The War Of The Worlds on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The War of the Worlds'' is a

''The War of the Worlds'' is a

''The War of the Worlds'' is a

''The War of the Worlds'' is a science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

novel by English author H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

The narrative opens by stating that as humans on

The narrative opens by stating that as humans on  After heavy firing from the common and damage to the town from the heat ray which suddenly erupts in the late afternoon, the Narrator takes his wife to safety in nearby

After heavy firing from the common and damage to the town from the heat ray which suddenly erupts in the late afternoon, the Narrator takes his wife to safety in nearby  Towards dusk, the Martians renew their offensive, breaking through the defence line of

Towards dusk, the Martians renew their offensive, breaking through the defence line of

At the beginning of Book Two, the Narrator and the curate are plundering houses in search of food. During this excursion, the men witness a Martian handling machine enter

At the beginning of Book Two, the Narrator and the curate are plundering houses in search of food. During this excursion, the men witness a Martian handling machine enter  The Narrator's relations with the curate deteriorate over time, and eventually, he knocks him unconscious to silence his now loud ranting; the curate is overheard outside by a Martian, which eventually removes his unconscious body with one of its handling machine tentacles. The reader is then led to believe the Martians will perform a fatal transfusion of the curate's blood to nourish themselves, as they have done with other captured victims viewed by the Narrator through a small slot in the house's ruins. The Narrator just barely escapes detection from the returned foraging tentacle by hiding in the adjacent coal cellar.

Eventually, the Martians abandon the cylinder's crater, and the Narrator emerges from the collapsed house where he had observed the Martians up close during his ordeal; he then approaches

The Narrator's relations with the curate deteriorate over time, and eventually, he knocks him unconscious to silence his now loud ranting; the curate is overheard outside by a Martian, which eventually removes his unconscious body with one of its handling machine tentacles. The reader is then led to believe the Martians will perform a fatal transfusion of the curate's blood to nourish themselves, as they have done with other captured victims viewed by the Narrator through a small slot in the house's ruins. The Narrator just barely escapes detection from the returned foraging tentacle by hiding in the adjacent coal cellar.

Eventually, the Martians abandon the cylinder's crater, and the Narrator emerges from the collapsed house where he had observed the Martians up close during his ordeal; he then approaches

In 1895, Wells was an established writer and he married his second wife, Catherine Robbins, moving with her to the town of

In 1895, Wells was an established writer and he married his second wife, Catherine Robbins, moving with her to the town of

''The War of the Worlds'' was generally received very favourably by both readers and critics upon its publication. ''

''The War of the Worlds'' was generally received very favourably by both readers and critics upon its publication. ''

Between 1871 and 1914 more than 60 works of fiction for adult readers describing invasions of Great Britain were published. The seminal work was ''

Between 1871 and 1914 more than 60 works of fiction for adult readers describing invasions of Great Britain were published. The seminal work was ''

Many novels focusing on life on other planets written close to 1900 echo

Many novels focusing on life on other planets written close to 1900 echo

The Martian invasion's principal weapons are the Heat-Ray and the poisonous Black Smoke. Their strategy includes the destruction of infrastructure such as armament stores, railways, and telegraph lines; it appears to be intended to cause maximum casualties, leaving humans without any will to resist. These tactics became more common as the twentieth century progressed, particularly during the 1930s with the development of mobile weapons and technology capable of

The Martian invasion's principal weapons are the Heat-Ray and the poisonous Black Smoke. Their strategy includes the destruction of infrastructure such as armament stores, railways, and telegraph lines; it appears to be intended to cause maximum casualties, leaving humans without any will to resist. These tactics became more common as the twentieth century progressed, particularly during the 1930s with the development of mobile weapons and technology capable of

Wells's description of chemical weapons – the Black Smoke used by the Martian fighting machines to kill human beings in great numbers – became a reality in

Wells's description of chemical weapons – the Black Smoke used by the Martian fighting machines to kill human beings in great numbers – became a reality in

H. G. Wells was a student of

H. G. Wells was a student of

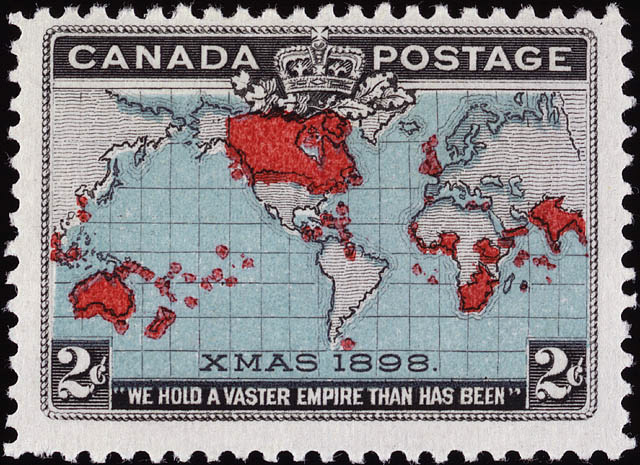

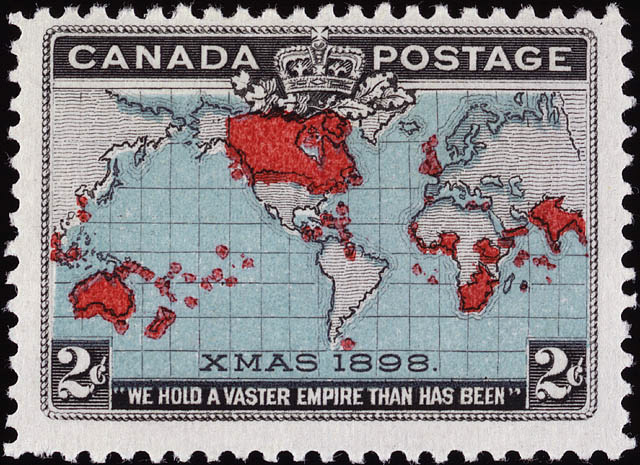

At the time of the novel's publication the British Empire had conquered and colonised dozens of territories in Africa, Oceania, North and South America, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, and the

At the time of the novel's publication the British Empire had conquered and colonised dozens of territories in Africa, Oceania, North and South America, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, and the

The novel originated several enduring Martian

The novel originated several enduring Martian

Six weeks after publication of the novel, ''

Six weeks after publication of the novel, ''

On 30 October 1988, a slightly updated version of the script by Howard Koch, adapted and directed by David Ossman, was presented by WGBH Radio, Boston and broadcast on

On 30 October 1988, a slightly updated version of the script by Howard Koch, adapted and directed by David Ossman, was presented by WGBH Radio, Boston and broadcast on

''The War of the Worlds Invasion''

large resource containing comment and review on the history of ''The War of the Worlds'' * * . *

Time Archives

a look at perceptions of ''The War of the Worlds'' over time

Hundreds of cover images

of the book's different editions, from 1898 to now {{DEFAULTSORT:War Of The Worlds, The 1898 British novels 1898 science fiction novels Alien invasions in novels War of the Worlds written fiction Novels by H. G. Wells Novels first published in serial form Works originally published in Pearson's Magazine Novels set in Surrey Heinemann (publisher) books Novels adapted into comics British novels adapted into films British novels adapted into plays Novels about extraterrestrial life Novels adapted into radio programs British novels adapted into television shows Novels adapted into video games Science fiction novels adapted into films Harper & Brothers books Books with cover art by Michael Koelsch

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Pearson's Magazine

''Pearson's Magazine'' was a monthly periodical that first appeared in Britain in 1896. A US version began publication in 1899. It specialised in speculative literature, political discussion, often of a socialist bent, and the arts. Its contribut ...

