USS Macon (ZRS-5) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Macon'' (ZRS-5) was a rigid

USS ''Macon'' was built at the

USS ''Macon'' was built at the

On 24 June 1933, ''Macon'' left Goodyear's field for Naval Air Station (NAS)

On 24 June 1933, ''Macon'' left Goodyear's field for Naval Air Station (NAS)

airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

built and operated by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

for scouting

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hiking, backpacking ...

and served as a "flying aircraft carrier", designed to carry biplane parasite aircraft

A parasite aircraft is a component of a composite aircraft which is carried aloft and air launched by a larger carrier aircraft or mother ship to support the primary mission of the carrier. The carrier craft may or may not be able to later reco ...

, five single-seat Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk

The Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk is a light 1930s biplane fighter aircraft that was carried by the United States Navy airships and . It is an example of a parasite fighter, a small airplane designed to be deployed from a larger aircraft such as ...

for scouting or two-seat Fleet N2Y-1 for training. In service for less than two years, in 1935 the ''Macon'' was damaged in a storm and lost off California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

's Big Sur

Big Sur () is a rugged and mountainous section of the Central Coast of California between Carmel and San Simeon, where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. It is frequently praised for its dramatic scenery. Big Sur ha ...

coast, though most of the crew were saved. The wreckage is listed as the USS ''Macon'' Airship Remains on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

.

Less than shorter than ''Hindenburg'', both ''Macon'' and her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

were among the largest flying objects in the world in terms of length and volume. Although both of the hydrogen-filled, Zeppelin-built ''Hindenburg'' and LZ 130 ''Graf Zeppelin II'' were longer, the two American-built sister naval airships still hold the world record for helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

-filled rigid airships.

Construction

USS ''Macon'' was built at the

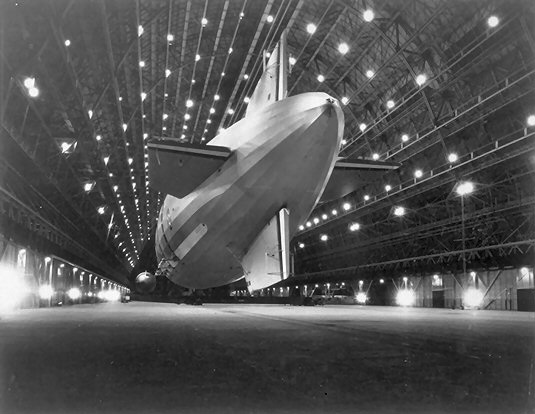

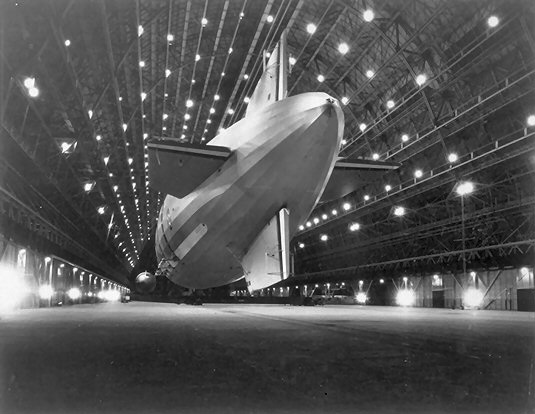

USS ''Macon'' was built at the Goodyear Airdock

The Goodyear Airdock is a construction and storage airship hangar in Akron, Ohio. At its completion in 1929, it was the largest building in the world without interior supports.

Description

The building has a unique shape which has been describe ...

in Springfield Township, Ohio by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation. Because this was by far the biggest airship ever to be built in America, a team of experienced German airship engineers—led by Chief Designer Karl Arnstein

Karl Arnstein (March 24, 1887, Prague – December 12, 1974, Bryan, Ohio) was one of the most important 20th century airship engineers and designers in Germany and the United States of America. He was born in Prague, Bohemia (now the Czech Repub ...

