Virioplankton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as

Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as  Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License

When not inside a cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent particles called ''

Bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called

Bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called

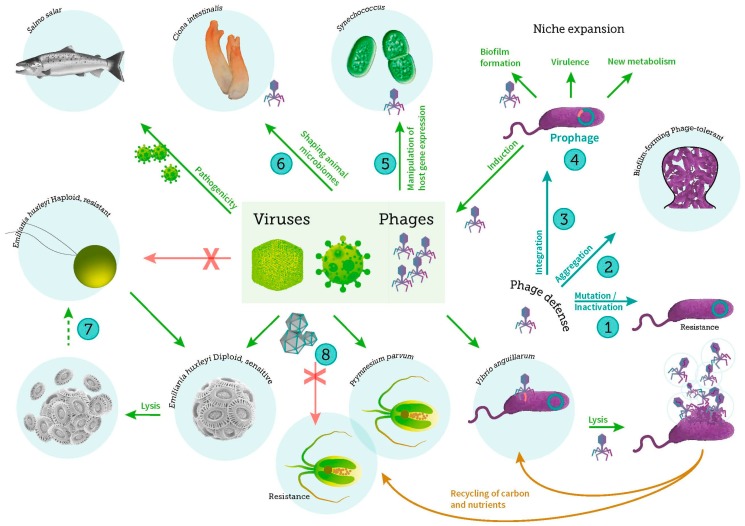

Microbes drive the nutrient transformations that sustain Earth's ecosystems, and the viruses that infect these microbes modulate both microbial population size and diversity. The

Microbes drive the nutrient transformations that sustain Earth's ecosystems, and the viruses that infect these microbes modulate both microbial population size and diversity. The  For a long time, tailed phages of the order ''Caudovirales'' seemed to dominate marine ecosystems in number and diversity of organisms. However, as a result of more recent research, non-tailed viruses appear to dominate multiple depths and oceanic regions. These non-tailed phages also infect marine bacteria, and include the families ''

For a long time, tailed phages of the order ''Caudovirales'' seemed to dominate marine ecosystems in number and diversity of organisms. However, as a result of more recent research, non-tailed viruses appear to dominate multiple depths and oceanic regions. These non-tailed phages also infect marine bacteria, and include the families ''

Archaean viruses replicate within

Archaean viruses replicate within

''Phycodnaviridae'' play important ecological roles by regulating the growth and productivity of their algal hosts. Algal species such ''

''Phycodnaviridae'' play important ecological roles by regulating the growth and productivity of their algal hosts. Algal species such ''

File:Electron microscopic image of a mimivirus - journal.ppat.1000087.g007 crop.png,

File:CroV TEM (cropped).jpg, Cryo-electron micrograph of the

scale bar=0.2 µm

The discovery and subsequent characterization of giant viruses has triggered some debate concerning their evolutionary origins. The two main hypotheses for their origin are that either they evolved from small viruses, picking up DNA from host organisms, or that they evolved from very complicated organisms into the current form which is not self-sufficient for reproduction. What sort of complicated organism giant viruses might have diverged from is also a topic of debate. One proposal is that the origin point actually represents a fourth

The dominant hosts for viruses in the ocean are marine microorganisms, such as bacteria. Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals, and are essential to the regulation of marine and freshwater ecosystems are important mortality agents of

The dominant hosts for viruses in the ocean are marine microorganisms, such as bacteria. Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals, and are essential to the regulation of marine and freshwater ecosystems are important mortality agents of  Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments. On average there are about ten million of them in one milliliter of seawater. Most of these viruses are

Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments. On average there are about ten million of them in one milliliter of seawater. Most of these viruses are

Marine surface habitats sit at the interface between the atmosphere and the ocean. The biofilm-like habitat at the surface of the ocean harbours surface-dwelling microorganisms, commonly referred to as

Marine surface habitats sit at the interface between the atmosphere and the ocean. The biofilm-like habitat at the surface of the ocean harbours surface-dwelling microorganisms, commonly referred to as

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

The polar regions are characterised by truncated food webs, and the role of viruses in ecosystem function is likely to be even greater than elsewhere in the

Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as

Marine viruses are defined by their habitat as virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es that are found in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater

Saline water (more commonly known as salt water) is water that contains a high concentration of dissolved salts (mainly sodium chloride). On the United States Geological Survey (USGS) salinity scale, saline water is saltier than brackish water, ...

of seas or oceans or the brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

water of coastal estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

. Viruses are small infectious agent

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

s that can only replicate inside the living cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

of a host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

*Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

* Michel Host ...

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

, because they need the replication machinery of the host to do so. They can infect all types of life forms

Life form (also spelled life-form or lifeform) is an entity that is living, such as plants (flora) and animals (fauna). It is estimated that more than 99% of all species that ever existed on Earth, amounting to over five billion species, are ex ...

, from animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s and plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s to microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s, including bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License

When not inside a cell or in the process of infecting a cell, viruses exist in the form of independent particles called ''

virion

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

s''. A virion contains a genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

(long molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

s that carry genetic information in the form of either DNA or RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

) surrounded by a capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

(a protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

coat protecting the genetic material). The shapes of these virus particles range from simple helical

Helical may refer to:

* Helix, the mathematical concept for the shape

* Helical engine, a proposed spacecraft propulsion drive

* Helical spring, a coilspring

* Helical plc, a British property company, once a maker of steel bar stock

* Helicoil

A t ...

and icosahedral

In geometry, an icosahedron ( or ) is a polyhedron with 20 faces. The name comes and . The plural can be either "icosahedra" () or "icosahedrons".

There are infinitely many non- similar shapes of icosahedra, some of them being more symmetrica ...

forms for some virus species to more complex structures for others. Most virus species have virions that are too small to be seen with an optical microscope

The optical microscope, also referred to as a light microscope, is a type of microscope that commonly uses visible light and a system of lenses to generate magnified images of small objects. Optical microscopes are the oldest design of microsco ...

. The average virion is about one one-hundredth the linear size of the average bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

.

A teaspoon of seawater typically contains about fifty million viruses. Most of these viruses are bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

s which infect and destroy marine bacteria

Marine prokaryotes are marine bacteria and marine archaea. They are defined by their habitat as prokaryotes that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. All cellular ...

and control the growth of phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

Ph ...

at the base of the marine food web

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have biomass pyramids which are inverted at the base. In particular, the biomass of consumers (copepods, krill, shrimp, forage fish) is larger than the biomass of primary producers. This ...

. Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals but are essential to the regulation of marine ecosystems. They supply key mechanisms for recycling ocean carbon and nutrients

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow, and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excret ...

. In a process known as the viral shunt

The viral shunt is a mechanism that prevents marine microbial particulate organic matter (POM) from migrating up trophic levels by recycling them into dissolved organic matter (DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms. The DOM rec ...

, organic molecules released from dead bacterial cells stimulate fresh bacterial and algal growth. In particular, the breaking down of bacteria by viruses (lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

) has been shown to enhance nitrogen cycling

The nitrogen cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into multiple chemical forms as it circulates among atmospheric, terrestrial, and marine ecosystems. The conversion of nitrogen can be carried out through both biolog ...

and stimulate phytoplankton growth. Viral activity also affects the biological pump

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments.Sigman DM & GH ...

, the process which sequesters carbon in the deep ocean. By increasing the amount of respiration in the oceans, viruses are indirectly responsible for reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by approximately 3 gigatonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton (United States c ...

s of carbon per year.

Marine microorganisms

Marine microorganisms are defined by their habitat as microorganisms living in a marine environment, that is, in the saltwater of a sea or ocean or the brackish water of a coastal estuary. A microorganism (or microbe) is any microscopic living ...

make up about 70% of the total marine biomass

The biomass is the mass of living biological organisms in a given area or ecosystem at a given time. Biomass can refer to ''species biomass'', which is the mass of one or more species, or to ''community biomass'', which is the mass of all spe ...

. It is estimated marine viruses kill 20% of the microorganism biomass every day. Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmful algal bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in freshwater or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompas ...

s which often kill other marine life

Marine life, sea life, or ocean life is the plants, animals and other organisms that live in the salt water of seas or oceans, or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. At a fundamental level, marine life affects the nature of the planet. M ...

. The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms. Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

and drives evolution. It is thought viruses played a central role in early evolution before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes, at the time of the last universal common ancestor of life on Earth. Viruses are still one of the largest areas of unexplored genetic diversity on Earth.

Background

Viruses are now recognised as ancient and as having origins that pre-date the divergence of life into the three domains. They are found wherever there is life and have probably existed since living cells first evolved. The origins of viruses in theevolutionary history of life

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest #Origins of life on Earth, emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', fo ...

are unclear because they do not form fossils. Molecular techniques are used to compare the DNA or RNA of viruses and are a useful means of investigating how they arose. Some viruses may have evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

from plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

s—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

, which increases genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

.

Opinions differ on whether viruses are a form of life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

or organic structures that interact with living organisms. They are considered by some to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly, and evolve through natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

. However they lack key characteristics such as a cellular structure generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as replicators and as "organisms at the edge of life".

The existence of viruses in the ocean was discovered through electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

and epifluorescence microscopy

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. "Fluorescence microsc ...

of ecological water samples, and later through metagenomic

Metagenomics is the study of genetic material recovered directly from environmental or clinical samples by a method called sequencing. The broad field may also be referred to as environmental genomics, ecogenomics, community genomics or microb ...

sampling of uncultured viral samples. Marine viruses, although microscopic and essentially unnoticed by scientists

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosophica ...

until recently, are the most abundant and diverse biological entities in the ocean. Viruses have an estimated abundance of 1030 in the ocean, or between 106 and 1011 viruses per millilitre

The litre (international spelling) or liter (American English spelling) (SI symbols L and l, other symbol used: ℓ) is a metric unit of volume. It is equal to 1 cubic decimetre (dm3), 1000 cubic centimetres (cm3) or 0.001 cubic metre (m3). ...

. Quantification of marine viruses was originally performed using transmission electron microscopy but has been replaced by epifluorescence or flow cytometry

Flow cytometry (FC) is a technique used to detect and measure physical and chemical characteristics of a population of cells or particles.

In this process, a sample containing cells or particles is suspended in a fluid and injected into the flo ...

.

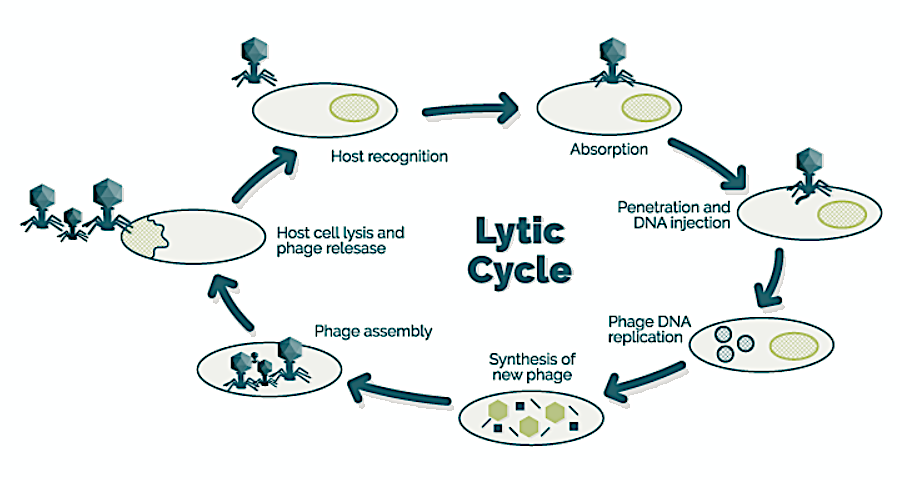

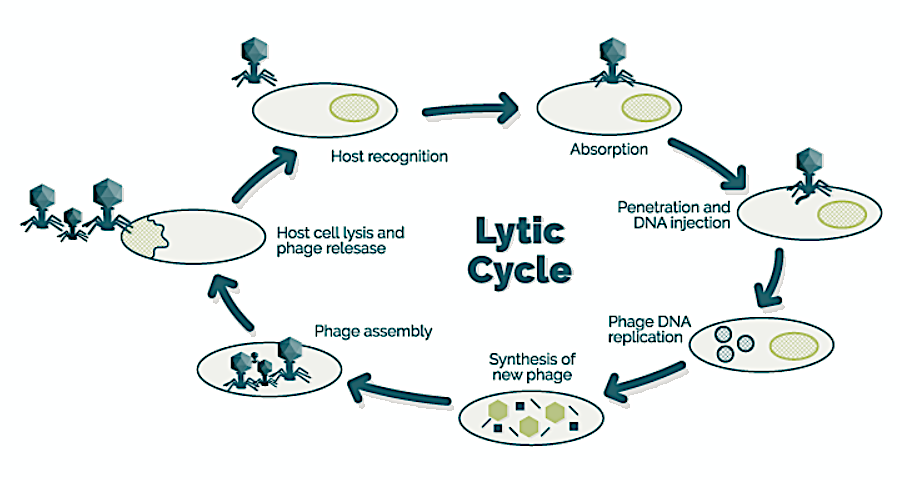

Bacteriophages

Bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

s, often contracted to ''phages'', are viruses that parasitize

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has c ...

