United States Steel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

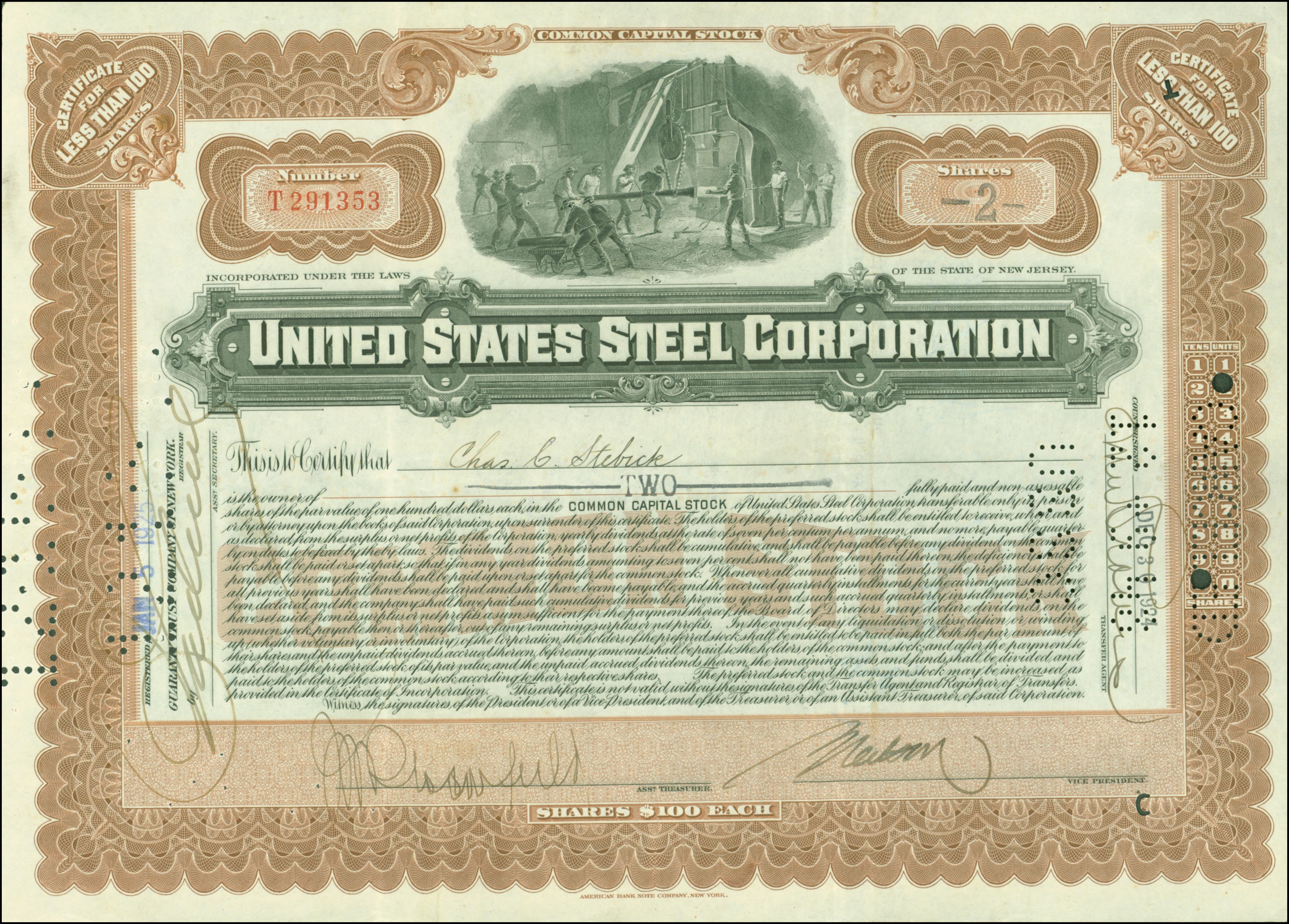

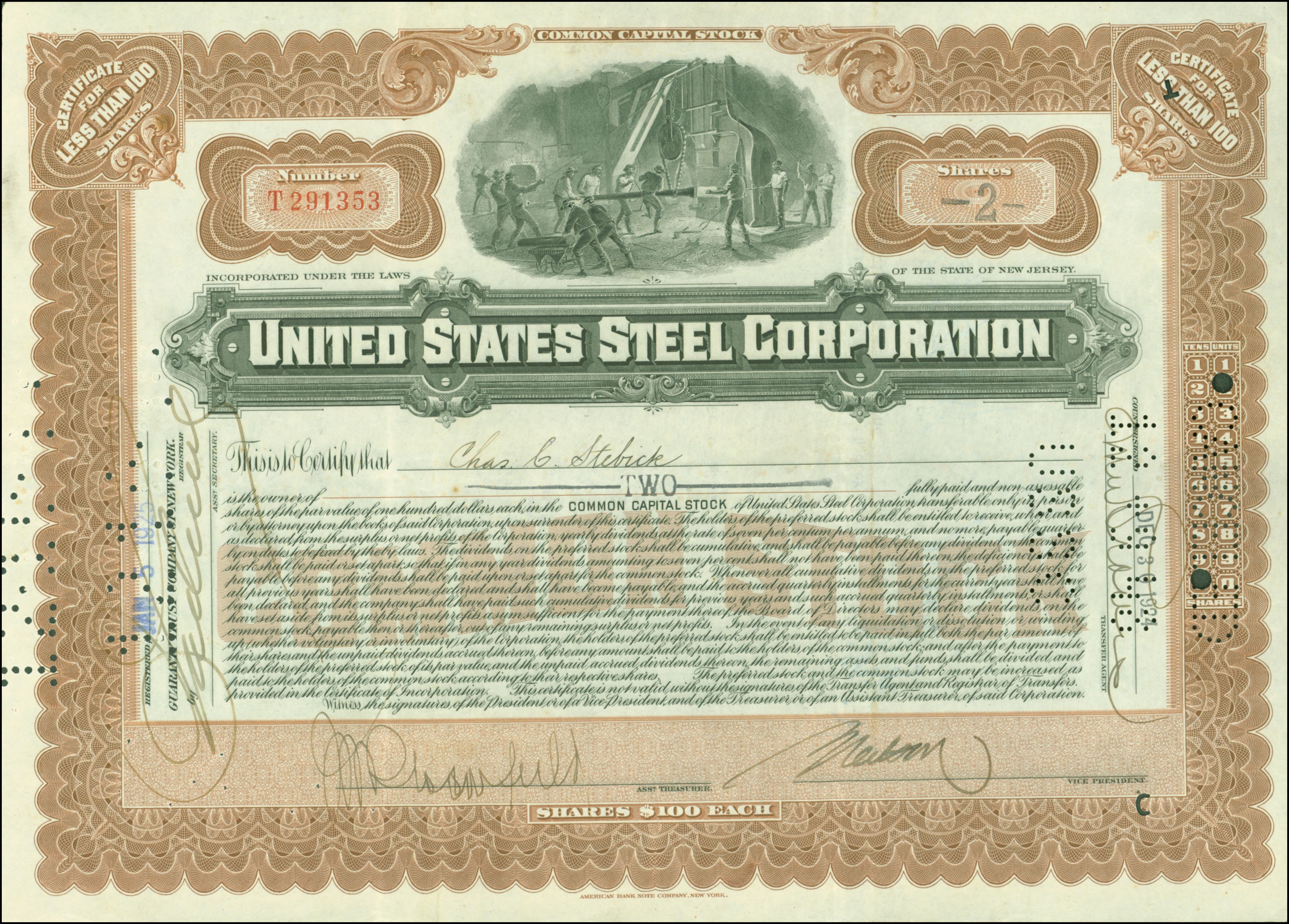

United States Steel Corporation, more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an American integrated steel producer headquartered in

