Theosophy and literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

According to some

When

When

Yeats became interested in Theosophy in 1884, after reading '' Esoteric Buddhism'' by Alfred Percy Sinnett. A copy of the book was sent him by his aunt, Isabella Varley. Together with his friends George Russell and Charles Johnston, he established the

Yeats became interested in Theosophy in 1884, after reading '' Esoteric Buddhism'' by Alfred Percy Sinnett. A copy of the book was sent him by his aunt, Isabella Varley. Together with his friends George Russell and Charles Johnston, he established the

According to scholar Brendan French, novels by authors in the Rosicrucian tradition are a path to the "conceptual domain" of Blavatsky. He notes that ''

According to scholar Brendan French, novels by authors in the Rosicrucian tradition are a path to the "conceptual domain" of Blavatsky. He notes that ''

In 1887, Blavatsky published the article "The Signs of the Times", in which she discussed the growing influence of Theosophy in literature. She listed some novels that can be categorized as Theosophical and mystical literature, including ''Mr Isaacs'' (1882) and ''Zoroaster'' (1885) by Francis Marion Crawford; ''The Romance of Two Worlds'' (1886) by

In 1887, Blavatsky published the article "The Signs of the Times", in which she discussed the growing influence of Theosophy in literature. She listed some novels that can be categorized as Theosophical and mystical literature, including ''Mr Isaacs'' (1882) and ''Zoroaster'' (1885) by Francis Marion Crawford; ''The Romance of Two Worlds'' (1886) by

* Mme Tamvaco in a novel by Rosa Campbell Praed ''Affinities''

* Image of Urur in a novel by

* Mme Tamvaco in a novel by Rosa Campbell Praed ''Affinities''

* Image of Urur in a novel by

List of the journal publications by/about Yeats

{{Theosophy series Theosophy Helena Blavatsky Fantasy literature Science fiction literature Literary criticism Religious studies

literary

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

and religious studies scholars, modern Theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

had a certain influence on contemporary literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

, particularly in forms of genre fiction

Genre fiction, also known as popular fiction, is a term used in the book-trade for fictional works written with the intent of fitting into a specific literary genre, in order to appeal to readers and fans already familiar with that genre.

A num ...

such as fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction involving Magic (supernatural), magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and sometimes inspired by mythology and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy ...

and science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

. Researchers claim that Theosophy has significantly influenced the Irish literary renaissance

The Irish Literary Revival (also called the Irish Literary Renaissance, nicknamed the Celtic Twilight) was a flowering of Irish literary talent in the late 19th and early 20th century. It includes works of poetry, music, art, and literature.

O ...

of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, notably in such figures as W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

and G. W. Russell.

Classic writers and Theosophists

Dostoevsky

In November 1881,Helena Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, uk, Олена Петрівна Блаватська, Olena Petrivna Blavatska (; – 8 May 1891), often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian mystic and author who co-founded the Theosophical Society in 187 ...

, editor in chief of ''The Theosophist

''The Theosophist'' is the monthly journal of the international Theosophical Society based in Adyar, India. It was founded in India in 1879 by Helena Blavatsky, who was also its editor. The journal is still being published till date. For the ye ...

,'' started publishing her translation into English of " The Grand Inquisitor" from Book V, chapter five of Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

's novel '' The Brothers Karamazov.''

In a small commentary which preceded the beginning of the publication, she explained that "the great Russian novelist" Dostoevsky died a few months ago, making the "celebrated" novel ''The Brothers Karamazov'' his last work. She described the passage as a "satire" on modern theology in general and on the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in particular. As described by Blavatsky, "The Grand Inquisitor" imagines the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

of Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, names and titles), was ...

occurring in Spain during the time of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

. Christ is at once arrested as a heretic by the Grand Inquisitor. The legend, or "poem", is created by the character Ivan Karamazov

''The Brothers Karamazov'' (russian: Братья Карамазовы, ''Brat'ya Karamazovy'', ), also translated as ''The Karamazov Brothers'', is the last novel by Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. Dostoevsky spent nearly two years writing '' ...

, a materialist and an atheist, who tells it to his younger brother Alyosha, an immature Christian mystic."

