Utah ( , ) is a

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* '' Our ...

in the

Mountain West subregion of the

Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

. Utah is a

landlocked

A landlocked country is a country that does not have territory connected to an ocean or whose coastlines lie on endorheic basins. There are currently 44 landlocked countries and 4 landlocked de facto states. Kazakhstan is the world's largest ...

U.S. state bordered to its east by

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

, to its northeast by

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the sou ...

, to its north by

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and W ...

, to its south by

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States. It is the list of U.S. states and territories by area, 6th largest and the list of U.S. states and territories by population, 14 ...

, and to its west by

Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

. Utah also touches

a corner of

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

in the southeast. Of the

fifty U.S. states, Utah is the

13th-largest by area; with a population over three million, it is the

30th-most-populous and

11th-least-densely populated. Urban development is mostly concentrated in two areas: the

Wasatch Front

The Wasatch Front is a metropolitan region in the north-central part of the U.S. state of Utah. It consists of a chain of contiguous cities and towns stretched along the Wasatch Range from approximately Provo in the south to Logan in the nort ...

in the north-central part of the state, which is home to roughly two-thirds of the population and includes the capital city,

Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the capital and most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in Utah. With a population of 200,133 in 2020, th ...

; and

Washington County in the southwest, with more than 180,000 residents. Most of the western half of Utah lies in the

Great Basin.

Utah has been inhabited for thousands of years by various

indigenous groups

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

such as the

ancient Puebloans, Navajo and Ute. The Spanish were the first Europeans to arrive in the mid-16th century, though the region's difficult geography and harsh climate made it a peripheral part of

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

and later Mexico. Even while it was Mexican territory, many of Utah's earliest settlers were American, particularly Mormons fleeing marginalization and persecution from the United States. Following the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

in 1848, the region was

annexed by the U.S., becoming part of the

Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th sta ...

, which included what is now Colorado and Nevada. Disputes between the dominant Mormon community and the federal government delayed Utah's admission as a state; only after the outlawing of polygamy was it admitted in 1896 as the

45th.

People from Utah are known as Utahns. Slightly over half of all Utahns are

Mormons

Mormons are a Religious denomination, religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the mov ...

, the vast majority of whom are members of

the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ...

(LDS Church), which has its world headquarters in Salt Lake City; Utah is the only state where a majority of the population belongs to a single church. The LDS Church greatly influences Utahn culture, politics, and daily life,

though since the 1990s the state has become more religiously diverse as well as secular.

Utah has a highly diversified economy, with major sectors including transportation, education, information technology and research, government services, mining, and tourism. Utah has been one of the fastest growing states since 2000, with the

2020 U.S. census

The United States census of 2020 was the twenty-fourth decennial United States census. Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2020. Other than a pilot study during the 2000 census, this was the first U.S. census to off ...

confirming the fastest population growth in the nation since 2010.

St. George

Saint George (Greek: Γεώργιος (Geórgios), Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldier ...

was the fastest-growing metropolitan area in the United States from 2000 to 2005. Utah ranks among the overall best states in metrics such as healthcare, governance, education, and infrastructure. It has the

14th-highest median average income and the

least income inequality of any U.S. state. Over time and influenced by

climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

,

drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

s in Utah have been increasing in frequency and severity, putting a further strain on Utah's

water security

Water security is the focused goal of water policy and water management. A society with a high level of water security makes the most of water's benefits for humans and ecosystems and limits the risk of destructive impacts associated with water. T ...

and impacting the state’s economy.

Etymology

The name ''Utah'' is said to derive from the name of the

Ute tribe

Ute () are the Indigenous people of the Ute tribe and culture among the Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. They had lived in sovereignty in the regions of present-day Utah and Colorado in the Southwestern United States for many centuries unt ...

, meaning 'people of the mountains'.

[Utah Quick Facts](_blank)

at Utah.gov However, no such word actually exists in the Utes' language, and the Utes refer to themselves as . The meaning of ''Utes'' as 'the mountain people' has been attributed to the neighboring Pueblo Indians, as well as to the

Apache word , which means 'one that is higher up' or 'those that are higher up'.

In

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

** Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Ca ...

it was pronounced ; subsequently English-speaking people may have adapted the word as ''Utah''.

History

Pre-Columbian

Thousands of years before the arrival of European explorers, the

Ancestral Puebloans

The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, ...

and the

Fremont Fremont may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

*Fremont, California - largest city with the name

**Fremont station

**Fremont station (BART)

** Fremont Central Park

*Fremont, Yolo County, California

* Fremont, Illinois

*Fremont Center, Illin ...

people lived in what is now known as Utah, some of which spoke languages of the

Uto-Aztecan

Uto-Aztecan, Uto-Aztekan or (rarely in English) Uto-Nahuatl is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over thirty languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The na ...

group. Ancestral Pueblo peoples built their homes through

excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

in mountains, and the Fremont people built houses of straw before disappearing from the region around the 15th century.

Another group of Native Americans, the

Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest fe ...

, settled in the region around the 18th century. In the mid-18th century, other Uto-Aztecan tribes, including the

Goshute

The Goshutes are a tribe of Western Shoshone Native Americans. There are two federally recognized Goshute tribes today:

* Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, located in Nevada and Utah

* Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians of Ut ...

, the

Paiute

Paiute (; also Piute) refers to three non-contiguous groups of indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. Although their languages are related within the Numic group of Uto-Aztecan languages, these three groups do not form a single set. The term "Pa ...

, the

Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshone: southern Idaho

* Western Shoshone: Nevada, northern Utah

* Goshute: western Utah, e ...

, and the Ute people, also settled in the region. These five groups were present when the first European explorers arrived.

Spanish exploration (1540)

The southern Utah region was explored by the Spanish in 1540, led by

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y Luján (; 1510 – 22 September 1554) was a Spanish conquistador and explorer who led a large expedition from what is now Mexico to present-day Kansas through parts of the southwestern United States between ...

, while looking for the legendary

Cíbola. A group led by two Catholic priests—sometimes called the

Domínguez–Escalante expedition

The Domínguez–Escalante Expedition was a Spanish journey of exploration conducted in 1776 by two Franciscan priests, Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, to find an overland route from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to their Roman Ca ...

