The Duke Of Wellington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an

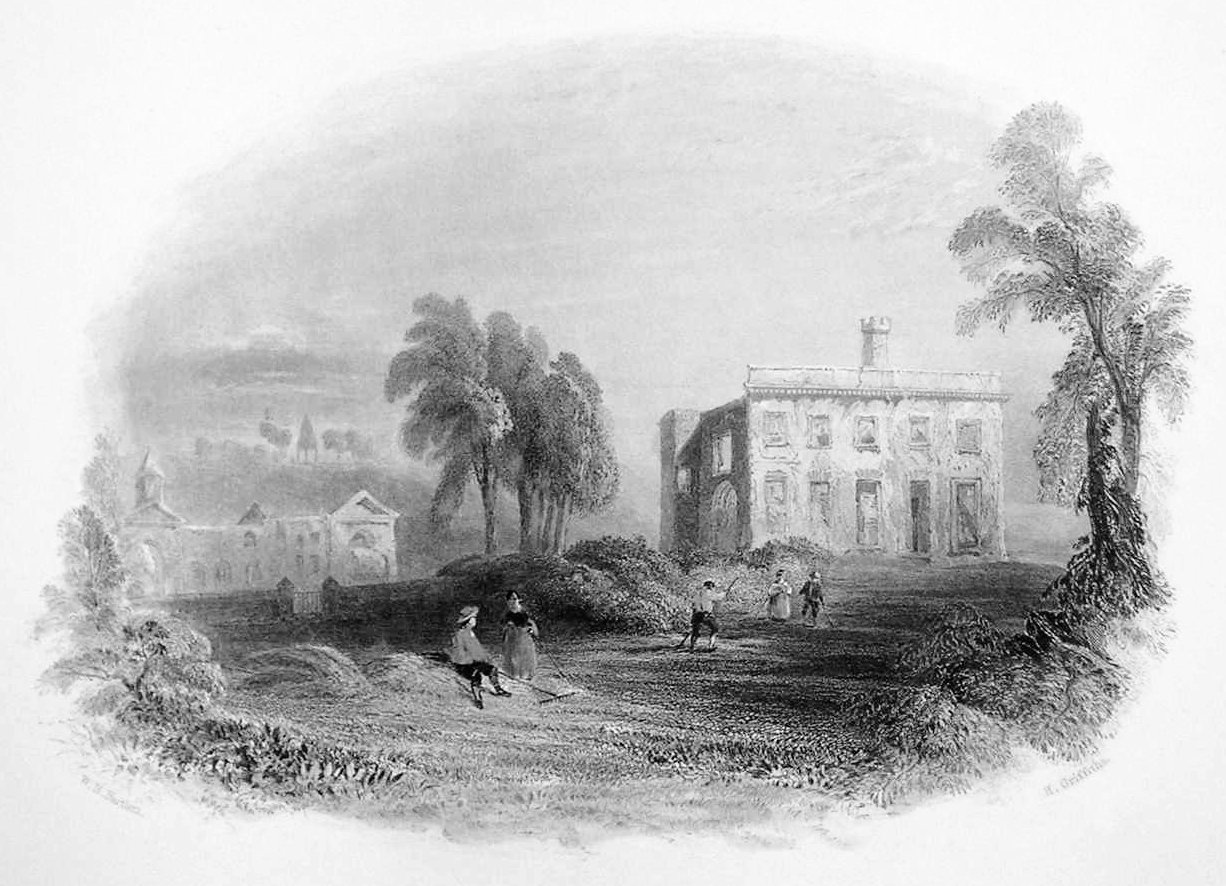

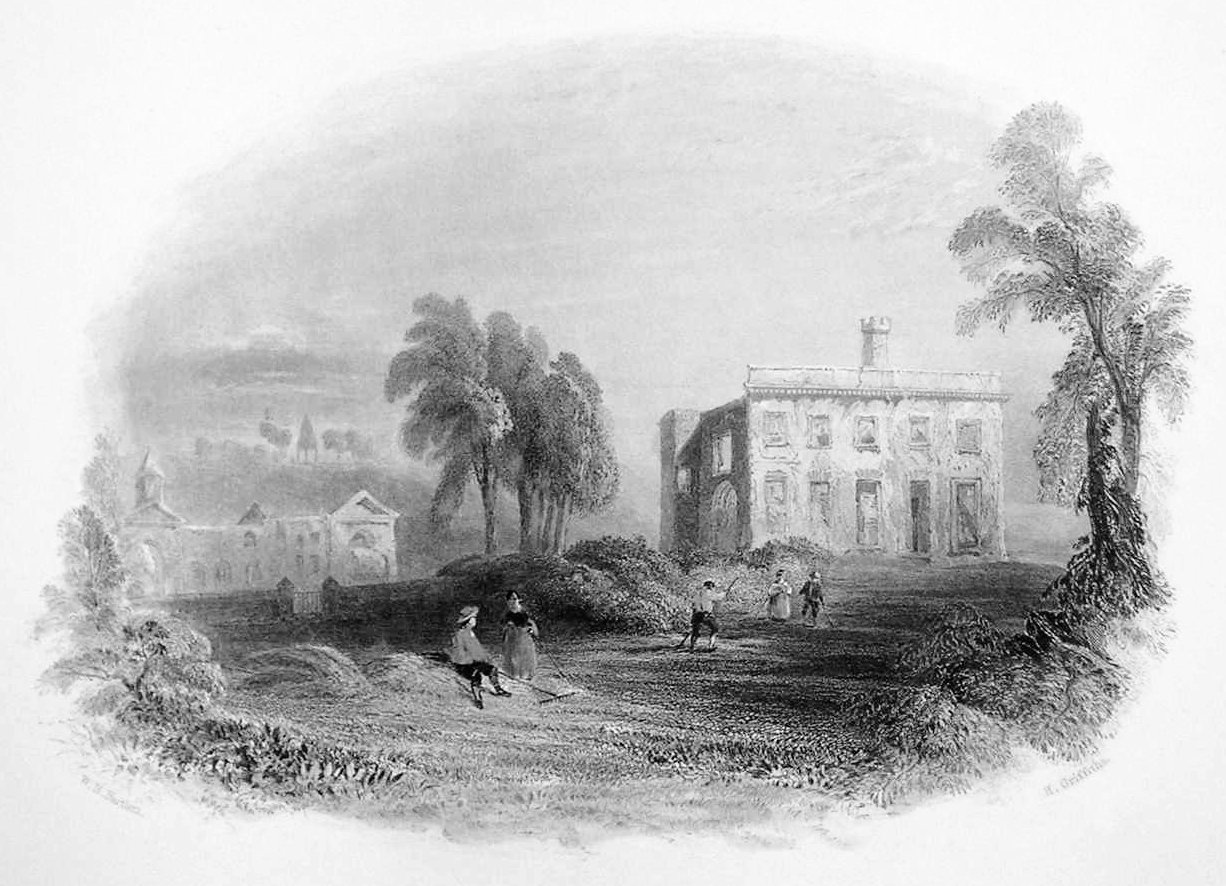

Wellesley spent most of his childhood at his family's two homes, the first a large house in Dublin and the second

Wellesley spent most of his childhood at his family's two homes, the first a large house in Dublin and the second

Despite his new promise, Wellesley had yet to find a job and his family was still short of money, so upon the advice of his mother, his brother Richard asked his friend the

Despite his new promise, Wellesley had yet to find a job and his family was still short of money, so upon the advice of his mother, his brother Richard asked his friend the