—instructed and supported design and construction of both the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

airships ''Akron'' and ''Macon''.

''Macon'' had a structured duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age-hardenable aluminium alloys. The term is a combination of '' Dürener'' and ''aluminium''.

Its use as a tra ...

um hull with three interior keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

s. The airship was kept aloft by 12 helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

-filled gas cells made from gelatin

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

-latex

Latex is an emulsion (stable dispersion) of polymer microparticles in water. Latexes are found in nature, but synthetic latexes are common as well.

In nature, latex is found as a milky fluid found in 10% of all flowering plants (angiosperms ...

fabric. Inside the hull, the ship had eight German-made Maybach VL II

The Maybach VL II was a type of internal combustion engine built by the German company Maybach in the late 1920s and 1930s. It was an uprated development of the successful Maybach VL I, and like the VL I, was a 60° V-12 engine.

Five of them powe ...

12-cylinder

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infin ...

, gasoline-powered engines that drove outside propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

s. The propellers could be rotated down or backwards, providing an early form of thrust vectoring

Thrust vectoring, also known as thrust vector control (TVC), is the ability of an aircraft, rocket, or other vehicle to manipulate the direction of the thrust from its engine(s) or motor(s) to control the attitude or angular velocity of the v ...

to control the ship during takeoff and landings. The rows of slots in the hull above each engine were part of a system to condense out the water vapor from the engine exhaust gases for use as buoyancy compensation ballast to compensate for the loss of weight as fuel was consumed.

Service history

Christening and commissioning

''Macon'' was christened on 11 March 1933, by Jeanette Whitton Moffett, wife ofRear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

William A. Moffett

William Adger Moffett (October 31, 1869 – April 4, 1933) was an American admiral and Medal of Honor recipient known as the architect of naval aviation in the United States Navy.

Biography

Born October 31, 1869 in Charleston, South Carolina, ...

, Chief of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics

The Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) was the U.S. Navy's material-support organization for naval aviation from 1921 to 1959. The bureau had "cognizance" (''i.e.'', responsibility) for the design, procurement, and support of naval aircraft and relate ...

. The airship was named after the city of Macon, Georgia

Macon ( ), officially Macon–Bibb County, is a consolidated city-county in the U.S. state of Georgia. Situated near the fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is located southeast of Atlanta and lies near the geographic center of the state of Geo ...

, which was the largest city in the Congressional district

Congressional districts, also known as electoral districts and legislative districts, electorates, or wards in other nations, are divisions of a larger administrative region that represent the population of a region in the larger congressional bod ...

of Carl Vinson

Carl Vinson (November 18, 1883 – June 1, 1981) was an American politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives for over 50 years and was influential in the 20th century expansion of the U.S. Navy. He was a member of the Democratic ...

, then the chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

' Committee on Naval Affairs.

The airship first flew on 21 April, aloft over northern Ohio for nearly 13 hours with 105 aboard, just over a fortnight after the loss of ''Akron'' in which Admiral Moffett and 72 others were killed. ''Macon'' was commissioned into the U.S. Navy on 23 June 1933, with Commander Alger H. Dresel in command.

1933

On 24 June 1933, ''Macon'' left Goodyear's field for Naval Air Station (NAS)

On 24 June 1933, ''Macon'' left Goodyear's field for Naval Air Station (NAS) Lakehurst, New Jersey

Lakehurst is a borough in Ocean County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the borough's population was 2,654,

File:N2Y-1_USS_Macon_hangar_NAN9-75.jpg, Inside ''Macon''s aircraft hangar

File:F9C-2_Sparrowhawk_fighter.jpg,  ''Macon'' first operated aircraft on 6 July 1933 during trial flights out of Lakehurst, New Jersey. The planes were stored in bays inside the hull and were launched and retrieved using a

