The Holocaust in Italy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

was the persecution, deportation, and murder of Jews between 1943 and 1945 in the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

, the part of the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

occupied by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

after the Italian surrender on September 8, 1943, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

The oppression of Italian Jews began in 1938 with the enactment of Racial Laws

Anti-Jewish laws have been a common occurrence throughout Jewish history. Examples of such laws include special Jewish quotas, Jewish taxes and Disabilities (Jewish), Jewish "disabilities".

Some were adopted in the 1930s and 1940s in Nazi Germany ...

of segregation by the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

. Before the Italian surrender in 1943, however, Italy and the Italian occupation zones in Greece, France and Yugoslavia had been places of relative safety for local Jews and European Jewish refugees. This changed in September 1943, when German forces occupied the country, installed the puppet state of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

and immediately began persecuting and deporting the Jews found there. Italy had a pre-war Jewish population of 40,000 but, through evacuation and refugees, this number increased during the war. Of the estimated 44,500 Jews living in Italy before September 1943, 7,680 were murdered during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

(mostly at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

), while nearly 37,000 survived. In this, the Italian police and Fascist militia played an integral role as the Germans' accessories.

While most Italian concentration camps were police and transit camps, one camp, the Risiera di San Sabba

Risiera di San Sabba ( sl, Rižarna) is a five-storey brick-built compound located in Trieste, northern Italy, that functioned during World War II as a Nazi concentration camp for the detention and killing of political prisoners, and a transit ca ...

in Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

, was also an extermination camp. It is estimated that up to 5,000 political prisoners were murdered there.

More than 10,000 political prisoners and 40,000–50,000 captured Italian soldiers were interned and killed overall.

Situation prior to September 8, 1943

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Jews were a well-integrated minority in Italy. They had lived in the country for over two thousand years. AfterBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

seized power in 1922, Jews in Fascist Italy

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

initially suffered far less persecution, if any at all, compared to the Jews in Nazi Germany in the lead up to World War II. Some Fascist leaders, such as Achille Starace

Achille Starace (; 18 August 1889 – 29 April 1945) was a prominent leader of Fascist Italy before and during World War II.

Early life and career

Starace was born in Sannicola, province of Lecce, in southern Apulia. His father was a wine and oi ...

and Roberto Farinacci, were indeed antisemites, but others, such as Italo Balbo, were not, and until 1938 antisemitism was not the official policy of the party. Like the rest of Italians, Jews divided between fascists and anti-fascists. Some were sympathetic to the regime, joined the party and occupied significant offices and positions in politics and economy ( Aldo Finzi, Renzo Ravenna

Renzo, the diminutive of Lorenzo, is an Italian masculine given name and a surname.

Given name

Notable people named Renzo include the following:

*Renzo Alverà (1933–2005), Italian bobsledder

*Renzo Arbore (born 1937), Italian TV host, show ...

, Margherita Sarfatti

Margherita Sarfatti (née Grassini; 8 April 1880 – 30 October 1961) was an Italian journalist, art critic, patron, collector, socialite, and prominent propaganda adviser of the National Fascist Party. She was Benito Mussolini's biographer as we ...

, Ettore Ovazza

Ettore Ovazza (21 March 1892, in Turin – 11 October 1943, in Intra) was an Italian Jewish banker. Believing that his privileged position would be restored after the war, Ovazza stayed on after the Germans marched into Italy. Together with his ...

, Guido Jung

Guido Jung (2 February 1876 – 25 December 1949) was a successful Jewish-born Italian banker and merchant from Sicily.

He was a member of the Grand Council of Fascism and served as Italian Minister of Finance from 1932-35 under Benito Mussoli ...

). Others were active in anti-fascist organizations (Carlo Rosselli

Carlo Alberto Rosselli (Rome, 16 November 1899Bagnoles-de-l'Orne, 9 June 1937) was an Italian political leader, journalist, historian, philosopher and anti-fascist activist, first in Italy and then abroad. He developed a theory of reformist, ...

, Nello Rosselli

Sabatino Enrico 'Nello' Rosselli (Rome, 29 November 1900 – Bagnoles-de-l'Orne, 9 June 1937) was an Italian Socialist leader and historian.

Biography

Rosselli was born in Rome to a prominent Jewish family. His parents were Giuseppe Emanuele "Joe ...

, Leone Ginzburg, Umberto Terracini

Umberto Elia Terracini (Genoa, 27 July 1895 – Rome, 6 December 1983) was an Italian politician.

Biography Early years

Terracini was born in Genoa on 27 July 1895 to a Jewish family originally from Piedmont. After completing his elementa ...

).

In 1938, under the Italian Racial Laws, Italian Jews lost their civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

, including those to property, education and employment. They were removed from government jobs, the armed forces, and public schools (both as teachers and students). To escape persecution, around 6,000 Italian Jews emigrated to other countries in 1938-39. Among them were intellectuals such as Emilio Segrè, Bruno Rossi

Bruno Benedetto Rossi (; ; 13 April 1905 – 21 November 1993) was an Italian experimental physicist. He made major contributions to particle physics and the study of cosmic rays. A 1927 graduate of the University of Bologna, he became in ...

, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Franco Modigliani

Franco Modigliani (18 June 1918 – 25 September 2003) was an Italian-American economist and the recipient of the 1985 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. He was a professor at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Carnegie Mellon Uni ...

, Arnaldo Momigliano

Arnaldo Dante Momigliano (5 September 1908 – 1 September 1987) was an Italian historian of classical antiquity, known for his work in historiography, and characterised by Donald Kagan as "the world's leading student of the writing of history i ...

, Ugo Fano

Ugo Fano (July 28, 1912 – February 13, 2001) was an Italian American physicist, notable for contributions to theoretical physics.

Biography

Ugo Fano was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Turin, Italy. His father was Gino Fano, a professo ...

, Robert Fano

Roberto Mario "Robert" Fano (11 November 1917 – 13 July 2016) was an Italian-American computer scientist and professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He became a student and working ...

, and many others. Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

also moved to the United States, as his wife was Jewish.