'' in the UK and by ''Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

'' magazine in the US. The novel's first appearance in hardcover was in 1898 from publisher William Heinemann

William Henry Heinemann (18 May 1863 – 5 October 1920) was an English publisher of Jewish descent and the founder of the Heinemann publishing house in London.

Early life

On 18 May 1863, Heinemann was born in Surbiton, Surrey, England. Heine ...

of London. Written between 1895 and 1897, it is one of the earliest stories to detail a conflict between mankind and an extra-terrestrial race. The novel is the first-person narrative

A first-person narrative is a mode of storytelling in which a storyteller recounts events from their own point of view using the first person It may be narrated by a first-person protagonist (or other focal character), first-person re-teller, ...

of both an unnamed protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

and of his younger brother in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

as southern England

Southern England, or the South of England, also known as the South, is an area of England consisting of its southernmost part, with cultural, economic and political differences from the Midlands and the North. Officially, the area includes G ...

is invaded by Martians

Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a setting in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s as the Moon was evidently lifeless. At the time, the pred ...

. The novel is one of the most commented-on works in the science fiction canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

.

The book's plot was similar to numerous works of invasion literature

Invasion literature (also the invasion novel) is a literary genre that was popular in the period between 1871 and the First World War (1914–1918). The invasion novel first was recognized as a literary genre in the UK, with the novella '' The B ...

which were published around the same period, and has been variously interpreted as a commentary on the theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

, British colonialism

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. I ...

, and Victorian-era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardi ...

fears, superstitions and prejudices. Wells later noted that an inspiration for the plot was the catastrophic effect of European colonisation on the Aboriginal Tasmanians

The Aboriginal Tasmanians (Palawa kani: ''Palawa'' or ''Pakana'') are the Aboriginal people of the Australian island of Tasmania, located south of the mainland. For much of the 20th century, the Tasmanian Aboriginal people were widely, and ...

; some historians have argued that Wells wrote the book in part to encourage his readership to question the morality of imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

. At the time of the book's publication, it was classified as a scientific romance

Scientific romance is an archaic, mainly British term for the genre of fiction now commonly known as science fiction. The term originated in the 1850s to describe both fiction and elements of scientific writing, but it has since come to refer to ...

, like Wells's earlier novel ''The Time Machine

''The Time Machine'' is a science fiction novella by H. G. Wells, published in 1895. The work is generally credited with the popularization of the concept of time travel by using a vehicle or device to travel purposely and selectively for ...

''.

''The War of the Worlds'' has been both popular (having never been out of print) and influential, spawning half a dozen feature films, radio dramas, a record album, various comic book adaptations, a number of television series, and sequels or parallel stories by other authors. It was memorably dramatised in a 1938 radio programme directed by and starring Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

that allegedly caused public panic among listeners who did not know the book's events were fictional. The novel has even influenced the work of scientists, notably Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first Liquid-propellant rocket, liquid-fueled rocket. ...

, who, inspired by the book, helped develop both the liquid-fuelled rocket and multistage rocket

A multistage rocket or step rocket is a launch vehicle that uses two or more rocket ''stages'', each of which contains its own engines and propellant. A ''tandem'' or ''serial'' stage is mounted on top of another stage; a ''parallel'' stage i ...

, which resulted in the Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, an ...

Moon landing

A Moon landing is the arrival of a spacecraft on the surface of the Moon. This includes both crewed and robotic missions. The first human-made object to touch the Moon was the Soviet Union's Luna 2, on 13 September 1959.

The United St ...

71 years later.

Plot

The Coming of the Martians

The narrative opens by stating that as humans on

The narrative opens by stating that as humans on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

busied themselves with their own endeavours during the mid-1890s, aliens on Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

began plotting an invasion of Earth because their own resources are dwindling. The Narrator (who is unnamed throughout the novel) is invited to an astronomical observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysical, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed. His ...

at Ottershaw

Ottershaw is a village in the Borough of Runnymede in Surrey, England, approximately southwest of central London. The village developed in the mid-19th century from a number of separate hamlets and became a parish in its own right in 1871.

The ...

where explosions are seen on the surface of the planet Mars, creating much interest in the scientific community. Months later, a so-called "meteor

A meteoroid () is a small rocky or metallic body in outer space.

Meteoroids are defined as objects significantly smaller than asteroids, ranging in size from grains to objects up to a meter wide. Objects smaller than this are classified as micr ...

" lands on Horsell Common

Horsell Common is a open space in Horsell, near Woking in Surrey. It is owned and managed by the Horsell Common Preservation Society. An area of is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest and part of the Thames Basin Heaths Special ...

, near the Narrator's home in Woking

Woking ( ) is a town and borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in northwest Surrey, England, around from central London. It appears in Domesday Book as ''Wochinges'' and its name probably derives from that of a Anglo-Saxon settlement o ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

. He is among the first to discover that the object is an artificial cylinder that opens, disgorging Martians who are "big" and "greyish" with "oily brown skin", "the size, perhaps, of a bear", each with "two large dark-coloured eyes", and lipless "V-shaped mouths" which drip saliva and are surrounded by two "Gorgon groups of tentacles". The Narrator finds them "at once vital, intense, inhuman, crippled and monstrous". They emerge briefly, but have difficulty in coping with the Earth's atmosphere and gravity, and so retreat rapidly into their cylinder.

A human deputation (which includes the astronomer Ogilvy) approaches the cylinder with a white flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire, and for negotiation. It is also used to symbolize ...

, but the Martians incinerate them and others nearby with a heat-ray

The Martians, also known as the Invaders, are the fictional race of extraterrestrials from the H.G. Wells 1898 novel ''The War of the Worlds''. They are the main antagonists of the novel, and their efforts to exterminate the populace of the Ear ...

before beginning to assemble their machinery. Military forces arrive that night to surround the common, bringing with them field artillery and Maxim gun

The Maxim gun is a recoil-operated machine gun invented in 1884 by Hiram Stevens Maxim. It was the first fully automatic machine gun in the world.

