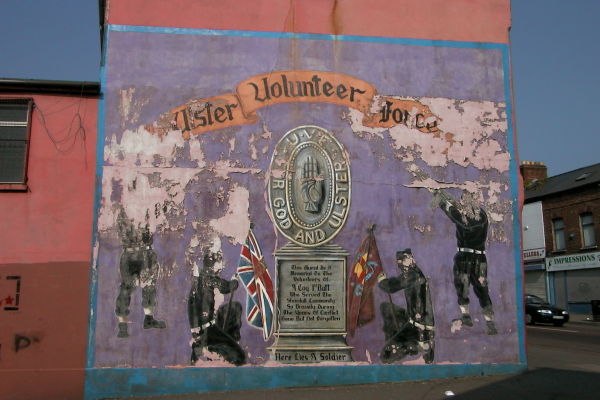

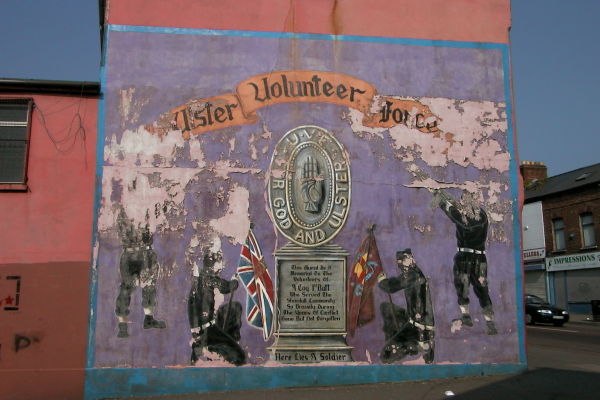

Ulster Volunteer Force on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an

Ulster loyalist

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a u ...

paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence

Augustus Andrew Spence (28 June 1933

. ''

.

On 7 May 1966, loyalists

On 7 May 1966, loyalists

. ''

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

soldier from Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. The group undertook an armed campaign of almost thirty years during The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an " ...

. It declared a ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state act ...

in 1994 and officially ended its campaign in 2007, although some of its members have continued to engage in violence and criminal activities. The group is a proscribed organisation and is on the terrorist organisation list of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

.

The UVF's declared goals were to combat Irish republicanism

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

– particularly the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

(IRA) – and to maintain Northern Ireland's status as part of the United Kingdom. It was responsible for more than 500 deaths. The vast majority (more than two-thirds) (choose "religion summary" + "status" + "organisation") of its victims were Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

civilians, who were often killed at random. During the conflict, its deadliest attack in Northern Ireland was the 1971 McGurk's Bar bombing

On 4 December 1971, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group, detonated a bomb at McGurk's Bar in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The pub was frequented by Irish Catholics/nationalists. The explosion caused the buildin ...

, which killed fifteen civilians. The group also carried out attacks in the Republic of Ireland from 1969 onward. The biggest of these was the 1974 Dublin and Monaghan bombings

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ce ...

, which killed 34 civilians, making it the deadliest terrorist attack of the conflict. The no-warning car bombings had been carried out by units from the Belfast and Mid-Ulster brigades. The Mid-Ulster Brigade was also responsible for the 1975 Miami Showband killings

The Miami Showband killings (also called the Miami Showband massacre) was an attack on 31 July 1975 by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a loyalist paramilitary group. It took place on the A1 road at Buskhill in County Down, Northern Ireland. ...

, in which three members of the popular Irish cabaret band were shot dead at a bogus military checkpoint by gunmen in British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

uniforms. Two UVF men were accidentally blown up in this attack. The UVF's last major attack was the 1994 Loughinisland massacre

The Loughinisland massacre O'Brien, Brendan. ''The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin''. Syracuse University Press, 1999. Page 314. took place on 18 June 1994 in the small village of Loughinisland, County Down, Northern Ireland. Members of the U ...

, in which its members shot dead six Catholic civilians in a rural pub. Until recent years, it was noted for secrecy and a policy of limited, selective membership.Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.34 Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald, ''UVF'', Poolbeg, 1997, p. 107 The other main loyalist paramilitary group during the conflict was the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

(UDA), which had a much larger membership.

Since the ceasefire, the UVF has been involved in rioting, drug dealing, organised crime, loan-sharking and prostitution. Some members have also been found responsible for orchestrating a series of racist attacks.

History

Background

Since 1964 and the formation of theCampaign for Social Justice

The Campaign for Social Justice (CSJ) was an organisation based in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in th ...

, there had been a growing civil rights campaign in Northern Ireland, seeking to highlight discrimination against Catholics by the unionist government of Northern Ireland

The government of Northern Ireland is, generally speaking, whatever political body exercises political authority over Northern Ireland. A number of separate systems of government exist or have existed in Northern Ireland.

Following the partitio ...

.Chronology of Key Events in Irish History, 1800 to 1967.

Conflict Archive on the Internet

CAIN (Conflict Archive on the Internet) is a database containing information about Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland from 1968 to the present. The project began in 1996, with the website launching in 1997. The project is based within Ul ...

(CAIN). Retrieved 11 June 2013. Some unionists feared Irish nationalism and launched an opposing response in Northern Ireland. In April 1966, Ulster loyalist

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a u ...

s led by Ian Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, (6 April 1926 – 12 September 2014) was a Northern Irish loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader who served as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 1971 to 2008 and First ...

, a Protestant fundamentalist preacher, founded the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee

The Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) was established in Northern Ireland in April 1966. The UCDC was the governing body of the loyalist Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV). The UCDC coordinated parades, counter demonstrations, and p ...

(UCDC). It set up a paramilitary-style wing called the Ulster Protestant Volunteers

The Ulster Protestant Volunteers was a loyalist and Reformed fundamentalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. They were active between 1966 and 1969 and closely linked to the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) and Ulster Voluntee ...

(UPV). The 'Paisleyites' set out to stymie the civil rights movement and oust Terence O'Neill

Terence Marne O'Neill, Baron O'Neill of the Maine, PC (NI) (10 September 1914 – 12 June 1990), was the fourth prime minister of Northern Ireland and leader (1963–1969) of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP). A moderate unionist, who sought ...

, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland

The prime minister of Northern Ireland was the head of the Government of Northern Ireland between 1921 and 1972. No such office was provided for in the Government of Ireland Act 1920; however, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, as with governo ...

. Although O'Neill was a unionist, they saw him as being too 'soft' on the civil rights movement and too friendly with the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

. There was to be much overlap in membership between the UCDC/UPV and the UVF.

Beginnings

petrol bomb

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with fla ...

ed a Catholic-owned pub

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

in the loyalist Shankill area of Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

. Fire engulfed the house next door, badly burning the elderly Protestant widow who lived there. She died of her injuries on 27 June. The group called itself the "Ulster Volunteer Force" (UVF), after the Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

of the early 20th century, although in the words of a member of the previous organisation "the present para-military organisation ... has no connection with the U.V.F. of which I have been speaking. Though, for its own purposes, it assumed the same name it has nothing else in common." It was led by Gusty Spence

Augustus Andrew Spence (28 June 1933

. ''

In 1974, hardliners staged a coup and took over the Brigade Staff. This resulted in a sharp increase in sectarian killings and internecine feuding, both with the UDA and within the UVF itself.Nelson, Sarah (1984). ''Ulster's Uncertain Defenders: Protestant Paramilitary, Political and Community Groups and the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Belfast: Appletree Press. p. 175, pp. 187–190. Some of the new Brigade Staff members bore nicknames such as "Big Dog" and "Smudger".Nelson, p. 188 Beginning in 1975, recruitment to the UVF, which until then had been solely by invitation, was now left to the discretion of local units.

