Tender is the Night on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Tender Is the Night'' is the fourth and final

Dick and Nicole Diver are a glamorous couple who rent a villa in the

Dick and Nicole Diver are a glamorous couple who rent a villa in the

Fitzgerald deemed the novel to be his masterwork and believed it would eclipse the acclaim of his previous works. It was instead met with lukewarm sales and mixed reviews. One book review in ''

Fitzgerald deemed the novel to be his masterwork and believed it would eclipse the acclaim of his previous works. It was instead met with lukewarm sales and mixed reviews. One book review in ''

, novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

completed by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

. Set in French Riviera

The French Riviera (known in French as the ; oc, Còsta d'Azur ; literal translation " Azure Coast") is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France. There is no official boundary, but it is usually considered to extend fro ...

during the twilight of the Jazz Age, the 1934 novel chronicles the rise and fall of Dick Diver, a promising young psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry, the branch of medicine devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, study, and treatment of mental disorders. Psychiatrists are physicians and evaluate patients to determine whether their sy ...

, and his wife, Nicole, who is one of his patients. The story mirrors events in the lives of the author and his wife Zelda Fitzgerald

Zelda Fitzgerald (; July 24, 1900 – March 10, 1948) was an American novelist, painter, dancer, and socialite.

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, she was noted for her beauty and high spirits, and was dubbed by her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald a ...

as Dick starts his descent into alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol (drug), alcohol that results in significant Mental health, mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognize ...

and Nicole descends into mental illness

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

.

Fitzgerald began the novel in 1925 after the publication of his third novel ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts First-person narrative, first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious mil ...

''. During the protracted writing process, the mental health of his wife rapidly deteriorated, and she required extended hospitalization due to her suicidal and homicidal tendencies. After her hospitalization in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, the author rented the ''La Paix'' estate in the suburb of Towson

Towson () is an unincorporated community and a census-designated place in Baltimore County, Maryland, United States. The population was 55,197 as of the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Baltimore County and the second-most populous unincorp ...

to be close to his wife, and he continued working on the manuscript.

While working on the book, Fitzgerald was beset with financial difficulties and drank heavily. He borrowed money from both his editor Max Perkins

William Maxwell Evarts "Max" Perkins (September 20, 1884 – June 17, 1947) was an American book editor, best remembered for discovering authors Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Thomas Wolfe.

Early life and e ...

and his agent Harold Ober as well as wrote short stories for commercial magazines. Fitzgerald completed the work in Fall 1933, and ''Scribner's Magazine

''Scribner's Magazine'' was an American periodical published by the publishing house of Charles Scribner's Sons from January 1887 to May 1939. ''Scribner's Magazine'' was the second magazine out of the Scribner's firm, after the publication of ' ...

'' serialized the novel in four installments between January and April 1934 before its publication on April 12, 1934. Although artist Edward Shenton

Edward Shenton (1895-1977) was an American illustrator, author, editor, poet, and teacher.

Biography

Edward Shenton was an illustrator, writer, editor, poet, and teacher. He was born in Pottstown, Pa. November 29, 1895 and grew up in West Phila ...

illustrated the serialization, he did not design the book's jacket. The jacket was by an unknown artist, and Fitzgerald disliked it.

The title is taken from the poem "Ode to a Nightingale

"Ode to a Nightingale" is a poem by John Keats written either in the garden of the Spaniards Inn, Hampstead, London or, according to Keats' friend Charles Armitage Brown, under a plum tree in the garden of Keats' house at Wentworth Place, also ...

" by John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculo ...

.

Two versions of the novel are in print. The first version, published in 1934, uses flashbacks; the second, revised version, prepared by Fitzgerald's friend and noted critic Malcolm Cowley

Malcolm Cowley (August 24, 1898 – March 27, 1989) was an American writer, editor, historian, poet, and literary critic. His best known works include his first book of poetry, ''Blue Juniata'' (1929), his lyrical memoir, ''Exile's Return ...

on the basis of notes for a revision left by Fitzgerald, is ordered chronologically and was first published posthumously in 1948. Critics have suggested that Cowley's revision was undertaken due to negative reviews of the temporal structure of the first version of the book.

Fitzgerald considered the novel to be his masterwork

A masterpiece, ''magnum opus'' (), or ''chef-d’œuvre'' (; ; ) in modern use is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, ...