In June 1940, after the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the Fascist Italian government opened around 50 concentration camps. These were used predominantly to hold political prisoners but also around 2,200 Jews of foreign nationality (Italian Jews were not interned). The Jews in these camps were treated no differently than political prisoners. While living conditions and food were often basic, prisoners were not subject to violent treatment. The Fascist regime even allowed a Jewish-Italian organization (DELASEM Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants (Delegazione per l'Assistenza degli Emigranti Ebrei) or DELASEM, was an Italian and Jewish resistance organization that worked in Italy between 1939 and 1947. It is estimated that during World War I ...

) to operate legally in support of the Jewish internees.

Conditions for non-Jews were much worse. Italian authorities perceived that imprisoned Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

Places Australia

* Roma, Queensland, a town

** Roma Airport

** Roma Courthouse

** Electoral district of Roma, defunct

** Town of Roma, defunct town, now part of the Maranoa Regional Council

*Roma Street, Brisbane, a ...

were used to a harsh life, and they received much lower food allowances and more basic accommodation. After the occupation of Greece and Yugoslavia in 1941, Italy opened concentration camps in its occupation zones there. These held a total of up to 150,000 people, mostly Slavs. Living conditions were very harsh, and the mortality rates in these camps far exceeded those of the camps in Italy.

Unlike Jews in other Axis-aligned

In geometry, an axis-aligned object (axis-parallel, axis-oriented) is an object in ''n''-dimensional space whose shape is aligned with the coordinate axes of the space.

Examples are axis-aligned rectangles (or hyperrectangles), the ones with edge ...

countries, no Jews in Italy or Italian-occupied areas were murdered or deported to concentration camps in Germany before September 1943. In the territories occupied by the Italian Army in Greece, France and Yugoslavia, Jews even found protection from persecution. The Italian Army actively protected Jews in occupation zones, to the frustration of Nazi Germany, and to the point where the Italian sector in Croatia was referred to as the "Promised Land". Up to September 1943, Germany made no serious attempt to force Mussolini and Fascist Italy into handing over Italian Jews. It was nevertheless irritated with the Italian refusal to arrest and deport its Jewish population, feeling it encouraged other countries allied with the Axis powers to refuse as well.

On July 25, 1943, with the fall of the Fascist Regime and the arrest of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, the situation in the Italian concentration camps changed. Inmates, including Jewish prisoners, were gradually released. However, this process was not completed by the time German authorities took over the camps in northern-central Italy on September 8, 1943. Luckily, hundreds of Jewish refugees who were imprisoned in the major camps in the South (Campagna internment camp

Campagna internment camp, located in Campagna, a town near Salerno in Southern Italy, was an internment camp for Jews and foreigners established by Benito Mussolini in 1940.

The first internees were 430 men captured in different parts of Italy ...

and Ferramonti di Tarsia

Ferramonti di Tarsia, also known as Ferramonti, was an Italian internment camp used to intern political dissidents and ethnic minorities. It was located in the municipality of Tarsia, near Cosenza, in Calabria. It was the largest of the fifteen in ...

) were liberated by the Allies before the arrival of the Germans, but 43,000 Jews (35,000 Italians and 8,000 refugees from other countries) were trapped in the territories now under control of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

.

In general, the fate and persecution of Jews in Italy between 1938 and 1943 has received only very limited attention in the Italian media. Lists of Jews drawn up to enforce the racial laws would be used to round them up after the Italian surrender on September 8, 1943.

The Holocaust in Italy

The murdering of Jews in Italy began on September 8, 1943, after German troops seized control of Northern and Central Italy, freedBenito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

from prison and installed him as the head of the puppet state of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

.

Organisation

Tasked with overseeing SS operations and, thereby, the final solution, the genocide of the Jews, was SS-'' Obergruppenführer''Karl Wolff

Karl Friedrich Otto Wolff (13 May 1900 – 17 July 1984) was a German SS functionary who served as Chief of Personal Staff Reichsführer-SS (Heinrich Himmler) and an SS liaison to Adolf Hitler during World War II. He ended the war as the Supre ...

, who was appointed as the Supreme SS and Police Leader in Italy. Wolff assembled a group of SS personnel under him with vast experience in the extermination of Jews in Eastern Europe. Odilo Globocnik, appointed as Higher SS and Police Leader for the Adriatic coastal area, was responsible for the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews and Gypsies in Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of t ...

, Poland, before being sent to Italy. Karl Brunner was appointed as SS and Police Leader in Bolzano

Bolzano ( or ; german: Bozen, (formerly ); bar, Bozn; lld, Balsan or ) is the capital city of the province of South Tyrol in northern Italy. With a population of 108,245, Bolzano is also by far the largest city in South Tyrol and the third la ...

, South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous province

, image_skyline =

, image_alt ...

, Willy Tensfeld

Willy Tensfeld (27 November 1893 – 2 September 1982) was a German SS-'' Brigadeführer'' and ''Generalmajor'' of the Police. He served in several SS and Police Leader positions in occupied Ukraine and Italy during the Second World War.

Early ...

in Monza

Monza (, ; lmo, label=Lombard language, Lombard, Monça, locally ; lat, Modoetia) is a city and ''comune'' on the River Lambro, a tributary of the Po River, Po in the Lombardy region of Italy, about north-northeast of Milan. It is the capit ...

for upper and western Italy and Karl-Heinz Bürger

Karl-Heinz Bürger (16 February 1904 – 2 December 1988) was a German SS functionary who held positions as SS and Police Leader during the Nazi era.

Career

Bürger became a member of the brownshirt SA in June 1923, taking part in the Beer ...

was placed in charge of anti-partisan operations.

The security police and the '' Sicherheitsdienst'' (SD) came under the command of Wilhelm Harster

Wilhelm Harster (21 July 1904 – 25 December 1991) was a German policeman and war criminal. A high-ranking member in the Schutzstaffel, SS and a Holocaust perpetrator during the Nazi era, he was twice convicted for his crimes by the Netherlands a ...

, based in Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Northern Italy, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and the ...

. He had held the same position in the Netherlands. Theodor Dannecker

Theodor Denecke (also spelled Dannecker) (27 March 1913 – 10 December 1945) was a German SS-captain (), a key aide to Adolf Eichmann in the deportation of Jews during World War II.

A trained lawyer Denecke first served at the Reich Security M ...