J. P. Morgan formed U.S. Steel on March 2, 1901 (incorporated on February 25), by financing the merger of

J. P. Morgan formed U.S. Steel on March 2, 1901 (incorporated on February 25), by financing the merger of

At the end of the twentieth century, the corporation was deriving much of its revenue and net income from its energy operations. Led by CEO Thomas Usher, U.S. Steel spun off Marathon and other non-steel assets (except railroad company Transtar) in October 2001. It expanded internationally for the first time by purchasing operations in

At the end of the twentieth century, the corporation was deriving much of its revenue and net income from its energy operations. Led by CEO Thomas Usher, U.S. Steel spun off Marathon and other non-steel assets (except railroad company Transtar) in October 2001. It expanded internationally for the first time by purchasing operations in

When the Steelmark logo was created, U.S. Steel attached the following meaning to it: "Steel lightens your work, brightens your leisure and widens your world." The logo was used as part of a major marketing campaign to educate consumers about how important steel is in people's daily lives. The Steelmark logo was used in print, radio and television ads as well as on labels for all steel products, from steel tanks to tricycles to filing cabinets.

In the 1960s, U.S. Steel turned over the Steelmark program to the AISI, where it came to represent the steel industry as a whole. During the 1970s, the logo's meaning was extended to include the three materials used to produce steel: yellow for coal, orange for ore and blue for steel scrap. In the late 1980s, when the AISI founded the Steel Recycling Institute (SRI), the logo took on a new life reminiscent of its 1950s meaning.

The

When the Steelmark logo was created, U.S. Steel attached the following meaning to it: "Steel lightens your work, brightens your leisure and widens your world." The logo was used as part of a major marketing campaign to educate consumers about how important steel is in people's daily lives. The Steelmark logo was used in print, radio and television ads as well as on labels for all steel products, from steel tanks to tricycles to filing cabinets.

In the 1960s, U.S. Steel turned over the Steelmark program to the AISI, where it came to represent the steel industry as a whole. During the 1970s, the logo's meaning was extended to include the three materials used to produce steel: yellow for coal, orange for ore and blue for steel scrap. In the late 1980s, when the AISI founded the Steel Recycling Institute (SRI), the logo took on a new life reminiscent of its 1950s meaning.

The

U.S. Steel has multiple domestic and international facilities.

Of note in the United States is Clairton Works, Edgar Thomson Works, and Irvin Plant, which are all members of Mon Valley Works just outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Clairton Works is the largest coking facility in North America. Edgar Thomson Works is one of the oldest steel mills in the world. The company acquired Great Lakes Works and Granite City Works, both large integrated steel mills, in 2003 and is partnered with Severstal North America in operating the world's largest electro-galvanizing line, Double Eagle Steel Coating Company at the historic Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan.

U.S. Steel's largest domestic facility is

U.S. Steel has multiple domestic and international facilities.

Of note in the United States is Clairton Works, Edgar Thomson Works, and Irvin Plant, which are all members of Mon Valley Works just outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Clairton Works is the largest coking facility in North America. Edgar Thomson Works is one of the oldest steel mills in the world. The company acquired Great Lakes Works and Granite City Works, both large integrated steel mills, in 2003 and is partnered with Severstal North America in operating the world's largest electro-galvanizing line, Double Eagle Steel Coating Company at the historic Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan.

U.S. Steel's largest domestic facility is

U.S. Steel Gary Works Photograph Collection, 1906–1971U.S. Steel Movie clip of the Contemporary Resort Construction, on BigFloridaCountry.com

* ttp://www.steelonthenet.com/kb/history-us-steel.html History of the United States Steel Corporation, 1873–2011br>Guide to United States Steel Corporation. Training manuals. 5342. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University.Fortune Magazine 1959 "Fortune 500" list

United States Steel Corporation photographs

at Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School. {{Authority control Manufacturing companies established in 1901 Metals monopolies Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange Former components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average Historic American Engineering Record in Pennsylvania 1901 establishments in Pennsylvania 1901 mergers and acquisitions

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsyl ...

, with production operations primarily in the United States of America and in several countries across Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the ...

. It was the 8th largest steel producer in the world in 2008. By 2018, the company was the world's 38th-largest steel producer and the second-largest in the United States behind Nucor Corporation.

Though renamed USX Corporation in 1986, the company was renamed United States Steel in 2001 after spinning off its energy business, including Marathon Oil

Marathon Oil Corporation is an American company engaged in hydrocarbon exploration incorporated in Ohio and headquartered in the Marathon Oil Tower in Houston, Texas. A direct descendant of Standard Oil, it also runs international gas operati ...

, and other assets from its core steel concern.

History

Formation

J. P. Morgan formed U.S. Steel on March 2, 1901 (incorporated on February 25), by financing the merger of

J. P. Morgan formed U.S. Steel on March 2, 1901 (incorporated on February 25), by financing the merger of Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in ...

's Carnegie Steel Company

Carnegie Steel Company was a steel-producing company primarily created by Andrew Carnegie and several close associates to manage businesses at steel mills in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area in the late 19th century. The company was formed ...

with Elbert H. Gary's Federal Steel Company and William Henry "Judge" Moore

William Henry ("Judge") Moore (October 28, 1848 – January 11, 1923) was an American attorney and financier. He organized and promoted or sat as a director for several steel companies that were merged with among others the Carnegie Steel Compa ...

's National Steel Company for $492 million ($ billion today). At one time, U.S. Steel was the largest steel producer and largest corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

in the world. It was capitalized at $1.4 billion ($ billion today), making it the world's first billion-dollar corporation. The company established its headquarters in the Empire Building

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

at 71 Broadway in New York City; it remained a major tenant in the building for 75 years. Charles M. Schwab, the Carnegie Steel executive who originally suggested the merger to Morgan, ultimately emerged as the new corporation's first President.

In 1907 U.S. Steel bought its largest competitor, the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (1852–1952), also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based entirely within ...

, which was headquartered in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

. Tennessee Coal was replaced in the Dow Jones Industrial Average

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), Dow Jones, or simply the Dow (), is a stock market index of 30 prominent companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States.

