The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' is a

In 1890, Baum lived in

In 1890, Baum lived in

''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900 illustrated copy)

Publisher's green and red illustrated cloth over boards; illustrated endpapers. Plate detached. Public Domain – Charles E. Young Research Library,

Online version of the 1900 first edition

on the

''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum''

an unabridged dramatic audio performance at Wired for Books. *

A Long and Dangerous Journey – A History of ''The Wizard of Oz'' on the Silver Screen

– Scream-It-Loud.com * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wonderful Wizard Of Oz, The 1900 American novels 1900 children's books 1900 fantasy novels American fantasy novels adapted into films American novels adapted into plays American novels adapted into television shows Books about lions Censored books Farms in fiction Novels about orphans Novels adapted into comics Novels adapted into radio programs Novels adapted into video games Novels set in fictional countries Novels set in Kansas Oz (franchise) books Portal fantasy Witchcraft in written fiction Wizards in fiction

children's novel

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's ...

written by author L. Frank Baum

Lyman Frank Baum (; May 15, 1856 – May 6, 1919) was an American author best known for his children's books, particularly ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' and its sequels. He wrote 14 novels in the ''Oz'' series, plus 41 other novels (not includ ...

and illustrated by W. W. Denslow

William Wallace Denslow (; May 5, 1856 – March 29, 1915), professionally W. W. Denslow, was an American illustrator and caricaturist remembered for his work in collaboration with author L. Frank Baum, especially his illustrations of ''The ...

. It is the first novel in the Oz series of books. A Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

farm girl named Dorothy

Dorothy may refer to:

*Dorothy (given name), a list of people with that name.

Arts and entertainment

Characters

*Dorothy Gale, protagonist of ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' by L. Frank Baum

* Ace (''Doctor Who'') or Dorothy, a character playe ...

ends up in the magical Land of Oz

The Land of Oz is a magical country introduced in the 1900 children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by W. W. Denslow.

Oz consists of four vast quadrants, the Gillikin Country in the north, Quadli ...

after she and her pet dog Toto are swept away from their home by a tornado

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, altho ...

. Upon her arrival in Oz, she learns she cannot return home until she has destroyed the Wicked Witch of the West

The Wicked Witch of the West is a fictional character who appears in the classic children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900), created by American author L. Frank Baum. In Baum's subsequent ''Oz'' novels, it is the Nome King who is ...

.

The book was first published in the United States in May 1900 by the George M. Hill Company. In January 1901, the publishing company completed printing the first edition, a total of 10,000 copies, which quickly sold out. It had sold three million copies by the time it entered the public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work

A creative work is a manifestation of creative effort including fine artwork (sculpture, paintings, drawing, sketching, performance art), dance, writing (literature), filmmaking, ...

in 1956. It was often reprinted under the title ''The Wizard of Oz'', which is the title of the successful 1902 Broadway musical adaptation as well as the classic 1939 live-action film.

The ground-breaking success of both the original 1900 novel and the 1902 Broadway musical prompted Baum to write thirteen additional Oz books

The Oz books form a book series that begins with ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900) and relates the fictional history of the Land of Oz. Oz was created by author L. Frank Baum, who went on to write fourteen full-length Oz books. All of Baum's b ...

which serve as official sequels to the first story. Over a century later, the book is one of the best-known stories in American literature, and the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

has declared the work to be "America's greatest and best-loved homegrown fairytale."

Publication

L. Frank Baum

Lyman Frank Baum (; May 15, 1856 – May 6, 1919) was an American author best known for his children's books, particularly ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' and its sequels. He wrote 14 novels in the ''Oz'' series, plus 41 other novels (not includ ...

's story was published by George M. Hill Company. The first edition had a printing of 10,000 copies and was sold in advance of the publication date of September 1, 1900. On May 17, 1900, the first copy came off the press; Baum assembled it by hand and presented it to his sister, Mary Louise Baum Brewster. The public saw it for the first time at a book fair at the Palmer House

The Palmer House – A Hilton Hotel is a historic hotel in Chicago's Loop area. It is a member of the Historic Hotels of America program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The Palmer House was the city's first hotel with elevators ...

in Chicago, July 5–20. Its copyright was registered on August 1; full distribution followed in September. By October 1900, it had already sold out and the second edition of 15,000 copies was nearly depleted.

In a letter to his brother, Baum wrote that the book's publisher, George M. Hill, predicted a sale of about 250,000 copies. In spite of this favorable conjecture, Hill did not initially predict that the book would be phenomenally successful. He agreed to publish the book only when the manager of the Chicago Grand Opera House, Fred R. Hamlin, committed to making it into a musical stage play to publicize the novel.

The play '' The Wizard of Oz'' debuted on June 16, 1902. It was revised to suit adult preferences and was crafted as a "musical extravaganza," with the costumes modeled after Denslow's drawings. When Hill's publishing company became bankrupt in 1901, the Indianapolis-based Bobbs-Merrill Company

The Bobbs-Merrill Company was a book publisher located in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Company history

The company began in 1850 October 3 when Samuel Merrill bought an Indianapolis bookstore and entered the publishing business. After his death in ...

resumed publishing the novel. By 1938, more than one million copies of the book had been printed. By 1956, sales had grown to three million copies.

Plot

Dorothy Gale

Dorothy Gale is a fictional character created by American author L. Frank Baum as the protagonist in many of his ''Oz'' novels. She first appears in Baum's classic 1900 children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' and reappears in most of its ...

is a young girl who lives with her Aunt Em

Aunt Em is a fictional character from the Oz books. Jack Snow, ''Who's Who in Oz'', Chicago, Reilly & Lee, 1954; New York, Peter Bedrick Books, 1988; p. 10. She is the aunt of Dorothy Gale and wife of Uncle Henry, and lives together with them on ...

, Uncle Henry

Uncle Henry is a fictional character from The Oz Books by L. Frank Baum.Jack Snow (writer), Jack Snow, ''Who's Who in Oz'', Chicago, Reilly & Lee, 1954; New York, Peter Bedrick Books, 1988; p. 227. He is the uncle of Dorothy Gale and husband of A ...

, and dog, Toto, on a farm on the Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

prairie. One day, Dorothy and Toto are caught up in a cyclone

In meteorology, a cyclone () is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above (opposite to an anti ...

that deposits them and the farmhouse into Munchkin Country

Munchkin Country or Munchkinland, as it is referred to in the famous MGM musical film version, is the fictional eastern region of the Land of Oz in L. Frank Baum's Oz books, first described in ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900). Munchkin Count ...

in the magical Land of Oz

The Land of Oz is a magical country introduced in the 1900 children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by W. W. Denslow.

