Turgenev on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

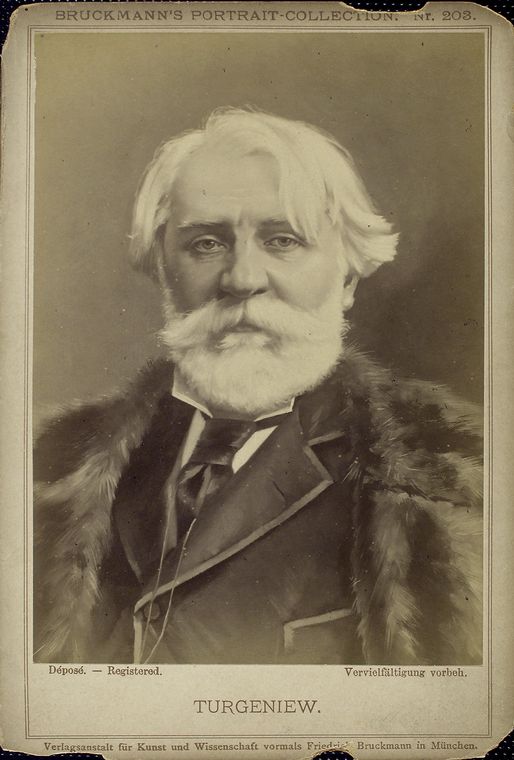

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist,

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist,

Unlike Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, Turgenev lacked religious motives in his writings, representing the more social aspect to the reform movement. He was considered to be an

Unlike Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, Turgenev lacked religious motives in his writings, representing the more social aspect to the reform movement. He was considered to be an

Turgenev first made his name with '' A Sportsman's Sketches'' (''Записки охотника''), also known as ''Sketches from a Hunter's Album'' or ''Notes of a Hunter'' or ''Memoirs of a Hunter'', a collection of short stories, based on his observations of peasant life and nature, while hunting in the forests around his mother's estate of Spasskoye. Most of the stories were published in a single volume in 1852, with others being added in later editions. The book is credited with having influenced public opinion in favour of the abolition of serfdom in 1861. Turgenev himself considered the book to be his most important contribution to Russian literature; it is reported that ''

Turgenev first made his name with '' A Sportsman's Sketches'' (''Записки охотника''), also known as ''Sketches from a Hunter's Album'' or ''Notes of a Hunter'' or ''Memoirs of a Hunter'', a collection of short stories, based on his observations of peasant life and nature, while hunting in the forests around his mother's estate of Spasskoye. Most of the stories were published in a single volume in 1852, with others being added in later editions. The book is credited with having influenced public opinion in favour of the abolition of serfdom in 1861. Turgenev himself considered the book to be his most important contribution to Russian literature; it is reported that ''

Turgenev's artistic purity made him a favorite of like-minded novelists of the next generation, such as

Turgenev's artistic purity made him a favorite of like-minded novelists of the next generation, such as

* 1850: ''Dnevnik lishnevo cheloveka'' (Дневник лишнего человека); novella, English translation: '' The Diary of a Superfluous Man''

* 1852: ''Zapiski okhotnika'' (Записки охотника); collection of stories, English translations: '' A Sportsman's Sketches'', ''The Hunter's Sketches'', ''A Sportsman's Notebook''

* 1854: " Mumu" (Муму); short story, English translation: '' Mumu''

* 1855: ''Yakov Pasynkov'' (Яков Пасынков); novella

* 1856: ''

* 1850: ''Dnevnik lishnevo cheloveka'' (Дневник лишнего человека); novella, English translation: '' The Diary of a Superfluous Man''

* 1852: ''Zapiski okhotnika'' (Записки охотника); collection of stories, English translations: '' A Sportsman's Sketches'', ''The Hunter's Sketches'', ''A Sportsman's Notebook''

* 1854: " Mumu" (Муму); short story, English translation: '' Mumu''

* 1855: ''Yakov Pasynkov'' (Яков Пасынков); novella

* 1856: ''

Ivan Turgenev poetry

Turgenev's works

(mainly in Russian)

