Ulf Merbold on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ulf Dietrich Merbold (born June 20, 1941) is a German physicist and astronaut who flew to space three times, becoming the first

Merbold first flew to space on the STS-9 mission, which was also called Spacelab-1, aboard Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. The mission's launch was planned for September 30, 1983, but this was postponed because of because of issues with a communications satellite. A second launch date was set for October 29, 1983, but was again postponed after problems with the exhaust nozzle on the right

Merbold first flew to space on the STS-9 mission, which was also called Spacelab-1, aboard Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. The mission's launch was planned for September 30, 1983, but this was postponed because of because of issues with a communications satellite. A second launch date was set for October 29, 1983, but was again postponed after problems with the exhaust nozzle on the right  During the mission, the shuttle crew worked in groups of three in 12-hour shifts, with a "red team" consisting of Young, Parker and Merbold, and a "blue team" with the other three astronauts. The "red team" worked from 9:00p.m. to 9:00a.m. EST. Young usually worked on the flight deck, and Merbold and Parker in the Spacelab. Merbold and Young became good friends. On the mission's first day, approximately three hours after takeoff and after the

During the mission, the shuttle crew worked in groups of three in 12-hour shifts, with a "red team" consisting of Young, Parker and Merbold, and a "blue team" with the other three astronauts. The "red team" worked from 9:00p.m. to 9:00a.m. EST. Young usually worked on the flight deck, and Merbold and Parker in the Spacelab. Merbold and Young became good friends. On the mission's first day, approximately three hours after takeoff and after the  On one of the last days in orbit, Young, Lichtenberg and Merbold took part in an international, televised press conference that included US president

On one of the last days in orbit, Young, Lichtenberg and Merbold took part in an international, televised press conference that included US president

In June 1989, Ulf Merbold was chosen to train as payload specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-1) Spacelab mission.

In June 1989, Ulf Merbold was chosen to train as payload specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-1) Spacelab mission.

In November 1992, ESA decided to start cooperating with Russia on human spaceflight. The aim of this collaboration was to gain experience in long-duration spaceflights, which were not possible with NASA at the time, and to prepare for the construction of the Columbus module of the ISS. On May 7, 1993, Merbold and the Spanish astronaut

In November 1992, ESA decided to start cooperating with Russia on human spaceflight. The aim of this collaboration was to gain experience in long-duration spaceflights, which were not possible with NASA at the time, and to prepare for the construction of the Columbus module of the ISS. On May 7, 1993, Merbold and the Spanish astronaut  During his three spaceflights—the most of any German national—Merbold has spent 49 days in space.

During his three spaceflights—the most of any German national—Merbold has spent 49 days in space.

Since 1969, Ulf Merbold has been married to Birgit, and the couple have two children, a daughter born in 1975 and a son born in 1979. They live in Stuttgart.

In 1984, Merbold met the East-German cosmonaut

Since 1969, Ulf Merbold has been married to Birgit, and the couple have two children, a daughter born in 1975 and a son born in 1979. They live in Stuttgart.

In 1984, Merbold met the East-German cosmonaut

ESA biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Merbold, Ulf 1941 births Living people German astronauts European amateur radio operators Officers Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Members of the Order of Merit of North Rhine-Westphalia Recipients of the Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg Space Shuttle program astronauts Mir crew members

West German

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

citizen in space and the first non-American to fly on a NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

spacecraft. Merbold flew on two Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. Its official program na ...

missions and on a Russian mission to the space station ''Mir

''Mir'' (russian: Мир, ; ) was a space station that operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, operated by the Soviet Union and later by Russia. ''Mir'' was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to&n ...

'', spending a total of 49 days in space.

Merbold's father was imprisoned in NKVD special camp Nr. 2 by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

in 1945 and died there in 1948, and Merbold was brought up in the town of Greiz

Greiz () is a town in the state of Thuringia, Germany, and is the capital of the district of Greiz. Greiz is situated in eastern Thuringia, east of state capital Jena, on the river ''White Elster''.

Greiz has a large park in its center (Fürstl ...

in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

by his mother and grandparents. As he was not allowed to attend university in East Germany, he left for West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

in 1960, planning to study physics there. After the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (german: Berliner Mauer, ) was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). Construction of the Berlin Wall was commenced by the government ...

was built in 1961, he moved to Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

, West Germany. In 1968, he graduated from the University of Stuttgart

The University of Stuttgart (german: Universität Stuttgart) is a leading research university located in Stuttgart, Germany. It was founded in 1829 and is organized into 10 faculties. It is one of the oldest technical universities in Germany wit ...

with a diploma in physics, and in 1976 he gained a doctorate with a dissertation about the effect of radiation on iron. He then joined the staff at the Max Planck Institute for Metals Research

Founded on 18 March 2011, the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS) is one of the 86 research institutes of the Max Planck Society. With locations in Stuttgart and Tübingen, it combines interdisciplinary research in the growing ...

.

In 1977, Merbold successfully applied to the European Space Agency

, owners =

, headquarters = Paris, Île-de-France, France

, coordinates =

, spaceport = Guiana Space Centre

, seal = File:ESA emblem seal.png

, seal_size = 130px

, image = Views in the Main Control Room (1205 ...

