The ship ''Brooklyn'' Saints were

pioneers who sailed from

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

in

Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

(February 4 – July 31, 1846) to establish the first

Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

colony in the West. Due to religious persecution, leaders of

the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Christianity, Christian church that considers itself to be the Restorationism, restoration of the ...

(LDS Church) planned to relocate the Mormon populace outside the United States. Two hundred thirty eight pioneers were recruited

to sail around

Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

with heavy equipment for a large colony. They would plant crops and build infrastructure to receive the larger migration coming west by wagon the following year. ''Brooklyn'' took six months to sail 24,000 miles around Cape Horn to

Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

, surviving two terrible storms. Upon landing, the ''Brooklyn'' Saints were instrumental in building

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

[Bancroft, Hubert H. ''History of California'', Volume 5. San Francisco: The History Company, 1886, p. 551.] and helped to kick off the

California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

.

The ''Brooklyn'' arrived at the

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

shortly after the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

commenced in California, just as U.S. forces were gaining control of the area. ''Brooklyn''s seventy male passengers were immediately pressed into service. Building the settlement had to wait while assigned military duties were performed. With food and shelter scarce, the colonists experienced initial hardships. Nonetheless, within three months, many acres of land in the

San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley ( ; es, Valle de San Joaquín) is the area of the Central Valley of the U.S. state of California that lies south of the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and is drained by the San Joaquin River. It comprises seven c ...

were fenced, planted with wheat, and a grain mill was erected. When military conflict moved south, the passengers worked communally to construct one hundred buildings during the first year. Soon eight nearby towns were founded, connected by ferries, roads and bridges. As other American settlers arrived, San Francisco grew into "the great emporium of the Pacific" and farm produce yielded one of California's first millionaires, John Horner.

The ''Brooklyn'' colonists invested their time and resources into building up the Bay area, expecting the main body of Latter-day Saints to settle near them. However,

Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

chose the

Great Salt Lake Valley as the center place for the Mormon population and as the site for a holy temple to be built. When official word of the new gathering place was issued,

Samuel Brannan

Samuel Brannan (March 2, 1819 – May 5, 1889) was an American settler, businessman, journalist, and prominent Mormon who founded the '' California Star'', the first newspaper in San Francisco, California. He is considered the first to publici ...

informed the disappointed ''Brooklyn'' settlers that their communal endeavors in San Francisco were at an end. Their joint property was sold. Although uniting with the rest of the Mormon populace was still much desired, the ''Brooklyn'' settlers lacked resources to undertake an 800-mile overland journey and start their lives over.

Within three months, funding for a second migration became possible when gold was discovered at

Coloma (January 24, 1848). Samuel Brannan publicized the rich finds locally in his newspaper and sent riders with a special edition back east, spurring the Gold Rush. Operating lucrative trading posts for miners soon made Brannan another of California's early millionaires. Most of the ''Brooklyn'' pioneers worked placer mines along the

American River

, name_etymology =

, image = American River CA.jpg

, image_size = 300

, image_caption = The American River at Folsom

, map = Americanrivermap.png

, map_size = 300

, map_caption ...

and were amply rewarded. With the gold they unearthed, by July 1849, about half of the ''Brooklyn'' pioneers outfitted wagons and headed over the

Sierras to

Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

on a new route built by veterans of the Mormon Battalion. Their Mormon Emigrant Trail through Carson Pass became the main route west for gold seekers to reach the mining regions. In 1851, church leaders from Utah recruited about half of the remaining ''Brooklyn'' pioneers to build another Mormon colony at

San Bernardino

San Bernardino (; Spanish language, Spanish for Bernardino of Siena, "Saint Bernardino") is a city and county seat of San Bernardino County, California, United States. Located in the Inland Empire region of Southern California, the city had a ...

.

[Lyman, Edward Leo. ''San Bernardino: The Rise and Fall of a California Community''. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 1996, pp. 16–17.] Two ''Brooklyn'' Saints went to the

Sandwich Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

, while most of the rest returned to their lives in the eastern states.

Historical context

Motivating the Mormon exodus by land and sea

The maritime migration of the ''Brooklyn'' pioneers was part of the larger

Mormon exodus

The Mormon pioneers were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), also known as Latter Day Saints, who migrated beginning in the mid-1840s until the late-1860s across the United States from the Midwest to the S ...

from the

Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, commonly referred to as the American East, Eastern America, or simply the East, is the region of the United States to the east of the Mississippi River. In some cases the term may refer to a smaller area or the East C ...

