The Travels Of Marco Polo (comic Strip) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Book of the Marvels of the World'' ( Italian: , lit. 'The Million', possibly derived from Polo's nickname "Emilione"), in English commonly called ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', is a 13th-century travelogue written down by

The source of the title is debated. One view is it comes from the Polo family's use of the name ''Emilione'' to distinguish themselves from the numerous other Venetian families bearing the name Polo. A more common view is that the name refers to medieval reception of the travelog, namely that it was full of "a million" lies.

Modern assessments of the text usually consider it to be the record of an observant rather than imaginative or analytical traveller.

The source of the title is debated. One view is it comes from the Polo family's use of the name ''Emilione'' to distinguish themselves from the numerous other Venetian families bearing the name Polo. A more common view is that the name refers to medieval reception of the travelog, namely that it was full of "a million" lies.

Modern assessments of the text usually consider it to be the record of an observant rather than imaginative or analytical traveller.

Marco Polo was accompanied on his trips by his father and uncle (both of whom had been to China previously), though neither of them published any known works about their journeys. The book was translated into many European languages in Marco Polo's own lifetime, but the original manuscripts are now lost. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist. During copying and translating many errors were made, so there are many differences between the various copies.

According to the French philologist Philippe Ménard, there are six main versions of the book: the version closest to the original, in Franco-Venetian; a version in Old French; a version in Tuscan; two versions in

Marco Polo was accompanied on his trips by his father and uncle (both of whom had been to China previously), though neither of them published any known works about their journeys. The book was translated into many European languages in Marco Polo's own lifetime, but the original manuscripts are now lost. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist. During copying and translating many errors were made, so there are many differences between the various copies.

According to the French philologist Philippe Ménard, there are six main versions of the book: the version closest to the original, in Franco-Venetian; a version in Old French; a version in Tuscan; two versions in

Since its publication, many have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages viewed the book simply as a romance or fable, largely because of the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck who portrayed the Mongols as "barbarians" who appeared to belong to "some other world". Doubts have also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo's narrative of his travels in China, for example for his failure to mention a number of things and practices commonly associated with China, such as Chinese characters, tea,

Since its publication, many have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages viewed the book simply as a romance or fable, largely because of the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck who portrayed the Mongols as "barbarians" who appeared to belong to "some other world". Doubts have also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo's narrative of his travels in China, for example for his failure to mention a number of things and practices commonly associated with China, such as Chinese characters, tea,

Although Marco Polo was certainly the most famous, he was not the only nor the first European traveller to the

Although Marco Polo was certainly the most famous, he was not the only nor the first European traveller to the

volume 1volume 2index

* — (1903), * — (1903), * .

volume 1volume 2index

* * *

The Travels of Marco Polo

— ''Engineering Historical Memory'' (critical English translation, images, videos) General studies * * . * . * . * . * . * . * * Dissertations * Journal articles * * . * * * Newspaper and web articles * *

Google map link with Polo's Travels Mapped out (follows the Yule version of the original work)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Travels of Marco Polo, The 1290s books Italian literature Medieval literature Travel books Prison writings Marco Polo Books about Asia Italian non-fiction books Geography books History books about exploration

Rustichello da Pisa

Rustichello da Pisa, also known as Rusticiano (fl. late 13th century), was an Italian Romance (heroic literature), romance writer in Franco-Italian language. He is best known for co-writing Marco Polo's autobiography, ''The Travels of Marco Polo' ...

from stories told by Italian explorer Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

. It describes Polo's travels through Asia between 1271 and 1295, and his experiences at the court of Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of th ...

.

The book was written by romance writer Rustichello da Pisa, who worked from accounts which he had heard from Marco Polo when they were imprisoned together in Genoa. Rustichello wrote it in Franco-Venetian Franco-Italian, also known as Franco-Venetian or Franco-Lombard, was a literary language used in parts of northern Italy, from the mid-13th century to the end of the 14th century. It was employed by writers including Brunetto Latini and Rustichello ...

