Terek Cossacks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

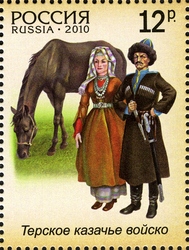

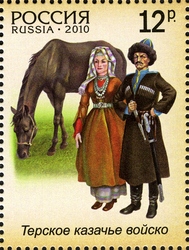

The Terek Cossack Host (russian: –¢–µ—Ä—Å–∫–æ–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞—á—å–µ –≤–æ–π—Å–∫–æ, ''Terskoye kazach'ye voysko'') was a

In 1711

In 1711

The

The

The end of the Caucasus War marked the end of the Line Cossack Host. In 1860 it was divided, with the two western regiments joining the

The end of the Caucasus War marked the end of the Line Cossack Host. In 1860 it was divided, with the two western regiments joining the

Until 1914 the Terek Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black

Until 1914 the Terek Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black

During the

During the

Terek Cossack Host

- official website

Cossack host

A Cossack host ( uk, козацьке військо, translit=kozatske viisko; russian: каза́чье во́йско, ''kazachye voysko''), sometimes translated as Cossack army, was an administrative subdivision of Cossack

The Cossac ...

created in 1577 from free Cossack

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

s who resettled from the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the List of rivers of Europe#Rivers of Europe by length, longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Cas ...

to the Terek River

The Terek (; , Tiyrk; , Tərč; , ; , ; , ''Terk''; , ; , ) is a major river in the Northern Caucasus. It originates in the Mtskheta-Mtianeti region of Georgia (country), Georgia and flows through North Caucasus region of Russia into the Casp ...

. The local aboriginal Terek Cossacks joined this Cossack host later. In 1792 it was included in the Caucasus Line Cossack Host

Caucasus Line Cossack Host (–ö–∞–≤–∫–∞–∑—Å–∫–æ–µ –ª–∏–Ω–µ–π–Ω–æ–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞—á—å–µ –≤–æ–π—Å–∫–æ) was a Cossack host created in 1832 for the purpose of conquest of the Northern Caucasus. Together with the Black Sea Cossack Host it defended the Cauc ...

and separated from it again in 1860, with the capital of Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz (russian: Владикавка́з, , os, Дзæуджыхъæу, translit=Dzæwdžyqæw, ;), formerly known as Ordzhonikidze () and Dzaudzhikau (), is the capital city of the North Ossetia-Alania, Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, Ru ...

. In 1916 the population of the Host was 255,000 within an area of 1.9 million desyatina A dessiatin or desyatina (russian: –¥–µ—Å—è—Ç–∏–Ω–∞) is an archaic, rudimentary land measurement used in tsarist Russia. A dessiatin is equal to 2,400 square sazhens and is approximately equivalent to 2.702 English acres or 10,926.512 square metres ...

s.

Early history

It is unclear how the first Cossack community appeared on the Terek. One theory is that they were descendants of the Khazar state and of theTmutarakan

Tmutarakan ( rus, –¢–º—É—Ç–∞—Ä–∞–∫–∞ÃÅ–Ω—å, p=tm ät…ôr…êÀàkan ≤, ; uk, –¢–º—É—Ç–æ—Ä–æ–∫–∞–Ω—å, Tmutorokan) was a medieval Kievan Rus' principality and trading town that controlled the Cimmerian Bosporus, the passage from the Black Sea to the Sea ...

Principality, as there are records indicating that Mstislav of Tmutarakan

Mstislav Vladimirovich (; ; ) was the earliest attested prince of Tmutarakan and Chernigov in Kievan Rus'. He was a younger son of Vladimir the Great, Grand Prince of Kiev. His father appointed him to rule Tmutarakan, an important fortress by t ...

in the Battle of Listveno in 1023 had Cossacks on his side when he destroyed the army of Yaroslav the Wise

Yaroslav the Wise or Yaroslav I Vladimirovich; russian: –Ø—Ä–æ—Å–ª–∞–≤ –ú—É–¥—Ä—ã–π, ; uk, –Ø—Ä–æ—Å–ª–∞–≤ –ú—É–¥—Ä–∏–π; non, Jarizleifr Valdamarsson; la, Iaroslaus Sapiens () was the Grand Prince of Kiev from 1019 until his death. He was als ...

. This would mean the Slavic peoples of the Caucasus are native to the region having settled there much earlier.) But later Terek Cossacks assimilated the first Terek Cossacks and introduced their own new agriculture.

The earliest known records of Slavic settlements on the lower Terek River

The Terek (; , Tiyrk; , Tərč; , ; , ; , ''Terk''; , ; , ) is a major river in the Northern Caucasus. It originates in the Mtskheta-Mtianeti region of Georgia (country), Georgia and flows through North Caucasus region of Russia into the Casp ...

date to 1520 when the Ryazan Principality

The Grand Duchy of Ryazan (1078–1521) was a duchy with the capital in Old Ryazan ( destroyed by the Mongol Empire in 1237), and then in Pereyaslavl Ryazansky, which later became the modern-day city of Ryazan. It originally split off from the ...

was annexed by the Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: –í–µ–ª–∏–∫–æ–µ –∫–Ω—è–∂–µ—Å—Ç–≤–æ –ú–æ—Å–∫–æ–≤—Å–∫–æ–µ, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

and a lone group left and settled in the natural haven of the Terek River (modern northern Chechnya). The early settlement was located at the mouth of the Aktash River. This formed the oldest Cossack group, the Greben Cossacks (–ì—Ä–µ–±–µ–Ω—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏ ''Grebenskiye Kazaki'') who settled on both banks of the river.

In 1559–71 the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I i ...

, in the course of several campaigns, built several fortifications, during which the first Terka was built, later taken over by the still independent Cossacks. In 1577, after the Volga Cossacks

The Povolzyhe Cossacks or Volga Cossacks (russian: –í–æ–ª–∂—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏) were free Cossack communities in Russia which were recorded in sources from the 16th century on. They inhabited the areas along the Volga River.

The Volga Cossac ...

were defeated by the strelets

, image = 01 106 Book illustrations of Historical description of the clothes and weapons of Russian troops.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption =

, dates = 1550–1720

, disbanded =

, country = Tsardom of Russia

, allegiance = Streltsy D ...

Ivan Murashkin, many scattered, some of whom settled in the Terek basin and Voevoda

Voivode (, also spelled ''voievod'', ''voevod'', ''voivoda'', ''vojvoda'' or ''wojewoda'') is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe since the Early Middle Ages. It primarily referred to the me ...

Novosiltsev built the second Terka on the Terek, marking the start of the Terek Cossacks. In 1584 this Terka was again taken over by Cossacks, some of whom were recruited by the Georgian king Simon I of Kartli

Simon I the Great ( ka, სიმონ I დიდი), also known as Svimon ( ka, სვიმონი) (1537–1611), of the Bagrationi dynasty, was a Georgian king of Kartli from 1556 to 1569 and again from 1578 to 1599. His first tenure wa ...

.

In a separate story, an ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; Russian: –∞—Ç–∞–º–∞–Ω, uk, –æ—Ç–∞–º–∞–Ω) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military comman ...

of the Don Cossack

Don Cossacks (russian: –î–æ–Ω—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏, Donskie kazaki) or Donians (russian: –¥–æ–Ω—Ü—ã, dontsy) are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (russian: –î–æ– ...

Host named Andrei Shadrin led a band of three Cossack sotnia

Sotnia (Ukrainian and ) was a military unit and administrative division in many Slavic countries.