Turgenev Museum in Bougival

*

by Nicholas Žekulin

by Richard Peace

English translations of 4 late Prose Poems

* English translation of eight late prose poems by Alexander Stillmark in '' Modern Poetry in Translation'', Series 2, No. 11 (1997). {{DEFAULTSORT:Turgenev, Ivan 1818 births 1883 deaths 19th-century dramatists and playwrights from the Russian Empire 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century novelists from the Russian Empire 19th-century poets from the Russian Empire Short story writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century translators from the Russian Empire Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Deaths from cancer in France Deaths from liposarcoma Deaths from spinal cancer English–Russian translators Moscow State University alumni Neurological disease deaths in France People from Orlovsky Uyezd (Oryol Governorate) People from Oryol Russian agnostics People from the Russian Empire of Tatar descent Russian–French translators Burials at Volkovo Cemetery

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist,

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story

A short story is a piece of prose fiction. It can typically be read in a single sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the old ...

writer, poet, playwright, translator and popularizer of Russian literature

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia, its Russian diaspora, émigrés, and to Russian language, Russian-language literature. Major contributors to Russian literature, as well as English for instance, are authors of different e ...

in the West.

His first major publication, a short story collection titled '' A Sportsman's Sketches'' (1852), was a milestone of Russian realism. His novel '' Fathers and Sons'' (1862) is regarded as one of the major works of 19th-century fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying character (arts), individuals, events, or setting (narrative), places that are imagination, imaginary or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent ...

.

Life

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev was born inOryol

Oryol ( rus, Орёл, , ɐˈrʲɵl, a=ru-Орёл.ogg, links=y, ), also transliterated as Orel or Oriol, is a Classification of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast, Russia, situated on the Oka Rive ...

(modern-day Oryol Oblast

Oryol Oblast (), also known as Orlovshchina (), is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative center is the types of inhabited localities in Russia, city of Oryol. Population:

Geography

It is loc ...

, Russia) to noble Russian parents Sergei Nikolaevich Turgenev (1793–1834), a colonel in the Russian cavalry who took part in the Patriotic War of 1812

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign (), the Second Polish War, and in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812 (), was initiated by Napoleon with the aim of compelling the Russian Empire to comply with the continent ...

, and Varvara Petrovna Turgeneva (née Lutovinova; 1787–1850). His father belonged to an old, but impoverished Turgenev family of Tula aristocracy that traces its history to the 15th century when a Tatar Mirza Lev Turgen (Ivan Turgenev after baptizing) left the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

to serve Vasily II of Moscow. Ivan's mother came from a wealthy noble Lutovinov house of the Oryol Governorate. She spent an unhappy childhood under her tyrannical stepfather and left his house after her mother's death to live with her uncle. At age 26, she inherited a huge fortune from him. In 1816, she married Turgenev.

Ivan and his brothers Nikolai and Sergei were raised by their mother, an educated, authoritarian woman. Their residence was the Spasskoye-Lutovinovo family estate that was granted to their ancestor Ivan Ivanovich Lutovinov by Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

. Varvara Turgeneva later served as an inspiration for the landlady from Turgenev's '' Mumu''. The brothers had foreign governesses; Ivan became fluent in French, German, and English. The family members used French in everyday life, including prayers. Their father spent little time with the family. Although he was not hostile toward them, his absence hurt Ivan's feelings. Their relations are described in the autobiographical novel '' First Love''. When Ivan was four years old, the family journeyed through Germany and France. In 1827, the Turgenevs relocated to Moscow to enable the children to have a proper education.

After the standard schooling for a son of a gentleman, Turgenev studied for one year at the University of Moscow

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, and six branches. Al ...

and then moved to the University of Saint Petersburg from 1834 to 1837, focusing on Classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

, Russian literature

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia, its Russian diaspora, émigrés, and to Russian language, Russian-language literature. Major contributors to Russian literature, as well as English for instance, are authors of different e ...

, and philology

Philology () is the study of language in Oral tradition, oral and writing, written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also de ...

