V-2 rocket on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the late 1920s, a young

In the late 1920s, a young  By late 1941, the Army Research Center at Peenemünde possessed the technologies essential to the success of the A-4. The four key technologies for the A-4 were large liquid-fuel rocket engines, supersonic aerodynamics, gyroscopic guidance and rudders in jet control. At the time,

By late 1941, the Army Research Center at Peenemünde possessed the technologies essential to the success of the A-4. The four key technologies for the A-4 were large liquid-fuel rocket engines, supersonic aerodynamics, gyroscopic guidance and rudders in jet control. At the time,

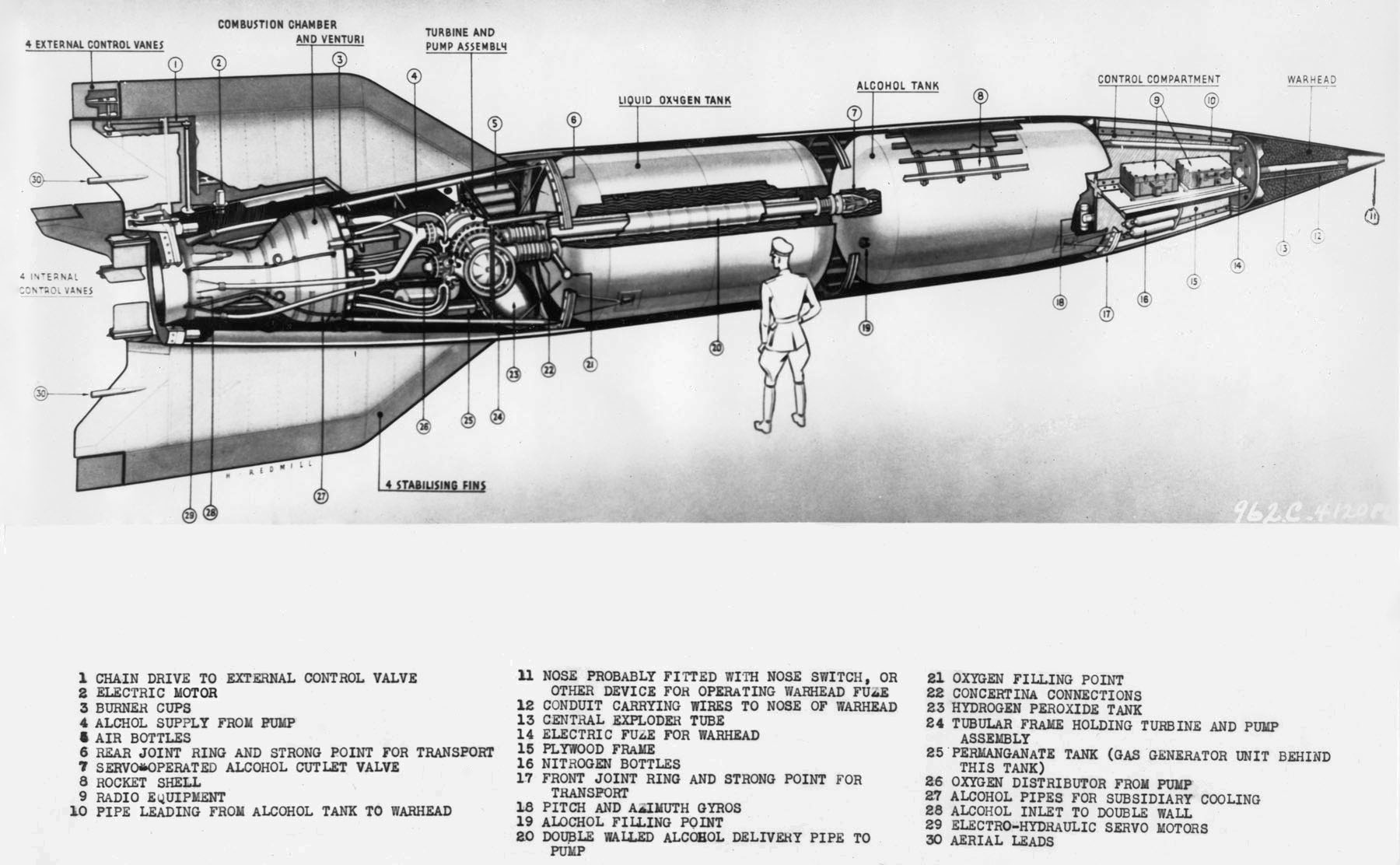

The A-4 used a 75%

The A-4 used a 75%  The V-2 was guided by four external rudders on the tail fins, and four internal

The V-2 was guided by four external rudders on the tail fins, and four internal  The original German designation of the rocket was "V2", unhyphenated – exactly as used for any Third Reich-era "second prototype" example of an RLM-registered German aircraft design – but U.S. publications such as ''

The original German designation of the rocket was "V2", unhyphenated – exactly as used for any Third Reich-era "second prototype" example of an RLM-registered German aircraft design – but U.S. publications such as ''

Two test launches were recovered by the Allies: the Bäckebo rocket, the remnants of which landed in Sweden on 13 June 1944, and one recovered by the Polish resistance on 30 May 1944 from

Two test launches were recovered by the Allies: the Bäckebo rocket, the remnants of which landed in Sweden on 13 June 1944, and one recovered by the Polish resistance on 30 May 1944 from

On 27 March 1942, Dornberger proposed production plans and the building of a launching site on the Channel coast. In December, Speer ordered Major Thom and Dr. Steinhoff to reconnoiter the site near Watten. Assembly rooms were established at Peenemünde and in the

On 27 March 1942, Dornberger proposed production plans and the building of a launching site on the Channel coast. In December, Speer ordered Major Thom and Dr. Steinhoff to reconnoiter the site near Watten. Assembly rooms were established at Peenemünde and in the

Following the Operation Crossbow bombing, initial plans for launching from the massive underground

Following the Operation Crossbow bombing, initial plans for launching from the massive underground

The LXV ''Armeekorps'' z.b.V. formed during the last days of November 1943 in France commanded by ''General der Artillerie'' z.V.

The LXV ''Armeekorps'' z.b.V. formed during the last days of November 1943 in France commanded by ''General der Artillerie'' z.V.

The final two rockets exploded on 27 March 1945. One of these was the last V-2 to kill a British civilian and the final civilian casualty of the war on British soil: Ivy Millichamp, aged 34, killed in her home in Kynaston Road,

The final two rockets exploded on 27 March 1945. One of these was the last V-2 to kill a British civilian and the final civilian casualty of the war on British soil: Ivy Millichamp, aged 34, killed in her home in Kynaston Road,

"Britain and Ballistic Missile Defence, 1942–2002"

, pp. 20–28.

In October 1945, '' Operation Backfire'' assembled a small number of V-2 missiles and launched three of them from a site in northern Germany. The engineers involved had already agreed to move to the US when the test firings were complete. The Backfire report, published in January 1946, contains extensive technical documentation of the rocket, including all support procedures, tailored vehicles and fuel composition.

In 1946, the

In October 1945, '' Operation Backfire'' assembled a small number of V-2 missiles and launched three of them from a site in northern Germany. The engineers involved had already agreed to move to the US when the test firings were complete. The Backfire report, published in January 1946, contains extensive technical documentation of the rocket, including all support procedures, tailored vehicles and fuel composition.

In 1946, the

Only 68 percent of the V-2 trials were considered successful. A supposed V-2 launched on 29 May 1947 landed near Juarez, Mexico and was actually a Hermes B-1 vehicle.

The

Only 68 percent of the V-2 trials were considered successful. A supposed V-2 launched on 29 May 1947 landed near Juarez, Mexico and was actually a Hermes B-1 vehicle.

The

At least 20 V-2s still existed in 2014.

At least 20 V-2s still existed in 2014.

* One at the

* One at the

"V-2 Rocket".

''National Museum of the United States Air Force''. Retrieved: 3 January 2017. (one was transferred from

"The German A4 Rocket (Main Title)"

Information Film of Operation Backfire from IWM

* ttps://books.google.com/books?id=miQDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA124 '"Chute Saves Rockets Secrets" September 1947, ''

Reconstruction, restoration & refurbishment of a V-2 rocket

spherical panoramas of the process and milestones.

Hermann Ludewig Collection, The University of Alabama in Huntsville Archives and Special Collections

Files of Hermann Ludewig, Deputy of Design Chief and later Chief of Acceptance and Inspection on the V-2 program {{authority control * . 1944 in Germany 1944 in military history 1944 in science German inventions of the Nazi period Operation Crossbow Operation Paperclip Peenemünde Army Research Center and Airfield Rockets and missiles Short-range ballistic missiles Space programme of Germany Weapons and ammunition introduced in 1944 Wernher von Braun World War II guided missiles of Germany

The V-2 (german:

documentary, the attacks from resulted in the deaths of an estimated 9,000 civilians and military personnel, and a further 12,000 forced laborers and Vergeltungswaffe

V-weapons, known in original German as (, German: "retaliatory weapons", "reprisal weapons"), were a particular set of long-range artillery weapons designed for strategic bombing during World War II, particularly strategic bombing and/or aer ...

2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat

The Aggregat series (German for "Aggregate") was a set of ballistic missile designs developed in 1933–1945 by a research program of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces (Wehrmacht). Its greatest success was the A4, more commonly known as the V-2.

...

4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within the ...

. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket utilizes a rocket engine that uses liquid rocket propellant, liquid propellants. Liquids are desirable because they have a reasonably high density and high Specific impulse, specific impulse (''I''sp). T ...

engine, was developed during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

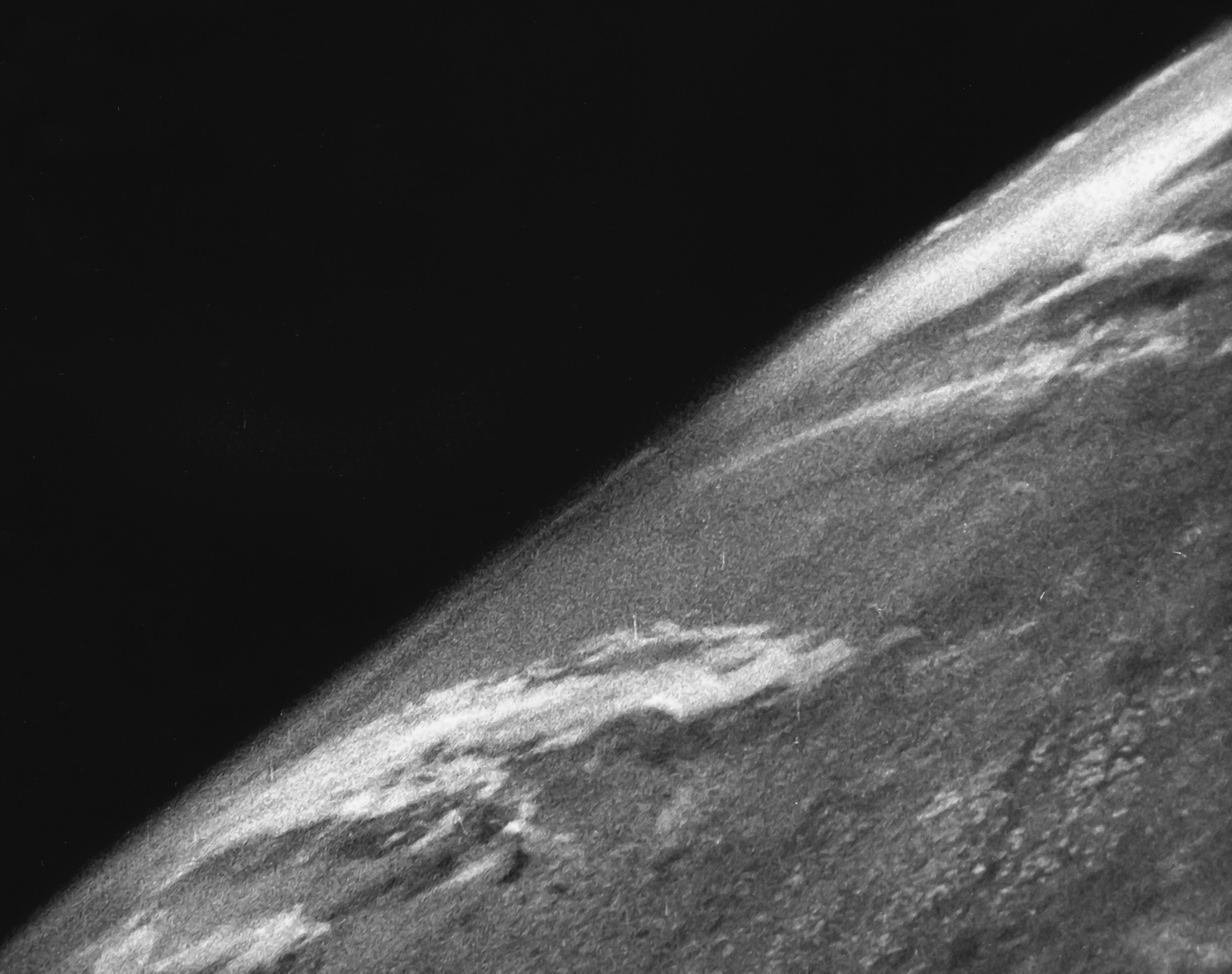

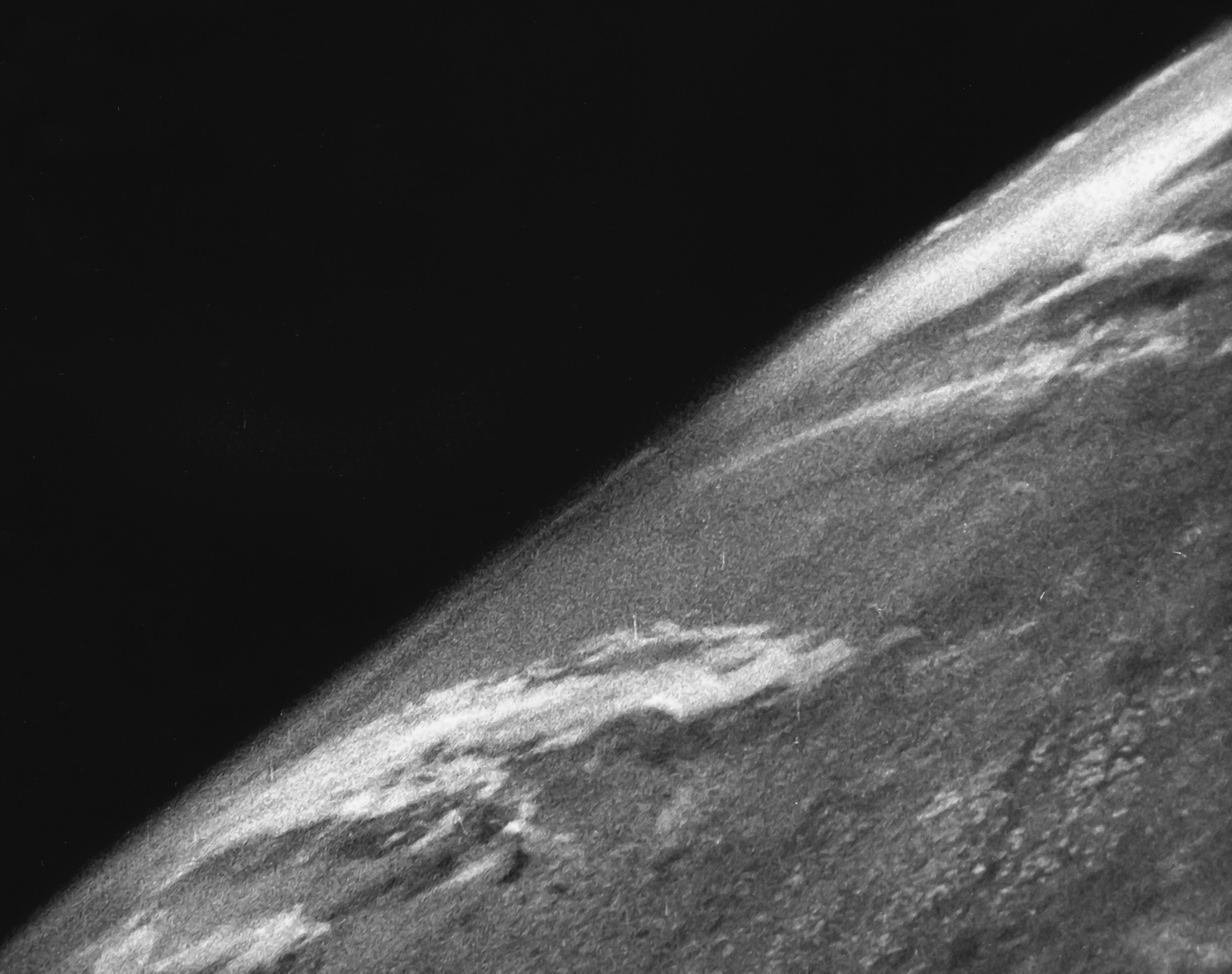

as a "vengeance weapon" and assigned to attack Allied cities as retaliation for the Allied bombings of German cities. The rocket also became the first artificial object to travel into space by crossing the Kármán line

The Kármán line (or von Kármán line ) is an attempt to define a boundary between Earth's atmosphere and outer space, and offers a specific definition set by the Fédération aéronautique internationale (FAI), an international record-keeping ...

(edge of space) with the vertical launch of MW 18014

MW 18014 was a German A-4 test rocket launched on 20 June 1944, at the Peenemünde Army Research Center in Peenemünde. It was the first man-made object to reach outer space, attaining an apogee of 176 kilometers (109.3 miles), which is well abo ...

on 20 June 1944.

Research into military use of long-range rockets began when the graduate studies of Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

attracted the attention of the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

. A series of prototypes culminated in the A-4, which went to war as the . Beginning in September 1944, over 3,000 were launched by the Wehrmacht against Allied targets, first London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and later Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

and Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

. According to a 2011 BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concen ...

prisoners died as a result of their forced participation in the production of the weapons."Am Anfang war die V2. Vom Beginn der Weltraumschifffahrt in Deutschland". In: Utz Thimm (ed.): ''Warum ist es nachts dunkel? Was wir vom Weltall wirklich wissen''. Kosmos, 2006, p. 158, .

The rockets travelled at supersonic speed, impacted without audible warning, and proved unstoppable, as no effective defense existed. Teams from the Allied forces—the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

—raced to seize key Nazi manufacturing facilities, procure the Nazis' missile technology

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket ...

