Thracian Scientific Institute on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area between northern Greece, southern Russia, and north-western Turkey. They shared the same language and culture... There may have been as many as a million Thracians, diveded among up to 40 tribes." Thracians resided mainly in the Balkans (mostly modern day Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece) but were also located in Anatolia (Asia Minor) and other locations in Eastern Europe.

The exact origin of Thracians is unknown, but it is believed that proto-Thracians descended from a purported mixture of Proto-Indo-Europeans and Early European Farmers, arriving from the rest of Asia and Africa through the Asia Minor (Anatolia). The proto-Thracian culture developed into the Dacian,

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area between northern Greece, southern Russia, and north-western Turkey. They shared the same language and culture... There may have been as many as a million Thracians, diveded among up to 40 tribes." Thracians resided mainly in the Balkans (mostly modern day Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece) but were also located in Anatolia (Asia Minor) and other locations in Eastern Europe.

The exact origin of Thracians is unknown, but it is believed that proto-Thracians descended from a purported mixture of Proto-Indo-Europeans and Early European Farmers, arriving from the rest of Asia and Africa through the Asia Minor (Anatolia). The proto-Thracian culture developed into the Dacian,

The origins of the Thracians remain obscure, in the absence of written historical records before they got into contact with the Greeks. Evidence of proto-Thracians in the prehistoric period depends on artifacts of

The origins of the Thracians remain obscure, in the absence of written historical records before they got into contact with the Greeks. Evidence of proto-Thracians in the prehistoric period depends on artifacts of

Divided into separate tribes, the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until the Odrysian state was founded in the fifth century BC. A strong Dacian state appeared in the first century BC, during the reign of King Burebista. The mountainous regions were home to various peoples, including the Illyrians, regarded as warlike and ferocious Thracian tribes, while the plains peoples were apparently regarded as more peaceable. The most prominent tribe, the

Divided into separate tribes, the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until the Odrysian state was founded in the fifth century BC. A strong Dacian state appeared in the first century BC, during the reign of King Burebista. The mountainous regions were home to various peoples, including the Illyrians, regarded as warlike and ferocious Thracian tribes, while the plains peoples were apparently regarded as more peaceable. The most prominent tribe, the

In the 6th century BC the Persian

In the 6th century BC the Persian

The conquest of the southern part of Thrace by Philip II of Macedon in the fourth century BC made the Odrysian kingdom extinct for several years. After the kingdom was reestablished, it was a vassal state of Macedon for several decades under generals such as

The conquest of the southern part of Thrace by Philip II of Macedon in the fourth century BC made the Odrysian kingdom extinct for several years. After the kingdom was reestablished, it was a vassal state of Macedon for several decades under generals such as

The next century and a half saw the slow development of Thracia into a permanent Roman client state. The

The next century and a half saw the slow development of Thracia into a permanent Roman client state. The

Clearchus

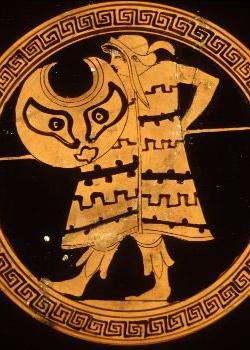

The Thracians were a warrior people, known as both horsemen and lightly armed skirmishers with javelins. Thracian peltasts had a notable influence in Ancient Greece.

The history of Thracian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Thrace. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Thracian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans and in the Dacian territories. Emperor Traianus, also known as Trajan, conquered Dacia after two wars in the 2nd century AD. The wars ended with the occupation of the fortress of Sarmisegetusa and the death of the king Decebalus. Besides conflicts between Thracians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Thracian tribes too.

The Thracians were a warrior people, known as both horsemen and lightly armed skirmishers with javelins. Thracian peltasts had a notable influence in Ancient Greece.

The history of Thracian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Thrace. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Thracian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans and in the Dacian territories. Emperor Traianus, also known as Trajan, conquered Dacia after two wars in the 2nd century AD. The wars ended with the occupation of the fortress of Sarmisegetusa and the death of the king Decebalus. Besides conflicts between Thracians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Thracian tribes too.

Several Thracian graves or tombstones have the name ''Rufus'' inscribed on them, meaning "redhead" – a common name given to people with

Several Thracian graves or tombstones have the name ''Rufus'' inscribed on them, meaning "redhead" – a common name given to people with  Nevertheless, academic studies have concluded that people often had different physical features from those described by primary sources. Ancient authors described as red-haired several groups of people. They claimed that all Slavs had red hair, and likewise described the Scythians as red haired. According to Beth Cohen, Thracians had "the same dark hair and the same facial features as the Ancient Greeks." However, Aris N. Poulianos states that Thracians, like modern Bulgarians, belonged mainly to the Aegean anthropological type.

Nevertheless, academic studies have concluded that people often had different physical features from those described by primary sources. Ancient authors described as red-haired several groups of people. They claimed that all Slavs had red hair, and likewise described the Scythians as red haired. According to Beth Cohen, Thracians had "the same dark hair and the same facial features as the Ancient Greeks." However, Aris N. Poulianos states that Thracians, like modern Bulgarians, belonged mainly to the Aegean anthropological type.

File:ThracianTribes.jpg, Thracian tribes and heroes.

File:Map Macedonia 336 BC-en.svg, Map of the territory of Philip II of Macedon.

File:Diadochen1.png, Kingdom of Lysimachus and the Diadochi.

File:Helmet of Cotofenesti - Front Large by Radu Oltean.jpg, Golden Dacian helmet of Cotofenesti, in Romania.

File:Koson 79000126.jpg, Gold coins that have been minted by the Dacians, with the legend ΚΟΣΩΝ.

File:Dioecesis Thraciae 400 AD.png, Map of the Diocese of Thrace (Dioecesis Thraciae) c. 400 AD.

File:Thracian Horseman Histria Museum.jpg, Thracian Roman era "heros" ( Sabazius)

ISBN 978-80-7671-069-6 (online: pdf)

*

Thrace and the Thracians (700 BC to 46 AD) Ancient Thracians. Art, Culture, History, TreasuresInformation on Ancient Thracevideo about the Thracians and Thracian warfare

{{Thracians Ancient tribes in Bulgaria Ancient tribes in Macedonia Ancient tribes in Romania Ancient tribes in the Balkans Indo-European peoples

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area between northern Greece, southern Russia, and north-western Turkey. They shared the same language and culture... There may have been as many as a million Thracians, diveded among up to 40 tribes." Thracians resided mainly in the Balkans (mostly modern day Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece) but were also located in Anatolia (Asia Minor) and other locations in Eastern Europe.