(ESA) to become one of their first astronauts. He started astronaut training with NASA in 1978. In 1983, Merbold flew to space for the first time as a payload specialist or science astronaut on the first Spacelab

Spacelab was a reusable laboratory developed by European Space Agency (ESA) and used on certain spaceflights flown by the Space Shuttle. The laboratory comprised multiple components, including a pressurized module, an unpressurized carrier, ...

mission, STS-9, aboard the Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. He performed experiments in materials science and on the effects of microgravity

The term micro-g environment (also μg, often referred to by the term microgravity) is more or less synonymous with the terms ''weightlessness'' and ''zero-g'', but emphasising that g-forces are never exactly zero—just very small (on the I ...

on humans. In 1989, Merbold was selected as payload specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1) Spacelab mission STS-42

STS-42 was a NASA Space Shuttle ''Discovery'' mission with the Spacelab module. Liftoff was originally scheduled for 8:45 EST (13:45 UTC) on January 22, 1992, but the launch was delayed due to weather constraints. ''Discovery'' successfully ...

, which launched in January 1992 on the Space Shuttle ''Discovery''. Again, he mainly performed experiments in life sciences and materials science in microgravity. After ESA decided to cooperate with Russia, Merbold was chosen as one of the astronauts for the joint ESA–Russian Euromir

Euromir was an international space programme in the 1990s. Between the Russian Federal Space Agency and the European Space Agency (ESA), it would bring European astronauts to the Mir space station.

Euromir was part of a drive in the early 1990 ...

missions and received training at the Russian Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center

The Yuri A. Gagarin State Scientific Research-and-Testing Cosmonaut Training Center (GCTC; Russian: Центр подготовки космонавтов имени Ю. А. Гагарина) is a Russian training facility responsible for train ...

. He flew to space for the third and last time in October 1994, spending a month working on experiments on the Mir space station.

Between his space flights, Merbold provided ground-based support for other ESA missions. For the German Spacelab mission Spacelab D-1, he served as backup astronaut and as crew interface coordinator. For the second German Spacelab mission D-2 in 1993, Merbold served as science coordinator. Merbold's responsibilities for ESA included work at the European Space Research and Technology Centre

The European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) is the European Space Agency's main technology development and test centre for spacecraft and space technology. It is situated in Noordwijk, South Holland, in the western Netherlands, altho ...

on the ''Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

'' program and service as head of the German Aerospace Center

The German Aerospace Center (german: Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V., abbreviated DLR, literally ''German Center for Air- and Space-flight'') is the national center for aerospace, energy and transportation research of Germany ...

's astronaut office. He continued working for ESA until his retirement in 2004.

Early life and education

Ulf Merbold was born inGreiz

Greiz () is a town in the state of Thuringia, Germany, and is the capital of the district of Greiz. Greiz is situated in eastern Thuringia, east of state capital Jena, on the river ''White Elster''.

Greiz has a large park in its center (Fürstl ...

, in the Vogtland

Vogtland (; cz, Fojtsko) is a region spanning the German states of Bavaria, Saxony and Thuringia and north-western Bohemia in the Czech Republic. It overlaps with and is largely contained within Euregio Egrensis. The name alludes to the former ...

area of Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and larg ...

, Germany, on June 20, 1941. He was the only child of two teachers who lived in the school building of , a small village. During World War II, Ulf's father Herbert Merbold was a soldier who was imprisoned and then released from an American prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

camp in 1945. Soon after, he was imprisoned by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

in NKVD special camp Nr. 2, where he died on February 23, 1948. Merbold's mother Hildegard was dismissed from her school by the Soviet zone authorities in 1945. She and her son moved to a house in , a suburb of Greiz, where Merbold grew up close to his maternal grandparents and his parental grandfather.

After graduating in 1960 from high school—now —in Greiz, Merbold wanted to study physics at the University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The un ...

. Because he had not joined the Free German Youth

The Free German Youth (german: Freie Deutsche Jugend; FDJ) is a youth movement in Germany. Formerly, it was the official youth movement of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Socialist Unity Party of Germany.

The organization was meant ...

, the youth organization of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East German ...

, he was not allowed to study in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

so he decided to go to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, and crossed into West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

by bicycle. He obtained a West German

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

high school diploma () in 1961, as West German universities did not accept the East German one, and intended to start studying in Berlin so he could occasionally see his mother.

When the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (german: Berliner Mauer, ) was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). Construction of the Berlin Wall was commenced by the government ...

was built on August 13, 1961, it became impossible for Ulf's mother to visit him. Merbold then moved to Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

, where he had an aunt, and started studying physics at the University of Stuttgart

The University of Stuttgart (german: Universität Stuttgart) is a leading research university located in Stuttgart, Germany. It was founded in 1829 and is organized into 10 faculties. It is one of the oldest technical universities in Germany wit ...

, graduating with a in 1968. He lived in a dormitory in a wing of Solitude Palace

Solitude Palace () is a Rococo '' schloss'' and hunting retreat commissioned by Charles Eugene, Duke of Württemberg. It was designed by and Philippe de La Guêpière, and constructed from 1764 to 1769. It is located on an elongated ridge betwee ...

