Thomas G. W. Settle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Greenhow Williams "Tex" Settle (November 4, 1895 – April 28, 1980) was an officer of the

''New York Times'' April 22, 1934 and the Harmon National Trophy for 1932

''New York Times'' April 15, 1933 and 1933. He also set numerous distance and endurance records. In 1934 Settle transferred to sailing duties, initially as captain of the

Sergei Bortkiewicz

(1877-1952) in Yalta and Constantinople in 1920. As a gratitude for his help Bortkiewicz dedicated his piano cycle ''Der kleine Wanderer'' opus 21 to Settle. The nickname "Tex" dates back to his Academy years. After these assignment he attended the Cruft High Tension Laboratory of

On the day when ''Shenandoah'' crashed, Settle was training alone in a captive kite balloon. After the crash he volunteered for airship pilot training and received his Naval Aviator's (Airship)

On the day when ''Shenandoah'' crashed, Settle was training alone in a captive kite balloon. After the crash he volunteered for airship pilot training and received his Naval Aviator's (Airship)

Settle entered his first balloon race together with George N. Stevens on May 30, 1927. They had to ground their balloon due to heavy rain after only in flight, losing the race. This incident motivated Settle to seek all possible cooperation from Navy

Settle entered his first balloon race together with George N. Stevens on May 30, 1927. They had to ground their balloon due to heavy rain after only in flight, losing the race. This incident motivated Settle to seek all possible cooperation from Navy

For the next flight the

For the next flight the

On March 2, 1944, Settle arrived by airplane at his new command, , then stationed at

On March 2, 1944, Settle arrived by airplane at his new command, , then stationed at

"Why Explore The Stratosphere?"

''Popular Mechanics'', October 1933 {{DEFAULTSORT:Settle, Thomas G. W. 1895 births 1980 deaths People from Washington, D.C. United States Naval Academy alumni Naval War College alumni Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences alumni United States Naval Aviators American balloonists United States Navy admirals United States Navy World War II admirals Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Legion of Merit Flight altitude record holders Flight endurance record holders Balloon flight record holders American aviation record holders

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

who on November 20, 1933, together with Army major Chester L. Fordney, set a world altitude record in the ''Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositi ...

'' stratospheric

The stratosphere () is the second layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is an atmospheric layer composed of stratified temperature layers, with the warm layers of air hi ...

balloon

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and air. For special tasks, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), or light so ...

. An experienced balloonist, long-time flight instructor

A flight instructor is a person who teaches others to operate aircraft. Specific privileges granted to holders of a flight instructor qualification vary from country to country, but very generally, a flight instructor serves to enhance or evaluate ...

, and officer on the airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

s and , Settle won the Litchfield Trophy

Litchfield may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Litchfield Island, Palmer Archipelago

Australia

* Litchfield Municipality, Northern Territory

* Litchfield National Park, Northern Territory

* Litchfield Station, Northern Territory

Canada

* Litc ...

in 1929 and 1931, the International Gordon Bennett Race in 1932, the Harmon Aeronaut Trophy for 1933,Post and Settle Win Flying Prizes''New York Times'' April 22, 1934 and the Harmon National Trophy for 1932

''New York Times'' April 15, 1933 and 1933. He also set numerous distance and endurance records. In 1934 Settle transferred to sailing duties, initially as captain of the

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

-based . In 1944–1945 he commanded the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

, earning the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

for his action in the Battle of Surigao Strait

The Battle of Leyte Gulf ( fil, Labanan sa golpo ng Leyte, lit=Battle of Leyte gulf; ) was the largest naval battle of World War II and by some criteria the largest naval battle in history, with over 200,000 naval personnel involved. It was fou ...

. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Vice Admiral Settle held Navy appointments in the continental United States and overseas, and was charged with tasks ranging from distributing international aid

In international relations, aid (also known as international aid, overseas aid, foreign aid, economic aid or foreign assistance) is – from the perspective of governments – a voluntary transfer of resources from one country to another.

Ai ...

to Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

to conducting nuclear tests

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

in the Aleutian islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a cha ...

.