The exact origin of Thracians is unknown, but it is believed that proto-Thracians descended from a purported mixture of Proto-Indo-Europeans and Early European Farmers, arriving from the rest of Asia and Africa through the Asia Minor (Anatolia). The proto-Thracian culture developed into the Dacian,

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area between northern Greece, southern Russia, and north-western Turkey. They shared the same language and culture... There may have been as many as a million Thracians, diveded among up to 40 tribes." Thracians resided mainly in the Balkans (mostly modern day Bulgaria, Turkey and Greece) but were also located in Anatolia (Asia Minor) and other locations in Eastern Europe.

The exact origin of Thracians is unknown, but it is believed that proto-Thracians descended from a purported mixture of Proto-Indo-Europeans and Early European Farmers, arriving from the rest of Asia and Africa through the Asia Minor (Anatolia). The proto-Thracian culture developed into the Dacian, Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

, and several other smaller Thracian cultures.

Thracian culture was described as tribal by the Greeks and Romans. They remained largely disunited, with their first permanent state being the Odrysian kingdom in the fifth century BC. They faced subjugation by the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

around the same time. Thracians experienced a short period of peace after the Persians were defeated by the Greeks in the Persian Wars. The Odrysian kingdom lost independence to Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

in the late 4th century BC, and never regained total independence following Alexander the Great's death.

The Thracians faced conquest by the Romans in the mid second century BC under whom they faced internal strife. They composed major parts of rebellions against the Romans along with the Macedonians until the Third Macedonian War. The last reported use of a Thracian language was by monks in the sixth century AD.

Thracians were described as " warlike" and " barbarians" by the Greeks and Romans and were favored as mercenaries. Ancient descriptions of a vicious people are disputed and archaeology has been used since the mid-twentieth century in southern Bulgaria to identify more about them. Both Romans and Greeks called them barbarians since they were neither Romans nor Greeks, and to the perceived backwardness of their culture. The perceived primitiveness may be related to their living simple lives in open villages. Some authors noted that even after the introduction of Latin they still kept their "barbarous" ways. While the Thracians were perceived as unsophisticated by their contemporaries, they reportedly "had in fact a fairly advanced culture that was especially noted for its poetry and music."

Thracians spoke the extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

Thracian language and shared a common culture. The Thracians made cultural interaction with the people surrounding them: Greeks, Persians, Scythians, Celts and later on Turks, but although they were indeed influenced by each of these cultures, this influence affected only the circles of the aristocratic elite, not Thracian culture as a whole. Among their customs was tattooing, common among both males and females. They followed a polytheistic religion

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the b ...

. The study of the Thracians is known as Thracology

Thracology ( bg, Тракология, Trakologiya; ro, Tracologie) is the scientific study of Ancient Thrace and Thracian antiquities and is a regional and thematic branch of the larger disciplines of ancient history and archaeology. A practition ...

.

Etymology

The first historical record of the Thracians is found in the '' Iliad'', where they are described as allies of the Trojans in the Trojan War against the Ancient Greeks. Theethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and used ...

''Thracian'' comes from Ancient Greek Θρᾷξ (plural Θρᾷκες; , ) or Θρᾴκιος (; Ionic: Θρηίκιος, ), and the toponym Thrace comes from Θρᾴκη (; Ionic: Θρῄκη, ). These forms are all exonyms as applied by the Greeks.

Mythological foundation

In Greek mythology, '' Thrax'' (by his name simply the quintessential Thracian) was regarded as one of the reputed sons of the godAres

Ares (; grc, Ἄρης, ''Árēs'' ) is the Greek god of war and courage. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera. The Greeks were ambivalent towards him. He embodies the physical valor necessary for success in war b ...

. In the '' Alcestis'', Euripides mentions that one of the names of Ares himself was "Thrax" since he was regarded as the patron of Thrace (his golden or gilded shield was kept in his temple at Bistonia in Thrace).

Origins

material culture

Material culture is the aspect of social reality grounded in the objects and architecture that surround people. It includes the usage, consumption, creation, and trade of objects as well as the behaviors, norms, and rituals that the objects creat ...

. Leo Klejn identifies proto-Thracians with the multi-cordoned ware culture that was pushed away from Ukraine by the advancing timber grave culture or Srubnaya. It is generally proposed that a proto-Thracian people developed from a mixture of indigenous peoples and Indo-Europeans from the time of Proto-Indo-European expansion in the Early Bronze Age when the latter, around 1500 BC, mixed with indigenous peoples. According to one theory, their ancestors migrated in three waves from the northeast: the first in the Late Neolithic

In the archaeology of Southwest Asia, the Late Neolithic, also known as the Ceramic Neolithic or Pottery Neolithic, is the final part of the Neolithic period, following on from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic and preceding the Chalcolithic. It is some ...

, forcing out the Pelasgians

The name Pelasgians ( grc, Πελασγοί, ''Pelasgoí'', singular: Πελασγός, ''Pelasgós'') was used by classical Greek writers to refer either to the predecessors of the Greeks, or to all the inhabitants of Greece before the emergenc ...

and Achaeans, the second in the Early Bronze Age, and the third around 1200 BC. They reached the Aegean islands, ending the Mycenaean civilization. They did not speak the same language. During the Iron Age (about 1000 BC) Dacians

The Dacians (; la, Daci ; grc-gre, Δάκοι, Δάοι, Δάκαι) were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. They are often consid ...

and Thracians began developing from proto-Thracians. The diverse topography didn't make it possible for a single language to form.

Ancient Greek and Roman historians agreed that the ancient Thracians, who were of Indo-European stock and language, were superior fighters; only their constant political fragmentation prevented them from overrunning the lands around the northeastern Mediterranean. Although these historians characterized the Thracians as primitive partly because they lived in simple, open villages, the Thracians in fact had a fairly advanced culture that was especially noted for its poetry and music. Their soldiers were valued as mercenaries, particularly by the Macedonians and Romans.