, and capture the V-2’s launching sites. Von Braun and over 100 key personnel surrendered to the Americans, and many of the original team ended up working

Working may refer to:

* Work (human activity), intentional activity people perform to support themselves, others, or the community

Arts and media

* Working (musical), ''Working'' (musical), a 1978 musical

* Working (TV series), ''Working'' (TV s ...

at the Redstone Arsenal. The US also captured enough hardware to build approximately 80 of the missiles. The Soviets gained possession of the manufacturing facilities after the war, re-established production, and moved it to the Soviet Union.

Development history

Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

bought a copy of Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin Ts ...

's book, '' Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen'' (''The Rocket into Interplanetary Spaces''). The world's first large-scale experimental rocket program was Opel-RAK

Opel-RAK were a series of rocket vehicles produced by German automobile manufacturer Fritz von Opel, of the Opel car company, in association with others, including Max Valier, Julius Hatry, and Friedrich Wilhelm Sander. Opel RAK is generally con ...

under the leadership of Fritz von Opel

Fritz Adam Hermann von Opel (4 May 1899 – 8 April 1971) was a German rocket technology pioneer and automotive executive, nicknamed "Rocket-Fritz". He is remembered mostly for his spectacular demonstrations of rocket propulsion that earned him an ...

and Max Valier

Max Valier (9 February 1895 – 17 May 1930) was an Austrian rocketry pioneer. He was a leading figure in the world's first large-scale rocket program, Opel-RAK, and helped found the German ''Verein für Raumschiffahrt'' (VfR – "Spacefligh ...

, a collaborator of Oberth, during the late 1920s leading to the first manned rocket cars and rocket planes, which paved the way for the Nazi era V2 program and US and Soviet activities from 1950 onwards. The Opel RAK program and the spectacular public demonstrations of ground and air vehicles drew large crowds, as well as caused global public excitement as so-called "Rocket Rumble" and had a large long-lasting impact on later spaceflight pioneers, in particular on Wernher von Braun. The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

ended these activities. Von Opel left Germany in 1930 and emigrated later to France and Switzerland.

Starting in 1930, von Braun attended the Technical University of Berlin

The Technical University of Berlin (official name both in English and german: link=no, Technische Universität Berlin, also known as TU Berlin and Berlin Institute of Technology) is a public research university located in Berlin, Germany. It was ...

, where he assisted Oberth in liquid-fueled rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket utilizes a rocket engine that uses liquid propellants. Liquids are desirable because they have a reasonably high density and high specific impulse (''I''sp). This allows the volume of the propellant ta ...

motor tests. Von Braun was working on his doctorate when the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

gained power in Germany. An artillery captain, Walter Dornberger

Major-General Dr. Walter Robert Dornberger (6 September 1895 – 26 June 1980) was a German Army artillery officer whose career spanned World War I and World War II. He was a leader of Nazi Germany's V-2 rocket programme and other projects a ...

, arranged an Ordnance Department research grant for von Braun, who from then on worked next to Dornberger's existing solid-fuel rocket test site at Kummersdorf. Von Braun's thesis, ''Construction, Theoretical, and Experimental Solution to the Problem of the Liquid Propellant Rocket'' (dated 16 April 1934), was kept classified by the German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

and was not published until 1960. By the end of 1934, his group had successfully launched two rockets that reached heights of .

At the time, Germany was highly interested in American physicist Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first Liquid-propellant rocket, liquid-fueled rocket. ...

's research. Before 1939, German engineers and scientists occasionally contacted Goddard directly with technical questions. Von Braun used Goddard's plans from various journals and incorporated them into the building of the '' Aggregate'' (A) series of rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

s, named for the German word for mechanism or mechanical system.

Following successes at Kummersdorf with the first two Aggregate series rockets, Braun and Walter Riedel

Walter J H "Papa" Riedel ("Riedel I") was a German engineer who was the head of the Design Office of the Army Research Centre Peenemünde and the chief designer of the A4 (V-2) ballistic rocket. The crater Riedel on the Moon was co-named for hi ...

began thinking of a much larger rocket in the summer of 1936, based on a projected thrust engine. In addition, Dornberger specified the military requirements needed to include a 1-ton payload, a range of 172 miles with a dispersion of 2 or 3 miles, and transportable using road vehicles.

After the A-4 project was postponed due to unfavorable aerodynamic stability testing of the A-3 in July 1936, English translation 1954.

Braun specified the A-4 performance in 1937, and, after an "extensive" series of test firings of the A-5 scale test model,Christopher, p.111. using a motor redesigned from the troublesome A-3 by Walter Thiel

Walter Thiel (3 March 1910, Breslau – 17 August 1943, Karlshagen, near Peenemünde) was a German rocket scientist.

Thiel provided the decisive ideas for the A4 (V-2) rocket engine and his research enabled rockets to head towards space.

Lif ...

, A-4 design and construction was ordered 1938–39. During 28–30 September 1939, (English: ''The Day of Wisdom'') conference met at Peenemünde

Peenemünde (, en, "Peene iverMouth") is a municipality on the Baltic Sea island of Usedom in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is part of the ''Amt'' (collective municipality) of Usedom-Nord. The communi ...

to initiate the funding of university research to solve rocket problems.

By late 1941, the Army Research Center at Peenemünde possessed the technologies essential to the success of the A-4. The four key technologies for the A-4 were large liquid-fuel rocket engines, supersonic aerodynamics, gyroscopic guidance and rudders in jet control. At the time,

By late 1941, the Army Research Center at Peenemünde possessed the technologies essential to the success of the A-4. The four key technologies for the A-4 were large liquid-fuel rocket engines, supersonic aerodynamics, gyroscopic guidance and rudders in jet control. At the time, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

was not particularly impressed by the V-2; he opined that it was merely an artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...

with a longer range and much higher cost.

In early September 1943, Braun promised the Long-Range Bombardment Commission

Long Range may refer to:

*Long range shooting, a collective term for shooting at such long distances that various atmospheric conditions becomes equally important as pure shooting skills

*Long Range Aviation, a branch of the Soviet Air Forces

*Lon ...

that the A-4 development was "practically complete/concluded", but even by the middle of 1944, a complete A-4 parts list was still unavailable. Hitler was sufficiently impressed by the enthusiasm of its developers, and needed a "wonder weapon

''Wunderwaffe'' () is German word meaning "wonder-weapon" and was a term assigned during World War II by Nazi Germany's propaganda ministry to some revolutionary "superweapons". Most of these weapons however remained prototypes, which either n ...

" to maintain German morale, so he authorized its deployment in large numbers.

The V-2s were constructed at the Mittelwerk

Mittelwerk (; German for "Central Works") was a German World War II factory built underground in the Kohnstein to avoid Allied bombing. It used slave labor from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp to produce V-2 ballistic missiles, V-1 flying ...

site by prisoners

A prisoner (also known as an inmate or detainee) is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement, captivity, or forcible restraint. The term applies particularly to serving a prison sentence in a prison.

...

from Mittelbau-Dora, a concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

where 20,000 prisoners died.

In 1943, the Austrian resistance

The Austrian resistance launched in response to the rise in fascism across Europe and, more specifically, to the Anschluss in 1938 and resulting occupation of Austria by Germany.

An estimated 100,000 people were reported to have participated i ...

group around Heinrich Maier

Heinrich Maier (; 16 February 1908 – 22 March 1945) was an Austrian Roman Catholic priest, pedagogue, philosopher and a member of the Austrian resistance, who was executed as the last victim of Hitler's régime in Vienna.

The resistance gr ...

managed to send exact drawings of the V-2 rocket to the American Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

. Location sketches of V-rocket manufacturing facilities, such as those in Peenemünde, were also sent to the Allied general staff in order to enable Allied bombers to carry out airstrike

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The offic ...

s. This information was particularly important for Operation Crossbow

''Crossbow'' was the code name in World War II for Anglo-American operations against the German V-weapons, long range reprisal weapons (V-weapons) programme.

The main V-weapons were the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket – these were launched aga ...

and Operation Hydra, both preliminary missions for Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

. The group was gradually captured by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

and most of the members were executed.

