Tōru Takemitsu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a Japanese

From the early 1960s, Takemitsu began to make use of traditional Japanese instruments in his music, and even took up playing the ''

From the early 1960s, Takemitsu began to make use of traditional Japanese instruments in his music, and even took up playing the ''

"Takemitsu, Tōru"

''The Oxford Companion to Music'', ed. Alison Latham, (Oxford University Press, 2011), Oxford Reference Online, (subscription access). including the Prix Italia for his orchestral work ''Tableau noir'' in 1958, the Otaka Prize in 1976 and 1981, the Los Angeles Film Critics Award in 1987 (for the film score ''Ran'') and the University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition in 1994 (for ''Fantasma/Cantos''). In Japan, he received the Japan Academy Prize (film), Film Awards of the Japanese Academy for outstanding achievement in music, for soundtracks to the following films: * 1979 * 1985 Fire Festival (film) * 1986 * 1990 * 1996 He was also invited to attend numerous international festivals throughout his career, and presented lectures and talks at academic institutions across the world. He was made an honorary member of the Akademie der Künste of the DDR in 1979, and the American Institute of Arts and Letters in 1985. He was admitted to the French ''Ordre des Arts et des Lettres'' in 1985, and the ''Académie des Beaux-Arts'' in 1986. He was the recipient of the 22nd Suntory Music Award (1990). Posthumously, Takemitsu received a

Honorary Doctorate from Columbia University

early in 1996 and was awarded the fourth Glenn Gould Prize in fall 1996. The Toru Takemitsu Composition Award, intended to "encourage a younger generation of composers who will shape the coming age through their new musical works", is named after him.

Toru Takemitsu: Complete Works

*

Slate article focusing on his film music

Interview with Toru Takemitsu

* * *

on WNIB (defunct), WNIB Classical 97, Chicago, 6 March 1990 {{DEFAULTSORT:Takemitsu, Toru 1930 births 1996 deaths 20th-century classical composers 20th-century classical pianists 20th-century Japanese composers 20th-century Japanese guitarists 20th-century Japanese male musicians 20th-century musicologists Composers for the classical guitar Composers for piano Deaths from bladder cancer Deaths from cancer in Japan Deaths from pneumonia in Japan Deutsche Grammophon artists Georges Delerue Award winners Glenn Gould Prize winners International Rostrum of Composers prize-winners Japanese classical composers Japanese classical guitarists Japanese classical pianists Japanese electronic musicians Japanese film score composers Japanese male classical composers Japanese male classical pianists Japanese male film score composers Japanese television composers Male television composers Music theorists Musicians from Tokyo

composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Defi ...

and writer on aesthetics

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed thr ...

and music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (ke ...

. Largely self-taught, Takemitsu was admired for the subtle manipulation of instrumental and orchestral timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or musical tone, tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voice ...

. He is known for combining elements of oriental and occidental philosophy and for fusing sound with silence and tradition with innovation.

He composed several hundred independent works of music, scored more than ninety films and published twenty books. He was also a founding member of the '' Jikken Kōbō'' (Experimental Workshop) in Japan, a group of avant-garde artists who distanced themselves from academia

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

and whose collaborative work is often regarded among the most influential of the 20th century.

His 1957 ''Requiem'' for string orchestra attracted international attention, led to several commissions from across the world and established his reputation as the leading 20th-century Japanese composer. He was the recipient of numerous awards and honours and the Toru Takemitsu Composition Award

The is a music competition for young composers organized in Tokyo, Japan.

History

The Toru Takemitsu Composition Award (annual competition of orchestral composition), which is an international composition award following Toru Takemitsu's princip ...

is named after him.

Biography

Youth

Takemitsu was born inTokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

on 8 October 1930; a month later his family moved to Dalian

Dalian () is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China. Located on the ...

in the Chinese province of Liaoning

Liaoning () is a coastal province in Northeast China that is the smallest, southernmost, and most populous province in the region. With its capital at Shenyang, it is located on the northern shore of the Yellow Sea, and is the northernmost ...

. In 1938 he returned to Japan to attend elementary school, but his education was cut short by military conscription in 1944. Takemitsu described his experience of military service at such a young age, under the Japanese Nationalist government, as "... extremely bitter".Takemitsu, Tōru, "Contemporary Music in Japan", ''Perspectives of New Music

''Perspectives of New Music'' (PNM) is a peer-reviewed academic journal specializing in music theory and analysis. It was established in 1962 by Arthur Berger and Benjamin Boretz (who were its initial editors-in-chief).

''Perspectives'' was first ...

'', vol. 27, no. 2, (Summer 1989), 3. Takemitsu first became conscious of Western classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

during his term of military service, in the form of a popular French Song (" Parlez-moi d'amour") which he listened to with colleagues in secret, played on a gramophone with a makeshift needle fashioned from bamboo.

During the post-war U.S. occupation of Japan, Takemitsu worked for the U.S. Armed Forces, but was ill for a long period. Hospitalised and bed-ridden, he took the opportunity to listen to as much Western music as he could on the U.S. Armed Forces network. While deeply affected by these experiences of Western music, he simultaneously felt a need to distance himself from the traditional music of his native Japan. He explained much later, in a lecture at the New York International Festival of the Arts, that for him Japanese traditional music "always recalled the bitter memories of war".

Despite his lack of musical training, and taking inspiration from what little Western music he had heard, Takemitsu began to compose in earnest at the age of 16: "... I began riting

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred, or digitally represented symbols.

Writing systems do not themselves constitute h ...

music attracted to music itself as one human being. Being in music I found my raison d'être as a man. After the war, music was the ''only'' thing. Choosing to be in music clarified my identity." Though he studied briefly with Yasuji Kiyose beginning in 1948, Takemitsu remained largely self-taught throughout his musical career.