Oz consists of four vast quadrants, the Gillikin Country in the north, Quadli ...

. The falling house has killed the Wicked Witch of the East

The Wicked Witch of the East is a fictional character created by American author L. Frank Baum. She is a crucial

character but appears only briefly in Baum's classic children's series of ''Oz'' novels, most notably ''The Wonderful Wizard of ...

, the evil ruler of the Munchkin

A Munchkin is a native of the fictional Munchkin Country in the Oz books by American author L. Frank Baum. They first appear in the classic children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900) where they welcome Dorothy Gale to their city in ...

s. The Good Witch of the North arrives with three grateful Munchkins and gives Dorothy the magical silver shoes

The Silver Shoes are the magical shoes that appear in L. Frank Baum's 1900 novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' as heroine Dorothy Gale's transport home. They are originally owned by the Wicked Witch of the East but passed to Dorothy when her ho ...

that originally belonged to the Wicked Witch. The Good Witch tells Dorothy that the only way she can return home to Kansas is to follow the yellow brick road

The yellow brick road is a fictional element in the 1900 children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' by American author L. Frank Baum. The road also appears in the several sequel Oz books such as ''The Marvelous Land of Oz'' (1904) and ''Th ...

to the Emerald City

The Emerald City (sometimes called the City of Emeralds) is the capital city of the fictional Land of Oz in L. Frank Baum's Oz books, first described in ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900).

Fictional description

Located in the center of the La ...

and ask the great and powerful Wizard of Oz to help her. As Dorothy embarks on her journey, the Good Witch of the North kisses her on the forehead, giving her magical protection from harm.

On her way down the yellow brick road, Dorothy attends a banquet held by a Munchkin named Boq

Boq is a minor character in ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' by L. Frank Baum. Jack Snow, ''Who's Who in Oz'', Chicago, Reilly & Lee, 1954; New York, Peter Bedrick Books, 1988; p. 23. He becomes a more prominent character in Gregory Maguire's 1995 ...

. The next day, she frees a Scarecrow

A scarecrow is a decoy or mannequin, often in the shape of a human. Humanoid scarecrows are usually dressed in old clothes and placed in open fields to discourage birds from disturbing and feeding on recently cast seed and growing crops.Lesley ...

from the pole on which he is hanging, applies oil from a can to the rusted joints of a Tin Woodman

Nick Chopper, the Tin Woodman, also known as the Tin Man or—mistakenly—the "Tin Woodsman," is a character in the fictional Land of Oz created by American author L. Frank Baum. Baum's Tin Woodman first appeared in his classic 1900 book ''The ...

, and meets a Cowardly Lion

The Cowardly Lion is a character in the fictional Land of Oz created by American author L. Frank Baum. He is depicted as an African lion, but like all animals in Oz, he can speak.

Since lions are supposed to be "The Kings of Beasts," the Cowardl ...

. The Scarecrow wants a brain, the Tin Woodman wants a heart, and the Lion wants courage, so Dorothy encourages them to journey with her and Toto to the Emerald City to ask for help from the Wizard.

After several adventures, the travelers arrive at the Emerald City and meet the Guardian of the Gates

This is a list of characters in the original Oz books by American author L. Frank Baum. The majority of characters listed here unless noted otherwise have appeared in multiple books under various plotlines. ''Land of Oz, Oz'' is made up of four ...

, who asks them to wear green tinted spectacles to keep their eyes from being blinded by the city's brilliance. Each one is called to see the Wizard. He appears to Dorothy as a giant head, to the Scarecrow as a lovely lady, to the Tin Woodman as a terrible beast, and to the Lion as a ball of fire, with the intention of scaring them all, but of course choosing the wrong image to make the desired impression. He agrees to help them all if they kill the Wicked Witch of the West

The Wicked Witch of the West is a fictional character who appears in the classic children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900), created by American author L. Frank Baum. In Baum's subsequent ''Oz'' novels, it is the Nome King who is ...

, who rules over Winkie Country

The Winkie Country is the western region of the fictional Land of Oz in L. Frank Baum's classic series of Oz books, first introduced in ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900). The Winkie Country is in the West, noted by later being ruled by the Wic ...

. The Guardian warns them that no one has ever managed to defeat the witch.

The Wicked Witch of the West sees the travelers approaching with her one telescopic eye. She sends a pack of wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; plural, : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large Canis, canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of Canis lupus, subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been reco ...

to tear them to pieces, but the Tin Woodman kills them with his axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

. She sends a flock of wild crow

A crow is a bird of the genus '' Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifica ...

s to peck their eyes out, but the Scarecrow kills them by twisting their necks. She summons a swarm of black bees to sting them, but they are killed while trying to sting the Tin Woodman while the Scarecrow's straw hides the others. She sends a dozen of her Winkie slaves to attack them, but the Lion stands firm to repel them. Finally, she uses the power of her Golden Cap to send the Winged Monkeys

Winged monkeys are fictional characters created by American author L. Frank Baum in his children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900). They are jungle monkeys with bird-like feathered wings. They are most notably remembered from the fam ...

to capture Dorothy, Toto, and the Lion. She cages the Lion, scatters the straw of the Scarecrow, and dents the Tin Woodman. Dorothy is forced to become the witch's personal slave, while the witch schemes to steal her silver shoes.

The witch successfully tricks Dorothy out of one of her silver shoes. Angered, she throws a bucket of water at the witch and is shocked to see her melt away. The Winkies rejoice at being freed from her tyranny and help restuff the Scarecrow and mend the Tin Woodman. They ask the Tin Woodman to become their ruler, which he agrees to do after helping Dorothy return to Kansas. Dorothy finds the witch's Golden Cap and summons the Winged Monkeys to carry her and her friends back to the Emerald City. The King of the Winged Monkeys tells how he and his band are bound by an enchantment to the cap by the sorceress Gayelette from the North, and that Dorothy may use it to summon them two more times.

When Dorothy and her friends meet the Wizard again, Toto tips over a screen in a corner of the throne room that reveals the Wizard, who sadly explains he is a humbug—an ordinary old man who, by a hot air balloon, came to Oz long ago from Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest city ...