bacteria for replication. As aptly named, marine phages parasitize marine bacteria

Marine prokaryotes are marine bacteria and marine archaea. They are defined by their habitat as prokaryotes that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. All cellular ...

, such as cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blu ...

. They are a diverse group of viruses which are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments, because their hosts, bacteria, are typically the numerically dominant cellular life in the sea. There are up to ten times more phages in the oceans than there are bacteria, reaching levels of 250 million bacteriophages per millilitre of seawater. These viruses infect specific bacteria by binding to surface receptor molecules and then entering the cell. Within a short amount of time, in some cases just minutes, bacterial polymerase

A polymerase is an enzyme ( EC 2.7.7.6/7/19/48/49) that synthesizes long chains of polymers or nucleic acids. DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase are used to assemble DNA and RNA molecules, respectively, by copying a DNA template strand using base- ...

starts translating viral mRNA into protein. These proteins go on to become either new virions within the cell, helper proteins, which help assembly of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. Viral enzymes aid in the breakdown of the cell membrane, and there are phages that can replicate three hundred phages twenty minutes after injection.

Bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called

Bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called restriction endonucleases

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or'' restrictase '' is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class o ...

, cut up the viral DNA that bacteriophages inject into bacterial cells. Bacteria also contain a system that uses CRISPR

CRISPR () (an acronym for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea. These sequences are derived from DNA fragments of bacte ...

sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of viruses that the bacteria have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block the virus's replication through a form of RNA interference

RNA interference (RNAi) is a biological process in which RNA molecules are involved in sequence-specific suppression of gene expression by double-stranded RNA, through translational or transcriptional repression. Historically, RNAi was known by o ...

. This genetic system provides bacteria with acquired immunity

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system ...

to infection.

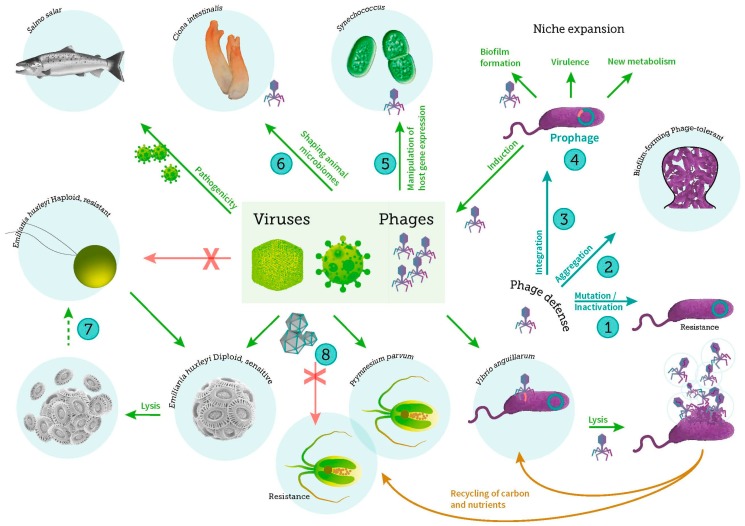

Microbes drive the nutrient transformations that sustain Earth's ecosystems, and the viruses that infect these microbes modulate both microbial population size and diversity. The

Microbes drive the nutrient transformations that sustain Earth's ecosystems, and the viruses that infect these microbes modulate both microbial population size and diversity. The cyanobacterium

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blue ...

''Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosynth ...

'', the most abundant oxygenic phototroph

Phototrophs () are organisms that carry out photon capture to produce complex organic compounds (e.g. carbohydrates) and acquire energy. They use the energy from light to carry out various cellular metabolic processes. It is a common misconcep ...

on Earth, contributes a substantial fraction of global primary carbon production, and often reaches densities of over 100,000 cells per milliliter in oligotrophic

An oligotroph is an organism that can live in an environment that offers very low levels of nutrients. They may be contrasted with copiotrophs, which prefer nutritionally rich environments. Oligotrophs are characterized by slow growth, low rates of ...

and temperate oceans. Hence, viral (cyanophage) infection and lysis of ''Prochlorococcus'' represent an important component of the global carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and Earth's atmosphere, atmosphere of the Earth. Carbon is the main component of biological compounds as well as ...

. In addition to their ecological role in inducing host mortality, cyanophages influence the metabolism and evolution of their hosts by co-opting and exchanging genes, including core photosynthesis genes.

Corticoviridae

''Corticovirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family '' Corticoviridae''. Corticoviruses are bacteriophages; that is, their natural hosts are bacteria. The genus contains two species. The name is derived from Latin ''cortex'', ''corticis'' (mea ...

'',

''Inoviridae

Filamentous bacteriophage is a family of viruses (''Inoviridae'') that infect bacteria. The phages are named for their filamentous shape, a worm-like chain (long, thin and flexible, reminiscent of a length of cooked spaghetti), about 6 nm ...

'',

''Microviridae

''Microviridae'' is a family of bacteriophages with a single-stranded DNA genome. The name of this family is derived from the ancient Greek word (), meaning "small". This refers to the size of their genomes, which are among the smallest of the ...

'' and ''Autolykiviridae''.

Archaeal viruses

Archaean viruses replicate within

Archaean viruses replicate within archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

: these are double-stranded DNA viruses with unusual and sometimes unique shapes. These viruses have been studied in most detail in the thermophilic

A thermophile is an organism—a type of extremophile—that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though they can be bacteria or fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earl ...

archaea, particularly the orders Sulfolobales

In taxonomy, the Sulfolobales are an order of the Thermoprotei.

