Thomas Evans (Spencean) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Evans (1763 – by 1831) was a British revolutionary conspirator. Active in the 1790s and the period 1816–1820, he is otherwise a shadowy character, known mainly as a hardline follower of Thomas Spence.

In April 1798 Evans was arrested, in a roundup of the United Englishmen. He was not put on trial, but was in detention for three years. It followed the re-arrest in February of Arthur O'Connor at

In April 1798 Evans was arrested, in a roundup of the United Englishmen. He was not put on trial, but was in detention for three years. It followed the re-arrest in February of Arthur O'Connor at

On his release, Evans in partnership with Robert Wedderburn took a lease on a chapel on Archer Street in Soho. It was at least nominally a Unitarian place of worship, and became a Spencean centre. Wedderburn broke with Evans in April 1819, moving his chapel within Soho to Hopkins Street, and plotting revolution. Evans attended the post-

On his release, Evans in partnership with Robert Wedderburn took a lease on a chapel on Archer Street in Soho. It was at least nominally a Unitarian place of worship, and became a Spencean centre. Wedderburn broke with Evans in April 1819, moving his chapel within Soho to Hopkins Street, and plotting revolution. Evans attended the post-

Early life

By 1794 Evans was living in London, married to Janet Galloway, also a radical. At this point they were inSoho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develop ...

, supporting themselves by colouring engravings, which included "bawdy prints". They were in Frith Street

Frith Street is in the Soho area of London. To the north is Soho Square and to the south is Shaftesbury Avenue. The street crosses Old Compton Street, Bateman Street and Romilly Street.

History

Frith Street was laid out in the late 1670s an ...

, and provided there a mailing address to some reformers.

In 1796 the couple moved to Fetter Lane

Fetter Lane is a street in the ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London. It forms part of the A4 road and runs between Fleet Street at its southern end and Holborn.

History

The street was originally called Faytor or Faiter Lane, then Fe ...

. Evans had a number of trades, including baker, and shortly an income enough to rent space there adequate to host radical meetings. In early 1797, Evans was leader in London of the United Englishmen

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

, with John Bone and Alexander Galloway

Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Galloway, (3 November 1895 – 28 January 1977) was a senior British Army officer. During the Second World War, he was particularly highly regarded as a staff officer and, as such, had an influential role in the ...

, Janet's brother. The United Englishmen aimed at co-ordinated armed risings in England, Scotland and Ireland, at the time of a French invasion. From 1797, the Fetter Lane house saw visits from Benjamin Binns, brother of John Binns, the Manchester radical John Smith, and James O'Coigly.

In 1798 Evans was secretary of the London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associati ...

(LCS), with which he had been involved for some years.

First time in prison

In April 1798 Evans was arrested, in a roundup of the United Englishmen. He was not put on trial, but was in detention for three years. It followed the re-arrest in February of Arthur O'Connor at

In April 1798 Evans was arrested, in a roundup of the United Englishmen. He was not put on trial, but was in detention for three years. It followed the re-arrest in February of Arthur O'Connor at Margate

Margate is a seaside resort, seaside town on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. The town is estimated to be 1.5 miles long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay, UK, Palm Bay and Westbrook, Kent, ...

, seeking passage to France. Questioned after his arrest, Evans admitted removing a box of LCS papers from his house after O'Connor was picked up with John Binns; and his role as a signatory, with Robert Thomas Crossfield of the LCS, of an address by Binns for the LCS to the "Irish Nation", which the government had discovered in Dublin.

Evans was held under the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act 1798

The Habeas Corpus Suspension Act 1798 ( 38 Geo. 3. c. 36) was an Act of Parliament passed by the Parliament of Great Britain.

On 28 February 1798 five members of the leading Jacobin Societies were arrested at Margate while they were trying to tr ...

. He referred to that circumstance, and his time in confinement, in an 1817 petition to the House of Commons presented by Charles Augustus Bennet. Robert Cutlar Fergusson

Robert Cutlar Fergusson (1768–1838) was a Scottish lawyer and politician. He was 17th Laird of the Dumfriesshire Fergussons, seated at Craigdarroch (Moniaive, Dumfriesshire).

Life

Robert Fergusson was born in Dumfries, the eldest son of Alexa ...

