Ulster Rugby Matches on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label=

Ulster has a population of just over 2 million people and an area of . About 62% of the area of Ulster is in the UK while the remaining 38% is in the Republic of Ireland. Ulster's biggest city, Belfast, has an urban population of over half a million inhabitants, making it the second-largest city on the island of Ireland and the 10th largest urban area in the UK.

Six of Ulster's nine counties, Antrim,

Ulster has a population of just over 2 million people and an area of . About 62% of the area of Ulster is in the UK while the remaining 38% is in the Republic of Ireland. Ulster's biggest city, Belfast, has an urban population of over half a million inhabitants, making it the second-largest city on the island of Ireland and the 10th largest urban area in the UK.

Six of Ulster's nine counties, Antrim,

File:House through the Arch.jpg, At White Park Bay

File:Countryside west of Ballynahinch - geograph.org.uk - 466768.jpg, Countryside west of Ballynahinch

File:Mourne country cottage. - geograph.org.uk - 495183.jpg, Mourne country cottage

File:Fintown Railway on trackbed of CDR County Donegal Railway, Lough Finn (5951398952).jpg, The track of the County Donegal Railways Joint Committee (CDRJC) restored next to Lough Finn, near Fintown station.

File:The approach of autumn, Tardree forest - geograph.org.uk - 943055.jpg, The approach of autumn, Tardree forest

Census 2001 Output

and 4.7% could "speak, read, write and understand" Irish. Large parts of County Donegal are Gaeltacht areas where Irish is the first language and some people in west Belfast also speak Irish, especially in the "Gaeltacht Quarter". The dialect of Irish most commonly spoken in Ulster (especially throughout Northern Ireland and County Donegal) is ' or Donegal Irish, also known as ' or Ulster Irish. Donegal Irish has many similarities to Scottish Gaelic. Polish is the third most common language. Ulster Scots dialects, sometimes known by the neologism ''Ullans'', are also spoken in Counties Down, Antrim, Londonderry and Donegal.

Domnall Ua Lochlainn (died 1121) and Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn (died 1166) were of this dynasty. The Meic Lochlainn were in 1241 overthrown by their kin, the clan Ó Néill (see

Domnall Ua Lochlainn (died 1121) and Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn (died 1166) were of this dynasty. The Meic Lochlainn were in 1241 overthrown by their kin, the clan Ó Néill (see

The Plantation of Ulster continued well into the 18th century, interrupted only by the

The Plantation of Ulster continued well into the 18th century, interrupted only by the

In the 19th century, Ulster had the only large-scale industrialisation and became the most prosperous province on the island. In the latter part of the century, Belfast briefly overtook Dublin as the island's largest city. Belfast became famous in this period for its huge dockyards and shipbuilding – and notably for the construction of the RMS ''Titanic''.

In the 19th century, Ulster had the only large-scale industrialisation and became the most prosperous province on the island. In the latter part of the century, Belfast briefly overtook Dublin as the island's largest city. Belfast became famous in this period for its huge dockyards and shipbuilding – and notably for the construction of the RMS ''Titanic''.  Thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and

Thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and

Census 2011 – Ulster Irish language stats

* The cases of "Protestant Ulster" and Cornwall, by Professor Philip Payton * {{Authority control Divided regions Provinces of Ireland

Ulster Scots Ulster Scots, may refer to:

* Ulster Scots people

* Ulster Scots dialect

Ulster Scots or Ulster-Scots (', ga, Albainis Uladh), also known as Ulster Scotch and Ullans, is the dialect of Scots language, Scots spoken in parts of Ulster in North ...

, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); the remaining three are in the Republic of Ireland.

It is the second-largest (after Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

) and second-most populous (after Leinster) of Ireland's four traditional provinces, with Belfast being its biggest city. Unlike the other provinces, Ulster has a high percentage of Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, making up almost half of its population. English is the main language and Ulster English the main dialect. A minority also speak Irish, and there are Gaeltachtaí (Irish-speaking regions) in southern County Londonderry

County Londonderry ( Ulster-Scots: ''Coontie Lunnonderrie''), also known as County Derry ( ga, Contae Dhoire), is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the thirty two counties of Ireland and one of the nine counties of Ulster. B ...

, the Gaeltacht Quarter, Belfast, and in County Donegal; collectively, these three regions are home to a quarter of the total Gaeltacht population of Ireland. Ulster-Scots Ulster Scots, may refer to:

* Ulster Scots people

The Ulster Scots ( Ulster-Scots: ''Ulstèr-Scotch''; ga, Albanaigh Ultach), also called Ulster Scots people (''Ulstèr-Scotch fowk'') or (in North America) Scotch-Irish (''Scotch-Airisch'') ...

is also spoken. Lough Neagh

Lough Neagh ( ) is a freshwater lake in Northern Ireland and is the largest lake in the island of Ireland, the United Kingdom and the British Isles. It has a surface area of and supplies 40% of Northern Ireland's water. Its main inflows come ...

, in the east, is the largest lake in the British Isles, while Lough Erne

Lough Erne ( , ) is the name of two connected lakes in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is the second-biggest lake system in Northern Ireland and Ulster, and the fourth biggest in Ireland. The lakes are widened sections of the River Erne, ...

in the west is one of its largest lake networks. The main mountain ranges are the Mournes

The Mourne Mountains ( ; ga, Beanna Boirche), also called the Mournes or Mountains of Mourne, are a granite mountain range in County Down in the south-east of Northern Ireland. They include the highest mountains in Northern Ireland, the high ...

, Sperrins, Croaghgorms and Derryveagh Mountains.

Historically, Ulster lay at the heart of the Gaelic world made up of Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans co ...

, Scotland and the Isle of Man. According to tradition, in ancient Ireland it was one of the fifths ( ga, cúige) ruled by a ''rí ruirech

Rí, or commonly ríg ( genitive), is an ancient Gaelic word meaning 'king'. It is used in historical texts referring to the Irish and Scottish kings, and those of similar rank. While the Modern Irish word is exactly the same, in modern Scottis ...