According to Brendan French, a researcher in esotericism, "it is highly significant" that xactly 8 years after her publication of "The Grand Inquisitor"Blavatsky declared Dostoevsky to be "a theosophical writer." In her article about the approach of a new era in both society and literature, called "The Tidal Wave", she wrote:

" he root of evil lies, therefore, in a moral, not in a physical cause.If asked what is it then that will help, we answer boldly:—Theosophical literature; hastening to add that under this term, neither books concerningadept An adept is an individual identified as having attained a specific level of knowledge, skill, or aptitude in doctrines relevant to a particular author or organization. He or she stands out from others with their great abilities. All human quali ...s andphenomena A phenomenon ( : phenomena) is an observable event. The term came into its modern philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be directly observed. Kant was heavily influenced by Gottfried W ..., nor theTheosophical Society The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875, is a worldwide body with the aim to advance the ideas of Theosophy in continuation of previous Theosophists, especially the Greek and Alexandrian Neo-Platonic philosophers dating back to 3rd century CE ...publications are meant... What the European world now needs is a dozen writers such as Dostoyevsky, the Russian author... It is writers of this kind that are needed in our day of reawakening; not authors writing for wealth or fame, but fearless apostles of the living Word of Truth, moral healers of the pustulous sores of our century... To write novels with a moral sense in them deep enough to stir Society, requires a literary talent and a ''born'' Theosophist as was Dostoyevsky."

Tolstoy

When

When Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

was working on his book ''The Thoughts of Wise People for Every Day,'' he used a magazine of the Theosophical Society of Germany ''Theosophischer Wegweiser''. He extracted eight aphorisms of the Indian sage Ramakrishna

Ramakrishna Paramahansa ( bn, রামকৃষ্ণ পরমহংস, Ramôkṛṣṇo Pôromohôṅso; , 18 February 1836 – 16 August 1886),——— — also spelled Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, born Gadadhar Chattopadhyaya,, was an In ...

, eight from ''The Voice of the Silence

''The Voice of the Silence'' is a book by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. It was written in Fontainebleau and first published in 1889. According to Blavatsky, it is a translation of fragments from a sacred book she encountered during her studies in ...

'' by Blavatsky, and one of fellow Theosophist Franz Hartmann

Franz Hartmann (22 November 1838, Donauwörth – 7 August 1912, Kempten im Allgäu) was a German medical doctor, theosophist, occultist, geomancer, astrologer, and author.

Biography

Hartmann was an associate of Helena Blavatsky and was Ch ...

, from the issues of 1902 and 1903, and translated them into Russian. Tolstoy had in his library the English edition of ''The Voice of the Silence'', which had been presented to him by its author.

In November 1889, Blavatsky published her own English translation of Tolstoy's fairy tale "How A Devil's Imp Redeemed His Loaf, or The First Distiller", which was accompanied by a small preface about the features of translation from Russian. Calling Tolstoy "the greatest novelist and mystic of Russia of to-day," she wrote that all his best works had already been translated, but that the attentive Russian reader would not find the "popular national spirit" that permeates all original stories and fairy tales, in any of these translations. Despite the fact that they are full of "popular mysticism", and some of them are "charming", they are the most difficult to translate into a foreign language. She concluded: "No foreign translator, however able, unless born and bred in Russia and acquainted with Russian ''peasant'' life, will be able to do them justice, or even to convey to the reader their full meaning, owing to their absolutely national idiomatic language

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tongu ...

."

In September 1890, Blavatsky published philosopher Raphael von Koeber

Raphael von Koeber (russian: Рафаэль Густавович фон Кёбер, translit=Rafaèl' Gustavovič fon Këber; - 14 June 1923) was a notable Russian-German teacher of philosophy and musician at the Tokyo Imperial University in Jap ...

's article "Leo Tolstoi and his Unecclesiastical Christianity" in her magazine '' Lucifer''. Prof. von Koeber briefly described the merits of Tolstoy as a great master of artistic language, but the main focus of the article was Tolstoy's search for answers to religious and philosophical questions. The author concluded that Tolstoу's "philosophy of life" is identical in its foundation to that of Theosophy.

Theosophist Charles Johnston, president of the New York branch of the Irish Literary Society The Irish Literary Society was founded in London in 1892 by William Butler Yeats, T. W. Rolleston ,and Charles Gavan Duffy. Members of the Southwark Irish Literary Club met in Clapham Reform Club and changed the name early in the year. On 13 Febru ...