, previously active in the deportation of Greek Jews in the part of Greece occupied by Bulgaria, was made chief of the ''Judenreferat

The or (German plural: ; ), variously translated as Jewish advisers or Jewish experts, were Nazi SS officials who supervised anti-Jewish legislation and the deportations of Jews in the countries under their responsibility. Key architects of the ...

'' of the SD and was tasked with the deportation of the Italian Jews. Not seen as efficient enough, he was replaced by Friedrich Boßhammer

Friedrich Boßhammer (1906–1972) was a German jurist, SS-''Sturmbannführer'' and close associate of Adolf Eichmann, responsible for the deportation of the Italian Jews to extermination camps from January 1944 until the end of the war in Europ ...

, who like Dannecker, was closely associated with Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

''

''

Martin Sandberger was appointed as the head of the

* 2007 - ''

Database of the Italian Shoah victims

{{Europe in topic, The Holocaust in

Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

in Verona and played a vital role in the arrest and deportation of the Italian Jews.

As in other German-occupied areas, and in the Reich Security Main Office

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and ''Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Nazi ...

itself, the persecution of the Nazis' undesirable minorities and political opponents fell under Section IV of the Security Police and SD. In turn, Section IV was subdivided into further departments, of which department IV–4b was responsible for Jewish affairs. Dannecker, then Boßhammer headed this department.

The Congress of Verona

The attitude of the Italian Fascists towards Italian Jews changed drastically in November 1943, after the Fascist authorities declared them to be of "enemy nationality" during the Congress of Verona and began to participate actively in the prosecution and arrest of Jews. Initially, after the Italian surrender, the Italian police had only assisted in the round-up of Jews when requested to do so by German authorities. With the Manifest of Verona, in which Jews were declared foreigners, and in times of war enemies, this changed.Police Order No. 5

The RSI Police Order No. 5 ( it, Ordinanza di polizia RSI n.5) was an order issued on 30 November 1943 in the Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, the RSI) to the Italian police in German-occupied northern Italy to arrest all ...

on November 30, 1943, issued by Guido Buffarini Guidi, minister of the interior of the RSI, ordered the Italian police to arrest Jews and confiscate their property. This order, however, exempted Jews over the age of 70 or of mixed marriages, which frustrated the Germans who wanted to arrest and deport all Italian Jews.

Deportation and murder

The arrest and deportation of Jews in German-occupied Italy can be separated into two distinct phases. The first, under Dannecker, from September 1943 to January 1944, saw mobile ''s'' target Jews in major Italian cities. The second phase took place under Boßhammer, who had replaced Dannecker in early 1944. Boßhammer set up a centralised persecution system, using all available German and Fascist Italian police resources, to arrest and deport Italian Jews. The arrest of Jewish Italians and Jewish refugees began almost immediately after the surrender, in October 1943. This took place in all major Italian cities under German control, albeit with limited success. The Italian police offered little cooperation, and ninety percent of Rome's 10,000 Jews escaped arrest. Arrested Jews were taken to the transit camps atBorgo San Dalmazzo

Borgo San Dalmazzo ( oc, Lo Borg Sant Dalmatz) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Cuneo in the Italian region Piedmont, located about south of Turin and about southwest of Cuneo.

Borgo San Dalmazzo takes its name from Saint Dalm ...

, Fossoli

Fossoli () is an Italian village and hamlet (''frazione'') of Carpi, a city and municipality of the province of Modena, Emilia-Romagna. It is infamous for the homonym concentration camp and has a population of about 4400.

History

Born as a rura ...

and Bolzano

Bolzano ( or ; german: Bozen, (formerly ); bar, Bozn; lld, Balsan or ) is the capital city of the province of South Tyrol in northern Italy. With a population of 108,245, Bolzano is also by far the largest city in South Tyrol and the third la ...

, and from there to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

. Of the 4,800 deported from the camps by the end of 1943 only 314 survived.

Approximately half of all Jews arrested during the Holocaust in Italy were arrested in 1944 by the Italian police.

Altogether, by the end of the war, almost 8,600 Jews from Italy and Italian-controlled areas in France and Greece were deported to Auschwitz; all but 1,000 were murdered. Only 506 were sent to other camps (Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück, and Flossenbürg) as hostages or political prisoners. Among them were a few hundred Jews from Libya, an Italian colony before the war, who had been deported to mainland Italy in 1942, and were sent to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Most of them held British and French citizenship and most survived the war.

A further 300 Jews were shot or died of other causes in transit camps in Italy. Of those executed in Italy, almost half were murdered at the Ardeatine massacre in March 1944 alone. The 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler

The 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler or SS Division Leibstandarte, abbreviated as LSSAH, (german: 1. SS-Panzerdivision "Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler") began as Adolf Hitler's personal bodyguard unit, responsible for guardin ...

murdered over 50 Jewish civilians, refugees and Italian nationals, at the Lake Maggiore massacres—the first massacres of Jews by Germany in Italy during the war. These were committed immediately after the Italian surrender, and the bodies sunk in the lake. This occurred despite strict orders at the time not to commit any violence against the civilian population.

In the nineteen months of German occupation, from September 1943 to May 1945, twenty percent of Italy's pre-war Jewish population was murdered by the Nazis. The actual Jewish population in Italy during the war was, however, higher than the initial 40,000 as the Italian government had evacuated 4,000 Jewish refugees from its occupation zones to southern Italy alone. By September 1943, 43,000 Jews were present in northern Italy and, by the end of the war, 40,000 Jews in Italy had survived the Holocaust.

Romani people

Unlike Italian Jews, theRomani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have diaspora populations located worldwide, with sig ...

faced discrimination by Fascist Italy almost from the start of the regime. In 1926 it ordered that all "foreign Gypsies" should be expelled from the country and, from September 1940, Romani people of Italian nationality were held in designated camps. With the start of the German occupation many of these camps came under German control. The impact the German occupation had on the Romani people in Italy has seen little research. The number of Romani who were murdered in Italian camps or were deported to concentration camps is uncertain. The number of Romani people who were killed from hunger and exposure during the Fascist Italian period is also unknown but is estimated to be in the thousands.

