USS America (ID-3006) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''America'' (ID-3006) was a troop transport for the

''Amerika'' was a steel-hulled, 22,225 gross register tons, twin-screw, steam passenger liner—was launched on 20 April 1905 at

''Amerika'' was a steel-hulled, 22,225 gross register tons, twin-screw, steam passenger liner—was launched on 20 April 1905 at  On 14 April 1912, a ship's officer sent a telegram message to the Hydrographic Office in Washington, D.C. reporting that the ship "passed two large icebergs in 41 27N 50 8W on the 14th of April" signed "Knutp, 10;51p . This message was, coincidentally, relayed by the Marconi operator on to the station at

On 14 April 1912, a ship's officer sent a telegram message to the Hydrographic Office in Washington, D.C. reporting that the ship "passed two large icebergs in 41 27N 50 8W on the 14th of April" signed "Knutp, 10;51p . This message was, coincidentally, relayed by the Marconi operator on to the station at

Fortunately, since the brush with ''Instructor'' had caused but minor damage to ''America'', the transport was still able to carry out her mission. After embarking passengers for the return trip, she got underway on 25 July in company with , , , , , , and '' SS Patria''. Upon parting from these ships three days later, ''America'' raced on alone and reached Hoboken on the evening of 3 August.

Her eighth voyage began on 18 August with ''America's'' sailing in company with ''George Washington'' and ''Von Steuben''. She reached Brest on the 27th, discharged her troops, and embarked the usual mix of passengers. On this trip, she took on board 171 army officers, 165 army enlisted men, 18 French nuns, 10

Fortunately, since the brush with ''Instructor'' had caused but minor damage to ''America'', the transport was still able to carry out her mission. After embarking passengers for the return trip, she got underway on 25 July in company with , , , , , , and '' SS Patria''. Upon parting from these ships three days later, ''America'' raced on alone and reached Hoboken on the evening of 3 August.

Her eighth voyage began on 18 August with ''America's'' sailing in company with ''George Washington'' and ''Von Steuben''. She reached Brest on the 27th, discharged her troops, and embarked the usual mix of passengers. On this trip, she took on board 171 army officers, 165 army enlisted men, 18 French nuns, 10

At 04:45, ''America'', without warning, began listing to port and kept heeling over as water entered through the coaling ports which were still open although the coaling process had been completed over two hours before. Soon after the ship began listing, the general alarm was sounded throughout the ship. In the troop spaces, the urgent sound of that alarm awakened the sleeping soldiers who sought egress from their compartments. Soldiers and sailors both streamed up ladders topside; others jumped for safety on the coal barges, still alongside, or down cargo nets to the dock. Sentries on deck fired their rifles in the air as they sought to warn their comrades on board.

At 04:45, ''America'', without warning, began listing to port and kept heeling over as water entered through the coaling ports which were still open although the coaling process had been completed over two hours before. Soon after the ship began listing, the general alarm was sounded throughout the ship. In the troop spaces, the urgent sound of that alarm awakened the sleeping soldiers who sought egress from their compartments. Soldiers and sailors both streamed up ladders topside; others jumped for safety on the coal barges, still alongside, or down cargo nets to the dock. Sentries on deck fired their rifles in the air as they sought to warn their comrades on board.

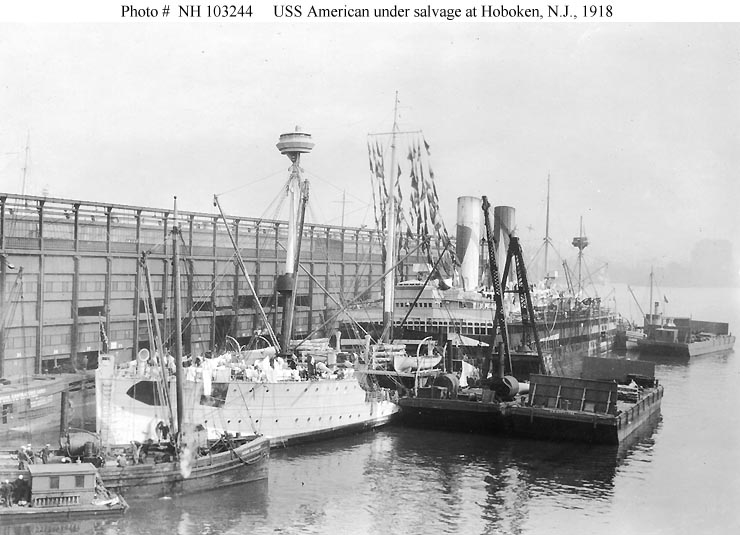

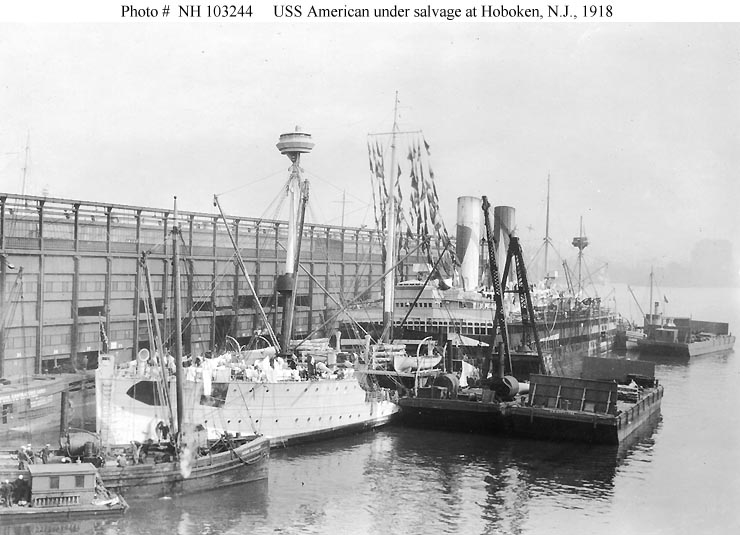

Rear Admiral Gleaves arrived at the dock soon after the ship sank, the water covering her main deck, to see personally what had happened to one of the largest transports in the Cruiser-Transport Force. Before the day was out, a court of inquiry began meeting to determine what had happened. Over the ensuing days, salvage efforts continued, including the removal of guns, cargo, and other equipment, as well as the search for the six men unaccounted for at muster. Eventually, the bodies of all, four soldiers and two sailors, were recovered. Divers worked continuously, closing open ports (almost all on "G" deck had been left open to allow the air to be cleared of the smell of disinfectants that had been used to cleanse and fumigate the compartments). She was raised and refloated on 21 November 1918, 10 days after the

