The Hague Peace Conferences 1899 And 1907 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international

The First Hague Conference came from a proposal on 24 August 1898 by

The First Hague Conference came from a proposal on 24 August 1898 by

(I)

Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes This convention included the creation of the

(II)

Convention with respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land This voluminous convention contains the laws to be used in all wars on land between signatories. It specifies the treatment of prisoners of war, includes the provisions of the Geneva Convention of 1864 for the treatment of the wounded, and forbids the use of poisons, the killing of enemy

(III)

Convention for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention of 22 August 1864 This convention provides for the protection of marked

(IV,1)

Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons or by Other New Analogous Methods This declaration provides that, for a period of five years, in any war between signatory powers, no projectiles or explosives would be launched from balloons, "or by other new methods of a similar nature". The declaration was ratified by all the major powers mentioned above, except the United Kingdom and the United States. *'

(IV,2)

Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Use of Projectiles with the Sole Object to Spread Asphyxiating Poisonous Gases This declaration states that, in any war between signatory powers, the parties will abstain from using projectiles "the sole object of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases". Ratified by all major powers, except the United States. *'

(IV,3)

Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Use of Bullets which can Easily Expand or Change their Form inside the Human Body such as Bullets with a Hard Covering which does not Completely Cover the Core, or containing Indentations This declaration states that, in any war between signatory powers, the parties will abstain from using " bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human body". This directly banned

The Second Hague Conference, in 1907, resulted in conventions containing only few major advancements from the 1899 Convention. However, the meeting of major powers did prefigure later 20th-century attempts at international cooperation.

The second conference was called at the suggestion of U.S. President

The Second Hague Conference, in 1907, resulted in conventions containing only few major advancements from the 1899 Convention. However, the meeting of major powers did prefigure later 20th-century attempts at international cooperation.

The second conference was called at the suggestion of U.S. President

(I)

Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes

This convention confirms and expands on Convention (I) of 1899. As of February 2017, this convention is in force for 102 states,

and 116 states have ratified one or both of the 1907 Convention (I) and the 1899 Convention (I), which together are the founding documents of the

(II)

Convention respecting the Limitation of the Employment of Force for Recovery of Contract Debts * '

(III)

Convention relative to the Opening of Hostilities

This convention sets out the accepted procedure for a state making a

(IV)

Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land

This convention confirms, with minor modifications, the provisions of Convention (II) of 1899. All major powers ratified it. * '

(V)

Convention relative to the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in case of War on Land * '

(VI)

Convention relative to the Legal Position of Enemy Merchant Ships at the Start of Hostilities * '

(VII)

Convention relative to the Conversion of Merchant Ships into War-ships * '

(VIII)

Convention relative to the Laying of Automatic Submarine Contact Mines * '

(IX)

Convention concerning Bombardment by Naval Forces in Time of War * '

(X)

Convention for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention (of 6 July 1906)

This convention updated Convention (III) of 1899 to reflect the amendments that had been made to the 1864 Geneva Convention. Convention (X) was ratified by all major states except Britain. It was subsequently superseded by

(XI)

Convention relative to Certain Restrictions with regard to the Exercise of the Right of Capture in Naval War * '

(XII)

Convention relative to the Establishment of an International Prize Court

This convention would have established the

(XIII)

Convention concerning the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Naval War * '

(XIV)

Declaration Prohibiting the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons

This declaration extended the provisions of Declaration (IV,1) of 1899 to the close of the planned Third Peace Conference (which never took place). Among the major powers, this was ratified only by China, Britain, and the United States.

available from the

Avalon Project at Yale Law School on The Laws of War

��Contains the full texts of both the 1899 and 1907 conventions, among other treaties.

ICRC International Humanitarian Law – Treaties & Documents

contains full texts and ratifying states of both the 1899 and 1907 conventions, among other treaties.

