United States presidential election, 1920 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wilson had hoped for a "solemn referendum" on the

Wilson had hoped for a "solemn referendum" on the  This was the first election in which women from every state were allowed to vote, following the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in August 1920 (just in time for the general election).

Tennessee's vote for Warren G. Harding marked the first time since the end of

This was the first election in which women from every state were allowed to vote, following the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in August 1920 (just in time for the general election).

Tennessee's vote for Warren G. Harding marked the first time since the end of

The total vote for 1920 was roughly 26,750,000, an increase of eight million from

The total vote for 1920 was roughly 26,750,000, an increase of eight million from

online

* Daniel, Douglass K. "Ohio Newspapers and the 'Whispering Campaign' of the 1920 Presidential Election." ''Journalism History'' 27.4 (2002): 156-164. * * * * * * * Frederick, Richard G. "The Front Porch Campaign and the Election of Harding." in ''A Companion to Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover'' (2014): 94-111. * * Walters, Ryan S. ''The Jazz Age President: Defending Warren G. Harding'' (2022

excerpt

als

online review

online

* Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. ''National party platforms, 1840–1964'' (1965

online 1840–1956

* Eugene V. Debs

''A Word to the Workers!''

New York: New York Call, n.d.

Presidential Election of 1920: A Resource Guide

from the Library of Congress

{{Authority control Presidency of Warren G. Harding Warren G. Harding Calvin Coolidge Franklin D. Roosevelt

The 1920 United States presidential election was the 34th quadrennial

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteFirstBallot1920.svg, First Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteSecondBallot1920.svg, Second Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteThirdBallot1920.svg, Third Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteFourthBallot1920.svg, Fourth Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteFifthBallot1920.svg, Fifth Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteSixthBallot1920.svg, Sixth Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteSeventhBallot1920.svg, Seventh Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteEighthBallot1920.svg, Eighth Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteNinthBallot1920.svg, Ninth Presidential Ballot

File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteTenthBallotBeforeShifts1920.svg, Tenth Presidential Ballot

Before Shifts File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteTenthBallotAfterShifts1920.svg, Tenth Presidential Ballot

After Shifts

Harding's nomination, said to have been secured in negotiations among party bosses in a "

It was widely accepted prior to the election that President Woodrow Wilson would not run for a third term, and would certainly not be nominated if he did make an attempt to regain the nomination. While Vice-President Thomas R. Marshall had long held a desire to succeed Wilson, his indecisive handling of the situation around Wilson's illness and incapacity destroyed any credibility he had as a candidate, and in the end he did not formally put himself forward for the nomination.

Although

It was widely accepted prior to the election that President Woodrow Wilson would not run for a third term, and would certainly not be nominated if he did make an attempt to regain the nomination. While Vice-President Thomas R. Marshall had long held a desire to succeed Wilson, his indecisive handling of the situation around Wilson's illness and incapacity destroyed any credibility he had as a candidate, and in the end he did not formally put himself forward for the nomination.

Although

) voted in June 1920 to spend $500,000 on the American presidential election. How this money was spent remains unclear. Ironically, the lawyer who had advised the fundraisers was Franklin D. Roosevelt, the losing vice-presidential candidate. In any case, the Irish American city machines sat on their hands during the election, allowing the Republicans to roll up unprecedented landslides in every major city. Many German-American Democrats voted Republican or stayed home, giving the GOP landslides in the rural Midwest.

presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...

, held on Tuesday, November 2, 1920. In the first election held after the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the first election after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

defeated Democratic Governor James M. Cox

James Middleton Cox (March 31, 1870 July 15, 1957) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 46th and 48th governor of Ohio, and a two-term U.S. Representative from Ohio. As the Democratic nominee for President of the United St ...

of Ohio.

Incumbent Democratic President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

privately hoped for a third term, but party leaders were unwilling to re-nominate the ailing and unpopular incumbent. Former President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

had been the front-runner for the Republican nomination, but he died in 1919 without leaving an obvious heir to his progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

legacy. With both Wilson and Roosevelt out of the running, the major parties turned to little-known dark horse

A dark horse is a previously lesser-known person or thing that emerges to prominence in a situation, especially in a competition involving multiple rivals, or a contestant that on paper should be unlikely to succeed but yet still might.

Origin

Th ...

candidates from the state of Ohio, a swing state with a large number of electoral votes. Cox won the 1920 Democratic National Convention

Nineteen or 19 may refer to:

* 19 (number), the natural number following 18 and preceding 20

* one of the years 19 BC, AD 19, 1919, 2019

Films

* ''19'' (film), a 2001 Japanese film

* ''Nineteen'' (film), a 1987 science fiction film

Music ...

on the 44th ballot, defeating William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

(Wilson's son-in-law), A. Mitchell Palmer

Alexander Mitchell Palmer (May 4, 1872 – May 11, 1936), was an American attorney and politician who served as the 50th United States attorney general from 1919 to 1921. He is best known for overseeing the Palmer Raids during the Red Scare ...

, and several other candidates. Harding emerged as a compromise candidate between the conservative and progressive wings of the party, and he clinched his nomination on the tenth ballot of the 1920 Republican National Convention

The 1920 Republican National Convention nominated Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding for president and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge for vice president. The convention was held in Chicago, Illinois, at the Chicago Coliseum from June 8 to J ...

