Valyrian Steel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Damascus steel was the forged

Damascus steel was the forged

Identification of crucible "Damascus" steel based on metallurgical structures is difficult, as crucible steel cannot be reliably distinguished from other types of steel by just one criterion, so the following distinguishing characteristics of crucible steel must be taken into consideration:

* The crucible steel was liquid, leading to a relatively homogeneous steel content with virtually no

Identification of crucible "Damascus" steel based on metallurgical structures is difficult, as crucible steel cannot be reliably distinguished from other types of steel by just one criterion, so the following distinguishing characteristics of crucible steel must be taken into consideration:

* The crucible steel was liquid, leading to a relatively homogeneous steel content with virtually no  Damascus blades were first manufactured in the

Damascus blades were first manufactured in the

Since the well-known technique of

Since the well-known technique of

"Damascene Technique in Metal Working"

* *

John Verhoeven: Mystery of Damascus Steel Swords Unveiled

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Damascus Steel Steels Steelmaking History of Damascus Metalworking Lost inventions Arab inventions

steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

of the blades of sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

s smithed in the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

from ingot

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of sh ...

s of Wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon st ...

either imported from Southern India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the States and union territories of India, Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and T ...

or made in production centres in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, or Khorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

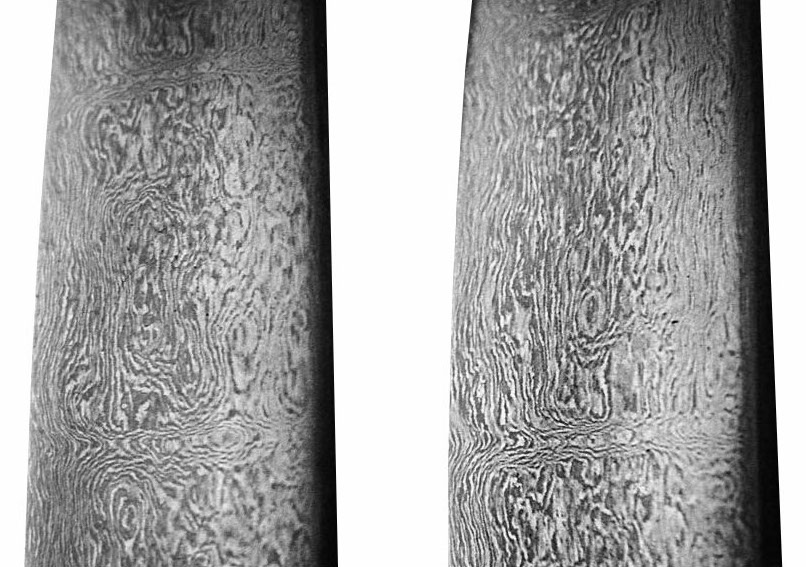

. These swords are characterized by distinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water, sometimes in a "ladder" or "rose" pattern. Such blades were reputed to be tough, resistant to shattering, and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.

Wootz

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon st ...

(Indian), Pulad (Persian), Fuladh (Arabic), Bulat (Russian) and Bintie Bīntiě () was a type of refined iron, which was known for its hardness. It was often used in the making of Chinese weapons. Bintie was an important article of income in medieval Yuan China as technological advances from the preceding Song dynasty ...

(Chinese) are all names for historical ultra-high carbon crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other flux (metallurgy), fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using char ...

typified by carbide segregation. "Wootz" is an erroneous transliteration of "utsa" or "fountain" in Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

, however since 1794 it has been the primary word used to refer to historical hypereutectoid crucible steel.

History

Origins

The origin of the name "Damascus Steel" is contentious: the Islamic scholarsal-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

(full name Abu Ya'qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi, circa 800 CE – 873 CE) and al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

(full name Abu al-Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni, circa 973 CE – 1048 CE) both wrote about swords and steel made for swords, based on their surface appearance, geographical location of production or forging, or the name of the smith, and each mentions "damascene" or "damascus" swords to some extent.