In 1793, the Duke of York was sent to

In 1793, the Duke of York was sent to

As part of the campaign to extend the rule of the

As part of the campaign to extend the rule of the

Splitting his army into two forces, to pursue and locate the main Marathas army, (the second force, commanded by Colonel Stevenson was far smaller) Wellesley was preparing to rejoin his forces on 24 September. His intelligence, however, reported the location of the Marathas' main army, between two rivers near

Splitting his army into two forces, to pursue and locate the main Marathas army, (the second force, commanded by Colonel Stevenson was far smaller) Wellesley was preparing to rejoin his forces on 24 September. His intelligence, however, reported the location of the Marathas' main army, between two rivers near

Wellesley defeated the French at the

Wellesley defeated the French at the

In 1812, Wellington finally captured

In 1812, Wellington finally captured

His popularity in Britain was due to his image and his appearance as well as to his military triumphs. His victory fitted well with the passion and intensity of the Romantic movement, with its emphasis on individuality. His personal style influenced the fashions in Britain at the time: his tall, lean figure and his plumed black hat and grand yet classic uniform and white trousers became very popular.

In late 1814, the Prime Minister wanted him to take command in Canada with the assignment of winning the

His popularity in Britain was due to his image and his appearance as well as to his military triumphs. His victory fitted well with the passion and intensity of the Romantic movement, with its emphasis on individuality. His personal style influenced the fashions in Britain at the time: his tall, lean figure and his plumed black hat and grand yet classic uniform and white trousers became very popular.

In late 1814, the Prime Minister wanted him to take command in Canada with the assignment of winning the

On 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from

On 26 February 1815, Napoleon escaped from

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). It commenced with a diversionary attack on

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). It commenced with a diversionary attack on  Meanwhile, at approximately the same time as Ney's combined-arms assault on the centre-right of Wellington's line, Napoleon ordered Ney to capture La Haye Sainte at whatever the cost. Ney accomplished this with what was left of D'Erlon's corps soon after 18:00. Ney then moved

Meanwhile, at approximately the same time as Ney's combined-arms assault on the centre-right of Wellington's line, Napoleon ordered Ney to capture La Haye Sainte at whatever the cost. Ney accomplished this with what was left of D'Erlon's corps soon after 18:00. Ney then moved  Further to the west, 1,500 British Foot Guards under

Further to the west, 1,500 British Foot Guards under

The campaign led to numerous other controversies. Issues concerning Wellington's troop dispositions prior to Napoleon's invasion of the Netherlands, whether Wellington misled or betrayed Blücher by promising, then failing, to come directly to Blücher's aid at Ligny, and credit for the victory between Wellington and the Prussians. These and other such issues concerning Blücher's, Wellington's, and Napoleon's decisions during the campaign were the subject of a strategic-level study by the Prussian political-military theorist

The campaign led to numerous other controversies. Issues concerning Wellington's troop dispositions prior to Napoleon's invasion of the Netherlands, whether Wellington misled or betrayed Blücher by promising, then failing, to come directly to Blücher's aid at Ligny, and credit for the victory between Wellington and the Prussians. These and other such issues concerning Blücher's, Wellington's, and Napoleon's decisions during the campaign were the subject of a strategic-level study by the Prussian political-military theorist

Wellington entered politics again when he was appointed

Wellington entered politics again when he was appointed

The

The

Wellington was gradually superseded as leader of the Tories by Robert Peel, while the party evolved into the Conservatives. When the Tories were returned to power in 1834, Wellington declined to become prime minister because he thought membership in the House of Commons had become essential. The king reluctantly approved Peel, who was in Italy. Hence, Wellington acted as interim leader for three weeks in November and December 1834, taking the responsibilities of prime minister and most of the other ministries. In Peel's first cabinet (1834–1835), Wellington became

Wellington was gradually superseded as leader of the Tories by Robert Peel, while the party evolved into the Conservatives. When the Tories were returned to power in 1834, Wellington declined to become prime minister because he thought membership in the House of Commons had become essential. The king reluctantly approved Peel, who was in Italy. Hence, Wellington acted as interim leader for three weeks in November and December 1834, taking the responsibilities of prime minister and most of the other ministries. In Peel's first cabinet (1834–1835), Wellington became