. Although it received a tepid response upon release, it has grown in acclaim over the years and is now regarded as among Fitzgerald's best works. In 1998, the Modern Library

The Modern Library is an American book publishing imprint and formerly the parent company of Random House. Founded in 1917 by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright as an imprint of their publishing company Boni & Liveright, Modern Library became an ...

ranked the novel 28th on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.

Plot summary

South of France

Southern France, also known as the South of France or colloquially in French as , is a defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', A ...

and surround themselves with a coterie of American expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country. In common usage, the term often refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, or artists taking positions outside their home country, either ...

s. Rosemary Hoyt, a 17-year-old actress, and her mother are staying at a nearby resort. Rosemary becomes infatuated with Dick and becomes close to Nicole.

Rosemary senses something is wrong with the couple, and her suspicions are confirmed when another guest at a party, Violet McKisco, reports witnessing Nicole's nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

in a bathroom. Tommy Barban, another guest, comes to the defense of Nicole and insists that Violet is lying. Angered by this accusation, Violet's husband Albert duels Barban on the beach, but both men miss their shots. Following these events, Dick, Nicole, Rosemary, and others depart the French Riviera.

Soon after, Rosemary is now a constant companion of both Dick and Nicole in Paris. She attempts to seduce Dick in her hotel room, but he rebuffs her advances, although he admits that he loves her. Much later, a black man named Jules Peterson is found murdered in Rosemary's bed at the hotel, a potential scandal which could destroy Rosemary's career. Dick moves the blood-soaked body out of the room to cover up any implied sexual relationship

An intimate relationship is an interpersonal relationship that involves Physical intimacy, physical or emotional intimacy. Although an intimate relationship is commonly a sexual relationship, it may also be a non-sexual relationship involving ...

between Rosemary and Peterson.

A flashback occurs in the narrative. In Spring 1917, Dick Diver—a promising young doctor—visits psychopathologist

Psychopathology is the study of abnormal cognition, behaviour, and experiences which differs according to social norms and rests upon a number of constructs that are deemed to be the social norm at any particular era.

Biological psychopatholo ...

Franz Gregorovious in Zürich, Switzerland. While visiting Franz, he meets a patient named Nicole Warren, a wealthy young woman whose sexual abuse

Sexual abuse or sex abuse, also referred to as molestation, is abusive sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using force or by taking advantage of another. Molestation often refers to an instance of sexual assa ...

by her father has led to mental neuroses. Over a period of time they exchange letters. With the permission of Franz who believes that Dick's friendship benefits Nicole's well-being, they start seeing each other. As Nicole's treatment progresses, she becomes infatuated with Dick who, in turn, develops Florence Nightingale syndrome. He determines to marry Nicole in order to provide her with lasting emotional stability.

Dick is offered a partnership in a Swiss psychiatric clinic by Franz, and Nicole uses her finances to pay for the enterprise. After his father's death, Dick travels to America for the burial and then journeys to Rome in hopes of seeing Rosemary. They start a brief affair which ends abruptly and painfully. A heartbroken Dick is involved in an altercation with the Italian police and is physically beaten. Nicole's sister helps him to get out of jail. After this public humiliation, his incipient alcoholism increases. When his alcoholism threatens his medical practice, Dick's ownership share of the clinic is purchased by American investors following Franz's suggestion.

Dick and Nicole's marriage disintegrates as he pines for Rosemary who has become a successful Hollywood star. Nicole distances herself from Dick as his self-confidence and friendliness turn into sarcasm and rudeness towards everyone. His constant unhappiness over what he could have been fuels his alcoholism, and Dick becomes embarrassing in social and familial situations. A lonely Nicole enters into an affair with Tommy Barban. She later divorces Dick and marries her lover.

Major characters

* Richard "Dick" Divera promising young psychiatrist and Yale alumnus who marries his patient Nicole Diver and becomes an alcoholic. * Nicole Diver (née Warren)an affluent mental patient who was the victim ofincest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity (marriage or stepfamily), adoption ...

and who marries Dick Diver. Based on Zelda Fitzgerald

Zelda Fitzgerald (; July 24, 1900 – March 10, 1948) was an American novelist, painter, dancer, and socialite.

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, she was noted for her beauty and high spirits, and was dubbed by her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald a ...

.