to the

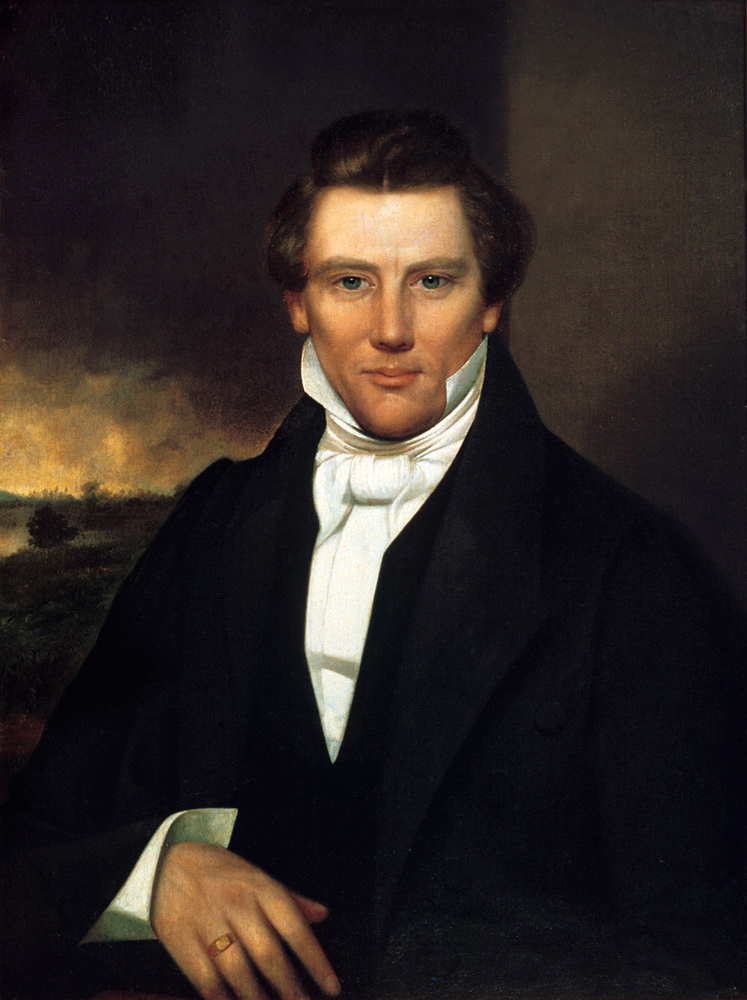

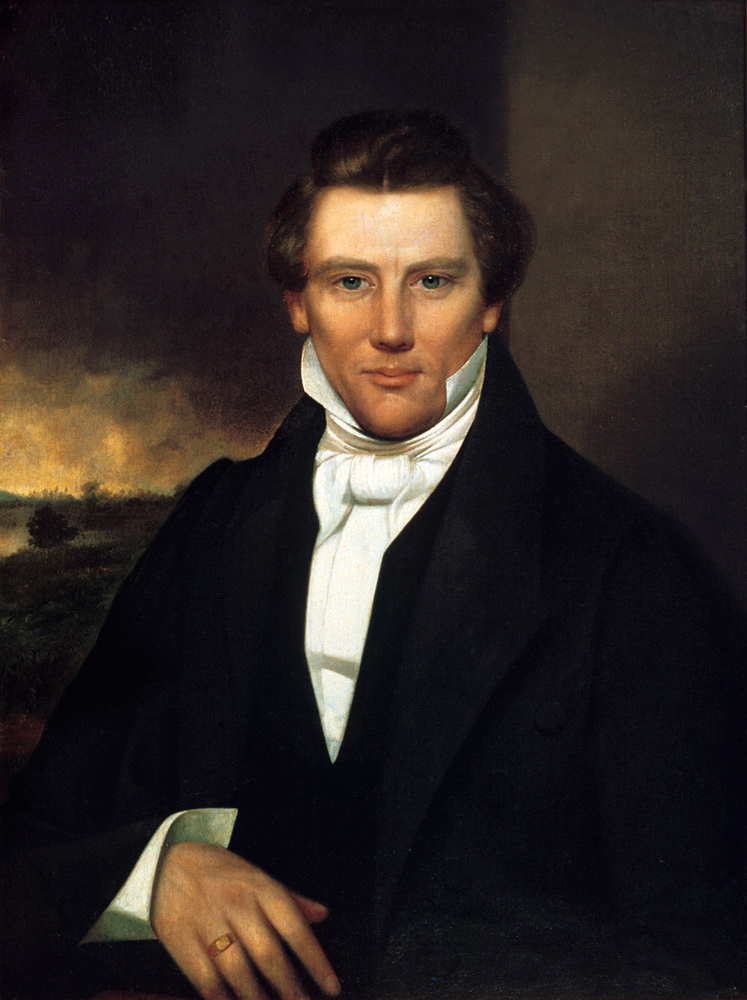

Great Salt Lake Valley. For over a decade, members of the LDS Church had been subjected to voter suppression, property destruction, looting, rape, tar and feather attacks, mob violence, massacre, and finally the

death of Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith, the founder and leader of the Latter Day Saint movement, and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, United States, on June 27, 1844, while awaiting trial in the town jail.

As mayor of the city of N ...

, the church founder. Leaders of the church repeatedly sought assistance from local, state and federal officials to deal with the abuses. Despite pleas for law enforcement, government officials rarely intervened to protect

Latter-day Saint

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

settlements, citing a difficult political situation or openly siding with anti-Mormon mobs. Efforts at self-defense made matters worse. Mormon communities moved from place to place seeking a safe environment.

Government's role

Brigham Young received a letter from Illinois Governor

Thomas Ford, dated 8 April 1845, advising him to find a new home for his people, suggesting that they establish an independent colony in

Upper California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

[Golder, Frank Alfred; Bailey, Thomas A.; and Smith, J. Lyman. ''The March of the Mormon Battalion From Council Bluffs to California.'' Undated. p. 41.] (modern Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and California), where they could live and worship as they pleased. Before doing so, President Young vainly requested asylum in

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

from its Governor Drew, who refused them. The governor suggested that they go to

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

,

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

,

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, or

Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

.

However, Young wrote, "The most of the settlers in Oregon and Texas are our old enemies, the mobocrats of Missouri... and should we attempt to march to Oregon without the government throwing a protective shield over us, Missouri's crimes would lead her first to misinterpret our intentions

nd.. to fan a flame too hot for us to encounter." A delegation sent to

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, in March, 1844, requested authorization for a "protective shield" of 100,000 armed volunteers, but such an action was deemed likely to provoke international complications with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. Illinois Congressman

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

, an ally of

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

, privately provided the Latter-day Saint delegation with a map of Oregon and a copy of

Frémont's path-finding report. Douglas urged church leaders "not to wait for government action but to strike out for Oregon, and if at the end of five years Congress would not receive

hem

A hem in sewing is a garment finishing method, where the edge of a piece of cloth is folded and sewn to prevent unravelling of the fabric and to adjust the length of the piece in garments, such as at the end of the sleeve or the bottom of the ga ...

into the Union,

hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title s ...

would have a government of

heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officiall ...

own."

