Tokyo Trials on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to

The Tribunal was established to implement the Cairo Declaration, the

The Tribunal was established to implement the Cairo Declaration, the

On January 19, 1946, MacArthur issued a special proclamation ordering the establishment of an International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). On the same day, he also approved the Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (CIMTFE), which prescribed how it was to be formed, the crimes that it was to consider, and how the tribunal was to function. The charter generally followed the model set by the

On January 19, 1946, MacArthur issued a special proclamation ordering the establishment of an International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). On the same day, he also approved the Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (CIMTFE), which prescribed how it was to be formed, the crimes that it was to consider, and how the tribunal was to function. The charter generally followed the model set by the

Following months of preparation, the IMTFE convened on April 29, 1946. The trials were held in the War Ministry office in Tokyo.

On May 3 the prosecution opened its case, charging the defendants with crimes against peace, conventional war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The trial continued for more than two and a half years, hearing testimony from 419 witnesses and admitting 4,336 exhibits of evidence, including depositions and affidavits from 779 other individuals.

Following months of preparation, the IMTFE convened on April 29, 1946. The trials were held in the War Ministry office in Tokyo.

On May 3 the prosecution opened its case, charging the defendants with crimes against peace, conventional war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The trial continued for more than two and a half years, hearing testimony from 419 witnesses and admitting 4,336 exhibits of evidence, including depositions and affidavits from 779 other individuals.

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try

Try or TRY may refer to:

Music Albums

* ''Try!'', an album by the John Mayer Trio

* ''Try'' (Bebo Norman album) (2014) Songs

* "Try" (Blue Rodeo song) (1987)

* "Try" (Colbie Caillat song) (2014)

* "Try" (Nelly Furtado song) (2004)

* " Try (Ju ...

leaders of the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

for crimes against peace

A crime of aggression or crime against peace is the planning, initiation, or execution of a large-scale and serious act of aggression using state military force. The definition and scope of the crime is controversial. The Rome Statute contains an ...

, conventional war crimes, and crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

leading up to and during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. It was modeled after the International Military Tribunal

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

(IMT) formed several months earlier in Nuremberg, Germany to prosecute senior officials of Nazi Germany.

Following Japan's defeat and occupation by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milita ...

, United States General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

, issued a special proclamation establishing the IMTFE. A charter was drafted to establish the court's composition, jurisdiction, procedures; the crimes were defined based on the Nuremberg charter. The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal was composed of judges, prosecutors, and staff from eleven countries that had fought against Japan: Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

; the defense comprised Japanese and American lawyers.

The Tokyo Trial exercised broader temporal jurisdiction than its counterpart in Nuremberg, beginning from the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Twenty-eight high-ranking Japanese military and political leaders were tried by the court, including current and former prime ministers, foreign ministers, and military commanders. They were charged with fifty-five separate counts, including the waging wars of aggression

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation.

Wars without international legality (i.e. not out of self-defense nor sanc ...

, murder, and various war crimes and crimes against humanity (such as torture and forced labor) against prisoners-of-war, civilian internees, and the inhabitants of occupied territories; ultimately, 45 of the counts, including all the murder charges, were ruled either redundant or not authorized under the IMTFE Charter.

By the time it adjourned on November 12, 1948, two defendants had died of natural causes and one

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1. I ...

was ruled unfit to stand trial. All remaining defendants were found guilty of at least one count, of whom seven were sentenced to death and sixteen to life imprisonment. Thousands of other "lesser" war criminals were tried by domestic tribunals convened across Asia and the Pacific by Allied nations, with most concluding by 1949.

The Tokyo Trial lasted more than twice as long as the better-known Nuremberg trials, and its impact was similarly influential in the development of international law; similar international war crimes tribunals would not be established until the 1990s.

Background

The Tribunal was established to implement the Cairo Declaration, the

The Tribunal was established to implement the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

, the Instrument of Surrender, and the Moscow Conference. The Potsdam Declaration (July 1945) had stated, "stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners," though it did not specifically foreshadow trials. The terms of reference for the Tribunal were set out in the IMTFE Charter, issued on January 19, 1946. There was major disagreement, both among the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and within their administrations, about whom to try and how to try them. Despite the lack of consensus, General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milita ...

, decided to initiate arrests. On September 11, a week after the surrender, he ordered the arrest of 39 suspects—most of them members of General Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

's war cabinet. Tojo tried to commit suicide but was resuscitated with the help of U.S. physicians.

Creation of the court

On January 19, 1946, MacArthur issued a special proclamation ordering the establishment of an International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). On the same day, he also approved the Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (CIMTFE), which prescribed how it was to be formed, the crimes that it was to consider, and how the tribunal was to function. The charter generally followed the model set by the

On January 19, 1946, MacArthur issued a special proclamation ordering the establishment of an International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). On the same day, he also approved the Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (CIMTFE), which prescribed how it was to be formed, the crimes that it was to consider, and how the tribunal was to function. The charter generally followed the model set by the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

. On April 25, in accordance with the provisions of Article 7 of the CIMTFE, the original Rules of Procedure of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East with amendments were promulgated.

Tokyo War Crimes Trial

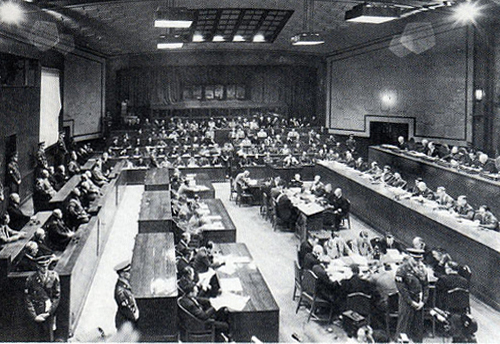

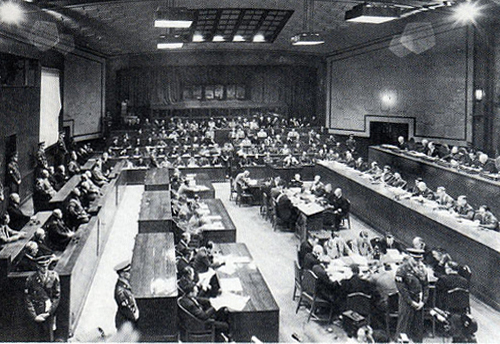

Following months of preparation, the IMTFE convened on April 29, 1946. The trials were held in the War Ministry office in Tokyo.

