Thermionic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thermionic emission is the liberation of

Thermionic emission is the liberation of

Because the

Because the

In electron emission devices, especially

In electron emission devices, especially

How vacuum tubes really work with a section on thermionic emission, with equations

john-a-harper.com.

Thermionic Phenomena and the Laws which Govern Them

Owen Richardson's Nobel lecture on thermionics. nobelprize.org. December 12, 1929. (PDF)

Derivations of thermionic emission equations from an undergraduate lab

csbsju.edu. {{Thomas Edison Atomic physics Electricity Energy conversion Vacuum tubes Thomas Edison

Thermionic emission is the liberation of

Thermionic emission is the liberation of electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary partic ...

s from an electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or air). Electrodes are essential parts of batteries that can consist of a variety of materials ...

by virtue of its temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various temperature scales that historically have relied on ...

(releasing of energy supplied by heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

). This occurs because the thermal energy

The term "thermal energy" is used loosely in various contexts in physics and engineering. It can refer to several different well-defined physical concepts. These include the internal energy or enthalpy of a body of matter and radiation; heat, ...

given to the charge carrier

In physics, a charge carrier is a particle or quasiparticle that is free to move, carrying an electric charge, especially the particles that carry electric charges in electrical conductors. Examples are electrons, ions and holes. The term is u ...

overcomes the work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelt workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" ...

of the material. The charge carriers can be electrons or ions

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conve ...

, and in older literature are sometimes referred to as thermions. After emission, a charge that is equal in magnitude and opposite in sign to the total charge emitted is initially left behind in the emitting region. But if the emitter is connected to a battery, the charge left behind is neutralized by charge supplied by the battery as the emitted charge carriers move away from the emitter, and finally the emitter will be in the same state as it was before emission.

The classical example of thermionic emission is that of electrons from a hot cathode

In vacuum tubes and gas-filled tubes, a hot cathode or thermionic cathode is a cathode electrode which is heated to make it emit electrons due to thermionic emission. This is in contrast to a cold cathode, which does not have a heating elem ...

into a vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or " void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often di ...

(also known as thermal electron emission or the Edison effect) in a vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied.

The type kn ...

. The hot cathode can be a metal filament, a coated metal filament, or a separate structure of metal or carbides or borides of transition metals. Vacuum emission from metals tends to become significant only for temperatures over .

This process is crucially important in the operation of a variety of electronic devices and can be used for electricity generation

Electricity generation is the process of generating electric power from sources of primary energy. For utilities in the electric power industry, it is the stage prior to its delivery ( transmission, distribution, etc.) to end users or its stor ...

(such as thermionic converter

A thermionic converter consists of a hot electrode which thermionically emits electrons over a potential energy barrier to a cooler electrode, producing a useful electric power output. Caesium vapor is used to optimize the electrode work functi ...

s and electrodynamic tether

Electrodynamic tethers (EDTs) are long conducting wires, such as one deployed from a tether satellite, which can operate on electromagnetism, electromagnetic principles as electrical generator, generators, by converting their kinetic energy to ele ...

s) or cooling. The magnitude of the charge flow increases dramatically with increasing temperature.

The term 'thermionic emission' is now also used to refer to any thermally-excited charge emission process, even when the charge is emitted from one solid-state

Solid state, or solid matter, is one of the four fundamental states of matter.

Solid state may also refer to:

Electronics

* Solid-state electronics, circuits built of solid materials

* Solid state ionics, study of ionic conductors and their ...

region into another.

History

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary partic ...

was not identified as a separate physical particle until the work of J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be discovered.

In 1897, Thomson showed that ...

in 1897, the word "electron" was not used when discussing experiments that took place before this date.

The phenomenon was initially reported in 1853 by Edmond Becquerel. It was rediscovered in 1873 by Frederick Guthrie

Frederick Guthrie FRS FRSE (15 October 1833 – 21 October 1886) was a British physicist and chemist and academic author.