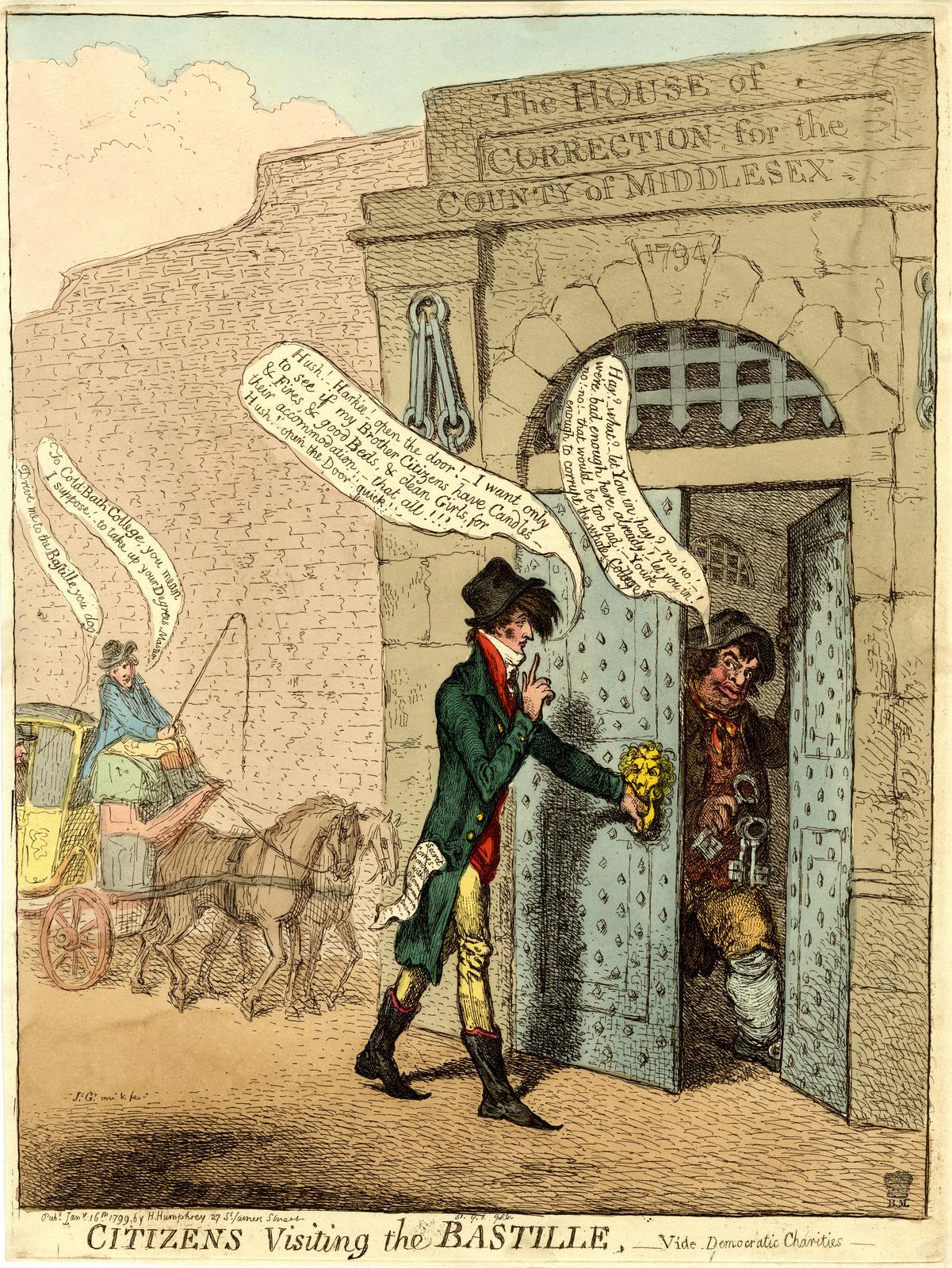

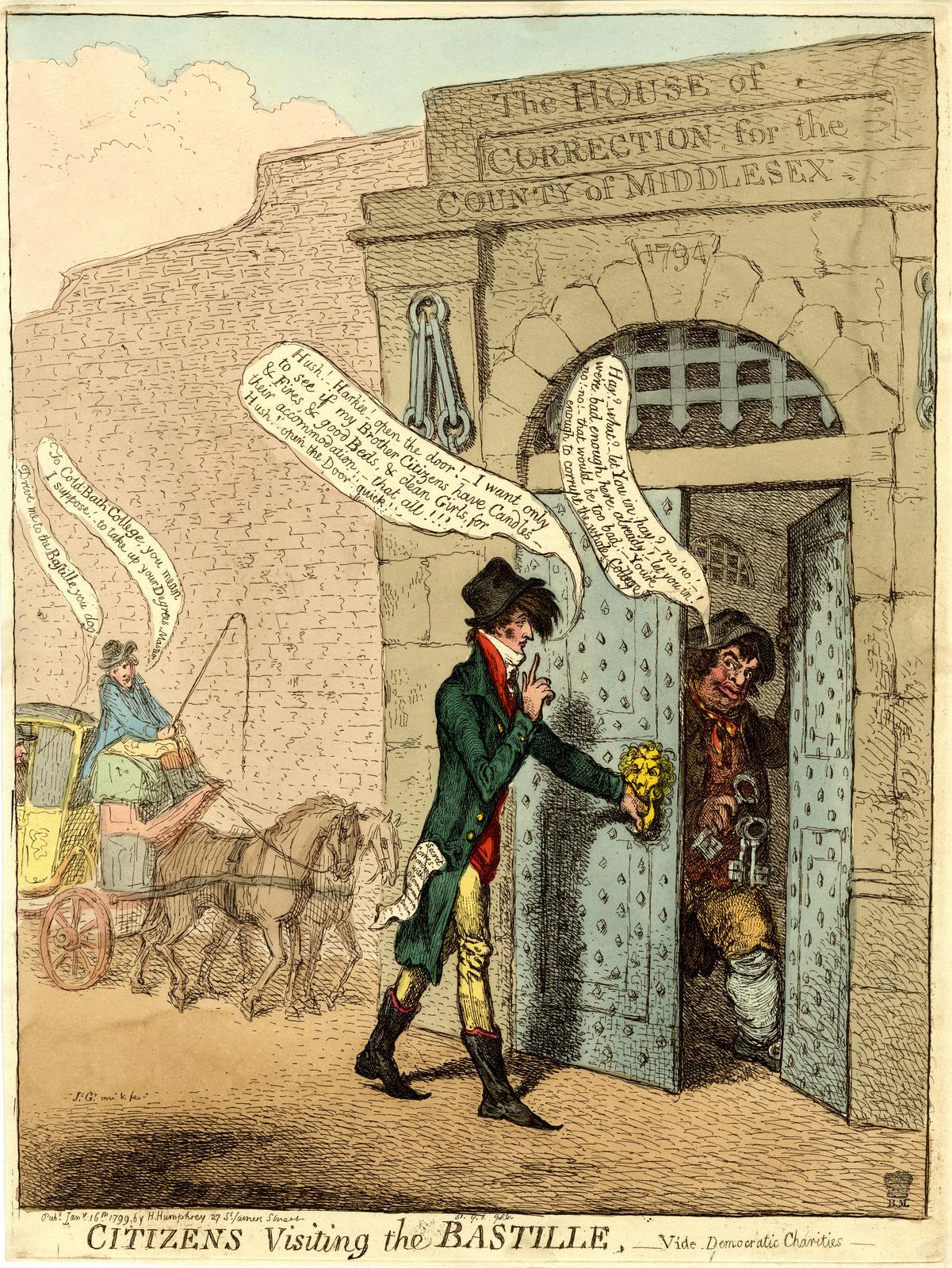

, a barrister involved in the defense of Binns, O'Coigly and O'Connor in May 1798, in 1799 tried unsuccessfully to argue that a house of correction

The house of correction was a type of establishment built after the passing of the Elizabethan Poor Law (1601), places where those who were "unwilling to work", including vagrants and beggars, were set to work. The building of houses of correctio ...

was unsuitable as a place of custody for Evans, accused of high treason. Evans was being held in the House of Correction for Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

, Coldbath Fields Prison, where the governor was Thomas Aris.

Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

met Evans in Coldbath Fields Prison in 1798. Burdett subsequently ran a campaign in parliament against governor Aris, for maltreatment of prisoners, with information provided by Evans, John Bone and a United Irishman, Patrick William Duffin, confined in the prison. Burdett was then barred from the prison, which also housed Edward Despard

Edward Marcus Despard (175121 February 1803), an Kingdom of Ireland, Irish officer in the service of the The Crown, British Crown, gained notoriety as a colonial administrator for refusing to recognise racial distinctions in law and, following his ...