, travelled to Russia and met with Tolstoy. In March 1899 Johnston published "How Count Tolstoy Writes?" in the American magazine ''The Arena

An arena is an enclosed area that showcases theatre, musical performances or sporting events.

Arena, ARENA, or the Arena may also refer to:

Places and jurisdictions

* Arena, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Arena, Iran

* Arena, Calabria, Italy

* La ...

''. In November 1904, Rudolf Steiner gave a lecture in Berlin entitled "Theosophy and Tolstoy", where he discussed the novels '' War and Peace'', '' Anna Karenina'', the novella ''The Death of Ivan Ilyich

''The Death of Ivan Ilyich'' (also Romanized ''Ilich, Ilych, Ilyitch''; russian: Смерть Ивана Ильича, Smert' Ivána Ilyicha), first published in 1886, is a novella by Leo Tolstoy, considered one of the masterpieces of his late ...

'', and the philosophical book ''On Life'' (1886–87).

Yeats

Yeats became interested in Theosophy in 1884, after reading '' Esoteric Buddhism'' by Alfred Percy Sinnett. A copy of the book was sent him by his aunt, Isabella Varley. Together with his friends George Russell and Charles Johnston, he established the

Yeats became interested in Theosophy in 1884, after reading '' Esoteric Buddhism'' by Alfred Percy Sinnett. A copy of the book was sent him by his aunt, Isabella Varley. Together with his friends George Russell and Charles Johnston, he established the Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

Hermetic Society, which would later become the Irish section of the Theosophical Society. According to ''Encyclopedia of Occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

ism and Parapsychology'' (EOP), Yeats's tendency toward mysticism was "stimulated" by the religious philosophy of the Theosophical Society.

In 1887, Yeats's family moved to London, where he was introduced to Blavatsky by his friend Johnston. In her external appearance she reminded him of "an old Irish peasant woman". He recalled her massive figure, constant cigarette smoking, and unceasing work at her writing desk which, he claimed, "she did for twelve hours a day." He respected her "sense of humor, her dislike of formalism, her abstract idealism, and her intense, passionate nature." At the end of 1887, she officially founded the Blavatsky Lodge of the Theosophical Society in London. Yeats entered into the Esoteric Section of the Lodge in December 1888 and became a member of the "Recording Committee for Occult Research" in December 1889. In August 1890, to his great regret, he was expelled from the Society for undertaking occult experiments forbidden by the Theosophists.

According to ''The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

''The Encyclopedia of Fantasy'' is a 1997 reference work concerning fantasy fiction, edited by John Clute and John Grant. Other contributors include Mike Ashley, Neil Gaiman, Diana Wynne Jones, David Langford, Sam J. Lundwall, Michael Scott R ...

'' (EF), Yeats wrote extensively on mysticism and magic. In 1889 he published an article—"Irish Fairies, Ghosts, Witches, etc."—in Blavatsky's journal, and another in 1914—"Witches and Wizards and Irish Folk-Lore". Literary scholar Richard Ellmann

Richard David Ellmann, FBA (March 15, 1918 – May 13, 1987) was an American literary critic and biographer of the Irish writers James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, and William Butler Yeats. He won the U.S. National Book Award for Nonfiction for ''James ...

wrote of him:

"Yeats found in occultism, and in mysticism generally, a point of view which had the virtue of warring with accepted belief... He wanted to secure proof that experimental science was limited in its results, in an age when science made extravagant claims; he wanted evidence that anideal world Ideal World is a British TV shopping channel, broadcasting on Freeview, Satellite, Cable and online, with transactional websites, broadcast from studios in Peterborough. History Ideal World has its origins in the 1980s as a mail order compan ...existed, in an age which was fairly complacent about the benefits of actuality; he wanted to show that the current faith in reason and in logic ignored a far more important human faculty, the imagination."

Poetry and mysticism

According to Gertrude Marvin Williams, British poet Alfred Tennyson was reading Blavatsky's "mysticalpoem

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in ...

" ''The Voice of the Silence'' in the last days of his life.