Rear Admiral Gleaves arrived at the dock soon after the ship sank, the water covering her main deck, to see personally what had happened to one of the largest transports in the Cruiser-Transport Force. Before the day was out, a court of inquiry began meeting to determine what had happened. Over the ensuing days, salvage efforts continued, including the removal of guns, cargo, and other equipment, as well as the search for the six men unaccounted for at muster. Eventually, the bodies of all, four soldiers and two sailors, were recovered. Divers worked continuously, closing open ports (almost all on "G" deck had been left open to allow the air to be cleared of the smell of disinfectants that had been used to cleanse and fumigate the compartments). She was raised and refloated on 21 November 1918, 10 days after the

Foreshadowing the Magic Carpet operations which would follow

Foreshadowing the Magic Carpet operations which would follow

USAT ''America'' conducted two more voyages between Hoboken and Brest. Trouble highlighted her second voyage under the Army colors. An unruly crew at Brest on 4 December 1919 prompted Capt. Ford to appeal to the colonel commanding Base Section Number Five, at Brest, for an armed guard, fearing mutiny. Apparently, the Army matter was resolved, for the ship reached Hoboken five days before Christmas 1919.

On 20 December, the day ''America'' was scheduled to arrive at the port of debarkation, arrangements were made to turn ''America'' and two other Army transports, and , over to the USSB for operation while they were being carried on the roll of the Army Transport Reserve. However, before the year 1919 was out, events in a faraway land caused a temporary change in this plan.

A glance back at developments on the Eastern Front during

USAT ''America'' conducted two more voyages between Hoboken and Brest. Trouble highlighted her second voyage under the Army colors. An unruly crew at Brest on 4 December 1919 prompted Capt. Ford to appeal to the colonel commanding Base Section Number Five, at Brest, for an armed guard, fearing mutiny. Apparently, the Army matter was resolved, for the ship reached Hoboken five days before Christmas 1919.

On 20 December, the day ''America'' was scheduled to arrive at the port of debarkation, arrangements were made to turn ''America'' and two other Army transports, and , over to the USSB for operation while they were being carried on the roll of the Army Transport Reserve. However, before the year 1919 was out, events in a faraway land caused a temporary change in this plan.

A glance back at developments on the Eastern Front during

For ''America'', further service awaited with the United States Lines. Reconditioned to resume her place in the transatlantic passenger trade, she commenced her maiden voyage as an American passenger liner on 22 June 1921, sailing for Bremen, Germany, with stops at Plymouth, England, and Cherbourg, France, en route.

For the next eleven years, ''America'' plied the Atlantic, ranking third only in size to the United States Lines' ships SS Leviathan, ''Leviathan'' and ''SS George Washington, George Washington''—the latter running mate from the Cruiser-Transport Force days. In June 1924, the ''America'' transported the United States Olympic team to Cherbourg, France, for the summer games held in Paris, making the return leg to New York in August. On two occasions, ''America'' figured in the headlines.

For ''America'', further service awaited with the United States Lines. Reconditioned to resume her place in the transatlantic passenger trade, she commenced her maiden voyage as an American passenger liner on 22 June 1921, sailing for Bremen, Germany, with stops at Plymouth, England, and Cherbourg, France, en route.

For the next eleven years, ''America'' plied the Atlantic, ranking third only in size to the United States Lines' ships SS Leviathan, ''Leviathan'' and ''SS George Washington, George Washington''—the latter running mate from the Cruiser-Transport Force days. In June 1924, the ''America'' transported the United States Olympic team to Cherbourg, France, for the summer games held in Paris, making the return leg to New York in August. On two occasions, ''America'' figured in the headlines.

The second newsworthy incident began on 22 January 1929 when ''America''—then commanded by Captain George Fried—was steaming from France to New York. As she battled her way through a major storm, the liner picked up distress signals from the Italian steamship, ''Florida''. Guided by her radio direction finder, the American ship homed in on the Italian and, late the following afternoon, finally sighted the endangered vessel through light snow squalls. Taking a position off ''Florida's'' weather beam, ''America'' lowered her number one Lifeboat (shipboard), lifeboat, commanded by her Chief Officer, Harry Manning, with a crew of eight men.

After the boat had been rowed to within of the listing ''Florida'', Manning had a line thrown across to the eager crew of the distressed freighter One by one, the 32 men from the Italian ship came across the rope. By the time the last of them, the ship's captain, had been dragged on board the pitching lifeboat, the winds had reached gale force, with violent snow and rain squalls, with a high, rough, sea running. Then, via ladders, ropes, cargo nets, and two homemade breeches buoys, sailors on board ''America'' brought up ''Florida's'' survivors, until all 32 were safe and sound. Finally, they pulled their shipmates from the rescue party back on board. Chief Officer Manning was brought up last. Captain Fried felt that it was highly dangerous to attempt to hoist the number one lifeboat on board and, rather than risk lives, ordered it cut adrift.

The second newsworthy incident began on 22 January 1929 when ''America''—then commanded by Captain George Fried—was steaming from France to New York. As she battled her way through a major storm, the liner picked up distress signals from the Italian steamship, ''Florida''. Guided by her radio direction finder, the American ship homed in on the Italian and, late the following afternoon, finally sighted the endangered vessel through light snow squalls. Taking a position off ''Florida's'' weather beam, ''America'' lowered her number one Lifeboat (shipboard), lifeboat, commanded by her Chief Officer, Harry Manning, with a crew of eight men.

After the boat had been rowed to within of the listing ''Florida'', Manning had a line thrown across to the eager crew of the distressed freighter One by one, the 32 men from the Italian ship came across the rope. By the time the last of them, the ship's captain, had been dragged on board the pitching lifeboat, the winds had reached gale force, with violent snow and rain squalls, with a high, rough, sea running. Then, via ladders, ropes, cargo nets, and two homemade breeches buoys, sailors on board ''America'' brought up ''Florida's'' survivors, until all 32 were safe and sound. Finally, they pulled their shipmates from the rescue party back on board. Chief Officer Manning was brought up last. Captain Fried felt that it was highly dangerous to attempt to hoist the number one lifeboat on board and, rather than risk lives, ordered it cut adrift.

When the United States transferred fifty surplus destroyers to the British government in the destroyers for bases agreement during the fall of 1940, two of the acquisitions were bases at Argentia, Newfoundland and the future Fort Pepperrell at St. John's, Newfoundland, but no barracks existed at St. John's for troops, so an interim solution had to be provided.

