Ultra Dubstep on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

adopted by British

Army- and Air Force-related intelligence derived from

Army- and Air Force-related intelligence derived from

After encryption systems were "broken", there was a large volume of cryptologic work needed to recover daily key settings and keep up with changes in enemy security procedures, plus the more mundane work of processing, translating, indexing, analyzing and distributing tens of thousands of intercepted messages daily. The more successful the code breakers were, the more labor was required. Some 8,000 women worked at Bletchley Park, about three quarters of the work force. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US Navy sent letters to top women's colleges seeking introductions to their best seniors; the Army soon followed suit. By the end of the war, some 7000 workers in the Army Signal Intelligence service, out of a total 10,500, were female. By contrast, the Germans and Japanese had strong ideological objections to women engaging in war work. The Nazis even created a

After encryption systems were "broken", there was a large volume of cryptologic work needed to recover daily key settings and keep up with changes in enemy security procedures, plus the more mundane work of processing, translating, indexing, analyzing and distributing tens of thousands of intercepted messages daily. The more successful the code breakers were, the more labor was required. Some 8,000 women worked at Bletchley Park, about three quarters of the work force. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US Navy sent letters to top women's colleges seeking introductions to their best seniors; the Army soon followed suit. By the end of the war, some 7000 workers in the Army Signal Intelligence service, out of a total 10,500, were female. By contrast, the Germans and Japanese had strong ideological objections to women engaging in war work. The Nazis even created a

military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) is intelligence-gathering by interception of ''signals'', whether communications between people (communications intelligence—abbreviated to COMINT) or from electronic signals not directly used in communication ( ...

obtained by breaking high-level encrypt

In cryptography, encryption is the process of encoding information. This process converts the original representation of the information, known as plaintext, into an alternative form known as ciphertext. Ideally, only authorized parties can decip ...

ed enemy radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

and teleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initia ...

communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS)

Government Communications Headquarters, commonly known as GCHQ, is an intelligence agency, intelligence and security agency, security organisation responsible for providing signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the G ...

at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes ( Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following ...

. ''Ultra'' eventually became the standard designation among the western Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

for all such intelligence. The name arose because the intelligence obtained was considered more important than that designated by the highest British security classification

Classified information is material that a government body deems to be sensitive information that must be protected. Access is restricted by law or regulation to particular groups of people with the necessary security clearance and need to know, ...

then used (''Most Secret'') and so was regarded as being ''Ultra Secret''. Several other cryptonym

A code name, call sign or cryptonym is a Code word (figure of speech), code word or name used, sometimes clandestinely, to refer to another name, word, project, or person. Code names are often used for military purposes, or in espionage. They may ...

s had been used for such intelligence.

The code name ''Boniface'' was used as a cover name for ''Ultra''. In order to ensure that the successful code-breaking did not become apparent to the Germans, British intelligence created a fictional MI6 master spy, Boniface, who controlled a fictional series of agents throughout Germany. Information obtained through code-breaking was often attributed to the human intelligence

Human intelligence is the intellectual capability of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness. High intelligence is associated with better outcomes in life.

Through intelligence, humans ...

from the Boniface network. The U.S. used the codename ''Magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

'' for its decrypts from Japanese sources, including the "Purple

Purple is any of a variety of colors with hue between red and blue. In the RGB color model used in computer and television screens, purples are produced by mixing red and blue light. In the RYB color model historically used by painters, pu ...

" cipher.

Much of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

cipher traffic was encrypted on the Enigma machine. Used properly, the German military Enigma would have been virtually unbreakable; in practice, shortcomings in operation allowed it to be broken. The term "Ultra" has often been used almost synonymously with " Enigma decrypts". However, Ultra also encompassed decrypts of the German Lorenz SZ 40/42 machines that were used by the German High Command, and the Hagelin machine.

Many observers, at the time and later, regarded Ultra as immensely valuable to the Allies. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

was reported to have told King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of Ind ...

, when presenting to him Stewart Menzies

Major General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, (; 30 January 1890 – 29 May 1968) was Chief of MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), from 1939 to 1952, during and after the Second World War.

Early life, family

Stewart Graham Menzies wa ...

(head of the Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

and the person who controlled distribution of Ultra decrypts to the government): "It is thanks to the secret weapon of General Menzies, put into use on all the fronts, that we won the war!" F. W. Winterbotham

Frederick William Winterbotham (16 April 1897 – 28 January 1990) was a British Royal Air Force officer (latterly a Group Captain) who during World War II supervised the distribution of Ultra intelligence. His book ''The Ultra Secret'' was t ...

quoted the western Supreme Allied Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, at war's end describing Ultra as having been "decisive" to Allied victory. Sir Harry Hinsley, Bletchley Park veteran and official historian of British Intelligence in World War II, made a similar assessment of Ultra, saying that while the Allies would have won the war without it, "the war would have been something like two years longer, perhaps three years longer, possibly four years longer than it was." However, Hinsley and others have emphasized the difficulties of counterfactual history in attempting such conclusions, and some historians, such as Keegan, have said the shortening might have been as little as the three months it took the United States to deploy the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

.

The existence of Ultra was kept secret for many years after the war. Since the Ultra story was widely disseminated by Winterbotham in 1974, historians have altered the historiography of World War II The historiography of World War II is the study of how historians portray the causes, conduct, and outcomes of World War II.

There are different perspectives on the causes of the war; the three most prominent are the Orthodox from the 1950s, Revisi ...

. For example, Andrew Roberts, writing in the 21st century, states, "Because he had the invaluable advantage of being able to read Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

's Enigma communications, General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and t ...

knew how short the Germans were of men, ammunition, food and above all fuel. When he put Rommel's picture up in his caravan he wanted to be seen to be almost reading his opponent's mind. In fact he was reading his mail." Over time, Ultra has become embedded in the public consciousness and Bletchley Park has become a significant visitor attraction. As stated by historian Thomas Haigh, "The British code-breaking effort of the Second World War, formerly secret, is now one of the most celebrated aspects of modern British history, an inspiring story in which a free society mobilized its intellectual resources against a terrible enemy."