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

...

and Thermoproteales

In taxonomy, the Thermoproteales are an order of the Thermoprotei

The Thermoprotei is a class of the Thermoproteota.

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) and ...

. Defences against these viruses involve RNA interference from repetitive DNA

Repeated sequences (also known as repetitive elements, repeating units or repeats) are short or long patterns of nucleic acids (DNA or RNA) that occur in multiple copies throughout the genome. In many organisms, a significant fraction of the genom ...

sequences within archaean genomes that are related to the genes of the viruses. Most archaea have CRISPR–Cas systems as an adaptive defence against viruses. These enable archaea to retain sections of viral DNA, which are then used to target and eliminate subsequent infections by the virus using a process similar to RNA interference.

Fungal viruses

Mycovirus

Mycoviruses (Ancient Greek: μύκης ' ("fungus") + Latin '), also known as mycophages, are viruses that infect fungi. The majority of mycoviruses have double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genomes and isometric particles, but approximately 30% have po ...

es, also known as mycophages, are viruses that infect fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

. The infection of fungal cells is different from that of animal cells. Fungi have a rigid cell wall made of chitin, so most viruses can get inside these cells only after trauma to the cell wall.

*

Eukaryote viruses

Marine protists

By 2015, about 40 viruses affectingmarine protists

Marine protists are defined by their habitat as protists that live in Marine habitat, marine environments, that is, in the saline water, saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal Estuary, estuaries. Life originated as marine ...

had been isolated and examined, most of them viruses of microalgae. The genomes of these marine protist viruses are highly diverse. Marine algae

Marine primary production is the chemical synthesis in the ocean of organic compounds from atmospheric or dissolved carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it al ...

can be infected by viruses in the family Phycodnaviridae

''Phycodnaviridae'' is a family of large (100–560 kb) double-stranded DNA viruses that infect marine or freshwater eukaryotic algae. Viruses within this family have a similar morphology, with an icosahedral capsid (polyhedron with 20 fac ...

. These are large (100–560 kb) double-stranded DNA viruses

A DNA virus is a virus that has a genome made of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that is replicated by a DNA polymerase. They can be divided between those that have two strands of DNA in their genome, called double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, and ...

with icosahedral

In geometry, an icosahedron ( or ) is a polyhedron with 20 faces. The name comes and . The plural can be either "icosahedra" () or "icosahedrons".

There are infinitely many non- similar shapes of icosahedra, some of them being more symmetrica ...

shaped capsids. By 2014, 33 species divided into six genera had been identified within the family, which belongs to a super-group of large viruses known as nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses

''Nucleocytoviricota'' is a phylum of viruses. Members of the phylum are also known as the nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses (NCLDV), which serves as the basis of the name of the phylum with the suffix - for virus phylum. These viruses are refe ...

. Evidence was published in 2014 suggesting some strains of ''Phycodnaviridae'' might infect humans rather than just algal species, as was previously believed. Most genera under this family enter the host cell by cell receptor endocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a vesicle containing the ingested material. E ...

and replicate in the nucleus.

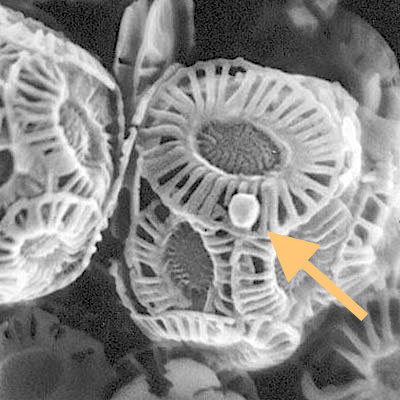

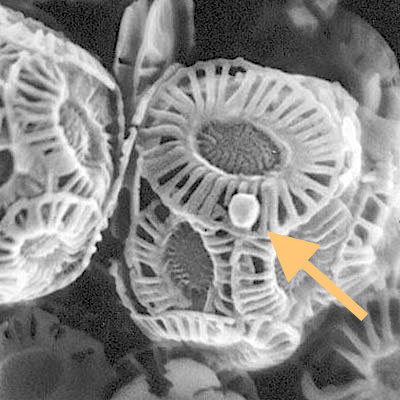

''Phycodnaviridae'' play important ecological roles by regulating the growth and productivity of their algal hosts. Algal species such ''

''Phycodnaviridae'' play important ecological roles by regulating the growth and productivity of their algal hosts. Algal species such ''Heterosigma akashiwo

''Heterosigma akashiwo'' is a species of microscopic algae of the class Raphidophyceae. It is a swimming marine alga that episodically forms toxic surface aggregations known as harmful algal bloom. The species name ''akashiwo'' is from the Japa ...

'' and the genus ''Chrysochromulina

''Chrysochromulina'' is a genus of haptophytes. This phytoplankton is distributed globally in brackish and marine waters across approximately 60 known species. All ''Chrysochromulina'' species are phototrophic, however some have been shown to b ...

'' can form dense blooms which can be damaging to fisheries, resulting in losses in the aquaculture industry. ''Heterosigma akashiwo virus'' (HaV) has been suggested for use as a microbial agent to prevent the recurrence of toxic red tides produced by this algal species. The coccolithovirus

''Coccolithovirus'' is a genus of giant double-stranded DNA virus, in the family ''Phycodnaviridae''. Algae, specifically ''Emiliania huxleyi'', a species of coccolithophore, serve as natural hosts. There is only one described species in this ge ...

''Emiliania huxleyi virus 86'', a giant double-stranded DNA virus

A DNA virus is a virus that has a genome made of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that is replicated by a DNA polymerase. They can be divided between those that have two strands of DNA in their genome, called double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, and ...

, infects the ubiquitous coccolithophore

Coccolithophores, or coccolithophorids, are single celled organisms which are part of the phytoplankton, the autotrophic (self-feeding) component of the plankton community. They form a group of about 200 species, and belong either to the kingdo ...

''Emiliania huxleyi

''Emiliania huxleyi'' is a species of coccolithophore found in almost all ocean ecosystems from the equator to sub-polar regions, and from nutrient rich upwelling zones to nutrient poor oligotrophic waters. It is one of thousands of different ...

