USS Arkansas (BB-33) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Arkansas'' (BB-33) was a

The peacetime training regimen for ''Arkansas'' consisted of individual training, an annual fleet maneuver, and periodic maintenance in drydock. She also participated in gunnery and engineering competitions. After returning to the United States, ''Arkansas'' went into drydock at the

The peacetime training regimen for ''Arkansas'' consisted of individual training, an annual fleet maneuver, and periodic maintenance in drydock. She also participated in gunnery and engineering competitions. After returning to the United States, ''Arkansas'' went into drydock at the  After returning from the 1925 cruise, the ship was modernized at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. She had her twelve old coal-fired boilers replaced with four oil-fired models, which were trunked into a single larger funnel. She also had more deck armor added to protect her from plunging fire, and a short tripod mast was installed in place of the aft

After returning from the 1925 cruise, the ship was modernized at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. She had her twelve old coal-fired boilers replaced with four oil-fired models, which were trunked into a single larger funnel. She also had more deck armor added to protect her from plunging fire, and a short tripod mast was installed in place of the aft

''Arkansas'' participated in the Yorktown Sesquicentennial celebrations in October 1931, marking the 150th anniversary of the

''Arkansas'' participated in the Yorktown Sesquicentennial celebrations in October 1931, marking the 150th anniversary of the

''Arkansas'' was anchored in

''Arkansas'' was anchored in  On 18 April, ''Arkansas'' departed for Northern Ireland, where she trained for

On 18 April, ''Arkansas'' departed for Northern Ireland, where she trained for

After the end of the war, ''Arkansas'' participated in Operation Magic Carpet, the repatriation of American servicemen from the Pacific. She took around 800 men back to the United States, departing on 23 September, and reaching

After the end of the war, ''Arkansas'' participated in Operation Magic Carpet, the repatriation of American servicemen from the Pacific. She took around 800 men back to the United States, departing on 23 September, and reaching

Deck Log Book of the U.S.S. ''Arkansas'', 1943 MS 142

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Arkansas (BB-33) 1911 ships Artificial reefs Banana Wars ships of the United States Maritime incidents in 1946 Ships built by New York Shipbuilding Corporation Ships involved in Operation Crossroads Ships sunk as targets World War I battleships of the United States World War II battleships of the United States Wyoming-class battleships

dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

battleship, the second member of the , built by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. She was the third ship of the US Navy named in honor of the 25th state, and was built by the New York Shipbuilding Corporation

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

. She was laid down in January 1910, launched in January 1911, and commissioned into the Navy in September 1912. ''Arkansas'' was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of twelve guns and capable of a top speed of .

''Arkansas'' served in both World Wars. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, she was part of Battleship Division Nine, which was attached to the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

, but she saw no action during the war. During the interwar years, ''Arkansas'' performed a variety of duties, including training cruises for midshipmen and goodwill visits overseas.

Following the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, ''Arkansas'' conducted Neutrality Patrol

On September 3, 1939, the British and French declarations of war on Germany initiated the Battle of the Atlantic. The United States Navy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) established a combined air and ship patrol of the United States Atlantic coa ...

s in the Atlantic prior to America's entry into the war. Thereafter, she escorted convoys to Europe through 1944; in June, she supported the invasion of Normandy, and in August she provided gunfire support to the invasion of southern France. In 1945, she transferred to the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

, and bombarded Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

positions during the invasions

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

of Iwo Jima and Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

. After the end of the war, she ferried troops back to the United States as part of Operation Magic Carpet. ''Arkansas'' was expended as a target in Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

, a pair of nuclear weapon test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

s at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Seco ...

in July 1946.

Design

''Arkansas'' was long overall and had a beam of and adraft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of . She displaced as designed and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. The ship was powered by four-shaft Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

steam turbines

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

and twelve coal-fired

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

Babcock & Wilcox

Babcock & Wilcox is an American renewable, environmental and thermal energy technologies and service provider that is active and has operations in many international markets across the globe with its headquarters in Akron, Ohio, USA. Historicall ...

water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gen ...

s rated at , generating a top speed of . The ship had a cruising range of at a speed of .

The ship was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of twelve 12-inch/50 caliber Mark 7 guns guns in six twin Mark 9 gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s on the centerline, two of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward. The other four turrets were placed aft of the superstructure in two superfiring pairs. The secondary battery consisted of twenty-one /51 caliber guns mounted in casemates along the side of the hull. The main armored belt was thick, while the gun turrets had thick faces. The conning tower had thick sides.

Modifications

In 1925, ''Arkansas'' was modernized in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Her displacement increased significantly, to standard and full load. Her beam was widened to , primarily from the installation ofanti-torpedo bulge

The anti-torpedo bulge (also known as an anti-torpedo blister) is a form of defence against naval torpedoes occasionally employed in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars. It involved fitting (or retrofittin ...

s, and draft increased to . Her twelve coal-fired boilers were replaced with four White-Forster oil-fired boilers that had been intended for the ships cancelled under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

; performance remained the same as the older boilers. The ship's deck armor was strengthened by the addition of of armor to the second deck between the end barbettes, plus of armor on the third deck on the bow and stern. The deck armor over the engines and boilers was increased by and , respectively. Five of the 5-inch guns were removed and eight /50 caliber anti-aircraft guns were installed. The mainmast was removed to provide space for an aircraft catapult mounted on the Number 3 turret amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th ...