.

The election was dominated by the American social and political environment in the aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, ne ...

, which was marked by a hostile response to certain aspects of Wilson's foreign policy and a massive reaction against the reformist zeal of the Progressive Era. The wartime economic boom had collapsed and the country was deep in a recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

. Wilson's advocacy for America's entry into the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in the face of a return to non-interventionist opinion challenged his effectiveness as president, and overseas there were wars and revolutions. At home, the year 1919 was marked by major strikes in the meatpacking and steel industries and large-scale race riots in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and other cities. Anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

attacks on Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for t ...

produced fears of radicals and terrorists. The Irish Catholic and German communities were outraged at Wilson's perceived favoritism of their traditional enemy Great Britain, and his political position was critically weakened after he suffered a stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

in 1919 that left him severely disabled.

Harding all but ignored Cox in the race and essentially campaigned against Wilson by calling for a "return to normalcy

"Return to normalcy" was a campaign slogan used by Warren G. Harding during the 1920 United States presidential election. Harding would go on to win the election with 60.4% of the popular vote.

1920 election

In a speech delivered on May 14, 19 ...

". Harding won a landslide victory

A landslide victory is an election result in which the victorious candidate or party wins by an overwhelming margin. The term became popular in the 1800s to describe a victory in which the opposition is "buried", similar to the way in which a geol ...

, sweeping every state outside of the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

and becoming the first Republican since the end of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

to win a former state of the Confederacy, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

. Harding's victory margin of 26.2% in the popular vote remains the largest popular-vote percentage margin in presidential elections since the unopposed re-election of James Monroe in 1820

Events

January–March

*January 1 – Nominal beginning of the Trienio Liberal in Spain: A constitutionalist military insurrection at Cádiz leads to the summoning of the Spanish Parliament (March 7).

*January 8 – General Maritime T ...

, though other candidates have since exceeded his share of the popular vote. Cox won just 34.1% of the popular vote, and Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialism, socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate ...

won 3.4%, despite being in prison at the time. It was also the first election in which women had the right to vote in all 48 states, which caused the total popular vote to increase dramatically, from 18.5 million in 1916 to 26.8 million in 1920. Both vice presidential nominees would eventually become president in their own right (which had never happened before or since): Harding died in 1923 and was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

, while the Democratic vice presidential nominee, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, would eventually win an unprecedented four consecutive presidential elections starting in 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident (1932), Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort ...

, dying shortly into his fourth term.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Other Candidates

Following the return of former presidentTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

to the Republican Party after the previous election, speculation quickly grew as to whether he would make another run for the presidency. Roosevelt's health declined seriously in 1918, however, and he died on January 6, 1919. Attention then turned to the party's unsuccessful 1916 candidate, Charles Evans Hughes, who had narrowly fallen short of defeating Wilson that year, but Hughes remained aloof as to the prospect of another run, and ultimately ruled himself out following the death of his daughter early in 1920.

On June 8, the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the United States Republican Party. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal of the Repu ...

met in Chicago. The race was wide open, and soon the convention deadlocked between Major General Leonard Wood and Governor Frank Orren Lowden

Frank Orren Lowden (January 26, 1861 – March 20, 1943) was an American Republican Party politician who served as the 25th Governor of Illinois and as a United States Representative from Illinois. He was also a candidate for the Republican pre ...

of Illinois.

Other names placed in nomination included Senators Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

from Ohio, Hiram Johnson from California, and Miles Poindexter

Miles Poindexter (April 22, 1868September 21, 1946) was an American lawyer and politician. As a Republican and briefly a Progressive, he served one term as a United States representative from 1909 to 1911, and two terms as a United States senato ...

from Washington, Governor Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

of Massachusetts, philanthropist Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, and Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

President Nicholas M. Butler

Nicholas Murray Butler () was an American philosopher, diplomat, and educator. Butler was president of Columbia University, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, and the deceased J ...

. Senator Robert M. La Follette from Wisconsin was not formally placed in nomination, but received the votes of his state delegation nonetheless. Harding was nominated for president on the tenth ballot, after some delegates shifted their allegiances. The results of the ten ballots were as follows:

Before Shifts File:RepublicanPresidentialConventionVoteTenthBallotAfterShifts1920.svg, Tenth Presidential Ballot

After Shifts

smoke-filled room

In U.S. political jargon, a smoke-filled room (sometimes called a smoke-filled back room) is an exclusive, sometimes secret political gathering or round-table-style decision-making process. The phrase is generally used to suggest an inner circl ...

," was engineered by Harry M. Daugherty

Harry Micajah Daugherty (; January 26, 1860 – October 12, 1941) was an American politician. A key Ohio Republican political insider, he is best remembered for his service as Attorney General of the United States under Presidents Warren G. Hardin ...

, Harding's political manager, who became United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

after his election. Before the convention, Daugherty was quoted as saying, "I don't expect Senator Harding to be nominated on the first, second, or third ballots, but I think we can afford to take chances that about 11 minutes after two, Friday morning of the convention, when 15 or 12 weary men are sitting around a table, someone will say: 'Who will we nominate?' At that decisive time, the friends of Harding will suggest him and we can well afford to abide by the result." Daugherty's prediction described essentially what occurred, but historians Richard C. Bain and Judith H. Parris argue that Daugherty's prediction has been given too much weight in narratives of the convention.