The DJIA is one of the oldest and most commonly followed equity indexe ...

by the General Electric Company

The General Electric Company (GEC) was a major British industrial conglomerate involved in consumer and defence electronics, communications, and engineering. The company was founded in 1886, was Britain's largest private employer with over 250 ...

. The federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

attempted to use federal antitrust laws to break up U.S. Steel in 1911 (the same year Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co- ...

was broken up), but that effort ultimately failed. In 1902, its first full year of operation, U.S. Steel made 67 percent of all the steel produced in the United States. About 100 years later, as of 2001 it produced only 8 percent more than it did in 1902 and its shipments accounted for only about 8 percent of domestic consumption.

According to the author Douglas Blackmon in '' Slavery by Another Name'', the growth of U.S. Steel and its subsidiaries in the South was partly dependent on the labor of cheaply paid black workers and exploited convicts. The company could obtain black labor at a fraction of the cost of white labor by taking advantage of the Black Codes and discriminatory laws passed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Southern states after the Reconstruction Era. In addition, U.S. Steel had agreements with more than 20 counties in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

to obtain the labor of its prisoners, often paying locals nine dollars a month for workers who would be forced into their mines through a system of convict leasing

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; ...

. This practice continued until at least the late 1920s. While some individuals were guilty of a crime they did not receive payment or recognition for their work; many died from abuse, malnutrition, and dire working and living conditions. This practice of convict leasing was fairly ubiquitous as eight Southern states had similar practices and many companies, as well as farmers, took advantage of this.

The Corporation, as it was known on Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for ...

, was distinguished by its size, rather than for its efficiency or creativity during its heyday. In 1901, it controlled two-thirds of steel production and, through its Pittsburgh Steamship Company, developed the largest commercial fleet on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five la ...

. Because of heavy debts taken on at the company's formation—Carnegie insisted on being paid in gold bonds for his stake—and fears of antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

litigation, U.S. Steel moved cautiously. Competitors often innovated faster, especially Bethlehem Steel

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was an American steelmaking company headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. For most of the 20th century, it was one of the world's largest steel producing and shipbuilding companies. At the height of its succ ...

, run by Charles Schwab, U.S. Steel's former president. U.S. Steel's share of the expanding market slipped to 50 percent by 1911. James A. Farrell was named president in 1911 and served until 1932.

Mid-century

U.S. Steel ranked 16th among United States corporations in the value ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

production contracts. Production peaked at more than 35 million tons in 1953. Its employment was greatest in 1943, when it had more than 340,000 employees.

The federal government intervened to try to control U.S. Steel. President Harry S. Truman attempted to take over its steel mills in 1952 to resolve a crisis with its union, the United Steelworkers of America

The United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied Industrial and Service Workers International Union, commonly known as the United Steelworkers (USW), is a general trade union with members across North America. Headquar ...

. The Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

blocked the takeover by ruling that the president did not have the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

al authority to seize the mills. President John F. Kennedy was more successful in 1962 when he pressured the steel industry into reversing price increases that Kennedy considered dangerously inflationary.

U.S. Steel strongly resisted Kennedy administration efforts to enlist Alabama businesses to support the desegregation of the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, or Bama) is a public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of Alabama is the oldest and largest of the publi ...

, which race-baiting Gov. George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist an ...

had promised to block by standing in the schoolhouse door. Although the firm employed more than 30,000 workers in Birmingham, Ala., company president Roger M. Blough in 1963 "went out of his way to announce that any attempt to use his company position in Birmingham to pressure local whites was 'repugnant to me personally' and 'repugnant to my fellow officers at U.S. Steel.'"

In the postwar years, the steel industry and heavy manufacturing went through a restructuring that caused a decline in U.S. Steel's need for labor, production, and portfolio. Many jobs moved offshore. By 2000, the company employed 52,500 people.

The USX period

In the early days of theReagan Administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over ...

, steel firms won substantial tax breaks in order to compete with imported goods. But instead of modernizing their mills, steel companies shifted capital out of steel and into more profitable areas. In March 1982, U.S. Steel took its concessions and paid $1.4 billion in cash and $4.7 billion in loans for Marathon Oil

Marathon Oil Corporation is an American company engaged in hydrocarbon exploration incorporated in Ohio and headquartered in the Marathon Oil Tower in Houston, Texas. A direct descendant of Standard Oil, it also runs international gas operati ...

, saving approximately $500 million in taxes through the merger. The architect of tax concessions to steel firms, Senator Arlen Specter

Arlen Specter (February 12, 1930 – October 14, 2012) was an American lawyer, author and politician who served as a United States Senator from Pennsylvania from 1981 to 2011. Specter was a Democrat from 1951 to 1965, then a Republican fr ...

(R-PA), complained that "we go out on a limb in Congress and we feel they should be putting it in steel." The events are the subject of "The U.S. Steal Song" by folk singer Anne Feeney.

In 1984 the federal government prevented U.S. Steel from acquiring National Steel, and political pressure from the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

, as well as the United Steelworkers

The United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied Industrial and Service Workers International Union, commonly known as the United Steelworkers (USW), is a general trade union with members across North America. Headquar ...

(USW), forced the company to abandon plans to import British Steel Corporation

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

slabs. U.S. Steel finally acquired National Steel's assets in 2003 after National Steel went bankrupt. As part of its diversification plan, U.S. Steel had acquired Marathon Oil on January 7, 1982, as well as Texas Oil and Gas several years later. Recognizing its new scope, it reorganized its holdings as USX Corporation in 1986, with U.S. Steel (renamed USS, Inc.) as a major subsidiary.

About 22,000 USX employees stopped work on August 1, 1986, after the United Steelworkers of America

The United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied Industrial and Service Workers International Union, commonly known as the United Steelworkers (USW), is a general trade union with members across North America. Headquar ...

and the company could not agree on new employee contract terms. This was characterized by the company as a strike and by the union as a lockout

Lockout may refer to:

* Lockout (industry), a type of work stoppage

** Dublin Lockout, a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers 1913 - 1914

* Lockout (sports), lockout in sports leagues

**MLB lockout, loc ...

. This resulted in most USX facilities becoming idle until February 1, 1987, seriously degrading the steel division's market share. A compromise was brokered and accepted by the union membership on January 31, 1987. On February 4, 1987, three days after the agreement had been reached to end the work stoppage, USX announced that four USX plants would remain closed permanently, eliminating about 3,500 union jobs. The closure of so many plants created the term "rust belt

The Rust Belt is a region of the United States that experienced industrial decline starting in the 1950s. The U.S. manufacturing sector as a percentage of the U.S. GDP peaked in 1953 and has been in decline since, impacting certain regions a ...

" for a region of idle and derelict factories.