List of signatory powers of the Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes

The Hague conventions and declarations of 1899 and 1907

by James Brown Scott (ed.) Contains the texts of all conventions and the ratifying countries as of 1915. * * Lee, Jin Hyuck

* * * * Robinson, James J. (September 1960)

"Surprise Attack: Crime at Pearl Harbor and Now"

''ABA Journal'' 46(9). American Bar Association. p. 978.

online

* Barcroft, Stephen. "The Hague Peace Conference of 1899". ''Irish Studies in International Affairs'' 1989, Vol. 3 Issue 1, pp 55–68

online

* Best, Geoffrey. "Peace conferences and the century of total war: the 1899 Hague Conference and what came after." ''International Affairs'' 75.3 (1999): 619–634

online

* Bettez, David J. "Unfulfilled Initiative: Disarmament Negotiations and the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907". ''RUSI Journal: Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies,'' June 1988, Vol. 133 Issue 3, pp 57–62. * Eyffinger, Arthur. "A highly critical moment: role and record of the 1907 Hague Peace Conference." ''Netherlands international law review'' 54.2 (2007): 197–228. * Hucker, Daniel. "British Peace Activism and 'New’Diplomacy: Revisiting the 1899 Hague Peace Conference." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 26.3 (2015): 405–423

online

* Reinsch, P. (1908). "Failures and Successes at the Second Hague Conference." ''American Political Science Review,'' ''2''(2), 204–220. *Scott, James Brown, ed. ''The Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907, Vol. 1, The Conferences''. (The Johns Hopkins Press 1909)

online

* *

Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (official depositary)

Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (official depositary) {{DEFAULTSORT:Hague Conventions of 1899 And 1907 1899 in military history 1907 in military history 1899 in the Netherlands 1907 in the Netherlands 1908 conferences 1907 conferences 19th century in The Hague 20th century in The Hague Diplomatic conferences in the Netherlands International humanitarian law treaties Pacifism in Germany Peace conferences Treaties establishing intergovernmental organizations Treaties concluded in 1899 Treaties concluded in 1907 Treaties entered into force in 1900 Treaties entered into force in 1910 Treaties of Albania Treaties of Argentina Treaties of Australia Treaties of Austria-Hungary Treaties of the Bahamas Treaties of Bahrain Treaties of Bangladesh Treaties of Belize Treaties of Benin Treaties of Burkina Faso Treaties of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic Treaties of Belgium Treaties of Bolivia Treaties of the First Brazilian Republic Treaties of the Principality of Bulgaria Treaties of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1953–1970) Treaties of Cameroon Treaties of Canada Treaties of Chile Treaties of the Qing dynasty Treaties of the Republic of China (1912–1949) Treaties of Colombia Treaties of Costa Rica Treaties of Croatia Treaties of Cuba Treaties of Cyprus Treaties of Czechoslovakia Treaties of the Czech Republic Treaties of the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville) Treaties of Denmark Treaties of Djibouti Treaties of the Dominican Republic Treaties of Ecuador Treaties of Egypt Treaties of El Salvador Treaties of Eritrea Treaties of Estonia Treaties of Ethiopia Treaties of the Ethiopian Empire Treaties of Fiji Treaties of Finland Treaties of the French Third Republic Treaties of Georgia (country) Treaties of the German Empire Treaties of the Kingdom of Greece Treaties of Guatemala Treaties of Guyana Treaties of Haiti Treaties of the Qajar dynasty Treaties of Honduras Treaties of Iceland Treaties of India Treaties of Ba'athist Iraq Treaties of Ireland Treaties of Israel Treaties of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) Treaties of the Empire of Japan Treaties of Jordan Treaties of Kenya Treaties of the Korean Empire Treaties of South Korea Treaties of Kuwait Treaties of Kosovo Treaties of Kyrgyzstan Treaties of the Kingdom of Laos Treaties of Latvia Treaties of Lebanon Treaties of Liberia Treaties of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Treaties of Liechtenstein Treaties of Lithuania Treaties of Luxembourg Treaties of North Macedonia Treaties of Madagascar Treaties of Malaysia Treaties of Malta Treaties of Mauritius Treaties of Mexico Treaties of the Principality of Montenegro Treaties of Morocco Treaties of the Netherlands Treaties of New Zealand Treaties of Nicaragua Treaties of Nigeria Treaties of Norway Treaties of the Ottoman Empire Treaties of the Dominion of Pakistan Treaties of the State of Palestine Treaties of Panama Treaties of Paraguay Treaties of Peru Treaties of the Philippines Treaties of the Second Polish Republic Treaties of the Kingdom of Portugal Treaties of the Portuguese First Republic Treaties of Qatar Treaties of the Kingdom of Romania Treaties of the Russian Empire Treaties of Rwanda Treaties of Saudi Arabia Treaties of São Tomé and Príncipe Treaties of Senegal Treaties of the Kingdom of Serbia Treaties of Serbia and Montenegro Treaties of Singapore Treaties of Slovakia Treaties of Slovenia Treaties of South Africa Treaties of Spain under the Restoration Treaties of the Dominion of Ceylon Treaties of the Republic of the Sudan (1956–1969) Treaties of Suriname Treaties of Eswatini Treaties of Sweden Treaties of Switzerland Treaties of Thailand Treaties of Togo Treaties of Uganda Treaties of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Treaties of the United Arab Emirates Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922) Treaties of the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway Treaties of the United States Treaties of Uruguay Treaties of Venezuela Treaties of Vietnam Treaties of Zambia Treaties of Zimbabwe

treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

and declarations negotiated at two international peace conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of certain states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities and sign a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in the past include the follo ...