The Maxim gun has been called "the weapon most associated with imperial conquest" by historian M ...

s. The population of Woking and the surrounding villages are reassured by the presence of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

. A tense day begins, with much anticipation by the Narrator of military action.

After heavy firing from the common and damage to the town from the heat ray which suddenly erupts in the late afternoon, the Narrator takes his wife to safety in nearby

After heavy firing from the common and damage to the town from the heat ray which suddenly erupts in the late afternoon, the Narrator takes his wife to safety in nearby Leatherhead

Leatherhead is a town in the Mole Valley District of Surrey, England, about south of Central London. The settlement grew up beside a ford on the River Mole, from which its name is thought to derive. During the late Anglo-Saxon period, Leath ...

, where his cousin lives, using a rented, two-wheeled horse cart. He then returns to Woking to return the cart when in the early morning hours, a violent thunderstorm erupts. On the road during the height of the storm, he has his first terrifying sight of a fast-moving Martian fighting machine; in a panic, he crashes the horse cart, barely escaping detection. He discovers the Martians have assembled towering three-legged "fighting-machines" (tripods), each armed with a heat-ray and a chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

: the poisonous " black smoke". These tripods have wiped out the army units positioned around the cylinder and attacked and destroyed most of Woking. Taking shelter in his house, the Narrator sees a fleeing artilleryman

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, ...

moving through his garden, who later tells the Narrator of his experiences and mentions that another cylinder has landed between Woking and Leatherhead, which means the Narrator is now cut off from his wife. The two try to escape via Byfleet

Byfleet is a village in Surrey, England. It is located in the far east of the borough of Woking, around east of West Byfleet, from which it is separated by the M25 motorway and the Wey Navigation.

The village is of medieval origin. Its winding ...

just after dawn, but are separated at the Shepperton to Weybridge Ferry

The Shepperton to Weybridge Ferry is a pedestrian and cycle ferry service across the River Thames. The service has operated almost continuously for over 500 years.

Connected communities and landmarks

The ferry connects points remaining outside ...

during a Martian afternoon attack on Shepperton

Shepperton is an urban village in the Borough of Spelthorne, Surrey, approximately south west of central London. Shepperton is equidistant between the towns of Chertsey and Sunbury-on-Thames. The village is mentioned in a document of 959 AD ...

.

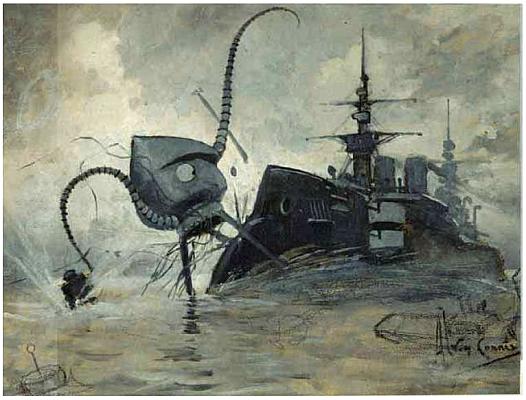

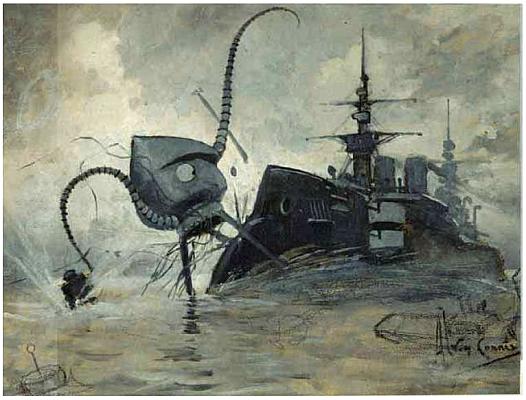

One of the Martian fighting machines is brought down in the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

by artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

as the Narrator and countless others try to cross the river into Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

, and the Martians retreat to their original crater. This gives the authorities precious hours to form a defence line covering London. After the Martians' temporary repulse, the Narrator is able to float down the Thames in a boat towards London, stopping at Walton Walton may refer to:

People

* Walton (given name)

* Walton (surname)

* Susana, Lady Walton (1926–2010), Argentine writer

Places

Canada

* Walton, Nova Scotia, a community

** Walton River (Nova Scotia)

*Walton, Ontario, a hamlet

United Kingdo ...

, where he first encounters the curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

, his companion for the coming weeks.

Towards dusk, the Martians renew their offensive, breaking through the defence line of

Towards dusk, the Martians renew their offensive, breaking through the defence line of siege gun

Siege artillery (also siege guns or siege cannons) are heavy guns designed to bombard fortifications, cities, and other fixed targets. They are distinct from field artillery and are a class of siege weapon capable of firing heavy cannonballs or ...

s and field artillery centred on Richmond Hill and Kingston Hill by a widespread bombardment of the black smoke; an exodus of the population of London begins. This includes the Narrator's younger brother, a medical student (also unnamed), who flees to the Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

coast, after the sudden, panicked, pre-dawn order to evacuate London is given by the authorities, on a terrifying and harrowing journey of three days, amongst thousands of similar refugees streaming from London. The brother encounters Mrs Elphinstone and her younger sister-in-law, just in time to help them fend off three men who are trying to rob them. Since Mrs Elphinstone's husband is missing, the three continue on together.

After a terrifying struggle to cross a streaming mass of refugees on the road at Barnet, they head eastward. Two days later, at Chelmsford

Chelmsford () is a city in the City of Chelmsford district in the county of Essex, England. It is the county town of Essex and one of three cities in the county, along with Southend-on-Sea and Colchester. It is located north-east of London a ...

, their pony is confiscated for food by the local Committee of Public Supply. They press on to Tillingham and the sea. There, they manage to buy passage to Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

on a small paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine that drives paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses wer ...

, part of a vast throng of shipping gathered off the Essex coast to evacuate refugees. The torpedo ram

A torpedo ram is a type of torpedo boat combining a ram with torpedo tubes. Incorporating design elements from the cruiser and the monitor, it was intended to provide small and inexpensive weapon systems for coastal defence and other littoral com ...

HMS ''Thunder Child'' destroys two attacking tripods before being destroyed by the Martians, although this allows the evacuation fleet to escape, including the ship carrying the Narrator's brother and his two travelling companions. Shortly thereafter, all organised resistance collapsed, and the Martians roam the shattered landscape unhindered.