—left

Santa Fe in 1776, hoping to find a route to the coast of California. The expedition traveled as far north as

Utah Lake

Utah Lake is a shallow freshwater lake in the center of Utah County, Utah, Utah County, Utah, United States. It lies in Utah Valley, surrounded by the Provo, Utah, Provo-Orem, Utah, Orem metropolitan area. The lake's only river outlet, the Jordan ...

and encountered the native residents. The Spanish made further explorations in the region but were not interested in colonizing the area because of its desert nature. In 1821, the year Mexico achieved its independence from Spain, the region became known as part of its territory of

Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

.

European trappers and

fur traders

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mo ...

explored some areas of Utah in the early 19th century from Canada and the United States. The city of

Provo, Utah, was named for one

Étienne Provost

Étienne Provost (1785 – 3 July 1850) was a Canadian fur trader whose trapping and trading activities in the American southwest preceded Mexican independence. He was also known as Proveau and Provot (and the pronunciation was "Pra-vo"). Leadi ...

, who visited the area in 1825. The city of

Ogden, Utah

Ogden is a city in and the county seat of Weber County, Utah, United States, approximately east of the Great Salt Lake and north of Salt Lake City. The population was 87,321 in 2020, according to the US Census Bureau, making it Utah's eighth ...

, was named after

Peter Skene Ogden

Peter Skene Ogden (alternately Skeene, Skein, or Skeen; baptised 12 February 1790 – 27 September 1854) was a British-Canadian fur trader and an early explorer of what is now British Columbia and the Western United States. During his many expedi ...

, a Canadian explorer who traded furs in the Weber Valley.

In late 1824,

Jim Bridger

James Felix "Jim" Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was known as Ol ...

became the first known English-speaking person to sight the

Great Salt Lake. Due to the high

salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

of its waters, he thought he had found the Pacific Ocean; he subsequently learned this body of water was a giant

salt lake

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per litre). ...

. After the discovery of the lake, hundreds of American and Canadian traders and trappers established trading posts in the region. In the 1830s, thousands of migrants traveling from the Eastern United States to the American West began to make stops in the region of the Great Salt Lake, then known as Lake Youta.

Latter Day Saint settlement (1847)

Following the

death of Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith, the founder and leader of the Latter Day Saint movement, and his brother, Hyrum Smith, were killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, United States, on June 27, 1844, while awaiting trial in the town jail.

As mayor of the city of ...

in 1844,

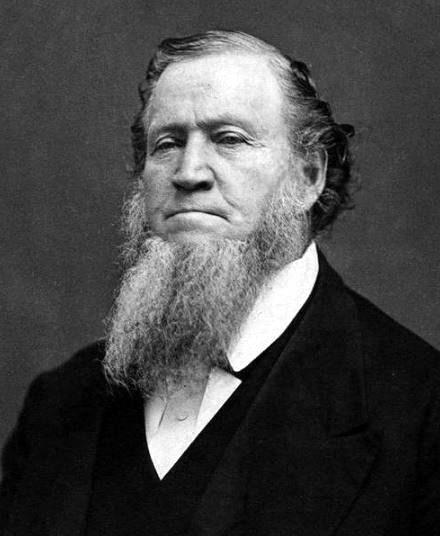

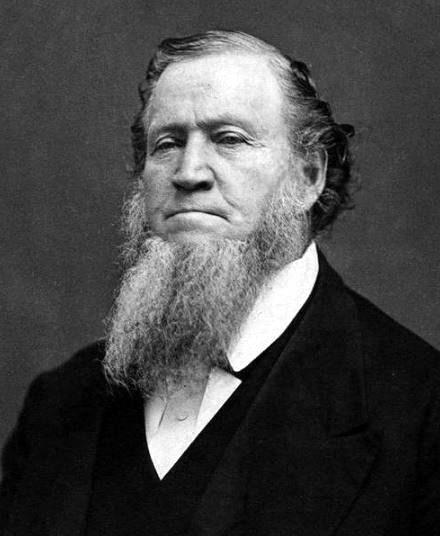

Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

, as president of the

Quorum of the Twelve

In the Latter Day Saint movement, the Quorum of the Twelve (also known as the Council of the Twelve, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Council of the Twelve Apostles, or the Twelve) is one of the governing bodies or ( quorums) of the church hie ...

, became the leader of the LDS Church in

Nauvoo, Illinois

Nauvoo ( ; from the ) is a small city in Hancock County, Illinois, United States, on the Mississippi River near Fort Madison, Iowa. The population of Nauvoo was 950 at the 2020 census. Nauvoo attracts visitors for its historic importance and its ...

. To address the growing conflicts between his people and their neighbors, Young agreed with Illinois Governor

Thomas Ford in October 1845 that the Mormons would leave by the following year.

Young and the first group of Mormon pioneers reached the

Salt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Sandy, South Jordan, West Jordan, and West Valley City; its total p ...

on July 24, 1847. Over the next 22 years, more than 70,000 pioneers crossed the plains and settled in Utah. For the first few years, Brigham Young and the thousands of early settlers of Salt Lake City struggled to survive. The arid desert land was deemed by the Mormons as desirable as a place where they could practice their religion without harassment.

Settlers buried thirty-six Native Americans in one grave after an outbreak of measles occurred during the winter of 1847.

The first group of settlers brought African slaves with them, making Utah the only place in the western United States to have African slavery. Three slaves, Green Flake, Hark Lay, and Oscar Crosby, came west with the first group of settlers in 1847. The settlers also began to purchase Indian slaves in the well-established Indian slave trade,

as well as enslaving Indian prisoners of war.

Utah was Mexican territory when the first pioneers arrived in 1847. Early in the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

in late 1846, the United States had taken control of

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

and California. The entire Southwest

became U.S. territory upon the signing of the

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

, February 2, 1848. The treaty was ratified by the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and ...

on March 11. Learning that California and New Mexico were applying for statehood, the settlers of the Utah area (originally having planned to petition for territorial status) applied for statehood with an ambitious plan for a

State of Deseret

The State of Deseret (modern pronunciation , contemporaneously ) was a proposed state of the United States, proposed in 1849 by settlers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in Salt Lake City. The provisional state ...

