To Mars By A-Bomb (film) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Project Orion was a study conducted between the 1950s and 1960s by the

Project Orion was a study conducted between the 1950s and 1960s by the

The Orion nuclear pulse drive combines a very high exhaust velocity, from 19 to 31 km/s (12 to 19 mi/s) in typical interplanetary designs, with

The Orion nuclear pulse drive combines a very high exhaust velocity, from 19 to 31 km/s (12 to 19 mi/s) in typical interplanetary designs, with

In late 1958 to early 1959, it was realized that the smallest practical vehicle would be determined by the smallest achievable bomb yield. The use of 0.03 kt (sea-level yield) bombs would give vehicle mass of 880 tons. However, this was regarded as too small for anything other than an orbital test vehicle and the team soon focused on a 4,000 ton "base design".

At that time, the details of small bomb designs were shrouded in secrecy. Many Orion design reports had all details of bombs removed before release. Contrast the above details with the 1959 report by General Atomics, which explored the parameters of three different sizes of

In late 1958 to early 1959, it was realized that the smallest practical vehicle would be determined by the smallest achievable bomb yield. The use of 0.03 kt (sea-level yield) bombs would give vehicle mass of 880 tons. However, this was regarded as too small for anything other than an orbital test vehicle and the team soon focused on a 4,000 ton "base design".

At that time, the details of small bomb designs were shrouded in secrecy. Many Orion design reports had all details of bombs removed before release. Contrast the above details with the 1959 report by General Atomics, which explored the parameters of three different sizes of