, in January 1799. By the end of 1800 he had substantially justified his case. There was also an out-of-doors publicity campaign by a radical group including Peter Finnerty

Peter Finnerty (1766?–11 May 1822) was an Irish printer, publisher, and journalist in both Dublin and London associated with radical, reform and democratic causes. In Dublin, he was a committed United Irishman, but was imprisoned in the course ...

, J. S. Jordan, John Horne Tooke and Robert Waithman

Robert Waithman (1764 – 6 February 1833) was a master draper who in later life was a British politician; an economic progressive Whig from an industrial background and a political reformist. He became an alderman of the Corporation of London ...

.

1801–1817

Evans was released in March 1801. He was set up in business as a manufacturer by his wife Janet, making steel springs and the leather braces that went with them. She used a legacy she had received after the death of her father in 1799. In the1802 United Kingdom general election

The 1802 United Kingdom general election was the election to the House of Commons of the second Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was the first to be held after the Union of Great Britain and Ireland. The first Parliament had been composed ...

, Burdett made a successful move of seats, standing for . Evans associated with his campaign, which was against William Mainwaring

William Henry Mainwaring (1884 – 18 May 1971) was a Welsh people, Welsh coal miner, lecturer and trade unionist, who became a long-serving Labour Party (UK), Labour Party Member of Parliament. Both as a trade unionist and a politician he strugg ...

. Mainwaring, leader of Middlesex magistracy, had been heavily involved in Tory efforts to blunt his criticism of Aris. Burdett had the backing of the "Wimbledon circle" of radical lawyers around Horne Tooke. Evans made himself useful as a go-between for them and the more extreme radicals, on behalf of Burdett.

In 1803, not long after the execution of Edward Despard, police arrested Arthur Seale, a printer in Tottenham Court Road

Tottenham Court Road (occasionally abbreviated as TCR) is a major road in Central London, almost entirely within the London Borough of Camden.

The road runs from Euston Road in the north to St Giles Circus in the south; Tottenham Court Road tub ...

, for publishing a subversive handbill "Are You Right". They believed Evans to be its author; and responsible also for a pamphlet set up in print they found, about Despard's trial. Spencer Perceval and Sir Richard Ford offered Seale a chance to escape prison if he incriminated Evans. Seale shunned the chance and was sentenced to six months in Newgate Gaol

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, th ...

. From this period, Evans kept a low profile for a decade, meeting the like-minded in taverns.

In 1814 the radical Thomas Spence died, and Evans assumed his mantle, including his championing of common ownership

Common ownership refers to holding the assets of an organization, enterprise or community indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or groups of members as common property.

Forms of common ownership exist in every economi ...

as the basis of land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

. He became leader of the group of around 40 Spenceans, drawn from artisans. Within two years, the Society of Spencean Philanthropists had become a revolutionary group, including the Burdettite Thomas Preston (1774–1850), Arthur Thistlewood

Arthur Thistlewood (1774–1 May 1820) was an English radical activist and conspirator in the Cato Street Conspiracy. He planned to murder the cabinet, but there was a spy and he was apprehended with 12 other conspirators. He killed a policem ...

and James Watson (1766–1838). Evans himself engaged in political debate with ''Christian Policy: the Salvation of the Empire'' (1816), which was answered by Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book '' An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

and Robert Southey.

Second time in prison

Evans was arrested, suspected of involvement in the planning of theSpa Fields riots

The Spa Fields riots were incidents of public disorder arising out of the second of two mass meetings at Spa Fields, Islington, England on 15 November and 2 December 1816.

The meetings had been planned by a small group of revolutionary Spenceans ...

of November and December 1816. After habeas corpus was suspended in March 1817, he was held without trial until 1818. He was kept once more Coldbath Fields Prison, and his son was in Horsemonger Lane Gaol.