Sotnia, deriving back to 1948, has been used in a variety of contexts in both Ukraine and Russia to this day. It is a helpful word to create sh ...

s to the Kumyk lands, founding a frontier town called 'Tersky' (location uncertain). This may have been partially motivated by his tense relations with Yermak Timofeyevich

Yermak Timofeyevich ( rus, –ï—Ä–º–∞ÃÅ–∫ –¢–∏–º–æ—Ñ–µÃÅ–µ–≤–∏—á, p=j…™Ààrmak t ≤…™m…êÀàf ≤ej…™v ≤…™t…ï; born between 1532 and 1542 ‚Äì August 5 or 6, 1585) was a Cossack ataman and is today a hero in Russian folklore and myths. During the reign ...

. He subsequently founded Andreyevo (the modern Endirey

Endirey (russian: –≠–Ω–¥–∏—Ä–µ–π; OKATO: 82254815001) is a village (''selo'') in the Khasavyurt District of the Republic of Dagestan in Russia. It is the center of the Endireyskoe Rural Settlement and has a population of 7,863 (2015). Endirey ...

), which was said to be named for him..

In the late 16th century several campaigns by the Terek Cossacks were carried out against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(Temryuk

Temryuk ( rus, –¢–µ–º—Ä—éÃÅ–∫, p=t ≤…™mÀàr ≤ âk) is a town and the administrative center of Temryuksky District in Krasnodar Krai, Russia, located on the Taman Peninsula on the right bank of the Kuban River not far from its entry into the Temr ...

) which led the Sultan to complain to Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич; 25 August 1530 – ), commonly known in English as Ivan the Terrible, was the grand prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and the first Tsar of all Russia from 1547 to 1584.

Ivan ...

. In 1589 the first outpost on the Sunzha was built and a permanent Terka, later known as Tersky Gorodok, was built on the lower Terek.

17th century

During theTime of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (russian: –°–º—É—Ç–Ω–æ–µ –≤—Ä–µ–º—è, ), or Smuta (russian: –°–º—É—Ç–∞), was a period of political crisis during the Tsardom of Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Fyodor I (Fyodor Ivanovich, the last of the Rurik dy ...

in 1606 four thousand Terek Cossacks left for the Volga to support their own candidate for the Tsar, Ileyka Muromets. By 1614 the Rowers supported the new Romanov monarch and aided him in quelling the unrest in Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, –ê—Å—Ç—Ä–∞—Ö–∞–Ω—å, p=Ààastr…ôx…ôn ≤) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the ...

. In 1633 they destroyed the remnants of the Nogay Horde

The Nogai Horde was a confederation founded by the Nogais that occupied the Pontic–Caspian steppe from about 1500 until they were pushed west by the Kalmyks and south by the Russians in the 17th century. The Mongol tribe called the Manghuds cons ...

and a decade later aided the Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (russian: –î–æ–Ω—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏, Donskie kazaki) or Donians (russian: –¥–æ–Ω—Ü—ã, dontsy) are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (russian: –î–æ– ...

against the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to ...

in 1646. By the mid 17th century the Cossacks again expanded into the Sunzha where they built a new outpost in 1651. Two years later the outpost withstood a hailing attack by Kumyks

, image = Abdul-Wahab son of Mustafa — a prominent Kumyk architect of the 19th century.

, population = near 600,000

, region1 =

, pop1 = 503,060

, ref1 =

, region2 =

, pop2 ...

and Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; rus, –î–∞–≥–µ—Å—Ç–∞ÃÅ–Ω, , d…ô…° ≤…™Ààstan, links=yes), officially the Republic of Dagestan (russian: –Ý–µ—Å–ø—ÉÃÅ–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –î–∞–≥–µ—Å—Ç–∞ÃÅ–Ω, Resp√∫blika Dagest√°n, links=no), is a republic of Russia situated in the North C ...

is. Though the battle ensured the Tsar's respect, it was advised that the Cossacks pull down the outpost. In the 1670s the Terek Cossacks helped to defeat Stenka Razin

Stepan Timofeyevich Razin (russian: –°—Ç–µ–ø–∞ÃÅ–Ω –¢–∏–º–æ—Ñ–µÃÅ–µ–≤–∏—á –Ý–∞ÃÅ–∑–∏–Ω, ; 1630 ‚Äì ), known as Stenka Razin ( ), was a Cossack leader who led a major uprising against the nobility and tsarist bureaucracy in southern Russia in 1 ...

in Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, –ê—Å—Ç—Ä–∞—Ö–∞–Ω—å, p=Ààastr…ôx…ôn ≤) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the ...

.

In 1680 after the Raskol

The Schism of the Russian Church, also known as Raskol (russian: —Ä–∞—Å–∫–æ–ª, , meaning "split" or " schism"), was the splitting of the Russian Orthodox Church into an official church and the Old Believers movement in the mid-17th century. It ...

in the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

reached the Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (russian: –î–æ–Ω—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏, Donskie kazaki) or Donians (russian: –¥–æ–Ω—Ü—ã, dontsy) are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (russian: –î–æ– ...

, a number of Old Believers

Old Believers or Old Ritualists, ''starovery'' or ''staroobryadtsy'' are Eastern Orthodox Christians who maintain the liturgical and ritual practices of the Russian Orthodox Church as they were before the reforms of Patriarch Nikon of Moscow bet ...

left the Don River and settled first on the Kuma and later on the Agrakhan

The Agrakhan Peninsula (russian: –ê–≥—Ä–∞—Ö–∞–Ω—Å–∫–∏–π –ø–æ–ª—É–æ—Å—Ç—Ä–æ–≤) is a narrow peninsula in the Caspian Sea. It is located on the northwestern Caspian coast. The peninsula stretches northwards in a N/S orientation. It is long and narrow ...

. After the aid of the Terek and Rowing Cossacks to the Don Cossacks during the Azov Campaigns

Azov (russian: –ê–∑–æ–≤), previously known as Azak,

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. Population:

History

Early settlements in the vicinity

The mout ...

in 1695, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

retaliated against the Terek Cossacks and in 1707 most of their outposts were destroyed on the right bank of the Terek.

18th century

In 1711

In 1711 Graf

(feminine: ) is a historical title of the German nobility, usually translated as "count". Considered to be intermediate among noble ranks, the title is often treated as equivalent to the British title of "earl" (whose female version is "coun ...

Apraskin re-settled all of the Rowing Cossacks on the left bank of the Terek River, this move was met with resentment, and during the entire 18th century the Terek Cossacks would still inhabit the left bank and use the rich vineyards and lands right up until 1799. Also in 1720 the Rowers and Tereks were fully incorporated into the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

and during the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723)

The Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723, known in Russian historiography as the Persian campaign of Peter the Great, was a war between the Russian Empire and Safavid Iran, triggered by the tsar's attempt to expand Russian influence in the Caspian ...

, the Cossacks aided Peter I of Russia

Peter I ( ‚Äì ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Aleks√©yevich ( rus, –ü—ë—Ç—Ä –ê–ª–µ–∫—Å–µÃÅ–µ–≤–∏—á, p=Ààp ≤…µtr …êl ≤…™Ààks ≤ej…™v ≤…™t…ï, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

in his conquest of the eastern Dagestan and the capture of Derbent

Derbent (russian: Дербе́нт; lez, Кьвевар, Цал; az, Дәрбәнд, italic=no, Dərbənd; av, Дербенд; fa, دربند), formerly romanized as Derbend, is a city in Dagestan, Russia, located on the Caspian Sea. It is ...