.

Service history

Pre-World War I

''Arkansas'' was laid down on 25 January 1910, atNew York Shipbuilding

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

in Camden, New Jersey. She was launched on 14 January 1911, after which fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work was effected. The ship was completed by September 1912, and was commissioned into the US Navy on 17 September, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard

The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was an important naval shipyard of the United States for almost two centuries.

Philadelphia's original navy yard, begun in 1776 on Front Street and Federal Street in what is now the Pennsport section of the ci ...

, under the command of Captain Roy C. Smith. Following her commissioning, ''Arkansas'' participated in a fleet review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

on 14 October 1912, for President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

. The ship took Taft aboard that day for a trip to Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

to inspect the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

, which was still under construction. ''Arkansas'' began her shakedown cruise after delivering Taft and his entourage to the Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the terri ...

. During this cruise, the Navy's first long-distance, continuous-wave

A continuous wave or continuous waveform (CW) is an electromagnetic wave of constant amplitude and frequency, typically a sine wave, that for mathematical analysis is considered to be of infinite duration. It may refer to e.g. a laser or particl ...

, wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

system was successfully tested, with regular transmissions received by ''Arkansas'' from a prototype Poulsen-arc transmission facility located in Arlington, Virginia. On 26 December, she returned to the Canal Zone to take Taft to Key West, Florida. After completing the voyage, ''Arkansas'' was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet and participated in fleet maneuvers off the east coast of the United States. ''Arkansas''s first overseas cruise, to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

, began in late October 1913. While there, she stopped in several ports, including Naples, Italy

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

on 11 November, where the ship celebrated the birthday of King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (Vittorio Emanuele Ferdinando Maria Gennaro di Savoia; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. He also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia (1936–1941) and ...

.

In early 1914, an international incident with Mexico culminated in the American occupation of Veracruz. ''Arkansas'' participated in the occupation, contributing four companies of naval infantry, which amounted to 17 officers and 313 enlisted men. The American forces fought their way through the city until they secured it. Two of ''Arkansas''s crewmen were killed in the fighting, and another two, John Grady and Jonas H. Ingram, received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

for actions during the occupation. The ship's detachment returned on 30 April; ''Arkansas'' remained in Mexican waters until she departed on 30 September, to return to the United States. While stationed in Veracruz, the ship was visited by Captain Franz von Papen, the German military attaché to the United States and Mexico, and Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock

Rear Admiral (Royal Navy), Rear Admiral Sir Christopher "Kit" George Francis Maurice Cradock (2 July 1862 – 1 November 1914) was an English senior officer of the Royal Navy. He earned a reputation for great gallantry.

Appointed to the royal ...

, the commander of the British 4th Cruiser Squadron

The 4th Cruiser Squadron and (also known as Cruiser Force H) was a formation of cruisers of the British Royal Navy from 1907 to 1914 and then again from 1919 to 1946.

The squadron was first established in 1907, replacing the North America and ...

, on 10 May and 30 May 1914, respectively.

''Arkansas'' arrived in Hampton Roads, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, on 7 October, after which she took part in exercises for a week. She then sailed to the New York Navy Yard for periodic maintenance. After repairs were completed, the ship steamed down to the Virginia Capes

The Virginia Capes are the two capes, Cape Charles to the north and Cape Henry to the south, that define the entrance to Chesapeake Bay on the eastern coast of North America.

In 1610, a supply ship learned of the famine at Jamestown when it ...

area for training maneuvers. She returned to the New York Navy Yard on 12 December, for additional maintenance. The repairs were completed within a month, and on 16 January 1915, ''Arkansas'' departed for the Virginia Capes for exercises on 19–21 January. The ship then steamed down to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba

Guantánamo (, , ) is a municipality and city in southeast Cuba and capital of Guantánamo Province.

Guantánamo is served by the Caimanera port near the site of a U.S. naval base. The area produces sugarcane and cotton wool. These are traditio ...

for exercises with the fleet. ''Arkansas'' returned for training off Hampton Roads on 7 April, followed by another maintenance period at the New York Navy Yard, starting on 23 April.

On 25 June, the repairs were complete, and ''Arkansas'' departed for Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, for torpedo practice and tactical maneuvers in Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Bay is a bay and estuary on the north side of Rhode Island Sound covering , of which is in Rhode Island. The bay forms New England's largest estuary, which functions as an expansive natural harbor and includes a small archipelago. Sm ...