While Italy observes January 27 as Remembrance Day for the Holocaust and its Jewish Italian victims, efforts to extend this official recognition to the Italian Romani people murdered by the Fascist regime, or deported to extermination camps, have been rejected.

Role of the Catholic Church and the Vatican

Before the Raid of the Ghetto of Rome Germany had been warned that such an action could raise the displeasure ofPope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

, but the pope never spoke out against the deportation of the Jews of Rome during the war, something that has since sparked controversy

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opposite d ...

. At the same time, members of the Catholic Church provided assistance to Jews and helped them survive the Holocaust in Italy.

Camps

German and Italian run transit camps for Jews, political prisoners and forced labour existed in Italy. These included: *Bolzano Transit Camp

, known for =

, location = Bolzano, Operationszone Alpenvorland

, coordinates =

, built by =

, operated by = SS

, commandant = Wilhelm Harster Karl Friedrich Titho

, original use ...

, in the Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

it, Trentino (man) it, Trentina (woman) or it, Altoatesino (man) it, Altoatesina (woman) or it, Sudtirolesegerman: Südtiroler (man)german: Südtirolerin (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title = Official ...

region, then part of the Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills

The Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills (german: Operationszone Alpenvorland (OZAV); it, Zona d'operazione delle Prealpi) was a Nazi German occupation zone in the sub-Alpine area in Italy during World War II.

Origin and geography

OZAV was ...

, operating as a German-controlled transit camp from summer 1944 to May 1945.

* Borgo San Dalmazzo concentration camp

Borgo San Dalmazzo was an internment camp operated by Nazi Germany in Borgo San Dalmazzo, Piedmont, Italy.

The camp operated under German control from September to November 1943 and, following that, under the control of the Italian Social Republ ...

, in the Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

region, operating as a German-controlled transit camp from September 1943 to November 1943 and, under Italian control, from December 1943 to February 1944.

* Fossoli di Carpi

The Fossoli camp ( it, Campo di Fossoli) was a concentration camp in Italy, established during World War II and located in the village Fossoli, Carpi, Emilia-Romagna. It began as a prisoner of war camp in 1942, later being a Jewish concentration ...

, in the Emilia-Romagna

egl, Emigliàn (man) egl, Emiglièna (woman) rgn, Rumagnòl (man) rgn, Rumagnòla (woman) it, Emiliano (man) it, Emiliana (woman) or it, Romagnolo (man) it, Romagnola (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title ...

region, operating as a prisoner of war camp under Italian control from May 1942 to September 1943, then as a transit camp, still under Italian control until March 1944 and, from then until November 1944 under German control.

Apart from these transit camps, Germany also operated the Risiera di San Sabba

Risiera di San Sabba ( sl, Rižarna) is a five-storey brick-built compound located in Trieste, northern Italy, that functioned during World War II as a Nazi concentration camp for the detention and killing of political prisoners, and a transit ca ...

camp in Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

, then part of the Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral, which simultaneously functioned as an extermination and transit camp. It was the only extermination camp in Italy during World War II. It operated from October 1943 to April 1945, with up to 5,000 people murdered there, most of those being political prisoners.

In addition to the designated camps, Jews and political prisoners were held in common prisons, like the San Vittore Prison

San Vittore is a prison in the city center of Milan, Italy.

Its construction started in 1872 and opened on 7 July 1879.

The prison has place for 600 inmates, but it had 1036 prisoners in 2017.

History

The construction of the new prison was de ...

in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, which gained notoriety during the war through the inhumane treatment of inmates by the SS guards and the torture carried out there. From San Vittore Prison, which served as a transit station for Jews arrested in northern Italy, prisoners were taken to the Milano Centrale railway station. There they were loaded onto freight cars on a secret track underneath the station and deported.

Looting of Jewish property

Apart from the extermination of the Jews, Nazi Germany was also extremely interested in appropriating Jewish property. A 2010 estimate set the value of Jewish property looted in Italy during the Holocaust between 1943 and 1945 at US$1 billion. Among the most priceless artifacts lost this way are the contents of theBiblioteca della Comunità Israelitica

The Biblioteca della Comunità Israelitica was the library of the Jewish community of Rome, Italy. Established in the early 20th century, it housed approximately 7,000 rare or unique books and manuscripts dating back to at least the 16th century. A ...

and the , the two Jewish libraries in Rome. Of the former, all of its contents remain missing, while some of the latter's contents were returned after the war.

Weeks before the Raid of the Ghetto of Rome, Herbert Kappler forced Rome's Jewish community to hand over of gold in exchange for safety. Despite doing so on September 28, 1943, over 1,000 of its members were arrested on October 16 and deported to Auschwitz where all but 16 were murdered.

Perpetrators

Very few German or Italian perpetrators of the Holocaust in Italy were tried or jailed after the war.Post-war trials

Of the war crimes committed by the Nazis in Italy the Ardeatine massacre saw arguably the most perpetrators convicted. High-rankingWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

officials Albert Kesselring, field marshal and commander of all Axis forces in the Mediterranean theatre, Eberhard von Mackensen, commander of the 14th German Army and Kurt Mälzer, military commander of Rome, were all sentenced to death. They were pardoned and released in 1952; Mälzer died before he could be released. Of the perpetrators from the SS, police chief of Rome Herbert Kappler was sentenced in 1948 but latter escaped jail to Germany. Erich Priebke and Karl Hass were eventually tried in 1997.

Heinrich Andergassen

Heinrich or Heinz Andergassen (30 July 1908 in Hall, Tyrol, Austro-Hungarian Empire – 26 July 1946 in Livorno, Italy) was an engineer, SS officer, and convicted war criminal who was executed for the torture and murder of seven Allied prisoners o ...

, a Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

officer who played a key role in the rounding up and deportations of 25 Jews from Merano

Merano (, , ) or Meran () is a city and ''comune'' in South Tyrol, northern Italy. Generally best known for its spa resorts, it is located within a basin, surrounded by mountains standing up to above sea level, at the entrance to the Passeier V ...

, 24 of whom later died, was never tried for his role in their deaths. However, he and three others were arrested by the U.S. Army for the murders of five American and two British POWs. Andergassen and two of his codefendants were executed for those murders on 26 July 1946.

