Timoleague Friary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Timoleague Friary (), also known as Timoleague Abbey, is a ruined medieval

The date of foundation by the Franciscans is disputed. Documentary evidence places the foundation of the friary between 1307 and 1316, though physical evidence suggests that a preexisting 13th-century building was incorporated into the site. According to the

The date of foundation by the Franciscans is disputed. Documentary evidence places the foundation of the friary between 1307 and 1316, though physical evidence suggests that a preexisting 13th-century building was incorporated into the site. According to the

The friary is the largest medieval ruin in

The friary is the largest medieval ruin in  The

The  The friary originally had a

The friary originally had a

William Ashford depicted the friary several times: first in a pencil sketch, and then again among his earliest landscape works, which include a rough drawing of the friary, titled ''Timoleague (abbey ruins)'', which he followed with two 1776 watercolours of the ruins. The Irish writer Seán Ó Coileáin wrote the c. 1913 poem about the ruins.

William Ashford depicted the friary several times: first in a pencil sketch, and then again among his earliest landscape works, which include a rough drawing of the friary, titled ''Timoleague (abbey ruins)'', which he followed with two 1776 watercolours of the ruins. The Irish writer Seán Ó Coileáin wrote the c. 1913 poem about the ruins.

File:Timoleague.jpg, View of Timoleague Friary

File:Timoleague Friary Church.jpg, Interior of church

Lament over the Ruins of the Abbey of Teach Molaga

' an English translation o

a poem written in 1814 by Seághan Ó Coileáin about the friary, translated by

Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

friary

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

in Timoleague

Timoleague () is a village in the eastern division of Carbery East in County Cork, Ireland. It is located along Ireland's southern coast between Kinsale and Clonakilty, on the estuary of the Argideen River. Nearby is the village of Courtmacs ...

, County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, on the banks of the Argideen River

The Argideen River is a minor river in West Cork, Ireland. Its source is at Reenascreena and it flows for 23 kilometres to the estuary at Timoleague, joining the Celtic Sea at the village of Courtmacsherry.

The Argideen drains peat bogs north- ...

overlooking Courtmacsherry

Courtmacsherry (), often referred to by locals as Courtmac, is a seaside village in County Cork, on the southwest coast of Ireland. It is about 30 miles southwest of Cork, and 15–20 minutes drive east from the town of Clonakilty. The village co ...

Bay. It was built on the site of an early Christian monastic site founded by Saint Molaga, from whom the town of Timoleague derives its name. The present remains date from roughly the turn of the fourteenth century and were burnt down by British forces in the mid-seventeenth century, at which point it was an important ecclesiastical centre that engaged in significant trade with Spain.

The friary is the largest medieval ruin in West Cork

West Cork ( ga, Iarthar Chorcaí) is a tourist region and municipal district in County Cork, Ireland. As a municipal district, West Cork falls within the administrative area of Cork County Council, and includes the towns of Bantry, Castletownbe ...

and one of the few early Franciscan friaries in Ireland to have substantial ruins. It is claustral in layout, and built in the Early English Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

architectural style. It contains several elements atypical of Franciscan architecture of the period, including wall passages and exterior access to its upper floor. It was significantly altered in the early 16th and early 17th centuries. Several historical artefacts are associated with the friary, and during the Romantic era

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

it was depicted in several notable artworks.

History

Monastic site

The friary sits on a monastic site dedicated to Saint Molaga dating to either the 6th or 7th century. According to legend, this settlement was originally to be formed a mile west of Timoleague, but all work done on that site by day would fall down by morning. Interpreting this as God's will that the friary be built elsewhere, Molaga supposedly placed a blessed candle on a sheaf of corn, and set it down theArgideen River

The Argideen River is a minor river in West Cork, Ireland. Its source is at Reenascreena and it flows for 23 kilometres to the estuary at Timoleague, joining the Celtic Sea at the village of Courtmacsherry.

The Argideen drains peat bogs north- ...

, building his settlement on the spot that it came ashore, in an area overlooking Courtmacsherry

Courtmacsherry (), often referred to by locals as Courtmac, is a seaside village in County Cork, on the southwest coast of Ireland. It is about 30 miles southwest of Cork, and 15–20 minutes drive east from the town of Clonakilty. The village co ...