He was the son of Alexander Guthrie, a London tradesman, and the younger brother of mathematician Francis Guthrie. Al ...

in Britain. While doing work on charged objects, Guthrie discovered that a red-hot iron sphere with a negative charge would lose its charge (by somehow discharging it into air). He also found that this did not happen if the sphere had a positive charge. Other early contributors included Johann Wilhelm Hittorf

Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (27 March 1824 – 28 November 1914) was a German physicist who was born in Bonn and died in Münster, Germany.

Hittorf was the first to compute the electricity-carrying capacity of charged atoms and molecules (ions), an ...

(1869–1883), Eugen Goldstein

Eugen Goldstein (; 5 September 1850 – 25 December 1930) was a German physicist. He was an early investigator of discharge tubes, the discoverer of anode rays or canal rays, later identified as positive ions in the gas phase including the hy ...

(1885), and Julius Elster Julius Johann Phillipp Ludwig Elster (24 December 1854 in Blankenburg – 6 April 1920) was a teacher and physicist.

Biography

Elster and Hans Friedrich Geitel, the son of a Forstmeister who had moved to Blankenburg with his family in 1861, grew ...

and Hans Friedrich Geitel

Hans Friedrich Karl Geitel (16 July 1855 in Braunschweig – 15 August 1923 in Wolfenbüttel) was a German physicist. He is credited with coining the phrase "atomic energy."

Biography

Through the relocation of his family, his father was a foreste ...

(1882–1889).