In his article on Blavatsky, Prof. Russell Goldfarb mentions a lecture by American psychologist and philosopher William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

in which he said that "mystical truth spoke best as musical composition rather than as conceptual speech." As evidence for this, James cited this passage from ''The Voice of the Silence'' in his book '' The Varieties of Religious Experience'':

In"He, who would hear the voice of '' Nada Nada may refer to: Culture * Nāda, a concept in ancient Indian metaphysics Places *Nada, Hainan, China *Nada, Kentucky, an unincorporated community in the United States *Nada, Nepal, village in Achham District, Seti Zone * Nada, Texas, United S ...'', 'the Soundless Sound,' and comprehend it, he has to learn the nature of '' Dhāranā''... When to himself his form appears unreal, as do on waking all the forms he sees in dreams; when he has ceased to hear the many, he may discern the One—the inner sound which kills the outer... For then the soul will hear, and will remember. And then to the inner ear will speak The Voice Of The Silence... And now thy ''Self'' is lost in Self, ''thyself'' unto Thyself, merged in that Self from which thou first didst radiate... Behold! thou hast become the Light, thou has become the Sound, thou art thy Master and thy God. Thou art Thyself the object of thy search; the Voice unbroken, that resounds throughout eternities, exempt from change, from sin exempt, the seven sounds in one, the Voice Of The Silence. ''Om tat Sat.''"

Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

writer Dennis Lingwood's opinion, the author of ''The Voice of the Silence'' (abbreviated VS) "seeks more to inspire than to instruct, appeals to the heart rather than to the head." A researcher of NRM Arnold Kalnitsky wrote that, in spite of inevitable questions on the origins and authorship of VS, the "authenticity of the tone of the teachings and the expression of the sentiments" have risen above the Theosophical and occult environment, receiving "independent respect" from such authorities as William James, D. T. Suzuki and others.

Russian esotericist P. D. Ouspensky

Pyotr Demianovich Ouspenskii (known in English as Peter D. Ouspensky; rus, Пётр Демья́нович Успе́нский, Pyotr Demyánovich Uspénskiy; 5 March 1878 – 2 October 1947) was a Russian esotericist known for his expositions ...

affirmed that VS has a "very special" position in modern mystical literature, and used several quotes from it in his book ''Tertium Organum'' to demonstrate "the wisdom of the East." Writer Howard Murphet has called VS a "little gem", noting that its poetry "is rich in both imagery and mantra

A mantra (Pali: ''manta'') or mantram (मन्त्रम्) is a sacred utterance, a numinous sound, a syllable, word or phonemes, or group of words in Sanskrit, Pali and other languages believed by practitioners to have religious, ma ...

-like vibrations." Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

characterized the language of VS as "perfect and beautiful English, flowing and musical."

In Prof. Robert Ellwood

Robert S. Ellwood (born 1933) is an American academic, author and expert on world religions.

He was educated at the University of Colorado, Berkeley Divinity School and was awarded a PhD in History of Religions from the University of Chicago in 1 ...

's opinion, the book is a "short mystical devotional work of rare beauty." Other scholars of religious studies have suggested that: a rhythmic modulation in VS supports "the feeling of mystical devotion"; the questions illumined in VS are "explicitly devoted to the attainment of mystical states of consciousness"; and that VS is among the "most spiritually practical works produced by Blavatsky."

William James said of mysticism that: "There is a verge of the mind which these things haunt; and whispers therefrom mingle with the operations of our understanding, even as the waters of the infinite ocean send their waves to break among the pebbles that lie upon our shores."

Theosophical fiction

Forerunner

According to scholar Brendan French, novels by authors in the Rosicrucian tradition are a path to the "conceptual domain" of Blavatsky. He notes that ''

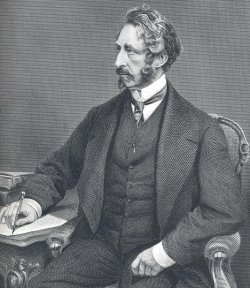

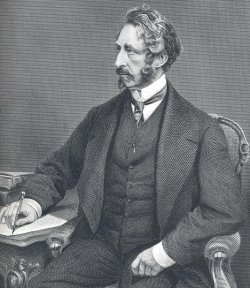

According to scholar Brendan French, novels by authors in the Rosicrucian tradition are a path to the "conceptual domain" of Blavatsky. He notes that ''Zanoni

''Zanoni'' is an 1842 novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, a story of love and occult aspiration. By way of introduction, the author confesses: "... It so chanced that some years ago, in my younger days, whether of authorship or life, I felt the d ...