Corporate raid

In business, a corporate raid is the process of buying a large stake in a corporation and then using shareholder voting rights to require the company to undertake novel measures designed to increase the share value, generally in opposition to the ...

er Carl Icahn

Carl Celian Icahn (; born February 16, 1936) is an American financier. He is the founder and controlling shareholder of Icahn Enterprises, a public company and diversified conglomerate holding company based in Sunny Isles Beach. Icahn takes l ...

launched a hostile takeover

In business, a takeover is the purchase of one company (the ''target'') by another (the ''acquirer'' or ''bidder''). In the UK, the term refers to the acquisition of a public company whose shares are listed on a stock exchange, in contrast to ...

of the steel giant in late 1986 in the midst of the work stoppage. He conducted separate negotiations with the union and with management and proceeded to have proxy battles with shareholders and management. But he abandoned all efforts to buy out the company on January 8, 1987, a few weeks before union employees returned to work.

Recent history

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hung ...

.

In the early 2010s, U.S. Steel began investing to upgrade software programs throughout their manufacturing facilities.

In January 2012, U.S. Steel sold its Serbian mills outside Belgrade to the Serbian government

The Government of Serbia ( sr, Влада Србије, Vlada Srbije), formally the Government of the Republic of Serbia ( sr, Влада Републике Србије, Vlada Republike Srbije), commonly abbreviated to Serbian Government ( sr, � ...

, as their operations had been running at an economic loss.

On May 2, 2014, U.S. Steel announced an undisclosed number of layoffs affecting employees worldwide. On July 2, 2014, U.S. Steel was removed from S&P 500

The Standard and Poor's 500, or simply the S&P 500, is a stock market index tracking the stock performance of 500 large companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States. It is one of the most commonly followed equity indices. As of ...

index and placed in the S&P MidCap 400 Index, in light of its declining market capitalization.

Railroad ownership

U.S. Steel once owned the Northampton and Bath Railroad. The N&B was an short-line railroad built in 1904 that served Atlas Cement inNorthampton, Pennsylvania

Northampton is a borough in Northampton County, Pennsylvania. Its population was 10,395 as of the 2020 census. Northampton is located north of Allentown, northwest of Philadelphia, and west of New York City.

The borough is part of the Lehigh ...

, and Keystone Cement in Bath, Pennsylvania

Bath is a borough in Northampton County, Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, Bath had a population of 2,808. It is part of the Lehigh Valley metropolitan area, which had a population of 861,899 and was the 68th most populous metropolitan area i ...

. By 1979 cement shipments had dropped off such that the railroad was no longer economically viable, and U.S. Steel abandoned the line. A section of track was retained to serve Atlas Cement. The remainder of the right-of-way was transformed into the Nor-Bath Trail. U.S. Steel also owned the Atlantic City Mine Railroad, whose line in Wyoming operated from 1962 until 1983 and served an iron ore mine north of Atlantic City, Wyoming.

Through its Transtar subsidiary, U.S. Steel also owned other railroads that served its mines and mills. Those properties included the Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range Railway in the iron-mining region of northeast Minnesota; the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern that served its Gary Works in northwest Indiana; the Birmingham Southern Railroad serving the U.S. Steel mill in Birmingham, Alabama; and the Bessemer & Lake Erie

The Bessemer and Lake Erie Railroad is a class II railroad that operates in northwestern Pennsylvania and northeastern Ohio.

The railroad's main route runs from the Lake Erie port of Conneaut, Ohio, to the Pittsburgh suburb of Penn Hills, Penns ...

and Union railroads in western Pennsylvania that delivered iron ore and provided plant-switching services at its mill complex in Braddock, Pennsylvania and coke works in Clairton, Pennsylvania.

U.S. Steel also owned a large Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five la ...

commercial freighter fleet, under the Pittsburgh Steamship Company, that transported its raw materials from the Duluth area to Ashtabula, Ohio; Gary, Indiana; and Conneaut, Ohio. The laker fleet, the B&LE, and the DM&IR were acquired by Canadian National

The Canadian National Railway Company (french: Compagnie des chemins de fer nationaux du Canada) is a Canadian Class I freight railway headquartered in Montreal, Quebec, which serves Canada and the Midwestern and Southern United States.

CN ...

after U.S. Steel sold most of Transtar to that company. The ships are leased out to a different, domestic operator because of the United States cabotage law.

Inclusion in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (1901–1991)

U.S. Steel is a formerDow Jones Industrial Average

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), Dow Jones, or simply the Dow (), is a stock market index of 30 prominent companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States.

The DJIA is one of the oldest and most commonly followed equity indexe ...

component, listed from April 1, 1901, to May 3, 1991. It was removed under its USX Corporation name with Navistar International

Navistar, Inc is an American holding company created in 1986 as the successor to International Harvester. Navistar operates as the owner of International-branded trucks and diesel engines. The company also produces buses under the IC Bus ...

and Primerica. An original member of the S&P 500

The Standard and Poor's 500, or simply the S&P 500, is a stock market index tracking the stock performance of 500 large companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States. It is one of the most commonly followed equity indices. As of ...

since 1957, U.S. Steel was removed from that index on July 2, 2014, due to declining market capitalization.

Dividend history

The Board of Directors considers the declaration ofdividend

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders. When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a portion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-inv ...

s four times each year, with checks for dividends declared on common stock

Common stock is a form of corporate equity ownership, a type of security. The terms voting share and ordinary share are also used frequently outside of the United States. They are known as equity shares or ordinary shares in the UK and other Com ...

mailed for receipt on 10 March, June, September, and December. In 2008, the dividend was $0.30 per share, the highest in company history, but on April 27, 2009, it was reduced to $0.05 per share. Dividends may be paid by mailed check, direct electronic deposit into a bank account, or be reinvested in additional shares of U.S. Steel common stock.

Legal issues

Labor

U.S. Steel maintained the labor policies ofAndrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in ...

, which called for low wages and opposition to unionization. The Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers

Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (AA) was an American labor union formed in 1876 to represent iron and steel workers. It partnered with the Steel Workers Organizing Committee of the CIO, in November 1935. Both organizations dis ...

union that represented workers at the Homestead, Pennsylvania

Homestead is a borough in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA, in the Monongahela River valley southeast of downtown Pittsburgh and directly across the river from the city limit line. The borough is known for the Homestead Strike of 1892, an i ...

, plant was, for many years, broken after a violent strike in 1892. U.S. Steel defeated another strike in 1901, the year it was founded. U.S. Steel built the city of Gary, Indiana, in 1906, and 100 years later it remained the location of the largest integrated steel mill in the Northern Hemisphere. U.S. Steel reached a détente with unions during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, when under pressure from the Wilson Administration it relaxed its opposition to unions enough to allow some to operate in certain factories. It returned to its previous policies as soon as the war ended, however, and in a 1919 strike defeated union-organizing efforts by William Z. Foster of the AFL.

Heavy pressure from public opinion forced the company to give up its 12-hour day and adopt the standard eight-hour day. During the 1920s, U.S. Steel, like many other large employers, coupled paternalistic employment practices with "employee representation plans" (ERPs), which were company unions sponsored by management. These ERPs eventually became an important factor leading to the organization of the United Steelworkers of America

The United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied Industrial and Service Workers International Union, commonly known as the United Steelworkers (USW), is a general trade union with members across North America. Headquar ...