Identity and distribution

Divided into separate tribes, the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until the Odrysian state was founded in the fifth century BC. A strong Dacian state appeared in the first century BC, during the reign of King Burebista. The mountainous regions were home to various peoples, including the Illyrians, regarded as warlike and ferocious Thracian tribes, while the plains peoples were apparently regarded as more peaceable. The most prominent tribe, the

Divided into separate tribes, the Thracians did not manage to form a lasting political organization until the Odrysian state was founded in the fifth century BC. A strong Dacian state appeared in the first century BC, during the reign of King Burebista. The mountainous regions were home to various peoples, including the Illyrians, regarded as warlike and ferocious Thracian tribes, while the plains peoples were apparently regarded as more peaceable. The most prominent tribe, the Moesians

In Roman literature of the early 1st century CE, the Moesi ( or ; grc, Μοισοί, ''Moisoí'' or Μυσοί, ''Mysoí''; lat, Moesi or ''Moesae'') appear as a Paleo-Balkan people who lived in the region around the River Timok to the south ...

only achieved importance under Roman rule.

Thracians inhabited parts of the ancient provinces of Thrace, Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

, Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

, Beotia, Attica, Dacia, Scythia Minor, Sarmatia, Bithynia

Bithynia (; Koine Greek: , ''Bithynía'') was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Pa ...

, Mysia, Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

, and other regions of the Balkans and Anatolia. This area extended over most of the Balkans region, and the Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

north of the Danube as far as beyond the Bug and including Pannonia in the west.

There were about 200 Thracian tribes.

Thucydides mentions about a period in the past (from his point), when Thracians have inhabited the region of Phocis, known also as the location of Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracle ...

; he defines it by the lifetime of Tereus

In Greek mythology, Tereus (; Ancient Greek: Τηρεύς) was a Thracian king,Thucydides: ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' 2:29 the son of Ares and the naiad Bistonis. He was the brother of Dryas. Tereus was the husband of the Athenian prin ...

– mythological Thracian king and son of god Ares

Ares (; grc, Ἄρης, ''Árēs'' ) is the Greek god of war and courage. He is one of the Twelve Olympians, and the son of Zeus and Hera. The Greeks were ambivalent towards him. He embodies the physical valor necessary for success in war b ...

.

History

Homeric period

The Thracians are mentioned in Homer's '' Iliad'', meaning that they were already present in the eighth century BC.Archaic period

The first Greek colonies along the Thracian coasts (first the Aegean, then the Marmara and Black Seas) were founded in the eighth century BC. Thracians and Greeks lived side-by-side. Ancient sources record a Thracian presence on the Aegean islands and in ''Hellas'' (the broader "land of the Hellenes"). At some point in the 7th century BC, a portion of the ThracianTreres Treri ( grc, Τρηροι, Trēroi, or , romanized: ; Latin: or ) is the name of a Thracian tribe.

In Thrace

The Treri lived in northwest Thrace, in the region of Serdica (now the Bulgarian capital city of Sofia). The Treri of the Serdica region w ...

tribe migrated across the Thracian Bosporus and invaded Anatolia. In 637 BC, the Treres under their king Kobos ( grc, Κώβος ; la, Cobus), in alliance with the Cimmerians and the Lycians, attacked the kingdom of Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

during the seventh year of the reign of the Lydian king Ardys. They defeated the Lydians and captured the capital city of Lydia, Sardis, except for its citadel, and Ardys might have been killed in this attack. Ardys's son and successor, Sadyattes

Sadyattes ( grc, Σαδυαττης, Saduattēs; la, Sadyattēs; reigned 637–) was the third king of the Mermnad dynasty in Lydia, the son of Ardys and the grandson of Gyges of Lydia. Sadyattes reigned 12 years according to Herodotus.

Reign ...

, might possibly also have been killed in another Cimmerian attack on Lydia. Soon after 635 BC, with Assyrian approval the Scythians under Madyes entered Anatolia. In alliance with Sadyattes's son, the Lydian king Alyattes, Madyes expelled the Treres from Asia Minor and defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat again, following which the Scythians extended their domination to Central Anatolia until they were themselves expelled by the Medes from Western Asia in the 600s BC.

Achaemenid Thrace

In the 6th century BC the Persian

In the 6th century BC the Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

conquered Thrace, starting in 513 BC, when the Achaemenid king Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

amassed an army and marched from Achaemenid-ruled Anatolia into Thrace, and from there he crossed the Arteskos river and then proceeded through the valley-route of the Hebros

Maritsa or Maritza ( bg, Марица ), also known as Meriç ( tr, Meriç ) and Evros ( ell, Έβρος ), is a river that runs through the Balkans in Southeast Europe. With a length of ,Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

who lived just south of the Danube river and who in vain attempted to resist the Achaemenid conquest. After the resistance of the Getae was defeated and they were forced to provide the Achaemenid army with soldiers, all the Thracian tribes between the Aegean Sea and the Danube river had been subjected by the Achaemenid Empire. Once Darius had reached the Danube, he crossed the river and campaigned against the Scythians, after which he returned back to Anatolia through Thrace and left a large army in Europe under the command of his general Megabazus

Megabazus (Old Persian: ''Bagavazdā'' or ''Bagabāzu'', grc, Μεγαβάζος), son of Megabates, was a highly regarded Persian general under Darius, to whom he was a first-degree cousin. Most of the information about Megabazus comes from ' ...

.

Following Darius I's orders to create a new satrapy for the Achaemenid Empire in the Balkans, Megabazus forced the Greek cities who had refused to submit to the Achaemenid Empire, starting with Perinthus, after which led military campaigns throughout Thrace to impose Achaemenid rule over every city and tribe in the area. With the help of Thracian guides, Megabazus was able to conquer Paeonia up to but not including the area of Lake Prasias, and he gave the lands of the Paeonians inhabiting these regions up to the Lake Prasias to Thracians loyal to the Achaemenid Empire. The last endeavours of Megabazus included his the conquest of the area between the Strymon and Axius rivers, and at the end of his campaign, the king of Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

, Amyntas I

Amyntas I (Greek: Ἀμύντας Aʹ; 498 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (c. 547 – 512 / 511 BC) and then a vassal of Darius I from 512/511 to his death 498 BC, at the time of Achaemenid Macedonia. He was a son of Alce ...

