Train Of Tomorrow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' was an American demonstrator train built as a collaboration between

The ''Train of Tomorrow'''s direct antecedents were the original American lightweight passenger trains, most notably the Burlington's original ''

The ''Train of Tomorrow'''s direct antecedents were the original American lightweight passenger trains, most notably the Burlington's original ''

According to multiple sources, the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s dome cars were the brainchild of GM vice president and EMD general manager Cyrus Osborn, who conceived the idea while riding in an F-unit in the

According to multiple sources, the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s dome cars were the brainchild of GM vice president and EMD general manager Cyrus Osborn, who conceived the idea while riding in an F-unit in the  After the final design ideas were derived from the sketches, GM's Styling Section began building a scale model of a four-car train (each car was long), built of metal, plastic, and wood and featuring 175 painted clay figures of people and even tiny details such as dinner knives and cigarette packs. The dining car alone featured 1,100 objects. After being completed, the model was unveiled in a former

After the final design ideas were derived from the sketches, GM's Styling Section began building a scale model of a four-car train (each car was long), built of metal, plastic, and wood and featuring 175 painted clay figures of people and even tiny details such as dinner knives and cigarette packs. The dining car alone featured 1,100 objects. After being completed, the model was unveiled in a former

Design of the ''Train of Tomorrow'' began in 1944, as a collaboration between

Design of the ''Train of Tomorrow'' began in 1944, as a collaboration between

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' was pulled by a largely stock EMD E7A that was given road number 765 because it was built for order number 765. It featured two , V12 GM

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' was pulled by a largely stock EMD E7A that was given road number 765 because it was built for order number 765. It featured two , V12 GM