Sources of intelligence

Most Ultra intelligence was derived from reading radio messages that had been encrypted with cipher machines, complemented by material from radio communications usingtraffic analysis

Traffic analysis is the process of intercepting and examining messages in order to deduce information from patterns in communication, it can be performed even when the messages are encrypted. In general, the greater the number of messages observed ...

and direction finding

Direction finding (DF), or radio direction finding (RDF), isin accordance with International Telecommunication Union (ITU)defined as radio location that uses the reception of radio waves to determine the direction in which a radio station ...

. In the early phases of the war, particularly during the eight-month Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germ ...

, the Germans could transmit most of their messages using land lines and so had no need to use radio. This meant that those at Bletchley Park had some time to build up experience of collecting and starting to decrypt messages on the various radio network

There are two types of radio network currently in use around the world: the one-to-many (simplex communication) broadcast network commonly used for public information and mass-media entertainment, and the two-way radio ( duplex communication) type ...

s. German Enigma messages were the main source, with those of the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

predominating, as they used radio more and their operators were particularly ill-disciplined.

German

Enigma

"Enigma

Enigma may refer to:

*Riddle, someone or something that is mysterious or puzzling

Biology

*ENIGMA, a class of gene in the LIM domain

Computing and technology

*Enigma (company), a New York-based data-technology startup

* Enigma machine, a family o ...

" refers to a family of electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines. These produced a polyalphabetic substitution cipher and were widely thought to be unbreakable in the 1920s, when a variant of the commercial Model D was first used by the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' () was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

. The German Army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

, Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

, Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

, Nazi party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

, Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

and German diplomats used Enigma machines in several variants. Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' (German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. A ...

(German military intelligence) used a four-rotor machine without a plugboard and Naval Enigma used different key management from that of the army or air force, making its traffic far more difficult to cryptanalyse; each variant required different cryptanalytic treatment. The commercial versions were not as secure and Dilly Knox

Alfred Dillwyn "Dilly" Knox, CMG (23 July 1884 – 27 February 1943) was a British classics scholar and papyrologist at King's College, Cambridge and a codebreaker. As a member of the Room 40 codebreaking unit he helped decrypt the Zimmer ...

of GC&CS is said to have broken one before the war.

German military Enigma was first broken in December 1932 by the Polish Cipher Bureau

The Cipher Bureau, in Polish language, Polish: ''Biuro Szyfrów'' (), was the interwar Polish General Staff's Second Department of Polish General Staff, Second Department's unit charged with SIGINT and both cryptography (the ''use'' of ciphers an ...

, using a combination of brilliant mathematics, the services of a spy in the German office responsible for administering encrypted communications, and good luck. The Poles read Enigma to the outbreak of World War II and beyond, in France. At the turn of 1939, the Germans made the systems ten times more complex, which required a tenfold increase in Polish decryption equipment, which they could not meet. On 25 July 1939, the Polish Cipher Bureau handed reconstructed Enigma machines and their techniques for decrypting ciphers to the French and British. Gordon Welchman

William Gordon Welchman (15 June 1906 – 8 October 1985) was a British mathematician. During World War II, he worked at Britain's secret codebreaking centre, "Station X" at Bletchley Park, where he was one of the most important contributors. A ...

wrote,

At Bletchley Park, some of the key people responsible for success against Enigma included mathematicians Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher, and theoretical biologist. Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical com ...

and Hugh Alexander and, at the British Tabulating Machine Company

__NOTOC__

The British Tabulating Machine Company (BTM) was a firm which manufactured and sold Hollerith unit record equipment and other data-processing equipment. During World War II, BTM constructed some 200 "bombes", machines used at Bletchley P ...

, chief engineer Harold Keen

Harold Hall "Doc" Keen (1894–1973) was a British engineer who produced the engineering design, and oversaw the construction of, the British bombe, a codebreaking machine used in World War II to read German messages sent using the Enigma machi ...

.

After the war, interrogation of German cryptographic personnel led to the conclusion that German cryptanalysts understood that cryptanalytic attacks against Enigma were possible but were thought to require impracticable amounts of effort and investment. The Poles' early start at breaking Enigma and the continuity of their success gave the Allies an advantage when World War II began.

Lorenz cipher

In June 1941, the Germans started to introduce on-linestream cipher

stream cipher is a symmetric key cipher where plaintext digits are combined with a pseudorandom cipher digit stream (keystream). In a stream cipher, each plaintext digit is encrypted one at a time with the corresponding digit of the keystream ...

teleprinter

A teleprinter (teletypewriter, teletype or TTY) is an electromechanical device that can be used to send and receive typed messages through various communications channels, in both point-to-point and point-to-multipoint configurations. Initia ...

systems for strategic point-to-point radio links, to which the British gave the code-name Fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

. Several systems were used, principally the Lorenz SZ 40/42

The Lorenz SZ40, SZ42a and SZ42b were German rotor stream cipher machines used by the German Army during World War II. They were developed by C. Lorenz AG in Berlin. The model name ''SZ'' was derived from ''Schlüssel-Zusatz'', meaning ''ciph ...

(Tunny) and Geheimfernschreiber

The Siemens & Halske T52, also known as the Geheimschreiber ("secret teleprinter"), or ''Schlüsselfernschreibmaschine'' (SFM), was a World War II German cipher machine and teleprinter produced by the electrical engineering firm Siemens & Halske. ...

(Sturgeon

Sturgeon is the common name for the 27 species of fish belonging to the family Acipenseridae. The earliest sturgeon fossils date to the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretace ...

). These cipher systems were cryptanalysed, particularly Tunny, which the British thoroughly penetrated. It was eventually attacked using Colossus

Colossus, Colossos, or the plural Colossi or Colossuses, may refer to:

Statues

* Any exceptionally large statue

** List of tallest statues

** :Colossal statues

* ''Colossus of Barletta'', a bronze statue of an unidentified Roman emperor

* ''Col ...

machines, which were the first digital programme-controlled electronic computers. In many respects the Tunny work was more difficult than for the Enigma, since the British codebreakers had no knowledge of the machine producing it and no head-start such as that the Poles had given them against Enigma.