''. This virus has one of the largest known genomes among marine viruses. ''Phycodnaviridae'' cause death and lysis of freshwater and marine algal species, liberating organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus into the water, providing nutrients for the microbial loop.

The virus-to-prokaryote ratio, VPR, is often used as an indicator of the relationship between viruses and hosts. Studies have used VPR to indirectly infer virus impact on marine microbial productivity, mortality, and biogeochemical cycling. However, in making these approximations, scientists assume a VPR of 10:1, the median observed VPR in the surface ocean. The actual VPR varies greatly depending on location, so VPR may not be the accurate proxy for viral activity or abundance as it has been treated.

Marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are the invertebrates that live in marine habitats. Invertebrate is a blanket term that includes all animals apart from the vertebrate members of the chordate phylum. Invertebrates lack a vertebral column, and some have evo ...

are susceptible to viral diseases. Sea star wasting disease

Sea star wasting disease or starfish wasting syndrome is a disease of starfish and several other echinoderms that appears sporadically, causing mass mortality of those affected. There are approximately 40 species of sea stars that have been affe ...

is a disease of starfish

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish ...

and several other echinoderms that appears sporadically, causing mass mortality of those affected. There are around 40 different species of sea stars that have been affected by this disease. In 2014 it was suggested that the disease is associated with a single-stranded DNA virus now known as the sea star-associated densovirus

Sea star-associated densovirus (SSaDV) belongs to the ''Parvoviridae'' family. Like the other members of its family, it is a single-stranded DNA virus. SSaDV has been suggested to be an etiological agent of sea star wasting disease, but conclusiv ...

(SSaDV); however, sea star wasting disease is not fully understood.

Marine vertebrates

Fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

are particularly prone to infections with rhabdovirus

''Rhabdoviridae'' is a family of negative-strand RNA viruses in the order ''Mononegavirales''. Vertebrates (including mammals and humans), invertebrates, plants, fungi and protozoans serve as natural hosts. Diseases associated with member virus ...

es, which are distinct from, but related to rabies virus. At least nine types of rhabdovirus cause economically important diseases in species including salmon, pike, perch, sea bass, carp and cod. The symptoms include anaemia, bleeding, lethargy and a mortality rate that is affected by the temperature of the water. In hatcheries the diseases are often controlled by increasing the temperature to 15–18 °C. Like all vertebrates, fish suffer from herpes viruses. These ancient viruses have co-evolved with their hosts and are highly species-specific. In fish, they cause cancerous tumours and non-cancerous growths called hyperplasia

Hyperplasia (from ancient Greek ὑπέρ ''huper'' 'over' + πλάσις ''plasis'' 'formation'), or hypergenesis, is an enlargement of an organ or tissue caused by an increase in the amount of organic tissue that results from cell proliferati ...

.

In 1984, infectious salmon anemia

Infectious salmon anemia (ISA) is a viral disease of Atlantic salmon (''Salmo salar'') caused by ''Salmon isavirus''. It affects fish farms in Canada, Norway, Scotland and Chile, causing severe losses to infected farms. ISA has been a World O ...

(ISAv) was discovered in Norway in an Atlantic salmon

The Atlantic salmon (''Salmo salar'') is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Salmonidae. It is the third largest of the Salmonidae, behind Siberian taimen and Pacific Chinook salmon, growing up to a meter in length. Atlantic salmon are ...

hatchery. Eighty percent of the fish in the outbreak died. ISAv, a viral disease, is now a major threat to the viability of Atlantic salmon farming. As the name implies, it causes severe anemia

Anemia or anaemia (British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, or a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin. When anemia comes on slowly, th ...

of infected fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

. Unlike mammals, the red blood cells of fish have DNA and can become infected with viruses. Management strategies include developing a vaccine and improving genetic resistance to the disease.

Marine mammal

Marine mammals are aquatic mammals that rely on the ocean and other marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as seals, whales, manatees, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reli ...

s are also susceptible to marine viral infections. In 1988 and 2002, thousands of harbour seals

The harbor (or harbour) seal (''Phoca vitulina''), also known as the common seal, is a true seal found along temperate and Arctic marine coastlines of the Northern Hemisphere. The most widely distributed species of pinniped (walruses, eared sea ...

were killed in Europe by phocine distemper virus

''Phocine morbillivirus'', formerly ''phocine distemper virus'' (PDV), is a paramyxovirus of the genus ''Morbillivirus'' that is pathogenic for pinniped species, particularly seals. Clinical signs include laboured breathing, fever and nervous ...

. Many other viruses, including calicivirus

The ''Caliciviridae'' are a family of "small round structured" viruses, members of Class IV of the Baltimore scheme. Caliciviridae bear resemblance to enlarged picornavirus and was formerly a separate genus within the picornaviridae. They are p ...

es, herpesvirus

''Herpesviridae'' is a large family of DNA viruses that cause infections and certain diseases in animals, including humans. The members of this family are also known as herpesviruses. The family name is derived from the Greek word ''ἕρπειν ...

es, adenovirus

Adenoviruses (members of the family ''Adenoviridae'') are medium-sized (90–100 nm), nonenveloped (without an outer lipid bilayer) viruses with an icosahedral nucleocapsid containing a double-stranded DNA genome. Their name derives from the ...

es and parvovirus

Parvoviruses are a family of animal viruses that constitute the family ''Parvoviridae''. They have linear, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genomes that typically contain two genes encoding for a replication initiator protein, called NS1, and the pr ...

es, circulate in marine mammal populations.

Giant marine viruses

Most viruses range in length from about 20 to 300 nanometers. This can be contrasted with the length of bacteria, which starts at about 400 nanometers. There are alsogiant virus

A giant virus, sometimes referred to as a girus, is a very large virus, some of which are larger than typical bacteria. All known giant viruses belong to the phylum ''Nucleocytoviricota''.

Description

While the exact criteria as defined in the s ...

es, often called ''giruses'', typically about 1000 nanometers (one micron) in length.

All giant viruses belong to the phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

''Nucleocytoviricota

''Nucleocytoviricota'' is a phylum of viruses. Members of the phylum are also known as the nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses (NCLDV), which serves as the basis of the name of the phylum with the suffix - for virus phylum. These viruses are refe ...