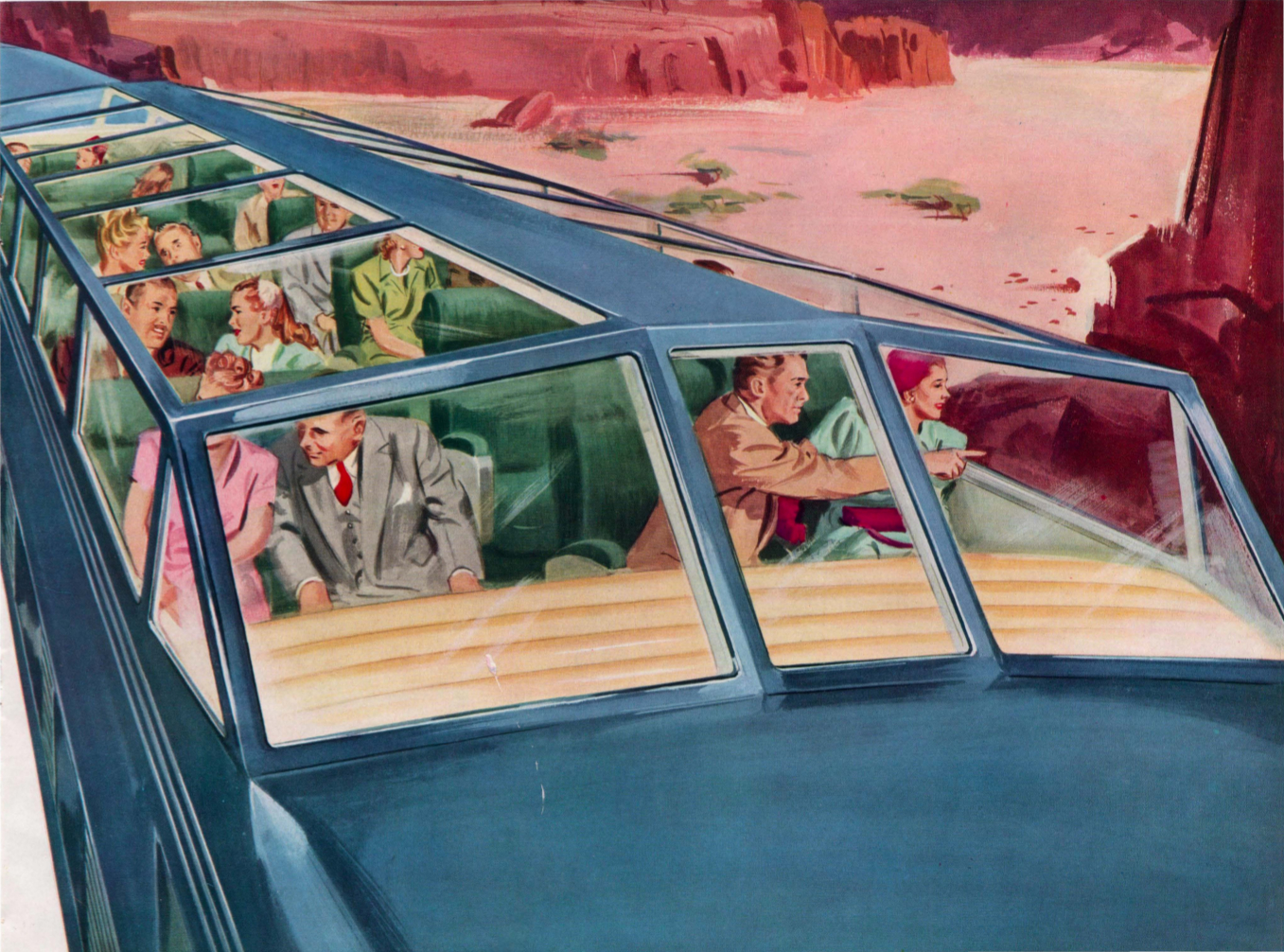

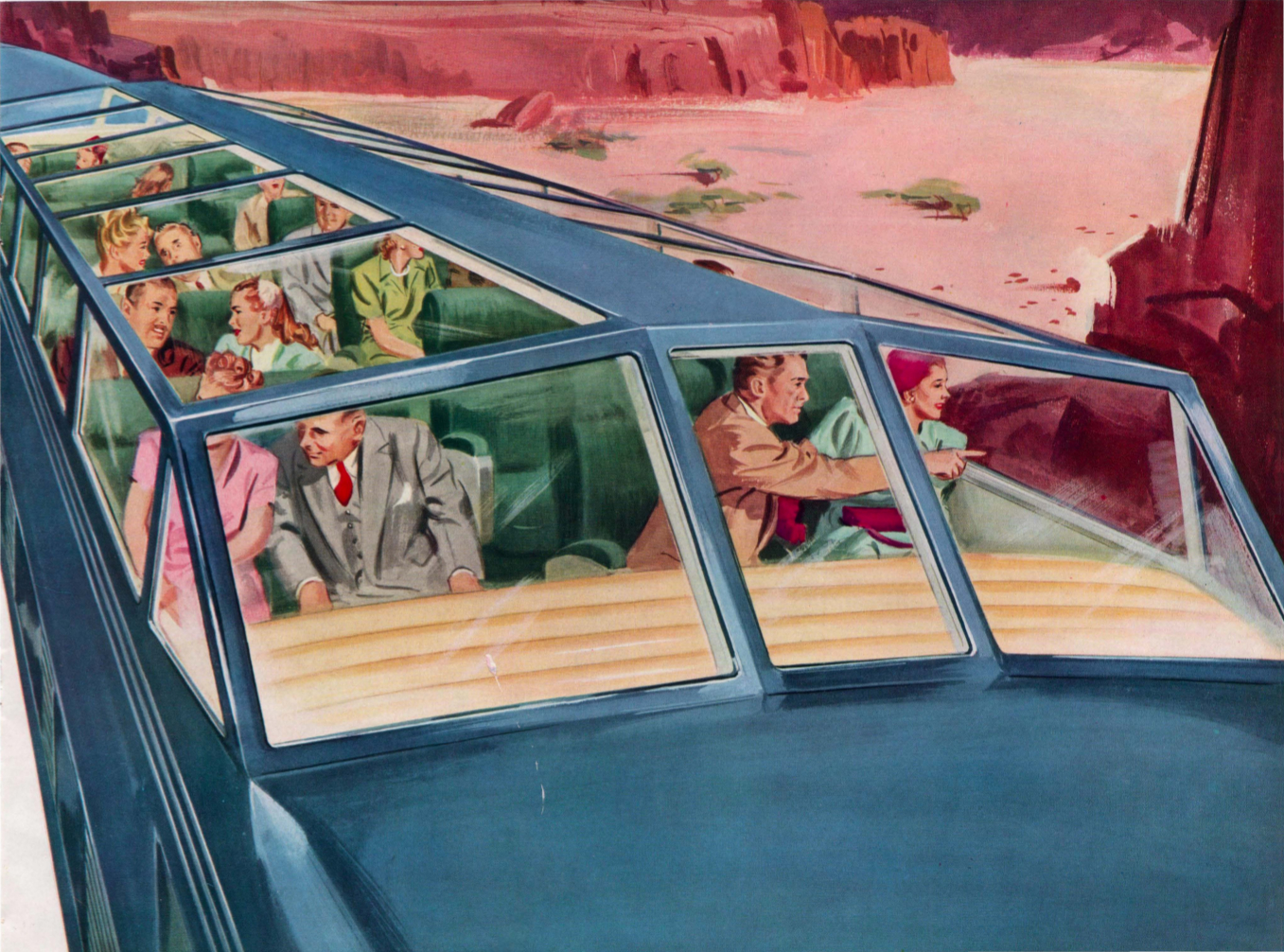

Chair car ''Star Dust'' (Pullman plan number 7555) seated 72 passengers. It provided seating on three levels, including in its Astra-Dome and three semiprivate rooms beneath the dome in addition to on its main level. Its two main level sections, the forward coach section and the rear coach section, seated 16 and 12 passengers each, respectively. The dome sat 24 people, while two of the three semiprivate rooms could accommodate 7 while the third could seat 6. The seats in the car could rotate, allowing them to face the direction of travel or allow two pairs of seats to face each other, allowing families to interact with each other during a trip. The semiprivate rooms were separated from the passageway by shoulder-high partitions, while these three rooms were divided from each other by fluted (or ribbed) glass called Securit Linex Glass that, while it transmitted light, provided some privacy by impairing the ability to see through it. The first and third semiprivate rooms each had two pairs of chairs and a couch that could accommodate three people, while the second contained two of the three-person couches instead. Under the stairway of the dome, the car contained various supplies and necessities, including a

Chair car ''Star Dust'' (Pullman plan number 7555) seated 72 passengers. It provided seating on three levels, including in its Astra-Dome and three semiprivate rooms beneath the dome in addition to on its main level. Its two main level sections, the forward coach section and the rear coach section, seated 16 and 12 passengers each, respectively. The dome sat 24 people, while two of the three semiprivate rooms could accommodate 7 while the third could seat 6. The seats in the car could rotate, allowing them to face the direction of travel or allow two pairs of seats to face each other, allowing families to interact with each other during a trip. The semiprivate rooms were separated from the passageway by shoulder-high partitions, while these three rooms were divided from each other by fluted (or ribbed) glass called Securit Linex Glass that, while it transmitted light, provided some privacy by impairing the ability to see through it. The first and third semiprivate rooms each had two pairs of chairs and a couch that could accommodate three people, while the second contained two of the three-person couches instead. Under the stairway of the dome, the car contained various supplies and necessities, including a

Dining car ''Sky View'' (Pullman plan number 7556) could accommodate 52 people in three different dining rooms. It sat 24 in its main dining room, 18 in its dome, and 10 in its reserve private dining room beneath the dome. It was both the first dome diner to be built and the first diner of any kind with an all-electric kitchen. At its front end, the car featured the crew's

Dining car ''Sky View'' (Pullman plan number 7556) could accommodate 52 people in three different dining rooms. It sat 24 in its main dining room, 18 in its dome, and 10 in its reserve private dining room beneath the dome. It was both the first dome diner to be built and the first diner of any kind with an all-electric kitchen. At its front end, the car featured the crew's

Sleeping car ''Dream Cloud'' (Pullman plan number 4128) accommodated passengers in two drawing rooms, three compartments, and eight duplex

Sleeping car ''Dream Cloud'' (Pullman plan number 4128) accommodated passengers in two drawing rooms, three compartments, and eight duplex

Lounge-observation car ''Moon Glow'' (Pullman plan number 7557) could accommodate 68 people in its dome, rear observation lounge, and two cocktail lounges. Half of the seats in the car were movable, enabling passengers to adapt its seating to their needs. The first of the three lounges on the car, at its forward end, was called the upper lounge, the second, which was located under the dome, was called the lower lounge, and the rear lounge at the end of the car was called the observation lounge. The front end of the car also housed a men's and a women's lavatory. The upper lounge featured a bar, a large sofa, built-in seats, three booths with

Lounge-observation car ''Moon Glow'' (Pullman plan number 7557) could accommodate 68 people in its dome, rear observation lounge, and two cocktail lounges. Half of the seats in the car were movable, enabling passengers to adapt its seating to their needs. The first of the three lounges on the car, at its forward end, was called the upper lounge, the second, which was located under the dome, was called the lower lounge, and the rear lounge at the end of the car was called the observation lounge. The front end of the car also housed a men's and a women's lavatory. The upper lounge featured a bar, a large sofa, built-in seats, three booths with

While ''Star Dust'', ''Dream Cloud'', and ''Sky View'' were ultimately scrapped in 1964 at McCarty's Scrap Yard in Pocatello, ''Moon Glow'' survived. In 1969, after purchasing the lot next to McCarty's Scrap Yard and opening Henry's Scrap Metals on it, Henry Fernandez purchased ''Moon Glow'' from McCarty's for $2,500, without knowing its history or the story of the ''Train of Tomorrow''. He intended to restore it and convert it into an office, although it would sit unrestored on his property for 18 years. After members of the

While ''Star Dust'', ''Dream Cloud'', and ''Sky View'' were ultimately scrapped in 1964 at McCarty's Scrap Yard in Pocatello, ''Moon Glow'' survived. In 1969, after purchasing the lot next to McCarty's Scrap Yard and opening Henry's Scrap Metals on it, Henry Fernandez purchased ''Moon Glow'' from McCarty's for $2,500, without knowing its history or the story of the ''Train of Tomorrow''. He intended to restore it and convert it into an office, although it would sit unrestored on his property for 18 years. After members of the

General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

(GM) and Pullman-Standard

The Pullman Company, founded by George Pullman, was a manufacturer of railroad cars in the mid-to-late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, during the boom of railroads in the United States. Through rapid late-19th century ...

between 1945 and 1947. It was the first new train to consist entirely of dome car

A dome car is a type of railway passenger car that has a glass dome on the top of the car where passengers can ride and see in all directions around the train. It also can include features of a coach, lounge car, dining car, sleeping car or obse ...

s, which were the brainchild of GM vice president and Electro-Motive Division

Progress Rail Locomotives, doing business as Electro-Motive Diesel (EMD), is an American manufacturer of diesel-electric locomotives, locomotive products and diesel engines for the rail industry. The company is owned by Caterpillar through its sub ...

(EMD) general manager Cyrus Osborn, who conceived the idea while riding in either an F-unit or a caboose

A caboose is a crewed North American railroad car coupled at the end of a freight train. Cabooses provide shelter for crew at the end of a train, who were formerly required in switching and shunting, keeping a lookout for load shifting, dam ...

in the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

in Glenwood Canyon

Glenwood Canyon is a rugged scenic canyon in western Colorado in the United States. Its walls climb as high as above the Colorado River. It is the largest such canyon on the Upper Colorado. The canyon, which has historically provided the route ...

, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

. After GM built a 45-foot (14 m) scale model

A scale model is a physical model which is geometrically similar to an object (known as the prototype). Scale models are generally smaller than large prototypes such as vehicles, buildings, or people; but may be larger than small prototypes ...

of the train for $101,772 ($ in dollars) and displayed it to 350 officials from 55 different Class I railroads in 1945, the ''Train of Tomorrow'' was built by Pullman-Standard between October 1946 and May 1947.

The train consisted of four cars: a chair car (''Star Dust''), a dining car

A dining car (American English) or a restaurant car (British English), also a diner, is a railroad passenger car that serves meals in the manner of a full-service, sit-down restaurant.

It is distinct from other railroad food service cars that do ...

(''Sky View''), a sleeping car

The sleeping car or sleeper (often ) is a railway passenger car that can accommodate all passengers in beds of one kind or another, for the purpose of sleeping. George Pullman was the American innovator of the sleeper car.

The first such cars ...

(''Dream Cloud''), and a lounge- observation car (''Moon Glow''), all featuring "Astra-Domes". It was pulled by a largely stock EMD E7A. Its dining car, ''Sky View'', was the first dome diner to be built and the first diner of any kind with an all-electric kitchen. The train was constructed with low-alloy, high-tensile steel and Thermopane

Insulating glass (IG) consists of two or more glass window panes separated by a space to reduce heat transfer across a part of the building envelope. A window with insulating glass is commonly known as double glazing or a double-paned window, ...

glass for its domes and windows. Although GM never publicly stated the total price of the ''Train of Tomorrow'', contemporary sources estimated it at between $1 million and $1.5 million.

After being christened at a dedication ceremony in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

on May 28, 1947, the ''Train of Tomorrow'' embarked on a barnstorming tour of the United States and Canada that lasted for 28 months, covered , and visited 181 cities and towns. During its tour, the train was ridden or toured by over 5.7 million people, and was seen by an estimated 20 million people. After its tour was completed on October 30, 1949, the train was sold to the Union Pacific

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pac ...

for $500,000, and its four cars were put into service between Portland and Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

on June 18, 1950. The cars were retired from service between 1961 and 1965, and all but one were eventually scrapped. ''Moon Glow'' sat in a scrap yard for almost two decades before being discovered by the National Railway Historical Society

The National Railway Historical Society (NRHS) is a non-profit organization established in 1935 in the United States to promote interest in, and appreciation for the historical development of railroads. It is headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsyl ...

(NRHS), who purchased and transported it to the Ogden Union Station Museum, where it is undergoing restoration.

Background

The ''Train of Tomorrow'''s direct antecedents were the original American lightweight passenger trains, most notably the Burlington's original ''

The ''Train of Tomorrow'''s direct antecedents were the original American lightweight passenger trains, most notably the Burlington's original ''Pioneer Zephyr

The ''Pioneer Zephyr'' is a diesel-powered trainset built by the Budd Company in 1934 for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (CB&Q), commonly known as the Burlington Route. The trainset was the second internal combustion-powered streaml ...

'' (1934), the Santa Fe's lightweight ''Super Chief

The ''Super Chief'' was one of the named passenger trains and the flagship of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. The streamliner claimed to be "The Train of the Stars" because of the various celebrities it carried between Chicago, Ill ...

'' (1937), and the Illinois Central

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also c ...

's ''Panama Limited

The ''Panama Limited'' was a passenger train operated from 1911 to 1971 between Chicago, Illinois, and New Orleans, Louisiana. The flagship train of the Illinois Central Railroad, it took its name from the Panama Canal, which in 1911 was three yea ...

'' (1942).

The Burlington's construction of the first modern dome car

A dome car is a type of railway passenger car that has a glass dome on the top of the car where passengers can ride and see in all directions around the train. It also can include features of a coach, lounge car, dining car, sleeping car or obse ...

in 1945 also preceded the construction of the ''Train of Tomorrow.'' Ralph Budd

Ralph (pronounced ; or ,) is a male given name of English, Scottish and Irish origin, derived from the Old English ''Rædwulf'' and Radulf, cognate with the Old Norse ''Raðulfr'' (''rað'' "counsel" and ''ulfr'' "wolf").

The most common forms ...

was one of the first people to see the sketches of the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s Astra-Dome cars, and was inspired by them to create the first modern dome car for the Burlington in 1945, two years before the ''Train of Tomorrow'' was unveiled. Prior to the Burlington dome, there were a number of precursors: T. J. McBride of Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

received a patent for a dome sleeper in 1891, Coeur d'Alene Railway & Navigation Company chief engineer R. C. Riblet designed an electric dome car at roughly the same time, the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canad ...

built four observation dome cars based on McBride's design between 1902 and 1906 (which were in service only until 1909), and the Wichita Falls and Southern Railroad

Wichita ( ) may refer to:

People

*Wichita people, a Native American tribe

*Wichita language, the language of the tribe

Places in the United States

* Wichita, Kansas, a city

* Wichita County, Kansas, a county in western Kansas (city of Wichita i ...

build a "combination parlor-coach-baggage-observatory-dome car" in the 1930s.

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' was also a response to over seven years of a relative lack of development and construction of railroad equipment caused by World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Even during the first half of 1947, all American railroads combined ordered fewer than 100 new passenger cars

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarded as t ...

, according to Robert R. Young

Robert Ralph Young (February 14, 1897 – January 25, 1958) was an American financier and industrialist. He is best known for leading the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway and the New York Central Railroad during and after World War II. He was a b ...

. In contrast, by the end of 1948, after the beginning of the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s promotional tour, there were over 1,800 passenger cars on order, although some of them had been ordered as early as 1944, but had not yet been delivered.

Genesis and design

According to multiple sources, the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s dome cars were the brainchild of GM vice president and EMD general manager Cyrus Osborn, who conceived the idea while riding in an F-unit in the

According to multiple sources, the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s dome cars were the brainchild of GM vice president and EMD general manager Cyrus Osborn, who conceived the idea while riding in an F-unit in the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

in Glenwood Canyon

Glenwood Canyon is a rugged scenic canyon in western Colorado in the United States. Its walls climb as high as above the Colorado River. It is the largest such canyon on the Upper Colorado. The canyon, which has historically provided the route ...

, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

. According to Osborn himself, however, it was actually a similar ride in the "cupola of the caboose

A caboose is a crewed North American railroad car coupled at the end of a freight train. Cabooses provide shelter for crew at the end of a train, who were formerly required in switching and shunting, keeping a lookout for load shifting, dam ...

that gave me the idea." After Osborn was reassured by EMD engineers that a dome car that would not be more limited in height clearance than a caboose could be built, he turned his idea over to Harley Earl

Harley Jarvis Earl (November 22, 1893 – April 10, 1969) was an American automotive designer and business executive. He was the initial designated head of design at General Motors, later becoming vice president, the first top executive ever ...

and the General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

(GM) Styling Section in Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

. The Styling Section then collected feedback on contemporary passenger car design from its designers and railroad passengers before committing to a design process anticipated by Earl to take 90 days and cost US$25,000, which resulted in 1,500 sketches and 100 final design ideas.

Cadillac

The Cadillac Motor Car Division () is a division of the American automobile manufacturer General Motors (GM) that designs and builds luxury vehicles. Its major markets are the United States, Canada, and China. Cadillac models are distributed ...

showroom in Oak Park, Illinois

Oak Park is a village in Cook County, Illinois, adjacent to Chicago. It is the 29th-most populous municipality in Illinois with a population of 54,583 as of the 2020 U.S. Census estimate. Oak Park was first settled in 1835 and later incorporated ...