Bay. The town derives its Irish name, or "Molaga's House" from the saint.

Foundation and early history

The date of foundation by the Franciscans is disputed. Documentary evidence places the foundation of the friary between 1307 and 1316, though physical evidence suggests that a preexisting 13th-century building was incorporated into the site. According to the

The date of foundation by the Franciscans is disputed. Documentary evidence places the foundation of the friary between 1307 and 1316, though physical evidence suggests that a preexisting 13th-century building was incorporated into the site. According to the Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

, the friary was founded in 1240 by the MacCarthy Reagh family. This has been identified as possibly being too early. Some sources ascribe this claimed foundation to Domhnall Got MacCarthy, while others claim that Got MacCarthy merely expanded the friary anywhere between 1312 and 1366. Domhnall's grandson, Domhnall Glas MacCarthy, is also thought to have been a patron of the friary. Samuel Lewis, in ''A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland...'' (1837) writes that the MacCarthy's founded the friary in 1312. The friary's foundation has also been attributed to the Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

* Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

* Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 10 ...

de Barry family

The de Barry family is a noble family of Cambro-Norman origins which held extensive land holdings in Wales and Ireland. The founder of the family was a Norman Knight, Odo, who assisted in the Norman Conquest of England during the 11th century. ...

in the early 14th century. Though the friars were well established in Timoleague by 1320, the earliest surviving parts of the ruined friary date from later in the 14th century. It is likely that they were based in Timoleague Castle prior to the construction of the friary.

By the 15th century, the friary was recognised as a centre of learning, and also as an important ecclesiastical centre. In 1460, Timoleague became one of the first houses in the Franciscan order to recognise the observantine reform. Tadhg Mac Cárthaigh, also known as "Blessed Thaddeus", is said to have been educated by the friars in Timoleague around this time. According to the Annals of Ulster

The ''Annals of Ulster'' ( ga, Annála Uladh) are annals of medieval Ireland. The entries span the years from 431 AD to 1540 AD. The entries up to 1489 AD were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luinín, ...

, in 1505 Patrick Ó Feidhil, a famous preacher in Ireland and Scotland, was buried in the friary.

An important patron of the church was Bishop John Edmond de Courcy, along with his nephew James, 8th Baron Kingsale

Baron Kingsale is a title of the premier baron in the Peerage of Ireland. The feudal barony dates to at least the thirteenth century. The first peerage creation was by writ.

Name and precedence

In the early times the name was "Kinsale" or " ...

. They funded the construction of the Gothic style

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

bell tower, the infirmary, the library, and one of the dormitories. De Courcy had been a friar in Timoleague before being made a bishop. The tower was added between 1510 and 1518. They also contributed to the friary's collection of plate. John de Courcy was buried in the transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building withi ...

of the friary, but in the Cromwellian period his grave was desecrated

Desecration is the act of depriving something of its sacred character, or the disrespectful, contemptuous, or destructive treatment of that which is held to be sacred or holy by a group or individual.

Detail

Many consider acts of desecration to ...

and his bones thrown into the estuary

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

.

Despite the dissolution of the monasteries in 1540 by Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, the friars remained in Timoleague. In 1568, the friary was seized by crown forces, and in 1577 was granted to James de Barry, 4th Viscount Buttevant

Earl of Barrymore was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created for David Barry, 6th Viscount Buttevant, in 1627/28. Lord Barrymore held the subsidiary titles of Baron Barry (created c. 1261) and Viscount Buttevant (created 1541) in th ...

. Despite this, Timoleague remained an important centre for the training of the novitiate

The novitiate, also called the noviciate, is the period of training and preparation that a Christian ''novice'' (or ''prospective'') monastic, apostolic, or member of a religious order undergoes prior to taking vows in order to discern whether ...

until the late 1580s. In 1590, the Protestant Bishop of Cork

The Bishop of Cork was a separate episcopal title which took its name after the city of Cork in Ireland. The title is now united with other bishoprics. In the Church of Ireland it is held by the Bishop of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, and in the Roman C ...

ordered materials to be taken from the friar's mill to be used in the construction of a new mill he was building, but the river flooded and swept away all progress on the new mill. In 1596, the friary's wooden cells were removed and were being transported by ship, but the ship sank in a storm. After the succession of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, the friary was reclaimed by Catholics in 1603, and was repaired in its entirety by the end of 1604. During these repairs, significant changes were made to the architecture of the friary.