Although the volume of intelligence derived from this system was much smaller than that from Enigma, its importance was often far higher because it produced primarily high-level, strategic intelligence that was sent between Wehrmacht High Command (OKW). The eventual bulk decryption of Lorenz-enciphered messages contributed significantly, and perhaps decisively, to the defeat of Nazi Germany. Nevertheless, the Tunny story has become much less well known among the public than the Enigma one. At Bletchley Park, some of the key people responsible for success in the Tunny effort included mathematicians W. T. "Bill" Tutte and Max Newman

Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, FRS, (7 February 1897 – 22 February 1984), generally known as Max Newman, was a British mathematician and codebreaker. His work in World War II led to the construction of Colossus, the world's first operatio ...

and electrical engineer Tommy Flowers

Thomas Harold Flowers MBE (22 December 1905 – 28 October 1998) was an English engineer with the British General Post Office. During World War II, Flowers designed and built Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic computer, to help ...

.

Italian

In June 1940, the Italians were using book codes for most of their military messages, except for the Italian Navy, which in early 1941 had started using a version of the Hagelin rotor-based cipher machine C-38. This was broken from June 1941 onwards by the Italian subsection of GC&CS atBletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes ( Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following ...

.

Japanese

In thePacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

theatre, a Japanese cipher machine, called "Purple

Purple is any of a variety of colors with hue between red and blue. In the RGB color model used in computer and television screens, purples are produced by mixing red and blue light. In the RYB color model historically used by painters, pu ...

" by the Americans, was used for highest-level Japanese diplomatic traffic. It produced a polyalphabetic substitution cipher, but unlike Enigma, was not a rotor machine, being built around electrical stepping switch

In electrical control engineering, a stepping switch or stepping relay, also known as a uniselector, is an electromechanical device that switches an input signal path to one of several possible output paths, directed by a train of electrical pulse ...

es. It was broken by the US Army Signal Intelligence Service

The Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) was the United States Army codebreaking division through World War II. It was founded in 1930 to compile codes for the Army. It was renamed the Signal Security Agency in 1943, and in September 1945, became th ...

and disseminated as ''Magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

''. Detailed reports by the Japanese ambassador to Germany were encrypted on the Purple machine. His reports included reviews of German assessments of the military situation, reviews of strategy and intentions, reports on direct inspections by the ambassador (in one case, of Normandy beach defences), and reports of long interviews with Hitler. The Japanese are said to have obtained an Enigma machine in 1937, although it is debated whether they were given it by the Germans or bought a commercial version, which, apart from the plugboard and internal wiring, was the German ''Heer/Luftwaffe'' machine. Having developed a similar machine, the Japanese did not use the Enigma machine for their most secret communications.

The chief fleet communications code system used by the Imperial Japanese Navy was called JN-25

The vulnerability of Japanese naval codes and ciphers was crucial to the conduct of World War II, and had an important influence on foreign relations between Japan and the west in the years leading up to the war as well. Every Japanese code was e ...

by the Americans, and by early 1942 the US Navy had made considerable progress in decrypting Japanese naval messages. The US Army also made progress on the Japanese Army's codes in 1943, including codes used by supply ships, resulting in heavy losses to their shipping.

Distribution

Army- and Air Force-related intelligence derived from

Army- and Air Force-related intelligence derived from signals intelligence

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) is intelligence-gathering by interception of ''signals'', whether communications between people (communications intelligence—abbreviated to COMINT) or from electronic signals not directly used in communication ( ...

(SIGINT) sources—mainly Enigma decrypts in Hut 6

Hut 6 was a wartime section of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, Britain, tasked with the solution of German Army and Air Force Enigma machine cyphers. Hut 8, by contrast, attacked Naval Enigma. ...

—was compiled in summaries at GC&CS (Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes ( Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following ...

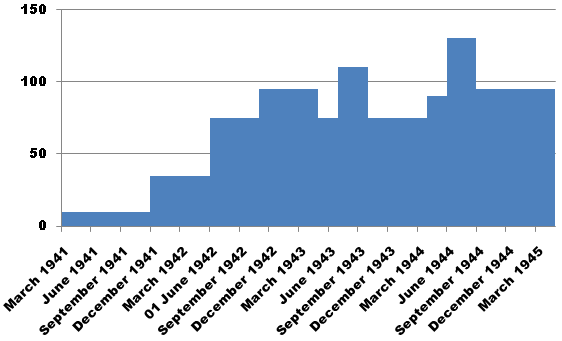

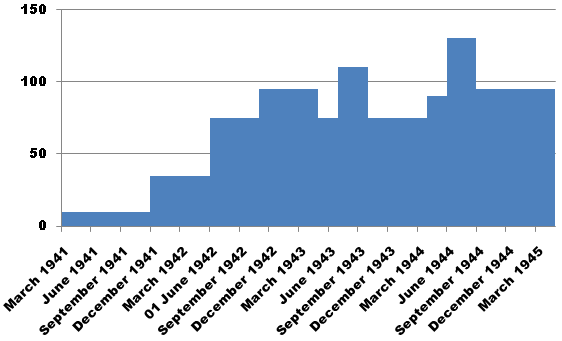

) Hut 3 and distributed initially under the codeword "BONIFACE", implying that it was acquired from a well placed agent in Berlin. The volume of the intelligence reports going out to commanders in the field built up gradually.

Naval Enigma decrypted in Hut 8

Hut 8 was a section in the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park (the British World War II codebreaking station, located in Buckinghamshire) tasked with solving German naval (Kriegsmarine) Enigma messages. The section was l ...

was forwarded from Hut 4 to the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

's Operational Intelligence Centre (OIC), which distributed it initially under the codeword "HYDRO".

The codeword "ULTRA" was adopted in June 1941. This codeword was reportedly suggested by Commander Geoffrey Colpoys, RN, who served in the Royal Navy's OIC.

Army and Air Force

The distribution of Ultra information to Allied commanders and units in the field involved considerable risk of discovery by the Germans, and great care was taken to control both the information and knowledge of how it was obtained. Liaison officers were appointed for each field command to manage and control dissemination. Dissemination of Ultra intelligence to field commanders was carried out byMI6

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

, which operated Special Liaison Units (SLU) attached to major army and air force commands. The activity was organized and supervised on behalf of MI6 by Group Captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

F. W. Winterbotham

Frederick William Winterbotham (16 April 1897 – 28 January 1990) was a British Royal Air Force officer (latterly a Group Captain) who during World War II supervised the distribution of Ultra intelligence. His book ''The Ultra Secret'' was t ...