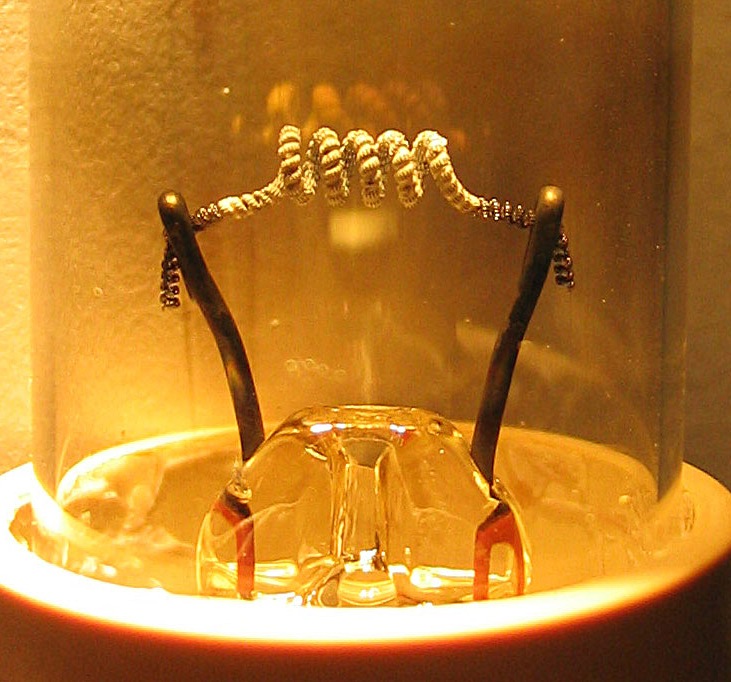

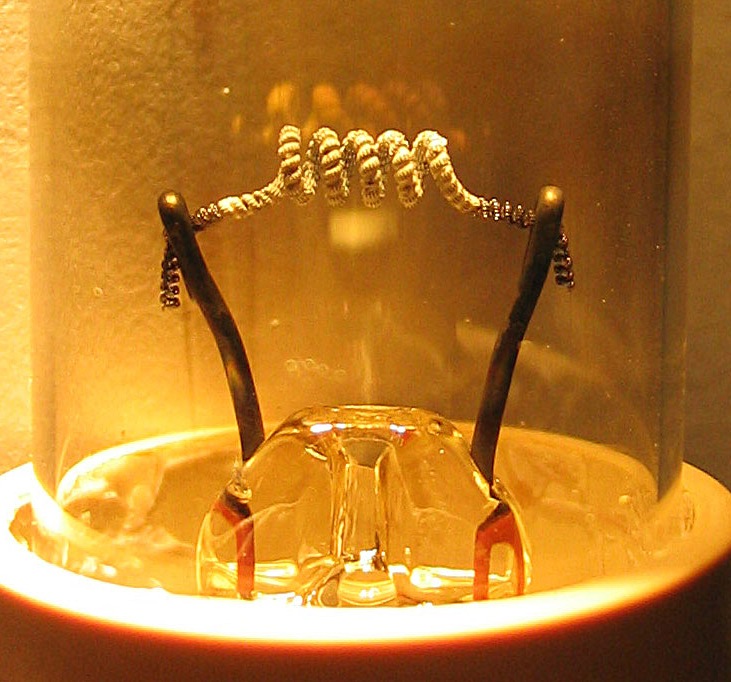

The effect was rediscovered again by Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These invent ...

on February 13, 1880, while he was trying to discover the reason for breakage of lamp filaments and uneven blackening (darkest near the positive terminal of the filament) of the bulbs in his incandescent lamp

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxida ...

s.

Edison built several experimental lamp bulbs with an extra wire, metal plate, or foil inside the bulb that was separate from the filament and thus could serve as an electrode. He connected a galvanometer

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely.

A galvano ...

, a device used to measure current (the flow of charge), to the output of the extra metal electrode. If the foil was put at a negative potential relative to the filament, there was no measurable current between the filament and the foil. When the foil was raised to a positive potential relative to the filament, there could be a significant current between the filament through the vacuum to the foil if the filament was heated sufficiently (by its own external power source).

We now know that the filament was emitting electrons, which were attracted to a positively charged foil, but not a negatively charged one. This one-way current was called the ''Edison effect'' (although the term is occasionally used to refer to thermionic emission itself). He found that the current emitted by the hot filament increased rapidly with increasing voltage, and filed a patent application for a voltage-regulating device using the effect on November 15, 1883 (U.S. patent 307,031, the first US patent for an electronic device). He found that sufficient current would pass through the device to operate a telegraph sounder. This was exhibited at the International Electrical Exposition

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

in Philadelphia in September 1884. William Preece

Sir William Henry Preece (15 February 1834 – 6 November 1913) was a Welsh electrical engineer and inventor. Preece relied on experiments and physical reasoning in his life's work. Upon his retirement from the Post Office in 1899, Preece was m ...

, a British scientist, took back with him several of the Edison effect bulbs. He presented a paper on them in 1885, where he referred to thermionic emission as the "Edison effect."

The British physicist John Ambrose Fleming

Sir John Ambrose Fleming FRS (29 November 1849 – 18 April 1945) was an English electrical engineer and physicist who invented the first thermionic valve or vacuum tube, designed the radio transmitter with which the first transatlantic rad ...

, working for the British "Wireless Telegraphy" Company, discovered that the Edison effect could be used to detect radio waves. Fleming went on to develop the two-element vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied.

The type kn ...

known as the diode, which he patented on November 16, 1904.

The thermionic diode can also be configured as a device that converts a heat difference to electric power directly without moving parts (a thermionic converter

A thermionic converter consists of a hot electrode which thermionically emits electrons over a potential energy barrier to a cooler electrode, producing a useful electric power output. Caesium vapor is used to optimize the electrode work functi ...

, a type of heat engine

In thermodynamics and engineering, a heat engine is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower state t ...

).

Richardson's law

Following J. J. Thomson's identification of the electron in 1897, the British physicistOwen Willans Richardson

Sir Owen Willans Richardson, FRS (26 April 1879 – 15 February 1959) was a British physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1928 for his work on thermionic emission, which led to Richardson's law.

Biography

Richardson was born in Dews ...

began work on the topic that he later called "thermionic emission". He received a Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1928 "for his work on the thermionic phenomenon and especially for the discovery of the law named after him".

From band theory

In solid-state physics, the electronic band structure (or simply band structure) of a solid describes the range of energy levels that electrons may have within it, as well as the ranges of energy that they may not have (called ''band gaps'' or '' ...