Once the presidential nomination was finally settled, the party bosses and Sen. Harding recommended Wisconsin Sen. Irvine Lenroot

Irvine Luther Lenroot (January 31, 1869 – January 26, 1949) was a United States representative and United States senator from Wisconsin and an associate judge of the United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals.

Education and career

...

to the delegates for the second spot, but the delegates revolted and nominated Coolidge, who was very popular over his handling of the Boston Police Strike from the year before. The Tally:

Source for convention coverage: Richard C. Bain and Judith H. Parris, ''Convention Decisions and Voting Records'' (Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 1973), pp. 200–208.

Democratic Party nomination

Other Candidates

It was widely accepted prior to the election that President Woodrow Wilson would not run for a third term, and would certainly not be nominated if he did make an attempt to regain the nomination. While Vice-President Thomas R. Marshall had long held a desire to succeed Wilson, his indecisive handling of the situation around Wilson's illness and incapacity destroyed any credibility he had as a candidate, and in the end he did not formally put himself forward for the nomination.

Although

It was widely accepted prior to the election that President Woodrow Wilson would not run for a third term, and would certainly not be nominated if he did make an attempt to regain the nomination. While Vice-President Thomas R. Marshall had long held a desire to succeed Wilson, his indecisive handling of the situation around Wilson's illness and incapacity destroyed any credibility he had as a candidate, and in the end he did not formally put himself forward for the nomination.

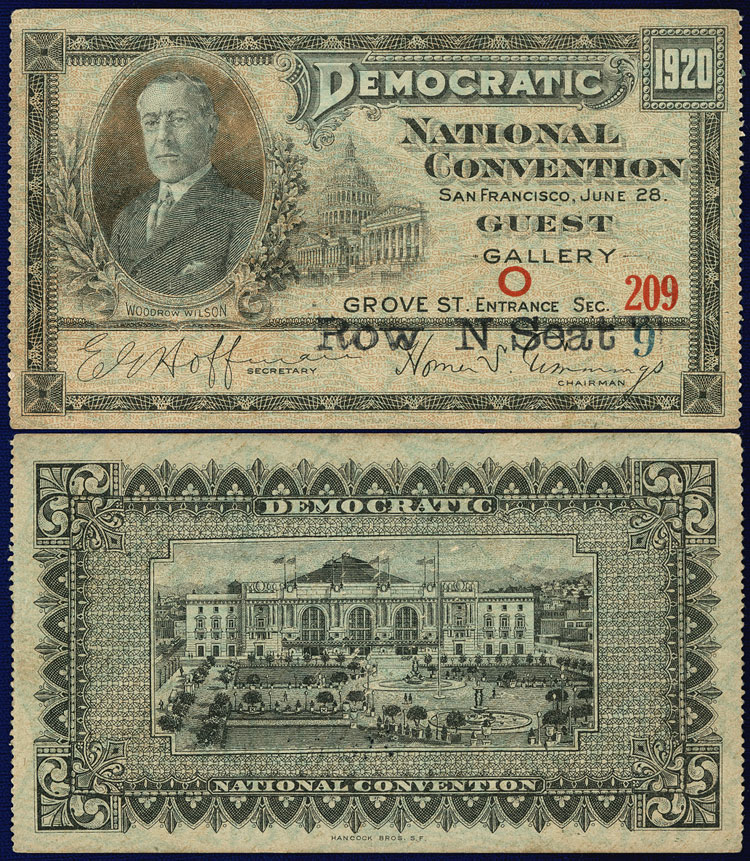

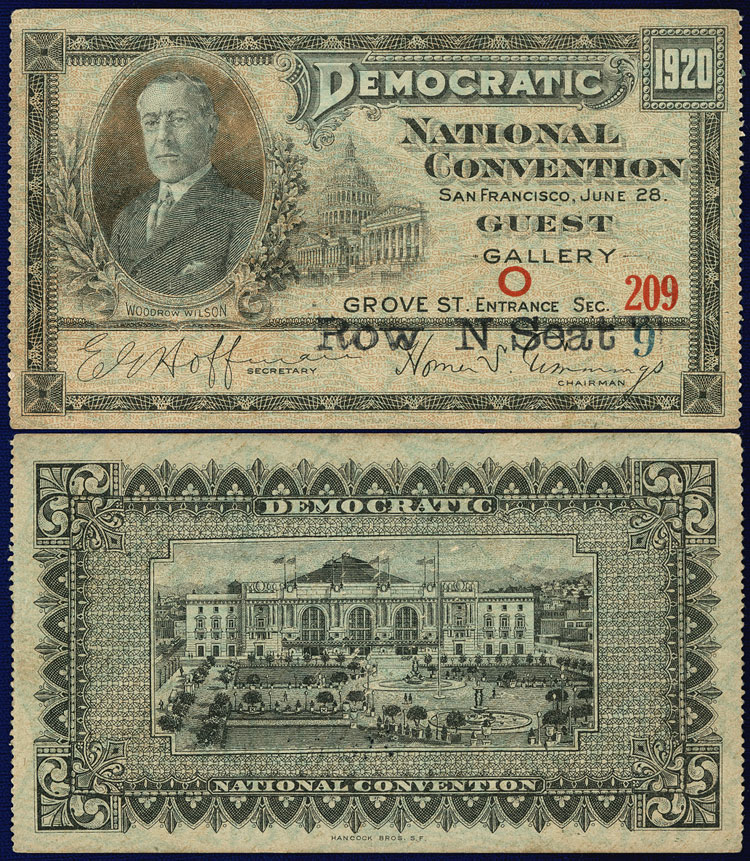

Although William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

(Wilson's son-in-law and former Treasury Secretary) was the strongest candidate, Wilson blocked his nomination in hopes a deadlocked convention would demand that he run for a third term, even though he was seriously ill, physically immobile, and in seclusion at the time. The Democrats, meeting in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