Drawing from al-Kindi and al-Biruni, there are three potential sources for the term "Damascus" in the context of steel:

# The word "damas" is the root word for "watered" in Arabic with "water" being "ma" in Arabic and Damascus blades are often described as exhibiting a water-pattern on their surface, and are often referred to as "watered steel" in multiple languages.

# Al-Kindi called swords produced and forged in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

as Damascene but it is worth noting that these swords were not described as having a pattern in the steel.

# Al-Biruni mentions a sword-smith called Damasqui who made swords of crucible steel.

The most common explanation is that steel is named after Damascus, the capital city of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and one of the largest cities in the ancient Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. It may either refer to swords made or sold in Damascus directly, or it may just refer to the aspect of the typical patterns, by comparison with Damask

Damask (; ar, دمشق) is a reversible patterned fabric of silk, wool, linen, cotton, or synthetic fibers, with a pattern formed by weaving. Damasks are woven with one warp yarn and one weft yarn, usually with the pattern in warp-faced satin ...

fabrics (also named for Damascus), or it may indeed stem from the root word of "damas".

Identification of crucible "Damascus" steel based on metallurgical structures is difficult, as crucible steel cannot be reliably distinguished from other types of steel by just one criterion, so the following distinguishing characteristics of crucible steel must be taken into consideration:

* The crucible steel was liquid, leading to a relatively homogeneous steel content with virtually no

Identification of crucible "Damascus" steel based on metallurgical structures is difficult, as crucible steel cannot be reliably distinguished from other types of steel by just one criterion, so the following distinguishing characteristics of crucible steel must be taken into consideration:

* The crucible steel was liquid, leading to a relatively homogeneous steel content with virtually no slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-prod ...

* The formation of dendrites

Dendrites (from Greek δένδρον ''déndron'', "tree"), also dendrons, are branched protoplasmic extensions of a nerve cell that propagate the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or soma, of the n ...

is a typical characteristic

* The segregation of elements into dendritic and interdendritic regions throughout the sample

By these definitions, modern recreations of crucible steel are consistent with historic examples.

The reputation and history of Damascus steel has given rise to many legends, such as the ability to cut through a rifle barrel or to cut a hair falling across the blade, though the accuracy of these legends is not reflected by the extant examples of patterned crucible steel swords which are often tempered in such a way as to retain a bend after being flexed past their elastic limit

In materials science and engineering, the yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning of plastic behavior. Below the yield point, a material will deform elastically and wi ...

. A research team in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

published a report in 2006 revealing nanowires

A nanowire is a nanostructure in the form of a wire with the diameter of the order of a nanometre (10−9 metres). More generally, nanowires can be defined as structures that have a thickness or diameter constrained to tens of nanometers or less ...

and carbon nanotubes

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon nan ...

in a blade forged from Damascus steel,

* although John Verhoeven of Iowa State University in Ames, suggests the research team which reported nanowires in crucible steel was seeing cementite

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, brit ...

, which can itself exist as rods, so there might not be any carbon nanotubes in the rod-like structure. Although many types of modern steel outperform ancient Damascus alloys, chemical reactions in the production process made the blades extraordinary for their time, as Damascus steel was superplastic

In materials science, superplasticity is a state in which solid crystalline material is deformed well beyond its usual breaking point, usually over about 600% during tensile deformation. Such a state is usually achieved at high homologous tempe ...

and very hard at the same time. During the smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ch ...

process to obtain Wootz steel ingots, woody biomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bi ...

and leaves are known to have been used as carburizing

Carburising, carburizing (chiefly American English), or carburisation is a heat treatment process in which iron or steel absorbs carbon while the metal is heated in the presence of a carbon-bearing material, such as charcoal or carbon monoxide. ...