, where it was displayed with a custom-built Western mountain scene backdrop illuminated with stage lighting

Stage lighting is the craft of lighting as it applies to the production of theater, dance, opera, and other performance arts.

. From February 21 to June 23, 1945, the model was shown to 350 officials from 55 different Class I railroads, most notably Ralph Budd of the Burlington, who was so moved by the display that he almost immediately ordered the passenger car ''Silver Alchemy'' (No. 4714) be converted into a dome and renamed ''Silver Dome''.

By November 1945, the model had cost $101,772, more than four times its budget, but before the ''Train of Tomorrow'' made its debut, 49 dome cars were on loan with the Budd Company

The Budd Company was a 20th-century metal fabricator, a major supplier of body components to the automobile industry, and a manufacturer of stainless steel passenger rail cars, airframes, missile and space vehicles, and various defense products ...

alone. GM allowed any carbuilder to freely use its designs without license

A license (or licence) is an official permission or permit to do, use, or own something (as well as the document of that permission or permit).

A license is granted by a party (licensor) to another party (licensee) as an element of an agreeme ...

s or royalties

A royalty payment is a payment made by one party to another that owns a particular asset, for the right to ongoing use of that asset. Royalties are typically agreed upon as a percentage of gross or net revenues derived from the use of an asset o ...

, as it "saw the program not only as a research project to stimulate interest in new car design and construction but also as a way to encourage railroads to order new cars with GM railroad-related products on-board." After being revised, the model was repeatedly displayed at auto show

An auto show, also known as a motor show or car show, is a public exhibition of current automobile models, debuts, concept cars, or out-of-production classics. It is attended by automotive industry representatives, dealers, auto journalists a ...

s and other GM exhibitions through 1955, including at Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry and at Motorama

The General Motors Motorama was an auto show staged by GM from 1949 to 1961. These automobile extravaganzas were designed to whet public appetite and boost automobile sales with displays of fancy concept cars and other special or halo models. Mo ...

, before last being seen in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

in 1955 at a ceremony honoring Osborn.

Development and construction

Design of the ''Train of Tomorrow'' began in 1944, as a collaboration between

Design of the ''Train of Tomorrow'' began in 1944, as a collaboration between General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American Multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and ...

(GM) and Pullman-Standard. According to author Brian Solomon, the train "was strictly intended as an innovation showcase, and...the automotive manufacturer had no interest in building its own passenger trains." According to a contemporary ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energy ...

'' magazine article, its development cost approximately $1.5 million. GM had no less than five of its divisions involved with the train: the Electro-Motive Division

Progress Rail Locomotives, doing business as Electro-Motive Diesel (EMD), is an American manufacturer of diesel-electric locomotives, locomotive products and diesel engines for the rail industry. The company is owned by Caterpillar through its sub ...

(EMD) built its E7A locomotive, the Detroit Diesel Division and the Delco Products Division collaborated on the train's generating equipment, the Frigidaire Division built its air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C or AC, is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior environment (sometimes referred to as 'comfort cooling') and in some cases also strictly controlling ...

system, the Hyatt Bearings Division built its anti-friction, journal-box bearings, and GM's Styling Division concentrated on its interior design

Interior design is the art and science of enhancing the interior of a building to achieve a healthier and more aesthetically pleasing environment for the people using the space. An interior designer is someone who plans, researches, coordin ...

. GM did not, however, foray into the field of building passenger railroad cars, until its introduction of the Aerotrain Aerotrain may refer to:

* Aérotrain, a hovercraft train developed in France

* AeroTrain, an tiltrotor aircraft proposed by Karem Aircraft

* Aerotrain (GM), a passenger train built by General Motors Electro-Motive Division

* AeroTrain (Washington ...

a decade later.

According to authors Gary Dolzall and Stephen Dolzall, the train was intended to be the "ultimate train for the postwar era" and an "embodiment of the latest passenger train design". Author Frank Richter termed it the "latest state-of-the-art in passenger trains", while fellow author William L. Bird described it as "GM's traveling exhibit of Diesel-powered passenger comfort". According to GM president Harlow Curtice

Harlow Herbert Curtice (August 15, 1893 – November 3, 1962) was an American automotive industry executive who led General Motors (GM) from 1953 to 1958. As GM's chief, he was selected as Man of the Year for 1955 by '' Time'' magazine.

Curtice ...

, the ''Train of Tomorrow'' was an experiment in both design and mechanics, similar to its automotive concept car

A concept car (also known as a concept vehicle, show vehicle or prototype) is a car made to showcase new styling and/or new technology. They are often exhibited at motor shows to gauge customer reaction to new and radical designs which may or ...

s such as the Le Sabre, XP-300, and Y-Job.

GM's Executive Committee formally committed to building the ''Train of Tomorrow'' in fall 1945. After soliciting proposals from multiple car manufacturers, GM signed a contract with Pullman-Standard on November 6, 1945. The cars were all to be built to Association of American Railroads

The Association of American Railroads (AAR) is an industry trade group representing primarily the major freight Rail transport, railroads of North America (Canada, Mexico and the United States). Amtrak and some regional Commuter rail in North Am ...

(AAR) standards, but GM did not supply Pullman-Standard with blueprints or specifications for building the cars, instead concentrating on their interior design. EMD did supply inspectors to Pullman-Standard who had the power to approve or reject changes to the design and workmanship in the construction of the cars, however. After creating a final set of drawings, specifications, and full-scale wooden mockups, Pullman-Standard made arrangements with the War Production Board

The War Production Board (WPB) was an agency of the United States government that supervised war production during World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt established it in January 1942, with Executive Order 9024. The WPB replaced the Su ...

to obtain steel for the train, but settled for flat glass

Plate glass, flat glass or sheet glass is a type of glass, initially produced in plane form, commonly used for windows, glass doors, transparent walls, and windscreens. For modern architectural and automotive applications, the flat glass is s ...

instead of curved glass, because the latter was still required for the American war effort. GM also decided not to charge royalties on the use of the dome car concept by any car builders. Construction of the ''Train of Tomorrow'' began in October 1946, and took until May 17, 1947.

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' consisted of four cars: a chair car (''Star Dust''), a dining car

A dining car (American English) or a restaurant car (British English), also a diner, is a railroad passenger car that serves meals in the manner of a full-service, sit-down restaurant.

It is distinct from other railroad food service cars that do ...

(''Sky View''), a sleeping car

The sleeping car or sleeper (often ) is a railway passenger car that can accommodate all passengers in beds of one kind or another, for the purpose of sleeping. George Pullman was the American innovator of the sleeper car.

The first such cars ...

(''Dream Cloud''), and a lounge- observation car (''Moon Glow''), all featuring "Astra-Domes". The domes on the ''Train of Tomorrow'' each measured in length, in width, and in height, and sat 24 people apiece. The domes were made with Thermopane

Insulating glass (IG) consists of two or more glass window panes separated by a space to reduce heat transfer across a part of the building envelope. A window with insulating glass is commonly known as double glazing or a double-paned window, ...

glass, developed by Libbey-Owens-Ford

The Libbey-Owens-Ford Company (LOF) was a producer of flat glass for the automotive and building products industries both for original equipment manufacturers and for replacement use. The company's headquarters and main factories were located in T ...

, and consisted of a plate-glass exterior layer and a shatterproof interior layer with a pocket of air between to provide thermal and sound insulation. The Thermopane glass was also resistant to heat and glare-free. The low profile of the domes allowed them to operate on most mainlines, including those with low clearances, such as on the Boston & Albany. Like the dome windows, the rest of the windows in the train were made of Thermopane and "designed for maximum viewing of the passing scenery." They ranged in size from for sleeping car ''Dream Cloud'''s roomette

A roomette is a type of sleeping car compartment in a railroad passenger train. The term was first used in North America, and was later carried over into Australia and New Zealand. Roomette rooms are relatively small, and were originally ...

s to in ''Dream Cloud'''s two drawing rooms and the chair car ''Star Dust''.