. During the campaign the 1000 re-settled Don Cossacks on the Agrakhan and the Sulak formed the Agrakhan Cossack Host (''–ê–≥—Ä–∞—Ö–∞–Ω—Å–∫–æ–µ –ö–∞–∑–∞—á—å–µ –í–æ–π—Å–∫–æ''), which was united with the Terek Cossacks. In 1735 by a new agreement with Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

the Sulak line was abandoned, and Agrakhan Cossacks were re-settled on the lower Terek Delta, and the fort of Kizlyar

Kizlyar (russian: Кизля́р; av, Гъизляр; kum, Къызлар, ''Qızlar'') is a town in the Republic of Dagestan, Russia, located on the border with the Chechen Republic in the delta of the Terek River northwest of Makhachkala, ...

was founded.

Thus in 1735 three hosts were formed: Grebenskoye (''–ì—Ä–µ–±–µ–Ω—Å–∫–æ–µ'' Rowing) from the descendants of the earliest Cossacks, Tersko-Semeynoye (''–¢–µ—Ä—Å–∫–æ-–°–µ–º–µ–π–Ω–æ–µ'' Terek-Family) from the re-settled Agrakhan Cossacks up to Kizlyar, and Tersko-Kizlyarskoye (''–¢–µ—Ä—Å–∫–æ-–ö–∏–∑–ª—è—Ä—Å–∫–æ–µ'' Terek-Kizlyar) from the Agrakhan Cossacks as well as Armenians and Georgians. When the Kalmyks

The Kalmyks ( Kalmyk: Хальмгуд, ''Xaľmgud'', Mongolian: Халимагууд, ''Halimaguud''; russian: Калмыки, translit=Kalmyki, archaically anglicised as ''Calmucks'') are a Mongolic ethnic group living mainly in Russia, w ...

arrived in the northwestern Caspian a combined campaign was waged against Temryuk

Temryuk ( rus, –¢–µ–º—Ä—éÃÅ–∫, p=t ≤…™mÀàr ≤ âk) is a town and the administrative center of Temryuksky District in Krasnodar Krai, Russia, located on the Taman Peninsula on the right bank of the Kuban River not far from its entry into the Temr ...

during the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739 between Russia and the Ottoman Empire was caused by the Ottoman Empire's war with Persia and continuing raids by the Crimean Tatars. The war also represented Russia's continuing struggle for access to the ...

, where the Terek Cossacks were led by Atamans Auka and Petrov.

In 1736 and again in 1765 the right bank of the Terek, still nominally Cossack property, was offered to Chechens

The Chechens (; ce, Нохчий, , Old Chechen: Нахчой, ''Naxçoy''), historically also known as ''Kisti'' and ''Durdzuks'', are a Northeast Caucasian ethnic group of the Nakh peoples native to the North Caucasus in Eastern Europe. "Europ ...

who wanted to adopt Russian patronage and re-settle there (noting that historically, the lands immediately north of the Terek river were indeed Chechen before the Mongol invasion and even to a degree after it, and the Chechen highlands were dependent on their agricultural production). By the latter half of the 18th century, relations between the Cossacks and the mountain people

Hill people, also referred to as mountain people, is a general term for people who live in the hills and mountains.

This includes all rugged land above and all land (including plateaus) above elevation.

The climate is generally harsh, with s ...

began to sour. In 1765 the outpost of Mozdok

Mozdok (russian: Моздо́к; os, Мæздæг, ''Mæzdæg''; Kabardian: Мэздэгу) is a town and the administrative center of Mozdoksky District of North Ossetia – Alania, Russia, located on the left shore of the Terek River, n ...

was founded, which became an immediate target for Kabardins

The Kabardians (Kabardian Adyghe dialect, Highland Adyghe: –ö—ä—ç–±—ç—Ä–¥–µ–π –∞–¥—ã–≥—ç—Ö—ç—Ä; West Adyghe dialect, Lowland Adyghe: –ö—ä—ç–±—ç—Ä—Ç–∞–π –∞–¥—ã–≥—ç—Ö—ç—Ä; russian: –ö–∞–±–∞—Ä–¥–∏–Ω—Ü—ã) or Kabardinians are one of the twelve ma ...

who attacked the Terek line and Kizlyar. In 1771 Yemelyan Pugachev

Yemelyan Ivanovich Pugachev (russian: –ï–º–µ–ª—å—è–Ω –ò–≤–∞–Ω–æ–≤–∏—á –ü—É–≥–∞—á—ë–≤; c. 1742) was an ataman of the Yaik Cossacks who led a great popular insurrection during the reign of Catherine the Great. Pugachev claimed to be Catherine's ...

arrived in Terek, and, to show loyalty, Ataman Tatarintsev arrested him. Pugachev fled and the Pugachev Rebellion

Pugachev's Rebellion (, ''Vosstaniye Pugachyova''; also called the Peasants' War 1773–1775 or Cossack Rebellion) of 1773–1775 was the principal revolt in a series of popular rebellions that took place in the Russian Empire after Catherine ...

in 1772–1774 gained no support on the Terek.

Caucasus War (1770s–1860s)

The

The Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 was a major armed conflict that saw Russian arms largely victorious against the Ottoman Empire. Russia's victory brought parts of Moldavia, the Yedisan between the rivers Bug and Dnieper, and Crimea into the ...

and the resulting Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ( tr, Küçük Kaynarca Antlaşması; russian: Кючук-Кайнарджийский мир), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kayna ...

gave Russia the pretext under which they could begin their expansion into the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

, marking the start of the century-long Caucasus War

The Caucasian War (russian: –ö–∞–≤–∫–∞–∑—Å–∫–∞—è –≤–æ–π–Ω–∞; ''Kavkazskaya vojna'') or Caucasus War was a 19th century military conflict between the Russian Empire and various peoples of the North Caucasus who resisted subjugation during the R ...

. In 1769–1770 almost half of the Volga Cossacks

The Povolzyhe Cossacks or Volga Cossacks (russian: –í–æ–ª–∂—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏) were free Cossack communities in Russia which were recorded in sources from the 16th century on. They inhabited the areas along the Volga River.

The Volga Cossac ...

were re-settled around Mozdok. In 1776 further settlers arrived including more of the Volga Cossacks

The Povolzyhe Cossacks or Volga Cossacks (russian: –í–æ–ª–∂—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏) were free Cossack communities in Russia which were recorded in sources from the 16th century on. They inhabited the areas along the Volga River.

The Volga Cossac ...

(the remaining Cossacks on the lower Volga were separated into the Astrakhan Cossacks Host) and the Khopyor Cossacks from the eastern Don territory. These formed the Azov

Azov (russian: –ê–∑–æ–≤), previously known as Azak,

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. Population:

History

Early settlements in the vicinity

The mo ...

-Mozdok defence line. Major foreposts for Russian expansion into the central Caucasus were founded by the re-settlers including: Giorgiyevsk in 1777 by the Khopyor regiment, and Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz (russian: Владикавка́з, , os, Дзæуджыхъæу, translit=Dzæwdžyqæw, ;), formerly known as Ordzhonikidze () and Dzaudzhikau (), is the capital city of the North Ossetia-Alania, Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, Ru ...

in 1784.

