Verna (ancient Rome) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Besides manual labour, slaves performed many domestic services and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Accountants and physicians were often slaves. Slaves of Greek origin in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those sentenced to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

Slaves were considered property under

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Besides manual labour, slaves performed many domestic services and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Accountants and physicians were often slaves. Slaves of Greek origin in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those sentenced to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

Slaves were considered property under

"Roman Slavery: The Social, Cultural, Political, and Demographic Consequences"

accessed 17 March 2021 The

During the period of Roman imperial expansion, the increase in wealth amongst the Roman elite and the substantial growth of slavery transformed the economy.Hopkins, Keith. ''Conquerors and Slaves: Sociological Studies in Roman History''. Cambridge University Press, New York. Pgs. 4–5 Although the economy was dependent on slavery, Rome was not the most slave-dependent culture in history. Among the

During the period of Roman imperial expansion, the increase in wealth amongst the Roman elite and the substantial growth of slavery transformed the economy.Hopkins, Keith. ''Conquerors and Slaves: Sociological Studies in Roman History''. Cambridge University Press, New York. Pgs. 4–5 Although the economy was dependent on slavery, Rome was not the most slave-dependent culture in history. Among the

New slaves were primarily acquired by wholesale dealers who followed the Roman armies. Many people who bought slaves wanted strong slaves, mostly men. Child slaves cost less than adults although other sources state their price as higher.

New slaves were primarily acquired by wholesale dealers who followed the Roman armies. Many people who bought slaves wanted strong slaves, mostly men. Child slaves cost less than adults although other sources state their price as higher.

Slaves worked in a wide range of occupations that can be roughly divided into five categories: household or domestic, imperial or public, urban crafts and services, agriculture, and mining.

Epitaphs record at least 55 different jobs a household slave might have,"Slavery in Rome," in ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome'' (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 323. including barber, butler, cook, hairdresser, handmaid (''ancilla''), wash their master's clothes,

Slaves worked in a wide range of occupations that can be roughly divided into five categories: household or domestic, imperial or public, urban crafts and services, agriculture, and mining.

Epitaphs record at least 55 different jobs a household slave might have,"Slavery in Rome," in ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome'' (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 323. including barber, butler, cook, hairdresser, handmaid (''ancilla''), wash their master's clothes,  Slaves numbering in the tens of thousands were condemned to work in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal. ''Damnati in metallum'' ("those condemned to the mine") were convicts who lost their freedom as citizens (''libertas''), forfeited their property (''bona'') to the state, and became ''servi poenae'', slaves as a legal penalty. Their status under the law was different from that of other slaves; they could not buy their freedom, be sold, or be set free. They were expected to live and die in the mines. Imperial slaves and freedmen (the ''familia Caesaris)'' worked in mine administration and management.

In the Late Republic, about half the

Slaves numbering in the tens of thousands were condemned to work in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal. ''Damnati in metallum'' ("those condemned to the mine") were convicts who lost their freedom as citizens (''libertas''), forfeited their property (''bona'') to the state, and became ''servi poenae'', slaves as a legal penalty. Their status under the law was different from that of other slaves; they could not buy their freedom, be sold, or be set free. They were expected to live and die in the mines. Imperial slaves and freedmen (the ''familia Caesaris)'' worked in mine administration and management.

In the Late Republic, about half the

According to

According to

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Besides manual labour, slaves performed many domestic services and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Accountants and physicians were often slaves. Slaves of Greek origin in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those sentenced to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

Slaves were considered property under

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Besides manual labour, slaves performed many domestic services and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Accountants and physicians were often slaves. Slaves of Greek origin in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those sentenced to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

Slaves were considered property under Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

and had no legal personhood. Most slaves would never be freed. Unlike Roman citizen

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

s, they could be subjected to corporal punishment, sexual exploitation

Sexual slavery and sexual exploitation is an attachment of any ownership right over one or more people with the intent of coercing or otherwise forcing them to engage in sexual activities. This includes forced labor, reducing a person to a s ...

(prostitutes

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

were often slaves), torture and summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

. Over time, however, slaves gained increased legal protection, including the right to file complaints against their masters.

One major source of slaves had been Roman military expansion during the Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

. The use of former enemy soldiers as slaves led perhaps inevitably to a series of ''en masse'' armed rebellions, the Servile Wars

The Servile Wars were a series of three slave revolts ("servile" is derived from "''servus''", Latin for "slave") in the late Roman Republic.

Wars

* First Servile War (135−132 BC) — in Sicily, led by Eunus, a former slave claiming to be a pr ...

, the last of which was led by Spartacus

Spartacus ( el, Σπάρτακος '; la, Spartacus; c. 103–71 BC) was a Thracian gladiator who, along with Crixus, Gannicus, Castus, and Oenomaus, was one of the escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a major slave uprising ...

. During the ''Pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is periodization, identified as a period and as a golden age (metaphor), golden age of increased as well as sustained Imperial cult of ancient Rome ...

'' of the early Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

(1st–2nd centuries AD), the emphasis was placed on maintaining stability, and the lack of new territorial conquests dried up this supply line of human trafficking

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others. This may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage, or the extrac ...

. To maintain an enslaved workforce, increased legal restrictions on freeing slaves were put into place. Escaped slaves would be hunted down and returned (often for a reward). There were also many cases of poor people selling their children to richer neighbours as slaves in times of hardship.

Origins

In his '' Institutiones'' (161 AD), the Roman jurist Gaius wrote that: The 1st century BC Greek historianDionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary sty ...

indicates that the Roman institution of slavery began with the legendary founder Romulus

Romulus () was the legendary foundation of Rome, founder and King of Rome, first king of Ancient Rome, Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus ...

, giving Roman fathers the right to sell their own children into slavery, and kept growing with the expansion of the Roman state

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

. Slave ownership was most widespread throughout the Roman citizenry from the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

(218–201 BC) to the 4th century AD. The Greek geographer Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

(1st century AD) records how an enormous slave trade resulted from the collapse of the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

(100–63 BC).Moya K. Mason"Roman Slavery: The Social, Cultural, Political, and Demographic Consequences"

accessed 17 March 2021 The

Twelve Tables

The Laws of the Twelve Tables was the legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. Formally promulgated in 449 BC, the Tables consolidated earlier traditions into an enduring set of laws.Crawford, M.H. 'Twelve Tables' in Simon Hornblowe ...

, Rome's oldest legal code, has brief references to slavery, indicating that the institution was of long standing. In the tripartite division of law by the jurist Ulpian

Ulpian (; la, Gnaeus Domitius Annius Ulpianus; c. 170223? 228?) was a Roman jurist born in Tyre. He was considered one of the great legal authorities of his time and was one of the five jurists upon whom decisions were to be based according to ...