Theodor Dannecker

Theodor Denecke (also spelled Dannecker) (27 March 1913 – 10 December 1945) was a German SS-captain (), a key aide to Adolf Eichmann in the deportation of Jews during World War II.

A trained lawyer Denecke first served at the Reich Security M ...

, in charge of the in Italy, committed suicide after being captured in December 1945, thereby avoiding a possible trial. His successor, Friedrich Boßhammer

Friedrich Boßhammer (1906–1972) was a German jurist, SS-''Sturmbannführer'' and close associate of Adolf Eichmann, responsible for the deportation of the Italian Jews to extermination camps from January 1944 until the end of the war in Europ ...

, disappeared at the end of the war in 1945 and subsequently worked as a lawyer in Wuppertal

Wuppertal (; "''Wupper Dale''") is, with a population of approximately 355,000, the seventh-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia as well as the 17th-largest city of Germany. It was founded in 1929 by the merger of the cities and to ...

. He was arrested in West Germany in 1968 and eventually sentenced to life in prison for his involvement in the deportation of 3,300 Jews from Italy to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

. During the Holocaust almost 8,000 of the 45,000 Jews living in Italy perished. During his trial over 200 witnesses were heard before he was sentenced in April 1972. He died a few months after the verdict without having spent any time in prison.

Karl Friedrich Titho

Karl Friedrich Titho (14 May 1911 – 18 June 2001) was a Germany military officer (ranked Untersturmführer, SS-Untersturmführer), who as commander of the Fossoli di Carpi and Bolzano Transit Camps oversaw the Cibeno Massacre in 1944. Titho was ...

's role as camp commander at the Fossoli di Carpi Transit Camp and the Bolzano Transit Camp in the deportation of Jewish camp inmates to Auschwitz was investigated by the state prosecutor in Dortmund

Dortmund (; Westphalian nds, Düörpm ; la, Tremonia) is the third-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne and Düsseldorf, and the eighth-largest city of Germany, with a population of 588,250 inhabitants as of 2021. It is the la ...

, Germany, in the early 1970s. The investigation was eventually terminated because it could not be proven that Titho knew the Jews deported to Auschwitz would be murdered there and that, given the late state of the war, they were murdered at all. He was also tried for the execution of 67 prisoners as reprisal for a partisan attack. It was ruled that this did not classify as being murder but, at most, as manslaughter. As such the charge had exceeded the statute of limitations. The two heads of the department investigating Titho had been members of the Nazi Party from an early date.

In 1964, six members of the division were charged with the Lago Maggiore massacre, carried out near Meina

Meina is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Novara in the Italian region of Piedmont, located about northwest of Milan, about northeast of Turin and about north of Novara, on the southern area of Lake Maggiore.

During World War II, ...

, as the statute of limitation laws in Germany at the time, twenty years for murder, meant the perpetrators could soon no longer be prosecuted. All the accused were found guilty, and three received life sentences for murder. Two others received a jail sentence of three years for having been accessories to the murders, while the sixth one died during the trial. The sentences were appealed and Germany's highest court, the ''Bundesgerichtshof

The Federal Court of Justice (german: Bundesgerichtshof, BGH) is the highest court in the system of ordinary jurisdiction (''ordentliche Gerichtsbarkeit'') in Germany, founded in 1950. It has its seat in Karlsruhe with two panels being situat ...

'', while not overturning the guilty verdict, ruled that the perpetrators had to be freed on a technicality. As the crimes had been committed in 1943 and were investigated by the division at that time without a conclusion, the usual start date for the statute of limitations for Nazi crimes, the date of the German surrender in 1945, did not apply. Since the defendants were charged more than twenty years after the 1943 massacre, the statute of limitations had expired.

This verdict caused much frustration for a younger generation of German state prosecutors who were interested in prosecuting Nazi crimes and their perpetrators. The ruling by the had further repercussions. It stated perpetrators could only be charged with murder if direct involvement in killing could be proven. In any other cases the charge could only be manslaughter. This meant that after 1960, under German law, the statute of limitations for manslaughter crimes had expired.

In 1969 Germany revoked the statute of limitations for murder altogether, allowing direct murder charges to be prosecuted indefinitely. This was not always applied to Nazi war crimes which were judged by pre-1969 laws. Some like Wolfgang Lehnigk-Emden escaped a jail sentence despite having been found guilty in the case of the Caiazzo massacre.

Italian role in the Holocaust

The role of Italians as collaborators of the Germans in the Holocaust in Italy has rarely been reflected upon in the country after World War II. A 2015 book by Simon Levis Sullam, a professor of modern history at the Ca' Foscari University of Venice, titled ''The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy'' examined the role of Italians in the genocide and found half of the Italian Jews murdered in the Holocaust were arrested by Italians and not Germans. Many of these arrests could only be carried out because of tip-offs by civilians. Sullam argued that Italy ignored what he called its "era of the executioner", rehabilitated Italian participants in the Holocaust through a 1946 amnesty, and continued to focus on its role as saviours of the Jews rather than to reflect on the persecution Jews suffered in Fascist Italy. Michele Sarfatti, one of most important historians of Italian Jewry in the country, stated that, in his view, up until the 1970s Italians generally believed their country was not involved in the Holocaust, and that it was exclusively the work of the German occupiers instead. This only began to change in the 1990s after the publication of by Jewish-Italian historian , and the Italian Racial Laws in book form in the early 2000s. These laws highlighted the fact that Italy's anti-Semitic laws were distinctly independent from those in Nazi Germany and, in some instances, more severe than the early anti-Semitic laws Germany had enacted.Commemoration