. Each SLU included intelligence, communications, and cryptographic elements. It was headed by a British Army or RAF officer, usually a major, known as "Special Liaison Officer". The main function of the liaison officer or his deputy was to pass Ultra intelligence bulletins to the commander of the command he was attached to, or to other indoctrinated staff officers. In order to safeguard Ultra, special precautions were taken. The standard procedure was for the liaison officer to present the intelligence summary to the recipient, stay with him while he studied it, then take it back and destroy it.

By the end of the war, there were about 40 SLUs serving commands around the world. Fixed SLUs existed at the Admiralty, the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

, the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

, RAF Fighter Command

RAF Fighter Command was one of the commands of the Royal Air Force. It was formed in 1936 to allow more specialised control of fighter aircraft. It served throughout the Second World War. It earned near-immortal fame during the Battle of Britai ...

, the US Strategic Air Forces in Europe (Wycombe Abbey) and other fixed headquarters in the UK. An SLU was operating at the War HQ in Valletta, Malta. These units had permanent teleprinter links to Bletchley Park.

Mobile SLUs were attached to field army and air force headquarters and depended on radio communications to receive intelligence summaries. The first mobile SLUs appeared during the French campaign of 1940. An SLU supported the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) headed by General Lord Gort. The first liaison officers were Robert Gore-Browne and Humphrey Plowden. A second SLU of the 1940 period was attached to the RAF Advanced Air Striking Force

The RAF Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) comprised the light bombers of No. 1 Group RAF, 1 Group RAF Bomber Command, which took part in the Battle of France during the Second World War. Before hostilities began, it had been agreed between the ...

at Meaux

Meaux () is a commune on the river Marne in the Seine-et-Marne department in the Île-de-France region in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is east-northeast of the centre of Paris.

Meaux is, with Provins, Torcy and Fontainebleau, ...

commanded by Air Vice-Marshal P H Lyon Playfair. This SLU was commanded by Squadron Leader F.W. "Tubby" Long.

Intelligence agencies

In 1940, special arrangements were made within the British intelligence services for handling BONIFACE and later Ultra intelligence. The Security Service started "Special Research Unit B1(b)" under Herbert Hart. In the SIS this intelligence was handled by "Section V" based atSt Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

.

Radio and cryptography

The communications system was founded by Brigadier SirRichard Gambier-Parry

Brigadier Sir Richard Gambier-Parry, (20 January 1894 – 19 June 1965) was a British military officer who served in both the army and the air force during World War I. He remained in military service post-war, but then entered into civilian lif ...

, who from 1938 to 1946 was head of MI6 Section VIII, based at Whaddon Hall in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

, UK. Ultra summaries from Bletchley Park were sent over landline to the Section VIII radio transmitter at Windy Ridge. From there they were transmitted to the destination SLUs.

The communications element of each SLU was called a "Special Communications Unit" or SCU. Radio transmitters were constructed at Whaddon Hall workshops, while receivers were the National HRO

The original National HRO was a 9-tube HF (shortwave) general coverage communications receiver manufactured by the National Radio Company of Malden, Massachusetts, United States.

History

James Millen (amateur radio call sign W1HRX) in Massachuse ...

, made in the USA. The SCUs were highly mobile and the first such units used civilian Packard

Packard or Packard Motor Car Company was an American luxury automobile company located in Detroit, Michigan. The first Packard automobiles were produced in 1899, and the last Packards were built in South Bend, Indiana in 1958.

One of the "Thr ...

cars. The following SCUs are listed: SCU1 (Whaddon Hall), SCU2 (France before 1940, India), SCU3 (RSS Hanslope Park), SCU5, SCU6 (possibly Algiers and Italy), SCU7 (training unit in the UK), SCU8 (Europe after D-day), SCU9 (Europe after D-day), SCU11 (Palestine and India), SCU12 (India), SCU13 and SCU14.

The cryptographic element of each SLU was supplied by the RAF and was based on the TYPEX cryptographic machine and one-time pad

In cryptography, the one-time pad (OTP) is an encryption technique that cannot be cracked, but requires the use of a single-use pre-shared key that is not smaller than the message being sent. In this technique, a plaintext is paired with a ran ...

systems.

RN Ultra messages from the OIC to ships at sea were necessarily transmitted over normal naval radio circuits and were protected by one-time pad encryption.

Lucy

An intriguing question concerns the alleged use of Ultra information by the "Lucy" spy ring, headquartered inSwitzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

and apparently operated by one man, Rudolf Roessler

Rudolf Roessler (German: ''Rößler''; 22 November 1897 – 11 December 1958) was a Protestant Germany, German and dedicated anti-Nazi. During the interwar period, Roessler was a lively cultural journalist, with a focus on theatre. In 1933 while ...

. This was an extremely well informed, responsive ring that was able to get information "directly from German General Staff Headquarters" – often on specific request. It has been alleged that "Lucy" was in major part a conduit for the British to feed Ultra intelligence to the Soviets in a way that made it appear to have come from highly placed espionage rather than from cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic sec ...

of German radio traffic. The Soviets, however, through an agent at Bletchley, John Cairncross

John Cairncross (25 July 1913 – 8 October 1995) was a British civil servant who became an intelligence officer and spy during the Second World War. As a Soviet double agent, he passed to the Soviet Union the raw Tunny decryptions that influ ...

, knew that Britain had broken Enigma. The "Lucy" ring was initially treated with suspicion by the Soviets. The information it provided was accurate and timely, however, and Soviet agents in Switzerland (including their chief, Alexander Radó) eventually learned to take it seriously. However, the theory that the Lucy ring was a cover for Britain to pass Enigma intelligence to the Soviets has not gained traction. Among others who have rejected the theory, Harry Hinsley

Sir Francis Harry Hinsley, (26 November 1918 – 16 February 1998) was an English historian and cryptanalyst. He worked at Bletchley Park during the Second World War and wrote widely on the history of international relations and British Int ...

, the official historian for the British Secret Services in World War II, stated that "there is no truth in the much-publicized claim that the British authorities made use of the ‘Lucy’ ring..to forward intelligence to Moscow".