(2nd century AD), slavery was an aspect of the ''ius gentium

The '' ius gentium'' or ''jus gentium'' (Latin for "law of nations") is a concept of international law within the ancient Roman legal system and Western law traditions based on or influenced by it. The ''ius gentium'' is not a body of statute law ...

'', the customary international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

held in common among all peoples (''gentes''). The "law of nations" was neither considered natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

, thought to exist in nature and govern animals as well as humans, nor civil law, belonging to the emerging bodies of laws specific to a people in Western societies.Brian Tierney, ''The Idea of Natural Rights'' (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2002, originally published 1997 by Scholars Press for Emory University), p. 136. All human beings are born free (''liberi'') under natural law, but slavery was held to be a practice common to all nations, who might then have specific civil laws pertaining to slaves. In ancient warfare, the victor had the right under the ''ius gentium'' to enslave a defeated population; however, if a settlement had been reached through diplomatic negotiations or formal surrender, the people were by custom to be spared violence and enslavement. The ''ius gentium'' was not a legal code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the cod ...

, and any force it had depended on "reasoned compliance with standards of international conduct".

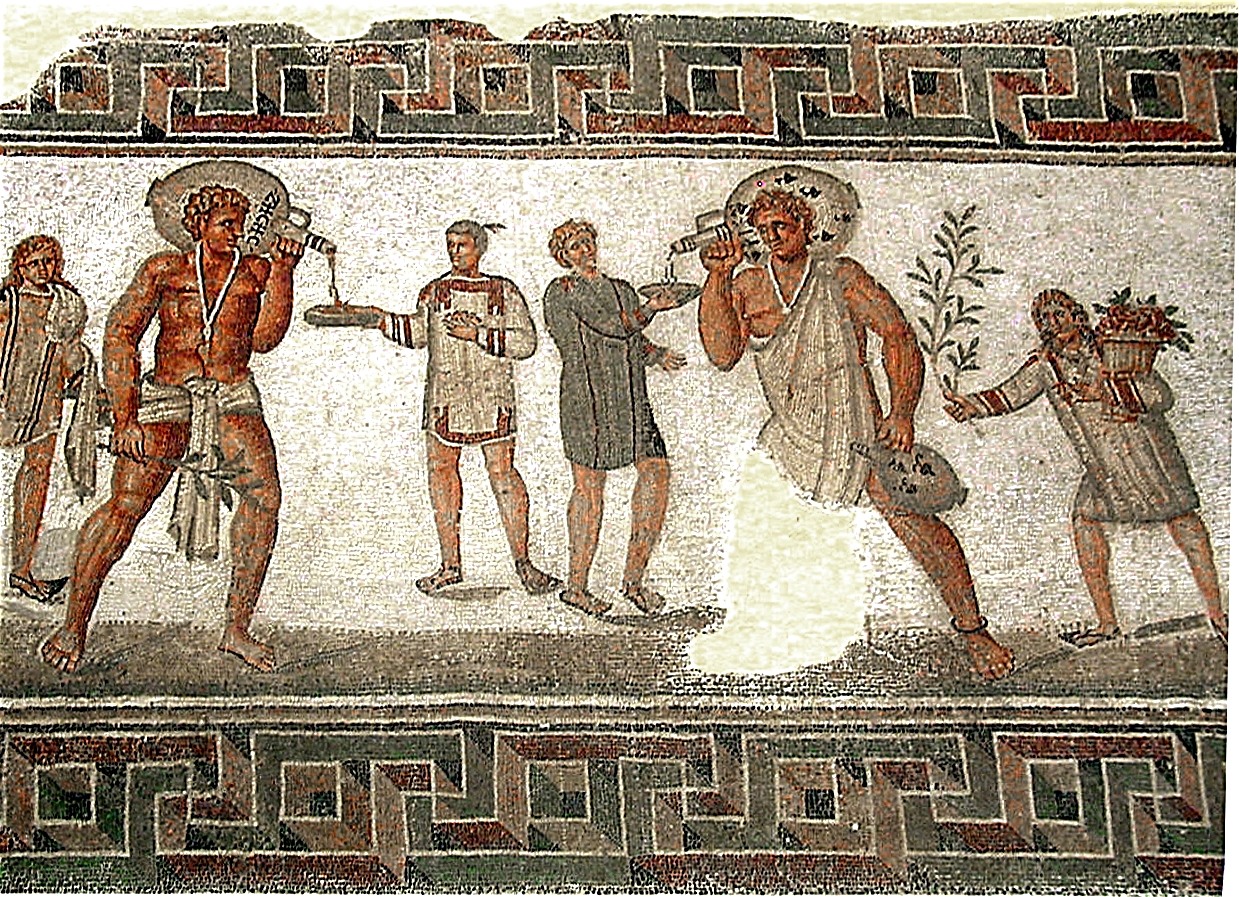

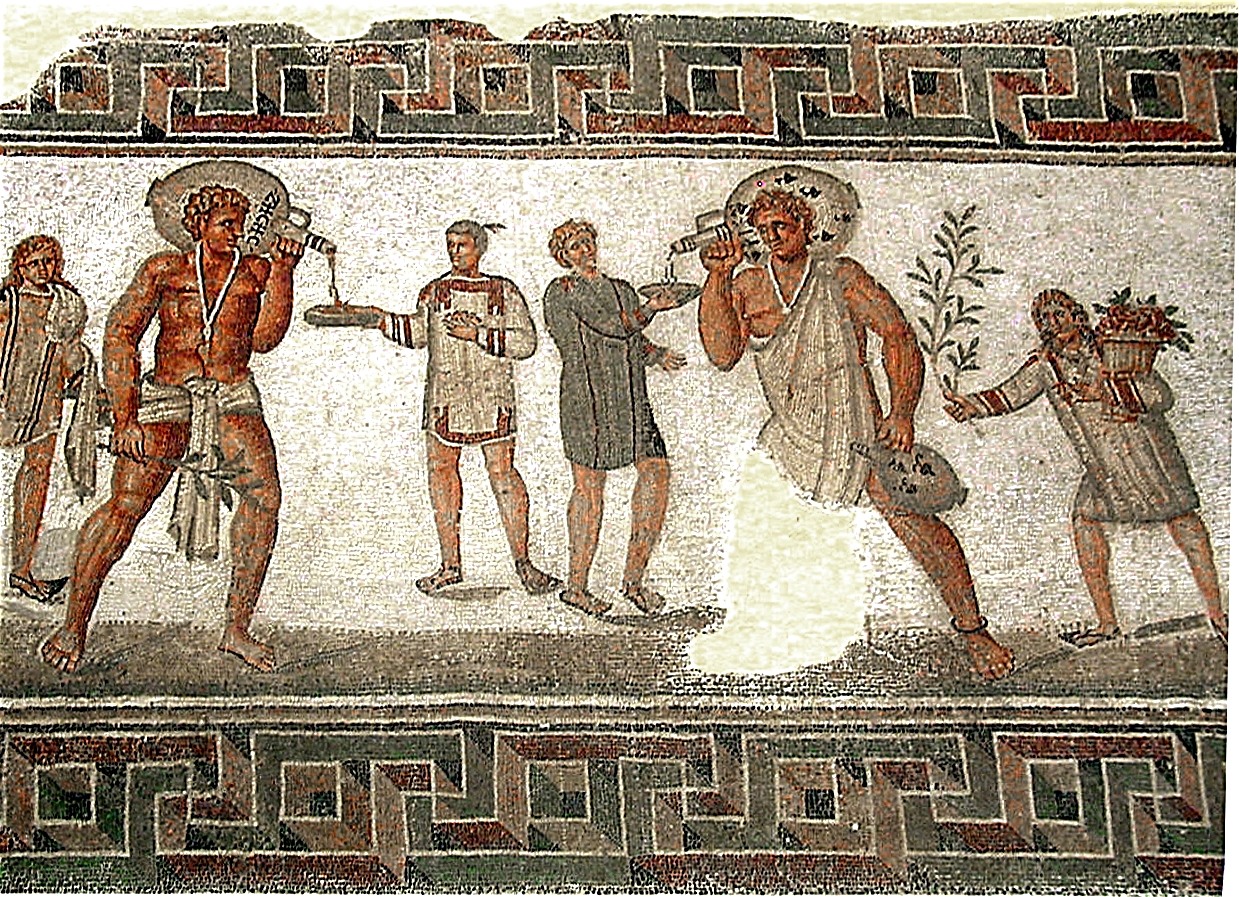

''Vernae'' (singular ''verna'') were slaves born within a household (''familia'') or on a family farm or agricultural estate (''villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

''). There was a stronger social obligation to care for ''vernae,'' whose epitaphs sometimes identify them as such, and at times they would have been the children of free males of the household. The general Latin word for slave was ''servus.''

Slavery and warfare

Throughout the Roman period, many slaves for the Roman market were acquired through warfare. Many captives were either brought back as warbooty

Booty may refer to:

Music

*Booty music (also known as Miami bass or booty bass), a subgenre of hip hop

* "Booty" (Jennifer Lopez song), 2014

*Booty (Blac Youngsta song), 2017

* Booty (C. Tangana and Becky G song), 2018

*"Booty", a 1993 song by G ...

or sold to traders, and ancient sources cite anywhere from hundreds to tens of thousands of such slaves captured in ''each'' war. These wars included every major war of conquest from the Monarchical period to the Imperial period, as well as the Social and Samnite Wars. The prisoners taken or retaken after the three Roman Servile Wars

The Servile Wars were a series of three slave revolts ("servile" is derived from "''servus''", Latin for "slave") in the late Roman Republic.

Wars

* First Servile War (135−132 BC) — in Sicily, led by Eunus, a former slave claiming to be a p ...

(135–132, 104–100, and 73–71 BC, respectively) also contributed to the slave supply.Fields, pp. 7, 8–10. While warfare during the Republic provided the largest figures for captives, warfare continued to produce slaves for Rome throughout the imperial period.

Piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

has a long history of adding to the slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and the period of the Roman Republic was no different. Piracy was particularly lucrative in Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