.

The Mormon settlements provided pioneers for other settlements in the West. Salt Lake City became the hub of a "far-flung commonwealth" of Mormon settlements. With new church converts coming from the East and around the world, Church leaders often assigned groups of church members as missionaries to establish other settlements throughout the West. They developed irrigation to support fairly large pioneer populations along Utah's Wasatch front (Salt Lake City, Bountiful and Weber Valley, and Provo and Utah Valley). Throughout the remainder of the 19th century, Mormon pioneers established hundreds of other settlements in Utah,

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and W ...

,

Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

,

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States. It is the list of U.S. states and territories by area, 6th largest and the list of U.S. states and territories by population, 14 ...

,

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the sou ...

,

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

,

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

, and

Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

—including in

Las Vegas, Nevada

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vega ...

;

Franklin, Idaho

Franklin is a city in Franklin County, Idaho, United States. The population was 641 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Logan, Utah-Idaho Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

The town was founded by Mormon pioneers led by Thomas S. Smart ...

(the first European settlement in Idaho);

San Bernardino, California

San Bernardino (; Spanish language, Spanish for Bernardino of Siena, "Saint Bernardino") is a city and county seat of San Bernardino County, California, United States. Located in the Inland Empire region of Southern California, the city had a ...

;

Mesa, Arizona

Mesa ( ) is a city in Maricopa County, in the U.S. state of Arizona. It is the most populous city in the East Valley section of the Phoenix Metropolitan Area. It is bordered by Tempe on the west, the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community ...

;

Star Valley, Wyoming

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by its gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night, but their immense distances from Earth mak ...

; and

Carson Valley, Nevada

Douglas County is a County (United States), county in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Nevada. As of th2020 Census the population was 49,488. Its county seat is Minden, Nevada, Minden. Douglas County comprises the Gardnerville Ranchos ...

.

Prominent settlements in Utah included

St. George

Saint George (Greek: Γεώργιος (Geórgios), Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldier ...

,

Logan

Logan may refer to:

Places

* Mount Logan (disambiguation)

Australia

* Logan (Queensland electoral district), an electoral district in the Queensland Legislative Assembly

* Logan, Victoria, small locality near St. Arnaud

* Logan City, local g ...

, and

Manti (where settlers completed the LDS Church's first three

temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

in Utah, each started after but finished many years before the larger and better known temple built in Salt Lake City was completed in 1893), as well as Parowan, Cedar City, Bluff, Moab, Vernal, Fillmore (which served as the territorial capital between 1850 and 1856), Nephi, Levan, Spanish Fork, Springville, Provo Bench (now

Orem

Orem is a city in Utah County, Utah, United States, in the northern part of the state. It is adjacent to Provo, Lindon, and Vineyard and is approximately south of Salt Lake City.

Orem is one of the principal cities of the Provo-Orem, Utah Me ...

), Pleasant Grove, American Fork, Lehi, Sandy, Murray, Jordan, Centerville, Farmington, Huntsville, Kaysville, Grantsville, Tooele, Roy, Brigham City, and many other smaller towns and settlements. Young had an expansionist's view of the territory that he and the Mormon pioneers were settling, calling it Deseret—which according to the

Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, which, according to Latter Day Saint theology, contains writings of ancient prophets who lived on the American continent from 600 BC to AD 421 and during an interlude ...

was an ancient word for "honeybee". This is symbolized by the beehive on the Utah flag, and the state's motto, "Industry".

Utah Territory (1850–1896)

The Utah Territory was much smaller than the proposed state of Deseret, but it still contained all of the present states of Nevada and Utah as well as pieces of modern Wyoming and

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

. It was created with the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican– ...

, and

Fillmore, named after President

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

, was designated the capital. The territory was given the name Utah after the Ute tribe of Native Americans. Salt Lake City replaced Fillmore as the territorial capital in 1856.

By 1850, there were around 100 black people in the territory, the majority of whom were slaves.

In Salt Lake County, 26 slaves were counted.

In 1852, the territorial legislature passed the

Act in Relation to Service

The Act in Relation to Service, which was passed on Feb 4, 1852 in the Utah Territory, made slavery legal in the territory. A similar law, Act for the relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners was passed on March 7, 1852, and specifically dealt ...

and the

Act for the relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners formally legalizing slavery in the territory. Slavery was abolished in the territory during the Civil War.

In 1850, Salt Lake City sent out a force known as the

Nauvoo Legion

The Nauvoo Legion was a state-authorized militia of the city of Nauvoo, Illinois, United States. With growing antagonism from surrounding settlements it came to have as its main function the defense of Nauvoo, and surrounding Latter Day Sain ...

and engaged the

Timpanogos

The Timpanogos (Timpanog, Utahs or Utah Indians) were a tribe of Native Americans who inhabited a large part of central Utah, in particular, the area from Utah Lake east to the Uinta Mountains and south into present-day Sanpete County.

Most Ti ...

in the

Battle at Fort Utah

The Battle at Fort Utah (also known as Fort Utah War or Provo War) was a battle between the Timpanogos Tribe and remnants of the Nauvoo Legion at Fort Utah in modern-day Provo, Utah. The Timpanogos people initially tolerated the presence of the se ...

.

Disputes between the Mormon inhabitants and the

U.S. government intensified due to the practice of

plural marriage

Polygamy (called plural marriage by Latter-day Saints in the 19th century or the Principle by modern fundamentalist practitioners of polygamy) was practiced by leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) for more th ...

, or

polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is marri ...

, among members of the LDS Church. The Mormons were still pushing for the establishment of a State of Deseret with the new borders of the Utah Territory. Most, if not all, of the members of the U.S. government opposed the polygamous practices of the Mormons.

Members of the LDS Church were viewed as un-American and rebellious when news of their polygamous practices spread. In 1857, particularly heinous accusations of abdication of government and general immorality were leveled by former associate justice William W. Drummond, among others. The detailed reports of life in Utah caused the administration of

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

to send a secret military "expedition" to Utah. When the supposed rebellion should be quelled,

Alfred Cumming would take the place of Brigham Young as territorial governor. The resulting conflict is known as the

Utah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US gov ...