Early development and Jikken Kōbō

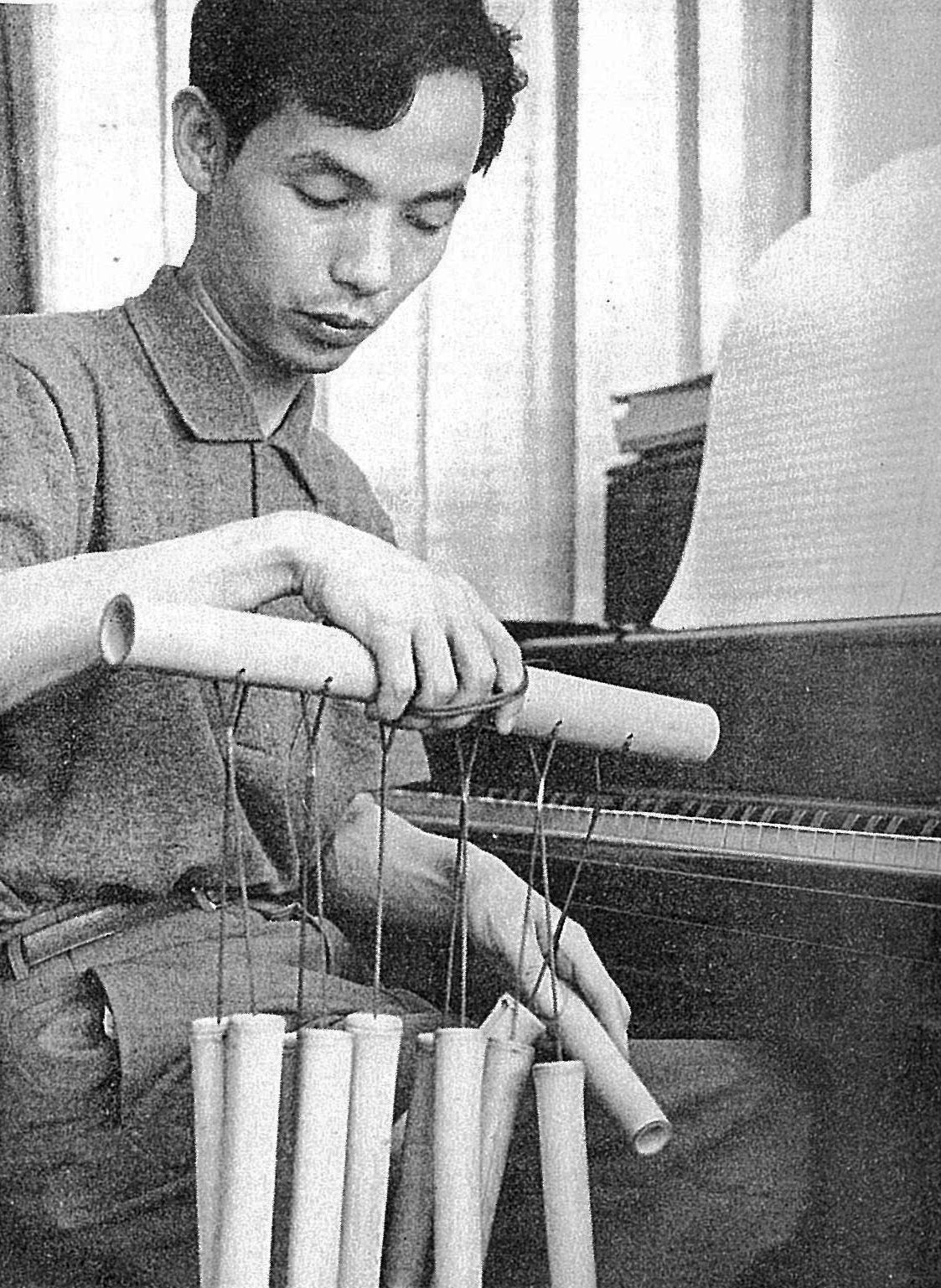

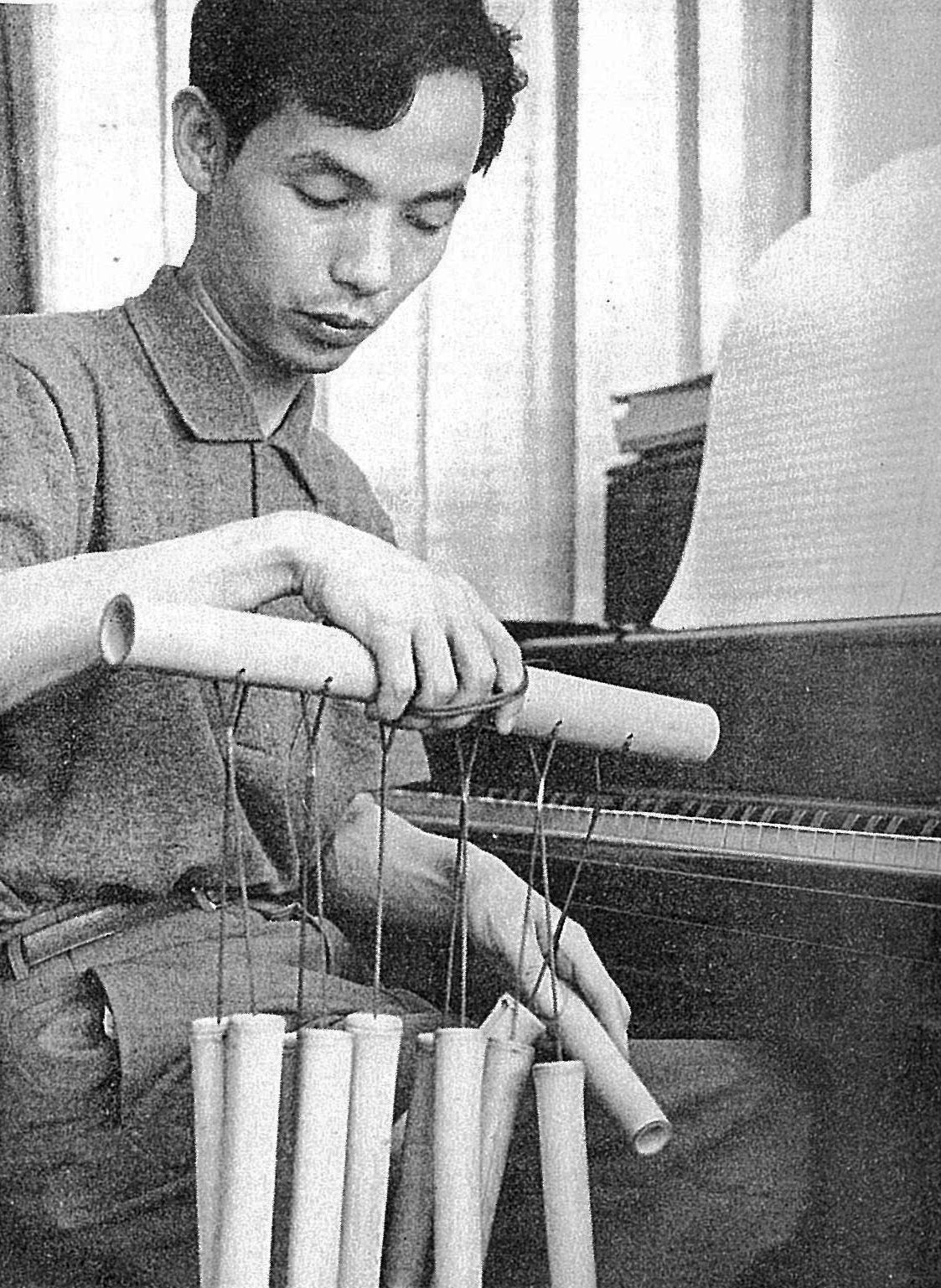

In 1948, Takemitsu conceived the idea ofelectronic music

Electronic music is a genre of music that employs electronic musical instruments, digital instruments, or circuitry-based music technology in its creation. It includes both music made using electronic and electromechanical means ( electroac ...

technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, science, ...

, or in his own words, to "bring noise into tempered musical tones inside a busy small tube." During the 1950s, Takemitsu had learned that in 1948 "a French ngineerPierre Schaeffer

Pierre Henri Marie Schaeffer (English pronunciation: , ; 14 August 1910 – 19 August 1995) was a French composer, writer, broadcaster, engineer, musicologist, acoustician and founder of Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC). His innov ...

invented the method(s) of ''musique concrète

Musique concrète (; ): " problem for any translator of an academic work in French is that the language is relatively abstract and theoretical compared to English; one might even say that the mode of thinking itself tends to be more schematic, ...

'' based on the same idea as mine. I was pleased with this coincidence."

In 1951, Takemitsu was a founding member of the anti-academic : an artistic group established for multidisciplinary collaboration on mixed-media projects, who sought to avoid Japanese artistic tradition.Schlüren, Christoph, "Review: Peter Burt, 'The Music of Toru Takemitsu' (Cambridge 2001)", ''Tempo

In musical terminology, tempo (Italian, 'time'; plural ''tempos'', or ''tempi'' from the Italian plural) is the speed or pace of a given piece. In classical music, tempo is typically indicated with an instruction at the start of a piece (often ...