During this early phase several high-profile battles took place. In June 1774 Devlet-Girey sent a massive Kabardin Army against the Terek Cossacks, on 10-11 of June the stanitsa of Naurskaya

Naurskaya (russian: –ù–∞—É—Ä—Å–∫–∞—è, ce, –ù–æ–≤—Ä-–ì”Ä–∞–ª–∞, ''Novr-ƒÝala'') is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, rural locality (a ''village#Russia, stanitsa'') and the administrative center of Naursky District, the Chechnya, Chechen R ...

was heroically defended against the invaders and in 1785 Kizlyar was defended against Sheikh Mansur. In 1788–91 the Terek Cossacks took part in three campaigns which took them to the Circassian port of Anapa

Anapa (russian: Ана́па, ) is a town in Krasnodar Krai, Russia, located on the northern coast of the Black Sea near the Sea of Azov. Population:

History

The area around Anapa was settled in antiquity. It was originally a major seaport ( ...

in western Caucasus. The major gap in the western section of the line of defense was solved in 1792 when the Black Sea Cossacks

Black Sea Cossack Host (russian: Черномо́рское каза́чье во́йско; uk, Чорномо́рське коза́цьке ві́йсько ), also known as Chernomoriya (russian: Черномо́рия), was a Cossack host ...

were re-settled there.

The next three decades brought severe difficulties for the Russian effort in the Caucasus. After the joining of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

to Russia in 1801 and the subsequent Russo-Persian War (1804–1813)

The 1804–1813 Russo-Persian War was one of the many wars between the Persian Empire and Imperial Russia, and began like many of their wars as a territorial dispute. The new Persian king, Fath Ali Shah Qajar, wanted to consolidate the north ...

, the Terek Cossacks spared some men and took part in combat under Yerevan

Yerevan ( , , hy, Երևան , sometimes spelled Erevan) is the capital and largest city of Armenia and one of the world's List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities. Situated along the Hrazdan River, Y ...

, but on the whole most of them were in constant defence of their home lines. All this changed when in 1816 General Yermolov took command of the Caucasus army. Having by now secured major strategic footholds in most of the North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

and Georgia following the last war fought with Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and the resulting Treaty of Gulistan

The Treaty of Gulistan (russian: Гюлистанский договор; fa, عهدنامه گلستان) was a peace treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and Iran on 24 October 1813 in the village of Gulistan (now in the Goranboy Distri ...

, he found himself able to make major adjustments. In 1818 he changed the Russian tactics from defensive to offensive and began building the Sunzha-Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz (russian: Владикавка́з, , os, Дзæуджыхъæу, translit=Dzæwdžyqæw, ;), formerly known as Ordzhonikidze () and Dzaudzhikau (), is the capital city of the North Ossetia-Alania, Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, Ru ...

line where strongholds such as Groznaya and Vnezapnaya were founded. Yermolov further reformed the whole structure of the Cossacks and in 1819 replaced elected Atamans with appointed commanders.

In Transcaucasia

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

, Cossacks took part in the Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 was sparked by the Greek War of Independence of 1821–1829. War broke out after the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II closed the Dardanelles to Russian ships and revoked the 1826 Akkerman Convention in retalia ...

where they participated in the Siege of Kars

The siege of Kars was the last major operation of the Crimean War. In June 1855, attempting to alleviate pressure on the defence of Sevastopol, Emperor Alexander II ordered General Nikolay Muravyov to lead his troops against areas of Ottoman ...

and other key battles. After Yermolov was recalled from the Caucasus, a new reform took place and the interim regiments in the central Caucasus were united with the three Hosts on the Terek to form the Caucasus Line Cossack Host

Caucasus Line Cossack Host (–ö–∞–≤–∫–∞–∑—Å–∫–æ–µ –ª–∏–Ω–µ–π–Ω–æ–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞—á—å–µ –≤–æ–π—Å–∫–æ) was a Cossack host created in 1832 for the purpose of conquest of the Northern Caucasus. Together with the Black Sea Cossack Host it defended the Cauc ...

(–ö–∞–≤–∫–∞–∑—Å–∫–æ–µ –ª–∏–Ω–µ–π–Ω–æ–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞—á—å–µ –≤–æ–π—Å–∫–æ, ''Kavkazskoye lineynoye kazachye voysko'') in 1832, and the new Nakazny Ataman was named Peter Verzilin. Several reforms followed: In 1836 the Kizlyar and Family regiments were united and made responsible for the Terek Delta, and in 1837 a Malorossiyan (Little Russia

Little Russia (russian: –ú–∞–ª–æ—Ä–æ—Å—Å–∏—è/–ú–∞–ª–∞—è –Ý–æ—Å—Å–∏—è, Malaya Rossiya/Malorossiya; uk, –ú–∞–ª–æ—Ä–æ—Å—ñ—è/–ú–∞–ª–∞ –Ý–æ—Å—ñ—è, Malorosiia/Mala Rosiia), also known in English as Malorussia, Little Rus' (russian: –ú–∞–ª–∞—è –Ý—É— ...

n) regiment (formed in 1831 to combat the November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in W ...

in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

) was resettled on the upper Terek north of Vladikavkaz. In 1842 the regiment was incorporated into the Line host. This was followed by the formation of the Sunzha regiment with its Ataman Sleptsov.

By this point the Russian control in the Caucasus had improved, with the initiative firmly in the Cossack hands. Most of the battles took place in Chechen and Dagestani territories far away from Cossack homes. During the 1840s several successful expeditions were mounted deep into the mountains. The Line Cossacks participated in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

(1853–1856) and finally in the closing phase of the Russian advance against Shamil Shamil (Arabic: شَامِل ''shāmil'') is a lesser common masculine Arabic name. The name is usually from the adjective which have several correlated meanings from the Arabic "complete, comprehensive, universal" but could also mean "embodying, pr ...

in 1859.

Terek Cossack Host 1860–1920s

The end of the Caucasus War marked the end of the Line Cossack Host. In 1860 it was divided, with the two western regiments joining the

The end of the Caucasus War marked the end of the Line Cossack Host. In 1860 it was divided, with the two western regiments joining the Black Sea Cossacks

Black Sea Cossack Host (russian: Черномо́рское каза́чье во́йско; uk, Чорномо́рське коза́цьке ві́йсько ), also known as Chernomoriya (russian: Черномо́рия), was a Cossack host ...

to form the Kuban Cossack Host

Kuban Cossacks (russian: –∫—É–±–∞–Ω—Å–∫–∏–µ –∫–∞–∑–∞–∫–∏, ''kubanskiye k–∞zaki''; uk, –∫—É–±–∞–Ω—Å—å–∫—ñ –∫–æ–∑–∞–∫–∏, ''kubanski kozaky''), or Kubanians (russian: –∫—É–±–∞–Ω—Ü—ã, ; uk, –∫—É–±–∞–Ω—Ü—ñ, ), are Cossacks who live in the Kuban re ...

and the remaining into the Terek Cossack Host. The next decade showed a gradual reform from military to civil control. In 1865 a permanent police force was formed, and in 1869 the Terek Oblast

The Terek Oblast was a province (''oblast'') of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire, roughly corresponding to the central part of Russia's North Caucasian Federal District. –¢he ''–æblast'' was created out of the former territories of t ...

was formed, consisting of eight mountainous districts (populated by indigenous people) and seven Cossack subdivisions. Several regimental reforms followed: Kizlyar and Rower as well as Mountain and Mozdok regiments were united into two (reducing the number of sub-divisions to five), and in 1871 a charter for Terek Cossacks was published.