Abandonment and destruction

In 1612, Bishop Lyons came to Timoleague to disperse the friars but was repelled by an Irish force led by Daniel O'Sullivan. Though the friary had reportedly been re-edified by 1613, by the time of Donatus Mooney's visit in 1616, the friary could no longer be considered genuinely inhabited. In 1629, four years after the death of King James, Richard Boyle was named Lord Justice and instigated the closure of religious buildings across Cork, putting increasing pressure on the friary. It is assumed, however, that the friary was already largely abandoned by the Franciscans by this point, as the guardian appointed to the friary, Eugenius Fildaeus, was appointed in Limerick, . By 1631 the friary had been largely plundered by Protestant settlers. Despite these accounts, the friary was reportedly renowned for its School of Philosophy, established in 1620 and led by Owen O'Fihelly. Furthermore, in 1629Mícheál Ó Cléirigh

Mícheál Ó Cléirigh (), sometimes known as Michael O'Clery, was an Irish chronicler, scribe and antiquary and chief author of the ''Annals of the Four Masters,'' assisted by Cú Choigcríche Ó Cléirigh, Fearfeasa Ó Maol Chonaire, and Pereg ...

reportedly transcribed material from the Book of Lismore

The Book of Lismore, also known as the Book of Mac Carthaigh Riabhach, is a late fifteenth-century Gaelic manuscript that was created at Kilbrittain in County Cork, Ireland, for Fínghean Mac Carthaigh, Lord of Carbery (1478–1505). Defective ...

in the friary library.

The friary was eventually burnt down by crown forces in July 1642, when a force led by Lord Kinelmeaky failed to capture Timoleague Castle and instead burnt the friary and much of the town. Franciscan houses were commonly founded at trading ports, and Timoleague is no exception: the friary at one time engaged in significant trade with France, and in particular, Spain. The monks likely traded Irish agricultural goods such as hides, butter, timber, and corn in exchange for wine: an account of the burning of the friary states that: "We burnt all the towne, and their great Abbey, in which was some thousand barrels of wine." The destruction of the friary led to a significant downturn in the financial development of the town.

As ruins

After the friary was burnt, local families began to bury their dead within the friary regardless of status, something which previously had only been done for prominent local families. Despite the burning of the friary, the Franciscan community of Timoleague survived for close to two centuries. In 1696 four friars were reportedly living in the ruined monastery. Though the Franciscan community dispersed by the mid-eighteenth century, individual friars remained in the area for several more decades. The last Franciscan friar working in the area was Fr Edmund Tobin (also known as Bonaventure Tobin), who died circa 1822. The Franciscans appointed titular guardians of the friary up until 1872. The last guardian of Timoleague friary was Patrick Carey. Interest in the friary was renewed during theRomantic era

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

of the early 19th century, and many paintings and sketches of the friary exist from this period. On 15 January 1848, Fr Matt Horgan, writing under the pen-name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

"Viator", wrote the following which was released in the ''Cork Examiner:''

Soon after the publication of these remarks, Colonel Robert Travers, the so-called "lord of the soil", had the walls of the friary grounds replaced, and a road built between them and the sea, all at his own expense. In 1891, mass was celebrated in the friary for the first time since it was burnt down 249 years prior. One of the Timoleague chalices (the Dale-Browne Chalice) was used on the occasion. In 1892, Denham Franklin wrote that

In 1920, in response to the murder of three police officers by Irish nationalists, British soldiers desecrated the friary's burial ground. Burial vaults were opened, and the flags that had been draped over the coffins within were torn and cast aside. Coffins were opened, and in some cases, human remains were left visible.

The friary ahs been listed as a discovery point on the Wild Atlantic Way

The Wild Atlantic Way ( ga, Slí an Atlantaigh Fhiáin) is a tourism trail on the west coast, and on parts of the north and south coasts, of Ireland. The 2,500 km (1,553 mile) driving route passes through nine counties and three provinces, s ...

since it was established in 2014. Irish-language writer Máire Ní Shíthe was interred in the friary in an unmarked grave in 1955. In 2016 the location of her burial was identified, and a commemorative stone placed above it.