where pirates operated with impunity from a number of strongholds. Pompey was credited with effectively eradicating piracy from the Mediterranean in 67 BC. Although large-scale piracy was curbed under Pompey and controlled under the Roman Empire, it remained a steady institution, and kidnapping through piracy continued to contribute to the Roman slave supply. Augustine lamented the wide-scale practice of kidnapping in North Africa in the early 5th century AD.

Trade and economy

During the period of Roman imperial expansion, the increase in wealth amongst the Roman elite and the substantial growth of slavery transformed the economy.Hopkins, Keith. ''Conquerors and Slaves: Sociological Studies in Roman History''. Cambridge University Press, New York. Pgs. 4–5 Although the economy was dependent on slavery, Rome was not the most slave-dependent culture in history. Among the

During the period of Roman imperial expansion, the increase in wealth amongst the Roman elite and the substantial growth of slavery transformed the economy.Hopkins, Keith. ''Conquerors and Slaves: Sociological Studies in Roman History''. Cambridge University Press, New York. Pgs. 4–5 Although the economy was dependent on slavery, Rome was not the most slave-dependent culture in history. Among the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

ns, for instance, the slave class of helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ex ...

outnumbered the free by about seven to one, according to Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

. In any case, the overall role of slavery in Roman economy is a discussed issue among scholars.

Delos

The island of Delos (; el, Δήλος ; Attic: , Doric: ), near Mykonos, near the centre of the Cyclades archipelago, is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. The excavations in the island are ...

in the eastern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

was made a free port in 166 BC and became one of the main market venues for slaves. Multitudes of slaves who found their way to Italy were purchased by wealthy landowners in need of large numbers of slaves to labour on their estates. Historian Keith Hopkins

Morris Keith Hopkins, FBA (20 June 1934 – 8 March 2004) was a British historian and sociologist. He was professor of ancient history at the University of Cambridge from 1985 to 2000.

Hopkins had a relatively unconventional route to the Cam ...

noted that it was land investment and agricultural production

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

which generated great wealth in Italy, and considered that Rome's military conquests and the subsequent introduction of vast wealth and slaves into Italy had effects comparable to widespread and rapid technological innovations.

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

imposed a 2 percent tax on the sale of slaves, estimated to generate annual revenues of about 5 million sesterces

The ''sestertius'' (plural ''sestertii''), or sesterce (plural sesterces), was an ancient Roman coin. During the Roman Republic it was a small, silver coin issued only on rare occasions. During the Roman Empire it was a large brass coin.

The na ...

—a figure that indicates some 250,000 sales. The tax was increased to 4 percent by 43 AD. Slave markets seem to have existed in every city of the Empire, but outside Rome the major center was Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

.