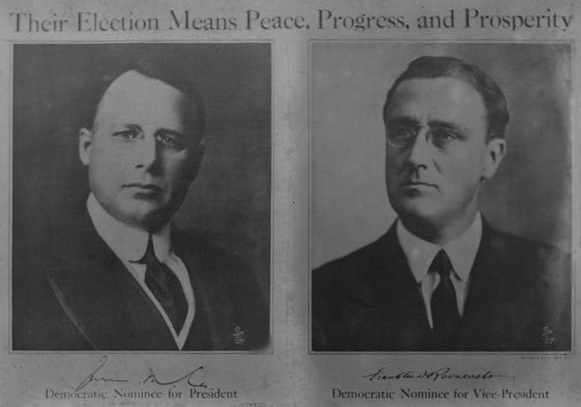

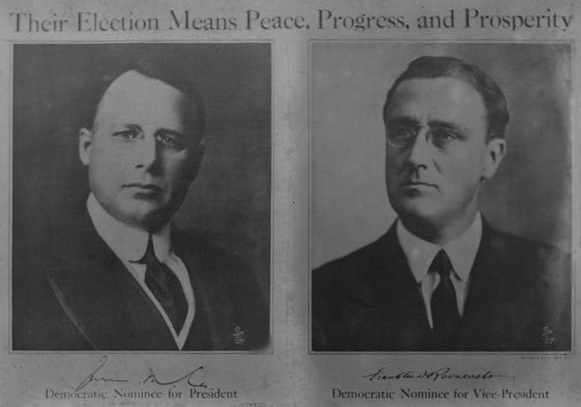

between June 28 and July 6 (the first time a major party held its nominating convention in an urban center on the Pacific coast), nominated another newspaper editor from Ohio, Governor James M. Cox

James Middleton Cox (March 31, 1870 July 15, 1957) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 46th and 48th governor of Ohio, and a two-term U.S. Representative from Ohio. As the Democratic nominee for President of the United St ...

, as their presidential candidate, and 38-year-old Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, a fifth cousin of the late president Theodore Roosevelt, for vice-president.

Early favorites for the nomination had included McAdoo and Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer

Alexander Mitchell Palmer (May 4, 1872 – May 11, 1936), was an American attorney and politician who served as the 50th United States attorney general from 1919 to 1921. He is best known for overseeing the Palmer Raids during the Red Scare ...

. Others placed in nomination included New York Governor Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

, United Kingdom Ambassador John W. Davis

John William Davis (April 13, 1873 – March 24, 1955) was an American politician, diplomat and lawyer. He served under President Woodrow Wilson as the Solicitor General of the United States and the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom ...

, New Jersey Governor Edward I. Edwards

Edward Irving Edwards (December 1, 1863 – January 26, 1931) was an American Democratic Party politician who served as the 37th governor of New Jersey from 1920 to 1923 and in the United States Senate from 1923 to 1929.

Life and career

Edwards ...

, and Oklahoma Senator Robert Latham Owen

Robert Latham Owen Jr. (February 2, 1856July 19, 1947) was one of the first two U.S. senators from Oklahoma. He served in the Senate between 1907 and 1925.

Born into affluent circumstances in antebellum Lynchburg, Virginia, the son of a railroa ...

.

Other candidates

Socialist Party

Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

candidate Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialism, socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate ...

was incarcerated at the Atlanta federal penitentiary at the time for advocating non-compliance with the draft during World War I. He received the largest number of popular votes ever received by a Socialist Party candidate in the United States, although not the largest percentage of the popular vote. Debs received double this percentage in the election of 1912

Events January

* January 1 – The Republic of China (1912–49), Republic of China is established.

* January 5 – The Prague Conference (6th All-Russian Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party) opens.

* January 6 ...

. The 1920 election was Debs's fifth and last attempt to become president.

In 1919, members of the Socialist Party who had come from Russian language federation of the party and other more radical groups within the party started to create their own papers and membership dues and cards. These members supported a platform that was similar to the Communist International and elected twelve of their members to the fifteen-member National Executive Committee. However, there was accusations of election irregularities and an Emergency Convention held on August 30, 1919, suspended seven of the party's twelve language federations and expelled the party affiliates in Michigan, Massachusetts, and Ohio. The more radical members of the party held a convention in New York City in June 1919, which was attended by 94 delegates from twenty states. A vote to create a new party was defeated by a vote of 55 to 38 causing 31 delegates to withdraw from the convention. These 31 delegates held their own convention in Chicago on September 1, where they founded the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

. The Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

attempted to give its presidential nomination to Debs, but he declined the nomination.