The UVF's Mid-Ulster Brigade carried out further attacks during this same period. These included the

In 1974, hardliners staged a coup and took over the Brigade Staff. This resulted in a sharp increase in sectarian killings and internecine feuding, both with the UDA and within the UVF itself.Nelson, Sarah (1984). ''Ulster's Uncertain Defenders: Protestant Paramilitary, Political and Community Groups and the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Belfast: Appletree Press. p. 175, pp. 187–190. Some of the new Brigade Staff members bore nicknames such as "Big Dog" and "Smudger".Nelson, p. 188 Beginning in 1975, recruitment to the UVF, which until then had been solely by invitation, was now left to the discretion of local units.

The UVF's Mid-Ulster Brigade carried out further attacks during this same period. These included the

The arms are thought to have consisted of:

*200 Czechoslovak Sa vz. 58 automatic rifles,

*90 Browning pistols,

*500

The arms are thought to have consisted of:

*200 Czechoslovak Sa vz. 58 automatic rifles,

*90 Browning pistols,

*500

In 1990, the UVF joined the

In 1990, the UVF joined the

''The Independent'', 3 August 1996; Retrieved 18 October 2009 There followed years of violence between the two organisations. In January 2000 UVF Mid-Ulster brigadier Richard Jameson was shot dead by a LVF gunman which led to an escalation of the UVF/LVF feud. The UVF was also clashing with the UDA in the summer of 2000. The feud with the UDA ended in December following seven deaths. Veteran anti-UVF campaigner Raymond McCord, whose son, Raymond Jr., a Protestant, was beaten to death by UVF men in 1997, estimates the UVF has killed more than thirty people since its 1994 ceasefire, most of them Protestants. The feud between the UVF and the LVF erupted again in the summer of 2005. The UVF killed four men in Belfast and trouble ended only when the LVF announced that it was disbanding in October of that year.

On 14 September 2005, following serious loyalist rioting during which dozens of shots were fired at riot police and the

There followed years of violence between the two organisations. In January 2000 UVF Mid-Ulster brigadier Richard Jameson was shot dead by a LVF gunman which led to an escalation of the UVF/LVF feud. The UVF was also clashing with the UDA in the summer of 2000. The feud with the UDA ended in December following seven deaths. Veteran anti-UVF campaigner Raymond McCord, whose son, Raymond Jr., a Protestant, was beaten to death by UVF men in 1997, estimates the UVF has killed more than thirty people since its 1994 ceasefire, most of them Protestants. The feud between the UVF and the LVF erupted again in the summer of 2005. The UVF killed four men in Belfast and trouble ended only when the LVF announced that it was disbanding in October of that year.

On 14 September 2005, following serious loyalist rioting during which dozens of shots were fired at riot police and the

/ref> The

, '' Belfast Telegraph'', 23 June 2011 The UVF leader in East Belfast, who is popularly known as the "Beast of the East" and "Ugly Doris" also known as by real name Stephen Matthews, ordered the attack on Catholic homes and a church in the Catholic enclave of the Short Strand. This was in retaliation for attacks on Loyalist homes the previous weekend and after a young girl was hit in the face with a brick by Republicans. A dissident Republican was arrested for "the attempted murder of police officers in east Belfast" after shots were fired upon the police. In July 2011, a UVF flag flying in

. ''

Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule m ...

MP, who told him that the UVF was to be re-established and that he was to have responsibility for the Shankill.Hennessey, Thomas. ''Northern Ireland: The Origin of the Troubles''. Gill & Macmillan, 2005. p. 55 On 21 May, the group issued a statement:From this day, we declare war against the Irish Republican Army and its splinter groups. Known IRA men will be executed mercilessly and without hesitation. Less extreme measures will be taken against anyone sheltering or helping them, but if they persist in giving them aid, then more extreme methods will be adopted. ... we solemnly warn the authorities to make no more speeches of appeasement. We are heavily armed Protestants dedicated to this cause.On 27 May, Spence sent four UVF members to kill IRA volunteer Leo Martin, who lived in Belfast. Unable to find their target, the men drove around the Falls district in search of a Catholic. They shot John Scullion, a Catholic civilian, as he walked home.Dillon, Martin. ''The Shankill Butchers: The Real Story of Cold-Blooded Mass Murder''. Routledge, 1999. pp. 20–23 He died of his wounds on 11 June. Spence later wrote "At the time, the attitude was that if you couldn't get an IRA man you should shoot a

Taig

Taig, and (primarily formerly) also Teague, are anglicisations of the Irish-language male given name '' Tadhg'', used as ethnic slurs for a stage Irishman. ''Taig'' in Northern Ireland is most commonly used as a derogatory term by loyalists to re ...

, he's your last resort".

On 26 June, the group shot dead a Catholic civilian and wounded two others as they left a pub on Malvern Street, Belfast. Two days later, the Government of Northern Ireland

The government of Northern Ireland is, generally speaking, whatever political body exercises political authority over Northern Ireland. A number of separate systems of government exist or have existed in Northern Ireland.

Following the partitio ...

declared the UVF illegal. The shootings led to Spence's being sentenced to life imprisonment with a recommended minimum sentence of twenty years. Spence appointed Samuel McClelland

Samuel "Bo" McClelland was a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary who served as the Chief of Staff on the Ulster Volunteer Force's Brigade Staff (UVF) from 1966 until his internment in late 1973.

UVF leadership

Following the imprisonment of UV ...

as UVF Chief of Staff in his stead.Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald. ''UVF''. Poolbeg, 1997. p. 21

Violence escalates

By 1969, the Catholic civil rights movement had escalated its protest campaign, and O'Neill had promised them some concessions. In March and April that year, UVF and UPV members bombed water and electricity installations in Northern Ireland, blaming them on the dormant IRA and elements of the civil rights movement. Some of them left much of Belfast without power and water. The loyalists "intended to force a crisis which would so undermine confidence in O'Neill's ability to maintain law and order that he would be obliged to resign". There were bombings on 30 March, 4 April, 20 April, 24 April and 26 April. All were widely blamed on the IRA, and British soldiers were sent to guard installations. Unionist support for O'Neill waned, and on 28 April he resigned as Prime Minister. On 12 August 1969, the "Battle of the Bogside

The Battle of the Bogside was a large three-day riot that took place from 12 to 14 August 1969 in Derry, Northern Ireland. Thousands of Catholic/Irish nationalist residents of the Bogside district, organised under the Derry Citizens' Defence ...