Including the domes, the total height of the cars "from rail to roof" was . Each car measured in length, and weighed when unloaded. Each of the cars was built using low-alloy, high-tensile steel, and constructed using the welded-girder technique. The trucks

A truck or lorry is a motor vehicle designed to transport cargo, carry specialized payloads, or perform other utilitarian work. Trucks vary greatly in size, power, and configuration, but the vast majority feature body-on-frame construction ...

on the train's passenger cars were developed from locomotive trucks, with outside-mounted swing hangers spaced apart (instead of the typical practice of mounting them apart on the inside of the trucks) and rolling bearing journal box

A bogie or railroad truck holds the wheel sets of a rail vehicle.

Axlebox

An ''axle box'', also known as a ''journal box'' in North America, is the mechanical subassembly on each end of the axles under a railway wagon, coach or locomotive; ...

es, which helped to improve truck alignment, smooth the train's ride, and reduce body roll on curves from to .

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' had a blue-green and silver livery described by author Keith Lovegrove as having an "astral theme", consisting of a "wide belt of stainless steel

Stainless steel is an alloy of iron that is resistant to rusting and corrosion. It contains at least 11% chromium and may contain elements such as carbon, other nonmetals and metals to obtain other desired properties. Stainless steel's r ...

wrapping the midriff of the predominantly dark-blue train". The blue-green exterior paint was a high-gloss enamel Dulux paint produced by DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

, and the train's underframe

An underframe is a framework of wood or metal carrying the main body structure of a railway vehicle, such as a locomotive, carriage or wagon.

See also

* Chassis

* Headstock

* Locomotive bed

* Locomotive frame

A locomotive frame is the struct ...

was painted black.

All the cars on the train featured Seamloc carpet made by Goodall Fabrics, in a palette of colors known as "Araby" (consisting of the colors Araby Peach, Dove Taupe, Jade, Lido Sand, Persian Rose, Silver Grey, and Turquoise). The hard flooring and wall covering materials used were Es Es and V-Board, both plastic products created by the United States Rubber Company

The company formerly known as the United States Rubber Company, now Uniroyal, is an American manufacturer of tires and other synthetic rubber-related products, as well as variety of items for military use, such as ammunition, explosives, chemic ...

, in the colors blue, brown, coral, gray-blue, gray-green, gray-tan, green, purple, and red. The train's interior paint was a semigloss from DuPont, its pull-down shades were manufactured by the Adams and Westlake Company and matched to the exterior colors of the train, while its "decorative but nonfunctional drapes" were supplied by Goodall Fabrics and backed with sateen

Sateen is a fabric made using a satin weave structure, but made with spun yarns instead of filament.

The sheen and softer feel of sateen is produced through the satin weave structure. Warp yarns are floated over weft yarns, for example four ov ...

from Lusskey, White, and Coolidge. The train featured couch seats from Haywood-Wakefield in chair car ''Star Dust'' and all of its domes except that of dining car ''Sky View''; they were of tubular metal construction with sponge rubber seat and back cushions that could both rotate and recline, and each also had movable footrests and armrests with ash receivers. Those in the chair car had high backs, while those in the domes had low backs that measured only from the seat cushion to the top of the headrest.

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' featured numerous additional amenities, including Diesel auxiliary power unit

An auxiliary power unit (APU) is a device on a vehicle that provides energy for functions other than propulsion. They are commonly found on large aircraft and naval ships as well as some large land vehicles. Aircraft APUs generally produce 115& ...

s ( head-end power) on each car, an all-electric kitchen, fluorescent light

A fluorescent lamp, or fluorescent tube, is a low-pressure mercury-vapor gas-discharge lamp that uses fluorescence to produce visible light. An electric current in the gas excites mercury vapor, which produces short-wave ultraviolet ligh ...

fixtures throughout the train, a public address system

A public address system (or PA system) is an electronic system comprising microphones, amplifiers, loudspeakers, and related equipment. It increases the apparent volume (loudness) of a human voice, musical instrument, or other acoustic sound sou ...

, and even a radiotelephone

A radiotelephone (or radiophone), abbreviated RT, is a radio communication system for conducting a conversation; radiotelephony means telephony by radio. It is in contrast to ''radiotelegraphy'', which is radio transmission of telegrams (messa ...

, which during demonstrations placed a call to the ocean liner RMS ''Queen Elizabeth'' while at sea. Each car on the train also had a and a air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C or AC, is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior environment (sometimes referred to as 'comfort cooling') and in some cases also strictly controlling ...

unit.

In all, the train could carry a capacity of 216 passengers. It measured in overall length, and weighted a total of when unloaded and roughly when fully loaded. GM never publicly stated the total price of the ''Train of Tomorrow'', although contemporary sources estimated it at between $1 million and $1.5 million.

EMD E7A locomotive no. 765

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' was pulled by a largely stock EMD E7A that was given road number 765 because it was built for order number 765. It featured two , V12 GM

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' was pulled by a largely stock EMD E7A that was given road number 765 because it was built for order number 765. It featured two , V12 GM Diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-cal ...

s mated to direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or ev ...

(DC) generators that powered traction motor

A traction motor is an electric motor used for propulsion of a vehicle, such as locomotives, electric or hydrogen vehicles, elevators or electric multiple unit.

Traction motors are used in electrically powered rail vehicles ( electric multip ...

s on each of the locomotive's trucks

A truck or lorry is a motor vehicle designed to transport cargo, carry specialized payloads, or perform other utilitarian work. Trucks vary greatly in size, power, and configuration, but the vast majority feature body-on-frame construction ...

, which both had three axles. In total, the locomotive was rated at , and could operate at . The prime movers had a power range between 275 and 800 rpm. Behind the prime movers, the locomotive had a steam generator A Steam generator is a device used to boil water to create steam. More specifically, it may refer to:

*Boiler (steam generator), a closed vessel in which water is heated under pressure

*Monotube steam generator

*Supercritical steam generator or Ben ...

used to heat passenger cars. The cab of the E7A featured two swivel chairs, one for the engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

and the other for the fireman

A firefighter is a first responder and rescuer extensively trained in firefighting, primarily to extinguish hazardous fires that threaten life, property, and the environment as well as to rescue people and in some cases or jurisdictions also ...

, and controls purposely designed to be similar to those used on steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, oil or, rarely, wood) to heat water in the loco ...

s. The cab was also soundproofed and heated during the winter.

The locomotive measured in length and weighed when fully loaded. Its exterior featured the GM logo on its side, "set in a graphic representation of a shooting star

Shooting star refers to a meteor.

Shooting star may also refer to:

Film, television, and theater

* ''Shooting Star'' (2015 film), a 2015 Bulgarian short film

* ''Shooting Star'' (2020 film), a 2020 Canadian short film

* ''Shooting Stars'' ...

", and another GM logo with the words "''Train of Tomorrow''" on its nose. According to author Ric Morgan, it was "just a standard Diesel locomotive" aside from these unique graphics and cosmetic corrugated stainless steel added to match the exterior design of the cars. It had a skirt on its front with doors providing access to the front coupler.

According to Pullman-Standard public relations consultant E. Preston Calvert, Pullman-Standard built the shell for the locomotive, and while GM encouraged it to build more shells in the future, "it did not want to get into locomotive building." While still unfinished, the locomotive was publicly displayed at the Fisher Ternstedt plant in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the United States, U.S. U.S. state, state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along ...

on April 25, 1947, just a month before the beginning of the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s tour.