. He provides the Scarecrow with a head full of bran, pins, and needles ("a lot of bran-new brains"), the Tin Woodman with a silk heart stuffed with sawdust, and the Lion a potion of "courage". Their faith in his power gives these items a focus for their desires. He decides to take Dorothy and Toto home and then go back to Omaha in his balloon. At the send-off, he appoints the Scarecrow to rule in his stead, which he agrees to do after helping Dorothy return to Kansas. Toto chases a kitten in the crowd and Dorothy goes after him, but the ropes holding the balloon break and the Wizard floats away.

Dorothy summons the Winged Monkeys and tells them to carry her and Toto home, but they explain they can't cross the desert surrounding Oz. The Soldier with the Green Whiskers

The Soldier with the Green Whiskers is a character from the fictional Land of Oz who appears in the classic children's series of List of Oz books, Oz books by American author L. Frank Baum and his successors. He is first introduced in ''The Wond ...

informs Dorothy that Glinda, the Good Witch of the South may be able to help her return home, so the travelers begin their journey to see Glinda's castle in Quadling Country

The Quadling Country is the southern division of L. Frank Baum's fictional Land of Oz, first introduced in ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900). It is distinguished by the color red, worn by most of the local inhabitants called the Quadlings as we ...

. On the way, the Lion kills a giant spider who is terrorizing the animals in a forest. They ask him to become their king, which he agrees to do after helping Dorothy return to Kansas. Dorothy summons the Winged Monkeys a third time to fly them over a hill to Glinda's castle.

Glinda greets them and reveals that Dorothy's silver shoes can take her anywhere she wishes to go. She embraces her friends, all of whom will be returned to their new kingdoms through Glinda's three uses of the Golden Cap: the Scarecrow to the Emerald City, the Tin Woodman to Winkie Country, and the Lion to the forest; after which the cap will be given to the King of the Winged Monkeys, freeing him and his band. Dorothy takes Toto in her arms, knocks her heels together three times, and wishes to return home. Instantly, she begins whirling through the air and rolling on the grass of the Kansas prairie, up to the farmhouse, though the silver shoes fall off her feet en route and are lost in the Deadly Desert

The Deadly Desert is the magical desert in Nonestica that completely surrounds the fictional Land of Oz, which cuts it off from the rest of the world.

Geology

On the map of Oz, first published in the endpapers of the eighth book, '' Tik-Tok of O ...

. She runs to Aunt Em, saying "I'm so glad to be home again!"

Illustrations

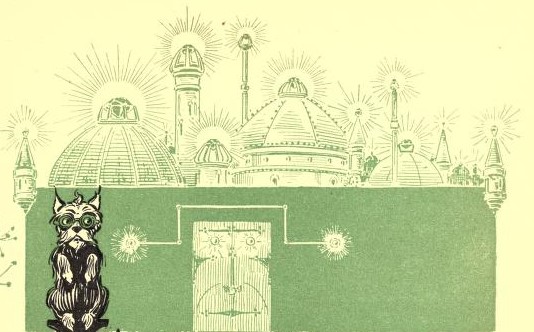

The book was illustrated by Baum's friend and collaboratorW. W. Denslow

William Wallace Denslow (; May 5, 1856 – March 29, 1915), professionally W. W. Denslow, was an American illustrator and caricaturist remembered for his work in collaboration with author L. Frank Baum, especially his illustrations of ''The ...

, who also co-held the copyright. The design was lavish for the time, with illustrations on many pages, backgrounds in different colors, and several color plate illustrations. The typeface featured the newly designed Monotype Old Style. In September 1900, The ''Grand Rapids Herald'' wrote that Denslow's illustrations are "quite as much of the story as in the writing". The editorial opined that had it not been for Denslow's pictures, the readers would be unable to picture precisely the figures of Dorothy, Toto, and the other characters.

Denslow's illustrations were so well known that merchants of many products obtained permission to use them to promote their wares. The forms of the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, the Cowardly Lion, the Wizard, and Dorothy were made into rubber and metal sculptures. Costume jewelry, mechanical toys, and soap were also designed using their figures. The distinctive look of Denslow's illustrations led to imitators at the time, most notably Eva Katherine Gibson's ''Zauberlinda, the Wise Witch'', which mimicked both the typography and the illustration design of ''Oz''.

A new edition of the book appeared in 1944, with illustrations by Evelyn Copelman. Although it was claimed that the new illustrations were based on Denslow's originals, they more closely resemble the characters as seen in the famous 1939 film version of Baum's book.

Creative inspiration

Baum's personal life

According to Baum's son, Harry Neal, the author had often told his children "whimsical stories before they became material for his books." Harry called his father the "swellest man I knew," a man who was able to give a decent reason as to why black birds cooked in a pie could afterwards get out and sing. Many of the characters, props, and ideas in the novel were drawn from Baum's personal life and experiences. Baum held different jobs, moved a lot, and was exposed to many people, so the inspiration for the story could have been taken from many different aspects of his life. In the introduction to the story, Baum writes that "it aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heart-aches and nightmares are left out."Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman

As a child, Baum frequently had nightmares of a scarecrow pursuing him across a field. Moments before the scarecrow's "ragged hay fingers" nearly gripped his neck, it would fall apart before his eyes. Decades later, as an adult, Baum integrated his tormentor into the novel as the Scarecrow. In the early 1880s, Baum's play ''Matches'' was being performed when a "flicker from a kerosene lantern sparked the rafters", causing the Baum opera house to be consumed by flames. Scholar Evan I. Schwartz suggested that this might have inspired the Scarecrow's severest terror: "There is only one thing in the world I am afraid of. A lighted match." According to Baum's son Harry, the Tin Woodman was born from Baum's attraction to window displays. He wished to make something captivating for the window displays, so he used an eclectic assortment of scraps to craft a striking figure. From a wash-boiler he made a body, from bolted stovepipes he made arms and legs, and from the bottom of a saucepan he made a face. Baum then placed a funnel hat on the figure, which ultimately became the Tin Woodman.Dorothy, Uncle Henry, and the Witches

Baum's wife Maud Gage frequently visited their newborn niece, Dorothy Louise Gage, whom she adored as the daughter she never had. The infant became gravely sick and died aged five months inBloomington, Illinois

Bloomington is a city and the county seat of McLean County, Illinois, United States. It is adjacent to the town of Normal, and is the more populous of the two principal municipalities of the Bloomington–Normal metropolitan area. Bloomington ...

on November 11, 1898, from "congestion of the brain". Maud was devastated. To assuage her distress, Frank made his protagonist of ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' a girl named Dorothy, and he dedicated the book to his wife. The baby was buried at Evergreen Cemetery, where her gravestone has a statue of the character Dorothy placed next to it.