Use of intelligence

Most deciphered messages, often about relative trivia, were insufficient as intelligence reports for military strategists or field commanders. The organisation, interpretation and distribution of decrypted Enigma message traffic and other sources into usable intelligence was a subtle task. At Bletchley Park, extensive indices were kept of the information in the messages decrypted. For each message the traffic analysis recorded the radio frequency, the date and time of intercept, and the preamble—which contained the network-identifying discriminant, the time of origin of the message, the callsign of the originating and receiving stations, and theindicator

Indicator may refer to:

Biology

* Environmental indicator of environmental health (pressures, conditions and responses)

* Ecological indicator of ecosystem health (ecological processes)

* Health indicator, which is used to describe the health o ...

setting. This allowed cross referencing of a new message with a previous one. The indices included message preambles, every person, every ship, every unit, every weapon, every technical term and of repeated phrases such as forms of address and other German military jargon that might be usable as '' cribs''.

The first decryption of a wartime Enigma message, albeit one that had been transmitted three months earlier, was achieved by the Poles at PC Bruno

''PC Bruno'' was a Polish–French–Spanish signals–intelligence station near Paris during World War II, from October 1939 until June 1940. Its function was decryption of cipher messages, most notably German messages enciphered on the Enigma ...

on 17 January 1940. Little had been achieved by the start of the Allied campaign in Norway in April. At the start of the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

on 10 May 1940, the Germans made a very significant change in the indicator procedures for Enigma messages. However, the Bletchley Park cryptanalysts had anticipated this, and were able — jointly with PC Bruno — to resume breaking messages from 22 May, although often with some delay. The intelligence that these messages yielded was of little operational use in the fast-moving situation of the German advance.

Decryption of Enigma traffic built up gradually during 1940, with the first two prototype bombes being delivered in March and August. The traffic was almost entirely limited to ''Luftwaffe'' messages. By the peak of the Battle of the Mediterranean

The Battle of the Mediterranean was the name given to the naval campaign fought in the Mediterranean Sea during World War II, from 10 June 1940 to 2 May 1945.

For the most part, the campaign was fought between the Italian Royal Navy (''Regia ...

in 1941, however, Bletchley Park was deciphering daily 2,000 Italian Hagelin messages. By the second half of 1941 30,000 Enigma messages a month were being deciphered, rising to 90,000 a month of Enigma and Fish decrypts combined later in the war.

Some of the contributions that Ultra intelligence made to the Allied successes are given below.

* In April 1940, Ultra information provided a detailed picture of the disposition of the German forces, and then their movement orders for the attack on the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

prior to the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

in May.

* An Ultra decrypt of June 1940 read ''KNICKEBEIN

The Battle of the Beams was a period early in the Second World War when bombers of the German Air Force (''Luftwaffe'') used a number of increasingly accurate systems of radio navigation for night bombing in the United Kingdom. British scientific ...

KLEVE IST AUF PUNKT 53 GRAD 24 MINUTEN NORD UND EIN GRAD WEST EINGERICHTET'' ("The Cleves ''Knickebein'' is directed at position 53 degrees 24 minutes north and 1 degree west"). This was the definitive piece of evidence that Dr R V Jones of scientific intelligence in the Air Ministry needed to show that the Germans were developing a radio guidance system for their bombers. Ultra intelligence then continued to play a vital role in the so-called Battle of the Beams.

* During the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, Commander-in-Chief of RAF Fighter Command

RAF Fighter Command was one of the commands of the Royal Air Force. It was formed in 1936 to allow more specialised control of fighter aircraft. It served throughout the Second World War. It earned near-immortal fame during the Battle of Britai ...

, had a teleprinter link from Bletchley Park to his headquarters at RAF Bentley Priory

RAF Bentley Priory was a non-flying Royal Air Force station near Stanmore in the London Borough of Harrow. It was the headquarters of Fighter Command in the Battle of Britain and throughout the Second World War. During the war, two enemy bomb ...

, for Ultra reports. Ultra intelligence kept him informed of German strategy, and of the strength and location of various ''Luftwaffe'' units, and often provided advance warning of bombing raids (but not of their specific targets). These contributed to the British success. Dowding was bitterly and sometimes unfairly criticized by others who did not see Ultra, but he did not disclose his source.

* Decryption of traffic from ''Luftwaffe'' radio networks provided a great deal of indirect intelligence about the Germans' planned Operation Sea Lion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

to invade England in 1940.

* On 17 September 1940 an Ultra message reported that equipment at German airfields in Belgium for loading planes with paratroops and their gear, was to be dismantled. This was taken as a clear signal that Sea Lion had been cancelled.

* Ultra revealed that a major German air raid was planned for the night of 14 November 1940, and indicated three possible targets, including London and Coventry. However, the specific target was not determined until late on the afternoon of 14 November, by detection of the German radio guidance signals. Unfortunately, countermeasures failed to prevent the devastating Coventry Blitz. F. W. Winterbotham claimed that Churchill had advance warning, but intentionally did nothing about the raid, to safeguard Ultra. This claim has been comprehensively refuted by R V Jones, Sir David Hunt, Ralph Bennett and Peter Calvocoressi. Ultra warned of a raid but did not reveal the target. Churchill, who had been ''en route'' to Ditchley Park

Ditchley Park is a country house near Charlbury in Oxfordshire, England. The estate was once the site of a Roman villa. Later it became a royal hunting ground, and then the property of Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley. The 2nd Earl of Lichfield buil ...

, was told that London might be bombed and returned to 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London, also known colloquially in the United Kingdom as Number 10, is the official residence and executive office of the first lord of the treasury, usually, by convention, the prime minister of the United Kingdom. Along wi ...

so that he could observe the raid from the Air Ministry roof.

* Ultra intelligence considerably aided the British Army's Operation Compass

Operation Compass (also it, Battaglia della Marmarica) was the first large British military operation of the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) during the Second World War. British, Empire and Commonwealth forces attacked Italian forces of ...

victory over the much larger Italian army in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

in December 1940 – February 1941.

* Ultra intelligence greatly aided the Royal Navy's victory over the Italian navy in the Battle of Cape Matapan in March 1941.

* Although the Allies lost the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (german: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta, el, Μάχη της Κρήτης), codenamed Operation Mercury (german: Unternehmen Merkur), was a major Axis airborne and amphibious operation during World War II to capture the island ...

in May 1941, the Ultra intelligence that a parachute landing was planned, and the exact day of the invasion, meant that heavy losses were inflicted on the Germans and that fewer British troops were captured.