, there are one or two electrons per atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas ...

in a solid that are free to move from atom to atom. This is sometimes collectively referred to as a "sea of electrons". Their velocities follow a statistical distribution, rather than being uniform, and occasionally an electron will have enough velocity to exit the metal without being pulled back in. The minimum amount of energy needed for an electron to leave a surface is called the work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelt workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" ...

. The work function is characteristic of the material and for most metals is on the order of several electronvolt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacu ...

s. Thermionic currents can be increased by decreasing the work function. This often-desired goal can be achieved by applying various oxide coatings to the wire.

In 1901 Richardson

Richardson may refer to:

People

* Richardson (surname), an English and Scottish surname

* Richardson Gang, a London crime gang in the 1960s

* Richardson Dilworth, Mayor of Philadelphia (1956-1962)

Places Australia

*Richardson, Australian Capi ...

published the results of his experiments: the current from a heated wire seemed to depend exponentially on the temperature of the wire with a mathematical form similar to the Arrhenius equation

In physical chemistry, the Arrhenius equation is a formula for the temperature dependence of reaction rates. The equation was proposed by Svante Arrhenius in 1889, based on the work of Dutch chemist Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff who had noted in 18 ...

. Later, he proposed that the emission law should have the mathematical form

:

where ''J'' is the emission current density

In electromagnetism, current density is the amount of charge per unit time that flows through a unit area of a chosen cross section. The current density vector is defined as a vector whose magnitude is the electric current per cross-sectional a ...

, ''T'' is the temperature of the metal, ''W'' is the work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelt workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" ...

of the metal, ''k'' is the Boltzmann constant

The Boltzmann constant ( or ) is the proportionality factor that relates the average relative kinetic energy of particles in a gas with the thermodynamic temperature of the gas. It occurs in the definitions of the kelvin and the gas consta ...

, and ''A''G is a parameter discussed next.

In the period 1911 to 1930, as physical understanding of the behaviour of electrons in metals increased, various theoretical expressions (based on different physical assumptions) were put forward for ''A''G, by Richardson, Saul Dushman

Saul Dushman (July 12, 1883 – July 7, 1954) was a Russian-American physical chemist.

Dushman was born on July 12, 1883 in Rostov, Russia; he immigrated to the United States in 1891. He received a doctorate from the University of Toronto ...

, Ralph H. Fowler

Sir Ralph Howard Fowler (17 January 1889 – 28 July 1944) was a British physicist and astronomer.

Education

Fowler was born at Roydon, Essex, on 17 January 1889 to Howard Fowler, from Burnham, Somerset, and Frances Eva, daughter of George Dew ...

, Arnold Sommerfeld

Arnold Johannes Wilhelm Sommerfeld, (; 5 December 1868 – 26 April 1951) was a German theoretical physicist who pioneered developments in atomic and quantum physics, and also educated and mentored many students for the new era of theoretic ...

and Lothar Wolfgang Nordheim

LotharHis name is sometimes misspelled as ''Lother''. Wolfgang Nordheim (November 7, 1899, Munich – October 5, 1985, La Jolla, California) was a German born Jewish American theoretical physicist. He was a pioneer in the applications of quantum ...

. Over 60 years later, there is still no consensus among interested theoreticians as to the exact expression of ''A''G, but there is agreement that ''A''G must be written in the form

:

where ''λ''R is a material-specific correction factor that is typically of order 0.5, and ''A''0 is a universal constant given by

:

where ''m'' and are the mass and charge of an electron, respectively, and ''h'' is Planck's constant.

In fact, by about 1930 there was agreement that, due to the wave-like nature of electrons, some proportion ''r''av of the outgoing electrons would be reflected as they reached the emitter surface, so the emission current density would be reduced, and ''λ''R would have the value (1-''r''av). Thus, one sometimes sees the thermionic emission equation written in the form

:.

However, a modern theoretical treatment by Modinos assumes that the band-structure of the emitting material must also be taken into account. This would introduce a second correction factor ''λ''B into ''λ''R, giving . Experimental values for the "generalized" coefficient ''A''G are generally of the order of magnitude of ''A''0, but do differ significantly as between different emitting materials, and can differ as between different crystallographic face

Miller indices form a notation system in crystallography for lattice planes in crystal (Bravais) lattices.

