Venustiano Carranza on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

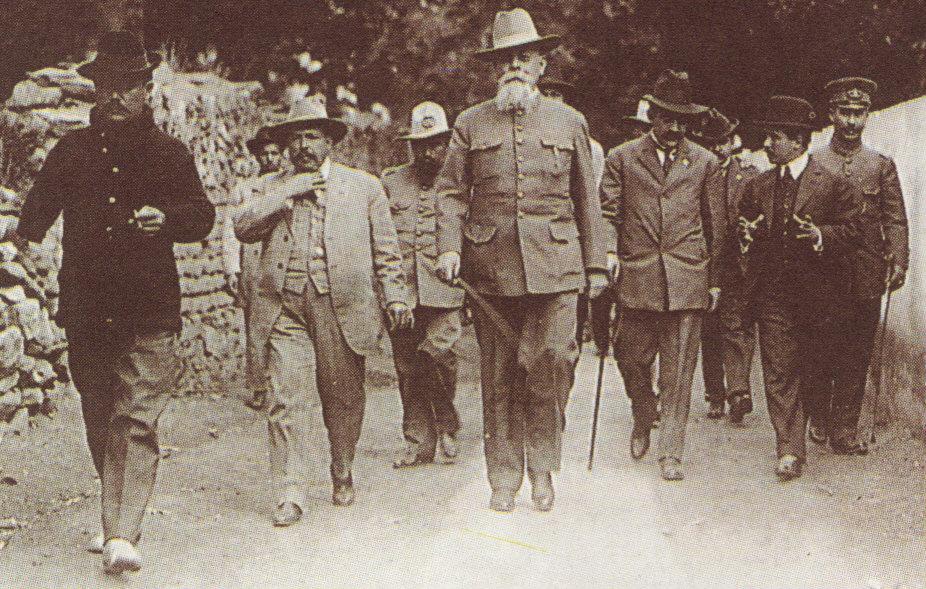

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920) was a Mexican wealthy land owner and politician who was Governor of Coahuila when the constitutionally elected president Francisco I. Madero was overthrown in a February 1913 right-wing military coup.

Known as the ''Primer Jefe'' or "First Chief" of the Constitutionalist faction in the Mexican Revolution, Carranza was a shrewd civilian politician. He supported Madero's challenge to the Díaz regime in the 1910 elections, but became a critic of Madero once Díaz was overthrown in May 1911. Madero did appoint him the

Carranza was born in the town of Cuatro Ciénegas, in the state of

Carranza was born in the town of Cuatro Ciénegas, in the state of

Carranza declared himself in rebellion against the government installed by the coup. Carranza's declaration against Huerta was a decisive stand. He had political legitimacy as a state governor, a modest record of state reform, popular support in his state, and an able politician, forging alliances to create a broad northern coalition against Huerta. It came to be known as the Constitutionalists, taking their name for the defense of the liberal Constitution of 1857. He was both the titular leader of the movement, as well as the actually leader in many circumstances.

In late February 1913, Carranza asked the legislature of Coahuila to declare itself formally in a state of rebellion against Huerta's government. He had built a state militia, funded by levying new taxes on enterprises, it could not withstand the well-armed, substantial force of the Federal Army controlled by General, now President, Huerta. The Coahuila militia suffered defeats at Anhelo, Saltillo, and Monclova, forcing Carranza to flee to Sonora a revolutionary stronghold.Katz, ''The Secret War in Mexico'', 130 Before he left Coahuila, he returned to his hacienda of Guadalupe, where he found a group of young men,

Carranza declared himself in rebellion against the government installed by the coup. Carranza's declaration against Huerta was a decisive stand. He had political legitimacy as a state governor, a modest record of state reform, popular support in his state, and an able politician, forging alliances to create a broad northern coalition against Huerta. It came to be known as the Constitutionalists, taking their name for the defense of the liberal Constitution of 1857. He was both the titular leader of the movement, as well as the actually leader in many circumstances.

In late February 1913, Carranza asked the legislature of Coahuila to declare itself formally in a state of rebellion against Huerta's government. He had built a state militia, funded by levying new taxes on enterprises, it could not withstand the well-armed, substantial force of the Federal Army controlled by General, now President, Huerta. The Coahuila militia suffered defeats at Anhelo, Saltillo, and Monclova, forcing Carranza to flee to Sonora a revolutionary stronghold.Katz, ''The Secret War in Mexico'', 130 Before he left Coahuila, he returned to his hacienda of Guadalupe, where he found a group of young men,

Both Villa and Zapata appealed to the peasantry, but not to the urban working class. Carranza did and used it to his advantage. Workers were predisposed to support Carranza, since he had taken such a strong stance against the U.S. occupation of Veracruz and he was stance on foreign-owned enterprises put him on the workers' side. Where the Carracista armies were victorious in cities, Carranza encouraged the formation of labor unions. Carranza negotiated with the anarcho-syndicalist labor organization, the Casa del Obrero Mundial, which formed Red Battalions to battle Zapatas' and Villas' in exchange for Carranza's promise to pass labor laws favorable to the working class. Among their ranks were artisans, including men in the building trades and typesetters rather than industrial workers. The most well-known member of the 6,000-strong Red Battalions was the painter

Both Villa and Zapata appealed to the peasantry, but not to the urban working class. Carranza did and used it to his advantage. Workers were predisposed to support Carranza, since he had taken such a strong stance against the U.S. occupation of Veracruz and he was stance on foreign-owned enterprises put him on the workers' side. Where the Carracista armies were victorious in cities, Carranza encouraged the formation of labor unions. Carranza negotiated with the anarcho-syndicalist labor organization, the Casa del Obrero Mundial, which formed Red Battalions to battle Zapatas' and Villas' in exchange for Carranza's promise to pass labor laws favorable to the working class. Among their ranks were artisans, including men in the building trades and typesetters rather than industrial workers. The most well-known member of the 6,000-strong Red Battalions was the painter

The new constitution was proclaimed on 5 February 1917. Carranza had no strong opposition to his election as president. In May 1917, Carranza became the constitutional

The new constitution was proclaimed on 5 February 1917. Carranza had no strong opposition to his election as president. In May 1917, Carranza became the constitutional

Carranza maintained a policy of formal neutrality during World War I, influenced by the anti-American sentiment that the United States' various interventions and invasions during the last century had caused.Stacy, Lee (2002).

Carranza maintained a policy of formal neutrality during World War I, influenced by the anti-American sentiment that the United States' various interventions and invasions during the last century had caused.Stacy, Lee (2002).

Mexico and the United States, Volume 3

', p. 869, Marshall Cavendish, USA.

Encyclopedia of U.S. Military Interventions in Latin America

', p. 393, ABC-CLIO, USA.Vollmer, Susan (2007).

Legends, Leaders, Legacies

', p. 79, Biography & Autobiography, USA. The assassination of Madero and José María Pino Suárez triggered a civil war that ended when the Constitutional Army defeated the forces of former ally Pancho Villa in the Battle of Celaya in April 1915. The partial peace allowed a new liberal constitution to be drafted in 1916 and proclaimed on February 5, 1917. Relations between Carranza and Wilson were often strained, particularly after the proclamation of the new constitution, which marked the participation of Mexico in the Great War.Meyer, Lorenzo (1977).

Mexico and the United States in the oil controversy, 1917-1942

', p. 45, University of Texas Press, USA.Halevy, Drew Philip (2000).