s at The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. Along with the Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

, the Hague Conventions were among the first formal statements of the laws of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territor ...

and war crimes in the body of secular international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

. A third conference was planned for 1914 and later rescheduled for 1915, but it did not take place because of the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

History

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 were the firstmultilateral treaties

A multilateral treaty is a treaty to which two or more sovereign states are parties. Each party owes the same obligations to all other parties, except to the extent that they have stated reservations. Examples of multilateral treaties include the ...

that addressed the conduct of warfare and were largely based on the Lieber Code

The Lieber Code of April 24, 1863, issued as General Orders No. 100, Adjutant General's Office, 1863, was an instruction signed by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln to the Union forces of the United States during the American Civil War that dictated h ...

, which was signed and issued by US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

to the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

Forces of the United States on 24 April 1863, during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. The Lieber Code was the first official comprehensive codified law that set out regulations for behavior in times of martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

; protection of civilian

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not "combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant, b ...

s and civilian property and punishment of transgression; deserters

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ar ...

, prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

, hostage

A hostage is a person seized by an abductor in order to compel another party, one which places a high value on the liberty, well-being and safety of the person seized, such as a relative, employer, law enforcement or government to act, or ref ...

s, and pillaging

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

; partisan

Partisan may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (weapon), a pole weapon

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

Films

* ''Partisan'' (film), a 2015 Australian film

* ''Hell River'', a 1974 Yugoslavian film also know ...

s; spies

Spies most commonly refers to people who engage in spying, espionage or clandestine operations.

Spies or The Spies may also refer to:

* Spies (surname), a German surname

* Spies (band), a jazz fusion band

* Spies (song), "Spies" (song), a song by ...

; truce

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state act ...

s and prisoner exchange

A prisoner exchange or prisoner swap is a deal between opposing sides in a conflict to release prisoners: prisoners of war, spies, hostages, etc. Sometimes, dead bodies are involved in an exchange.

Geneva Conventions

Under the Geneva Convent ...

; parole of former rebel

A rebel is a participant in a rebellion.

Rebel or rebels may also refer to:

People

* Rebel (given name)

* Rebel (surname)

* Patriot (American Revolution), during the American Revolution

* American Southerners, as a form of self-identification; s ...

troops; the conditions of any armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

, and respect for human life; assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

and murder of soldiers or citizens in hostile territory; and the status of individuals engaged in a state of civil war against the government.

As such, the code was widely regarded as the best summary of the first customary

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a r ...

laws and customs of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territor ...

in the 19th century and was welcomed and adopted by military establishments of other nations. The 1874 Brussels Declaration, which was never adopted by all major nations, listed 56 articles that drew inspiration from the Lieber Code. Much of the regulations in the Hague Conventions were borrowed heavily from the Lieber Code.

Subject matter

Both conferences included negotiations concerningdisarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, such as n ...

, the laws of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territor ...

and war crimes. A major effort in both conferences was the creation of a binding international court for compulsory arbitration to settle international disputes, which was considered necessary to replace the institution of war. This effort, however, failed at both conferences; instead, a voluntary forum for arbitration, the Permanent Court of Arbitration

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) is a non-UN intergovernmental organization located in The Hague, Netherlands. Unlike a judicial court in the traditional sense, the PCA provides services of arbitral tribunal to resolve disputes that arise ...

, was established. Most of the countries present, including the United States, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, favoured a process for binding international arbitration, but the provision was vetoed by a few countries, led by Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

.

Hague Convention of 1899

The First Hague Conference came from a proposal on 24 August 1898 by

The First Hague Conference came from a proposal on 24 August 1898 by Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

. Nicholas and Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

Mikhail Nikolayevich Muravyov

Count Mikhail Nikolayevich Muravyov (russian: Граф Михаи́л Никола́евич Муравьёв) (, Saint Petersburg – ) was a Russian politician, statesman who advocated transferring the attention of Russian foreign policy fr ...