Transplanting a population

In the years preceding the Mormon exodus, Joseph Smith and other church leaders made repeated attempts to engage local, state, and federal authorities in protecting them from mob attacks, in obtaining restitution for damaged or stolen property, and in supporting their

Constitutional right

A constitutional right can be a prerogative or a duty, a power or a restraint of power, recognized and established by a sovereign state or union of states. Constitutional rights may be expressly stipulated in a national constitution, or they may ...

to freedom of worship. Generally such assistance was not forthcoming. Instead, Smith was frequently charged with various forms of troublemaking or inciting unrest. Governor

Thomas Ford and President

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

stated that they were unable or unwilling to act in favor of the Latter-day Saints because of strong popular sentiment against the sect. Although national leaders were aware of the injustices done to the Latter-day Saint population, which numbered close to 200,000 at the time, other matters of economic recovery and sectionalism had their attention. After Smith's death,

church members re-grouped and determined to re-settle outside the United States. The voyage of the ship ''Brooklyn'' was part of that re-settlement effort.

Brigham Young announced on September 16, 1845, that the Latter-day Saints would abandon their headquarters city of Nauvoo, Illinois, when overland travel became possible in the spring as vegetation grew on the prairie to feed livestock. At that time, the

Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic basin, endorheic watersheds, those with no outlets, in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja California ...

was part of

Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

, a sparsely populated region, nominally under the jurisdiction of

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, but primarily occupied by

indigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

(Ute, Dine' (Navajo), Paiute, Goshute, and Shoshone). Young intended to move church members in stages and in separate wagon trains, with earlier groups establishing farms and temporary settlements along the way to feed and support the wagon companies to follow. The ship ''Brooklyn'' could carry heavy items the main migration would need in their new location, such as mill stones for grain, hundreds of farm implements, and a printing press.

Joseph Smith had spoken about moving the church beyond the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

as early as 1842. Serious efforts to identify an optimal location were made between 1842 and 1845. Since constitutionally guaranteed protections under the law were not being enforced in the U.S., the intention was to transplant the main "gathering place" for Latter-day Saints outside the country. During the October 1845

general conference, the

exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

was announced to church members at

Nauvoo, Illinois

Nauvoo ( ; from the ) is a small city in Hancock County, Illinois, United States, on the Mississippi River near Fort Madison, Iowa. The population of Nauvoo was 950 at the 2020 census. Nauvoo attracts visitors for its historic importance and its ...

. Mormons around the globe were urged to prepare for the move "to a far distant region of the west" where they would not encounter the hostility previously experienced. The following month a regional meeting was held in American Hall in New York on November 15, 1845.

Orson Pratt

Orson Pratt Sr. (September 19, 1811 – October 3, 1881) was an American mathematician and religious leader who was an original member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Christ (Latter Day Saints). He became a member of the ...

, a member of the Council of the

Twelve governing body, visited the eastern states to urge all church members to evacuate from the country. Those living in the Atlantic states were advised that it would be quicker, cheaper, and safer to sail to

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

around

Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

than to travel overland.

Samuel Brannan in leadership role

At the New York conference, Samuel Brannan was named to lead the shipload of Mormon immigrants to the West—despite an earlier difficulty with the church hierarchy that resulted in his being excommunicated for a short time. Brannan sought to be restored to church membership and to prove himself to those in leadership positions. He was allowed to serve as editor of a church newspaper under the supervision of apostle

Parley P. Pratt

Parley Parker Pratt Sr. (April 12, 1807 – May 13, 1857) was an early leader of the Latter Day Saint movement whose writings became a significant early nineteenth-century exposition of the Latter Day Saint faith. Named in 1835 as one of the first ...

. With most leaders recalled to the church headquarters to organize the cross country exodus, Brannan was called upon to lead the ''Brooklyn'' expedition. The potential for further violent incidents on shore and the desire to avoid the storm season at Cape Horn determined the departure date window. There was only a short time to make all the arrangements and recruit settlers for the voyage. Over the next three weeks, Brannan spoke in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

,

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

,

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

,

New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

,

Washington City

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

(D.C.) and

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

to raise money and register passengers. The ship ''Brooklyn'' was chartered and converted from a cargo vessel to an immigrant ship. Using church funds, William Appleby purchased tents and other items the pioneers would need. The ship ''Brooklyn'' was loaded with hundreds of agricultural tools, mechanical supplies, and large items like grist mill stones and a printing press to lay the groundwork for the new colony in the West. Brannan had the voyage organized by the end of January 1846. Historian

H. H. Bancroft described Brannan as "an erratic genius," energetic and able, shrewd in business, "famous for his acts of charity," but given to strong drink in his later years.

The plan was for the maritime company and the overland immigrants to ultimately unite. When the main body of Latter-day Saints reached their new gathering place a year later, a food supply and important resources could be provided by the pre-positioned ''Brooklyn'' pioneers. To minimize anticipated outside interference, Brigham Young did not publicly disclose the final destination. Brannan was informed, but had discretion to select a suitable location for the ''Brooklyn'' pioneers upon arrival. Prioritizing business opportunities, Brannan told the passengers they would settle on the shores of the Pacific. When the overland migration reached the Great Salt Lake Valley, Brigham Young prioritized the establishment of a unified, theocratic community in a location that would remain free from outside interference.

Politically connected consortium

While the government was unwilling to be seen helping the Mormon cause, ambitious businessmen and powerful politicians saw the Mormon plight as leverage to serve their own interests. Prior to the ''Brooklyn''s sailing, Samuel Brannan was contacted by a consortium of powerful

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

insiders.

Amos Kendall

Amos Kendall (August 16, 1789 – November 12, 1869) was an American lawyer, journalist and politician. He rose to prominence as editor-in-chief of the '' Argus of Western America'', an influential newspaper in Frankfort, the capital of the U.S. ...

and the Benson brothers demanded title to half of all lands settled by members of the church in the West. In exchange, they proposed to use their influence to restrain those who wanted to forcibly halt or disarm the

Mormon migration

The Mormon pioneers were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), also known as Latter Day Saints, who migrated beginning in the mid-1840s until the late-1860s across the United States from the Midwest to the Sa ...