, accepted to become a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. Within the satrapy itself, the Achaemenid king Darius granted to the tyrant Histiaeus of Miletus

Miletus (; gr, Μῑ́λητος, Mī́lētos; Hittite transcription ''Millawanda'' or ''Milawata'' (exonyms); la, Mīlētus; tr, Milet) was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in a ...

the district of Myrcinus on the Strymon's east bank until Megabazus persuaded him to recall Histiaeus after he returned to Asia Minor, after which the Thracian tribe of the Edoni retook control of Myrcinus. The new satrapy, once created, was named (), derived from Scythian the name , which was the self-designation of the Scythians who inhabited the northern parts of the satrapy. Once Megabazus had returned to Asia Minor, he was succeeded in by a governor whose name is unknown, and Darius appointed the general Otanes to oversee the administrative division of the Hellespont, which extended on both sides of the sea and included the Bosporus, the Propontis

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

, and the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

proper and its approaches. Otanes then proceeded to capture Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

, Chalcedon, Antandrus

Antandrus or Antandros ( grc, Ἄντανδρος) was an ancient Greek city on the north side of the Gulf of Adramyttium in the Troad region of Anatolia. Its surrounding territory was known in Greek as (''Antandria''),Aristotle, ''Historia Anim ...

, Lamponeia

Lamponeia ( grc, Λαμπώνεια) or Lamponia (Λαμπωνία), also known as Lamponium or Lamponion (Λαμπώνιον), was an Aetolian city on the southern coast of the Troad region of Anatolia. Its archaeological remains have been located ...

, Imbros, and Lemnos for the Achaemenid Empire.

The area included within the satrapy of included both the Aegean coast of Thrace, as well as its Pontic coast till the Danube. In the interior, the Western border of the satrapy consisted of the Axius river and the Belasica- Pirin-Rila

Rila ( bg, Рила, ) is the highest mountain range of Bulgaria, the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula and Southeast Europe. It is situated in southwestern Bulgaria and forms part of the Rila–Rhodope Mountains, Rhodope Massif. The highest summit is Mus ...

mountain ranges till the site of modern-day Kostenets

Kostenets ( bg, Костенец ) is a town in Sofia Province in southwestern Bulgaria, and the administrative centre of the Kostenets Municipality (which also contains a separate village of Kostenets). The town is situated at the foot of Rila ...

. The importance of this satrapy rested in that it contained the Hebros

Maritsa or Maritza ( bg, Марица ), also known as Meriç ( tr, Meriç ) and Evros ( ell, Έβρος ), is a river that runs through the Balkans in Southeast Europe. With a length of ,Doriscus

Doriscus ( grc-gre, Δορίσκος and Δωρίσκος, ''Dorískos'') was a settlement in ancient Thrace (modern-day Greece), on the northern shores of Aegean Sea, in a plain west of the river Hebrus. It was notable for remaining in Persian h ...

with the Aegean coast, as well as with the port-cities of Apollonia, Mesembria and Odessos on the Black Sea, and with the central Thracian plain, which gave this region an important strategic value. Persian sources describe the province as being populated by three groups: the ''Saka Paradraya'' ("Saka beyond the sea", the Persian term for all Scythian peoples to the north of the Caspian Caspian can refer to:

*The Caspian Sea

*The Caspian Depression, surrounding the northern part of the Caspian Sea

*The Caspians, the ancient people living near the Caspian Sea

*Caspian languages, collection of languages and dialects of Caspian peopl ...

and Black Seas ); the themselves (most likely the Thracian tribes), and ''Yauna Takabara''. The latter term, which translates as " Ionians with shield-like hats", is believed to refer to Macedonians. The three ethnicities (Saka, Macedonian, Thracian) enrolled in the Achaemenid army, as shown in the Imperial tomb reliefs of Naqsh-e Rostam

Naqsh-e Rostam ( lit. mural of Rostam, fa, نقش رستم ) is an ancient archeological site and necropolis located about 12 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran. A collection of ancient Iranian rock reliefs are cut into the ...

, and participated in the Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion ...

on the Achaemenid side.

When Achaemenid control over its European possessions collapsed once the Ionian Revolt started, the Thracians did not help the Greek rebels, and they instead saw Achaemenid rule as more favourable because the latter had treated the Thracians with favour and even given them more land, and also because they realised that Achaemenid rule was a bulwark against Greek expansion and Scythian attacks. During the revolt, Aristagoras of Miletus captured Myrcinus from the Edones and died trying to attack another Thracian city.

Once the Ionian Revolt had been fully quelled, the Achaemenid general Mardonius crossed the Hellespont with a large fleet and army, re-subjugated Thrace without any effort and made Macedonia full part of the satrapy of . Mardonius was however attacked at night by the Bryges in the area of Lake Doiran

Doiran Lake (, ''Dojransko Ezero''; , ''Límni Dhoïráni''), also spelled Dojran Lake is a lake with an area of shared between North Macedonia () and Greece ().

To the west is the city of Nov Dojran (Нов Дојран), to the east the villa ...

and modern-day Valandovo, but he was able to defeat and submit them as well. Herodotus's list of tribes who provided the Achaemenid army with soldiers included Thracians from both the coast and from the central Thracian plain, attesting that Mardonius's campaign had reconquered all the Thracian areas which were under Achaemenid rule before the Ionian Revolt.

When the Greeks defeated a second invasion attempt by the Persian Empire in 479 BC, they started attacking the satrapy of , which was resisted by both the Thracians and the Persian forces. The Thracians kept on sending supplies to the governor of Eion when the Greeks besieged it. When the city fell to the Greeks in 475 BC, Cimon

Cimon or Kimon ( grc-gre, Κίμων; – 450BC) was an Athenian ''strategos'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Batt ...

gave its land to Athens for colonisation. Although Athens was now in control of the Aegean Sea and the Hellespont following the defeat of the Persian invasion, the Persians were still able to control the southern coast of Thrace from a base in central Thrace and with the support of the Thracians. Thanks to the Thracians co-operating with the Persians by sending supplies and military reinforcements down the Hebrus river route, Achaemenid authority in central Thrace lasted until around 465 BC, and the governor Mascames

Mascames, also spelled Maskames ( Old Persian: ''Maškāma'') was a Persian official and military commander, who flourished during the reign of Xerxes I (486–465). He was the son of Megadostes, and was appointed governor of Doriscus in 480 BC b ...

managed to resist many Greek attacks in Doriscus until then.

Around this time, Teres I, the king of the Odrysae tribe, in whose territory the Hebrus flowed, was starting to organise the rise of his kingdom into a powerful state. With the end of Achaemenid power in the Balkans, the Thracian Odrysian kingdom, the kingdom of Macedonia

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

, and the Athenian thalassocracy filled the ensuing power vacuum and formed their own spheres of influence in the area.