'' no. 57, (Cambridge, 2003), 65. The performances and works undertaken by the group introduced several contemporary Western composers to Japanese audiences. During this period he wrote ''Saegirarenai Kyūsoku I'' ("Uninterrupted Rest I", 1952: a piano work, without a regular rhythmic pulse or barlines); and by 1955 Takemitsu had begun to use electronic tape-recording techniques in such works as ''Relief Statique'' (1955) and ''Vocalism A·I'' (1956). Takemitsu also studied in the early 1950s with the composer Fumio Hayasaka

Fumio Hayasaka (早坂 文雄 ''Hayasaka Fumio''; August 19, 1914 – October 15, 1955) was a Japanese composer of classical music and film scores.

Early life

Hayasaka was born in the city of Sendai on the main Japanese island of Honshū. In ...

, perhaps best known for the scores he wrote for films by Kenji Mizoguchi

was a Japanese film director and screenwriter, who directed about one hundred films during his career between 1923 and 1956. His most acclaimed works include ''The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums'' (1939), ''The Life of Oharu'' (1952), ''Uget ...

and Akira Kurosawa

was a Japanese filmmaker and painter who directed thirty films in a career spanning over five decades. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers in the history of cinema. Kurosawa displayed a bold, dyna ...

, the latter of whom Takemitsu would collaborate with decades later.

In the late 1950s chance brought Takemitsu international attention: his ''Requiem'' for string orchestra (1957), written as an homage to Hayasaka, was heard by Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

in 1958 during his visit to Japan. (The NHK

, also known as NHK, is a Japanese public broadcaster. NHK, which has always been known by this romanized initialism in Japanese, is a statutory corporation funded by viewers' payments of a television license fee.

NHK operates two terrestr ...

had organised opportunities for Stravinsky to listen to some of the latest Japanese music; when Takemitsu's work was put on by mistake, Stravinsky insisted on hearing it to the end.) At a press conference later, Stravinsky expressed his admiration for the work, praising its "sincerity" and "passionate" writing. Stravinsky subsequently invited Takemitsu to lunch; and for Takemitsu this was an "unforgettable" experience.Takemitsu, Tōru ith Tania Cronin and Hilary Tann

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

"Afterword", ''Perspectives of New Music

''Perspectives of New Music'' (PNM) is a peer-reviewed academic journal specializing in music theory and analysis. It was established in 1962 by Arthur Berger and Benjamin Boretz (who were its initial editors-in-chief).

''Perspectives'' was first ...

'', vol. 27, no. 2 (Summer 1989), 205–207. After Stravinsky returned to the U.S., Takemitsu soon received a commission for a new work from the Koussevitsky Foundation which, he assumed, had come as a suggestion from Stravinsky to Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

. For this he composed ''Dorian Horizon'', (1966), which was premièred by the San Francisco Symphony

The San Francisco Symphony (SFS), founded in 1911, is an American orchestra based in San Francisco, California. Since 1980 the orchestra has been resident at the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall in the city's Hayes Valley neighborhood. The San Fr ...

, conducted by Copland.

Influence of Cage; interest in traditional Japanese music

During his time with Jikken Kōbō, Takemitsu came into contact with the experimental work ofJohn Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

; but when the composer Toshi Ichiyanagi

was a Japanese avant-garde composer and pianist. One of the leading composers in Japan during the postwar era, Ichiyanagi worked in a range of genres, composing Western-style operas and orchestral and chamber works, as well as compositions using ...

returned from his studies in America in 1961, he gave the first Japanese performance of Cage's ''Concert for Piano and Orchestra''. This left a "deep impression" on Takemitsu: he recalled the impact of hearing the work when writing an obituary for Cage, 31 years later. This encouraged Takemitsu in his use of indeterminate procedures and graphic-score notation, for example in the graphic scores of ''Ring'' (1961), '' Corona for pianist(s)'' and ''Corona II for string(s)'' (both 1962). In these works each performer is presented with cards printed with coloured circular patterns which are freely arranged by the performer to create "the score".

Although the immediate influence of Cage's procedures did not last in Takemitsu's music—''Coral Island'', for example for soprano and orchestra (1962) shows significant departures from indeterminate procedures partly as a result of Takemitsu's renewed interest in the music of Anton Webern

Anton Friedrich Wilhelm von Webern (3 December 188315 September 1945), better known as Anton Webern (), was an Austrian composer and conductor whose music was among the most radical of its milieu in its sheer concision, even aphorism, and stea ...

—certain similarities between Cage's philosophies and Takemitsu's thought remained. For example, Cage's emphasis on timbres within individual sound-events, and his notion of silence "as plenum rather than vacuum", can be aligned with Takemitsu's interest in ''ma''. Furthermore, Cage's interest in Zen practice (through his contact with Zen scholar Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki

, self-rendered in 1894 as "Daisetz", was a Japanese-American Buddhist monk, essayist, philosopher, religious scholar, translator, and writer. He was a scholar and author of books and essays on Buddhism, Zen and Shin that were instrumental in s ...

) seems to have resulted in a renewed interest in the East in general, and ultimately alerted Takemitsu to the potential for incorporating elements drawn from Japanese traditional music into his composition:

I must express my deep and sincere gratitude to John Cage. The reason for this is that in my own life, in my own development, for a long period I struggled to avoid being "Japanese", to avoid "Japanese" qualities. It was largely through my contact with John Cage that I came to recognize the value of my own tradition.For Takemitsu, as he explained later in a lecture in 1988, one performance of Japanese traditional music stood out:

One day I chanced to see a performance of theThereafter, he resolved to study all types of traditional Japanese music, paying special attention to the differences between the two very different musical traditions, in a diligent attempt to "bring forth the sensibilities of Japanese music that had always been within im. This was no easy task, since in the years following the war traditional music was largely overlooked and ignored: only one or two "masters" continued to keep their art alive, often meeting with public indifference. In conservatoria across the country, even students of traditional instruments were always required to learn the piano.Bunraku (also known as ) is a form of traditional Japanese puppet theatre, founded in Osaka in the beginning of the 17th century, which is still performed in the modern day. Three kinds of performers take part in a performance: the or ( puppeteers ...puppet theater and was very surprised by it. It was in the tone quality, the timbre, of the futazaoshamisen The , also known as the or (all meaning "three strings"), is a three-stringed traditional Japanese musical instrument derived from the Chinese instrument . It is played with a plectrum called a bachi. The Japanese pronunciation is usual ..., the wide-necked shamisen used in Bunraku, that I first recognized the splendor of traditional Japanese music. I was very moved by it and I wondered why my attention had never been captured before by this Japanese music.

From the early 1960s, Takemitsu began to make use of traditional Japanese instruments in his music, and even took up playing the ''

From the early 1960s, Takemitsu began to make use of traditional Japanese instruments in his music, and even took up playing the ''biwa

The is a Japanese short-necked wooden lute traditionally used in narrative storytelling. The is a plucked string instrument that first gained popularity in China before spreading throughout East Asia, eventually reaching Japan sometime duri ...

''—an instrument he used in his score for the film ''Seppuku

, sometimes referred to as hara-kiri (, , a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honour but was also practised by other Japanese people ...

'' (1962). In 1967, Takemitsu received a commission from the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

, to commemorate the orchestra's 125th anniversary, for which he wrote ''November Steps

is a musical composition by the Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu, for the traditional Japanese musical instruments, '' shakuhachi'' and '' biwa'', and western orchestra. The work was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic on the occasion of ...

'' for ''biwa'', ''shakuhachi

A is a Japanese and ancient Chinese longitudinal, end-blown flute that is made of bamboo.