Early career

Settle graduated from theUnited States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

in 1918, second in his class, and began his naval career as an ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

on the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s , and . During his time as a naval officer in the Black Sea at the time of the Russian civil war Settle helped the Russian composeSergei Bortkiewicz

(1877-1952) in Yalta and Constantinople in 1920. As a gratitude for his help Bortkiewicz dedicated his piano cycle ''Der kleine Wanderer'' opus 21 to Settle. The nickname "Tex" dates back to his Academy years. After these assignment he attended the Cruft High Tension Laboratory of

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, graduating as a communications engineer in the summer of 1924.Vaeth, p. 35

Settle married Fay Brackett, an employee of Cruft Laboratory, in June 1924,Vaeth, p. 36 and in July assumed his next Navy assignment, that of communications officer on , a rigid, 207-meter airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

based at Lakehurst Naval Air Station

Lakehurst Maxfield Field, formerly known as Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst (NAES Lakehurst), is the naval component of Joint Base McGuire–Dix–Lakehurst (JB MDL), a United States Air Force-managed joint base headquartered approximately ...

. When the newly built arrived at Lakehurst later in October 1924, Settle was appointed its communications officer as well;Vaeth, p. 37 dual appointments were possible because helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

supplies allowed flying only one airship at a time.Vaeth, p. 38

Airship pilot

On the day when ''Shenandoah'' crashed, Settle was training alone in a captive kite balloon. After the crash he volunteered for airship pilot training and received his Naval Aviator's (Airship)

On the day when ''Shenandoah'' crashed, Settle was training alone in a captive kite balloon. After the crash he volunteered for airship pilot training and received his Naval Aviator's (Airship) wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expresse ...

No. 3350 on January 19, 1927.Althoff, p. 39 Settle also wanted to train as an airplane pilot, but Admiral Moffett declined his requests.Vaeth, p. 61 Soon he flew a small balloon for 21 hours over —a flight that could make a world distance record had it been equipped with a barograph

A barograph is a barometer that records the barometric pressure over time in graphical form. This instrument is also used to make a continuous recording of atmospheric pressure. The pressure-sensitive element, a partially evacuated metal cylinde ...

.

On August 25, 1927, when captain Charles E. Rosendahl

Charles Emery Rosendahl (May 15, 1892 – May 17, 1977) was a highly decorated vice admiral in the United States Navy, and an advocate of lighter-than-air flight.

Biography Early career

Rosendahl was born in Chicago, Illinois, although his ...

was on the ground, Settle happened be the senior officer on board ''Los Angeles'' when the airship, tied to a mooring mast, literally "stood on its nose". At 13:29 a sudden cold weather front

A weather front is a boundary separating air masses for which several characteristics differ, such as air density, wind, temperature, and humidity. Disturbed and unstable weather due to these differences often arises along the boundary. For in ...

hit ''Los Angeles''; the resulting increase in the buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the p ...

of the airship, warmed by sunlight, pushed it upward.Althoff, p. 96 The tail freely went up while the nose remained tied to the tower. Settle requested Rosendahl's permission to disengage from the tower, but the captain "saw no need for it".Vaeth, p. 42 Winds threw the tail further upward; Settle sent the men into the tail, but ''Los Angeles'' kept rising until reaching a nearly vertical (88 degrees) nose-down position. The airship slowly rotated back; Settle called his men back and released aft balance, saving ''Los Angeles'' from a tail-first impact. ''Los Angeles'' survived the accident and served until 1932, performing 331 flights without major accidents or fatalities.

Test pilot

Later Settle piloted different types of airships stationed at Lakehurst. In January 1928 Settle nearly drowned at sea when his J-3 non-rigid airship carrying trainee pilots lost power and was swept into the Atlantic; the crew managed to restart the engines and reach Lakehurst. As a flight instructor, Settle—although an aviator himself—was known for merciless airborne training drills and advocated abolition of flight pay incentives, convinced that they attracted "deadwood" intonaval aviation

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft carrier. Carrier-based a ...

. In October 1928 Settle crossed the Atlantic on board '' Graf Zeppelin'' together with two other Navy observers. Inspired by the reliability of German airships, he publicly denounced United States dependence on German Maybach

Maybach (, ) is a Automotive industry in Germany, German luxury car brand that exists today as a part of Mercedes-Benz. The original company was founded in 1909 by Wilhelm Maybach and his son Karl Maybach, originally as a subsidiary of ''Lufts ...

engines.

Settle spent the first half of 1929 in the Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County, Ohio, Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 C ...

hangars of Goodyear-Zeppelin

Goodyear Aerospace Corporation (GAC) was the aerospace and defense subsidiary of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. The company was originally operated as a division within Goodyear as the Goodyear Zeppelin Corporation, part of a joint project ...