Architecture

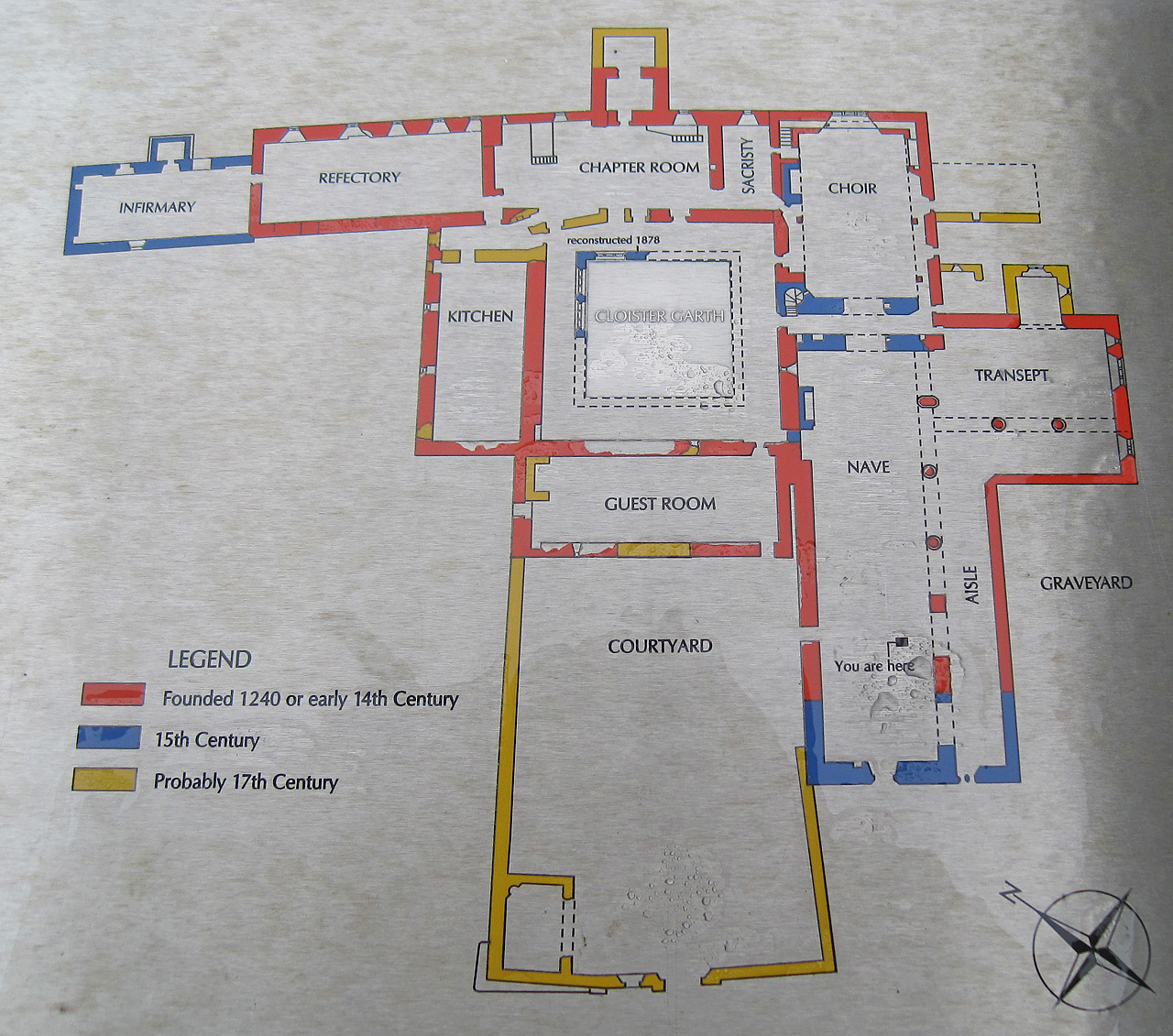

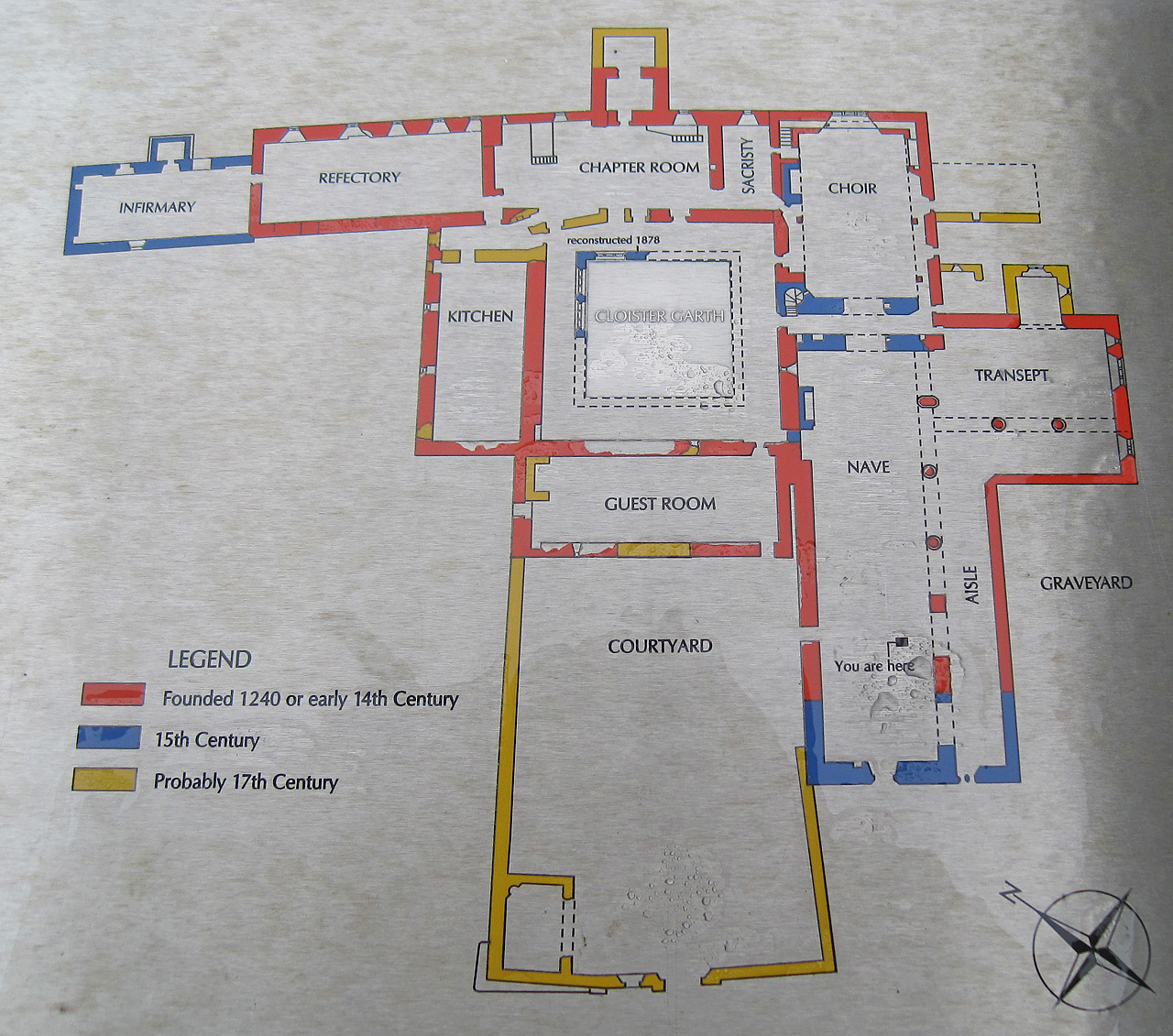

The friary is the largest medieval ruin in

The friary is the largest medieval ruin in West Cork

West Cork ( ga, Iarthar Chorcaí) is a tourist region and municipal district in County Cork, Ireland. As a municipal district, West Cork falls within the administrative area of Cork County Council, and includes the towns of Bantry, Castletownbe ...