. The company dropped its hard-line, anti-union stance in 1937, when Myron Taylor, then president of U.S. Steel, agreed to recognize the Steel Workers Organizing Committee The Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) was one of two precursor labor organizations to the United Steelworkers. It was formed by the CIO (Committee for Industrial Organization) on June 7, 1936. It disbanded in 1942 to become the United Steel ...

, an arm of the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

(CIO) led by John L. Lewis. Taylor was an outsider, brought in during the Great Depression to rescue U.S. Steel, and had no emotional investment in the company's long history of opposition to unions. Watching the upheaval caused by the United Auto Workers

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, better known as the United Auto Workers (UAW), is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico ...

' successful sit-down strike in Flint, Michigan, and convinced that Lewis was someone he could deal with on a businesslike basis, Taylor sought stability through collective bargaining.

Still, U.S. Steel worked hand-in-hand with the Birmingham (Alabama) Police Department as it vigorously investigated and targeted labor activities during the 1930s and 1940s. The corporation developed and fed information to a "Red Squad" of detectives "who used the city's vagrancy and criminal-anarchy statutes (liberally reinforced by backroom beatings) to strike at radical labor organizers." In the 1950s, those investigations shifted from labor to civil rights activists.

The Steelworkers continue to have a contentious relationship with U.S. Steel, but far less so than the relationship that other unions had with employers in other industries in the United States. They launched a number of long strikes against U.S. Steel in 1946 and a 116-day strike in 1959, but those strikes were over wages and benefits and not the more fundamental issue of union recognition that led to violent strikes elsewhere.

The Steelworkers union attempted to mollify the problems of competitive foreign imports by entering into a so-called Experimental Negotiation Agreement (ENA) in 1974. This was to provide for arbitration

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or ' arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ...

if the parties were not able to reach an agreement on any new collective bargaining agreement

A collective agreement, collective labour agreement (CLA) or collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is a written contract negotiated through collective bargaining for employees by one or more trade unions with the management of a company (or with an ...

s, thereby preventing disruptive strikes. The ENA failed to stop the decline of the steel industry in the U.S.

U.S. Steel and the other employers terminated the ENA in 1984. In 1986, U.S. Steel employees stopped work after a dispute over contract terms, characterized by the company as a strike and by the union as a lockout

Lockout may refer to:

* Lockout (industry), a type of work stoppage

** Dublin Lockout, a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers 1913 - 1914

* Lockout (sports), lockout in sports leagues

**MLB lockout, loc ...

. In a letter to striking employees in 1986, Johnston warned, "There are not enough seats in the steel lifeboat for everybody." In addition to reducing the role of unions, the steel industry had sought to induce the federal government to take action to counteract the dumping of steel by foreign producers at below-market prices. Neither the concessions nor anti-dumping laws have restored the industry to the health and prestige it once had.

Environmental record

During the 1948 Donora smog, anair inversion

In meteorology, an inversion is a deviation from the normal change of an atmosphere, atmospheric property with altitude. It almost always refers to an inversion of the air temperature lapse rate, in which case it is called a temperature in ...

trapped industrial effluent (air pollution) from the American Steel and Wire plant and U.S. Steel's Donora Zinc Works in Donora, Pennsylvania.

In three days, 20 people died... After the inversion lifted, another 50 died, including Lukasz Musial, the father of baseball greatToday the Donora Smog Museum in that city tells of the influence that the hazardous Donora Smog had on the air quality standards enacted by the federal government in subsequent years. Researchers at theStan Musial Stanley Frank Musial (; born Stanislaw Franciszek Musial; November 21, 1920 – January 19, 2013), nicknamed "Stan the Man", was an American baseball outfielder and first baseman. Widely considered to be one of the greatest and most consis .... Hundreds more lived the rest of their lives with damaged lungs and hearts. But another 40 years would pass before the whole truth about Donora's bad air made public-health history.

Political Economy Research Institute

The Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) is an independent research unit at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. According to its mission statement, it "...promotes human and ecological well-being through our original research". PERI wa ...

have ranked U.S. Steel as the eighth-greatest corporate producer of air pollution in the United States

Air pollution is the introduction of chemicals, particulate matter, or biological materials into the atmosphere, causing harm or discomfort to humans or other living organisms, or damaging ecosystems. Air pollution can cause health problems in ...

(down from their 2000 ranking as the second-greatest). In 2008, the company released more than one million kg (2.2 million pounds) of toxins, chiefly ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogeno ...

, hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid. It is a component of the gastric acid in the dig ...

, ethylene

Ethylene ( IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene ...

, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic t ...

compounds, methanol, and benzene

Benzene is an organic chemical compound with the molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. Because it contains only carbon and hydrogen ato ...

, but including manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy u ...

, cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

, and chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and h ...

compounds. In 2004, the city of River Rouge, Michigan

River Rouge (, french: link=no, Rivière Rouge, translation=red river) is a city in Wayne County in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 7,224 at the 2020 census.

The city is named after the River Rouge, which flows along the city's ...

, and the residents of River Rouge and the nearby city of Ecorse filed a class-action lawsuit

A class action, also known as a class-action lawsuit, class suit, or representative action, is a type of lawsuit where one of the parties is a group of people who are represented collectively by a member or members of that group. The class action ...

against the company for "the release and discharge of air particulate matter...and other toxic and hazardous substances" at its River Rouge plant.

The company has also been implicated in generating water pollution

Water pollution (or aquatic pollution) is the contamination of water bodies, usually as a result of human activities, so that it negatively affects its uses. Water bodies include lakes, rivers, oceans, aquifers, reservoirs and groundwater. Wate ...

and toxic waste

Toxic waste is any unwanted material in all forms that can cause harm (e.g. by being inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the skin). Mostly generated by industry, consumer products like televisions, computers, and phones contain toxic chemi ...

. In 1993, the Environmental Protection Agency

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

(EPA) issued an order for U.S. Steel to clean up a site on the Delaware River in Fairless Hills, Pennsylvania

Fairless Hills is a census-designated place (CDP) in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States. The CDP is located within c. The population was 9,046 at the 2020 census. That is up from 8,466 at the 2010 census.

History

Fairless Hills as it is ...

, where the soil had been contaminated with arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, bu ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metals, heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale of mineral hardness#Intermediate ...

, and other heavy metals

upright=1.2, Crystals of lead.html" ;"title="osmium, a heavy metal nearly twice as dense as lead">osmium, a heavy metal nearly twice as dense as lead

Heavy metals are generally defined as metals with relatively high density, densities, atomi ...

, as well as naphthalene

Naphthalene is an organic compound with formula . It is the simplest polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, and is a white crystalline solid with a characteristic odor that is detectable at concentrations as low as 0.08 ppm by mass. As an aromat ...