, which lasted through late August. On 27 August, the ship was back in Hampton Roads. There, she participated in exercises off Norfolk through 4 October. She then returned to Newport, where she took part in strategic maneuvers on 5–14 October. She went to the New York Navy Yard on 15 October, where she was drydock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

ed for extensive maintenance. The work was completed by 8 November, when ''Arkansas'' returned to Hampton Roads. The ship was in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

for repairs on 19 November, which lasted until 5 January 1916, when she steamed south to the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

, via Hampton Roads, for winter exercises. She steamed to Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. The ...

on 12 March, for torpedo practice, before returning to Guantánamo Bay. She returned to the New York Navy Yard on 15 April, for an overhaul

Overhaul may refer to:

*The process of overhauling, see

** Maintenance, repair, and overhaul

**Refueling and overhaul (eg. nuclear-powered ships)

**Time between overhaul

* Overhaul (firefighting), the process of searching for hidden fire extensio ...

.

World War I

The United States declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917, joining the Allied Powers in World War I. ''Arkansas'' was at the time assigned toBattleship Division

A BatDiv or BATDIV was a standard U.S. Navy abbreviation or acronym for "battleship division." The Commander of a Battleship Division was known, in official Navy communications, as COMBATDIV (followed by a number), such as COMBATDIV ONE.

World Wa ...

7 stationed in Virginia. The ship patrolled the east coast and trained gun crews for the next fourteen months. The ship was sent to Britain in July 1918 to relieve the battleship , which had been assigned to operate with the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

in the 6th Battle Squadron since December 1917. ''Arkansas'' departed the United States on 14 July; while approaching the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

base in Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

, the battleship fired on what was thought to be a periscope from a German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

. The destroyers escorting ''Arkansas'' dropped depth charges but did not hit the alleged submarine. ''Arkansas'' arrived in Rosyth on 28 July, and joined the rest of Battleship Division 9 stationed there. For the remainder of the conflict, Battleship Division 9 operated as the 6th Battle Squadron

The 6th Battle Squadron was a squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of Battleships serving in the Grand Fleet and existed from 1913 to 1917.

History First World War August 1914

In August 1914, the 6th Battle Squadron was based at Portl ...

of the Grand Fleet.

On 11 November, the Armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

that ended World War I went into effect. The terms of the Armistice required Germany to intern the bulk of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

in Scapa Flow, under the supervision of the Grand Fleet. ''Arkansas'' and the other American warships participated in the internment; a combined fleet of 370 British, American, and French warships met the High Seas Fleet in the North Sea on 21 November, and escorted it into Scapa Flow. On 1 December, Battleship Division 9 was detached from the Grand Fleet, after which ''Arkansas'' departed the Firth of Forth for the Isle of Portland

An isle is an island, land surrounded by water. The term is very common in British English

British English (BrE, en-GB, or BE) is, according to Lexico, Oxford Dictionaries, "English language, English as used in Great Britain, as distinct fr ...

. She then went to sea to meet the ocean liner , which was carrying President Wilson to Europe. ''Arkansas'' and the other American naval forces in Europe escorted the ship into Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port city in the Finistère department, Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of the peninsula, and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an important harbour and the second French m ...

, on 13 December. After completing the escort, ''Arkansas'' sailed for New York City, arriving on 26 December, where the fleet participated in a Naval Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

for Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Josephus Daniels.

Inter-war period

1919–1927

The peacetime training regimen for ''Arkansas'' consisted of individual training, an annual fleet maneuver, and periodic maintenance in drydock. She also participated in gunnery and engineering competitions. After returning to the United States, ''Arkansas'' went into drydock at the

The peacetime training regimen for ''Arkansas'' consisted of individual training, an annual fleet maneuver, and periodic maintenance in drydock. She also participated in gunnery and engineering competitions. After returning to the United States, ''Arkansas'' went into drydock at the Norfolk Navy Yard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility tha ...

for an extensive overhaul. She then rejoined the fleet to conduct training exercises off Cuba, after which she crossed the Atlantic, bound for Europe. She reached Plymouth, on 12 May 1919, and then took weather observations on 19 May, and later served as a reference vessel to guide the Navy Curtiss NC

The Curtiss NC (Curtiss Navy Curtiss, nicknamed "Nancy boat" or "Nancy") was a flying boat built by Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company and used by the United States Navy from 1918 through the early 1920s. Ten of these aircraft were built, the mos ...

flying boats flying from Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, to Europe. After completing that task, she steamed to Brest, on 10 June, and picked up Admiral William S. Benson

William Shepherd Benson (25 September 1855 – 20 May 1932) was an admiral in the United States Navy and the first chief of naval operations (CNO), holding the post throughout World War I.

Early life and career

Born in Bibb County, Georgi ...

, the Chief of Naval Operations, and his wife. ''Arkansas'' carried them back to New York, after Benson was finished at the Peace Conference in Paris, arriving on 20 June.