Technical details

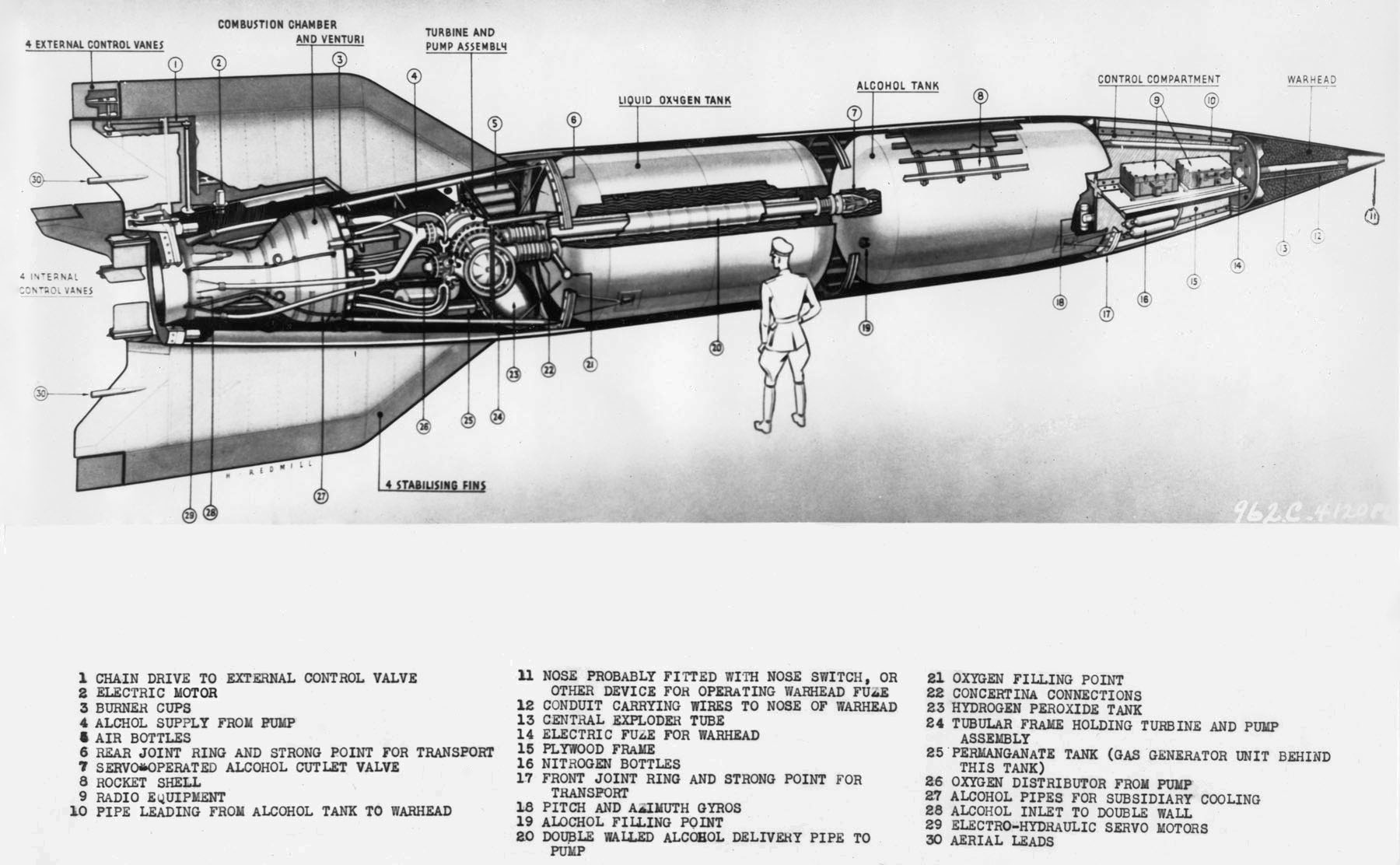

The A-4 used a 75%

The A-4 used a 75% ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl ...

/25% water mixture ( ''B-Stoff'') for fuel and liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen—abbreviated LOx, LOX or Lox in the aerospace, submarine and gas industries—is the liquid form of molecular oxygen. It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an applica ...

(LOX) ( ''A-Stoff'') for oxidizer

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ). In other words, an oxid ...

. The water reduced the flame temperature, acted as a coolant by turning to steam and augmented the thrust, tended to produce a smoother burn, and reduced thermal stress

In mechanics and thermodynamics, thermal stress is mechanical stress created by any change in temperature of a material. These stresses can lead to fracturing or plastic deformation depending on the other variables of heating, which include mater ...

.

Rudolf Hermann's supersonic wind tunnel was used to measure the A-4's aerodynamic characteristics and center of pressure, using a model of the A-4 within a 40 square centimeter chamber. Measurements were made using a Mach 1.86 blowdown nozzle on 8 August 1940. Tests at Mach numbers 1.56 and 2.5 were made after 24 September 1940.

At launch the A-4 propelled itself for up to 65 seconds on its own power, and a program motor held the inclination at the specified angle until engine shutdown, after which the rocket continued on a ballistic free-fall trajectory. The rocket reached a height of or 264,000 ft after shutting off the engine.

The fuel and oxidizer pumps were driven by a steam turbine, and the steam was produced by concentrated hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscous than water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usually as a dilute solution (3%� ...

(T-Stoff

T-Stoff (; 'substance T') was a stabilised high test peroxide used in Germany during World War II. T-Stoff was specified to contain 80% (occasionally 85%) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), remainder water, with traces (<0.1%) of stabilisers. Stabilisers ...

) with sodium permanganate

Sodium permanganate is the inorganic compound with the formula Na MnO4. It is closely related to the more commonly encountered potassium permanganate, but it is generally less desirable, because it is more expensive to produce. It is mainly avai ...

(Z-Stoff

Z-Stoff (, "substance Z") was a name for calcium permanganate or sodium permanganate mixed in water. It was normally used as a catalyst for T-Stoff ( high-test peroxide) in military rocket programs by Nazi Germany during World War II.

Z-Stoff was ...

) catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

. Both the alcohol and oxygen tanks were an aluminum-magnesium alloy.

The turbopump

A turbopump is a propellant pump with two main components: a rotodynamic pump and a driving gas turbine, usually both mounted on the same shaft, or sometimes geared together. They were initially developed in Germany in the early 1940s. The purpo ...

, rotating at 4000 rpm

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensionl ...

, forced the alcohol and oxygen into the combustion chamber at 125 liters (33 US gallons) per second, where they were ignited by a spinning electrical igniter. Thrust increased from 8 tons during this preliminary stage whilst the fuel was gravity-fed, before increasing to 25 tons as the turbopump pressurised the fuel, lifting the 13.5 ton rocket. Combustion gases exited the chamber at , and a speed of 2000 m (6500 feet) per second. The oxygen to fuel mixture was 1.0:0.85 at 25 tons of thrust, but as ambient pressure

Ambient or Ambiance or Ambience may refer to:

Music and sound

* Ambience (sound recording), also known as atmospheres or backgrounds

* Ambient music, a genre of music that puts an emphasis on tone and atmosphere

* ''Ambient'' (album), by Moby

* ...

decreased with flight altitude, thrust increased until it reached 29 tons.Zaloga 2003 p19 The turbopump assembly contained two centrifugal pumps, one for the alcohol, and one for the oxygen, both connected to a common shaft. Hydrogen peroxide converted to steam, using a sodium permanganate catalyst powered the pump, which delivered 55 kg (120 pounds) of alcohol and 68 kg (150 pounds) of liquid oxygen per second to a combustion chamber at 1.5 MPa (210 psi

Psi, PSI or Ψ may refer to:

Alphabetic letters

* Psi (Greek) (Ψ, ψ), the 23rd letter of the Greek alphabet

* Psi (Cyrillic) (Ѱ, ѱ), letter of the early Cyrillic alphabet, adopted from Greek

Arts and entertainment

* "Psi" as an abbreviatio ...

).

Dr. Thiel's development of the 25 ton rocket motor relied on pump feeding, rather than on the earlier pressure feeding. The motor used centrifugal injection, while using both regenerative cooling

Regenerative cooling is a method of cooling gases in which compressed gas is cooled by allowing it to expand and thereby take heat from the surroundings. The cooled expanded gas then passes through a heat exchanger where it cools the incoming comp ...

and film cooling. Film cooling admitted alcohol into the combustion chamber and exhaust nozzle under slight pressure through four rings of small perforations. The mushroom-shaped injection head was removed from the combustion chamber to a mixing chamber, the combustion chamber was made more spherical while being shortened from 6 to 1 foot in length, and the connection to the nozzle was made cone shaped. The resultant 1.5 ton chamber operated at a combustion pressure of 1.52 MPa (220 psi). Thiel's 1.5 ton chamber was then scaled up to a 4.5 ton motor by arranging three injection heads above the combustion chamber. By 1939, eighteen injection heads in two concentric circles at the head of the 3 mm (0.12-inch) thick sheet-steel chamber, were used to make the 25 ton motor.

The warhead was another source of trouble. The explosive employed was amatol 60/40 detonated by an electric contact fuze

A contact fuze, impact fuze, percussion fuze or direct-action (D.A.) fuze (''UK'') is the fuze that is placed in the nose of a bomb or shell so that it will detonate on contact with a hard surface.

Many impacts are unpredictable: they may involve ...

. Amatol had the advantage of stability, and the warhead was protected by a thick layer of glass wool

Glass wool is an insulating material made from glass fiber arranged using a binder into a texture similar to wool. The process traps many small pockets of air between the glass, and these small air pockets result in high thermal insulation prop ...

, but even so it could still explode in the re-entry phase. The warhead weighed and contained of explosive. The warhead's percentage by weight that was explosive was 93%, a very high percentage when compared with other types of munition.

A protective layer of glass wool was also used for the fuel tanks so the A-4 did not have a tendency to form ice, a problem which plagued other early ballistic missiles such as the balloon tank

A balloon tank is a style of propellant tank used in the SM-65 Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and Centaur upper stage that does not use an internal framework, but instead relies on a positive internal pressurization to keep it ...

-design SM-65 Atlas

The SM-65 Atlas was the first operational intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) developed by the United States and the first member of the Atlas rocket family. It was built for the U.S. Air Force by the Convair Division of General Dyna ...

which entered US service in 1959. The tanks held of ethyl alcohol and of oxygen.

The V-2 was guided by four external rudders on the tail fins, and four internal

The V-2 was guided by four external rudders on the tail fins, and four internal graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on large ...

vanes in the jet stream at the exit of the motor. These 8 control surfaces were controlled by Helmut Hölzer )

, image = File:HolzerHelmut Huntsville.jpg

, image_size = 100px

, caption = Helmut Hölzer in Huntsville, Alabama

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bad Liebenstein, Thüringen, German Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = Huntsville, Alaba ...

's analog computer

An analog computer or analogue computer is a type of computer that uses the continuous variation aspect of physical phenomena such as electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic quantities (''analog signals'') to model the problem being solved. In c ...