Threats of Intervention: U. S.-Mexican Relations, 1917-1923

', p. 41, iUniverse, USA. Nevertheless, Carranza was able to make the best out of a complicated situation; his government was officially recognized by Germany at the beginning of 1917, and by the United States on August 31, 1917, the latter as a direct consequence of the Zimmermann telegram' as a measure to ensure Mexico's continued neutrality in the war.Paterson, Thomas; Clifford, J. Garry; Brigham, Robert; Donoghue, Michael; Hagan, Kenneth (2010).

American Foreign Relations, Volume 1: To 1920

', p. 265, Cengage Learning, USA.Paterson, Thomas; Clifford, John Garry; Hagan, Kenneth J. (1999).

American Foreign Relations: A History since 1895

', p. 51, Houghton Mifflin College Division, USA. After the United States occupation of Veracruz in 1914, Mexico would not participate with the US in its military excursion in the Great War, so ensuring Mexican neutrality was the best deal. Carranza gave guarantees to German companies so they would keep their operations going, specifically in Mexico City, though he was at the same time selling oil to the British (eventually, over 75 percent of the fuel used by the British fleet came from Mexico).Buchenau, Jürgen (2004).

Tools of Progress: A German Merchant Family in Mexico City, 1865-present

', p. 82,

Mexico and the United States in the oil controversy, 1917-1942

p. 253, University of Texas Press, USA. Carranza stopped short of accepting Germany's proposed military alliance, made via the Zimmermann Telegram, and was at the same time able to prevent yet another military invasion from its northern neighbor, who wanted to take control of Tehuantepec Isthmus and Tampico oil fields.Gruening, Ernest (1968).

Mexico and Its Heritage

', p. 596, Greenwood Press, USA.Haber, Stephen; Maurer, Noel; Razo, Armando (2003).

The Politics of Property Rights: Political Instability, Credible Commitments, and Economic Growth in Mexico, 1876-1929

', p. 201,

The Politics of Mexican Oil

', p. 10, University of Pittsburgh Press, USA.Meyer, Lorenzo (1977)

''Mexico and the United States in the oil controversy, 1917-1942''

p. 44, University of Texas Press, USA.

Since Porfirio Díaz's continuous re-election had been one of the major factors in his ouster, Carranza prudently decided against running for re-election in 1920. His natural successor was Álvaro Obregón, the Constitutionalist general who defeated Pancho Villa. Believing that Mexico should have a civilian president, Carranza endorsed Ignacio Bonillas, an obscure diplomat who had represented Mexico in Washington, for the presidency. As government supporters suppressed and killed those for Obregón, the general decided that Carranza would never leave the office peacefully. Obregón and allied Sonoran generals (including

Since Porfirio Díaz's continuous re-election had been one of the major factors in his ouster, Carranza prudently decided against running for re-election in 1920. His natural successor was Álvaro Obregón, the Constitutionalist general who defeated Pancho Villa. Believing that Mexico should have a civilian president, Carranza endorsed Ignacio Bonillas, an obscure diplomat who had represented Mexico in Washington, for the presidency. As government supporters suppressed and killed those for Obregón, the general decided that Carranza would never leave the office peacefully. Obregón and allied Sonoran generals (including

After Carranza's death, Obregón prosecuted Colonel Herrero for Carranza's murder, but the colonel was acquitted. Obregón absented himself from Mexico City when Carranza's body was brought to the capital for burial. A newspaper reported that there were some 30,000 Carranza supporters at the funeral cortege. Carranza's body was buried in the municipal Dolores Cemetery, which does have a section for illustrious Mexicans. He was buried among ordinary Mexicans in a third class section. The family retained Carranza's heart, which was reunited with the rest of his remains when he was reburied in the Monument to the Revolution in 1942.

In life, the Sonoran Dynasty had characterized Carranza as "the most corrupt in the annals of the Mexican government". Toward the end of Álvaro Obregón's presidency (1920–24), his office contacted Carranza's daughter Julia, saying that the she was due a pension because "Venustiano Carranza gave eminent services to the Revolution and to the Nation." She and her brother refused the pension, replying bitterly to his letter that Obregón was responsible for her father's death and no amount of money could compensate for his loss. The Carranzas signed it "Your loyal enemies, Julia, Emilio, Venustiano, and Jesús Carranza."

After Carranza's death, Obregón prosecuted Colonel Herrero for Carranza's murder, but the colonel was acquitted. Obregón absented himself from Mexico City when Carranza's body was brought to the capital for burial. A newspaper reported that there were some 30,000 Carranza supporters at the funeral cortege. Carranza's body was buried in the municipal Dolores Cemetery, which does have a section for illustrious Mexicans. He was buried among ordinary Mexicans in a third class section. The family retained Carranza's heart, which was reunited with the rest of his remains when he was reburied in the Monument to the Revolution in 1942.

In life, the Sonoran Dynasty had characterized Carranza as "the most corrupt in the annals of the Mexican government". Toward the end of Álvaro Obregón's presidency (1920–24), his office contacted Carranza's daughter Julia, saying that the she was due a pension because "Venustiano Carranza gave eminent services to the Revolution and to the Nation." She and her brother refused the pension, replying bitterly to his letter that Obregón was responsible for her father's death and no amount of money could compensate for his loss. The Carranzas signed it "Your loyal enemies, Julia, Emilio, Venustiano, and Jesús Carranza."

''The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898-1934''

p. 108, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, USA. Carranza led the broad-based Constitutionalist movement against the Huerta regime, uniting political and armed forces in northern Mexico to the cause of restoring constitutional law in Mexico. Brilliant military leaders served Carranza, most notably Obregón,

online

* Cumberland, Charles E. "'Dr. Atl' and Venustiano Carranza." ''The Americas'' 13.3 (1957): 287-296. * Frank, Lucas N. "Playing with Fire: Woodrow Wilson, Self‐Determination, Democracy, and Revolution in Mexico." ''Historian'' 76.1 (2014): 71-96

online

* Gilderhus, Mark T. "Wilson, Carranza, and the Monroe Doctrine: A Question in Regional Organization." ''Diplomatic History'' 7.2 (1983): 103-11

online

*Gilderhus, Mark T. ''Diplomacy and Revolution: U.S.-Mexican Relations under Wilson and Carranza''. (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1977)

online

* * Hill, Larry D. ''Woodrow Wilson's Executive Agents in Mexico: From the Beginning of His Administration to the Recognition of Venustiano Carranza'' (2 vol Louisiana State University 1971

online

* Hilton, Stanley E. "The Church-State Dispute over Education in Mexico from Carranza to Cárdenas." ''The Americas'' 21.2 (1964): 163-183. * Kahle, Louis G. "Robert Lansing and the Recognition of Venustiano Carranza." ''Hispanic American Historical Review'' 38.3 (1958): 353-372

online

* Katz, Friedrich. ''The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States and the Mexican Revolution''. Chicago:

online

*Richmond, Douglas W. ''Venustiano Carranza's Nationalist Struggle: 1893–1920''. Lincoln:

online

*

Encyclopædia Britannica, Venustiano Carranza

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Carranza, Venustiano 1859 births 1920 deaths 1920 suicides 1920 murders in North America 20th-century Mexican politicians Assassinated heads of government Assassinated Mexican politicians Assassinated heads of state Candidates in the 1917 Mexican presidential election Deaths by firearm in Mexico Governors of Coahuila Male murder victims Mexican people of Basque descent Mexican revolutionaries Military personnel from Coahuila People from Cuatro Ciénegas People murdered in Mexico People of the Mexican Revolution Politicians from Coahuila Porfiriato Presidents of Mexico Second French intervention in Mexico Unsolved murders in Mexico 1920 crimes in Mexico

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza), is one of the 32 states of Mexico.

Coahuila borders the Mexican states of N ...