A concept similar to Orion was designed by the

A concept similar to Orion was designed by the

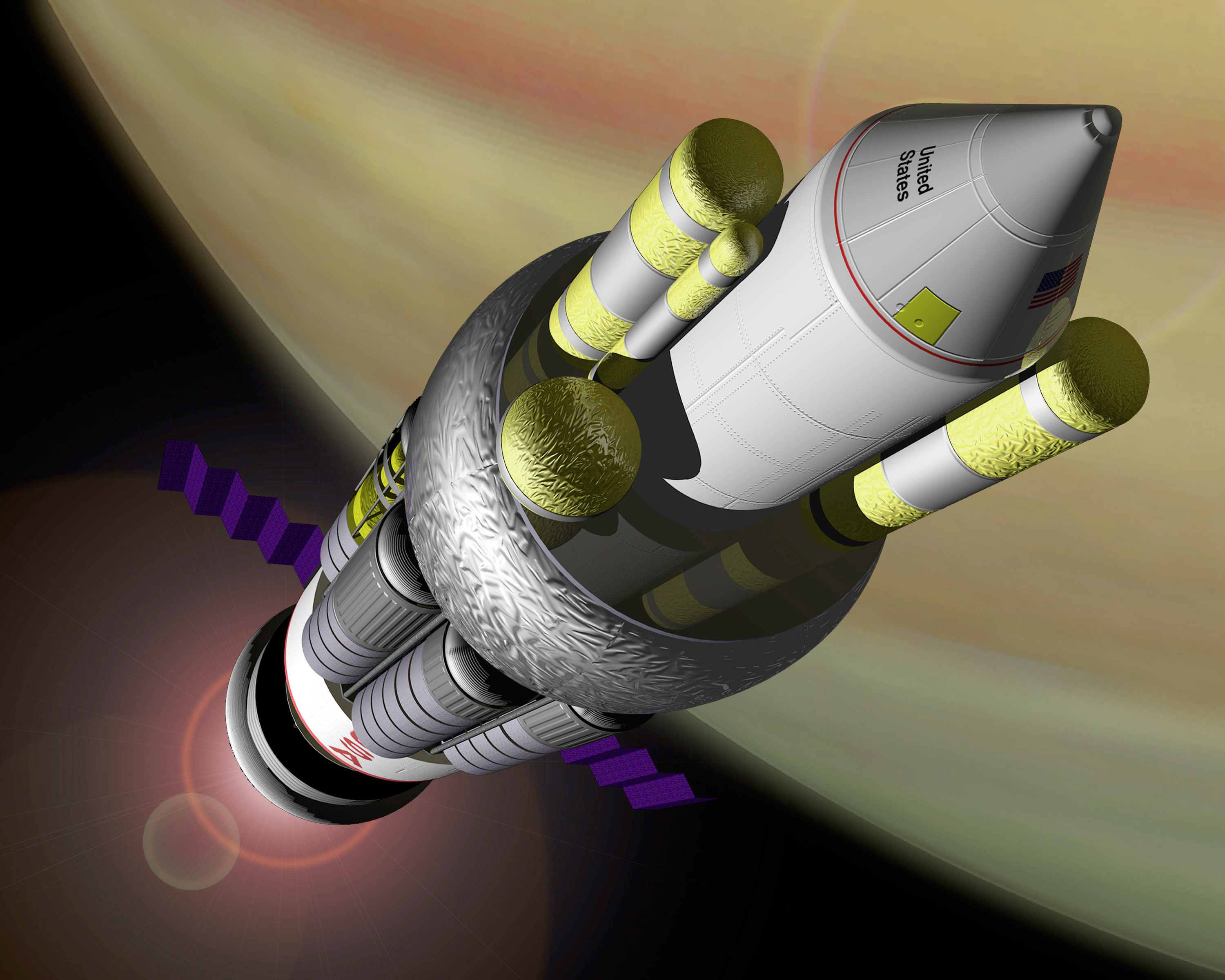

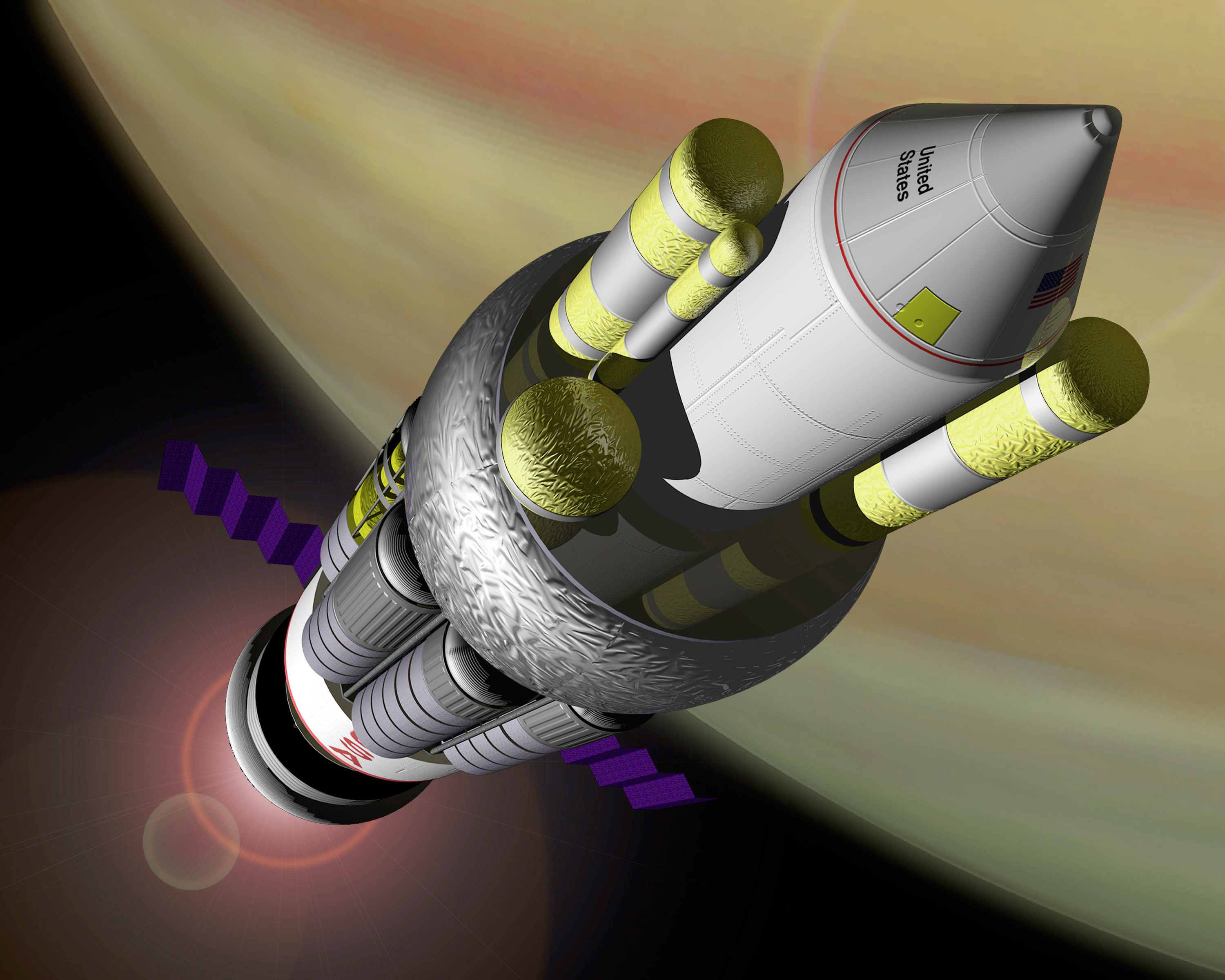

From 1957 to 1964 this information was used to design a spacecraft propulsion system called Orion, in which nuclear explosives would be thrown behind a pusher-plate mounted on the bottom of a spacecraft and exploded. The shock wave and radiation from the detonation would impact against the underside of the pusher plate, giving it a powerful push. The pusher plate would be mounted on large two-stage

From 1957 to 1964 this information was used to design a spacecraft propulsion system called Orion, in which nuclear explosives would be thrown behind a pusher-plate mounted on the bottom of a spacecraft and exploded. The shock wave and radiation from the detonation would impact against the underside of the pusher plate, giving it a powerful push. The pusher plate would be mounted on large two-stage  A preliminary design for a nuclear pulse unit was produced. It proposed the use of a shaped-charge fusion-boosted fission explosive. The explosive was wrapped in a

A preliminary design for a nuclear pulse unit was produced. It proposed the use of a shaped-charge fusion-boosted fission explosive. The explosive was wrapped in a

''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume I -- Summary''

September 19, 1964 *General Atomics

''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume III -- Conceptual Vehicle Designs And Operational Systems''

September 19, 1964 *General Atomics

''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume IV -- Mission Velocity Requirements And System Comparisons''

February 28, 1966 *General Atomics

''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume IV -- Mission Velocity Requirements And System Comparisons (Supplement)''

February 28, 1966 * *NASA

''Nuclear Pulse Vehicle Study Condensed Summary Report (General Dynamics Corp)''

January 14, 1964

Freeman Dyson talking about Project OrionElectromagnetic Pulse Shockwaves as a result of Nuclear Pulse PropulsionGeorge Dyson talking about Project Orion

at

Project Orion was a study conducted between the 1950s and 1960s by the

Project Orion was a study conducted between the 1950s and 1960s by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

, DARPA

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is a research and development agency of the United States Department of Defense responsible for the development of emerging technologies for use by the military.

Originally known as the Adv ...

, and NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

for the purpose of identifying the efficacy of a starship

A starship, starcraft, or interstellar spacecraft is a theoretical spacecraft designed for interstellar travel, traveling between planetary systems.

The term is mostly found in science fiction. Reference to a "star-ship" appears as early as 188 ...

directly propelled by a series of explosions of atomic bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

behind the craft—nuclear pulse propulsion

Nuclear pulse propulsion or external pulsed plasma propulsion is a hypothetical method of spacecraft propulsion that uses nuclear explosions for thrust. It originated as Project ''Orion'' with support from DARPA, after a suggestion by Stanislaw ...

. Early versions of this vehicle were proposed to take off from the ground; later versions were presented for use only in space. Six non-nuclear tests were conducted using models. The project was eventually abandoned for multiple reasons, including the Partial Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all nuclear weapons testing, test detonations of nuclear weapons exce ...

, which banned nuclear explosions in space, and concerns over nuclear fallout.

The idea of rocket propulsion by combustion of explosive substance was first proposed by Russian explosives expert Nikolai Kibalchich

Nikolai Ivanovich Kibalchich (russian: Николай Иванович Кибальчич, uk, Микола Іванович Кибальчич, sr, Никола Кибалчић, ''Mykola Ivanovych Kybalchych''; 19 October 1853 – April 3, 188 ...

in 1881, and in 1891 similar ideas were developed independently by German engineer Hermann Ganswindt. Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

mentions powering spaceships with nuclear bombs in his 1940 short story "Blowups Happen

"Blowups Happen" is a 1940 science fiction short story by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. It is one of two stories in which Heinlein, using only public knowledge of nuclear fission, anticipated the actual development of nuclear technology a few ...

". Real life proposals of nuclear propulsion were first made by Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

in 1946, and preliminary calculations were made by F. Reines and Ulam in a Los Alamos memorandum dated 1947. The actual project, initiated in 1958, was led by Ted Taylor at General Atomics

General Atomics is an American energy and defense corporation headquartered in San Diego, California, specializing in research and technology development. This includes physics research in support of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion energy. The ...

and physicist Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

, who at Taylor's request took a year away from the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholar ...

in Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

to work on the project.

The Orion concept offered high thrust and high specific impulse

Specific impulse (usually abbreviated ) is a measure of how efficiently a reaction mass engine (a rocket using propellant or a jet engine using fuel) creates thrust. For engines whose reaction mass is only the fuel they carry, specific impulse i ...

, or propellant efficiency, at the same time. The unprecedented extreme power requirements for doing so would be met by nuclear explosions, of such power relative to the vehicle's mass as to be survived only by using external detonations without attempting to contain them in internal structures. As a qualitative comparison, traditional chemical rockets—such as the Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

that took the Apollo program to the Moon—produce high thrust with low specific impulse, whereas electric ion engine

An ion thruster, ion drive, or ion engine is a form of electric propulsion used for spacecraft propulsion. It creates thrust by accelerating ions using electricity.

An ion thruster ionizes a neutral gas by extracting some electrons out of ...

s produce a small amount of thrust very efficiently. Orion would have offered performance greater than the most advanced conventional or nuclear rocket engines then under consideration. Supporters of Project Orion felt that it had potential for cheap interplanetary travel

Interplanetary spaceflight or interplanetary travel is the crewed or uncrewed travel between stars and planets, usually within a single planetary system. In practice, spaceflights of this type are confined to travel between the planets of th ...

, but it lost political approval over concerns about fallout from its propulsion.Sagan, Carl; Druyan, Ann; Tyson, Neil deGrasse (2013). ''Cosmos''. New York: Ballantine Books. .

The Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963 is generally acknowledged to have ended the project. However, from Project Longshot

Project Longshot was a conceptual interstellar spacecraft design. It would have been an uncrewed starship (about 400 tonnes), intended to fly to and enter orbit around Alpha Centauri B powered by nuclear pulse propulsion.

History

Developed ...

to Project Daedalus

Project Daedalus (named after Daedalus, the Greek mythological designer who crafted wings for human flight) was a study conducted between 1973 and 1978 by the British Interplanetary Society to design a plausible uncrewed interstellar probe.Pro ...