, his foreign minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

, were instrumental in initiating the conference. The conference opened on 18 May 1899, the Tsar's birthday. The treaties, declarations, and final act of the conference were signed on 29 July of that year, and they entered into force

In law, coming into force or entry into force (also called commencement) is the process by which legislation, regulations, treaties and other legal instruments come to have legal force and effect. The term is closely related to the date of this t ...

on 4 September 1900. What is referred to as the Hague Convention of 1899 consisted of three main treaties and three additional declarations:

*'(I)

Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes This convention included the creation of the

Permanent Court of Arbitration

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) is a non-UN intergovernmental organization located in The Hague, Netherlands. Unlike a judicial court in the traditional sense, the PCA provides services of arbitral tribunal to resolve disputes that arise ...

, which exists to this day. The section was ratified by all major powers and many smaller powers26 signatories in all, including Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Belgium, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, China, Denmark, Germany, France, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Luxembourg, Mexico, Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, the Netherlands, the Ottoman Empire, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

, Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 mi ...

, Spain, Sweden and Norway, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, the United Kingdom and the United States.

*'(II)

Convention with respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land This voluminous convention contains the laws to be used in all wars on land between signatories. It specifies the treatment of prisoners of war, includes the provisions of the Geneva Convention of 1864 for the treatment of the wounded, and forbids the use of poisons, the killing of enemy

combatants

Combatant is the legal status of an individual who has the right to engage in hostilities during an armed conflict. The legal definition of "combatant" is found at article 43(2) of Additional Protocol I (AP1) to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. It ...

who have surrendered, looting

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

of a town or place, and the attack or bombardment

A bombardment is an attack by artillery fire or by dropping bombs from aircraft on fortifications, combatants, or towns and buildings.

Prior to World War I, the term was only applied to the bombardment of defenseless or undefended objects, ...

of undefended towns or habitations. Inhabitants of occupied territories

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

may not be forced into military service

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job (volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft (conscription).

Some nations (e.g., Mexico) require a ...

against their own country and collective punishment

Collective punishment is a punishment or sanction imposed on a group for acts allegedly perpetrated by a member of that group, which could be an ethnic or political group, or just the family, friends and neighbors of the perpetrator. Because ind ...

is forbidden. The section was signed by all major powers listed above except China.

*'(III)

Convention for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention of 22 August 1864 This convention provides for the protection of marked

hospital ships

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. I ...

and requires them to treat the wounded and shipwrecked sailors of all belligerent parties. It too was ratified by all major powers.

*'(IV,1)

Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons or by Other New Analogous Methods This declaration provides that, for a period of five years, in any war between signatory powers, no projectiles or explosives would be launched from balloons, "or by other new methods of a similar nature". The declaration was ratified by all the major powers mentioned above, except the United Kingdom and the United States. *'

(IV,2)

Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Use of Projectiles with the Sole Object to Spread Asphyxiating Poisonous Gases This declaration states that, in any war between signatory powers, the parties will abstain from using projectiles "the sole object of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases". Ratified by all major powers, except the United States. *'

(IV,3)

Declaration concerning the Prohibition of the Use of Bullets which can Easily Expand or Change their Form inside the Human Body such as Bullets with a Hard Covering which does not Completely Cover the Core, or containing Indentations This declaration states that, in any war between signatory powers, the parties will abstain from using " bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human body". This directly banned

soft-point bullet

A soft-point bullet (SP), also known as a soft-nosed bullet, is a jacketed expanding bullet with a soft metal core enclosed by a stronger metal jacket left open at the forward tip. A soft-point bullet is intended to expand upon striking flesh to ...

s (which had a partial metal jacket and an exposed tip) and "cross-tipped" bullets (which had a cross-shaped incision in their tip to aid in expansion, nicknamed "dum dums" from the Dum Dum Arsenal

The Dum Dum Arsenal was a British military facility located near the town of Dum Dum in modern West Bengal, India.

The arsenal was at the centre of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, caused in part by rumours that the paper cartridges for their muzzl ...

in India). It was ratified by all major powers, except the United States.