,Maria Bellonci, "Nota introduttiva", Il Milione di Marco Polo, Milano, Oscar Mondadori, 2003, p. XI TALIAN Talian may refer to:

*Talian dialect, a dialect spoken in Brazil

*Talian, Iran

Talian ( fa, طاليان, also Romanized as Tālīān and Ţālīān) is a village in Baraghan Rural District, Chendar District, Savojbolagh County, Alborz Province, ...

/ref> a literary language widespread in northern Italy between the subalpine belt and the lower Po between the 13th and 15th centuries. It was originally known as or ("''Description of the World''"). The book was translated into many European languages in Marco Polo's own lifetime, but the original manuscripts are now lost, and their reconstruction is a matter of textual criticism. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist, including in Old French, Tuscan, two versions in Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

, and two different versions in Latin.

From the beginning, there has been incredulity over Polo's sometimes fabulous stories, as well as a scholarly debate in recent times. Some have questioned whether Marco had actually travelled to China or was just repeating stories that he had heard from other travellers. Economic historian Mark Elvin concludes that recent work "demonstrates by specific example the ultimately overwhelming probability of the broad authenticity" of Polo's account, and that the book is, "in essence, authentic, and, when used with care, in broad terms to be trusted as a serious though obviously not always final, witness."

History

The source of the title is debated. One view is it comes from the Polo family's use of the name ''Emilione'' to distinguish themselves from the numerous other Venetian families bearing the name Polo. A more common view is that the name refers to medieval reception of the travelog, namely that it was full of "a million" lies.

Modern assessments of the text usually consider it to be the record of an observant rather than imaginative or analytical traveller.

The source of the title is debated. One view is it comes from the Polo family's use of the name ''Emilione'' to distinguish themselves from the numerous other Venetian families bearing the name Polo. A more common view is that the name refers to medieval reception of the travelog, namely that it was full of "a million" lies.

Modern assessments of the text usually consider it to be the record of an observant rather than imaginative or analytical traveller. Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

emerges as being curious and tolerant, and devoted to Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of th ...

and the dynasty that he served for two decades. The book is Polo's account of his travels to China, which he calls Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

(north China) and Manji (south China). The Polo party left Venice in 1271. The journey took three years after which they arrived in Cathay as it was then called and met the grandson of Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr />Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent)Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin

, ...

, Kublai Khan. They left China in late 1290 or early 1291 and were back in Venice in 1295. The tradition is that Polo dictated the book to a romance writer, Rustichello da Pisa

Rustichello da Pisa, also known as Rusticiano (fl. late 13th century), was an Italian Romance (heroic literature), romance writer in Franco-Italian language. He is best known for co-writing Marco Polo's autobiography, ''The Travels of Marco Polo' ...

, while in prison in Genoa between 1298 and 1299. Rustichello may have worked up his first Franco-Italian version from Marco's notes. The book was then named and in French, and in Latin.

Role of Rustichello

The British scholar Ronald Latham has pointed out that ''The Book of Marvels'' was in fact a collaboration written in 1298–1299 between Polo and a professional writer of romances, Rustichello of Pisa.Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pp. 7–20 from ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', London: Folio Society, 1958 p. 11. It is believed that Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote '' Devisement du Monde'' in theFranco-Venetian Franco-Italian, also known as Franco-Venetian or Franco-Lombard, was a literary language used in parts of northern Italy, from the mid-13th century to the end of the 14th century. It was employed by writers including Brunetto Latini and Rustichello ...

language.