. When Madero was murdered during the February 1913 counter-revolutionary coup, Carranza drew up the Plan of Guadalupe, a purely political plan to oust Madero's usurper, General Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 22 December 1854 – 13 January 1916) was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero w ...

. As a sitting governor when Madero was overthrown, Carranza held legitimate power and he became the leader of the northern coalition opposed to Huerta. The Constitutionalist faction was victorious and Huerta ousted in July 1914. Carranza did not assume the title of provisional president of Mexico, as called for in his Plan of Guadalupe, since it would have prevented his running for constitutional president once elections were held. His government in this period was in a preconstitutional, extralegal state, to which both his best generals, Álvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

objected.

The factions of the coalition against Huerta fell apart and a bloody civil war of the winners ensued, with Obregón remaining loyal to Carranza and Villa, now allied with peasant leader Emiliano Zapata, breaking with him. The Constitutionalist Army under Obregón defeated Villa in the north, and Zapata and the peasant army of Morelos returned to guerrilla warfare. Carranza's position was secure enough politically and militarily to take power in Mexico City, although Zapata and Pancho Villa remained threats. Carranza consolidated enough power in the capital that he called a constitutional convention in 1916 to revise the 1857 liberal constitution. The Constitutionalist faction had fought to defend it and return Mexico to constitutional rule. With the promulgation of a new revolutionary Mexican Constitution of 1917, he was elected president, serving from 1917 to 1920.

The constitution that the revolutionaries drafted and ratified in 1917 now empowered the Mexican state to embark on significant land reform and recognized labor's rights, and curtail the power of the Catholic Church, but Carranza did not implement major reforms once he was duly elected. Once firmly in power in Mexico, Carranza sought to eliminate his political rivals, having Zapata assassinated in 1919. Carranza won recognition from the United States, but nonetheless took strongly nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

positions.

In the 1920 election, in which he could not succeed himself, Carranza attempted to impose a virtually unknown, civilian politician, Ignacio Bonillas, as president of Mexico. Sonoran revolutionary generals Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a general in the Mexican Revolution and a Sonoran politician, serving as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

The 1924 Calles presidential campaign was the first populist ...

, and Adolfo de la Huerta, who held real power, rose up against Carranza under the Plan of Agua Prieta. Carranza fled Mexico City, along with thousands of his supporters and with gold of the Mexican treasury, aiming to set up his government in Veracruz. Instead he died in an attack by rebels. Although Carranza played a major role in the Revolution, his contributions were not initially acknowledged in Mexico's historical memory, since he was overthrown by rivals. Later on, with a historical narrative that recognizes the various competing factions as members of the "revolutionary family", Carranza's place in Mexican history has been assured.

Early life and education, 1859–1887

Carranza was born in the town of Cuatro Ciénegas, in the state of

Carranza was born in the town of Cuatro Ciénegas, in the state of Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza), is one of the 32 states of Mexico.

Coahuila borders the Mexican states of N ...

, in 1859, to a prosperous cattle-ranching family. His father, Jesús Carranza

Jesús Carranza Neira was a Mexican colonel from Cuatro Ciénegas, Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza) ...

Neira, had been a rancher and mule driver until the time of the Reform War

The Reform War, or War of Reform ( es, Guerra de Reforma), also known as the Three Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Tres Años), was a civil war in Mexico lasting from January 11, 1858 to January 11, 1861, fought between liberals and conservativ ...

(1857–1861), in which he fought against the Indians

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

and on the Liberal side.Krauze, ''Mexico: Biography of Power'', p. 335. During the French intervention in Mexico (1861–1867) that made Mexico into a monarchy, Jesús Carranza continued to support President Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

and joined Mexican defenders against the French, becoming a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

. He was Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec, he was the first indigenous pre ...

's main contact in Coahuila. A strong personal connection existed between the two, with Carranza lending Juárez money while Juárez's republican government was in exile. Following the ouster of the French, Juárez rewarded Carranza with land, which became the basis of his fortune in Coahuila.

Because of his family's wealth, Venustiano, the 11th of 15 children, was able to attend excellent schools in Saltillo and Mexico City. Venustiano studied at the Ateneo Fuente, a famous Liberal school in Saltillo. In 1874, he went to the ''Escuela Nacional Preparatoria

The Escuela Nacional Preparatoria ( en, National Preparatory High School) (ENP), the oldest senior High School system in Mexico, belonging to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), opened its doors on February 1, 1868. It was founded ...

'' (National Preparatory School) in Mexico City, where he had aspirations to be a doctor. Carranza was still there in 1876 when Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

issued the Plan of Tuxtepec, which marked the beginning of Díaz's rebellion against President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. Díaz's slogan was "No Re-election." Lerdo had already served one term as president and Juárez before him was also re-elected president. Díaz's troops defeated Lerdo's, and Díaz and his armies marched into Mexico City in triumph. Díaz created a system of machine politics and pacified the country, remaining in power continuously until 1911. Carranza entered local politics in Coahuila during the Díaz era, after completing his schooling. He married Virginia Salinas in 1882, and the couple had two daughters.

Career

Introduction to politics, 1887–1909

As an educated member of a prominent and well-connected Coahuila family, Carranza entered politics with the means to do so. In 1887, at the age of 28, he became municipal president of Cuatro Ciénegas, where he began making reforms to improve education.Richmond, "Venustiano Carranza", 199 Carranza remained a Liberal who idolized Benito Juárez, against whom Díaz raised a failed rebellion. Carranza grew disillusioned with the increasingly authoritarian character of the rule of Díaz during this period. In 1893, 300 Coahuila ranchers organized an armed resistance to oppose the "re-election" of Porfirio Díaz's supporter José María Garza Galán as Governor of Coahuila. Venustiano Carranza and his brother Emilio participated in this uprising. Díaz quickly dispatched his "man in the north", Bernardo Reyes, to defuse the situation. Venustiano Carranza and his brother, who had now gained power and influence in the area, were granted a personal audience with Reyes in order to explain the justification for the uprising and the ranchers' opposition to Garza Galán. Reyes agreed with Carranza and wrote to Díaz recommending that he withdraw support for Garza Galán. Diaz accepted this request and appointed a different governor, who was acceptable to Bernardo Reyes and to the Carranza family. The revolt forced Díaz to acknowledge the Carranzas' power throughout the state. The events of 1893 allowed Carranza to make connections in some high places, including Bernardo Reyes. After winning a second term as municipal president (1894–1898), Reyes had Carranza "elected" to the legislature. In 1904, Reyes's protégé Miguel Cárdenas, Governor of Coahuila, recommended to Díaz that Carranza would make a good senator. Carranza entered theSenate of Mexico

The Senate of the Republic, ( es, Senado de la República) constitutionally Chamber of Senators of the Honorable Congress of the Union ( es, Cámara de Senadores del H. Congreso de la Unión), is the upper house of Mexico's bicameral Congre ...

later that year. Although Carranza was skeptical of Díaz's advisors known as the Científicos, he supported their policies. As a senator in the national legislature, he inserted language into laws that would limit foreign investors.Richmond, "Venustiano Carranza", 199. As the 1910 presidential election approached, Bernardo Reyes was a contender as a candidate. Díaz initially said in print in the Creelman interview that he would not run for president again, but changed his mind. Reyes had openly presented himself as a powerful candidate, and now Carranza's connection to Reyes resulted in Díaz not backing Carranza for governor of Coahuila. Díaz sent Reyes out of the country, and Carranza forged an expedient connection to Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landowner who challenged Díaz.Knight, "Venustiano Carranza", 572.