* Rosemary Hoytan eighteen-year-old Hollywood actress who falls in love with Dick Diver. Based on teenage starlet Lois Moran

Lois Moran (born Lois Darlington Dowling; March 1, 1909 – July 13, 1990) was an American film and stage actress.

.

* Tommy Barbana Franco-American soldier-of-fortune with whom Nicole Diver has an affair. Based on French aviator Edouard Jozan, and on Italian-American pianist composer Mario Braggiotti

Mario Braggiotti (November 29, 1905 – May 18, 1996) was a United States pianist, composer and raconteur. His career was launched by George Gershwin, who became his friend and mentor.

Early history

Braggiotti was born in Florence, Italy; his fath ...

.: "Oddly enough, the character of Tommy, or rather some of the mannerisms of Tommy, were taken from Mario Braggiotti, the brother of Stiano."

* Franz Gregoroviousa Swiss psychopathologist

Psychopathology is the study of abnormal cognition, behaviour, and experiences which differs according to social norms and rests upon a number of constructs that are deemed to be the social norm at any particular era.

Biological psychopatholo ...

at Dohmler's clinic who introduces a young Dick Diver to Nicole Warren, his patient.

* Beth "Baby" Warrenan unmarried spinster who is Nicole's older sibling and who disapproves of her marriage to Dick Diver.

* Abe Northan alcoholic composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Defi ...

who is later murdered in a New York speakeasy

A speakeasy, also called a blind pig or blind tiger, is an illicit establishment that sells alcoholic beverages, or a retro style bar that replicates aspects of historical speakeasies.

Speakeasy bars came into prominence in the United States d ...

. Based on Ring Lardner

Ringgold Wilmer Lardner (March 6, 1885 – September 25, 1933) was an American sports columnist and short story writer best known for his satirical writings on sports, marriage, and the theatre. His contemporaries Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Wo ...

and Charles MacArthur

Charles Gordon MacArthur (November 5, 1895 – April 21, 1956) was an American playwright, screenwriter and 1935 winner of the Academy Award for Best Story.

Life and career

MacArthur was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the sixth of seven chil ...

.

* Mary Norththe spirited wife of Abe North who divorces him, remarries, and becomes the wealthy Countess of Minghetti.

* Albert McKiscoan American novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living writing novels and other fiction, while others aspire to ...

who wins a duel against Tommy Barban. Based on novelist Robert McAlmon

Robert Menzies McAlmon (also used Robert M. McAlmon, as his signature name, March 9, 1895 – February 2, 1956) was an American writer, poet, and publisher. In the 1920s, he founded in Paris the publishing house, Contact Editions, where he publ ...

.

* Violet McKiscothe gossipy spouse of Albert McKisco who discovers Nicole's insanity and attempts to malign her reputation.

* Jules Petersona black man from Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

who helps Abe North and is later found dead in Rosemary Hoyt's hotel suit.

Background and composition

Sojourn in Europe

While abroad in Europe, F. Scott Fitzgerald began writing his fourth novel almost three weeks after the publication of ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts First-person narrative, first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious mil ...

'' in April 1925. He planned to tell the story of Francis Melarkey, a young Hollywood technician visiting the French Riviera

The French Riviera (known in French as the ; oc, Còsta d'Azur ; literal translation " Azure Coast") is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France. There is no official boundary, but it is usually considered to extend fro ...

with his domineering mother. Francis falls in with a circle of charming American expatriates, emotionally disintegrates, and kills his mother. Fitzgerald's tentative titles for the novel were "World's Fair," "Our Type" and "The Boy Who Killed His Mother." The characters of the charming American expatriates were based on Fitzgerald's acquaintances Gerald and Sara Murphy

Gerald Clery Murphy and Sara Sherman Wiborg were wealthy, expatriate Americans who moved to the French Riviera in the early 20th century and who, with their generous hospitality and flair for parties, created a vibrant social circle, particularl ...

and were named Seth and Dinah Piper. Francis was intended to fall in love with Dinah, an event that would precipitate his disintegration.

Fitzgerald wrote five drafts of this earlier version of the novel in 1925 and 1926, but he was unable to finish it. Nearly all of what he wrote made it into the finished work in altered form. Francis's arrival on the Riviera with his mother, and his introduction to the world of the Pipers, was transposed into Rosemary Hoyt's arrival with her mother, and her introduction to the world of Dick and Nicole Diver. Characters created in this early version survived into the final novel, particularly Abe and Mary North (originally Grant) and the McKiscos.