Latham also argued that Rustichello may have glamorised Polo's accounts, and added fantastic and romantic elements that made the book a bestseller. The Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto had previously demonstrated that the book was written in the same "leisurely, conversational style" that characterised Rustichello's other works, and that some passages in the book were taken verbatim or with minimal modifications from other writings by Rustichello. For example, the opening introduction in ''The Book of Marvels'' to "emperors and kings, dukes and marquises" was lifted straight out of an Arthurian romance Rustichello had written several years earlier, and the account of the second meeting between Polo and Kublai Khan at the latter's court is almost the same as that of the arrival of Tristan at the court of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

at Camelot in that same book. Latham believed that many elements of the book, such as legends of the Middle East and mentions of exotic marvels, may have been the work of Rustichello who was giving what medieval European readers expected to find in a travel book.Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pp. 7–20 from ''The Travels of Marco Polo'', London: Folio Society, 1958 p. 12.

Role of the Dominican Order

Apparently, from the very beginning Marco's story aroused contrasting reactions, as it was received by some with a certain disbelief. The Dominican father was the author of a translation into Latin, in 1302, just a few years after Marco's return to Venice. Francesco Pipino solemnly affirmed the truthfulness of the book and defined Marco as a "prudent, honoured and faithful man". inaldo Fulin, Archivio Veneto, 1924, p. 255/ref> In his writings, the Dominican brother Jacopo d'Acqui explains why his contemporaries were skeptical about the content of the book. He also relates that before dying, Marco Polo insisted that "he had told only a half of the things he had seen". According to some recent research of the Italian scholar Antonio Montefusco, the very close relationship that Marco Polo cultivated with members of the Dominican Order in Venice suggests that local fathers collaborated with him for a Latin version of the book, which means that Rustichello's text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Order. Since Dominican fathers had among their missions that of evangelizing foreign peoples (cf. the role of Dominican missionaries in China and in the Indies), it is reasonable to think that they considered Marco's book as a trustworthy piece of information for missions in the East. The diplomatic communications between Pope Innocent IV and Pope Gregory X with the Mongols were probably another reason for this endorsement. At the time, there was open discussion of a possible Christian-Mongol alliance with an anti-Islamic function.Jean Richard, ''Histoire des Croisades'' (Paris: Fayard 1996), p.465 In fact, a Mongol delegate was solemnly baptised at theSecond Council of Lyon

:''The First Council of Lyon, the Thirteenth Ecumenical Council, took place in 1245.''

The Second Council of Lyon was the fourteenth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, convoked on 31 March 1272 and convened in Lyon, Kingdom of Arl ...

. At the council, Pope Gregory X promulgated a new Crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

to start in 1278 in liaison with the Mongols.

Contents

''The Travels'' is divided into four books. Book One describes the lands of the Middle East and Central Asia that Marco encountered on his way to China. Book Two describes China and the court of Kublai Khan. Book Three describes some of the coastal regions of the East: Japan, India, Sri Lanka, South-East Asia, and the east coast of Africa. Book Four describes some of the then-recent wars among the Mongols and some of the regions of the far north, like Russia. Polo's writings included descriptions of cannibals and spice-growers.Legacy

''The Travels'' was a rare popular success in an era before printing. The impact of Polo's book on cartography was delayed: the first map in which some names mentioned by Polo appear was in the '' Catalan Atlas of Charles V'' (1375), which included thirty names in China and a number of other Asian toponyms. In the mid-fifteenth century the cartographer of Murano, Fra Mauro, meticulously included all of Polo's toponyms in his 1450 map of the world. A heavily annotated copy of Polo's book was among the belongings of Columbus.Subsequent versions

Marco Polo was accompanied on his trips by his father and uncle (both of whom had been to China previously), though neither of them published any known works about their journeys. The book was translated into many European languages in Marco Polo's own lifetime, but the original manuscripts are now lost. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist. During copying and translating many errors were made, so there are many differences between the various copies.

According to the French philologist Philippe Ménard, there are six main versions of the book: the version closest to the original, in Franco-Venetian; a version in Old French; a version in Tuscan; two versions in

Marco Polo was accompanied on his trips by his father and uncle (both of whom had been to China previously), though neither of them published any known works about their journeys. The book was translated into many European languages in Marco Polo's own lifetime, but the original manuscripts are now lost. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist. During copying and translating many errors were made, so there are many differences between the various copies.