Supporter of Francisco Madero, 1909–1911

Carranza followed Francisco Madero's Anti-Re-election Movement of 1910 with interest. After Madero fled to the US and Díaz was re-elected as president, Carranza traveled to Mexico City to join Madero. Madero named Carranza provisional Governor of Coahuila. The Plan of San Luis Potosí, which Madero issued at this time, called for a revolution beginning 20 November 1910. Madero named Carranza commander-in-chief of the Revolution in Coahuila,Nuevo León

Nuevo León () is a state in the northeast region of Mexico. The state was named after the New Kingdom of León, an administrative territory from the Viceroyalty of New Spain, itself was named after the historic Spanish Kingdom of León. With ...

, and Tamaulipas

Tamaulipas (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tamaulipas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tamaulipas), is a state in the northeast region of Mexico; one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal Entiti ...

. Carranza failed to organize an uprising in these states, leading some of Madero's supporters to speculate that Carranza was still loyal to Bernardo Reyes. Following the revolutionaries' led by Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

, achieved decisive victory over the Federal Army at Ciudad Juárez, Carranza travelled to Ciudad Juárez. Madero named Carranza his Minister of War on 3 May 1911, even though Carranza did not contribute much to Madero's rebellion. The revolutionaries were split on how to deal with Porfirio Díaz and Vice President Ramón Corral. Madero favored having Díaz and Corral resign, with Francisco León de la Barra serving as interim president until a new election could be held. Carranza disagreed with Madero. Carranza was a seasoned politician, unlike Madero, and he argued that allowing Díaz and Corral to simply resign would legitimate their rule; an interim government would merely be a prolongation of the dictatorship and would discredit the Revolution. Madero's view prevailed, with the results that Carranza foresaw. Madero's victory did net Carranza power in Coahuila during Madero's presidency (November 1911-February 1913).

Governor of Coahuila, 1911–1913

Carranza returned to Coahuila to serve as governor, shortly holding elections in August 1911, which he won handily. Because of Carranza's support in his opposition to Díaz, Madero gave him free rein over Coahuila. As governor Carranza began a wide-ranging program of reform, including the judiciary, the legal code, and tax laws. He introduced regulations to bring safety in the workplace, to prevent mining accidents, to rein in abusive practices at company stores, to break up commercial monopolies, to combat alcoholism, and to rein in gambling and prostitution. He also made large investments in education, which he saw as the key to societal development. An important step Carranza took was to create an independent state militia, under the control of the governor, which could put down rebellions and ensure a level of state autonomy from the central government. The relationship between Carranza and Madero began deteriorating. Carranza had joined with Madero only when Díaz sent his mentor Reyes out of the country. Madero was suspicious of his loyalty. Carranza had already opposed Madero's signing of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez to have an interim presidency. Once Madero was inaugurated president following the October election, Carranza criticized Madero for being a weak and ineffectual as president. Madero in turn accused Carranza of being spiteful and authoritarian. Carranza believed that there would soon be an uprising against Madero. so he formed alliances with other Liberal governors: Pablo González Garza, Governor of San Luis Potosí; Alberto Fuentes Dávila, Governor of Aguascalientes; and Abraham González, Governor of Chihuahua. Carranza was not surprised in February 1913 when Reyes,Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 22 December 1854 – 13 January 1916) was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero w ...

, and Félix Díaz, Porfirio Díaz's nephew, backed by the U.S. Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, overthrew Madero during '' La decena trágica'' (the Ten Tragic Days) of fighting in the capital. Reyes was killed during the fighting in Mexico City. With his mentor dead, Carranza was not sure of his own next steps. There is evidence that Carranza negotiated with Huerta immediately after the coup, but no agreement was reached.

''Primer Jefe'' of the Constitutionalist Army, 1913–1914

Carranza declared himself in rebellion against the government installed by the coup. Carranza's declaration against Huerta was a decisive stand. He had political legitimacy as a state governor, a modest record of state reform, popular support in his state, and an able politician, forging alliances to create a broad northern coalition against Huerta. It came to be known as the Constitutionalists, taking their name for the defense of the liberal Constitution of 1857. He was both the titular leader of the movement, as well as the actually leader in many circumstances.

In late February 1913, Carranza asked the legislature of Coahuila to declare itself formally in a state of rebellion against Huerta's government. He had built a state militia, funded by levying new taxes on enterprises, it could not withstand the well-armed, substantial force of the Federal Army controlled by General, now President, Huerta. The Coahuila militia suffered defeats at Anhelo, Saltillo, and Monclova, forcing Carranza to flee to Sonora a revolutionary stronghold.Katz, ''The Secret War in Mexico'', 130 Before he left Coahuila, he returned to his hacienda of Guadalupe, where he found a group of young men,

Carranza declared himself in rebellion against the government installed by the coup. Carranza's declaration against Huerta was a decisive stand. He had political legitimacy as a state governor, a modest record of state reform, popular support in his state, and an able politician, forging alliances to create a broad northern coalition against Huerta. It came to be known as the Constitutionalists, taking their name for the defense of the liberal Constitution of 1857. He was both the titular leader of the movement, as well as the actually leader in many circumstances.

In late February 1913, Carranza asked the legislature of Coahuila to declare itself formally in a state of rebellion against Huerta's government. He had built a state militia, funded by levying new taxes on enterprises, it could not withstand the well-armed, substantial force of the Federal Army controlled by General, now President, Huerta. The Coahuila militia suffered defeats at Anhelo, Saltillo, and Monclova, forcing Carranza to flee to Sonora a revolutionary stronghold.Katz, ''The Secret War in Mexico'', 130 Before he left Coahuila, he returned to his hacienda of Guadalupe, where he found a group of young men, Francisco J. Múgica

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Nicknames

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed "Paco (name), Paco". Francis of Assisi, San Francisco de Asís was known as '' ...

, Jacinto B. Treviño

General Jacinto Blas Treviño González (11 September 1883 – 5 November 1971) was a Mexican military officer, noteworthy for his participation in the Mexican Revolution of 1910 to 1921.

Early life

Jacinto B. Treviño was born in Guerrero, C ...

, and Lucio Blanco, who had drawn up a plan

A plan is typically any diagram or list of steps with details of timing and resources, used to achieve an objective to do something. It is commonly understood as a temporal set of intended actions through which one expects to achieve a goal ...

modeled on Madero's Plan of San Luis Potosí. The Plan of Guadalupe disavowed Huerta as well as the legislative and judicial authorities of Huerta's government. The plan named Carranza as ''Primer Jefe'' ("First Chief") of the Constitutional Army. The plan also called for Carranza to become interim president of Mexico, who would then call for a general election, "and will his Authority to whoever may be elected."

Carranza's Plan of Guadalupe made no promises of reform. He thought Madero's mistake had been to formalize promises of social reform in his plan, which went unfulfilled. In Morelos, the peasants who had supported Madero then declared themselves in rebellion against him when as president he did not deliver on land reform. He understood that Madero's plan had brought together disparate elements to oust Díaz, which it had successfully done. Afterwards, peasants were disillusioned as were the ruling classes. For Carranza, a broad, narrow call for restoration of the constitution and ouster of the usurper Huerta made reforms possible. To radicals supporting Carranza, his narrow political plan fell far short of what they were fighting for. Carranza responded to their criticism: "Do you want the war to last for five years? The less resistance there is, the shorter the war will be. The large land owners, the clergy, and the industrialists are stronger than the federal government. We must first defeat the government before we can take on the questions you rightly wish to resolve." Following the collapse of the Federal Army in the summer of 1914, leaving the revolutionaries victorious, Carranza updated the Plan of Guadalupe to promise sweeping reforms to undercut the appeal of more radical revolutionaries, especially Villa.