, the , via electrical-hydraulic servomotor

A servomotor (or servo motor) is a rotary actuator or linear actuator that allows for precise control of angular or linear position, velocity and acceleration. It consists of a suitable motor coupled to a sensor for position feedback. It also r ...

s, based on electrical signals from the gyros. The Siemens ''Vertikant'' LEV-3 guidance system consisted of two free gyroscope

A gyroscope (from Ancient Greek γῦρος ''gŷros'', "round" and σκοπέω ''skopéō'', "to look") is a device used for measuring or maintaining orientation and angular velocity. It is a spinning wheel or disc in which the axis of rota ...

s (a horizontal for pitch and a vertical with two degrees of freedom for yaw and roll) for lateral stabilization, coupled with a PIGA accelerometer

A PIGA (''Pendulous Integrating Gyroscopic Accelerometer'') is a type of accelerometer that can measure acceleration and simultaneously integrates this acceleration against time to produce a speed measure as well. The PIGA's main use is in Inertia ...

, or the Walter Wolman radio control system, to control engine cutoff at a specified velocity. Other gyroscopic systems used in the A-4 included Kreiselgeräte's SG-66 and SG-70. The V-2 was launched from a pre-surveyed location, so the distance and azimuth

An azimuth (; from ar, اَلسُّمُوت, as-sumūt, the directions) is an angular measurement in a spherical coordinate system. More specifically, it is the horizontal angle from a cardinal direction, most commonly north.

Mathematicall ...

to the target were known. Fin 1 of the missile was aligned to the target azimuth.

Some later V-2s used " guide beams", radio signals transmitted from the ground, to keep the missile on course, but the first models used a simple analog computer that adjusted the azimuth for the rocket, and the flying distance was controlled by the timing of the engine cut-off, '' Brennschluss'', ground-controlled by a Doppler system or by different types of on-board integrating accelerometer

An accelerometer is a tool that measures proper acceleration. Proper acceleration is the acceleration (the rate of change of velocity) of a body in its own instantaneous rest frame; this is different from coordinate acceleration, which is accele ...

s. Thus, range was a function of engine burn time, which ended when a specific velocity was achieved. Just before engine cutoff, thrust was reduced to eight tons, in an effort to avoid any water hammer

Hydraulic shock (colloquial: water hammer; fluid hammer) is a pressure surge or wave caused when a fluid in motion, usually a liquid but sometimes also a gas is forced to stop or change direction suddenly; a momentum change. This phenomenon com ...

problems a rapid cutoff could cause.

Dr. Friedrich Kirchstein of Siemens

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

The principal divisions of the corporation are ''Industry'', '' ...

of Berlin developed the V-2 radio control

Radio control (often abbreviated to RC) is the use of control signals transmitted by radio to remotely control a device. Examples of simple radio control systems are garage door openers and keyless entry systems for vehicles, in which a small ...

for motor-cut-off (german: Brennschluss). For velocity measurement, Professor Wolman of Dresden created an alternative of his Doppler tracking system in 1940–41, which used a ground signal transponded by the A-4 to measure the velocity of the missile. By 9 February 1942, Peenemünde engineer Gerd had documented the radio interference area of a V-2 as around the "Firing Point", and the first successful A-4 flight on 3 October 1942, used radio control for . Although Hitler commented on 22 September 1943 that "It is a great load off our minds that we have dispensed with the radio guiding-beam; now no opening remains for the British to interfere technically with the missile in flight", about 20% of the operational V-2 launches were beam-guided. The Operation Pinguin V-2 offensive began on 8 September 1944, when (English: 'Training and Testing Battery 444') launched a single rocket guided by a radio beam directed at Paris. Wreckage of combat V-2s occasionally contained the transponder for velocity and fuel cutoff.

The painting of the operational V-2s was mostly a ragged-edged pattern with several variations, but at the end of the war a plain olive green rocket also appeared. During tests the rocket was painted in a characteristic black-and-white chessboard

A chessboard is a used to play chess. It consists of 64 squares, 8 rows by 8 columns, on which the chess pieces are placed. It is square in shape and uses two colours of squares, one light and one dark, in a chequered pattern. During play, the bo ...

pattern, which aided in determining if the rocket was spinning around its longitudinal axis.

The original German designation of the rocket was "V2", unhyphenated – exactly as used for any Third Reich-era "second prototype" example of an RLM-registered German aircraft design – but U.S. publications such as ''

The original German designation of the rocket was "V2", unhyphenated – exactly as used for any Third Reich-era "second prototype" example of an RLM-registered German aircraft design – but U.S. publications such as ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' magazine were using the hyphenated form "V-2" as early as December 1944.

Testing

The first successful test flight was on 3 October 1942, reaching an altitude of . On that day, Walter Dornberger declared in a speech at Peenemünde: Two test launches were recovered by the Allies: the Bäckebo rocket, the remnants of which landed in Sweden on 13 June 1944, and one recovered by the Polish resistance on 30 May 1944 from

Two test launches were recovered by the Allies: the Bäckebo rocket, the remnants of which landed in Sweden on 13 June 1944, and one recovered by the Polish resistance on 30 May 1944 from Blizna :''See also Blizna, Podlaskie Voivodeship. For the Polish film of this name see The Scar (1976 film).''

Blizna is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Ostrów, within Ropczyce-Sędziszów County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south- ...

and transported to the UK during Operation Most III

Operation Most III ( Polish for ''Bridge III'') or Operation Wildhorn III (in British documents) was a World War II operation in which Poland's ''Armia Krajowa'' provided the Allies with crucial intelligence on the German V-2 rocket.

Ba ...

. The highest altitude reached during the war was (20 June 1944). Test launches of V-2 rockets were made at Peenemünde, Blizna and Tuchola Forest

The Tuchola Forest, also known as Tuchola Pinewoods or Tuchola Conifer Woods, (the latter a literal translation of pl, Bory Tucholskie; csb, Tëchòlsczé Bòrë; german: Tuchler or Tucheler Heide) is a large forest complex near the town of Tuch ...

, and after the war, at Cuxhaven by the British, White Sands Proving Grounds

White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) is a United States Army military testing area and firing range located in the US state of New Mexico. The range was originally established as the White Sands Proving Ground on 9July 1945. White Sands National P ...

and Cape Canaveral

, image = cape canaveral.jpg

, image_size = 300

, caption = View of Cape Canaveral from space in 1991

, map = Florida#USA

, map_width = 300

, type =Cape

, map_caption = Location in Florida

, location ...

by the U.S., and Kapustin Yar

Kapustin Yar (russian: Капустин Яр) is a Russian rocket launch complex in Astrakhan Oblast, about 100 km east of Volgograd. It was established by the Soviet Union on 13 May 1946. In the beginning, Kapustin Yar used technology, material ...

by the USSR.

Various design issues were identified and solved during V-2 development and testing:

:* To reduce tank pressure and weight, high flow turbopumps were used to boost pressure.

:* A short and lighter combustion chamber

A combustion chamber is part of an internal combustion engine in which the fuel/air mix is burned. For steam engines, the term has also been used for an extension of the firebox which is used to allow a more complete combustion process.

Interna ...

without burn-through was developed by using centrifugal injection nozzles, a mixing compartment, and a converging nozzle to the throat for homogeneous combustion.

:* Film cooling was used to prevent burn-through at the nozzle throat.

:* Relay contacts were made more durable to withstand vibration and prevent thrust cut-off just after lift-off.

:* Ensuring that the fuel pipes had tension-free curves reduced the likelihood of explosions at .

:* Fins were shaped with clearance to prevent damage as the exhaust jet expanded with altitude.

:* To control trajectory at liftoff and supersonic speeds, heat-resistant graphite vanes were used as rudders in the exhaust jet.

Air burst problem

Through mid-March 1944, only four of the 26 successful Blizna launches had satisfactorily reached theSarnaki

Sarnaki is a village in Łosice County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It is the seat of the gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Sarnaki. It lies approximately north-east of Łosice and east of Warsaw

Warsaw ( p ...

target area due to in-flight breakup () on re-entry into the atmosphere. (As mentioned above, one rocket was collected by the Polish Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

, with parts of it transported to London for tests.) Initially, the German developers suspected excessive alcohol tank pressure, but by April 1944, after five months of test firings, the cause was still not determined. Major-General Rossmann, the Army Weapons Office department chief, recommended stationing observers in the target area – May/June, Dornberger and von Braun set up a camp at the centre of the Poland target zone. After moving to the Heidekraut, SS Mortar Battery 500 of the 836th Artillery Battalion (Motorized) was ordered on 30 August to begin test launches of eighty 'sleeved' rockets. Testing confirmed that the so-called 'tin trousers' – a tube designed to strengthen the forward end of the rocket cladding – reduced the likelihood of air bursts.

Production

On 27 March 1942, Dornberger proposed production plans and the building of a launching site on the Channel coast. In December, Speer ordered Major Thom and Dr. Steinhoff to reconnoiter the site near Watten. Assembly rooms were established at Peenemünde and in the

On 27 March 1942, Dornberger proposed production plans and the building of a launching site on the Channel coast. In December, Speer ordered Major Thom and Dr. Steinhoff to reconnoiter the site near Watten. Assembly rooms were established at Peenemünde and in the Friedrichshafen

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''Kre ...

facilities of Zeppelin Works. In 1943, a third factory, Raxwerke

Raxwerke or Rax-Werke was a facility of the Wiener Neustädter Lokomotivfabrik at Wiener Neustadt in Lower Austria. During World War II, the company also produced lamps for Panzer tanks and anti-aircraft guns. Two Raxwerke plants employed several ...