. During that time his father died from kidney stone disease

Kidney stone disease (known as nephrolithiasis, renal calculus disease, or urolithiasis) is a crystallopathy and occurs when there are too many minerals in the urine and not enough liquid or hydration. This imbalance causes tiny pieces of cry ...

, followed by his younger brother Sergei who died from epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of Non-communicable disease, non-communicable Neurological disorder, neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked Seizure, seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activit ...

. From 1838 until 1841, he studied philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, particularly Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

, and history at the University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of Wilhelm von Humbol ...

. He returned to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

to complete his master's examination.

Turgenev was impressed with German society and returned home believing that Russia could best improve itself by incorporating ideas from the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

. Like many of his educated contemporaries, he was particularly opposed to serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

. In 1841, Turgenev started his career in the Russian civil service and spent two years working for the Ministry of Interior (1843–1845).

When Turgenev was a child, a family serf had read to him verses from the ''Rossiad'' of Mikhail Kheraskov

Mikhail Matveyevich Kheraskov (; – ) was a Russian poet and playwright. A leading figure of the Russian Enlightenment, Kheraskov was regarded as the most important Russian poet by Catherine the Great and her contemporaries.

Kheraskov's father ...

, a celebrated poet of the 18th century. Turgenev's early attempts in literature, poems, and sketches gave indications of genius and were favorably spoken of by Vissarion Belinsky, then the leading Russian literary critic. During the latter part of his life, Turgenev did not reside much in Russia: he lived either at Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden () is a spa town in the states of Germany, state of Baden-Württemberg, south-western Germany, at the north-western border of the Black Forest mountain range on the small river Oos (river), Oos, ten kilometres (six miles) east of the ...

or Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, often in proximity to the family of the celebrated opera singer Pauline Viardot

Pauline Viardot (; 18 July 1821 – 18 May 1910) was a French dramatic mezzo-soprano, composer and pedagogue of Spanish descent. Born Michelle Ferdinande Pauline García,FitzLyon, p. 15, referring to the baptismal name. Thbirth recorddigitized a ...

, with whom he had a lifelong affair.

Turgenev never married, but he had some affairs with his family's serfs, one of which resulted in the birth of his illegitimate daughter, Paulinette. He was tall and broad-shouldered, but was timid, restrained, and soft-spoken. When Turgenev was 19, while traveling on a steamboat in Germany, the boat caught fire. According to rumours by Turgenev's enemies, he reacted in a cowardly manner. He denied such accounts, but these rumours circulated in Russia and followed him for his entire career, providing the basis for his story " A Fire at Sea". His closest literary friend was Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , ; ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. He has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country and abroad. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flaubert, realis ...

, with whom he shared similar social and aesthetic ideas. Both rejected extremist right and left political views, and carried a nonjudgmental, although rather pessimistic, view of the world. His relations with Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

and Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian literature, Russian and world literature, and many of his works are consider ...

were often strained, as the two were, for various reasons, dismayed by Turgenev's seeming preference for Western Europe.

agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, the divine, or the supernatural is either unknowable in principle or unknown in fact. (page 56 in 1967 edition) It can also mean an apathy towards such religious belief and refer to ...

. Tolstoy, more than Dostoyevsky, at first anyway, rather despised Turgenev. While traveling together in Paris, Tolstoy wrote in his diary, "Turgenev is a bore." His rocky friendship with Tolstoy in 1861 wrought such animosity that Tolstoy challenged Turgenev to a duel, afterwards apologizing. The two did not speak for 17 years, but never broke family ties. Dostoyevsky parodies Turgenev in his novel '' The Devils'' (1872) through the character of the vain novelist Karmazinov, who is anxious to ingratiate himself with the radical youth. However, in 1880, Dostoevsky's Pushkin Speech at the unveiling of the Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

monument brought about a reconciliation of sorts with Turgenev, who, like many in the audience, was moved to tears by his rival's eloquent tribute to the Russian spirit.

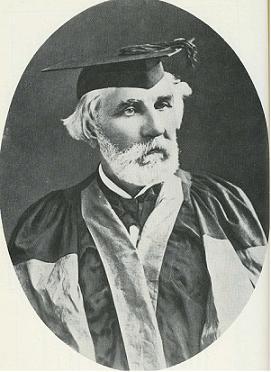

Turgenev occasionally visited England, and in 1879 the honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law

Doctor of Civil Law (DCL; ) is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

At Oxford, the degree is a higher doctorate usually awarded on the basis of except ...

was conferred upon him by the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

.