Odrysian Kingdom

The Odrysian Kingdom was a state union of over 40 Thracian tribes and 22 kingdoms that existed between the 5th century BC and the 1st century AD. It consisted mainly of present-day Bulgaria, spreading to parts of Southeastern Romania (Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( ro, Dobrogea de Nord or simply ; bg, Северна Добруджа, ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube river and the Black Sea, bordered in the south ...

), parts of Northern Greece and parts of modern-day European Turkey.

By the fifth century BC, the Thracian population was large enough that Herodotus called them the second-most numerous people in the part of the world known by him (after the Indians), and potentially the most powerful, if not for their lack of unity. The Thracians in classical times were broken up into a large number of groups and tribes, though a number of powerful Thracian states were organized, the most important being the Odrysian kingdom of Thrace, and also the short lived Dacian kingdom of Burebista. The '' peltast'', a type of soldier of this period, probably originated in Thrace.

During this period, a subculture of celibate

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, th ...

ascetics

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

called the "ctistae The Ctistae or Ktistai ( el, κτίσται) were a group/class among the Mysians of ancient Thracian culture.

The Mysians avoided consuming any living thing, and therefore lived on such foodstuffs as milk and honey. For this reason, they were refe ...

" lived in Thrace, where they served as philosophers, priests and prophets.

Macedonian Thrace

During this period, contacts between the Thracians andClassical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in Ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Marti ...

intensified.

After the Persians withdrew from Europe and before the expansion of the Kingdom of Macedon, Thrace was divided into three regions (east, central, and west). A notable ruler of the East Thracians was Cersobleptes Cersobleptes ( el, Kερσoβλέπτης, Kersobleptēs, also found in the form Cersebleptes, Kersebleptēs), was son of Cotys I (Odrysian), Cotys I, king of the Odrysian kingdom, Odrysians in Thrace, on whose death in September 360 BC he inherited ...

, who attempted to expand his authority over many of the Thracian tribes. He was eventually defeated by the Macedonians.

The Thracians were typically not city-builders and their only polis was Seuthopolis.

The conquest of the southern part of Thrace by Philip II of Macedon in the fourth century BC made the Odrysian kingdom extinct for several years. After the kingdom was reestablished, it was a vassal state of Macedon for several decades under generals such as

The conquest of the southern part of Thrace by Philip II of Macedon in the fourth century BC made the Odrysian kingdom extinct for several years. After the kingdom was reestablished, it was a vassal state of Macedon for several decades under generals such as Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Early life and career

Lysimachus was b ...

of the Diadochi.

In 279 BC, Celtic Gauls advanced into Macedonia, southern Greece and Thrace. They were soon forced out of Macedonia and southern Greece, but they remained in Thrace until the end of the third century BC. From Thrace, three Celtic tribes advanced into Anatolia and established the kingdom of Galatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (c ...

.

In western parts of Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

, Celts ( Scordisci) and Thracians lived alongside each other, as evident from the archaeological findings of pits and treasures, spanning from the third century BC to the first century BC.

Roman Thrace

During the Macedonian Wars, conflict between Rome and Thrace was unavoidable. The rulers of Macedonia were weak, and Thracian tribal authority resurged. But after theBattle of Pydna

The Battle of Pydna took place in 168 BC between Rome and Macedon during the Third Macedonian War. The battle saw the further ascendancy of Rome in the Hellenistic world and the end of the Antigonid line of kings, whose power traced back to ...

in 168 BC, Roman authority over Macedonia seemed inevitable, and the governance of Thrace passed to Rome.

Initially, Thracians and Macedonians revolted against Roman rule. For example, the revolt of Andriscus, in 149 BC, drew the bulk of its support from Thrace. Incursions by local tribes into Macedonia continued for many years, though a few tribes, such as the Deneletae and the Bessi, willingly allied with Rome.

After the Third Macedonian War, Thrace acknowledged Roman authority. The client state of Thracia comprised several tribes.

Roman rule

The next century and a half saw the slow development of Thracia into a permanent Roman client state. The

The next century and a half saw the slow development of Thracia into a permanent Roman client state. The Sapaei

Sapaeans, Sapaei or Sapaioi (Ancient Greek, "Σαπαίοι") were a Thracian tribe close to the Greek city of Abdera, Thrace, Abdera. One of their kings was named Abrupolis

and had allied himself with the Ancient Rome, Romans. They Sapaean kingdo ...

tribe came to the forefront initially under the rule of Rhascuporis. He was known to have granted assistance to both Pompey and Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

, and later supported the Republican armies against Mark Antony and Octavian in the final days of the Republic.

The heirs of Rhascuporis became as deeply enmeshed in political scandal and murder as were their Roman masters. A series of royal assassinations altered the ruling landscape for several years in the early Roman imperial period. Various factions took control with the support of the Roman Emperor. The turmoil would eventually end with one final assassination.

After Rhoemetalces III of the Thracian Kingdom of Sapes was murdered in AD 46 by his wife, Thracia was incorporated as an official Roman province to be governed by Procurators, and later Praetorian prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

s. The central governing authority of Rome was in Perinthus, but regions within the province were under the command of military subordinates to the governor. The lack of large urban centers made Thracia a difficult place to manage, but eventually the province flourished under Roman rule. However, Romanization was not attempted in the province of Thracia. The '' Balkan Sprachbund'' does not support Hellenization.

Roman authority in Thracia rested mainly with the legions stationed in Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

. The rural nature of Thracia's populations, and distance from Roman authority, certainly inspired local troops to support Moesia's legions. Over the next few centuries, the province was periodically and increasingly attacked by migrating Germanic tribes. The reign of Justinian saw the construction of over 100 legionary

The Roman legionary (in Latin ''legionarius'', plural ''legionarii'') was a professional heavy infantryman of the Roman army after the Marian reforms. These soldiers would conquer and defend the territories of ancient Rome during the late Republi ...

fortresses to supplement the defense.

Barbarians

Thracians were regarded by other peoples as warlike, ferocious, bloodthirsty, and barbarian. They were seen as "barbarians" by ancient Greeks and Romans. Plato in his ''Republic'' groups them with the Scythians, calling them extravagant and high spirited; and his ''Laws'' portrays them as a warlike nation, grouping them with Celts, Persians, Scythians, Iberians and Carthaginians.Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

wrote of Cotys's sober and gentle character being unlike that of most Thracians. Tacitus in his ''Annals'' writes of them being wild, savage and impatient, disobedient even to their own kings. The Thracians have been said to have "tattooed their bodies, obtained their wives by purchase, and often sold their children." Victor Duruy

Jean Victor Duruy (10 September 1811 – 25 November 1894) was a French historian and statesman.