additives along with certain specific types of iron rich in microalloying elements. These ingots would then be further forged and worked into Damascus steel blades. Research now shows that carbon nanotubes can be derived from plant fibers, suggesting how the nanotubes were formed in the steel. Some experts expect to discover such nanotubes in more relics as they are analyzed more closely. Wootz was also mentioned to have been made out of a co-fusion process using "shaburqan " (hard steel, likely white cast iron) and "narmahan" (soft steel) by Biruni, both of which were forms of either high and low carbon bloomery iron, or low carbon bloom with cast iron. In such a crucible recipe, no added plant material is necessary to provide the required carbon content, and as such any nanowires of cementite or carbon nanotubes would not have been the result of plant fibres.  Damascus blades were first manufactured in the

Damascus blades were first manufactured in the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

from ingot

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of sh ...

s of wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon st ...

that were imported from Southern India

South India, also known as Dakshina Bharata or Peninsular India, consists of the peninsular southern part of India. It encompasses the States and union territories of India, Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and T ...

(present day Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a States and union territories of India, state in southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of India ...

and Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South ...

). The Arabs introduced the wootz steel to Damascus, where a weapons industry thrived. From the 3rd century to the 17th century, steel ingots were being shipped to the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

from South India. There was also domestic production of crucible steel outside of India, including Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

(Turkmenistan) and Chāhak, Iran.

Loss of the technique

Many claim that modern attempts to duplicate the metal have not been entirely successful due to differences in raw materials and manufacturing techniques. However, several individuals in modern times have successfully produced pattern forming hypereutectoid crucible steel with visible carbide banding on the surface, consistent with original Damascus Steel. Production of these patterned swords gradually declined, ceasing by around 1900, with the last account being from 1903 in Sri Lanka documented byCoomaraswamy

Kumaraswamy or Coomaraswamy or Kumarasamy ( ta, குமாரசுவாமி; kn, ಕುಮಾರಸ್ವಾಮಿ) is a South Indian male given name. Due to the South Indian tradition of using patronymic surnames it may also be a surname ...

. Some gunsmiths during the 18th and 19th century used the term "damascus steel" to describe their pattern-welded gun barrels, but they did not use crucible steel. Several modern theories have ventured to explain this decline, including the breakdown of trade routes to supply the needed metals, the lack of trace impurities in the metals, the possible loss of knowledge on the crafting techniques through secrecy and lack of transmission, suppression of the industry in India by the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

, or a combination of all the above.

In addition to being made into blades in India (particularly Golconda) and Sri Lanka, wootz

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon st ...

/ ukku was imported as ingots to various production centers, including Khorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

, and Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

, where the steel was used to produce blades, as well as across the Middle East. Al Kindi states that crucible steel was also made in Khorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

known as Muharrar, in addition to steel that was imported. In Damascus, where many of these swords were sold, there is no evidence of local production of crucible steel, though there is evidence of imported steel being forged into swords in Damascus. Due to the distance of trade for this steel, a sufficiently lengthy disruption of the trade routes could have ended the production of Damascus steel and eventually led to the loss of the technique. In addition, the need for key trace impurities of carbide formers such as tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isolat ...

, vanadium

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( pas ...

or manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

within the materials needed for the production of the steel may be absent if this material was acquired from different production regions or smelted from ores lacking these key trace elements. The technique for controlled thermal cycling after the initial forging at a specific temperature could also have been lost, thereby preventing the final damask pattern in the steel from occurring. The disruption of mining and steel manufacture by the British Raj in the form of production taxes and export bans may have also contributed to a loss of knowledge of key ore sources or key techniques.

The discovery of carbon nanotube

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon na ...

s in the Damascus steel's composition supports the hypothesis that wootz production was halted due to a loss of ore sources or technical knowledge, since the precipitation of carbon nanotubes probably resulted from a specific process that may be difficult to replicate should the production technique or raw materials used be significantly altered. The claim that carbon nanowires were found has not been confirmed by further studies, and there is contention among academics including John Verhoeven about whether the nanowires observed are actually stretched rafts or rods formed out of cementite spheroids.