As a result, in October 1940, ''America'' was acquired by the

When the United States transferred fifty surplus destroyers to the British government in the destroyers for bases agreement during the fall of 1940, two of the acquisitions were bases at Argentia, Newfoundland and the future Fort Pepperrell at St. John's, Newfoundland, but no barracks existed at St. John's for troops, so an interim solution had to be provided.

As a result, in October 1940, ''America'' was acquired by the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. She was launched in 1905 as SS ''Amerika'' by Harland and Wolff

Harland & Wolff is a British shipbuilding company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It specialises in ship repair, shipbuilding and offshore construction. Harland & Wolff is famous for having built the majority of the ocean liners for the W ...

in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

for the Hamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. As a passenger liner

A low-ionization nuclear emission-line region (LINER) is a type of galactic nucleus that is defined by its spectral line emission. The spectra typically include line emission from weakly ionized or neutral atoms, such as O, O+, N+, and S+. ...

, she sailed primarily between Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

and New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. On 14 April 1912, ''Amerika'' transmitted a wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

message about iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

s near the same area where RMS ''Titanic'' struck one and sank less than three hours later. At the outset of the war, ''Amerika'' was docked at Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

; rather than risk seizure by the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, she remained in port for the next three years.

Hours before the American entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, p ...

, ''Amerika'' was seized and placed under control of the United States Shipping Board

The United States Shipping Board (USSB) was established as an emergency agency by the 1916 Shipping Act (39 Stat. 729), on September 7, 1916. The United States Shipping Board's task was to increase the number of US ships supporting the World War ...

(USSB). Later transferred to the U.S. Navy for use as a troop transport, she was initially commissioned as USS ''Amerika'' with Naval Registry Identification Number A Naval Registry Identification Number is a unique identifier that the U.S. Navy used for privately owned and naval vessels in the first half of the 20th century.

Overview

During World War I, in 1916, the U.S. Navy began a registry of privately ...

3006 (ID-3006), but her name was soon Anglicized to ''America''. As ''America'' she transported almost 40,000 troops to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. She sank at her mooring in Hoboken in 1918, but was soon raised and reconditioned. After the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

, ''America'' transported more than 51,000 troops back home from Europe. In 1919, she was handed over to the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

for use by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

as USAT ''America'', under whose control she remained until 1920.

Returned to the USSB in 1920, ''America'' was initially assigned to the United States Mail Steamship Company, and later, after that company's demise, to United States Lines, for which she plied the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe a ...

on Bremen to New York routes. In March 1926, due to an oil leak from inside the ship, near the end of one of her periodic refits, ''America'' suffered a fire that raged for seven hours and burned nearly all of her passenger cabins. Despite almost $2,000,000 in damage, the ship was rebuilt and back in service by the following year. In April 1931, ''America'' ended her service for the United States Lines and was laid up for almost nine years.

In October 1940, ''America'' was reactivated for the U.S. Army and renamed USAT ''Edmund B. Alexander''. After establishing the Newfoundland Base Command

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and a stint as a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for sai ...

at St. John's, Newfoundland in January–May 1941, ''Edmund B. Alexander'' was refitted for use as a troopship for World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

duty. She was first placed on a to Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

route, but later transferred to trooping between New York and European ports. At the end of the war, ''Edmund B. Alexander'' was converted to carry military dependents, remaining in that service until 1949. She was placed in reserve until sold for scrapping in January 1957.

SS ''Amerika''

''Amerika'' was a steel-hulled, 22,225 gross register tons, twin-screw, steam passenger liner—was launched on 20 April 1905 at

''Amerika'' was a steel-hulled, 22,225 gross register tons, twin-screw, steam passenger liner—was launched on 20 April 1905 at Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdom ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

, by the shipbuilding firm Harland and Wolff, Ltd. Built for the Hamburg America Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

, the steamer entered transatlantic service in the autumn of 1905, when she departed Hamburg on 11 October, bound for the New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

. The night before her inaugural voyage on 19 June 1905, Kaiser Wilhelm II boarded the ship and dined on a menu created by Auguste Escoffier, the French chef who was in charge of organizing the restaurant on board ''Amerika''.

A slightly larger sister ship, '' Kaiserin Auguste Victoria'' was being built at the same time at Hamburg and would remain the largest ship in the world until the ''Lusitania''. Easily one of the most luxurious passenger vessels to sail the seas, ''Amerika'' entered upper New York Bay

New York Bay is the large tidal body of water in the New York–New Jersey Harbor Estuary where the Hudson River, Raritan River, and Arthur Kill empty into the Atlantic Ocean between Sandy Hook and Rockaway Point.

Geography

New York Bay is usu ...

on 20 October, reaching the Hamburg America piers at Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 ...

, in mid-afternoon. Some 2,000 people turned out to watch her as she was moored near her consorts at the Hamburg America Line which were bedecked in colorful bunting in nearby slips.

From 1905 to 1914, ''Amerika'' plied the North Atlantic trade routes touching at Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Febr ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, while steaming between Hamburg and New York. Toward the end of that period, her itinerary was altered so that the ship also called at Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

, France, and Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, England.

Cape Race

Cape Race is a point of land located at the southeastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland, in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Its name is thought to come from the original Portuguese name for this cape, "Raso", mean ...

because the transmitter of ''Amerika'' was not powerful enough to reach Cape Race directly.

''Amerika'' was responsible for the accidental loss of British submarine by collision northeast of Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

in the early hours of 4 October 1912.

The eruption of fighting at the outset of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

caught ''Amerika'' at Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, where she was preparing to sail for home. Although due to leave port on 1 August 1914, ''Amerika'' stayed at Boston to avoid capture by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. She remained there through almost three years of United States neutrality.

During her voyage from New York to Europe in the second week of April 1911, ''Amerika'' carried the mortally ill composer Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

back home. He was to die in Vienna on 18 May 1911.

Interiors

Lavishly decorated throughout, ''Amerika'' boasted of a couple of unique shipboard features; an electric passenger elevator (the first to be installed on a passenger liner), and an ''à la carte'' restaurant which, from early morning to midnight, offered a variety of dishes to delight the discriminating gourmet. It was managed by the famous hotelier César Ritz, while the renowned chef Auguste Escoffier was responsible for creating the menu, organizing and staffing the kitchen and restaurant. French architect Charles Mewès was responsible for designing the interiors of ''Amerika'', while the English firm ofWaring & Gillow

Waring & Gillow (also written as Waring and Gillow) was a noted firm of English furniture manufacturers and antique dealers formed in 1897 by the merger of Gillows of Lancaster and London and Waring of Liverpool.

Background Gillow & Co.

The fir ...

was contracted to decorate the main public rooms. ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication i ...