'' (NCLDV), together with poxviruses

''Poxviridae'' is a family of double-stranded DNA viruses. Vertebrates and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are currently 83 species in this family, divided among 22 genera, which are divided into two subfamilies. Diseases associated wit ...

.

The largest known of these is ''Tupanvirus

Tupanvirus is a genus of viruses first described in 2018. The genus is composed of two species of virus that are in the giant virus group. Researchers discovered the first isolate in 2012 from deep water sediment samples taken at 3000m depth of ...

''. This genus of giant virus was discovered in 2018 in the deep ocean as well as a soda lake, and can reach up to 2.3 microns in total length.

CroV

''Cafeteria roenbergensis virus'' (CroV) is a giant virus that infects the marine bicosoecid flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', a member of the microzooplankton community.

History

The virus was isolated from seawater samples collected from ...

giant virus scale bar=0.2 µm

domain

Domain may refer to:

Mathematics

*Domain of a function, the set of input values for which the (total) function is defined

**Domain of definition of a partial function

**Natural domain of a partial function

**Domain of holomorphy of a function

* Do ...

of life, but this has been largely discounted.

Virophages

Virophage

Virophages are small, double-stranded DNA viral phages that require the Coinfection, co-infection of another virus. The co-infecting viruses are typically giant viruses. Virophages rely on the viral replication factory of the co-infecting giant ...

s are small, double-stranded DNA viruses that rely on the co-infection

Coinfection is the simultaneous infection of a host by multiple pathogen species. In virology, coinfection includes simultaneous infection of a single cell by two or more virus particles. An example is the coinfection of liver cells with hepatiti ...

of giant virus

A giant virus, sometimes referred to as a girus, is a very large virus, some of which are larger than typical bacteria. All known giant viruses belong to the phylum ''Nucleocytoviricota''.

Description

While the exact criteria as defined in the s ...

es. Virophages rely on the viral replication factory of the co-infecting giant virus for their own replication. One of the characteristics of virophages is that they have a parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has c ...

relationship with the co-infecting virus. Their dependence upon the giant virus for replication often results in the deactivation of the giant viruses. The virophage may improve the recovery and survival of the host organism. Unlike other satellite viruses

A satellite is a subviral agent that depends on the coinfection of a host cell with a helper virus for its replication. Satellites can be divided into two major classes: satellite viruses and satellite nucleic acids. Satellite viruses, which ar ...

, virophages have a parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has c ...

effect on their co-infecting virus. Virophages have been observed to render a giant virus inactive and thereby improve the condition of the host organism.

All known virophages are grouped into the family ''Lavidaviridae

Virophages are small, double-stranded DNA viral phages that require the co-infection of another virus. The co-infecting viruses are typically giant viruses. Virophages rely on the viral replication factory of the co-infecting giant virus for th ...

'' (from "large virus dependent or associated" + -viridae). The first virophage was discovered in a cooling tower

A cooling tower is a device that rejects waste heat to the atmosphere through the cooling of a coolant stream, usually a water stream to a lower temperature. Cooling towers may either use the evaporation of water to remove process heat and ...

in Paris, France in 2008. It was discovered with its co-infecting giant virus, ''Acanthamoeba castellanii'' mamavirus

Mamavirus is a large and complex virus in the Group I family ''Mimiviridae''. The virus is exceptionally large, and larger than many bacteria. Mamavirus and other mimiviridae belong to nucleocytoplasmic large DNA virus (NCLDVs) family. Mamavirus ...

(ACMV). The virophage was named Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

and its replication relied entirely on the co-infection of ACMV and its cytoplasmic replication machinery. Sputnik was also discovered to have an inhibitory effect on ACMV and improved the survival of the host. Other characterised virophages include Sputnik 2, Sputnik 3, Zamilon and ''Mavirus

''Mavirus'' is a genus of double stranded DNA virus that can infect the marine phagotrophic flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', but only in the presence of the giant ''CroV'' virus (''Cafeteria roenbergensis''). The genus contains only one s ...

''.

Most of these virophages were discovered by analyzing metagenomic

Metagenomics is the study of genetic material recovered directly from environmental or clinical samples by a method called sequencing. The broad field may also be referred to as environmental genomics, ecogenomics, community genomics or microb ...

data sets. In metagenomic analysis, DNA sequences are run through multiple bioinformatic algorithms which pull out certain important patterns and characteristics. In these data sets are giant viruses and virophages. They are separated by looking for sequences around 17 to 20 kbp long which have similarities to already sequenced virophages. These virophages can have linear or circular double-stranded DNA genomes. Virophages in culture have icosahedral capsid particles that measure around 40 to 80 nanometers long. Virophage particles are so small that electron microscopy must be used to view these particles. Metagenomic sequence-based analyses have been used to predict around 57 complete and partial virophage genomes and in December 2019 to identify 328 high-quality (complete or near-complete) genomes from diverse habitats including the human gut, plant rhizosphere, and terrestrial subsurface, from 27 distinct taxonomic clades.

A giant marine virus CroV

''Cafeteria roenbergensis virus'' (CroV) is a giant virus that infects the marine bicosoecid flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', a member of the microzooplankton community.

History

The virus was isolated from seawater samples collected from ...

infects and causes the death by lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

of the marine zooflagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis

''Cafeteria roenbergensis'' is a small bacterivorous marine flagellate. It was discovered by Danish marine ecologist Tom Fenchel and named by him and taxonomist David J. Patterson in 1988. It is in one of three genera of bicosoecids, and the fi ...

''. This impacts coastal ecology because ''Cafeteria roenbergensis

''Cafeteria roenbergensis'' is a small bacterivorous marine flagellate. It was discovered by Danish marine ecologist Tom Fenchel and named by him and taxonomist David J. Patterson in 1988. It is in one of three genera of bicosoecids, and the fi ...

'' feeds on bacteria found in the water. When there are low numbers of ''Cafeteria roenbergensis

''Cafeteria roenbergensis'' is a small bacterivorous marine flagellate. It was discovered by Danish marine ecologist Tom Fenchel and named by him and taxonomist David J. Patterson in 1988. It is in one of three genera of bicosoecids, and the fi ...

'' due to extensive CroV infections, the bacterial populations rise exponentially. The impact of CroV

''Cafeteria roenbergensis virus'' (CroV) is a giant virus that infects the marine bicosoecid flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', a member of the microzooplankton community.