Reproduction

Recreating Damascus steel has been attempted by archaeologists usingexperimental archaeology

Experimental archaeology (also called experiment archaeology) is a field of study which attempts to generate and test archaeological hypotheses, usually by replicating or approximating the feasibility of ancient cultures performing various tasks ...

. Many have attempted to discover or reverse-engineer

Reverse engineering (also known as backwards engineering or back engineering) is a process or method through which one attempts to understand through deductive reasoning how a previously made device, process, system, or piece of software accompl ...

the process by which it was made.

Moran: billet welding

Since the well-known technique of

Since the well-known technique of pattern welding

Pattern welding is the practice in sword and knife making of forming a blade of several metal pieces of differing composition that are forge welding, forge-welded together and twisted and manipulated to form a pattern. Often mistakenly called Dam ...

—the forge-welding of a blade from several differing pieces—produced surface patterns similar to those found on Damascus blades, some modern blacksmiths were erroneously led to believe that the original Damascus blades were made using this technique. However today, the difference between wootz steel and pattern welding is fully documented and well understood. Pattern-welded steel has been referred to as "Damascus steel" since 1973 when Bladesmith

Bladesmithing is the art of making knives, swords, daggers and other blades using a forge, hammer, anvil, and other smithing tools. Bladesmiths employ a variety of metalworking techniques similar to those used by blacksmiths, as well as woodworkin ...

William F. Moran unveiled his "Damascus knives" at the Knifemakers' Guild The Knifemakers' Guild is an American organization, based in Richfield, Utah, made up of knifemakers to promote custom knives, encourage ethical business practices, assist with technical aspects of knife making, and to sponsor knife shows. The Guil ...

Show.

This "Modern Damascus" is made from several types of steel and iron slices welded

Welding is a fabrication process that joins materials, usually metals or thermoplastics, by using high heat to melt the parts together and allowing them to cool, causing fusion. Welding is distinct from lower temperature techniques such as braz ...

together to form a billet

A billet is a living-quarters to which a soldier is assigned to sleep. Historically, a billet was a private dwelling that was required to accept the soldier.

Soldiers are generally billeted in barracks or garrisons when not on combat duty, alth ...

, and currently, the term "Damascus" (although technically incorrect) is widely accepted to describe modern pattern-welded steel blades in the trade. The patterns vary depending on how the smith works the billet. The billet is drawn out and folded until the desired number of layers are formed. To attain a Master Smith rating with the American Bladesmith Society The American Bladesmith Society, or ABS, is a non-profit organization composed of knifemakers whose primary function is to promote the techniques of forging steel blades. The ABS was founded by knifemaker William F. Moran, who came up with the con ...

that Moran founded, the smith must forge a Damascus blade with a minimum of 300 layers.

Verhoeven and Pendray: crucible

J. D. Verhoeven and A. H. Pendray published an article on their attempts to reproduce the elemental, structural, and visual characteristics of Damascus steel. They started with a cake of steel that matched the properties of the originalwootz

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon st ...

steel from India, which also matched a number of original Damascus swords that Verhoeven and Pendray had access to. The wootz was in a soft, annealed state, with a grain structure and beads of pure iron carbide

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in fro ...

in cementite spheroids, which resulted from its hypereutectoid state. Verhoeven and Pendray had already determined that the grains on the surface of the steel were grains of iron carbide—their goal was to reproduce the iron carbide patterns they saw in the Damascus blades from the grains in the wootz.