''Macon'' first operated aircraft on 6 July 1933 during trial flights out of Lakehurst, New Jersey. The planes were stored in bays inside the hull and were launched and retrieved using a

On 20 April 1934, the ''Macon'' left Sunnyvale for a challenging cross-continent flight east to

On 20 April 1934, the ''Macon'' left Sunnyvale for a challenging cross-continent flight east to

The

The

Airships.net: USS ''Akron'' and ''Macon''

A 1964 KPIX-TV documentary about the U.S.S. ''Macon''

* ttp://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,441035,00.html Uncovering the USS ''Macon'': The Underwater Airship ''Der Spiegel''

Construction of the USS ''Macon'' Airship

(photo gallery) * KQED has put togethe

a video

with info about USS ''Macon'', historical and wreck-site footage, as well as info about the new zeppelin that is flying over the San Francisco Bay Area.

Moffett Field Museum

near San Jose, California has an exhibit dedicated to the USS ''Macon''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Macon (Zrs-5) Airborne aircraft carriers USS 1933 ships 1935 in aviation Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1935 Accidents and incidents involving balloons and airships 1935 in California 1930s United States aircraft Transportation on the National Register of Historic Places in California Goodyear aircraft Akron-class airships National Register of Historic Places in Monterey County, California Big Sur Aircraft on the National Register of Historic Places Moffett Field

Sparrowhawk

Sparrowhawk (sometimes sparrow hawk) may refer to several species of small hawk in the genus ''Accipiter''. "Sparrow-hawk" or sparhawk originally referred to ''Accipiter nisus'', now called "Eurasian" or "northern" sparrowhawk to distinguish it f ...

scout/fighter aircraft on its exterior rigging

File:USS Macon secondary control station.jpg, Inside ''Macon''s secondary control node

File:USS_Macon_spy_basket_1934.jpg, Aerial reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance is reconnaissance for a military or strategic purpose that is conducted using reconnaissance aircraft. The role of reconnaissance can fulfil a variety of requirements including artillery spotting, the collection of ima ...

"spy car" observer's basket which could be lowered below clouds with a tether.

''Macon'' first operated aircraft on 6 July 1933 during trial flights out of Lakehurst, New Jersey. The planes were stored in bays inside the hull and were launched and retrieved using a

''Macon'' first operated aircraft on 6 July 1933 during trial flights out of Lakehurst, New Jersey. The planes were stored in bays inside the hull and were launched and retrieved using a trapeze

A trapeze is a short horizontal bar hung by ropes or metal straps from a ceiling support. It is an aerial apparatus commonly found in circus performances. Trapeze acts may be static, spinning (rigged from a single point), swinging or flying, an ...

.

The airship left the East Coast on 12 October 1933, on a transcontinental flight to her new permanent homebase at NAS Sunnyvale (now Moffett Federal Airfield

Moffett Federal Airfield , also known as Moffett Field, is a joint civil-military airport located in an unincorporated part of Santa Clara County, California, United States, between northern Mountain View and northern Sunnyvale. On November 10, ...

) near San Francisco in Santa Clara County, California

Santa Clara County, officially the County of Santa Clara, is the sixth-most populous county in the U.S. state of California, with a population of 1,936,259, as of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. Santa Clara County and neighboring Sa ...

.

1934

In 1934, two two-seatWaco UBF

The Waco F series is a series of American-built general aviation and military biplane trainers of the 1930s from the Waco Aircraft Company.

Development

The Waco 'F' series of biplanes supplanted and then replaced the earlier 'O' series of 1927 ...

XJW-1 biplanes equipped with skyhooks were delivered to USS ''Macon''.