. The use of locally available freestone was typical in the construction of Franciscan friaries of the period, and Timoleague Friary is no exception, having been made from locally sourced slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

, quarried in nearby Borleigh. Built in the Early English Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

architectural style, the architectural details are quite plain. Despite the extensive standing remains, the friary was once much larger than it is today. Records show that in the late 1500s the friary had a mill attached to the main structure, and that the monastery stood on a 4.5 acre site — four times larger than what is left of the friary grounds today.

At the entrance to the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

, now used as the main entrance to the friary, a fleur-de-lis

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural ''fleurs-de-lis'' or ''fleurs-de-lys''), is a lily (in French, and mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

The fleur-de-lis has been used in the ...

is engraved on the left jamb

A jamb (from French ''jambe'', "leg"), in architecture, is the side-post or lining of a doorway or other aperture. The jambs of a window outside the frame are called “reveals.” Small shafts to doors and windows with caps and bases are know ...

. The doorway features simple mouldings, features of the Perpendicular Gothic period. The original monks were likely French-speaking, and would have used the fleur-de-lis as an aid to describing the Holy Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

. A small recess above the door was used to hold either a sculpture or other religious imagery. The nave was considerably smaller when the friary was first constructed; it features an arcade of six arches, only three of which are original.

A leprosarium

A leper colony, also known by many other names, is an isolated community for the quarantining and treatment of lepers, people suffering from leprosy. '' M. leprae'', the bacterium responsible for leprosy, is believed to have spread from East Af ...

was located in Spittal, a nearby townland, and as a result, the south window of the transept was known as the "Leper's Hole" or "Lepers' Window" — a gap through which sufferers of leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

could see and hear the service, and partake in the Blessed Sacrament

The Blessed Sacrament, also Most Blessed Sacrament, is a devotional name to refer to the body and blood of Christ in the form of consecrated sacramental bread and wine at a celebration of the Eucharist. The term is used in the Latin Church of the ...

. The window is narrower on the outside than it is on the inside, and the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

was likely passed out by the monks on a spoon so as to avoid contact with a disease which was considered highly contagious at the time.

The

The choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

is the oldest part of the friary and may have originally been an early 13th-century castle or church that the Franciscans later added to. It is notably tall and features unusual components such as long arches and triforium

A triforium is an interior gallery, opening onto the tall central space of a building at an upper level. In a church, it opens onto the nave from above the side aisles; it may occur at the level of the clerestory windows, or it may be locate ...

wall passages. It features four widely splayed arched recesses in the north and south walls, separated by piers Piers may refer to:

* Pier, a raised structure over a body of water

* Pier (architecture), an architectural support

* Piers (name), a given name and surname (including lists of people with the name)

* Piers baronets, two titles, in the baronetages ...

, one of which is now covered by the base of the tower. The recess nearest the east gable contained the sedilia

In church architecture, sedilia (plural of Latin ''sedīle'', "seat") are seats, usually made of stone, found on the liturgical south side of an altar, often in the chancel, for use during Mass for the officiating priest and his assistants, the ...

. A niche on the northern wall once contained an altar in memory of the de Courcey family. The great window in the choir faces east, and once contained elaborate stained glass imagery. The graves of the McCarthy Reagh family are also located here.

The sacristy

A sacristy, also known as a vestry or preparation room, is a room in Christian churches for the keeping of vestments (such as the alb and chasuble) and other church furnishings, sacred vessels, and parish records.

The sacristy is usually located ...

features a bullaun

A bullaun ( ga, bullán; from a word cognate with "bowl" and French ''bol'') is the term used for the depression in a stone which is often water filled. Natural rounded boulders or pebbles may sit in the bullaun. The size of the bullaun is high ...

stone, commonly known as a “wart well” as the water in the depression was said to heal warts. This stone is far older than any other aspect of the friary, and may have originally been associated with the original 6th or 7th century monastic site.

One of the protruding stones on the exterior wall is known as "St Molaga's Head". A gift given by French sailors as thanksgiving for safe harbour following a storm at sea, it was originally a sculpture of Molaga's head, but the facial features have been completely eroded.