Hague Convention of 1907

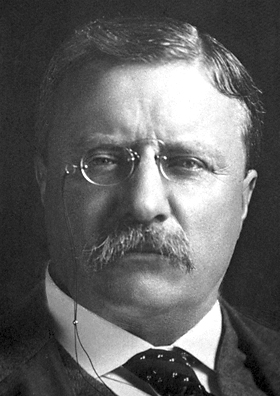

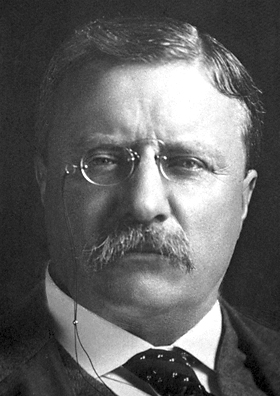

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

in 1904, but it was postponed because of the war between Russia and Japan. The Second Peace Conference was held from 15 June to 18 October 1907. The intent of the conference was to expand upon the 1899 Hague Convention by modifying some parts and adding new topics; in particular, the 1907 conference had an increased focus on naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

. The British attempted to secure the limitation of armaments, but these efforts were defeated by the other powers, led by Germany, which feared a British attempt to stop the growth of the German fleet. As Britain had the world's largest navy, limits on naval expansion would preserve that dominant position. Germany also rejected proposals for compulsory arbitration. However, the conference did enlarge the machinery for voluntary arbitration and established conventions regulating the collection of debts, rules of war, and the rights and obligations of neutrals.

The treaties, declarations, and final act of the Second Conference were signed on 18 October 1907; they entered into force on 26 January 1910. The 1907 Convention consists of thirteen treaties—of which twelve were ratified and entered into force—and one declaration:

* '(I)

Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes

This convention confirms and expands on Convention (I) of 1899. As of February 2017, this convention is in force for 102 states,

and 116 states have ratified one or both of the 1907 Convention (I) and the 1899 Convention (I), which together are the founding documents of the

Permanent Court of Arbitration

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) is a non-UN intergovernmental organization located in The Hague, Netherlands. Unlike a judicial court in the traditional sense, the PCA provides services of arbitral tribunal to resolve disputes that arise ...

.

* '(II)

Convention respecting the Limitation of the Employment of Force for Recovery of Contract Debts * '

(III)

Convention relative to the Opening of Hostilities

This convention sets out the accepted procedure for a state making a

declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state (polity), state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a nationa ...

.

* '(IV)

Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land

This convention confirms, with minor modifications, the provisions of Convention (II) of 1899. All major powers ratified it. * '

(V)

Convention relative to the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in case of War on Land * '

(VI)

Convention relative to the Legal Position of Enemy Merchant Ships at the Start of Hostilities * '

(VII)

Convention relative to the Conversion of Merchant Ships into War-ships * '

(VIII)

Convention relative to the Laying of Automatic Submarine Contact Mines * '

(IX)

Convention concerning Bombardment by Naval Forces in Time of War * '

(X)

Convention for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention (of 6 July 1906)

This convention updated Convention (III) of 1899 to reflect the amendments that had been made to the 1864 Geneva Convention. Convention (X) was ratified by all major states except Britain. It was subsequently superseded by

Second Geneva Convention

The Second Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. The Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condit ...

.

* '(XI)

Convention relative to Certain Restrictions with regard to the Exercise of the Right of Capture in Naval War * '

(XII)

Convention relative to the Establishment of an International Prize Court

This convention would have established the

International Prize Court The International Prize Court was an international court proposed at the beginning of the 20th century, to hear prize cases. An international agreement to create it, the ''Convention Relative to the Creation of an International Prize Court'', was ma ...

for the resolution of conflicting claims relating to captured ships during wartime. It is the one convention that never came into force. It was ratified only by Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

.

* '(XIII)

Convention concerning the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Naval War * '

(XIV)

Declaration Prohibiting the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons

This declaration extended the provisions of Declaration (IV,1) of 1899 to the close of the planned Third Peace Conference (which never took place). Among the major powers, this was ratified only by China, Britain, and the United States.

Participants

The Brazilian delegation was led byRuy Barbosa

Ruy Barbosa de Oliveira (5 November 1849 – 1 March 1923), also known as Rui Barbosa, was a Brazilian polymath, diplomat, writer, jurist, and politician. Born in Salvador, Bahia, and a distinguished and staunch defender of civil liberties and ...

, whose contributions are seen today by some analysts as essential for the defense of the principle of legal equality of nations. The British delegation included Sir Edward Fry

Sir Edward Fry, (4 November 1827 – 19 October 1918) was an English Lord Justice of Appeal (1883–1892) and an arbitrator on the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Biography

Joseph Fry (1795-1879) and Mary Ann Swaine were his parents. He was ...