On May 3 the prosecution opened its case, charging the defendants with crimes against peace, conventional war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The trial continued for more than two and a half years, hearing testimony from 419 witnesses and admitting 4,336 exhibits of evidence, including depositions and affidavits from 779 other individuals.

Following months of preparation, the IMTFE convened on April 29, 1946. The trials were held in the War Ministry office in Tokyo.

On May 3 the prosecution opened its case, charging the defendants with crimes against peace, conventional war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The trial continued for more than two and a half years, hearing testimony from 419 witnesses and admitting 4,336 exhibits of evidence, including depositions and affidavits from 779 other individuals.

Charges

Following the model used at the Nuremberg trials in Germany, the Allies established three broad categories. "Class A" charges, alleging crimes against peace, were to be brought against Japan's top leaders who had planned and directed the war. Class B and C charges, which could be leveled at Japanese of any rank, covered conventional war crimes and crimes against humanity, respectively. Unlike the Nuremberg trials, the charge of crimes against peace was a prerequisite to prosecution—only those individuals whose crimes included crimes against peace could be prosecuted by the Tribunal. In the event, no Class C charges were heard in Tokyo. The indictment accused the defendants of promoting a scheme of conquest that:ntemplated and carried out ... murdering, maiming and ill-treatingKeenan issued a press statement along with the indictment: "War and treaty-breakers should be stripped of the glamour of national heroes and exposed as what they really are—plain, ordinary murderers."prisoners of war A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610. Belligerents hold priso ...(and)civilian internee A civilian internee is a civilian detained by a party to a war for security reasons. Internees are usually forced to reside in internment camps. Historical examples include Japanese American internment and internment of German Americans in the Unit ...s ... forcing them to labor under inhumane conditions ...plundering Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...public In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...andprivate property Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property and personal property, which is owned by a state entity, and from collective or ..., wantonly destroyingcities A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...,town A town is a human settlement. Towns are generally larger than villages and smaller than cities, though the criteria to distinguish between them vary considerably in different parts of the world. Origin and use The word "town" shares an ori ...s andvillage A village is a clustered human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet but smaller than a town (although the word is often used to describe both hamlets and smaller towns), with a population typically ranging from a few hundred to ...s beyond any justification ofmilitary necessity Military necessity, along with distinction, and proportionality, are three important principles of international humanitarian law governing the legal use of force in an armed conflict. Attacks Military necessity is governed by several constra ...; (perpetrating)mass murder Mass murder is the act of murdering a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. The United States Congress defines mass killings as the killings of three or more pe ...,rape Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ag ..., pillage,brigandage Brigandage is the life and practice of highway robbery and plunder. It is practiced by a brigand, a person who usually lives in a gang and lives by pillage and robbery.Oxford English Dictionary second edition, 1989. "Brigand.2" first recorded usa ...,torture Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts c ...and other barbaric cruelties upon the helplesscivilian Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not "combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant, b ...population Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using a ...of the over-run countries.

Evidence and testimony

Any possible evidence that would incriminateEmperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

and his family was excluded from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, as the United States believed it needed him to maintain order in Japan and achieve their postwar objectives.

The prosecution began opening statements on May 3, 1946, and took 192 days to present its case, finishing on January 24, 1947. It submitted its evidence in fifteen phases.

The Tribunal embraced the best evidence rule

The best evidence rule is a legal principle that holds an original of a document as superior evidence. The rule specifies that secondary evidence, such as a copy or facsimile, will be not admissible if an original document exists and can be obtai ...

once the Prosecution had rested. The best evidence rule dictates that the "best" or most authentic evidence must be produced (for example, a map instead of a description of the map; an original instead of a copy; and a witness instead of a description of what the witness may have said). Justice Pal, one of two justices to vote for acquittal on all counts, observed, "in a proceeding where we had to allow the prosecution to bring in any amount of hearsay evidence, it was somewhat misplaced caution to introduce this best evidence rule particularly when it operated practically against the defense only."

To prove their case, the prosecution team relied on the doctrine of "command responsibility

Command responsibility (superior responsibility, the Yamashita standard, and the Medina standard) is the legal doctrine of hierarchical accountability for war crimes.

." This doctrine was that it did not require proof of criminal orders. The prosecution had to prove three things: that war crimes were systematic or widespread; the accused knew that troops were committing atrocities; and the accused had power or authority to stop the crimes.

Part of Article 13 of the Charter provided that evidence against the accused could include any document "without proof of its issuance or signature" as well as diaries, letters, press reports, and sworn or unsworn out-of-court statements relating to the charges. Article 13 of the Charter read, in part: "The tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence ... and shall admit any evidence which it deems to have probative value.

The prosecution argued that a 1927 document known as the Tanaka Memorial

The is an alleged Japanese strategic planning document from 1927 in which Prime Minister Baron Tanaka Giichi laid out for Emperor Hirohito a strategy to take over the world. The authenticity of the document was long accepted and it is still quot ...

showed that a "common plan or conspiracy" to commit "crimes against peace" bound the accused together. Thus, the prosecution argued that the conspiracy had begun in 1927 and continued through to the end of the war in 1945. The Tanaka Memorial is now considered by most historians to have been an anti-Japanese forgery; however, it was not regarded as such at the time.