'' (1842) by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton, PC (25 May 180318 January 1873) was an English writer and politician. He served as a Whig member of Parliament from 1831 to 1841 and a Conservative from 1851 to 1866. He was Secret ...

is "undoubtedly the apogee of the genre". It was this novel that later had the greatest impact on the elaboration of the concept of the Theosophical mahatmas. French quoted Blavatsky as saying: "No author in the world of literature ever gave a more truthful or more poetical description of these beings than Sir E. Bulwer-Lytton, the author of ''Zanoni''."

This novel is especially important for followers of occultism because of "the suspicion—actively fostered by its author—that the work is not a fictional account of a mythical fraternity, but ''an accurate depiction of a real brotherhood of immortals''." According to EF, Bulwer-Lytton's character the " Dweller on the Threshold" has since become widely used by followers of Theosophy and authors of "weird fiction".

A second important novel for Theosophists by Bulwer-Lytton is '' The Coming Race'' published in 1871.

Theosophists as fiction writers

According to French, Theosophy has contributed much to the expansion of occultism in fiction. Not only were Theosophists writing occult fiction, but many professional authors who were prone to mysticism joined the Theosophical Society. Russian literary scholar Anatoly Britikov wrote that "Theosophical myth is beautiful and poetic" because its authors had an "extraordinary talent for fiction", and borrowed their ideas from works of "high literary value." InJohn Clute

John Frederick Clute (born 12 September 1940) is a Canadian-born author and critic specializing in science fiction and fantasy literature who has lived in both England and the United States since 1969. He has been described as "an integral part o ...

's opinion, Blavatsky's own fiction, most of which was published in 1892 in the collection ''Nightmare Tales,'' is "unimportant". However, her main philosophical works, ''Isis Unveiled

''Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology'', published in 1877, is a book of esoteric philosophy and Helena Petrovna Blavatsky's first major work and a key text in her Theosophical movement.

The ...

'' and ''The Secret Doctrine

''The Secret Doctrine, the Synthesis of Science, Religion and Philosophy'', is a pseudo-scientific esoteric book originally published as two volumes in 1888 written by Helena Blavatsky. The first volume is named ''Cosmogenesis'', the second ''An ...

,'' can be considered as rich sources that contain "much raw material for creators of fantasy worlds". He wrote that in its content, supported by an attendant entourage that intensifies its effect, Theosophy is a "sacred drama, a romance, a secret history" of the world. Those whose souls are "sufficiently evolved to understand that drama know the tale is enacted in another place, beyond the threshold... within a land exempt from secular accident."

In Prof. Antoine Faivre's opinion, ''Ghost Land, or Researches into the Mysteries of Occultism'' by Emma Hardinge Britten

Emma Hardinge Britten (2 May 1823 – 2 October 1899) was an English advocate for the early Modern Spiritualist Movement. Much of her life and work was recorded and published in her speeches and writing and an incomplete autobiography edite ...

, one of the founders of the Theosophical movement, is "one of the principal works of fiction inspired by the occultist current".

Mabel Collins

Mabel Collins (9 September 1851 – 31 March 1927) was a British theosophist and author of over 46 books.

Life

Collins was born in St Peter Port, Guernsey. She was a writer of popular occult novels, a fashion writer and an anti-vivisection campa ...

, who helped Blavatsky edit the Theosophical journal ''Lucifer'' in London, wrote a book entitled ''The Blossom and the Fruit: A True Story of a Black Magician'' (1889). According to EOP the book demonstrated her growing interest in metaphysics and occultism. After leaving editorial work, however, she published several books that parodied Blavatsky and her Masters.

Franz Hartmann

Franz Hartmann (22 November 1838, Donauwörth – 7 August 1912, Kempten im Allgäu) was a German medical doctor, theosophist, occultist, geomancer, astrologer, and author.

Biography

Hartmann was an associate of Helena Blavatsky and was Ch ...

has published several fiction works: ''An Adventure among the Rosicrucians'' (1887), the Theosophical satire ''The Talking Image of Urur'' (1890), and ''Among the Gnomes'' (1895)—a satire on those who immediately deny everything "supernatural". Russian philologist Alexander Senkevich noted that Blavatsky perfectly understood that the titular 'Talking Image' was her "caricatured persona", but nevertheless continued publishing the novel in her magazine for many months. In the foreword to the first edition its author proclaimed that the characters of the novel are "so to say, composite photographs of living people", and that it was created "with the sole object of showing to what absurdities a merely intellectual research after spiritual truths will lead." "The end of Hartmann's novel is unexpected. The evil forces that held the 'Talking Image' weaken, and it is freed from the darkening of consciousness. The author's final conclusion is quite a Buddhist one: 'Search for the truth yourself: do not entrust this to someone else'."