Wellesley was married by his brother Gerald, a clergyman, to

Wellesley was married by his brother Gerald, a clergyman, to

Wellington died at

Wellington died at  Although in life he hated travelling by rail, having witnessed the death of

Although in life he hated travelling by rail, having witnessed the death of  Wellington's casket was decorated with banners which were made for his funeral procession. Originally, there was one from Prussia, which was removed during

Wellington's casket was decorated with banners which were made for his funeral procession. Originally, there was one from Prussia, which was removed during

Wellington always rose early; he "couldn't bear to lie awake in bed", even if the army was not on the march. Even when he returned to civilian life after 1815, he slept in a camp bed, reflecting his lack of regard for creature comforts. General

Wellington always rose early; he "couldn't bear to lie awake in bed", even if the army was not on the march. Even when he returned to civilian life after 1815, he slept in a camp bed, reflecting his lack of regard for creature comforts. General  Military historian Charles Dalton recorded that, after a hard-fought battle in Spain, a young officer made the comment, "I am going to dine with Wellington tonight", which was overheard by the Duke as he rode by. "Give me at least the prefix of Mr. before my name," Wellington said. "My Lord," replied the officer, "we do not speak of Mr. Caesar or Mr. Alexander, so why should I speak of Mr. Wellington?"

While known for his stern countenance and iron-handed discipline, Wellington was by no means unfeeling. While he is said to have disapproved of soldiers cheering as "too nearly an expression of opinion". Wellington nevertheless cared for his men: he refused to pursue the French after the battles of Porto and Salamanca, foreseeing an inevitable cost to his army in chasing a diminished enemy through rough terrain. The only time that he ever showed grief in public was after the storming of Badajoz: he cried at the sight of the British dead in the breaches.In this context, his famous despatch after the Battle of Vitoria, calling them the "scum of the earth" can be seen to be fuelled as much by disappointment at their breaking ranks as by anger. He shed tears after Waterloo on the presentation of the list of British fallen by Dr John Hume. Later with his family, unwilling to be congratulated for his victory, he broke down in tears, his fighting spirit diminished by the high cost of the battle and great personal loss.

Wellington's soldier servant, a gruff German called Beckerman, and his long-serving valet, James Kendall, who served him for 25 years and was with him when he died, were both devoted to him. (A story that he never spoke to his servants and preferred instead to write his orders on a notepad on his dressing table in fact probably refers to his son, the 2nd Duke. It was recorded by the 3rd Duke's niece, Viva Seton Montgomerie (1879–1959), as being an anecdote she heard from an old retainer, Charles Holman, who was said greatly to resemble Napoleon.)

Following an incident when, as Master-General of the Ordnance he had been close to a large explosion, Wellington began to experience deafness and other ear-related problems. In 1822, he had an operation to improve the hearing of the left ear. The result, however, was that he became permanently deaf on that side. It is claimed that he was "never quite well afterwards".

Perhaps because of his unhappy marriage, Wellington came to enjoy the company of a variety of intellectual and attractive women and had many amorous liaisons, particularly after the Battle of Waterloo and his subsequent ambassadorial position in Paris. In the days following Waterloo he had an affair with the notorious

Military historian Charles Dalton recorded that, after a hard-fought battle in Spain, a young officer made the comment, "I am going to dine with Wellington tonight", which was overheard by the Duke as he rode by. "Give me at least the prefix of Mr. before my name," Wellington said. "My Lord," replied the officer, "we do not speak of Mr. Caesar or Mr. Alexander, so why should I speak of Mr. Wellington?"