, nicknamed "Buchanan's Blunder" by the Mormon leaders.

In September 1857, about 120 American settlers of the Baker–Fancher wagon train, en route to California from Arkansas, were murdered by

Utah Territorial Militia

The Utah Territorial Militia also known as the Nauvoo Legion was the territorial Militia for the United States Territory of Utah.

History

A predecessor known as the Nauvoo Legion was formed as a state-authorized militia of the city of Nau ...

and some

Paiute

Paiute (; also Piute) refers to three non-contiguous groups of indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. Although their languages are related within the Numic group of Uto-Aztecan languages, these three groups do not form a single set. The term "Pa ...

Native Americans in the

Mountain Meadows massacre

The Mountain Meadows Massacre (September 7–11, 1857) was a series of attacks during the Utah War that resulted in the mass murder of at least 120 members of the Baker–Fancher emigrant wagon train. The massacre occurred in the southern Ut ...

.

Before troops led by

Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

entered the territory, Brigham Young ordered all residents of Salt Lake City to evacuate southward to

Utah Valley

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

and sent out the Nauvoo Legion to delay the government's advance. Although wagons and supplies were burned, eventually the troops arrived in 1858, and Young surrendered official control to Cumming, although most subsequent commentators claim that Young retained true power in the territory. A steady stream of governors appointed by the president quit the position, often citing the traditions of their supposed territorial government. By agreement with Young, Johnston established

Camp Floyd

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

, away from Salt Lake City, to the southwest.

Salt Lake City was the last link of the

First Transcontinental Telegraph

The first transcontinental telegraph (completed October 24, 1861) was a line that connected the existing telegraph network in the eastern United States to a small network in California, by means of a link between Omaha, Nebraska and Carson Cit ...

, completed in October 1861. Brigham Young was among the first to send a message, along with

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and other officials.

Because of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

, federal troops were pulled out of Utah Territory in 1861. This was a boon to the local economy as the army sold everything in camp for pennies on the dollar before marching back east to join the war. The territory was then left in LDS hands until

Patrick E. Connor

Patrick Edward Connor (March 17, 1820Rodgers, 1938, p. 1 – December 17, 1891) was an American soldier who served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He is most notorious for his massacres against Native Americans during th ...

arrived with a regiment of California volunteers in 1862. Connor established

Fort Douglas

Camp Douglas was established in October 1862, during the American Civil War, as a small military garrison about three miles east of Salt Lake City, Utah, to protect the overland mail route and telegraph lines along the Central Overland Route. In ...

just east of Salt Lake City and encouraged his people to discover mineral deposits to bring more non-Mormons into the territory. Minerals were discovered in

Tooele County and miners began to flock to the territory.

Beginning in 1865,

Utah's Black Hawk War developed into the deadliest conflict in the territory's history. Chief

Antonga Black Hawk

Antonga, or Black Hawk (born c. 1830; died September 26, 1870), was a nineteenth-century war chief of the Timpanogos Tribe in what is the present-day state of Utah. He led the Timpanogos against Mormon settlers and gained alliances with Paiute ...

died in 1870, but fights continued to break out until additional federal troops were sent in to suppress the

Ghost Dance

The Ghost Dance ( Caddo: Nanissáanah, also called the Ghost Dance of 1890) was a ceremony incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka (renamed Jack Wil ...

of 1872. The war is unique among

Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

because it was a three-way conflict, with mounted Timpanogos

Utes led by Antonga Black Hawk fighting federal and LDS authorities.

On May 10, 1869, the

First transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

was completed at

Promontory Summit

Promontory is an area of high ground in Box Elder County, Utah, United States, 32 mi (51 km) west of Brigham City and 66 mi (106 km) northwest of Salt Lake City. Rising to an elevation of 4,902 feet (1,494 m) above sea ...

, north of the Great Salt Lake.

The railroad brought increasing numbers of people into the territory and several influential businesspeople made fortunes there.

During the 1870s and 1880s laws were passed to punish polygamists due, in part, to stories from Utah. Notably,

Ann Eliza Young

Ann Eliza Young (September 13, 1844 – December 7, 1917) also known as Ann Eliza Webb Dee Young Denning was one of Brigham Young's fifty-five wives and later a critic of polygamy. Her autobiography, ''Wife No. 19,'' was a recollection of her exp ...

—tenth wife to divorce Brigham Young, women's advocate, national lecturer and author of ''Wife No.19 or My Life of Bondage'' and Mr. and Mrs. Fanny Stenhouse, authors of ''The Rocky Mountain Saints'' (T. B. H. Stenhouse, 1873) and ''Tell It All: My Life in Mormonism'' (Fanny Stenhouse, 1875). Both Ann Eliza and Fanny testify to the happiness of the very early Church members before polygamy. They independently published their books in 1875. These books and the lectures of Ann Eliza Young have been credited with the United States Congress passage of anti-polygamy laws by newspapers throughout the United States as recorded in "The Ann Eliza Young Vindicator", a pamphlet which detailed Ms Young's travels and warm reception throughout her lecture tour.

T. B. H. Stenhouse, former Utah Mormon polygamist, Mormon missionary for thirteen years and a Salt Lake City newspaper owner, finally left Utah and wrote ''The Rocky Mountain Saints''. His book gives a witnessed account of life in Utah, both the good and the bad. He finally left Utah and Mormonism after financial ruin occurred when Brigham Young sent Stenhouse to relocate to Ogden, Utah, according to Stenhouse, to take over his thriving pro-Mormon ''Salt Lake Telegraph'' newspaper. In addition to these testimonies, ''The Confessions of John D. Lee'', written by John D. Lee—alleged "Scape goat" for the

Mountain Meadow Massacre—also came out in 1877. The corroborative testimonies coming out of Utah from Mormons and former Mormons influenced Congress and the people of the United States.

In the

1890 Manifesto

The 1890 Manifesto (also known as the Woodruff Manifesto, the Anti-polygamy Manifesto, or simply "the Manifesto") is a statement which officially advised against any future plural marriage in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS ...