'', or "king of over-kings". It is named after the overkingdom of Ulaid, in the east of the province, which was in turn named after the Ulaid folk. The other overkingdoms in Ulster were Airgíalla

Airgíalla (Modern Irish: Oirialla, English: Oriel, Latin: ''Ergallia'') was a medieval Irish over-kingdom and the collective name for the confederation of tribes that formed it. The confederation consisted of nine minor kingdoms, all independe ...

and Ailech. After the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century, eastern Ulster was conquered by the Anglo-Normans and became the Earldom of Ulster. By the late 14th century the Earldom had collapsed and the O'Neill dynasty

The O'Neill dynasty (Irish: ''Ó Néill'') are a lineage of Irish Gaelic origin, that held prominent positions and titles in Ireland and elsewhere. As kings of Cenél nEógain, they were historically the most prominent family of the Northern ...

had come to dominate most of Ulster, claiming the title King of Ulster. Ulster became the most thoroughly Gaelic and independent of Ireland's provinces. Its rulers resisted English encroachment but were defeated in the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

(1594–1603). King James I then colonised Ulster with English-speaking Protestant settlers from Great Britain, in the Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster ( gle, Plandáil Uladh; Ulster-Scots: ''Plantin o Ulstèr'') was the organised colonisation (''plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the sett ...

. This led to the founding of many of Ulster's towns. The inflow of Protestant settlers and migrants also led to bouts of sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

violence with Catholics, notably during the 1641 rebellion

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantation ...

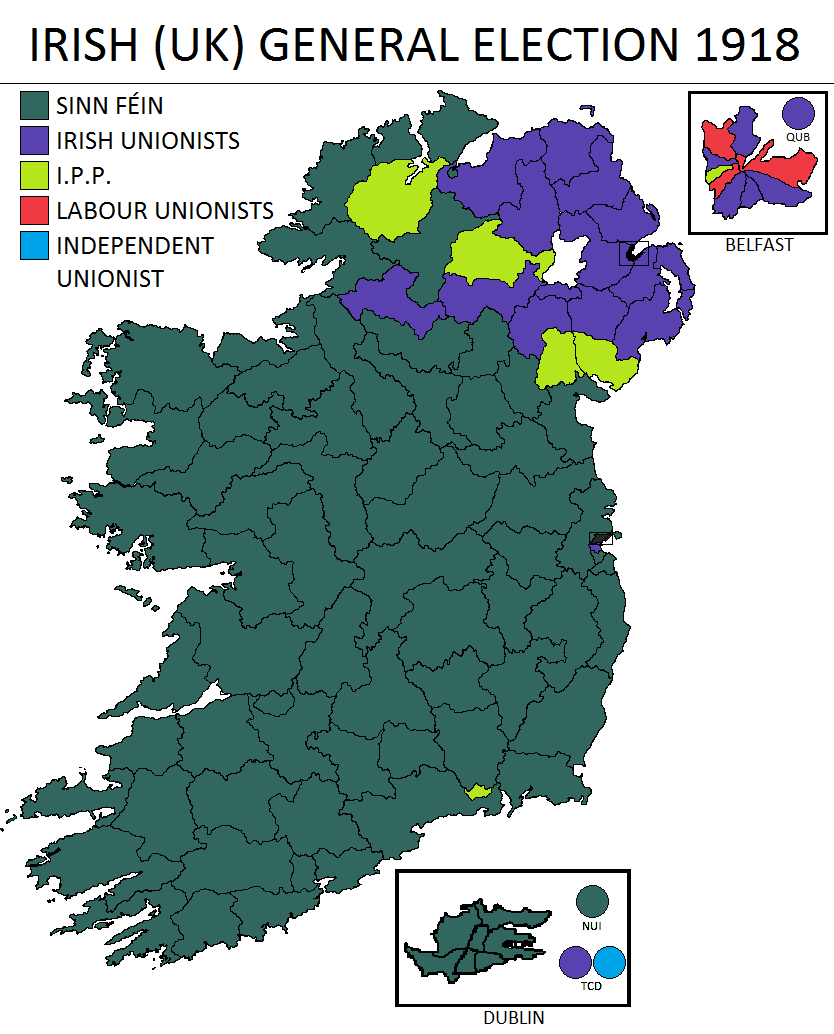

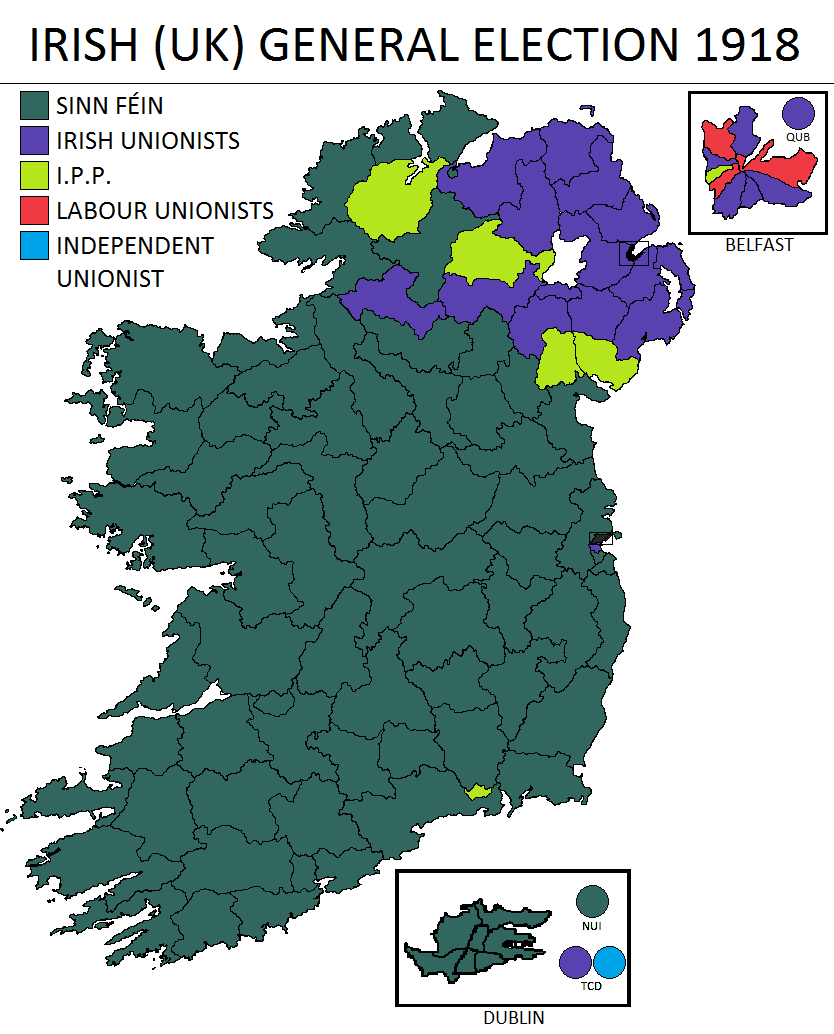

and the Armagh disturbances. Along with the rest of Ireland, Ulster became part of the United Kingdom in 1801. In the early 20th century, moves towards Irish self-rule were opposed by many Ulster Protestants, sparking the Home Rule Crisis. In the last all Ireland election (1918 Irish general election

The 1918 Irish general election was the part of the 1918 United Kingdom general election which took place in Ireland. It is now seen as a key moment in modern Irish history because it saw the overwhelming defeat of the moderate nationalist Iris ...