Decades later, Jocelyn Burdick

Jocelyn Louise Burdick (''née'' Birch; February 6, 1922 – December 26, 2019) was an American politician from North Dakota who briefly served as a Democratic United States senator during 1992. She was the first woman from the state to hold thi ...

—the daughter of Baum's other niece Magdalena Carpenter and a former Democratic U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the Native Americans in the United States, indigenous Dakota people, Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north a ...

—asserted that her mother also partly inspired the character of Dorothy. Burdick claimed that her great-uncle spent "considerable time at the Сarpenter homestead... and became very attached to Magdalena." Burdick has reported many similarities between her mother's homestead and the farm of Aunt Em and Uncle Henry.

Uncle Henry

Uncle Henry is a fictional character from The Oz Books by L. Frank Baum.Jack Snow (writer), Jack Snow, ''Who's Who in Oz'', Chicago, Reilly & Lee, 1954; New York, Peter Bedrick Books, 1988; p. 227. He is the uncle of Dorothy Gale and husband of A ...

was modeled after Henry Gage, Baum's father-in-law. Bossed around by his wife Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

, Henry rarely dissented with her. He flourished in business, though, and his neighbors looked up to him. Likewise, Uncle Henry was a "passive but hard-working man" who "looked stern and solemn, and rarely spoke". The witches in the novel were influenced by witch-hunting research gathered by Matilda Gage. The stories of barbarous acts against accused witches scared Baum. Two key events in the novel involve wicked witches who meet their death through metaphorical means.

The Emerald City and the Land of Oz

In 1890, Baum lived in

In 1890, Baum lived in Aberdeen, South Dakota

Aberdeen ( Lakota: ''Ablíla'') is a city in and the county seat of Brown County, South Dakota, United States, located approximately northeast of Pierre. The city population was 28,495 at the 2020 census, making it the third most populous ci ...

during a drought, and he wrote a witty story in his "Our Landlady" column in Aberdeen's ''The Saturday Pioneer'' about a farmer who gave green goggles to his horses, causing them to believe that the wood chips that they were eating were pieces of grass. Similarly, the Wizard made the people in the Emerald City wear green goggles so that they would believe that their city was built from emeralds.

During Baum's short stay in Aberdeen, the dissemination of myths about the plentiful West continued. However, the West, instead of being a wonderland, turned into a wasteland because of a drought and a depression. In 1891, Baum moved his family from South Dakota to Chicago. At that time, Chicago was getting ready for the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

in 1893. Scholar Laura Barrett stated that Chicago was "considerably more akin to Oz than to Kansas". After discovering that the myths about the West's incalculable riches were baseless, Baum created "an extension of the American frontier in Oz". In many respects, Baum's creation is similar to the actual frontier save for the fact that the West was still undeveloped at the time. The Munchkins Dorothy encounters at the beginning of the novel represent farmers, as do the Winkies she later meets.

Local legend has it that Oz, also known as the Emerald City, was inspired by a prominent castle-like building in the community of Castle Park near Holland, Michigan

Holland is a city in the western region of the Lower Peninsula of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated near the eastern shore of Lake Michigan on Lake Macatawa, which is fed by the Macatawa River (formerly known locally as the Black Ri ...

, where Baum lived during the summer. The yellow brick road was derived from a road at that time paved by yellow bricks, located in Peekskill, New York

Peekskill is a city in northwestern Westchester County, New York, United States, from New York City. Established as a village in 1816, it was incorporated as a city in 1940. It lies on a bay along the east side of the Hudson River, across fro ...

, where Baum attended the Peekskill Military Academy

Peekskill Military Academy was a military academy for young men and women, founded in 1833 as Peekskill Academy, located in Peekskill, New York, United States.

Background

The academy was built by a hanging tree where a British spy was executed in ...

. Baum scholars often refer to the 1893 Chicago World's Fair (the "White City") as an inspiration for the Emerald City. Other legends suggest that the inspiration came from the Hotel Del Coronado

Hotel del Coronado, also known as The Del and Hotel Del, is a historic beachfront hotel in the city of Coronado, just across the San Diego Bay from San Diego, California. A rare surviving example of an American architectural genre—the wooden ...

near San Diego, California. Baum was a frequent guest at the hotel and had written several of the Oz books there. In a 1903 interview with ''The Publishers' Weekly

''Publishers Weekly'' (''PW'') is an American weekly trade news magazine targeted at publishing, publishers, librarians, bookselling, booksellers, and literary agents. Published continuously since 1872, it has carried the tagline, "The Internat ...

'', Baum said that the name "Oz" came from his file cabinet labeled "O–Z".

Some critics have suggested that Baum's Oz may have been inspired by Australia. Australia is often colloquially spelled or referred to as "Oz". Furthermore, in ''Ozma of Oz'' (1907), Dorothy gets back to Oz as the result of a storm at sea while she and Uncle Henry are traveling by ship to Australia. Like Australia, Oz is an island continent somewhere to the west of California with inhabited regions bordering on a great desert. Baum perhaps intended Oz to be Australia or a magical land in the center of the great Australian desert.

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''

In addition to being influenced by the fairy-tales of theBrothers Grimm

The Brothers Grimm ( or ), Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), were a brother duo of German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers, and authors who together collected and published folklore. They are among the ...

and Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen ( , ; 2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his literary fairy tales.

Andersen's fairy tales, consisti ...

, Baum was significantly influenced by English writer Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequel ...

's 1865 novel ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland), Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a ...

''. Although Baum found the plot of Carroll's novel to be incoherent, he identified the book's source of popularity as Alice herself—a child with whom younger readers could identify, and this influenced Baum's choice of Dorothy as his protagonist.

Baum also was influenced by Carroll's views that all children's books should be lavishly illustrated, be pleasurable to read, and not contain any moral lessons. During the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, Carroll had rejected the popular expectation that children's books must be saturated with moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. A ...

lessons and instead he contended that children should be allowed to be children.

Although influenced by Carroll's distinctly English work, Baum nonetheless sought to create a story that had recognizable American elements, such as farming and industrialization. Consequently, Baum combined the conventional features of a fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic (paranormal), magic, incantation, enchantments, and mythical ...

such as witch

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of Magic (supernatural), magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In Middle Ages, medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually ...

es and wizards with well-known fixtures in his young readers' Midwestern lives such as scarecrow

A scarecrow is a decoy or mannequin, often in the shape of a human. Humanoid scarecrows are usually dressed in old clothes and placed in open fields to discourage birds from disturbing and feeding on recently cast seed and growing crops.Lesley ...

s and cornfield

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

s.