On 19 July, ''Arkansas'' departed Hampton Roads, to join her new assignment, the US Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

, bound for San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

. She arrived 6 September, via the Panama Canal, and embarked Secretary and Mrs. Josephus Daniels. She took Daniels and his wife to Blakely Harbor, Washington, on 12 September, and the following day, participated in a naval review for President Wilson. On 19 September, ''Arkansas'' entered the Puget Sound Navy Yard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted u ...

for a general overhaul. She returned to the fleet in May 1920 for training operations off California. The Navy adopted a hull classification system, and on 17 July, assigned ''Arkansas'' the designation "BB-33". She steamed to Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

, in September, the first time she went to the islands. In early 1921, ''Arkansas'' visited Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, Chile, where she was received by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Arturo Alessandri Palma

Arturo Fortunato Alessandri Palma (; December 20, 1868 – August 24, 1950) was a Chilean political figure and reformer who served thrice as president of Chile, first from 1920 to 1924, then from March to October 1925, and finally from 1932 to ...

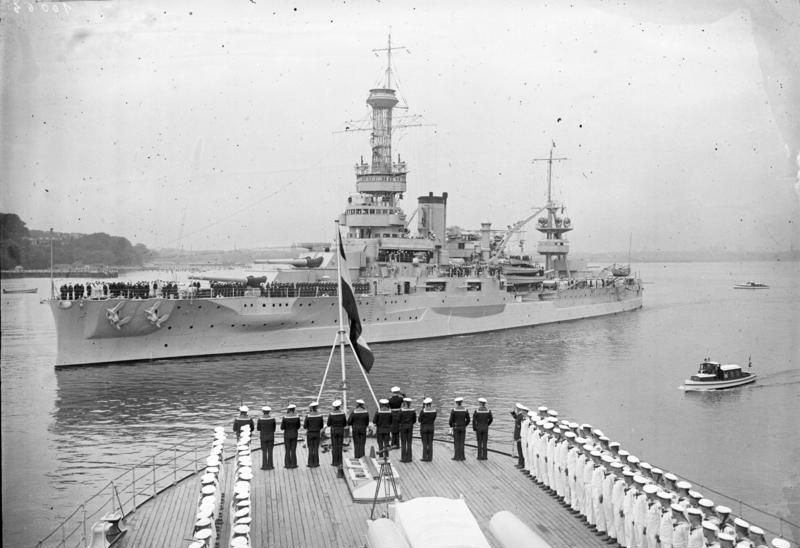

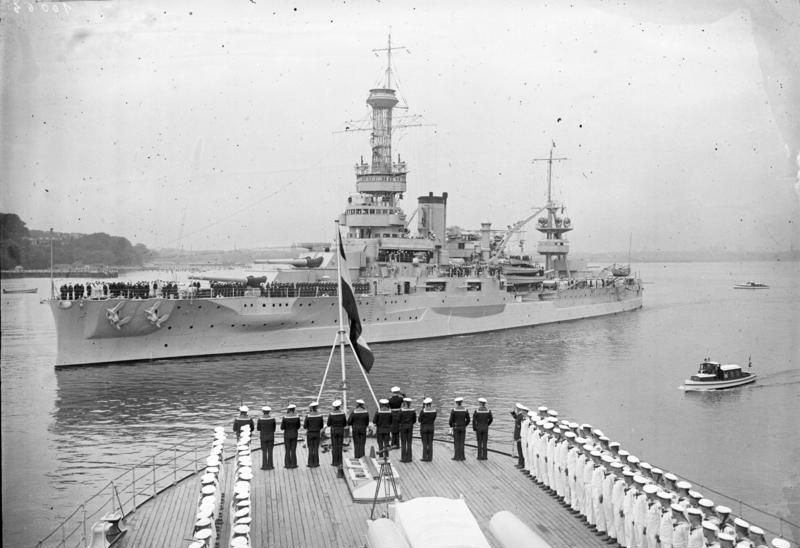

; the ship's crew manned the rail to honor the Chilean president.

In August 1921, ''Arkansas'' returned to the Atlantic Fleet, where she became the flagship of the Commander, Battleship Force, Atlantic Fleet. Throughout the 1920s, ''Arkansas'' carried midshipmen from the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

on summer cruises. She went on a tour of Europe in 1923; there, on 2 July, she stopped in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, and was visited by King Christian X of Denmark

Christian X ( da, Christian Carl Frederik Albert Alexander Vilhelm; 26 September 1870 – 20 April 1947) was King of Denmark from 1912 to his death in 1947, and the only King of Iceland as Kristján X, in the form of a personal union rathe ...

. She also stopped in Lisbon and Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. Another midshipmen cruise to Europe followed in 1924; the cruise for the next year went to the west coast of the United States. On 30 June 1925, she stopped in Santa Barbara, California

Santa Barbara ( es, Santa Bárbara, meaning "Saint Barbara") is a coastal city in Santa Barbara County, California, of which it is also the county seat. Situated on a south-facing section of coastline, the longest such section on the West Co ...

, to assist in the aftermath of the 1925 Santa Barbara earthquake

The 1925 Santa Barbara earthquake hit the area of Santa Barbara, California on June 29, with a moment magnitude between 6.5 and 6.8 and a maximum Mercalli Intensity of IX (''Violent''). It resulted in 13 deaths and destroyed the historic cente ...