From the 1870s onwards the Eastern Caucasus remained largely peaceful (if one discounts uprisings waged by the Chechens in the late 1870s and the occasional exchange of raids). However the Terek Cossacks took part in several Imperial Wars, including campaigns against Khiva

Khiva ( uz, Xiva/, خىۋا; fa, خیوه, ; alternative or historical names include ''Kheeva'', ''Khorasam'', ''Khoresm'', ''Khwarezm'', ''Khwarizm'', ''Khwarazm'', ''Chorezm'', ar, خوارزم and fa, خوارزم) is a district-level city ...

in 1873. During the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877‚Äì1878 ( tr, 93 Harbi, lit=War of ‚Äô93, named for the year 1293 in the Islamic calendar; russian: –Ý—É—Å—Å–∫–æ-—Ç—É—Ä–µ—Ü–∫–∞—è –≤–æ–π–Ω–∞, Russko-turetskaya voyna, "Russian‚ÄìTurkish war") was a conflict between th ...

the Terek Cossacks sent six cavalry regiments, one Guards squadron and one mounted artillery regiment to the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and a further seven regiments and mounted battery were mobilized against the rebelling Chechens and Dagestanis, who initiated an uprising against Tsarist authorities in 1878.

In the 1880s the arrival of the railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

and the discovery of oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

made the Terek Oblast one of the wealthiest in the Caucasus, resulting in a large growth in Cossack and indigenous mountain populations. This created friction on land ownership. The Cossacks held extensive fertile areas in the lowlands and steppes, whilst the indigenous mountain populations only held land in the mountainous zones. Peace was preserved, by a complex Russian policy of supporting loyal clan leaders and free supplies of food and goods The Terek Cossacks took part in campaigns against Geok-Tepe in 1879 and in 1885 up to the Afghan border in Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

.