, Mini-Mag Orion

Mini-Mag Orion (MMO), or Miniature Magnetic Orion, is a proposed type of spacecraft propulsion based on the Project Orion nuclear propulsion system. The Mini-Mag Orion system achieves propulsion by compressing fissile material in a magnetic fiel ...

, and other proposals which reach engineering analysis at the level of considering thermal power dissipation, the principle of external nuclear pulse propulsion

Nuclear pulse propulsion or external pulsed plasma propulsion is a hypothetical method of spacecraft propulsion that uses nuclear explosions for thrust. It originated as Project ''Orion'' with support from DARPA, after a suggestion by Stanislaw ...

to maximize survivable power has remained common among serious concepts for interstellar flight without external power beaming and for very high-performance interplanetary flight. Such later proposals have tended to modify the basic principle by envisioning equipment driving detonation of much smaller fission or fusion pellets, in contrast to Project Orion's larger nuclear pulse units (full nuclear bombs) based on less speculative technology.

Basic principles

The Orion nuclear pulse drive combines a very high exhaust velocity, from 19 to 31 km/s (12 to 19 mi/s) in typical interplanetary designs, with

The Orion nuclear pulse drive combines a very high exhaust velocity, from 19 to 31 km/s (12 to 19 mi/s) in typical interplanetary designs, with meganewton

The newton (symbol: N) is the unit of force in the International System of Units (SI). It is defined as 1 kg⋅m/s, the force which gives a mass of 1 kilogram an acceleration of 1 metre per second per second. It is named after Isaac Newton in r ...

s of thrust. Many spacecraft propulsion drives can achieve one of these or the other, but nuclear pulse rockets are the only proposed technology that could potentially meet the extreme power requirements to deliver both at once (see spacecraft propulsion

Spacecraft propulsion is any method used to accelerate spacecraft and artificial satellites. In-space propulsion exclusively deals with propulsion systems used in the vacuum of space and should not be confused with space launch or atmospheric e ...

for more speculative systems).

Specific impulse

Specific impulse (usually abbreviated ) is a measure of how efficiently a reaction mass engine (a rocket using propellant or a jet engine using fuel) creates thrust. For engines whose reaction mass is only the fuel they carry, specific impulse i ...

(''I''sp) measures how much thrust can be derived from a given mass of fuel, and is a standard figure of merit for rocketry. For any rocket propulsion, since the kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Having gained this energy during its accele ...

of exhaust goes up with velocity squared (kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Having gained this energy during its accele ...

= ½ mv2), whereas the momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass an ...

and thrust go up with velocity linearly (momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass an ...

= mv), obtaining a particular level of thrust (as in a number of g acceleration) requires far more power each time that exhaust velocity and ''I''sp are much increased in a design goal. (For instance, the most fundamental reason that current and proposed electric propulsion

Spacecraft electric propulsion (or just electric propulsion) is a type of spacecraft propulsion technique that uses electrostatic or electromagnetic fields to accelerate mass to high speed and thus generate thrust to modify the velocity of a sp ...

systems of high ''I''sp tend to be low thrust is due to their limits on available power. Their thrust is actually inversely proportional to ''I''sp if power going into exhaust is constant or at its limit from heat dissipation needs or other engineering constraints.) The Orion concept detonates nuclear explosions externally at a rate of power release which is beyond what nuclear reactors could survive internally with known materials and design.

Since weight is no limitation, an Orion craft can be extremely robust. An uncrewed craft could tolerate very large accelerations, perhaps 100 ''g''. A human-crewed Orion, however, must use some sort of damping system behind the pusher plate to smooth the near instantaneous acceleration to a level that humans can comfortably withstand – typically about 2 to 4 ''g''.

The high performance depends on the high exhaust velocity, in order to maximize the rocket's force for a given mass of propellant. The velocity of the plasma debris is proportional to the square root of the change in the temperature (''Tc'') of the nuclear fireball. Since such fireballs typically achieve ten million degrees Celsius or more in less than a millisecond, they create very high velocities. However, a practical design must also limit the destructive radius of the fireball. The diameter of the nuclear fireball is proportional to the square root of the bomb's explosive yield.

The shape of the bomb's reaction mass is critical to efficiency. The original project designed bombs with a reaction mass made of tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isolat ...

. The bomb's geometry and materials focused the X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

s and plasma from the core of nuclear explosive to hit the reaction mass. In effect each bomb would be a nuclear shaped charge

A shaped charge is an explosive charge shaped to form an explosively formed penetrator (EFP) to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ini ...

.

A bomb with a cylinder of reaction mass expands into a flat, disk-shaped wave of plasma when it explodes. A bomb with a disk-shaped reaction mass expands into a far more efficient cigar-shaped wave of plasma debris. The cigar shape focuses much of the plasma to impinge onto the pusher-plate. For greatest mission efficiency the rocket equation

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

demands that the greatest fraction of the bomb's explosive force be directed at the spacecraft, rather than being spent isotropically.

The maximum effective specific impulse, ''Isp'', of an Orion nuclear pulse drive generally is equal to:

:

where ''C0'' is the collimation factor (what fraction of the explosion plasma debris will actually hit the impulse absorber plate when a pulse unit explodes), ''Ve'' is the nuclear pulse unit plasma debris velocity, and ''gn'' is the standard acceleration of gravity (9.81 m/s2; this factor is not necessary if ''Isp'' is measured in N·s/kg or m/s). A collimation factor of nearly 0.5 can be achieved by matching the diameter of the pusher plate to the diameter of the nuclear fireball created by the explosion of a nuclear pulse unit.

The smaller the bomb, the smaller each impulse will be, so the higher the rate of impulses and more than will be needed to achieve orbit. Smaller impulses also mean less ''g'' shock on the pusher plate and less need for damping to smooth out the acceleration.

The optimal Orion drive bomblet yield (for the human crewed 4,000 ton reference design) was calculated to be in the region of 0.15 kt, with approx 800 bombs needed to orbit and a bomb rate of approx 1 per second.

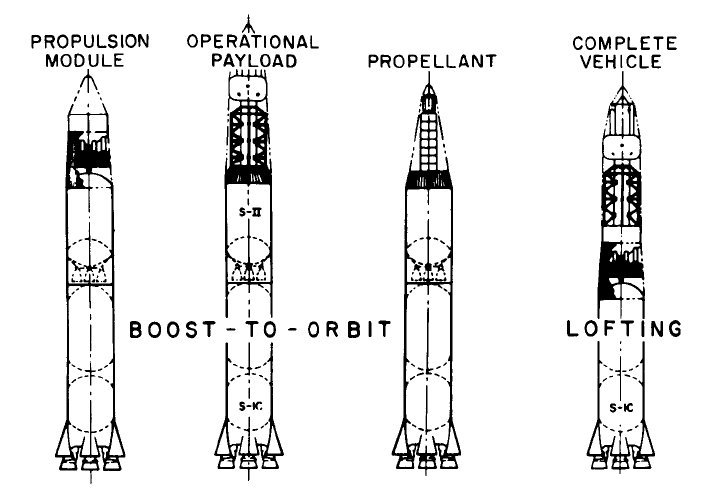

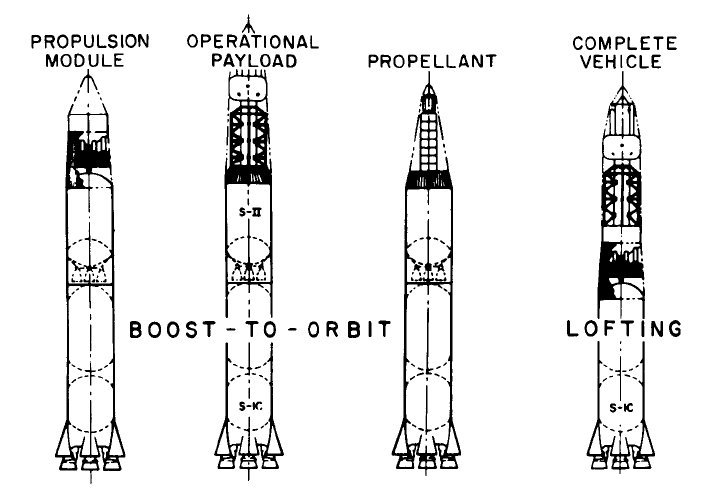

Sizes of vehicles

The following can be found in George Dyson's book. The figures for the comparison with Saturn V are taken from this section and converted from metric (kg) to USshort ton

The short ton (symbol tn) is a measurement unit equal to . It is commonly used in the United States, where it is known simply as a ton,

although the term is ambiguous, the single word being variously used for short, long, and metric ton.