. Groundwater at the site was found to be polluted with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

A polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) is a class of organic compounds that is composed of multiple aromatic rings. The simplest representative is naphthalene, having two aromatic rings and the three-ring compounds anthracene and phenanthrene. ...

s and trichloroethylene

The chemical compound trichloroethylene is a halocarbon commonly used as an industrial solvent. It is a clear, colourless non-flammable liquid with a chloroform-like sweet smell. It should not be confused with the similar 1,1,1-trichloroethane, ...

(TCE). In 2005, the EPA, United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a United States federal executive departments, federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and a ...

, and the State of Ohio reached a settlement requiring U.S. Steel to pay more than $100,000 in penalties and $294,000 in reparations in answer to allegations that the company illegally released pollutants into Ohio waters. U.S. Steel's Gary, Indiana

Gary is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. The city has been historically dominated by major industrial activity and is home to U.S. Steel's Gary Works, the largest steel mill complex in North America. Gary is located along the ...

facility has been repeatedly charged with discharging polluted wastewater into Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that ...

and the Grand Calumet River

The Grand Calumet River is a river that flows primarily into Lake Michigan. Originating in Miller Beach in Gary, it flows through the cities of Gary, East Chicago and Hammond, as well as Calumet City and Burnham on the Illinois side. The major ...

. In 1998 the company agreed to payment of a $30 million settlement to clean up contaminated sediments from a five-mile (8 km) stretch of the river.

With the exception of the Fairless Hills and Gary facilities, the lawsuits concern facilities acquired by U.S. Steel via its 2003 purchase of National Steel Corporation, not its historic facilities.

Legacy

U.S. Steel Tower

The U.S. Steel Tower inPittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

, is named after the company and since 1970, the company's corporate headquarters have been located there. It is the tallest skyscraper in the downtown Pittsburgh

Downtown Pittsburgh, colloquially referred to as the Golden Triangle, and officially the Central Business District, is the urban downtown center of Pittsburgh. It is located at the confluence of the Allegheny River and the Monongahela River whose ...

skyline, built out of the company's Corten Steel. New York City's One Liberty Plaza was also built by the corporation as that city's U.S. Steel Tower in 1973.

Steelmark logo

Pittsburgh Steelers

The Pittsburgh Steelers are a professional American football team based in Pittsburgh. The Steelers compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the American Football Conference (AFC) North division. Founded in , the Stee ...

professional football team borrowed elements of its logo, a circle containing three hypocycloid

In geometry, a hypocycloid is a special plane curve generated by the trace of a fixed point on a small circle that rolls within a larger circle. As the radius of the larger circle is increased, the hypocycloid becomes more like the cycloid ...

s, from the Steelmark logo belonging to the American Iron and Steel Institute

The American Iron and Steel Institute is an association of North American steel producers. With its predecessor organizations, is one of the oldest trade associations in the United States, dating back to 1855. It assumed its present form in 1908 ...

(AISI) and created by U.S. Steel. In the 1950s, when helmet logos became popular, the Steelers added players' numbers to either side of their gold helmets. Later that decade, the numbers were removed and in 1962, Cleveland's Republic Steel

Republic Steel is an American steel manufacturer that was once the country's third largest steel producer. It was founded as the Republic Iron and Steel Company in Youngstown, Ohio in 1899. After rising to prominence during the early 20th Cen ...

suggested to the Steelers that they use the Steelmark as a helmet logo.

U.S. Steel financed and constructed the Unisphere

The Unisphere is a spherical stainless steel representation of the Earth in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in the New York City borough of Queens. The globe was designed by Gilmore D. Clarke as part of his plan for the 1964 New York World' ...

in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, for the 1964 World's Fair

The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair was a world's fair that held over 140 pavilions and 110 restaurants, representing 80 nations (hosted by 37), 24 US states, and over 45 corporations with the goal and the final result of building exhibits o ...

. It is the largest globe ever made and is one of the world's largest free-standing sculptures.

Fabrication of Chicago Picasso sculpture

The Chicago Picasso sculpture was fabricated by U.S. Steel in Gary, Indiana, before being disassembled and relocated to Chicago. U.S. Steel donated the steel for the construction of St. Michael's Catholic Church in Chicago since 90 percent of the parishioners worked at its mills.''United States Steel Hour'' television program and Walt Disney World involvement

U.S. Steel sponsored ''The United States Steel Hour

''The United States Steel Hour'' is an anthology series which brought hour long dramas to television from 1953 to 1963. The television series and the radio program that preceded it were both sponsored by the U.S. Steel, United States Steel Corpor ...

'' television program from 1945 until 1963 on CBS. U.S. Steel built both the Disney's Contemporary Resort

Disney's Contemporary Resort, originally to be named Tempo Bay Hotel and previously the Contemporary Resort Hotel, is a resort located at the Walt Disney World Resort in Bay Lake, Florida. Opened on October 1, 1971, the hotel is one of two o ...

and the Disney's Polynesian Resort in 1971 at Walt Disney World

The Walt Disney World Resort, also called Walt Disney World or Disney World, is an entertainment resort complex in Bay Lake and Lake Buena Vista, Florida, United States, near the cities of Orlando and Kissimmee. Opened on October 1, 1971, ...

, in part to showcase its residential steel building "modular" products to high-end and luxury consumers.

This same U.S. Steel manufacturing plant that was located on Disney property also helped build the now defunct Court of Flags Resort in Orlando, Florida, on Major Blvd.

Real estate development

U.S. Steel was also involved with Floridareal estate development

Real estate development, or property development, is a business process, encompassing activities that range from the renovation and re-lease of existing buildings to the purchase of raw land and the sale of developed land or parcels to others. R ...

including building beachfront condominiums during the 1970s, such as Sand Key near Daytona Beach, Florida, and the Pasadena Yacht and Country Club near St. Petersburg, Florida.

Facilities

U.S. Steel has multiple domestic and international facilities.

Of note in the United States is Clairton Works, Edgar Thomson Works, and Irvin Plant, which are all members of Mon Valley Works just outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Clairton Works is the largest coking facility in North America. Edgar Thomson Works is one of the oldest steel mills in the world. The company acquired Great Lakes Works and Granite City Works, both large integrated steel mills, in 2003 and is partnered with Severstal North America in operating the world's largest electro-galvanizing line, Double Eagle Steel Coating Company at the historic Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan.

U.S. Steel's largest domestic facility is

U.S. Steel has multiple domestic and international facilities.

Of note in the United States is Clairton Works, Edgar Thomson Works, and Irvin Plant, which are all members of Mon Valley Works just outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Clairton Works is the largest coking facility in North America. Edgar Thomson Works is one of the oldest steel mills in the world. The company acquired Great Lakes Works and Granite City Works, both large integrated steel mills, in 2003 and is partnered with Severstal North America in operating the world's largest electro-galvanizing line, Double Eagle Steel Coating Company at the historic Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan.