Uniform and equipment

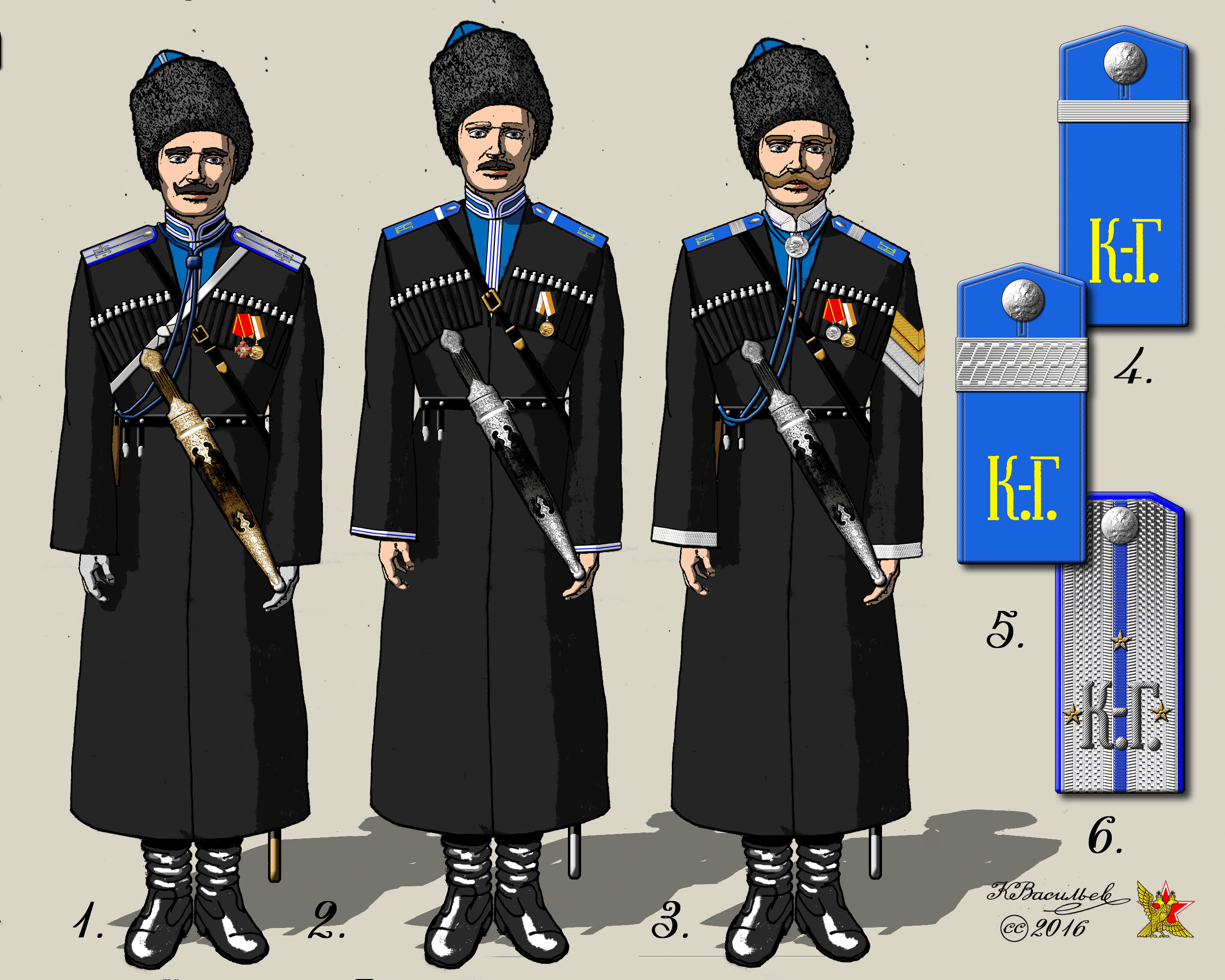

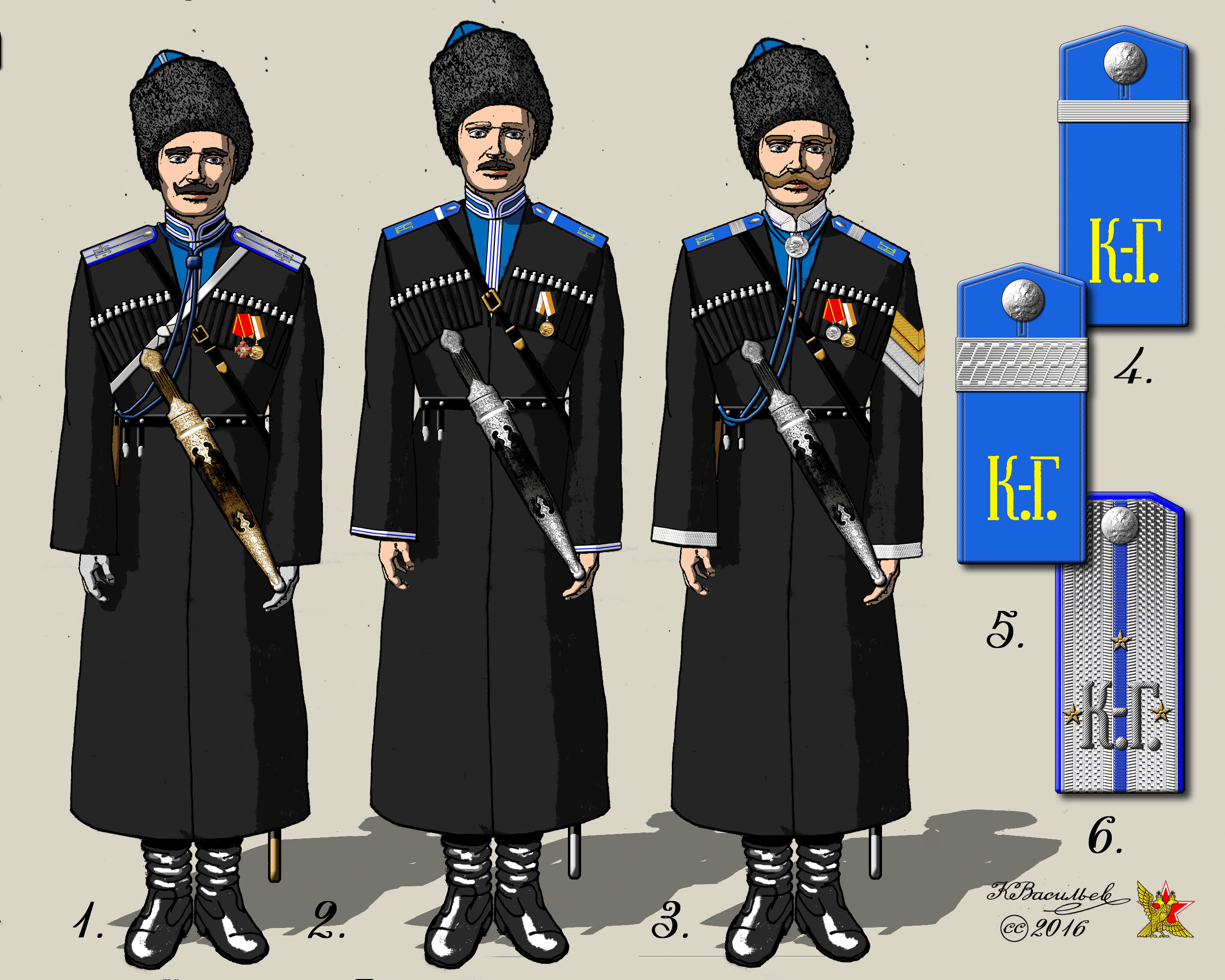

Until 1914 the Terek Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black

Until 1914 the Terek Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black kaftan

A kaftan or caftan (; fa, خفتان, ) is a variant of the robe or tunic. Originating in Asia, it has been worn by a number of cultures around the world for thousands of years. In Russian usage, ''kaftan'' instead refers to a style of men's l ...

(knee length collarless coat) with light blue shoulder straps and braid on the wide cuffs. Ornamental containers (''czerkeska'') which had originally contained single loading measures of gunpowder for muzzle-loading muskets, were worn on the breasts of the kaftans. The kaftan had an open front, showing a light blue waistcoat. Wide grey trousers were worn, tucked into soft leather boots without heels. Officers wore silver epaulettes, braiding and ferrules, the latter in their ''czerkeskas''. This Caucasian national dress was also worn by the Kuban Cossack Host but in different facing colors. Tall black fur hats were worn on all occasions with light blue cloth tops and (for officers) silver lace. A whip was used instead of spurs. Prior to 1908, individual cossacks from all Hosts were required to provide their own uniforms (together with horses, Caucasian saddles and harness). On active service during World War I the Terek Cossacks retained their distinctive dress but with a dark waistcoat replacing the conspicuous light blue one and without the silver ornaments or blue facings of full dress. A black felt cloak (''bourki'') was worn in bad weather both in peace-time and on active service.

The Terk and Kuban Cossacks of the Imperial Escort (''Konvoi'') wore a special gala uniform; including a scarlet kaftan edged with gold braid and a white waistcoat.

Soviet period

The arrival of theFebruary

February is the second month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars. The month has 28 days in common years or 29 in leap years, with the 29th day being called the ''leap day''. It is the first of five months not to have 31 days (th ...

and later the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

caught most Cossacks on the front lines in Kurdistan

Kurdistan ( ku, کوردستان ,Kurdistan ; lit. "land of the Kurds") or Greater Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural territory in Western Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, Kurdish la ...

. The unrequited mountainous peoples took full advantage of the crises, Chechens and Ingush on the Sunzha line wiping out several Cossack stanitsas.

In 1918, according to Peter Kenez

Peter Kenez (born as Péter Kenéz in 1937) is a historian specializing in Russian and Eastern European history and politics.

Life

Peter Kenez was born and grew up in Pesterzsébet, Budapest, Kingdom of Hungary . His father was arrested in March ...

, "The Bolsheviks were more successful in the nearby Terek. In November the Twelfth Red army defeated the Cossacks who fought independently of the Volunteer army

The Volunteer Army (russian: –î–æ–±—Ä–æ–≤–æ–ª—å—á–µ—Å–∫–∞—è –∞—Ä–º–∏—è, translit=Dobrovolcheskaya armiya, abbreviated to russian: –î–æ–±—Ä–∞—Ä–º–∏—è, translit=Dobrarmiya) was a White Army active in South Russia during the Russian Civil War from ...

." However, by January 1919, the defeat of the Eleventh Red Army foced the Twelfth to retreat from Terek towards Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, –ê—Å—Ç—Ä–∞—Ö–∞–Ω—å, p=Ààastr…ôx…ôn ≤) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the ...

. Yet, according to Kenez, "The Chechen and the Ingush were never subdued and their raids and risings made the Northern Caucasus a festering sore for the Volunteer Army."

In 1920 many Terek Cossacks were deported to Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and the northern part of European Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and a new Mountain ASSR

The Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic or Mountain ASSR ( rus, –ì–æÃÅ—Ä—Å–∫–∞—è –ê–°–°–Ý, r=Gorskaya ASSR; ce, –õ–∞—å–º–Ω–∏–π–Ω –ê–≤—Ç–æ–Ω–æ–º–∏–Ω –°–æ–≤–µ—Ç–∏–π–Ω –°–æ—Ü–∏–∞–ª–∏—Å—Ç–∏–π–Ω –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞) was a short-lived autono ...

was formed. This left the former Sunzha-Terek Mesopotamia triangle split by the returned Chechen land stretching through the middle. The remaining portions were formed by the Sunzha Cossack Okrug which also encompassed lands around Grozny. However, the Sunzha's importance to the Vainakh peoples as their historical territorial heart ensured that the early communists, mindful of the claims of indigenous peoples, would return it in order to turn them from the Mensheviks toward the Bolsheviks (to balance out the anti-Bolshevik Cossacks). A deadlock formed in the Northern Caucasus. On one hand, the Cossacks were very adverse to Bolshevism, and the latter responded with a Decossackization

De-Cossackization (Russian: –Ý–∞—Å–∫–∞–∑–∞—á–∏–≤–∞–Ω–∏–µ, ''Raskazachivaniye'') was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repressions against Cossacks of the Russian Empire, especially of the Don and the Kuban, between 1919 and 1933 aimed at the el ...

policy. On the other hand, many mountainous peoples were hostile to any Russian rule, Red or White (most originally looked to the Reds as a force also fighting against their foes, the Cossacks, but after the Reds began adopting similar policies as their Tzarist predecessors, resentment resurfaced), and continued fighting Russian/Cossack populations. In the end, the Red Army had to use Cossack tactics and hire local population to police the region. The idea of sandwiching a Cossack district within a Chechen autonomy was seen as a solution.