) counties Donegal and Monaghan returned large Sinn Féin ( nationalist) majorities. Sinn Fein candidates ran unopposed in Cavan. Fermanagh and Tyrone had Sinn Fein/Nationalist Party ( Irish Parliamentary Party) majorities. The other four Counties of Ulster had Unionist Party majorities. The home rule crisis and the subsequent Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

, led to the partition of Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Six Ulster counties became Northern Ireland, a self-governing territory within the United Kingdom, while the rest of Ireland became the Irish Free State, now the Republic of Ireland.

The term ''Ulster'' has no official function for local government purposes in either state. However, for the purposes of ISO 3166-2:IE, ''Ulster'' is used to refer to the three counties of Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan only, which are given country sub-division code "IE-U". The name is also used by various organisations such as cultural and sporting bodies.

Terminology

Ulster's name ultimately derives from the Ulaidh, a group of tribes that once dwelt in this part of Ireland. The Norsemen knew the province as ''Ulaztir'', the '' tír'' or land (a word borrowed from Irish) of the Ulaidh; this was then taken into English as ''Ullister'' or ''Ulvester'', and later contracted to ''Ulster''. Another, less probable explanation is that the suffix -''ster'' represents the Old Norse element '' staðr'' ("place"), found in names like Lybster and Scrabster in Scotland. Ulster is still known as ''Cúige Uladh'' in Irish, meaning the province (literally "fifth") of the Ulaidh. ''Ulaidh'' has historically been anglicised as ''Ulagh'' or ''Ullagh'' and Latinised as ''Ulidia'' or ''Ultonia''. The latter two have yielded the terms ''Ulidian'' and ''Ultonian''. The Irish word for someone or something from Ulster is ''Ultach'', and this can be found in the surnames MacNulty, MacAnulty, and Nulty, which all derive from ''Mac an Ultaigh'', meaning "son of the Ulsterman".Robert Bell; ''The book of Ulster Surnames'', page 180. The Blackstaff Press, 2003. Northern Ireland is often referred to as ''Ulster'', despite including only six of Ulster's nine counties. This usage is most common among people in Northern Ireland who are unionist, although it is also used by the media throughout the United Kingdom. Most Irish nationalists object to the use of Ulster in this context.Geography and political sub-divisions

Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

, Down

Down most often refers to:

* Down, the relative direction opposed to up

* Down (gridiron football), in American/Canadian football, a period when one play takes place

* Down feather, a soft bird feather used in bedding and clothing

* Downland, a ty ...

, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, including the former parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry, form Northern Ireland which remained part of the United Kingdom after the partition of Ireland in 1921. Three Ulster counties – Cavan

Cavan ( ; ) is the county town of County Cavan in Ireland. The town lies in Ulster, near the border with County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. The town is bypassed by the main N3 road that links Dublin (to the south) with Enniskillen, Bally ...

, Donegal Donegal may refer to:

County Donegal, Ireland

* County Donegal, a county in the Republic of Ireland, part of the province of Ulster

* Donegal (town), a town in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland

* Donegal Bay, an inlet in the northwest of Ireland b ...

and Monaghan – form part of the Republic of Ireland. About half of Ulster's population lives in counties Antrim and Down. Across the nine counties, according to the aggregate UK 2011 Census for Northern Ireland, and the ROI 2011 Census for counties Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan, there is a Roman Catholic majority over Protestant of 50.8% to 42.7%.

While the traditional counties continue to demarcate areas of local government in the Republic of Ireland, this is no longer the case in Northern Ireland. Since 1974, the traditional counties have a ceremonial role only. Local government in Northern Ireland is today demarcated by 11 districts.

County-based sub-divisions

Counties shaded in grey are in the Republic of Ireland. Counties shaded in pink are in Northern Ireland.Council-based sub-divisions

Largest settlements

Settlements in Ulster with at least 14,000 inhabitants, listed in order of population: # Belfast (480,000) #Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

(105,000)

# Lisburn

Lisburn (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland. It is southwest of Belfast city centre, on the River Lagan, which forms the boundary between County Antrim and County Down. First laid out in the 17th century by English and Welsh settlers, with ...

(75,000)

# Craigavon (65,000)

# Bangor (58,400)

# Ballymena

Ballymena ( ; from ga, an Baile Meánach , meaning 'the middle townland') is a town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is part of the Borough of Mid and East Antrim.

The town is built on land given to the Adair family by King Charles I i ...

(28,700)

# Newtownards

Newtownards is a town in County Down, Northern Ireland. It lies at the most northern tip of Strangford Lough, 10 miles (16 km) east of Belfast, on the Ards Peninsula. It is in the Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish of Newtownard ...

(27,800)

# Newry (27,400)

# Carrickfergus (27,200)

# Coleraine

Coleraine ( ; from ga, Cúil Rathain , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern I ...

(25,000)

# Antrim (20,000)

# Omagh (19,800)

# Letterkenny (19,600)

# Larne (18,200)

# Banbridge (14,700)

# Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

(14,500)

Economy

The GDP of the province of Ulster is around €50 billion. Salary levels are the lowest on the island of Ireland.Physical geography

The biggest lake in the British Isles,Lough Neagh

Lough Neagh ( ) is a freshwater lake in Northern Ireland and is the largest lake in the island of Ireland, the United Kingdom and the British Isles. It has a surface area of and supplies 40% of Northern Ireland's water. Its main inflows come ...

, lies in eastern Ulster. The province's highest point, Slieve Donard (), stands in County Down. The most northerly point in Ireland, Malin Head, is in County Donegal, as are the sixth-highest () sea cliffs in Europe, at Slieve League, and the province's largest island, Arranmore. The most easterly point in Ireland is also in Ulster, in County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to the ...

, and the most westerly point in the UK is in County Fermanagh. The longest river in the British Isles, the Shannon, rises at the Shannon Pot in County Cavan with underground tributaries from County Fermanagh. Volcanic activity in eastern Ulster led to the formation of the Antrim Plateau and the Giant's Causeway, one of Ireland's three UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Ulster also has a significant drumlin belt. The geographical centre of Ulster lies between the villages of Pomeroy and Carrickmore in County Tyrone. In terms of area, County Donegal is the largest county in all of Ulster.