Wartime press releases of the Allies were admitted as evidence by the prosecution, while those sought to be entered by the defense were excluded. The recollection of a conversation with a long-dead man was admitted. Letters allegedly written by Japanese citizens were admitted with no proof of authenticity and no opportunity for cross examination by the defense.

Defense

The defendants were represented by over a hundred attorneys, three-quarters of them Japanese and one-quarter American, plus a support staff. The defense opened its case on January 27, 1947, and finished its presentation 225 days later on September 9, 1947. The defense argued that the trial could never be free from substantial doubt as to its "legality, fairness and impartiality." The defense challenged the indictment, arguing that crimes against peace, and more specifically, the undefined concepts of conspiracy and aggressive war, had yet to be established as crimes ininternational law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

; in effect, the IMTFE was contradicting accepted legal procedure by trying the defendants retroactively for violating laws which had not existed when the alleged crimes had been committed. The defense insisted that there was no basis in international law for holding individuals responsible for acts of state, as the Tokyo Trial proposed to do. The defense attacked the notion of negative criminality, by which the defendants were to be tried for failing to prevent breaches of law and war crimes by others, as likewise having no basis in international law.

The defense argued that Allied Powers' violations of international law should be examined.

Former Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō

(10 December 1882 – 23 July 1950), was Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Empire of Japan at both the start and the end of the Axis–Allied conflict during World War II. He also served as Minister of Colonial Affairs in 1941, and assume ...

maintained that Japan had had no choice but to enter the war for self-defense purposes. He asserted that " ecause_of_the_Hull_Note.html"_;"title="Hull_Note.html"_;"title="ecause_of_the_Hull_Note">ecause_of_the_Hull_Note">Hull_Note.html"_;"title="ecause_of_the_Hull_Note">ecause_of_the_Hull_Notewe_felt_at_the_time_that_Japan_was_being_driven_either_to_war_or_suicide."

_Judgement

After_the_defense_had_finished_its_presentation_on_September_9,_1947_the_IMT_spent_fifteen_months_reaching_judgement_and_drafting_its_1,781-page_opinion._The_reading_of_the_judgement_and_the_sentences_lasted_from_December_4_to_12,_1948._Five_of_the_eleven_justices_released_separate_opinions_outside_the_court. In_his_concurring_opinion_Justice_ecause_of_the_Hull_Note.html"_;"title="Hull_Note.html"_;"title="ecause_of_the_Hull_Note">ecause_of_the_Hull_Note">Hull_Note.html"_;"title="ecause_of_the_Hull_Note">ecause_of_the_Hull_Notewe_felt_at_the_time_that_Japan_was_being_driven_either_to_war_or_suicide."

who accepted "ministerial and other advice for war" and that "no ruler can commit the crime of launching aggressive war and then validly claim to be excused for doing so because his life would otherwise have been in danger ... It will remain that the men who advised the commission of a crime, if it be one, are in no worse position than the man who directs the crime be committed."

Justice Delfín Jaranilla of the Philippines disagreed with the penalties imposed by the tribunal as being "too lenient, not exemplary and deterrent, and not commensurate with the gravity of the offence or offences committed."

Justice Henri Bernard of France argued that the tribunal's course of action was flawed due to Hirohito's absence and the lack of sufficient deliberation by the judges. He concluded that Japan's declaration of war "had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices" and that a "verdict reached by a Tribunal after a defective procedure cannot be a valid one."

"It is well-nigh impossible to define the concept of initiating or waging a war of aggression both accurately and comprehensively," wrote Justice _Judgement

After_the_defense_had_finished_its_presentation_on_September_9,_1947_the_IMT_spent_fifteen_months_reaching_judgement_and_drafting_its_1,781-page_opinion._The_reading_of_the_judgement_and_the_sentences_lasted_from_December_4_to_12,_1948._Five_of_the_eleven_justices_released_separate_opinions_outside_the_court. In_his_concurring_opinion_Justice_William_Webb_(judge)">William_Webb_of_Australia_took_issue_with_Emperor_Hirohito's_legal_status,_writing,_"The_suggestion_that_the_Emperor_was_bound_to_act_on_advice_is_contrary_to_the_evidence."_While_refraining_from_personal_indictment_of_Hirohito,_Webb_indicated_that_Hirohito_bore_responsibility_as_a_constitutional_monarchy.html" "title="William_Webb_(judge).html" ;"title="Hull_Note">ecause_of_the_Hull_Note.html" ;"title="Hull_Note.html" ;"title="ecause of the Hull Note">ecause of the Hull Note">Hull_Note.html" ;"title="ecause of the Hull Note">ecause of the Hull Notewe felt at the time that Japan was being driven either to war or suicide."Judgement

After the defense had finished its presentation on September 9, 1947 the IMT spent fifteen months reaching judgement and drafting its 1,781-page opinion. The reading of the judgement and the sentences lasted from December 4 to 12, 1948. Five of the eleven justices released separate opinions outside the court. In his concurring opinion Justice William Webb (judge)">William Webb of Australia took issue with Emperor Hirohito's legal status, writing, "The suggestion that the Emperor was bound to act on advice is contrary to the evidence." While refraining from personal indictment of Hirohito, Webb indicated that Hirohito bore responsibility as a constitutional monarchy">constitutional monarch A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...Bert Röling

Bernard Victor Aloysius "Bert" Röling (26 December 1906 – 16 March 1985) was a Dutch jurist and founding father of polemology in the Netherlands. Between 1946 and 1948 he acted as the Dutch representative for the International Military Tribu ...

of the Netherlands in his dissent. He stated, "I think that not only should there have been neutrals in the court, but there should have been Japanese also." He argued that they would always have been a minority and therefore would not have been able to sway the balance of the trial. However, "they could have convincingly argued issues of government policy which were unfamiliar to the Allied justices." Pointing out the difficulties and limitations in holding individuals responsible for an act of state and making omission of responsibility a crime, Röling called for the acquittal of several defendants, including Hirota.