" began in Derry. This was a large, three-day riot between Irish nationalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). In response to events in Derry, nationalists held protests throughout Northern Ireland, some of which became violent. In Belfast, loyalists responded by attacking nationalist districts. Eight people were shot dead and hundreds were injured. Scores of houses and businesses were burnt out, most of them owned by Catholics. The British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

were deployed on the streets of Northern Ireland. The Irish Army

The Irish Army, known simply as the Army ( ga, an tArm), is the land component of the Defence Forces of Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. The A ...

set up field hospital

A field hospital is a temporary hospital or mobile medical unit that takes care of casualties on-site before they can be safely transported to more permanent facilities. This term was initially used in military medicine (such as the Mobile A ...

s near the border. Thousands of families, mostly Catholics, were forced to flee their homes and refugee camp

A refugee camp is a temporary settlement built to receive refugees and people in refugee-like situations. Refugee camps usually accommodate displaced people who have fled their home country, but camps are also made for internally displaced peo ...

s were set up in the Republic of Ireland.

On 12 October, a loyalist protest in the Shankill became violent. During the riot, UVF members shot dead RUC officer Victor Arbuckle. He was the first RUC officer to be killed during the Troubles.

The UVF had launched its first attack in the Republic of Ireland on 5 August 1969, when it bombed the RTÉ Television Centre

The RTÉ Television Centre is a television studio building which is owned by Ireland's national public service broadcaster Raidió Teilifís Éireann. It is part of the RTÉ campus located at Donnybrook in South Dublin. The building houses ...

in Dublin. There were further attacks in the Republic between October and December 1969. In October, UVF and UPV member Thomas McDowell was killed by the bomb he was planting at Ballyshannon

Ballyshannon () is a town in County Donegal, Ireland. It is located at the southern end of the county where the N3 from Dublin ends and the N15 crosses the River Erne. Incorporated in 1613, it is one of the oldest towns in Ireland.

Location

B ...

power station. The UVF stated that the attempted attack was a protest against the Irish Army units "still massed on the border in County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ga, Contae Dhún na nGall) is a county of Ireland in the province of Ulster and in the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Donegal in the south of the county. It has also been known as County Tyrconne ...

". In December, the UVF detonated a car bomb near the Garda central detective bureau and telephone exchange headquarters in Dublin.

Early to mid-1970s

In January 1970, the UVF began bombing Catholic-owned businesses in Protestant areas of Belfast. It issued a statement vowing to "remove republican elements from loyalist areas" and stop them "reaping financial benefit therefrom". During 1970, 42 Catholic-owned licensed premises in Protestant areas were bombed.Cusack & McDonald, pp. 83–85 Catholic churches were also attacked. In February, it began to target critics of militant loyalism – the homes of MPsAustin Currie

Joseph Austin Currie (11 October 1939 – 9 November 2021) was an Irish politician who served as a Minister of State for Justice with responsibility for Children's Rights from 1994 to 1997. He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin Wes ...

, Sheelagh Murnaghan

Sheelagh Mary Murnaghan, (26 May 1924 – 14 September 1993) was an Ulster Liberal Party Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of Northern Ireland at Stormont.

Early life

Sheelagh Mary Murnaghan was born on 24 May 1924 to Josep ...

, Richard Ferguson and Anne Dickson were attacked with improvised bombs. It also continued its attacks in the Republic of Ireland, bombing the Dublin-Belfast railway line, an electricity substation, a radio mast, and Irish nationalist monuments.Cusack & McDonald, pp. 77–78

The IRA had split into the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, fa ...

and Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA (OIRA; ) was an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a "workers' republic" encompassing all of Ireland. It emerged ...

in December 1969. In 1971, these ramped up their activity against the British Army and RUC. The first British soldier to be killed by the Provisional IRA died in February 1971. That year, a string of tit-for-tat pub bombings began in Belfast. This came to a climax on 4 December, when the UVF bombed McGurk's Bar, a Catholic-owned pub in Belfast. Fifteen Catholic civilians were killed and seventeen wounded. It was the UVF's deadliest attack in Northern Ireland, and the deadliest attack in Belfast during the Troubles.

The following year, 1972, was the most violent of the Troubles. Along with the newly formed Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

(UDA), the UVF started an armed campaign against the Catholic population of Northern Ireland. It began carrying out gun attacks to kill random Catholic civilians and using car bombs to attack Catholic-owned pubs. It would continue these tactics for the rest of its campaign. On 23 October 1972, the UVF carried out an armed raid against King's Park camp, a UDR/ Territorial Army depot in Lurgan. They managed to procure a large cache of weapons and ammunition including L1A1 Self-Loading Rifles, Browning pistols, and Sterling submachine guns. Twenty tons of ammonium nitrate

Ammonium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a white crystalline salt consisting of ions of ammonium and nitrate. It is highly soluble in water and hygroscopic as a solid, although it does not form hydrates. It is ...

was also stolen from the Belfast docks.

The UVF launched further attacks in the Republic of Ireland during December 1972 and January 1973, when it detonated three car bombs in Dublin and one in Belturbet

Belturbet (; ) is a town in County Cavan, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It lies on the N3 road (Ireland), N3 road, around north of Cavan town and from Dublin. It is also located around south of the border with Northern Ireland, between the c ...

, County Cavan

County Cavan ( ; gle, Contae an Chabháin) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is part of the Border Region. It is named after the town of Cavan and is base ...

, killing a total of five civilians. It would attack the Republic again in May 1974, during the two-week Ulster Workers' Council strike

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during " the Troubles". The strike was called by unionists who were against the Sunningdale Agreement, which had ...

. This was a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

in protest against the Sunningdale Agreement

The Sunningdale Agreement was an attempt to establish a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive and a cross-border Council of Ireland. The agreement was signed at Sunningdale Park located in Sunningdale, Berkshire, on 9 December 1973. Unioni ...

, which meant sharing political power with Irish nationalists and the Republic having more involvement in Northern Ireland. Along with the UDA, it helped to enforce the strike by blocking roads, intimidating workers, and shutting any businesses that opened. On 17 May, two UVF units from the Belfast and Mid-Ulster brigades detonated four car bombs in Dublin and Monaghan

Monaghan ( ; ) is the county town of County Monaghan, Ireland. It also provides the name of its civil parish and barony.

The population of the town as of the 2016 census was 7,678. The town is on the N2 road from Dublin to Derry and Lette ...

. Thirty-three people were killed and almost 300 injured. It was the deadliest attack of the Troubles. There are various credible allegations that elements of the British security forces colluded with the UVF in the bombings. The Irish parliament's Joint Committee on Justice called the bombings an act of "international terrorism" involving the British security forces. Both the UVF and the British Government have denied the claims.

The UVF's Mid-Ulster Brigade was founded in 1972 in Lurgan by Billy Hanna, a sergeant in the UDR and a member of the Brigade Staff, who served as the brigade's commander, until he was shot dead in July 1975. From that time until the early 1990s the Mid-Ulster Brigade was led by Robin "the Jackal" Jackson, who then passed the leadership to Billy Wright. Hanna and Jackson have both been implicated by journalist Joe Tiernan and RUC Special Patrol Group

The Special Patrol Group (SPG) was a unit of Greater London's Metropolitan Police Service, responsible for providing a centrally based mobile capacity to combat serious public disorder, crime, and terrorism, that could not be dealt with by loca ...

(SPG) officer John Weir as having led one of the units that bombed Dublin. Jackson was allegedly the hitman who shot Hanna dead outside his home in Lurgan.

The brigade formed part of the Glenanne gang

The Glenanne gang or Glenanne group was a secret informal alliance of Ulster loyalists who carried out shooting and bombing attacks against Catholics and Irish nationalists in the 1970s, during the Troubles.