Life

Duruy was born in Paris, the son of a factory worker, and at first intended for his father's trade. Having passed brilliantly through the Éc ...

further notes that they "considered husbandry unworthy of a warrior, and knew no source of gain but war and theft," and that they practiced human sacrifice, which has been confirmed by archaeological evidence.

Polyaenus and Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

write how the Thracians broke their pacts of truce

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state act ...

with trickery. The Thracians struck their weapons against each other before battle, "in the Thracian manner," as Polyaneus testifies.Polyaenus. ''Strategems''. Book 7Clearchus

Diegylis

Diegylis (Ancient Greek: Διήγυλις) was a chieftain of the Thracian Caeni tribe and father of Ziselmius. He is described by ancient sources (such as Diodorus Siculus) as extremely bloodthirsty.Diodorus Siculus, ''Bibliotheca historica'', ...

was considered one of the most bloodthirsty chieftains by Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

. An Athenian club for lawless youths was named after the Triballi.

According to ancient Roman sources, the Dii were responsible for the worst atrocities of the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

, killing every living thing, including children and dogs in Tanagra and Mycalessos. Thracians would impale Roman heads on their spears and rhomphaias such as in the Kallinikos Callinicus or Kallinikos ( el, Καλλίνικος) is a surname or male given name; the feminine form is Kalliniki, Callinice or Callinica ( el, Καλλινίκη). It is of Greek origin, meaning "beautiful victor".

People named Callinicus Seleu ...

skirmish at 171 BC.

Herodotus writes that "they sell their children and let their maidens commerce with whatever men they please".

The accuracy and impartiality of these descriptions have been called into question in modern times, given the seeming embellishments in Herodotus's histories, for one. Strabo treated the Thracians as barbarians, and held that they spoke the same language as the Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

. Archaeologists have attempted to piece together a fuller understanding of Thracian culture through study of their artifacts.

Aftermath and legacy

The ancient languages of these people and their cultural influence were highly reduced due to the repeated invasions of the Balkans by Romans, Celts, Huns, Goths, Scythians, Sarmatians andSlavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, accompanied by, hellenization, romanization and later slavicisation. However, the Thracians as a group only disappeared in the Early Middle Ages. Towards the end of the 4th century, Nicetas

Nicetas or Niketas () is a Greek given name, meaning "victorious one" (from Nike "victory").

The veneration of martyr saint Nicetas the Goth in the medieval period gave rise to the Slavic forms: ''Nikita, Mykyta and Mikita''

People with the name N ...

the Bishop of Remesiana brought the gospel to "those mountain wolves", the Bessi.Gottfried Schramm: A New Approach to Albanian History 1994 Reportedly his mission was successful, and the worship of Dionysus and other Thracian gods was eventually replaced by Christianity. In 570, Antoninus Placentius said that in the valleys of Mount Sinai there was a monastery in which the monks spoke Greek, Latin, Syriac, Egyptian and Bessian. The origin of the monasteries is explained in a medieval hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies migh ...

written by Simeon Metaphrastes

Symeon, called Metaphrastes or the Metaphrast (; ; died c. 1000), was a Byzantine writer and official. He is regarded as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and his feast day falls on 9 or 28 November.

He is best known for his 10-volume Gree ...

, in Vita Sancti Theodosii Coenobiarchae in which he wrote that Theodosius the Cenobiarch founded on the shore of the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

a monastery with four churches, in each being spoken a different language, among which Bessian was found. The place where the monasteries were founded was called "Cutila", which may be a Thracian name. The further fate of the Thracians is a matter of dispute. Gottfried Schramm derived the Albanians

The Albanians (; sq, Shqiptarët ) are an ethnic group and nation native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Se ...

from the Christian Bessi, or Bessians, an early Thracian people who were pushed westwards into Albania. However, from a linguistic point of view it emerges that the Thracian-Bessian hypothesis of the origin of Albanian should be rejected, since only very little comparative linguistic material is available (the Thracian is attested only marginally, while the Bessian is completely unknown), but at the same time the individual phonetic history of Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

and Thracian clearly indicates a very different sound development that cannot be considered as the result of one language. Furthermore, the Christian vocabulary of Albanian is mainly Latin, which speaks against the construct of a "Thracian-Bessian church language". Most probably the remnants of the Thracians were assimilated into the Roman and later in the Byzantine society and became part of the ancestral groups of the modern Southeastern Europeans.

Culture

Language

Religion

One notable cult that existed in Thrace,Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

and Scythia Minor was that of the " Thracian horseman", also known as the "Thracian Heros", at Odessos (near Varna) known by a Thracian name as Heros ''Karabazmos'', a god of the underworld, who was usually depicted on funeral statues as a horseman slaying a beast with a spear. Dacians had a monotheistic religion based on the god Zalmoxis. The supreme Balkan thunder god Perkon was part of the Thracian pantheon, although cults of Orpheus and Zalmoxis

Zalmoxis ( grc-gre, Ζάλμοξις) also known as Salmoxis (Σάλμοξις), Zalmoxes (Ζάλμοξες), Zamolxis (Ζάμολξις), Samolxis (Σάμολξις), Zamolxes (Ζάμολξες), or Zamolxe (Ζάμολξε) is a divinity of the ...

likely overshadowed his.

Some think that the Greek god Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

evolved from the Thracian god Sabazios

Sabazios ( grc, Σαβάζιος, translit=Sabázios, ''Savázios''; alternatively, ''Sabadios'') is the horseman and sky father god of the Phrygians and Thracians. Though the Greeks interpreted Phrygian Sabazios as both Zeus and Dionysus, rep ...

.

Marriage

The Thracians were polygamous.Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

puts it: "''All Thracians, especially us and the Getae

The Getae ( ) or Gets ( ; grc, Γέται, singular ) were a Thracian-related tribe that once inhabited the regions to either side of the Lower Danube, in what is today northern Bulgaria and southern Romania. Both the singular form ''Get'' an ...