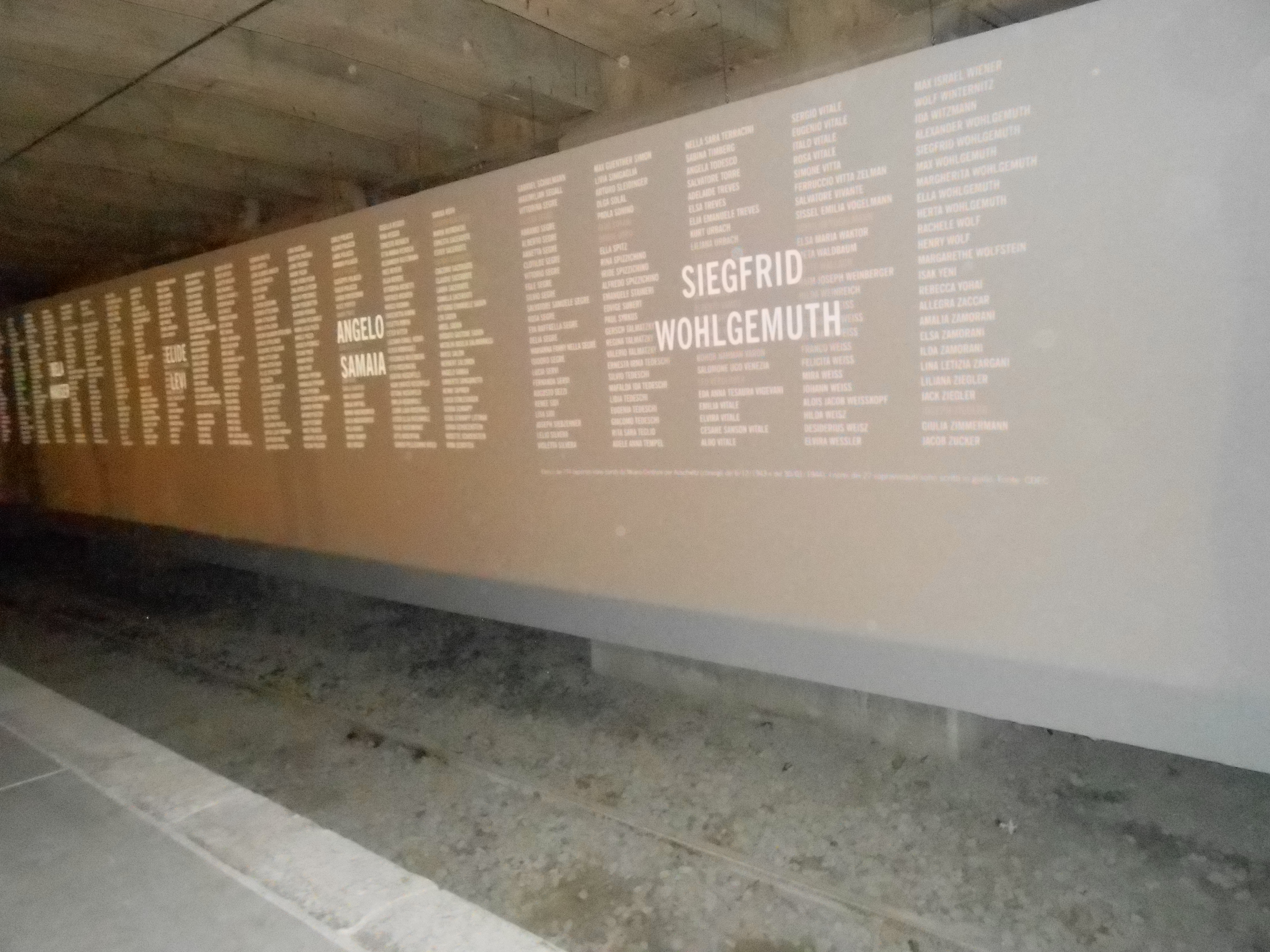

Memoriale della Shoah

The is a Holocaust memorial in Milano Centrale railway station, dedicated to the Jewish people deported from a secret platform underneath the station to the extermination camps. It was opened in January 2013.Borgo San Dalmazzo camp

No trace remains of the former Borgo San Dalmazzo concentration camp, but two monuments were erected to mark the events that took place there. In 2006 a memorial was erected at the Borgo San Dalmazzo railway station to commemorate the deportations. The memorial contains the names, ages and countries of origin of the victims as well as those of the few survivors. It also has some freight cars of the type used in the deportations.Fossoli Camp

In 1996 a foundation was formed to preserve the former camp. From 1998 to 2003 volunteers rebuilt the fencing around the ''Campo Nuovo'' and, in 2004, one of the barracks that was used to house Jewish inmates was reconstructed.Italian Righteous Among the Nations

As of 2018, 694 Italians have been recognised as Righteous Among the Nations, an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis. The first Italians to be honoured in this fashion were Don Arrigo Beccari, Doctor Giuseppe Moreali and Ezio Giorgetti in 1964. Arguably the most famous of these is cyclist Gino Bartali, winner of the 1938 and 1948Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in France, while also occasionally passing through nearby countries. Like the other Grand Tours (the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a España), it consists ...

, who was honoured posthumously in 2014 for his role in saving Italian Jews during the Holocaust, never having spoken about it during his lifetime.

The Italian Holocaust in literature and the media

Literature

Primo Levi

Primo Michele Levi (; 31 July 1919 – 11 April 1987) was an Italian chemist, partisan, writer, and Jewish Holocaust survivor. He was the author of several books, collections of short stories, essays, poems and one novel. His best-known works ...

, an Italian Jewish Auschwitz survivor, published his experience of the Holocaust in Italy in his books ''If This Is a Man

''If This Is a Man'' ( it, Se questo è un uomo ; United States title: ''Survival in Auschwitz'') is a memoir by Italians, Italian History of the Jews in Italy, Jewish writer Primo Levi, first published in 1947. It describes his arrest as a memb ...

'' and '' The Periodic Table''. The novel ''The Garden of the Finzi-Continis

''The Garden of the Finzi-Continis'' ( it, Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini) is an Italian historical novel by Giorgio Bassani, published in 1962. It chronicles the relationships between the narrator and the children of the Finzi-Contini family from ...

'' by Giorgio Bassani

Giorgio Bassani (4 March 1916 – 13 April 2000) was an Italian novelist, poet, essayist, editor, and international intellectual.

Biography

Bassani was born in Bologna into a prosperous Jewish family of Ferrara, where he spent his childhood wit ...

deals with the fate of the Jews of Ferrara

Ferrara (, ; egl, Fràra ) is a city and ''comune'' in Emilia-Romagna, northern Italy, capital of the Province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main stream ...

during the Holocaust and was made into a movie of the same name.