, a loose alliance of loyalist assassins which the Pat Finucane Centre

The Pat Finucane Centre (PFC) is a human rights advocacy and lobbying entity in Northern Ireland. Named in honour of murdered solicitor Pat Finucane, it operates advice centres in Derry and Newry, dealing mainly with complaints from Irish nati ...

has linked to 87 killings in the 1970s. The gang comprised, in addition to the UVF, rogue elements of the UDR, RUC, SPG, and the regular Army, all acting allegedly under the direction of the British Intelligence Corps and/or RUC Special Branch

RUC Special Branch was the Special Branch of the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constab ...

.

Mid- to late 1970s

In 1974, hardliners staged a coup and took over the Brigade Staff. This resulted in a sharp increase in sectarian killings and internecine feuding, both with the UDA and within the UVF itself.Nelson, Sarah (1984). ''Ulster's Uncertain Defenders: Protestant Paramilitary, Political and Community Groups and the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Belfast: Appletree Press. p. 175, pp. 187–190. Some of the new Brigade Staff members bore nicknames such as "Big Dog" and "Smudger".Nelson, p. 188 Beginning in 1975, recruitment to the UVF, which until then had been solely by invitation, was now left to the discretion of local units.

The UVF's Mid-Ulster Brigade carried out further attacks during this same period. These included the

In 1974, hardliners staged a coup and took over the Brigade Staff. This resulted in a sharp increase in sectarian killings and internecine feuding, both with the UDA and within the UVF itself.Nelson, Sarah (1984). ''Ulster's Uncertain Defenders: Protestant Paramilitary, Political and Community Groups and the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Belfast: Appletree Press. p. 175, pp. 187–190. Some of the new Brigade Staff members bore nicknames such as "Big Dog" and "Smudger".Nelson, p. 188 Beginning in 1975, recruitment to the UVF, which until then had been solely by invitation, was now left to the discretion of local units.

The UVF's Mid-Ulster Brigade carried out further attacks during this same period. These included the Miami Showband killings

The Miami Showband killings (also called the Miami Showband massacre) was an attack on 31 July 1975 by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a loyalist paramilitary group. It took place on the A1 road at Buskhill in County Down, Northern Ireland. ...

of 31 July 1975 – when three members of the popular showband were killed, having been stopped at a fake British Army checkpoint outside Newry

Newry (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Clanrye river in counties Armagh and Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry was founded in 1144 alongside a Cistercian monastery, althoug ...

in County Down. Two members of the group survived the attack and later testified against those responsible. Two UVF members, Harris Boyle

Harris Boyle (1953 – 31 July 1975) was an Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) soldier and a high-ranking member of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary organisation. Boyle was implicated in the 1974 Dublin a ...

and Wesley Somerville

William Wesley Somerville ( – 31 July 1975) was an Ulster loyalist militant, who held the rank of lieutenant in the illegal Ulster Volunteer Force's (UVF) Mid-Ulster Brigade during the period of conflict known as "the Troubles". With claims t ...

, were accidentally killed by their own bomb while carrying out this attack. Two of those later convicted (James McDowell and Thomas Crozier) were also serving members of the Ulster Defence Regiment

The Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was an infantry regiment of the British Army established in 1970, with a comparatively short existence ending in 1992. Raised through public appeal, newspaper and television advertisements,Potter p25 their offi ...

(UDR), a part-time, locally recruited regiment of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

.

From late 1975 to mid-1977, a unit of the UVF dubbed the Shankill Butchers

The Shankill Butchers were an Ulster loyalist gang—many of whom were members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)—that was active between 1975 and 1982 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It was based in the Shankill area and was responsible for t ...

(a group of UVF men based on Belfast's Shankill Road) carried out a series of sectarian murders of Catholic civilians. Six of the victims were abducted at random, then beaten and tortured before having their throats slashed. This gang was led by Lenny Murphy

Hugh Leonard Thompson Murphy (2 March 1952 – 16 November 1982) was a Northern Irish loyalist and UVF officer. As leader of the Shankill Butchers gang, Murphy was responsible for many murders, mainly of Catholic civilians, often first kidna ...

. He was shot dead by the IRA in November 1982, four months after his release from the Maze Prison

Her Majesty's Prison Maze (previously Long Kesh Detention Centre, and known colloquially as The Maze or H-Blocks) was a prison in Northern Ireland that was used to house alleged paramilitary prisoners during the Troubles from August 1971 to Sep ...

.

The group had been proscribed in July 1966, but this ban was lifted on 4 April 1974 by Merlyn Rees

Merlyn Merlyn-Rees, Baron Merlyn-Rees, (né Merlyn Rees; 18 December 1920 – 5 January 2006) was a British Labour Party politician and Member of Parliament from 1963 until 1992. He served as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (1974–197 ...

, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, in an effort to bring the UVF into the democratic process. A political wing was formed in June 1974, the Volunteer Political Party

The Volunteer Political Party (VPP) was a loyalist political party launched in Northern Ireland on 22 June 1974 by members of the then recently legalised Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). The Chairman was Ken Gibson from East Belfast, an ex-internee ...

led by UVF Chief of Staff Ken Gibson, which contested West Belfast in the October 1974 general election, polling 2,690 votes (6%). However, the UVF spurned the government efforts and continued killing. Colin Wallace

John Colin Wallace (born June 1943) is a British former member of Army Intelligence in Northern Ireland and a psychological warfare specialist. He refused to become involved in the Intelligence-led 'Clockwork Orange' project, which was an att ...

, part of the intelligence apparatus of the British Army, asserted in an internal memo in 1975 that MI6 and RUC Special Branch

RUC Special Branch was the Special Branch of the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constab ...

formed a pseudo-gang

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

within the UVF, designed to engage in violence and to subvert the tentative moves of some in the UVF towards the political process. Captain Robert Nairac

Captain Robert Laurence Nairac (31 August 1948 – 15 May 1977) was a British Army officer in the Grenadier Guards who was abducted from a pub in Dromintee, south County Armagh, during an undercover operation and killed by the Provisional Irish ...

of 14 Intelligence Company was alleged to have been involved in many acts of UVF violence. The UVF was banned again on 3 October 1975 and two days later twenty-six suspected UVF members were arrested in a series of raids. The men were tried, and in March 1977 were sentenced to an average of twenty-five years each.

In October 1975, after staging a counter-coup, the Brigade Staff acquired a new leadership of moderates with Tommy West serving as the Chief of Staff. These men had overthrown the "hawkish" officers, who had called for a "big push", which meant an increase in violent attacks, earlier in the same month.Taylor, pp. 152–156 The UVF was behind the deaths of seven civilians in a series of attacks on 2 October. The hawks had been ousted by those in the UVF who were unhappy with their political and military strategy. The new Brigade Staff's aim was to carry out attacks against known republicans rather than Catholic civilians. This was endorsed by Gusty Spence, who issued a statement asking all UVF volunteers to support the new regime.Dillon, Martin (1989). ''The Shankill Butchers: The Real Story of Cold-Blooded Mass Murder''. New York: Routledge. p. 53 The UVF's activities in the last years of the decade were increasingly being curtailed by the number of UVF members who were sent to prison. The number of killings in Northern Ireland had decreased from around 300 per year between 1973 and 1976 to just under 100 in the years 1977–1981.Taylor, p. 157 In 1976, Tommy West was replaced with "Mr. F" who is alleged to be John "Bunter" Graham

John "Bunter" Graham (born c. 1945) is a long-standing prominent Ulster loyalist figure.