Turgenev's health declined during his later years. In January 1883, an aggressive malignant tumor (liposarcoma

Liposarcomas are the most common subtype of soft tissue sarcomas, accounting for at least 20% of all sarcomas in adults. Soft tissue sarcomas are rare neoplasms with over 150 different histological subtypes or forms. Liposarcomas arise from the ...

) was removed from his suprapubic

The hypogastrium (also called the hypogastric region or suprapubic region) is a region of the abdomen located below the umbilical region.

Etymology

The roots of the word ''hypogastrium'' mean "below the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, ...

region, but by then the tumor had metastasized in his upper spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

, causing him intense pain during the final months of his life. On 3 September 1883, Turgenev died of a spinal abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body, usually caused by bacterial infection. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pre ...

, a complication of the metastatic liposarcoma, in his house at Bougival

Bougival () is a suburban commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region in Northern France. It is located west from the centre of Paris, on the left bank of the River Seine, on the departmental border with Hauts-de-Seine. In ...

near Paris. His remains were taken to Russia and buried in Volkovo Cemetery in St. Petersburg. On his deathbed, he pleaded with Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

: "My friend, return to literature!" After this, Tolstoy wrote such works as '' The Death of Ivan Ilyich'' and '' The Kreutzer Sonata''.

Ivan Turgenev's brain was found to be one of the largest on record, weighing .

Work

Turgenev first made his name with '' A Sportsman's Sketches'' (''Записки охотника''), also known as ''Sketches from a Hunter's Album'' or ''Notes of a Hunter'' or ''Memoirs of a Hunter'', a collection of short stories, based on his observations of peasant life and nature, while hunting in the forests around his mother's estate of Spasskoye. Most of the stories were published in a single volume in 1852, with others being added in later editions. The book is credited with having influenced public opinion in favour of the abolition of serfdom in 1861. Turgenev himself considered the book to be his most important contribution to Russian literature; it is reported that ''

Turgenev first made his name with '' A Sportsman's Sketches'' (''Записки охотника''), also known as ''Sketches from a Hunter's Album'' or ''Notes of a Hunter'' or ''Memoirs of a Hunter'', a collection of short stories, based on his observations of peasant life and nature, while hunting in the forests around his mother's estate of Spasskoye. Most of the stories were published in a single volume in 1852, with others being added in later editions. The book is credited with having influenced public opinion in favour of the abolition of serfdom in 1861. Turgenev himself considered the book to be his most important contribution to Russian literature; it is reported that ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'', and Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

, among others, agreed wholeheartedly, adding that Turgenev's evocations of nature in these stories were unsurpassed. One of the stories in ''A Sportsman's Sketches'', known as "Bezhin Lea" or "Byezhin Prairie", was later to become the basis for the controversial film '' Bezhin Meadow'' (1937), directed by Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein; (11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, screenwriter, film editor and film theorist. Considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, he was a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is no ...

.

In 1852, when his first major novels of Russian society were still to come, Turgenev wrote an obituary for Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the Grotesque#In literature, grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works "The Nose (Gogol short story), ...

, intended for publication in the ''Saint Petersburg Gazette''. The key passage reads: "Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works " The Nose", " Viy", "The Overcoat", and " Nevsky Prosp ...

is dead!... What Russian heart is not shaken by those three words?... He is gone, that man whom we now have the right (the bitter right, given to us by death) to call great." The censor of Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

did not approve of this and banned publication, but the Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

censor allowed it to be published in a newspaper in that city. The censor was dismissed; but Turgenev was held responsible for the incident, imprisoned for a month, and then exiled to his country estate for nearly two years. It was during this time that Turgenev wrote his short story ''Mumu'' ("Муму") in 1854. The story tells a tale of a deaf and mute peasant who is forced to drown the only thing in the world which brings him happiness, his dog Mumu. Like his '' A Sportsman's Sketches'' (''Записки охотника''), this work takes aim at the cruelties of a serf society. This work was later applauded by John Galsworthy

John Galsworthy (; 14 August 1867 – 31 January 1933) was an English novelist and playwright. He is best known for his trilogy of novels collectively called '' The Forsyte Saga'', and two later trilogies, ''A Modern Comedy'' and ''End of th ...

who claimed, "no more stirring protest against tyrannical cruelty was ever penned in terms of art."