In June 1934, Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

Herbert V. Wiley took command of the airship, and shortly afterwards he surprised President Roosevelt (and the Navy) when ''Macon'' searched for and located the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

, which was then carrying the president back from a trip to Hawaii. Newspapers were dropped to the President on the ship, and the following communications were sent back to the airship: "from ''Houston'': 1519 The President compliments you and your planes on your fine performance and excellent navigation 1210 and 1519 Well Done and thank you for the papers the President 1245." The commander of the Fleet, Admiral Joseph M. Reeves

Joseph Mason "Bull" Reeves (November 20, 1872 – March 25, 1948) was an admiral in the United States Navy and an early and important supporter of U.S. Naval Aviation. Though a battleship officer during his early career, he became known as the ...

, was upset about the matter: but the Commander of the Bureau of Aviation, Admiral Ernest J. King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the Un ...

was not. Wiley, one of only three survivors of the crash of the ''Akron'', was soon promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

, served as the captain of the battleship in the final two years of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and then retired from the Navy in 1947 as a rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

.

Loss

Leading up to the crash

On 20 April 1934, the ''Macon'' left Sunnyvale for a challenging cross-continent flight east to

On 20 April 1934, the ''Macon'' left Sunnyvale for a challenging cross-continent flight east to Opa-locka, Florida

Opa-locka is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 16,463, up from 15,219 in 2010. The city was developed by Glenn Curtiss. Developed based on a ''One Thousand and One Nights'' theme, Op ...

. As with the ''Akron'' in 1932, ''Macon'' had to fly at or above pressure height when crossing the mountains, especially over Dragoon Pass

Dragoon Pass is a gap between the Dragoon Mountains and Little Dragoon Mountains

The Little Dragoon Mountains, are included in the Douglas Ranger District of Coronado National Forest, in Cochise County, Arizona.

The summit of the range is the c ...

at an elevation of . Then, in the West Texas heat, the sun raised the helium temperature, and the consequent expanding gas was automatically venting as the airship flew along at pressure height once again. Full engine power was required as the weather became turbulent. Following a severe gust near Van Horn, Texas

Van Horn is a town in and the seat of Culberson County, Texas, United States. According to the 2010 census, Van Horn had a population of 2,063, down from 2,435 at the 2000 census. The 2020 census results detailed a decline in population to 1,941. ...

, a diagonal girder in frame 17.5, near the fin junction, failed, followed soon by a second diagonal girder. Rapid damage control, led by Chief Boatswain's Mate Robert J. Davis, repaired the girders within a half hour. ''Macon'' completed the rest of the journey safely, mooring at Opa-locka on 22 April. More permanent repairs there took 9 days. However, the addition of duralumin channels, to reinforce frame 17.5 at its junction with the upper fin, was not completed. Grounding the ''Macon'' until these reinforcements were made was considered unnecessary.

Crash

On 12 February 1935, the repair process was still incomplete when, returning to Sunnyvale from fleet maneuvers, ''Macon'' ran into a storm offPoint Sur

Point Sur State Historic Park is a California State Park on the Big Sur coastline of Monterey County, California, United States, south of Rio Road in Carmel. The 1889 Point Sur Lighthouse is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Hist ...

, California. During the storm, the ship was caught in a wind shear

Wind shear (or windshear), sometimes referred to as wind gradient, is a difference in wind speed and/or direction over a relatively short distance in the atmosphere. Atmospheric wind shear is normally described as either vertical or horizontal ...

which caused structural failure

Structural integrity and failure is an aspect of engineering that deals with the ability of a structure to support a designed structural load (weight, force, etc.) without breaking and includes the study of past structural failures in order to ...

of the unstrengthened ring (17.5) to which the upper tailfin was attached. The fin failed to the side and was carried away. Pieces of structure punctured the rear gas cells and caused gas leakage. The commander, acting rapidly and on fragmentary information, ordered an immediate and massive discharge of ballast. Control was lost and, tail heavy and with engines running full speed ahead, ''Macon'' rose past the pressure height of , and kept rising until enough helium was vented to cancel the lift, reaching an altitude of . The last SOS call from Commander Wiley stated "Will abandon ship as soon as we land on the water somewhere 20 miles off of Pt. Sur, probably 10 miles at sea." It took 20 minutes to descend and, settling gently into the sea, ''Macon'' sank off Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area and its major city at the south of the bay, San Jose. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by a ...