In the 1930s, to make the mountainous autonomies more sustainable in economical terms, they were united with the remaining Cossack holdings: the Sunzha district was retaken by the Chechen-Ingush ASSR

The Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic; inh, –ù–æ—Ö—á-–ì”Ä–∞–ª–≥”Ä–∞–π –ê–≤—Ç–æ–Ω–æ–º–µ –°–æ–≤–µ—Ç–∏–π –°–æ—Ü–∏–∞–ª–∏–∑–º–∞ –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞, Nox√ß-ƒÝalƒ°ay Avtonome Sovetiy Socializma Respublika; russian: –ß–µ—á–µÃÅ–Ω–æ-–ò ...

, the former capital of the Terek Oblast, Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz (russian: Владикавка́з, , os, Дзæуджыхъæу, translit=Dzæwdžyqæw, ;), formerly known as Ordzhonikidze () and Dzaudzhikau (), is the capital city of the North Ossetia-Alania, Republic of North Ossetia-Alania, Ru ...

became the administrative centre for North Ossetia

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

, likewise the Kabardino-Balkar Autonomous Oblast

The Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Oblast was an autonomous oblast within the Kabardino-Balkaria region of the Soviet Union. The Oblast was formed in 1921 as the Kabardin Autonomous Oblast before becoming the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Obl ...

was also awarded to Cossack territories. On the lower Terek, between 1923 and 1937, the Dagestan ASSR

The Dagestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic av, –î–∞–≥—ä–∏—Å—Ç–∞–Ω–∞–ª—ä—É–ª –ê–≤—Ç–æ–Ω–æ–º–∏—è–± –°–æ–≤–µ—Ç–∏—è–± –°–æ—Ü–∏–∞–ª–∏—Å—Ç–∏—è–± –ñ—É–º–≥—å—É—Ä–∏—è—Ç az, –î–∞“ì—ã—Å—Ç–∞–Ω –ú—É—Ö—Ç–∞—Ä –°–æ–≤–µ—Ç –°–æ—Å–∏–∞–ª–∏—Å—Ç –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏ ...

administered the extensive territory there (Kizlyar

Kizlyar (russian: Кизля́р; av, Гъизляр; kum, Къызлар, ''Qızlar'') is a town in the Republic of Dagestan, Russia, located on the border with the Chechen Republic in the delta of the Terek River northwest of Makhachkala, ...

, Terek Delta). Thus by the start of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

only the historical Terek Left-bank was not administered by autonomies. However, on the other hand, all these lands (northern Chechnya, Kizlyar, Little Kabarda, historical North Ossetia, East Prigorodny/Western Ingushetia, etc.) had historically been inhabited by Caucasian peoples before the end of the Caucasian Wars

The Caucasian War (russian: –ö–∞–≤–∫–∞–∑—Å–∫–∞—è –≤–æ–π–Ω–∞; ''Kavkazskaya vojna'') or Caucasus War was a 19th century military conflict between the Russian Empire and various peoples of the North Caucasus who resisted subjugation during the ...

.

Thus by the start of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

only the historical Terek Left-bank was not administered by autonomies, however, most of the administration and urban population of those regions was dominated by ethnic Russians. This was paralleled with the gradual down-folding of anti-Cossack repressions and their eventual rehabilitation by the mid-1930s, including forming numerous units in the Red Army.

Cossacks fought on both sides of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Many Cossack prisoners of war joined Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

who promised to free their lands from Bolshevism. Terek Cossacks made up the Vth regiment of the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Cossack Division. Soon the war came to Cossack lands themselves, in 1942 the Nazi offensive Case Blue

Case Blue (German: ''Fall Blau'') was the German Armed Forces' plan for the 1942 strategic summer offensive in southern Russia between 28 June and 24 November 1942, during World War II. The objective was to capture the oil fields of the Cauca ...

, and by autumn, the western regions of the former Terek Cossack Hosts were occupied. By November, the Battle of the Caucasus

The Battle of the Caucasus is a name given to a series of Axis and Soviet operations in the Caucasus area on the Eastern Front of World War II. On 25 July 1942, German troops captured Rostov-on-Don, Russia, opening the Caucasus region of t ...

reached North Ossetia, and Germans were already making plans to lease the oilfields in Grozny. Most of the Cossack population took part in repelling the invader.

During the 1920s and 30s, despite efforts of Soviet Union to pacify the mountainous peoples via different programmes, such as Korenizatsiya

Korenizatsiya ( rus, wikt:–∫–æ—Ä–µ–Ω–∏–∑–∞—Ü–∏—è, –∫–æ—Ä–µ–Ω–∏–∑–∞—Ü–∏—è, p=k…ôr ≤…™n ≤…™Ààzats…®j…ô, , "indigenization") was an early policy of the Soviet Union for the integration of non-Russian nationalities into the governments of their speci ...

, there was still low-level criminal secession movements in the highlands. Nazi Germany decided to use this friction in creating a fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

out of them. In the central Caucasus, these were the Karachay

The Karachays ( krc, Къарачайлыла, Qaraçaylıla or таулула, , 'Mountaineers') are an indigenous Caucasian Turkic ethnic group in the North Caucasus. They speak Karachay-Balkar, a Turkic language. They are mostly situat ...

and Balkars

The Balkars ( krc, Малкъарлыла, Malqarlıla or Таулула, , 'Mountaineers') are a Turkic people of the Caucasus region, one of the titular populations of Kabardino-Balkaria. Their Karachay-Balkar language is of the Ponto-Ca ...

who carried out low-level insurgency. Further east, these were the Vainakh

The Nakh peoples, also known as ''Vainakh peoples'' (Chechen/Ingush: , apparently derived from Chechen , Ingush "our people"; also Chechen-Ingush), are a group of Caucasian peoples identified by their use of the Nakh languages and other cult ...

s and an existing insurgency by a Khasan Israilov

Hasan Israilov ( ce, Исраил КIант Хьасан / ; russian: Хасан Исраилов ''Khasan Israilov''; 1910 – December 29, 1944) was a Chechen nationalist, guerrilla fighter, journalist, and poet who led Chechen and Ingush res ...

was fuelled by supplies via Nazi paradrops. By autumn 1942, the insurgency diverted significant Red Army resources, including aviation.

However, after the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later re ...

the Germans began a mass evacuation from the Caucasus. The price that mountainous people paid was dear, in late 1943 as part of Soviet Collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member of that group, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends and neighbors of the perpetrator. Because ind ...

, Operation Lentil began, which saw a total deportation of all Chechens, Ingush, Karachay and Balkar people to Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

. In the aftermath, most of the land was portioned, between loyal mountainous peoples such as Kabardins, Ossetians and Dagestanis, and Russians and Cossacks. For example, a vast Grozny Oblast

Grozny Oblast (russian: Гро́зненская о́бласть) was an administrative entity (an ''oblast'') of the Russian SFSR that was established as Grozny Okrug () on 7 March 1944 and abolished on 9 January 1957.

Formation

After the 194 ...

was created encompassing almost all of the historic lower-Terek Cossack lands, whilst North Ossetia took the Sunzha and Kabardin ASSR had central line cossack stanitsas.

This status quo continued until the second half of the 1950s, when there was once again a cool-down in Soviet government towards Cossacks after the death of Joseph Stalin. In 1957, all of the deported mountainous people were rehabilitated, and their republics restored. However this was not done in previous borders, for example, the historic homeland of lower Terek, Naursky and Schyolkovsky districts were incorporated into the Chechen-Ingush ASSR, whilst the Kizlyar district was passed onto Dagestan. Old problems of land ownership quickly resurfaced, and many returning Chechens and Ingush, forbidden to re-settle in the mountains, were settled in Cossack stanitsas.