The vari ...

s (abbreviated "t" here).

In late 1958 to early 1959, it was realized that the smallest practical vehicle would be determined by the smallest achievable bomb yield. The use of 0.03 kt (sea-level yield) bombs would give vehicle mass of 880 tons. However, this was regarded as too small for anything other than an orbital test vehicle and the team soon focused on a 4,000 ton "base design".

At that time, the details of small bomb designs were shrouded in secrecy. Many Orion design reports had all details of bombs removed before release. Contrast the above details with the 1959 report by General Atomics, which explored the parameters of three different sizes of

In late 1958 to early 1959, it was realized that the smallest practical vehicle would be determined by the smallest achievable bomb yield. The use of 0.03 kt (sea-level yield) bombs would give vehicle mass of 880 tons. However, this was regarded as too small for anything other than an orbital test vehicle and the team soon focused on a 4,000 ton "base design".

At that time, the details of small bomb designs were shrouded in secrecy. Many Orion design reports had all details of bombs removed before release. Contrast the above details with the 1959 report by General Atomics, which explored the parameters of three different sizes of hypothetical

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obser ...

Orion spacecraft:

The biggest design above is the "super" Orion design; at 8 million tonnes, it could easily be a city. In interviews, the designers contemplated the large ship as a possible interstellar ark

An interstellar ark is a conceptual starship designed for interstellar travel. Interstellar arks may be the most economically feasible method of traveling such distances. The ark has also been proposed as a potential habitat to preserve civiliza ...

. This extreme design could be built with materials and techniques that could be obtained in 1958 or were anticipated to be available shortly after.

Most of the three thousand tonnes of each of the "super" Orion's propulsion units would be inert material such as polyethylene

Polyethylene or polythene (abbreviated PE; IUPAC name polyethene or poly(methylene)) is the most commonly produced plastic. It is a polymer, primarily used for packaging ( plastic bags, plastic films, geomembranes and containers including bo ...

, or boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the ''boron group'' it has th ...

salts, used to transmit the force of the propulsion units detonation to the Orion's pusher plate, and absorb neutrons to minimize fallout. One design proposed by Freeman Dyson for the "Super Orion" called for the pusher plate to be composed primarily of uranium or a transuranic element

The transuranium elements (also known as transuranic elements) are the chemical elements with atomic numbers greater than 92, which is the atomic number of uranium. All of these elements are unstable and decay radioactively into other elements. ...

so that upon reaching a nearby star system the plate could be converted to nuclear fuel.

Theoretical applications

The Orion nuclear pulse rocket design has extremely high performance. Orion nuclear pulse rockets using nuclear fission type pulse units were originally intended for use on interplanetary space flights. Missions that were designed for an Orion vehicle in the original project included single stage (i.e., directly from Earth's surface) to Mars and back, and a trip to one of the moons of Saturn. Freeman Dyson performed the first analysis of what kinds of Orion missions were possible to reach Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system to theSun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

. His 1968 paper "Interstellar Transport" (''Physics Today

''Physics Today'' is the membership magazine of the American Institute of Physics. First published in May 1948, it is issued on a monthly schedule, and is provided to the members of ten physics societies, including the American Physical Society. I ...

'', October 1968, pp. 41–45) retained the concept of large nuclear explosions but Dyson moved away from the use of fission bombs and considered the use of one megaton deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

fusion explosions instead. His conclusions were simple: the debris velocity of fusion explosions was probably in the 3000–30,000 km/s range and the reflecting geometry of Orion's hemispherical pusher plate would reduce that range to 750–15,000 km/s.

To estimate the upper and lower limits of what could be done using contemporary technology (in 1968), Dyson considered two starship designs. The more conservative ''energy limited'' pusher plate design simply had to absorb all the thermal energy of each impinging explosion (4×1015 joules, half of which would be absorbed by the pusher plate) without melting. Dyson estimated that if the exposed surface consisted of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

with a thickness of 1 mm, then the diameter and mass of the hemispherical pusher plate would have to be 20 kilometers and 5 million tonnes, respectively. 100 seconds would be required to allow the copper to radiatively cool before the next explosion. It would then take on the order of 1000 years for the energy-limited heat sink

A heat sink (also commonly spelled heatsink) is a passive heat exchanger that transfers the heat generated by an electronic or a mechanical device to a fluid medium, often air or a liquid coolant, where it is dissipated away from the device, th ...

Orion design to reach Alpha Centauri.

In order to improve on this performance while reducing size and cost, Dyson also considered an alternative ''momentum limited'' pusher plate design where an ablation coating of the exposed surface is substituted to get rid of the excess heat. The limitation is then set by the capacity of shock absorbers to transfer momentum from the impulsively accelerated pusher plate to the smoothly accelerated vehicle. Dyson calculated that the properties of available materials limited the velocity transferred by each explosion to ~30 meters per second independent of the size and nature of the explosion. If the vehicle is to be accelerated at 1 Earth gravity (9.81 m/s2) with this velocity transfer, then the pulse rate is one explosion every three seconds. The dimensions and performance of Dyson's vehicles are given in the following table:

Later studies indicate that the top cruise velocity that can theoretically be achieved are a few percent of the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. The speed of light is exactly equal to ). According to the special theory of relativity, is the upper limit ...

(0.08–0.1c).Cosmos by Carl Sagan An atomic (fission) Orion can achieve perhaps 9%–11% of the speed of light. A nuclear pulse drive starship powered by fusion-antimatter catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion

Antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion (also antiproton-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion) is a variation of nuclear pulse propulsion based upon the injection of antimatter into a mass of nuclear fuel to initiate a nuclear chain reaction fo ...

units would be similarly in the 10% range and pure Matter-antimatter annihilation rockets would be theoretically capable of obtaining a velocity between 50% to 80% of the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. The speed of light is exactly equal to ). According to the special theory of relativity, is the upper limit ...

. In each case saving fuel for slowing down halves the maximum speed. The concept of using a magnetic sail

A magnetic sail is a proposed method of spacecraft propulsion that uses a static magnetic field to deflect a plasma wind of charged particles radiated by the Sun or a Star thereby transferring momentum to accelerate or decelerate a spacecraft. ...

to decelerate the spacecraft as it approaches its destination has been discussed as an alternative to using propellant; this would allow the ship to travel near the maximum theoretical velocity.

At 0.1''c'', Orion thermonuclear starships would require a flight time of at least 44 years to reach Alpha Centauri, not counting time needed to reach that speed (about 36 days at constant acceleration of 1''g'' or 9.8 m/s2). At 0.1''c'', an Orion starship would require 100 years to travel 10 light years. The astronomer Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on ext ...

suggested that this would be an excellent use for current stockpiles of nuclear weapons.