While Levi published his first works on the ''Shoah'' in the 1970s ( and ), the first implicit account of the Italian Holocaust can be found in the allusions made by Eugenio Montale in his and later in and , published in the section of . The subject matter was more explicitly developed by Salvatore Quasimodo and "in the prose poems

Prose poetry is poetry written in prose form instead of verse form, while preserving poetic qualities such as heightened imagery, parataxis, and emotional effects.

Characteristics

Prose poetry is written as prose, without the line breaks associ ...

collected by Umberto Saba

Umberto Saba (9 March 1883 – 26 August 1957) was an Italian poet and novelist, born Umberto Poli in the cosmopolitan Mediterranean port of Trieste when it was the fourth largest city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Poli assumed the pen name " ...

in " (1946).

* Appelbaum, Eva. ''Flight from WWII Yugoslavia and Coming of Age in Italy'' (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018)

* Bassani, Giorgio. ''The Garden of the Finzi-Continis'' (Everyman's Library, 2005)

* Bassani, Giorgio. ''The Novel of Ferrara'' (W. W. Norton & Company, 2018)

* Debenedetti, Giacomo. ''October 16, 1943 - Eight Jews'' (University of Notre Dame Press, 2001).

* Goldman, Louis. ''Friends for Life: The Story of a Holocaust Survivor and His Rescuers'' (Paulist Press, 2008)

* Harmon, Amy. ''From Sand and Ash'' (Lake Union Publishing, 2016)

* Levi, Primo. ''Survival in Auschwitz'' (Simon & Schuster, 1996)

* Levi, Primo. ''The Drowned and the Saved'' (Simon & Schuster, 2017)

* Levi, Primo. ''The Reawakening'' (Touchstone, 1995)

* Loy, Rosetta. ''First Words: A Childhood in Fascist Italy'' (Metropolitan Books, 2014)

* Marchione, Margherita. ''Yours Is a Precious Witness: Memoirs of Jews and Catholics in Wartime Italy'' (Paulist Press, 1997)

* Millu, Liana. ''Smoke over Birkenau'' (Northwestern University Press, 1998)

* Russo, Marisabina. ''I Will Come Back for You: A Family in Hiding in World War II'' (Dragonfly Books, 2014)

* Segre, Dan Vittorio. ''Memoirs of a Fortunate Jew: An Italian Story'' (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

* Stille, Alexander. ''Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families Under Fascism'' (Summit Books, 1991).

* Vitale Ben Bassat, Dafna. ''Vittoria: A Historical Drama Based on A True Story'' (2016).

* Wolff, Walter. ''Bad Times, Good People: A Holocaust Survivor Recounts His Life in Italy During World War II'' (Whittier Pubn, 1999)

Films

The Oscar-winners ''The Garden of the Finzi-Continis

''The Garden of the Finzi-Continis'' ( it, Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini) is an Italian historical novel by Giorgio Bassani, published in 1962. It chronicles the relationships between the narrator and the children of the Finzi-Contini family from ...

'' by Vittorio De Sica

Vittorio De Sica ( , ; 7 July 1901 – 13 November 1974) was an Italian film director and actor, a leading figure in the neorealist movement.

Four of the films he directed won Academy Awards: ''Sciuscià'' and ''Bicycle Thieves'' (honorary) ...

(1970) and '' Life Is Beautiful'' by Roberto Benigni (1997) are the two most famous movies on the Holocaust in Italy. Many more have been produced on the subject.Perra, Emiliano. ''Conflicts of Memory: The Reception of Holocaust Films and TV Programmes in Italy, 1945 to the Present'' (Peter Lang AG, 2010)

* 1949 - ''Monastero di Santa Chiara

Monastero di Santa Chiara is a church in San Marino. It belongs to the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Marino-Montefeltro

The Italian Catholic Diocese of San Marino-Montefeltro was until 1977 the historic Diocese of Montefeltro. It is a Latin ...

'', directed by Mario Sequi

Mario Sequi (1913-1992) was an Italian film director and screenwriter.Bayman p.59 A Sardinian by birth, he was married to the actress Lia Franca. He began his career in the 1930s as a production manager in the 1930s before becoming a director af ...

* 1960 - ''Everybody Go Home

''Everybody Go Home'' ( it, Tutti a casa) is a 1960 Italian comedy-drama film directed by Luigi Comencini. It features an international cast including the U.S. actors Martin Balsam, Alex Nicol and the Franco-Italian Serge Reggiani. Nino Manfred ...

'' (''Tutti a casa''), directed by Luigi Comencini

* 1961 - ''Gold of Rome

''L'oro di Roma'' (internationally released as ''Gold of Rome'') is a 1961 Italian war - drama film directed by Carlo Lizzani. The film is based on actual events surrounding the Nazi's raid of Rome's Jewish ghetto in October 1943.

Cast

*Gérar ...

'' (''L'oro di Roma''), directed by Carlo Lizzani

* 1970 - ''The Garden of the Finzi-Continis

''The Garden of the Finzi-Continis'' ( it, Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini) is an Italian historical novel by Giorgio Bassani, published in 1962. It chronicles the relationships between the narrator and the children of the Finzi-Contini family from ...

'' (''Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini''), directed by Vittorio De Sica

Vittorio De Sica ( , ; 7 July 1901 – 13 November 1974) was an Italian film director and actor, a leading figure in the neorealist movement.

Four of the films he directed won Academy Awards: ''Sciuscià'' and ''Bicycle Thieves'' (honorary) ...

* 1973 - ''Diario di un italiano

Diario (Italian, Spanish "Diary") and ''El Diario'' (Spanish, "The Daily") may refer to:

Newspapers, periodicals and websites

* ''El Diario'' (Argentina)

* ''Diario'' (Aruba)

* ''El Diario'' (La Paz), Bolivia

* ''Diario Extra'' (Costa Rica)

*''Di ...

'', directed by Sergio Capogna

Sergio may refer to:

* Sergio (given name), for people with the given name Sergio

* Sergio (carbonado), the largest rough diamond ever found

* ''Sergio'' (album), a 1994 album by Sergio Blass

* ''Sergio'' (2009 film), a documentary film

* ''Se ...

* 1976 - ''La linea del fiume

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figure ...