The bamboo end-blown flute now known as the was developed in Japan in the 16th century and is called the .

'', and orchestra. Initially, Takemitsu had great difficulty in uniting these instruments from such different musical cultures in one work. ''Eclipse

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three ce ...

'' for ''biwa'' and ''shakuhachi'' (1966) illustrates Takemitsu's attempts to find a viable notational system for these instruments, which in normal circumstances neither sound together nor are used in works notated in any system of Western staff notation.Burt, 112.

The first performance of ''November Steps'' was given in 1967, under Seiji Ozawa

Seiji (written: , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , or in hiragana) is a masculine Japanese given name. Notable people with the name include:

*, Japanese ski jumper

*, Japanese racing driver

*, Japanese politician

*, Japanese film directo ...

. Despite the trials of writing such an ambitious work, Takemitsu maintained "that making the attempt was very worthwhile because what resulted somehow liberated music from a certain stagnation and brought to music something distinctly new and different". The work was distributed widely in the West when it was coupled as the fourth side of an LP release of Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithology, ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th-century classical music, 20th century. His m ...

's '' Turangalîla Symphony''.

In 1972, Takemitsu, accompanied by Iannis Xenakis

Giannis Klearchou Xenakis (also spelled for professional purposes as Yannis or Iannis Xenakis; el, Γιάννης "Ιωάννης" Κλέαρχου Ξενάκης, ; 29 May 1922 – 4 February 2001) was a Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde ...

, Betsy Jolas

Elizabeth Jolas (born 5 August 1926) is a Franco-American composer.

Biography

Jolas was born in Paris in 1926. Her mother, the American translator Maria McDonald, was a singer. Her father, the poet and journalist Eugene Jolas, founded and edited ...

, and others, heard Bali

Bali () is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller neighbouring islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and Nu ...

nese gamelan

Gamelan () ( jv, ꦒꦩꦼꦭꦤ꧀, su, ᮌᮙᮨᮜᮔ᮪, ban, ᬕᬫᭂᬮᬦ᭄) is the traditional ensemble music of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese peoples of Indonesia, made up predominantly of percussive instruments. T ...

music in Bali. The experience influenced the composer on a largely philosophical and theological level. For those accompanying Takemitsu on the expedition (most of whom were French musicians), who "... could not keep their composure as I did before this music: it was too foreign for them to be able to assess the resulting discrepancies with their logic", the experience was without precedent. For Takemitsu, however, by now quite familiar with his own native musical tradition, there was a relationship between "the sounds of the gamelan, the tone of the ''kapachi'', the unique scales and rhythms by which they are formed, and Japanese traditional music which had shaped such a large part of my sensitivity". In his solo piano work ''For Away'' (written for Roger Woodward

Roger Woodward (born 20 December 1942) is an Australian classical pianist, composer, conductor and teacher.

Life and career Early life

The youngest of four children, Roger Woodward was born in Sydney where he received first piano lessons ...

in 1973), a single, complex line is distributed between the pianist's hands, which reflects the interlocking patterns between the metallophone

A metallophone is any musical instrument in which the sound-producing body is a piece of metal (other than a metal string), consisting of tuned metal bars, tubes, rods, bowls, or plates. Most frequently the metal body is struck to produce sound, ...

s of a gamelan orchestra.

A year later, Takemitsu returned to the instrumental combination of ''shakuhachi'', ''biwa'', and orchestra, in the less well known work ''Autumn'' (1973). The significance of this work is revealed in its far greater integration of the traditional Japanese instruments into the orchestral discourse; whereas in ''November Steps'', the two contrasting instrumental ensembles perform largely in alternation, with only a few moments of contact. Takemitsu expressed this change in attitude:

But now my attitude is getting to be a little different, I think. Now my concern is mostly to find out what there is in common ... ''Autumn'' was written after ''November Steps''. I really wanted to do something which I hadn't done in ''November Steps'', not to blend the instruments, but to integrate them.

International status and the gradual shift in style

By 1970, Takemitsu's reputation as a leading member of avant-garde community was well established, and during his involvement withExpo '70

The or Expo 70 was a world's fair held in Suita, Osaka Prefecture, Japan between March 15 and September 13, 1970. Its theme was "Progress and Harmony for Mankind." In Japanese, Expo '70 is often referred to as . It was the first world's fair ...

in Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of 2. ...

, he was at last able to meet more of his Western colleagues, including Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groun ...

. Also, during a contemporary music festival in April 1970, produced by the Japanese composer himself ("Iron and Steel Pavilion"), Takemitsu met among the participants Lukas Foss

Lukas Foss (August 15, 1922 – February 1, 2009) was a German-American composer, pianist, and conductor.

Career

Born Lukas Fuchs in Berlin, Germany in 1922, Foss was soon recognized as a child prodigy. He began piano and theory lessons with J ...

, Peter Sculthorpe

Peter Joshua Sculthorpe (29 April 1929 – 8 August 2014) was an Australian composer. Much of his music resulted from an interest in the music of countries neighboring Australia as well as from the impulse to bring together aspects of Aborigin ...

, and Vinko Globokar

Vinko Globokar (born 7 July 1934) is a French-Slovenian avant-garde composer and trombonist.

Globokar's music uses unconventional and extended techniques, places great emphasis on spontaneity and creativity, and often relies on improvisation. Hi ...

. Later that year, as part of a commission from Paul Sacher

Paul Sacher (28 April 190626 May 1999) was a Swiss conductor, patron and billionaire businessperson. At the time of his death Sacher was majority shareholder of pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-La Roche and was considered the third richest person i ...

and the Zurich Collegium Musicum

The Collegium Musicum was one of several types of musical societies that arose in German and German-Swiss cities and towns during the Reformation and thrived into the mid-18th century.

Generally, while societies such as the (chorale) cultivated ...

, Takemitsu incorporated into his ''Eucalypts I'' parts for international performers: flautist Aurèle Nicolet

Aurèle Nicolet (22 January 1926 – 29 January 2016) was a Swiss flautist. He was considered one of the world's best flute players of the late twentieth century.

He performed in various international concerts. A number of composers wrote music ...

, oboist Heinz Holliger

Heinz Robert Holliger (born 21 May 1939) is a Swiss virtuoso oboist, composer and conductor. Celebrated for his versatility and technique, Holliger is among the most prominent oboists of his generation. His repertoire includes Baroque and Classic ...

, and harpist Ursula Holliger.

Critical examination of the complex instrumental works written during this period for the new generation of "contemporary soloists" reveals the level of his high-profile engagement with the Western avant-garde, in works such as ''Voice

The human voice consists of sound made by a human being using the vocal tract, including talking, singing, laughing, crying, screaming, shouting, humming or yelling. The human voice frequency is specifically a part of human sound production in ...

'' for solo flute (1971), ''Waves'' for clarinet, horn, two trombones and bass drum (1976), ''Quatrain'' for clarinet, violin, cello, piano and orchestra (1977). Experiments and works that incorporated traditional Japanese musical ideas and language continued to appear in his output, and an increased interest in the traditional Japanese garden began to reflect itself in works such as ' for ''gagaku'' orchestra (1973), and ''A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden'' for orchestra (1977).