. ''Arkansas'', the destroyer , and the patrol craft

A patrol boat (also referred to as a patrol craft, patrol ship, or patrol vessel) is a relatively small naval vessel generally designed for coastal defence, border security, or law enforcement. There are many designs for patrol boats, and the ...

''PE-34'' sent detachments ashore to help the police in Santa Barbara. They also established a temporary radio station in the city.

After returning from the 1925 cruise, the ship was modernized at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. She had her twelve old coal-fired boilers replaced with four oil-fired models, which were trunked into a single larger funnel. She also had more deck armor added to protect her from plunging fire, and a short tripod mast was installed in place of the aft

After returning from the 1925 cruise, the ship was modernized at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. She had her twelve old coal-fired boilers replaced with four oil-fired models, which were trunked into a single larger funnel. She also had more deck armor added to protect her from plunging fire, and a short tripod mast was installed in place of the aft cage mast

Lattice masts, or cage masts, or basket masts, are a type of observation Mast (sailing), mast common on United States Navy major warships in the early 20th century. They are a type of hyperboloid structure, whose weight-saving design was invented ...

. The modernization was completed in November 1926, after which ''Arkansas'' conducted a shakedown cruise in the Atlantic. She returned to Philadelphia, where she ran acceptance trials before she could rejoin the fleet. On 5 September 1927, ''Arkansas'' was present for ceremonies unveiling a memorial tablet honoring the French soldiers and sailors who died during the Yorktown campaign

The Yorktown campaign, also known as the Virginia campaign, was a series of military maneuvers and battles during the American Revolutionary War that culminated in the siege of Yorktown in October 1781. The result of the campaign was the surren ...

in 1781.

1928–1941

She returned to training cruises in May 1928, when she took a crew of midshipmen into the Atlantic along the east coast, along with a trip down toCuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. In June, she participated in a joint Army-Navy coast defense exercise as part of the hostile "attacking" fleet. In early 1929, ''Arkansas'' cruised in the Caribbean and near the Canal Zone. She returned to the United States in May 1929, for an overhaul in the New York Navy Yard. After emerging from drydock, she conducted another training cruise, this time to European waters; she spent time in the Mediterranean and visited Britain. ''Arkansas'' returned to the United States in August and operated with the Scouting Fleet

The Scouting Fleet was created in 1922 as part of a major, post-World War I reorganization of the United States Navy. The Atlantic and Pacific fleets, which comprised a significant portion of the ships in the United States Navy, were combined into ...

off the east coast. The training cruise for 1930 again went to Europe. She called in Cherbourg, France, Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, Germany, Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population ...

, Norway, and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

, Scotland. The cruise continued through the end of the year, and in 1931, the battleship visited Copenhagen, Greenock, Scotland, and Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

and Gibraltar in Spain. By September, the ship had crossed the Atlantic, and she stopped in Halifax, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. In February, ''Arkansas'' participated in Fleet Problem XII The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Proble ...

. During the maneuvers, she served as Admiral Arthur L. Willard

Arthur Lee Willard (February 21, 1870 – April 7, 1935) was a U.S. Navy Admiral who served his nation in two wars and was awarded the Navy Cross. He was also awarded the Legion of Honor by the French government and the Order of Leopold by the ...

's flagship, and she was "sunk" by a submarine. A month later, on 21–22 March, ''Arkansas'' conducted exercises with the carriers and .

''Arkansas'' participated in the Yorktown Sesquicentennial celebrations in October 1931, marking the 150th anniversary of the

''Arkansas'' participated in the Yorktown Sesquicentennial celebrations in October 1931, marking the 150th anniversary of the Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, also known as the Battle of Yorktown, the surrender at Yorktown, or the German battle (from the presence of Germans in all three armies), beginning on September 28, 1781, and ending on October 19, 1781, at Yorktown, Virgi ...

. She embarked President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

and his entourage on 17 October, and took them to the exposition, and returned them to Annapolis on 19–20 October. She then went into drydock for an extensive refit in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, which lasted until January 1932. During this time, she was under the command of George Landenberger. ''Arkansas'' was transferred to the Pacific Fleet after completing the refit; while en route, she stopped in to participate in the Mardi Gras celebration. She operated off the west coast through early 1934, at which point she was transferred back to the Atlantic Fleet, where she served as the flagship of the Training Squadron.

She conducted another training cruise to Europe in the summer of 1934. She stopped in Plymouth, England, Nice, France, Naples, Italy, and Gibraltar. She returned to Annapolis in August, after which she steamed to Newport. In Newport, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt reviewed the battleship from the yacht ''Nourmahal''. While there, ''Arkansas'' entered one of her cutters in a competition with the British cruiser for the Battenberg Cup

The Battenberg Cup is an award given annually as a symbol of operational excellence to the best ship or submarine in the United States Navy Atlantic Fleet. The cup was originally awarded as a trophy to the winner of cutter or longboat rowing co ...

