drove them away. Also involved in the plot were Techow's younger brother Hans Gerd Techow, future writer Ernst von Salomon

Ernst von Salomon (25 September 1902 – 9 August 1972) was a German novelist and screenwriter. He was a Weimar-era national-revolutionary activist and right-wing Freikorps member.

Family and education

He was born in Kiel, in the Prussian prov ...

, and Willi Günther (aided and abetted by seven others, some of them schoolboys). All conspirators were members of the ultra-nationalist secret Organisation Consul

Organisation Consul (O.C.) was an ultra-nationalist and anti-Semitic terrorist organization that operated in the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1922. It was formed by members of the disbanded Freikorps group Marine Brigade Ehrhardt and was respons ...

(O.C.). A memorial stone in the Königsallee in Grunewald marks the scene of the crime.

Rathenau's assassination was but one in a series of terrorist attacks by Organisation Consul. Most notable among them had been the assassination of former finance minister

Rathenau's assassination was but one in a series of terrorist attacks by Organisation Consul. Most notable among them had been the assassination of former finance minister Matthias Erzberger

Matthias Erzberger (20 September 1875 – 26 August 1921) was a German writer and politician (Centre Party), the minister of Finance from 1919 to 1920.

Prominent in the Catholic Centre Party, he spoke out against World War I from 1917 and as a ...

in August 1921. While Fischer and Kern prepared their plot, former chancellor Philipp Scheidemann

Philipp Heinrich Scheidemann (26 July 1865 – 29 November 1939) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). In the first quarter of the 20th century he played a leading role in both his party and in the young Weimar ...

barely survived an attempt on his life by Organisation Consul assassins on 4 June 1922. Historian Martin Sabrow points to Hermann Ehrhardt

Hermann Ehrhardt (29 November 1881 – 27 September 1971) was a German naval officer in World War I who became an anti-republican and anti-Semitic German nationalist Freikorps leader during the Weimar Republic. As head of the Marinebrigade E ...

, the undisputed leader of the Organisation Consul, as the one who ordered the murders. Ehrhardt and his men believed that Rathenau's death would bring down the government and prompt the Left to act against the Weimar Republic, thereby provoking civil war, in which the Organisation Consul would be called on for help by the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

. After an anticipated victory Ehrhardt hoped to establish an authoritarian regime or a military dictatorship. In order not to be completely delegitimized by the murder of Rathenau, Ehrhardt carefully saw to it that no connections between him and the assassins could be detected. Although Fischer and Kern connected with the Berlin chapter of the Organisation Consul to use its resources, they mainly acted on their own in planning and carrying out the assassination.The historian Michael Kellogg, argued that Vasily Biskupsky

Vasily Viktorovich Biskupsky (russian: Василий Викторович Бискупский; ukr, Василь Вікторович Біскупський; 27 June 1878 – 17 June 1945) was a general in the Russian and Ukrainian armies ...

, Erich Ludendorff

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff (9 April 1865 – 20 December 1937) was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. ...

and his advisor Max Bauer

Colonel Max Hermann Bauer (31 January 1869 – 6 May 1929) was a German General Staff officer and artillery expert in the First World War. As a protege of Erich Ludendorff he was placed in charge of the German Army's munition supply by the la ...

, all members of the Aufbau Vereinigung

The Aufbau Vereinigung (Reconstruction Organisation) was a Munich-based counterrevolutionary conspiratorial group formed in the aftermath of the German occupation of Ukraine in 1918 and of the Latvian Intervention of 1919. It brought together W ...

, a group of tsarist exiles and early Nazis, colluded in the assassination of Rathenau, while the degree of their participation was not entirely clear.

The terrorists' aims were not achieved, however, and civil war did not come. Instead, millions of Germans gathered on the streets to express their grief and to demonstrate against counter-revolutionary terrorism. When the news of Rathenau's death became known in the Reichstag, the session turned into turmoil.

The terrorists' aims were not achieved, however, and civil war did not come. Instead, millions of Germans gathered on the streets to express their grief and to demonstrate against counter-revolutionary terrorism. When the news of Rathenau's death became known in the Reichstag, the session turned into turmoil. DNVP

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...

politician Karl Helfferich

Karl Theodor Helfferich (22 July 1872 – 23 April 1924) was a German politician, economist, and financier from Neustadt an der Weinstraße in the Palatinate.

Biography

Helfferich studied law and political science at the universities of Munich, ...

in particular became the target of scorn because he had just recently uttered a vitriolic attack upon Rathenau. During the official memorial ceremony the next day, Chancellor Joseph Wirth

Karl Joseph Wirth (6 September 1879 – 3 January 1956) was a German politician of the Catholic Centre Party who served for one year and six months as the chancellor of Germany from 1921 to 1922, as the finance minister from 1920 to 1921, a ...

from the Centre Party made a speech which soon became famous, in which, while pointing to the right side of the parliamentary floor, he used the well known formula of Philipp Scheidemann: "There is the enemy – and there is no doubt about it: This enemy is on the right!"