A room generally considered to have been the library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

is the only section of the friary not in use as a burial ground. This may have been the place of residence of the friars who remained in Timoleague after the destruction of the friary. The windows present in the remaining ground floor of this room would not have been sufficient for literary work, and the library was actually more likely to have been on the upper floor.

When Donatus Mooney visited the friary in the 17th century, he noted that the ceilings above the refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminaries. The name derives from the La ...

and the chapter room

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole communi ...

were supported by beams of carved oak. The chapter room may have at one time been the location of the library, though it was later used for storage purposes. The chamber designated as the refectory is evidenced by traces of a reader's seat and one of the five windows which lighted it.

The friary originally had a

The friary originally had a cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

, but only a portion of its walls remain standing. It is unclear whether the ambulatory

The ambulatory ( la, ambulatorium, ‘walking place’) is the covered passage around a cloister or the processional way around the east end of a cathedral or large church and behind the high altar. The first ambulatory was in France in the 11th ...

extended along the western side. The cloister and the monk's living quarters are towards the north of the church, which is typical of Irish Franciscan friaries. The cloister quadrangle would have covered an area across by wide. In the south wall of the cloister is an intramural space known locally as "The Fairy Cupboard". In the 1800s, some local children supposedly entered the Fairy Cupboard and discovered a parchment manuscript beneath one of the flagstones, which they used as a football before the remainder was eaten by pigs. Documentary evidence suggests that there was exterior access from the cloister to rooms on the upper floor, which would have been unusual. Though there are no traces of steps, there are indications that the space typically occupied by the chapter room in Franciscan friaries was used as a cellarage, and that the chapter room was located above. A further atypical feature of the friary is that alongside the cloister it has a large outdoor courtyard

A courtyard or court is a circumscribed area, often surrounded by a building or complex, that is open to the sky.

Courtyards are common elements in both Western and Eastern building patterns and have been used by both ancient and contemporary ...

.

The bell tower

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell tower ...

is one of fourteen pre-reformation towers built in Franciscan monasteries that still stand today. It is a later addition to the friary, and was erected in the early 16th century. The tower is wider from north to south than from west to east, a feature typical of Franciscan towers. It measures from west to east and from north to south. Also typical is the abrupt narrowing of the cross-walls from the north and south at the point where the tower begins. The tower is more obviously battered than most Franciscan towers. The tower is battlement

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at interva ...

ed, as are almost all surviving towers. The top of the tower has three merlon

A merlon is the solid upright section of a battlement (a crenellated parapet) in medieval architecture or fortifications.Friar, Stephen (2003). ''The Sutton Companion to Castles'', Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 2003, p. 202. Merlons are sometimes ...

s rising to each of its four corners.

Historical artefacts

Book of Lismore

, or the Book of Lismore, also known as , is a 15th-century manuscript with connections to the friary. Though some sources claim that the manuscript was written or partly written in the friary, Professor Pádraig Ó Macháin, an expert on Irish manuscripts, says that that is not the case. It was held in the friary at times, and material from the book was transcribed there by Mícheál Ó Cléirigh in 1629.Timoleague Chalices

Two 17th centurychalice

A chalice (from Latin 'mug', borrowed from Ancient Greek () 'cup') or goblet is a footed cup intended to hold a drink. In religious practice, a chalice is often used for drinking during a ceremony or may carry a certain symbolic meaning.

Re ...

s – both of which are referred to as the "Timoleague Chalice" – are associated with the friary. The first, also known as the "Dale-Browne Chalice", or the "Dale Chalice", is made of gilt silver and was created circa. 1600. After the suppression of the monastery, one of the friars supposedly escaped with the chalice, disguised himself and lived as a farmer. His dying wish was that the chalice and his vestment

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Anglicans, and Lutherans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; this ...

s were buried in a box beneath his house and that they remain buried until the friary was restored and the friars had returned. Years later, the box was discovered while the house was undergoing renovations. The contents were given to Franciscans in Cork.