, the LDS Church banned polygamy. When Utah applied for statehood again, it was accepted. One of the conditions for granting Utah statehood was that a ban on polygamy be written into the state constitution. This was a condition required of other western states that were admitted into the Union later. Statehood was officially granted on January 4, 1896.

20th century to present

Beginning in the early 20th century, with the establishment of such national parks as

Bryce Canyon National Park

Bryce Canyon National Park () is an American national park located in southwestern Utah. The major feature of the park is Bryce Canyon, which despite its name, is not a canyon, but a collection of giant natural amphitheaters along the eastern ...

and

Zion National Park

Zion National Park is an American national park located in southwestern Utah near the town of Springdale. Located at the junction of the Colorado Plateau, Great Basin, and Mojave Desert regions, the park has a unique geography and a variety o ...

, Utah became known for its natural beauty. Southern Utah became a popular filming spot for arid, rugged scenes featured in the popular mid-century western film genre. From such films, most US residents recognize such natural landmarks as

Delicate Arch

Delicate Arch is a freestanding natural arch located in Arches National Park, near Moab in Grand County, Utah, United States. The arch is the most widely recognized landmark in Arches National Park and is depicted on Utah license plates and a ...

and "the Mittens" of

Monument Valley

Monument Valley ( nv, Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii, , meaning ''valley of the rocks'') is a region of the Colorado Plateau characterized by a cluster of sandstone buttes, the largest reaching above the valley floor. It is located on the Utah-Arizona ...

. During the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, with the construction of the

Interstate highway

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. T ...

system, accessibility to the southern scenic areas was made easier.

Since the establishment of

Alta Ski Area

Alta is a ski area in the western United States, located in the town of Alta in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah, in Salt Lake County. With a skiable area of , Alta's base elevation is and rises to for a vertical gain of . One of the oldest sk ...

in 1939 and the subsequent

development of several ski resorts in the state's mountains, Utah's skiing has become world-renowned. The dry, powdery snow of the

Wasatch Range

The Wasatch Range ( ) or Wasatch Mountains is a mountain range in the western United States that runs about from the Utah-Idaho border south to central Utah. It is the western edge of the greater Rocky Mountains, and the eastern edge of the ...

is considered some of the best skiing in the world (the state license plate once claimed "the Greatest Snow on Earth"). Salt Lake City won the bid for the

2002 Winter Olympic Games

The 2002 Winter Olympics, officially the XIX Olympic Winter Games and commonly known as Salt Lake 2002 ( arp, Niico'ooowu' 2002; Gosiute Shoshoni: ''Tit'-so-pi 2002''; nv, Sooléí 2002; Shoshoni: ''Soónkahni 2002''), was an internation ...

, and this served as a great boost to the economy. The ski resorts have increased in popularity, and many of the Olympic venues built along the

Wasatch Front

The Wasatch Front is a metropolitan region in the north-central part of the U.S. state of Utah. It consists of a chain of contiguous cities and towns stretched along the Wasatch Range from approximately Provo in the south to Logan in the nort ...

continue to be used for sporting events. Preparation for the Olympics spurred the development of the light-rail system in the

Salt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Sandy, South Jordan, West Jordan, and West Valley City; its total p ...

, known as

TRAX

Trax may refer to:

Music

* ''Trax'' (album), the debut album from Japanese electronic music group Ravex

*TRAX (band), a Korean rock band

*Trax Records, first house music label owned by Larry Sherman in Chicago

* Trax (sequencer), an old MIDI sequ ...

, and the re-construction of the freeway system around the city.

In 1957, Utah created the Utah State Parks Commission with four parks. Today,

Utah State Parks

Utah State Parks is the common name for the Division of Utah State Parks and Recreation; a division of the Utah Department of Natural Resources. This is the state agency that manages the state park system of the U.S. state of Utah.

Utah' ...

manages 43 parks and several undeveloped areas totaling over of land and more than of water. Utah's state parks are scattered throughout Utah, from

Bear Lake State Park at the Utah/Idaho border to

Edge of the Cedars State Park

Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum is a state park and museum of Utah, USA, located in Blanding. It is an Ancestral Puebloan archaeological site, a museum, and an archaeological repository. Cowboys from the nearby town of Bluff camped there ...

Museum deep in the

Four Corners

The Four Corners is a region of the Southwestern United States consisting of the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico. The Four Corners area ...

region and everywhere in between. Utah State Parks is also home to the state's

off highway vehicle

An off-road vehicle, sometimes referred to as an overland or adventure vehicle, is considered to be any type of vehicle which is capable of driving on and off paved or gravel surface. It is generally characterized by having large tires with de ...

office, state boating office and the trails program.

During the late 20th century, the state grew quickly. In the 1970s growth was phenomenal in the suburbs of the Wasatch Front.

Sandy

Sandy may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Sandy (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Sandy (surname), a list of people

* Sandy (singer), Brazilian singer and actress Sandy Leah Lima (born 1983)

* (Sandy) ...

was one of the fastest-growing cities in the country at that time. Today, many areas of Utah continue to see boom-time growth. Northern

Davis

Davis may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Mount Davis (Antarctica)

* Davis Island (Palmer Archipelago)

* Davis Valley, Queen Elizabeth Land

Canada

* Davis, Saskatchewan, an unincorporated community

* Davis Strait, between Nunavut and Green ...

, southern and western

Salt Lake

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per litre). ...

,

Summit

A summit is a point on a surface that is higher in elevation than all points immediately adjacent to it. The topographic terms acme, apex, peak (mountain peak), and zenith are synonymous.

The term (mountain top) is generally used only for a m ...

, eastern

Tooele

Tooele ( ) is a city in Tooele County in the U.S. state of Utah. The population was 35,742 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Tooele County. Located approximately 30 minutes southwest of Salt Lake City, Tooele is known for Tooele Ar ...

,

Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

,

Wasatch, and

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

counties are all growing very quickly. Management of transportation and urbanization are major issues in politics, as development consumes agricultural land and wilderness areas and transportation is a major reason for poor

air quality in Utah

Air quality in Utah is often some of the worst in the United States. Poor air quality in Utah is due to the mountainous topography which can cause pollutants to build up near the surface (especially during inversions) combined with the prevalenc ...