Transport

Air

The province's main airport isBelfast International Airport

Belfast International Airport is an airport northwest of Belfast in Northern Ireland, is the main airport for the city of Belfast. Until 1983, it was known as ''Aldergrove Airport'', after the nearby village of Aldergrove. In 2018, over 6.2 ...

(popularly called Aldergrove Airport), which is located at Aldergrove, 11.5 miles northwest of Belfast near Antrim. George Best Belfast City Airport (sometimes referred to as "the City Airport" or "the Harbour Airport") is another, smaller airport which is located at Sydenham in Belfast. The City of Derry Airport is located at Eglinton, east of the city of Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

. There is also Donegal Airport ( ga, Aerfort Dhún na nGall), popularly known as Carrickfinn Airport, which is located in The Rosses.

Rail

Railway lines are run by Northern Ireland Railways (NIR). Belfast to Bangor and Belfast to Lisburn are strategically the most important routes on the network with the greatest number of passengers and largest profit margins. The Belfast-Derry railway line connecting Londonderry railway station, viaColeraine

Coleraine ( ; from ga, Cúil Rathain , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern I ...

, Ballymoney, Ballymena

Ballymena ( ; from ga, an Baile Meánach , meaning 'the middle townland') is a town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is part of the Borough of Mid and East Antrim.

The town is built on land given to the Adair family by King Charles I i ...

and Antrim, with Lanyon Place and Belfast Great Victoria Street is a noted scenic route. Belfast is also connected with Carrickfergus and Larne Harbour, Portadown, Newry and onwards, via the Enterprise service jointly operated by NIR and Iarnród Éireann

Iarnród Éireann () or Irish Rail, is the operator of the national railway network of Ireland. Established on 2 February 1987, it is a subsidiary of Córas Iompair Éireann (CIÉ). It operates all internal InterCity, Commuter, DART and fr ...

, to Dublin Connolly.

The main railway lines linking to and from Belfast Great Victoria Street and Belfast Central are:

*The Derry Line and the Portrush Branch

*The Larne Line

*The Bangor Line

*The Portadown Line

Only five Irish counties, all in Southern and Western Ulster, currently have no mainline railway. The historic Great Northern Railway of Ireland

The Great Northern Railway (Ireland) (GNR(I) or GNRI) was an Irish gauge () railway company in Ireland. It was formed in 1876 by a merger of the Irish North Western Railway (INW), Northern Railway of Ireland, and Ulster Railway. The government ...

connected them. They are Cavan, Monaghan, Fermanagh, Tyrone and Donegal. A plan to re-link Sligo

Sligo ( ; ga, Sligeach , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of approximately 20,000 in 2016, it is the List of urban areas ...

and Derry through Donegal has been postponed until at least 2030.

Languages and dialects

Most people in Ulster speak English. English is taught in all schools in the province; Irish (') is taught in all schools in the counties that are part of the Republic, and in schools in Northern Ireland, almost exclusively in the Roman Catholic and Irish-medium sectors. In responses to the 2001 census in Northern Ireland 10% of the population had "some knowledge of Irish"Northern Ireland Statistics and Research AgencCensus 2001 Output

and 4.7% could "speak, read, write and understand" Irish. Large parts of County Donegal are Gaeltacht areas where Irish is the first language and some people in west Belfast also speak Irish, especially in the "Gaeltacht Quarter". The dialect of Irish most commonly spoken in Ulster (especially throughout Northern Ireland and County Donegal) is ' or Donegal Irish, also known as ' or Ulster Irish. Donegal Irish has many similarities to Scottish Gaelic. Polish is the third most common language. Ulster Scots dialects, sometimes known by the neologism ''Ullans'', are also spoken in Counties Down, Antrim, Londonderry and Donegal.

History

Early history

Ulster is one of the four Irish provinces. Itsname

A name is a term used for identification by an external observer. They can identify a class or category of things, or a single thing, either uniquely, or within a given context. The entity identified by a name is called its referent. A personal ...

derives from the Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

''Cúige Uladh'' (), meaning "fifth of the Ulaidh", named for the ancient inhabitants of the region.

The province's early story extends further back than written records and survives mainly in legends such as the Ulster Cycle.

The archaeology of Ulster, formerly called Ulandia, gives examples of "ritual enclosures", such as the Giant's Ring near Belfast, which is an earth bank about 590 feet (180 m) in diameter and 15 feet (4.5 m) high, in the centre of which there is a dolmen

A dolmen () or portal tomb is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the early Neolithic (40003000 BCE) and were somet ...

.

The Boyne and its tributary the Blackwater were the traditional southern boundary of the province of Ulster and appear as such in the Táin Bó Cúailnge. According to historian Francis John Byrne the Ulaid 'possibly still ruled directly in Louth as far as the Boyne in the early seventh century' when Congal Cáech made a bid for the kingship of Tara. In 637, the Battle of Moira, known archaically as the Battle of Magh Rath, was fought by the Gaelic High King of Ireland Domhnall II against his foster son King Congal Cáech of Ulster, supported by his ally Domhnall the Freckled (Domhnall Brecc) of Dalriada. The battle was fought near the Woods of Killultagh, just outside the village of Moira in what would become County Down. It was allegedly the largest battle ever fought on the island of Ireland, and resulted in the death of Congal and the retreat of Domhnall Brecc.

In early medieval Ireland, a branch of the Northern Uí Néill, the Cenél nEógain of the province of Ailech, gradually eroded the territory of the province of Ulaidh until it lay east of the River Bann. The Cenél nEógain would make Tír Eóghain (most of which forms modern County Tyrone) their base. Among the High Kings of Ireland were Áed Findliath (died 879), Niall Glúndub (died 919), and Domnall ua Néill (died 980), all of the Cenél nEógain. The province of Ulaidh would survive restricted to the east of modern Ulster until the Norman invasion in the late 12th century. It would only once more become a province of Ireland in the mid-14th century after the collapse of the Norman Earldom of Ulster, when the O'Neills who had come to dominate the Northern Uí Néill stepped into the power vacuum and staked a claim for the first time the title of "king of Ulster" along with the Red Hand of Ulster symbol. It was then that the provinces of Ailech, Airgialla, and Ulaidh would all merge largely into what would become the modern province of Ulster.

Domnall Ua Lochlainn (died 1121) and Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn (died 1166) were of this dynasty. The Meic Lochlainn were in 1241 overthrown by their kin, the clan Ó Néill (see

Domnall Ua Lochlainn (died 1121) and Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn (died 1166) were of this dynasty. The Meic Lochlainn were in 1241 overthrown by their kin, the clan Ó Néill (see O'Neill dynasty

The O'Neill dynasty (Irish: ''Ó Néill'') are a lineage of Irish Gaelic origin, that held prominent positions and titles in Ireland and elsewhere. As kings of Cenél nEógain, they were historically the most prominent family of the Northern ...