. Church members could not safely remain in the U.S., but they might not be permitted to leave en masse. Crossing the national boundary into Mexico in such numbers might be interpreted as an armed invasion, especially while the annexation of Texas was such an incendiary issue. In an 1888 retrospective account of the voyage (which may have inaccuracies), Brannan claimed that when he spoke to the

Mexican Consul about their intentions, the Consul replied that the ''Brooklyn'' "would be sunk before it reached the island of

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

." Nonetheless, the voyage took place. ''Brooklyn''s sailing was delayed while Brannan waited for Brigham Young/s response to the Kendall/Benson demands – a response that never came. Urged by Captain Richardson to delay sailing no longer, the ship finally departed from New York on February 4, 1846, without incident.

International chess moves

''Brooklyn''

's voyage took place in the midst of international maneuvering to possess territory and harbors on the west coast of

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. California was highly vulnerable to takeover by different countries at the time. The arrival of large numbers of American settlers by land and by sea could serve U.S. president,

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

's strategic objectives as the United States vied with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

for control of the

Pacific coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas

Countries on the western side of the Americas have a Pacific coast as their western or southwestern border, except for Panama, where the Pac ...

.

Internal unrest and limited resources kept the

Mexican government

The Federal government of Mexico (alternately known as the Government of the Republic or ' or ') is the national government of the United Mexican States, the central government established by its constitution to share sovereignty over the republi ...

from utilizing and managing distant

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, from which it had largely withdrawn after 1834 or been forcibly expelled by 1846.

Powerful Californios in the distant territory rejected various governors sent by central Mexico to rule them. The Californios declared themselves independent unless Mexico returned to prior constitutional guarantees. However, they lacked the ability to defend the territory against even a small force on their own. Mexico offered to sell California to Great Britain, hoping to make Alta California a British protectorate against the United States, but Britain was reluctant to risk another war with the United States. An additional uncertainty was the effect John Sutter's financial challenges might have in de-stabilizing northern California. Potential international complications could arise if his finances collapsed, an outcome that was deemed highly likely given his history. If Sutter could not fulfill contractual obligations in the purchase of Fort Ross from the Russian-American Company, he could take down important Californios' fortunes with him and re-introduce Russian dominion from the coast into the Central Valley. Sutter resisted government attempts to control him and the looming risk he presented, falsely claiming that he would have the military backing of France if Californios attempted to interfere with him.

Polk had campaigned on acquiring sole jurisdiction over the

Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

, which had been jointly administered with the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

since the Treaty of 1818, and on gaining sovereignty over the

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water from a ...

. Major harbors were crucial for the increasingly valuable trade with

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and the

Sandwich Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

trans-shipment point. Polk and his predecessors actively promoted American settlement in the

Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

, overcoming British claims with the sheer number of American settlers present. The ship ''Brooklyn'' was carrying Americans to the San Francisco Bay. Having large numbers of American Mormons occupy the

San Francisco Bay area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Go ...

, could be advantageous, whether in negotiations or in armed conflict. American Consul

Thomas O. Larkin

Thomas Oliver Larkin (September 16, 1802 – October 27, 1858), known in Spanish as Don Tomás Larkin, was an American diplomat and businessman. Larkin served as the only U.S. consul to Alta California during the Mexican era and was covertly in ...

and

Lansford Hastings

Lansford Warren Hastings (1819–1870) was an American explorer and Confederate soldier. He is best remembered as the developer of Hastings Cutoff, a claimed shortcut to California across what is now the state of Utah, a factor in the Donner Part ...

communicated about the approach of thousands of American Mormons overland and their impact on the ambitions of Californios, the English, and French. Government officials, as well as private concerns, attempted to manipulate the

Mormon migration

The Mormon pioneers were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), also known as Latter Day Saints, who migrated beginning in the mid-1840s until the late-1860s across the United States from the Midwest to the Sa ...

to the West. While the Latter-day Saint population was trying to flee United States jurisdiction, the country was trying to take over the land to which they were fleeing before some other nation did.

Thousands of Latter-day Saints were migrating into Mexican territory. Some government officials questioned whether the Mormon grievances had antagonized the Saints enough that the Mormons would side with Mexico or Great Britain in the forthcoming

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

. In part to address that issue, President Polk authorized the enlistment of 500 men from migrating Mormon

wagon train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western series that aired 8 seasons: first on the NBC television network (1957–1962), and then on ABC (1962–1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and became number one in the Nielsen ratings. It ...

s on the plains into General

Stephen Watts Kearny

Stephen Watts Kearny (sometimes spelled Kearney) ( ) (August 30, 1794October 31, 1848) was one of the foremost antebellum frontier officers of the United States Army. He is remembered for his significant contributions in the Mexican–American Wa ...

's Army of the West. Enlisting the

Mormon Battalion

The Mormon Battalion was the only religious unit in United States military history in federal service, recruited solely from one religious body and having a religious title as the unit designation. The volunteers served from July 1846 to July ...

so formed was intended to assure that church members would align themselves with the United States in the upcoming conflict. On the far side of the continent, ship ''Brooklyn'' passengers would be interviewed by a naval commander at Honolulu regarding their allegiance and intentions before being allowed to sail into the San Francisco Bay. In November 1845, Polk secretly sent orders to the

Navy's Pacific Squadron to treat any incident threatening American settlers as a cause for "defensive" warfare.

Captain John C. Frémont and his Topographical Engineers were instructed to instigate such a Mexican threat to settlers. Without the knowledge of the ship ''Brooklyn'' passengers, the United States and Mexico were engaged in the Mexican–American War (April 25, 1846 – February 2, 1848) for three months before the ship arrived.