Demography

Estimates for the prevalence of slavery in the Roman Empire vary. Estimates of the percentage of the population of Italy who were slaves range upwards of one to two million slaves in Italy by the end of the 1st century BC, about 20% to 30% of Italy's population. For the empire as a whole during the period 260–425 AD, according to a study by Kyle Harper, the slave population has been estimated at just under five million, representing 10–15% of the total population of 50–60 million inhabitants. An estimated 49% of all slaves were owned by the elite, who made up less than 1.5% of the empire's population. About half of all slaves worked in the countryside where they were a small percentage of the population except on some large agricultural, especially imperial, estates; the remainder of the other half were a significant percentage – 25% or more – in towns and cities as domestics and workers in commercial enterprises and manufacturers. Roman slavery was not based on ideas ofrace

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

. Slaves were drawn from all over Europe and the Mediterranean, including Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania ...

, North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great ...

, the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, etc. Those from outside of Europe were predominantly of Greek descent, while Jews never fully assimilated into Roman society, remaining an identifiable minority. The slaves (especially the foreigners) had higher mortality rates and lower birth rates than natives and were sometimes even subjected to mass expulsions. The average recorded age at death for the slaves of the city of Rome was extraordinarily low: seventeen and a half years (17.2 for males; 17.9 for females). By comparison, life expectancy at birth for the population as a whole was in the mid-twenties.

Auctions and sales

New slaves were primarily acquired by wholesale dealers who followed the Roman armies. Many people who bought slaves wanted strong slaves, mostly men. Child slaves cost less than adults although other sources state their price as higher.

New slaves were primarily acquired by wholesale dealers who followed the Roman armies. Many people who bought slaves wanted strong slaves, mostly men. Child slaves cost less than adults although other sources state their price as higher. Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

once sold the entire population of a conquered region in Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, no fewer than 53,000 people, to slave dealers on the spot.

Within the empire, slaves were sold at public auction

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

or sometimes in shops, or by private sale in the case of more valuable slaves. Slave dealing was overseen by the Roman fiscal officials called quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

s.

Sometimes slaves stood on revolving stands, and around each slave for sale hung a type of plaque describing their origin, health, character, intelligence, education, and other information pertinent to purchasers. Prices varied with age and quality, with the most valuable slaves fetching high prices. Because the Romans wanted to know ''exactly'' what they were buying, slaves were presented naked. The dealer was required to take a slave back within six months if the slave had defects that were not manifest at the sale, or make good the buyer's loss.Johnston, Mary. Roman Life. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company, 1957, p. 158–177 Slaves to be sold with no guarantee were made to wear a cap at the auction.

Debt slavery

''Nexum'' was adebt bondage

Debt bondage, also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage, is the pledge of a person's services as security for the repayment for a debt or other obligation. Where the terms of the repayment are not clearly or reasonably stated, the pe ...

contract in the early Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

. Within the Roman legal system, it was a form of ''mancipatio In Roman law, ''mancipatio'' (f. Latin ''manus'' "hand" and ''capere'' "to take hold of") was a solemn verbal contract by which the ownership of certain types of goods, called ''res mancipi'', was transferred.

''Mancipatio'' was also the legal proc ...

''. Though the terms of the contract would vary, essentially a free man pledged himself as a bond slave (''nexus'') as surety for a loan. He might also hand over his son as collateral. Although the bondsman could expect to face humiliation and some abuse, as a legal citizen he was supposed to be exempt from corporal punishment. ''Nexum'' was abolished by the ''Lex Poetelia Papiria

The ''lex Poetelia Papiria'' was a law passed in Ancient Rome that abolished the contractual form of Nexum, or debt bondage. Livy dates the law in 326 BC, during the third consulship of Gaius Poetelius Libo Visolus,Livy, ''History of Rome'' VIII. ...

'' in 326 BC, in part to prevent abuses to the physical integrity of citizens who had fallen into debt bondage.

Roman historians Roman historiography stretches back to at least the 3rd century BC and was indebted to earlier Greek historiography. The Romans relied on previous models in the Greek tradition such as the works of Herodotus (c. 484 – 425 BC) and Thucydides (c. ...

illuminated the abolition of ''nexum'' with a traditional story that varied in its particulars; basically, a ''nexus'' who was a handsome but upstanding youth suffered sexual harassment by the holder of the debt. In one version, the youth had gone into debt to pay for his father's funeral; in others, he had been handed over by his father. In all versions, he is presented as a model of virtue. Historical or not, the cautionary tale highlighted the incongruities of subjecting one free citizen to another's use, and the legal response was aimed at establishing the citizen's right to liberty (''libertas''), as distinguished from the slave or social outcast ('' infamis'').

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

considered the abolition of ''nexum'' primarily a political maneuver to appease the common people (''plebs

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizenship, Roman citizens who were not Patrician (ancient Rome), patricians, as determined by the capite censi, census, or in other words "commoners". Both ...

''): the law was passed during the Conflict of the Orders

The Conflict of the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the plebe ...

, when plebeians were struggling to establish their rights in relation to the hereditary privileges of the patricians

The patricians (from la, Wikt:patricius, patricius, Greek language, Greek: πατρίκιος) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom, and the early Roman Rep ...

. Although ''nexum'' was abolished as a way to secure a loan, debt bondage might still result after a debtor defaulted.

Types of work

Slaves worked in a wide range of occupations that can be roughly divided into five categories: household or domestic, imperial or public, urban crafts and services, agriculture, and mining.

Epitaphs record at least 55 different jobs a household slave might have,"Slavery in Rome," in ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome'' (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 323. including barber, butler, cook, hairdresser, handmaid (''ancilla''), wash their master's clothes,

Slaves worked in a wide range of occupations that can be roughly divided into five categories: household or domestic, imperial or public, urban crafts and services, agriculture, and mining.

Epitaphs record at least 55 different jobs a household slave might have,"Slavery in Rome," in ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome'' (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 323. including barber, butler, cook, hairdresser, handmaid (''ancilla''), wash their master's clothes, wet nurse

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, or if she is unable or chooses not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some cu ...

or nursery attendant, teacher, secretary, seamstress, accountant, and physician. A large elite household (a ''domus

In Ancient Rome, the ''domus'' (plural ''domūs'', genitive ''domūs'' or ''domī'') was the type of town house occupied by the upper classes and some wealthy freedmen during the Republican and Imperial eras. It was found in almost all the ma ...

'' in town, or a ''villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

'' in the countryside) might be supported by a staff of hundreds. The living conditions of slaves attached to a ''domus'' (the ''familia urbana''), while inferior to those of the free persons they lived with, were sometimes superior to that of many free urban poor in Rome. Household slaves likely enjoyed the highest standard of living among Roman slaves, next to publicly owned slaves, who were not subject to the whims of a single master. Imperial slaves were those attached to the emperor's household, the ''familia Caesaris''.