It is unknown when Graham joined the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) but he quickly rose high in its ranks as a member of the "Brigade Staff" (Belfast leadership ...

, who remains the incumbent Chief of Staff to date. West died in 1980.

On 17 February 1979, the UVF carried out its only major attack in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, when its members bombed two pubs in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

frequented by Irish-Scots Catholics. Both pubs were wrecked and a number of people were wounded. It claimed the pubs were used for republican fundraising. In June, nine UVF members were convicted of the attacks.

Early to mid-1980s

In the 1980s, the UVF was greatly reduced by a series of policeinformer

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a “snitch”) is a person who provides privileged information about a person or organization to an agency. The term is usually used within the law-enforcement world, where informan ...

s. The damage from security service informers started in 1983 with "supergrass" Joseph Bennett's information, which led to the arrest of fourteen senior figures. In 1984, the UVF attempted to kill the northern editor of the '' Sunday World'', Jim Campbell after he had exposed the paramilitary activities of Mid-Ulster brigadier Robin Jackson

Robert John Jackson (27 September 1948 – 30 May 1998), also known as The Jackal, was a Northern Irish loyalist paramilitary and part-time soldier. He was a senior officer in the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) during the period of viole ...

. Another loyalist paramilitary organisation called Ulster Resistance

Ulster Resistance (UR), or the Ulster Resistance Movement (URM), is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist Ulster loyalism#Paramilitary and vigilante groups, paramilitary movement established by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in Northern Irela ...

was formed on 10 November 1986. The initial aim of Ulster Resistance was to bring an end to the Anglo-Irish Agreement

The Anglo-Irish Agreement was a 1985 treaty between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland which aimed to help bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The treaty gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Irela ...

. Loyalists were successful in importing arms into Northern Ireland. The weapons were Palestine Liberation Organisation

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establishing Arab unity and sta ...

arms captured by the Israelis and sold to Armscor, the South African state-owned company which, in defiance of a 1977 United Nations arms embargo, set about making South Africa self-sufficient in military hardware. The arms were divided between the UVF, the UDA (the largest loyalist group) and Ulster Resistance.

The arms are thought to have consisted of:

*200 Czechoslovak Sa vz. 58 automatic rifles,

*90 Browning pistols,

*500

The arms are thought to have consisted of:

*200 Czechoslovak Sa vz. 58 automatic rifles,

*90 Browning pistols,

*500 RGD-5

The RGD-5 (''Ruchnaya Granata Distantsionnaya'', English "Hand Grenade Remote") is a post–World War II Soviet anti-personnel fragmentation grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but ...

fragmentation grenades,

*30,000 rounds of ammunition and

*12 RPG-7

The RPG-7 (russian: link=no, РПГ-7, Ручной Противотанковый Гранатомёт, Ruchnoy Protivotankoviy Granatomyot) is a portable, reusable, unguided, shoulder-launched, anti-tank, rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Th ...

rocket launchers and 150 warheads.

The UVF used this new infusion of arms to escalate their campaign of sectarian assassinations. This era also saw a more widespread targeting on the UVF's part of IRA and Sinn Féin members, beginning with the killing of senior IRA member Larry Marley

Laurence Marley (c. 1945 – 2 April 1987) was a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) member from Ardoyne, Belfast, Northern Ireland. He was one of the masterminds behind the 1983 mass escape of republican prisoners from the Maze Prison, whe ...

Taylor, p. 197 and a failed attempt on the life of a leading republican which left three Catholic civilians dead.Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald, ''UVF'', Poolbeg, 1997, p. 250

Late 1980s and early 1990s

The UVF also attacked republican paramilitaries and political activists. These attacks were stepped up in the late 1980s and early 1990s, particularly in the east Tyrone and north Armagh areas. The largest death toll in a single attack was in the 3 March 1991 Cappagh killings, when the UVF killed IRA members John Quinn, Dwayne O'Donnell and Malcolm Nugent, and civilian Thomas Armstrong in the small village of Cappagh. Republicans responded to the attacks by assassinating senior UVF membersJohn Bingham

John Armor Bingham (January 21, 1815 – March 19, 1900) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican representative from Ohio and as the United States ambassador to Japan. In his time as a congress ...

, William "Frenchie" Marchant and Trevor King as well as Leslie Dallas, whose purported UVF membership was disputed both by his family and the UVF. The UVF also killed senior IRA paramilitary members Liam Ryan, John 'Skipper' Burns and Larry Marley

Laurence Marley (c. 1945 – 2 April 1987) was a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) member from Ardoyne, Belfast, Northern Ireland. He was one of the masterminds behind the 1983 mass escape of republican prisoners from the Maze Prison, whe ...

. According to Conflict Archive on the Internet

CAIN (Conflict Archive on the Internet) is a database containing information about Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland from 1968 to the present. The project began in 1996, with the website launching in 1997. The project is based within Ul ...

(CAIN), the UVF killed 17 active and four former republican paramilitaries. CAIN also states that republicans killed 15 UVF members, some of whom are suspected to have been set up for assassination by their colleagues.

According to journalist and author Ed Moloney

Edmund "Ed" Moloney (born 1948–9) is an Irish journalist and author best known for his coverage of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and the activities of the Provisional IRA, in particular.

He worked for the ''Hibernia'' magazine and ''Magill ...

, the UVF campaign in Mid-Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

in this period "indisputably shattered Republican morale", and put the leadership of the republican movement under intense pressure to "do something", although this has been disputed by others.

1994 ceasefire

In 1990, the UVF joined the

In 1990, the UVF joined the Combined Loyalist Military Command

The Combined Loyalist Military Command is an umbrella body for loyalist paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland set up in the early 1990s, recalling the earlier Ulster Army Council and Ulster Loyalist Central Co-ordinating Committee.

Bringing ...

(CLMC) and indicated its acceptance of moves towards peace. However, the year leading up to the loyalist ceasefire, which took place shortly after the Provisional IRA ceasefire, saw some of the worst sectarian killings carried out by loyalists during the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an " ...

. On 18 June 1994, UVF members machine-gunned a pub in the Loughinisland massacre

The Loughinisland massacre O'Brien, Brendan. ''The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin''. Syracuse University Press, 1999. Page 314. took place on 18 June 1994 in the small village of Loughinisland, County Down, Northern Ireland. Members of the U ...

in County Down, on the basis that its customers were watching the Republic of Ireland national football team

, FIFA Trigramme = IRL

, Name = Republic of Ireland

, Association = Football Association of Ireland (FAI)

, Confederation = UEFA (Europe)

, website fai.ie, Coach = Stephen Kenny (foot ...

playing in the World Cup

A world cup is a global sporting competition in which the participant entities – usually international teams or individuals representing their countries – compete for the title of world champion. The event most associated with the concept i ...

on television and were therefore assumed to be Catholics. The gunmen shot dead six people and injured five.

The UVF agreed to a ceasefire in October 1994.