. Thanks to an amnesty for people who had left East Germany, Merbold could again see his mother from late December 1964. In 1976, Merbold obtained a doctorate in natural sciences, also from the University of Stuttgart, with a dissertation titled on the effects of neutron radiation

Neutron radiation is a form of ionizing radiation that presents as free neutrons. Typical phenomena are nuclear fission or nuclear fusion causing the release of free neutrons, which then Neutron capture, react with Atomic nucleus, nuclei of other ...

on nitrogen-doped iron. After completing his doctorate, Merbold became a staff member at the Max Planck Institute for Metals Research

Founded on 18 March 2011, the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS) is one of the 86 research institutes of the Max Planck Society. With locations in Stuttgart and Tübingen, it combines interdisciplinary research in the growing ...

in Stuttgart, where he had held a scholarship from 1968. At the institute, he worked on solid-state and low-temperature physics, with a special focus on experiments regarding lattice defects in body-centered cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of ...

(bcc) materials.

Astronaut training

In 1973, NASA and theEuropean Space Research Organisation

The European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) was an international organisation founded by 10 European nations with the intention of jointly pursuing scientific research in space. It was founded in 1964. As an organisation ESRO was based on a ...

, a precursor organization of the European Space Agency

, owners =

, headquarters = Paris, Île-de-France, France

, coordinates =

, spaceport = Guiana Space Centre

, seal = File:ESA emblem seal.png

, seal_size = 130px

, image = Views in the Main Control Room (1205 ...

(ESA), agreed to build a scientific laboratory that would be carried on the Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. Its official program na ...

. The memorandum of understanding contained the suggestion the first flight of Spacelab

Spacelab was a reusable laboratory developed by European Space Agency (ESA) and used on certain spaceflights flown by the Space Shuttle. The laboratory comprised multiple components, including a pressurized module, an unpressurized carrier, ...

should have a European crew member on board. The West German contribution to Spacelab was 53.3% of the cost; 52.6% of the work contracts were carried out by West German companies, including the main contractor ERNO.

In March 1977, ESA issued an Announcement of Opportunity for future astronauts, and several thousand people applied. Fifty-three of these underwent an interview and assessment process that started in September 1977, and considered their skills in science and engineering as well as their physical health. Four of the applicants were chosen as ESA astronauts; these were Merbold, Italian Franco Malerba

Franco Egidio Malerba (born 10 October 1946 in Busalla, Metropolitan City of Genoa, Italy) is an Italian astronaut and Member of the European Parliament. He was the first citizen of Italy to travel to space. In 1994, he was elected to the Europea ...

, Swiss Claude Nicollier

Claude Nicollier (born 2 September 1944 in Vevey, Switzerland) is the first astronaut from Switzerland. He has flown on four Space Shuttle missions. His first spaceflight ( STS-46) was in 1992, and his final spaceflight (STS-103) was in 1999. He ...

and Dutch Wubbo Ockels

Wubbo Johannes Ockels (28 March 1946 – 18 May 2014) was a Dutch physicist and astronaut with the European Space Agency who, in 1985, became the first Dutch citizen in space when he flew on STS-61-A as a payload specialist. He later becam ...

. The French candidate Jean-Loup Chrétien

Jean-Loup Jacques Marie Chrétien (born 20 August 1938) is a French retired ''Général de Brigade'' (brigadier general) in the ''Armée de l'Air'' (French air force), and a former CNES spationaut. He flew on two Franco-Soviet space missions a ...

was not selected, angering the President of France. Chrétien participated in the Soviet-French Soyuz T-6

Soyuz T-6 was a human spaceflight to Earth orbit to the Salyut 7 space station in 1982. Along with two Soviet cosmonauts, the crew included a Frenchman, Jean-Loup Chrétien.

The Soyuz-T spacecraft arrived at Salyut 7 following launch on 24 June ...

mission in June 1982, becoming the first West European in space. In 1978, Merbold, Nicollier and Ockels went to Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 in ...

for NASA training at Johnson Space Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight control are conducted. It was renamed in honor of the late U ...

while Malerba stayed in Europe.

NASA first discussed the concept of having payload specialists aboard spaceflights in 1972, and payload specialists were first used on Spacelab's initial flight. Payload specialists did not have to meet the strict NASA requirements for mission specialists. The first Spacelab mission had been planned for 1980 or 1981 but was postponed until 1983; Nicollier and Ockels took advantage of this delay to complete mission specialist training. Merbold did not meet NASA's medical requirements due to a ureter stone he had in 1959, and he remained a payload specialist. Rather than training with NASA, Merbold started flight training for instrument rating

Instrument rating refers to the qualifications that a pilot must have in order to fly under instrument flight rules (IFR). It requires specific training and instruction beyond what is required for a private pilot certificate or commercial pilot ce ...

at a flight school at Cologne Bonn Airport

Cologne Bonn Airport (german: Flughafen Köln/Bonn 'Konrad Adenauer') is the international airport of Germany's fourth-largest city Cologne, and also serves Bonn, former capital of West Germany. With around 12.4 million passengers passing throu ...

and worked with several organizations to prepare experiments for Spacelab.

In 1982, the crew for the first Spacelab flight was finalized, with Merbold as primary ESA payload specialist and Ockels as his backup. NASA chose Byron K. Lichtenberg and his backup Michael Lampton

Michael Logan Lampton (born March 1, 1941) is an American astronaut, founder of the optical ray tracing companStellar Software and known for his paper on electroacoustics with Susan M Lea, ''The theory of maximally flat loudspeaker systems''.

P ...