, was added.

On 22 December 1942, Hitler signed the order for mass production, when Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

assumed final technical data would be ready by July 1943. However, many issues still remained to be solved even by the autumn of 1943.

On 8 January 1943, Dornberger and von Braun met with Speer. Speer stated, "As head of the Todt organisation

Organisation Todt (OT; ) was a civil and military engineering organisation in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, named for its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior Nazi. The organisation was responsible for a huge range of engineering projec ...

I will take it on myself to start at once with the building of the launching site on the Channel coast," and established an A-4 production committee under Degenkolb.

On 26 May 1943, the Long-Range Bombardment Commission, chaired by AEG

Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft AG (AEG; ) was a German producer of electrical equipment founded in Berlin as the ''Deutsche Edison-Gesellschaft für angewandte Elektricität'' in 1883 by Emil Rathenau. During the Second World War, AEG ...

director Petersen, met at Peenemünde to review the V-1 V1, V01 or V-1 can refer to version one (for anything) (e.g., see version control)

V1, V01 or V-1 may also refer to:

In aircraft

* V-1 flying bomb, a World War II German weapon

* V1 speed, the maximum speed at which an aircraft pilot may abort ...

and V-2 automatic long-range weapons. In attendance were Speer, Air Marshal Erhard Milch

Erhard Milch (30 March 1892 – 25 January 1972) was a German general field marshal ('' Generalfeldmarschall'') of Jewish heritage who oversaw the development of the German air force (''Luftwaffe'') as part of the re-armament of Nazi Germany fo ...

, Admiral Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

, Col. General Friedrich Fromm

Friedrich Wilhelm Waldemar Fromm (8 October 1888 – 12 March 1945) was a German Army officer. In World War II, Fromm was Commander in Chief of the Replacement Army (''Ersatzheer''), in charge of training and personnel replacement for combat divi ...

, and Karl Saur

Karl-Otto Saur (February 16, 1902 in Düsseldorf – July 28, 1966 in Pullach) was a high ranking official in the Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany and was named as ''Reichsminister'' of Munitions in Adolf Hitler ...

. Both weapons had reached the final stage of development, and the commission decided to recommend to Hitler that both weapons be put into mass production. As Dornberger observed, "The disadvantages of the one would be compensated by the other's advantages."

On 7 July 1943, Major General Dornberger, von Braun, and Dr. Steinhof briefed Hitler in his Wolf's Lair

The ''Wolf's Lair'' (german: Wolfsschanze; pl, Wilczy Szaniec) served as Adolf Hitler's first Eastern Front military headquarters in World War II.

The headquarters was located in the Masurian woods, near the small village of Görlitz in Ost ...

. Also in attendance were Speer, Wilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal and war criminal who held office as chief of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces, duri ...

, and Alfred Jodl

Alfred Josef Ferdinand Jodl (; 10 May 1890 – 16 October 1946) was a German ''Generaloberst'' who served as the chief of the Operations Staff of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' – the German Armed Forces High Command – throughout World ...

. The briefing included von Braun narrating a film showing the successful launch on 3 October 1942, with scale models of the Channel coast firing bunker, and supporting vehicles, including the . Hitler then gave Peenemünde top priority in the German armaments program stating, "Why was it I could not believe in the success of your work? if we had had these rockets in 1939 we should never have had this war..." Hitler also wanted a second launch bunker built.

Saur planned to build 2,000 rockets per month, between the existing three factories and the Nordhausen Mittelwerk factory being built. However, alcohol production was dependent upon the potato harvest.

A production line was nearly ready at Peenemünde when the Operation Hydra attack occurred. The main targets of the attack included the test stands, the development works, the Pre-Production Works, the settlement where the scientists and technicians lived, the Trassenheide camp, and the harbor sector. According to Dornberger, "Serious damage to the works, contrary to first impressions, was surprisingly small." Work resumed after a delay of four to six weeks, and because of camouflage to mimic complete destruction, there were no more raids over the next nine months. The raid resulted in 735 lives lost, with heavy losses at Trassenheide, while 178 were killed in the settlement, including Dr. Thiel, his family, and Chief Engineer Walther. The Germans eventually moved production to the underground ''Mittelwerk'' in the Kohnstein where 5,200 V-2 rockets were built with the use of forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

.

Launch sites

Following the Operation Crossbow bombing, initial plans for launching from the massive underground

Following the Operation Crossbow bombing, initial plans for launching from the massive underground Watten

Watten may refer to:

Places

* Watten, Nord, a commune in the Nord ''département'' of France

** ''Blockhaus d'Éperlecques'' or Watten bunker, intended to be a launching facility for the V-2 ballistic missile

* Watten, Highland, a village in Cai ...

, Wizernes

Wizernes (; vls, Wezerne) is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department, northern France. It lies southwest of Saint-Omer on the banks of the river Aa at the D928 and D211 road junction. The commune is twinned with Ensdorf, Germany.

Populati ...

and Sottevast

Sottevast () is a commune in Normandy in north-western France.

Sottevast in World War II

During World War II, there was a German storage and servicing bunker for V-weapons near Sottevast. The site was captured by the 504th Parachute Infantry R ...

bunkers or from fixed pads such as near the Château du Molay were dropped in favour of mobile launching. Eight main storage dumps were planned and four had been completed by July 1944 (the one at Mery-sur-Oise was begun in August 1943 and completed by February 1944). The missile could be launched practically anywhere, roads running through forests being a particular favourite. The system was so mobile and small that only one was ever caught in action by Allied aircraft, during the Operation Bodenplatte

Operation Bodenplatte (; "Baseplate"), launched on 1 January 1945, was an attempt by the Luftwaffe to cripple Allied air forces in the Low Countries during the Second World War. The goal of ''Bodenplatte'' was to gain air superiority during th ...

attack on 1 January 1945 near Lochem

Lochem () is a city and municipality in the province of Gelderland in the Eastern Netherlands. In 2005, it merged with the municipality of Gorssel, retaining the name of Lochem. As of 2019, it had a population of 33,590.

Population centres

The ...

by a USAAF 4th Fighter Group aircraft, although Raymond Baxter

Raymond Frederic Baxter OBE (25 January 1922 – 15 September 2006) was an English television presenter, commentator and writer. He is best known for being the first presenter of the BBC Television science programme ''Tomorrow's World'', con ...

described flying over a site during a launch and his wingman firing at the missile without hitting it.

It was estimated that a sustained rate of 350 V-2s could be launched per week, with 100 per day at maximum effort, given sufficient supply of the rockets.

Operational history

The LXV ''Armeekorps'' z.b.V. formed during the last days of November 1943 in France commanded by ''General der Artillerie'' z.V.

The LXV ''Armeekorps'' z.b.V. formed during the last days of November 1943 in France commanded by ''General der Artillerie'' z.V. Erich Heinemann

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, or Eirik is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-Norse ''* ain ...

was responsible for the operational use of V-2. Three launch battalions were formed in late 1943, ''Artillerie Abteilung'' 836 (Mot.), Grossborn, Artillerie Abteilung 485 (Mot.), Naugard

Nowogard () ( csb, Nowògard; formerly german: Naugard) is a town in northwestern Poland, in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. it had a population of 16,733.

Name

''Nowogard'' is a combination of two Slavic terms: novi (new) and gard, which is P ...

, and ''Artillerie Abteilung'' 962 (''Mot.''). Combat operations commenced in Sept. 1944, when training Batterie 444 deployed. On 2 September 1944, the SS ''Werfer-Abteilung'' 500 was formed, and by October, the SS under the command of SS Lt. Gen Hans Kammler, took operational control of all units. He formed ''Gruppe Sud'' with Art. Abt. 836, Merzig

Merzig (, french: Mercy, ''Moselle Franconian:'' ''Meerzisch''/''Miërzësch'') is a town in Saarland, Germany. It is the capital of the district Merzig-Wadern, with about 30,000 inhabitants in 17 municipalities on 108 km². It is situated ...

, and ''Gruppe Nord'' with Art. Abt. 485 and ''Batterie'' 444, Burgsteinfurt

Steinfurt (; Westphalian: ''Stemmert'') is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Steinfurt. From roughly 1100-1806, it was the capital of the County of Steinfurt.

Geography

Steinfurt is situated north- ...

and The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

.

After Hitler's 29 August 1944 declaration to begin V-2 attacks as soon as possible, the offensive began on 7 September 1944 when two were launched at Paris (which the Allies had liberated less than two weeks earlier), but both crashed soon after launch. On 8 September a single rocket was launched at Paris, which caused modest damage near Porte d'Italie

Porte d'Italie is one of the city gates of Paris, located in the 13th arrondissement, at the intersection of Avenue d'Italie, Boulevard Massena, Avenue de la Porte d'Italie and street Kellermann, facing the Kremlin-Bicetre.

The "gate of Italy" i ...

. Two more launches by the 485th followed, including one from The Hague against London on the same day at 6:43 pm. – the first landed at Staveley Road

Staveley Road is a road in Chiswick in the London Borough of Hounslow which was the site of the first successful V-2 rocket, V-2 missile attack against Britain.

History

Staveley Road was built between 1927 and 1931 as part of the Chiswick Park ...

, Chiswick

Chiswick ( ) is a district of west London, England. It contains Hogarth's House, the former residence of the 18th-century English artist William Hogarth; Chiswick House, a neo-Palladian villa regarded as one of the finest in England; and Full ...