Several incidents such as Rosemary's arrival and early scenes on the beach, her visit to the Riviera movie studio, and the dinner party at the Divers' villa all appeared in this original version, but with Francis in the role of the wide-eyed outsider that would later be filled by Rosemary. Also, the sequence in which a drunken Dick is beaten by police in Rome was written in this first version as well and was based on a real incident that happened to Fitzgerald in Rome in 1924.

Return to America

After a certain point, Fitzgerald became stymied with the novel. He, Zelda, and their daughter Scottie returned to the United States in December 1926 after several years in Europe. Film producer John W. Considine Jr. invited Fitzgerald toHollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

during its golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

to write a flapper

Flappers were a subculture of young Western women in the 1920s who wore short skirts (knee height was considered short during that period), bobbed their hair, listened to jazz, and flaunted their disdain for what was then considered acceptab ...

comedy for United Artists

United Artists Corporation (UA), currently doing business as United Artists Digital Studios, is an American digital production company. Founded in 1919 by D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, the studi ...

. He agreed and moved into a studio-owned bungalow with Zelda in January 1927. In Hollywood, the Fitzgeralds attended parties where they danced the black bottom and mingled with film stars.

While attending a lavish party at the Pickfair

Pickfair is a mansion and estate in the city of Beverly Hills, California with legendary history. The original Pickfair was an 18 acre (7.3 ha) estate designed by architect Horatio Cogswell for attorney Lee Allen Phillips of Berkeley Square a ...

estate, Fitzgerald met 17-year-old Lois Moran

Lois Moran (born Lois Darlington Dowling; March 1, 1909 – July 13, 1990) was an American film and stage actress.

, a starlet who had gained widespread fame for her role in '' Stella Dallas'' (1925). Desperate for intellectual conversation, Moran and Fitzgerald discussed literature and philosophy for hours while sitting on a staircase. Fitzgerald was 31 years old and past his prime, but the smitten Moran regarded him as a sophisticated, handsome, and gifted writer. Consequently, she pursued a relationship with him. The starlet became a muse for the author, and he wrote her into a short story called "Magnetism", in which a young Hollywood film starlet causes a married writer to waver in his sexual devotion to his wife. Fitzgerald later rewrote Rosemary Hoyt—one of the central characters in ''Tender is the Night''—to mirror Moran.

Jealous of Fitzgerald's relationship with Moran, an irate Zelda set fire to her expensive clothing in a bathtub as a self-destructive act. She disparaged the teenage Moran as "a breakfast food that many men identified with whatever they missed from life." Fitzgerald's relations with Moran further exacerbated the Fitzgeralds' marital difficulties and, after merely two months in Hollywood, the unhappy couple departed for Delaware in March 1927.

Fitzgerald supported himself and his family in the late 1920s with his lucrative short-story output for slick magazines such as the ''Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

'', but he was haunted by his inability to progress on the novel. Around 1929 he tried a new angle on the material, starting over with a shipboard story about a Hollywood director Lew Kelly and his wife Nicole as well as a young actress named Rosemary. But Fitzgerald only completed two chapters of this version.

Zelda's mental illness

By Spring 1929, the Fitzgeralds had returned to Europe when Zelda's mental health deteriorated. During an automobile trip to Paris along the mountainous roads of the Grande Corniche, Zelda seized the car's steering wheel and tried to kill herself, her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald, and their 9-year-old daughterScottie

The Scottish Terrier ( gd, Abhag Albannach; also known as the Aberdeen Terrier), popularly called the Scottie, is a breed of dog. Initially one of the highland breeds of terrier that were grouped under the name of ''Skye Terrier'', it is one o ...

by driving over a cliff. After this homicidal incident, Zelda sought psychiatric treatment, and doctors diagnosed her with schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations (typically hearing voices), delusions, and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social withdra ...

in June 1930. Zelda's biographer, Nancy Milford

Nancy Lee Milford (née Winston; March 26, 1938 – March 29, 2022) was an American biographer. She was noted for her biographies on Zelda Fitzgerald and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Early life and education

Nancy Lee Winston was born in Dearborn ...