Maritime migration

Recruiting seaborn settlers

In November 1845, Parley P. Pratt, a member of the church's Council of the Twelve, wrote Samuel Brannan, saying "Our apostles, assembled in meeting, have debated the best method of getting all our people into the far west with the least possible hardship. We have read

Hasting's account of California and

Fremont's Journal of Explorations in the west, and we have concluded that the

Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic basin, endorheic watersheds, those with no outlets, in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja California ...

in the top of the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, where lies the

Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. It lies in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah and has a substantial impact upon the local climate, particula ...

, is the proper place for us." Samuel Brannan was authorized to charter a ship and organize the exodus of church members from

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and the

Atlantic coast. On the evening of November 8, 1845, Latter-day Saints from neighboring states attended a major conference to hear the Apostle Orson Pratt speak at American Hall in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Pratt explained "the necessity of all removing to the

west" by land or by sea, urging "a union of action for the benefit of the poor, that they might not be left behind."

The LDS Church had been organizing immigrant voyages for European converts for many years, and had developed an international reputation for their expertise in doing so. Samuel Brannan was assigned to organize the first shipload of Latter-day Saint immigrants to "

Zion

Zion ( he, צִיּוֹן ''Ṣīyyōn'', LXX , also variously transliterated ''Sion'', ''Tzion'', ''Tsion'', ''Tsiyyon'') is a placename in the Hebrew Bible used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Israel as a whole (see Names ...

" – the new "gathering place" for the Mormon population. In a voyage anticipated to take five or six months, families would sail from New York around Cape Horn to

Upper California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

. Recounting their numerous persecutions, Samuel Brannan urged conference attendees to resolve to leave the U.S. Fifty people promptly subscribed on behalf of themselves and their families to take the voyage. However, getting affairs in order, selling businesses and homes, paying the charter fees, and being ready to start life over in a short time was a task not all could accomplish. Sixteen families who subscribed in advance did not sail with the ''Brooklyn'' when the time came, but forty-eight additional surnames were added to the final passenger list as word spread. About 60% of those who actually sailed had not subscribed by December 13, 1845. When the departure call came, 238 people boarded the ship – about 60 more than the legal passenger limit would allow.

Expansionists and opportunists

Amos Kendall and the Benson brothers

In July, 1845, Brannan advertised in ''The Messenger'' that his establishment would serve as an emigrating office for Mormons in the East who wished to travel to the West. That summer in

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Brannan met with western expansionist,

Amos Kendall

Amos Kendall (August 16, 1789 – November 12, 1869) was an American lawyer, journalist and politician. He rose to prominence as editor-in-chief of the '' Argus of Western America'', an influential newspaper in Frankfort, the capital of the U.S. ...

, one of the most powerful men in

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

; with author

Thomas Jefferson Farnham; and with A. W. Benson and A. G. Benson, naval contractors and commercial traders. They claimed to represent a larger group of powerful interests in

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, including

President Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

as a "silent partner." Samuel Brannan wrote to

Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

about the proposition, claiming to have "learned that the secretary of war and other members of the cabinet were laying plans and were determined to prevent the Mormons from moving west, alleging that it was against the law for an armed body of men to go from the United States to any other government. They say it will not do to let the

Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

go to

California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

nor

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, neither will it do to let them tarry in the states, and they must be obliterated from the face of the earth." Based on Brannan's letters, Young's diary for January 29, 1846, stated "that the Government intended to intercept our movements – by placing strong forces in the way to take from us all fire arms – on the grounds that we were going to another Nation."

However, Kendall and Benson assured Brannan that they "would undertake to prevent all interference if the Mormon leaders would sign an agreement "to transfer to A. G. Benson & Co. the odd numbers of all the lands and town lots they may acquire in the country where they may settle"". Brigham Young considered the offer a swindle and rejected it outright. However, his decision did not reach Brannan before the ''Brooklyn'' sailed. No direct evidence has yet turned up, but it is possible that Brannan was much involved in the conspiracy, "an 1840s-style

covert operation

A covert operation is a military operation intended to conceal the identity of (or allow plausible deniability by) the party that instigated the operation. Covert operations should not be confused with clandestine operations, which are performe ...

whose aim was the conquest of California."

[Bagley, Will. Loc. cit.] Brannan corresponded with the Benson brothers and had business dealings with them after the voyage. Whatever the real story was, Brannan represented to Brigham Young and to the ''Brooklyn'' passengers that the government threat was serious and that their departure was delayed, waiting for instructions from the church leadership. Meanwhile, as a ruse, Brannan spread word that the ship might be sailing for Oregon rather than California. A pennant declaring "Oregon" was flown from the ship's mast.

Conversion of the chartered vessel to serve as an immigrant ship was complete and only a few registered passengers had not yet arrived. Captain Richardson finally pressed for departure, having delayed long enough.

Western expansionists

Several western expansionists had an impact on the situation the ''Brooklyn'' settlers encountered upon arrival. President Polk instructed

Thomas O. Larkin

Thomas Oliver Larkin (September 16, 1802 – October 27, 1858), known in Spanish as Don Tomás Larkin, was an American diplomat and businessman. Larkin served as the only U.S. consul to Alta California during the Mexican era and was covertly in ...

, the American Consul in California, to encourage pro-American sentiment among the Hispanic population.

[DeVoto, Bernard. ''The Year of Decision 1846''. New York: Truman Talley Books, St. Martins Griffin, 2000 edition.] Many influential Californios, particularly in the north, were inclined toward Americans. Larkin enlisted

John Marsh John Marsh may refer to:

Politicians

* John Marsh (MP fl. 1394–1397), MP for Bath

* John Marsh (MP fl. 1414–1421), MP for Bath

*John Allmond Marsh (1894–1952), Canadian Member of Parliament

* John Otho Marsh Jr. (1926–2019), American c ...

, a wealthy landowner in the

Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, to encourage western migration among his contacts in the eastern states. Like others, Marsh entertained notions of becoming President of an independent republic of California. He engaged in a letter-writing campaign to friends and publishers back east, extolling the virtues of California and inviting settlers to join him. The Bartleson-Bidwell wagon train to California was organized in response. A number of ambitious men saw opportunity and tried to position themselves for power and influence in the West.