Although such material could be worked at low temperatures to produce the striated Damascene pattern of intermixed ferrite/pearlite

Pearlite is a two-phased, lamellar (or layered) structure composed of alternating layers of ferrite (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. During slow cooling of an iron-carbon alloy, pearlite forms ...

and cementite

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, brit ...

spheroid bands in a manner identical to pattern-welded Damascus steel, any heat treatment sufficient to dissolve the carbides was thought to permanently destroy the pattern. However, Verhoeven and Pendray discovered that in samples of true Damascus steel, the Damascene pattern could be recovered by thermally cycling and thermally manipulating the steel at a moderate temperature. They found that certain carbide forming elements, one of which was vanadium, did not disperse until the steel reached higher temperatures than those needed to dissolve the carbides. Therefore, a high heat treatment could remove the visual evidence of patterning associated with carbides but did not remove the underlying patterning of the carbide forming elements; a subsequent lower-temperature heat treatment, at a temperature at which the carbides were again stable, could recover the structure by the binding of carbon by those elements and causing the segregation of cementite spheroids to those locations. Thermal cycling after forging allows for the aggregation of carbon onto these carbide formers, as carbon migrates much more rapidly than the carbide formers. Progressive thermal cycling leads to the coarsening of the cementite spheroids via Ostwald ripening

Ostwald ripening is a phenomenon observed in solid solutions or liquid sols that describes the change of an inhomogeneous structure over time, i.e., small crystals or sol particles dissolve, and redeposit onto larger crystals or sol particles ...

.

Anosov, Wadsworth and Sherby: bulat

In Russia, chronicles record the use of a material known asbulat steel

Bulat is a type of steel alloy known in Russia from medieval times; it was regularly mentioned in Russian legends as the material of choice for cold steel. The name ''булат'' is a Russian transliteration of the Persian word ''fulad'', meani ...

to make highly valued weapons, including swords, knives, and axes. Tsar Michael of Russia

Michael I (Russian: Михаил Фёдорович Романов, ''Mikhaíl Fyódorovich Románov'') () became the first Russian tsar of the House of Romanov after the Zemskiy Sobor of 1613 elected him to rule the Tsardom of Russia.

He w ...

reportedly had a bulat helmet made for him in 1621. The exact origin or the manufacturing process of the bulat is unknown, but it was likely imported to Russia via Persia and Turkestan, and it was similar and possibly the same as Damascus steel. Pavel Petrovich Anosov made several attempts to reproduce the process in the mid-19th century. Wadsworth and Sherby also researched the reproduction of bulat steel and published their results in 1980.

Additional research

A team of researchers based at theTechnical University of Dresden

TU Dresden (for german: Technische Universität Dresden, abbreviated as TUD and often wrongly translated as "Dresden University of Technology") is a public research university, the largest institute of higher education in the city of Dresden, th ...

that used x-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

s and electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

to examine Damascus steel discovered the presence of cementite

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, brit ...

nanowires

A nanowire is a nanostructure in the form of a wire with the diameter of the order of a nanometre (10−9 metres). More generally, nanowires can be defined as structures that have a thickness or diameter constrained to tens of nanometers or less ...

and carbon nanotube

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon na ...

s. Peter Paufler, a member of the Dresden team, says that these nanostructures are a result of the forging process.

Sanderson proposes that the process of forging and annealing accounts for the nano-scale structures.

In gunmaking

Prior to the early 20th century, all shotgun barrels were forged by heating narrow strips of iron and steel and shaping them around amandrel

A mandrel, mandril, or arbor is a gently tapered cylinder against which material can be forged or shaped (e.g., a ring mandrel - also called a triblet - used by jewelers to increase the diameter of a wedding ring), or a flanged or tapered or ...

. This process was referred to as "laminating" or "Damascus". These types of barrels earned a reputation for weakness and were never meant to be used with modern smokeless powder, or any kind of moderately powerful explosive. Because of the resemblance to Damascus steel, higher-end barrels were made by Belgian and British gun makers. These barrels are proof marked and meant to be used with light pressure loads. Current gun manufacturers make slide assemblies and small parts such as triggers and safeties for Colt M1911

The M1911 (Colt 1911 or Colt Government) is a single-action, recoil-operated, semi-automatic pistol chambered for the .45 ACP cartridge (firearms), cartridge. The pistol's formal U.S. military designation as of 1940 was ''Automatic Pistol, Calibe ...

pistols from powdered Swedish steel resulting in a swirling two-toned effect; these parts are often referred to as "Stainless Damascus".