As part of the development of Project Orion, to garner funding from the military, a derived "space battleship" space-based nuclear-blast-hardened nuclear-missile weapons platform was mooted in the 1960s by the United States Air Force. It would comprise the USAF "Deep Space Bombardment Force".

Later developments

A concept similar to Orion was designed by the

A concept similar to Orion was designed by the British Interplanetary Society

The British Interplanetary Society (BIS), founded in Liverpool in 1933 by Philip E. Cleator, is the oldest existing space advocacy organisation in the world. Its aim is exclusively to support and promote astronautics and space exploration.

Str ...

(B.I.S.) in the years 1973–1974. Project Daedalus

Project Daedalus (named after Daedalus, the Greek mythological designer who crafted wings for human flight) was a study conducted between 1973 and 1978 by the British Interplanetary Society to design a plausible uncrewed interstellar probe.Pro ...

was to be a robotic interstellar probe to Barnard's Star

Barnard's Star is a red dwarf about six light-years from Earth in the constellation of Ophiuchus. It is the fourth-nearest-known individual star to the Sun after the three components of the Alpha Centauri system, and the closest star in t ...

that would travel at 12% of the speed of light. In 1989, a similar concept was studied by the U.S. Navy and NASA in Project Longshot

Project Longshot was a conceptual interstellar spacecraft design. It would have been an uncrewed starship (about 400 tonnes), intended to fly to and enter orbit around Alpha Centauri B powered by nuclear pulse propulsion.

History

Developed ...

. Both of these concepts require significant advances in fusion technology, and therefore cannot be built at present, unlike Orion.

From 1998 to the present, the nuclear engineering department at Pennsylvania State University has been developing two improved versions of project Orion known as Project ICAN and Project AIMStar using compact antimatter catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion

Antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion (also antiproton-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion) is a variation of nuclear pulse propulsion based upon the injection of antimatter into a mass of nuclear fuel to initiate a nuclear chain reaction fo ...

units, rather than the large inertial confinement fusion

Inertial confinement fusion (ICF) is a fusion energy process that initiates nuclear fusion reactions by compressing and heating targets filled with thermonuclear fuel. In modern machines, the targets are small spherical pellets about the size of ...

ignition systems proposed in Project Daedalus and Longshot.

Costs

The expense of the fissionable materials required was thought to be high, until the physicist Ted Taylor showed that with the right designs for explosives, the amount of fissionables used on launch was close to constant for every size of Orion from 2,000 tons to 8,000,000 tons. The larger bombs used more explosives to super-compress the fissionables, increasing efficiency. The extra debris from the explosives also serves as additional propulsion mass. The bulk of costs for historical nuclear defense programs have been for delivery and support systems, rather than for production cost of the bombs directly (with warheads being 7% of the U.S. 1946–1996 expense total according to one study). After initial infrastructure development and investment, the marginal cost of additional nuclear bombs in mass production can be relatively low. In the 1980s, some U.S. thermonuclear warheads had $1.1 million estimated cost each ($630 million for 560). For the perhaps simpler fission pulse units to be used by one Orion design, a 1964 source estimated a cost of $40000 or less each in mass production, which would be up to approximately $0.3 million each in modern-day dollars adjusted for inflation.Project Daedalus

Project Daedalus (named after Daedalus, the Greek mythological designer who crafted wings for human flight) was a study conducted between 1973 and 1978 by the British Interplanetary Society to design a plausible uncrewed interstellar probe.Pro ...

later proposed fusion explosives (deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

or tritium

Tritium ( or , ) or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with half-life about 12 years. The nucleus of tritium (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus o ...

pellets) detonated by electron beam inertial confinement. This is the same principle behind inertial confinement fusion

Inertial confinement fusion (ICF) is a fusion energy process that initiates nuclear fusion reactions by compressing and heating targets filled with thermonuclear fuel. In modern machines, the targets are small spherical pellets about the size of ...

. Theoretically, it could be scaled down to far smaller explosions, and require small shock absorbers.

Vehicle architecture

From 1957 to 1964 this information was used to design a spacecraft propulsion system called Orion, in which nuclear explosives would be thrown behind a pusher-plate mounted on the bottom of a spacecraft and exploded. The shock wave and radiation from the detonation would impact against the underside of the pusher plate, giving it a powerful push. The pusher plate would be mounted on large two-stage

From 1957 to 1964 this information was used to design a spacecraft propulsion system called Orion, in which nuclear explosives would be thrown behind a pusher-plate mounted on the bottom of a spacecraft and exploded. The shock wave and radiation from the detonation would impact against the underside of the pusher plate, giving it a powerful push. The pusher plate would be mounted on large two-stage shock absorber

A shock absorber or damper is a mechanical or hydraulic device designed to absorb and damp shock impulses. It does this by converting the kinetic energy of the shock into another form of energy (typically heat) which is then dissipated. Most sh ...

s that would smoothly transmit acceleration to the rest of the spacecraft.

During take-off, there were concerns of danger from fluidic shrapnel being reflected from the ground. One proposed solution was to use a flat plate of conventional explosives spread over the pusher plate, and detonate this to lift the ship from the ground before going nuclear. This would lift the ship far enough into the air that the first focused nuclear blast would not create debris capable of harming the ship.

A preliminary design for a nuclear pulse unit was produced. It proposed the use of a shaped-charge fusion-boosted fission explosive. The explosive was wrapped in a

A preliminary design for a nuclear pulse unit was produced. It proposed the use of a shaped-charge fusion-boosted fission explosive. The explosive was wrapped in a beryllium oxide

Beryllium oxide (BeO), also known as beryllia, is an inorganic compound with the formula BeO. This colourless solid is a notable electrical insulator with a higher thermal conductivity than any other non-metal except diamond, and exceeds that of ...

channel filler, which was surrounded by a uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

radiation mirror. The mirror and channel filler were open ended, and in this open end a flat plate of tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isolat ...

propellant was placed. The whole unit was built into a can with a diameter no larger than and weighed just over so it could be handled by machinery scaled-up from a soft-drink vending machine; Coca-Cola was consulted on the design.

At 1 microsecond after ignition the gamma bomb plasma and neutrons would heat the channel filler and be somewhat contained by the uranium shell. At 2–3 microseconds the channel filler would transmit some of the energy to the propellant, which vaporized. The flat plate of propellant formed a cigar-shaped explosion aimed at the pusher plate.

The plasma would cool to as it traversed the distance to the pusher plate and then reheat to as, at about 300 microseconds, it hits the pusher plate and is recompressed. This temperature emits ultraviolet light, which is poorly transmitted through most plasmas. This helps keep the pusher plate cool. The cigar shaped distribution profile and low density of the plasma reduces the instantaneous shock to the pusher plate.

Because the momentum transferred by the plasma is greatest in the center, the pusher plate's thickness would decrease by approximately a factor of 6 from the center to the edge. This ensures the change in velocity is the same for the inner and outer parts of the plate.

At low altitudes where the surrounding air is dense, gamma scattering could potentially harm the crew without a radiation shield; a radiation refuge would also be necessary on long missions to survive solar flare

A solar flare is an intense localized eruption of electromagnetic radiation in the Sun's atmosphere. Flares occur in active regions and are often, but not always, accompanied by coronal mass ejections, solar particle events, and other solar phe ...

s. Radiation shielding effectiveness increases exponentially with shield thickness, see gamma ray

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically ...

for a discussion of shielding. On ships with a mass greater than the structural bulk of the ship, its stores along with the mass of the bombs and propellant, would provide more than adequate shielding for the crew. Stability was initially thought to be a problem due to inaccuracies in the placement of the bombs, but it was later shown that the effects would cancel out.