The crime itself was soon cleared up. Willi Günther had bragged about his participation in public. After his arrest on 26 June, he confessed to the crime without holding anything back. Hans Gerd Techow was arrested the following day, Ernst Werner Techow, who was visiting his uncle, three days later. Fischer and Kern, however, remained on the loose. After a daring flight, which kept Germany in suspense for more than two weeks, they were finally spotted at Saaleck Castle

Saaleck Castle (german: Burg Saaleck) is a hill castle near Bad Kösen, now a part of Naumburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.

In 1922, two of the men who had killed Walther Rathenau, the foreign minister of Germany, hid at Saaleck Castle but were tra ...

in Thuringia, whose owner was himself a secret member of the Organisation Consul. On 17 July, they were confronted by two police detectives. While waiting for reinforcements during the stand-off, one of the detectives fired at a window, unknowingly killing Kern by a bullet in the head. Fischer then took his own life.

When the crime was brought to court in October 1922, Ernst Werner Techow was the only defendant charged with murder. Twelve more defendants were arraigned on various charges, among them Hans Gerd Techow and Ernst von Salomon, who had spied out Rathenau's habits and kept up contact with the Organisation Consul, as well as the commander of the Organisation Consul in Western Germany, Karl Tillessen, a brother of Erzberger's assassin Heinrich Tillessen, and his adjutant Hartmut Plaas. The prosecution left aside the political implications of the plot, but focused upon the issue of antisemitism. Ahead of his assassination, Rathenau had indeed been the frequent target of vicious antisemitic attacks, and the assassins had also been members of the violently antisemitic

When the crime was brought to court in October 1922, Ernst Werner Techow was the only defendant charged with murder. Twelve more defendants were arraigned on various charges, among them Hans Gerd Techow and Ernst von Salomon, who had spied out Rathenau's habits and kept up contact with the Organisation Consul, as well as the commander of the Organisation Consul in Western Germany, Karl Tillessen, a brother of Erzberger's assassin Heinrich Tillessen, and his adjutant Hartmut Plaas. The prosecution left aside the political implications of the plot, but focused upon the issue of antisemitism. Ahead of his assassination, Rathenau had indeed been the frequent target of vicious antisemitic attacks, and the assassins had also been members of the violently antisemitic Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund

The ''Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund'' (English: German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation) was the largest, and most active anti-semitic federation in Germany after the First World War,Beurteilung des Reichskommissars für � ...

. Kern had, according to Ernst Werner Techow, argued that Rathenau had to be murdered, because he had intimate relations with Bolshevik Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, so that he had even married off his sister to the Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

Karl Radek – a complete fabrication – and that Rathenau himself had confessed to be one of the three hundred "Elders of Zion" as described in the notorious antisemitic forgery ''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' () or ''The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The hoax was plagiarized from several ...

''. But the defendants vigorously denied that they had killed Rathenau because he was Jewish. Neither was the prosecution able to fully uncover the involvement of the Organisation Consul in the plot. Thus Tillessen and Plaas were only convicted of non-notification of a crime and sentenced to three and two years in prison, respectively. Salomon received five years imprisonment for accessory to murder. Ernst Werner Techow narrowly escaped the death penalty because, in a last-minute confession, he managed to convince the court that he had only acted under the threat of death by Kern. Instead he was sentenced to fifteen years in prison for being an accessory to murder.

Initially, the reactions to Rathenau's assassination strengthened the Weimar Republic. The most notable reaction was the enactment of the ' (Law for the Defense of the Republic), which took effect on 22 July 1922. As long as the Weimar Republic existed, the date 24 June remained a day of public commemorations. In public memory, Rathenau's death increasingly appeared to be a martyr-like sacrifice for democracy.

The situation changed with the

Initially, the reactions to Rathenau's assassination strengthened the Weimar Republic. The most notable reaction was the enactment of the ' (Law for the Defense of the Republic), which took effect on 22 July 1922. As long as the Weimar Republic existed, the date 24 June remained a day of public commemorations. In public memory, Rathenau's death increasingly appeared to be a martyr-like sacrifice for democracy.

The situation changed with the Nazi seizure of power

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

in 1933. The Nazis systematically wiped out public commemoration of Rathenau by destroying monuments to him, closing the Walther-Rathenau-Museum in his former mansion, and renaming streets and schools dedicated to him. Instead, a memorial plate to Kern and Fischer was solemnly unveiled at Saaleck Castle

Saaleck Castle (german: Burg Saaleck) is a hill castle near Bad Kösen, now a part of Naumburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.

In 1922, two of the men who had killed Walther Rathenau, the foreign minister of Germany, hid at Saaleck Castle but were tra ...

in July 1933 and in October 1933, a monument was erected on the assassins' grave.