While he was still in Russia in the early 1850s, Turgenev wrote several novellas (''povesti'' in Russian): '' The Diary of a Superfluous Man'' ("Дневник лишнего человека"), ''Faust

Faust ( , ) is the protagonist of a classic German folklore, German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust (). The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a deal with the Devil at a ...

'' ("Фауст"), ''The Lull'' ("Затишье"), expressing the anxieties and hopes of Russians of his generation.

In the 1840s and early 1850s, during the rule of Tsar Nicholas I, the political climate in Russia was stifling for many writers. This is evident in the despair and subsequent death of Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works " The Nose", " Viy", "The Overcoat", and " Nevsky Prosp ...

, and the oppression, persecution, and arrests of artists, scientists, and writers. During this time, thousands of Russian intellectuals, members of the ''intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

'', emigrated to Europe. Among them were Alexander Herzen

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (; ) was a Russian writer and thinker known as the precursor of Russian socialism and one of the main precursors of agrarian populism (being an ideological ancestor of the Narodniki, Socialist-Revolutionaries, Trudo ...

and Turgenev himself, who moved to Western Europe in 1854, although this decision probably had more to do with his fateful love for Pauline Viardot

Pauline Viardot (; 18 July 1821 – 18 May 1910) was a French dramatic mezzo-soprano, composer and pedagogue of Spanish descent. Born Michelle Ferdinande Pauline García,FitzLyon, p. 15, referring to the baptismal name. Thbirth recorddigitized a ...

than anything else.

The following years produced the novel '' Rudin'' ("Рудин"), the story of a man in his thirties who is unable to put his talents and idealism to any use in the Russia of Nicholas I. ''Rudin'' is also full of nostalgia for the idealistic student circles of the 1840s.

Following the thoughts of the influential critic Vissarion Belinsky, Turgenev abandoned Romantic idealism for a more realistic style. Belinsky defended sociological realism in literature; Turgenev portrayed him in ''Yakov Pasinkov'' (1855). During the period of 1853–62 Turgenev wrote some of his finest stories as well as the first four of his novels: '' Rudin'' ("Рудин") (1856), '' A Nest of the Gentry'' ("Дворянское гнездо") (1859), '' On the Eve'' ("Накануне") (1860) and '' Fathers and Sons'' ("Отцы и дети") (1862). Some themes involved in these works include the beauty of early love, failure to reach one's dreams, and frustrated love. Great influences on these works are derived from his love of Pauline and his experiences with his mother, who controlled over 500 serfs with the same strict demeanor in which she raised him.

In 1858 Turgenev wrote the novel '' A Nest of the Gentry'' ("Дворянское гнездо"), also full of nostalgia for the irretrievable past and of love for the Russian countryside. It contains one of his most memorable female characters, Liza, to whom Dostoyevsky paid tribute in his Pushkin speech of 1880, alongside Tatiana and Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

's Natasha Rostova.

Alexander II ascended the Russian throne in 1855, and the political climate became more relaxed. In 1859, inspired by reports of positive social changes, Turgenev wrote the novel '' On the Eve'' ("Накануне") (published 1860), portraying the Bulgarian revolutionary Insarov.

The following year saw the publication of one of his finest novellas, '' First Love'' ("Первая любовь"), which was based on bitter-sweet childhood memories, and the delivery of his speech (" Hamlet and Don Quixote", at a public reading in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

) in aid of writers and scholars suffering hardship. The vision presented therein of man torn between the self-centered skepticism of Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play. Set in Denmark, the play (the ...

and the idealistic generosity of Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

is one that can be said to pervade Turgenev's own works. It is worth noting that Dostoyevsky, who had just returned from exile in Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, was present at this speech, for eight years later he was to write ''The Idiot

''The Idiot'' (Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform ) is a novel by the 19th-century Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. It was first published serially in the journal ''The Russian Messenger'' in 1868–1869.