Influence of Denslow

The original illustrator of the novel,W. W. Denslow

William Wallace Denslow (; May 5, 1856 – March 29, 1915), professionally W. W. Denslow, was an American illustrator and caricaturist remembered for his work in collaboration with author L. Frank Baum, especially his illustrations of ''The ...

, aided in the development of Baum's story and greatly influenced the way it has been interpreted. Baum and Denslow had a close working relationship and worked together to create the presentation of the story through the images and the text. Color is an important element of the story and is present throughout the images, with each chapter having a different color representation. Denslow also added characteristics to his drawings that Baum never described. For example, Denslow drew a house and the gates of the Emerald City with faces on them.

In the later ''Oz'' books, John R. Neill

John Rea Neill (November 12, 1877 – September 19, 1943) was a magazine and children's book illustrator primarily known for illustrating more than forty stories set in the Land of Oz, including L. Frank Baum's, Ruth Plumly Thompson's, and three o ...

, who illustrated all the sequels, continued to use elements from Denslow's earlier illustrations, including faces on the Emerald City's gates. Another aspect is the Tin Woodman's funnel hat, which is not mentioned in the text until later books but appears in most artists' interpretation of the character, including the stage and film productions of 1902–09, 1908, 1910, 1914, 1925, 1931, 1933, 1939, 1982, 1985, 1988, 1992, and others. One of the earliest illustrators not to include a funnel hat was Russell H. Schulz in the 1957 Whitman Publishing

Whitman Publishing is an American book publishing company which started as a subsidiary of the Western Printing & Lithographing Company of Racine, Wisconsin. In about 1915, Western began printing and binding a line of juvenile books for the Hammi ...

edition—Schulz depicted him wearing a pot on his head. Libico Maraja's illustrations, which first appeared in a 1957 Italian edition and have also appeared in English-language and other editions, are well known for depicting him bareheaded.

Allusions to 19th-century America

Many decades after its publication, Baum's work gave rise to a number of political interpretations, particularly in regards to the 19th-century Populist movement in the United States. In a 1964 '' American Quarterly'' article titled "The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism", educator Henry Littlefield posited that the book served an allegory for the late 19th-centurybimetallism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

debate regarding monetary policy. Littlefield's thesis achieved some support but was widely criticized by others. Other political interpretations soon followed. In 1971, historian Richard J. Jensen

Richard Joseph Jensen (born October 24, 1941) is an American historian, who was professor of history at the University of Illinois, Chicago, from 1973 to 1996. He has worked on American political, social, military, and economic history as well as ...

theorized in ''The Winning of the Midwest'' that "Oz" was derived from the common abbreviation for "ounce", used for denoting quantities of gold and silver.

Critical response

''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' received positive critical reviews upon release. In a September 1900 review, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' praised the novel, writing that it would appeal to child readers and to younger children who could not read yet. The review also praised the illustrations for being a pleasant complement to the text.

During the subsequent decades after the novel's publication in 1900, it received little critical analysis from scholars of children's literature. Lists of suggested reading published for juvenile readers never contained Baum's work, and his works were rarely assigned in classrooms. This lack of interest stemmed from the scholars' misgivings about fantasy, as well as to their belief that lengthy series had little literary merit.

It frequently came under fire in later decades. In 1957, the director of Detroit's libraries banned ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' for having "no value" for children of today, for supporting "negativism", and for bringing children's minds to a "cowardly level". Professor Russel B. Nye of Michigan State University

Michigan State University (Michigan State, MSU) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in East Lansing, Michigan. It was founded in 1855 as the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan, the fi ...

countered that "if the message of the Oz books—love, kindness, and unselfishness make the world a better place—seems of no value today", then maybe the time is ripe for "reassess nga good many other things besides the Detroit library's approved list of children's books".

In 1986, seven Fundamentalist Christian

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British and ...

families in Tennessee opposed the novel's inclusion in the public school syllabus and filed a lawsuit. They based their opposition to the novel on its depicting benevolent witches and promoting the belief that integral human attributes were "individually developed rather than God-given". One parent said, "I do not want my children seduced into godless supernaturalism". Other reasons included the novel's teaching that females are equal to males and that animals are personified and can speak. The judge ruled that when the novel was being discussed in class, the parents were allowed to have their children leave the classroom.

In April 2000, the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

declared ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' to be "America's greatest and best-loved homegrown fairytale", also naming it the first American fantasy for children and one of the most-read children's books. Leonard Everett Fisher of ''The Horn Book Magazine

''The Horn Book Magazine'', founded in Boston in 1924, is the oldest bimonthly magazine dedicated to reviewing children's literature. It began as a "suggestive purchase list" prepared by Bertha Mahony Miller and Elinor Whitney Field, proprietres ...

'' wrote in 2000 that ''Oz'' has "a timeless message from a less complex era, and it continues to resonate". The challenge of valuing oneself during impending adversity has not, Fisher noted, lessened during the prior 100 years. Two years later, in a 2002 review, Bill Delaney of ''Salem Press'' praised Baum for giving children the opportunity to discover magic in the mundane things in their everyday lives. He further commended Baum for teaching "millions of children to love reading during their crucial formative years". In 2012 it was ranked number 41 on a list of the top 100 children's novels published by ''School Library Journal

''School Library Journal'' (''SLJ'') is an American monthly magazine containing reviews and other articles for school librarians, media specialists, and public librarians who work with young people. Articles cover a wide variety of topics, with ...

''.

Editions

After George M. Hill's bankruptcy in 1902, copyright in the book passed to the Bowen-Merrill Company ofIndianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

. The company published most of Baum's other books from 1901 to 1903 ('' Father Goose, His Book'' (reprint), ''The Magical Monarch of Mo

''The Surprising Adventures of the Magical Monarch of Mo and His People'' (copyright registered June 17, 1896) is the first full-length children's fantasy novel by L. Frank Baum. Originally published in 1899 as ''A New Wonderland, Being the Firs ...

'' (reprint), ''American Fairy Tales

''American Fairy Tales'' is the title of a collection of twelve fantasy stories by L. Frank Baum, published in 1901 by the George M. Hill Company, the firm that issued ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' the previous year. The cover, title page, and ...

'' (reprint), ''Dot and Tot of Merryland

''Dot and Tot of Merryland'' is a 1901 novel by L. Frank Baum. After Baum wrote ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'', he wrote this story about the adventures of a little girl named Dot and a little boy named Tot in a land reached by floating on a riv ...