'' stated simply that "the rooms which they aring & Gillowhave decorated are artistic triumphs." ''The Sphere

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

'' wrote of the interiors that "the whole of the vessel is planned on such a scale that the various rooms do not any longer partake of the nature of ship's cabins but are rather a series of sumptuously-furnished and comfortably-contrived apartments such as one would find in a costly house on shore." ''Amerika's'' interiors were a departure from the prevailing style on ocean liners up to that point, as they were modelled after a luxury hotel rather than on castles and palaces.

The grand staircase in First-Class was designed in the Adam style, as was the ladies' drawing room. The drawing room had white walls inset with blue Wedgwood

Wedgwood is an English fine china, porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer that was founded on 1 May 1759 by the potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood and was first incorporated in 1895 as Josiah Wedgwood and Sons Ltd. It was rapid ...

plaques. It was topped by a glass dome, with furniture upholstered in rose-colored silk and draperies in rose and silver. Adjoining the drawing room was a writing room in the Empire style

The Empire style (, ''style Empire'') is an early-nineteenth-century design movement in architecture, furniture, other decorative arts, and the visual arts, representing the second phase of Neoclassicism. It flourished between 1800 and 1815 durin ...

, with paneling of white and gold and heliotrope-colored silk panels. There was also an Elizabethan style

Elizabethan architecture refers to buildings of a certain style constructed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland from 1558–1603. Historically, the era sits between the long era of the dominant architectural style o ...

smoking room, which occupied two floors connected by a staircase. The room was paneled in oak "of the roughly-fashioned style of the sixteenth century" and along the walls of the upper-level was a carved frieze illustrating scenes from the life of Saint Hubert

Hubertus or Hubert ( 656 – 30 May 727 A.D.) was a Christian saint who became the first bishop of Liège in 708 A.D. He is the patron saint of hunters, mathematicians, opticians and metalworkers. Known as the "Apostle of the Ardennes", he was ...

. The chimneypiece of the smoking room was made of brick, with a stone hearth. The room was lit by lanterns hung from the oak beams which crossed the ceiling.

The First-Class dining saloon was at the bottom of the three-deck high grand staircase. The saloon, which was in the Louis XVI style

Louis XVI style, also called ''Louis Seize'', is a style of architecture, furniture, decoration and art which developed in France during the 19-year reign of Louis XVI (1774–1793), just before the French Revolution. It saw the final phase of t ...

, was as wide as the ship and about 100 ft. in length. It was overlooked by a balcony on four sides. It featured copies of paintings by François Boucher

François Boucher ( , ; ; 29 September 1703 – 30 May 1770) was a French painter, draughtsman and etcher, who worked in the Rococo style. Boucher is known for his idyllic and voluptuous paintings on classical themes, decorative allegories ...

at either end, with furniture in "gold-colored West Indian satin, veined with green." The ''à la carte'' restaurant was modelled on the Ritz-Carlton Grill at the Carlton Hotel in London, which Mewès had designed. The Carlton Hotel Company Board agreed to let the shipping company use the name "Ritz-Carlton Restaurant." It was in the Louis XVI style, with paneling made of chestnut and mahogany, enriched with bronze ormolu accents in vegetative designs. The sideboards were made of matching woods and ormolu, while the chairs were copied from examples at Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

from the Louis XVI period. At the center of the room was a skylight with gray and yellow-colored panels of glass. Children had their own nursery, which was decorated with painted scenes from nursery rhymes.

In terms of accommodation, the finest suites on board were the two called the "Imperial State Rooms", one decorated in the Adam style, the other in the Empire style. There were also 13 ''chambres de luxe'' decorated by Waring & Gillow in a range of historic styles, including Georgian, Queen Anne, Adam, and Sheraton.

USS ''America'' (1917 to 1919)

On 6 April 1917, in anticipation that Congress would declare war on Germany,Edmund Billings Edmund Billings (January 14, 1868 – February 7, 1929) was a Canadian born American financier, banker, sociologist, philanthropist, and government official who served on a number of relief committees and was Collector of Customs for the Port of Bos ...

, the Collector of Customs for the Port of Boston, ordered that ''Amerika'' and four other German ships (the ''Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

'', ''Wittekind

Widukind, also known as Wittekind, was a leader of the Saxons and the chief opponent of the Frankish king Charlemagne during the Saxon Wars from 777 to 785. Charlemagne ultimately prevailed, organized Saxony as a Frankish province, massacred th ...

'', ''Köln

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 million ...

'', and '' Ockenfels'') be seized. It remained inactive until it was taken by deputies under the orders of John A. Donald, the Commissioner of the United States Shipping Board

The United States Shipping Board (USSB) was established as an emergency agency by the 1916 Shipping Act (39 Stat. 729), on September 7, 1916. The United States Shipping Board's task was to increase the number of US ships supporting the World War ...

(USSB), on 25 July 1917. Upon inspecting the liner, American agents found her filthy and discovered that her crew had sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

d certain elements of the ship's engineering plant. Nevertheless, with her officers and men detained on Deer Island, ''Amerika'' was earmarked by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

for service in the Cruiser and Transport Force The Cruiser and Transport Service was a unit of the United States Navy's Atlantic Fleet during World War I that was responsible for transporting American men and materiel to France.

Composition

On 1 July 1918, the Cruiser and Transport Force wa ...

as a troop transport. Given the identification number 3006, she was placed in commission as USS ''Amerika'' (ID-3006) at 08:00 on 6 August 1917, at the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

with Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

Frederick L. Oliver in temporary command. Ten days later, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

George C. Day arrived on board and assumed command.

Over the ensuing weeks, she was converted into a troopship, and while this work was in progress, Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Josephus Daniels

Josephus Daniels (May 18, 1862 – January 15, 1948) was an American newspaper editor and publisher from the 1880s until his death, who controlled Raleigh's '' News & Observer'', at the time North Carolina's largest newspaper, for decades. A ...

promulgated General Order No. 320, changing the names of several ex-German ships on 1 September 1917. As a consequence ''Amerika'' was renamed ''America''.

The major part of her conversion and repair work having been completed by late September, ''America'' ran a six-hour trial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribun ...

outside Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, and is located adjacent to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the northeastern United States.

History

...

on the morning of 29 September. The ship managed to make three more revolutions than she had ever made before. The completion of these trials proved to be a milestone in the reconditioning of the former German ships, for ''America'' was the last to be readied for service in the American Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

.

On 18 October 1917, ''America'' departed the Boston Navy Yard and, two days later, arrived at Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 ...