In particular, a family of lattice planes of a given (direct) Bravais lattice is determined by three integers ''h'', ''k'', and ''� ...

s of the same material. At least qualitatively, these experimental differences can be explained as due to differences in the value of ''λ''R.

Considerable confusion exists in the literature of this area because: (1) many sources do not distinguish between ''A''G and ''A''0, but just use the symbol ''A'' (and sometimes the name "Richardson constant") indiscriminately; (2) equations with and without the correction factor here denoted by ''λ''R are both given the same name; and (3) a variety of names exist for these equations, including "Richardson equation", "Dushman's equation", "Richardson–Dushman equation" and "Richardson–Laue–Dushman equation". In the literature, the elementary equation is sometimes given in circumstances where the generalized equation would be more appropriate, and this in itself can cause confusion. To avoid misunderstandings, the meaning of any "A-like" symbol should always be explicitly defined in terms of the more fundamental quantities involved.

Because of the exponential function, the current increases rapidly with temperature when ''kT'' is less than ''W''. (For essentially every material, melting occurs well before ''kT'' = ''W''.)

The thermionic emission law has been recently revised for 2D materials in various models.

Schottky emission

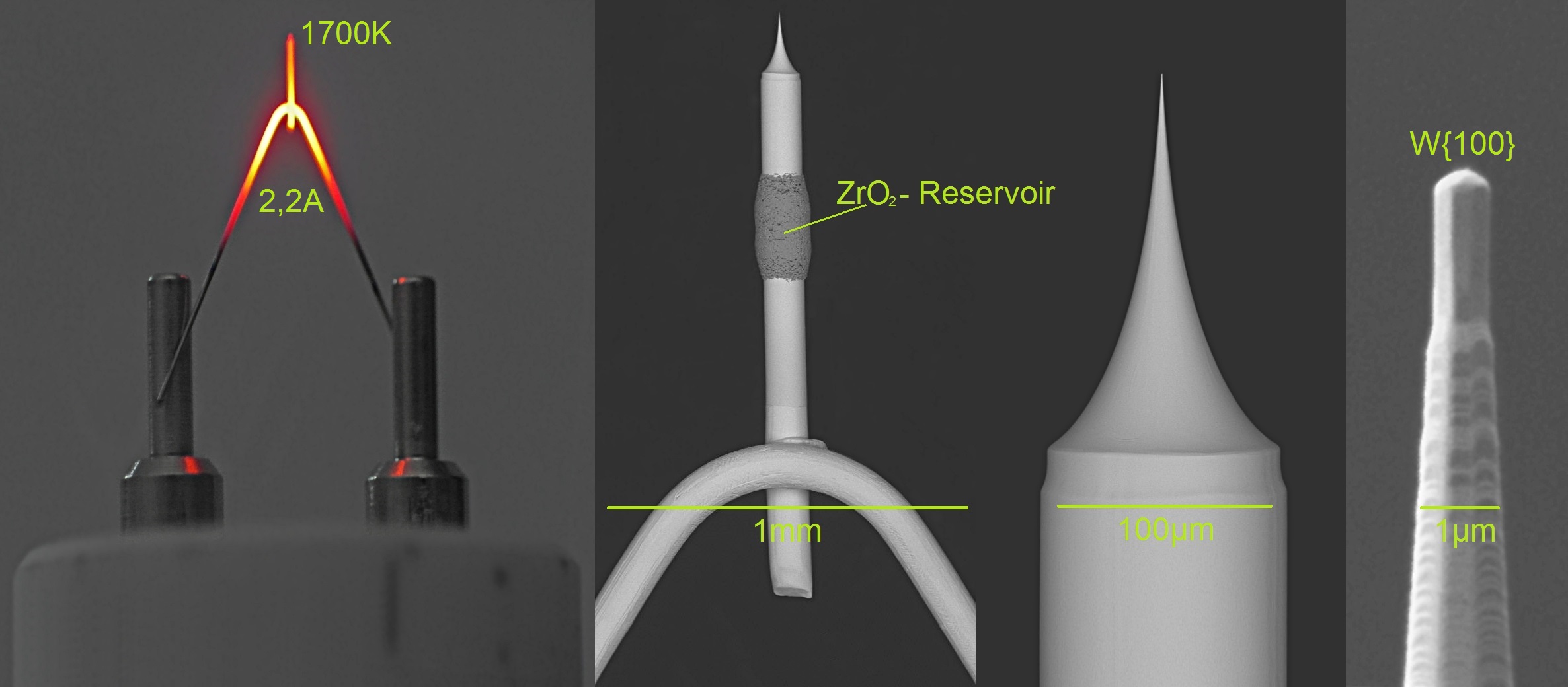

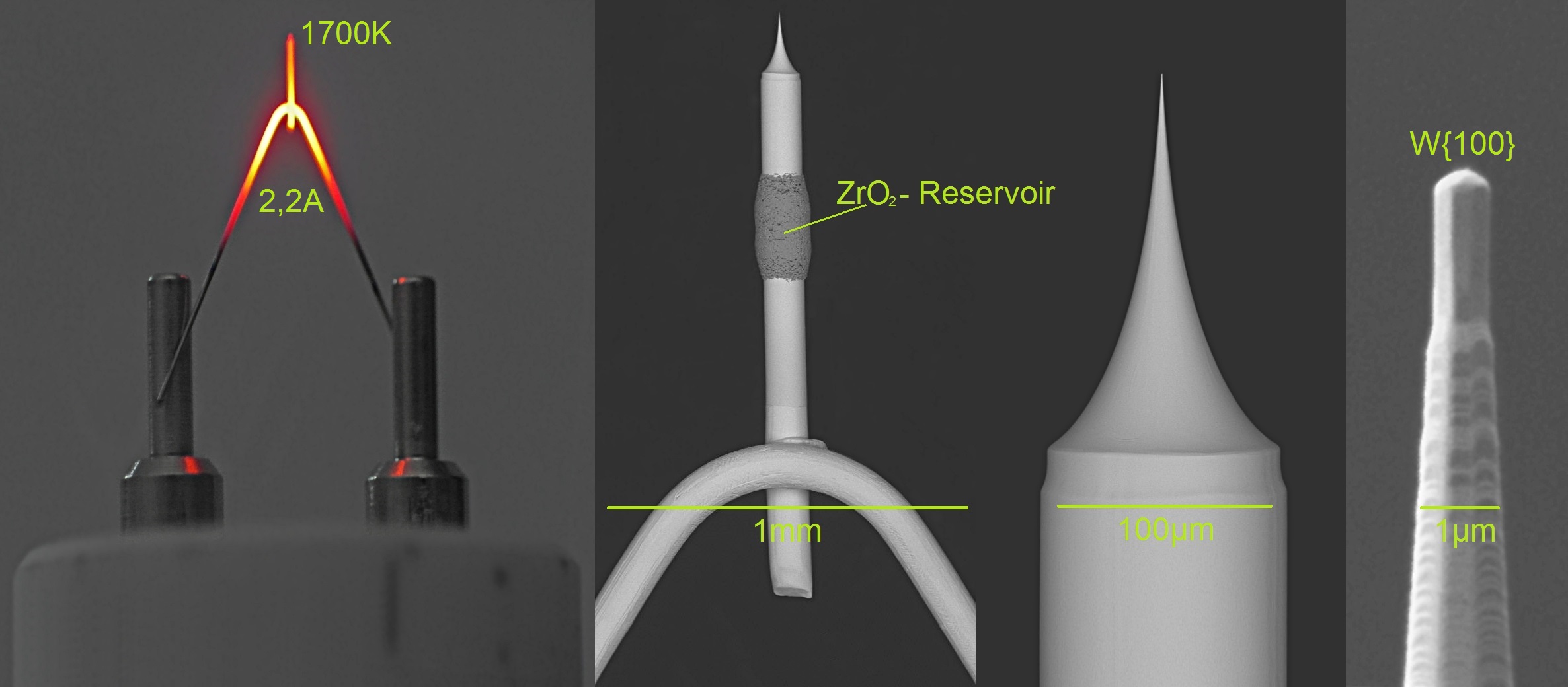

In electron emission devices, especially

In electron emission devices, especially electron gun

An electron gun (also called electron emitter) is an electrical component in some vacuum tubes that produces a narrow, collimated electron beam that has a precise kinetic energy. The largest use is in cathode-ray tubes (CRTs), used in nearl ...