Justice Radhabinod Pal

Radhabinod Pal (27 January 1886 – 10 January 1967) was an Indian jurist who was a member of the United Nations' International Law Commission from 1952 to 1966. He was one of three Asian judges appointed to the International Military Tribunal ...

of India produced a judgment in which he dismissed the legitimacy of the IMTFE as victor's justice

Victor's justice is a term used to refer to a distorted application of justice to the defeated by the victorious party following an armed conflict. Victor's justice generally involves excessive or unjustified punishment of defeated parties and l ...

: "I would hold that each and every one of the accused must be found not guilty of each and every one of the charges in the indictment and should be acquitted on all those charges." While taking into account the influence of wartime propaganda, exaggerations, and distortions of facts in the evidence, and "over-zealous" and "hostile" witnesses, Pal concluded, "The evidence is still overwhelming that atrocities were perpetrated by the members of the Japanese armed forces against the civilian population of some of the territories occupied by them as also against the prisoners of war."

Sentencing

One defendant,Shūmei Ōkawa

was a Japanese nationalist and Pan-Asianist writer, known for his publications on Japanese history, philosophy of religion, Indian philosophy, and colonialism.

Background

Ōkawa was born in Sakata, Yamagata, Japan in 1886. He graduated from ...

, was found mentally unfit for trial and the charges were dropped.

Two defendants, Yōsuke Matsuoka

was a Japanese diplomat and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Empire of Japan during the early stages of World War II. He is best known for his defiant speech at the League of Nations in February 1933, ending Japan's participation in the organ ...

and Osami Nagano

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of the leaders of Japan's military during most of the Second World War. In April 1941, he became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he served as the n ...

, died of natural causes during the trial.

Six defendants were sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace (Class A, Class B and Class C):

* General Kenji Doihara

was a Japanese army officer. As a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, he was instrumental in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

As a leading intelligence officer, he played a key role to the Japanese machinations that le ...

, chief of the intelligence services in Manchukuo

* Kōki Hirota

was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1936 to 1937. Originally his name was . He was executed for war crimes committed during the Second Sino-Japanese War at the Tokyo Trials.

Early life

Hirota was ...

, prime minister (later foreign minister)

* General Seishirō Itagaki

was a Japanese military officer and politician who served as a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II and War Minister from 1938 to 1939.

Itagaki was a main conspirator behind the Mukden Incident and held prestigious chief of ...

, war minister

* General Heitarō Kimura

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to death by hanging.

Biography

Kimura was born in Saitama prefecture, north of Tokyo, but was raised in Hiroshima prefecture, which he considered to be h ...

, commander, Burma Area Army

* Lieutenant General Akira Mutō

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. He was convicted of Japanese war crimes, war crimes and was executed by hanging. Mutō was implicated in both the Nanjing Massacre and the Manila massacre.

Biography

Mutō was a ...

, chief of staff, 14th Area Army

* General Hideki Tōjō

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

, commander, Kwantung Army (later prime minister)

One defendant was sentenced to death by hanging for war crimes and crimes against humanity (Class B and Class C):

* General Iwane Matsui

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and the commander of the expeditionary force sent to China in 1937. He was convicted of war crimes and executed by the Allies for his involvement in the Nanjing Massacre.

Born in Nagoya, Matsui chose ...

, commander, Shanghai Expeditionary Force and Central China Area Army

The seven defendants who were sentenced to death were executed at Sugamo Prison

Sugamo Prison (''Sugamo Kōchi-sho'', Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: ) was a prison in Tokyo, Japan. It was located in the district of Ikebukuro, which is now part of the Toshima ward of Tokyo, Japan.

History

Sugamo Prison was originally built in 1 ...

in Ikebukuro

is a commercial and entertainment district in Toshima, Tokyo, Japan. Toshima ward offices, Ikebukuro station, and several shops, restaurants, and enormous department stores are located within city limits. It is considered the second largest ...

on December 23, 1948. MacArthur, afraid of embarrassing and antagonizing the Japanese people, defied the wishes of President Truman and barred photography of any kind, instead bringing in four members of the Allied Council to act as official witnesses.

Sixteen defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment. Three (Koiso, Shiratori, and Umezu) died in prison, while the other thirteen were parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

d between 1954 and 1956:

* General Sadao Araki

Baron was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War II. As one of the principal nationalist right-wing political theorists in the Empire of Japan, he was regarded as the leader of the radical faction within the polit ...

, war minister

* Colonel Kingorō Hashimoto, major instigator of the second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

* Field Marshal Shunroku Hata

was a field marshal ('' gensui'') in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. He was the last surviving Japanese military officer with a marshal's rank. Hata was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1948, but was ...

, war minister

* Baron Kiichirō Hiranuma

Kiichirō, Kiichiro or Kiichirou (written: 麒一郎, 喜一郎 or 季一郎) is a masculine Japanese given name

A given name (also known as a forename or first name) is the part of a personal name quoted in that identifies a person, poten ...

, prime minister

* Naoki Hoshino

was a bureaucrat and politician who served in the Taishō period, Taishō and early Shōwa period Government of Japan, Japanese government, and as an official in the Manchukuo, Empire of Manchukuo.

Biography

Hoshino was born in Yokohama, where ...

, Chief Cabinet Secretary

* Okinori Kaya, Minister of Finance

* Marquis Kōichi Kido

Marquis (July 18, 1889 – April 6, 1977) was a Japanese statesman who served as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan from 1940 to 1945, and was the closest advisor to Emperor Hirohito throughout World War II. He was convicted of war crimes a ...

, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

* General Kuniaki Koiso

was a Japanese general in the Imperial Japanese Army, Governor-General of Korea and Prime Minister of Japan from 1944 to 1945.

After Japan's defeat in World War II, he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early lif ...

, governor-general of Korea, later prime minister

* General Jirō Minami

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and Governor-General of Korea between 1936 and 1942. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Life and military career

Born to an ex-''samurai'' family in Hiji, Ōita Prefe ...

, commander, Kwantung Army, former governor-general of Korea

* Vice Admiral Takazumi Oka, naval minister

* Lieutenant General Hiroshi Ōshima

Baron was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, Japanese ambassador to Germany before and during World War II and (unwittingly) a major source of communications intelligence for the Allies. His role was perhaps best summed up by General Geo ...

, Ambassador to Germany

* Lieutenant General Kenryō Satō, chief of the Military Affairs Bureau

* Admiral Shigetarō Shimada

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. He also served as Minister of the Navy. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early life and education

A native of Tokyo, Shimada graduated from t ...

, naval minister

* Toshio Shiratori

was the Japanese ambassador to Italy from 1938 to 1940, adviser to the Japanese foreign minister in 1940, and one of the 14 Class-A war criminals enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine.

Shiratori served as Director of Information Bureau under the F ...

, Ambassador to Italy

* Lieutenant General Teiichi Suzuki, president of the Cabinet Planning Board

* General Yoshijirō Umezu

(January 4, 1882 – January 8, 1949) was a Japanese general in World War II and Chief of the Army General Staff during the final years of the conflict. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Biography Early life a ...

, war minister and Chief of the Army General Staff

* Foreign minister Shigenori Tōgō

(10 December 1882 – 23 July 1950), was Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Empire of Japan at both the start and the end of the Axis–Allied conflict during World War II. He also served as Minister of Colonial Affairs in 1941, and assume ...

was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment. Togo died in prison in 1950.

* Foreign minister Mamoru Shigemitsu

was a Japanese diplomat and politician in the Empire of Japan, who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs three times during and after World War II as well as the Deputy Prime Minister of Japan. As civilian plenipotentiary representing the Ja ...

was sentenced to 7 years and paroled in 1950. He later served as Foreign Minister and as Deputy Prime Minister of post-war Japan.

The verdict and sentences of the tribunal were confirmed by MacArthur on November 24, 1948, two days after a perfunctory meeting with members of the Allied Control Commission for Japan, who acted as the local representatives of the nations of the Far Eastern Commission. Six of those representatives made no recommendations for clemency. Australia, Canada, India, and the Netherlands were willing to see the general make some reductions in sentences. He chose not to do so. The issue of clemency was thereafter to disturb Japanese relations with the Allied powers until the late 1950s, when a majority of the Allied powers agreed to release the last of the convicted major war criminals from captivity.Wilson, Sandra; Cribb, Robert; Trefalt, Beatrice; Aszkielowicz, Dean (2017). ''Japanese War Criminals: the Politics of Justice after the Second World War''. New York: Columbia University Press. .

Other war crimes trials

More than 5,700 lower-ranking personnel were charged with conventional war crimes in separate trials convened byAustralia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Netherlands Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. The charges covered a wide range of crimes including prisoner abuse, rape, sexual slavery, torture, ill-treatment of laborers, execution without trial, and inhumane medical experiments. The trials took place in around fifty locations in Asia and the Pacific. Most trials were completed by 1949, but Australia held some trials in 1951. China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

held 13 tribunals, resulting in 504 convictions and 149 executions.

Of the 5,700 Japanese individuals indicted for Class B war crimes, 984 were sentenced to death; 475 received life sentences; 2,944 were given more limited prison terms; 1,018 were acquitted; and 279 were never brought to trial or not sentenced. The number of death sentences by country is as follows: the Netherlands 236, United Kingdom 223, Australia 153, China 149, United States 140, France 26, and Philippines 17.

The Soviet Union and Chinese Communist forces also held trials of Japanese war criminals. The Khabarovsk War Crime Trials

The Khabarovsk war crimes trials were the Soviet hearings of twelve Japanese Kwantung Army officers and medical staff charged with the manufacture and use of biological weapons, and human experimentation, during World War II. The war crimes trial ...

held by the Soviets tried and found guilty some members of Japan's bacteriological and chemical warfare unit, also known as Unit 731

, short for Manshu Detachment 731 and also known as the Kamo Detachment and Ishii Unit, was a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that engaged in lethal human experimentatio ...

. However, those who surrendered to the Americans were never brought to trial. As Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milit ...

, MacArthur gave immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

to Shiro Ishii

Shiro, Shirō, Shirow or Shirou may refer to:

People

* Amakusa Shirō (1621–1638), leader of the Shimabara Rebellion

* Ken Shiro (born 1992), Japanese boxer

* Shiro Azumi, Japanese football player 1923–1925

* Shiro Ichinoseki (born 1944), ...

and all members of the bacteriological research units in exchange for germ warfare data based on human experimentation. On May 6, 1947, he wrote to Washington that "additional data, possibly some statements from Ishii probably can be obtained by informing Japanese involved that information will be retained in intelligence channels and will not be employed as 'War Crimes' evidence." The deal was concluded in 1948.

Criticism

Charges of victors' justice

The United States had provided the funds and staff necessary for running the Tribunal and also held the function of Chief Prosecutor. The argument was made that it was difficult, if not impossible, to uphold the requirement of impartiality with which such an organ should be invested. This apparent conflict gave the impression that the tribunal was no more than a means for the dispensation of victors' justice. Solis Horowitz argues that IMTFE had an American bias: unlike theNuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

, there was only a single prosecution team, led by an American, although the members of the tribunal represented eleven different Allied countries. The IMTFE had less official support than the Nuremberg trials. Keenan, a former U.S. assistant attorney general, had a much lower position than Nuremberg's Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Unit ...