. The payload specialists started their training at Marshall Space Flight Center

The George C. Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), located in Redstone Arsenal, Alabama (Huntsville postal address), is the U.S. government's civilian rocketry and spacecraft propulsion research center. As the largest NASA center, MSFC's first ...

in August 1978, and then traveled to laboratories in several countries, where they learned the background of the planned experiments and how to operate the experimental equipment. The mission specialists were Owen Garriott

Owen Kay Garriott (November 22, 1930 – April 15, 2019) was an American electrical engineer and NASA astronaut, who spent 60 days aboard the Skylab space station in 1973 during the Skylab 3 mission, and 10 days aboard Spacelab-1 on a Spac ...

and Robert A. Parker, and the flight crew John Young John Young may refer to:

Academics

* John Young (professor of Greek) (died 1820), Scottish professor of Greek at the University of Glasgow

* John C. Young (college president) (1803–1857), American educator, pastor, and president of Centre Col ...

and Brewster Shaw

Brewster Hopkinson Shaw Jr. (born May 16, 1945) is a retired NASA astronaut, U.S. Air Force Colonel (United States), colonel, and former executive at Boeing. Shaw was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame on May 6, 2006.

Shaw is a vetera ...

. In January 1982, the mission and payload specialists started training at Marshall Space Flight Center on a Spacelab simulator. Some of the training took place at the German Aerospace Center

The German Aerospace Center (german: Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V., abbreviated DLR, literally ''German Center for Air- and Space-flight'') is the national center for aerospace, energy and transportation research of Germany ...

in Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

and at Kennedy Space Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten field centers. Since December 1968 ...

. While Merbold was made very welcome at Marshall, many of the staff at Johnson Space Center were opposed to payload specialists, and Merbold felt like an intruder there. Although payload specialists were not supposed to train on the Northrop T-38 Talon

The Northrop T-38 Talon is a two-seat, twinjet supersonic jet trainer. It was the world's first, and the most produced, supersonic trainer. The T-38 remains in service in several air forces.

The United States Air Force (USAF) operates the most ...

jet, Young took Merbold on a flight and allowed him to fly the plane.

STS-9 Space Shuttle mission

Merbold first flew to space on the STS-9 mission, which was also called Spacelab-1, aboard Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. The mission's launch was planned for September 30, 1983, but this was postponed because of because of issues with a communications satellite. A second launch date was set for October 29, 1983, but was again postponed after problems with the exhaust nozzle on the right

Merbold first flew to space on the STS-9 mission, which was also called Spacelab-1, aboard Space Shuttle ''Columbia''. The mission's launch was planned for September 30, 1983, but this was postponed because of because of issues with a communications satellite. A second launch date was set for October 29, 1983, but was again postponed after problems with the exhaust nozzle on the right solid rocket booster

A solid rocket booster (SRB) is a large solid propellant motor used to provide thrust in spacecraft launches from initial launch through the first ascent. Many launch vehicles, including the Atlas V, SLS and space shuttle, have used SRBs to give ...

. After repairs, the shuttle returned to the launch pad on November 8, 1983, and was launched from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A

Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) is the first of Launch Complex 39's three launch pads, located at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida. The pad, along with Launch Complex 39B, were first designed for the Saturn V launch vehicle. Ty ...

at 11:00a.m. EST on November 28, 1983. Merbold became the first non-US citizen to fly on a NASA space mission and also the first West German citizen in space. The mission was the first six-person spaceflight.

During the mission, the shuttle crew worked in groups of three in 12-hour shifts, with a "red team" consisting of Young, Parker and Merbold, and a "blue team" with the other three astronauts. The "red team" worked from 9:00p.m. to 9:00a.m. EST. Young usually worked on the flight deck, and Merbold and Parker in the Spacelab. Merbold and Young became good friends. On the mission's first day, approximately three hours after takeoff and after the

During the mission, the shuttle crew worked in groups of three in 12-hour shifts, with a "red team" consisting of Young, Parker and Merbold, and a "blue team" with the other three astronauts. The "red team" worked from 9:00p.m. to 9:00a.m. EST. Young usually worked on the flight deck, and Merbold and Parker in the Spacelab. Merbold and Young became good friends. On the mission's first day, approximately three hours after takeoff and after the orbiter

A spacecraft is a vehicle or machine designed to fly in outer space. A type of artificial satellite, spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, pl ...

's payload bay doors had been opened, the crew attempted to open the hatch leading to Spacelab. At first, Garriott and Merbold could not open the jammed hatch; the entire crew took turns trying to open it without applying significant force, which might damage the door. They opened the hatch after 15 minutes.

The Spacelab mission included about 70 experiments, many of which involved fluids and materials in a microgravity environment. The astronauts were subjects of a study on the effects of the environment in orbit on humans; these included experiments aiming to understand space adaptation syndrome, of which three of the four scientific crew members displayed some symptoms. Following NASA policy, it was not made public which astronaut had developed space sickness. Merbold later commented he had vomited twice but felt much better afterwards. Merbold repaired a faulty mirror heating facility, allowing some materials science experiments to continue. The mission's success in gathering results, and the crew's low consumption of energy and cryogenic fuel, led to a one-day mission extension from nine days to ten.

On one of the last days in orbit, Young, Lichtenberg and Merbold took part in an international, televised press conference that included US president

On one of the last days in orbit, Young, Lichtenberg and Merbold took part in an international, televised press conference that included US president Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

in Washington, DC, and the Chancellor of Germany Helmut Kohl

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (; 3 April 1930 – 16 June 2017) was a German politician who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998 and Leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998. Kohl's 16-year tenure is the longes ...