.

Geography and geology

Utah is known for its natural diversity and is home to features ranging from arid deserts with

sand dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

s to thriving

pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

forests in mountain valleys. It is a rugged and geographically diverse state at the convergence of three distinct geological regions: the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

, the

Great Basin, and the

Colorado Plateau

The Colorado Plateau, also known as the Colorado Plateau Province, is a physiographic and desert region of the Intermontane Plateaus, roughly centered on the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States. This province covers an area ...

.

Utah covers an area of . It is one of the

Four Corners

The Four Corners is a region of the Southwestern United States consisting of the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico. The Four Corners area ...

states and is bordered by Idaho in the north, Wyoming in the north and east, by Colorado in the east, at a single point by

New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

to the southeast, by Arizona in the south, and by Nevada in the west. Only three U.S. states (Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming) have exclusively latitude and longitude lines as boundaries.

One of Utah's defining characteristics is the variety of its

terrain

Terrain or relief (also topographical relief) involves the vertical and horizontal dimensions of land surface. The term bathymetry is used to describe underwater relief, while hypsometry studies terrain relative to sea level. The Latin w ...

. Running down the middle of the state's northern third is the

Wasatch Range

The Wasatch Range ( ) or Wasatch Mountains is a mountain range in the western United States that runs about from the Utah-Idaho border south to central Utah. It is the western edge of the greater Rocky Mountains, and the eastern edge of the ...

, which rises to heights of almost above sea level. Utah is home to world-renowned

ski resort

A ski resort is a resort developed for skiing, snowboarding, and other winter sports. In Europe, most ski resorts are towns or villages in or adjacent to a ski area – a mountainous area with pistes (ski trails) and a ski lift system. In N ...

s made popular by light, fluffy snow and winter storms that regularly dump up to three feet of it overnight. In the state's northeastern section, running east to west, are the

Uinta Mountains

The Uinta Mountains ( ) are an east-west trending chain of mountains in northeastern Utah extending slightly into southern Wyoming in the United States. As a subrange of the Rocky Mountains, they are unusual for being the highest range in the ...

, which rise to heights of over . The highest point in the state,

Kings Peak, at ,

lies within the Uinta Mountains.

At the western base of the Wasatch Range is the

Wasatch Front

The Wasatch Front is a metropolitan region in the north-central part of the U.S. state of Utah. It consists of a chain of contiguous cities and towns stretched along the Wasatch Range from approximately Provo in the south to Logan in the nort ...

, a series of valleys and basins that are home to the most populous parts of the state. It stretches approximately from

Brigham City

Brigham City is a city in Box Elder County, Utah, United States. The population was 17,899 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Box Elder County. It lies on the western slope of the Wellsville Mountains, a branch of the Wasatch Range a ...

at the north end to

Nephi at the south end. Approximately 75 percent of the state's population lives in this corridor, and population growth is rapid.

Western Utah is mostly arid desert with a

basin and range

Basin and range topography is characterized by alternating parallel mountain ranges and valleys. It is a result of crustal extension due to mantle upwelling, gravitational collapse, crustal thickening, or relaxation of confining stresses. The ex ...

topography. Small mountain ranges and rugged terrain punctuate the landscape. The

Bonneville Salt Flats

The Bonneville Salt Flats are a densely packed salt pan in Tooele County in northwestern Utah. A remnant of the Pleistocene Lake Bonneville, it is the largest of many salt flats west of the Great Salt Lake. It is public land managed by the ...

are an exception, being comparatively flat as a result of once forming the bed of ancient

Lake Bonneville

Lake Bonneville was the largest Late Pleistocene paleolake in the Great Basin of western North America. It was a pluvial lake that formed in response to an increase in precipitation and a decrease in evaporation as a result of cooler temperature ...

. Great Salt Lake,

Utah Lake

Utah Lake is a shallow freshwater lake in the center of Utah County, Utah, Utah County, Utah, United States. It lies in Utah Valley, surrounded by the Provo, Utah, Provo-Orem, Utah, Orem metropolitan area. The lake's only river outlet, the Jordan ...

,

Sevier Lake

Sevier Lake is an intermittent and endorheic lake which lies in the lowest part of the Sevier Desert, Millard County, Utah. Like Great Salt Lake and Utah Lake, it is a remnant of Pleistocene Lake Bonneville. Sevier Lake is fed primarily by the ...

, and

Rush Lake are all remnants of this ancient freshwater lake, which once covered most of the eastern Great Basin. West of the

Great Salt Lake, stretching to the Nevada border, lies the arid

Great Salt Lake Desert

The Great Salt Lake Desert (colloquially referred to as the West Desert) is a large dry lake in northern Utah, United States, between the Great Salt Lake and the Nevada border. It is a subregion of the larger Great Basin Desert, and noted for w ...

. One exception to this aridity is

Snake Valley, which is (relatively) lush due to large springs and wetlands fed from

groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath Earth's surface in rock and soil pore spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. About 30 percent of all readily available freshwater in the world is groundwater. A unit of rock or an unconsolidat ...

derived from snow melt in the

Snake Range

The Snake Range is a mountain range in White Pine County, Nevada, United States. The south-central portion of the range is included within Great Basin National Park, with most of the remainder included within the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest ...

,

Deep Creek Range

The Deep Creek Range, (often refereed to as the Deep Creek Mountains (Goshute: Pi'a-roi-ya-bi), are a mountain range in the Great Basin located in extreme western Tooele and Juab counties in Utah, United States.

The range trends north-south (wit ...

, and other tall mountains to the west of Snake Valley.

Great Basin National Park

Great Basin National Park is an American national park located in White Pine County in east-central Nevada, near the Utah border, established in 1986. The park is most commonly entered by way of Nevada State Route 488, which is connected to U ...

is just over the Nevada state line in the southern Snake Range. One of western Utah's most impressive, but least visited attractions is

Notch Peak

Notch Peak is a distinctive summit located on Sawtooth Mountain in the House Range, west of Delta, Utah, United States. The peak and the surrounding area are part of the Notch Peak Wilderness Study Area (WSA). Bristlecone pines, estimated to b ...