The Socialist Party held its 1919 convention in Chicago with 140 delegates in attendance. Twenty-six delegates, who were members of the party's left-wing, left the convention. These delegates attempted to unite with the Communist Party USA, but formed the Communist Labor Party of America

The Communist Labor Party of America (CLPA) was one of the organizational predecessors of the Communist Party USA.

The group was established at the end of August 1919 following a three-way split of the Socialist Party of America. Although a legal ...

on September 2, after those attempts failed.

The Socialist Party had 100,000 members before the splits, but it fell to 55,000 members while the Communist Party had 35,000 members and the Communist Labor Party had 10,000 members. The Communist Party claimed to have 60,000 members while the Communist Labor Party claimed to have 30,000 members. The United Communist Party was formed in May 1920 between the Communist Labor Party and some members of the Communist Party. The United Communist Party and the Communist Party united in December 1921 to form the Workers Party of America

The Workers Party of America (WPA) was the name of the legal party organization used by the Communist Party USA from the last days of 1921 until the middle of 1929.

Background

As a legal political party, the Workers Party accepted affiliation fr ...

.

Edward Henry, who was a friend of Debs, Lena Morrow Lewis, and Oscar Ameringer

Oscar Ameringer (August 4, 1870 – November 5, 1943) was a German-American Socialist editor, author, and organiser from the late 1890s until his death in 1943. Ameringer made a name for himself in the Socialist Party of Oklahoma as the editor of ...

nominated Debs for the party's nomination on May 13, 1920, and the 134 delegates to the national convention voted unanimously to give him the nomination. Kate Richards O'Hare

Carrie Katherine "Kate" Richards O'Hare (March 26, 1876 – January 10, 1948) was an American Socialist Party activist, editor, and orator best known for her controversial imprisonment during World War I.

Biography

Early years

Carrie Katherin ...

, who was also in prison, was considered for the vice-presidential nomination, but Seymour Stedman

Seymour "Stedy" Stedman (July 4, 1871 – July 9, 1948) was an American from Chicago who rose from shepherd and janitor to become a prominent civil liberties lawyer and a leader of the Socialist Party of America. He is best remembered as the 192 ...

was selected by a vote of 106 to 26, which was later made unanimous, in order to have one of the candidates campaign. James H. Maurer was also considered for the vice-presidential nomination, but he declined due to his duties as head of the Pennsylvania Federation of Labor. Debs accepted the presidential nomination in an Atlanta prison on May 29, after being notified by Seymour, James Oneal, and Julius Gerber

Julius Gerber (born Israel Getzel Gerber; 1872–1956) was a leading Socialist Party of America party official and politician during the first two decades of the 20th century. Gerber headed the important Socialist Party unit for New York City and ...

.

During the campaign the Socialists had four airplanes drop socialist literature over Toledo, Ohio

Toledo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according ...

. The wife of Charles Edward Russell

Charles Edward Russell (September 25, 1860 in Davenport, Iowa – April 23, 1941 in Washington, D.C.) was an American journalist, opinion columnist, newspaper editor, and political activist. The author of a number of books of biography and socia ...

claimed that the ghost of Susan B. Anthony told her to vote for Debs. Over 60,000 people donated to the Socialist Party's campaign fund. Gerber predicted that Debs would receive three million votes and that five Socialists would be elected to Congress. Debs received 913,693 votes with his largest amount of support coming from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. His vote total was over 50% more than what Allan L. Benson

Allan Louis Benson (November 6, 1871 – August 19, 1940) was an American newspaper editor and author who ran as the Socialist Party of America candidate for President of the United States in 1916 United States presidential election, 1916.

Biogra ...

had received in the 1916 election. Debs later chose to not run for president in the 1924 election and instead supported Robert M. La Follette.

Farmer-Labor Party

Other Candidates

Prohibition Party

Other Candidates

Meeting in Lincoln, Nebraska, there was some question whether the Prohibition Party would field an independent ticket as opposed to endorsing either Harding or Cox, but this was predicated on either making a clear statement that they would not move to weaken the Eighteenth Amendment; neither chose to make any such commitment. The ticket favored by most present was that ofWilliam Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

for President and William "Billy" Sunday for Vice President, and indeed when a motion was made to nominate Bryan by acclamation, of the more than two hundred present it was only opposed by six. Upon hearing of his nomination however Bryan declined the gesture, not wishing to remain singularly focused on the prohibition question or to sever his ties with the Democratic Party entirely. Some had considered Billy Sunday a possible substitute but Sunday was "satisfied" with Republican nominee Warren Harding, while others thought about potentially nominating Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

as their standard-bearer. With the nomination thrown wide open, the Party ultimately opted to nominate keynote speaker and Methodist minister Aaron Watkins of Ohio, over other candidates such as 1916 Convention Chair Robert Patton of Illinois, itinerant minister Daniel Poling of Pennsylvania, and Congressman Charles Randall of California. Historian David Leigh Colvin of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

was nominated for the Vice Presidency.

American Party

James E. Ferguson

James Edward Ferguson Jr. (August 31, 1871 – September 21, 1944), known as Pa Ferguson, was an American Democratic politician and the 26th Governor of Texas, in office from 1915 to 1917. He was indicted and impeached during his second term, ...