Chair car ''Star Dust''

Chair car ''Star Dust'' (Pullman plan number 7555) seated 72 passengers. It provided seating on three levels, including in its Astra-Dome and three semiprivate rooms beneath the dome in addition to on its main level. Its two main level sections, the forward coach section and the rear coach section, seated 16 and 12 passengers each, respectively. The dome sat 24 people, while two of the three semiprivate rooms could accommodate 7 while the third could seat 6. The seats in the car could rotate, allowing them to face the direction of travel or allow two pairs of seats to face each other, allowing families to interact with each other during a trip. The semiprivate rooms were separated from the passageway by shoulder-high partitions, while these three rooms were divided from each other by fluted (or ribbed) glass called Securit Linex Glass that, while it transmitted light, provided some privacy by impairing the ability to see through it. The first and third semiprivate rooms each had two pairs of chairs and a couch that could accommodate three people, while the second contained two of the three-person couches instead. Under the stairway of the dome, the car contained various supplies and necessities, including a

Chair car ''Star Dust'' (Pullman plan number 7555) seated 72 passengers. It provided seating on three levels, including in its Astra-Dome and three semiprivate rooms beneath the dome in addition to on its main level. Its two main level sections, the forward coach section and the rear coach section, seated 16 and 12 passengers each, respectively. The dome sat 24 people, while two of the three semiprivate rooms could accommodate 7 while the third could seat 6. The seats in the car could rotate, allowing them to face the direction of travel or allow two pairs of seats to face each other, allowing families to interact with each other during a trip. The semiprivate rooms were separated from the passageway by shoulder-high partitions, while these three rooms were divided from each other by fluted (or ribbed) glass called Securit Linex Glass that, while it transmitted light, provided some privacy by impairing the ability to see through it. The first and third semiprivate rooms each had two pairs of chairs and a couch that could accommodate three people, while the second contained two of the three-person couches instead. Under the stairway of the dome, the car contained various supplies and necessities, including a water cooler

A water dispenser, known as water cooler (if used for cooling only), is a machine that dispenses and often also cools or heats up water with a refrigeration unit. It is commonly located near the restroom due to closer access to plumbing. A dra ...

, a coat locker, and a jump seat

In aviation, a jump seat or jumpseat is an auxiliary seat for individuals—other than normal passengers—who are not operating the aircraft. In general, the term 'jump seat' can also refer to a seat in any type of vehicle which can fold up out ...

for the porter

Porter may refer to:

Companies

* Porter Airlines, Canadian regional airline based in Toronto

* Porter Chemical Company, a defunct U.S. toy manufacturer of chemistry sets

* Porter Motor Company, defunct U.S. car manufacturer

* H.K. Porter, Inc., ...

. The car had a set of men's and women's lavatories at either end, with the pair at the vestibule

Vestibule or Vestibulum can have the following meanings, each primarily based upon a common origin, from early 17th century French, derived from Latin ''vestibulum, -i n.'' "entrance court".

Anatomy

In general, vestibule is a small space or cavity ...

end being complemented by men's and women's dressing room

A changing-room, locker-room, (usually in a sports, theater, or staff context) or changeroom (regional use) is a room or area designated for changing one's clothes. Changing-rooms are provided in a semi-public situation to enable people to ch ...

s. Also at the vestibule end, the car had luggage compartments on both sides of the aisle that could be accessed from either inside or outside the train.

Dining car ''Sky View''

Dining car ''Sky View'' (Pullman plan number 7556) could accommodate 52 people in three different dining rooms. It sat 24 in its main dining room, 18 in its dome, and 10 in its reserve private dining room beneath the dome. It was both the first dome diner to be built and the first diner of any kind with an all-electric kitchen. At its front end, the car featured the crew's

Dining car ''Sky View'' (Pullman plan number 7556) could accommodate 52 people in three different dining rooms. It sat 24 in its main dining room, 18 in its dome, and 10 in its reserve private dining room beneath the dome. It was both the first dome diner to be built and the first diner of any kind with an all-electric kitchen. At its front end, the car featured the crew's toilet

A toilet is a piece of sanitary hardware that collects human urine and feces, and sometimes toilet paper, usually for disposal. Flush toilets use water, while dry or non-flush toilets do not. They can be designed for a sitting position popu ...

, an icemaker

An icemaker, ice generator, or ice machine may refer to either a consumer device for making ice, found inside a home freezer; a stand-alone appliance for making ice, or an industrial machine for making ice on a large scale. The term "ice machin ...

, and food storage accessible from the kitchen. The kitchen covered roughly the first third of the car, and it entirely constructed of stainless steel

Stainless steel is an alloy of iron that is resistant to rusting and corrosion. It contains at least 11% chromium and may contain elements such as carbon, other nonmetals and metals to obtain other desired properties. Stainless steel's r ...

and featured a pan floor made of the anti-slip material Martex. The kitchen featured a wide array of electric appliances, including a frozen food locker, a General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable ene ...

(GE) broiler

A broiler is any chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') that is bred and raised specifically for meat production. Most commercial broilers reach slaughter weight between four and six weeks of age, although slower growing breeds reach slaugh ...

, a GE garbage disposal unit

A garbage disposal unit (also known as a waste disposal unit, garbage disposer, garburator etc.) is a device, usually electrically powered, installed under a kitchen sink between the sink's drain and the trap. The disposal unit shreds food ...

, three GE ranges

In the Hebrew Bible and in the Old Testament, the word ranges has two very different meanings.

Leviticus

In Leviticus 11:35, ranges probably means a cooking furnace for two or more pots, as the Hebrew word here is in the dual number; or perhaps ...

, a Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/ Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

dishwasher

A dishwasher is a machine that is used to clean dishware, cookware, and cutlery automatically. Unlike manual dishwashing, which relies heavily on physical scrubbing to remove soiling, the mechanical dishwasher cleans by spraying hot water, ty ...

, a hot table, a water heater, a Hotpoint

Hotpoint is a British brand of domestic appliances. Ownership of the brand is split between American company Whirlpool, which has the rights in Europe, and Chinese company Haier, which has the rights in the Americas through its purchase of GE ...

fry kettle, a KitchenAid

KitchenAid is an American home appliance brand owned by Whirlpool Corporation. The company was started in 1919 by The Hobart Manufacturing Company to produce stand mixers; the "H-5" was the first model introduced. The company faced competition a ...

mixer

Mixer may refer to:

Electronics

* DJ mixer, a type of audio mixing console used by disc jockeys

* Electronic mixer, electrical circuit for adding signal voltages

* Frequency mixer, electrical circuit that creates new frequencies from two signals ...

, three oven

upA double oven

A ceramic oven

An oven is a tool which is used to expose materials to a hot environment. Ovens contain a hollow chamber and provide a means of heating the chamber in a controlled way. In use since antiquity, they have been use ...

s, plate warmers, and Pullman-Standard refrigerator

A refrigerator, colloquially fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to its external environment so th ...

s with mechanics made by Frigidaire. The kitchen also featured long counter spaces, a pastry board, a sink, and storage lockers.

Under the dome, and adjoining to the kitchen, was the car's pantry

A pantry is a room or cupboard where beverages, food, and sometimes dishes, household cleaning products, linens or provisions are stored within a home or office. Food and beverage pantries serve in an ancillary capacity to the kitchen.

Etymol ...

, where salads and desserts were made and where the waiters

Waiting staff (British English), waitstaff (North American English), waiters (male) / waitresses (female), or servers (North American English), are those who work at a restaurant, a diner, or a bar and sometimes in private homes, attending ...

picked up food for passengers. The pantry also featured a dumbwaiter

A dumbwaiter is a small freight elevator or lift intended to carry food. Dumbwaiters found within modern structures, including both commercial, public and private buildings, are often connected between multiple floors. When installed in restau ...

that connected to the dining room in the dome. Also beneath the dome was the reserve private dining room, a small dining area designed to accommodate small groups or families. It had two tables with two-person benches on either side, as well as two loose chairs that could be added to the ends of the tables to give each a capacity of five people, or ten for the entire room.