* Ultra intelligence fully revealed the preparations for Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, the German invasion of the USSR. Although this information was passed to the Soviet government, Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

refused to believe it. The information did, however, help British planning, knowing that substantial German forces were to be deployed to the East.

* Ultra intelligence made a very significant contribution in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

. Winston Churchill wrote "The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril." The decryption of Enigma signals to the U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s was much more difficult than those of the ''Luftwaffe''. It was not until June 1941 that Bletchley Park was able to read a significant amount of this traffic currently. Transatlantic convoys were then diverted away from the U-boat "wolfpacks", and the U-boat supply vessels were sunk. On 1 February 1942, Enigma U-boat traffic became unreadable because of the introduction of a different 4-rotor Enigma machine. This situation persisted until December 1942, although other German naval Enigma messages were still being deciphered, such as those of the U-boat training command at Kiel. From December 1942 to the end of the war, Ultra allowed Allied convoys to evade U-boat patrol lines, and guided Allied anti-submarine forces to the location of U-boats at sea.

* In the Western Desert Campaign, Ultra intelligence helped Wavell and Auchinleck

Auchinleck ( ; sco, Affleck ;

gd, Achadh nan Leac

to prevent Rommel's forces from reaching Cairo in the autumn of 1941.

* Ultra intelligence from Hagelin decrypts, and from ''Luftwaffe'' and German naval Enigma decrypts, helped sink about half of the ships supplying the Axis forces in North Africa.

* Ultra intelligence from ''Abwehr'' transmissions confirmed that Britain's Security Service (gd, Achadh nan Leac

MI5

The Security Service, also known as MI5 ( Military Intelligence, Section 5), is the United Kingdom's domestic counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), Go ...

) had captured all of the German agents in Britain, and that the ''Abwehr'' still believed in the many double agents

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organi ...

which MI5 controlled under the Double Cross System

The Double-Cross System or XX System was a World War II counter-espionage and deception operation of the British Security Service (a civilian organisation usually referred to by its cover title MI5). Nazi agents in Britain – real and false – w ...

. This enabled major deception operations.

* Deciphered JN-25 messages allowed the U.S. to turn back a Japanese offensive in the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea, from 4 to 8 May 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and naval and air forces of the United States and Australia. Taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, the batt ...

in April 1942 and set up the decisive American victory at the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under Adm ...

in June 1942.

* Ultra contributed very significantly to the monitoring of German developments at Peenemünde

Peenemünde (, en, "Peene iverMouth") is a municipality on the Baltic Sea island of Usedom in the Vorpommern-Greifswald district in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. It is part of the ''Amt'' (collective municipality) of Usedom-Nord. The communi ...

and the collection of V-1 and V-2 Intelligence

Military intelligence on the V-1 flying bomb, V-1 and V-2 rocket, V-2 weapons developed by the Germans for attacks on the United Kingdom during the Second World War was important to countering them. Intelligence came from a number of sources and ...

from 1942 onwards.

* Ultra contributed to Montgomery's victory at the Battle of Alam el Halfa by providing warning of Rommel's planned attack.

* Ultra also contributed to the success of Montgomery's offensive in the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian Railway station, railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa ...

, by providing him (before the battle) with a complete picture of Axis forces, and (during the battle) with Rommel's own action reports to Germany.

* Ultra provided evidence that the Allied landings in French North Africa (Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

) were not anticipated.

* A JN-25 decrypt of 14 April 1943 provided details of Admiral Yamamoto's forthcoming visit to Balalae Island, and on 18 April, a year to the day following the Doolittle Raid

The Doolittle Raid, also known as the Tokyo Raid, was an air raid on 18 April 1942 by the United States on the Japanese capital Tokyo and other places on Honshu during World War II. It was the first American air operation to strike the Japan ...

, his aircraft was shot down, killing this man who was regarded as irreplaceable.

* Ship position reports in the Japanese Army’s "2468" water transport code, decrypted by the SIS starting in July 1943, helped U.S. submarines and aircraft sink two-thirds of the Japanese merchant marine.

* The part played by Ultra intelligence in the preparation for the Allied invasion of Sicily was of unprecedented importance. It provided information as to where the enemy's forces were strongest and that the elaborate strategic deceptions had convinced Hitler and the German high command.

* The success of the Battle of North Cape

The Battle of the North Cape was a Second World War naval battle that occurred on 26 December 1943, as part of the Arctic campaign. The , on an operation to attack Arctic Convoys of war materiel from the Western Allies to the Soviet Union, was ...

, in which HMS ''Duke of York'' sank the German battleship ''Scharnhorst'', was entirely built on prompt deciphering of German naval signals.

* US Army Lieutenant Arthur J Levenson who worked on both Enigma and Tunny at Bletchley Park, said in a 1980 interview of intelligence from Tunny

* Both Enigma and Tunny decrypts showed Germany had been taken in by Operation Bodyguard

Operation Bodyguard was the code name for a World War II deception strategy employed by the Allied states before the 1944 invasion of northwest Europe. Bodyguard set out an overall stratagem for misleading the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht as to ...

, the deception operation to protect Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

. They revealed the Germans did not anticipate the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

and even after D-Day still believed Normandy was only a feint, with the main invasion to be in the Pas de Calais.

* Information that there was German ''Panzergrenadier

''Panzergrenadier'' (), abbreviated as ''PzG'' (WWII) or ''PzGren'' (modern), meaning '' "Armour"-ed fighting vehicle "Grenadier"'', is a German term for mechanized infantry units of armoured forces who specialize in fighting from and in conjunc ...

'' division in the planned dropping zone for the US 101st Airborne Division

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) ("Screaming Eagles") is a light infantry division of the United States Army that specializes in air assault operations. It can plan, coordinate, and execute multiple battalion-size air assault operati ...

in Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

led to a change of location.

* It assisted greatly in Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was the codename for an Offensive (military), offensive launched by the United States First United States Army, First Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Invasion of Norman ...

.