Venustiano Carranza was not a military man himself, but the Constitutionalist Army of which he was commander in chief had brilliant military leaders, especially Álvaro Obregón, Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (, Orozco rebelled in March 1912, both for Madero's continuing failure to enact land reform and because he felt insufficiently rewarded for his role in bringing the new president to power. At the request of Madero's c ...

, Felipe Ángeles

Felipe Ángeles Ramírez (1868–1919) was a Mexican military officer and revolutionary during the era of the Mexican Revolution. Having risen to the rank of colonel of artillery in the Federal Army of the Porfiriato, Ángeles was promoted to ge ...

, Benjamin G. Hill

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's thir ...

, and Pablo González Garza. Initially, Carranza divided the country into seven operational zones, though his Revolution was really launched in only three: (1) the northeast, under the command of González Garza; (2) the center, under the command of Pánfilo Natera; and (3) the northwest, under the command of Obregón. The forces launched against Huerta in March 1913, initially did not go well. Huerta's troops of the Federal Army marched into Monclova, forcing Carranza to flee to the rebels' stronghold of Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into 72 municipalities; the ...

in northwest Mexico in August 1913. After a rocky start, the Constitutionalist Army under Carranza's command grew remarkably. In March 1914, Carranza was informed of Pancho Villa's victories and of advances made by the forces under González Garza and Obregón. Carranza determined that it was safe to leave Sonora, and traveled to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, on the border with the United States, which served as his capital for the remainder of his struggle with Huerta.

Early adherents to Carranza's cause were Mexican Protestants and American Protestant missionaries and their U.S.-based churches were to play an important role in Carranza's movement. Carranza's brother Jesús Carranza

Jesús Carranza Neira was a Mexican colonel from Cuatro Ciénegas, Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza) ...

was married to the daughter of a Protestant. "Mexican ministers and their congregations joined the forces attempting to oust Huerta", with the majority following Carranza. Although Protestants were a small percentage of the Mexican population, most being Catholic, Protestants served as officers in the Constitutionalist Army. As Carranza's coalition moved toward achieving a victory and Carranza setting up a government, Protestants served in administrative positions. Publications of these U.S.-based churches touted the achievements of their co-religionists, while Mexican Catholics deplored the Protestant presence.

Outside his home bailiwick of Coahuila in exile in Sonora, Carranza had to broaden his movement, which in Coahuila had drawn on state elites. In Sonora, which was more isolated geographically from Mexico City since there was no direct railway line, the revolution had gone at a faster pace than in Coahuila. The region was in many ways autonomous because federal troops could not be quickly dispatched and there were natural resources to draw on for the armed struggle. Carranza met Sonoran revolutionaries who came from middle and working-class backgrounds. He was able to attract to his movement able men not trained as soldiers. These included Álvaro Obregón, who as a widower with small children at the time did not join in Madero's earlier movement; and Obregón's cousin Benjamin G. Hill

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's thir ...

, and Plutarco Elías Calles

Plutarco Elías Calles (25 September 1877 – 19 October 1945) was a general in the Mexican Revolution and a Sonoran politician, serving as President of Mexico from 1924 to 1928.

The 1924 Calles presidential campaign was the first populist ...

í. Others included Pablo González; Manuel Diéguez, who had participated in the Cananea strike; Heriberto Jara, who was a former textile worker who participated in the great Río Blanco strike. Carranza also attracted intellectuals to his movement, especially Luis Cabrera and Pastor Rouaix. Carranza also gained the support of Francisco Villa of Chihuahua, who had played an important role in toppling the Díaz regime.

Pancho Villa commanded the Division of the North and recognized Carranza as commander in chief of the Constitutionalist Army. Villa was a skilled commander, but his tactics throughout the 1913-14 campaign created a number of diplomatic incident {{Refimprove, date=December 2011

An international incident (or diplomatic incident) is a seemingly relatively small or limited action, incident or clash that results in a wider dispute between two or more nation-states. International incidents can ...

s that were a major headache for Carranza in this period. Villa had confiscated the property of Spaniards in Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

*Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mun ...

and had allowed his troops to murder an Englishman, Benton, and a U.S. citizen, Bauch. At one point, Villa arrested Manuel Chao, the Governor of Chihuahua, forcing Carranza to personally travel to Chihuahua to order Villa to release Chao. Villa diverged from Carranza's opposition to the U.S. occupation of Veracruz, which occurred following the arrest of nine U.S. Navy sailors by Federal Army troops over a misunderstanding about fuel supplies. In response to the Tampico Affair, the United States government sent 2,300 Navy personnel to occupy the strategic port of Veracruz, Veracruz

Veracruz (), known officially as Heroica Veracruz, is a major port city and municipal seat for the surrounding municipality of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The city is located along the coast in the central pa ...

. Carranza was an ardent nationalistic credentials and threatened war with the United States. In his spontaneous response to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

, Carranza asked "...that the president withdraw U.S. troops from Mexico and take up its complaints against Huerta with the Constitutionalist government."Carothers to Secretary of State, 22 April 1914, Wilson Papers, Ser. 2, as quoted in Haley, ''The Diplomacy of Taft and Wilson with Mexico, 1910-1917'', 135. The situation became so tense that war seemed imminent. On 22 April 1914, on the initiative of Felix A. Sommerfeld and Sherburne Hopkins, Pancho Villa traveled to the border town of Ciudad Juárez, Carranza's capital of the Constitutionalists, to calm fears along the border and asked President Wilson's emissary George Carothers there to tell "Señor Wilson" that he had no problem with the U.S. occupation of Veracruz. Carothers wrote to Secretary William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

: "As far as he was concerned we could keep Vera Cruz and hold it so tight that not even water could get into Huerta and ...he could not feel any resentment." Whether trying to please the U.S. government or through the diplomatic efforts of Sommerfeld and Carothers, or maybe as a result of both, Villa took a different position than Carranza's stated foreign policy.

The anti-Huerta revolutionary forces of the Constitutionalists commanded by Carranza and Emiliano Zapata's forces in Morelos brought about the defeat of the Federal Army in the summer of 1914. Huerta fled Mexico on 15 July 1914. Minister of War Francisco S.Carbajal had offered Carranza Federal troops to defeat the Zapatistas, but Carranza demanded the dissolution of the Federal Army and their unconditional surrender. He had not fallen into the trap that ensnared Madero, who allowed the continued existence of the Federal Army. The fight against Huerta formally ended on 13 August 1914, when Álvaro Obregón signed a number of treaties in Teoloyucan in which the last of Huerta's forces surrendered to him and recognized the Constitutionalists. On 20 August 1914, Carranza made a triumphal entry into Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley of ...

. Carranza (supported by Obregón) was now the strongest candidate to fill the power vacuum and set himself up as head of the new government. This government successfully printed money and passed laws.

Carranza benefited greatly from U.S. aid as the Huerta regime collapsed. Although the U.S. Ambassador Henry Lane had helped engineer the coup against President Madero in February 1913, in March 1913 President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

was inaugurated. Wilson refused to recognize the Huerta regime. As early as November 1913, U.S. President Wilson began considering lifting the ban on arms sales so that the Constitutionalists could better oppose Huerta. Huerta was proving intransigent to U.S. calls for his resignation and elections to be held. Huerta's government could receive arms shipments from abroad by sea, whereas the Constitutionalists' base in the north meant they were dependent on arms sales across the U.S. border. The U.S. envoy attempted to extract promises from Carranza for the U.S. lifting the ban, but Carranza rebuffed him. Carranza wanted U.S. recognition and arms, but did not want to publicly make promises to the U.S. Carranza sent Luis Cabrera, a trained lawyer fluent in English, to Washington D.C. as a special agent of the Constitutionalist government to try to come to an agreement. Carranza had attracted talented civilians to his movement with Cabrera being most prominent. Like Carranza had been a supporter of Bernardo Reyes when he was poised to run for president in 1910. After the assassination of Madero in February 1913, he joined the Constitutionalist movement and served as Carranza's main civilian adviser. Although not a Protestant himself, Cabrera was sympathetic to Protestants. Cabrera went to New York went lobby for U.S. recognition for the Constitutionalists as the legitimate government of Mexico. He drew upon a network of well-placed Protestants in the effort Cabrera became Carranza's Minister of Finance and drafted his agrarian law, which proved important for the recruitment of peasants to the Constitutionalists' cause. Cabrera already had friends in official Washington, and it was known that although he was for substantive land reform in Mexico, he was committed to payment of debts to foreigners and repayment of forced loans. Cabrera had the difficult task over time to deflect Wilson's attempts to shape the outcome of Mexico's outcome.