Numerous model flight tests, using conventional explosives, were conducted at Point Loma, San Diego

Point Loma (Spanish: ''Punta de la Loma'', meaning "Hill Point"; Kumeyaay: ''Amat Kunyily'', meaning "Black Earth") is a seaside community within the city of San Diego, California. Geographically it is a hilly peninsula that is bordered on the ...

in 1959. On November 14, 1959 the one-meter model, also known as "Hot Rod" and "putt-putt", first flew using RDX

RDX (abbreviation of "Research Department eXplosive") or hexogen, among other names, is an organic compound with the formula (O2N2CH2)3. It is a white solid without smell or taste, widely used as an explosive. Chemically, it is classified as a ...

(chemical explosives) in a controlled flight for 23 seconds to a height of . Film of the tests has been transcribed to video and were featured on the BBC TV program "To Mars by A-Bomb" in 2003 with comments by Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

and Arthur C. Clarke. The model landed by parachute undamaged and is in the collection of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

The first proposed shock absorber was a ring-shaped airbag. It was soon realized that, should an explosion fail, the pusher plate would tear away the airbag on the rebound. So a two-stage detuned spring and piston shock absorber design was developed. On the reference design the first stage mechanical absorber was tuned to 4.5 times the pulse frequency whilst the second stage gas piston was tuned to 0.5 times the pulse frequency. This permitted timing tolerances of 10 ms in each explosion.

The final design coped with bomb failure by overshooting and rebounding into a center position. Thus following a failure and on initial ground launch it would be necessary to start or restart the sequence with a lower yield device. In the 1950s methods of adjusting bomb yield were in their infancy and considerable thought was given to providing a means of swapping out a standard yield bomb for a smaller yield one in a 2 or 3 second time frame or to provide an alternative means of firing low yield bombs. Modern variable yield devices would allow a single standardized explosive to be tuned down (configured to a lower yield) automatically.

The bombs had to be launched behind the pusher plate with enough velocity to explode beyond it every 1.1 seconds. Numerous proposals were investigated, from multiple guns poking over the edge of the pusher plate to rocket propelled bombs launched from roller coaster tracks, however the final reference design used a simple gas gun to shoot the devices through a hole in the center of the pusher plate.

Potential problems

Exposure to repeated nuclear blasts raises the problem of ''ablation'' (erosion) of the pusher plate. Calculations and experiments indicated that a steel pusher plate would ablate less than 1 mm, if unprotected. If sprayed with an oil it would not ablate at all (this was discovered by accident; a test plate had oily fingerprints on it and the fingerprints suffered no ablation). The absorption spectra ofcarbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

and hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

minimize heating. The design temperature of the shockwave, , emits ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nanometer, nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 Hertz, PHz) to 400 nm (750 Hertz, THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than ...

light. Most materials and elements are opaque to ultraviolet, especially at the pressures the plate experiences. This prevents the plate from melting or ablating.

One issue that remained unresolved at the conclusion of the project was whether or not the turbulence created by the combination of the propellant and ablated pusher plate would dramatically increase the total ablation of the pusher plate. According to Freeman Dyson, in the 1960s they would have had to actually perform a test with a real nuclear explosive to determine this; with modern simulation technology this could be determined fairly accurately without such empirical investigation.

Another potential problem with the pusher plate is that of spall

Spall are fragments of a material that are broken off a larger solid body. It can be produced by a variety of mechanisms, including as a result of projectile impact, corrosion, weathering, cavitation, or excessive rolling pressure (as in a ba ...

ing—shards of metal—potentially flying off the top of the plate. The shockwave from the impacting plasma on the bottom of the plate passes through the plate and reaches the top surface. At that point, spalling may occur, damaging the pusher plate. For that reason, alternative substances—plywood and fiberglass—were investigated for the surface layer of the pusher plate and thought to be acceptable.

If the conventional explosives in the nuclear bomb detonate but a nuclear explosion does not ignite, shrapnel could strike and potentially critically damage the pusher plate.

True engineering tests of the vehicle systems were thought to be impossible because several thousand nuclear explosions could not be performed in any one place. Experiments were designed to test pusher plates in nuclear fireballs and long-term tests of pusher plates could occur in space. The shock-absorber designs could be tested at full-scale on Earth using chemical explosives.

However, the main unsolved problem for a launch from the surface of the Earth was thought to be nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

. Freeman Dyson, group leader on the project, estimated back in the 1960s that with conventional nuclear weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

, each launch would statistically cause on average between 0.1 and 1 fatal cancers from the fallout. That estimate is based on no-threshold model assumptions, a method often used in estimates of statistical deaths from other industrial activities. Each few million dollars of efficiency indirectly gained or lost in the world economy may statistically average lives saved or lost, in terms of opportunity gains versus costs. Indirect effects could matter for whether the overall influence of an Orion-based space program on future human global mortality would be a net increase or a net decrease, including if change in launch costs and capabilities affected space exploration

Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space. While the exploration of space is carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration though is conducted both by robotic spacec ...

, space colonization

Space colonization (also called space settlement or extraterrestrial colonization) is the use of outer space or celestial bodies other than Earth for permanent habitation or as extraterrestrial territory.

The inhabitation and territor ...

, the odds of long-term human species survival, space-based solar power, or other hypotheticals.

Danger to human life was not a reason given for shelving the project. The reasons included lack of a mission requirement, the fact that no one in the U.S. government could think of any reason to put thousands of tons of payload into orbit, the decision to focus on rockets for the Moon mission, and ultimately the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all nuclear weapons testing, test detonations of nuclear weapons exce ...

in 1963. The danger to electronic systems on the ground from an electromagnetic pulse

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP), also a transient electromagnetic disturbance (TED), is a brief burst of electromagnetic energy. Depending upon the source, the origin of an EMP can be natural or artificial, and can occur as an electromagnetic fie ...

was not considered to be significant from the sub-kiloton blasts proposed since solid-state integrated circuits were not in general use at the time.

From many smaller detonations combined, the fallout for the entire launch of a Orion is equal to the detonation of a typical 10 megaton

Megaton may refer to:

* A million tons

* Megaton TNT equivalent, explosive energy equal to 4.184 petajoules

* megatonne, a million tonnes, SI unit of mass

Other uses

* Olivier Megaton (born 1965), French film director, writer and editor

* ''Me ...

(40 petajoule

The joule ( , ; symbol: J) is the unit of energy in the International System of Units (SI). It is equal to the amount of work done when a force of 1 newton displaces a mass through a distance of 1 metre in the direction of the force applied. ...

) nuclear weapon as an air burst, therefore most of its fallout would be the comparatively dilute delayed fallout. Assuming the use of nuclear explosives with a high portion of total yield from fission, it would produce a combined fallout total similar to the surface burst yield of the ''Mike'' shot of Operation Ivy, a 10.4 Megaton device detonated in 1952. The comparison is not quite perfect as, due to its surface burst location, ''Ivy Mike'' created a large amount of early fallout contamination. Historical above-ground nuclear weapon tests included 189 megatons

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a m ...

of fission yield and caused average global radiation exposure per person peaking at in 1963, with a residual in modern times, superimposed upon other sources of exposure, primarily natural background radiation

Background radiation is a measure of the level of ionizing radiation present in the environment at a particular location which is not due to deliberate introduction of radiation sources.

Background radiation originates from a variety of source ...

, which averages globally but varies greatly, such as in some high-altitude cities. Any comparison would be influenced by how population dosage is affected by detonation locations, with very remote sites preferred.