, killing 63-year-old Mrs. Ada Harrison, three-year-old Rosemary Clarke, and Sapper

A sapper, also called a pioneer (military), pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefie ...

Bernard Browning on leave from the Royal Engineers, and one that hit Epping with no casualties. Upon hearing the double-crack of the supersonic rocket (London's first ever), Duncan Sandys

Edwin Duncan Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a key ro ...

and Reginald Victor Jones

Reginald Victor Jones , FRSE, LLD (29 September 1911 – 17 December 1997) was a British physicist and scientific military intelligence expert who played an important role in the defence of Britain in by solving scientific and technical pr ...

looked up from different parts of the city and exclaimed "That was a rocket!", and a short while after the double-crack, the sky was filled with the sound of a heavy body rushing through the air.

The British government, concerned about spreading panic or giving away vital intelligence to German forces, initially attempted to conceal the cause of the explosions by making no official announcement, and euphemistically blaming them on defective gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

mains. The public did not believe this explanation and therefore began referring to the V-2s as "flying gas mains". The Germans themselves finally announced the V-2 on 8 November 1944 and only then, on 10 November 1944, did Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

inform Parliament, and the world, that England had been under rocket attack "for the last few weeks".

In September 1944, control of the V-2 mission was taken over by the Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

and Division z.V.

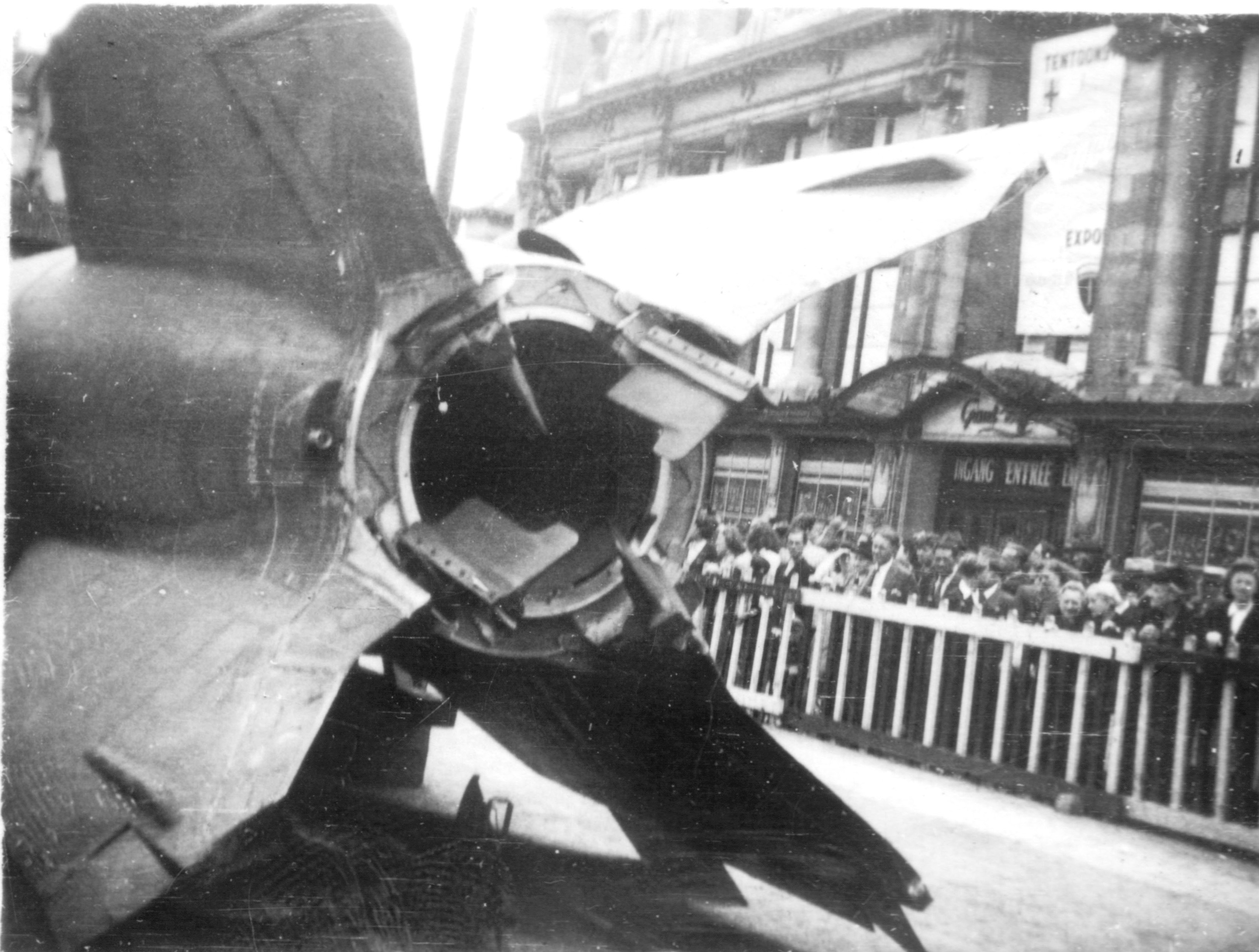

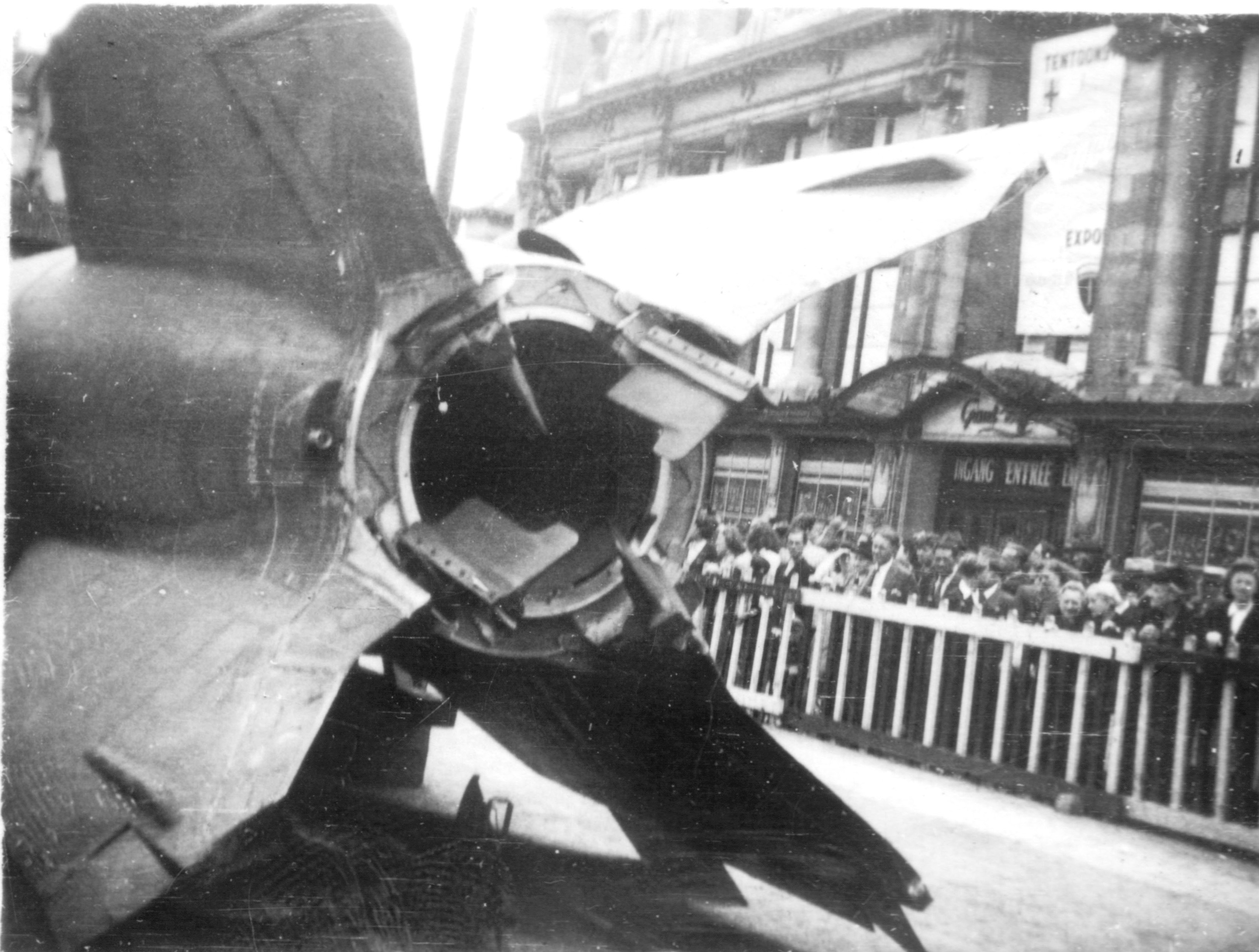

Positions of the German launch units changed a number of times. For example, ''Artillerie Init 444'' arrived in the southwest Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

(in Zeeland

, nl, Ik worstel en kom boven("I struggle and emerge")

, anthem = "Zeeuws volkslied"("Zeelandic Anthem")

, image_map = Zeeland in the Netherlands.svg

, map_alt =

, m ...