, supervising construction of the future and , threatened by saboteurs

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

. In 1930 he tested captive sailplane

A glider or sailplane is a type of glider aircraft used in the leisure activity and sport of gliding (also called soaring). This unpowered aircraft can use naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmosphere to gain altitude. Sailplan ...

s carried by ''Los Angeles'', where he remained the second in command. In 1931 Settle became the first pilot of ''K-1'', the first U. S. Navy non-rigid airship with an internally suspended control car, and the first using propane

Propane () is a three-carbon alkane with the molecular formula . It is a gas at standard temperature and pressure, but compressible to a transportable liquid. A by-product of natural gas processing and petroleum refining, it is commonly used a ...

as engine fuel.Grossnick, p. 34 ''K-1'' remained the sole specimen of its type; the Navy considered it too large for its tasks.

Balloon races

Settle entered his first balloon race together with George N. Stevens on May 30, 1927. They had to ground their balloon due to heavy rain after only in flight, losing the race. This incident motivated Settle to seek all possible cooperation from Navy

Settle entered his first balloon race together with George N. Stevens on May 30, 1927. They had to ground their balloon due to heavy rain after only in flight, losing the race. This incident motivated Settle to seek all possible cooperation from Navy meteorologist

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists in research, while t ...

s in the future. Settle became the definitive Navy competitor in national and, when qualified, international gas balloon races:

* In May 1928 Settle withdrew early from the National Race in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, where lightning strike

A lightning strike or lightning bolt is an electric discharge between the atmosphere and the ground. Most originate in a cumulonimbus cloud and terminate on the ground, called cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning. A less common type of strike, ground- ...

s downed three balloons, killing two pilots and injuring four.

* In May 1929 Settle and ensign Wilfred Bushnell competed at the National Race, winning the Litchfield Trophy

Litchfield may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Litchfield Island, Palmer Archipelago

Australia

* Litchfield Municipality, Northern Territory

* Litchfield National Park, Northern Territory

* Litchfield Station, Northern Territory

Canada

* Litc ...

with a flight which set a world record in three balloon categories and qualified them for the International Balloon Race.

* In July 1931 Settle and Bushnell (now lieutenant) won their second Litchfield Trophy.

* In September 1932 Settle and Bushnell won the International Gordon Bennett Race with a record flight from Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

to Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

. The flight earned Settle his first national Harmon Trophy

The Harmon Trophy is a set of three international trophies, to be awarded annually to the world's outstanding aviator, aviatrix, and aeronaut (balloon or dirigible). A fourth trophy, the "National Trophy," was awarded from 1926 through 1938 to t ...

.

* In September 1933 Settle and lieutenant Kendall made a flight, setting a world endurance record but only coming second in the International Gordon Bennett Race, losing in distance to the Polish team of Franciszek Hynek Franciszek () is a masculine given name of Polish origin (female form Franciszka). It is a cognate of Francis, Francisco, François, and Franz. People with the name include:

*Edward Pfeiffer (Franciszek Edward Pfeiffer) (1895–1964), Polish ge ...

and Zbigniew Burzyński

Zbigniew Jan Władysław Antoni Burzyński (31 March 1902 in Zhovkva, pl, Żółkiew near Lwów – 30 December 1971 in Warsaw), was a Polish balloonist and constructor of balloons, pioneer of Polish balloons, who twice won the Gordon Bennett C ...

.

''Century of Progress''

In 1932 the board of theCentury of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositi ...

trade show, to be held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

in summer 1933, invited renowned Swiss balloonist Auguste Piccard

Auguste Antoine Piccard (28 January 1884 – 24 March 1962) was a Switzerland, Swiss physicist, inventor and explorer known for his record-breaking Gas balloon, hydrogen balloon flights, with which he studied the Earth's upper atmosphere. Picca ...

to perform a high-altitude flight at the fairgrounds. Auguste declined, recommending his twin brother Jean

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jea ...

instead. Jean took the lead, but did not have a U. S. flight license, so the Piccards invited Settle to fly the balloon. Named for the show, ''Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Expositi ...

'' was built in America with a gondola donated by Dow Chemical

The Dow Chemical Company, officially Dow Inc., is an American multinational chemical corporation headquartered in Midland, Michigan, United States. The company is among the three largest chemical producers in the world.

Dow manufactures plastics ...