In urban workplaces, the occupations of slaves included fullers, engravers, shoemakers, bakers, mule drivers, and prostitutes

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

. Farm slaves (''familia rustica'') probably lived in more healthful conditions. Roman agricultural writers expect that the workforce of a farm will be mostly slaves, managed by a ''vilicus {{Unreferenced, date=June 2019, bot=noref (GreenC bot)

Vilicus ( el, ἐπίτροπος) was a servant who had the superintendence of the villa rustica, and of all the business of the farm, except the cattle, which were under the care of the magis ...

'', who was often a slave himself.

Slaves numbering in the tens of thousands were condemned to work in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal. ''Damnati in metallum'' ("those condemned to the mine") were convicts who lost their freedom as citizens (''libertas''), forfeited their property (''bona'') to the state, and became ''servi poenae'', slaves as a legal penalty. Their status under the law was different from that of other slaves; they could not buy their freedom, be sold, or be set free. They were expected to live and die in the mines. Imperial slaves and freedmen (the ''familia Caesaris)'' worked in mine administration and management.

In the Late Republic, about half the

Slaves numbering in the tens of thousands were condemned to work in the mines or quarries, where conditions were notoriously brutal. ''Damnati in metallum'' ("those condemned to the mine") were convicts who lost their freedom as citizens (''libertas''), forfeited their property (''bona'') to the state, and became ''servi poenae'', slaves as a legal penalty. Their status under the law was different from that of other slaves; they could not buy their freedom, be sold, or be set free. They were expected to live and die in the mines. Imperial slaves and freedmen (the ''familia Caesaris)'' worked in mine administration and management.

In the Late Republic, about half the gladiator

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gla ...

s who fought in Roman arenas were slaves, though the most skilled were often free volunteers. Successful gladiators were occasionally rewarded with freedom. However gladiators, being trained warriors and having access to weapons, were potentially the most dangerous slaves. At an earlier time, many gladiators had been soldiers taken captive in war. Spartacus

Spartacus ( el, Σπάρτακος '; la, Spartacus; c. 103–71 BC) was a Thracian gladiator who, along with Crixus, Gannicus, Castus, and Oenomaus, was one of the escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a major slave uprising ...

, who was a rebel gladiator, led the great slave rebellion of 73–71 BC.

''Servus publicus''

A ''servus publicus'' was a slave owned not by a private individual, but by theRoman people

grc, Ῥωμαῖοι,

, native_name_lang =

, image = Pompeii family feast painting Naples.jpg

, image_caption = 1st century AD wall painting from Pompeii depicting a multigenerational banquet

, languages =

, relig ...

. Public slaves worked in temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

and other public buildings both in Rome and in the municipalities

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the go ...

. Most performed general, basic tasks as servants to the College of Pontiffs

The College of Pontiffs ( la, Collegium Pontificum; see ''collegium'') was a body of the ancient Roman state whose members were the highest-ranking priests of the state religion. The college consisted of the '' pontifex maximus'' and the other '' ...

, magistrates

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

, and other officials. Some well-qualified public slaves did skilled office work such as accounting and secretarial services. They were permitted to earn money for their personal use.Adolf Berger. 1991. ''Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law''. American Philosophical Society (reprint). p. 706.

Because they had an opportunity to prove their merit, they could acquire a reputation and influence, and were sometimes deemed eligible for manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

. During the Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

, a public slave could be freed by a magistrate's declaration, with the prior authorization of the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

; in the Imperial era

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, liberty would be granted by the emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

. Municipal public slaves could be freed by the municipal council.

Treatment and legal status

According to

According to Marcel Mauss

Marcel Mauss (; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and a ...

, in Roman times the ''persona'' gradually became "synonymous with the true nature of the individual" but "the slave was excluded from it. ''servus non habet personam'' ('a slave has no persona'). He has no personality. He does not own his body; he has no ancestors, no name, no cognomen

A ''cognomen'' (; plural ''cognomina''; from ''con-'' "together with" and ''(g)nomen'' "name") was the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. Initially, it was a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became here ...

, no goods of his own." The testimony of a slave could not be accepted in a court of law unless the slave was tortured—a practice based on the belief that slaves in a position to be privy to their masters' affairs would be too virtuously loyal to reveal damaging evidence unless coerced.

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

differed from Greek city-states

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

in allowing freed slaves to become citizens. After manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing enslaved people by their enslavers. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that t ...

, a male slave who had belonged to a Roman citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (''libertas''), including the right to vote. A slave who had acquired ''libertas'' was thus a ''libertus'' ("freed person", feminine

Femininity (also called womanliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with women and girls. Femininity can be understood as socially constructed, and there is also some evidence that some behaviors considered fe ...

''liberta'') in relation to his former master, who then became his patron ('' patronus''). As a social class, freed slaves were ''libertini'', though later writers used the terms ''libertus'' and ''libertinus'' interchangeably. ''Libertini'' were not entitled to hold public office

Public Administration (a form of governance) or Public Policy and Administration (an academic discipline) is the implementation of public policy, administration of government establishment (public governance), management of non-profit establ ...

or state priesthoods, nor could they achieve senatorial rank. During the early Empire, however, freedmen held key positions in the government bureaucracy, so much so that Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

limited their participation by law. Any future children of a freedman would be born free, with full rights of citizenship.

Although in general freed slaves could become citizens, with the right to vote if they were male, those categorized as ''dediticii

In the Roman Empire, the ''dediticii'' were one of the three classes of '' libertini''. The ''dediticii'' existed as a class of persons who were neither slaves, nor Roman citizens ''(cives)'', nor ''Latini'' (that is, those holding Latin rights), ...

'' suffered permanent disbarment from citizenship. The ''dediticii'' were mainly slaves whose masters had felt compelled to punish them for serious misconduct by placing them in chains, branding them, torturing them to confess a crime, imprisoning them or sending them involuntarily to a gladiatorial school (''ludus''), or condemning them to fight with gladiators or wild beasts

Wild Beasts were an English indie rock band, formed in 2002 in Kendal. They released their first single, "Brave Bulging Buoyant Clairvoyants", on Bad Sneakers Records in November 2006, and subsequently signed to Domino Records. They have rele ...

. ''Dediticii'' were regarded as a threat to society, regardless of whether their master's punishments had been justified, and if they came within a hundred miles of Rome, they were subject to reenslavement.

