United States Independence Party on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

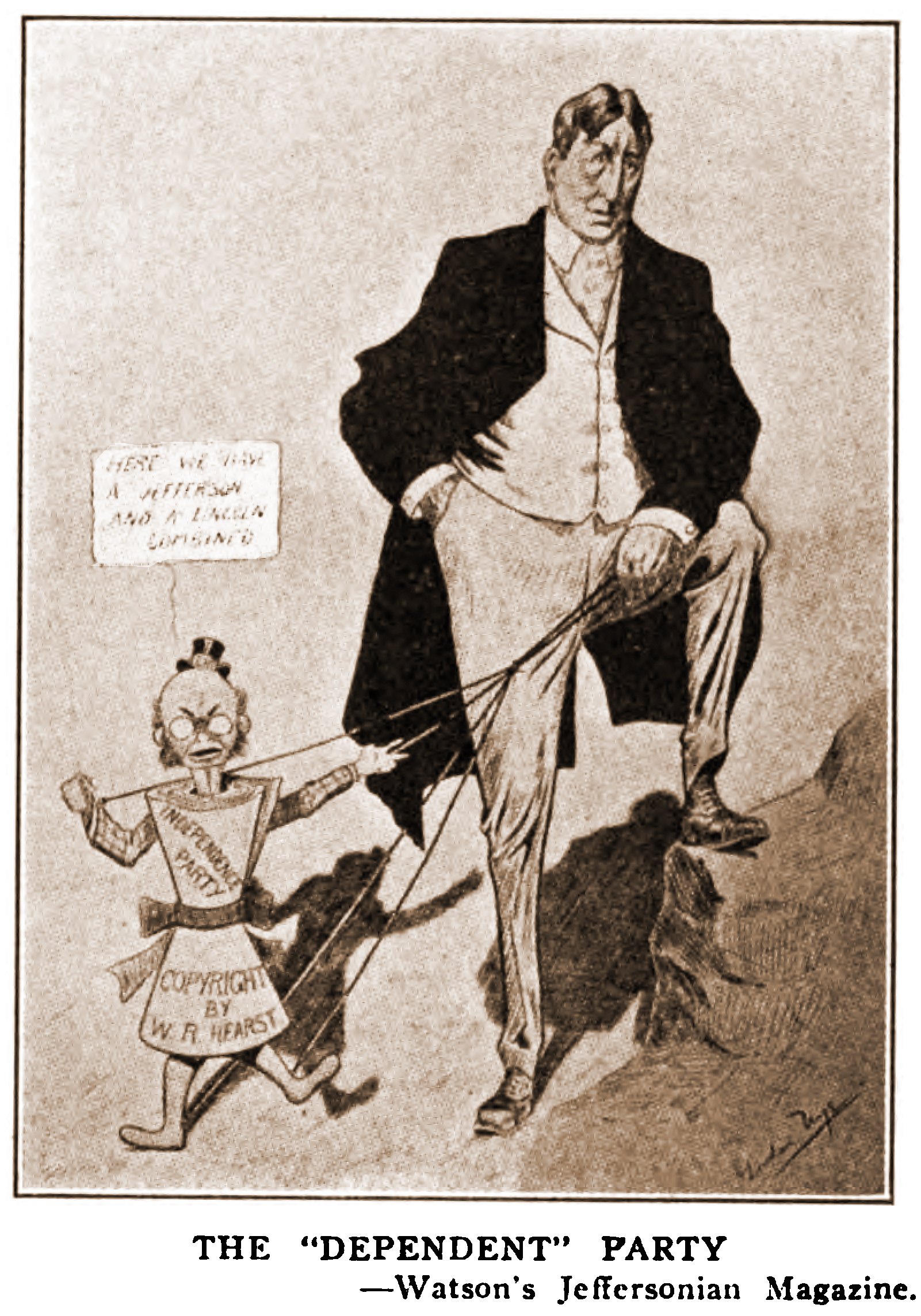

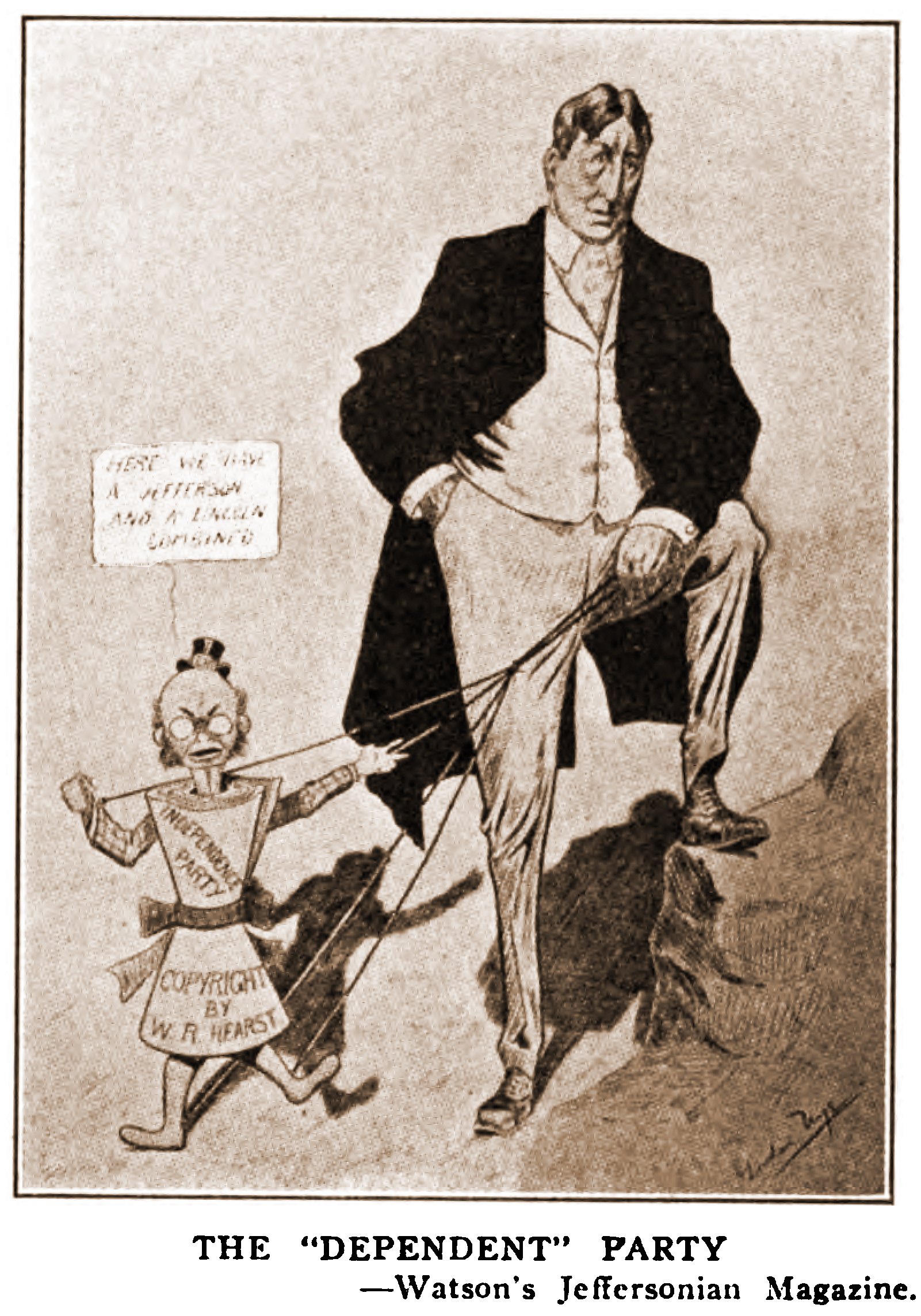

The Independence Party, established as the Independence League, was a short-lived minor American political party sponsored by newspaper publisher and politician

The Independence Party, established as the Independence League, was a short-lived minor American political party sponsored by newspaper publisher and politician

''New York Times,'' July 29, 1908, pp. 1, 3. The Howard nomination was followed by a speech by Rev. Roland D. Sawyer of Massachusetts, who formally placed Hisgen's name into the pool of candidates. This was followed by the nomination of Georgian

"Independence Vacancies Filled by Democrats,"

''New York Times,'' Sept. 30, 1906. {{DEFAULTSORT:Independence Party (United States) Political parties established in 1906 Political parties disestablished in 1914 Defunct political parties in the United States Progressive Era in the United States 1906 establishments in the United States 1914 disestablishments in the United States Political parties in the United States

The Independence Party, established as the Independence League, was a short-lived minor American political party sponsored by newspaper publisher and politician

The Independence Party, established as the Independence League, was a short-lived minor American political party sponsored by newspaper publisher and politician William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

in 1906. The organization was the successor to the Municipal Ownership League

The Municipal Ownership League was an American third party formed in 1904 by controversial newspaper magnate and Congressman William Randolph Hearst for the purpose of contesting elections in New York City.

Hearst, a lifelong Democrat, formed the ...

, under whose colors Hearst had run for Mayor of New York

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

in 1905

As the second year of the massive Russo-Japanese War begins, more than 100,000 die in the largest world battles of that era, and the war chaos leads to the 1905 Russian Revolution against Nicholas II of Russia (Shostakovich's 11th Symphony i ...