'' (reprint), '' The Master Key'', ''The Army Alphabet'', ''The Navy Alphabet'', ''The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus

''The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus'' is a 1902 children's book, written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by Mary Cowles Clark.

Setting

Plot

As a baby, Santa Claus is found in the Forest of Burzee by Ak, the Master Woodsman of the World ...

'', ''The Enchanted Island of Yew

''The Enchanted Island of Yew: Whereon Prince Marvel Encountered the High Ki of Twi and Other Surprising People'' is a children's fantasy novel written by L. Frank Baum, illustrated by Fanny Y. Cory, and published by the Bobbs-Merrill Company i ...

'', ''The Songs of Father Goose'') initially under the title ''The New Wizard of Oz''. The word "New" was quickly dropped in subsequent printings, leaving the now-familiar shortened title, "The Wizard of Oz," and some minor textual changes were added, such as to "yellow daises," and changing a chapter title from "The Rescue" to "How the Four Were Reunited." The editions they published lacked most of the in-text color and color plates of the original. Many cost-cutting measures were implemented, including removal of some of the color printing without replacing it with black, printing nothing rather than the beard of the Soldier with the Green Whiskers

The Soldier with the Green Whiskers is a character from the fictional Land of Oz who appears in the classic children's series of List of Oz books, Oz books by American author L. Frank Baum and his successors. He is first introduced in ''The Wond ...

.

When Baum filed for bankruptcy after his critically and popularly successful film and stage production ''The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays

''The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays'' was an early attempt to bring L. Frank Baum's Oz books to the motion picture screen. It was a mixture of live actors, hand-tinted magic lantern slides, and film. Baum himself would appear as if he were giving a ...

'' failed to make back its production costs, Baum lost the rights to all of the books published by what was now called Bobbs-Merrill, and they were licensed to the M. A. Donahue Company, which printed them in significantly cheaper "blotting paper" editions with advertising that directly competed with Baum's more recent books, published by the Reilly & Britton

The Reilly and Britton Company, known after 1918 as Reilly & Lee, was an American publishing company of the early and middle 20th century, best known for children's and popular culture books from authors like L. Frank Baum and Edgar A. Guest. Foun ...

Company, from which he was making his living, explicitly hurting sales of ''The Patchwork Girl of Oz

''The Patchwork Girl of Oz'' by L. Frank Baum is a children's novel, the seventh in the Oz series. Characters include the Woozy, Ojo "the Unlucky", Unc Nunkie, Dr. Pipt, Scraps (the patchwork girl), and others. The book was first published on ...

'', the new Oz book for 1913, to boost sales of ''Wizard'', which Donahue called in a full-page ad in ''The Publishers' Weekly

''Publishers Weekly'' (''PW'') is an American weekly trade news magazine targeted at publishing, publishers, librarians, bookselling, booksellers, and literary agents. Published continuously since 1872, it has carried the tagline, "The Internat ...

'' (June 28, 1913), Baum's "one pre-eminently great Juvenile Book." In a letter to Baum dated December 31, 1914, F.K. Reilly lamented that the average buyer

Procurement is the method of discovering and agreeing to terms and purchasing goods, services, or other works from an external source, often with the use of a tendering or competitive bidding process. When a government agency buys goods or serv ...

employed by a retail store would not understand why he should be expected to spend 75 cents for a copy of ''Tik-Tok of Oz

''Tik-Tok of Oz'' is the eighth Land of Oz book written by L. Frank Baum, published on June 19, 1914. The book has little to do with Tik-Tok and is primarily the quest of the Shaggy Man (introduced in ''The Road to Oz'') to rescue his brother, ...

'' when he could buy a copy of ''Wizard'' for between 33 and 36 cents. Baum had previously written a letter complaining about the Donahue deal, which he did not know about until it was ''fait accompli'', and one of the investors who held ''The Wizard of Oz'' rights had inquired why the royalty was only five or six cents per copy, depending on quantity sold, which made no sense to Baum.

A new edition from Bobbs-Merrill in 1949 illustrated by Evelyn Copelman, again titled ''The New Wizard of Oz'', paid lip service to Denslow but was based strongly, apart from the Lion, on the MGM movie. Copelman had illustrated a new edition of ''The Magical Monarch of Mo'' two years earlier.

It was not until the book entered the public domain in 1956 that new editions, either with the original color plates, or new illustrations, proliferated. A revised version of Copelman's artwork was published in a Grosset & Dunlap

Grosset & Dunlap is a New York City-based publishing house founded in 1898.

The company was purchased by G. P. Putnam's Sons in 1982 and today is part of Penguin Random House through its subsidiary Penguin Group.

Today, through the Penguin Gro ...

edition, and Reilly & Lee (formerly Reilly & Britton) published an edition in line with the Oz sequels, which had previously treated ''The Marvelous Land of Oz

''The Marvelous Land of Oz: Being an Account of the Further Adventures of the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman'', commonly shortened to ''The Land of Oz'', published in July 1904, is the second of L. Frank Baum's books set in the Land of Oz, and th ...

'' as the first Oz book, not having the publication rights to ''Wizard'', with new illustrations by Dale Ulrey. Ulrey had previously illustrated Jack Snow's ''Jaglon and the Tiger-Faries'', an expansion of a Baum short story, " The Story of Jaglon," and a 1955 edition of ''The Tin Woodman of Oz

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

'', though both sold poorly. Later Reilly & Lee editions used Denslow's original illustrations.

Notable more recent editions are the 1986 Pennyroyal edition illustrated by Barry Moser, which was reprinted by the University of California Press

The University of California Press, otherwise known as UC Press, is a publishing house associated with the University of California that engages in academic publishing. It was founded in 1893 to publish scholarly and scientific works by faculty ...

, and the 2000 ''The Annotated Wizard of Oz'' edited by Michael Patrick Hearn

Michael Patrick Hearn is an American literary scholar as well as a man of letters specializing in children's literature and its illustration. His works include ''The Annotated Wizard of Oz'' (1973/2000), '' The Annotated Christmas Carol'' (1977/20 ...

(heavily revised from a 1972 edition that was printed in a wide format that allowed for it to be a facsimile of the original edition with notes and additional illustrations at the sides), which was published by W. W. Norton and included all the original color illustrations, as well as supplemental artwork by Denslow

William Wallace Denslow (; May 5, 1856 – March 29, 1915), professionally W. W. Denslow, was an American illustrator and caricaturist remembered for his work in collaboration with author L. Frank Baum, especially his illustrations of ''The ...