. Only two crew members were lost thanks to the warm conditions and the introduction of life jackets and inflatable rafts after the ''Akron'' tragedy. Radioman 1st Class Ernest Edwin Dailey jumped ship while still too high above the ocean surface to survive the fall and Mess Attendant 1st Class Florentino Edquiba drowned while swimming back into the wreckage to try to retrieve personal belongings. An officer was rescued when Commander Wiley swam to his aid, an action for which he was later decorated. Sixty-four survivors were picked up by the cruiser , the cruiser took 11 aboard and the cruiser saved six.

Eyewitness Dorsey A. Pulliam, serving aboard USS ''Colorado'', wrote about the crash in a letter dated 13 February 1935:

In another letter, dated 16 February 1935, he wrote:

''Macon'', after 50 flights since it was commissioned, was stricken from the Navy list on 26 February 1935. Subsequent airships for Navy use were of a nonrigid design.

A depiction of the crash by artist Noel Sickles

Noel Douglas Sickles (January 24, 1910 – October 3, 1982) was an American commercial illustrator and cartoonist, best known for the comic strip '' Scorchy Smith''.

Sickles was born in Chillicothe, Ohio. Largely self-taught, his career beg ...

was the first piece of art sent over the wire by the Associated Press.

Wreck site exploration

The

The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

The Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) is a private, non-profit oceanographic research center in Moss Landing, California. MBARI was founded in 1987 by David Packard, and is primarily funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ...

(MBARI) succeeded in locating and surveying the debris field of ''Macon'' in February 1991, and was able to recover some artifacts. The exploration included sonar, video, and still camera data, as well as some recovery of parts.

In May 2005, MBARI returned to the site as part of a year-long research project to identify archaeological resources in the bay. Side-scan sonar was used to survey the site.

2006 expedition

A more complete return, including exploration withremotely operated vehicle

A remotely operated underwater vehicle (technically ROUV or just ROV) is a tethered underwater mobile device, commonly called ''underwater robot''.

Definition

This meaning is different from remote control vehicles operating on land or in the ai ...

s and involving researchers from MBARI, Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (abbreviated as NOAA ) is an United States scientific and regulatory agency within the United States Department of Commerce that forecasts weather, monitors oceanic and atmospheric conditio ...

's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, took place in September 2006. Video clips of the expedition were made available to the public through the OceansLive Web Portal, a service of NOAA.

The 2006 expedition was a success, and revealed a number of new surprises and changes since the last visit, approximately 15 years previously. High-definition video and more than 10,000 new images were captured, which were assembled into a navigation-grade photomosaic

In the field of photographic imaging, a photographic mosaic, also known under the term Photomosaic, is a picture (usually a photograph) that has been divided into (usually equal sized) tiled sections, each of which is replaced with another phot ...

of the wreck.

Protection

The location of the wreck site remains secret and is within theMonterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary

The Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS) is a federally protected marine area offshore of California's Big Sur and central coast in the United States. It is the largest US national marine sanctuary and has a shoreline length of ...

. It is not accessible to divers due to depth (). (39 pages, with 20 historic and wreckage exploration photos)

The U.S. National Park Service states:

The site was listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

on 29 January 2010. The listing was announced as the featured listing in the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

's weekly list of 12 February 2010.

In popular culture

''Macon'' is featured as a setting and key plot element in Max McCoy's novel ''Indiana Jones and the Philosopher's Stone

''Indiana Jones and the Philosopher's Stone'' is the ninth of 12 Indiana Jones novels published by Bantam Books. Max McCoy, the author of this book, also wrote three of the other Indiana Jones books for Bantam. Published on April 1, 1995, it is p ...