, Sir Ernest Satow

Sir Ernest Mason Satow, (30 June 1843 – 26 August 1929), was a British scholar, diplomat and Japanologist.

Satow is better known in Japan than in Britain or the other countries in which he served, where he was known as . He was a key fig ...

, the 11th Lord Reay (Donald James Mackay) and Sir Henry Howard as delegates, and Eyre Crowe

Sir Eyre Alexander Barby Wichart Crowe (30 July 1864 – 28 April 1925) was a British diplomat, an expert on Germany in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. He is best known for his vehement warning, in 1907, that Germany's expansionism was mot ...

as a technical delegate. The Russian delegation was led by Friedrich Martens

Friedrich Fromhold Martens, or Friedrich Fromhold von Martens,, french: Frédéric Frommhold (de) Martens ( – ) was a diplomat and jurist in service of the Russian Empire who made important contributions to the science of international law. H ...

. The Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

an delegation was led by José Batlle y Ordóñez

José Pablo Torcuato Batlle y Ordóñez ( or ; 23 May 1856 in Montevideo, Uruguay – 20 October 1929), nicknamed ''Don Pepe'', was a prominent Uruguayan politician, who served two terms as President of Uruguay for the Colorado Party. He wa ...

, a defender of the idea of compulsory arbitration. With Louis Renault and Léon Bourgeois

Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois (; 21 May 185129 September 1925) was a French statesman. His ideas influenced the Radical Party regarding a wide range of issues. He promoted progressive taxation such as progressive income taxes and social insuran ...

, Paul Henri d'Estournelles de Constant was a member of the French delegation for both the 1899 and 1907 delegations. He later won the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

in 1909 for his efforts. The U.S. representative, with the rank of ambassador, was former American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

president U. M. Rose

Uriah Milton Rose (March 5, 1834 – August 12, 1913) was an American lawyer and Confederate sympathizer. "Approachable, affable, and kind," graceful and courteous, he was called "the most scholarly lawyer in America" and "one of the leading ...

. The representative of the Chinese Empire was Lu Zhengxiang, who would become Prime Minister of the Republic of China in 1912.

Though not negotiated in The Hague, the Geneva Protocol

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, usually called the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in ...

to the Hague Conventions is considered an addition to the Conventions. Signed on 17 June 1925 and entering into force on 8 February 1928, its single article permanently bans the use of all forms of chemical

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., wi ...

and biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Bio ...

. The protocol grew out of the increasing public outcry against chemical warfare following the use of mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, b ...

and similar agents in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and fears that chemical and biological warfare could lead to horrific consequences in any future war. The protocol has since been augmented by the Biological Weapons Convention

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), or Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), is a disarmament treaty that effectively bans biological and toxin weapons by prohibiting their development, production, acquisition, transfer, stockpil ...

(1972) and the Chemical Weapons Convention

The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), officially the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction, is an arms control treaty administered by the Organisation for ...

(1993).

Legacy

Many of the rules laid down at the Hague Conventions were violated in World War I. The German invasion of Belgium, for instance, was a violation of Convention (III) of 1907, which states that hostilities must not commence without explicit warning.Poison gas

Many gases have toxic properties, which are often assessed using the LC50 (median lethal dose) measure. In the United States, many of these gases have been assigned an NFPA 704 health rating of 4 (may be fatal) or 3 (may cause serious or perman ...

was introduced and used by all major belligerents throughout the war, in violation of the Declaration (IV, 2) of 1899 and Convention (IV) of 1907, which explicitly forbade the use of "poison or poisoned weapons".

Writing in 1918, the German international law scholar and neo-Kantian

In late modern continental philosophy, neo-Kantianism (german: Neukantianismus) was a revival of the 18th-century philosophy of Immanuel Kant. The Neo-Kantians sought to develop and clarify Kant's theories, particularly his concept of the "thin ...

pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

Walther Schücking

Walther Adrian Schücking (6 January 1875, Münster, Westphalia – 25 August 1935) was a German liberal politician, professor of public international law and the first German judge at the Permanent Court of International Justice in The Hague.

...

called the assemblies the "international union of Hague conferences". Schücking saw the Hague conferences as a nucleus of a future international federation that was to meet at regular intervals to administer justice and develop international law procedures for the peaceful settlement of disputes, asserting that "a definite political union of the states of the world has been created with the First and Second Conferences".Walther Schücking, ''The international union of the Hague conferences'', Clarendon Press, 1918.