, a gas bag from Goodyear-Zeppelin, hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

donated by Union Carbide

Union Carbide Corporation is an American chemical corporation wholly owned subsidiary (since February 6, 2001) by Dow Chemical Company. Union Carbide produces chemicals and polymers that undergo one or more further conversions by customers befor ...

, and scientific instruments supplied by Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

and Robert Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectric e ...

.Ganz, pp. 148–149

The first flight from Soldier Field

Soldier Field is a multi-purpose stadium on the Near South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Opened in 1924 and reconstructed in 2003, the stadium has served as the home of the Chicago Bears of the National Football League (NFL) since 1 ...

, with Settle alone on board, attracted thousands of spectators and ended in a flop. Moments after liftoff, an open gas release valve forced ''Century'' to fall in a nearby railroad yard.Ganz, pp. 149

For the next flight the

For the next flight the Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

recommended their representative, Major Chester L. Fordney, to join Settle as instrument operator (the experiments were vital to justify financing of the flight).Ryan, p. 49 Fordney himself "was crazy for tying up with an adventurer like Settle". On November 20 they lifted off from the Goodyear-Zeppelin facilities in Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County, Ohio, Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 C ...

, watched by only a few hundred spectators. Nevertheless, the flight received national publicity as radio transmissions from the stratosphere were broadcast on radio networks. ''Century'' floated at peak altitude for two hours, and landed softly in Bridgeton, New Jersey

Bridgeton is a city in Cumberland County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is the county seat of Cumberland CountyDelaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

and Cohansey rivers,Vaeth, p. 93 incidentally, a few miles from Jean Piccard's home. It was already dark, so Settle and Fordney spent the night in the chilling cold of the gondola. They dumped radio batteries during descent, so in the morning Fordney waded five miles through the swamp in search for help. The balloon's barograph

A barograph is a barometer that records the barometric pressure over time in graphical form. This instrument is also used to make a continuous recording of atmospheric pressure. The pressure-sensitive element, a partially evacuated metal cylinde ...

, examined by the National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sci ...

, confirmed the world altitude record of 18,665 meters (61,237 feet). The flight earned Settle the Harmon Trophy

The Harmon Trophy is a set of three international trophies, to be awarded annually to the world's outstanding aviator, aviatrix, and aeronaut (balloon or dirigible). A fourth trophy, the "National Trophy," was awarded from 1926 through 1938 to t ...

and the FAI Henri de la Vaulx medal. Earlier in 1933 the ''USSR-1

''USSR-1'' (russian: СССР-1) was a record-setting, hydrogen-filled Soviet Air Forces high-altitude balloon designed to seat a crew of three and perform scientific studies of the Earth's stratosphere. On September 30, 1933, ''USSR-1'' under G ...

'' had flown to 62,230 feet, but it was not recognized by the FAI, so Settle and Fordney became the official record holder until the flight of ''Explorer II'' in 1935.

The Piccards retained ''Century of Progress''; while piloting the airship in October 1934, Jeannette Piccard

Jeannette Ridlon Piccard ( ; January 5, 1895 – May 17, 1981) was an American high-altitude balloon (aircraft), balloonist, and in later life an Episcopalianism, Episcopal priest. She held the women's altitude record for nearly three decades, an ...

became the first woman to reach the stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is an atmospheric layer composed of stratified temperature layers, with the warm layers of air ...

.

USS ''Palos''

Shortly before the record ascent, Settle applied for a transfer to sea duty. In the second half of 1934 Settle arrived inChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, tasked with sailing up the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

from Wusong

Wusong, formerly romanized as Woosung, is a subdistrict of Baoshan in northern Shanghai. Prior to the city's expansion, it was a separate port town located down the Huangpu River from Shanghai's urban core.

Name

Wusong is named for the Wus ...

to Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese dialects, Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Romanization, alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a Direct-administered municipalities of China, municipality in Southwes ...

.Tolley, p. 222 ''Palos'', a gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

stationed around Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

since 1914, had recently been refitted and over time became twice as heavy against her original displacement (340 vs. 180 tons), making her hardly capable of the upstream journey. In 1929 alone, of 67 Yangtze steamers three were totally destroyed by the rapid

Rapids are sections of a river where the river bed has a relatively steep gradient, causing an increase in water velocity and turbulence.

Rapids are hydrological features between a ''run'' (a smoothly flowing part of a stream) and a ''cascade''. ...

s with 47 casualties; a thousand junk sailors perished every year.Tolley, p. 230

The boat left Wusong on October 1, passing Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers wher ...