Throughout this apogee of avant-garde work, Takemitsu's musical style seems to have undergone a series of stylistic changes. Comparison of ''Green'' (for orchestra, 1967) and ''A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden'' (1977) quickly reveals the seeds of this change. The latter was composed according to a pre-compositional scheme, in which pentatonic modes were superimposed over one central pentatonic scale (the so-called "black-key pentatonic") around a central sustained central pitch (F-sharp), and an approach that is highly indicative of the sort of "pantonal" and modal pitch material seen gradually emerging in his works throughout the 1970s. The former, ''Green'' (or ''November Steps II'') written 10 years earlier, is heavily influenced by Debussy, and is, in spite of its very dissonant language (including momentary quarter-tone clusters), largely constructed through a complex web of modal forms. These modal forms are largely audible, particularly in the momentary repose toward the end of the work. Thus in these works, it is possible to see both a continuity of approach, and the emergence of a simpler harmonic language that was to characterise the work of his later period.

His friend and colleague Jō Kondō said, "If his later works sound different from earlier pieces, it is due to his gradual refining of his basic style rather than any real alteration of it."Kondō, Jō "Introduction: Tōru Takemitsu as I remember him", ''Contemporary Music Review'', Vol. 21, Iss. 4, (December 2002), 1–3.

Later works: the sea of tonality

In a Tokyo lecture given in 1984, Takemitsu identified a melodicmotive

Motive(s) or The Motive(s) may refer to:

* Motive (law)

Film and television

* ''Motives'' (film), a 2004 thriller

* ''The Motive'' (film), 2017

* ''Motive'' (TV series), a 2013 Canadian TV series

* ''The Motive'' (TV series), a 2020 Israeli T ...

in his ''Far Calls. Coming Far!'' (for violin and orchestra, 1980) that would recur throughout his later works:

I wanted to plan a tonal "sea". Here the "sea" is E-flat 'Es'' in German nomenclatureE-A, a three-note ascending motive consisting of a half step and perfect fourth. .. In ''Far Calls''this is extended upward from A with two major thirds and one minor third ... Using these patterns I set the "sea of tonality" from which many pantonal chords flow.Takemitsu's words here highlight his changing stylistic trends from the late 1970s into the 1980s, which have been described as "an increased use of diatonic material .. withreferences to tertian harmony and jazz voicing", which do not, however, project a sense of "large-scale tonality". Many of the works from this period have titles that include a reference to water: ''Toward the Sea'' (1981), ''Rain Tree'' and ''Rain Coming'' (1982), ''riverrun'' and ''I Hear the Water Dreaming'' (1987). Takemitsu wrote in his notes for the score of ''Rain Coming'' that "... the complete collection sentitled "Waterscape" ... it was the composer's intention to create a series of works, which like their subject, pass through various metamorphoses, culminating in a sea of tonality." Throughout these works, the S-E-A motive (discussed further below) features prominently, and points to an increased emphasis on the melodic element in Takemitsu's music that began during this later period. His 1981 work for orchestra named ''Dreamtime'' was inspired by a visit to

Groote Eylandt

Groote Eylandt ( Anindilyakwa: ''Ayangkidarrba'' meaning "island" ) is the largest island in the Gulf of Carpentaria and the fourth largest island in Australia. It was named by the explorer Abel Tasman in 1644 and is Dutch for "Large Island" in ...

, off the coast of the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory ...

of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, to witness a large gathering of Australian indigenous

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples o ...

dancers, singers and story tellers. He was there at the invitation of the choreographer Jiří Kylián

Jiří Kylián (born 21 March 1947) is a Czech former dancer and contemporary dance choreographer.

Life

Jiří Kylián was born in 1947 in Prague, Czechoslovakia, to his father Václav who was a banker and to his mother Markéta, who was as a ...

.

Pedal notes

In music, a pedal point (also pedal note, organ point, pedal tone, or pedal) is a sustained tone, typically in the bass, during which at least one foreign (i.e. dissonant) harmony is sounded in the other parts. A pedal point sometimes function ...

played an increasingly prominent role in Takemitsu's music during this period, as in ''A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden''. In ''Dream/Window'', (orchestra, 1985) a pedal D serves as anchor point, holding together statements of a striking four-note motivic gesture which recurs in various instrumental and rhythmic guises throughout. Very occasionally, fully fledged references to diatonic tonality can be found, often in harmonic allusions to early- and pre-20th-century composers—for example, ''Folios'' for guitar (1974), which quotes

Quote is a hypernym of quotation, as the repetition or copy of a prior statement or thought. Quotation marks are punctuation marks that indicate a quotation. Both ''quotation'' and ''quotation marks'' are sometimes abbreviated as "quote(s)".

...

from J. S. Bach's ''St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (german: Matthäus-Passion, links=-no), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets ...

'', and ''Family Tree'' for narrator and orchestra (1984), which invokes the musical language of Maurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

and American popular song. (He revered the ''St Matthew Passion'', and would play through it on the piano before commencing a new work, as a form of "purificatory ritual".)

By this time, Takemitsu's incorporation of traditional Japanese (and other Eastern) musical traditions with his Western style had become much more integrated. Takemitsu commented, "There is no doubt ... the various countries and cultures of the world have begun a journey toward the geographic and historic unity of all peoples ... The old and new exist within me with equal weight."

Toward the end of his life, Takemitsu had planned to complete an opera, a collaboration with the novelist Barry Gifford and the director Daniel Schmid

Daniel Walter Schmid (26 December 1941 – 5 August 2006) was a Swiss theatre and film director.

Biography

In 1982, his film '' Hécate'' was entered into the 33rd Berlin International Film Festival. His film '' Beresina, or the Last Days of ...

, commissioned by the Opéra National de Lyon

The Opéra National de Lyon, marketed as Opéra de Lyon during the last decade, is an opera company in Lyon, based and performing mostly at the Opéra Nouvel, an 1831 theater that was modernized and architecturally transformed in 1993.

The inaugu ...

in France. He was in the process of publishing a plan of its musical and dramatic structure with Kenzaburō Ōe

is a Japanese writer and a major figure in contemporary Japanese literature. His novels, short stories and essays, strongly influenced by French and American literature and literary theory, deal with political, social and philosophical issues, i ...

, but he was prevented from completing it by his death at 65. He died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

on 20 February 1996, while undergoing treatment for bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is any of several types of cancer arising from the tissues of the urinary bladder. Symptoms include blood in the urine, pain with urination, and low back pain. It is caused when epithelial cells that line the bladder become mali ...

.

Personal life

He was married to Asaka Takemitsu (formerly Wakayama) for 42 years. She first met Toru in 1951, cared for him when he was suffering fromtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in his early twenties, then married him in 1954. They had one child, a daughter named Maki. Asaka attended most premieres of his music and published a memoir of their life together in 2010.

Music

Composers whom Takemitsu cited as influential in his early work includeClaude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, Anton Webern

Anton Friedrich Wilhelm von Webern (3 December 188315 September 1945), better known as Anton Webern (), was an Austrian composer and conductor whose music was among the most radical of its milieu in its sheer concision, even aphorism, and stea ...

, Edgard Varèse

Edgard Victor Achille Charles Varèse (; also spelled Edgar; December 22, 1883 – November 6, 1965) was a French-born composer who spent the greater part of his career in the United States. Varèse's music emphasizes timbre and rhythm; he coined ...

, Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

, and Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonically ...

. Messiaen in particular was introduced to him by fellow composer Toshi Ichiyanagi

was a Japanese avant-garde composer and pianist. One of the leading composers in Japan during the postwar era, Ichiyanagi worked in a range of genres, composing Western-style operas and orchestral and chamber works, as well as compositions using ...