History

The virus was isolated from seawater samples collected from ...

on natural populations of ''C. roenbergensis'' remains unknown; however, the virus has been found to be very host specific, and does not infect other closely related organisms. Cafeteria roenbergensis is also infected by a second virus, the Mavirus virophage

''Mavirus'' is a genus of double stranded DNA virus that can infect the marine phagotrophic flagellate ''Cafeteria roenbergensis'', but only in the presence of the giant ''CroV'' virus (''Cafeteria roenbergensis''). The genus contains only one ...

, during co-infection with CroV. This virus interferes with the replication of CroV, which leads to the survival of ''C. roenbergensis'' cells. ''Mavirus'' is able to integrate into the genome of cells of ''C. roenbergensis'' and thereby confer immunity to the population.

Role of marine viruses

Although marine viruses have only recently been studied extensively, they are already known to hold critical roles in many ecosystem functions and cycles. Marine viruses offer a number of importantecosystem services

Ecosystem services are the many and varied benefits to humans provided by the natural environment and healthy ecosystems. Such ecosystems include, for example, agroecosystems, forest ecosystem, grassland ecosystems, and aquatic ecosystems. Th ...

and are essential to the regulation of marine ecosystems. Marine bacteriophages and other viruses appear to influence biogeochemical cycles

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and the ...

globally, provide and regulate microbial biodiversity, cycle carbon through marine food webs

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Another name for food web is consumer-resource system. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one ...

, and are essential in preventing bacterial population explosions.

Viral shunt

The dominant hosts for viruses in the ocean are marine microorganisms, such as bacteria. Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals, and are essential to the regulation of marine and freshwater ecosystems are important mortality agents of

The dominant hosts for viruses in the ocean are marine microorganisms, such as bacteria. Bacteriophages are harmless to plants and animals, and are essential to the regulation of marine and freshwater ecosystems are important mortality agents of phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

Ph ...

, the base of the foodchain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), detr ...

in aquatic environments. They infect and destroy bacteria in aquatic microbial communities, and are one of the most important mechanisms of recycling carbon and nutrient cycling in marine environments. The organic molecules released from the dead bacterial cells stimulate fresh bacterial and algal growth, in a process known as the viral shunt

The viral shunt is a mechanism that prevents marine microbial particulate organic matter (POM) from migrating up trophic levels by recycling them into dissolved organic matter (DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms. The DOM rec ...

.

In this way, marine viruses are thought to play an important role in nutrient cycles by increasing the efficiency of the biological pump

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sediments.Sigman DM & GH ...

. Viruses cause lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

of living cells, that is, they break the cell membranes down. This releases compounds such as amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

and nucleic acids

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main clas ...

, which tend to be recycled near the surface.

Viral activity also enhances the ability of the biological pump to sequester carbon in the deep ocean. Lysis releases more indigestible carbon-rich material like that found in cell walls, which is likely exported to deeper waters. Thus, the material that is exported to deeper waters by the viral shunt is probably more carbon rich than the material from which it was derived. By increasing the amount of respiration in the oceans, viruses are indirectly responsible for reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by about three gigatonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton (United States c ...

s of carbon per year. Lysis of bacteria by viruses has been shown to also enhance nitrogen cycling and stimulate phytoplankton growth.

The viral shunt

The viral shunt is a mechanism that prevents marine microbial particulate organic matter (POM) from migrating up trophic levels by recycling them into dissolved organic matter (DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms. The DOM rec ...

pathway is a mechanism that prevents (prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a Unicellular organism, single-celled organism that lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:πρό#Ancient Greek, πρό (, 'before') a ...

and eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

) marine microbial particulate organic matter

Particulate organic matter (POM) is a fraction of total organic matter operationally defined as that which does not pass through a filter pore size that typically ranges in size from 0.053 to 2 millimeters.

Particulate organic carbon (POC) is ...

(POM) from migrating up trophic level

The trophic level of an organism is the position it occupies in a food web. A food chain is a succession of organisms that eat other organisms and may, in turn, be eaten themselves. The trophic level of an organism is the number of steps it i ...

s by recycling them into dissolved organic matter

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is the fraction of organic carbon operationally defined as that which can pass through a filter with a pore size typically between 0.22 and 0.7 micrometers. The fraction remaining on the filter is called particu ...

(DOM), which can be readily taken up by microorganisms. Viral shunting helps maintain diversity within the microbial ecosystem by preventing a single species of marine microbe from dominating the micro-environment. The DOM recycled by the viral shunt pathway is comparable to the amount generated by the other main sources of marine DOM.

Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments. On average there are about ten million of them in one milliliter of seawater. Most of these viruses are

Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in marine environments. On average there are about ten million of them in one milliliter of seawater. Most of these viruses are bacteriophages

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacterio ...

infecting heterotrophic bacteria and cyanophages

Cyanophages are viruses that infect cyanobacteria, also known as Cyanophyta or blue-green algae. Cyanobacteria are a phylum of bacteria that obtain their energy through the process of photosynthesis. Although cyanobacteria metabolize photoautotrop ...

infecting cyanobacteria. Viruses easily infect microorganisms in the microbial loop due to their relative abundance compared to microbes. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic mortality contribute to carbon nutrient recycling through cell lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

. There is evidence as well of nitrogen (specifically ammonium) regeneration. This nutrient recycling helps stimulates microbial growth. As much as 25% of the primary production from phytoplankton in the global oceans may be recycled within the microbial loop through viral shunting.

Limiting algal blooms

Microorganisms make up about 70% of the marine biomass. It is estimated viruses kill 20% of the microorganism biomass each day and that there are 15 times as many viruses in the oceans as there are bacteria and archaea. Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmfulalgal bloom

An algal bloom or algae bloom is a rapid increase or accumulation in the population of algae in freshwater or marine water systems. It is often recognized by the discoloration in the water from the algae's pigments. The term ''algae'' encompas ...

s, which often kill other marine life. Scientists are exploring the potential of marine cyanophage

Cyanophages are viruses that infect cyanobacteria, also known as Cyanophyta or blue-green algae. Cyanobacteria are a phylum of bacteria that obtain their energy through the process of photosynthesis. Although cyanobacteria metabolize photoautotrop ...

s to be used to prevent or reverse eutrophication

Eutrophication is the process by which an entire body of water, or parts of it, becomes progressively enriched with minerals and nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. It has also been defined as "nutrient-induced increase in phytopla ...