The protracted Mexican civil war waged to oust him in 1913-14 was a threat to U.S. investments in Mexico, since confiscating, imposing forced loans, or otherwise stripping resources from foreign enterprises was a key way to fund the revolutionaries' struggles. Carranza's stance was as a sober, skilled and deeply nationalist politician. His political program did not promise any kind of social or economic changes in Mexico seemed to be the best revolutionary leader to back in the struggle, bring it to an end, and restore some semblance of the old order, which had benefited U.S. investors and kept its southern border quiet. The U.S. had taken the port of Veracruz over a over a minor incident involving U.S. Navy sailors. The incident resulted in a level of Mexican unity against the foreign invaders. Carranza took a public, nationalist stance against the U.S. When the Constitutionalist Army wore down the Federal Army and Huerta was forced to go into exile, the U.S. left the munitions and war materiel of their troops in Veracruz along with some that the Huerta regime had bought to the Constitutionalist Army.

Break with Pancho Villa

Tensions between Carranza and Pancho Villa were high throughout 1913-14 over both Governor Chao and the diplomatic incidents that Villa provoked. Before Huerta's Federal Army was defeated in July 1914, Villa defied Carranza's orders and successfully captured Mexico's strategic silver-producing city ofZacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

, a bloody battle with some 6,000 Federal Army casualties. Carranza had attempted to prevent Villa's victory by sidelining him to avoid having to politically pay a price to Villa. Carranza clumsily attempted to lure some over Villa's men away to be commanded by other generals, but those generals reproved Carranza for his authoritarian and jealous ways. Villa's successful capture of the city broke the back of Huerta's regime. On 8 July 1914, Villistas and Carrancistas had signed the Treaty of Torreón

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

, in which they agreed that after Huerta's forces were defeated, 150 generals of the Revolution would meet to determine the political future of the country.

Immediately after the defeat of Huerta, the tensions between the elements of the Constitutionalist forces, particularly between Villa, Obregón, and Carranza came to a head. The two generals were charismatic revolutionary generals, while Carranza was a civilian politician who was reluctant to give either of them political power equal to their battlefield achievements. Villa felt belittled and denigrated by Carranza and Obregón sought to keep the revolutionary coalition intact for as long as possible. Despite their differences, Villa and Obregón were both opposed to Carranza's continuation of a pre-constitutional, extra-legal government, since the Plan of Guadalupe called for Carranza becoming provisional president with elections subsequently held. Had Carranza done so, he would have been ineligible to run for president. Obregón warned Carranza that refusing to become interim president would precipitate a break with Villa, but Carranza took that risk. In two meetings with Villa, Obregón placed himself in extreme danger from assassination, but felt making the effort to keep the revolutionary coalition together worth the risk. Obregón concluded that Villa was dangerous and untrustworthy, and chose to support Carranza when the coalition fell apart. Carranza did not entirely trust Obregón's loyalty, but needed his military support. Carranza feared Villa would beat him to Mexico City, since seizing the capital was a powerful political symbol. In August, Carranza refused to let Villa enter Mexico City with him, and refused to promote Villa to major-general. Villa formally disavowed Carranza on 23 September 1914.

Convention of Aguascalientes, meeting of the revolutionary generals, October 1914

With the ouster of Huerta, the broad coalition to achieve that goal cracked. Constitutionalist factions met to decide the way forward. Although Carranza was characterized as the ''primer jefe'' of the Constitutionalists, in fact, the many military leaders in various regions were semi-autonomous from Carranza and not especially loyal to him. The national coalition that Carranza hoped to forge was a secondary consideration for many fighting for gains at the local level. Having pledged to convene a convention, Carranza sought to control it insofar as he could. He set the date for October 1, 1914 in Mexico City, which his troops had occupied. Carranza offered his resignation to the delegates, who refused the gesture since he had chosen most of them himself. In any case, he expected the meeting to ratify his leadership position. The radicals in Carranza's coalition agreed to the change in venue for the meeting, going to Aguascalientes, northwest of the capital. In the run-up to the convention, both those loyal to Carranza and the increasingly independent Villa were recruiting soldiers, since political gains usually depended on military strength on the ground. Villa welcomed soldiers from the defeated Federal Army into his ranks; Carrancistas were recruiting in Veracruz and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, with signing bonuses. Carranza's forces gained war materiel that Huerta had stored in Tehuantepec. The meeting in Mexico City, which had included some political leaders, went forward on October 1, but another, more important meeting was planned for Aguascalientes, ostensibly on neutral ground, and were to include only military leaders, which resulted in a number of his most articulate generals not attending. Many of those attending the convention sought a middle way between Villa, Zapata, and Carranza, seeing Villa and Zapata too radical and Carranza too conservative. Those seeking the middle ground were Obregón of Sonora,Eulalio Gutiérrez

Eulalio Gutiérrez Ortiz (February 4, 1881 – August 12, 1939) was a general in the Mexican Revolution from state of Coahuila. He is most notable for his election as provisional president of Mexico during the Aguascalientes Convention and le ...

of San Luis Potosí, and Lucio Blanco. They gathered enough support to elect Gutiérrez interim president of Mexico, but for just 20 days. The convention thus demoted Carranza making him subordinate to Gutiérrez; it likewise removed Villa from military command. But Carranza simply ignored the decisions of the convention, and recalled his generals from Aguascalientes.Katz, ''The Secret War in Mexico'', 268.

When it was clear the convention had failed to resolve the issues between revolutionary leaders, the factions prepared to meet in armed combat. Obregón and the Sonorans stayed with Carranza, perhaps making the calculation that they would have a greater voice in his movement than with Villa. Carranza was in a weakened position, since he controlled only limited territory and had fewer troops than Villa and Zapata. He had lost supporters and was forced to abandon the capital for Veracruz state as his stronghold. The territory he held was important, the oil-rich Gulf Coast and Mexico's two main ports. With the outbreak of hostilities between the winners against Huerta, the Revolution entered another major phase.