Roman slaves could hold property which, despite the fact that it belonged to their masters, they were allowed to use as if it were their own. Skilled or educated slaves were allowed to earn their own money, and might hope to save enough to buy their freedom. Such slaves were often freed by the terms of their master's will, or for services rendered. A notable example of a high-status slave was Tiro

Marcus Tullius Tiro (died 4 BC) was first a slave, then a freedman, of Cicero from whom he received his nomen and praenomen. He is frequently mentioned in Cicero's letters. After Cicero's death Tiro published his former master's collecte ...

, the secretary of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

. Tiro was freed before his master's death, and was successful enough to retire on his own country estate, where he died at the age of 99. However, the master could arrange that slaves would only have enough money to buy their freedom when they were too old to work. They could then use the money to buy a new young slave while the old slave, unable to work, would be forced to rely on charity to stay alive.

Several emperors began to grant more rights to slaves as the empire grew. Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

announced that if a slave was abandoned by his master, he became free. Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

granted slaves the right to complain against their masters in a court. And under Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius (Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatoria ...

, a master who killed a slave without just cause could be tried for homicide. Legal protection of slaves continued to grow as the empire expanded. It became common throughout the mid to late 2nd century AD to allow slaves to complain of cruel or unfair treatment by their owners. Attitudes changed in part because of the influence among the educated elite of the Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

, whose egalitarian views of humanity extended to slaves.

There are reports of abuse of slaves by Romans, but there is little information to indicate how widespread such harsh treatment was. Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor ( la, Censorius), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He was the first to write histo ...

was recorded as expelling his old or sick slaves from his house. Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

in his Letter 47 expressed the view that a slave who was treated well would perform a better job than a poorly treated slave. As most slaves in the Roman world could easily blend into the population if they escaped, it was normal for the masters to discourage slaves from running away by putting a tattoo reading "Stop me! I am a runaway!" or "tax paid" if the slaves were owned by the Roman state on the foreheads of their slaves. For this reason, slaves usually wore headbands to cover up their disfiguring tattoos and at the Temple of Asclepius

Asclepius (; grc-gre, Ἀσκληπιός ''Asklēpiós'' ; la, Aesculapius) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of ...

, the Greek god of healing, in Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

, archeologists have found thousands of tablets from escaped slaves asking Asclepius to make the tattoos on their foreheads disappear. Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

was the capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

meted out specifically to slaves, traitors, and bandits. Marcus Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (; 115 – 53 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is often called "the richest man in Rome." Wallechinsky, David & Wallace, I ...

was supposed to have concluded his victory over Spartacus in the Third Servile War

The Third Servile War, also called the Gladiator War and the War of Spartacus by Plutarch, was the last in a series of slave rebellions against the Roman Republic known as the Servile Wars. This third rebellion was the only one that directly ...

by crucifying 6,000 of the slave rebels along the Appian Way

The Appian Way (Latin and Italian language, Italian: ''Via Appia'') is one of the earliest and strategically most important Roman roads of the ancient Roman Republic, republic. It connected Rome to Brindisi, in southeast Italy. Its importance is ...

.

Rebellions and runaways

Moses Finley

Sir Moses Israel Finley, FBA (born Finkelstein; 20 May 1912 – 23 June 1986) was an American-born British academic and classical scholar. His prosecution by the United States Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security during the 1950s, resulted ...

remarked, "fugitive slaves are almost an obsession in the sources". Rome forbade the harbouring of fugitive slaves, and professional slave-catchers were hired to hunt down runaways. Advertisements were posted with precise descriptions of escaped slaves, and offered rewards. If caught, fugitives could be punished by being whipped, burnt with iron, or killed. Those who lived were branded on the forehead with the letters FUG, for ''fugitivus''. Sometimes slaves had a metal collar riveted around the neck. One such collar is preserved at Rome and states in Latin, "I have run away. Catch me. If you take me back to my master Zoninus, you'll be rewarded."

There was a constant danger of servile insurrection, which had more than once seriously threatened the republic. The 1st century BC Greek historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

wrote that slaves sometimes banded together to plot revolts. He chronicled the three major slave rebellions: in 135–132 BC (the First Servile War

The First Servile War of 135–132 BC was a slave rebellion against the Roman Republic, which took place in Sicily. The revolt started in 135 when Eunus, a slave from Syria who claimed to be a prophet, captured the city of Enna in the middle o ...

), in 104–100 BC (the Second Servile War

The Second Servile War was an unsuccessful slave uprising against the Roman Republic on the island of Sicily. The war lasted from 104 BC until 100 BC.

Background

The Consul Gaius Marius was recruiting soldiers for the war against the Cimbri and ...

), and in 73–71 BC (the Third Servile War).

Serfdom

In addition to slavery, the Romans also practicedserfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. By the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

faced a labour shortage. Large Roman landowners increasingly relied on Roman freemen, acting as tenant farmers

A tenant farmer is a person (farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management, ...

, instead of slaves to provide labour. The status of these tenant farmers, eventually known as coloni, steadily eroded. Because the tax system implemented by Diocletian assessed taxes based on both land and the inhabitants of that land, it became administratively inconvenient for peasants to leave the land where they were counted in the census. In 332 AD Emperor Constantine

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterranea ...

issued legislation that greatly restricted the rights of the coloni and tied them to the land. Some see these laws as the beginning of medieval serfdom in Europe.

Slavery in philosophy and religion

Classical Roman religion

Thereligious holiday

A holiday is a day set aside by custom or by law on which normal activities, especially business or work including school, are suspended or reduced. Generally, holidays are intended to allow individuals to celebrate or commemorate an event or tra ...

most famously celebrated by slaves at Rome was the Saturnalia

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple ...

, a December festival of role reversals during which time slaves enjoyed a rich banquet, gambling, free speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been ...

and other forms of license not normally available to them. To mark their temporary freedom, they wore the '' pilleus'', the cap of freedom, as did free citizens, who normally went about bareheaded. Some ancient sources suggest that master and slave dined together, while others indicate that the slaves feasted first, or that the masters actually served the food. The practice may have varied over time. Macrobius

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, usually referred to as Macrobius (fl. AD 400), was a Roman provincial who lived during the early fifth century, during late antiquity, the period of time corresponding to the Later Roman Empire, and when Latin was ...

(5th century AD) describes the occasion thus:

Meanwhile, the head of the slave household, whose responsibility it was to offer sacrifice to thePenates In ancient Roman religion, the Di Penates () or Penates ( ) were among the ''dii familiares'', or household deities, invoked most often in domestic rituals. When the family had a meal, they threw a bit into the fire on the hearth for the Penates. ..., to manage the provisions and to direct the activities of the domestic servants, came to tell his master that the household had feasted according to the annual ritual custom. For at this festival, in houses that keep to proper religious usage, they first of all honor the slaves with a dinner prepared as if for the master; and only afterwards is the table set again for the head of the household. So, then, the chief slave came in to announce the time of dinner and to summon the masters to the table.