, and the City of Newport Cup; ''Arkansas''s cutter won both races. The ship carried the 1st Battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions a ...

, 5th Marines to Culebra, for a Fleet Landing Exercise No. 1 (FLEX 1) in January 1935. She returned to training cruise duties in June, and she again took the midshipmen to Europe. Among the stops were Edinburgh, Oslo, Copenhagen, Gibraltar, and Funchal

Funchal () is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean. The city has a population of 105,795, making it the sixth largest city in Portugal. Because of its high ...

, on the island of Madeira. She disembarked the Naval Academy crew in August and began another training cruise to Halifax, this time for Naval Reservists, the following month. A refit was conducted in October after completing the cruise.

''Arkansas'' participated in the FLEX 2 at Culebra in January 1936, and then visited New Orleans, during Mardi Gras. She went to Norfolk for a major overhaul that lasted through the spring of 1936. After completing the overhaul, the ship took another midshipmen crew to European waters; she called in the ports of Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, England, Gothenburg, Sweden, and Cherbourg, and returned to Annapolis, in August. As in the previous year, she conducted another Reserve training cruise, and then went into drydock for an overhaul in Norfolk. The remainder of the 1930s followed a similar pattern; in 1937, the midshipmen training cruise went to Europe, but the 1938 and 1939 cruises remained in the western Atlantic.

At the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

in September 1939, ''Arkansas'' was moored at Hampton Roads, preparing to depart on a training cruise for the Naval Reserve. She departed to transport seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

mooring and aviation equipment from Norfolk to Narragansett Bay, where the Navy planned to set up a seaplane base. While in Newport, ''Arkansas'' picked up ordnance for destroyers and brought it back to Hampton Roads. After returning to Virginia, ''Arkansas'' was assigned to a reserve force for the Neutrality Patrol

On September 3, 1939, the British and French declarations of war on Germany initiated the Battle of the Atlantic. The United States Navy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) established a combined air and ship patrol of the United States Atlantic coa ...

s in the Atlantic, along with her sister , the battleships and and the carrier . On 11 January 1940, ''Arkansas'', ''New York'', and ''Texas'' left for fleet maneuvers off Cuba. She underwent an overhaul at Norfolk between 18 March and 24 May. After emerging from her refit, ''Arkansas'' conducted another midshipman training cruise, along with ''Texas'' and ''New York'', to Panama and Venezuela. In late 1940, she conducted three Naval Reserve training cruises in the Atlantic.

On 19 December 1940, with 500 naval reservists on board, the ''Arkansas'' collided at ~0300 hrs. with the outbound ''Collier Melrose'', of the Mystic Steamship Company of Boston, off of Sea Girt

Sea Girt is a borough in Monmouth County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2010 United States census, the borough's population was 1,828,Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

drydock after a 40-mile race to port. "The warship proceeded to her Hudson river

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

anchorage, minus only some paint and with a smashed lifeboat."

Over the months that followed, the United States gradually edged toward war in the Atlantic. The ship was assigned to the escort force for the Marines deployed to occupy Iceland, in July 1941, along with ''New York'', two cruisers, and eleven destroyers. The task force deployed from NS Argentia, Newfoundland, on 1 July, and were back in port by 19 July. Starting on 7 August, ''Arkansas'' went on a neutrality patrol in the mid-Atlantic that lasted a week. After returning to port, ''Arkansas'' traveled to the Atlantic Charter conference with President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, which took place on board . While there, the US Under Secretary of State, Sumner Welles, stayed aboard ''Arkansas''. She conducted another neutrality patrol between 2 and 11 September.

World War II

''Arkansas'' was anchored in

''Arkansas'' was anchored in Casco Bay

Casco Bay is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine on the southern coast of Maine, New England, United States. Its easternmost approach is Cape Small and its westernmost approach is Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth. The city of Portland sits along its s ...

, Maine, on 7 December 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and brought the United States into the war. A week later, she steamed to Hvalfjordur, Iceland, and returned to Boston on 24 January 1942. She conducted training maneuvers in Casco Bay, to prepare her crew for convoy escort duties. On 6 March, she arrived at Norfolk, to begin overhaul. The secondary battery was reduced to six 5-inch/51 cal guns. Also, 36 40 mm Bofors Bofors 40 mm gun is a name or designation given to two models of 40 mm calibre anti-aircraft guns designed and developed by the Swedish company Bofors:

*Bofors 40 mm L/60 gun - developed in the 1930s, widely used in World War II and into the 1990s

...

anti-aircraft (AA) guns (in quadruple mounts) and 26 20 mm Oerlikon

The Oerlikon 20 mm cannon is a series of autocannons, based on an original German Becker Type M2 20 mm cannon design that appeared very early in World War I. It was widely produced by Oerlikon Contraves and others, with various models empl ...