, are not much abstaining, because no one takes less than ten, eleven, twelve wives, some even more. If one dies and has only four or five wives he is called ill-fated, unhappy and unmarried.''" According to Herodotus virginity among women was not valued, and unmarried Thracian women could have sex with any man they wished to. There were men perceived as holy Thracians, who lived without women and were called "ktisti". In myth Orpheus became attracted to men after the death of Eurydice and is thought of as the establisher of homosexuality among Thracian men. Because he advocated love between men and turning away from loving women he was killed by the Bistones

Bistones ( el, "Βίστονες") is the name of a Thracian people who dwelt between Mount Rhodopé and the Aegean Sea, beside Lake Bistonis, near Abdera "extending westward as far as the river Nestus". It was through the land of the Bistones ...

women.

Warfare

The Thracians were a warrior people, known as both horsemen and lightly armed skirmishers with javelins. Thracian peltasts had a notable influence in Ancient Greece.

The history of Thracian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Thrace. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Thracian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans and in the Dacian territories. Emperor Traianus, also known as Trajan, conquered Dacia after two wars in the 2nd century AD. The wars ended with the occupation of the fortress of Sarmisegetusa and the death of the king Decebalus. Besides conflicts between Thracians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Thracian tribes too.

The Thracians were a warrior people, known as both horsemen and lightly armed skirmishers with javelins. Thracian peltasts had a notable influence in Ancient Greece.

The history of Thracian warfare spans from c. 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Thrace. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Thracian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans and in the Dacian territories. Emperor Traianus, also known as Trajan, conquered Dacia after two wars in the 2nd century AD. The wars ended with the occupation of the fortress of Sarmisegetusa and the death of the king Decebalus. Besides conflicts between Thracians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Thracian tribes too.

Physical appearance

Several Thracian graves or tombstones have the name ''Rufus'' inscribed on them, meaning "redhead" – a common name given to people with

Several Thracian graves or tombstones have the name ''Rufus'' inscribed on them, meaning "redhead" – a common name given to people with red hair

Red hair (also known as orange hair and ginger hair) is a hair color found in one to two percent of the human population, appearing with greater frequency (two to six percent) among people of Northern or Northwestern European ancestry and ...

which led to associating the name with slaves when the Romans enslaved this particular group. Ancient Greek artwork often depicts Thracians as redheads. Rhesus of Thrace, a mythological Thracian king, was so named because of his red hair and is depicted on Greek pottery as having red hair and a red beard.

Ancient Greek writers also described the Thracians as red-haired. A fragment by the Greek poet Xenophanes describes the Thracians as blue-eyed and red haired:

Bacchylides described Theseus as wearing a hat with red hair, which classicists believe was Thracian in origin. Other ancient writers who described the hair of the Thracians as red include Hecataeus of Miletus

Hecataeus of Miletus (; el, Ἑκαταῖος ὁ Μιλήσιος; c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC), son of Hegesander, was an early Greek historian and geographer.

Biography

Hailing from a very wealthy family, he lived in Miletus, then under Per ...

, Galen, Clement of Alexandria, and Julius Firmicus Maternus

__NOTOC__

Julius Firmicus Maternus was a Roman Latin writer and astrologer, who received a pagan classical education that made him conversant with Greek; he lived in the reign of Constantine I (306 to 337 AD) and his successors. His triple career m ...

.

Notable people

This is a list of historically important personalities being entirely or partly of Thracian ancestry: * Orpheus, mythological figure considered chief among poets and musicians; king of the Thracian tribe of Cicones * Spartacus, Thracian gladiator who led a large slave uprising in Southern Italy in 73–71 BC and defeated several Roman legions in what is known as the Third Servile War * Amadocus, Thracian King, theAmadok Point

Amadok Point (Nos Amadok \'nos a-ma-'dok\) is a point on the south coast of Livingston Island, Antarctica which projects 400 m into the Bransfield Strait. The point was named after the Thracian King Amadokos, 415-384 BC. It is snow-free in the ...

was named after him

* Teres I, Thracian King who united many tribes of Thrace under the banner of the Odrysian state

* Seuthes I

*Seuthes II Seuthes II ( grc, Σεύθης, ''Seuthēs'') was a ruler in the Odrysian kingdom of Thrace, attested from 405 to 387 BC. While he looms large in the historical narrative thanks to his close collaboration with Xenophon, most scholars consider Seuthe ...

* Seuthes III

* Rhesus of Thrace

* Cotys I

*Sitalces

Sitalces (Sitalkes) (; Ancient Greek: Σιτάλκης, reigned 431–424 BC) was one of the great kings of the Thracian Odrysian state. The Suda called him Sitalcus (Σίταλκος).

He was the son of Teres I, and on the sudden death o ...

, King of the Odrysian state; an ally of the Athenians

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

during the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

* Burebista, King of Dacia

* Decebalus, King of Dacia

* Maximinus Thrax, Roman Emperor from 235 to 238.

*Aureolus

Aureolus was a Roman military commander during the reign of Emperor Gallienus before he attempted to usurp the Roman Empire. After turning against Gallienus, Aureolus was killed during the political turmoil that surrounded the Emperor's assassina ...

, Roman military commander

* Galerius, Roman Emperor from 305 to 311; born to a Thracian father and Dacian mother

* Licinius, Roman Emperor from 308 to 324

* Maximinus Daia or Maximinus Daza, Roman Emperor from 308 to 313

* Justin I, Eastern Roman Emperor and founder of the Justinian dynasty

The Byzantine Empire had its first golden age under the Justinian dynasty, which began in 518 AD with the accession of Justin I. Under the Justinian dynasty, particularly the reign of Justinian I, the empire reached its greatest territorial exte ...

* Justinian the Great, Eastern Roman Emperor; either Illyrian or Thracian, born in Dardania

* Belisarius, Eastern Roman general of reputed Illyrian or Thracian origin

*Marcian

Marcian (; la, Marcianus, link=no; grc-gre, Μαρκιανός, link=no ; 392 – 27 January 457) was Roman emperor of the East from 450 to 457. Very little of his life before becoming emperor is known, other than that he was a (personal as ...

, Eastern Roman Emperor from 450 to 457; either Illyrian or Thracian

* Leo I the Thracian, Eastern Roman Emperor from 457 to 474

* Bouzes or Buzes, Eastern Roman general active during the reign of Justinian the Great (r. 527–565)

* Coutzes or Cutzes, general of the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Emperor Justinian I

Thracology

Archaeology

The branch of science that studies the ancient Thracians and Thrace is calledThracology

Thracology ( bg, Тракология, Trakologiya; ro, Tracologie) is the scientific study of Ancient Thrace and Thracian antiquities and is a regional and thematic branch of the larger disciplines of ancient history and archaeology. A practition ...