. Other centennial editions included University Press of Kansas

The University Press of Kansas is a publisher located in Lawrence, Kansas. Operated by The University of Kansas, it represents the six state universities in the US state of Kansas: Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas S ...

's ''Kansas Centennial Edition'', illustrated by Michael McCurdy

Michael McCurdy (February 17, 1942 – May 28, 2016) was an American illustrator, author, and publisher. He illustrated over 200 books in his career, including ten that he authored. Most were illustrated with his trademark black and white wood en ...

with black-and-white illustrations, and Robert Sabuda

Robert James Sabuda (born March 8, 1965) is a children's pop-up book artist and paper engineer. His recent books include retellings of the stories of ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' and '' Alice in Wonderland''.New York Times, 2006

Early life

Rob ...

's pop-up book

The term pop-up book is often applied to any book with three-dimensional pages, although it is properly the umbrella term for movable book, pop-ups, tunnel books, transformations, volvelles, flaps, pull-tabs, pop-outs, pull-downs, and more, each ...

.

Sequels

Baum wrote ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' without any thought of a sequel. After reading the novel, thousands of children wrote letters to him, requesting that he craft another story about Oz. In 1904, amid financial difficulties, Baum wrote and published the first sequel, ''The Marvelous Land of Oz

''The Marvelous Land of Oz: Being an Account of the Further Adventures of the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman'', commonly shortened to ''The Land of Oz'', published in July 1904, is the second of L. Frank Baum's books set in the Land of Oz, and th ...

'', declaring that he grudgingly wrote the sequel to address the popular demand. He dedicated the book to stage actors Fred Stone

Fred Andrew Stone (August 19, 1873 – March 6, 1959) was an American actor. Stone began his career as a performer in circuses and minstrel shows, went on to act in vaudeville, and became a star on Broadway and in feature films, which earned h ...

and David C. Montgomery who played the characters of the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman on stage. Baum wrote large roles for the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman that he deleted from the stage version, ''The Woggle-Bug

The Mr. Highly Magnified Woggle-Bug, Thoroughly Educated is a character in the Oz books by L. Frank Baum. He first appears in the book ''The Marvelous Land of Oz'' in 1904. He goes by the name H. M. Woggle-Bug, T.E. (''Highly Magnified and Thor ...

'', after Montgomery and Stone had balked at leaving a successful show to do a sequel.

Baum later wrote sequels in 1907, 1908, and 1909. In his 1910 ''The Emerald City of Oz

''The Emerald City of Oz'' is the sixth of L. Frank Baum's fourteen Land of Oz books. It was also adapted into a Canadian animated film in 1987. Originally published on July 20, 1910, it is the story of Dorothy Gale and her Uncle Henry and Aunt E ...

'', he wrote that he could not continue writing sequels because Ozland had lost contact with the rest of the world. The children refused to accept this story, so Baum, in 1913 and every year thereafter until his death in May 1919, wrote an ''Oz'' book, ultimately writing 13 sequels and half a dozen Oz short stories.

Baum explained the purpose of his novels in a note he penned to his sister, Mary Louise Brewster, in a copy of ''Mother Goose in Prose

''Mother Goose in Prose'' is a collection of twenty-two children's story, children's stories based on Mother Goose nursery rhymes. It was the first children's book written by L. Frank Baum, and the first book illustrated by Maxfield Parrish. It wa ...

'' (1897), his first book. He wrote, "To please a child is a sweet and a lovely thing that warms one's heart and brings its own reward." After Baum's death in 1919, Baum's publishers delegated the creation of more sequels to Ruth Plumly Thompson

Ruth Plumly Thompson (27 July 1891 – 6 April 1976) was an American writer of children's stories, best known for writing many novels placed in Oz, the fictional land of L. Frank Baum's classic children's novel '' The Wonderful Wizard of Oz' ...

who wrote 21. An original ''Oz'' book was published every Christmas between 1913 and 1942. By 1956, five million copies of the ''Oz'' books had been published in the English language, while hundreds of thousands had been published in eight foreign languages.

Adaptations

''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' has been adapted to other media numerous times. Within several decades after its publication, the book had inspired a number of stage and screen adaptations, including a profitable 1902 Broadway musical and three silent films. The most popular cinematic adaptation of the story is '' The Wizard of Oz'', the 1939 film starringJudy Garland

Judy Garland (born Frances Ethel Gumm; June 10, 1922June 22, 1969) was an American actress and singer. While critically acclaimed for many different roles throughout her career, she is widely known for playing the part of Dorothy Gale in '' The ...

, Ray Bolger

Raymond Wallace Bolger (January 10, 1904 – January 15, 1987) was an American actor, dancer, singer, vaudevillian and stage performer (particularly musical theatre) who started in the silent-film era.

Bolger was a major Broadway performer in ...

, Jack Haley

John Joseph Haley Jr. (August 10, 1897 – June 6, 1979) was an American actor, comedian, dancer, radio host, singer and vaudevillian. He was best known for his portrayal of the Tin Man and his farmhand counterpart Hickory in the 1939 Metro-G ...

, and Bert Lahr

Irving Lahrheim (August 13, 1895 – December 4, 1967), known professionally as Bert Lahr, was an American actor. He was best known for his role as the Cowardly Lion, as well as his counterpart Kansas farmworker "Zeke", in the MGM adaptation of ...

. The 1939 film was considered innovative because of its special effects

Special effects (often abbreviated as SFX, F/X or simply FX) are illusions or visual tricks used in the theatre, film, television, video game, amusement park and simulator industries to simulate the imagined events in a story or virtual wor ...

and revolutionary use of Technicolor

Technicolor is a series of Color motion picture film, color motion picture processes, the first version dating back to 1916, and followed by improved versions over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black and white films ...

.

The story has been translated into other languages (at least once without permission, resulting in Alexander Volkov's ''The Wizard of the Emerald City

''The Wizard of the Emerald City'' (russian: Волшебник Изумрудного Города) is a 1939 children's novel by Russian writer Alexander Melentyevich Volkov. The book is a re-narration of L. Frank Baum's ''The Wonderful Wizard ...

'' novel and its sequels, which were translated into English by Sergei Sukhinov) and adapted into comics several times. Following the lapse of the original copyright, the characters have been adapted and reused in spin-offs, unofficial sequels, and reinterpretations, some of which have been controversial in their treatment of Baum's characters.