, quotes Dr. Oscar Forel's contemporary psychiatric diagnosis:

Seeking a cure for her mental illness, the couple traveled to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

where Zelda underwent further treatment at a clinic. Zelda's ingravescent mental illness and the death of Fitzgerald's father in 1931 dispirited the author. Devastated by these events, an alcoholic Fitzgerald settled in suburban Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

where he rented the ''La Paix'' estate from architect Bayard Turnbull. He decided the novel's final plot would involve a young man of great potential who marries a mentally-ill woman and sinks into despair and alcoholism when their doomed marriage fails.

Final draft and publication

Fitzgerald wrote the final version of ''Tender Is the Night'' in 1932 and 1933. He salvaged almost everything he had written for the earlier Melarkey draft of the novel, as well as borrowed ideas and phrases from many short stories he had written in the years since completing ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts First-person narrative, first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious mil ...

''. Ultimately, he poured everything he had into ''Tender''—his feelings regarding his wasted talent and self-perceived professional failure; his animosity towards his parents;: "My father is a moron and my mother is a neurotic, half insane with pathological nervous worry," Fitzgerald wrote to Max Perkins

William Maxwell Evarts "Max" Perkins (September 20, 1884 – June 17, 1947) was an American book editor, best remembered for discovering authors Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and Thomas Wolfe.

Early life and e ...

. "Between them they haven't and never have had the brains of Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

." his marriage to Zelda and her ingravescent mental illness; his infatuation with actress Lois Moran, and Zelda's affair with the French aviator Edouard Jozan.

Fitzgerald completed the work in Fall 1933, and ''Scribner's Magazine'' serialized the novel in four installments between January and April 1934 before its publication on April 12, 1934. Although artist Edward Shenton

Edward Shenton (1895-1977) was an American illustrator, author, editor, poet, and teacher.

Biography

Edward Shenton was an illustrator, writer, editor, poet, and teacher. He was born in Pottstown, Pa. November 29, 1895 and grew up in West Phila ...

illustrated the serialization, he did not design the book's jacket. The jacket was by an unknown artist, and Fitzgerald disliked it. The title is taken from the poem "Ode to a Nightingale

"Ode to a Nightingale" is a poem by John Keats written either in the garden of the Spaniards Inn, Hampstead, London or, according to Keats' friend Charles Armitage Brown, under a plum tree in the garden of Keats' house at Wentworth Place, also ...

" by John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculo ...

.

Critical reception

Fitzgerald deemed the novel to be his masterwork and believed it would eclipse the acclaim of his previous works. It was instead met with lukewarm sales and mixed reviews. One book review in ''

Fitzgerald deemed the novel to be his masterwork and believed it would eclipse the acclaim of his previous works. It was instead met with lukewarm sales and mixed reviews. One book review in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' by critic J. Donald Adams was particularly harsh:

In contrast to the negative review in ''The New York Times'', critic Burke Van Allen hailed the novel as a masterpiece in a April 1934 review in ''The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

:''This article covers both the historical newspaper (1841–1955, 1960–1963), as well as an unrelated new Brooklyn Daily Eagle starting 1996 published currently''

The ''Brooklyn Eagle'' (originally joint name ''The Brooklyn Eagle'' and ''King ...

'':

Three months after its publication, ''Tender Is the Night'' had sold only 12,000 copies compared to ''This Side of Paradise'' which sold over 50,000 copies. Despite a number of positive reviews, a consensus emerged that the novel's Jazz Age setting and subject matter were both outdated and uninteresting to readers. The unexpected failure of the novel puzzled Fitzgerald for the remainder of his life.