* It warned of the major German counterattack at Mortain, and allowed the Allies to surround the forces at Falaise

Falaise may refer to:

Places

* Falaise, Ardennes, France

* Falaise, Calvados, France

** The Falaise pocket was the site of a battle in the Second World War

* La Falaise, in the Yvelines ''département'', France

* The Falaise escarpment in Quebec ...

.

* During the Allied advance to Germany, Ultra often provided detailed tactical information, and showed how Hitler ignored the advice of his generals and insisted on German troops fighting in place "to the last man".

* Arthur "Bomber" Harris

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Travers Harris, 1st Baronet, (13 April 1892 – 5 April 1984), commonly known as "Bomber" Harris by the press and often within the RAF as "Butch" Harris, was Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C) ...

, officer commanding RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

, was not cleared for Ultra. After D-Day, with the resumption of the strategic bomber campaign over Germany, Harris remained wedded to area bombardment. Historian Frederick Taylor argues that, as Harris was not cleared for access to Ultra, he was given some information gleaned from Enigma but not the information's source. This affected his attitude about post-D-Day directives to target oil installations, since he did not know that senior Allied commanders were using high-level German sources to assess just how much this was hurting the German war effort; thus Harris tended to see the directives to bomb specific oil and munitions targets as a "panacea" (his word) and a distraction from the real task of making the rubble bounce.

Safeguarding of sources

The Allies were seriously concerned with the prospect of the Axis command finding out that they had broken into the Enigma traffic. The British were more disciplined about such measures than the Americans, and this difference was a source of friction between them. To disguise the source of the intelligence for the Allied attacks on Axis supply ships bound for North Africa, "spotter" submarines and aircraft were sent to search for Axis ships. These searchers or their radio transmissions were observed by the Axis forces, who concluded their ships were being found by conventional reconnaissance. They suspected that there were some 400 Allied submarines in the Mediterranean and a huge fleet of reconnaissance aircraft onMalta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

. In fact, there were only 25 submarines and at times as few as three aircraft.

This procedure also helped conceal the intelligence source from Allied personnel, who might give away the secret by careless talk, or under interrogation if captured. Along with the search mission that would find the Axis ships, two or three additional search missions would be sent out to other areas, so that crews would not begin to wonder why a single mission found the Axis ships every time.

Other deceptive means were used. On one occasion, a convoy of five ships sailed from Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

to North Africa with essential supplies at a critical moment in the North African fighting. There was no time to have the ships properly spotted beforehand. The decision to attack solely on Ultra intelligence went directly to Churchill. The ships were all sunk by an attack "out of the blue", arousing German suspicions of a security breach. To distract the Germans from the idea of a signals breach (such as Ultra), the Allies sent a radio message to a fictitious spy in Naples, congratulating him for this success. According to some sources the Germans decrypted this message and believed it.

In the Battle of the Atlantic, the precautions were taken to the extreme. In most cases where the Allies knew from intercepts the location of a U-boat in mid-Atlantic, the U-boat was not attacked immediately, until a "cover story" could be arranged. For example, a search plane might be "fortunate enough" to sight the U-boat, thus explaining the Allied attack.

Some Germans had suspicions that all was not right with Enigma. Admiral Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

received reports of "impossible" encounters between U-boats and enemy vessels which made him suspect some compromise of his communications. In one instance, three U-boats met at a tiny island in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

, and a British destroyer promptly showed up. The U-boats escaped and reported what had happened. Dönitz immediately asked for a review of Enigma's security. The analysis suggested that the signals problem, if there was one, was not due to the Enigma itself. Dönitz had the settings book changed anyway, blacking out Bletchley Park for a period. However, the evidence was never enough to truly convince him that Naval Enigma was being read by the Allies. The more so, since ''B-Dienst

The ''B-Dienst'' (german: Beobachtungsdienst, observation service), also called x''B-Dienst'', X-''B-Dienst'' and χ''B-Dienst'', was a Department of the German Naval Intelligence Service (german: Marinenachrichtendienst, MND III) of the OKM, t ...

'', his own codebreaking group, had partially broken Royal Navy traffic (including its convoy codes early in the war), and supplied enough information to support the idea that the Allies were unable to read Naval Enigma.

By 1945, most German Enigma traffic could be decrypted within a day or two, yet the Germans remained confident of its security.

Role of women in Allied codebreaking

After encryption systems were "broken", there was a large volume of cryptologic work needed to recover daily key settings and keep up with changes in enemy security procedures, plus the more mundane work of processing, translating, indexing, analyzing and distributing tens of thousands of intercepted messages daily. The more successful the code breakers were, the more labor was required. Some 8,000 women worked at Bletchley Park, about three quarters of the work force. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US Navy sent letters to top women's colleges seeking introductions to their best seniors; the Army soon followed suit. By the end of the war, some 7000 workers in the Army Signal Intelligence service, out of a total 10,500, were female. By contrast, the Germans and Japanese had strong ideological objections to women engaging in war work. The Nazis even created a

After encryption systems were "broken", there was a large volume of cryptologic work needed to recover daily key settings and keep up with changes in enemy security procedures, plus the more mundane work of processing, translating, indexing, analyzing and distributing tens of thousands of intercepted messages daily. The more successful the code breakers were, the more labor was required. Some 8,000 women worked at Bletchley Park, about three quarters of the work force. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the US Navy sent letters to top women's colleges seeking introductions to their best seniors; the Army soon followed suit. By the end of the war, some 7000 workers in the Army Signal Intelligence service, out of a total 10,500, were female. By contrast, the Germans and Japanese had strong ideological objections to women engaging in war work. The Nazis even created a Cross of Honour of the German Mother

The Cross of Honour of the German Mother (), referred to colloquially as the ''Mutterehrenkreuz'' (Mother's Cross of Honour) or simply ''Mutterkreuz'' (Mother's Cross), was a state decoration conferred by the government of the German ReichStatuto ...

to encourage women to stay at home and have babies.

Effect on the war

The exact influence of Ultra on the course of the war is debated; an oft-repeated assessment is that decryption of German ciphers advanced the end of the European war by no less than two years. Hinsley, who first made this claim, is typically cited as an authority for the two-year estimate. Winterbotham's quoting of Eisenhower's "decisive" verdict is part of a letter sent by Eisenhower to Menzies after the conclusion of the European war and later found among his papers at the Eisenhower Presidential Library. It allows a contemporary, documentary view of a leader on Ultra's importance: There is wide disagreement about the importance of codebreaking in winning the crucialBattle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

. To cite just one example, the historian Max Hastings states that "In 1941 alone, Ultra saved between 1.5 and two million tons of Allied ships from destruction." This would represent a 40 percent to 53 percent reduction, though it is not clear how this extrapolation was made.