, the tallest limestone cliff in North America, located west of

Delta

Delta commonly refers to:

* Delta (letter) (Δ or δ), a letter of the Greek alphabet

* River delta, at a river mouth

* D (NATO phonetic alphabet: "Delta")

* Delta Air Lines, US

* Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19

Delta may also r ...

.

Much of the scenic southern and southeastern landscape (specifically the

Colorado Plateau

The Colorado Plateau, also known as the Colorado Plateau Province, is a physiographic and desert region of the Intermontane Plateaus, roughly centered on the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States. This province covers an area ...

region) is

sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

, specifically

Kayenta sandstone

The Kayenta Formation is a geological formation in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the Colorado Plateau province of the United States, including northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. Traditionally has been suggeste ...

and

Navajo sandstone

The Navajo Sandstone is a geological formation in the Glen Canyon Group that is spread across the U.S. states of southern Nevada, northern Arizona, northwest Colorado, and Utah as part of the Colorado Plateau province of the United States.Anonym ...

. The

Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid watershed that encompasses parts of seven U.S. s ...

and its tributaries wind their way through the sandstone, creating some of the world's most striking and wild terrain (the area around the confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers was the last to be mapped in the lower 48 United States). Wind and rain have also sculpted the soft sandstone over millions of years. Canyons, gullies, arches, pinnacles, buttes, bluffs, and mesas are the common sights throughout south-central and southeast Utah.

This terrain is the central feature of protected state and federal parks such as

Arches

An arch is a vertical curved structure that spans an elevated space and may or may not support the weight above it, or in case of a horizontal arch like an arch dam, the hydrostatic pressure against it.

Arches may be synonymous with vaul ...

,

Bryce Canyon

Bryce Canyon National Park () is an American national park located in southwestern Utah. The major feature of the park is Bryce Canyon, which despite its name, is not a canyon, but a collection of giant natural amphitheaters along the eastern ...

,

Canyonlands

Canyonlands National Park is an American national park located in southeastern Utah near the town of Moab. The park preserves a colorful landscape eroded into numerous canyons, mesas, and buttes by the Colorado River, the Green River, and their ...

,

Capitol Reef

Capitol Reef National Park is an American national park in south-central Utah. The park is approximately long on its northsouth axis and just wide on average. The park was established in 1971 to preserve of desert landscape and is open all ye ...

, and

Zion

Zion ( he, צִיּוֹן ''Ṣīyyōn'', LXX , also variously transliterated ''Sion'', ''Tzion'', ''Tsion'', ''Tsiyyon'') is a placename in the Hebrew Bible used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Israel as a whole (see Na ...

national parks,

Cedar Breaks

Cedar Breaks National Monument is a U.S. National Monument located in the U.S. state of Utah near Cedar City. Cedar Breaks is a natural amphitheater, stretching across , with a depth of over . The elevation of the rim of the amphitheater is over ...

,

Grand Staircase–Escalante,

Hovenweep

Hovenweep National Monument is located on land in southwestern Colorado and southeastern Utah, between Cortez, Colorado and Blanding, Utah on the Cajon Mesa of the Great Sage Plain. Shallow tributaries run through the wide and deep canyons into t ...

, and

Natural Bridges

A natural arch, natural bridge, or (less commonly) rock arch is a natural landform where an arch has formed with an opening underneath. Natural arches commonly form where inland cliffs, coastal cliffs, fins or stacks are subject to erosion f ...

national monuments,

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (shortened to Glen Canyon NRA or GCNRA) is a national recreation area and conservation unit of the United States National Park Service that encompasses the area around Lake Powell and lower Cataract Canyon ...

(site of the popular tourist destination,

Lake Powell

Lake Powell is an artificial reservoir on the Colorado River in Utah and Arizona, United States. It is a major vacation destination visited by approximately two million people every year. It is the second largest artificial reservoir by maximum ...

),

Dead Horse Point and

Goblin Valley

Goblin Valley State Park is a state park of Utah, in the United States. The park features thousands of hoodoos, referred to locally as goblins, which are formations of mushroom-shaped rock pinnacles, some as tall as several yards (meters). The ...

state parks, and

Monument Valley

Monument Valley ( nv, Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii, , meaning ''valley of the rocks'') is a region of the Colorado Plateau characterized by a cluster of sandstone buttes, the largest reaching above the valley floor. It is located on the Utah-Arizona ...

. The

Navajo Nation

The Navajo Nation ( nv, Naabeehó Bináhásdzo), also known as Navajoland, is a Native Americans in the United States, Native American Indian reservation, reservation in the United States. It occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwe ...

also extends into southeastern Utah. Southeastern Utah is also punctuated by the remote, but lofty

La Sal,

Abajo, and

Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

* Henry (given name)

*Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

mountain ranges.

Eastern (northern quarter) Utah is a high-elevation area covered mostly by plateaus and basins, particularly the Tavaputs Plateau and

San Rafael Swell

The San Rafael Swell is a large geologic feature located in south-central Utah, United States about west of Green River. The San Rafael Swell, measuring approximately , consists of a giant dome-shaped anticline of sandstone, shale, and limest ...

, which remain mostly inaccessible, and the

Uinta Basin

The Uinta Basin (also known as the Uintah Basin) is a physiographic section of the larger Colorado Plateaus province, which in turn is part of the larger Intermontane Plateaus physiographic division. It is also a geologic structural basin in ...

, where the majority of eastern Utah's population lives. Economies are dominated by mining,

oil shale

Oil shale is an organic-rich fine-grained sedimentary rock containing kerogen (a solid mixture of organic chemical compounds) from which liquid hydrocarbons can be produced. In addition to kerogen, general composition of oil shales constitu ...

,

oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

, and natural gas-drilling,

ranching

A ranch (from es, rancho/Mexican Spanish) is an area of landscape, land, including various structures, given primarily to ranching, the practice of raising grazing livestock such as cattle and sheep. It is a subtype of a farm. These terms are ...

, and

recreation

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for enjoyment, amusement, or ple ...

. Much of eastern Utah is part of the

Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation

The Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation (, ) is located in northeastern Utah, United States. It is the homeland of the Ute Indian Tribe ( Ute dialect: Núuchi-u), and is the largest of three Indian reservations inhabited by members of the Ute Tri ...