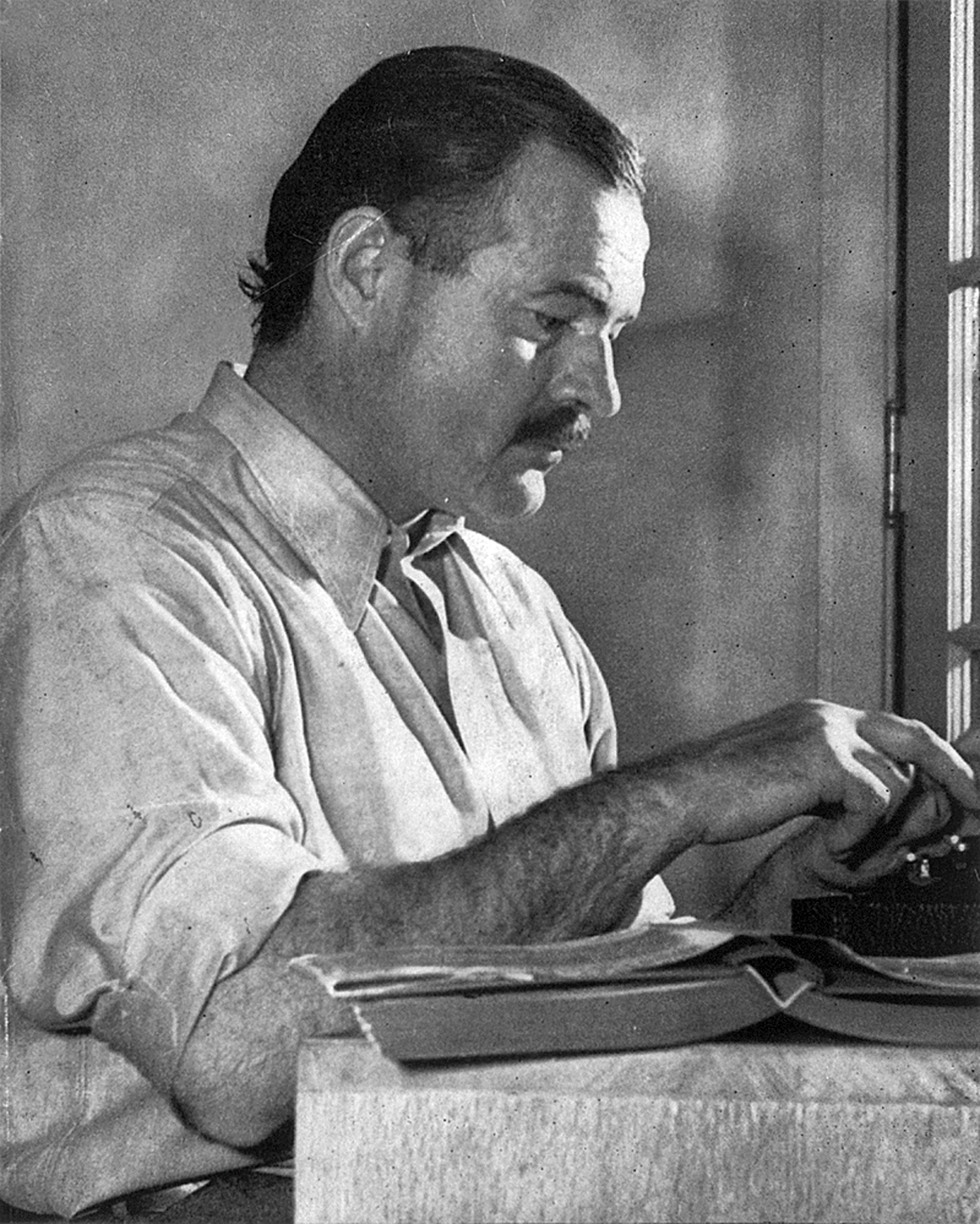

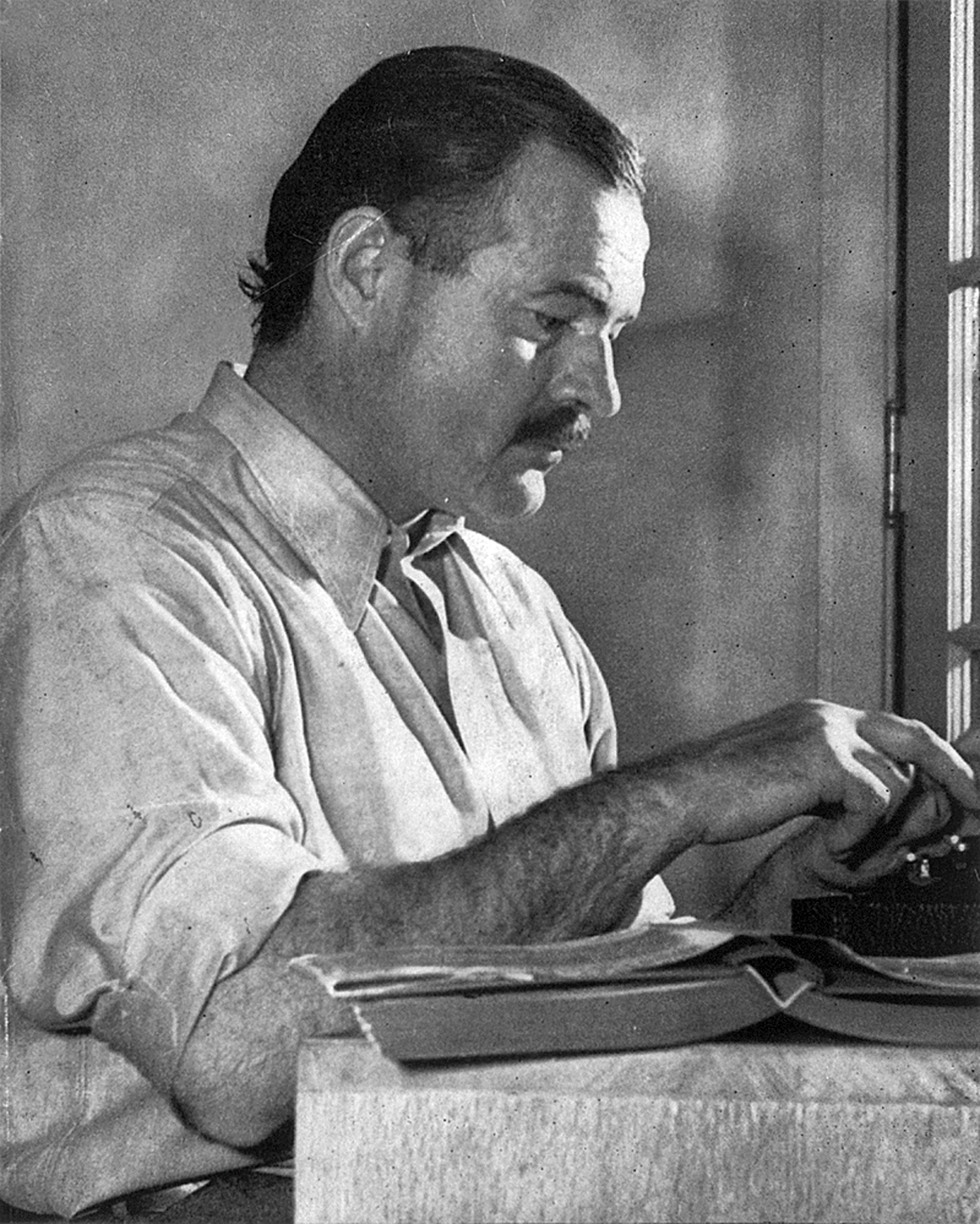

Various hypotheses have arisen as to why the novel did not receive a warmer reception upon release. Fitzgerald's friend, author Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

, opined that critics had initially only been interested in dissecting its weaknesses, rather than giving due credit to its merits. He argued that such overly harsh criticism stemmed from superficial readings of the material and Depression-era America's reaction to Fitzgerald's status as a symbol of Jazz Age excess. In his later years, Hemingway re-read the work and remarked that, in retrospect, "''Tender Is the Night'' gets better and better".

Posthumous reevaluation

Following Fitzgerald's death in 1940, ''Tender Is the Night''s critical reputation has steadily grown. Later critics have described it as "an exquisitely crafted piece of fiction" and "one of the greatest American novels". It is now widely regarded as among Fitzgerald's most accomplished works, with some agreeing with the author's assessment that it surpasses ''The Great Gatsby''. Several critics have interpreted the novel to be afeminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

work and posited that the patriarchal attitudes of the reactionary 1930s underlay the critical dismissal. They have noted the parallels between Dick Diver and Jay Gatsby

Jay Gatsby (originally named James Gatz) is the titular fictional character of F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel ''The Great Gatsby''. The character is an enigmatic ''nouveau riche'' millionaire who lives in a luxurious mansion on Long Island whe ...

, with many regarding the novel and particularly Diver's character, as Fitzgerald's most emotionally and psychologically complex work.

Christian Messenger argues that Fitzgerald's book hinges on the sustaining sentimental fragments: "On an aesthetic level, Fitzgerald's working through of sentiment's broken premises and rhetoric in ''Tender'' heralds a triumph of modernism in his attempt to sustain his sentimental fragments and allegiances in new forms." He calls it "F. Scott Fitzgerald's richest novel, replete with vivid characters, gorgeous prose, and shocking scenes," and calls attention to Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek (, ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual. He is international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, visiting professor at New Y ...