In the dome, an off-center aisle allowed for four-person booths on one side and two-person booths on the other. At the front end of the dome was a waiter's station that included the dumbwaiter along with a Cory coffee warmer, an ice well, a refrigerator, a sink, and a toaster

A toaster is a small electric appliance that uses radiant heat to brown sliced bread into toast.

Types

Pop-up toaster

In pop-up or automatic toasters, a single vertical piece of bread is dropped into a slot on the top of the toaste ...

. At the base of the staircase to the dome was the steward's room as well as a locker for supplies and a desk. The main dining room also featured an off-center aisle, dividing square tables with four chairs on one side from triangular tables with two chairs on the other. The rear end of the car included a crew locker, an electrical locker, and a linen locker.

Sleeping car ''Dream Cloud''

Sleeping car ''Dream Cloud'' (Pullman plan number 4128) accommodated passengers in two drawing rooms, three compartments, and eight duplex

Sleeping car ''Dream Cloud'' (Pullman plan number 4128) accommodated passengers in two drawing rooms, three compartments, and eight duplex roomette

A roomette is a type of sleeping car compartment in a railroad passenger train. The term was first used in North America, and was later carried over into Australia and New Zealand. Roomette rooms are relatively small, and were originally ...

s, and also had 24 seats in its dome. It could sleep 20 passengers if all its beds were filled. All of its berths were mounted lengthwise in regards to the car. At the front of the car was a general use toilet. Next came drawing room E, which featured a large sofa facing the window that folded down into a bed at night, two more upper berths that folded down from the walls, and two chairs near the window. The drawing room also had a small lavatory known as an "annex". The next room, drawing room D, was a mirror image of drawing room E, although the two were decorated differently.

Under the dome roughly in the center of the car were the three compartments, which each had (like the drawing rooms) a window-facing sofa. Compartment C had two lower berths and a single chair, as well as a sanitary column in the corner with a lid-capped "hopper" (toilet) and a fold-down sink. Similarly to drawing rooms E and D, compartments C and D were mirror images of each other, again the only difference being in terms of decor. Compartment A shared its layout with compartment C, although during the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s tour it was used as the train's office.

The dome in the car was similar to the other domes on the train, although all of its seats were reserved for passengers booked on ''Dream Cloud''. Behind the staircase to the dome was the porter's section, containing a seat and a folding upper berth as well as an annunciator

An annunciator panel, also known in some aircraft as the Centralized Warning Panel (CWP) or Caution Advisory Panel (CAP), is a group of lights used as a central indicator of status of equipment or systems in an aircraft, industrial process, buildin ...

to alert the porter to sleeping car passengers requesting service and supplies such as a first aid

First aid is the first and immediate assistance given to any person with either a minor or serious illness or injury, with care provided to preserve life, prevent the condition from worsening, or to promote recovery. It includes initial i ...

kit. Behind the porter's section were the car's eight duplex roomettes, consisting of two upper roomettes and two lower roomettes on each side of the aisle. The lower roomettes were at floor level, while their upper counterparts were two steps above. The roomettes each featured a seat, a small one-person sofa, a sanitary column with hopper like the ones in the compartments, and one berth. Upper berths were slightly larger than lower berths, and the former had berths that folded out of the wall while the latter had pull-out sliding berths that were stored under the adjacent upper roomette. At the end of the car were two lockers that held clean linen and soiled linen as well as folding chairs and tables.

After being constructed, ''Dream Cloud'' was taken to Altoona, Pennsylvania

Altoona is a city in Blair County, Pennsylvania. It is the principal city of the Altoona Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). The population was 43,963 at the time of the 2020 Census, making it the eighteenth most populous city in Pennsylvania. T ...

, and subjected to jacking, load, and squeeze testing.

Lounge-observation car ''Moon Glow''

Lounge-observation car ''Moon Glow'' (Pullman plan number 7557) could accommodate 68 people in its dome, rear observation lounge, and two cocktail lounges. Half of the seats in the car were movable, enabling passengers to adapt its seating to their needs. The first of the three lounges on the car, at its forward end, was called the upper lounge, the second, which was located under the dome, was called the lower lounge, and the rear lounge at the end of the car was called the observation lounge. The front end of the car also housed a men's and a women's lavatory. The upper lounge featured a bar, a large sofa, built-in seats, three booths with

Lounge-observation car ''Moon Glow'' (Pullman plan number 7557) could accommodate 68 people in its dome, rear observation lounge, and two cocktail lounges. Half of the seats in the car were movable, enabling passengers to adapt its seating to their needs. The first of the three lounges on the car, at its forward end, was called the upper lounge, the second, which was located under the dome, was called the lower lounge, and the rear lounge at the end of the car was called the observation lounge. The front end of the car also housed a men's and a women's lavatory. The upper lounge featured a bar, a large sofa, built-in seats, three booths with Formica

''Formica'' is a genus of ants of the family Formicidae, commonly known as wood ants, mound ants, thatching ants, and field ants. ''Formica'' is the type genus of the Formicidae, and of the subfamily Formicinae. The type species of genus ' ...

tabletops, and smoking stands also capable of holding beverages.

The lower lounge also featured a built-in sofa and chairs, but they were finished with honey-colored leather that complemented the dark green carpet to give it "the appearance of a bar in a private club." Unlike the upper lounge, the lower lounge did not have any windows. The lower lounge also featured a bar created by Angelo Colonna that contained a refrigerator and an ice cube maker, glassware cabinets, and a cigar and cigarette humidor. Like in the kitchen in the dining car, the bar's floor was a "metal pan" finished in anti-slip Martex. Both of these lounge areas were separated from the passageway by half-wall partitions.

The dome of ''Moon Glow'', like the domes in the chair car and sleeping car, accommodated 24 people. At the base of the stairs to the dome was a built-in writing desk area, which contained cubicles for writing supplies, the public address system, an intratrain telephone, and a "train-to-shore" radiotelephone that could be operated whenever the train was within of the 30 largest metropolitan areas in the United States. The radiotelephone was powered by a six-volt battery similar to automotive batteries that was mounted under the car, and it used an "piano wire" antenna mounted to the roof, both of which were supplied by Illinois Bell

Illinois Bell Telephone Company, LLC is the Bell Operating Company serving Illinois. It is owned by AT&T through AT&T Teleholdings, formerly Ameritech.

Their headquarters are at 225 West Randolph St., Chicago, IL. After the 1984 Bell System ...

.

The observation lounge at the end of the car had an oval-shaped appearance, with a rounded end in its ceiling lighting cove matching the rounded shape of the end of the car. The observation lounge included nine movable lounge chairs, as well as three sofas: two kidney-shaped ones (seating two and three people, respectively) that could also be moved, and a third large, curved, built-in sofa. The sofas and chairs were turned toward the windows while the train was in motion, but during tours they were turned inward. There was a table in front of the built-in sofa, and smoking stands throughout, like those in the other lounges. The windows in the observation lounge were large, and almost appeared to be pillarless, but small pillars were hidden behind drapes. The windows also had shades. The very end of the observation car contained a "cockpit area" with built-in end table

A table is an item of furniture with a raised flat top and is supported most commonly by 1 or 4 legs (although some can have more), used as a surface for working at, eating from or on which to place things. Some common types of table are the ...

s and built-in seats, and (hidden behind a door) a back-up and signal valve that could be used to control the train while it was being operated in reverse.