According to the French philologist Philippe Ménard, there are six main versions of the book: the version closest to the original, in Franco-Venetian; a version in Old French; a version in Tuscan; two versions in Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

; two different versions in Latin.

Version in Franco-Venetian

The oldest surviving Polo manuscript is in Franco-Venetian, which was a variety of Old French heavily flavoured with Venetian language, spread in Northern Italy in the 13th century; for Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, this "F" text is the basic original text, which he corrected by comparing it with the somewhat more detailed Italian of Ramusio, together with a Latin manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana.Version in Old French

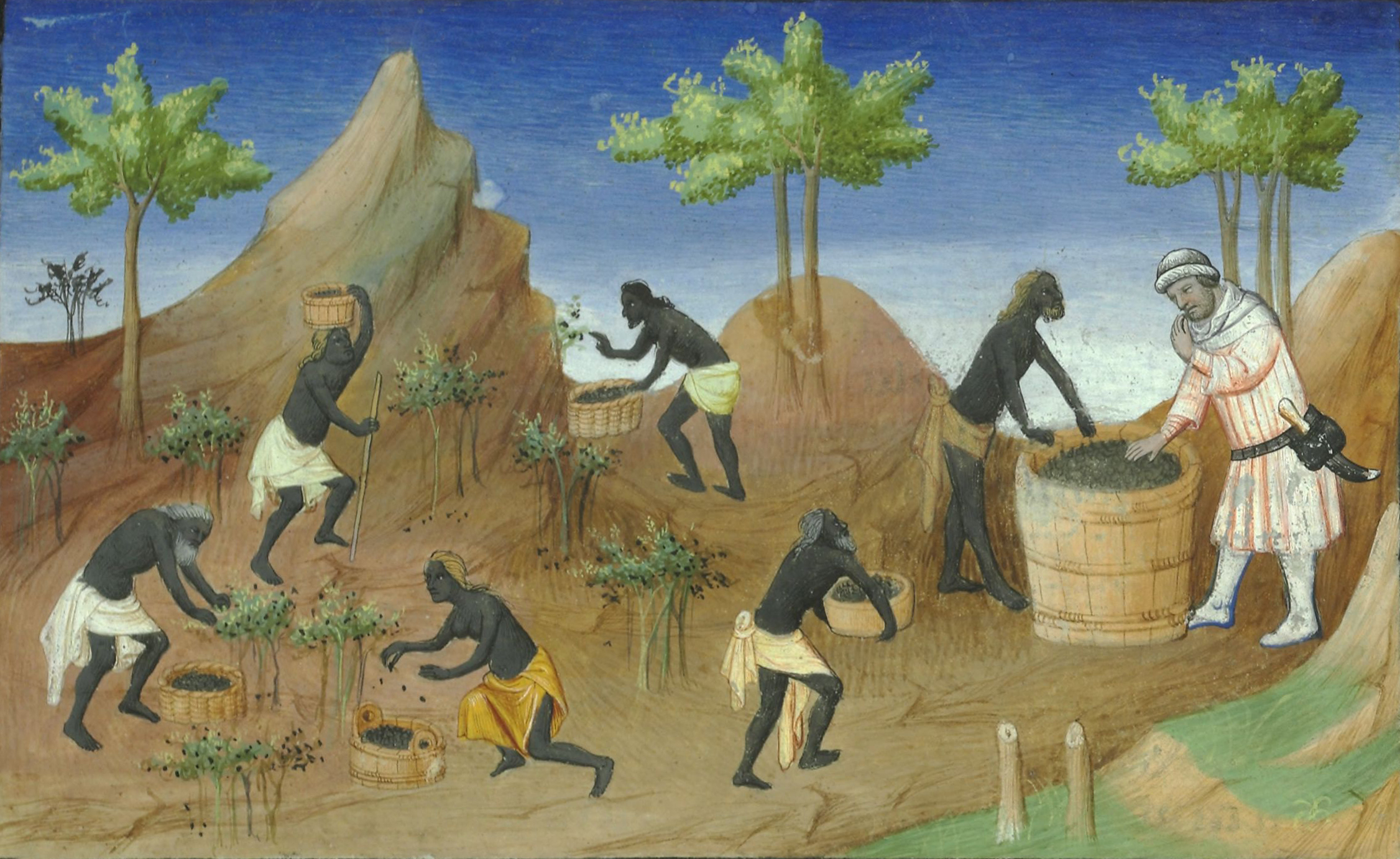

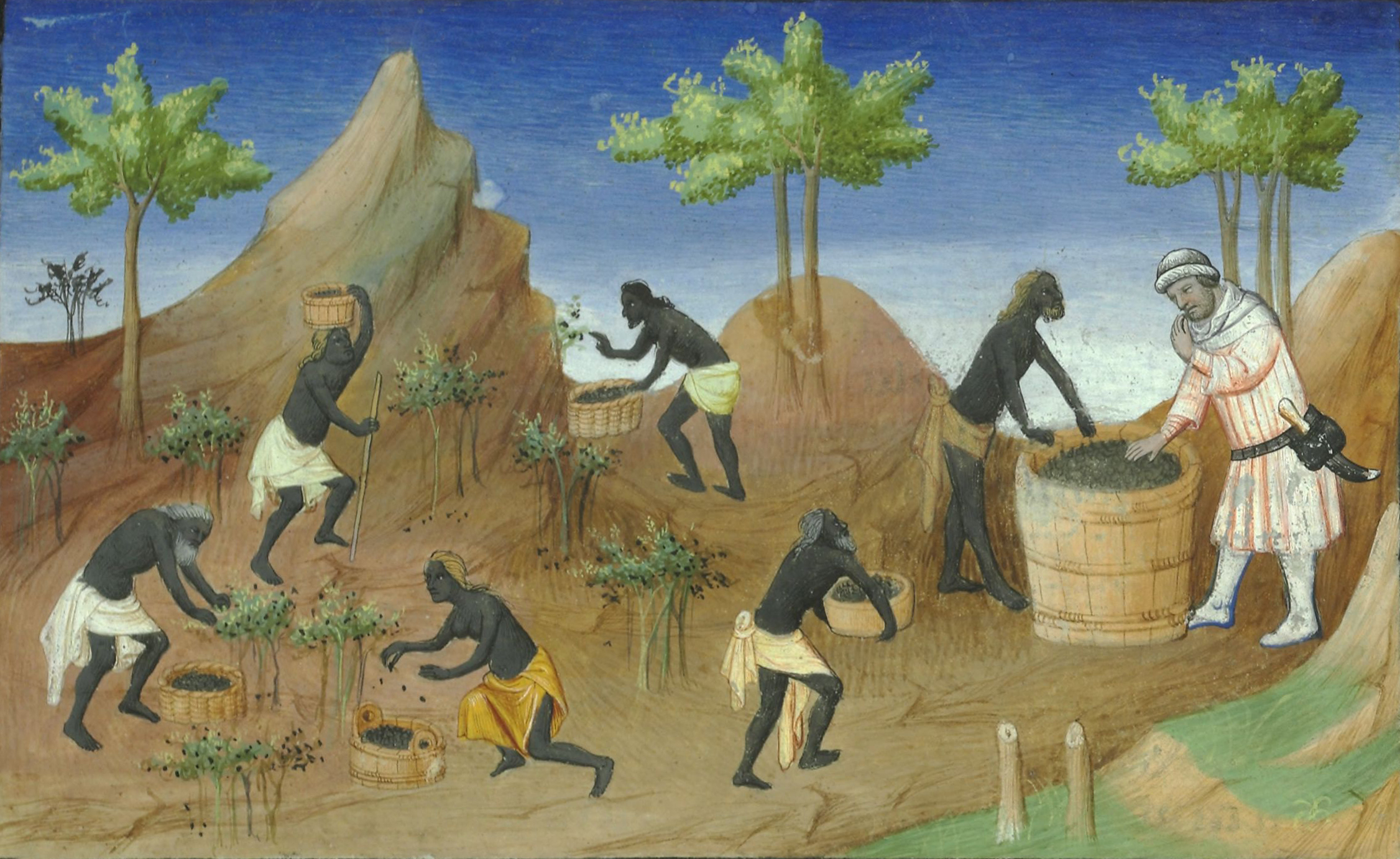

A version written in Old French, titled (The Book of Marvels). : This version counts 18 manuscripts, whose most famous is the Code Fr. 2810. Famous for its miniatures, the Code 2810 is in the French National Library. Another Old French Polo manuscript, dating to around 1350, is held by the National Library of Sweden. A critical edition of this version was edited in the 2000s by Philippe Ménard.Version in Tuscan

A version in Tuscan (Italian language) titled was written in Florence byMichele Ormanni

Michele (), is an Italian male given name, akin to the English male name Michael.

Michele (pronounced ), is also an English female given name that is derived from the French Michèle. It is a variant spelling of the more common (and identically ...