.

Following its second-place finish in a race for Governor of Massachusetts

The governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the chief executive officer of the government of Massachusetts. The governor is the head of the state cabinet and the commander-in-chief of the commonwealth's military forces.

Massachusetts ...

in 1907, the party set its sights on the Presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified by a ...

, and held a national convention to nominate a ticket in 1908. The party garnered only 83,000 votes nationally in the 1908 election, however, and immediately dissolved as a national force.

The Independence League of New York continued to nominate candidates for office in New York state

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. stat ...

until the state election of 1914.

Establishment

In 1905, millionaire newspaper publisherWilliam Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

made a high-profile run for Mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

under the banner of the Municipal Ownership League

The Municipal Ownership League was an American third party formed in 1904 by controversial newspaper magnate and Congressman William Randolph Hearst for the purpose of contesting elections in New York City.

Hearst, a lifelong Democrat, formed the ...

. Hearst ran on a reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill#The Yorkshire Associati ...

ticket in opposition to incumbent Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

Democrat George B. McClellan, Jr.

George Brinton McClellan Jr. (November 23, 1865November 30, 1940), was an American statesman, author, historian, and educator. The son of the American Civil War general and presidential candidate George B. McClellan, he was the 93rd Mayor of N ...

and Republican William Mills Ivins, Sr. Hearst narrowly missed election, losing to the Democrat by fewer than 3,500 votes out of nearly 600,000 cast between the three candidates, with the New York Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the State of New York is the trial-level court of general jurisdiction in the New York State Unified Court System. (Its Appellate Division is also the highest intermediate appellate court.) It is vested with unlimited civ ...

ultimately deciding the matter in favor of Tammany Hall on June 30 amidst charges of electoral fraud.

In the wake of the defeat the Municipal Ownership League was replaced by a new political organization with a name less socialistically-oriented name: the Independence League of New York.

In 1906, Hearst again ran for political office, this time going to defeat in the race for Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has ...

on a Democratic–Independence League fusion ticket

Electoral fusion is an arrangement where two or more political parties on a ballot list the same candidate, pooling the votes for that candidate. It is distinct from the process of electoral alliances in that the political parties remain separa ...

. Despite his own loss, other members of the fusion slate were elected, including Lewis S. Chanler as lieutenant governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, John S. Whalen as Secretary of State, Martin H. Glynn

Martin Henry Glynn (September 27, 1871December 14, 1924) was an American politician. He was the 40th Governor of New York from 1913 to 1914, the first Irish American Roman Catholic head of government of what was then the most populated state of ...

as comptroller, Julius Hauser

Julius Hauser (August 7, 1854 Grand Duchy of Baden – March 26, 1920 Sayville, Suffolk County, New York) was an American businessman and politician.

Life

He came to the United States in 1869. He learned the baker's trade, and in 1878 settled in ...

as treasurer, William S. Jackson

William Schuyler Jackson (died November 23, 1932 in Jamaica, Queens, New York City) was an American lawyer and politician.

Biography

Jackson was the son of D. G. Jackson, a lawyer from Tonawanda, NY.

In 1892, he married a daughter of Buffalo s ...

as Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

, and Frederick Skene as state engineer.

Parallel Independence Leagues were active at the same time in several other state×s, including Californial and Massachusetts. In the latter, state party nominee Thomas L. Hisgen

Thomas Louis Hisgen (November 26, 1858 – August 27, 1925) was an American petroleum producer and politician.

He refused to sell his firm to the Standard Oil, Standard Oil Trust and was chosen by the Massachusetts Independence League as its c ...

garnered a substantial number of votes in the 1907 election for governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

, topping the candidate of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

for second place. Prospects seemed bright for a new national political organization to replace the Democrats as the chief opposition party in the United States.

1908 Presidential convention

Buoyed by the promising results for Thomas Hisgen in Massachusetts, the Independence League moved to establish a national presence as the Independence Party ahead of the election of 1908 at a convention held inChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. The gathering was convened on July 27, 1908, in a hall bedecked with patriotic red-white-and-blue bunting and streamers.Darcy Richardson, ''Others: Third Parties During the Populist Period.'' Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2007; pg. 421.

Although Hisgen was regarded as a favorite to win nomination prior to convocation, the nominating convention's decision was not unanimous nor the nomination process without acrimony, requiring three ballots of the assembled delegates to reach an ultimate decision. The first person nominated was former Congressman Milford W. Howard of Fort Payne, Alabama

Fort Payne is a city in and county seat of DeKalb County, in northeastern Alabama, United States. At the 2020 census, the population was 14,877.