, a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

.

Justice Jaranilla had been captured by the Japanese and walked the Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March (Filipino: ''Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan''; Spanish: ''Marcha de la muerte de Bataán'' ; Kapampangan: ''Martsa ning Kematayan quing Bataan''; Japanese: バターン死の行進, Hepburn: ''Batān Shi no Kōshin'') was ...

. The defense sought to remove him from the bench claiming he would be unable to maintain objectivity. The request was rejected but Jaranilla did excuse himself from presentation of evidence for atrocities in his native country of the Philippines.

Justice Radhabinod Pal argued that the exclusion of Western colonialism

The historical phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Turks, and the Arabs.

Colonialism in the modern sense began w ...

and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

from the list of crimes and the lack of judges from the vanquished nations on the bench signified the "failure of the Tribunal to provide anything other than the opportunity for the victors to retaliate"."The Tokyo Judgment and the Rape of Nanking", by Timothy Brook

Timothy James Brook (Chinese name: 卜正民; born January 6, 1951) is a Canadian historian, sinologist, and writer specializing in the study of China (sinology). He holds the Republic of China Chair, Department of History, University of British Co ...

, ''The Journal of Asian Studies'', August 2001. In this he was not alone among Indian jurists, with one prominent Calcutta barrister writing that the Tribunal was little more than "a sword in a udge'swig."

Justice Röling stated, " course, in Japan we were all aware of the bombings and the burnings of Tokyo and Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

and other big cities. It was horrible that we went there for the purpose of vindicating the laws of war, and yet saw every day how the Allies had violated them dreadfully."

However, in respect to Pal and Röling's statement about the conduct of air attacks, there was no positive

Positive is a property of positivity and may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Positive formula, a logical formula not containing negation

* Positive number, a number that is greater than 0

* Plus sign, the sign "+" used to indicate a posit ...

or specific customary

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a r ...

international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war (''jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by prot ...

with respect to aerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or strategic targets; fighter aircraft battling for control o ...

before and during World War II. Ben Bruce Blakeney

Ben Bruce Blakeney (July 30, 1908, Shawnee, Oklahoma – March 4, 1963) was an American lawyer who served with the rank of major during the Second World War in the Pacific War, Pacific theater. He is best known for his work for the defense at th ...

, an American defense counsel for Japanese defendants, argued that " the killing of Admiral Kidd by the bombing of Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Haw ...

is murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

, we know the name of the very man who ehands loosed the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

on Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

," although Pearl Harbor was classified as a war crime under the 1907 Hague Convention

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaty, treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions w ...

, as it happened without a declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state (polity), state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a nationa ...

and without a just cause for self-defense

Self-defense (self-defence primarily in Commonwealth English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm. The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of force in ...

. Prosecutors for Japanese war crimes once discussed prosecuting Japanese pilots involved in the bombing of Pearl Harbor for murder. However, they quickly dropped the idea after realizing there was no international law that protected neutral areas and nationals specifically from attack by aircraft.Article 39 of CHAPTER VI of the 1923 Hague Rules of Air Warfare stated:

:Belligerent aircraft are bound to respect the rights of neutral Powers and to abstain within the jurisdiction of a neutral State from the commission of any act which it is the duty of that State to prevent.

However, the Hague Rules of Air Warfare was never formally adopted by every major power, and therefore never legally binding as international law.

Similarly, the indiscriminate bombing of Chinese cities by Japanese Imperial forces was never raised in the Tokyo Trials in fear of America being accused of the same thing for its air attacks on Japanese cities. As a result, Japanese pilots and officers were not prosecuted for their aerial raids on Pearl Harbor and cities in China and other Asian countries.

Pal's dissenting opinion

Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the Uni ...

Radhabinod Pal

Radhabinod Pal (27 January 1886 – 10 January 1967) was an Indian jurist who was a member of the United Nations' International Law Commission from 1952 to 1966. He was one of three Asian judges appointed to the International Military Tribunal ...

raised substantive objections in a dissenting opinion: he found the entire prosecution case to be weak regarding the conspiracy to commit an act of aggressive war, which would include the brutalization and subjugation of conquered nations. About the Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Ba ...

—while acknowledging the brutality of the incident—he said that there was nothing to show that it was the "product of government policy" or that Japanese government officials were directly responsible. There is "no evidence, testimonial or circumstantial, concomitant, prospectant, restrospectant, that would in any way lead to the inference that the government in any way permitted the commission of such offenses," he said. In any case, he added, conspiracy to wage aggressive war was not illegal in 1937, or at any point since. In addition, Pal thought the refusal to try what he perceived as Allied crimes (particularly the use of atomic bombs) weakened the tribunal's authority. Recalling a letter by Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and List of monarchs of Prussia, King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication on 9 ...

signalling his determination to bring World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

to a swift conclusion through brutal means if necessary, Pal stated that "This policy of indiscriminate murder to shorten the war was considered to be a crime. In the Pacific war under our consideration, if there was anything approaching what is indicated in the above letter of the German Emperor, it is the decision coming from the Allied powers to use the bomb", adding that "Future generations will judge this dire decision". Pal was the only judge to argue for the acquittal of all of the defendants.

Exoneration of the imperial family

TheJapanese emperor

The Emperor of Japan is the monarch and the head of the Imperial Family of Japan. Under the Constitution of Japan, he is defined as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, and his position is derived from "the wi ...

Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

and other members of the imperial family might have been regarded as potential suspects. They included career officer Prince Yasuhiko Asaka

General was the founder of a collateral branch of the Japanese imperial family and a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during the Japanese invasion of China and the Second World War. Son-in-law of Emperor Meiji and uncle by marriage of Em ...

, Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu

was a scion of the Japanese imperial family and was a career naval officer who served as chief of staff of the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1932 to 1941.

Early life

Prince Hiroyasu was born in Tokyo as Prince Narukata, the eldest son of Princ ...

, Prince Higashikuni

General was a Japanese imperial prince, a career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and the 30th Prime Minister of Japan from 17 August 1945 to 9 October 1945, a period of 54 days. An uncle-in-law of Emperor Hirohito twice over, Prince H ...

, and Prince Takeda. Herbert Bix

Herbert P. Bix (born 1938) is an American historian. He wrote ''Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan'', an account of the Japanese Emperor and the events which shaped modern Japanese imperialism, which won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonficti ...

explained, "The Truman Administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been vice president for only days. A Democrat from Missouri, he ran fo ...

and General MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

both believed the occupation reforms would be implemented smoothly if they used Hirohito to legitimise their changes."

As early as November 26, 1945, MacArthur confirmed to Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai

was a Japanese general and politician. He served as admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Minister of the Navy, and Prime Minister of Japan in 1940.

Early life and career

Yonai was born on 2 March 1880, in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, the firs ...

that the emperor's abdication would not be necessary. Before the war crimes trials actually convened, SCAP, the International Prosecution Section (IPS), and court officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the imperial family from being indicted, but also to skew the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the emperor. High officials in court circles and the Japanese government collaborated with Allied GHQ in compiling lists of prospective war criminals. People arrested as Class A suspects and incarcerated in the Sugamo Prison

Sugamo Prison (''Sugamo Kōchi-sho'', Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: ) was a prison in Tokyo, Japan. It was located in the district of Ikebukuro, which is now part of the Toshima ward of Tokyo, Japan.

History

Sugamo Prison was originally built in 1 ...

solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility.

According to historian Herbert Bix

Herbert P. Bix (born 1938) is an American historian. He wrote ''Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan'', an account of the Japanese Emperor and the events which shaped modern Japanese imperialism, which won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonficti ...

, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers

Brigadier General Bonner Frank Fellers (February 7, 1896 – October 7, 1973) was a United States Army officer who served during World War II as a military attaché and director of psychological warfare. He is notable as the military attaché in ...

"immediately on landing in Japan went to work to protect Hirohito from the role he had played during and at the end of the war" and "allowed the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the emperor would be spared from indictment."

Bix also argues that "MacArthur's truly extraordinary measures to save Hirohito from trial as a war criminal had a lasting and profoundly distorting impact on Japanese understanding of the lost war" and "months before the Tokyo tribunal commenced, MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate responsibility for Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

to Hideki Tōjō

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

." According to a written report by Shūichi Mizota, Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai

was a Japanese general and politician. He served as admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Minister of the Navy, and Prime Minister of Japan in 1940.

Early life and career

Yonai was born on 2 March 1880, in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, the firs ...

's interpreter, Fellers met the two men at his office on March 6, 1946, and told Yonai, "It would be most convenient if the Japanese side could prove to us that the emperor is completely blameless. I think the forthcoming trials offer the best opportunity to do that. Tōjō, in particular, should be made to bear all responsibility at this trial."

Historian John W. Dower

John W. Dower (born June 21, 1938 in Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, Rhode Island) is an American author and historian. His 1999 book ''Embracing Defeat, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II'' won the U.S. National Book Awar ...

wrote that the campaign to absolve Emperor Hirohito of responsibility "knew no bounds." He argued that with MacArthur's full approval, the prosecution effectively acted as "a defense team for the emperor," who was presented as "an almost saintly figure" let alone someone culpable of war crimes. He stated, "Even Japanese activists who endorse the ideals of the Nuremberg and Tokyo charters and who have labored to document and publicize the atrocities of the Shōwa regime cannot defend the American decision to exonerate the emperor of war responsibility and then, in the chill of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, release and soon afterwards openly embrace accused right-winged war criminals like the later prime minister Nobusuke Kishi

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Shō ...

."

Three justices wrote an ''obiter dictum

''Obiter dictum'' (usually used in the plural, ''obiter dicta'') is a Latin phrase meaning "other things said",''Black's Law Dictionary'', p. 967 (5th ed. 1979). that is, a remark in a legal opinion that is "said in passing" by any judge or arbi ...

'' about the criminal responsibility of Hirohito. Judge-in-Chief Webb declared, "No ruler can commit the crime of launching aggressive war and then validly claim to be excused for doing so because his life would otherwise have been in danger ... It will remain that the men who advised the commission of a crime, if it be one, are in no worse position than the man who directs the crime be committed."

Justice Henri Bernard of France concluded that Japan's declaration of war "had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices."

Justice Röling did not find the emperor's immunity objectionable and further argued that five defendants (Kido, Hata, Hirota, Shigemitsu, and Tōgō) should have been acquitted.

Failure to prosecute for inhumane medical experimentation

Shirō Ishii

Surgeon General was a Japanese microbiologist and army medical officer who served as the director of Unit 731, a biological warfare unit of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Ishii led the development and application of biological weapons at Unit 73 ...

, commander of Unit 731

, short for Manshu Detachment 731 and also known as the Kamo Detachment and Ishii Unit, was a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that engaged in lethal human experimentatio ...

, received immunity in exchange for data gathered from his experiments on live prisoners. In 1981 John W. Powell published an article in the ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

The ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'' is a nonprofit organization concerning science and global security issues resulting from accelerating technological advances that have negative consequences for humanity. The ''Bulletin'' publishes conte ...