, who was at a European economic summit meeting in Athens, Greece

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

. During the telecast, which Reagan described as "one heck of a conference call", Merbold gave a tour of Spacelab and showed Europe from space while mentioning (the beauty of the earth). Merbold spoke to Kohl in German, and showed the shuttle's experiments to Kohl and Reagan, pointing out the possible importance of the materials-science experiments from Germany.

When the crew prepared for the return to earth, around five hours before the planned landing, two of the five onboard computers and one of three inertial measurement units malfunctioned, and the return was delayed by several orbits. ''Columbia'' landed at Edwards Air Force Base

Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force installation in California. Most of the base sits in Kern County, but its eastern end is in San Bernardino County and a southern arm is in Los Angeles County. The hub of the base is E ...

(AFB) at 6:47p.m. EST on December 8, 1983. Just before the landing, a leak of hydrazine

Hydrazine is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a simple pnictogen hydride, and is a colourless flammable liquid with an ammonia-like odour. Hydrazine is highly toxic unless handled in solution as, for example, hydrazine ...

fuel caused a fire in the aft section. After the return to earth, Merbold compared the experience of standing up and walking again to walking on a ship rolling in a storm. The four scientific crew members spent the week after landing doing extensive physiological experiments, many of them comparing their post-flight responses to those in microgravity. After landing, Merbold was enthusiastic about the mission and the post-flight experiments.

Ground-based astronaut work

In 1984, Ulf Merbold became the backup payload specialist for the Spacelab D-1 mission, which West Germany funded. The mission, which was numbered STS-61-A, was carried out on the Space Shuttle ''Challenger'' from October 30 to November 6, 1985. In ESA parlance, Merbold and the three other payload specialists—Germans Reinhard Furrer andErnst Messerschmid

Ernst Willi Messerschmid (born 21 May 1945) is a German physicist and former astronaut.

Born in Reutlingen, Germany, Messerschmid finished the ''Technisches Gymnasium'' in Stuttgart in 1965. After two years of military service he studied physics ...

and the Dutch Wubbo Ockels—were called "science astronauts" to distinguish them from "passengers" like Saudi prince Sultan bin Salman Al Saud

Sultan bin Salman Al Saud ( ar, سلطان بن سلمان آل سعود; ''Sulṭān bin Salmān Āl Suʿūd''; born 27 June 1956) is a Saudi prince and former Royal Saudi Air Force pilot who flew aboard the American STS-51-G Space Shuttle missi ...

and Utah senator Jake Garn

Edwin Jacob "Jake" Garn (born October 12, 1932) is an American politician and member of the Republican Party who served as a United States senator representing Utah from 1974 to 1993. Garn became the first sitting member of Congress to fly in sp ...

, both of whom had also flown as payload specialists on the Space Shuttle. During the Spacelab mission, Merbold acted as crew interface coordinator, working from the German Space Operations Center

The German Space Operations Center (GSOC; german: Deutsches Raumfahrt-Kontrollzentrum) is the mission control center of German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Oberpfaffenhofen near Munich, Germany.

Tasks

The GSOC performs the following tasks i ...

in Oberpfaffenhofen

Oberpfaffenhofen is a village that is part of the municipality of Weßling in the district of Starnberg, Bavaria, Germany. It is located about from the city center of Munich.

Village

The village is home to the Oberpfaffenhofen Airport and a m ...

to support the astronauts on board while working with the scientists on the ground.

From 1986, Merbold worked for ESA at the European Space Research and Technology Centre

The European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) is the European Space Agency's main technology development and test centre for spacecraft and space technology. It is situated in Noordwijk, South Holland, in the western Netherlands, altho ...

in Noordwijk

Noordwijk () is a town and municipality in the west of the Netherlands, in the province of South Holland. The municipality covers an area of of which is water and had a population of in .

On 1 January 2019, the former municipality of Noordwij ...

, Netherlands, contributing to plans for what would become the ''Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

'' module of the International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) is the largest modular space station currently in low Earth orbit. It is a multinational collaborative project involving five participating space agencies: NASA (United States), Roscosmos (Russia), JAXA ...

(ISS). In 1987, he became head of the German Aerospace Center's astronaut office, and in April–May 1993 he served as science coordinator for the second German Spacelab mission D-2 on STS-55

STS-55, or Deutschland 2 (D-2), was the 55th overall flight of the NASA Space Shuttle and the 14th flight of Shuttle '' Columbia''. This flight was a multinational Spacelab flight involving 88 experiments from eleven different nations. The expe ...

.

STS-42 Space Shuttle mission

In June 1989, Ulf Merbold was chosen to train as payload specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-1) Spacelab mission.

In June 1989, Ulf Merbold was chosen to train as payload specialist for the International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-1) Spacelab mission. STS-42

STS-42 was a NASA Space Shuttle ''Discovery'' mission with the Spacelab module. Liftoff was originally scheduled for 8:45 EST (13:45 UTC) on January 22, 1992, but the launch was delayed due to weather constraints. ''Discovery'' successfully ...

was intended to launch in December 1990 on ''Columbia'' but was delayed several times. After first being reassigned to launch with ''Atlantis'' in December 1991, it finally launched on the Space Shuttle ''Discovery'' on January 22, 1992, with a final one-hour delay to 9:52 a.m. EST caused by bad weather and issues with a hydrogen pump. The change from ''Columbia'' to ''Discovery'' meant the mission had to be shortened, as ''Columbia'' had been capable of carrying extra hydrogen and oxygen tanks that could power the fuel cells. Merbold was the first astronaut to represent reunified Germany. The other payload specialist on board was astronaut Roberta Bondar

Roberta Lynn Bondar (; born December 4, 1945) is a Canadian astronaut, neurologist and consultant. She is Canada's first female astronaut and the first neurologist in space.