(the last "western" city on the route) on October 11. At Yichang

Yichang (), alternatively romanized as Ichang, is a prefecture-level city located in western Hubei province, China. It is the third largest city in the province after the capital, Wuhan and the prefecture-level city Xiangyang, by urban populati ...

Settle disembarked, leaving the boat and its crew to prepare for forcing the rapids

Rapids are sections of a river where the river bed has a relatively steep gradient, causing an increase in water velocity and turbulence.

Rapids are hydrological features between a ''run'' (a smoothly flowing part of a stream) and a ''cascade''. ...

, and himself took a reconnaissance trip to Chongqing on a British steamer.Tolley, p. 224 He returned just as the water level fell below optimum, and immediately ordered departure. Balancing engine thrust, steering, and pulling the boat by cables, and struggling to avoid downstream-bound junks, Settle managed to get ''Palos'' through the rocky rapids. On November 12, 1934, ''Palos'' reached Chongqing where it was eventually decommissioned in 1937; the hulk was still afloat in 1939.

After the ''Palos'' journey Settle remained on the Yangtze, now in command of another old gunboat, .Tolley, p. 301 In 1939–1941 Settle attended the Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associat ...

.

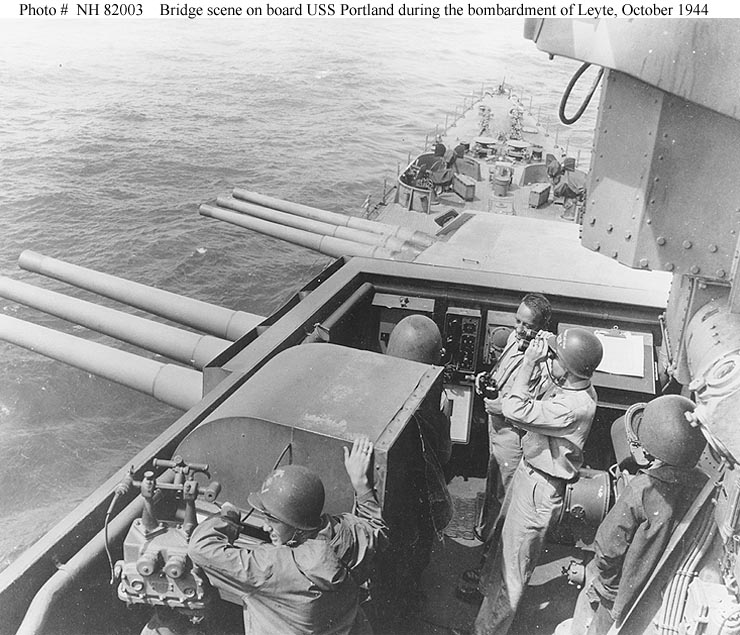

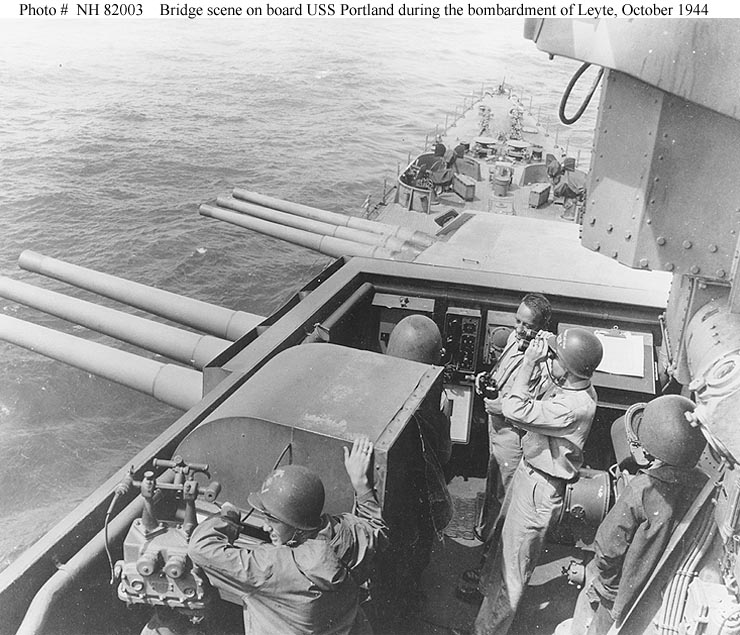

USS ''Portland''

On March 2, 1944, Settle arrived by airplane at his new command, , then stationed at

On March 2, 1944, Settle arrived by airplane at his new command, , then stationed at Eniwetok

Enewetak Atoll (; also spelled Eniwetok Atoll or sometimes Eniewetok; mh, Ānewetak, , or , ; known to the Japanese as Brown Atoll or Brown Island; ja, ブラウン環礁) is a large coral atoll of 40 islands in the Pacific Ocean and with it ...