The Theosophical leaders William Quan Judge, Charles Webster Leadbeater

Charles Webster Leadbeater (; 16 February 1854 – 1 March 1934) was a member of the Theosophical Society, Co-Freemasonry, author on occult subjects and co-initiator with J. I. Wedgwood of the Liberal Catholic Church.

Originally a pr ...

, Anna Kingsford, and others wrote so-called "weird stories". In his fiction collection, Leadbeater gave a brief description of Blavatsky as a storyteller of occult tales: "She held her audience spell-bound, she played on them as on an instrument and made their hair rise at pleasure, and I have often noticed how careful they were to go about in couples after one of her stories, and to avoid being alone even for a moment!" The novel ''Karma'' by Alfred Sinnett is, in essence, a presentation of the Theosophical doctrines of karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptivel ...

and reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

, using knowledge of past lives and the present karma of the leading characters. His next occult novel ''United,'' was published in 1886 in 2 volumes.

A trilogy '' The Initiate'' (1920–32) by Cyril Scott

Cyril Meir Scott (27 September 1879 – 31 December 1970) was an English composer, writer, poet, and occultist. He created around four hundred musical compositions including piano, violin, cello concertos, symphonies, and operas. He also wrot ...

was extremely popular and reprinted several times. In it the author expounds his understanding of the Theosophical doctrine, using fictional characters alongside real ones.

Fiction writers and Theosophy

In 1887, Blavatsky published the article "The Signs of the Times", in which she discussed the growing influence of Theosophy in literature. She listed some novels that can be categorized as Theosophical and mystical literature, including ''Mr Isaacs'' (1882) and ''Zoroaster'' (1885) by Francis Marion Crawford; ''The Romance of Two Worlds'' (1886) by

In 1887, Blavatsky published the article "The Signs of the Times", in which she discussed the growing influence of Theosophy in literature. She listed some novels that can be categorized as Theosophical and mystical literature, including ''Mr Isaacs'' (1882) and ''Zoroaster'' (1885) by Francis Marion Crawford; ''The Romance of Two Worlds'' (1886) by Marie Corelli

Mary Mackay (1 May 185521 April 1924), also called Minnie Mackey, and known by her pseudonym Marie Corelli (, also , ), was an English novelist.

From the appearance of her first novel ''A Romance of Two Worlds'' in 1886, she became the bestsel ...

; ''The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'' is a 1886 Gothic novella by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. It follows Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner who investigates a series of strange occurrences between his old ...

'' (1886) by Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

; ''A Fallen Idol'' (1886) by F. Anstey

Thomas Anstey Guthrie (8 August 1856 – 10 March 1934) was an English author (writing as F. Anstey), most noted for his comic novel ''Vice Versa'' about a boarding-school boy and his father exchanging identities. His reputation was confirmed b ...

; ''King Solomon's Mines

''King Solomon's Mines'' (1885) is a popular novel by the English Victorian adventure writer and fabulist Sir H. Rider Haggard. It tells of a search of an unexplored region of Africa by a group of adventurers led by Allan Quatermain for the ...

'' (1885) and '' She: A History of Adventure'' (1887) by H. Rider Haggard

Sir Henry Rider Haggard (; 22 June 1856 – 14 May 1925) was an English writer of adventure fiction romances set in exotic locations, predominantly Africa, and a pioneer of the lost world literary genre. He was also involved in land reform ...

; ''Affinities'' (1885) and ''The Brother of the Shadow'' (1886) by Rosa Campbell Praed; ''A House of Tears'' (1886) by Edmund Downey

Edmund Downey (''nom de plume'' F. M. Allen) (24 July 1856, in Waterford – 11 February 1937, in Waterford) was an Irish novelist, newspaper editor, and publisher.

After education at Catholic University High School, Waterford and St. John's Co ...

; and ''A Daughter of the Tropics'' (1887) by Florence Marryat

Florence Marryat (9 July 1833 – 27 October 1899) was a British author and actress. The daughter of author Capt. Frederick Marryat, she was particularly known for her sensational novels and her involvement with several celebrated spiritual me ...

.