Another view is from a history based on the German naval archives written after the war for the British Admiralty by a former U-boat commander and son-in-law of his commander, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

. His book reports that several times during the war they undertook detailed investigations to see whether their operations were being compromised by broken Enigma ciphers. These investigations were spurred because the Germans had broken the British naval code and found the information useful. Their investigations were negative, and the conclusion was that their defeat "was due firstly to outstanding developments in enemy radar..." The great advance was centimetric radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weat ...

, developed in a joint British-American venture, which became operational in the spring of 1943. Earlier radar was unable to distinguish U-boat conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

s from the surface of the sea, so it could not even locate U-boats attacking convoys on the surface on moonless nights; thus the surfaced U-boats were almost invisible, while having the additional advantage of being swifter than their prey. The new higher-frequency radar could spot conning towers, and periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

s could even be detected from airplanes. Some idea of the relative effect of cipher-breaking and radar improvement can be obtained from graphs

Graph may refer to:

Mathematics

*Graph (discrete mathematics), a structure made of vertices and edges

**Graph theory, the study of such graphs and their properties

*Graph (topology), a topological space resembling a graph in the sense of discre ...

showing the tonnage of merchantmen sunk and the number of U-boats sunk in each month of the Battle of the Atlantic. The graphs cannot be interpreted unambiguously, because it is challenging to factor in many variables such as improvements in cipher-breaking and the numerous other advances in equipment and techniques used to combat U-boats. Nonetheless, the data seem to favor the view of the former U-boat commander—that radar was crucial.

While Ultra certainly affected the course of the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

during the war, two factors often argued against Ultra having shortened the overall war by a measure of years are the relatively small role it played in the Eastern Front conflict between Germany and the Soviet Union, and the completely independent development of the U.S.-led Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

to create the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. Author Jeffrey T. Richelson Jeffrey Talbot Richelson (31 December 1949 – 11 November 2017) was an American author and academic researcher who studied the process of intelligence gathering and national security. He authored at least thirteen books and many articles about int ...

mentions Hinsley's estimate of at least two years, and concludes that "It might be more accurate to say that Ultra helped shorten the war by three months – the interval between the actual end of the war in Europe and the time the United States would have been able to drop an atomic bomb on Hamburg or Berlin – and might have shortened the war by as much as two years had the U.S. atomic bomb program been unsuccessful." Military historian Guy Hartcup

Guy Hartcup (13 May 1919 – 18 March 2012) was an author and military historian. His published works focused on the history of 20th-century military technology.

Publications

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

References

External linksLibrary of Congress Cat ...

analyzes aspects of the question but then simply says, "It is impossible to calculate in terms of months or years how much Ultra shortened the war."

Postwar disclosures

While it is obvious why Britain and the U.S. went to considerable pains to keep Ultra a secret until the end of the war, it has been a matter of some conjecture why Ultra was kept officially secret for 29 years thereafter, until 1974. During that period, the important contributions to the war effort of a great many people remained unknown, and they were unable to share in the glory of what is now recognised as one of the chief reasons the Allies won the war – or, at least, as quickly as they did. At least three versions exist as to why Ultra was kept secret so long. Each has plausibility, and all may be true. First, as David Kahn pointed out in his 1974 ''New York Times'' review of Winterbotham's ''The Ultra Secret'', after the war, surplus Enigmas and Enigma-like machines were sold toThird World

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

countries, which remained convinced of the security of the remarkable cipher machines. Their traffic was not as secure as they believed, however, which is one reason the British made the machines available.

By the 1970s, newer computer-based ciphers were becoming popular as the world increasingly turned to computerised communications, and the usefulness of Enigma copies (and rotor machines generally) rapidly decreased. Switzerland developed its own version of Enigma, known as NEMA

The National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) is the largest trade association of electrical equipment manufacturers in the United States. Founded in 1926, it advocates for the industry, and publishes standards for electrical product ...

, and used it into the late 1970s, while the United States National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collecti ...

(NSA) retired the last of its rotor-based encryption systems, the KL-7

The TSEC/KL-7, also known as Adonis was an off-line non-reciprocal rotor encryption machine.

series, in the 1980s.

A second explanation relates to a misadventure of Churchill's between the World Wars, when he publicly disclosed information from decrypted Soviet communications. This had prompted the Soviets to change their ciphers, leading to a blackout.

The third explanation is given by Winterbotham, who recounts that two weeks after V-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easter ...

, on 25 May 1945, Churchill requested former recipients of Ultra intelligence not to divulge the source or the information that they had received from it, in order that there be neither damage to the future operations of the Secret Service nor any cause for the Axis to blame Ultra for their defeat.

Since it was British and, later, American message-breaking which had been the most extensive, the importance of Enigma decrypts to the prosecution of the war remained unknown despite revelations by the Poles and the French of their early work on breaking the Enigma cipher. This work, which was carried out in the 1930s and continued into the early part of the war, was necessarily uninformed regarding further breakthroughs achieved by the Allies during the balance of the war. In 1967, Polish military historian Władysław Kozaczuk Władysław Kozaczuk (23 December 1923 – 26 September 2003) was a Polish Army colonel and a military and intelligence historian.

Life

Born in the village of Babiki near Sokółka, Kozaczuk joined the army in 1944, during World War II, at Bia� ...

in his book ''Bitwa o tajemnice'' ("Battle for Secrets") first revealed Enigma had been broken by Polish cryptologists before World War II. Later the 1973 public disclosure of Enigma decryption in the book ''Enigma'' by French intelligence officer Gustave Bertrand

Gustave Bertrand (1896–1976) was a French military intelligence officer who made a vital contribution to the decryption, by Poland's Cipher Bureau, of German Enigma ciphers, beginning in December 1932. This achievement would in turn lead to ...

generated pressure to discuss the rest of the Enigma–Ultra story.

In 1967, David Kahn in ''The Codebreakers