Cultural references

Theblade

A blade is the portion of a tool, weapon, or machine with an edge that is designed to puncture, chop, slice or scrape surfaces or materials. Blades are typically made from materials that are harder than those they are to be used on. Historic ...

that Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The ...

used to kill Grendel's mother

Grendel's mother ( ang, Grendles mōdor) is one of three antagonists in the anonymous Old English poem ''Beowulf'' (c. 700-1000 AD), the other two being Grendel and the dragon. Each antagonist reflects different negative aspects of both the hero ...

in the story ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The ...

'' was described in some Modern English translations as "damascened".

The exceptionally strong fictional Valyrian steel mentioned in George R. R. Martin's book series ''A Song of Ice and Fire

''A Song of Ice and Fire'' is a series of epic fantasy novels by the American novelist and screenwriter George R. R. Martin. He began the first volume of the series, ''A Game of Thrones'', in 1991, and it was published in 1996. Martin, who init ...

'', as well as its television adaptation ''Game of Thrones

''Game of Thrones'' is an American fantasy drama television series created by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss for HBO. It is an adaptation of ''A Song of Ice and Fire'', a series of fantasy novels by George R. R. Martin, the first ...

'', appears to have been inspired by Damascus steel, but with a magic twist. Just like Damascus/Wootz

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon st ...

steel, Valyrian steel also seems to be a lost art from an ancient civilization. Unlike Damascus steel, however, Valyrian steel blades require no maintenance and cannot be damaged through normal combat.

Damascus steel is also a special finish for the SG 553, along with many knives in '' Counter Strike: Global Offensive''.

In ''Call of Duty: Modern Warfare'' (2019) and '' Call of Duty: Mobile'', iridescent blue and red Damascus steel weapon camouflage is available for players who have unlocked all other camouflages for every base weapon in the game.

See also

*Toledo steel

Toledo steel, historically known for being unusually hard, is from Toledo, Spain, which has been a traditional sword-making, metal-working center since about the Roman period, and came to the attention of Rome when used by Hannibal in the Punic W ...

*Wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon st ...

*Noric steel

Noric steel was a steel from Noricum, a Celtic kingdom located in modern Austria and Slovenia.

The proverbial hardness of Noric steel is expressed by Ovid: ''"...durior ..ferro quod noricus excoquit ignis..."'' which roughly translates to "...har ...

*Bulat steel

Bulat is a type of steel alloy known in Russia from medieval times; it was regularly mentioned in Russian legends as the material of choice for cold steel. The name ''булат'' is a Russian transliteration of the Persian word ''fulad'', meani ...

*Tamahagane steel

''Tamahagane'' (玉鋼) is a type of steel made in the Japanese tradition. The word ''tama'' means "precious". The word ''hagane'' means "steel". Tamahagane is used to make Japanese swords, knives, and other kinds of tools.

The carbon content ...

*Mokume-gane

is a Japanese metalworking procedure which produces a mixed-metal laminate with distinctive layered patterns; the term is also used to refer to the resulting laminate itself. The term translates closely to "wood grain metal" or "wood eye metal" ...

*Laminated steel blade

A laminated steel blade or piled steel is a knife, sword, or other tool blade made out of layers of differing types of steel, rather than a single homogeneous alloy. The earliest steel blades were laminated out of necessity, due to the early bloom ...

*Tungsten carbide

Tungsten carbide (chemical formula: WC) is a chemical compound (specifically, a carbide) containing equal parts of tungsten and carbon atoms. In its most basic form, tungsten carbide is a fine gray powder, but it can be pressed and formed into ...

References

External links

"Damascene Technique in Metal Working"

* *

John Verhoeven: Mystery of Damascus Steel Swords Unveiled

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Damascus Steel Steels Steelmaking History of Damascus Metalworking Lost inventions Arab inventions