Post-ceasefire activities

1994–2005

More militant members of the UVF who disagreed with the ceasefire, broke away to form theLoyalist Volunteer Force

The Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) is a small Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed by Billy Wright in 1996 when he and his unit split from the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) after breaking its ceasefire. Most of ...

(LVF), led by Billy Wright. This development came soon after the UVF's Brigade Staff in Belfast had stood down Wright and the Portadown unit of the Mid-Ulster Brigade, on 2 August 1996, for the killing of a Catholic taxi driver near Lurgan during Drumcree disturbances."UVF disbands unit linked to taxi murder"''The Independent'', 3 August 1996; Retrieved 18 October 2009

There followed years of violence between the two organisations. In January 2000 UVF Mid-Ulster brigadier Richard Jameson was shot dead by a LVF gunman which led to an escalation of the UVF/LVF feud. The UVF was also clashing with the UDA in the summer of 2000. The feud with the UDA ended in December following seven deaths. Veteran anti-UVF campaigner Raymond McCord, whose son, Raymond Jr., a Protestant, was beaten to death by UVF men in 1997, estimates the UVF has killed more than thirty people since its 1994 ceasefire, most of them Protestants. The feud between the UVF and the LVF erupted again in the summer of 2005. The UVF killed four men in Belfast and trouble ended only when the LVF announced that it was disbanding in October of that year.

On 14 September 2005, following serious loyalist rioting during which dozens of shots were fired at riot police and the

There followed years of violence between the two organisations. In January 2000 UVF Mid-Ulster brigadier Richard Jameson was shot dead by a LVF gunman which led to an escalation of the UVF/LVF feud. The UVF was also clashing with the UDA in the summer of 2000. The feud with the UDA ended in December following seven deaths. Veteran anti-UVF campaigner Raymond McCord, whose son, Raymond Jr., a Protestant, was beaten to death by UVF men in 1997, estimates the UVF has killed more than thirty people since its 1994 ceasefire, most of them Protestants. The feud between the UVF and the LVF erupted again in the summer of 2005. The UVF killed four men in Belfast and trouble ended only when the LVF announced that it was disbanding in October of that year.

On 14 September 2005, following serious loyalist rioting during which dozens of shots were fired at riot police and the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

the Northern Ireland Secretary

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ...

Peter Hain

Peter Gerald Hain, Baron Hain (born 16 February 1950), is a British politician who served as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland from 2005 to 2007, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions from 2007 to 2008 and twice as Secretary of State ...

announced that the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

no longer recognised the UVF ceasefire.

2006–2010

On 12 February 2006, ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'' reported that the UVF was to disband by the end of 2006. The newspaper also reported that the group refused to decommission its weapons.

On 2 September 2006, BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broadca ...

reported the UVF might be intending to re-enter dialogue with the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning, with a view to decommissioning of their weapons. This move came as the organisation held high-level discussions about its future.

On 3 May 2007, following recent negotiations between the Progressive Unionist Party

The Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) is a minor unionist political party in Northern Ireland. It was formed from the Independent Unionist Group operating in the Shankill area of Belfast, becoming the PUP in 1979. Linked to the Ulster Volunte ...

(PUP) and Irish Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legislature) and the o ...

Bertie Ahern

Bartholomew Patrick "Bertie" Ahern (born 12 September 1951) is an Irish former Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1997 to 2008, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1994 to 2008, Leader of the Opposition from 1994 to 1997, Tánaiste a ...

and with Police Service of Northern Ireland

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI; ga, Seirbhís Póilíneachta Thuaisceart Éireann; Ulster-Scots: ')

is the police force that serves Northern Ireland. It is the successor to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) after it was reform ...

(PSNI) Chief Constable Sir Hugh Orde

Sir Hugh Stephen Roden Orde, (born 27 August 1958) is a retired British police officer who was the president of the Association of Chief Police Officers, representing the 44 police forces of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Between 2002 a ...

, the UVF made a statement that they would transform to a "non-military, civilianised" organisation. This was to take effect from midnight. They also stated that they would retain their weaponry but put them beyond reach of normal volunteers. Their weapons stock-piles are to be retained under the watch of the UVF leadership.

In January 2008, the UVF was accused of involvement in vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without Right, legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a pers ...

action against alleged criminals in Belfast.

In 2008, a loyalist splinter group calling itself the "Real UVF" emerged briefly to make threats against Sinn Féin in County Fermanagh.

In the twentieth IMC report, the group was said to be continuing to put its weapons "beyond reach", (in the group's own words) to downsize, and reduce the criminality of the group. The report added that individuals, some current and some former members, in the group have, without the orders from above, continued to "localised recruitment", and although some continued to try and acquire weapons, including a senior member, most forms of crime had fallen, including shootings and assaults. The group concluded a general acceptance of the need to decommission, though there was no conclusive proof of moves towards this end.

In June 2009 the UVF formally decommissioned their weapons in front of independent witnesses as a formal statement of decommissioning was read by Dawn Purvis

Dawn Purvis (born 22 October 1967) is a former Unionist politician in Northern Ireland, who was a Member of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLA) for Belfast East from 2007 to 2011. She was previously the leader of the Progressive Unionist Party ...

and Billy Hutchinson

Billy "Hutchie" Hutchinson (born 1955) is an Ulster Loyalist politician serving as the leader of the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) since 2011. He was elected to Belfast City Council in the 1997 elections. Hutchinson was a Member of the North ...

. The IICD confirmed that "substantial quantities of firearms, ammunition, explosives and explosive devices" had been decommissioned and that for the UVF and RHC, decommissioning had been completed.

2010–2019

The UVF was blamed for the shotgun killing of expelled RHC member Bobby Moffett on the Shankill Road on the afternoon of 28 May 2010, in front of passers-by including children.Twenty-Fourth Report of the Independent Monitoring Commission/ref> The

Independent Monitoring Commission

The Independent Monitoring Commission (IMC) was an organisation founded on 7 January 2004, by an agreement between the British and Irish governments, signed in Dublin on 25 November 2003. The IMC concluded its operations on 31 March 2011.

Remit ...

stated Moffett was killed by UVF members acting with the sanction of the leadership. The Progressive Unionist Party

The Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) is a minor unionist political party in Northern Ireland. It was formed from the Independent Unionist Group operating in the Shankill area of Belfast, becoming the PUP in 1979. Linked to the Ulster Volunte ...

's condemnation, and Dawn Purvis

Dawn Purvis (born 22 October 1967) is a former Unionist politician in Northern Ireland, who was a Member of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLA) for Belfast East from 2007 to 2011. She was previously the leader of the Progressive Unionist Party ...

and other leaders' resignations as a response to the Moffett shooting, were also noted. Eleven months later, a man was arrested and charged with the attempted murder of the UVF's alleged second-in-command Harry Stockman, described by the '' Belfast Telegraph'' as a "senior Loyalist figure". Fifty-year-old Stockman was stabbed more than 10 times in a supermarket in Belfast; the attack was believed to have been linked to the Moffett killing.

On 25–26 October 2010, the UVF was involved in rioting and disturbances in the Rathcoole area of Newtownabbey with UVF gunmen seen on the streets at the time.