The titl ...

'', a novel whose tragic hero, Prince Myshkin

Prince Lev Nikolayevich Myshkin ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform ) is the titular main protagonist of Fyodor Dostoevsky's 1869 novel ''The Idiot''. Dostoevsky wanted to create a character that was "entirely positive... with an absolutely beautif ...

, resembles Don Quixote in many respects. Turgenev, whose knowledge of Spanish, thanks to his contact with Pauline Viardot

Pauline Viardot (; 18 July 1821 – 18 May 1910) was a French dramatic mezzo-soprano, composer and pedagogue of Spanish descent. Born Michelle Ferdinande Pauline García,FitzLyon, p. 15, referring to the baptismal name. Thbirth recorddigitized a ...

and her family, was good enough for him to have considered translating Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his no ...

's novel into Russian, played an important role in introducing this immortal figure of world literature into the Russian context.

'' Fathers and Sons'' ("Отцы и дети"), Turgenev's most famous and enduring novel, appeared in 1862. Its leading character, Eugene Bazarov, considered the "first Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

" in Russian literature, was in turn heralded and reviled as either a glorification or a parody of the 'new men' of the 1860s. The novel examined the conflict between the older generation, reluctant to accept reforms, and the nihilistic youth. In the central character, Bazarov, Turgenev drew a classical portrait of the mid-nineteenth-century nihilist. ''Fathers and Sons'' was set during the six-year period of social ferment, from Russia's defeat in the Crimean War to the Emancipation of the Serfs. Hostile reaction to ''Fathers and Sons'' ("Отцы и дети") prompted Turgenev's decision to leave Russia. As a consequence he also lost the majority of his readers. Many radical critics at the time (with the notable exception of Dimitri Pisarev) did not take ''Fathers and Sons'' seriously; and, after the relative critical failure of his masterpiece, Turgenev was disillusioned and started to write less.

Turgenev's next novel, ''Smoke

Smoke is an aerosol (a suspension of airborne particulates and gases) emitted when a material undergoes combustion or pyrolysis, together with the quantity of air that is entrained or otherwise mixed into the mass. It is commonly an unwante ...

'' ("Дым"), was published in 1867 and was again received less than enthusiastically in his native country, as well as triggering a quarrel with Dostoyevsky in Baden-Baden.

His last substantial work attempting to do justice to the problems of contemporary Russian society, '' Virgin Soil'' ("Новь"), was published in 1877.

Stories of a more personal nature, such as '' Torrents of Spring'' ("Вешние воды"), ''King Lear of the Steppes'' ("Степной король Лир"), and '' The Song of Triumphant Love'' ("Песнь торжествующей любви"), were also written in these autumnal years of his life. Other last works included the '' Poems in Prose'' and "Clara Milich" ("After Death"), which appeared in the journal ''European Messenger''.

Turgenev wrote on themes similar to those found in the works of Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using pre-reform Russian orthography. ; ), usually referr ...

and Dostoyevsky, but he did not approve of the religious and moral preoccupations that his two great contemporaries brought to their artistic creation. Turgenev was closer in temperament to his friends Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , ; ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. He has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country and abroad. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flaubert, realis ...

and Theodor Storm, the North German poet and master of the novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

form, who also often dwelt on memories of the past and evoked the beauty of nature.

Legacy

Turgenev's artistic purity made him a favorite of like-minded novelists of the next generation, such as

Turgenev's artistic purity made him a favorite of like-minded novelists of the next generation, such as Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

and Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

, both of whom greatly preferred Turgenev to Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. James, who wrote no fewer than five critical essays on Turgenev's work, claimed that "his merit of form is of the first order" (1873) and praised his "exquisite delicacy", which "makes too many of his rivals appear to hold us, in comparison, by violent means, and introduce us, in comparison, to vulgar things" (1896). Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov ( ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian and American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Born in Imperial Russia in 1899, Nabokov wrote his first nine novels in Rus ...