) in September 1944. From a field near the village of Serooskerke, five V-2s were launched on 15 and 16 September, with one more successful and one failed launch on the 18th. That same date, a transport carrying a missile took a wrong turn and ended up in Serooskerke itself, giving a villager the opportunity to surreptitiously take some photographs of the weapon; these were smuggled to London by the Dutch Resistance. After that the unit moved to the woods near Rijs

Rijs ( fry, Riis) is a village within the municipality of De Fryske Marren in the province of Friesland, the Netherlands.

Rijs is situated on the road between Oudemirdum and Hemelum. It has approximately 170 citizens (2017). Rijs is best known ...

, Gaasterland in the northwest Netherlands, to ensure that the technology did not fall into Allied hands. From Gaasterland V-2s were launched against Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

and Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

from 25 September (London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

being out of range). Because of their inaccuracy, these V-2s did not hit their target cities. Shortly after that only London and Antwerp remained as designated targets as ordered by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

himself, Antwerp being targeted in the period of 12 to 20 October, after which time the unit moved to The Hague.

Targets

Over the following months about 3,172 V-2 rockets were fired at the following targets: :Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, 1,664: Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

(1,610), Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

(27), Hasselt (13), Tournai

Tournai or Tournay ( ; ; nl, Doornik ; pcd, Tornai; wa, Tornè ; la, Tornacum) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies southwest of Brussels on the river Scheldt. Tournai is part of Euromet ...

(9), Mons

Mons (; German and nl, Bergen, ; Walloon and pcd, Mont) is a city and municipality of Wallonia, and the capital of the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

Mons was made into a fortified city by Count Baldwin IV of Hainaut in the 12th century. T ...

(3), Diest

Diest () is a city and municipality located in the Belgian province of Flemish Brabant. Situated in the northeast of the Hageland region, Diest neighbours the provinces of Antwerp to its North, and Limburg to the East and is situated around ...

(2)

: United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, 1,402: London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

(1,358), Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

(43), Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

(1)

: France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, 76: Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Pref ...

(25), Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

(22), Tourcoing

Tourcoing (; nl, Toerkonje ; vls, Terkoeje; pcd, Tourco) is a city in northern France on the Belgian border. It is designated municipally as a commune within the department of Nord. Located to the north-northeast of Lille, adjacent to Roubai ...

(19), Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais Departments of France, department, which forms part of the regions of France, region of Hauts-de-France; before the regions of France#Reform and mergers of ...

(6), Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

(4)

: Netherlands, 19: Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of the ...

(19)

: Germany, 11: Remagen

Remagen ( ) is a town in Germany in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, in the district of Ahrweiler. It is about a one-hour drive from Cologne, just south of Bonn, the former West German capital. It is situated on the left (western) bank of the ...

(11)

Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, Belgium was a target for a large number of V-weapon attacks from October 1944 through to the virtual end of the war in March 1945, leaving 1,736 dead and 4,500 injured in greater Antwerp. Thousands of buildings were damaged or destroyed as the city was struck by 590 direct hits. The largest loss of life by a single rocket attack during the war came on 16 December 1944, when the roof of the crowded Cine Rex

''Cinema Rex'' was a Movie theater, cinema located at Keyserlei 15 in Antwerp, Belgium. It opened in 1935 and was designed by Leon Stynen, a Belgian architect, modeled after large American movie theatres.

On 16 December 1944 (the first day of t ...

was struck, leaving 567 dead and 291 injured.

An estimated 2,754 civilians were killed in London by V-2 attacks with another 6,523 injured, which is two people killed per V-2 rocket. However, this understates the potential of the V-2, since many rockets were misdirected and exploded harmlessly. Accuracy increased over the course of the war, particularly for batteries where the (radio guide beam) system was used. Missile strikes that found targets could cause large numbers of deaths – 160 were killed and 108 seriously injured in one explosion at 12:26 pm on 25 November 1944, at a Woolworth's

Woolworth, Woolworth's, or Woolworths may refer to:

Businesses

* F. W. Woolworth Company, the original US-based chain of "five and dime" (5¢ and 10¢) stores

* Woolworths Group (United Kingdom), former operator of the Woolworths chain of shops ...

department store in New Cross

New Cross is an area in south east London, England, south-east of Charing Cross in the London Borough of Lewisham and the SE14 postcode district. New Cross is near St Johns, Telegraph Hill, Nunhead, Peckham, Brockley, Deptford and Greenwic ...

, south-east London.

British intelligence sent false reports via their Double-Cross System

The Double-Cross System or XX System was a World War II counter-espionage and deception operation of the British Security Service (a civilian organisation usually referred to by its cover title MI5). Nazi agents in Britain – real and false – w ...

implying that the rockets were over-shooting their London target by . This tactic worked; more than half of the V-2s aimed at London landed outside the London Civil Defence Region.Jones RV; Most Secret War 1978 Most landed on less-heavily populated areas in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

due to erroneous recalibration. For the remainder of the war, British intelligence kept up the ruse by repeatedly sending bogus reports implying that the rockets were now striking the British capital with heavy loss of life.Blitz Street; Channel 4, 10 May 2010

Possible use during Operation Bodenplatte

At least one V-2 missile on a mobile ''Meillerwagen

The ''Meillerwagen'' ( en, Meiller vehicle) was a German World War II trailer used to transport a V-2 rocket from the 'transloading point' of the Technical Troop Area to the launching point, to erect the missile on the ''Brennstand'' ( en, firing ...

'' launch trailer was observed being elevated to launch position by a USAAF

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

4th Fighter Group pilot defending against the massive New Year's Day 1945 Operation Bodenplatte strike by the Luftwaffe over the northern German attack route near the town of Lochem on 1 January 1945. Possibly, from the potential sighting of the American fighter by the missile's launch crew, the rocket was quickly lowered from a near launch-ready 85° elevation to 30°.

Tactical use on German target

After the US Army captured theLudendorff Bridge

The Ludendorff Bridge (sometimes referred to as the Bridge at Remagen) was in early March 1945 a critical remaining bridge across the river Rhine in Germany when it was captured during the Battle of Remagen by United States Army forces durin ...

during the Battle of Remagen

The Battle of Remagen was an 18-day battle during the Allied invasion of Germany in World War II from 7 to 25 March 1945 when American forces unexpectedly captured the Ludendorff Bridge over the Rhine intact. They were able to hold it against ...

on 7 March 1945, the Germans were desperate to destroy it. On 17 March 1945, they fired eleven V-2 missiles at the bridge, their first use against a tactical target and the only time they were fired on a German target during the war. They could not employ the more accurate device because it was oriented towards Antwerp and could not be easily adjusted for another target. Fired from near Hellendoorn

Hellendoorn (; Tweants: ''Heldern'' or ''Healndoorn'') is a municipality and town in the middle of the Dutch province of Overijssel. As of 2019, the municipality had a population of 35,808.

There is an amusement park near the town of Hellendoorn ...

, the Netherlands, one of the missiles landed as far away as Cologne, to the north, while one missed the bridge by only . They also struck the town of Remagen, destroying a number of buildings and killing at least six American soldiers.

Final use

The final two rockets exploded on 27 March 1945. One of these was the last V-2 to kill a British civilian and the final civilian casualty of the war on British soil: Ivy Millichamp, aged 34, killed in her home in Kynaston Road,

The final two rockets exploded on 27 March 1945. One of these was the last V-2 to kill a British civilian and the final civilian casualty of the war on British soil: Ivy Millichamp, aged 34, killed in her home in Kynaston Road, Orpington

Orpington is a town and area in south east London, England, within the London Borough of Bromley. It is 13.4 miles (21.6 km) south east of Charing Cross.

On the south-eastern edge of the Greater London Built-up Area, it is south of St Ma ...

in Kent. A scientific reconstruction carried out in 2010 demonstrated that the V-2 creates a crater wide and deep, ejecting approximately 3,000 tons of material into the air.

Countermeasures

Big Ben and Crossbow

Unlike theV-1 V1, V01 or V-1 can refer to version one (for anything) (e.g., see version control)

V1, V01 or V-1 may also refer to:

In aircraft

* V-1 flying bomb, a World War II German weapon

* V1 speed, the maximum speed at which an aircraft pilot may abort ...

, the V-2's speed and trajectory made it practically invulnerable to anti-aircraft guns and fighters, as it dropped from an altitude of at up to three times the speed of sound at sea level (approximately 3550 km/h). Nevertheless, the threat of what was then code-named "Big Ben" was great enough that efforts were made to seek countermeasures. The situation was similar to the pre-war concerns about manned bombers and led to a similar solution, the formation of the Crossbow Committee, to collect, examine and develop countermeasures.

Early on, it was believed that the V-2 employed some form of radio guidance, a belief that persisted in spite of several rockets being examined without discovering anything like a radio receiver. This led to efforts to jam this non-existent guidance system as early as September 1944, using both ground and air-based jammers flying over the UK. In October, a group had been sent to jam the missiles during launch. By December it was clear these systems were having no obvious effect, and jamming efforts ended.Jeremy Stocker"Britain and Ballistic Missile Defence, 1942–2002"

, pp. 20–28.

Anti-aircraft gun system

GeneralFrederick Alfred Pile

General Sir Frederick Alfred Pile, 2nd Baronet, (14 September 1884 – 14 November 1976) was a senior British Army officer who served in both World Wars. In the Second World War he was General Officer Commanding Anti-Aircraft Command, one ...

, commander of Anti-Aircraft Command

Anti-Aircraft Command (AA Command, or "Ack-Ack Command") was a British Army command of the Second World War that controlled the Territorial Army anti-aircraft artillery and searchlight formations and units defending the United Kingdom.

Origin

...

, studied the problem and proposed that enough anti-aircraft gun