. The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms.

Gene transfer

Marine bacteriophages often containauxiliary metabolic genes Auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) are found in many bacteriophages but originated in bacterial cells. AMGs modulate host cell metabolism during infection so that the phage can replicate more efficiently. For instance, bacteriophages that infect the ...

, host-derived genes thought to sustain viral replication by supplementing host metabolism during viral infection. These genes can impact multiple biogeochemical cycles, including carbon, phosphorus, sulfur, and nitrogen.

Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

and drives evolution. It is thought viruses played a central role in early evolution, before bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes diversified, at the time of the last universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; t ...

of life on Earth. Viruses are still one of the largest reservoirs of unexplored genetic diversity on Earth.

Marine habitats

Along the coast

Marine coastal habitats sit at the interface between the land and the ocean. It is likely thatRNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA ( ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruses ...

es play significant roles in these environments.

At the ocean surface

Marine surface habitats sit at the interface between the atmosphere and the ocean. The biofilm-like habitat at the surface of the ocean harbours surface-dwelling microorganisms, commonly referred to as

Marine surface habitats sit at the interface between the atmosphere and the ocean. The biofilm-like habitat at the surface of the ocean harbours surface-dwelling microorganisms, commonly referred to as neuston

Neuston, also known as pleuston, are organisms that live at the surface of the ocean or an estuary, or at the surface of a lake, river or pond. Neuston can live on top of the water surface or may be attached to the underside of the water surface. ...

. Viruses in the microlayer, the so-called virioneuston

The sea surface microlayer (SML) is the boundary interface between the atmosphere and ocean, covering about 70% of Earth's surface. With an operationally defined thickness between 1 and , the SML has physicochemical and biological properties that ...

, have recently become of interest to researchers as enigmatic biological entities in the boundary surface layers with potentially important ecological impacts. Given this vast air–water interface sits at the intersection of major air–water exchange processes spanning more than 70% of the global surface area, it is likely to have profound implications for marine biogeochemical cycles

Marine biogeochemical cycles are biogeochemical cycles that occur within marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. These biogeochemical cycles are the pathways chemical substan ...

, on the microbial loop

The microbial loop describes a trophic pathway where, in aquatic systems, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is returned to higher trophic levels via its incorporation into bacterial biomass, and then coupled with the classic food chain formed by phy ...

and gas exchange, as well as the marine food web

Compared to terrestrial environments, marine environments have biomass pyramids which are inverted at the base. In particular, the biomass of consumers (copepods, krill, shrimp, forage fish) is larger than the biomass of primary producers. This ...

structure, the global dispersal of airborne viruses originating from the sea surface microlayer

The sea surface microlayer (SML) is the boundary interface between the atmosphere and ocean, covering about 70% of Earth's surface. With an operationally defined thickness between 1 and , the SML has physicochemical and biological properties that ...

, and human health.

In the water column

Marine viral activity presents a potential explanation of theparadox of the plankton

In aquatic biology, the paradox of the plankton describes the situation in which a limited range of resources supports an unexpectedly wide range of plankton species, apparently flouting the competitive exclusion principle which holds that whe ...

proposed by George Hutchinson in 1961. The paradox of the plankton is that many plankton species have been identified in small regions in the ocean where limited resources should create competitive exclusion

In ecology, the competitive exclusion principle, sometimes referred to as Gause's law, is a proposition that two species which compete for the same limited resource cannot coexist at constant population values. When one species has even the sligh ...

, limiting the number of coexisting species. Marine viruses could play a role in this effect, as viral infection increases as potential contact with hosts increases. Viruses could therefore control the populations of plankton species that grow too abundant, allowing a wide diversity of species to coexist.

In sediments

Marine bacteriophages play an important role indeep sea

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of 200 metres (656 feet) or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes. Conditions within the deep sea are a combin ...

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

s. There are between 5x1012 and 1x1013 phages per square metre in deep sea sediments and their abundance closely correlates with the number of prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s found in the sediments. They are responsible for the death of 80% of the prokaryotes found in the sediments, and almost all of these deaths are caused by cell lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

(bursting). This allows nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus from the living cells to be converted into dissolved organic matter and detritus, contributing to the high rate of nutrient turnover in deep sea sediments. Because of the importance of deep sea sediments in biogeochemical cycles, marine bacteriophages influence the carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

and phosphorus cycles. More research needs to be done to more precisely elucidate these influences.

In hydrothermal vents

Virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es are part of the hydrothermal vent microbial community and their influence on the microbial ecology in these ecosystems is a burgeoning field of research. Viruses are the most abundant life in the ocean, harboring the greatest reservoir of genetic diversity. As their infections are often fatal, they constitute a significant source of mortality and thus have widespread influence on biological oceanographic processes, evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

and biogeochemical cycling

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and the ...

within the ocean. Evidence has been found however to indicate that viruses found in vent habitats have adopted a more mutualistic than parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has c ...

evolutionary strategy in order to survive the extreme and volatile environment they exist in. Deep-sea hydrothermal vents were found to have high numbers of viruses indicating high viral production. Like in other marine environments, deep-sea hydrothermal viruses affect abundance and diversity of prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s and therefore impact microbial biogeochemical cycling by lysing

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

their hosts to replicate. However, in contrast to their role as a source of mortality and population control, viruses have also been postulated to enhance survival of prokaryotes in extreme environments, acting as reservoirs of genetic information. The interactions of the virosphere with microorganisms under environmental stresses is therefore thought to aide microorganism survival through dispersal of host genes through horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

.

Polar regions

In addition to varied topographies and in spite of an extremely cold climate, the polar aquatic regions are teeming withmicrobial life

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

. Even in sub-glacial regions, cellular life has adapted to these extreme environments where perhaps there are traces of early microbes on Earth. As grazing by macrofauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zool ...

is limited in most of these polar regions, viruses are being recognised for their role as important agents of mortality, thereby influencing the biogeochemical cycling

A biogeochemical cycle (or more generally a cycle of matter) is the pathway by which a chemical substance cycles (is turned over or moves through) the biotic and the abiotic compartments of Earth. The biotic compartment is the biosphere and the ...

of nutrients