, a former Governor of Texas

The governor of Texas heads the state government of Texas. The governor is the leader of the executive and legislative branch of the state government and is the commander in chief of the Texas Military. The current governor is Greg Abbott, who ...

, announced his candidacy on April 21, 1920 in Temple, Texas under the badge of "American Party". Ferguson was opposed to Democrats whom he saw as too controlled by elite academic interests as seen when Woodrow Wilson endorsed rival Thomas H. Ball in the gubernatorial primary, and hoped to help the Republicans carry Texas for the first time (Texas never went Republican during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

). Initially Ferguson and running mate William J. Hough hoped to carry their campaign to other states, but Ferguson was unable to get on the ballot anywhere outside of Texas. Ferguson did manage to gain almost ten percent of the vote in Texas, and won eleven counties in the southeast of the state.Scammon, Richard M. (compiler); ''America at the Polls: A Handbook of Presidential Election Statistics 1920–1964'' pp. 426-430, 456

General election

Return to normalcy

Warren Harding's main campaign slogan was a "return to normalcy", playing upon the weariness of the American public after the social upheaval of the Progressive Era. Additionally, the international responsibilities engendered by the Allied victory inWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

proved deeply unpopular, causing a reaction against Wilson, who had pushed especially hard for the latter.

Ethnic issues

Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

s were powerful in the Democratic party, and groups such as Clan na Gael opposed going to war alongside their enemy Britain, especially after the violent suppression of the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

of 1916. Wilson won them over in 1917 by promising to ask Britain to give Ireland its independence. Wilson had won the presidential election of 1916 with strong support from German-Americans and Irish-Americans, largely because of his slogan "He kept us out of war" and the longstanding American policy of isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entang ...

. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, however, he reneged on his commitments to the Irish-American community, who vehemently denounced him. His dilemma was that Britain was his war ally. Events such as the anti-British Black Tom and Kingsland Explosions in 1916 on American soil (in part the result of wartime Irish and German co-ordination) and the Irish anti-conscription crisis of 1918 were all embarrassing to recall in 1920.

Britain had already passed an Irish Home Rule Act in 1914, suspended for the war's duration. However the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

in Dublin had led to increased support for the more radical Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

who in 1919 formed the First Dáil, effectively declaring Ireland independent, sparking the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. Britain was to pass the Government of Ireland Act Government of Ireland Act may refer to:

* Government of Ireland Act 1914, Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-government within the United Kingdom) for Ireland

* Government of Ireland Act 1920

...

in late 1920, by which Ireland would have 2 home-ruled states within the British empire. This satisfied Wilson. The provisions of these were inadequate to the supporters of the Irish Republic, however, which claimed full sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

. This position was also supported by many Irish Americans. The American Committee for Relief in Ireland

The American Committee for Relief in Ireland was formed through the initiative of Dr. William J. Maloney and others in 1920, with the intention of giving financial assistance to civilians in Ireland who had been injured or suffered severe financia ...

was set up in 1920 to assist victims of the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

of 1919–21. Some Irish-American Senators joined the "irreconcilables

{{for, Irreconcilables during the Philippine–American War , Irreconcilables (Philippines)

The Irreconcilables were bitter opponents of the Treaty of Versailles in the United States in 1919. Specifically, the term refers to about 12 to 18 United ...

" who blocked the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

and United States membership in the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

.

Wilson blamed the Irish Americans and German American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

s for the lack of popular support for his unsuccessful campaign to have the United States join the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, saying, "There is an organized propaganda against the League of Nations and against the treaty proceeding from exactly the same sources that the organized propaganda proceeded from which threatened this country here and there with disloyalty, and I want to say—I cannot say too often—any man who carries a hyphen about with him .e., a hyphenated American">hyphenated_American.html" ;"title=".e., a hyphenated American">.e., a hyphenated Americancarries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready."

Of the $5,500,000 raised by supporters of the Irish Republic in the United States in 1919–20, the Dublin parliament (Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic)">Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...Campaign

Wilson had hoped for a "solemn referendum" on the

Wilson had hoped for a "solemn referendum" on the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, but did not get one. Harding waffled on the League, thereby keeping Idaho Senator William Borah and other Republican "irreconcilables" in line. Cox also hedged. He went to the White House to seek Wilson's blessing and apparently endorsed the League, but—upon discovering its unpopularity among Democrats—revised his position to one that would accept the League only with reservations, particularly on Article Ten, which would require the United States to participate in any war declared by the League (thus taking the same standpoint as Republican Senate leader Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

). As reporter Brand Whitlock observed, the League was an issue important in government circles, but rather less so to the electorate. He also noted that the campaign was not waged on issues: "The people, indeed, do not know what ideas Harding or Cox represents; neither do Harding or Cox. Great is democracy." False rumors circulated that Senator Harding had "Negro blood," but this did not greatly hurt Harding's election campaign.

Governor Cox made a whirlwind campaign that took him to rallies, train station speeches, and formal addresses, reaching audiences totaling perhaps two million, whereas Senator Harding relied upon a "Front Porch Campaign" similar to that of William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

in 1896

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The Jameson Raid comes to an end, as Jameson surrenders to the Boers.