, which would be the port of embarkation for all of her wartime voyages carrying doughboys to Europe. There, she loaded coal and cargo; received a brief visit from Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

Albert Gleaves

Albert Gleaves (January 1, 1858 – January 6, 1937) was a decorated admiral in the United States Navy, also notable as a naval historian.

Biography

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, Gleaves graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1877. ...

, the commander of the Cruiser-Transport Force; and took on board her first contingent of troops. Completing the embarkation on the afternoon of 29 October, ''America'' sailed for France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

on the morning of 31 October, in company with the transports , , , the armored cruiser , and destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s and .

For more than a week, the passage was uneventful. Then, on 7 November, ''Von Steuben'' struck ''Agamemnon'' while zig-zagging. As ''America'' war history states: "The excitement caused by the collision of these great ships was greatly increased when the ''Von Steuben'' sent out a signal that a submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

was sighted." The ships in the convoy dispersed as if on signal, only to draw together in formation once more when the "enemy" failed to materialize. All vessels resumed their stations—all, that is, except ''Von Steuben'' whose bow was open to the sea from the damage suffered in the collision. Even the crippled transport rejoined the convoy the following afternoon. Met on 12 November off the coast of France by an escort consisting of converted American yachts and French airplanes and destroyers, the convoy reached safe haven at Brest, ''America'' only wartime port of debarkation. She dropped her anchor at 11:15 and began discharging the soldiers.

Underway again on 29 November, the ship returned to the United States, in convoy, reaching Hoboken on 10 December. She then remained pier side through Christmas and New Year's Day and headed for France again on 4 January 1918, carrying 3,838 troops and 4,100 tons of cargo. The following day, she fell in with the transport , and armored cruiser , her escort for the crossing. Except for the after control station personnel reporting a torpedo track crossing in the ship's wake on 17 January—shortly before the transport reached Brest—this voyage was uneventful.

''America'' arrived at Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 6 February and the next day entered the Norfolk Navy Yard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility t ...

for repairs and alterations. At this time, the ship received an additional pair of guns to augment her main battery.

Troop ship duty continued:

* Departed Hoboken

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,69 ...

27 February 1918 with 3,877 troops, accompanied by ''Agamemnon'' and ''Mount Vernon'', arrived at Brest on 10 March.

* Departed Brest 17 March 1918 with French naval personnel (4 officers, 10 petty officers, 77 men), arrived 10 days later.

* Departed Hoboken 6 April with 3,877 troops, joined on the 8th and ''Agamemnon'' on the 12th, made port 15 April.

* A week later, after disembarking her charges, the transport took on board the survivors from the American munitions ship, ''Florence H'', which had exploded at Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (french: Baie de Quiberon) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to t ...

five days before, and sailed for the United States. Entered the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

on 1 May.

* Sailed a week later, joined on 10 May by , , coming from Newport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the U ...

. Shortly after 03:00 on 18 May, four men sighted what appeared to be a periscope some 50 yards from the ship, but it vanished. Arrived in Brest later that day.

* Sailed for the United States on 21 May at 15:50, accompanied by ''George Washington'', ''De Kalb'', and a coastal escort of destroyers. Escort attacked a suspected submarine four hours out then continued. Escort left convoy after 22:00 on 22 May. ''De Kalb'' fell behind the next day, and ''America'' steamed alone on 25 May. Reached Hoboken four days later.

* Left Hoboken 10 June with 5,305 troops, accompanied by ''Agamemnon'', ''Mount Vernon'', and . Joined near Europe by coastal escort eight days later, reached Brest 19 June.

* Left Brest 23 June accompanied by ''Orizaba'', parted company three days later, arrived at Hoboken on 1 July.

During the brief respite that followed, ''America'' briefly received Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves

Albert Gleaves (January 1, 1858 – January 6, 1937) was a decorated admiral in the United States Navy, also notable as a naval historian.

Biography

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, Gleaves graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1877. ...

on board and was painted in a dazzle camouflage

Dazzle camouflage, also known as razzle dazzle (in the U.S.) or dazzle painting, is a family of ship camouflage that was used extensively in World War I, and to a lesser extent in World War II and afterwards. Credited to the British marine ...

pattern designed to obscure the ship's lines, a pattern that she would wear for the remainder of her days as a wartime transport.

Late on 9 July, ''America'' sailed on the seventh of her voyages to Europe for the Navy. Just before midnight on the 14th, while the convoy steamed through a storm that limited visibility severely, a stranger, SS ''Instructor'', unwittingly wandered into the formation and ran afoul of ''America''. In spite of attempts at radical course changes by both ships, ''America'' struck the intruder near the break of her poop deck and sheared off her stern which sank almost immediately. ''America's'' swing threw the wreck of ''Instructor'' clear, allowing it to pass down the transport's port side without touching before it sank less than 10 minutes later. ''America'' stopped briefly to search for survivors, but the danger of lurking U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s limited the pause to the most abbreviated of durations, and the storm added other obstacles. As a result, ''America'' succeeded in rescuing only the 11 ''Instructor'' crewmen who managed to man a lifeboat. Tragically, the exigencies of war forced ''America'' to abandon the other 31 to their fate. A court of inquiry held at Brest on 18 July, soon after ''America'' arrived there, exonerated her captain from any blame with regard to the sad incident.

Fortunately, since the brush with ''Instructor'' had caused but minor damage to ''America'', the transport was still able to carry out her mission. After embarking passengers for the return trip, she got underway on 25 July in company with , , , , , , and '' SS Patria''. Upon parting from these ships three days later, ''America'' raced on alone and reached Hoboken on the evening of 3 August.

Her eighth voyage began on 18 August with ''America's'' sailing in company with ''George Washington'' and ''Von Steuben''. She reached Brest on the 27th, discharged her troops, and embarked the usual mix of passengers. On this trip, she took on board 171 army officers, 165 army enlisted men, 18 French nuns, 10

Fortunately, since the brush with ''Instructor'' had caused but minor damage to ''America'', the transport was still able to carry out her mission. After embarking passengers for the return trip, she got underway on 25 July in company with , , , , , , and '' SS Patria''. Upon parting from these ships three days later, ''America'' raced on alone and reached Hoboken on the evening of 3 August.

Her eighth voyage began on 18 August with ''America's'' sailing in company with ''George Washington'' and ''Von Steuben''. She reached Brest on the 27th, discharged her troops, and embarked the usual mix of passengers. On this trip, she took on board 171 army officers, 165 army enlisted men, 18 French nuns, 10 YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

secretaries, a Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

official and two nurses, two civilians and two sailors before sailing on 30 August. One of the civilians was the distinguished conductor Walter Damrosch

Walter Johannes Damrosch (January 30, 1862December 22, 1950) was a German-born American conductor and composer. He was the director of the New York Symphony Orchestra and conducted the world premiere performances of various works, including Geo ...

who, at the request of General John J. Pershing, commanding general of the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

(AEF), was entrusted the mission of reorganizing the bands of the Army, and had founded a school for bandmasters at the general headquarters of the AEF at Chaumont, France.