). The Ó Néill's were from then on established as Ulster's most powerful Gaelic family.

The Ó Domhnaill ( O'Donnell) dynasty were Ulster's second most powerful clan from the early thirteenth-century through to the beginning of the seventeenth-century. The O'Donnells ruled over Tír Chonaill (most of modern County Donegal) in West Ulster.

After the Norman invasion

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

of Ireland in the twelfth century, the east of the province fell by conquest to Norman barons, first De Courcy (died 1219), then Hugh de Lacy (1176–1243), who founded the Earldom of Ulster based on the modern counties of Antrim and Down.

In the 1600s Ulster was the last redoubt of the traditional Gaelic way of life, and following the defeat of the Irish forces in the Nine Years War (1594–1603) at the battle of Kinsale (1601), Elizabeth I's English forces succeeded in subjugating Ulster and all of Ireland.

The Gaelic leaders of Ulster, the O'Neills

O'Neills Irish International Sports Company Ltd. is an Irish sporting goods manufacturer established in 1918. It is the largest manufacturer of sportswear in Ireland, with production plants located in Dublin and Strabane.

O'Neills has a long re ...

and O'Donnells, finding their power under English suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

limited, decamped ''en masse'' in 1607 (the Flight of the Earls) to Roman Catholic Europe. This allowed the English Crown

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sax ...

to plant Ulster with more loyal English and Scottish planters, a process which began in earnest in 1610.

Plantations and civil wars

ThePlantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster ( gle, Plandáil Uladh; Ulster-Scots: ''Plantin o Ulstèr'') was the organised colonisation (''plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the sett ...

( gle, Plandáil Uladh) was the organised colonisation (or plantation) of Ulster by people from Great Britain (especially Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

from Scotland). Private plantation by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while the official plantation controlled by King James I of England (who was also King James VI of Scots) began in 1609. All land owned by Irish chieftains, the Ó Neills and Ó Donnells (along with those of their supporters), who fought against the English Crown

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sax ...

in the Nine Years War, were confiscated and used to settle the colonists. The Counties Tyrconnell, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan

Cavan ( ; ) is the county town of County Cavan in Ireland. The town lies in Ulster, near the border with County Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. The town is bypassed by the main N3 road that links Dublin (to the south) with Enniskillen, Bally ...

, Coleraine

Coleraine ( ; from ga, Cúil Rathain , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern I ...

and Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

comprised the official Colony. However, most of the counties, including the most heavily colonised Counties Antrim and Down

Down most often refers to:

* Down, the relative direction opposed to up

* Down (gridiron football), in American/Canadian football, a period when one play takes place

* Down feather, a soft bird feather used in bedding and clothing

* Downland, a ty ...

, were privately colonised. These counties, though not officially designated as subject to Plantation, had suffered violent depopulation during the previous wars and proved attractive to Private Colonialists from nearby Britain. The efforts to attract colonists from England and Scotland to the Ulster Plantation were considerably affected by the existence of British colonies in the Americas, which served as a more attractive destination for many potential emigrants.

The official reason for the Plantation is said to have been to pay for the costly Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

, but this view was not shared by all in the English government of the time, most notably the English Crown

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sax ...

-appointed Attorney-General for Ireland in 1609, Sir John Davies:

The Plantation of Ulster continued well into the 18th century, interrupted only by the

The Plantation of Ulster continued well into the 18th century, interrupted only by the Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantatio ...

. This Rebellion was initially led by Sir Phelim O'Neill (Irish: ''Sir Féilim Ó Néill''), and was intended to overthrow British rule rapidly, but quickly degenerated into attacks on colonists, in which dispossessed Irish slaughtered thousands of the colonists. In the ensuing wars (1641–1653, fought against the background of civil war in England, Scotland and Ireland), Ulster became a battleground between the Colonialists and the native Irish. In 1646, an Irish army under command by Owen Roe O'Neill (Irish: ''Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill'') inflicted a defeat on a Scottish Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

army at Benburb in County Tyrone, but the native Irish forces failed to follow up their victory and the war lapsed into stalemate. The war in Ulster ended with the defeat of the native army at the Battle of Scarrifholis, near Newmills on the western outskirts of Letterkenny, County Donegal, in 1650, as part of the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland wi ...

conducted by Oliver Cromwell and the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

, the aim of which was to expel all native Irish to the Province of Connaught.

Forty years later, in 1688–1691, the Williamite War was fought, the belligerents of which were the Williamites and Jacobites. The war was partly due to a dispute over who was the rightful claimant to the British Throne, and thus the supreme monarch of the nascent British Empire. However, the war was also a part of the greater War of the Grand Alliance, fought between King Louis XIV of France and his allies, and a European-wide coalition, the Grand Alliance, led by Prince William of Orange

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic fro ...

and Emperor Leopold I of the Holy Roman Empire, supported by the Vatican and many other states. The Grand Alliance was a cross-denominational alliance designed to stop French eastward colonialist expansion under Louis XIV, with whom King James II was allied.

The majority of Irish people were "Jacobites" and supported James II due to his 1687 Declaration of Indulgence or, as it is also known, The Declaration for the Liberty of Conscience, that granted religious freedom to all denominations in England and Scotland and also due to James II's promise to the Irish Parliament of an eventual right to self-determination. However, James II was deposed in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

, and the majority of Ulster Colonialists ( Williamites) backed William of Orange. It is of note that both the Williamite and Jacobite armies were religiously mixed; William of Orange's own elite forces, the Dutch Blue Guards had a papal banner with them during the invasion, many of them being Dutch Roman Catholics.

At the start of the war, Irish Jacobites controlled most of Ireland for James II, with the exception of the Williamite strongholds at Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

and at Enniskillen in Ulster. The Jacobites besieged Derry from December 1688 to July 1689, ending when a Williamite army from Britain relieved the city. The Williamites based in Enniskillen defeated another Jacobite army at the battle of Newtownbutler on 28 July 1689. Thereafter, Ulster remained firmly under Williamite control and William's forces completed their conquest of the rest of Ireland in the next two years. The war provided Protestant loyalists with the iconic victories of the Siege of Derry, the Battle of the Boyne (1 July 1690) and the Battle of Aughrim (12 July 1691), all of which the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

commemorate each year.