According to EOP, the prototype for the main character of Crawford's novel ''Mr Isaacs'' was someone called Mr. Jacob, a Hindu mage of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Blavatsky was particularly charmed by Crawford's Ram Lal, a character akin to Bulwer-Lytton's Mejnour or Koot Hoomi of the Theosophists. Ram Lal says of himself: "I am not omnipotent. I have very little more power than you. Given certain conditions I can produce certain results, palpable, visible, and appreciable by all; but ''my power'', as you know, ''is itself merely the knowledge of the laws of nature'', which Western scientists, in their ignorance, ignore." According to EF, this book informs readers about some of the teachings of Theosophy.

Rosa Campbell Praed was interested in spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) ...

, occultism, and Theosophy, and made the acquaintance of many Theosophists who, as French pointed out, "inevitably became characters in her novels". He wrote: "Praed was especially influenced by her meeting in 1885 with Mohini Chatterji (who became the model for Ananda in ''The Brother of the Shadow'')."

French wrote that figures of the Theosophical mahatmas appear in several of the most popular novels of Marie Corelli, including her first book ''The Romance of Two Worlds'' (1886). A similar theme is present in ''A Fallen Idol'' (1886) by F. Anstey.

According to EOP, the author of occult novels Algernon Blackwood

Algernon Henry Blackwood, CBE (14 March 1869 – 10 December 1951) was an English broadcasting narrator, journalist, novelist and short story writer, and among the most prolific ghost story writers in the history of the genre. The literary cri ...

specialized in literature describing psychic phenomena and ghosts. In their article "Theosophy and Popular Fiction", the esotericism researchers Gilhus and Mikaelsson point out that in his novel ''The Human Chord'' (1910), Blackwood warns readers about the dangers of occult experiments.

Gustav Meyrink's novel '' The Golem'' (1914) is mentioned by many researchers of esotericism. Writer Talbot Mundy

Talbot Mundy (born William Lancaster Gribbon, 23 April 1879 – 5 August 1940) was an English writer of adventure fiction. Based for most of his life in the United States, he also wrote under the pseudonym of Walter Galt. Best known as the ...

created his works on the basis of the Theosophical assumption that various forms of occultism exist as evidence of the ancient wisdom that is preserved at the present time, thanks to the secret brotherhood of adepts.

Characters whose prototype was Blavatsky

* Mme Tamvaco in a novel by Rosa Campbell Praed ''Affinities''

* Image of Urur in a novel by

* Mme Tamvaco in a novel by Rosa Campbell Praed ''Affinities''

* Image of Urur in a novel by Franz Hartmann

Franz Hartmann (22 November 1838, Donauwörth – 7 August 1912, Kempten im Allgäu) was a German medical doctor, theosophist, occultist, geomancer, astrologer, and author.

Biography

Hartmann was an associate of Helena Blavatsky and was Ch ...

''The Talking Image of Urur''

* Maya in the story of the same name by Vera Zhelikhovsky

Vera Zhelikhovsky (russian: Ве́ра Петро́вна Желихо́вская, uk, Віра Желіховська Петрівна; April 29, 1835 – May 17, 1896), sometimes transliterated as Vera Jelihovsky, was a Russian writer, mostly ...

* Mme Petrovna in a novel by William Lincoln Garver

William Lincoln Garver was an American architect, civil engineer, author, socialist leader, and political candidate from Missouri. He was primarily an architect by trade, and learned while working under his uncle, architect Morris Frederick Bell ...

''Brother of the Third Degree''

* Mme Sosostris in a poem by T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biogr ...

''The Waste Land

''The Waste Land'' is a poem by T. S. Eliot, widely regarded as one of the most important poems of the 20th century and a central work of modernist poetry. Published in 1922, the 434-line poem first appeared in the United Kingdom in the Octob ...

''

* Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in a novel by Mark Frost '' The List of 7''

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * () * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * (1st part) * * * * * * * * * ;In Russian * (1980) * (1893) * (1886) * (1886–1887) * (1903)See also

* '' From the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan'' *Theosophy and visual arts

Modern Theosophy has had considerable influence on the work of visual artists, particularly painters. Artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Luigi Russolo chose Theosophy as the main ideological and philosophical basis of their wo ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;In Russian * * * * * * *External links

List of the journal publications by/about Yeats

{{Theosophy series Theosophy Helena Blavatsky Fantasy literature Science fiction literature Literary criticism Religious studies