. It is found in the Italian National Library in Florence.

Other early important sources are the manuscript "R" (Ramusio's Italian translation first printed in 1559).

Version in Venetian

The version in Venetian dialect is full of mistakes and is not considered trustworthy.Versions in Latin

* One of the early manuscripts, , was a translation into Latin made by the Dominican brother Francesco Pipino in 1302, only three years after Marco's return to Venice. This testifies the deep interest the Dominican Order had in the book. According to recent research by the Italian scholar Antonio Montefusco, the very close relationship Marco Polo cultivated with members of the Dominican Order in Venice suggests that Rustichello's text was translated into Latin for a precise will of the Order, which had among its missions that of evangelizing foreign peoples (cf. the role of Dominican missionaries in China and in the Indies). This Latin version is conserved by 70 manuscripts. * Another Latin version called "Z" is conserved only by one manuscript, which is to be found in Toledo, Spain. This version contains about 300 small curious additional facts about religion and ethnography in the Far East. Experts wondered whether these additions were from Marco Polo himself.Critical editions

The first attempt to collate manuscripts and provide a critical edition was in a volume of collected travel narratives printed at Venice in 1559. The editor, Giovan Battista Ramusio, collated manuscripts from the first part of the fourteenth century, which he considered to be "" ("perfectly correct"). The edition of Benedetto, , under the patronage of the (Florence: Olschki, 1928), collated sixty additional manuscript sources, in addition to some eighty that had been collected by Henry Yule, for his 1871 edition. It was Benedetto who identified Rustichello da Pisa, as the original compiler oramanuensis

An amanuensis () is a person employed to write or type what another dictates or to copy what has been written by another, and also refers to a person who signs a document on behalf of another under the latter's authority. In one example Eric Fenby ...

, and his established text has provided the basis for many modern translations: his own in Italian (1932), and Aldo Ricci's ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (London, 1931).

The first English translation is the Elizabethan version by John Frampton published in 1579, ''The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo'', based on Santaella's Castilian translation of 1503 (the first version in that language).

A. C. Moule and Paul Pelliot published a translation under the title ''Description of the World'' that uses manuscript F as its base and attempts to combine the several versions of the text into one continuous narrative while at the same time indicating the source for each section (London, 1938).

An introduction to Marco Polo is Leonard Olschki, ''Marco Polo's Asia: An Introduction to His "Description of the World" Called "Il Milione"'', translated by John A. Scott (Berkeley: University of California) 1960; it had its origins in the celebrations of the seven hundredth anniversary of Marco Polo's birth.