''; Indiana Jones

''Indiana Jones'' is an American media franchise based on the adventures of Dr. Henry Walton "Indiana" Jones, Jr., a fictional professor of archaeology, that began in 1981 with the film '' Raiders of the Lost Ark''. In 1984, a prequel, '' Th ...

travels aboard ''Macon'' while it makes a transatlantic flight

A transatlantic flight is the flight of an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe, Africa, South Asia, or the Middle East to North America, Central America, or South America, or ''vice versa''. Such flights have been made by fixed-wing air ...

to London.

''Macon'' is featured toward the end of the 1934 Warner Bros.

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (commonly known as Warner Bros. or abbreviated as WB) is an American film and entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California, and a subsidiary of Warner Bros. D ...

film ''Here Comes the Navy

''Here Comes the Navy'' (also known as ''Hey, Sailor'') is a 1934 American romantic comedy film written by Earl Baldwin and Ben Markson and directed by Lloyd Bacon. The film stars James Cagney, Pat O'Brien, Gloria Stuart and Frank McHugh. Stuart ...

'' starring James Cagney

James Francis Cagney Jr. (; July 17, 1899March 30, 1986) was an American actor, dancer and film director. On stage and in film, Cagney was known for his consistently energetic performances, distinctive vocal style, and deadpan comic timing. He ...

, Pat O'Brien Pat O'Brien may refer to:

Politicians

* Pat O'Brien (Canadian politician) (born 1948), member of the Canadian House of Commons

*Pat O'Brien (Irish politician) (c. 1847–1917), Irish Nationalist MP in the United Kingdom Parliament

Others

*Pat O'Br ...

and Gloria Stuart

Gloria Frances Stuart (born Gloria Stewart; July 4, 1910 September 26, 2010) was an American actress, visual artist, and activist. She was known for her roles in Pre-Code films, and garnered renewed fame late in life for her portrayal of Rose ...

. Cagney's character is assigned to ''Macon'' after serving on the , which is featured heavily in the film.

Footage of the ''Macon'' is used in the 1933 disaster film '' Deluge (1933 film)''.

The crash of ''Macon'' is depicted at the beginning of the 1937 film '' The Go Getter'', featuring George Brent

George Brent (born George Brendan Nolan; 15 March 1904 – 26 May 1979) was an Irish-American stage, film, and television actor. He is best remembered for the eleven films he made with Bette Davis, which included ''Jezebel'' and ''Dark Victory ...

as her helmsman.

See also

*List of airships of the United States Navy

List of airships of the United States Navy identifies the airships of the United States Navy by type, identification, and class. The fabric-clad rigid airships were treated as the equivalent of commissioned warships, and all others were treated mo ...

* List of airship accidents

The following is a partial list of airship accidents.

It should be stated that rigid airships operate differently than blimps which have no rigid structure.

See also

* List of ballooning accidents

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:List of Ai ...

* Hangar One, built to house ''Macon''

References

Bibliography

* * * *External links

Airships.net: USS ''Akron'' and ''Macon''

A 1964 KPIX-TV documentary about the U.S.S. ''Macon''

* ttp://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,441035,00.html Uncovering the USS ''Macon'': The Underwater Airship ''Der Spiegel''

Construction of the USS ''Macon'' Airship

(photo gallery) * KQED has put togethe

a video

with info about USS ''Macon'', historical and wreck-site footage, as well as info about the new zeppelin that is flying over the San Francisco Bay Area.

Moffett Field Museum

near San Jose, California has an exhibit dedicated to the USS ''Macon''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Macon (Zrs-5) Airborne aircraft carriers USS 1933 ships 1935 in aviation Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1935 Accidents and incidents involving balloons and airships 1935 in California 1930s United States aircraft Transportation on the National Register of Historic Places in California Goodyear aircraft Akron-class airships National Register of Historic Places in Monterey County, California Big Sur Aircraft on the National Register of Historic Places Moffett Field