Thomas Jefferson Farnham, author of books on Oregon and California, visited Apostle

Orson Pratt

Orson Pratt Sr. (September 19, 1811 – October 3, 1881) was an American mathematician and religious leader who was an original member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Christ (Latter Day Saints). He became a member of the ...

multiple times to urge Mormon migration to California near him. Captain

Lansford Hastings

Lansford Warren Hastings (1819–1870) was an American explorer and Confederate soldier. He is best remembered as the developer of Hastings Cutoff, a claimed shortcut to California across what is now the state of Utah, a factor in the Donner Part ...

, leader of the 1842 emigration to

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and California, wrote a pro-California guide book from which Samuel Brannan printed pages in the

''New-York Messenger'', 1 November 1845 issue.

To initiate his strategy to take Alta California, U.S. President Polk sent secret orders in November 1845 to the Pacific Squadron and to Captain John C. Frémont via Archibald Gillespie, who carried the messages covertly across Mexico. President Polk's expansionist aspirations were shared by Missouri Senator

Thomas Hart Benton, chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs and a strong believer in America's

Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

. Benton's son-in-law was John C. Frémont, the famed "Pathfinder" who led the land-based military campaign to take over California during the Mexican–American War. Senator Benton and Frémont were opposed to Mormons, but were willing to use them in bringing about the conquest of the West. Frémont had instructions to instigate an incident that would require the intervention of the U.S. Navy to defend American settlers in Alta California. In early June, American settlers took actions that came to be known as the Bear Flag Revolt. Frémont formed a California Battalion, which they joined. On July 1, Captain Frémont led a party that disabled the Mexican presidio cannon overlooking the entrance to the San Francisco Bay. By so doing, the threat to the ''Brooklyn'' was eliminated before the ship sailed into the bay. A few of the ''Brooklyn'' passengers joined Frémont's California Battalion and fought in southern California.

Ship ''Brooklyn''

Description of the Vessel

Built by the firm of J. & M. Madigan of Newcastle, Maine, in 1834, the ''Brooklyn'' was a full rigged merchantman with a mackerel bow, 125 feet long, 28 feet across the beams, and a 445 ton cargo capacity. ''Brooklyn''s black hull contrasted with a wide, white stripe above the water line, emphasizing faux gun ports, set off by a horn of plenty figurehead beneath the bowsprit. Samuel Brannan advertised the chartered vessel in the

New York Messenger as "a first class ship, in the best of order for sea... a very fast sailor". However, the voyage occurred at a turning point in maritime capability. The first

extreme clipper

An extreme clipper was a clipper designed to sacrifice cargo capacity for speed. They had a bow lengthened above the water, a drawing out and sharpening of the forward body, and the greatest breadth further aft. In the United States, extreme clipp ...

, the

Rainbow

A rainbow is a meteorological phenomenon that is caused by reflection, refraction and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a spectrum of light appearing in the sky. It takes the form of a multicoloured circular arc. Rainbows c ...

, was launched from the

Smith and Dimon Shipyard two miles up river from ''Brooklyn''s berth at the Old Slip on the

East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Queens ...

, returning from

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

in an astonishingly short time just months before the Saints sailed. Years later, the ''Brooklyn'' was described by passenger James Skinner as a "staunch tub of a whaler",

Augusta Joyce Crocheron's retrospective account of the voyage said the ship was "old and almost worn out, ...one of the old time build... made more for work than beauty..." Clipper ships were much faster than the older packet ships and merchantmen. Rainbow's successor, the

Sea Witch

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have use ...

, made an 1850 run from New York around Cape Horn to San Francisco in 97 days. The same route took ''Brooklyn'' 5 months 27 days. By far the longest of the Latter-day Saint voyages, ''Brooklyn''s passage from New York took two months longer than passage from

Calcutta, India

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

, or

Sydney, Australia

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the States and territories of Australia, state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and List of cities in Oceania by population, Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metro ...

.

The ''Brooklyn'' was converted

from its prior role as a

cargo ship

A cargo ship or freighter is a merchant ship that carries cargo, goods, and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year, handling the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usu ...

to serve as a chartered

passenger vessel

A passenger ship is a merchant ship whose primary function is to carry passengers on the sea. The category does not include cargo vessels which have accommodations for limited numbers of passengers, such as the ubiquitous twelve-passenger freig ...

. The fare for adults was set at $75 and half price for children. On the main deck, first class cabins stood next to the captain's cabin. The ship's galley topside was expanded to serve as many as 400 passengers at a time. A small shelter was provided for two milch cows, intended to supply the needs of the children. Pens were built for chickens and forty pigs. Passenger accommodations were added on the 'tween deck where the headroom was 5'6" – even less when ducking under deck-supporting timbers. Thirty-two "staterooms" with double bunks were built along the interior walls of the hull. It was customary for passengers to supply their own ticking and blankets. A long, narrow table, with edges raised to contain sliding objects, ran most of the length of the passenger deck. Meals, meetings, and daily schooling of the children were to take place in that "Hall." Two sets of galley stairs descended from the main deck. Extra ventilation and skylights were added to augment windsail air. At night the glimmer of two whale oil lamps lit the way for passengers to move around safely on the 'tween deck. Additional sleeping quarters in the form of hammocks were set up on the orlop in the hold for single men.