* January 4 – Utah is admitted as the 45th U.S. state.

* January 5 – An Austrian newspaper reports that Wil ...

. It brought thousands of voters to Marion, Ohio

Marion is a city in and the county seat of Marion County, Ohio, Marion County, Ohio, United States. The municipality is located in north-central Ohio, approximately north of Columbus, Ohio, Columbus.

The population was 35,999 at the 2020 United S ...

, where Harding spoke from his home. GOP campaign manager Will Hays spent some $8.1 million, nearly four times the money Cox's campaign spent. Hays used national advertising in a major way (with advice from adman Albert Lasker). The theme was Harding's own slogan "America First". Thus the Republican advertisement in ''Collier's Magazine'' for October 30, 1920, demanded, "Let's be done with wiggle and wobble." The image presented in the ads was nationalistic, using catch phrases like "absolute control of the United States by the United States," "Independence means independence, now as in 1776," "This country will remain American. Its next President will remain in our own country," and "We decided long ago that we objected to foreign government of our people."

On election night, November 2, 1920, commercial radio broadcast coverage of election returns for the first time. Announcers at KDKA-AM

KDKA () is a Class A, clear channel, AM radio station, owned and operated by Audacy, Inc. and licensed to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. Its radio studios are located at the combined Audacy Pittsburgh facility in the Foster Plaza o ...

in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

read telegraph ticker results over the air as they came in. This single station could be heard over most of the Eastern United States by the small percentage of the population that had radio receivers.

Harding's landslide came from all directions except the South. Irish- and German-American voters who had backed Wilson and peace in 1916

Events

Below, the events of the First World War have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 1 – The British Royal Army Medical Corps carries out the first successful blood transfusion, using blood that had been stored and cooled.

* ...

now voted against Wilson and Versailles. "A vote for Harding", said the German-language press, "is a vote against the persecutions suffered by German-Americans during the war". Not one major German-language newspaper supported Governor Cox. Many Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

s, bitterly angry at Wilson's refusal to help Ireland at Versailles, simply abstained from voting in the presidential election. This allowed the Republicans to mobilize the ethnic vote, and Harding swept the big cities.

This was the first election in which women from every state were allowed to vote, following the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in August 1920 (just in time for the general election).

Tennessee's vote for Warren G. Harding marked the first time since the end of

This was the first election in which women from every state were allowed to vote, following the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in August 1920 (just in time for the general election).

Tennessee's vote for Warren G. Harding marked the first time since the end of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

that even one of the eleven states of the former Confederacy had voted for a Republican presidential candidate. Tennessee had last been carried by a Republican when Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

claimed it in 1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

.

Even though Cox lost badly, his running mate Franklin D. Roosevelt became a well-known political figure because of his active and energetic campaign. In 1928, he was elected Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has ...

, and in 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident (1932), Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort ...

he was elected president. He remained in power until his death in 1945 as the longest-serving American president in history.

Results

The total vote for 1920 was roughly 26,750,000, an increase of eight million from

The total vote for 1920 was roughly 26,750,000, an increase of eight million from 1916

Events

Below, the events of the First World War have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 1 – The British Royal Army Medical Corps carries out the first successful blood transfusion, using blood that had been stored and cooled.

* ...

. Harding won in all twelve cities with populations above 500,000. Harding won a net vote total of 1,540,000 from the twelve largest cities which was the highest amount for any Republican and fifth highest for any candidate from 1920 to 1948. The Democratic vote was almost exactly the vote from 1916, but the Republican vote nearly doubled, as did the "other" vote. As pointed out earlier, the great increase in the total number of votes is mainly attributable to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave women the right to vote.

Nearly two-thirds of the counties (1,949) were carried by the Republicans. The Democrats carried only 1,101 counties, a smaller number than Alton Parker had carried in 1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library system.

* ...

and consequently the smallest number during the Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System is the term used in political science and history for the period in American political history from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, except the 1912 split in which Democrats captured the Whit ...

until that point (Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

would carry even fewer in 1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly proving the existence of DNA.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris Bazhanov, J ...

). Not a single county was carried by the Democrats in the Pacific section, where they had carried 76 in 1916. In the Mountain section Cox carried only thirteen counties, seven of them located in New Mexico bordering Texas, whereas Wilson carried all but twenty-one Mountain Section counties in 1916. At least one county was lost in every section in the Union and in every state except South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. Eleven counties in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

recorded a plurality for Ferguson.

Wilson had won the support of Americans of German, Italian, Irish, or Jewish descent in the 1916 election, but Cox lost in all of those demographics and received less support from Jewish voters than Debs. Harding received support from over 90% of black voters.

The distribution of the county vote accurately represents the overwhelming character of the majority vote. Harding received 60.35 percent of the total vote, the largest percentage in the Fourth Party System, exceeding Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's in 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident (1932), Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort ...

. Although the Democratic share was 34.13 percent, in no section did its voting share sink below 24 percent, and in three sections, the Democrats topped the poll. The Democratic Party was obviously still a significant opposition on national terms, even though Cox won only eleven states and had fewer votes in the electoral college than Parker had won in 1904. More than two-thirds of the Cox vote was in states carried by Harding.