. Archaeological research on the Thracian culture

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. ...

started in the 20th century, especially after World War II, mainly in

southern Bulgaria. As a result of intensive excavations in the 1960s and 1970s a number of Thracian tombs and sanctuaries were discovered. Most significant among them are: the Tomb of Sveshtari, the Tomb of Kazanlak, Tatul, Seuthopolis, Perperikon the Tomb of Aleksandrovo in Bulgaria and Sarmizegetusa in Romania and others.

Also a large number of elaborately crafted gold and silver treasure sets from the 5th and 4th century BC were unearthed. In the following decades, those were exhibited in museums around the world, thus calling attention to ancient Thracian culture. Since the year 2000, Bulgarian archaeologist Georgi Kitov has made discoveries in Central Bulgaria, in an area now known as "The Valley of the Thracian Kings". The residence of the Odrysian kings was found in Starosel

Starosel ( bg, Старосел) is a village in central Bulgaria, Hisarya Municipality, Plovdiv Province. It lies at the foot of the Sredna Gora mountain range along the shores of Pyasachnik River.

Starosel is known for the abundance of ...

in the Sredna Gora mountains. A 1922 Bulgarian study claimed that there were at least 6,269 necropolis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually im ...

es in Bulgaria.

*Panagyurishte Treasure

The Panagyurishte Treasure ( bg, Панагюрско златно съкровище) is a Thracian treasure.

Discovery

It was accidentally discovered on 8 December 1949 by three brothers, Pavel, Petko, and Michail Deikov, who worked togethe ...

* Rogozen Treasure

* Valchitran Treasure

*Borovo Treasure

The Borovo Treasure, also known as the Borovo Silver Treasure, is a Thracian hoard of five matching silver-gilt items discovered in late 1974 while ploughing a field in Borovo, Bulgaria.

The treasure is kept in the history museum at Ruse.

Item ...

Genetics

A genetic study published in ''Scientific Reports

''Scientific Reports'' is a peer-reviewed open-access scientific mega journal published by Nature Portfolio, covering all areas of the natural sciences. The journal was established in 2011. The journal states that their aim is to assess solely th ...

'' in April 2019 examined the mtDNA of 25 Thracian remains in Bulgaria from the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. They were found to harbor a mixture of ancestry from Western Steppe Herders (WSHs) and Early European Farmers (EEFs), supporting the idea that the Balkan region was a link between Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean.

Gallery

stele

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), whe ...

.

File:Bergaios thracian king.jpg, Coin of Bergaios

Bergaios or Bergaeus ( el, Βεργαῖος), 400 – 350 BC, was a Thracian king in the Pangaian region. He is known mainly from the several types of coins that he struck, which resemble those of Thasos. Bergaios could mean literally, 'a man fro ...

, a local Thracian king in the Pangaian District, Greece.

File:Thracian treasure NHM Bulgaria.JPG, A gold Thracian treasure from Panagyurishte, Bulgaria.

File:Shushmanets3.jpg, Thracian tomb Shushmanets

The Thracian tomb at Shushmanets is a mound located in the Valley of the Thracian Rulers. It was built as a temple in the 4th century BC and later used as a tomb.

Architecture

The temple has a long and wide entry corridor and an antechamber, ...

built in 4th century BC

File:Thomb-Sveshtari.jpg, The Thracian Tomb of Sveshtari

File:Thomb-Sveshtari-2.jpg, The interior of the Sveshtari tomb

File:Kazanluk 1.jpg, Thracian Tomb of Kazanlak

File:National Archaeological Museum Sofia - Bronze Head from the Golyama Kosmatka Tumulus near Shipka.jpg, Bronze head of Seuthes III

File:The Thracian tomb Goliama Kosmatka, Bulgaria 01.jpg, Tomb of Seuthes III

File:SeuthIIIHeroon SM.jpg, Interior of Tomb of Seuthes III

See also

*Akrokomai

Akrokomai, Akrokomoi (Ancient Greek, Ακρόκομοι) an epithet given to certain Thracians by Greeks due to their hair arrangement.The Cambridge ancient history - page 614, by John Boardman,, - 1991 - "and Archilochus (Diehl 793) call the Thrac ...

* Andronovo culture

The Andronovo culture (russian: Андроновская культура, translit=Andronovskaya kul'tura) is a collection of similar local Late Bronze Age cultures that flourished 2000–1450 BC,Grigoriev, Stanislav, (2021)"Andronovo ...

* Bosporan Kingdom

* Cimmerians

* Dacia and Dacians

The Dacians (; la, Daci ; grc-gre, Δάκοι, Δάοι, Δάκαι) were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. They are often consid ...

* Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

and Illyrians

* List of rulers of Thrace and Dacia

* List of Thracian tribes

* List of ancient Daco-Thracian peoples and tribes

* Odrysian kingdom

* Orphism (religion)

* Paeonia (kingdom)

* Scythians

* Thracian warfare

The history of Thracian warfare spans from the 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Thrace. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Thracian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkan ...

* Thraco-Cimmerian

Thraco-Cimmerian is a historiographical and archaeological term, composed of the names of the Thracians and the Cimmerians. It refers to 8th to 7th century BC cultures that are linked in Eastern Central Europe and in the area west of the Black Se ...

* Thraco-Dacian

The linguistic classification of the ancient Thracian language has long been a matter of contention and uncertainty, and there are widely varying hypotheses regarding its position among other Paleo-Balkan languages. It is not contested, however, t ...

* Thraco-Illyrian

* Tiras

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * *Best, Jan and De Vries, Nanny. ''Thracians and Mycenaeans''. Boston, MA: E.J. Brill Academic Publishers, 1989. . * * * * * * *Further reading

* ''The Yurta-Stroyno Archaeological Project. Studies on the Roman Rural Settlement in Thrace''. P. Tušlová – B. Weissová – S. Bakardzhiev (eds.). Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts, 2022. ISBN 978-80-7671-068‑9 (print),External links

Thrace and the Thracians (700 BC to 46 AD)

{{Thracians Ancient tribes in Bulgaria Ancient tribes in Macedonia Ancient tribes in Romania Ancient tribes in the Balkans Indo-European peoples