European-American settlers gradually developed the settlement around the former fort. It grew rapid ...

, placed into consideration by a long-winded speech which drew catcalls."Hisgen and Graves New Party Ticket: The Independence Convention Makes Its Choice in Early Morning,"''New York Times,'' July 29, 1908, pp. 1, 3. The Howard nomination was followed by a speech by Rev. Roland D. Sawyer of Massachusetts, who formally placed Hisgen's name into the pool of candidates. This was followed by the nomination of Georgian

John Temple Graves

John Temple Graves (November 9, 1856 – August 8, 1925) was an American newspaper editor who is best known for being the vice presidential nominee of the Independence Party in the presidential election of 1908.

Biography

Graves was born in 1 ...

, the editor of a Hearst newspaper.

An attempt by a Kansas delegate to put the name of Democratic Party standard bearer William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

into nomination was met with raucous jeering which briefly prevented the speaker from continuing. With order restored, the speaker continued in his effort to formally nominate Bryan, causing an even more fierce explosion of rage and protest, as a report in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' indicates:

"A scene of riot immediately followed, several delegates attempting to reach the rostrum for the purpose of offering physical violence to the speaker. 'I intend, if I am allowed to finish, to nominate Mr. William J. Bryan,' said Mr. .I.Sheppard.Only after an extended period of tumult was order restored and Sheppard ruled out of order on the grounds of having nominated an individual who was not a member of the Independence Party. Sheppard walked from the rostrum under protection of the convention's two sergeants of arms, but was still swung at with a cane by a New York delegate as he passed down the aisle, with the New Yorker forcibly restrained. An announcement shortly followed that Sheppard had been removed as a member of the National Committee of the Independence Party. With the nominations finally complete, convention voting ensued. The first ballot saw a tally of 396 votes for Hisgen, 213 for Graves, 200 for Howard, 71 for Reuben R. Lyon, and 49 for William Randolph Hearst. A second ballot brought Hisgen to the doorstep of nomination, gathering 590 votes, compared to 189 for Graves and 109 for Howard. Only in the early morning hours of Wednesday, July 29 did Hisgen go over the top, winning the nomination. Graves was elected as Hisgen's Vice-Presidential running mate by the gathering.

"The hall broke into a wild uproar, a dozen delegates vainly struggling in the main aisle in an attempt to reach Mr. Sheppard. Canes and fists were shaken at him furiously, while howls of execration went up from all sides of the hall."

Party platform

The party platform adopted by the Chicago convention declared that corporate corruption, waste in government spending, the exploitative pricing ofmonopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

, a costly tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

, and rule by political machines had exacted a costly economic toll on both investors and working people alike. Both the Republican and Democratic parties, were to blame, the Independence Party declared, and it cast itself as the banner-bearer in the effort "to wrest the conduct of public affairs from the hands of selfish interests, political tricksters, and corrupt bosses" and to make government "an agency for the common good."

The party platform argued against corrupt machine politics

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership con ...

, for the eight-hour work day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 16 ...

, against the use of judicial injunctions to settle labor disputes, for the creation of a Department of Labor

The Ministry of Labour ('' UK''), or Labor ('' US''), also known as the Department of Labour, or Labor, is a government department responsible for setting labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workforce participation, training, a ...

, for improved workplace safety, and for the establishment of a central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

. The organization expressed its disapproval of maintenance of blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

s against striking workers and against the use of prison labor for the production of goods for the marketplace. The organization also favored broad implementation of the initiative and referendum

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the electorate decides on policy initiatives without elected representatives as proxies. This differs from the majority of currently established democracies, which are represen ...

system and in favor of the power of recall of elected officials.

Although mildly social democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soci ...

in content, the platform of the Independence Party took pains to cast the organization as "a conservative force in American politics, devoted to the preservation of American liberty and independence."

Final efforts

The national party collapsed after the 1908 election, in which Hisgen and Graves won less than one percent of the popular vote. Hearst ran again for Mayor of New York in 1909, and for lieutenant governor in 1910, but was defeated both times. The New York Independence League continued to nominate candidates for Governor and Lieutenant Governor of New York until the state election of 1914.Footnotes

Further reading

* Ben H. Procter, ''William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863-1910.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. * Darcy Richardson, ''Others: Third Parties During the Populist Period.'' Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2007."Independence Vacancies Filled by Democrats,"

''New York Times,'' Sept. 30, 1906. {{DEFAULTSORT:Independence Party (United States) Political parties established in 1906 Political parties disestablished in 1914 Defunct political parties in the United States Progressive Era in the United States 1906 establishments in the United States 1914 disestablishments in the United States Political parties in the United States