AA guns were added, the experience at Pearl Harbor having made the US Navy aware of the need for increased light AA armament. The 3-inch/50 caliber gun armament was also increased from 8 guns to 10. Work lasted until 2 July, after which time ''Arkansas'' conducted a shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

; she then proceeded to New York, arriving on 27 July. There, she became the flagship of Task Force 38 (TF 38), the escort for a convoy of twelve transports bound for Scotland. The convoy arrived in Greenock, on 17 August, and ''Arkansas'' returned to New York on 4 September.

''Arkansas'' again escorted a convoy to Scotland, returning to New York by 20 October. Thereafter, convoys were sent to North Africa, to support the invasion of North Africa. ''Arkansas'' covered her first such convoy, along with eight destroyers, on 3 November. She returned to New York on 11 December, where she went into dock for another overhaul. On 2 January 1943, ''Arkansas'' departed New York to conduct gunnery training in Chesapeake Bay. Back in New York by 30 January, the ship's crew prepared for a return to convoy escort duty. She escorted two convoys to Casablanca, between February and April, before returning to New York, for yet another period in drydock, which lasted until 26 May. ''Arkansas'' returned to duty as a training ship for midshipmen based at Norfolk. She resumed her convoy escort duties after four months, and on 8 October, she steamed to Bangor, Northern Ireland

Bangor ( ; ) is a city and seaside resort in County Down, Northern Ireland, on the southern side of Belfast Lough. It is within the Belfast metropolitan area and is 13 miles (22 km) east of Belfast city centre, to which it is linked ...

. She remained in Northern Ireland, through November, and departed on 1 December, bound for New York. After arriving on 12 December, ''Arkansas'' went into dock for more repairs, and then returned to Norfolk, on 27 December. The ship escorted another convoy bound for Ireland, on 19 January 1944, before returning to New York, on 13 February. Another round of gunnery drills followed on 28 March, after which ''Arkansas'' went to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

for more drydock period.

On 18 April, ''Arkansas'' departed for Northern Ireland, where she trained for

On 18 April, ''Arkansas'' departed for Northern Ireland, where she trained for shore bombardment

Naval gunfire support (NGFS) (also known as shore bombardment) is the use of naval artillery to provide fire support for amphibious assault and other troops operating within their range. NGFS is one of a number of disciplines encompassed by t ...

duties, as she had been assigned to the shore bombardment force in support of Operation Overlord, the invasion of northern France. She was assigned to Group II, along with ''Texas'' and five destroyers. Her float plane artillery observer

An artillery observer, artillery spotter or forward observer (FO) is responsible for directing artillery and mortar fire onto a target. It may be a ''forward air controller'' (FAC) for close air support (CAS) and spotter for naval gunfire su ...

pilots were temporarily assigned to VOS-7

Observation Squadron 7 (VOS-7) (or VCS-7) was a United States Navy artillery observer aircraft squadron based in England during Operation Overlord. The squadron was assembled expressly to provide aerial spotting for naval gunfire support during ...

flying Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

s from RNAS Lee-on-Solent (HMS Daedalus)

Royal Naval Air Station Lee-on-Solent (HMS ''Daedalus'') was one of the primary shore airfields of the Fleet Air Arm. First established as a seaplane base in 1917 during the First World War, it later became the main training establishment and ad ...

. On 3 June, she left her moorings, and on the morning of 6 June, took up a position about from Omaha Beach. At 05:52, the battleship's guns fired in anger for the first time in her career. She bombarded German positions around Omaha Beach until 13 June, when she was moved to support ground forces in Grandcamp les Bains. On 25 June, ''Arkansas'' bombarded Cherbourg, in support of the American attack on the port; German coastal guns straddled her several times, but scored no hits. Cherbourg fell to the Allies the next day, after which ''Arkansas'' returned to port, first in Weymouth, England, and then to Bangor, Northern Ireland

Bangor ( ; ) is a city and seaside resort in County Down, Northern Ireland, on the southern side of Belfast Lough. It is within the Belfast metropolitan area and is 13 miles (22 km) east of Belfast city centre, to which it is linked ...

, on 30 June.

On 4 July, ''Arkansas'' departed Northern Ireland for the Mediterranean Sea; she reached Oran, Algeria, on 10 July, before proceeding on to Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

, arriving on 21 July. There, she joined the support force for Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France. Again, the battleship provided gunfire support to the amphibious invasion along with six Allied cruisers, starting on 15 August. The bombardment lasted for two more days, after which she withdrew, first to Palermo, and then to Oran. ''Arkansas'' then returned to the United States, arriving in Boston, on 14 September, where she underwent another refit that lasted until early November. She then steamed to California, via the Panama Canal, and spent the rest of the year conducting training maneuvers. On 20 January 1945, ''Arkansas'' departed California for Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ...

, and then proceeded to Ulithi

Ulithi ( yap, Wulthiy, , or ) is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, about east of Yap.

Overview

Ulithi consists of 40 islets totaling , surrounding a lagoon about long and up to wide—at one of the larges ...

, to join the fleet in preparation for the amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted ...

on Iwo Jima. There, she was assigned to Task Force 54 (TF 54), which included five other battleships, four cruisers, and sixteen destroyers.