Captain and crew

On this voyage, ''Brooklyn''s Master and Captain was 48 year old Abel W. Richardson, a principal owner of the ship. Brannan described him as one of the most skillful seamen sailing out of New York, a temperance man with excellent moral character. Passenger

John Horner confirmed that Captain Richardson, his mates, and sailors "in morals seemed above the average. Unbecoming language was seldom heard on board." The captain was a Baptist who held religious services each week, which the passengers and crew attended. The crew consisted of a First Mate,

["''Brooklyn'', Captain Joseph W. Richardson."](_blank)

In: Ship Passengers – Sea Captains, 1849. Maritime Heritage Project, San Francisco 1846-1899. Accessed July 7, 2020.[Bagley, Will. ''Scoundrel's Tale: The Samuel Brannan Papers''. Logan, Utah: University of Utah Press, 1999, p. 174.] Second Mate, and carpenter, a steward and cook for the officers and first class passengers, another cook and steward for the rest of the passengers, and twelve seamen. The crew averaged 26 years of age. Seamen earned $11 per month, with stewards and cooks earning a little more. The First and Second Mate earned $35 and $20 per month respectively.

Passengers

Ten lists of ''Brooklyn''s passengers have emerged with minor variations.

[Hansen, Loren K. "Voyage of the Brooklyn," ''Dialogue, A Journal of Mormon Thought'', Volume 21, No. 3, Autumn, 1988.] The general consensus is that ''Brooklyn'' sailed with 238 passengers – 60 more passengers than the legal limit of two passengers for every five tons. Among the 70 men, 68 women and 100 children, 50 children were less than six years old. Thirty were infants or toddlers age three and under. There were three recorded births and eleven deaths by journey's end.

Based on counts from Richard Bullock's biographical sketches, the ''Brooklyn''s male passengers were largely farmers, mechanics, and tradesmen from the eastern states. Most men were traveling with their families – some with collateral branches of their families or with in-laws. Five families sent one or more of their kin by ship while their other family member(s) crossed the continent by wagon train. Fourteen men traveled without other families members. Four were not members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, one of whom joined the ship on its last leg out of

Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

in order to marry a ''Brooklyn'' passenger after a whirlwind, island romance. Three of the single men traveled for business – two as first class passengers and one, Edward Kemble, as Brannan's printing apprentice. Two passengers were journalists and publishers, two wrote poetry collections, and one authored a book on national finance.

Angeline Lovett, Olive Coombs, Quartus Sparks and John Horner were teachers. Daniel Stark brought manuals and tools to teach himself how to be a surveyor during the voyage.

Of the nine single women on board, five knew one another from working at the Lowell factories before the voyage. One young single woman, Zelnora Snow, worked for the Glover family, also on board, helping to care for their children. An enterprising 38-year-old Scottish dressmaker was traveling alone. Two single women sailed with younger generations of their kin, and one traveled with her sister's family. Emmaline Lane married George Sirrine, a fellow voyager, as soon as the ship landed.

At a farewell social gathering shortly before sailing, a prominent New York attorney and literary society president named Joshua M. Van Cott presented the group with 179 volumes of the Harper Family Library. The collection covered world history; a variety of cultures from

Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

to

Numibia ,

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

to

Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

; biographies from

Mohammed

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

to

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, martyrs of science,

North American Indian

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the Ame ...

orators and statesmen; narratives by world explorers; discussions of the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and

Far Eastern

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

cultures; philosophy, morality essays, political and educational theories; natural history and science; economics, law, and literature. With little else to occupy the passengers for six months, the books were widely circulated. According to a letter written three months into the voyage, every one of the volumes had been read before reaching the

Juan Fernandez Islands

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of ''John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanish, t ...

.

Atlantic crossing

Passengers were urged to get their belongings to the dock well in advance. Families began arriving toward the end of January. The ''Brooklyn''s departure was originally scheduled for January 24, 1846, but the ship was not quite ready and some registered passengers were still on route to the port. The voyagers stayed in nearby boarding houses until the ship sailed. Trying to avoid publicity or outside interference with their departure, Brannan advised the voyagers not to refer to one another as Brother or Sister, a common Latter-day Saint form of address. John Horner and Elizabeth Imlay married on January 20 in

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, and left for the

New York harbor

New York Harbor is at the mouth of the Hudson River where it empties into New York Bay near the East River tidal estuary, and then into the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of the United States. It is one of the largest natural harbors in t ...

the next day, spending their honeymoon on the ship. On January 21, Laura Farnsworth Skinner gave birth to Laura Ann Skinner, who lived a mere eight days. Eight other women were pregnant when the voyage began.

[Bullock, Richard. ''The Ship ''Brooklyn, Vol. 1, 2009, p. 33.] Two delivered healthy babies mid-voyage and survived, but three newborns died at sea or while pausing in the

Sandwich Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

. Three more mothers delivered their babies shortly after arrival in California.

Homes and businesses had been quickly sold and property disposed. Parting from loved ones was difficult with families fearing they might never see one another again. Several passengers experienced difficulties with extended family members who objected to their kin migrating to the far side of the continent with an out-of-favor religious group. The uncle of Katherine Coombs (daughter of Abraham Coombs by his first wife) did not want to lose his favorite niece, so he concocted a false charge and got the police to arrest Abraham on the dock while he kidnapped the girl. Abraham was able to draw enough attention to his plight that other ''Brooklyn'' passengers came to his aid, foiling the dockside drama. The family was then able to board the ship. When Isaac and Ann Robbins were bidding farewell to her parents, Ann's father drove her husband off at rifle point, forcibly detaining Ann and the children so they would not go. With the help of other family members a few days later, Ann and the children managed to escape on foot across snowy

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

back roads, making their way across the state to reunite with Isaac just before ''Brooklyn'' sailed.

Prior to departure, a schedule and twenty-one rules for daily conduct were agreed upon, although they were not fully implemented for some time. Days consisted of reveille at 6 am, cleaning of staterooms, inspections, sick call, meals served in two seatings, school for the children, religious services on Sundays, with people assigned on a rotating basis to watch over belongings and food supplies, and much free time. Standards of dress and hygiene were to be observed. With 100 children on board, many of them infants and toddlers, child care was a constant occupation.

Gale

On the afternoon of February 4, 1846, the steamboat

tug

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

Sampson drew ''Brooklyn'' away from the

East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Queens ...

dock. A pennant atop the mast proclaimed the ship was headed for

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. The pilot conducted ''Brooklyn'' through the shifting Narrows to

Sandy Hook

Sandy Hook is a barrier spit in Middletown Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States.