After more than a decade as head of an international space medicine ...

, the first Canadian woman in space. Originally, Sonny Carter

Manley Lanier "Sonny" Carter Jr., Doctor of Medicine, M.D. (August 15, 1947 – April 5, 1991), (Captain (United States O-6), Capt, United States Navy, USN), was an American chemist, physician, professional soccer player, United States Navy, na ...

was assigned as one of three mission specialists, he died in a plane crash on April 5, 1991, and was replaced by David C. Hilmers

David Carl Hilmers, M.D. (born January 28, 1950) is a former NASA astronaut who flew four Space Shuttle missions. He was born in Clinton, Iowa, but considers DeWitt, Iowa, to be his hometown. He has two grown sons. His recreational interests in ...

.

The mission specialized in experiments in life sciences and materials science in microgravity. IML-1 included ESA's Biorack module, a biological research facility in which cells and small organisms could be exposed to weightlessness and cosmic radiation. It was used for microgravity experiments on various biological samples including frog eggs, fruit flies, and ''Physarum polycephalum

''Physarum polycephalum'', an acellular slime mold or myxomycete popularly known as "the blob", is a protist with diverse cellular forms and broad geographic distribution. The “acellular” moniker derives from the plasmodial stage of the li ...

'' slime molds. Bacteria, fungi and shrimp eggs were exposed to cosmic rays. Other experiments focused on the human response to weightlessness or crystal growth. There were also ten Getaway Special

Getaway Special was a NASA program that offered interested individuals, or groups, opportunities to fly small experiments aboard the Space Shuttle. Over the 20-year history of the program, over 170 individual missions were flown. The program, whi ...

canisters with experiments on board. Like STS-9, the mission operated in two teams who worked 12-hour shifts: a "blue team" consisting of mission commander Ronald J. Grabe together with Stephen S. Oswald, payload commander Norman Thagard

Norman Earl Thagard, M.D. (born July 3, 1943; Capt, USMC, Ret.), is an American scientist and former U.S. Marine Corps officer and naval aviator and NASA astronaut. He is the first American to ride to space on board a Russian vehicle, and ca ...

, and Bondar; and a "red team" of William F. Readdy, Hilmers, and Merbold. Because the crew did not use as many consumables as planned, the mission was extended from seven days to eight, landing at Edwards AFB on January 30, 1992, at 8:07 a.m. PST.

Euromir 94 mission

In November 1992, ESA decided to start cooperating with Russia on human spaceflight. The aim of this collaboration was to gain experience in long-duration spaceflights, which were not possible with NASA at the time, and to prepare for the construction of the Columbus module of the ISS. On May 7, 1993, Merbold and the Spanish astronaut

In November 1992, ESA decided to start cooperating with Russia on human spaceflight. The aim of this collaboration was to gain experience in long-duration spaceflights, which were not possible with NASA at the time, and to prepare for the construction of the Columbus module of the ISS. On May 7, 1993, Merbold and the Spanish astronaut Pedro Duque

Pedro Francisco Duque Duque, OF, OMSE (Madrid, 14 March 1963) is a Spanish astronaut and aeronautics engineer who served as Minister of Science of the Government of Spain from 2018 to 2021. He was also Member of the Congress of Deputies fro ...

were chosen as candidates to serve as the ESA astronaut on the first Euromir

Euromir was an international space programme in the 1990s. Between the Russian Federal Space Agency and the European Space Agency (ESA), it would bring European astronauts to the Mir space station.

Euromir was part of a drive in the early 1990 ...

mission, Euromir 94.

Along with other potential Euromir 95 astronauts, German Thomas Reiter

Thomas Arthur Reiter (born 23 May 1958 in Frankfurt, West Germany) is a retired European astronaut and is a Brigadier General in the German Air Force currently working as ESA Interagency Coordinator and Advisor to the Director General at the ...

and Swedish Christer Fuglesang

Arne Christer Fuglesang (born 18 March 1957) is a Swedish physicist and an ESA astronaut. He was first launched aboard the STS-116 Space Shuttle mission on 10 December 2006, making him the first Swedish citizen in space.

Married with three child ...

, in August 1993 Merbold and Duque began training at Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center

The Yuri A. Gagarin State Scientific Research-and-Testing Cosmonaut Training Center (GCTC; Russian: Центр подготовки космонавтов имени Ю. А. Гагарина) is a Russian training facility responsible for train ...

in Star City, Russia

Star City (russian: Звёздный городо́к, ''Zvyozdny gorodok''The name "Zvyozdny gorodok" literally means "starry townlet".) is a common name of an area in Zvyozdny gorodok, Moscow Oblast, Russia, which has since the 1960s been ...

, after completing preliminary training at the European Astronaut Centre

The European Astronaut Centre (EAC) (German: Europäisches Astronautenzentrum, French: Centre des astronautes européens), is an establishment of the European Space Agency and home of the European Astronaut Corps. It is near to Cologne, Germany ...