On the night of 20 June 2011, riots involving 500 people erupted in the Short Strand

The Short Strand ( ga, an Trá Ghearr) is a working class, inner city area of Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is a mainly Catholic and Irish nationalist enclave surrounded by the mainly Protestant and unionist East Belfast. It is on the east ba ...

area of East Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

. They were blamed by the PSNI on members of the UVF, who also said UVF guns had been used to try to kill police officers.Is UVF’s ‘Beast in the East’ behind new wave of riots?, '' Belfast Telegraph'', 23 June 2011 The UVF leader in East Belfast, who is popularly known as the "Beast of the East" and "Ugly Doris" also known as by real name Stephen Matthews, ordered the attack on Catholic homes and a church in the Catholic enclave of the Short Strand. This was in retaliation for attacks on Loyalist homes the previous weekend and after a young girl was hit in the face with a brick by Republicans. A dissident Republican was arrested for "the attempted murder of police officers in east Belfast" after shots were fired upon the police. In July 2011, a UVF flag flying in

Limavady

Limavady (; ) is a market town in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, with Binevenagh as a backdrop. Lying east of Derry and southwest of Coleraine, Limavady had a population of 12,032 people at the United Kingdom census, 2011, 2011 Census ...

was deemed legal by the PSNI after the police had received complaints about the flag from nationalist politicians.

During the Belfast City Hall flag protests of 2012–13, senior UVF members were confirmed to have actively been involved in orchestrating violence and rioting against the PSNI and the Alliance Party throughout Northern Ireland during the weeks of disorder. Much of the UVF's orchestration was carried out by its senior members in East Belfast, where many attacks on the PSNI and on residents of the Short Strand enclave took place. There were also reports that UVF members fired shots at police lines during a protest. The high levels of orchestration by the leadership of the East Belfast UVF, and the alleged ignored orders from the main leaders of the UVF to stop the violence has led to fears that the East Belfast UVF has now become a separate loyalist paramilitary grouping which doesn't abide by the UVF ceasefire or the Northern Ireland Peace Process.

In October 2013, the policing board announced that the UVF was still heavily involved in gangsterism despite its ceasefire. Assistant chief constable Drew Harris in a statement said "The UVF are subject to an organised crime investigation as an organised crime group. The UVF very clearly have involvement in drug dealing, all forms of gangsterism, serious assaults, intimidation of the community."

In November 2013, after a series of shootings and acts of intimidation by the UVF, Police Federation Chairman Terry Spence declared that the UVF ceasefire was no longer active. Spence told Radio Ulster that the UVF had been "engaged in murder, attempted murder of civilians, attempted murder of police officers. They have been engaged in orchestrating violence on our streets, and it's very clear to me that they are engaged in an array of mafia-style activities. "They are holding local communities to ransom. On the basis of that, we as a federation have called for the respecification of the UVF tating that its ceasefire is over"

In June 2017, Gary Haggarty, former UVF commander for north Belfast and south-east Antrim, pleaded guilty to 200 charges, including five murders.

On 23 March 2019, eleven alleged UVF members were arrested during a total of 14 searches conducted in Belfast, Newtownards and Comber

Comber ( , , locally ) is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies south of Newtownards, at the northern end of Strangford Lough. It is situated in the townland of Town Parks, the civil parish of Comber and the historic barony of Ca ...

and the suspects, aged between 22 and 48, were taken into police custody for questioning. Officers from the PSNI's Paramilitary Crime Task Force also seized drugs, cash and expensive cars and jewellery in an operation carried out against the criminal activities of the UVF crime gang.

2020s

On 4 March 2021, the UVF, Red Hand Commando and UDA renounced their current participation in the Good Friday Agreement. In April 2021, riots erupted across Loyalist communities in Northern Ireland. On 11 April, the UVF reportedly ordered the removal ofCatholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

families from a housing estate in Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,998 at the 2011 Census. It is County Antrim's oldest ...

.

On 25 March 2022, the UVF was blamed for a proxy bomb attack targeting a "peace-building" event in Belfast where Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney

Simon Coveney (born 16 June 1972) is an Irish Fine Gael politician who has served as Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment since December 2022 and Deputy Leader of Fine Gael since 2017. He previously served as Minister for Foreign Affai ...

was speaking. Armed men hijacked a van on the nearby Shankill Road and forced the driver to take a device to a church on the Crumlin Road. The community centre hosting the event and 25 nearby homes were evacuated and a funeral was disrupted. A controlled explosion was carried out and the bomb was later declared a hoax.

On 26 March 2022, the UVF was linked to a hoax bomb alert at a bar in Warrenpoint, County Down.

Leadership

Brigade Staff

The UVF's leadership is based in Belfast and known as the Brigade Staff. It comprises high-ranking officers under a Chief of Staff or Brigadier-General. With a few exceptions, such as Mid-Ulster brigadier Billy Hanna (a native ofLurgan

Lurgan () is a town in County Armagh, Northern Ireland, near the southern shore of Lough Neagh. Lurgan is about south-west of Belfast and is linked to the city by both the M1 motorway and the Belfast–Dublin railway line. It had a population ...

), the Brigade Staff members have been from the Shankill Road or the neighbouring Woodvale area to the west.Anderson, Malcolm & Bort, Eberhard (1999). ''The Irish Border: History, Politics, Culture''. Liverpool University Press. p. 129 The Brigade Staff's former headquarters were situated in rooms above "The Eagle" chip shop located on the Shankill Road at its junction with Spier's Place. The chip shop has since been closed down.

In 1972, the UVF's imprisoned leader Gusty Spence

Augustus Andrew Spence (28 June 1933

. ''

. ''

Taylor, Peter (1999). ''Loyalists''. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p.112 These were all subordinate to the Brigade Staff. The incumbent Chief of Staff, is alleged to be

Retrieved 31 May 2012Dillon, p. 133 Graham has held the position since he assumed office in 1976.Moloney, Ed (2010). ''Voices From the Grave: Two Men's War in Ireland''. Faber & Faber. p. 377 The UVF's nickname is "Blacknecks", derived from their uniform of black polo neck jumper, black trousers, black leather jacket, black

Retrieved 17 November 2011 Hanna was allegedly shot dead by the UVF as a suspected informer. * Ken Gibson (1974)Coogan, Tim Pat (1995). ''The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal, 1966–1996, and the Search for Peace''. Hutchinson. p. 177 Gibson was the Chief of Staff during the

online

* * Bowman, Timothy. ''Carson's Army: The Ulster Volunteer Force, 1910–22'' (2012), a standard scholarly history * * * * * * Grob-Fitzgibbon, Benjamin. (2006) "Neglected Intelligence: How the British Government Failed to Quell the Ulster Volunteer Force, 1912–1914." ''Journal of Intelligence History'' 6.1 (2006): 1-23. * * Orr, David R. (2016) ''Ulster will Fight. Volume 1: Home Rule and the Ulster Volunteer Force 1886-1922'' (2016

excerpt

; a standard scholarly history *

CAIN – University of Ulster Conflict Archive

{{Authority control Proscribed paramilitary organisations in Northern Ireland Organizations based in Europe designated as terrorist Organisations designated as terrorist by the United Kingdom Organised crime groups in Northern Ireland Ulster loyalist militant groups

John "Bunter" Graham

John "Bunter" Graham (born c. 1945) is a long-standing prominent Ulster loyalist figure.