''America'' parted from ''George Washington'' and ''Von Steuben'' on 2 September and reached the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

on the 7th. Following drydocking, voyage repairs, and the embarkation of another contingent of troops, she arrived at Hoboken on the morning of the 17th. Three days later, she cleared the port, in company with ''Agamemnon'', bound for France on her ninth transatlantic voyage cycle.

Influenza epidemic

By this time, aninfluenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

epidemic was raging in the United States and Europe and had taken many lives. From its first appearance, special precautions had been taken on board ''America'' to protect both her ship's company and passengers. The sanitary measures had succeeded in keeping all in the ship healthy. However, this group of soldiers—who had come on board at Boston where the epidemic had been raging—brought the flu with them. As a result, 997 cases of flu and pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

occurred among the embarked soldiers during the passage to France, while fifty six cases broke out among the 940 men in the crew. Before the transport completed the round-trip voyage and arrived back at Hoboken, New Jersey, fifty three soldiers and two sailors had died on board. This comparatively low death rate (some ships lost considerably more men) can be attributed to the efforts of the ship's doctors and corpsmen, as well as the embarked units' medical personnel. Forty two of the fifty three deaths among the troops occurred during the time the ship lay at anchor at Brest from 29 September to 2 October.

The day after reaching home, ''America'' commenced coaling and loading stores in preparation for her 10th voyage and completed the task at 02:25 on 15 October. In addition, the ship was thoroughly fumigated to rid her of influenza germs. By that time, all troops had been embarked and the ship loaded, ready to sail for France soon thereafter.

Sinking and salvage

At 04:45, ''America'', without warning, began listing to port and kept heeling over as water entered through the coaling ports which were still open although the coaling process had been completed over two hours before. Soon after the ship began listing, the general alarm was sounded throughout the ship. In the troop spaces, the urgent sound of that alarm awakened the sleeping soldiers who sought egress from their compartments. Soldiers and sailors both streamed up ladders topside; others jumped for safety on the coal barges, still alongside, or down cargo nets to the dock. Sentries on deck fired their rifles in the air as they sought to warn their comrades on board.

At 04:45, ''America'', without warning, began listing to port and kept heeling over as water entered through the coaling ports which were still open although the coaling process had been completed over two hours before. Soon after the ship began listing, the general alarm was sounded throughout the ship. In the troop spaces, the urgent sound of that alarm awakened the sleeping soldiers who sought egress from their compartments. Soldiers and sailors both streamed up ladders topside; others jumped for safety on the coal barges, still alongside, or down cargo nets to the dock. Sentries on deck fired their rifles in the air as they sought to warn their comrades on board.

Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

Edward C. S. Baker, the executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

, in the absence of Captain Zeno E. Briggs whose wife was seriously ill, directed Lieutenant John G. M. Stone, the gunnery officer, to clear the lower compartments. Stone was credited with leading to safety many soldiers and sailors who had been blindly plunging through various compartments (the flooding of the engine rooms had put the lights out aboard the ship) seeking some means of escape.

Rear Admiral Gleaves arrived at the dock soon after the ship sank, the water covering her main deck, to see personally what had happened to one of the largest transports in the Cruiser-Transport Force. Before the day was out, a court of inquiry began meeting to determine what had happened. Over the ensuing days, salvage efforts continued, including the removal of guns, cargo, and other equipment, as well as the search for the six men unaccounted for at muster. Eventually, the bodies of all, four soldiers and two sailors, were recovered. Divers worked continuously, closing open ports (almost all on "G" deck had been left open to allow the air to be cleared of the smell of disinfectants that had been used to cleanse and fumigate the compartments). She was raised and refloated on 21 November 1918, 10 days after the

Rear Admiral Gleaves arrived at the dock soon after the ship sank, the water covering her main deck, to see personally what had happened to one of the largest transports in the Cruiser-Transport Force. Before the day was out, a court of inquiry began meeting to determine what had happened. Over the ensuing days, salvage efforts continued, including the removal of guns, cargo, and other equipment, as well as the search for the six men unaccounted for at muster. Eventually, the bodies of all, four soldiers and two sailors, were recovered. Divers worked continuously, closing open ports (almost all on "G" deck had been left open to allow the air to be cleared of the smell of disinfectants that had been used to cleanse and fumigate the compartments). She was raised and refloated on 21 November 1918, 10 days after the armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

was signed ending World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. On 16 December, ''America'' was towed by 10 tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

s to the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

where she remained undergoing the extensive repairs occasioned by her sinking, well into February 1919.

While unable to determine definitely what had caused the sinking, the court of inquiry posited that water had entered the ship through open ports on "G" deck. An unofficial opinion held by some officers in the case maintained that the listing of the ship had been caused by mud suction, that the ship, to some extent, had been resting on the bottom, and that, when the tide rose, one side was released before the other.

After the war

Foreshadowing the Magic Carpet operations which would follow

Foreshadowing the Magic Carpet operations which would follow World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, a massive effort was made after the armistice to return the veterans of the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

to the United States. ''America'' participated in this effort which commenced on 21 February when the ship sailed for Brest, France, and concluded on 15 September. Between that time, the transport made eight round-trip voyages to Brest. The western terminus was Hoboken, New Jersey for seven voyages and Boston, Massachusetts for the other. Among the 46,823 passengers whom she brought back from France was Benedict Crowell, the Assistant Secretary of War who was embarked in the ship during her last voyage as a Navy transport.

USAT ''America'' (1919 to 1920)

On 22 September 1919, shortly after ''America'' completed that voyage, the Chief of the Army Transportation Service (ATS), Brigadier GeneralFrank T. Hines

Frank Thomas Hines (April 11, 1879 – April 3, 1960) was a United States military officer and head of the U.S. Veterans Bureau (later Veteran's Administration) from 1923 to 1945. Hines took over as head of the Veterans Bureau after a series of s ...

, contacted the Navy, expressing the Army's desire to acquire ''America'' and ''Mount Vernon'' ". . . to transport certain passengers from Europe to the United States." Four days later, ''America'' was decommissioned while alongside Pier 2, Hoboken, and transferred to the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

. Capt. J. Ford, ATS, simultaneously assumed command of the ship.