, Cologne. On May 30, 1994, it was announced Merbold would be the primary astronaut and Duque would serve as his backup. Equipment with a mass of for the mission was sent to Mir on the Progress M-24

Progress M-24 (russian: Прогресс М-24, italic=yes) was a Russian uncrewed cargo spacecraft which was launched in 1994 to resupply the Mir space station; causing minor damage to the station as the result of a collision during a failed attem ...

transporter, which failed to dock and collided with Mir on August 30, 1994, successfully docking only under manual control from Mir on September 2.

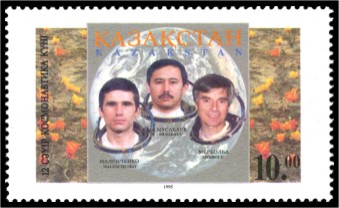

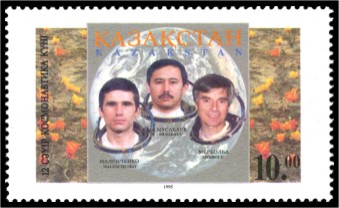

Merbold launched with commander Aleksandr Viktorenko

Aleksandr Stepanovich Viktorenko (; born 29 March 1947) is a Soviet/Russian cosmonaut.

He was selected as a cosmonaut on March 23, 1978, and retired on May 30, 1997. During his active career he had been Commander of Soyuz TM-3, Soyuz TM-8, So ...

and flight engineer Yelena Kondakova

Yelena Vladimirovna Kondakova (russian: link=no, Елена Владимировна Кондакóва; born March 30, 1957) is the third Soviet or Russian female cosmonaut to travel to space and the first woman to make a long-duration spaceflig ...

on Soyuz TM-20

Soyuz TM-20 was the twentieth expedition to the Russian Space Station Mir. It launched Russian cosmonauts Aleksandr Viktorenko, Yelena Kondakova, and German cosmonaut Ulf Merbold.

Crew

Mission highlights

The flight carried 10 kg of equi ...

on October 4, 1994, 1:42 a.m. Moscow time. Merbold became the second person to launch on both American and Russian spacecraft after cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev

Sergei Konstantinovich Krikalev (russian: Сергей Константинович Крикалёв, also transliterated as Sergei Krikalyov; born 27 August 1958) is a Russian mechanical engineer, former cosmonaut and former head of the Yuri Ga ...

, who had flown on Space Shuttle mission STS-60

STS-60 was the first mission of the U.S./Russian Shuttle-Mir Program, which carried Sergei K. Krikalev, the first Russian cosmonaut to fly aboard a Space Shuttle. The mission used NASA Space Shuttle ''Discovery'', which lifted off from Launc ...

in February 1994 after several Soviet and Russian spaceflights. During docking, the computer onboard Soyuz TM-20 malfunctioned but Viktorenko managed to dock manually. The cosmonauts then joined the existing Mir crew of Yuri Malenchenko

Yuri Ivanovich Malenchenko (russian: Юрий Иванович Маленченко; born December 22, 1961) is a retired Russian cosmonaut. Malenchenko became the first person to marry in space, on 10 August 2003, when he married Ekaterina Dmit ...

, Talgat Musabayev

Talgat Amangeldyuly Musabayev ( kk, Талғат Аманкелдіұлы Мұсабаев, ''Talğat Amankeldıūly Mūsabaev''; born 7 January 1951) is a Kazakh test pilot and former cosmonaut who flew on three spaceflights. His first two spa ...

and Valeri Polyakov

Valeri Vladimirovich Polyakov (russian: Валерий Владимирович Поляков, born Valeri Ivanovich Korshunov, russian: Валерий Иванович Коршунов, 27 April 1942 – 7 September 2022) was a Soviet and Rus ...

, expanding the crew to six people for 30 days.

Onboard Mir, Merbold performed 23 life sciences experiments, four materials science experiments, and other experiments. For one experiment designed to study the vestibular system

The vestibular system, in vertebrates, is a sensory system that creates the sense of balance and spatial orientation for the purpose of coordinating movement with balance. Together with the cochlea, a part of the auditory system, it constitutes ...

, Merbold wore a helmet that recorded his motion and his eye movements. On October 11, a power loss disrupted some of these experiments but power was restored after the station was reoriented to point the solar array toward the sun. The ground team rescheduled Merbold's experiments but a malfunction of a Czech-built materials processing furnace caused five of them to be postponed until after Merbold's return to Earth. None of the experiments were damaged by the power outage.

Merbold's return flight with Malechenko and Musabayev on Soyuz TM-19

Soyuz TM-19 was a crewed Soyuz spaceflight to Mir. It launched on 1 July 1994, at 12:24:50 UTC.

Crew

Mission highlights

Commander Malenchenko and Flight Engineer Musabayev, both spaceflight rookies, were to have been launched with veteran cos ...

was delayed by one day to experiment with the automated docking system that had failed on the Progress transporter. The test was successful and on November 4, Soyuz TM-19 de-orbited, carrying the three cosmonauts and of Merbold's samples from the biological experiments, with the remainder to return later on the Space Shuttle. The STS-71 mission was also supposed to return a bag containing science videotapes created by Merbold but this bag was lost. The landing of Soyuz TM-19 was rough; the cabin was blown off-course by and bounced after hitting the ground. None of the crew were hurt during landing.

During his three spaceflights—the most of any German national—Merbold has spent 49 days in space.

During his three spaceflights—the most of any German national—Merbold has spent 49 days in space.