s, the thermionic electron emitter will be biased negative relative to its surroundings. This creates an electric field of magnitude ''E'' at the emitter surface. Without the field, the surface barrier seen by an escaping Fermi-level electron has height ''W'' equal to the local work-function. The electric field lowers the surface barrier by an amount Δ''W'', and increases the emission current. This is known as the Schottky effect (named for Walter H. Schottky) or field enhanced thermionic emission. It can be modeled by a simple modification of the Richardson equation, by replacing ''W'' by (''W'' − Δ''W''). This gives the equation

:

:

where ''ε''0 is the electric constant (also, formerly, called the vacuum permittivity

Vacuum permittivity, commonly denoted (pronounced "epsilon nought" or "epsilon zero"), is the value of the absolute dielectric permittivity of classical vacuum. It may also be referred to as the permittivity of free space, the electric const ...

).

Electron emission that takes place in the field-and-temperature-regime where this modified equation applies is often called Schottky emission. This equation is relatively accurate for electric field strengths lower than about 108 V m−1. For electric field strengths higher than 108 V m−1, so-called Fowler-Nordheim (FN) tunneling begins to contribute significant emission current. In this regime, the combined effects of field-enhanced thermionic and field emission can be modeled by the Murphy-Good equation for thermo-field (T-F) emission. At even higher fields, FN tunneling becomes the dominant electron emission mechanism, and the emitter operates in the so-called "cold field electron emission (CFE)" regime.

Thermionic emission can also be enhanced by interaction with other forms of excitation such as light. For example, excited Cs-vapours in thermionic converters form clusters of Cs- Rydberg matter which yield a decrease of collector emitting work function from 1.5 eV to 1.0–0.7 eV. Due to long-lived nature of Rydberg matter this low work function remains low which essentially increases the low-temperature converter's efficiency.

Photon-enhanced thermionic emission

Photon-enhanced thermionic emission (PETE) is a process developed by scientists at Stanford University that harnesses both the light and heat of the sun to generate electricity and increases the efficiency of solar power production by more than twice the current levels. The device developed for the process reaches peak efficiency above 200 °C, while most siliconsolar cell

A solar cell, or photovoltaic cell, is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect, which is a physical and chemical phenomenon.parabolic dish

A parabolic (or paraboloid or paraboloidal) reflector (or dish or mirror) is a reflective surface used to collect or project energy such as light, sound, or radio waves. Its shape is part of a circular paraboloid, that is, the surface generate ...

collectors, which reach temperatures up to 800 °C. Although the team used a gallium nitride

Gallium nitride () is a binary III/ V direct bandgap semiconductor commonly used in blue light-emitting diodes since the 1990s. The compound is a very hard material that has a Wurtzite crystal structure. Its wide band gap of 3.4 eV affords i ...

semiconductor in its proof-of-concept device, it claims that the use of gallium arsenide can increase the device's efficiency to 55–60 percent, nearly triple that of existing systems, and 12–17 percent more than existing 43 percent multi-junction solar cells.

See also

*Space charge

Space charge is an interpretation of a collection of electric charges in which excess electric charge is treated as a continuum of charge distributed over a region of space (either a volume or an area) rather than distinct point-like charges. Thi ...

References

External links

How vacuum tubes really work with a section on thermionic emission, with equations

john-a-harper.com.

Thermionic Phenomena and the Laws which Govern Them

Owen Richardson's Nobel lecture on thermionics. nobelprize.org. December 12, 1929. (PDF)

Derivations of thermionic emission equations from an undergraduate lab

csbsju.edu. {{Thomas Edison Atomic physics Electricity Energy conversion Vacuum tubes Thomas Edison