With special designs of the nuclear explosive, Ted Taylor estimated that fission product fallout could be reduced tenfold, or even to zero, if a pure fusion explosive could be constructed instead. A 100% pure fusion explosive has yet to be successfully developed, according to declassified US government documents, although relatively clean PNEs (Peaceful nuclear explosions

Peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs) are nuclear explosions conducted for non-military purposes. Proposed uses include excavation for the building of canals and harbours, electrical generation, the use of nuclear explosions to drive spacecraft, and a ...

) were tested for canal excavation by the Soviet Union in the 1970s with 98% fusion yield in the ''Taiga'' test's 15 kiloton

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a t ...

devices, 0.3 kiloton

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a t ...

s fission, which excavated part of the proposed Pechora–Kama Canal

The Pechora–Kama Canal (russian: Канал Печора-Кама), or sometimes the Kama–Pechora Canal, was a proposed canal intended to link up the basin of the Pechora River in the north of European Russia with the basin of the Kama, a trib ...

.

The vehicle's propulsion system and its test program would violate the Partial Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all nuclear weapons testing, test detonations of nuclear weapons exce ...

of 1963, as currently written, which prohibits all nuclear detonations except those conducted underground as an attempt to slow the arms race and to limit the amount of radiation in the atmosphere caused by nuclear detonations. There was an effort by the US government to put an exception into the 1963 treaty to allow for the use of nuclear propulsion for spaceflight but Soviet fears about military applications kept the exception out of the treaty. This limitation would affect only the US, Russia, and the United Kingdom. It would also violate the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a multilateral treaty to ban nuclear weapons test explosions and any other nuclear explosions, for both civilian and military purposes, in all environments. It was adopted by the United Nati ...

which has been signed by the United States and China as well as the de facto moratorium on nuclear testing that the declared nuclear powers have imposed since the 1990s.

The launch of such an Orion nuclear bomb rocket from the ground or low Earth orbit

A low Earth orbit (LEO) is an orbit around Earth with a period of 128 minutes or less (making at least 11.25 orbits per day) and an eccentricity less than 0.25. Most of the artificial objects in outer space are in LEO, with an altitude never mor ...

would generate an electromagnetic pulse

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP), also a transient electromagnetic disturbance (TED), is a brief burst of electromagnetic energy. Depending upon the source, the origin of an EMP can be natural or artificial, and can occur as an electromagnetic fie ...

that could cause significant damage to computer

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to Execution (computing), carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation) automatically. Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as C ...

s and satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotope ...

s as well as flooding the van Allen belts with high-energy radiation. Since the EMP footprint would be a few hundred miles wide, this problem might be solved by launching from very remote areas. A few relatively small space-based electrodynamic tether

Electrodynamic tethers (EDTs) are long conducting wires, such as one deployed from a tether satellite, which can operate on electromagnetism, electromagnetic principles as electrical generator, generators, by converting their kinetic energy to ele ...

s could be deployed to quickly eject the energetic particles from the capture angles of the Van Allen belts.

An Orion spacecraft could be boosted by non-nuclear means to a safer distance only activating its drive well away from Earth and its satellites. The Lofstrom launch loop

A launch loop, or Lofstrom loop, is a proposed system for launching objects into orbit using a moving cable-like system situated inside a sheath attached to the Earth at two ends and suspended above the atmosphere in the middle. The design conce ...

or a space elevator

A space elevator, also referred to as a space bridge, star ladder, and orbital lift, is a proposed type of planet-to-space transportation system, often depicted in science fiction. The main component would be a cable (also called a space tethe ...

hypothetically provide excellent solutions; in the case of the space elevator, existing carbon nanotubes

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon nan ...

composites, with the possible exception of Colossal carbon tube Colossal carbon tubes (CCTs) are a tubular form of carbon. In contrast to the carbon nanotubes (CNTs), colossal carbon tubes have much larger diameters ranging between 40 and 100 μm. Their walls have a corrugated structure with abundant pores, as ...

s, do not yet have sufficient tensile strength

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS), often shortened to tensile strength (TS), ultimate strength, or F_\text within equations, is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials t ...

. All chemical rocket designs are extremely inefficient and expensive when launching large mass into orbit but could be employed if the result were cost effective.

Notable personnel

*Lew Allen

Lew Allen Jr. (September 30, 1925 – January 4, 2010) was a United States Air Force four-star general who served as the tenth Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force. As chief of staff, Allen served as the senior uniformed Air Force officer ...

, Contract Manager

* Jerry Astl, explosives engineer

* Jeremy Bernstein

Jeremy Bernstein (born December 31, 1929, in Rochester, New York) is an American theoretical physicist and popular science writer.

Early life

Bernstein's parents, Philip S. Bernstein, a Reform rabbi, and Sophie Rubin Bernstein named him after th ...

, physicist

* Ed Creutz, physicist

* Brian Dunne, Orion's chief scientist

* Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

, physicist

* Harry Finger

Harold Benjamin Finger (born February 18, 1924) is an American aeronautical nuclear engineer and the former head of the United States nuclear rocket program. He helped establish and lead the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office, a liaison organizati ...

, physicist

* Burt Freeman

Burton E Freeman (July 3, 1924 – October 4, 2016) was an American physicist and explosive engineer who researched the calculated expedition timetables for the American Project Orion nuclear propulsion

Nuclear propulsion includes a wide vari ...

, physicist

* Harris Mayer, physicist

* James Nance, Project Director

* H. Pierre Noyes

H. Pierre Noyes (December 10, 1923 – September 30, 2016) was an American theoretical physicist. He became a member of the faculty at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University in 1962. Noyes specialized in several areas o ...

, physicist

* Kedar "Bud" Pyatt, mathematician

* Morris Scharff, physicist

* Charles Clark Loomis, physicist

* Ted Taylor, Project Director

* Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

, mathematician

* Micheal Treshow, physicist

* Ron F. Prater, USAF Liaison

* Edward B. Giller, USAF Liaison

* Don Prickett, USAF Liaison

* Howard R. Kratz, physicist

* Carlo Riparbelli, physicist

* Thomas Macken

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, physicist

* David Weiss, test pilot

* Rudy A. Cesena, physicist

* Ed A. Day

Ed, ed or ED may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Ed'' (film), a 1996 film starring Matt LeBlanc

* Ed (''Fullmetal Alchemist'') or Edward Elric, a character in ''Fullmetal Alchemist'' media

* ''Ed'' (TV series), a TV series that ran fro ...

, physicist

* Mike R. Ames, physicist

* Richard D. Morton, physicist

* Reed Watson, physicist

* Richard Goddard, physicist

* Menley Young, physicist

* Michael J. Feeney, physicist

* Jim W. Morris, physicist

* R. N. House, physicist

* Leon Dial

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again f ...

, physicist

* W. B. McKinney W. may refer to:

* SoHo (Australian TV channel) (previously W.), an Australian pay television channel

* ''W.'' (film), a 2008 American biographical drama film based on the life of George W. Bush

* "W.", the fifth track from Codeine's 1992 EP '' B ...

, physicist

* J. R. Pope, physicist

* Fred W. Ross

Fred may refer to:

People

* Fred (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Mononym

* Fred (cartoonist) (1931–2013), pen name of Fred Othon Aristidès, French

* Fred (footballer, born 1949) (1949–2022), Frederico R ...

, physicist

* Perry B Ritter, physicist

* Walt England, physicist

* William(Bill) G. Vulliet

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

, physicist

* John Illes

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, security guard

* Lois Illes, secretary

* Jonnie Stahl, secretary

* Don Mixson, USAF Liaison

* Robert B Duffield, Chemist

* John J Dishuck, USAF Liaison

* Fred Gorschboth

Fred may refer to:

People

* Fred (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Mononym

* Fred (cartoonist) (1931–2013), pen name of Fred Othon Aristidès, French

* Fred (footballer, born 1949) (1949–2022), Frederico R ...