Authenticity and veracity

Since its publication, many have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages viewed the book simply as a romance or fable, largely because of the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck who portrayed the Mongols as "barbarians" who appeared to belong to "some other world". Doubts have also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo's narrative of his travels in China, for example for his failure to mention a number of things and practices commonly associated with China, such as Chinese characters, tea,

Since its publication, many have viewed the book with skepticism. Some in the Middle Ages viewed the book simply as a romance or fable, largely because of the sharp difference of its descriptions of a sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck who portrayed the Mongols as "barbarians" who appeared to belong to "some other world". Doubts have also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo's narrative of his travels in China, for example for his failure to mention a number of things and practices commonly associated with China, such as Chinese characters, tea, chopstick

Chopsticks ( or ; Pinyin: ''kuaizi'' or ''zhu'') are shaped pairs of equal-length sticks of Chinese origin that have been used as kitchen and eating utensils in most of East and Southeast Asia for over three millennia. They are held in the domi ...

s, and footbinding

Foot binding, or footbinding, was the Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls in order to change their shape and size. Feet altered by footbinding were known as lotus feet, and the shoes made for these feet were kno ...

. In particular, his failure to mention the Great Wall of China had been noted as early as the middle of the seventeenth century. In addition, the difficulties in identifying many of the place names he used also raised suspicion about Polo's accounts. Many have questioned whether or not he had visited the places he mentioned in his itinerary, or he had appropriated the accounts of his father and uncle or other travelers, or doubted that he even reached China and that, if he did, perhaps never went beyond Khanbaliq

Khanbaliq or Dadu of Yuan () was the winter capital of the Yuan dynasty of China in what is now Beijing, also the capital of the People's Republic of China today. It was located at the center of modern Beijing. The Secretariat directly administ ...

(Beijing).

Historian Stephen G. Haw

Stephen G. Haw (born 1951) is a botanical taxonomist and historian, specializing in subjects relating to China. He is the author of several published books and a large number of periodical articles. His most important work relates to the taxonomy o ...

however argued that many of the "omissions" could be explained. For example, none of the other Western travelers to Yuan dynasty China at that time, such as Giovanni de' Marignolli

Giovanni de' Marignolli ( la, Johannes Marignola;. ), variously anglicized as John of Marignolli or John of Florence, was a notable 14th-century Catholic European traveller to medieval China and India.

Life

Early life

Giovanni was born, probab ...

and Odoric of Pordenone, mentioned the Great Wall, and that while remnants of the Wall would have existed at that time, it would not have been significant or noteworthy as it had not been maintained for a long time. The Great Walls were built to keep out northern invaders, whereas the ruling dynasty during Marco Polo's visit were those very northern invaders. The Mongol rulers whom Polo served also controlled territories both north and south of today's wall, and would have no reasons to maintain any fortifications that may have remained there from the earlier dynasties. He noted the Great Wall familiar to us today is a Ming structure built some two centuries after Marco Polo's travels. The Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berbers, Berber Maghrebi people, Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, ...

did mention the Great Wall, but when he asked about the wall while in China during the Yuan dynasty, he could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen it. Haw also argued that practices such as footbinding were not common even among Chinese during Polo's time and almost unknown among the Mongols. While the Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone who visited Yuan China mentioned footbinding (it is however unclear whether he was only relaying something he heard as his description is inaccurate), no other foreign visitors to Yuan China mentioned the practice, perhaps an indication that the footbinding was not widespread or was not practiced in an extreme form at that time. Marco Polo himself noted (in the Toledo manuscript) the dainty walk of Chinese women who took very short steps.

It has also been pointed out that Polo's accounts are more accurate and detailed than other accounts of the periods. Polo had at times denied the "marvelous" fables and legends given in other European accounts, and also omitted descriptions of strange races of people then believed to inhabit eastern Asia and given in such accounts. For example, Odoric of Pordenone said that the Yangtze river flows through the land of pygmies only three spans high and gave other fanciful tales, while Giovanni da Pian del Carpine spoke of "wild men, who do not speak at all and have no joints in their legs", monsters who looked like women but whose menfolk were dogs, and other equally fantastic accounts. Despite a few exaggerations and errors, Polo's accounts are relatively free of the descriptions of irrational marvels, and in many cases where present (mostly given in the first part before he reached China), he made a clear distinction that they are what he had heard rather than what he had seen. It is also largely free of the gross errors in other accounts such as those given by the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta who had confused the Yellow River with the Grand Canal and other waterways, and believed that porcelain was made from coal.