The earlier chalice is engraved with the words "." around the base, which translates as "Pray for the souls of Charles Daly and Elizabeth Browne, Timoleague". It is 8.5 inches tall, with the tulip-shaped bowl measuring 3.25 inches wide and 3 inches deep. Its primary decoration is on one facet of its tall hexagonal foot. It depicts a selection of the Instruments of the Passion

Arma Christi ("weapons of Christ"), or the Instruments of the Passion, are the objects associated with the Passion of Jesus Christ in Christian symbolism and art. They are seen as arms in the sense of heraldry, and also as the weapons Chris ...

: a central cross with a spear to one side and a stick with a sponge on the other. The cross is depicted as the tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History ...

, with branches sprouting from its tip and base and shamrocks forming its head and arms. The chalice was likely a gift from the Dalys (Elizabeth Browne being Charles' wife) to the friars upon their return to the friary after its suppression in 1568. It is currently held by the Collins Barracks

Collins Barracks ( ga, Dún Uí Choileáin) is a former military barracks in the Arbour Hill area of Dublin, Ireland. The buildings now house the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts and History.

Previously housing both British Arm ...

branch of the National Museum of Ireland

The National Museum of Ireland ( ga, Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann) is Ireland's leading museum institution, with a strong emphasis on national and some international archaeology, Irish history, Irish art, culture, and natural history. It has thre ...

.

The later chalice, also known as the "Timoleague Franciscan Chalice", is made of gold and may date to c. 1633. When the friary was burned, three friars supposedly fled via rowboat and were found at sea by fishermen from Cape Clear Island

Clear Island or Cape Clear Island (officially known by its Irish name: Cléire, and sometimes also called Oileán Chléire) is an island off the south-west coast of County Cork in Ireland. It is the southernmost inhabited part of Ireland and ha ...

, by which time two of them had died. A box was left with the fishermen by the surviving friar, with instructions that they not open it as he would one day return for it, though he never did. It was re-opened in 1860 and found to contain a set of severely deteriorated vestments and a chalice "black with age". The chalice is engraved with the words "''ffr'MinConv de Thimolaggi"'' ("Friars Minor Convent of Timoleague"). In 1892, 250 years after the chalice was removed from the town, it was returned to the parish priest of Timoleague. It has remained in the safekeeping of his successors, and an exact replica of the chalice is on permanent display in the local Catholic church.

In culture

William Ashford depicted the friary several times: first in a pencil sketch, and then again among his earliest landscape works, which include a rough drawing of the friary, titled ''Timoleague (abbey ruins)'', which he followed with two 1776 watercolours of the ruins. The Irish writer Seán Ó Coileáin wrote the c. 1913 poem about the ruins.

William Ashford depicted the friary several times: first in a pencil sketch, and then again among his earliest landscape works, which include a rough drawing of the friary, titled ''Timoleague (abbey ruins)'', which he followed with two 1776 watercolours of the ruins. The Irish writer Seán Ó Coileáin wrote the c. 1913 poem about the ruins. James Hardiman

James Hardiman (1782–1855), also known as Séamus Ó hArgadáin, was a librarian at Queen's College, Galway.

Hardiman is best remembered for his '' History of the Town and County of Galway'' (1820) and '' Irish Minstrelsy'' (1831), one of the f ...

described it as one of the "finest modern poems in the Irish language" in 1831. It has been translated to English several times, including as ''The Mourner's Soliloquy in the Ruined Abbey of Timoleague'' and as ''Lament over the Ruins of the Abbey of Teach Molaga'' by Sir Samuel Ferguson. A bronze cast of one of the verses in the original Irish is located at the entrance gate of the ruins.

Gallery

References

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{refendExternal links

*Lament over the Ruins of the Abbey of Teach Molaga

' an English translation o

a poem written in 1814 by Seághan Ó Coileáin about the friary, translated by

James Clarence Mangan

James Clarence Mangan, born James Mangan ( ga, Séamus Ó Mangáin; 1 May 1803, Dublin – 20 June 1849), was an Irish poet.

He freely translated works from German, Turkish, Persian, Arabic, and Irish, with his translations of Goethe gaining sp ...

.

Franciscan monasteries in the Republic of Ireland

Buildings and structures in County Cork

Religion in County Cork

Ruins in the Republic of Ireland

National Monuments in County Cork

Tourist attractions in County Cork