. The most popular destination within northeastern Utah is

Dinosaur National Monument

Dinosaur National Monument is an American national monument located on the southeast flank of the Uinta Mountains on the border between Colorado and Utah at the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers. Although most of the monument area is ...

near

Vernal

Vernal, the county seat and largest city in Uintah County, Utah, Uintah County is in northeastern Utah, approximately east of Salt Lake City and west of the Colorado border. As of the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, the city populatio ...

.

Southwestern Utah is the lowest and hottest spot in Utah. It is known as Utah's

Dixie

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas shift over the years), or the extent of the area it cove ...

because early settlers were able to grow some cotton there.

Beaverdam Wash in far southwestern Utah is the lowest point in the state, at .

The northernmost portion of the

Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert ( ; mov, Hayikwiir Mat'aar; es, Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Southwestern United States. It is named for the indigenous Mojave people. It is located primarily i ...

is also located in this area. Dixie is quickly becoming a popular recreational and retirement destination, and the population is growing rapidly. Although the Wasatch Mountains end at

Mount Nebo

Mount Nebo ( ar, جَبَل نِيبُو, Jabal Nībū; he, , Har Nəḇō) is an elevated ridge located in Jordan, approximately above sea level. Part of the Abarim mountain range, Mount Nebo is mentioned in the Bible as the place where Mose ...

near

Nephi, a complex series of mountain ranges extends south from the southern end of the range down the spine of Utah. Just north of Dixie and east of

Cedar City

Cedar City is the largest city in Iron County, Utah, United States. It is located south of Salt Lake City, and north of Las Vegas on Interstate 15. It is the home of Southern Utah University, the Utah Shakespeare Festival, the Utah Summer Gam ...

is the state's highest ski resort,

Brian Head.

Like most of the

western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

* Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

and

southwestern states, the

federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

owns much of the land in Utah. Over 70 percent of the land is either

BLM land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various isl ...

, Utah State Trustland, or

U.S. National Forest

In the United States, national forest is a classification of protected and managed federal lands. National forests are largely forest and woodland areas owned collectively by the American people through the federal government, and managed by t ...

,

U.S. National Park,

U.S. National Monument

In the United States, a national monument is a protected area that can be created from any land owned or controlled by the federal government by proclamation of the President of the United States or an act of Congress. National monuments prot ...

,

National Recreation Area

A national recreation area (NRA) is a protected area in the United States established by an Act of Congress to preserve enhanced recreational opportunities in places with significant natural and scenic resources. There are 40 NRAs, which emphasiz ...

or

U.S. Wilderness Area

The National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS) of the United States protects federally managed wilderness areas designated for preservation in their natural condition. Activity on formally designated wilderness areas is coordinated by the Na ...

. Utah is the only state where every county contains some national forest.

File:Arches 1 - panoramio.jpg, Arches National Park

Arches National Park is a national park in eastern Utah, United States. The park is adjacent to the Colorado River, north of Moab, Utah. More than 2,000 natural sandstone arches are located in the park, including the well-known Delicate Arch, a ...

File:My Public Lands Roadtrip- Pariette Wetlands in Utah (20220345702).jpg, Pariette Wetlands

File:LCLfallfoliage2005.JPG, Little Cottonwood Canyon

Little Cottonwood Canyon lies within the Wasatch-Cache National Forest along the eastern side of the Salt Lake Valley, roughly 15 miles from Salt Lake City, Utah. The canyon is part of Granite, a CDP and "Community Council" designated by Salt L ...

File:Deer Creek Reservoir.jpg, Deer Creek Reservoir

The Deer Creek Dam and Reservoir hydroelectric facilities are on the Provo River in western Wasatch County, Utah, United States, about northeast of Provo. The dam is a zoned earthfill structure high with a crest length of . The dam contains ...

File:American Fork Canyon from Timpanogos Cave entrance.jpg, American Fork Canyon

American Fork Canyon is a canyon in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah, United States. The canyon is famous for the Timpanogos Cave National Monument, which resides on its south side. It is named after the American Fork River, which runs through the ...

File:Kolob Canyon at Zion National Park, March 2019.jpg, Kolob Canyons

Zion National Park is an American national park located in southwestern Utah near the town of Springdale. Located at the junction of the Colorado Plateau, Great Basin, and Mojave Desert regions, the park has a unique geography and a variety ...

at Zion National Park

Zion National Park is an American national park located in southwestern Utah near the town of Springdale. Located at the junction of the Colorado Plateau, Great Basin, and Mojave Desert regions, the park has a unique geography and a variety o ...

Adjacent states

*

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and W ...

(north)

*

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the sou ...

(east and north)

*

Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the wes ...

(east)

*

Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

(west)

*

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States. It is the list of U.S. states and territories by area, 6th largest and the list of U.S. states and territories by population, 14 ...

(south)

Climate

Utah features a dry,

semi-arid

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of semi- ...

to

desert climate

The desert climate or arid climate (in the Köppen climate classification ''BWh'' and ''BWk''), is a dry climate sub-type in which there is a severe excess of evaporation over precipitation. The typically bald, rocky, or sandy surfaces in desert ...

, although its many mountains feature a large variety of climates, with the highest points in the

Uinta Mountains

The Uinta Mountains ( ) are an east-west trending chain of mountains in northeastern Utah extending slightly into southern Wyoming in the United States. As a subrange of the Rocky Mountains, they are unusual for being the highest range in the ...

being above the

timberline. The dry weather is a result of the state's location in the

rain shadow

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from water bodies (such as oceans and large lakes) is carri ...

of the

Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primari ...

in California. The eastern half of the state lies in the rain shadow of the

Wasatch Mountains

The Wasatch Range ( ) or Wasatch Mountains is a mountain range in the western United States that runs about from the Utah-Idaho border south to central Utah. It is the western edge of the greater Rocky Mountains, and the eastern edge of the ...

. The primary source of precipitation for the state is the Pacific Ocean, with the state usually lying in the path of large Pacific storms from October to May. In summer, the state, especially southern and eastern Utah, lies in the path of

monsoon