. Prior to this appointment, Settle had been in charge of all of U.S. Navy blimps.Generous, p. 135 According to ''Portlands historian W. T. Generous, the crew—aware of Settle's pre-war fame—recognized him as an "All-Navy" carrier of old school naval tradition and etiquette

Etiquette () is the set of norms of personal behaviour in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviours that accord with the conventions and norms observed and practised by a ...

. Settle "walked with an air of superb self-confidence", making a "terrific impression on the crew", and maintained his reputation until leaving ''Portland''. He notably reduced internal paperwork and external communications, producing very brief dispatches.Generous, p. 136

After supporting landings in Hollandia, ''Portland'' returned to California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

for dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

repairs and sailed back to the war zone, via Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

, in August, carrying Seabee

United States Naval Construction Battalions, better known as the Navy Seabees, form the U.S. Naval Construction Force (NCF). The Seabee nickname is a heterograph of the initial letters "CB" from the words "Construction Battalion". Depending upon ...

s, infantrymen and reporters (including Joe Rosenthal

Joseph John Rosenthal (October 9, 1911 – August 20, 2006) was an American photographer who received the Pulitzer Prize for his iconic World War II photograph '' Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima'', taken during the 1945 Battle of Iwo Jima.

H ...

and John Brennan John Brennan may refer to:

Public officials

* Jack Brennan (born 1937), U.S. Marine officer and aide of Richard Nixon

* John Brennan (CIA officer) (born 1955), former CIA Director

* John P. Brennan (1864–1943), Democratic politician in the U. ...

).Generous, pp. 138, 139, 142 In September ''Portland'' arrived at Peleliu

Peleliu (or Beliliou) is an island in the island nation of Palau. Peleliu, along with two small islands to its northeast, forms one of the sixteen states of Palau. The island is notable as the location of the Battle of Peleliu in World War II.

H ...

, supporting landing at Peleliu with gunfire.

On the night of October 24, 1944, ''Portland'' took its place in Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf

Jesse Barrett "Oley" Oldendorf (16 February 1887 – 27 April 1974) was an admiral in the United States Navy, famous for defeating a Japanese force in the Battle of Leyte Gulf during World War II. He also served as commander of the American naval ...

's order of battle

In modern use, the order of battle of an armed force participating in a military operation or campaign shows the hierarchical organization, command structure, strength, disposition of personnel, and equipment of units and formations of the armed ...

at the northern exit of Surigao Strait

Surigao Strait (Filipino: ''Kipot ng Surigaw'') is a strait in the southern Philippines, between the Bohol Sea and the Leyte Gulf of the Philippine Sea.

Geography

It is located between the regions of Visayas and Mindanao. It lies between northern ...

, as an inferior Japanese detachment of two battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s and a heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

approached through the strait from the south. Shortly before 04:00 ''Portland'' gunners opened fire on the approaching '' Mogami''; by 05:40 the battle was over and Oldendorf recalled the pursuing cruisers.Generous, p. 174 ''Portland'' became the only heavy cruiser to engage enemy battleships at night ''twice''.Generous, p. 175 In December 1944, ''Portland'' provided gunfire support to ground troops in the battle of Mindoro

The Battle of Mindoro (Filipino: ''Labanan sa Mindoro'') was a battle in World War II between forces of the United States and Japan, in Mindoro Island in the central Philippines, from 13–16 December 1944, during the Philippines Campaign.

Tro ...

and then sailed to Palau

Palau,, officially the Republic of Palau and historically ''Belau'', ''Palaos'' or ''Pelew'', is an island country and microstate in the western Pacific. The nation has approximately 340 islands and connects the western chain of the Caro ...

, where Admiral Oldendorf presented Settle with a Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

for his action at Surigao Strait.Generous, p. 176

On the opening day of the invasion of Lingayen Gulf

The Invasion of Lingayen Gulf ( fil, Paglusob sa Golpo ng Lingayen), 6–9 January 1945, was an Allied amphibious operation in the Philippines during World War II. In the early morning of 6 January 1945, a large Allied force commanded by Admira ...