Influence and legacy

''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' has become an established part of multiple cultures, spreading from its early young American readership to becoming known throughout the world. It has been translated or adapted into nearly every major language, at times being modified in local variations. For instance, in some abridged Indian editions, the Tin Woodman was replaced with a horse. In Russia, a translation byAlexander Melentyevich Volkov

Alexander Melentyevich Volkov (russian: Александр Мелентьевич Волков ; 14 June 1891 – 3 July 1977) was a Soviet novelist, playwright, university lecturer. Аuthor of novels, short stories, plays and poems for chil ...

produced six books, ''The Wizard of the Emerald City

''The Wizard of the Emerald City'' (russian: Волшебник Изумрудного Города) is a 1939 children's novel by Russian writer Alexander Melentyevich Volkov. The book is a re-narration of L. Frank Baum's ''The Wonderful Wizard ...

'' series, which became progressively distanced from the Baum version, as Ellie and her dog Totoshka travel throughout the Magic Land. The 1939 film adaptation has become a classic of popular culture, shown annually on American television from 1959 to 1998 and then several times a year every year beginning in 1999.

In 1974, the story was re-envisioned as ''The Wiz

''The Wiz: The Super Soul Musical "Wonderful Wizard of Oz"'' is a Musical theatre, musical with music and lyrics by Charlie Smalls (and others) and book by William F. Brown (writer), William F. Brown. It is a retelling of L. Frank Baum's childr ...

'', a Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual cer ...

winning musical featuring an all-Black cast and set in the context of modern African-American culture

African-American culture refers to the contributions of African Americans to the culture of the United States, either as part of or distinct from mainstream American culture. The culture is both distinct and enormously influential on Ame ...

. This musical was adapted in 1978 as the feature film ''The Wiz

''The Wiz: The Super Soul Musical "Wonderful Wizard of Oz"'' is a Musical theatre, musical with music and lyrics by Charlie Smalls (and others) and book by William F. Brown (writer), William F. Brown. It is a retelling of L. Frank Baum's childr ...

'', a musical adventure fantasy produced by Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

and Motown Productions

Motown Records is an American record label owned by the Universal Music Group. It was founded by Berry Gordy Jr. as Tamla Records on June 7, 1958, and incorporated as Motown Record Corporation on April 14, 1960. Its name, a portmanteau of ''moto ...

.

There were several Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

translations published in Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. As established in the first translation and kept in later ones, the book's ''Land of Oz

The Land of Oz is a magical country introduced in the 1900 children's novel ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' written by L. Frank Baum and illustrated by W. W. Denslow.

Oz consists of four vast quadrants, the Gillikin Country in the north, Quadli ...

'' was rendered in Hebrew as ''Eretz Uz'' (ארץ עוץ)—i.e. the same as the original Hebrew name of the Biblical ''Land of Uz

The land of Uz ( he, אֶרֶץ־עוּץ – ''ʾereṣ-ʿŪṣ'') is a location mentioned in the Old Testament, most prominently in the Book of Job, which begins, "There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job".

The name "Uz" is ...

'', homeland of Job

Work or labor (or labour in British English) is intentional activity people perform to support the needs and wants of themselves, others, or a wider community. In the context of economics, work can be viewed as the human activity that contr ...

. Thus, for Hebrew readers, this translators' choice added a layer of Biblical connotations absent from the English original.

In 2018, "The Lost Art of Oz" project was initiated to locate and catalogue the surviving original artwork John R. Neill, W. W. Denslow

William Wallace Denslow (; May 5, 1856 – March 29, 1915), professionally W. W. Denslow, was an American illustrator and caricaturist remembered for his work in collaboration with author L. Frank Baum, especially his illustrations of ''The ...

, Frank Kramer, Richard "Dirk" Gringhuis, and Dick Martin that was created to illustrate the ''Oz'' book series. In 2020, an Esperanto

Esperanto ( or ) is the world's most widely spoken constructed international auxiliary language. Created by the Warsaw-based ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof in 1887, it was intended to be a universal second language for international communi ...

translation of the novel was used by a team of scientists to demonstrate a new method for encoding text in DNA that remains readable after repeated copying.

See also

* 1900 in literature * ''The Baum Bugle

''The Baum Bugle: A Journal of Oz'' is the official journal of The International Wizard of Oz Club. The journal was founded in 1957, with its first issue released in June of that year (to a subscribers' list of sixteen). It publishes three times pe ...

''

* Wizard of Oz Club

* ''The Wiz

''The Wiz: The Super Soul Musical "Wonderful Wizard of Oz"'' is a Musical theatre, musical with music and lyrics by Charlie Smalls (and others) and book by William F. Brown (writer), William F. Brown. It is a retelling of L. Frank Baum's childr ...

''

* ''Wicked

Wicked may refer to:

Books

* Wicked, a minor character in the ''X-Men'' universe

* '' Wicked'', a 1995 novel by Gregory Maguire that inspired the musical of the same name

* ''Wicked'', the fifth novel in Sara Shepard's ''Pretty Little Liars'' s ...

''

* '' Tin Man (miniseries)''

* ''Lost in Oz (TV series)

''Lost in Oz'' is an American animated series that premiered in full on August 7, 2017 streaming on Amazon Prime Video. Originally part of a pilot program, the pilot episode was later re-released as ''Lost in Oz: Extended Adventure'' on November ...

''

* ''Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz

''Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz'' is an American animated children's television series loosely based on L. Frank Baum's 1900 novel '' The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' and its subsequent books, as well as its 1939 film adaptation. The series debute ...

''

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* Text: ** ** *''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' (1900 illustrated copy)

Publisher's green and red illustrated cloth over boards; illustrated endpapers. Plate detached. Public Domain – Charles E. Young Research Library,

UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California St ...

. at Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

*Online version of the 1900 first edition

on the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

website.

* Audio:

**

*''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum''

an unabridged dramatic audio performance at Wired for Books. *

A Long and Dangerous Journey – A History of ''The Wizard of Oz'' on the Silver Screen

– Scream-It-Loud.com * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wonderful Wizard Of Oz, The 1900 American novels 1900 children's books 1900 fantasy novels American fantasy novels adapted into films American novels adapted into plays American novels adapted into television shows Books about lions Censored books Farms in fiction Novels about orphans Novels adapted into comics Novels adapted into radio programs Novels adapted into video games Novels set in fictional countries Novels set in Kansas Oz (franchise) books Portal fantasy Witchcraft in written fiction Wizards in fiction