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the judges of the military tribunal of the Trial of German Major War Criminals at Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

found that by 1939, the rules laid down in the 1907 Hague Convention were recognised by all civilised nations and were regarded as declaratory of the laws and customs of war. Under this post-war decision, a country did not have to have ratified the 1907 Hague Convention in order to be bound by them.Judgement: The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanityavailable from the

Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the be ...

at the Yale Law School

Yale Law School (Yale Law or YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824 and has been ranked as the best law school in the United States by ''U ...

, Retrieved on 29 August 2014.

Although their contents have largely been superseded by other treaties, the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 continue to stand as symbols of the need for restrictions on war and the desirability of avoiding it altogether. Since 2000, Convention (I) of 1907 on the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes has been ratified by 20 additional states.

See also

*List of parties to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907

The following tables indicate the states that are party to the various Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. If a state has ratified, acceded, or succeeded to one of the treaties, the year of the original ratification is indicated. An "S" indicates ...

*American Peace Society

The American Peace Society is a pacifist group founded upon the initiative of William Ladd, in New York City, May 8, 1828. It was formed by the merging of many state and local societies, from New York, Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, of ...

*Antimilitarism

Antimilitarism (also spelt anti-militarism) is a doctrine that opposes war, relying heavily on a critical theory of imperialism and was an explicit goal of the First and Second International. Whereas pacifism is the doctrine that disputes (especia ...

*Command responsibility

Command responsibility (superior responsibility, the Yamashita standard, and the Medina standard) is the legal doctrine of hierarchical accountability for war crimes.

*Hague Secret Emissary Affair

The Hague Secret Emissary Affair (''Heigeu teuksa sageon'', 헤이그 특사사건) resulted from Emperor Gojong of the Korean Empire sending confidential emissaries to the Second Peace Conference at The Hague, the Netherlands, in 1907.

Backgro ...

*Martens Clause

The Martens Clause ( pronounced ) was introduced into the preamble to the 1899 Hague Convention II – Laws and Customs of War on Land.

__NOTOC__

The clause took its name from a declaration read by Friedrich Martens, the delegate of Russia at ...

*Militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

*Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project

The Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project (RULAC Project) is an initiative of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights to support the application and implementation of the international law of armed conflict.

Overview ...

*Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868

The Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868 or in full Declaration Renouncing the Use, in Time of War, of Explosive Projectiles Under 400 Grammes Weight is an international treaty agreed in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, November 29 / December 11, ...

(Declaration Renouncing the Use, in Time of War, of Explosive Projectiles Under 400 Grammes Weight)

*World Federation

World government is the concept of a single political authority with jurisdiction over all humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

A world gove ...

References

Citations

Sources

Avalon Project at Yale Law School on The Laws of War

��Contains the full texts of both the 1899 and 1907 conventions, among other treaties.

ICRC International Humanitarian Law – Treaties & Documents

contains full texts and ratifying states of both the 1899 and 1907 conventions, among other treaties.

List of signatory powers of the Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes

The Hague conventions and declarations of 1899 and 1907

by James Brown Scott (ed.) Contains the texts of all conventions and the ratifying countries as of 1915. * * Lee, Jin Hyuck

* * * * Robinson, James J. (September 1960)

"Surprise Attack: Crime at Pearl Harbor and Now"

''ABA Journal'' 46(9). American Bar Association. p. 978.

Further reading

* Baker, Betsy. "Hague Peace Conferences (1899 and 1907)." ''The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law,'' 4.2 (2009): 689–698online

* Barcroft, Stephen. "The Hague Peace Conference of 1899". ''Irish Studies in International Affairs'' 1989, Vol. 3 Issue 1, pp 55–68

online

* Best, Geoffrey. "Peace conferences and the century of total war: the 1899 Hague Conference and what came after." ''International Affairs'' 75.3 (1999): 619–634

online

* Bettez, David J. "Unfulfilled Initiative: Disarmament Negotiations and the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907". ''RUSI Journal: Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies,'' June 1988, Vol. 133 Issue 3, pp 57–62. * Eyffinger, Arthur. "A highly critical moment: role and record of the 1907 Hague Peace Conference." ''Netherlands international law review'' 54.2 (2007): 197–228. * Hucker, Daniel. "British Peace Activism and 'New’Diplomacy: Revisiting the 1899 Hague Peace Conference." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 26.3 (2015): 405–423

online

* Reinsch, P. (1908). "Failures and Successes at the Second Hague Conference." ''American Political Science Review,'' ''2''(2), 204–220. *Scott, James Brown, ed. ''The Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907, Vol. 1, The Conferences''. (The Johns Hopkins Press 1909)

online

* *

External links

Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (official depositary)

Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (official depositary) {{DEFAULTSORT:Hague Conventions of 1899 And 1907 1899 in military history 1907 in military history 1899 in the Netherlands 1907 in the Netherlands 1908 conferences 1907 conferences 19th century in The Hague 20th century in The Hague Diplomatic conferences in the Netherlands International humanitarian law treaties Pacifism in Germany Peace conferences Treaties establishing intergovernmental organizations Treaties concluded in 1899 Treaties concluded in 1907 Treaties entered into force in 1900 Treaties entered into force in 1910 Treaties of Albania Treaties of Argentina Treaties of Australia Treaties of Austria-Hungary Treaties of the Bahamas Treaties of Bahrain Treaties of Bangladesh Treaties of Belize Treaties of Benin Treaties of Burkina Faso Treaties of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic Treaties of Belgium Treaties of Bolivia Treaties of the First Brazilian Republic Treaties of the Principality of Bulgaria Treaties of the Kingdom of Cambodia (1953–1970) Treaties of Cameroon Treaties of Canada Treaties of Chile Treaties of the Qing dynasty Treaties of the Republic of China (1912–1949) Treaties of Colombia Treaties of Costa Rica Treaties of Croatia Treaties of Cuba Treaties of Cyprus Treaties of Czechoslovakia Treaties of the Czech Republic Treaties of the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville) Treaties of Denmark Treaties of Djibouti Treaties of the Dominican Republic Treaties of Ecuador Treaties of Egypt Treaties of El Salvador Treaties of Eritrea Treaties of Estonia Treaties of Ethiopia Treaties of the Ethiopian Empire Treaties of Fiji Treaties of Finland Treaties of the French Third Republic Treaties of Georgia (country) Treaties of the German Empire Treaties of the Kingdom of Greece Treaties of Guatemala Treaties of Guyana Treaties of Haiti Treaties of the Qajar dynasty Treaties of Honduras Treaties of Iceland Treaties of India Treaties of Ba'athist Iraq Treaties of Ireland Treaties of Israel Treaties of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946) Treaties of the Empire of Japan Treaties of Jordan Treaties of Kenya Treaties of the Korean Empire Treaties of South Korea Treaties of Kuwait Treaties of Kosovo Treaties of Kyrgyzstan Treaties of the Kingdom of Laos Treaties of Latvia Treaties of Lebanon Treaties of Liberia Treaties of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Treaties of Liechtenstein Treaties of Lithuania Treaties of Luxembourg Treaties of North Macedonia Treaties of Madagascar Treaties of Malaysia Treaties of Malta Treaties of Mauritius Treaties of Mexico Treaties of the Principality of Montenegro Treaties of Morocco Treaties of the Netherlands Treaties of New Zealand Treaties of Nicaragua Treaties of Nigeria Treaties of Norway Treaties of the Ottoman Empire Treaties of the Dominion of Pakistan Treaties of the State of Palestine Treaties of Panama Treaties of Paraguay Treaties of Peru Treaties of the Philippines Treaties of the Second Polish Republic Treaties of the Kingdom of Portugal Treaties of the Portuguese First Republic Treaties of Qatar Treaties of the Kingdom of Romania Treaties of the Russian Empire Treaties of Rwanda Treaties of Saudi Arabia Treaties of São Tomé and Príncipe Treaties of Senegal Treaties of the Kingdom of Serbia Treaties of Serbia and Montenegro Treaties of Singapore Treaties of Slovakia Treaties of Slovenia Treaties of South Africa Treaties of Spain under the Restoration Treaties of the Dominion of Ceylon Treaties of the Republic of the Sudan (1956–1969) Treaties of Suriname Treaties of Eswatini Treaties of Sweden Treaties of Switzerland Treaties of Thailand Treaties of Togo Treaties of Uganda Treaties of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Treaties of the United Arab Emirates Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922) Treaties of the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway Treaties of the United States Treaties of Uruguay Treaties of Venezuela Treaties of Vietnam Treaties of Zambia Treaties of Zimbabwe