'', directed by Aldo Scavarda

Aldo Scavarda (born 22 August 1923 in Turin, Italy) is an Italian cinematographer who collaborated with Michelangelo Antonioni (''L'Avventura'', 1960), Bernardo Bertolucci ('' Prima della rivoluzione'', 1964), Mauro Bolognini ('' La giornata ball ...

* 1976 - '' Seven Beauties'' (''Pasqualino Settebellezze''), directed by Lina Wertmüller

* 1985 - '' The Assisi Underground'', directed by Alexander Ramati

* 1997 - '' Memoria'', directed by Ruggero Gabbai

Ruggero Gabbai (Wilrijk, 6 August 1964) is an Italian film director and photographer.

Biography

Ruggero Gabbai was born in Antwerp, Belgium in 1964 and grew up in Milan.

Keen on photography since he was very young, at the age of nineteen he o ...

* 1997 - ''The Truce

''The Truce'' ( it, La tregua), titled ''The Reawakening'' in the US, is a book by the Italian author Primo Levi. It is the sequel to '' If This Is a Man'' and describes the author's experiences from the liberation of Auschwitz ( Monowitz), whi ...

'' (''La tregua''), directed by Francesco Rosi

Francesco Rosi (; 15 November 1922 – 10 January 2015) was an Italian film director. His film ''The Mattei Affair'' won the Palme d'Or at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival. Rosi's films, especially those of the 1960s and 1970s, often appeared to ha ...

* 1997 - '' Life Is Beautiful'' (''La vita è bella''), directed by Roberto Benigni

* 2000 - '' Il cielo cade'', directed by Andrea Frazzi

Andrea is a given name which is common worldwide for both males and females, cognate to Andreas, Andrej and Andrew.

Origin of the name

The name derives from the Greek word ἀνήρ (''anēr''), genitive ἀνδρός (''andrós''), that ref ...

* 2001 - '' Unfair Competition'' (''Concorrenza sleale''), directed by Ettore Scola

Ettore Scola (; 10 May 1931 – 19 January 2016) was an Italian screenwriter and film director. He received a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film in 1978 for his film ''A Special Day'' and over the course of his film career was nominated for fiv ...

* 2001 - '' Senza confini - Storia del commissario Palatucci'', directed by Fabrizio Costa Fabrizio is an Italian first name, from the Latin word "Faber" meaning "smith" and may refer to:

* Fabrizio Barbazza (born 1963), Italian Formula One driver

* Fabrizio Barca (born 1954), Italian politician

* Fabrizio Brienza (born 1969), Italian mo ...

* 2001 - '' Perlasca - Un eroe italiano'', directed by Alberto Negrin

* 2003 - ''Facing Windows

''Facing Windows'' (Italian: ''La finestra di fronte'') is a 2003 Italian movie directed by Ferzan Özpetek.

Plot

Giovanna ( Giovanna Mezzogiorno) and her husband Filippo (Filippo Nigro) have settled into life. They both have jobs that make them ...

'' (''La finestra di fronte''), directed by Ferzan Özpetek

Ferzan Özpetek (born 3 February 1959) is a Turkish-Italian film director and screenwriter, residing in Italy.

Biography

Ferzan Özpetek was born in Istanbul in 1959. In 1976, he decided to move to Italy to study Cinema History at Sapienza Unive ...

* 2006 - '' Volevo solo vivere'', directed by Mimmo Calopresti Hotel Meina

A hotel is an establishment that provides paid lodging on a short-term basis. Facilities provided inside a hotel room may range from a modest-quality mattress in a small room to large suites with bigger, higher-quality beds, a dresser, a re ...

'', directed by Carlo Lizzani

* 2013 - '' Il viaggio più lungo, gli ebrei di Rodi'', directed by Ruggero Gabbai

Ruggero Gabbai (Wilrijk, 6 August 1964) is an Italian film director and photographer.

Biography

Ruggero Gabbai was born in Antwerp, Belgium in 1964 and grew up in Milan.

Keen on photography since he was very young, at the age of nineteen he o ...

* 2014 - '' My Italian Secret: The Forgotten Heroes'', directed by Oren Jacoby

See also

*Japan and the Holocaust

Although Japan was a member of the Axis powers, Axis, and therefore an ally of Nazi Germany, it did not actively participate in the Holocaust. Anti-semitic attitudes were not significant in Japan during World War II and there was little interest in ...

(The Holocaust and the other Axis power)

References

Bibliography

* Bettina, Elizabeth, ''It Happened in Italy: Untold Stories of How the People of Italy Defied the Horrors of the Holocaust'' (Thomas Nelson Inc, 2011) * Caracciolo, Nicola. ''Uncertain Refuge: Italy and the Jews during the Holocaust'' (University of Illinois Press, 1995). * De Felice, Renzo. ''The Jews in Fascist Italy: A History'' (Enigma Books, 2001) * * Klein, Shira. ''Italy's Jews from Emancipation to Fascism'' (Cambridge University Press, 2018). * Livingston, Michael A. ''The Fascists and the Jews of Italy: Mussolini's Race Laws, 1938–1943'' (Cambridge University Press, 2013). * * * Michaelis, Meir. ''Mussolini and the Jews: German-Italian Relations and the Jewish Question, 1922–1945'' (Oxford University Press, 1979) * O'Reilly, Charles T. ''Jews of Italy, 1938–1945: An Analysis of Revisionist Histories'' (McFarland & Company, 2007) * Perra, Emiliano. ''Conflicts of Memory: The Reception of Holocaust Films and TV Programmes in Italy, 1945 to the Present'' (Peter Lang AG, 2010) * Sarfatti, Michele. ''The Jews in Mussolini's Italy: From Equality to Persecution'' (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 2006) (Series in Modern European Cultural and Intellectual History). * Sullam, Simon Levis, ''The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy'' (Princeton University Press, 2018). * Zimmerman, Joshua D. (ed.), ''The Jews of Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922–1945'' (Cambridge, CUP, 2005). * Zuccotti, Susan. ''The Italians and the Holocaust: Persecution, Rescue and Survival'' (1987; repr. University of Nebraska Press, 1996). * Zuccotti, Susan. '' Under His Very Windows: The Vatican and the Holocaust in Italy'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).External links

Database of the Italian Shoah victims

{{Europe in topic, The Holocaust in

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...