The Earth under the Martians

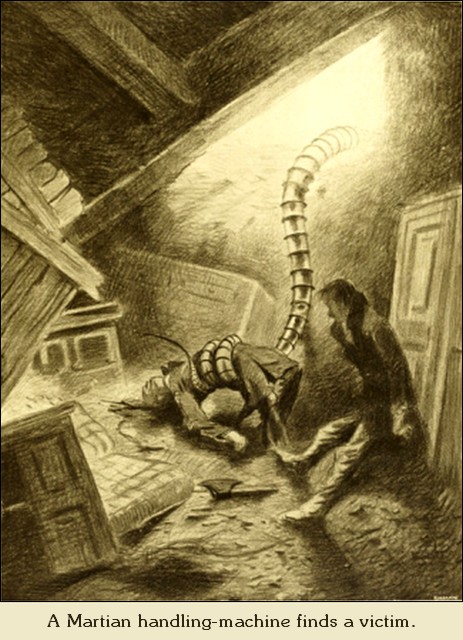

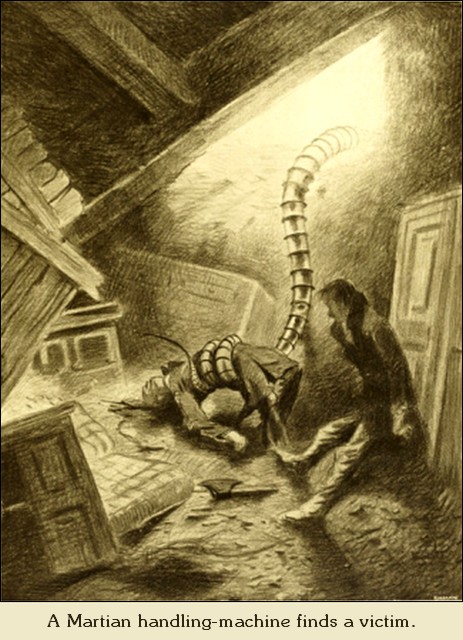

At the beginning of Book Two, the Narrator and the curate are plundering houses in search of food. During this excursion, the men witness a Martian handling machine enter

At the beginning of Book Two, the Narrator and the curate are plundering houses in search of food. During this excursion, the men witness a Martian handling machine enter Kew

Kew () is a district in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Its population at the 2011 census was 11,436. Kew is the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens ("Kew Gardens"), now a World Heritage Site, which includes Kew Palace. Kew is a ...

, seizing any person it finds and tossing them into a "great metallic carrier which projected behind him, much as a workman's basket hangs over his shoulder",Wells, ''The War of the Worlds'', Book Two, Ch. 1. and the Narrator realises that the Martian invaders may have "a purpose other than destruction" for their victims. At a house in Sheen

Sheen may refer to:

Places

* Sheen or West Sheen, an alternative name for Richmond, London, England

** East Sheen

** North Sheen

** Sheen Priory

* Sheen, Staffordshire, a village and civil parish in the Staffordshire Moorlands, England

* Sheenb ...

, "a blinding glare of green light" and a loud concussion attend the arrival of the fifth Martian cylinder, and both men are trapped beneath the ruins for two weeks.

The Narrator's relations with the curate deteriorate over time, and eventually, he knocks him unconscious to silence his now loud ranting; the curate is overheard outside by a Martian, which eventually removes his unconscious body with one of its handling machine tentacles. The reader is then led to believe the Martians will perform a fatal transfusion of the curate's blood to nourish themselves, as they have done with other captured victims viewed by the Narrator through a small slot in the house's ruins. The Narrator just barely escapes detection from the returned foraging tentacle by hiding in the adjacent coal cellar.

Eventually, the Martians abandon the cylinder's crater, and the Narrator emerges from the collapsed house where he had observed the Martians up close during his ordeal; he then approaches

The Narrator's relations with the curate deteriorate over time, and eventually, he knocks him unconscious to silence his now loud ranting; the curate is overheard outside by a Martian, which eventually removes his unconscious body with one of its handling machine tentacles. The reader is then led to believe the Martians will perform a fatal transfusion of the curate's blood to nourish themselves, as they have done with other captured victims viewed by the Narrator through a small slot in the house's ruins. The Narrator just barely escapes detection from the returned foraging tentacle by hiding in the adjacent coal cellar.

Eventually, the Martians abandon the cylinder's crater, and the Narrator emerges from the collapsed house where he had observed the Martians up close during his ordeal; he then approaches West London

West London is the western part of London, England, north of the River Thames, west of the City of London, and extending to the Greater London boundary.

The term is used to differentiate the area from the other parts of London: North London ...

. ''Enroute'', he finds the Martian red weed

The Martians, also known as the Invaders, are the fictional race of extraterrestrials from the H.G. Wells 1898 novel ''The War of the Worlds''. They are the main antagonists of the novel, and their efforts to exterminate the populace of the Ea ...

everywhere, prickly vegetation spreading wherever there is abundant water but slowly dying due to bacterial infection. On Putney Heath

Wimbledon Common is a large open space in Wimbledon, southwest London. There are three named areas: Wimbledon Common, Putney Heath, and Putney Lower Common, which together are managed under the name Wimbledon and Putney Commons totalling 46 ...

, once again he encounters the artilleryman, who persuades him of a grandiose plan to rebuild civilisation by living underground; after a few hours, the Narrator perceives the laziness of his companion and abandons him. Now in a deserted and silent London, slowly he begins to go mad from his accumulated trauma, finally attempting to end it all by openly approaching a stationary fighting machine. To his surprise, he discovers that all the Martians have been killed by an onslaught of earthly pathogens

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

, to which they had no immunity: "slain, after all, man's devices had failed, by the humblest things that God, in his wisdom, has put upon this earth".

The Narrator continues on, finally suffering a brief but complete nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

, which affects him for days; he is nursed back to health by a kind family. Eventually, he is able to return by train to Woking via a patchwork of newly repaired tracks. At his home, he discovers that his beloved wife has, somewhat miraculously, survived. In the last chapter, the Narrator reflects on the significance of the Martian invasion, its impact on humanity's view of itself and the future, and the "abiding sense of doubt and insecurity" it has left in his mind.

Style

''The War of the Worlds'' presents itself as a factual account of the Martian invasion. It is considered one of the first works to theorise the existence of a race intelligent enough to invade Earth. The Narrator is a middle-class writer of philosophical papers, somewhat reminiscent of Doctor Kemp in ''The Invisible Man

''The Invisible Man'' is a science fiction novel by H. G. Wells. Originally serialized in ''Pearson's Weekly'' in 1897, it was published as a novel the same year. The Invisible Man to whom the title refers is Griffin, a scientist who has devote ...

'', with characteristics similar to author Wells at the time of writing. The reader learns very little about the background of the Narrator or indeed of anyone else in the novel; characterisation is unimportant. In fact, none of the principal characters are named, aside from the astronomer Ogilvy.

Scientific setting

Wells trained as a science teacher during the latter half of the 1880s. One of his teachers wasThomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

, a major advocate of Darwinism

Darwinism is a scientific theory, theory of Biology, biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of smal ...

. He later taught science, and his first book was a biology textbook. He joined the scientific journal ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'' as a reviewer in 1894. Much of his work is notable for making contemporary ideas of science and technology easily understandable to readers.