Later career

In January 1995, shortly after the Euromir mission, Merbold became head of the astronaut department of the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne. From 1999 to 2004, Merbold worked in the Microgravity Promotion Division of the ESA Directorate of Manned Spaceflight and Microgravity in Noordwijk, where his task was to spread awareness of the opportunities provided by the ISS among European research and industry organizations. He retired on July 30, 2004, but has continued to do consulting work for ESA and give lectures.Personal life

Since 1969, Ulf Merbold has been married to Birgit, and the couple have two children, a daughter born in 1975 and a son born in 1979. They live in Stuttgart.

In 1984, Merbold met the East-German cosmonaut

Since 1969, Ulf Merbold has been married to Birgit, and the couple have two children, a daughter born in 1975 and a son born in 1979. They live in Stuttgart.

In 1984, Merbold met the East-German cosmonaut Sigmund Jähn

Sigmund Werner Paul Jähn (; 13 February 1937 – 21 September 2019) was a German cosmonaut and pilot who in 1978 became the first German to fly into space as part of the Soviet Union's Interkosmos programme.

Early life

Jähn was born on 13 Fe ...

, who had become the first German in space after launching on August 26, 1978, on Soyuz 31. They both were born in the Vogtland (Jähn was born in Morgenröthe-Rautenkranz

Morgenröthe-Rautenkranz is a village and a former municipality in the Vogtlandkreis district, in Saxony, Germany. Since 1 October 2009, along with Tannenbergsthal and Hammerbrücke, it is part of the municipality Muldenhammer.

Personalities

*Sig ...

) and grew up in East Germany. Jähn and Merbold became founding members of the Association of Space Explorers

The Association of Space Explorers is a non-profit organization with a membership composed of people who have completed at least one Earth orbit in space (above , as defined by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. It was founded in 1985, ...

in 1985. Jähn helped Merbold's mother, who had moved to Stuttgart, to obtain a permit for a vacation in East Germany. After German reunification

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

, Merbold helped Jähn become a freelance consultant for the German Aerospace Center. At the time of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall (german: Mauerfall) on 9 November 1989, during the Peaceful Revolution, was a pivotal event in world history which marked the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the figurative Iron Curtain and one of the series of eve ...

, they were at an astronaut conference in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

together.

In his spare time Merbold enjoys playing the piano and skiing. He also flies planes including gliders. Holding a commercial pilot license A commercial pilot licence (CPL) is a type of pilot licence that permits the holder to act as a pilot of an aircraft and be paid for their work.

Different licenses are issued for the major aircraft categories: airplanes, airships, balloons, glid ...

, he has over 3,000 hours of flight experience as a pilot. On his 79th birthday, he inaugurated the new runway at the airfield, landing with his wife in a Piper Seneca II.

Awards and honors

In 1983, Merbold received theAmerican Astronautical Society

Formed in 1954, the American Astronautical Society (AAS) is an independent scientific and technical group in the United States dedicated to the advancement of space science and space exploration. AAS supports NASA's Vision for Space Exploration ...

's Flight Achievement Award, together with the rest of the STS-9 crew. He was also awarded the Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg

Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg (german: link=no, Verdienstorden des Landes Baden-Württemberg) is the highest award of the German State of Baden-Württemberg. Established 26 November 1974, it was originally called the Medal of Merit of Bad ...

in December 1983. In 1984, he was awarded the Haley Astronautics Award by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) is a professional society for the field of aerospace engineering. The AIAA is the U.S. representative on the International Astronautical Federation and the International Council of ...

and the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

The Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: Verdienstorden der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, or , BVO) is the only federal decoration of Germany. It is awarded for special achievements in political, economic, cultural, intellect ...

(first class). In 1988, he was awarded the Order of Merit of North Rhine-Westphalia

The Order of Merit of North Rhine-Westphalia (german: Verdienstorden des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen) is a civil order of merit, of the German State of North Rhine-Westphalia. The Order of Merit of North Rhine-Westphalia was founded on 11 March 1 ...

. Merbold received the Russian Order of Friendship

The Order of Friendship (russian: Орден Дружбы, ') is a state decoration of the Russian Federation established by Boris Yeltsin by presidential decree 442 of 2 March 1994 to reward Russian and foreign nationals whose work, deeds a ...

in November 1994, the Kazakh Order of Parasat

The Order of Parasat ( kk, Парасат ордені, ''Parasat ordeni''; the Order of Nobility) is an order awarded by the government of Kazakhstan. It was established in 1993.

The order is awarded to notable figures in the fields of science, ...

in January 1995 and the Russian Medal "For Merit in Space Exploration"

The Medal "For Merit in Space Exploration" (russian: Медаль "За заслуги в освоении космоса") is a state decoration of the Russian Federation aimed at recognising achievements in the space program. It was established ...

in April 2011. In 1995, he received an honorary doctorate in engineering from RWTH Aachen University

RWTH Aachen University (), also known as North Rhine-Westphalia Technical University of Aachen, Rhine-Westphalia Technical University of Aachen, Technical University of Aachen, University of Aachen, or ''Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hoch ...

.

In 2008, the asteroid 10972 Merbold was named after him.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

ESA biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Merbold, Ulf 1941 births Living people German astronauts European amateur radio operators Officers Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Members of the Order of Merit of North Rhine-Westphalia Recipients of the Order of Merit of Baden-Württemberg Space Shuttle program astronauts Mir crew members