, and remained a lifelong influence. Although Takemitsu's wartime experiences of nationalism initially discouraged him from cultivating an interest in traditional Japanese music

Traditional Japanese music is the folk or traditional music of Japan. Japan's Ministry of Education classifies as a category separate from other traditional forms of music, such as (court music) or (Buddhist chanting), but most ethnomusicolog ...

, he showed an early interest in "... the Japanese Garden in color spacing and form ...". The formal garden of the ''kaiyu-shiki'' interested him in particular.

He expressed his unusual stance toward compositional theory early on, his lack of respect for the "trite rules of music, rules that are ... stifled by formulas and calculations"; for Takemitsu it was of far greater importance that "sounds have the freedom to breathe. ... Just as one cannot plan his life, neither can he plan music".

Takemitsu's sensitivity to instrumental and orchestral timbre can be heard throughout his work, and is often made apparent by the unusual instrumental combinations he specified. This is evident in works such as ''November Steps

is a musical composition by the Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu, for the traditional Japanese musical instruments, '' shakuhachi'' and '' biwa'', and western orchestra. The work was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic on the occasion of ...

'', that combine traditional Japanese instruments, ''shakuhachi

A is a Japanese and ancient Chinese longitudinal, end-blown flute that is made of bamboo.

The bamboo end-blown flute now known as the was developed in Japan in the 16th century and is called the .

'' and ''biwa

The is a Japanese short-necked wooden lute traditionally used in narrative storytelling. The is a plucked string instrument that first gained popularity in China before spreading throughout East Asia, eventually reaching Japan sometime duri ...

'', with a conventional Western orchestra. It may also be discerned in his works for ensembles that make no use of traditional instruments, for example ''Quotation of Dream'' (1991), ''Archipelago S.'', for 21 players (1993), and ''Arc I & II'' (1963–66/1976). In these works, the more conventional orchestral forces are divided into unconventional "groups". Even where these instrumental combinations were determined by the particular ensemble commissioning the work, "Takemitsu's genius for instrumentation (and genius it was, in my view) ...", in the words of Oliver Knussen

Stuart Oliver Knussen (12 June 1952 – 8 July 2018) was a British composer and conductor.

Early life

Oliver Knussen was born in Glasgow, Scotland. His father, Stuart Knussen, was principal double bass of the London Symphony Orchestra, and a ...

, "... creates the illusion that the instrumental restrictions are self-imposed".

Influence of traditional Japanese music

Takemitsu summarized his initial aversion to Japanese (and all non-Western) traditional musical forms in his own words: "There may be folk music with strength and beauty, but I cannot be completely honest in this kind of music. I want a more active relationship to the present. (Folk music in a 'contemporary style' is nothing but a deception)." His dislike for the musical traditions of Japan in particular were intensified by his experiences of the war, during which Japanese music became associated with militaristic and nationalistic cultural ideals. Nevertheless, Takemitsu incorporated some idiomatic elements of Japanese music in his very earliest works, perhaps unconsciously. One unpublished set of pieces, ''Kakehi'' ("Conduit"), written at the age of seventeen, incorporates the ''ryō'', ''ritsu'' and '' insen'' scales throughout. When Takemitsu discovered that these "nationalist" elements had somehow found their way into his music, he was so alarmed that he later destroyed the works. Further examples can be seen for example in the quarter-tone glissandi of ''Masques I'' (for two flutes, 1959), which mirror the characteristic pitch bends of the ''shakuhachi'', and for which he devised his own unique notation: a held note is tied to anenharmonic

In modern musical notation and tuning, an enharmonic equivalent is a note, interval, or key signature that is equivalent to some other note, interval, or key signature but "spelled", or named differently. The enharmonic spelling of a written n ...

spelling of the same pitch class, with a portamento

In music, portamento (plural: ''portamenti'', from old it, portamento, meaning "carriage" or "carrying") is a pitch sliding from one note to another. The term originated from the Italian expression "''portamento della voce''" ("carriage of the v ...

direction across the tie.

Other Japanese characteristics, including the further use of traditional pentatonic scale

A pentatonic scale is a musical scale with five notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven notes per octave (such as the major scale and minor scale).

Pentatonic scales were developed independently by many ancien ...

s, continued to crop up elsewhere in his early works. In the opening bars of ''Litany'', ''for Michael Vyner'', a reconstruction from memory by Takemitsu of ''Lento in Due Movimenti'' (1950; the original score was lost), pentatonicism is clearly visible in the upper voice, which opens the work on an unaccompanied anacrusis

In poetic and musical meter, and by analogy in publishing, an anacrusis (from , , literally: 'pushing up', plural ''anacruses'') is a brief introduction (distinct from a literary or musical introduction, foreword, or preface).

It is a set of s ...

. The pitches of the opening melody combine to form the constituent notes of the ascending form of the Japanese ''in'' scale.

When, from the early 1960s, Takemitsu began to "consciously apprehend" the sounds of traditional Japanese music, he found that his creative process, "the logic of my compositional thought was torn apart", and nevertheless, "hogaku raditional Japanese music ...seized my heart and refuses to release it". In particular, Takemitsu perceived that, for example, the sound of a single stroke of the ''biwa'' or single pitch breathed through the ''shakuhachi'', could "so transport our reason because they are of extreme complexity ... already complete in themselves". This fascination with the sounds produced in traditional Japanese music brought Takemitsu to his idea of '' ma'' (usually translated as the space between two objects), which ultimately informed his understanding of the intense quality of traditional Japanese music as a whole:

Just one sound can be complete in itself, for its complexity lies in the formulation of ''ma'', an unquantifiable metaphysical space (duration) of dynamically tensed absence of sound. For example, in the performance of ''nō'', the ''ma'' of sound and silence does not have an organic relation for the purpose of artistic expression. Rather, these two elements contrast sharply with one another in an immaterial balance.In 1970, Takemitsu received a commission from the

National Theatre of Japan

The is a complex consisting of three halls in two buildings in Hayabusachō, a district in Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. The Japan Arts Council, an Independent Administrative Institution of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Tec ...

to write a work for the ''gagaku

is a type of Japanese classical music that was historically used for imperial court music and dances. was developed as court music of the Kyoto Imperial Palace, and its near-current form was established in the Heian period (794-1185) around t ...

'' ensemble of the Imperial Household; this was fulfilled in 1973, when he completed ''Shuteiga'' ("In an Autumn Garden", although he later incorporated the work, as the fourth movement, into his 50-minute-long "In an Autumn Garden—Complete Version"). As well as being "... the furthest removed from the West of any work he had written", While it introduces certain Western musical ideas to the Japanese court ensemble, the work represents the deepest of Takemitsu's investigations into Japanese musical tradition, the lasting effects of which are clearly reflected in his works for conventional Western ensemble formats that followed.

In ''Garden Rain'' (1974, for brass ensemble), the limited and pitch-specific harmonic vocabulary of the Japanese mouth organ, the '' shō'' (see ex. 3), and its specific timbres, are clearly emulated in Takemitsu's writing for brass instruments; even similarities of performance practice can be seen, (the players are often required to hold notes to the limit of their breath capacity). In ''A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden'', the characteristic timbres of the ''shō'' and its chords (several of which are simultaneous soundings of traditional Japanese pentatonic scales) are emulated in the opening held chords of the wind instruments (the first chord is in fact an exact transposition of the ''shō's'' chord, Jū (i); see ex. 3); meanwhile a solo oboe is assigned a melodic line that is similarly reminiscent of the lines played by the ''hichiriki

The is a double reed Japanese used as one of two main melodic instruments in Japanese music. It is one of the "sacred" instruments and is often heard at Shinto weddings in Japan. Its sound is often described as haunting.