, USAF Liaison

* Ralph Stahl, physicist

Operation Plumbbob

A test that was similar to the test of a pusher plate occurred as an accidental side effect of a nuclear containment test called " Pascal-B" conducted on 27 August 1957. The test's experimental designer Dr. Robert Brownlee performed a highly approximate calculation that suggested that the low-yield nuclear explosive would accelerate the massive (900 kg) steel capping plate to six timesescape velocity

In celestial mechanics, escape velocity or escape speed is the minimum speed needed for a free, non- propelled object to escape from the gravitational influence of a primary body, thus reaching an infinite distance from it. It is typically ...

. The plate was never found but Dr. Brownlee believes that the plate never left the atmosphere; for example, it could have been vaporized by compression heating of the atmosphere due to its high speed. The calculated velocity was interesting enough that the crew trained a high-speed camera on the plate which, unfortunately, only appeared in one frame indicating a very high lower bound for the speed of the plate.

Notable appearances in fiction

The first appearance of the idea in print appears to beRobert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

's 1940 short story, "Blowups Happen

"Blowups Happen" is a 1940 science fiction short story by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. It is one of two stories in which Heinlein, using only public knowledge of nuclear fission, anticipated the actual development of nuclear technology a few ...

."

As discussed by Arthur C. Clarke in his recollections of the making of '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' in ''The Lost Worlds of 2001

''The Lost Worlds of 2001'' is a 1972 book by English writer Arthur C. Clarke, published as an accompaniment to the novel '' 2001: A Space Odyssey''.

The book consists in part of behind-the-scenes notes from Clarke concerning scriptwriting (and ...

'', a nuclear-pulse version of the U.S. interplanetary spacecraft ''Discovery One

The United States Spacecraft ''Discovery One'' is a fictional spaceship featured in the first two novels of the ''Space Odyssey'' series by Arthur C. Clarke and in the films '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'' (1968) directed by Stanley Kubrick and '' 20 ...

'' was considered. However the ''Discovery'' in the movie did not use this idea, as Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, producer, screenwriter, and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films, almost all of which are adaptations of nove ...

thought it might be considered parody after making '' Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb''.

An Orion spaceship features prominently in the science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

novel ''Footfall

''Footfall'' is a 1985 science fiction novel by American writers Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. The book depicts the arrival of members of an alien species called the Fithp that have traveled to the Solar System from Alpha Centauri in a large ...

'' by Larry Niven

Laurence van Cott Niven (; born April 30, 1938) is an American science fiction writer. His best-known works are ''Ringworld'' (1970), which received Hugo, Locus, Ditmar, and Nebula awards, and, with Jerry Pournelle, ''The Mote in God's Eye'' ...

and Jerry Pournelle

Jerry Eugene Pournelle (; August 7, 1933 – September 8, 2017) was an American scientist in the area of operations research and human factors research, a science fiction writer, essayist, journalist, and one of the first bloggers. In the 1960s ...

. In the face of an alien siege/invasion of Earth, the humans must resort to drastic measures to get a fighting ship into orbit to face the alien fleet.

The opening premise of the show '' Ascension'' is that in 1963 President John F. Kennedy and the U.S. government, fearing the Cold War will escalate and lead to the destruction of Earth, launched the ''Ascension'', an Orion-class spaceship, to colonize a planet orbiting Proxima Centauri, assuring the survival of the human race.

Author Stephen Baxter's science fiction novel ''Ark

Ark or ARK may refer to:

Biblical narratives and religion Hebrew word ''teva''

* Noah's Ark, a massive vessel said to have been built to save the world's animals from a flood

* Ark of bulrushes, the boat of the infant Moses

Hebrew ''aron''

* ...

'' employs an Orion-class generation ship to escape ecological disaster on Earth.

Towards the conclusion of his Empire Games trilogy, Charles Stross

Charles David George "Charlie" Stross (born 18 October 1964) is a British writer of science fiction and fantasy. Stross specialises in hard science fiction and space opera. Between 1994 and 2004, he was also an active writer for the magazine '' ...

includes a spacecraft modeled after Project Orion. The crafts' designers, constrained by a 1960's level of industrial capacity, intend it to be used to explore parallel worlds and to act as a nuclear deterrent, leapfrogging their foes more contemporary capabilities.

See also

*AIMStar

AIMStar was a proposed antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion craft that uses clouds of antiprotons to initiate fission and fusion within fuel pellets. A magnetic nozzle derives motive force from the resulting explosions. The design was stud ...

* Antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion

Antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion (also antiproton-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion) is a variation of nuclear pulse propulsion based upon the injection of antimatter into a mass of nuclear fuel to initiate a nuclear chain reaction f ...

* Helios (propulsion system)

* NERVA (Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application)

* Nuclear propulsion

Nuclear propulsion includes a wide variety of propulsion methods that use some form of nuclear reaction as their primary power source. The idea of using nuclear material for propulsion dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. In 1903 it was ...

* Project Pluto

Project Pluto was a United States government program to develop nuclear-powered ramjet engines for use in cruise missiles. Two experimental engines were tested at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) in 1961 and 1964 respectively.

On 1 January 1957, t ...

* Project Prometheus

Project Prometheus (also known as Project Promethian) was established in 2003 by NASA to develop nuclear-powered systems for long-duration space missions. This was NASA's first serious foray into nuclear spacecraft propulsion since the cancellat ...

* Project Valkyrie

The Valkyrie is a theoretical spacecraft designed by Charles Pellegrino and Jim Powell (a physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory). The Valkyrie is theoretically able to accelerate to 92% the speed of light and decelerate afterward, carrying ...

* Peaceful nuclear explosion

Peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs) are nuclear explosions conducted for non-military purposes. Proposed uses include excavation for the building of canals and harbours, electrical generation, the use of nuclear explosions to drive spacecraft, and a ...

References

Further reading

* * *"Nuclear Pulse Propulsion (Project Orion) Technical Summary Report" RTD-TDR-63-3006 (1963–1964); GA-4805 Vol. 1: Reference Vehicle Design Study, Vol. 2: Interaction Effects, Vol. 3: Pulse Systems, Vol. 4: Experimental Structural Response. (From the National Technical Information Service, U.S.A.) *"Nuclear Pulse Propulsion (Project Orion) Technical Summary Report" 1 July 1963 – 30 June 1964, WL-TDR-64-93; GA-5386 Vol. 1: Summary Report, Vol. 2: Theoretical and Experimental Physics, Vol. 3: Engine Design, Analysis and Development Techniques, Vol. 4: Engineering Experimental Tests. (From the National Technical Information Service, U.S.A.) *General Atomics''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume I -- Summary''

September 19, 1964 *General Atomics

''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume III -- Conceptual Vehicle Designs And Operational Systems''

September 19, 1964 *General Atomics

''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume IV -- Mission Velocity Requirements And System Comparisons''

February 28, 1966 *General Atomics

''Nuclear Pulse Space Vehicle Study, Volume IV -- Mission Velocity Requirements And System Comparisons (Supplement)''

February 28, 1966 * *NASA

''Nuclear Pulse Vehicle Study Condensed Summary Report (General Dynamics Corp)''

January 14, 1964

External links

at

TED

TED may refer to:

Economics and finance

* TED spread between U.S. Treasuries and Eurodollar

Education

* ''Türk Eğitim Derneği'', the Turkish Education Association

** TED Ankara College Foundation Schools, Turkey

** Transvaal Education Depa ...

{{Authority control

Orion

Hypothetical spacecraft

Single-stage-to-orbit

Space access

Orion

Freeman Dyson

Interstellar travel