The distribution of the vote by counties, and the study of percentages in sections, states, and counties, seem to show that it was Wilson and foreign policies that received the brunt of attack, not the Democratic Party and the domestic proposals of the period 1896–1914.

Source (Popular Vote):

Source (Electoral Vote):

Results by state

Close states

Margin of victory less than 1% (13 electoral votes): # Kentucky, 0.44% (4,017 votes) Margin of victory less than 5% (12 electoral votes): # Tennessee, 3.10% (13,271 votes) Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (10 electoral votes): # Oklahoma, 5.50% (26,778 votes) Tipping point state: # Rhode Island, 31.19% (52,401 votes)Statistics

Counties with Highest Percentage of the Vote (Republican) #McIntosh County, North Dakota

McIntosh County is a county in the U.S. state of North Dakota. As of the 2020 census, the population was 2,530. Its county seat is Ashley. The county is notable for being the county with the highest percentage of German-Americans in the United ...

95.76%

# Leslie County, Kentucky

Leslie County is located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Its county seat is Hyden. Leslie is a prohibition or dry county.

History

Leslie County was founded in 1878. It was named for Preston H. Leslie, Governor of Kentucky (1871-1875).

The Hurr ...

94.22%

# Sevier County, Tennessee

Sevier County ( ) is a county of the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 98,380. Its county seat and largest city is Sevierville. Sevier County comprises the Sevierville, TN Micropolitan Statistical Area, which i ...

93.60%

# Sheridan County, North Dakota

Sheridan County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Dakota. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,265, making it the third-least populous county in North Dakota. Its county seat is McClusky.

History

The Dakota Territory legi ...

92.98%

# Billings County, North Dakota 92.81%

Counties with Highest Percentage of the Vote (Democratic)

# Chester County, South Carolina 100.00%

# Edgefield County, South Carolina

Edgefield County is a county located on the western border of the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census, its population was 25,657. Its county seat and largest municipality is Edgefield. The county was established on March 12, 17 ...

100.00%

# Clarendon County, South Carolina

Clarendon County is a county located below the fall line in the Coastal Plain region of U.S. state of South Carolina. As of 2020 census, its population was 31,144. Its county seat is Manning.

This area was developed for lumber and mills, incl ...

100.00%

# Bamberg County, South Carolina 100.00%

# Hampton County, South Carolina 100.00%

Counties with Highest Percentage of the Vote (American)

# Austin County, Texas 61.72%

# Fort Bend County, Texas 59.35%

# Lavaca County, Texas 57.76%

# Fayette County, Texas 55.12%

# Washington County, Texas 54.04%

See also

*History of the United States (1918–1945)

In the history of the United States, the period from 1918 through 1945 covers the post-World War I era, the Great Depression, and World War II. After World War I, the U.S. rejected the Treaty of Versailles and did not join the League of Nations.

...

* History of the United States Democratic Party

The Democratic Party is one of the two major political parties of the United States political system and the oldest existing political party in that country founded in the 1830s and 1840s.

It is also the oldest voter-based political party in t ...

* History of the United States Republican Party

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP (meaning Grand Old Party), is one of the two major political parties in the United States. It is the second-oldest extant political party in the United States after its main political rival, t ...

* Inauguration of Warren G. Harding

The inauguration of Warren G. Harding as the 29th president of the United States was held on Friday, March 4, 1921, at the East Portico of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. This was the 34th inauguration and marked the commencement o ...

* 1920 United States House of Representatives elections

The 1920 United States House of Representatives elections were held, coinciding with the election of President Warren G. Harding, the first time that women in all states were allowed to vote in federal elections after the passage of the 19th Am ...

* 1920 United States Senate elections

The 1920 United States Senate elections were elections for the United States Senate that coincided with the presidential election of Warren G. Harding. Democrat Woodrow Wilson's unpopularity allowed Republicans to win races across the country, wi ...

Notes

References and further reading

* * * Brake, Robert J. "The porch and the stump: Campaign strategies in the 1920 presidential election." ''Quarterly Journal of Speech'' 55.3 (1969): 256–267. * Burchell, R. A. "Did the Irish and German Voters Desert the Democrats in 1920? A Tentative Statistical Answer" ''Journal of American Studies'' 5#2 (1972) pp. 153-16online

* Daniel, Douglass K. "Ohio Newspapers and the 'Whispering Campaign' of the 1920 Presidential Election." ''Journalism History'' 27.4 (2002): 156-164. * * * * * * * Frederick, Richard G. "The Front Porch Campaign and the Election of Harding." in ''A Companion to Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover'' (2014): 94-111. * * Walters, Ryan S. ''The Jazz Age President: Defending Warren G. Harding'' (2022

excerpt

als

online review

Primary sources

* * Chester, Edward W ''A guide to political platforms'' (1977online

* Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. ''National party platforms, 1840–1964'' (1965

online 1840–1956

* Eugene V. Debs

''A Word to the Workers!''

New York: New York Call, n.d.

920

__NOTOC__

Year 920 ( CMXX) was a leap year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* December 17 – Romanos I has himself crowned co-emperor of the Byzan ...

—Socialist campaign leaflet.

External links

Presidential Election of 1920: A Resource Guide

from the Library of Congress

{{Authority control Presidency of Warren G. Harding Warren G. Harding Calvin Coolidge Franklin D. Roosevelt

Presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...