According to scholar ...

'' in ''gagaku'' ensembles.

Influence of Messiaen

The influence ofOlivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonically ...

on Takemitsu was already apparent in some of Takemitsu's earliest published works. By the time he composed ''Lento in Due Movimenti'', (1950), Takemitsu had already come into possession of a copy of Messiaen's '' 8 Préludes'' (through Toshi Ichiyanagi

was a Japanese avant-garde composer and pianist. One of the leading composers in Japan during the postwar era, Ichiyanagi worked in a range of genres, composing Western-style operas and orchestral and chamber works, as well as compositions using ...

), and the influence of Messiaen is clearly visible in the work, in the use of modes

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

, the suspension of regular metre, and sensitivity to timbre. Throughout his career, Takemitsu often made use of modes from which he derived his musical material, both melodic and harmonic among which Messiaen's modes of limited transposition Modes of limited transposition are musical modes or scales that fulfill specific criteria relating to their symmetry and the repetition of their interval groups. These scales may be transposed to all twelve notes of the chromatic scale, but at leas ...

to appear with some frequency. In particular, the use of the octatonic

An octatonic scale is any eight-Musical note, note musical scale. However, the term most often refers to the symmetric scale composed of alternating major second, whole and semitone, half steps, as shown at right. In classical theory (in contras ...

, (mode II, or the 8–28 collection), and mode VI (8–25) is particularly common. However, Takemitsu pointed out that he had used the octatonic collection in his music before ever coming across it in Messiaen's music.Koozin 1991, 125.

In 1975, Takemitsu met Messiaen in New York, and during "what was to be a one-hour 'lesson' ut whichlasted three hours ... Messiaen played his ''Quartet for the End of Time

''Quatuor pour la fin du temps'' (), originally ''Quatuor de la fin du temps'' ("''Quartet of the End of Time''"), also known by its English title ''Quartet for the End of Time'', is an eight-movement piece of chamber music by the French composer ...

'' for Takemitsu at the piano", which, Takemitsu recalled, was like listening to an orchestral performance.Takemitsu, Tōru, "The Passing of Nono, Feldman and Messiaen", ''Confronting Silence—Selected Writings'', trans./ed. Yoshiko Kakudo and Glen Glasgow, (Berkeley, 1995), 139–141. Takemitsu responded to this with his homage to the French composer, ''Quatrain'', for which he asked Messiaen's permission to use the same instrumental combination for the main quartet, cello, violin, clarinet and piano (which is accompanied by orchestra). As well as the obvious similarity of instrumentation, Takemitsu employs several melodic figures that appear to "mimic" certain musical examples given by Messiaen in his ''Technique de mon langage musical'', (see ex. 4). In 1977, Takemitsu reworked ''Quatrain'' for quartet alone, without orchestra, and titled the new work ''Quatrain II.''

On hearing of Messiaen's death in 1992, Takemitsu was interviewed by telephone, and still in shock, "blurted out, 'His death leaves a crisis in contemporary music!'" Then later, in an obituary written for the French composer in the same year, Takemitsu further expressed his sense of loss at Messiaen's death: "Truly, he was my spiritual mentor ... Among the many things I learned from his music, the concept and experience of color and the form of time will be unforgettable." The composition ''Rain Tree Sketch II'', which was to be Takemitsu's final piano piece, was also written that year and subtitled "In Memoriam Olivier Messiaen".

Influence of Debussy

Takemitsu frequently expressed his indebtedness toClaude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, referring to the French composer as his "great mentor". As Arnold Whittall

Arnold Whittall (born 1935, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England) is a British musicologist and writer. He is Professor Emeritus at King's College London. Between 1975 and 1996 he was Professor at King's. Previously he lectured at Cambridge, Nottingham ...

puts it:

Given the enthusiasm for the exotic and the Orient in these [Debussy and Messiaen] and other French composers, it is understandable that Takemitsu should have been attracted to the expressive and formal qualities of music in which flexibility of rhythm and richness of harmony count for so much.For Takemitsu, Debussy's "greatest contribution was his unique orchestration which emphasizes colour, light and shadow ... the orchestration of Debussy has many musical focuses." He was fully aware of Debussy's own interest in Japanese art, (the cover of the first edition of La mer (Debussy), ''La mer'', for example, was famously adorned by Hokusai's ''The Great Wave off Kanagawa''). For Takemitsu, this interest in Japanese culture, combined with his unique personality, and perhaps most importantly, his lineage as a composer of the French musical tradition running from Jean-Philippe Rameau, Rameau and Jean-Baptiste Lully, Lully through Hector Berlioz, Berlioz in which colour is given special attention, gave Debussy his unique style and sense of orchestration. During the composition of ''Green'' (''November Steps II'', for orchestra, 1967: "steeped in the sound-color world of the orchestral music of Claude Debussy") Takemitsu said he had taken the scores of Debussy's ''Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, Prélude à l'Après-midi d'un Faune'' and ''Jeux'' to the mountain villa where both this work and ''November Steps I'' were composed. For Oliver Knussen, "the final appearance of the main theme irresistibly prompts the thought that Takemitsu may, quite unconsciously, have been attempting a latter-day Japanese ''Après-midi d'un Faune''". Details of orchestration in ''Green'', such as the prominent use of antique cymbals, and ''tremolandi'' harmonies in the strings, clearly point to the influence of Takemitsu's compositional mentor, and of these works in particular. In ''Quotation of Dream'' (1991), direct Musical quotation, quotations from Debussy's ''La Mer'' and Takemitsu's earlier works relating to the sea are incorporated into the musical flow ("stylistic jolts were not intended"), depicting the landscape outside the Japanese garden of his own music.

Motives

Several recurring musical motives can be heard in Takemitsu's works. In particular the pitch motive E♭–E–A can be heard in many of his later works, whose titles refer to water in some form (''Toward the Sea'', 1981; ''Rain Tree Sketch'', 1982; ''I Hear the Water Dreaming'', 1987). When spelt in German (Es–E–A), the motive can be seen as a musical "transliteration" of the word "sea". Takemitsu used this motive (usually transposed) to indicate the presence of water in his "musical landscapes", even in works whose titles do not directly refer to water, such as ''A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden'' (1977; see ex. 5).''Musique concrète''

During Takemitsu's years as a member of the Jikken Kōbō, he experimented with compositions of ''musique concrète

Musique concrète (; ): " problem for any translator of an academic work in French is that the language is relatively abstract and theoretical compared to English; one might even say that the mode of thinking itself tends to be more schematic, ...

'' (and a very limited amount of electronic music

Electronic music is a genre of music that employs electronic musical instruments, digital instruments, or circuitry-based music technology in its creation. It includes both music made using electronic and electromechanical means ( electroac ...

, the most notable example being ''Stanza II'' for harp and tape written later in 1972). In ''Water Music'' (1960), Takemitsu's source material consisted entirely of sounds produced by droplets of water. His manipulation of these sounds, through the use of highly percussive envelopes, often results in a resemblance to traditional Japanese instruments, such as the ''tsuzumi'' and ''nō'' ensembles.

Aleatory techniques

One aspect ofJohn Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

's compositional procedure that Takemitsu continued to use throughout his career, was the use of aleatory, indeterminacy, in which performers are given a degree of choice in what to perform. As mentioned previously, this was particularly used in works such as ''November Steps'', in which musicians playing traditional Japanese instruments were able to play in an orchestral setting with a certain degree of improvisational freedom.