The Williamites' victory in this war ensured British rule in Ireland

British rule in Ireland spanned several centuries and involved British control of parts, or entirety, of the island of Ireland. British involvement in Ireland began with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. Most of Ireland gained indepen ...

for over 200 years. The Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland excluded most of Ulster's population from having any Civil power on religious grounds. Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

(descended from the indigenous Irish) and Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

(mainly descended from Scottish colonists) both suffered discrimination under the Penal Laws, which gave full political rights only to Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

Protestants (mostly descended from English settlers). In the 1690s, Scottish Presbyterians became a majority in Ulster, due to a large influx of them into the Province.

Emigration

Considerable numbers of Ulster-Scots emigrated to the North American colonies throughout the 18th century (160,000 settled in what would become the United States between 1717 and 1770 alone). Disdaining (or forced out of) the heavily English regions on the Atlantic coast, most groups of Ulster-Scots settlers crossed into the "western mountains," where their descendants populated the Appalachian regions and the Ohio Valley. Here they lived on the frontiers of America, carving their own world out of the wilderness. The Scots-Irish soon became the dominant culture of the Appalachians from Pennsylvania to Georgia. Author (and US Senator) Jim Webb puts forth a thesis in his book ''Born Fighting'' to suggest that the character traits he ascribes to the Scots-Irish such as loyalty to kin, mistrust of governmental authority, and a propensity to bear arms, helped shape the American identity. In the United States Census, 2000, 4.3 million Americans claimed Scots-Irish ancestry. The areas where the most Americans reported themselves in the 2000 Census only as "American" with no further qualification (e.g. Kentucky, north-central Texas, and many other areas in the Southern US) are largely the areas where many Scots-Irish settled, and are in complementary distribution with the areas which most heavily report Scots-Irish ancestry. According to the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, 400,000 people in the US were of Irish birth or ancestry in 1790 when the first US Census counted 3,100,000 white Americans. According to the encyclopaedia, half of these Irish Americans were descended from Ulster, and half from the other three provinces of Ireland.Republicanism, rebellion and communal strife

Most of the 18th century saw a calming of sectarian tensions in Ulster. The economy of the province improved, as small producers exported linen and other goods. Belfast developed from a village into a bustling provincial town. However, this did not stop many thousands of Ulster people from emigrating to British North America in this period, where they became known as " Scots Irish" or " Scotch-Irish". Political tensions resurfaced, albeit in a new form, towards the end of the 18th century. In the 1790s many Roman Catholics andPresbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, in opposition to Anglican domination and inspired by the American and French revolutions joined in the United Irishmen movement. This group (founded in Belfast) dedicated itself to founding a non-sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

and independent Irish republic. The United Irishmen had particular strength in Belfast, Antrim and Down

Down most often refers to:

* Down, the relative direction opposed to up

* Down (gridiron football), in American/Canadian football, a period when one play takes place

* Down feather, a soft bird feather used in bedding and clothing

* Downland, a ty ...

. Paradoxically however, this period also saw much sectarian violence between Roman Catholics and Protestants, principally members of the Church of Ireland (Anglicans, who practised the British state religion and had rights denied to both Presbyterians and Roman Catholics), notably the " Battle of the Diamond" in 1795, a faction fight between the rival " Defenders" (Roman Catholic) and "Peep O'Day Boys

The Peep o' Day Boys was an agrarian Protestant association in 18th-century Ireland. Originally noted as being an agrarian society around 1779–80, from 1785 it became the Protestant component of the sectarian conflict that emerged in County Arm ...

" (Anglican), which led to over 100 deaths and to the founding of the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

. This event, and many others like it, came about with the relaxation of the Penal Laws and Roman Catholics began to be allowed to purchase land and involve themselves in the linen trade (activities which previously had involved many onerous restrictions). Protestants, including some Presbyterians, who in some parts of the province had come to identify with the Roman Catholic community, used violence to intimidate Roman Catholics who tried to enter the linen trade. Estimates suggest that up to 7000 Roman Catholics suffered expulsion from Ulster during this violence. Many of them settled in northern Connacht. These refugees' linguistic influence still survives in the dialects of Irish spoken in Mayo, which have many similarities to Ulster Irish not found elsewhere in Connacht. Loyalist militias, primarily Anglicans, also used violence against the United Irishmen and against Roman Catholic and Protestant republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

throughout the province.

In 1798 the United Irishmen, led by Henry Joy McCracken, launched a rebellion in Ulster, mostly supported by Presbyterians. But the British authorities swiftly put down the rebellion and employed severe repression after the fighting had ended. In the wake of the failure of this rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

, and following the gradual abolition of official religious discrimination after the Act of Union in 1800, Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

came to identify more with the State and with their Anglican neighbours, due to their civil rights now being respected by both the state and their Anglican neighbours.

The 1859 Ulster Revival

The 1859 Ulster revival was a Christian revival in Ulster which spread to the rest of the United Kingdom. It has been reported that the revival produced 100,000 converts.

The revival began in Kells and Connor in County Antrim. In late 1857, thro ...

was a major Christian revival

Christian revivalism is increased spiritual interest or renewal in the life of a church congregation or society, with a local, national or global effect. This should be distinguished from the use of the term "revival" to refer to an evangelis ...

that spread throughout Ulster.

Industrialisation, Home Rule and partition

In the 19th century, Ulster had the only large-scale industrialisation and became the most prosperous province on the island. In the latter part of the century, Belfast briefly overtook Dublin as the island's largest city. Belfast became famous in this period for its huge dockyards and shipbuilding – and notably for the construction of the RMS ''Titanic''.

In the 19th century, Ulster had the only large-scale industrialisation and became the most prosperous province on the island. In the latter part of the century, Belfast briefly overtook Dublin as the island's largest city. Belfast became famous in this period for its huge dockyards and shipbuilding – and notably for the construction of the RMS ''Titanic''. Sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

divisions in Ulster became hardened into the political categories of '' unionist'' (supporters of the Union with Britain; mostly, but not exclusively, Protestant) and '' nationalist'' (advocates of repeal of the 1800 Act of Union, usually, though not exclusively, Roman Catholic). Northern Ireland's current politics originate from these late 19th century disputes over Home Rule that would have devolved some powers of government to Ireland, and which Ulster Protestants usually opposed—fearing for their religious rights calling it "Rome Rule" in an autonomous Roman Catholic-dominated Ireland and also not trusting politicians from the agrarian south and west to support the more industrial economy of Ulster. This lack of trust, however, was largely unfounded as during the 19th and early 20th century important industries in the southernmost region of Cork included brewing, distilling, wool and like Belfast, shipbuilding.

Thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and

Thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and James Craig James or Jim Craig may refer to:

Entertainment

* James Humbert Craig (1877–1944), Irish painter

* James Craig (actor) (1912–1985), American actor

* James Craig (''General Hospital''), fictional character on television, a.k.a. Jerry Jacks

* ...

, signed the " Ulster Covenant" of 1912 pledging to resist Home Rule. This movement also set up the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). In April 1914, the UVF assisted with the landing of 30,000 German rifles with 3,000,000 rounds at Larne by blockading authorities. (See Larne gunrunning

The Larne gun-running was a major gun smuggling operation organised in April 1914 in Ireland by Major Frederick H. Crawford and Captain Wilfrid Spender for the Ulster Unionist Council to equip the Ulster Volunteer Force. The operation involved t ...

). The Curragh Incident showed it would be difficult to use the British army to enforce home rule from Dublin on Ulster's unionist minority.

In response, Irish republicans created the Irish Volunteers, part of which became the forerunner of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) – to seek to ensure the passing of the Home Rule Bill

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

. Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, 200,000 Irishmen, both Southern and Northern, of all religious sects volunteered to serve in the British Army. This had the effect of interrupting the armed stand-off in Ireland. As the war progressed, in Ireland, opposition to the War grew stronger, reaching its peak in 1918 when the British government proposed laws to extend conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

to all able bodied Irishmen during the Conscription Crisis.

In the aftermath of World War I, the political party Sinn Féin ("Ourselves") won the majority of votes in the 1918 Irish general election

The 1918 Irish general election was the part of the 1918 United Kingdom general election which took place in Ireland. It is now seen as a key moment in modern Irish history because it saw the overwhelming defeat of the moderate nationalist Iris ...

, this political party pursued a policy of complete independent self-determination for the island of Ireland as outlined in the Sinn Féin campaign Manifesto of 1918, a great deal more than the devolved government/ Home Rule advocated by the (I.P.P) Irish Parliamentary Party. Following the Sinn Féin victory in these elections the Irish Declaration of Independence was penned and Irish republicans

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

launched a guerrilla campaign against British rule in what became the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

(January 1919 – July 1921). The fighting in Ulster during the Irish War of Independence generally took the form of street battles between Protestants and Roman Catholics in the city of Belfast. Estimates suggest that about 600 civilians died in this communal violence, the majority of them (58%) Roman Catholics (see The Troubles (1920–1922)

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an Ethnic nationalism, ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometime ...

). The IRA remained relatively quiescent in Ulster, with the exception of the south Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

area, where Frank Aiken led it. A lot of IRA activity also took place at this time in County Donegal and the City of Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

, where one of the main Republican leaders was Peadar O'Donnell. Hugh O'Doherty, a Sinn Féin politician, was elected mayor of Derry at this time. In the First Dáil, which was elected in late 1918, Prof. Eoin Mac Néill served as the Sinn Féin T.D. for Londonderry City.

1920 to present

Partition of Ireland, first mooted in 1912, was introduced with the enactment of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which gave a form of "Home rule" self-government to two areas, Southern Ireland, with its capital at Dublin, and " Northern Ireland", consisting of six of Ulster's central and eastern counties, both within a continuing United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Dissatisfaction with this led to theIrish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

, which formally ceased on 11 July 1921. Low-level violence, however, continued in Ulster, causing Michael Collins in the south to order a boycott of Northern products in protest at attacks on the Nationalist community there. The Partition was effectively confirmed by the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921. One of the primary stipulations of the treaty was the transformation of Ireland into a self-governing British dominion called the Irish Free State (which later became the sovereign Republic of Ireland), but with the option of a continuation of the home rule institution of Northern Ireland, still within the United Kingdom, if the Northern Ireland Parliament (already in existence) chose to opt out of the Irish Free State. All parties knew that this was certain to be the choice of the Ulster Unionists who had a majority in the parliament, and immediately on the creation of the Free State they resolved to leave it.

Following the Anglo Irish treaty, the exact border between the new dominion of the Irish Free State and the future Northern Ireland, if it chose to opt out, was to be decided by the Irish Boundary Commission

The Irish Boundary Commission () met in 1924–25 to decide on the precise delineation of the border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, which ended the Irish War of Independence, provided for such a c ...

. This did not announce its findings until 1925, when the line was again drawn around six of Ulster's nine counties, with no change from the partition of 1920.

Electorally, voting in the six Northern Ireland counties of Ulster tends to follow religious or sectarian lines; noticeable religious demarcation does not exist in the South Ulster counties of Cavan and Monaghan in the Republic of Ireland. County Donegal is largely a Roman Catholic county, but with a large Protestant minority. Generally, Protestants in Donegal vote for the political party Fine Gael ("Family of the Irish"). However, religious sectarianism in politics has largely disappeared from the rest of the Republic of Ireland. This was illustrated when Erskine H. Childers, a Church of Ireland member and Teachta Dála (TD, a member of the lower house of the National Parliament) who had represented Monaghan, won election as President after having served as a long-term minister under Fianna Fáil Taoisigh

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legislature) and the office ...

Éamon de Valera, Seán Lemass and Jack Lynch

John Mary Lynch (15 August 1917 – 20 October 1999) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1966 to 1973 and 1977 to 1979, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 to 1979, Leader of the Opposition from 1973 to 1977, Minister ...

.

The Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

freely organises in counties Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan, with several Orange parades taking place throughout County Donegal each year. The only major Orange Order march in the Republic of Ireland takes place every July in the village of Rossnowlagh, near Ballyshannon, in the south of County Donegal.

, Northern Ireland has seven Roman Catholic members of parliament, all members of Sinn Féin (of a total of 18 from the whole of Northern Ireland) in the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

at Westminster; and the other three counties have one Protestant T.D. of the ten it has elected to Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

, the Lower House of the Oireachtas, the parliament of the Republic of Ireland. At present (August 2007) County Donegal sends six T.D.'s to Dáil Éireann. The county is divided into two constituencies: Donegal North-East and Donegal South-West, each with three T.D.'s. County Cavan and County Monaghan form the one constituency called Cavan-Monaghan, which sends five T.D.'s to the Dáil (one of whom is a Protestant).

The historic Flag of Ulster served as the basis for the Ulster Banner (often referred to as the Flag of Northern Ireland), which was the flag of the Government of Northern Ireland until the proroguing of the Stormont parliament in 1973.

Wildlife

William Sherard (1659–1728) was the first biologist in Ulster.Sport

InGaelic games

Gaelic games ( ga, Cluichí Gaelacha) are a set of sports played worldwide, though they are particularly popular in Ireland, where they originated. They include Gaelic football, hurling, Gaelic handball and rounders. Football and hurling, the ...