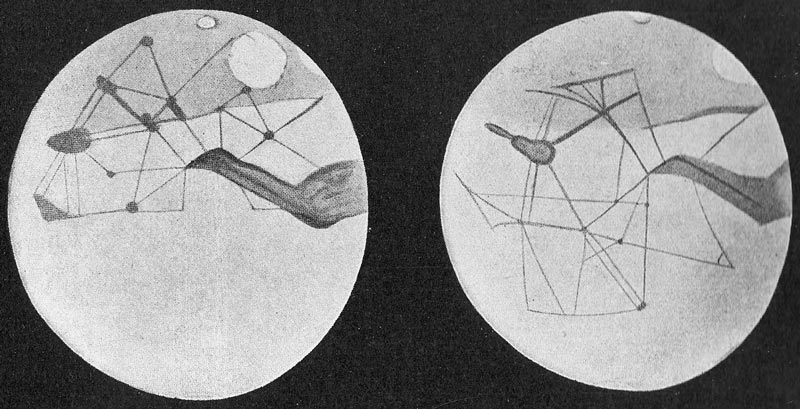

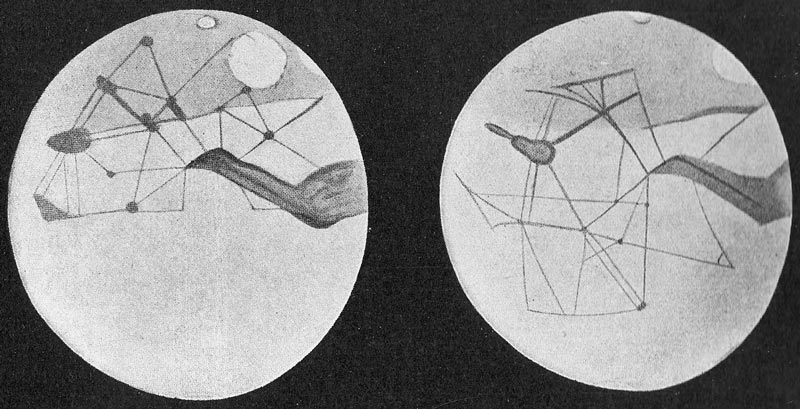

The scientific fascinations of the novel are established in the opening chapter where the Narrator views Mars through a telescope, and Wells offers the image of the superior Martians having observed human affairs, as though watching tiny organisms through a microscope. Ironically it is microscopic Earth lifeforms that finally prove deadly to the Martian invasion force. In 1894 a French astronomer observed a 'strange light' on Mars, and published his findings in the scientific journal ''Nature'' on the second of August that year. Wells used this observation to open the novel, imagining these lights to be the launching of the Martian cylinders toward Earth.

The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli

Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli ( , also , ; 14 March 1835 – 4 July 1910) was an Italian astronomer and science historian.

Biography

He studied at the University of Turin, graduating in 1854, and later did research at Berlin Observatory, ...

observed geological features on Mars in 1878 which he called canali (Italian for "channels"). This concept was explored by American astronomer Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System. ...

in the book ''Mars'' in 1895, speculating that these might be irrigation channels constructed by a sentient life form to support existence on an arid, dying world, similar to that which Wells suggests the Martians have left behind. The novel also presents ideas related to Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

, both in specific ideas discussed by the Narrator, and themes explored by the story.

Wells also wrote an essay titled 'Intelligence on Mars', published in 1896 in the '' Saturday Review'', which sets out many of the ideas for the Martians and their planet that are used almost unchanged in ''The War of the Worlds''. In the essay he speculates about the nature of the Martian inhabitants and how their evolutionary progress might compare to humans. He also suggests that Mars, being an older world than the Earth, might have become frozen and desolate, conditions that might encourage the Martians to find another planet on which to settle. Wells has also theorised how life could evolve in the conditions that are so hostile like those on Mars. The creatures have no digestive system, no appendages except tentacles and put the blood of other beings in their veins to survive. Wells was writing some years before 1901, when the Austrian Karl Landsteiner

Karl Landsteiner (; 14 June 1868 – 26 June 1943) was an Austrian-born American biologist, physician, and immunologist. He distinguished the main blood groups in 1900, having developed the modern system of classification of blood groups from ...

discovered the three human blood groups

The term human blood group systems is defined by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) as systems in the human species where cell-surface antigens—in particular, those on blood cells—are "controlled at a single gene locus or by ...

(O, A, and B), showing that even the blood of some humans can be lethal when introduced into the veins of other humans (if they belong to incompatible blood groups). But even before that discovery, it was clearly implausible that the blood of beings from one planet could be successfully introduced to the veins of creatures from another planet.

Physical location

Woking

Woking ( ) is a town and borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in northwest Surrey, England, around from central London. It appears in Domesday Book as ''Wochinges'' and its name probably derives from that of a Anglo-Saxon settlement o ...

in Surrey. There, he spent his mornings walking or cycling in the surrounding countryside, and his afternoons writing. The original idea for ''The War of the Worlds'' came from his brother during one of these walks, pondering on what it might be like if alien beings were suddenly to descend on the scene and start attacking its inhabitants.

Much of ''The War of the Worlds'' takes place around Woking and the surrounding area. The initial landing site of the Martian invasion force, Horsell Common

Horsell Common is a open space in Horsell, near Woking in Surrey. It is owned and managed by the Horsell Common Preservation Society. An area of is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest and part of the Thames Basin Heaths Special ...

, was an open area close to Wells' home. In the preface to the Atlantic edition of the novel, he wrote of his pleasure in riding a bicycle around the area, imagining the destruction of cottages and houses he saw by the Martian heat ray or their red weed. While writing the novel, Wells enjoyed shocking his friends by revealing details of the story, and how it was bringing total destruction to parts of the South London

South London is the southern part of London, England, south of the River Thames. The region consists of the Districts of England, boroughs, in whole or in part, of London Borough of Bexley, Bexley, London Borough of Bromley, Bromley, London Borou ...

landscape that was familiar to them. The characters of the artilleryman, the curate, and the brother medical student were also based on acquaintances in Woking and Surrey.

Wells wrote in a letter to Elizabeth Healey about his choice of locations: "I'm doing the dearest little serial for Pearson's new magazine, in which I completely wreck and sack Woking – killing my neighbours in painful and eccentric ways – then proceed via Kingston and Richmond to London, which I sack, selecting South Kensington

South Kensington, nicknamed Little Paris, is a district just west of Central London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically it settled on part of the scattered Middlesex village of Brompton. Its name was supplanted with ...

for feats of peculiar atrocity."

A high sculpture of a tripod fighting machine, entitled ''The Martian'', based on descriptions in the novel stands in Crown Passage close to the local railway station in Woking, designed and constructed by artist Michael Condron.