Many of the details in Polo's accounts have been verified. For example, when visiting Zhenjiang in Jiangsu, China, Marco Polo noted that a large number of Christian church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym fo ...

es had been built there. His claim is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdia

Sogdia (Sogdian language, Sogdian: ) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also ...

n named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top:Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zinda, ...

founded six Nestorian Christian churches there in addition to one in Hangzhou during the second half of the 13th century. Nestorian Christianity had existed in China since the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) when a Persian monk named Alopen came to the capital Chang'an in 653 to proselytize, as described in a dual Chinese and Syriac language

The Syriac language (; syc, / '), also known as Syriac Aramaic (''Syrian Aramaic'', ''Syro-Aramaic'') and Classical Syriac ܠܫܢܐ ܥܬܝܩܐ (in its literary and liturgical form), is an Aramaic language, Aramaic dialect that emerged during ...

inscription from Chang'an (modern Xi'an) dated to the year 781.

In 2012, the University of Tübingen sinologist

Sinology, or Chinese studies, is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of China primarily through Chinese philosophy, language, literature, culture and history and often refers to Western scholarship. Its origin "may be traced to the ex ...

and historian Hans Ulrich Vogel released a detailed analysis of Polo's description of currencies, salt production and revenues, and argued that the evidence supports his presence in China because he included details which he could not have otherwise known. Vogel noted that no other Western, Arab, or Persian sources have given such accurate and unique details about the currencies of China, for example, the shape and size of the paper, the use of seals, the various denominations of paper money as well as variations in currency usage in different regions of China, such as the use of cowry shells in Yunnan, details supported by archaeological evidence and Chinese sources compiled long after Polo's had left China. His accounts of salt production and revenues from the salt monopoly are also accurate, and accord with Chinese documents of the Yuan era. Economic historian Mark Elvin, in his preface to Vogel's 2013 monograph, concludes that Vogel "demonstrates by specific example after specific example the ultimately overwhelming probability of the broad authenticity" of Polo's account. Many problems were caused by the oral transmission of the original text and the proliferation of significantly different hand-copied manuscripts. For instance, did Polo exert "political authority" () in Yangzhou or merely "sojourn" () there? Elvin concludes that "those who doubted, although mistaken, were not always being casual or foolish", but "the case as a whole had now been closed": the book is, "in essence, authentic, and, when used with care, in broad terms to be trusted as a serious though obviously not always final, witness".

Other travellers

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

who subsequently wrote an account of his experiences. Earlier thirteenth-century European travellers who journeyed to the court of the Great Khan were André de Longjumeau, William of Rubruck and Giovanni da Pian del Carpine with Benedykt Polak. None of them however reached China itself. Later travelers such as Odoric of Pordenone and Giovanni de' Marignolli reached China during the Yuan dynasty and wrote accounts of their travels.

The Moroccan merchant Ibn Battuta travelled through the Golden Horde and China subsequently in the early-to-mid-14th century. The 14th-century author John Mandeville wrote an account of journeys in the East, but this was probably based on second-hand information and contains much apocryphal information.

Footnotes

Further reading

Translations * * * *volume 1

* — (1903), * — (1903), * .

volume 1

* * *

The Travels of Marco Polo

— ''Engineering Historical Memory'' (critical English translation, images, videos) General studies * * . * . * . * . * . * . * * Dissertations * Journal articles * * . * * * Newspaper and web articles * *

External links

Google map link with Polo's Travels Mapped out (follows the Yule version of the original work)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Travels of Marco Polo, The 1290s books Italian literature Medieval literature Travel books Prison writings Marco Polo Books about Asia Italian non-fiction books Geography books History books about exploration