The barrier spit, approximately in length and varying from wide, is located at the north end of the Jersey Shore. It encloses the southern en ...

, passing without interference under the "bristling guns" of

Fort Hamilton

Fort Hamilton is a United States Army installation in the southwestern corner of the New York City borough of Brooklyn, surrounded by the communities of Bay Ridge and Dyker Heights. It is one of several posts that are part of the region which is ...

. The second day out, there were heavy seas. Soon after crossing the

Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Current, North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida a ...

on February 10, the ship was forced to lay-to in a heavy gale, struggling for four days. The experienced captain feared his cabin on the upper deck would be swept away, allowing waves to pour down to the lower decks. The ship would be lost. Hatched below with poor ventilation and little light, most passengers were desperately seasick. Women and children were lashed to bunks to reduce injuries caused by the violent movements of the ship. The masts remained intact as passengers sang hymns to bolster spirits.

William Glover later wrote of the storm.

[Glover, William. ''The Mormons in California''. Forward and notes by Paul Bailey. Los Angeles: Glen Dawson, 1954.] "Some who were more resolute struggled to the deck to behold the sublime grandeur of the scene – to hear the dismal howl of the winds, and to see the ship with helm lashed, pitching, rolling, dipping in the trough of the sea and then tossed on the highest billow. These are sights once beheld are never to be forgotten."

The story is often told that the captain finally came down to address the passengers, saying, "My friends, there is a time in every man's life when it is fitting that he should prepare to die. That time has come to us, and unless God interposes, we shall all go to the bottom; I have done all in my power, but this is the worst gale I have ever known since I was a master of a ship." One passenger replied, "Captain Richardson, we were sent to California and we shall get there." Another exclaimed, "Captain, I have no more fear than though we were on solid land." The captain stared in disbelief at such remarks and was heard to say in leaving, "They are either fools and fear nothing, or they know more than I do".

[Crocheron, Augusta Joyce. "The Ship ''Brooklyn''", ''Western Galaxy'', March 1888, p. 81.]

A death per week

It took days to clean up the interior wreckage, sanitize quarters, and air out soggy bedding. Within another week, the ''Brooklyn'' had fair weather once more. Two weeks later, northeast trade winds took the ship close to the

Cape Verde Islands

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

. Soon thereafter, riding before southeast trade winds, the ship slanted down towards

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

. Although ''Brooklyn'' had survived the great storm, the voyage claimed a dozen lives. Great sadness was reported as ten passengers died in the first three months at sea, nearly one a week. Each was buried at sea in the traditional mariners' manner, slipped over the side in a weighted canvas bag following religious remarks. Some burials were conducted privately to reduce the emotional strain. Half of the deaths resulted from diseases contracted before boarding the ship. Half of those who died were infants or young children. Twice the ''Brooklyn'' was trapped in doldrums. Sailing south near the

equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

, the ship spent two or three days stuck in oppressive heat.

At some point early in the voyage, Brannan proposed the formation of "

Samuel Brannan

Samuel Brannan (March 2, 1819 – May 5, 1889) was an American settler, businessman, journalist, and prominent Mormon who founded the '' California Star'', the first newspaper in San Francisco, California. He is considered the first to publici ...

and Company" which would hold all the assets transported by the ''Brooklyn'', including personal property. Other assets included $16,000 worth of supplies, such as tools and tents, that were purchased with church funds by William Appleby. The participants would act jointly to make preparations for members of the overland emigration; would pay the final transportation debt; and would give the proceeds of their labor for the next three years to a common fund, from which all would draw their living. Any who refused to obey the covenants set down would be expelled. If all dropped out, the common fund would go to Brannan as First Elder. Contention later arose over this plan. Although seen as unfair, the passengers signed the articles of agreement.

Weeks turned into months. Although passengers had assigned daily duties to occupy them, boredom hung heavily. The children attended school daily around the long table on the 'tween deck. The entire ship's company and crew celebrated the "crossing of the line" (the

Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

) in March. It was common for passengers to compete at guessing the speed and nautical miles covered each day. Reading, board games, and child care filled many hours. When reading was not enough, one passenger resorted to lowering himself over the side of the ship on a rope to tease sharks. Daniel Stark brought surveyor's instruments and manuals, purchased before sailing. He studied mathematical principles throughout the voyage so that he could work as a surveyor when they landed.

Atlantic birth

Approaching

Drake's Passage at the southern tip of

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

, a healthy baby boy was born to Charles and Sarah Burr with the help of midwives. The baby was named John Atlantic Burr.

Cape Horn

Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

was a major milestone on the route, and a daunting prospect. The region is beset by dangerous winds and often towering waves that beat against rocky cliffs on uncharted shores. It was not uncommon for the passage from east to west to take a full month before a sailing ship broke through powerful head winds coming from the west. To everyone's astonishment and relief, the ''Brooklyn'' "rounded" the Horn in a brief interlude between storms. It was cold and dim with no sight of the sun, but the wind and waves were otherwise good.

''Brooklyn'' passed land's end "first rate," but could get no farther. Because of the dangers of a

lee shore

A lee shore, sometimes also called a leeward ( shore, or more commonly ), is a nautical term to describe a stretch of shoreline that is to the lee side of a vessel—meaning the wind is blowing towards land. Its opposite, the shore on the windward ...

with high winds, it was standard practice for sailing vessels to give the western coastline of

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

a wide girth. Two hundred miles of "westing" was required before turning north. Captain Richardson pressed forward against the strong winds from the

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, repeatedly losing way. Not able to proceed west or turn north, he decided to turn south in hopes of catching a different wind pattern. The farther south the ship sailed toward

Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

, the colder it became. Richardson's search for a countervailing wind finally paid off. ''Brooklyn'' was able to sail far enough west into the Pacific so that the ship could safely turn north.