Cultural setting

Wells' depiction of late Victorian suburban culture in the novel was an accurate representation of his own experiences at the time of writing. In the late 19th century, theBritish Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

was the predominant colonial power on the globe, making its domestic heart a poignant and terrifying starting point for an invasion by Martians with their own imperialist agenda. He also drew upon a common fear which had emerged in the years approaching the turn of the century, known at the time as ''fin de siècle

() is a French term meaning "end of century,” a phrase which typically encompasses both the meaning of the similar English idiom "turn of the century" and also makes reference to the closing of one era and onset of another. Without context ...

'' or 'end of the age', which anticipated an apocalypse occurring at midnight on the last day of 1899.

Publication

In the late 1890s it was common for novels, prior to full volume publication, to be serialised in magazines or newspapers, with each part of the serialisation ending upon acliffhanger

A cliffhanger or cliffhanger ending is a plot device in fiction which features a main character in a precarious or difficult dilemma or confronted with a shocking revelation at the end of an episode or a film of serialized fiction. A cliffhang ...

to entice audiences to buy the next edition. This is a practice familiar from the first publication of Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

' novels earlier in the nineteenth century. ''The War of the Worlds'' was first published in serial form in the United Kingdom in ''Pearson's Magazine

''Pearson's Magazine'' was a monthly periodical that first appeared in Britain in 1896. A US version began publication in 1899. It specialised in speculative literature, political discussion, often of a socialist bent, and the arts. Its contribut ...

'' in April – December 1897. Wells was paid £200 and Pearsons demanded to know the ending of the piece before committing to publish. The complete volume was first published by William Heinemann

William Henry Heinemann (18 May 1863 – 5 October 1920) was an English publisher of Jewish descent and the founder of the Heinemann publishing house in London.

Early life

On 18 May 1863, Heinemann was born in Surbiton, Surrey, England. Heine ...

(of London publishing house Heinemann Heinemann may refer to:

* Heinemann (surname)

* Heinemann (publisher), a publishing company

* Heinemann Park, a.k.a. Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States

See also

* Heineman

* Jamie Hyneman

James Franklin Hyneman (born Se ...

) in 1898 and has been in print ever since.

Two unauthorised serialisations of the novel were published in the United States prior to the publication of the novel. The first was published in the ''New York Evening Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' between December 1897 and January 1898. The story was published as ''Fighters from Mars

''Fighters from Mars'' is the name of two unauthorized, edited versions of H. G. Wells' original ''The War of the Worlds'' serial.

The first version appeared in the '' New York Evening Journal'' between December 5, 1897 and January 11, 1898, an ...

or the War of the Worlds''. It changed the location of the story to a New York setting. The second version changed the story to have the Martians landing in the area near and around Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, and was published by ''The Boston Post

''The Boston Post'' was a daily newspaper in New England for over a hundred years before it folded in 1956. The ''Post'' was founded in November 1831 by two prominent Boston businessmen, Charles G. Greene and William Beals.

Edwin Grozier bough ...

'' in 1898, which Wells protested against. It was called ''Fighters from Mars, or the War of the Worlds in and near Boston''.

Both pirated versions of the story were followed by ''Edison's Conquest of Mars

''Edison's Conquest of Mars'' is an 1898 science fiction novel by American astronomer and writer Garrett P. Serviss. It was written as a sequel to ''Fighters from Mars'', an unauthorized and heavily altered version of H. G. Wells's 1897 story '' ...

'' by Garrett P. Serviss

Garrett Putnam Serviss (March 24, 1851 – May 25, 1929) was an American astronomer, popularizer of astronomy, and early science fiction writer. Serviss was born in Sharon Springs, New York and majored in science at Cornell University. He t ...

. Even though these versions are deemed as unauthorised serialisations of the novel, it is possible that H. G. Wells may have, without realising it, agreed to the serialisation in the ''New York Evening Journal''.

Holt, Rinehart & Winston

Holt McDougal is an American publishing company, a division of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, that specializes in textbooks for use in high schools.

The Holt name is derived from that of U.S. publisher Henry Holt (1840–1926), co-founder of the ...

re-pressed the book in 2000, paired with ''The Time Machine

''The Time Machine'' is a science fiction novella by H. G. Wells, published in 1895. The work is generally credited with the popularization of the concept of time travel by using a vehicle or device to travel purposely and selectively for ...

'', and commissioned Michael Koelsch to illustrate a new cover art.

Reception

''The War of the Worlds'' was generally received very favourably by both readers and critics upon its publication. ''

''The War of the Worlds'' was generally received very favourably by both readers and critics upon its publication. ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

'' wrote that Wells' work had "a very distinct success" when serialised in ''Pearson’s magazine''. The story did even better as a book, and reviewers rated it as "the very best work he has yet produced". The book's London publisher Heinemann had a plentiful supply of positive reviews for use in promotions, with reviewers highlighting the story's originality in representing Mars in a new light through the concept of an alien invasion of Earth.

Writing for ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'', Sidney Brooks admired Wells' writing style: "he has complete check over his imagination, and makes it effective by turning his most horrible of fancies into the language of the simplest, least startling denomination". Praising Wells' "power of vivid realization", '' The Daily News'' reviewer wrote, "the imagination, the extraordinary power of presentation, the moral significance of the book cannot be contested". There was, however, some criticism of the brutal nature of the events in the narrative.

Relation to invasion literature

Between 1871 and 1914 more than 60 works of fiction for adult readers describing invasions of Great Britain were published. The seminal work was ''

Between 1871 and 1914 more than 60 works of fiction for adult readers describing invasions of Great Britain were published. The seminal work was ''The Battle of Dorking

''The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer'' is an 1871 novella by George Tomkyns Chesney, starting the genre of invasion literature and an important precursor of science fiction. Written just after the Prussian victory in the Franc ...

'' (1871) by George Tomkyns Chesney

Sir George Tomkyns Chesney (30 April 1830 – 31 March 1895) was a British Army general, politician, and writer of fiction. He is remembered as the author of the novella ''The Battle of Dorking'' (1871), a founding work in the genre of invasion ...

, an army officer. The book portrays a surprise German attack, with a landing on the south coast of England, made possible by the distraction of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in colonial patrols and the army in an Irish insurrection. The German army makes short work of English militia and rapidly marches to London. The story was published in ''Blackwood's Magazine

''Blackwood's Magazine'' was a British magazine and miscellany printed between 1817 and 1980. It was founded by the publisher William Blackwood and was originally called the ''Edinburgh Monthly Magazine''. The first number appeared in April 1817 ...

'' in May 1871 and was so popular that it was reprinted a month later as a pamphlet which sold 80,000 copies.

The appearance of this literature reflected the increasing feeling of anxiety and insecurity as international tensions between European Imperial powers escalated towards the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Across the decades the nationality of the invaders tended to vary, according to the most acutely perceived threat at the time. In the 1870s the Germans were the most common invaders. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, a period of strain on Anglo-French relations, and the signing of a treaty between France and Russia, caused the French to become the more common menace.