Carranza's victorious coalition against Villa and Zapata, 1915

The convention at Aguascalientes had rejected Carranza and likewise he rejected them. The government of the convention was structurally weak, and in theory the alliance of Zapata and Villa held more men under arms than Carranza's armies. Right after the convention at Aguascalientes, a Carranza victory looked improbable. He controlled little territory and had a smaller fighting force than Villa and Zapata. Militarily the key was Álvaro Obregón's allegiance to him. Also important was the oil-rich territory he did control on the Gulf Coast and control of the two main ports of Veracruz and Tampico. In November 1914, the tide began turning in Carranza's favor with his negotiations with the U.S. to withdraw from the port of Veracruz, leaving much war materiel behind. Carranza set up his government in Veracruz, while the Conventionalist forces held Mexico City. In late 1914, Carranza began issuing a series of reform decrees, and in particular his "Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe", which laid out the social and economic direction of his government in a way the original plan did not. The Additions included text about restoration of lands to communities and the breakup of large landed estates. This change was important for winning the allegiance of peasants whose main goal during revolutionary warfare was access to land. In September 1914 he had already issued a proclamation attempting to outflank Zapata and the Plan of Ayala, saying that he would legalize agrarian reforms not just in Morelos but throughout the nation. His ally Luis Cabrera then codified this into the agrarian law that Carranza issued in January 1915, creating communally held village lands now called '' ejidos''. He saw these as "reparations for past injustices. One Conventionist in February 1915 lamented that Carranza was moving quickly on this key problem. Carranza "understood that he could acquire some prestige only by solving the land issue: he thus occupied himself more than we the agrarians did with the resolution of the problem." Although Carranza directly appealed to peasant interests, he also shored up support of his fellow landed estate owners (''hacendados''), whose interests were directly counter to peasants'. Quietly he told ''hacendados'' that confiscated estates would be returned to their owners. Carranza had allowed, or could not prevent, such confiscations in dire military circumstances, but Carranza had not confirmed the confiscations as permanent. For estate owners, which included many foreign interests, the quiet promise of the return of their land drew many in the north to support Carranza. Some even raised militias of their estate workers to fight Villas forces. HistorianFriedrich Katz

Friedrich Katz (13 June 1927 – 16 October 2010) was an Austrian-born anthropologist and historian who specialized in 19th and 20th century history of Latin America, particularly, in the Mexican Revolution.

"He was arguably Mexico's most widel ...

has postulated that peasants flocked to Carranza because his well-publicized and widely distributed land law was a national policy, not one confined to Morelos (as with Zapata) or parts of the north (as with Villa), leading to the "first political mobilization outside their territories."Katz, ''The Secret War in Mexico'', 272. Carrancistas enforced land reform in Yucatán henequen

Henequen (''Agave fourcroydes'') is a species of flowering plant in the family Asparagaceae, native to southern Mexico and Guatemala. It is reportedly naturalized in Italy, the Canary Islands, Costa Rica, Cuba, Hispaniola, the Cayman Islands and ...

plantations, which were worked by debt peons. The peasants had not mobilized in revolutionary struggle. Carrancista general Salvador Alvarado abolished debt peons from the plantations. The plantations were not broken up in land reform, but the henequen was bought by a state-owned corporation, which took a portion of the profits for itself, helping to fund the Carranza movement's financial position.

José Clemente Orozco

José Clemente Orozco (November 23, 1883 – September 7, 1949) was a Mexican caricaturist and painter, who specialized in political murals that established the Mexican Mural Renaissance together with murals by Diego Rivera, David Alfaro ...

.Krauze, ''Mexico: Biography of Power'', 354. Urban workers saw their interests as completely opposed to those of the peasantry. They wanted a ready, cheap food supply, not a peasantry that subsistence-farmed small plots of land for their own needs. Culturally the urban working class saw the Zapatatistas as too religious and the Villistas as too radical and barbarian.

The real victory against Villa came with Obregón's defeat of Villa in two decisive battles at Celaya. Obregón "proved to be the most important military leader of the Mexican Revolution." Villa's frontal cavalry charges against Obregón's modern use of machine guns and barbed wire meant heavy casualties for Villa's larger force and few for Obregón's. Those defeats were the end of Villa's effective fighting force and Carranza's renewed standing as leader. Villa's military defeat meant the desertion of many of his followers to Carranza's side. Obregón's victory brought him fame, but for the moment he remained loyal to Carranza. He became Carranza's Minister of War.

Another important Carrancista general was Pablo González, who was deployed against Zapata in Morelos. Although his victories were not as spectacular as Obregón's against Villa, González was able to disperse the Zapatista armies into guerrilla bands. The United States recognized Carranza as President of Mexico in October 1915, and by the end of the year Villa was on the run.

Head of the Pre-constitutional Government, 1915–1917

With the defeat of the ''División del Norte'' in the Battles of Celaya in April 1915 and the army of the Zapatistas, by mid-1915, Carranza was President of Mexico as head of what he termed a "Pre-constitutional Government". This would last until the ratification of the Constitution of 1917 and elections that made Carranza the constitutional president. Carranza formally took charge of the executive branch on 1 May 1915. Both Villa and Zapata remained threats the Carranza's regime, even though neither faction could raise a significant number of troops. The Zapatistas never laid down their arms, and continued with guerrilla warfare in Morelos, directly south of Mexico City. Villa deliberately provoked the U.S. in his raid onColumbus, New Mexico

Columbus is a village in Luna County, New Mexico, United States, about north of the Mexican border. It is considered a place of historical interest, as the scene of a 1916 attack by Mexican revolutionary leader Francisco "Pancho" Villa that ca ...

in 1916, leading to a U.S. Army incursion into Mexico in an unsuccessful attempt to capture him.

To outflank Villa's appeal to the peasantry, on 12 December 1914, Carranza issued "Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe", which laid out an ambitious reform program, including Laws of Reform, in conscious imitation of Benito Juárez's Laws of Reform.

Reforms were to be carried through on many issues, but in practice, Carranza implemented reforms in targeted ways.

* Judicial reform - Carranza introduced important reforms to ensure an independent judiciary for Mexico.

* Labor - in February 1915, the Constitutionalist Army signed an agreement with the Casa del Obrero Mundial ("House of the World Worker"), the labor union with anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

connections which had been established during Madero's presidency. As a result of this agreement, six Red Battalions of workers were formed to fight alongside the Constitutionalist Army against Villa and Zapata.

:After the defeats of Villa and Zapata, between Carranza and radical organized labor soured. He dissolved the Red Battalions in January 1916, since the fights against Villa and Zapata were over and the augmented troops of workers no longer needed by Constitutionalist forces. Also likely a factor was the potential for these armed workers to turn their guns against the Constitutionalists. The wages paid to the Battalion members were paid in scrip, which was worth little in purchasing power as inflation soared and jobs were few. The Casa del Obrero Mundial continued recruiting and they began staging a series of strikes against Carranza's government and businesses, such as o textile factories and the British oil interests. Other workers went on strike, including teachers, bakery workers, carpenters, miners in various parts of Mexico, often owned by foreign interests. Workers found success in boosting their wages and achieving better working conditions. The rhetoric of the Casa became more militant and as the number of affiliated workers increased to 100,000-150,000, Carranza worried about the survival of capitalism against labor's demands. "The anachosyndicalist Casa leaders demanded workers' control of production, wages, and prices." Throughout 1916, Carranza opposed workers who tried to exercise their right to strike. Carranza used the army against striking workers. The Casa staged a general strike in Mexico City and its environs in May 1916. The strike cut electrical services to the capital and large numbers of workers rallied in Alameda Park, in central Mexico City. Obregón's cousin, General Benjamin Hill negotiated with the workers, and the immediate threat was averted. Although labor counted the strike as a win, it gave the opportunity for opponents of anarchosyndicalism to ally with Carranza's increasing consolidation of power. The Casa staged a second general strike in July 1916, which Carranza's forces suppressed instead of negotiating with them. In August 1916, the ''Casa del Obrero Mundial'' was forcibly disbanded by the police, and an 1862 law was reinstated that made striking a capital offense. Carranza believed that the workers had been "denykng the sacred recognition of the fatherland 'patria''... of the principle of every system of government." Historian John Mason Hart writes that "The Constitutionalist army, working in concert with the foreign and wealthiest owners and managers of private enterprise broke the Casa. In so doing, they defeated the working-class revolution and destroyed the independence of the industrial and urban labor movement."