'' detailing the experiments of Unit 731 and its open-air tests of germ warfare on civilians. It was printed with a statement by Judge Röling, the last surviving member of the Tokyo Tribunal, who wrote, "As one of the judges in the International Military Tribunal, it is a bitter experience for me to be informed now that centrally ordered Japanese war criminality of the most disgusting kind was kept secret from the Court by the U.S. government".

Failure to prosecute other suspects

Forty-two suspects, such asNobusuke Kishi

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Shō ...

, who later became Prime Minister, and Yoshisuke Aikawa

was a Japanese entrepreneur, businessman, and politician, noteworthy as the founder and first president of the Nissan ''zaibatsu'' (1931–1945), one of Japan's most powerful business conglomerates around the time of the Second World War.

Biogr ...

, head of Nissan

, trade name, trading as Nissan Motor Corporation and often shortened to Nissan, is a Japanese multinational corporation, multinational Automotive industry, automobile manufacturer headquartered in Nishi-ku, Yokohama, Japan. The company sells ...

, were imprisoned in the expectation that they would be prosecuted at a second Tokyo Tribunal but they were never charged. They were released in 1947 and 1948.

Aftermath

Release of the remaining 42 "Class A" suspects

The International Prosecution Section (IPS) of the SCAP decided to try the seventy Japanese apprehended for "Class A" war crimes in three groups. The first group of 28 were major leaders in the military, political, and diplomatic sphere. The second group (23 people) and the third group (nineteen people) were industrial and financial magnates who had been engaged in weapons manufacturing industries or were accused of trafficking in narcotics, as well as a number of lesser known leaders in military, political, and diplomatic spheres. The most notable among these were: *Nobusuke Kishi

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Shō ...

: In charge of industry and commerce of Manchukuo, 1936–40; Minister of Industry and Commerce under Tojo administration.

* Fusanosuke Kuhara

was an entrepreneur, politician and cabinet minister in the pre-war Empire of Japan.

Biography

Kuhara was born in Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture into a family of ''sake'' brewers. His brother was the founder of Nippon Suisan Kaisha and his uncle Fu ...

: Leader of the pro-Zaibatsu

is a Japanese language, Japanese term referring to industrial and financial vertical integration, vertically integrated business conglomerate (company), conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed control over signi ...

faction of Rikken Seiyukai Rikken may refer to:

*Rikken Dōshikai, Japanese political party active in the early years of the 20th century

*Rikken Kaishintō, political party in Meiji period Japan

*Rikken Kokumintō, political party in Meiji period Japan

*Rikken Minseito, one ...

.

* Yoshisuke Ayukawa

was a Japanese entrepreneur, businessman, and politician, noteworthy as the founder and first president of the Nissan ''zaibatsu'' (1931–1945), one of Japan's most powerful business conglomerates around the time of the Second World War.

Biog ...

: Sworn brother of Fusanosuke Kuhara, founder of Japan Industrial Corporation; went to Manchuria after the Mukden Incident

The Mukden Incident, or Manchurian Incident, known in Chinese as the 9.18 Incident (九・一八), was a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

On September 18, 1931, L ...

(1931), at the invitation of his relative Nobusuke Kishi, where he founded the Manchurian Heavy Industry Development Company.

* Toshizō Nishio

was a Japanese general, considered to be one of the Imperial Japanese Army's most successful and ablest strategists during the Second Sino-Japanese War, who commanded the Japanese Second Army during the first years after the Marco Polo Bridge In ...

: Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army, Commander-in-Chief of China Expeditionary Army, 1939–41; war-time Minister of Education.

* Kisaburō Andō

was a career officer and lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army, who served as a politician and cabinet minister in the government of the Empire of Japan during World War II.

Life and military career

Born to an ex-''samurai'' family o ...

: Garrison Commander of Port Arthur and Minister of Interior in the Tojo cabinet.

* Yoshio Kodama

was a Japanese right-wing ultranationalist and a prominent figure in the rise of organized crime in Japan. The most famous '' kuromaku'', or behind-the-scenes power broker, of the 20th century, he was active in Japan's political arena and crimi ...

: A radical ultranationalist. War profiteer, smuggler and underground crime boss.

* Ryōichi Sasakawa

was a Japanese suspected war criminal, businessman, far-right politician, and philanthropist. He was born in Minoh, Osaka. In the 1930s and during the Second World War he was active both in finance and in politics, actively supporting the Japane ...

: Ultranationalist businessman and philanthropist.

* Kazuo Aoki: Administrator of Manchurian affairs; Minister of Treasury in Nobuyoki Abe's cabinet; followed Abe to China as an advisor; Minister of Greater East Asia in the Tojo cabinet.

* Masayuki Tani

(2 September 1889 – 16 October 1962) was a Japanese diplomat and politician who was briefly foreign minister of Japan from September 1942 to 21 April 1943 during World War II.

Career

Tani was a career diplomat before assuming minis ...

: Ambassador to Manchukuo, Minister of Foreign Affairs and concurrently Director of the Intelligence Bureau; Ambassador to the Reorganized National Government of China

The Wang Jingwei regime or the Wang Ching-wei regime is the common name of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China ( zh , t = 中華民國國民政府 , p = Zhōnghuá Mínguó Guómín Zhèngfǔ ), the government of the pup ...

.

* Eiji Amo: Chief of the Intelligence Section of Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs; Director of Intelligence Bureau in the Tojo cabinet.

* Yakichiro Suma: Consul General at Nanking; in 1938, he served as counselor at the Japanese Embassy in Washington; after 1941, Minister Plenipotentiary to Spain.

All remaining people apprehended and accused of Class A war crimes who had not yet come to trial were set free by MacArthur in 1947 and 1948.

San Francisco Peace Treaty

Under Article 11 of theSan Francisco Peace Treaty

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

, signed on September 8, 1951, Japan accepted the jurisdiction of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Article 11 of the treaty reads:

Parole for war criminals movement