There are a number of plot similarities between Wells's book and ''The Battle of Dorking''. In both books a ruthless enemy makes a devastating surprise attack, with the British armed forces helpless to stop its relentless advance, and both involve the destruction of the Home Counties

The home counties are the counties of England that surround London. The counties are not precisely defined but Buckinghamshire and Surrey are usually included in definitions and Berkshire, Essex, Hertfordshire and Kent are also often inc ...

of southern England. However ''The War of the Worlds'' transcends the typical fascination of invasion literature

Invasion literature (also the invasion novel) is a literary genre that was popular in the period between 1871 and the First World War (1914–1918). The invasion novel first was recognized as a literary genre in the UK, with the novella '' The B ...

with European politics, the suitability of contemporary military technology to deal with the armed forces of other nations, and international disputes, with its introduction of an alien adversary.

Although much of invasion literature may have been less sophisticated and visionary than Wells's novel, it was a useful, familiar genre to support the publication success of the piece, attracting readers used to such tales. It may also have proved an important foundation for Wells's ideas as he had never seen or fought in a war.

Scientific predictions and accuracy

Mars

Many novels focusing on life on other planets written close to 1900 echo

Many novels focusing on life on other planets written close to 1900 echo scientific

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

ideas of the time, including Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. He summarized ...

's nebular hypothesis

The nebular hypothesis is the most widely accepted model in the field of cosmogony to explain the formation and evolution of the Solar System (as well as other planetary systems). It suggests the Solar System is formed from gas and dust orbitin ...

, Charles Darwin's scientific theory

A scientific theory is an explanation of an aspect of the natural world and universe that has been repeatedly tested and corroborated in accordance with the scientific method, using accepted protocols of observation, measurement, and evaluatio ...

of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

, and Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff (; 12 March 1824 – 17 October 1887) was a German physicist who contributed to the fundamental understanding of electrical circuits, spectroscopy, and the emission of black-body radiation by heated objects.

He coine ...

's theory of spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter wa ...

. These scientific ideas combined to present the possibility that planets are alike in composition and conditions for the development of species, which would likely lead to the emergence of life at a suitable geological age in a planet's development.

By the time Wells wrote ''The War of the Worlds'', there had been three centuries of observation of Mars through telescopes. Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

observed the planet's phases in 1610 and in 1666 Giovanni Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini, also known as Jean-Dominique Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian (naturalised French) mathematician, astronomer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the C ...

identified the polar ice caps. In 1878 Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli

Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli ( , also , ; 14 March 1835 – 4 July 1910) was an Italian astronomer and science historian.

Biography

He studied at the University of Turin, graduating in 1854, and later did research at Berlin Observatory, ...

observed geological features which he called canali (Italian for "channels"). This was mistranslated into English as "canals" which, being artificial watercourses, fuelled the belief in intelligent extraterrestrial life on the planet. This further influenced American astronomer Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System. ...

.

In 1895 Lowell published a book titled ''Mars'', which speculated about an arid, dying landscape, whose inhabitants built canals to bring water from the polar caps to irrigate the remaining arable land. This formed the most advanced scientific ideas about the conditions on the red planet available to Wells at the time ''The War of the Worlds'' was written, but the concept was later proved erroneous by more accurate observation of the planet, and later landings by Russian and American probes such as the two Viking missions, that found a lifeless world too cold for water to exist in its liquid state.

Space travel

The Martians travel to the Earth incylinder

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infin ...

s, apparently fired from a huge space gun Space Gun may refer to:

* Space gun, a method of launching an object into space

* ''Space Gun'' (album), a 2018 album by Guided by Voices

* ''Space Gun'' (video game), a 1990 arcade game

* Ljutic Space Gun, a 12 gauge single-shot shotgun

See also

* ...

on the surface of Mars. This was a common representation of space travel in the nineteenth century, and had also been used by Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraor ...

in ''From the Earth to the Moon

''From the Earth to the Moon: A Direct Route in 97 Hours, 20 Minutes'' (french: De la Terre à la Lune, trajet direct en 97 heures 20 minutes) is an 1865 novel by Jules Verne. It tells the story of the Baltimore Gun Club, a post-American Civil W ...

''. Modern scientific understanding renders this idea impractical, as it would be difficult to control the trajectory of the gun precisely, and the force of the explosion necessary to propel the cylinder from the Martian surface to the Earth would likely kill the occupants.

However, the 16-year-old Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first Liquid-propellant rocket, liquid-fueled rocket. ...

was inspired by the story and spent much of his life building rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

s. The work of the German rocket scientists Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Konstantin Ts ...

and his student Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

led to the V-2 rocket

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed ...

becoming the first artificial object to travel into space by crossing the Kármán line

The Kármán line (or von Kármán line ) is an attempt to define a boundary between Earth's atmosphere and outer space, and offers a specific definition set by the Fédération aéronautique internationale (FAI), an international record-keeping ...

on 20 June 1944, and rocket developments culminated in the Apollo program's human landing on the Moon, and the landing of robotic probes on Mars.

Total war

The Martian invasion's principal weapons are the Heat-Ray and the poisonous Black Smoke. Their strategy includes the destruction of infrastructure such as armament stores, railways, and telegraph lines; it appears to be intended to cause maximum casualties, leaving humans without any will to resist. These tactics became more common as the twentieth century progressed, particularly during the 1930s with the development of mobile weapons and technology capable of

The Martian invasion's principal weapons are the Heat-Ray and the poisonous Black Smoke. Their strategy includes the destruction of infrastructure such as armament stores, railways, and telegraph lines; it appears to be intended to cause maximum casualties, leaving humans without any will to resist. These tactics became more common as the twentieth century progressed, particularly during the 1930s with the development of mobile weapons and technology capable of surgical strike

A surgical strike is a military attack which is intended to damage only a legitimate military target, with no or minimal collateral damage to surrounding structures, vehicles, buildings, or the general public infrastructure and utilities.

Descr ...

s on key military and civilian targets.

Wells's vision of a war bringing total destruction without moral limitations in ''The War of the Worlds'' was not taken seriously by readers at the time of publication. He later expanded these ideas in the novels ''When the Sleeper Wakes

''The Sleeper Awakes'' is a dystopian science fiction novel by English writer H. G. Wells, about a man who sleeps for two hundred and three years, waking up in a completely transformed London in which he has become the richest man in the world ...

'' (1899), ''The War in the Air

''The War in the Air: And Particularly How Mr. Bert Smallways Fared While It Lasted'' is a military science fiction novel written by H. G. Wells.

The novel was written in four months in 1907, and was serialized and published in 1908 in ''The ...

'' (1908), and ''The World Set Free

''The World Set Free'' is a novel written in 1913 and published in 1914 by H. G. Wells. The book is based on a prediction of a more destructive and uncontrollable sort of weapon than the world has yet seen. It had appeared first in serialised ...