, notorious for his casual dismissal of many great writers, praised Turgenev's "plastic musical flowing prose", but criticized his "labored epilogues" and "banal handling of plots". Nabokov stated that Turgenev "is not a great writer, though a pleasant one", and ranked him fourth among nineteenth-century Russian prose writers, behind Tolstoy, Gogol, and Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; ; 29 January 1860 – 15 July 1904) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer, widely considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career as a playwright produced four classics, and his b ...

, but ahead of Dostoyevsky. His idealistic ideas about love, specifically the devotion a wife should show her husband, were cynically referred to by characters in Chekhov's "An Anonymous Story". Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

acclaimed Turgenev's commitment to humanism, pluralism, and gradual reform over violent revolution as representing the best aspects of Russian liberalism.

Antisemitism

Turgenev was known for his pejorative descriptions of Jews, for example in his story " The Jew" (1847). (The story's title in Russian, "жид" ( zhyd), is apejorative

A pejorative word, phrase, slur, or derogatory term is a word or grammatical form expressing a negative or disrespectful connotation, a low opinion, or a lack of respect toward someone or something. It is also used to express criticism, hosti ...

.) The story describes a "zhyd" named Girshel as short and thin, with red hair, reddish eyes that he blinks constantly, and a long and crooked nose. He pursues his greed to the point of prostituting his daughter and is quoted as saying that "money is a good thing, you can get anything with it". Girschel is described as heartbroken, and in the description of his trial on charges of espionage, he is sentenced to death. Turgenev describes him as shaking with his whole body, shouting and meowing, "until he involuntarily brought a smile to our faces." In a similar way, the beating of another Jew and the attempt to kill him is described as being met with laughter from the audience.

Publications

Novels

* 1856: '' Rudin'' * 1859: '' Home of the Gentry'' (Дворянское гнездо), also translated as ''A Nest of Gentlefolk'', ''A House of Gentlefolk'' and ''Liza'' * 1860: '' On the Eve'' (Накануне) * 1862: '' Fathers and Sons'' (Отцы и дети), also translated as ''Fathers and Children'' * 1867: ''Smoke

Smoke is an aerosol (a suspension of airborne particulates and gases) emitted when a material undergoes combustion or pyrolysis, together with the quantity of air that is entrained or otherwise mixed into the mass. It is commonly an unwante ...

'' (Дым)

* 1872: '' Torrents of Spring'' (Вешние воды)

* 1877: '' Virgin Soil'' (Новь)

* 1884: "The Shooting Party (Chekhov novel)

''The Shooting Party'' (; English: ''Drama During a Hunt'') is an 1884 novel by Anton Chekhov. It is his longest narrative work, and only full-length novel. Framed as a manuscript given to a publisher, it tells the story of an estate forester ...

" (published posthumously after Turgenev's death)

Selected shorter fiction

* 1850: ''Dnevnik lishnevo cheloveka'' (Дневник лишнего человека); novella, English translation: '' The Diary of a Superfluous Man''

* 1852: ''Zapiski okhotnika'' (Записки охотника); collection of stories, English translations: '' A Sportsman's Sketches'', ''The Hunter's Sketches'', ''A Sportsman's Notebook''

* 1854: " Mumu" (Муму); short story, English translation: '' Mumu''

* 1855: ''Yakov Pasynkov'' (Яков Пасынков); novella

* 1856: ''

* 1850: ''Dnevnik lishnevo cheloveka'' (Дневник лишнего человека); novella, English translation: '' The Diary of a Superfluous Man''

* 1852: ''Zapiski okhotnika'' (Записки охотника); collection of stories, English translations: '' A Sportsman's Sketches'', ''The Hunter's Sketches'', ''A Sportsman's Notebook''

* 1854: " Mumu" (Муму); short story, English translation: '' Mumu''

* 1855: ''Yakov Pasynkov'' (Яков Пасынков); novella

* 1856: ''Faust

Faust ( , ) is the protagonist of a classic German folklore, German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust (). The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a deal with the Devil at a ...