U.S. Steel's largest domestic facility is Gary Works

The Gary Works is a major steel mill in Gary, Indiana, on the shore of Lake Michigan. For many years, the Gary Works was the world's largest steel mill, and it remains the largest integrated mill in North America. It is operated by the United St ...

, in Gary, Indiana

Gary is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. The city has been historically dominated by major industrial activity and is home to U.S. Steel's Gary Works, the largest steel mill complex in North America. Gary is located along the ...

, on the shore of Lake Michigan. For many years, the Gary Works Plant was the world-largest steel mill and it remains the largest integrated mill in North America. It was built in 1906 and has been operating since June 28, 1908. Gary is also home to the U.S. Steel Yard

U.S. Steel Yard is an open-air baseball stadium located in Gary, Indiana next to I-90 in the city's Emerson neighborhood. It is home to the Gary SouthShore RailCats, a professional baseball team and member of the American Association. It seats ...

baseball stadium.

U.S. Steel operates a tin mill in East Chicago now known as East Chicago Tin. The mill was idled in 2015, but reopened shortly after. The mill was then 'permanently idled' in 2019, however the facility remains in possession of the corporation as of early 2020.

U.S. Steel operates a sheet and tin finishing facility in Portage, Indiana

Portage ( ) is a city in Portage Township, Porter County, in the U.S. state of Indiana, on the border with Lake County. The population was 37,926 as of the 2020 census. It is the largest city in Porter County, and third largest in Northwest In ...

, known as Midwest Plant, acquired after the National Steel Corporation bankruptcy. U.S. Steel acquired National Steel Corporation in May 2003 for $850 million and assumption of $200 million in debt. U.S. Steel operates Great Lakes Works in Ecorse, Michigan

Ecorse ( ') is a city in Wayne County in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 9,512 at the 2010 census.

Ecorse is part of the Downriver community within Metro Detroit. The city shares a northwestern border with the city of Detroit ...

, Midwest Plant in Portage, Indiana, and Granite City Steel in Granite City, Illinois

Granite City is a city in Madison County, Illinois, United States, within the Greater St. Louis metropolitan area. The population was 27,549 at the 2020 census, making it the third-largest city in the Metro East and Southern Illinois regio ...

. In 2008 a major expansion of Granite City was announced, including a new coke plant with an annual capacity of 650,000 tons.

U.S. Steel operates Fairfield Works in Fairfield, Alabama

Fairfield is a city in western Jefferson County, Alabama, United States. It is part of the Birmingham metropolitan area and is located southeast of Pleasant Grove. The population was 11,117 at the 2010 census.

History

This city was founded ...

(Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

), employing 1,500 people, and operates a sheet galvanizing operation at the Fairless Works facility in Fairless Hills, Pennsylvania

Fairless Hills is a census-designated place (CDP) in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States. The CDP is located within c. The population was 9,046 at the 2020 census. That is up from 8,466 at the 2010 census.

History

Fairless Hills as it is ...

, employing 75 people.

U.S. Steel operates three pipe mills: Fairfield Tubular Operations in Fairfield, Alabama

Fairfield is a city in western Jefferson County, Alabama, United States. It is part of the Birmingham metropolitan area and is located southeast of Pleasant Grove. The population was 11,117 at the 2010 census.

History

This city was founded ...

(Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

), McKeesport Tubular Operations, in McKeesport, Pennsylvania

McKeesport is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is situated at the confluence of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny rivers and within the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. The population was 17,727 as of the 2020 census. I ...

, and Texas Operations (Formerly Lone Star Steel) in Lone Star, Texas. A fourth pipe mill, Lorain Tubular Operations in Lorain, Ohio

Lorain () is a city in Lorain County, Ohio, United States. The municipality is located in northeastern Ohio on Lake Erie, at the mouth of the Black River, about 30 miles west of Cleveland. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of ...

is no longer operating at this time.

U.S. Steel operates two major taconite

Taconite () is a variety of iron formation, an iron-bearing (over 15% iron) sedimentary rock, in which the iron minerals are interlayered with quartz, chert, or carbonate. The name "taconyte" was coined by Horace Vaughn Winchell (1865–1923) � ...

mining and pelletizing operations in northeastern Minnesota's Iron Range

The term Iron Range refers collectively or individually to a number of elongated iron-ore mining districts around Lake Superior in the United States and Canada. Much of the ore-bearing region lies alongside the range of granite hills formed by ...

under the operating name Minnesota Ore Operations. The Minntac mine is located near Mountain Iron, Minnesota

Mountain Iron is a city in Saint Louis County, Minnesota, United States, in the heart of the Mesabi Range. The population was 2,878 at the 2020 census.

U.S. Highway 169 serves as a main route in Mountain Iron.

The city's motto is "Taconite C ...

, and the Keetac mine is near Keewatin, Minnesota. U.S. Steel announced on February 1, 2008, that it would be investing approximately $300 Million in upgrading (project later abandoned) the operations at Keetac, a facility purchased in 2003 from the now-defunct National Steel Corporation.

U.S. Steel has completely closed nine of its major integrated mills. The Duluth Works in Duluth, Minnesota

, settlement_type = City

, nicknames = Twin Ports (with Superior), Zenith City

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top: urban Duluth skyline; Minnesota ...

, closed in 1973. The Ohio Works and Macdonald Works in Youngstown, Ohio

Youngstown is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio, and the largest city and county seat of Mahoning County, Ohio, Mahoning County. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, Youngstown had a city population of 60,068. It is a principal city of ...

, closed in 1980, the Duquesne Works in Duquesne, Pennsylvania

Duquesne ( ) is a city along the Monongahela River in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, within the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. The population was 5,254 at the 2020 census.

History

The city of Duquesne was settled in 1789 and incor ...

, and Ensley Works in Ensley, Alabama in 1984, the Homestead Works in Homestead, Pennsylvania

Homestead is a borough in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA, in the Monongahela River valley southeast of downtown Pittsburgh and directly across the river from the city limit line. The borough is known for the Homestead Strike of 1892, an i ...

, in 1986. Geneva Steel

Geneva Steel was a steel mill located in Vineyard, Utah, United States, founded during World War II to enhance national steel output. It operated from December 1944 to November 2001. Its unique name came from a resort that once operated nearby on ...

in Vineyard, Utah

Vineyard is a city in Utah County, Utah, United States. It is part of the Provo– Orem Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population grew from 139 at the 2010 census to 12,543 at the 2020 census making it the fastest growing city in Ut ...

, was sold in 1987, South Chicago

South Chicago, formerly known as Ainsworth, is one of the 77 community areas of Chicago, Illinois.

This chevron-shaped community is one of Chicago's 16 lakefront neighborhoods near the southern rim of Lake Michigan 10 miles south of downtown ...

's South Works

South Works is an area in the South Chicago part of Chicago, Illinois, near the mouth of the Calumet River, that was previously home to a now-closed and vacant US Steel manufacturing plant. The area is called "South Works" because that was the ...

closed in 1992, followed by the National Tube Works in Mckeesport, Pennsylvania

McKeesport is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is situated at the confluence of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny rivers and within the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. The population was 17,727 as of the 2020 census. I ...