The politics of Stagnationed USSR towards titular nations was also two-faced, on one hand all signs of nationalism were repressed, on the other hand Soviet authorities actively encouraged assignation of jobs and selection to the minorities rather than Russians. As a result, of the positive discrimination and better economic prospects in other regions of the USSR, many Russians migrated from the Northern Caucasus to other regions, such as the Tselina

Tselina or virgin lands (; ) is an umbrella term for underdeveloped, scarcely populated, high-fertility lands often covered with the chernozem soil. The lands were mostly located in the steppes of the Volga region, Northern Kazakhstan and Southern ...

, Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: –î–∞–ª—å–Ω–∏–π –í–æ—Å—Ç–æ–∫ –Ý–æ—Å—Å–∏–∏, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=Ààdal ≤n ≤…™j v…êÀàstok r…êÀàs ≤i…™) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admini ...

and the Baltic Republics

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

. Naturally, the high birth rate, of the mountainous peoples, meant that many sold their homes to them.

Although this hid the historic adversity between Russians and Caucasus people, it never removed the tension, as both sides saw each other gaining favours at their expense.

After 1990

During the

During the perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, –ø–µ—Ä–µ—Å—Ç—Ä–æ–π–∫–∞, p=p ≤…™r ≤…™Ààstrojk…ô, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

, Cossacks once again took steps to re-create their nationality . Many Cossack organisations were formed throughout the former Host. However, in doing so, many wished to review the existing administrative borders in the Northern Caucasus, and return the Cossack regions, that belonged to the once Terek Oblast

The Terek Oblast was a province (''oblast'') of the Caucasus Viceroyalty of the Russian Empire, roughly corresponding to the central part of Russia's North Caucasian Federal District. –¢he ''–æblast'' was created out of the former territories of t ...

from the national autonomies. In Kabardino-Balkaria

The Kabardino-Balkarian Republic (russian: –ö–∞–±–∞—Ä–¥–∏ÃÅ–Ω–æ-–ë–∞–ª–∫–∞ÃÅ—Ä—Å–∫–∞—è –Ý–µ—Å–ø—ÉÃÅ–±–ª–∏–∫–∞, ''Kabardino-Balkarskaya Respublika''; kbd, –ö—ä—ç–±—ç—Ä–¥–µ–π-–ë–∞–ª—ä–∫—ä—ç—Ä –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫—ç, ''ƒ∂√™b√™rdej-Baƒ∫ƒ∑√™r Respublik√ ...

and North Ossetia

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

and Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; rus, –î–∞–≥–µ—Å—Ç–∞ÃÅ–Ω, , d…ô…° ≤…™Ààstan, links=yes), officially the Republic of Dagestan (russian: –Ý–µ—Å–ø—ÉÃÅ–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –î–∞–≥–µ—Å—Ç–∞ÃÅ–Ω, Resp√∫blika Dagest√°n, links=no), is a republic of Russia situated in the North C ...

this was resolved by granting the Cossacks full minority rights, that raised on par with titular nations, and today Cossacks play an important role in local administration, culture and development.

In Chechnya and Ingushetia however, the situation was different. There was a long-running ethnic conflict between the Chechen returnees and the Russian settlers of the region. Before 1989, the Russians had dominated all parts of government as well as the workforce, but then this reversed with the "Chechen revolution" in 1990, where the Chechen and Ingush majority took control of the ruling of their homeland. Russians were left jobless as able Vainakh took their places. The Russian language remained in many schools and the Russians of the republic were not immediately made victims.

Cossacks and Russians, unsurprisingly, were staunch foes of Chechen independence from Russia. Chechens feared that Cossacks were variously plotting to undermine the independence which they saw as a desperate necessity and to detach a large part of their state. The chronic economic hardship of Chechnya during and after the Soviet period and the large income gap between Russians and Chechens before 1990 also worsened tensions. For these reasons and for the centuries of fighting between Cossacks and Chechens, ethnic relations were highly hostile.

President Dzhokhar Dudayev, himself married to a Russian, tried to suppress ethnic tensions, which he viewed as a destabilizing element to an already impoverished and internationally isolated republic. However, the statements of the President about "hospitality" were not convincing enough, and Dudayev had other priorities, such as handling the economic conditions inherited from the Soviet age and international isolation, another major problem.

An exodus of ethnic Russians occurred, although its causes and intensity are disputed. Some sources say that virtually the whole Russian population that left (300,000 people) before the First Chechen War, which others dispute, saying that while tens of thousands (as opposed to 300,000) left, most left due to the First Chechen War during it; Russian sources claim it was due to anti-Russian discrimination and violence, whereas others (such as Russian liberals Boris Lvin and Andrei Illarionov,Boris Lvin and Andrei Iliaronov. ''Moscow News''. 24 February – 2 March 1995 and Western commentators Gall and De Waal< see below) cite economic reasons and the loss of the previous disproportionate privilege held by the Russians during Soviet times, as well as the mass bombing of Grozny during the First Chechen War, where 4 out of 5 Russians in Chechnya lived. As noted by ethnic Russian economists Boris Lvin and Andrei Illiaronov, the rate and number of departures of ethnic Russians from Chechnya during 1991–94 was actually less than other areas (Kalmykia, Tuva and Yakutia).

There is also dispute that Chechens were antagonistic towards ethnic Russians and Cossacks because they were ethnic Russian (as opposed to because of their hostility to Chechen statehood) - there were two originally ethnic Russian Chechen teips, and the president's wife was Russian. The Chechen clan system protects individuals from theft and murder because the whole clan would become involved, and one can join a teip - thus, those who didn't join teips (like the Cossacks) would be subject to theft by the poor, etc.

Many of the educated elite also lost their positions in government, industry and academia to locals connected with those in power (which previously they had a vast advantage in due to the situation after the return of the Chechens from exile).http://www.chechnyaadvocacy.org/refugees.html Chechnya Advocacy Network. Refugees and Diaspora Nadteretchny, Naursky and Shelkovskoy ''raions'' of the Republic of Chechnya practically lost the traditional Cossack population.

After an attempted coup against Dudayev (who was seen as a threat to Russian oil transit) failed, Moscow responded with a military operation to reconquer Chechnya (see First Chechen War

The First Chechen War, also known as the First Chechen Campaign,, rmed conflict in the Chechen Republic and on bordering territories of the Russian Federation–§–µ–¥–µ—Ä–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã–π –∑–∞–∫–æ–Ω ‚Ññ 5-–§–ó –æ—Ç 12 —è–Ω–≤–∞—Ä—è 1995 (–≤ —Ä–µ–¥–∞– ...

); many Terek Cossacks jumped at the opportunity to show their loyalty, and formed volunteer units that operated with the Russian Army. These were created to fight in the Sunzha and Terek stanitsas against Chechens.

During the Second Chechen War

The Second Chechen War (russian: Втора́я чече́нская война́, ) took place in Chechnya and the border regions of the North Caucasus between the Russia, Russian Federation and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, from Augus ...

, once again Cossack units took part as an auxiliary support, and this time were allowed to establish in the Naursky raion, which still had a Russian minority; today the stanitsa of Naurskaya remains strongly associated with the Cossack movement in Chechnya.

The two wars have brought large suffering to both the Cossacks and the Chechens.

External links

Terek Cossack Host

- official website

References

{{authority control Ethnic groups in Russia Peoples of the Caucasus 1577 establishments in Russia Cossack hosts Terek Oblast Terek