, January 9, 1945, when Rear Admiral Theodore E. Chandler

Theodore Edson Chandler (December 26, 1894 – January 7, 1945) was a Rear admiral of the United States Navy during World War II, who commanded battleship and cruiser divisions in both the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets. He was killed in action wh ...

was killed on January 7, 1945 from extensive lung burns from the kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

attack on January 6, 1945 commanding aboard , Settle assumed command of Chandler's Cruiser Division Two.Generous, p. 178 Settle's radical shiphandling skills saved ''Portland'' from direct kamikaze hits; ship's officers attributed their captain's luck to his former aviator experience.Generous, p. 178–179 Settle used to break formation under threat from the air, and at least once his maneuvering earned him a reprimand from a commanding admiral;Generous, p. 180 in another episode, it nearly led to the destruction of a landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. Pr ...

full of troops.Generous, p. 181

In February 1945 ''Portland'' together with and HMAS ''Shropshire'' supported ground and airborne forces in the recapture of Corregidor and in March sailed to assist capture of Okinawa. On March 21, his first day of the Okinawa campaign, Settle managed to evade eleven torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

attacks from a submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

but failed in ramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege weapon used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus, ...

the sub. He left command of ''Portland'' in July, one month before the end of the war, when the cruiser was still at Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

.

Post-war career

In 1946 Settle returned to China, on theYangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

where he replaced Vice Admiral Bertram J. Rodgers

Bertram Joseph Rodgers (March 18, 1894 – November 30, 1983) was a highly decorated Vice Admiral in the United States Navy during World War II. He received his Navy Cross as a Captain of USS ''Salt Lake City'' in the battle of the Komando ...

as the commander of the Seventh Amphibious Force. Later, Settle moved to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

assisting in the implementation of U.S. aid to Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and Turkey under the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It was ...

. He had a long-held ambition to become the ambassador to the Soviet Union that never materialized. After his return to the United States Settle served with the 8th Naval District

The naval district was a U.S. Navy military and administrative command ashore. Apart from Naval District Washington, the Districts were disestablished and renamed Navy Regions about 1999, and are now under Commander, Naval Installations Command ...

in New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, with the Pacific Fleet in Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, and in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

.

In 1950 Rear Admiral Settle was appointed commander of Joint Task Force 131, responsible for carrying out underground nuclear tests

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

on the Aleutian island Amchitka

Amchitka (; ale, Amchixtax̂; russian: Амчитка) is a volcanic, tectonically unstable and uninhabited

island in the Rat Islands group of the Aleutian Islands in southwest Alaska. It is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refu ...

, codenamed Operation Windstorm.Kohlhoff, p. 34 Three 20-kiloton

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a t ...

blasts were scheduled for August 30, September 22 and October 2, 1951. In March 1951 news of an upcoming test leaked to the press; Settle proposed a rescheduling of the operation that, in his opinion, would be safer and simpler if performed at established test sites in Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

and California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

.Kohlhoff, p. 36 As the military and politicians discussed probable alternatives, Settle spoke out in favor of discarding the Aleutian program and disbanding Task Force 131.Kohlhoff, p. 38 The project was eventually closed in summer of 1951.Nuclear tests on the island were performed later, in 1965, 1969 and 1971. See Amchitka

Amchitka (; ale, Amchixtax̂; russian: Амчитка) is a volcanic, tectonically unstable and uninhabited

island in the Rat Islands group of the Aleutian Islands in southwest Alaska. It is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refu ...

for details.

Settle later served with the temporary rank of Vice admiral as Commander, Amphibious Force, Pacific Fleet from 1954 to 1956 and then reverted to Rear admiral and retired one year later.

Awards

Books by Settle

* ''The Last Cruise of Palos'' (1964), in: , originally published in ''Shipmates'', vol. 24 no. 4, April 1964Notes and references

References

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*"Why Explore The Stratosphere?"

''Popular Mechanics'', October 1933 {{DEFAULTSORT:Settle, Thomas G. W. 1895 births 1980 deaths People from Washington, D.C. United States Naval Academy alumni Naval War College alumni Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences alumni United States Naval Aviators American balloonists United States Navy admirals United States Navy World War II admirals Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Legion of Merit Flight altitude record holders Flight endurance record holders Balloon flight record holders American aviation record holders