'' (1914). This kind of total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

did not become fully realised until the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Critic Howard Black wrote that "In concrete details the Martian Fighting Machines as depicted by Wells have nothing in common with tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engin ...

s or dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s, but the tactical and strategic use made of them is strikingly reminiscent of Blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air su ...

as it would be developed by the German armed forces four decades later. The description of the Martians advancing inexorably, at lightning speed, towards London; the British Army completely unable to put up an effective resistance; the British government disintegrating and evacuating the capital; the mass of terrified refugees clogging the roads, all were to be precisely enacted in real life at 1940 France." Black regarded this 1898 depiction as far closer to the actual land fighting of World War II than Wells's much later work ''The Shape of Things to Come

''The Shape of Things to Come'' is a work of science fiction by British writer H. G. Wells, published in 1933. It takes the form of a future history which ends in 2106.

Synopsis

A long economic slump causes a major war that leaves Europe dev ...

'' (1933).

Weapons and armour

Wells's description of chemical weapons – the Black Smoke used by the Martian fighting machines to kill human beings in great numbers – became a reality in

Wells's description of chemical weapons – the Black Smoke used by the Martian fighting machines to kill human beings in great numbers – became a reality in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The comparison between laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word "laser" is an acronym for "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation". The fir ...

s and the Heat-Ray was made as early as the later half of the 1950s when lasers were still in development. Prototypes of mobile laser weapons have been developed and are being researched and tested as a possible future weapon in space.

Military theorists of the era, including those of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

prior to the First World War, had speculated about building a "fighting-machine" or a "land dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

". Wells later further explored the ideas of an armoured fighting vehicle

An armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) is an armed combat vehicle protected by armour, generally combining operational mobility with offensive and defensive capabilities. AFVs can be wheeled or tracked. Examples of AFVs are tanks, armoured car ...

in his short story "The Land Ironclads

"The Land Ironclads" is a short story by British writer H. G. Wells, which originally appeared in the December 1903 issue of the '' Strand Magazine''. It features tank-like "land ironclads," armoured fighting vehicles that carry riflemen, engi ...

". There is a high level of science fiction abstraction in Wells's description of Martian automotive technology; he stresses how Martian machinery is devoid of wheels. They use "a complicated system of sliding parts" to produce movement, possess multiple whip-like tentacles for grasping, and paralleling animal motion, "quasi-muscles abounded in the crablike handling machine".

Interpretations

Natural selection

H. G. Wells was a student of

H. G. Wells was a student of Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

, a proponent of the theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

. In the novel, the conflict between mankind and the Martians is portrayed as a survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

, with the Martians whose longer period of successful evolution on the older Mars has led to them developing a superior intelligence, able to create weapons far in advance of humans on the younger planet Earth, who have not had the opportunity to develop sufficient intelligence to construct similar weapons.

Human evolution

The novel also suggests a potential future for human evolution and perhaps a warning against overvaluing intelligence against more human qualities. The Narrator describes the Martians as having evolved an overdeveloped brain, which has left them with cumbersome bodies, with increased intelligence, but a diminished ability to use their emotions, something Wells attributes to bodily function. The Narrator refers to an 1893 publication suggesting that the evolution of the human brain might outstrip the development of the body, and organs such as the stomach, nose, teeth, and hair would wither, leaving humans as thinking machines, needing mechanical devices much like the Tripod fighting machines, to be able to interact with their environment. This publication is probably Wells's own "The Man of the Year Million", first published in ''The Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'' on 6 November 1893, which suggests similar ideas.

Colonialism and imperialism

At the time of the novel's publication the British Empire had conquered and colonised dozens of territories in Africa, Oceania, North and South America, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, and the

At the time of the novel's publication the British Empire had conquered and colonised dozens of territories in Africa, Oceania, North and South America, the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia, and the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

and Pacific islands

Collectively called the Pacific Islands, the islands in the Pacific Ocean are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of se ...

.

While invasion literature had provided an imaginative foundation for the idea of the heart of the British Empire being conquered by foreign forces, it was not until ''The War of the Worlds'' that the reading public was presented with an adversary completely superior to themselves. A significant motivating force behind the success of the British Empire was its use of sophisticated technology; the Martians, also attempting to establish an empire on Earth, have technology superior to their British adversaries. In ''The War of the Worlds'', Wells depicted an imperial power as the victim of imperial aggression, and thus perhaps encouraging the reader to consider imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

itself.

Wells suggests this idea in the following passage:

Social Darwinism

The novel also dramatises the ideas of race presented inSocial Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

, in that the Martians exercise over humans their 'rights' as a superior race, more advanced in evolution.

Social Darwinism suggested that the success of these different ethnic groups in world affairs, and social classes in a society, were the result of evolutionary struggle in which the group or class more fit to succeed did so; i.e., the ability of an ethnic group to dominate other ethnic groups or the chance to succeed or rise to the top of society was determined by genetic superiority. In more modern times it is typically seen as dubious and unscientific for its apparent use of Darwin's ideas to justify the position of the rich and powerful, or dominant ethnic groups.

Wells himself matured in a society wherein the merit of an individual was not considered as important as their social class of origin. His father was a professional sportsman, which was seen as inferior to 'gentle' status; whereas his mother had been a domestic servant, and Wells himself was, prior to his writing career, apprenticed to a draper. Trained as a scientist, he was able to relate his experiences of struggle to Darwin's idea of a world of struggle; but perceived science as a rational system, which extended beyond traditional ideas of race, class and religious notions, and in fiction challenged the use of science to explain political and social norms of the day.

Religion and science

Good and evil appear relative in ''The War of the Worlds'', and the defeat of the Martians has an entirely material cause: the action of microscopic bacteria. An insane clergyman is important in the novel, but his attempts to relate the invasion toArmageddon

According to the Book of Revelation in the New Testament of the Christian Bible, Armageddon (, from grc, Ἁρμαγεδών ''Harmagedōn'', Late Latin: , from Hebrew: ''Har Məgīddō'') is the prophesied location of a gathering of armies ...

seem examples of his mental derangement. His death, as a result of his evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

outbursts and ravings attracting the attention of the Martians, appears an indictment of his obsolete religious attitudes; but the Narrator twice prays to God, and suggests that bacteria may have been divinely allowed to exist on Earth for a reason such as this, suggesting a more nuanced critique.

Influences

Mars and Martians

The novel originated several enduring Martian

The novel originated several enduring Martian trope

Trope or tropes may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Trope (cinema), a cinematic convention for conveying a concept

* Trope (literature), a figure of speech or common literary device

* Trope (music), any of a variety of different things ...

s in science fiction writing. These include Mars being an ancient world, nearing the end of its life, being the home of a superior civilisation capable of advanced feats of science and engineering, and also being a source of invasion forces, keen to conquer the Earth. The first two tropes were prominent in Edgar Rice Burroughs