USAT ''America'' conducted two more voyages between Hoboken and Brest. Trouble highlighted her second voyage under the Army colors. An unruly crew at Brest on 4 December 1919 prompted Capt. Ford to appeal to the colonel commanding Base Section Number Five, at Brest, for an armed guard, fearing mutiny. Apparently, the Army matter was resolved, for the ship reached Hoboken five days before Christmas 1919.

On 20 December, the day ''America'' was scheduled to arrive at the port of debarkation, arrangements were made to turn ''America'' and two other Army transports, and , over to the USSB for operation while they were being carried on the roll of the Army Transport Reserve. However, before the year 1919 was out, events in a faraway land caused a temporary change in this plan.

A glance back at developments on the Eastern Front during

USAT ''America'' conducted two more voyages between Hoboken and Brest. Trouble highlighted her second voyage under the Army colors. An unruly crew at Brest on 4 December 1919 prompted Capt. Ford to appeal to the colonel commanding Base Section Number Five, at Brest, for an armed guard, fearing mutiny. Apparently, the Army matter was resolved, for the ship reached Hoboken five days before Christmas 1919.

On 20 December, the day ''America'' was scheduled to arrive at the port of debarkation, arrangements were made to turn ''America'' and two other Army transports, and , over to the USSB for operation while they were being carried on the roll of the Army Transport Reserve. However, before the year 1919 was out, events in a faraway land caused a temporary change in this plan.

A glance back at developments on the Eastern Front during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

may clarify the transport's new mission. When it mobilized for war, the Austria-Hungarian Empire conscripted countless Czechs. Upon reaching the front, these men, long restive under Austrian rule, deserted in droves and then were organized by Russian officers to fight their former masters. However, the war sapped away the strength of the Russian government more rapidly than it weakened those of the other belligerents and thus encouraged rebellion. One revolution early in 1917 toppled the Czar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the t ...

and a second in the autumn placed a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

regime in power. The communist leaders quickly negotiated with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

the treaty of Brest-Litovsk which took Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

out of the war and allowed the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

to concentrate their resources on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

.

This development left the Czech Legion—some 40,000 strong—stranded in Russia with hostile forces separating it from its still oppressed homeland. Allied leaders hoped to use these dedicated and highly disciplined fighting men to bolster their own embattled troops on the western front and encouraged the Czechs to move east on the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, ...

where they could be embarked in transports for passage to France.

However, before this could be accomplished, the Czechs, who had tried to remain aloof from Russia's internal struggles, incurred the hostility and opposition of the Bolsheviks and found themselves involuntarily embroiled in the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

as something of a rallying point for various counterrevolutionary forces. Moreover, prior to the armistice, some factions within the Allied powers hoped that the Czechs might be used to reopen the fighting on the eastern front against the Central Powers. As a result, some two tempestuous years passed before the entire Czech legion finally assembled at Vladivostok ready for evacuation.

On 30 December 1919, a representative of the War Department contacted the Chief of Naval Operations, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations stating that Army transports ''America'' and ''President Grant'' "were to go on a long secret trip as soon as possible." He emphasized the urgency of the situation and requested that the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

give the highest priority to repairing the two transports for sea. The Navy carried out the repairs, including drydocking, at top speed and completed the work by 21 January 1920. Two days later, ''America'' shifted to Hoboken and sailed for the Pacific on 30 January.

''America'' reached San Francisco on 16 February and remained there a week before clearing the Golden Gate on 23 February. Sailing via Cavite, in the Philippines (where she tarried from 15 to 23 March), and Nagasaki, Nagasaki, Nagasaki, Japan, ''America'' reached Vladivostok soon thereafter.

While the transport had been on her way to the Russian far eastern port, the situation in Russia had deteriorated markedly. Bolshevik armies had driven the White Movement, White Russian forces back into Siberia, and the collapse of the White government, headed by Admiral Alexander Kolchak, sounded the death knell of the western attempt to intervene in the civil war. By the time the ship arrived at Vladivostok, the evacuation of the Czech legion was well underway. Adding to the number of people to be transported were the several hundred wives and children of Czech soldiers, since some 1,600 men had married during the period of the "Czech Anabasis" in Russia. By 20 May, the last of the Czech troops had arrived in Vladivostok. Five days later, the United States consul in that port estimated that some 13,200 remained to be repatriated in the five or six remaining transports, which included ''America''. Ultimately, and ''America'' reached Trieste on 8 August, disembarking their contingents of Czechs without incident.

SS ''America'' (1921 to 1931)

For ''America'', further service awaited with the United States Lines. Reconditioned to resume her place in the transatlantic passenger trade, she commenced her maiden voyage as an American passenger liner on 22 June 1921, sailing for Bremen, Germany, with stops at Plymouth, England, and Cherbourg, France, en route.

For the next eleven years, ''America'' plied the Atlantic, ranking third only in size to the United States Lines' ships SS Leviathan, ''Leviathan'' and ''SS George Washington, George Washington''—the latter running mate from the Cruiser-Transport Force days. In June 1924, the ''America'' transported the United States Olympic team to Cherbourg, France, for the summer games held in Paris, making the return leg to New York in August. On two occasions, ''America'' figured in the headlines.

For ''America'', further service awaited with the United States Lines. Reconditioned to resume her place in the transatlantic passenger trade, she commenced her maiden voyage as an American passenger liner on 22 June 1921, sailing for Bremen, Germany, with stops at Plymouth, England, and Cherbourg, France, en route.

For the next eleven years, ''America'' plied the Atlantic, ranking third only in size to the United States Lines' ships SS Leviathan, ''Leviathan'' and ''SS George Washington, George Washington''—the latter running mate from the Cruiser-Transport Force days. In June 1924, the ''America'' transported the United States Olympic team to Cherbourg, France, for the summer games held in Paris, making the return leg to New York in August. On two occasions, ''America'' figured in the headlines.

Fire and rescue

The first occurred on 10 March 1926, as the ship lay moored in the yard of the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company inNewport News, Virginia

Newport News () is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 186,247. Located in the Hampton Roads region, it is the 5th most populous city in Virginia and 140th most populous city in the U ...

awaiting final trials after being reconditioned. A fire broke out on board only a day before she was to be returned to her owner. The fire burned for seven hours and eventually consumed most of the passenger cabins as it swept the ship nearly from stem to stern, causing an estimated $2,000,000 worth of damage, equivalent to $33,027,796.61 in today's money.