* Land reform. Although Carranza promulgated an agrarian law that might have led to land reform in Mexico, the situation on the ground was complicated. Various warring factions had confiscated landed estates. Confiscated properties (''bienes intervenidos'') had initially held by revolutionary factions, including the defeated Villa, with the generals making decisions about their subsequent tenure. Once Carranza consolidated his position in mid-1915, he removed jurisdiction over these properties from the revolutionary generals and established the Administration of Confiscated Properties (''Administración de bienes intervenidos''), making his regime the sole arbiter of their disposal. One effect of this move was to produce a stream of revenue for his government, but more importantly, it meant that estate owners had to petition Carranza for the return of their properties rather than local revolutionary officials. Politically it was a useful move for Carranza since by returning lands to their former owners, it bought their loyalty to the new Carranza regime. Carranza was himself a hacienda owner and in sympathy with them as a group rather than radicals such as Villa and Zapata who sought comprehensive land reform. Following the end of military actions of armies, Carranza returned many estates to their former owners, such as Porfirio Díaz's former cabinet minister José Ives Limantour

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

and head of the Científicos. Carranza did not return the haciendas of Carranza's political enemies, such as José María Maytorena

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernac ...

of Sonora, who had aided Villa.

* Struggle against foreign companies for natural resources - under the presidency of Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori ( or ; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915), known as Porfirio Díaz, was a Mexican general and politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico, a total of 31 years, from 28 November 1876 to 6 Decem ...

, foreign mining and oil companies (chiefly United States companies) had received generous concessions from the government in order to develop natural resources. On 7 January 1915, Carranza issued a decree declaring his intention to return the wealth of oil and coal to the people of Mexico. The two largest oil companies exploiting Mexico's natural resources were the Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company, an English company led by Lord Cowdray

Viscount Cowdray, of Cowdray in the County of Sussex, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1917 for the industrialist Weetman Pearson, 1st Baron Cowdray, head of the Pearson conglomerate. He had already been create ...

and operating mainly in the region of Poza Rica, Veracruz

Poza Rica (), formally: Poza Rica de Hidalgo is a city and its surrounding municipality in the Mexican state of Veracruz. Its name means "rich well/pond". It is often thought that the name came to be because it was a place known for its abundance ...

and Papantla, Veracruz; and Mexican Petroleum, an American company led by Edward L. Doheny and operating in the region of Tampico, Tamaulipas. Carranza was constrained in his actions because the region of '' La Huasteca'' where they operated was under the control of General Manuel Peláez Manuel Peláez Gorrochotegui (1885–1959) Mexico, Mexican military officer, noteworthy for his participation in the Mexican Revolution of 1910 to 1920.

Manuel Peláez was born in 1885 in the Huasteca region of the state of Veracruz, in the co ...

, who protected the oil companies' interests in exchange for protection money from the oil companies. In terms of mining, Carranza implemented the Calvo Doctrine. He raised taxes on the mining companies, and removed the right of diplomatic recourse for mining companies, declaring their actions subject to the Mexican courts. (Both policies were opposed by the United States and delayed several times at the request of United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's ...

Robert Lansing.)

Constitutional Convention of Querétaro, 1916–1917

Carranza convoked a Constitutional Convention in September 1916, to be held inQuerétaro

Querétaro (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Querétaro ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Querétaro, links=no; Otomi: ''Hyodi Ndämxei''), is one of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities. Its capi ...

. He declared that the liberal 1857 Constitution of Mexico

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1857), often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Cong ...

would be respected, though purged of some of its shortcomings.

When the Constitutional Convention met in December 1916, it contained only 85 conservatives and centrists close to Carranza's brand of liberalism, a group known as the ''bloque renovador'' ("renewal faction"). Against them were 132 more radical delegates who insisted that land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultur ...

be embodied in the new constitution. These radical delegates were particularly inspired by the thought of Andrés Molina Enríquez, in particular, his 1909 book ''Los Grandes Problemas Nacionales'' (English: "The Great National Problems"). Molina Enríquez, though not a delegate to the Convention, was a close advisor to the committee that drafted Article 27 of the constitution: it declared that private property had been created by the Nation and that the Nation had the right to regulate private property to ensure that communities that had "none or not enough land and water" could take them from ''latifundios

A ''latifundium'' ( Latin: ''latus'', "spacious" and ''fundus'', "farm, estate") is a very extensive parcel of privately owned land. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, ...

'' and ''hacienda

An ''hacienda'' ( or ; or ) is an estate (or '' finca''), similar to a Roman '' latifundium'', in Spain and the former Spanish Empire. With origins in Andalusia, ''haciendas'' were variously plantations (perhaps including animals or orchard ...

s''. Article 27 went beyond the Calvo Doctrine, declaring that only native-born or native Mexicans could have property rights in Mexico. It said that although the government might grant rights to foreigners, these rights were always provisional and could not be appealed to foreign governments.

The radicals also exceeded Carranza's program on labor relations. In February 1917, they drafted Article 123 of the Constitution, which established an eight-hour work day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16 ...

, abolished child labor, contained provisions to protect female and adolescent workers, required holidays, provided a reasonable salary to be paid in cash and profit-sharing, established boards of arbitration, and provided for compensation in case of dismissal.

The radicals also established more far-reaching reform of the relationship of church and state than that favored by Carranza. Articles 3 and 130 130 may refer to:

*130 (number)

*AD 130

Year 130 ( CXXX) was a common year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Catullinus and Aper (or, l ...

were strongly anticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

: the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico was denied recognition as a legal entity; priests were denied various rights and subject to public registration; religious education was forbidden; public religious ritual outside of the churches was banned; and all churches were nationalized as the property of the nation.

In short, although Carranza had been the most ardent proponent of constitutionalism and headed the Constitutionalist Army, the 1917 Constitution of Mexico

The Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States ( es, Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the current constitution of Mexico. It was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in th ...

was more radical than the liberal constitution that Carranza had envisioned. The Carrancistas gained some important victories in the Constitutional Convention: the power of the executive was enhanced and the power of the legislature

A legislature is an deliberative assembly, assembly with the authority to make laws for a Polity, political entity such as a Sovereign state, country or city. They are often contrasted with the Executive (government), executive and Judiciary, ...

was diminished. The post of Vice-President was eliminated. Judges were given life tenure to promote judicial independence.

Constitutional President of Mexico, 1917–1920

The new constitution was proclaimed on 5 February 1917. Carranza had no strong opposition to his election as president. In May 1917, Carranza became the constitutional

The new constitution was proclaimed on 5 February 1917. Carranza had no strong opposition to his election as president. In May 1917, Carranza became the constitutional President of Mexico

The president of Mexico ( es, link=no, Presidente de México), officially the president of the United Mexican States ( es, link=no, Presidente de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos), is the head of state and head of government of Mexico. Under the C ...

.

Carranza deliberately achieved little change while in office. Those who wanted a new, revolutionary Mexico after the fighting stopped were disappointed. Mexico was in desperate stress in 1917. The fighting had decimated the economy, destroying the nation's food supply, and the social disruption resulted in widespread disease.

Carranza also faced many armed, political enemies: Emiliano Zapata continued his rebellion in the mountains of Morelos; Félix Díaz, Porfirio Díaz's nephew, had returned to Mexico in May 1916 and organized an army that he called the ''Ejército Reorganizador Nacional'' (National Reorganizer Army), which remained active in Veracruz; the former Porfirians Guillermo Meixueiro

Guillermo () is the Spanish form of the male given name William. The name is also commonly shortened to 'Guille' or, in Latin America, to nickname 'Memo'. People