Saturnalia

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple ...

n license also permitted slaves to enjoy a pretense of disrespect for their masters, and exempted them from punishment. The Augustan poet Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

calls their freedom of speech "December liberty" (''libertas Decembri''). In two satires

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

set during the Saturnalia, Horace portrays a slave as offering sharp criticism to his master. But everyone knew that the leveling of the social hierarchy

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). As su ...

was temporary and had limits; no social norms were ultimately threatened, because the holiday would end.

Another slaves' holiday (''servorum dies festus'') was held August 13 in honor of Servius Tullius

Servius Tullius was the legendary sixth king of Rome, and the second of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned from 578 to 535 BC. Roman and Greek sources describe his servile origins and later marriage to a daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Rome ...

, the legendary sixth king of Rome

The king of Rome ( la, rex Romae) was the ruler of the Roman Kingdom. According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 BC upon the Palatine Hill. Seven legendary kings are said to have ruled Rome until 509 ...

who was the child of a slave woman. Like the Saturnalia, the holiday involved a role reversal: the matron of the household washed the heads of her slaves, as well as her own.

The temple of Feronia Feronia may mean:

* Feronia (mythology), a goddess of fertility in Roman and Etruscan mythology

* ''Feronia'' (plant), a genus of plants

* Feronia Inc., a plantations company operating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

* Feronia (Sardinia) ...

at Terracina

Terracina is an Italian city and ''comune'' of the province of Latina, located on the coast southeast of Rome on the Via Appia ( by rail). The site has been continuously occupied since antiquity.

History Ancient times

Terracina appears in anci ...

in Latium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil (Old Latium) on whi ...

was the site of special ceremonies pertaining to manumission. The goddess was identified with Libertas

Libertas (Latin for 'liberty' or 'freedom', ) is the Roman goddess and personification of liberty. She became a politicised figure in the Late Republic, featured on coins supporting the populares faction, and later those of the assassins of Jul ...

, the personification of liberty, and was a tutelary goddess

A tutelary () (also tutelar) is a deity or a spirit who is a guardian, patron, or protector of a particular place, geographic feature, person, lineage, nation, culture, or occupation. The etymology of "tutelary" expresses the concept of safety and ...

of freedmen (''dea libertorum''). A stone at her temple was inscribed "let deserving slaves sit down so that they may stand up free."

Female slaves and religion

At theMatralia

Mater Matuta was an indigenous Latin goddess, whom the Romans eventually made equivalent to the dawn goddess Aurora, and the Greek goddess Eos. Her cult is attested several places in Latium; her most famous temple was located at Satricum. In Rom ...

, a women's festival held June 11 in connection with the goddess Mater Matuta

Mater Matuta was an indigenous Latin goddess, whom the Romans eventually made equivalent to the dawn goddess Aurora, and the Greek goddess Eos. Her cult is attested several places in Latium; her most famous temple was located at Satricum. In Rome ...

, free women ceremonially beat a slave girl and drove her from the community. Slave women were otherwise forbidden from participation.

Slave women were honored at the ''Ancillarum Feria

In the liturgy of the Catholic Church, a feria is a day of the week other than Sunday.

In more recent official liturgical texts in English, the term ''weekday'' is used instead of ''feria''.

If the feast day of a saint falls on such a day, the ...

e'' on July 7. The holiday is explained as commemorating the service rendered to Rome by a group of ''ancillae'' (female slaves or "handmaids") during the war with the Fidenates

Fidenae ( grc, Φιδῆναι) was an ancient town of Latium, situated about 8 km north of Rome on the ''Via Salaria'', which ran between Rome and the Tiber. Its inhabitants were known as Fidenates. As the Tiber was the border between Etru ...

in the late 4th century BC. Weakened by the Gallic sack of Rome

The Battle of the Allia was a battle fought between the Senones – a Gallic tribe led by Brennus, who had invaded Northern Italy – and the Roman Republic. The battle was fought at the confluence of the Tiber and Allia rivers, 11 Roman mile ...

in 390 BC, the Romans next had suffered a stinging defeat by the Fidenates, who demanded that they hand over their wives and virgin daughters as hostages to secure a peace. A handmaid named either Philotis

''Loryma'' is a genus of snout moths described by Francis Walker in 1859.

Species

*'' Loryma actenioides'' (Rebel, 1914)

*'' Loryma alluaudalis'' Leraut, 2009

*'' Loryma ambovombealis'' Leraut, 2009

*'' Loryma aridalis'' Rothschild, 1913

*'' ...

or Tutula came up with a plan to deceive the enemy: the ''ancillae'' would put on the apparel of the free women, spend one night in the enemy camp, and send a signal to the Romans about the most advantageous time to launch a counterattack. Although the historicity of the underlying tale may be doubtful, it indicates that the Romans thought they had already had a significant slave population before the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146BC fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage. Three conflicts between these states took place on both land and sea across the western Mediterranean region and i ...

.

Mystery cults

TheMithraic mysteries

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (''yazata'') Mithra, the Roman Mithras is lin ...

were open to slaves and freedmen, and at some cult sites most or all votive offerings

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally ...

are made by slaves, sometimes for the sake of their masters' wellbeing. The cult of Mithras, which valued submission to authority and promotion through a hierarchy, was in harmony with the structure of Roman society, and thus the participation of slaves posed no threat to social order.

Stoic philosophy

TheStoic

Stoic may refer to:

* An adherent of Stoicism; one whose moral quality is associated with that school of philosophy

*STOIC, a programming language

* ''Stoic'' (film), a 2009 film by Uwe Boll

* ''Stoic'' (mixtape), a 2012 mixtape by rapper T-Pain

*' ...

s taught that all men were manifestations of the same universal spirit, and thus by nature equal. Stoicism also held that external circumstances (such as being enslaved) did not truly impede a person from practicing the Stoic ideal of inner self-mastery: It has been said that one of the more important Roman stoics, Epictetus

Epictetus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκτητος, ''Epíktētos''; 50 135 AD) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia (present-day Pamukkale, in western Turkey) and lived in Rome until his banishment, when ...

, spent his youth as a slave.

Early Christianity

Both the Stoics and someearly Christians

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

opposed the ill treatment of slaves, rather than slavery itself. Advocates of these philosophies saw them as ways to live within human societies as they were, rather than to overthrow entrenched institutions. In the Christian scriptures, equal pay and fair treatment of slaves was enjoined upon slave masters, and slaves were advised to obey their earthly masters, even if their masters are unfair, and lawfully obtain freedom if possible.