Later life

On his release, Evans in partnership with Robert Wedderburn took a lease on a chapel on Archer Street in Soho. It was at least nominally a Unitarian place of worship, and became a Spencean centre. Wedderburn broke with Evans in April 1819, moving his chapel within Soho to Hopkins Street, and plotting revolution. Evans attended the post-

On his release, Evans in partnership with Robert Wedderburn took a lease on a chapel on Archer Street in Soho. It was at least nominally a Unitarian place of worship, and became a Spencean centre. Wedderburn broke with Evans in April 1819, moving his chapel within Soho to Hopkins Street, and plotting revolution. Evans attended the post-Peterloo

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliamen ...

meeting at the Crown and Anchor, Strand

The Crown and Anchor, also written Crown & Anchor and earlier known as The Crown, was a public house in Arundel Street, off The Strand in London, England, famous for meetings of political (particularly the early 19th-century Radicals) and vari ...

of September 1819 for the "Westminster Committee of 200" with his son, Richard Carlile

Richard Carlile (8 December 1790 – 10 February 1843) was an important agitator for the establishment of universal suffrage and freedom of the press in the United Kingdom.

Early life

Born in Ashburton, Devon, he was the son of a shoemaker wh ...

also being there.

In the aftermath of the failed Cato Street conspiracy of 1820, led by Thistlewood and other Spenceans, Evans raised funds for the families of the arrested plotters. Shortly afterwards he moved to Manchester, living with his son.

Relationship with Francis Place

Francis Place was a prominent LCS member of the 1790s, and in the 1820s an effective leader of the artisan radicals. Towards the end of theNapoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

he became a target for the group around Evans and Thistlewood. Since his accounts of those years came to have high standing, Place's severe criticisms of these opponents have affected the historiography of London radicalism. In relation to a London power struggle in 1816–1817, E. P. Thompson

Edward Palmer Thompson (3 February 1924 – 28 August 1993) was an English historian, writer, socialist and peace campaigner. He is best known today for his historical work on the radical movements in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in ...

commented in '' The Making of the English Working Class'' that "Place is not a disinterested witness"; and that the Spenceans prepared the ground for Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted e ...

and his ''New View of Society''.

Place was the jury foreman for the inquest into the Sellis incident involving the Duke of Cumberland. The jury concluded that Joseph Sellis, valet to the Duke, had committed suicide. The verdict was unpopular with the Burdettite radicals. Evans, with John King (Jacob Rey) the moneylender and Duffin, were in a group who attempted blackmail

Blackmail is an act of coercion using the threat of revealing or publicizing either substantially true or false information about a person or people unless certain demands are met. It is often damaging information, and it may be revealed to fa ...

of Place over his part in the outcome. Duffin used the pages of the ''Independent Whig'', of which he was co-founder in 1806, to make allegations that Place was in the pay of the government.

Burdett's influence prevailed when Place, with Joseph Hume and James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of British ...

, was interested in the educational project of a West London Lancasterian Association, founded on the ideas of Joseph Lancaster

Joseph Lancaster (25 November 1778 – 23 October 1838) was an English Quaker and public education innovator. He developed, and propagated on the grounds both of economy and efficacy, a monitorial system of primary education. In the first deca ...

, was floated in 1813. In 1814, Francis Burdett intervened and imposed on it his associates Evans and Arthur Thistlewood. The sidelined Place then abandoned politics for four years.

Works

* ''Christian Policy, the Salvation of the Empire'' (1816), published by Arthur Seale. *''Christian Policy In Full Practice'' (1818), which makes reference to the Harmonists ofPennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. These works combined agrarianism

Agrarianism is a political and social philosophy that has promoted subsistence agriculture, smallholdings, and egalitarianism, with agrarian political parties normally supporting the rights and sustainability of small farmers and poor peasants ...

with the invocation of the biblical jubilee.

Family

Evans and his wife Janet had a son, Thomas John Evans, born shortly before his father was imprisoned for the first time. He travelled to Paris in 1814, and in February 1820 took over as editor of the ''Manchester Observer

The ''Manchester Observer'' was a short-lived non-conformist Liberal newspaper based in Manchester, England. Its radical agenda led to an invitation to Henry "Orator" Hunt to speak at a public meeting in Manchester, which subsequently led to th ...

'' from James Wroe

James Wroe (1788–1844), was the only editor of the radical reformist newspaper the ''Manchester Observer'', the journalist who named the incident known as the Peterloo massacre, and the writer of pamphlets as a result that brought about the Refo ...

, with backing from Francis Place and his uncle Alexander Galloway.

Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Evans, Thomas 1763 births Date of death unknown English revolutionaries