(which include Gaelic football

Gaelic football ( ga, Peil Ghaelach; short name '), commonly known as simply Gaelic, GAA or Football is an Irish team sport. It is played between two teams of 15 players on a rectangular grass pitch. The objective of the sport is to score by kic ...

and hurling

Hurling ( ga, iománaíocht, ') is an outdoor team game of ancient Gaelic Irish origin, played by men. One of Ireland's native Gaelic games, it shares a number of features with Gaelic football, such as the field and goals, the number of p ...

), Ulster counties play the Ulster Senior Football Championship and Ulster Senior Hurling Championship. In football, the main competitions in which they compete with the other Irish counties are the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship and National Football League, while the Ulster club champions represent the province in the All-Ireland Senior Club Football Championship. Hurling teams play in the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship

The GAA Hurling All-Ireland Senior Championship, known simply as the All-Ireland Championship, is an annual inter-county hurling competition organised by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). It is the highest inter-county hurling competition i ...

, National Hurling League

The National Hurling League is an annual Inter county, inter-county hurling competition featuring teams from Ireland and England. Founded in 1925 by the Gaelic Athletic Association, it operates on a system of promotion and relegation within the l ...

and All-Ireland Senior Club Hurling Championship. The whole province fields a team to play the other provinces in the Railway Cup

The GAA Interprovincial Championship ( ga, An Corn Idir-Chúigeach) or Railway Cup (''Corn an Iarnróid'') is the name of two annual Gaelic football and hurling competitions held between the provinces of Ireland. The Connacht, Leinster, Munster ...

in both football and hurling. Gaelic Football is by far the most popular of the GAA sports in Ulster but hurling is also played, especially in Antrim, Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

, Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

, and Down

Down most often refers to:

* Down, the relative direction opposed to up

* Down (gridiron football), in American/Canadian football, a period when one play takes place

* Down feather, a soft bird feather used in bedding and clothing

* Downland, a ty ...

.

The border has divided association football teams since 1921. The Irish Football Association (the I.F.A.) oversees the sport in N.I., while the Football Association of Ireland (the F.A.I.) oversees the sport in the Republic. As a result, separate international teams are fielded and separate championships take place ( Irish Football League in Northern Ireland, League of Ireland in the rest of Ulster and Ireland). Anomalously, Derry City F.C. has played in the League of Ireland since 1985 due to crowd trouble at some of their Irish League matches prior to this. The other major Ulster team in the League of Ireland is Finn Harps of Ballybofey, County Donegal. When Derry City F.C. and Finn Harps play against each other, the game is usually referred to as a 'North-West Derby'. There have been cup competitions between I.F.A. and F.A.I. clubs, most recently the Setanta Sports Cup

The Setanta Sports Cup was a club football competition featuring teams from both football associations on the island of Ireland. Inaugurated in 2005, it was a cross-border competition between clubs in the League of Ireland from the Republic of ...

.

In Rugby union, the professional rugby team representing the province and the IRFU Ulster Branch, Ulster Rugby, compete in the Pro14 along with teams from Wales, Scotland, Italy, South Africa and the other Irish Provinces ( Leinster, Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

and Connacht). They also compete in Europe's main club rugby tournament, the European Rugby Champions Cup, which they won (as the Heineken Cup) back in 1999. Notable Ulster rugby players include Willy John McBride, Jack Kyle and Mike Gibson. The former is the most capped British and Irish Lion

The British & Irish Lions is a rugby union team selected from players eligible for the national teams of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. The Lions are a test side and most often select players who have already played for their national ...

of all time, having completed four tours with the Lions in the sixties and seventies. At international level players from Ulster join with those from the other 3 provinces to form the Irish national team. They do not sing the Irish national anthem but do sing a special song which has been written celebrating the "4 proud provinces" before matches start.

The Ulster Hockey Union organises field hockey in the province and contributes substantially to the all-island hockey team.

Cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

is also played in Ulster, especially in Northern Ireland and East Donegal. Ulster enters two teams into the Interprovincial Series; the North Knights and the North West Warriors, who are the respective representative teams of the Northern Cricket Union (NCU) and the North West Cricket Union

The North West of Ireland Cricket Union, often referred to as the North West Cricket Union, is one of five provincial governing bodies in Ireland. Along with the Connacht, Leinster, Munster and Northern unions, it makes up the Irish Cricket Uni ...

(NWCU).

Golf is, however, by far the most high-profile sport and the sport that Ulster has succeeded at more than any other. Ulster has produced many great players over the years, from Fred Daly winning The Open Championship in 1947 at the Royal Liverpool Golf Club, Hoylake to most recently Rory McIlroy

Rory Daniel McIlroy (born 4 May 1989) is a professional golfer from Northern Ireland who is a member of both the European and PGA Tours. He is the current world number one in the Official World Golf Ranking, and has spent over 100 weeks in tha ...

winning the US Open and Darren Clarke winning The Open Championship in 2011. Ulster also has another Major winner in Graeme McDowell, who also won the US Open in 2010. The Open Championship returned to Ulster, after 68 years, in 2019 at Royal Portrush Golf Club.

In horse racing, specifically National Hunt, Ulster has produced the most dominant jockey of all time, Tony McCoy.

The Circuit of Ireland Rally is an annual automobile rally held in Ulster since 1931.

See also

* Culture of Ulster * Kings of Ulster * List of Ulster-related topics * Red Hand of Ulster *Ulidia (kingdom)

Ulaid (Old Irish, ) or Ulaidh (Modern Irish, ) was a Gaelic over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups. Alternative names include Ulidia, which is the Latin form of Ulaid, and in ...

* Ulster nationalism

* Ulster-Scots people

Notes

References

* Deane, C. Douglas (1983). ''The Ulster Countryside''. Century Books. .Further reading

* Braidwood, J. 1964. ''Ulster Dialects, An Introductory Symposium'' Ulster Folk Museum. * Faulkner, J. and Thompson, R. 2011. ''The Natural History of Ulster.'' National Museums of Northern Ireland. Publication No. 026. * Morton, O. 1994. ''Marine Algae of Northern Ireland.'' Ulster Museum, Belfast. *Sheane, Michael. ''Ulster Blood.'' Ilfracombe: Arthur H. Stockwell, 2005. * ''Stewart and Corry's Flora of the North-east of Ireland.'' Third edition. Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen's University of BelfastExternal links

Census 2011 – Ulster Irish language stats

* The cases of "Protestant Ulster" and Cornwall, by Professor Philip Payton * {{Authority control Divided regions Provinces of Ireland