The Nuremberg U-Bahn

The Nuremberg U-Bahn is a rapid transit system run by '' Verkehrs-Aktiengesellschaft Nürnberg'' (VAG; Nuremberg Transport Corporation), which itself is a member of the ''Verkehrsverbund Großraum Nürnberg'' (VGN; Greater Nuremberg Transport Net ...

station Rathenauplatz is not only named after him but also bears his face in portrait along the walls.

Fictional portrayal

Rathenau is generally acknowledged to be, in part, the basis for the German noble and industrialist Paul Arnheim, a character in Robert Musil's novel ''The Man Without Qualities

''The Man Without Qualities'' (german: Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften; 1930–1943) is an unfinished modernist novel in three volumes and various drafts, by the Austrian writer Robert Musil.

The novel is a "story of ideas", which takes place in ...

''. Rathenau also appears as the ghostly subject of a Nazi seance in a famous scene in Thomas Pynchon's ''Gravity%27s Rainbow

''Gravity's Rainbow'' is a 1973 novel by American writer Thomas Pynchon. The narrative is set primarily in Europe at the end of World War II and centers on the design, production and dispatch of V-2 rockets by the German military. In particular, ...

.'' In 2017, the events and aftermath of Rathenau's assassination were depicted in the first episode of the National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widely ...

series ''Genius

Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for future works, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabiliti ...

''.

Works

* ''Reflektionen'' (1908) * ''Zur Kritik der Zeit'' (1912) * ''Zur Mechanik des Geistes'' (1913) * ''Von kommenden Dingen'' (1917) * ''Vom Aktienwesen. Eine geschäftliche Betrachtung'' (1917) * ''An Deutschlands Jugend'' (1918) * ''Die neue Gesellschaft'' (1919)The New Society

' translated by Arthur Windham, (1921) New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co. * ''Der neue Staat'' (1919) * ''Der Kaiser'' (1919) * ''Kritik der dreifachen Revolution'' (1919) * ''Was wird werden'' (1920, a

utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', describing a fictional ...

n novel)

* ''Gesammelte Schriften'' (6 volumes)

* ''Gesammelte Reden'' (1924)

* ''Briefe'' (1926, 2 volumes)

* ''Neue Briefe'' (1927)

* ''Politische Briefe'' (1929)

See also

*Contributions to liberal theory

Contribution or Contribute may refer to:

* ''Contribution'' (album), by Mica Paris (1990)

** "Contribution" (song), title song from the album

*Contribution (law), an agreement between defendants in a suit to apportion liability

*Contributions, a ...

* 1920s Berlin

* Liberalism

Explanatory notes

References

Secondary sources

* Berger, Stefan, Inventing the Nation: Germany London: Hodder, 2004. * . * * Gilbert, Sir Martin, ''The First World War: A Complete History'' (London, 1971) * * * * * Pois, Robert A. "Walther Rathenau's Jewish Quandary," ''Leo Baeck Institute Year Book'' (1968), Vol. 13, pp 120–131. * * Strachan, Hew, ''The First World War: Volume I: To Arms'' (2001) pp 1014–49 on Rathenau and KRA in the war * * Wehler, Hans-Ulrich, The German Empire 1871–1918 Leamington: Berg, 1985. * Williamson, D. G. "Walther Rathenau and the K.R.A. August 1914 – March 1915," ''Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte'' (1978) Issue 11, pp. 118–136.Primary sources

* ''Vossiche Zeitung'' – a newspaper * ''Tagebuch 1907–22'' (Düsseldorf, 1967) * Count Harry Kessler, ''Berlin in Lights: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler (1918–1937)'' Grove Press, New York, (1999). * W Rathenau, Die Mechanisierung der Welt (Fr.) (Paris 1972) * W Rathenau, Schriften und Reden (Frankfurt-am-Main 1964) * W Rathenau, The Sacrifice to the Eumenides (1913) * ''Walter Rathenau: Industrialist, Banker, Intellectual, And Politician; Notes And Diaries 1907–1922''. Hartmut P. von Strandmann (ed.), Hilary von Strandmann (translator). Clarendon Press, 528 pages, in English. October 1985. (hardcover).Further reading

*External links

Walther Rathenau Gesellschaft e. V.

* * *

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rathenau, Walther 1867 births 1922 deaths Assassinated German diplomats Assassinated German politicians Assassinated Jews Businesspeople from Berlin Engineers from Berlin Deaths by firearm in Germany Foreign Ministers of Germany German anti-communists German male writers German science fiction writers German terrorism victims Government ministers of Germany Jewish German politicians Male murder victims Organisation Consul victims People from Steglitz-Zehlendorf People from the Province of Brandenburg People murdered in Berlin Soldiers of the French Foreign Legion Weimar Republic politicians Writers from Berlin 1922 murders in Germany 1920s murders in Berlin