The second newsworthy incident began on 22 January 1929 when ''America''—then commanded by Captain George Fried—was steaming from France to New York. As she battled her way through a major storm, the liner picked up distress signals from the Italian steamship, ''Florida''. Guided by her radio direction finder, the American ship homed in on the Italian and, late the following afternoon, finally sighted the endangered vessel through light snow squalls. Taking a position off ''Florida's'' weather beam, ''America'' lowered her number one Lifeboat (shipboard), lifeboat, commanded by her Chief Officer, Harry Manning, with a crew of eight men.

After the boat had been rowed to within of the listing ''Florida'', Manning had a line thrown across to the eager crew of the distressed freighter One by one, the 32 men from the Italian ship came across the rope. By the time the last of them, the ship's captain, had been dragged on board the pitching lifeboat, the winds had reached gale force, with violent snow and rain squalls, with a high, rough, sea running. Then, via ladders, ropes, cargo nets, and two homemade breeches buoys, sailors on board ''America'' brought up ''Florida's'' survivors, until all 32 were safe and sound. Finally, they pulled their shipmates from the rescue party back on board. Chief Officer Manning was brought up last. Captain Fried felt that it was highly dangerous to attempt to hoist the number one lifeboat on board and, rather than risk lives, ordered it cut adrift.

The second newsworthy incident began on 22 January 1929 when ''America''—then commanded by Captain George Fried—was steaming from France to New York. As she battled her way through a major storm, the liner picked up distress signals from the Italian steamship, ''Florida''. Guided by her radio direction finder, the American ship homed in on the Italian and, late the following afternoon, finally sighted the endangered vessel through light snow squalls. Taking a position off ''Florida's'' weather beam, ''America'' lowered her number one Lifeboat (shipboard), lifeboat, commanded by her Chief Officer, Harry Manning, with a crew of eight men.

After the boat had been rowed to within of the listing ''Florida'', Manning had a line thrown across to the eager crew of the distressed freighter One by one, the 32 men from the Italian ship came across the rope. By the time the last of them, the ship's captain, had been dragged on board the pitching lifeboat, the winds had reached gale force, with violent snow and rain squalls, with a high, rough, sea running. Then, via ladders, ropes, cargo nets, and two homemade breeches buoys, sailors on board ''America'' brought up ''Florida's'' survivors, until all 32 were safe and sound. Finally, they pulled their shipmates from the rescue party back on board. Chief Officer Manning was brought up last. Captain Fried felt that it was highly dangerous to attempt to hoist the number one lifeboat on board and, rather than risk lives, ordered it cut adrift.

Inactivated

In 1931 and 1932, after two modern ships, SS Washington, ''Washington'' and , had been added to the fleet of the United States Lines, ''America'' was laid up at Point Patience, Maryland, on the Patuxent River, along with her consorts of days gone by – ''George Washington'', ''Agamemnon'', and ''Mount Vernon'', all veterans of the old Cruiser-Transport Force. For the next eight years, ''America'' were placed in reserve.USAT ''Edmund B. Alexander'' (1940 to 1949)

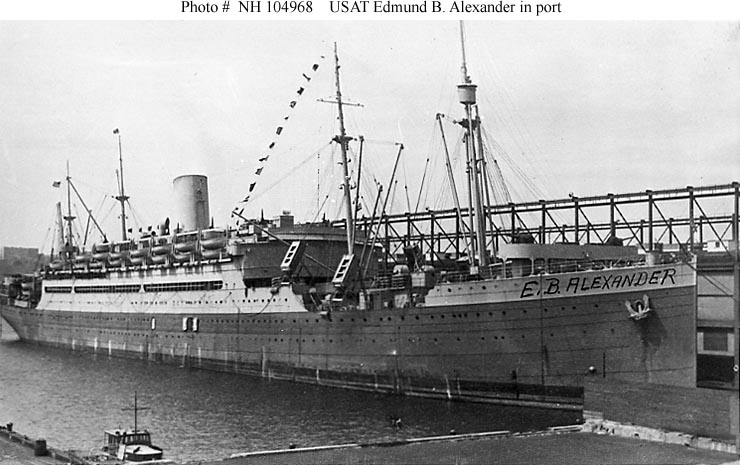

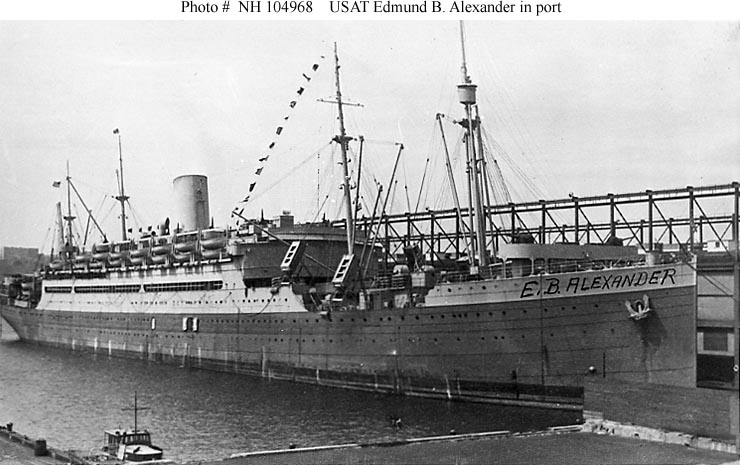

When the United States transferred fifty surplus destroyers to the British government in the destroyers for bases agreement during the fall of 1940, two of the acquisitions were bases at Argentia, Newfoundland and the future Fort Pepperrell at St. John's, Newfoundland, but no barracks existed at St. John's for troops, so an interim solution had to be provided.

As a result, in October 1940, ''America'' was acquired by the

When the United States transferred fifty surplus destroyers to the British government in the destroyers for bases agreement during the fall of 1940, two of the acquisitions were bases at Argentia, Newfoundland and the future Fort Pepperrell at St. John's, Newfoundland, but no barracks existed at St. John's for troops, so an interim solution had to be provided.

As a result, in October 1940, ''America'' was acquired by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

and towed to Baltimore, Maryland, to undergo rehabilitation in the Bethlehem Steel Company yard. Earmarked for use as a floating barracks, the ship would provide quarters for 1,200 troops – the garrison for the new base at St. John's. Still a coal-burner, the ship could only make a shadow of her former speed – 10 knots.

With the ship's new role came a new name. Possibly to avoid confusion with the liner ''SS America (1940), America'', then building at Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, renamed United States Army Transport (USAT) ''Edmund B. Alexander'', in keeping with the Army's policy of naming its oceangoing transports for famous general officers. This name honored Brevet Brigadier General Edmund Brooke Alexander.

''Edmund B. Alexander'' sailed from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...