On 16 February, ''Arkansas'' was in position off Iwo Jima, and at 06:00, she opened fire on Japanese positions on the island's west coast. The bombardment lasted until 19 February, though she remained off the island throughout the Battle of Iwo Jima, ready to provide fire support to the American Marines ashore. She departed on 7 March, bound for Ulithi, and arrived on 10 March, where she rearmed and refueled in preparation for the next major operation in the Pacific War, the invasion of Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

. She departed Ulithi, on 21 March, and arrived off Okinawa, four days later, when she began the bombardment along with the rest of Task Force 54. The soldiers and Marines went ashore on 1 April, and ''Arkansas'' continued to provide gunfire support over the course of 46 days throughout the Battle of Okinawa. ''Kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending t ...

s'' repeatedly attacked the ship, though none struck her. She left the island in May, arriving in Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

on 14 May. She then proceeded to Leyte Gulf

Leyte Gulf is a gulf in the Eastern Visayan region in the Philippines. The bay is part of the Philippine Sea of the Pacific Ocean, and is bounded by two islands; Samar in the north and Leyte in the west. On the south of the bay is Mindanao ...

, on 12 June, arriving four days later. There, she was assigned to Task Group 95.7, along with ''Texas'' and three cruisers. She remained in the Philippines until 20 August, when she departed for Okinawa, arriving in Buckner Bay

is a bay on the southern coast of Okinawa Island on the Pacific Ocean in Japan. The bay covers and ranges between to deep. The bay is surrounded by the municipalities of Uruma, Kitanakagusuku, Nakagusuku, Nishihara, Yonabaru, Nanjō, a ...

on 23 August, by which time Japan had surrendered, ending World War II. Over the course of the war, ''Arkansas'' earned four battle star

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or ser ...

s.

Post-war

After the end of the war, ''Arkansas'' participated in Operation Magic Carpet, the repatriation of American servicemen from the Pacific. She took around 800 men back to the United States, departing on 23 September, and reaching

After the end of the war, ''Arkansas'' participated in Operation Magic Carpet, the repatriation of American servicemen from the Pacific. She took around 800 men back to the United States, departing on 23 September, and reaching Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

, Washington on 15 October. She made another three Magic Carpet trips between Pearl Harbor and the continental United States to ferry more soldiers home. During the first months of 1946, ''Arkansas'' lay at San Francisco. In late April, the ship got underway for Hawaii. She reached Pearl Harbor on 8 May, and departed Pearl Harbor on 20 May, bound for Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Seco ...

, earmarked for use as target for atomic bomb testing in Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

. On 1 July, ''Arkansas'' was exposed to an air burst in ABLE, but survived with extensive shock damage to her upper works, while her hull and armored turrets were lightly damaged.

On 25 July, the battleship was sunk by the underwater nuclear test BAKER at Bikini Atoll. Unattenuated by air, the shock was "transmitted directly to underwater hulls", and ''Arkansas'', only from the epicenter, appeared to have been "crushed as if by a tremendous hammer blow from below". It appears that the wave of water from the blast capsized the ship, which was then hammered down into the shallow bottom by the descent of the water column thrown up by the blast. Decommissioned on 29 July, ''Arkansas'' was struck from the Naval Vessel Register

The ''Naval Vessel Register'' (NVR) is the official inventory of ships and service craft in custody of or titled by the United States Navy. It contains information on ships and service craft that make up the official inventory of the Navy from t ...

on 15 August. The ship lies inverted in about of water at the bottom of Bikini Lagoon, where it acts as an artificial reef. There are many pictures of the wreck on the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propert ...

website.

Relationship with the Arkansas Flag

The ''Arkansas'' was the catalyst for the creation of theFlag of Arkansas

The flag of Arkansas, also known as the Arkansas flag, consists of a red field Charge (heraldry), charged with a large blue-bordered white Lozenge (heraldry), lozenge (or diamond). Twenty-nine Pentagram, five-pointed stars appear on the flag: t ...

. In 1912 the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) decided that they would present three flags to the battleship as she was nearing her commission date. The three flags the DAR chose to present were the American Flag

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the ca ...

, Navy battalion Ensign, and a state flag. When the DAR learned from the Arkansas Secretary of State, Earle W. Hodges, that Arkansas possessed no official state flag, they decided to hold a statewide competition to come up with one. The winning design was from Willie Kavanaugh Hocker of Pine Bluff, Arkansas, who was also a member of the DAR. On 26 February 1913, with a few alterations, Hocker's design become the official flag of Arkansas and was soon thereafter presented to the USS Arkansas by the DAR.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Deck Log Book of the U.S.S. ''Arkansas'', 1943 MS 142

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Arkansas (BB-33) 1911 ships Artificial reefs Banana Wars ships of the United States Maritime incidents in 1946 Ships built by New York Shipbuilding Corporation Ships involved in Operation Crossroads Ships sunk as targets World War I battleships of the United States World War II battleships of the United States Wyoming-class battleships