However, he also employed a technique that is sometimes called "aleatory counterpoint" in his well-known orchestral work ''A Flock Descends Into the Pentagonal Garden'' (1977, at [J] in the score), and in the score of ''Arc II: i Textures'' (1964) for piano and orchestra, in which sections of the orchestra are divided into groups, and required to repeat short passages of music at will. In these passages the overall sequence of events is, however, controlled by the conductor, who is instructed about the approximate durations for each section, and who indicates to the orchestra when to move from one section to next. The technique is commonly found in the work of Witold Lutosławski, who pioneered it in his ''Jeux vénitiens''.

Film music

Takemitsu's contribution to film music was considerable; in under 40 years he composed music for over 100 films, some of which were written for purely financial reasons (such as those written for Noboru Nakamura). However, as the composer attained financial independence, he grew more selective, often reading whole scripts before agreeing to compose the music, and later surveying the action on set, "breathing the atmosphere" whilst conceiving his musical ideas. One notable consideration in Takemitsu's composition for film was his careful use of silence (also important in many of his concert works), which often immediately intensifies the events on screen, and prevents any monotony through a continuous musical accompaniment. For the first battle scene ofAkira Kurosawa

was a Japanese filmmaker and painter who directed thirty films in a career spanning over five decades. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers in the history of cinema. Kurosawa displayed a bold, dyna ...

's ''Ran (film), Ran'', Takemitsu provided an extended passage of intense elegiac quality that halts at the sound of a single gunshot, leaving the audience with the pure "sounds of battle: cries screams and neighing horses".

Takemitsu attached the greatest importance to the director's conception of the film; in an interview with Max Tessier, he explained that, "everything depends on the film itself ... I try to concentrate as much as possible on the subject, so that I can express what the director feels himself. I try to extend his feelings with my music."

Legacy

In a memorial issue of ''Contemporary Music Review'', Jō Kondō wrote, "Needless to say, Takemitsu is among the most important composers in Japanese music history. He was also the first Japanese composer fully recognized in the west, and remained the guiding light for the younger generations of Japanese composers." Composer Peter Lieberson shared the following in his program note to ''The Ocean that has no East and West'', written in memory of Takemitsu: "I spent the most time with Toru in Tokyo when I was invited to be a guest composer at his Music Today Festival in 1987. Peter Serkin and composerOliver Knussen

Stuart Oliver Knussen (12 June 1952 – 8 July 2018) was a British composer and conductor.

Early life

Oliver Knussen was born in Glasgow, Scotland. His father, Stuart Knussen, was principal double bass of the London Symphony Orchestra, and a ...

were also there, as was cellist Fred Sherry. Though he was the senior of our group by many years, Toru stayed up with us every night and literally drank us under the table. I was confirmed in my impression of Toru as a person who lived his life like a traditional Zen poet."

On the death of his friend, the pianist Roger Woodward

Roger Woodward (born 20 December 1942) is an Australian classical pianist, composer, conductor and teacher.

Life and career Early life

The youngest of four children, Roger Woodward was born in Sydney where he received first piano lessons ...

composed "In Memoriam Toru Takemitsu" for unaccompanied violoncello. Woodward recalled concerts with Takemitsu in Australia, the Decca Studios and Roundhouse, London and at the 1976 ' Music Today' Festival, with Kinshi Tsuruta and Katsuya Yokoyama; Takemitu's dedication of "For Away", "Corona" (London Version) and "Undisturbed Rest" and of the inspirational leadership he provided Woodward's generation: " From all composers with whom I ever worked it was Toru Takemitsu who understood the inner workings of music and sound on a level unmatched by anyone else. His profound humility concealed an immense knowledge of Occidental and Oriental cultures which greatly extended historical contributions of Debussy and Messiaen."

In the foreword to a selection of Takemitsu's writings in English, conductor Seiji Ozawa

Seiji (written: , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , or in hiragana) is a masculine Japanese given name. Notable people with the name include:

*, Japanese ski jumper

*, Japanese racing driver

*, Japanese politician

*, Japanese film directo ...

writes: "I am very proud of my friend Toru Takemitsu. He is the first Japanese composer to write for a world audience and achieve international recognition."

Awards and honours

Takemitsu won awards for composition, both in Japan and abroad,Burton, Anthony"Takemitsu, Tōru"

''The Oxford Companion to Music'', ed. Alison Latham, (Oxford University Press, 2011), Oxford Reference Online, (subscription access). including the Prix Italia for his orchestral work ''Tableau noir'' in 1958, the Otaka Prize in 1976 and 1981, the Los Angeles Film Critics Award in 1987 (for the film score ''Ran'') and the University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition in 1994 (for ''Fantasma/Cantos''). In Japan, he received the Japan Academy Prize (film), Film Awards of the Japanese Academy for outstanding achievement in music, for soundtracks to the following films: * 1979 * 1985 Fire Festival (film) * 1986 * 1990 * 1996 He was also invited to attend numerous international festivals throughout his career, and presented lectures and talks at academic institutions across the world. He was made an honorary member of the Akademie der Künste of the DDR in 1979, and the American Institute of Arts and Letters in 1985. He was admitted to the French ''Ordre des Arts et des Lettres'' in 1985, and the ''Académie des Beaux-Arts'' in 1986. He was the recipient of the 22nd Suntory Music Award (1990). Posthumously, Takemitsu received a

Honorary Doctorate from Columbia University

early in 1996 and was awarded the fourth Glenn Gould Prize in fall 1996. The Toru Takemitsu Composition Award, intended to "encourage a younger generation of composers who will shape the coming age through their new musical works", is named after him.

Writings

* * Takemitsu, Tōru, with Cronin, Tania and Tann, Hilary, "Afterword", ''Perspectives of New Music

''Perspectives of New Music'' (PNM) is a peer-reviewed academic journal specializing in music theory and analysis. It was established in 1962 by Arthur Berger and Benjamin Boretz (who were its initial editors-in-chief).

''Perspectives'' was first ...

'', vol. 27, no. 2 (Summer, 1989), 205–214, (subscription access)

* Takemitsu, Tōru, (trans. Adachi, Sumi with Reynolds, Roger), "Mirrors", ''Perspectives of New Music'', vol. 30, no. 1 (Winter, 1992), 36–80, (subscription access)

* Takemitsu, Tōru, (trans. Hugh de Ferranti) "One Sound", ''Contemporary Music Review'', vol. 8, part 2, (Harwood, 1994), 3–4, (subscription access)

* Takemitsu, Tōru, "Contemporary Music in Japan", ''Perspectives of New Music'', vol. 27, no. 2 (Summer, 1989), 198–204 (subscription access)

References

Citations

Sources

* * * *Further reading

* * * *External links

Toru Takemitsu: Complete Works

*

Slate article focusing on his film music

Interview with Toru Takemitsu

* * *

on WNIB (defunct), WNIB Classical 97, Chicago, 6 March 1990 {{DEFAULTSORT:Takemitsu, Toru 1930 births 1996 deaths 20th-century classical composers 20th-century classical pianists 20th-century Japanese composers 20th-century Japanese guitarists 20th-century Japanese male musicians 20th-century musicologists Composers for the classical guitar Composers for piano Deaths from bladder cancer Deaths from cancer in Japan Deaths from pneumonia in Japan Deutsche Grammophon artists Georges Delerue Award winners Glenn Gould Prize winners International Rostrum of Composers prize-winners Japanese classical composers Japanese classical guitarists Japanese classical pianists Japanese electronic musicians Japanese film score composers Japanese male classical composers Japanese male classical pianists Japanese male film score composers Japanese television composers Male television composers Music theorists Musicians from Tokyo