Operation

Testing and dedication

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' made its first test run on theMonon Railroad

The Monon Railroad , also known as the Chicago, Indianapolis, and Louisville Railway from 1897 to 1971, was an American railroad that operated almost entirely within the state of Indiana. The Monon was merged into the Louisville and Nashville Ra ...

, between Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

and Wallace Junction in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

. The train also made its official debut on the Monon on May 26, 1947, carrying company officials, members of the media and invited guests from Dearborn Station

Dearborn Station (also referred to as Polk Street Depot) was, beginning in the late 1800s, one of six intercity train stations serving downtown Chicago, Illinois. It remained in operation until May 1, 1971. Built in 1883, it is located at ...

in Chicago to the French Lick Springs Hotel

The French Lick Springs Hotel, a part of the French Lick Resort complex, is a major resort hotel in Orange County, Indiana. The historic hotel in the national historic district at French Lick was initially known as a mineral spring health spa ...

in French Lick, Indiana

French Lick is a town in French Lick Township, Orange County, Indiana. The population was 1,807 at the time of the 2010 census. In November 2006, the French Lick Resort Casino, the state's tenth casino in the modern legalized era, opened, drawing ...

. After spending the night at the hotel in French Lick, and hosting 758 people who toured the train while there, the train and its passengers returned to Chicago the next day. The train's public debut also served as a shakedown of sorts, with several brake tests being made on the return journey. The return to Chicago was marred by a collision with an automobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarded ...

at a grade crossing

A level crossing is an intersection where a railway line crosses a road, path, or (in rare situations) airport runway, at the same level, as opposed to the railway line crossing over or under using an overpass or tunnel. The term a ...

, although it resulted in no injuries and no serious damage to the locomotive.

On May 28 the ''Train of Tomorrow'' was dedicated at a ceremony held at the Palmer House Hotel

The Palmer House – A Hilton Hotel is a historic hotel in Chicago's Loop area. It is a member of the Historic Hotels of America program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The Palmer House was the city's first hotel with elevators, ...

that featured Chicago mayor

The mayor of Chicago is the chief executive of city government in Chicago, Illinois, the third-largest city in the United States. The mayor is responsible for the administration and management of various city departments, submits proposals and ...

Martin H. Kennelly

Martin Henry Kennelly (August 11, 1887 – November 29, 1961) was an American politician and businessman. He served as the 47th Mayor of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois from April 15, 1947 until April 20, 1955. Kennelly was a member of the Democra ...

and GM's Charles F. Kettering

Charles Franklin Kettering (August 29, 1876 – November 25, 1958) sometimes known as Charles Fredrick Kettering was an American inventor, engineer, businessman, and the holder of 186 patents.

For the list of patents issued to Kettering, see, Le ...

, Cyrus Osborn, and Alfred P. Sloan

Alfred Pritchard Sloan Jr. ( ; May 23, 1875February 17, 1966) was an American business executive in the automotive industry. He was a long-time president, chairman and CEO of General Motors Corporation. Sloan, first as a senior executive and l ...

. Approximately 1,000 GM and Pullman-Standard executives, businessmen and politicians attended the ceremony, during which Kettering's granddaughter, Jane, christening the train with a bottle of champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, ...

. Following this ceremony, GM opened the train to the public at Soldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since ...

between May 29 and June 1, during which around 50,000 people saw it.

Demonstration tour

The ''Train of Tomorrow'' departed on its demonstration tour on June 2, 1947, barnstorming the United States and Canada for 28 months and covering , despite the tour initially being slated to last only 6 months. In the words of author Brian Solomon, the intention of the tour was to "promote Diesel-electric technology and new concepts in passenger railroading". According to Dolzall and Dolzall, the chief purpose of the ''Train of Tomorrow'''s tour was to generate public interest and to sell orders for GM Diesel-electric locomotives and Pullman-Standardpassenger cars

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarded as t ...

.

The tour was made possible by volunteers and employees of GM, its various divisions, Pullman-Standard, and the various railroads over which the train ran, and it was dependent on advance agents to coordinate logistics and public relations personnel to promote the train. The barnstorming tour included special runs for the press, tours for groups of children as well as the general public, and open houses at GM plants for employees and their families. GM employees on the tour were accommodated in local hotels, while the Pullman crew staffing the train itself slept in a remodeled heavyweight Pullman-Standard car nicknamed the ''Blue Goose'' that accompanied the ''Train of Tomorrow''. Pullman was responsible for staffing the train as well as cleaning and maintaining it, while EMD was in charge of supervising its maintenance. On a typical day on the road, the train was cleaned and prepared during the morning, then local VIPs (such as politicians) and GM executives were invited to have lunch on the train's dining car, and public tours would begin at 1 or 2 pm and run until 9 pm. During tours, the public would typically enter the train through the rear of lounge-observation car ''Moon Glow'' and exit through chair car ''Star Dust''. Throughout the tour, the train's interior was decorated with anthurium

''Anthurium'' (; Schott, 1829) is a genus of about 1,000Mantovani, A. and T. E. Pereira. (2005)''Anthurium'' (section ''Urospadix''; subsection ''Flavescentiviridia'').''Rodriguesia'' 56(88), 145–60. species of flowering plants, the largest ...

s, rare flowers that were sourced from a single florist and flown in.

On June 3, 1947, the ''Train of Tomorrow'' departed on its "1st Eastern Tour", stopping for multiple days in Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

; Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020, the city had a population of 38,497.

; Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

; Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital city, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georgia, Fulton County, the mos ...

; Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

; Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

, Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the List of cities in Ohio, sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County, Ohio, Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County, Ohio, Greene County. The 2020 United S ...

, and Oxford, Ohio

Oxford is a city in Butler County, Ohio, United States. The population was 23,035 at the 2020 census. A college town, Oxford was founded as a home for Miami University and lies in the southwestern portion of the state approximately northwest ...

, before returning to Chicago on August 11. On August 20, it departed on its "2nd Eastern Tour", stopping for multiple days at Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S ...

, and Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, before August 31. Between September 1 and September 8, it visited Eastern Canada

Eastern Canada (also the Eastern provinces or the East) is generally considered to be the region of Canada south of the Hudson Bay/ Strait and east of Manitoba, consisting of the following provinces (from east to west): Newfoundland and Labra ...

for the first time when it was exhibited at the Canadian National Exhibition

The Canadian National Exhibition (CNE), also known as The Exhibition or The Ex, is an annual event that takes place at Exhibition Place in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, on the third Friday of August leading up to and including Canadian Labour Day ...

in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

and visited McKinnon Industries in St. Catharines, Ontario

St. Catharines is the largest city in Canada's Niagara Region and the sixth largest urban area in the province of Ontario. As of 2016, it has an area of , 136,803 residents, and a metropolitan population of 406,074. It lies in Southern Ontario ...

. On September 8, the train reentered the United States, and stopped for multiple days in Rochester

Rochester may refer to:

Places Australia

* Rochester, Victoria

Canada

* Rochester, Alberta

United Kingdom

*Rochester, Kent

** City of Rochester-upon-Medway (1982–1998), district council area

** History of Rochester, Kent

** HM Prison ...

, Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

, and Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York Cit ...

; Boston, Massachusetts; New York City, New York

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, before returning to Chicago on October 17. From October 24 to 26, the train was exhibited at the EMD plant in La Grange, Illinois

''(the barn)''

, nickname =

, motto = ''Tradition & Pride – Moving Forward''

, anthem = ''My La Grange'' by Jimmy Dunne

, image_map = File:Cook County Illinois Incorporated and Unincorporated areas La Grange Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 26 ...

, but on October 25 it made a trip to Ann Arbor, Michigan

Ann Arbor is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan and the county seat of Washtenaw County. The 2020 census recorded its population to be 123,851. It is the principal city of the Ann Arbor Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all ...

, for an Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

trip to the football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly ...

game between the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

and the University of Michigan