's use of the book to illustrate the nonlinear nature of experience.

Legacy and influence

In 1998, theModern Library

The Modern Library is an American book publishing imprint and formerly the parent company of Random House. Founded in 1917 by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright as an imprint of their publishing company Boni & Liveright, Modern Library became an ...

included the novel at #28 on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. ''Radcliffe'' later included it at #62 in its rival list. NPR

National Public Radio (NPR, stylized in all lowercase) is an American privately and state funded nonprofit media organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It differs from other ...

included it at #69 on its 2009 list titled ''100 Years, 100 Novels''. In 2012 it was listed as one of the ''1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die

''1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die'' is a literary reference book compiled by over one hundred literary critics worldwide and edited by Peter Boxall, Professor of English at Sussex University, with an introduction by Peter Ackroyd. Each tit ...

''.

Adaptations

In 1962, afilm adaptation

A film adaptation is the transfer of a work or story, in whole or in part, to a feature film. Although often considered a type of derivative work, film adaptation has been conceptualized recently by academic scholars such as Robert Stam as a dial ...

was released with Jason Robards

Jason Nelson Robards Jr. (July 26, 1922 – December 26, 2000) was an American actor. Known as an interpreter of the works of playwright Eugene O'Neill, Robards received two Academy Awards, a Tony Award, a Primetime Emmy Award, and the Cannes ...

as Dick Diver and Jennifer Jones

Jennifer Jones (born Phylis Lee Isley; March 2, 1919 – December 17, 2009), also known as Jennifer Jones Simon, was an American actress and mental health advocate. Over the course of her career that spanned over five decades, she was nominated ...

as Nicole Diver. The song "Tender Is the Night" from the movie soundtrack was nominated for the 1962 Academy Awards for Best Song.

Two decades later, in 1985, a television mini-series of the book was co-produced by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...20th Century Fox Television

20th Television (formerly 20th Century Fox Television, 20th Century-Fox Television, and TCF Television Productions, Inc.) is an American television production company that is a division of Disney Television Studios, part of The Walt Disney Compa ...

, and Showtime Entertainment. The mini-series featured Peter Strauss

Peter Lawrence Strauss (born February 20, 1947) is an American television and film actor, known for his roles in several television miniseries in the 1970s and 1980s. He is five-time Golden Globe Awards nominee.

Early life

Strauss was born in C ...

as Dick Diver, Mary Steenburgen

Mary Nell Steenburgen (; born February 8, 1953) is an American actress, comedian, singer, and songwriter. After studying at New York's Neighborhood Playhouse in the 1970s, she made her professional acting debut in 1978 Western comedy film ''Goin' ...

as Nicole Diver, and Sean Young

Mary Sean Young (born November 20, 1959) is an American actress. She is particularly known for working in sci-fi films, although she has performed roles in a variety of genres.

Young's early roles include the independent romance ''Jane Auste ...

as Rosemary Hoyt.

In 1995, a stage adaptation by Simon Levy, with permission of the Fitzgerald Estate, was produced at The Fountain Theatre

The Fountain Theatre is a theatre in Los Angeles. Along with its programming of live theatre, it's also the foremost producer of flamenco on the West Coast of the United States, West Coast.

History

The Fountain Theatre was founded in Los Ange ...

, Los Angeles. It won the PEN Literary Award in Drama and several other awards.

Boris Eifman

Boris Eifman (Борис Яковлевич Эйфман) (born 22 July 1946, in Rubtsovsk) is a Russian choreographer and artistic director. He has done more than fifty ballet productions.

Eifman was born in Siberia, where his engineer father ha ...

's 2015 ballet ''Up and Down'' is based loosely on the novel.

References

Notes

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Tender Is the Night 1934 American novels Fiction set in 1913 Fiction set in 1925 Adultery in novels American autobiographical novels American novels adapted into films Feminist novels Modernist novels American novels adapted into television shows Novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald Novels first published in serial form Novels set in France Novels set in the Roaring Twenties Psychological novels Roman à clef novels Works originally published in Scribner's Magazine Nonlinear narrative novels Incest in fiction