Certain senior Christian leaders (such as Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( grc-gre, Γρηγόριος Νύσσης; c. 335 – c. 395), was Bishop of Nyssa in Cappadocia from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 395. He is venerated as a saint in Catholici ...

and John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his homilies, preaching and public speaking, his denunciat ...

) called for good treatment for slaves and condemned slavery, while others supported it. Christianity gave slaves an equal place within the religion, allowing them to participate in the liturgy. According to tradition, Pope Clement I

Pope Clement I ( la, Clemens Romanus; Greek: grc, Κλήμης Ῥώμης, Klēmēs Rōmēs) ( – 99 AD) was bishop of Rome in the late first century AD. He is listed by Irenaeus and Tertullian as the bishop of Rome, holding office from 88 AD t ...

(term c. 92–99), Pope Pius I

Pope Pius I was the bishop of Rome from 140 to his death 154, according to the ''Annuario Pontificio''. His dates are listed as 142 or 146 to 157 or 161, respectively. He is considered to have opposed both the Valentinians and Gnostics during h ...

(158–167) and Pope Callixtus I

Pope Callixtus I, also called Callistus I, was the bishop of Rome (according to Sextus Julius Africanus) from c. 218 to his death c. 222 or 223.Chapman, John (1908). "Pope Callistus I" in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Ap ...

(c. 217–222) were former slaves.

Writing after the legalization of Christianity by Roman authorities, Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

, who came from an aristocratic background and likely grew up in home where slave labor was utilized, described slavery as being against God's intention and resulting from sin. By the early 4th century, the manumission within the church, was incorporated into Roman law. Slaves could be freed by a ritual in a church, officiated by an ordained bishop or priest. Subsequent laws, such as the ''Novella 142'' of Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

in the sixth century, gave to the bishops the power to free slaves.

The early Christian Church never renounced slavery as an institution outright, choosing instead to promote more humane treatment for slaves who according to the Church were commanded by God to obey their earthly masters. In contrast to the pagan Roman viewpoint, Roman Christians, even those who were not abolitionists, preached that slaves were still human and not property. Overall Roman attitudes towards slavery generally emphasized more humane treatment of slaves and promoted manumission. Sexual slavery was strictly forbidden by the Church and institutions as gladiator matches, would come to be outlawed due to Christian pressure.

In literature

Although ancient authors rarely discussed slavery in terms of morals, because their society did not view slavery as the moral dilemma we do today, they included slaves and the treatment of slaves in works in order to shed light on other topics—history, economy, an individual's character—or to entertain and amuse. Texts mentioning slaves include histories, personal letters, dramas, and satires, includingPetronius

Gaius Petronius Arbiter"Gaius Petronius Arbiter"

Banquet of Trimalchio'', in which the eponymous freedman asserts "Slaves too are men. The milk they have drunk is just the same even if an evil fate has oppressed them." Many literary works may have served to help educated Roman slave owners navigate acceptability in the master-slave relationships in terms of slaves' behavior and punishment. To achieve this navigation of acceptability, works often focus on extreme cases, such as the crucifixion of hundreds of slaves for the murder of their master. We must be careful to recognize these instances as exceptional and yet recognize that the underlying problems must have concerned the authors and audiences. Examining the literary sources that mention ancient slavery can reveal both the context for and contemporary views of the institution. The following examples provide a sampling of different genres and portrayals.

The sight of a freedman was a more common one in Rome than other civilization. Former slaves became ''liberties/a'' to their former patrons (''patrons/a)'' and ''libertinus/a'' to the rest of society. Both freedman and former patrons had mutual obligations to each other within the traditional patronage network but freedmen also had the ability to “network” with other patrons as well.

Under their new social status, freedmen would take their former patron's name and start their own lineage. Men could vote and participate in politics, with some limitations. This included not being able to run for office, nor be admitted to the senatorial class. The children of former slaves, however, enjoyed the full privileges of Roman citizenship without restrictions.

Some freedmen became very powerful. They held important roles in the Roman government. Those who were part of the Imperial families often were the main functionaries in the Imperial administration. Some rose to positions of great influence, such as Narcissus, a former slave of the Emperor

The sight of a freedman was a more common one in Rome than other civilization. Former slaves became ''liberties/a'' to their former patrons (''patrons/a)'' and ''libertinus/a'' to the rest of society. Both freedman and former patrons had mutual obligations to each other within the traditional patronage network but freedmen also had the ability to “network” with other patrons as well.

Under their new social status, freedmen would take their former patron's name and start their own lineage. Men could vote and participate in politics, with some limitations. This included not being able to run for office, nor be admitted to the senatorial class. The children of former slaves, however, enjoyed the full privileges of Roman citizenship without restrictions.

Some freedmen became very powerful. They held important roles in the Roman government. Those who were part of the Imperial families often were the main functionaries in the Imperial administration. Some rose to positions of great influence, such as Narcissus, a former slave of the Emperor

Banquet of Trimalchio'', in which the eponymous freedman asserts "Slaves too are men. The milk they have drunk is just the same even if an evil fate has oppressed them." Many literary works may have served to help educated Roman slave owners navigate acceptability in the master-slave relationships in terms of slaves' behavior and punishment. To achieve this navigation of acceptability, works often focus on extreme cases, such as the crucifixion of hundreds of slaves for the murder of their master. We must be careful to recognize these instances as exceptional and yet recognize that the underlying problems must have concerned the authors and audiences. Examining the literary sources that mention ancient slavery can reveal both the context for and contemporary views of the institution. The following examples provide a sampling of different genres and portrayals.

Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

mentioned slavery in his biographical history in order to pass judgement on men's characters. In his ''Life of Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor ( la, Censorius), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He was the first to write histo ...

'', Plutarch revealed contrasting views of slaves. He wrote that Cato, known for his stringency, would resell his old servants because "no useless servants were fed in his house", but that he himself believes that "it marks an over-rigid temper for a man to take the work out of his servants as out of brute beasts".Mellor, Ronald. ''The Historians of Ancient Rome.'' New York: Routledge, 1997. (467).

Cicero

A prolific letter writer,Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

even wrote letters to one of his administrative slaves, one Marcus Tullius Tiro

Marcus Tullius Tiro (died 4 BC) was first a slave, then a freedman, of Cicero from whom he received his nomen and praenomen. He is frequently mentioned in Cicero's letters. After Cicero's death Tiro published his former master's collected w ...