, in 2014.

Internationally, U.S. Steel operates facilities in Slovakia (former East Slovakian Iron Works in Košice

Košice ( , ; german: Kaschau ; hu, Kassa ; pl, Коszyce) is the largest city in eastern Slovakia. It is situated on the river Hornád at the eastern reaches of the Slovak Ore Mountains, near the border with Hungary. With a population of a ...

). It also operated facilities in Serbia – former Sartid with facilities in Smederevo

Smederevo ( sr-Cyrl, Смедерево, ) is a city and the administrative center of the Podunavlje District in eastern Serbia. It is situated on the right bank of the Danube, about downstream of the Serbian capital, Belgrade.

According t ...

(steel plant, hot and cold mill) and Šabac

Šabac (Serbian Cyrillic: Шабац, ) is a city and the administrative centre of the Mačva District in western Serbia. The traditional centre of the fertile Mačva region, Šabac is located on the right banks of the river Sava. , the city p ...

(tin mill).

U.S. Steel added facilities in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

with the purchase of Lone Star Steel Company in 2007.

The company operates two joint ventures in Pittsburg, California

Pittsburg is a city in Contra Costa County, California, United States. It is an industrial suburb located on the southern shore of the Suisun Bay in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, and is part of the Sacramento–San Joaquin R ...

, with POSCO

POSCO (formerly Pohang Iron and Steel Company) is a South Korean steel-making company headquartered in Pohang, South Korea. It had an output of of crude steel in 2015, making it the world's fourth-largest steelmaker by this measure. In 2010, ...

of South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

.

U.S. Steel added facilities in Hamilton and Nanticoke, Ontario Nanticoke is an unincorporated community and former city located on the western border of Haldimand County, Ontario, Canada. Nanticoke is located directly across Lake Erie from the US city of Erie, Pennsylvania.

Summary

Unlike the majority of Haldi ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

, with the purchase of Stelco

Stelco Holdings Inc. (known as U.S. Steel Canada from 2007 to 2016) is a Canadian steel company based in Hamilton, Ontario. Stelco was founded in 1910 from the amalgamation of several smaller firms. It continued on for almost 100 years, until i ...

(now U.S. Steel Canada) in 2007. These facilities were sold in 2016 to venture capital firm Bedrock Resources and has since been renamed Stelco. The blast furnaces in Hamilton have not been reactivated as they were shut down by U.S. Steel in 2013, but those at Nanticoke are functional.

The company opened a training facility, the Mon Valley Works Training Hub, in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, in 2008. The state-of-the-art facility, located on a portion of the property once occupied by the company's Duquesne Works, serves as the primary training site for employees at U.S. Steel's three Pittsburgh-area Mon Valley Works locations. This site also served as the company's temporary technical support headquarters during the 2009 G20 Summit.

List of presidents and chairmen

Presidents

* Charles M. Schwab (1901–1903) * Elbert H. Gary (1903–1911) *James Augustine Farrell, Sr.

James Augustine Farrell Sr. (February 15, 1863 – March 28, 1943) was president of US Steel from 1911 to 1932. A major business figure of his era, Farrell expanded US Steel by a factor of five during his presidency, turning it into America's f ...

– (1911–1932)

* William A. Irvin (19 April 1932 – 1 January 1938)

*Benjamin Franklin Fairless

Benjamin Franklin Fairless (May 3, 1890 — January 1, 1962) was an American steel company executive. He was president of a wide range of steel companies during a turbulent and formative period in the American steel industry. His roles included ...

(1938–1952)

*Clifford Hood (1952–1959)

*Walter Munford (18 May 1959 – 29 September 1959)

*Leslie B. Worthington (1959–1967)

*Edwin H. Gott (1967–1969)

*Edgar B. Speer (1969–1973)

*David M. Roderick (1973–1979)

*William R. Roesch (1979–1983)

*Charles A. Corry (25 January 1988 – 31 May 1989)

* Thomas J. Usher (1994–1995)

*Paul J. Wilhelm (1994–2001)

*Thomas J. Usher (2001–2003)

* John Surma (2003–2013)

* Mario Longhi— President & CEO of U.S. Steel (September 1, 2013 – May 10, 2017)

* David Burritt— President & CEO (May 10, 2017 – present)

Chairmen of the Board of Directors

*Elbert Henry Gary (1901–1927) * J.P. Morgan Jr. (1927–1932) * Myron C. Taylor (1932–1938) * Edward Stettinius Jr. (1938–1940) * Irving Sands Olds (1940–1952) *Benjamin Franklin Fairless

Benjamin Franklin Fairless (May 3, 1890 — January 1, 1962) was an American steel company executive. He was president of a wide range of steel companies during a turbulent and formative period in the American steel industry. His roles included ...

— Chairman & CEO of U.S. Steel (1952–1955)

* Roger Blough— Chairman & CEO (3 May 1955 – 31 January 1969)

*Edwin H. Gott— Chairman & CEO (January 31, 1969 – March 1, 1973)

*Edgar B. Speer— Chairman & CEO (March 1, 1973 – April 24, 1979)

*David M. Roderick— Chairman & CEO (April 24, 1979 – May 31, 1989)

*Charles A. Corry— Chairman & CEO (May 31, 1989 – July 1, 1995)

* Thomas Usher— Chairman & CEO (July 1, 1995 – October 1, 2004)

* John Surma— Chairman & CEO (October 1, 2004 – December 31, 2013)

* David S. Sutherland— Non-executive Chairman of the Board (2014—present)

See also

* History of the steel industry (1850–1970) * Iron and steel industry in the United States *Weathering steel

Weathering steel, often referred to by the genericised trademark COR-TEN steel and sometimes written without the hyphen as corten steel, is a group of steel alloys which were developed to eliminate the need for painting, and form a stable r ...

References

Bibliography

* Brawley, Mark R. " 'And we would have the field': US Steel and American trade policy, 1908–1912." ''Business and Politics'' 19.3 (2017): 424-453. * * * Hall, Christopher G.L. ''Steel phoenix: The fall and rise of the US steel industry'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 1997) * * * * * Seely, Bruce Edsall, ed. ''Iron and Steel in the Twentieth Century'' (Facts on File, 1994) 512pp, an encyclopedia * * * * Warren, Kenneth. ''The American steel industry, 1850–1970: a geographical interpretation'' (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1987) *External links

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *U.S. Steel Gary Works Photograph Collection, 1906–1971

* ttp://www.steelonthenet.com/kb/history-us-steel.html History of the United States Steel Corporation, 1873–2011br>Guide to United States Steel Corporation. Training manuals. 5342. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University.

Archives and records

United States Steel Corporation photographs

at Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School. {{Authority control Manufacturing companies established in 1901 Metals monopolies Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange Former components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average Historic American Engineering Record in Pennsylvania 1901 establishments in Pennsylvania 1901 mergers and acquisitions