'' (Фауст); novella

* 1858: '' Asya'' (Ася); novella, English translation: ''Asya'' or ''Annouchka''

* 1860: ''Pervaya lyubov'' (Первая любовь); novella, English translation: '' First Love''

* 1870: ''Stepnoy korol Lir'' (Степной король Лир); novella, English translation: '' King Lear of the Steppes''

* 1881: ''Pesn torzhestvuyushchey lyubvi'' (Песнь торжествующей любви); novella, English translation: '' The Song of Triumphant Love''

* 1883: ''Klara Milich'' (Клара Милич); novella, English translation: '' The Mysterious Tales''

Plays

* 1843: ''A Rash Thing to Do'' (Неосторожность) * 1847: ''It Tears Where It Is Thin'' (Где тонко, там и рвётся) * 1849/1856: ''Breakfast at the Chief's'' (Завтрак у предводителя) * 1850/1851: ''A Conversation on the Highway'' (Разговор на большой дороге) * 1846/1852: ''Lack of Money'' (Безденежье) * 1851: '' A Provincial Lady'' (Провинциалка) * 1857/1862: '' Fortune's Fool'' (Нахлебник), also translated as ''The Hanger-On'' and ''The Family Charge'' * 1855/1872: '' A Month in the Country'' (Месяц в деревне) * 1882: ''An Evening in Sorrento'' (Вечер в Сорренто)Other

* 1877–1882: '' Poems in Prose'' (Стихотворения в прозе)See also

* Alexander Dmitriyevich Kastalsky who composed an opera based on the novella ''Klara Milich'' * SirFrederick Ashton

Sir Frederick William Mallandaine Ashton (17 September 190418 August 1988) was a British ballet dancer and choreographer. He also worked as a director and choreographer in opera, film and revue.

Determined to be a dancer despite the oppositio ...

, who created a ballet based on '' A Month in the Country'' in 1976

* Asteroid 3323 Turgenev, named after the writer

* Lee Hoiby

Lee Henry Hoiby (February 17, 1926 – March 28, 2011) was an American composer and classical pianist. Best known as a composer of operas and songs, he was a disciple of composer Gian Carlo Menotti. Like Menotti, his works championed lyricism at ...

, an American composer and his opera based on '' A Month in the Country''

* Vladimir Rebikov, who composed an opera based on '' Home of the Gentry'' in 1916

* Galina Ulanova, who advised her pupils to read such stories of Turgenev's as " Asya" or '' Torrents of Spring'' when preparing to dance Giselle

Notes

Explanatory notes

Citations

References

* Cecil, David. 1949. "Turgenev", in David Cecil, ''Poets and Story-tellers: A Book of Critical Essays''. New York: Macmillan Co.: 123–38. * Freeborn, Richard. 1960. ''Turgenev: The Novelist's Novelist, a Study''. London: Oxford University Press. * Magarshack, David. 1954. ''Turgenev: A Life''. London: Faber and Faber. * Sokolowska, Katarzyna. 2011. ''Conrad and Turgenev: Towards the Real''. Boulder: Eastern European Monographs. * Troyat, Henri. 1988. ''Turgenev''. New York: Dutton. * Yarmolinsky, Avrahm. 1959. ''Turgenev, the Man, His Art and His Age''. New York: Orion Press.External links

* * * *Ivan Turgenev poetry

Turgenev's works

(mainly in Russian)

Turgenev Museum in Bougival

*

by Nicholas Žekulin

by Richard Peace

English translations of 4 late Prose Poems

* English translation of eight late prose poems by Alexander Stillmark in '' Modern Poetry in Translation'', Series 2, No. 11 (1997). {{DEFAULTSORT:Turgenev, Ivan 1818 births 1883 deaths 19th-century dramatists and playwrights from the Russian Empire 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century novelists from the Russian Empire 19th-century poets from the Russian Empire Short story writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century translators from the Russian Empire Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Deaths from cancer in France Deaths from liposarcoma Deaths from spinal cancer English–Russian translators Moscow State University alumni Neurological disease deaths in France People from Orlovsky Uyezd (Oryol Governorate) People from Oryol Russian agnostics People from the Russian Empire of Tatar descent Russian–French translators Burials at Volkovo Cemetery