It is unknown when Graham joined the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) but he quickly rose high in its ranks as a member of the "Brigade Staff" (Belfast leadership ...

, referred to by Martin Dillon as "Mr. F"."The untouchable informers facing exposure at last". ''Belfast Telegraph''. David Gordon. 18 January 2007.Retrieved 31 May 2012Dillon, p. 133 Graham has held the position since he assumed office in 1976.Moloney, Ed (2010). ''Voices From the Grave: Two Men's War in Ireland''. Faber & Faber. p. 377 The UVF's nickname is "Blacknecks", derived from their uniform of black polo neck jumper, black trousers, black leather jacket, black

forage cap

Forage cap is the designation given to various types of military undress, fatigue or working headwear. These varied widely in form, according to country or period. The coloured peaked cap worn by the modern British Army for parade and other dress o ...

, along with the UVF badge and belt. This uniform, based on those of the original UVF, was introduced in the early 1970s.

Chiefs of Staff

* Gusty Spence (1966). Whilst remaining ''de jure'' UVF leader after he was jailed for murder, he no longer acted as Chief of Staff. * Sam "Bo" McClelland (1966–1973) Described as a "tough disciplinarian", he was personally appointed by Spence to succeed him as Chief of Staff, due to his having served in theKorean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

with Spence's former regiment, the Royal Ulster Rifles

The Royal Irish Rifles (became the Royal Ulster Rifles from 1 January 1921) was an infantry rifle regiment of the British Army, first created in 1881 by the amalgamation of the 83rd (County of Dublin) Regiment of Foot and the 86th (Royal County D ...

. He was interned in late 1973, although by that stage the ''de facto'' Chief of Staff was his successor, Jim Hanna.

* Jim Hanna (1973 – April 1974)"The Dublin and Monaghan bombings: Cover-up and incompetence". page 1. ''Politico''. Joe Tiernan 3 May 2007Retrieved 17 November 2011 Hanna was allegedly shot dead by the UVF as a suspected informer. * Ken Gibson (1974)Coogan, Tim Pat (1995). ''The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal, 1966–1996, and the Search for Peace''. Hutchinson. p. 177 Gibson was the Chief of Staff during the

Ulster Workers' Council Strike

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during " the Troubles". The strike was called by unionists who were against the Sunningdale Agreement, which had ...

in May 1974.

* Unnamed Chief of Staff (1974 – October 1975). Leader of the Young Citizen Volunteers (YCV), the youth wing of the UVF. Assumed command after a coup by hardliners in 1974. He, along with the other hawkish Brigade Staff members, was overthrown by Tommy West and a new Brigade Staff of "moderates" in a counter-coup supported by Gusty Spence. He left Northern Ireland after his removal from power.Moloney, Ed (2010). ''Voices From the Grave: Two Men's War in Ireland''. Faber & Faber. p. 376

* Tommy West (October 1975 – 1976) A former British Army soldier, West was already the Chief of Staff at the time UVF volunteer Noel "Nogi" Shaw was killed by Lenny Murphy

Hugh Leonard Thompson Murphy (2 March 1952 – 16 November 1982) was a Northern Irish loyalist and UVF officer. As leader of the Shankill Butchers gang, Murphy was responsible for many murders, mainly of Catholic civilians, often first kidna ...

in November 1975 as part of an internal feud.

* John "Bunter" Graham

John "Bunter" Graham (born c. 1945) is a long-standing prominent Ulster loyalist figure.

It is unknown when Graham joined the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) but he quickly rose high in its ranks as a member of the "Brigade Staff" (Belfast leadership ...

, also referred to as "Mr. F" (1976–present)

Aim and strategy

The UVF's stated goal was to combatIrish republicanism

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

– particularly the Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reun ...

(IRA) – and maintain Northern Ireland's status as part of the United Kingdom. The vast majority of its victims were Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

civilians, who were often killed at random. Whenever it claimed responsibility for its attacks, the UVF usually claimed that those targeted were IRA members or were giving help to the IRA. At other times, attacks on Catholic civilians were claimed as "retaliation" for IRA actions, since the IRA drew almost all of its support from the Catholic community. Such retaliation was seen as both collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member of that group, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends and neighbors of the perpetrator. Because ind ...

and an attempt to weaken the IRA's support; it was thought that terrorising the Catholic community and inflicting such a death toll on it would force the IRA to end its campaign. Many retaliatory attacks on Catholics were claimed using the covername "Protestant Action Force

The name Protestant Action Force (PAF) was used by Ulster loyalism, loyalists, especially members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), to claim responsibility for a number of paramilitary attacks during the Troubles. It was first used in this ...

" (PAF), which first appeared in autumn 1974.Steve Bruce, ''The Red Hand'', Oxford University Press, 1992, p. 119 They always signed their statements with the fictitious name "Captain William Johnston".

Like the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

(UDA), the UVF's '' modus operandi'' involved assassinations, mass shootings, bombings and kidnappings. It used submachine gun

A submachine gun (SMG) is a magazine-fed, automatic carbine designed to fire handgun cartridges. The term "submachine gun" was coined by John T. Thompson, the inventor of the Thompson submachine gun, to describe its design concept as an autom ...

s, assault rifles, shotgun

A shotgun (also known as a scattergun, or historically as a fowling piece) is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed to shoot a straight-walled cartridge (firearms), cartridge known as a shotshell, which usually discharges numerous small p ...

s, pistols, grenades (including homemade grenades), incendiary bomb

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, t ...

s, booby trap

A booby trap is a device or setup that is intended to kill, harm or surprise a human or another animal. It is triggered by the presence or actions of the victim and sometimes has some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. The trap m ...

bombs and car bombs. Referring to its activity in the early and mid-1970s, journalist Ed Moloney

Edmund "Ed" Moloney (born 1948–9) is an Irish journalist and author best known for his coverage of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and the activities of the Provisional IRA, in particular.

He worked for the ''Hibernia'' magazine and ''Magill ...

described no-warning pub

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

bombings as the UVF's "forte".Moloney, Ed (2010). ''Voices From the Grave: Two Men's War in Ireland''. Faber & Faber. p. 350 Members were trained in bomb-making, and the organisation developed home-made explosives.Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald, ''UVF'', Poolbeg, 1997, p. 105 In the late summer and autumn of 1973, the UVF detonated more bombs than the UDA and IRA combined,Steve Bruce, ''The Red Hand'', Oxford University Press, 1992, p. 115 and by the time of the group's temporary ceasefire in late November it had been responsible for over 200 explosions that year.Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald, ''UVF'', Poolbeg, 1997, p. 129 However, from 1977 bombs largely disappeared from the UVF's arsenal owing to a lack of explosives and bomb-makers, plus a conscious decision to abandon their use in favour of more contained methods.Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald, ''UVF'', Poolbeg, 1997, p. 194Steve Bruce, ''The Red Hand'', Oxford University Press, 1992, p.144–145 The UVF did not return to regular bombings until the early 1990s when it obtained a quantity of the mining explosive Powergel.Jim Cusack & Henry McDonald, ''UVF'', Poolbeg, 1997, pp. 311–312, 313, 316, 317

Strength, finance and support

The strength of the UVF is uncertain. The firstIndependent Monitoring Commission