While known for his stern countenance and iron-handed discipline, Wellington was by no means unfeeling. While he is said to have disapproved of soldiers cheering as "too nearly an expression of opinion". Wellington nevertheless cared for his men: he refused to pursue the French after the battles of Porto and Salamanca, foreseeing an inevitable cost to his army in chasing a diminished enemy through rough terrain. The only time that he ever showed grief in public was after the storming of Badajoz: he cried at the sight of the British dead in the breaches.In this context, his famous despatch after the Battle of Vitoria, calling them the "scum of the earth" can be seen to be fuelled as much by disappointment at their breaking ranks as by anger. He shed tears after Waterloo on the presentation of the list of British fallen by Dr John Hume. Later with his family, unwilling to be congratulated for his victory, he broke down in tears, his fighting spirit diminished by the high cost of the battle and great personal loss.

Wellington's soldier servant, a gruff German called Beckerman, and his long-serving valet, James Kendall, who served him for 25 years and was with him when he died, were both devoted to him. (A story that he never spoke to his servants and preferred instead to write his orders on a notepad on his dressing table in fact probably refers to his son, the 2nd Duke. It was recorded by the 3rd Duke's niece, Viva Seton Montgomerie (1879–1959), as being an anecdote she heard from an old retainer, Charles Holman, who was said greatly to resemble Napoleon.)

Following an incident when, as Master-General of the Ordnance he had been close to a large explosion, Wellington began to experience deafness and other ear-related problems. In 1822, he had an operation to improve the hearing of the left ear. The result, however, was that he became permanently deaf on that side. It is claimed that he was "never quite well afterwards".

Perhaps because of his unhappy marriage, Wellington came to enjoy the company of a variety of intellectual and attractive women and had many amorous liaisons, particularly after the Battle of Waterloo and his subsequent ambassadorial position in Paris. In the days following Waterloo he had an affair with the notorious

Campaign of 1815

' an

written in response to Clausewitz, as well as supporting documents and essays by the editors. * * * * Goldsmith, Thomas. "The Duke of Wellington and British Foreign Policy 1814-1830." (PhD Diss. University of East Anglia, 2016)

online

* * * * Lambert, A. "Politics, administration and decision-making: Wellington and the navy, 1828–30" ''Wellington Studies'' IV, ed. C. M. Woolgar, (Southampton, 2008), pp. 185–243. * Longford, Elizabeth. ''Wellington: Pillar of State'' (1972), vol 2 of her biography

online

* * *

Records and images from the UK Parliament Collections

The life of Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington

Duke of Wellington's Regiment – West Riding

Papers of Arthur Wellesley, first Duke of Wellington (MS 61)

at the

More about Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington on the Downing Street website

* * *

"Napoleon and Wellington"

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Andrew Roberts, Mike Broer and Belinda Beaton (''In Our Time'', 25 October 2001) {{DEFAULTSORT:Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of 1769 births 1852 deaths 19th-century Anglo-Irish people 19th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom Wellesley Arthur Wellesley, Arthur Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to France British Army commanders of the Napoleonic Wars British Army personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars British Army personnel of the Peninsular War British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs British Secretaries of State British field marshals British military personnel of the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War British military personnel of the Second Anglo-Maratha War Burials at St Paul's Cathedral Chancellors of the University of Oxford Chief Secretaries for Ireland Commissioners of the Treasury for Ireland Constables of the Tower of London Cotiote War Diplomatic peers British duellists Duke of Wellington's Regiment officers Dukes da Vitória Dukes of Ciudad Rodrigo 101 Wellesley, Arthur 1 Fellows of the Royal Society Field marshals of Portugal Field marshals of Russia Grandees of Spain Grenadier Guards officers Irish Anglicans Wellesley, Arthur Irish expatriates in England Irish expatriates in France Irish expatriates in India Irish expatriates in Portugal Irish expatriates in Spain Irish expatriates in the Netherlands Irish officers in the British Army Leaders of the Conservative Party (UK) Lord High Constables of England Lord-Lieutenants of Hampshire Lord-Lieutenants of the Tower Hamlets Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports MPs for rotten boroughs Members of Trinity House Wellesley, Arthur Wellesley, Arthur Wellesley, Arthur Members of the Privy Council of Ireland Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Peers of the United Kingdom created by George III People associated with King's College London People educated at Eton College Wellesley, Arthur Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom Princes of Waterloo Regency era Royal Horse Guards officers Spanish captain generals Tory prime ministers of the United Kingdom Wellesley, Arthur Wellesley, Arthur UK MPs who were granted peerages

Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

soldier and Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

. He is among the commanders who won and ended the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

when the coalition defeated Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

at the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

in 1815.

Wellesley was born in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

into the Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. He was commissioned as an ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

in 1787, serving in Ireland as aide-de-camp to two successive lords lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kingdo ...

. He was also elected as a member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

in the Irish House of Commons

The Irish House of Commons was the lower house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from 1297 until 1800. The upper house was the House of Lords. The membership of the House of Commons was directly elected, but on a highly restrictive fra ...

. He was a colonel by 1796 and saw action in the Netherlands and in India, where he fought in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

The Fourth Anglo-Mysore War was a conflict in South India between the Kingdom of Mysore against the British East India Company and the Hyderabad Deccan in 1798–99.

This was the final conflict of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. The British captured ...

at the Battle of Seringapatam

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

. He was appointed governor of Seringapatam

Srirangapatna is a town and headquarters of one of the seven Taluks of Mandya district, in the Indian State of Karnataka. It gets its name from the Ranganthaswamy temple consecrated at around 984 CE. Later, under the British rule the city wa ...

and Mysore

Mysore (), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern part of the state of Karnataka, India. Mysore city is geographically located between 12° 18′ 26″ north latitude and 76° 38′ 59″ east longitude. It is located at an altitude of ...

in 1799 and, as a newly appointed major-general, won a decisive victory over the Maratha Confederacy

The Maratha Empire, also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy, was an early modern Indian confederation that came to dominate much of the Indian subcontinent in the 18th century. Maratha rule formally began in 1674 with the coronation of Shi ...

at the Battle of Assaye

The Battle of Assaye was a major battle of the Second Anglo-Maratha War fought between the Maratha Empire and the British East India Company. It occurred on 23 September 1803 near Assaye in western India. An outnumbered Indian and British forc ...

in 1803.

Wellesley rose to prominence as a general during the Peninsular campaign of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, and was promoted to the rank of field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

after leading the allied forces to victory against the French Empire

French Empire (french: Empire Français, link=no) may refer to:

* First French Empire, ruled by Napoleon I from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815 and by Napoleon II in 1815, the French state from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815

* Second French Empire, led by Nap ...

at the Battle of Vitoria

At the Battle of Vitoria (21 June 1813) a British, Portuguese and Spanish army under the Marquess of Wellington broke the French army under King Joseph Bonaparte and Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan near Vitoria in Spain, eventually leading to ...

in 1813. Following Napoleon's exile in 1814, he served as the ambassador to France and was granted a dukedom. During the Hundred Days

The Hundred Days (french: les Cent-Jours ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration ...

in 1815, he commanded the allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

army which, together with a Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

under Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher, defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. Wellington's battle record

A battle record, also often called a battle tool or battle breaks, is a vinyl record made up of brief samples from songs, film dialogue, sound effects, and drum loops for use by a DJ. The samples and drum loops are used for scratching and perf ...

is exemplary; he ultimately participated in some 60 battles during the course of his military career.

Wellington is famous for his adaptive defensive style of warfare, resulting in several victories against numerically superior forces while minimising his own losses. He is regarded as one of the greatest defensive commanders of all time, and many of his tactics and battle plans are still studied in military academies around the world. After the end of his active military career, he returned to politics. He was twice British prime minister as a member of the Tory party from 1828 to 1830 and for a little less than a month in 1834. He oversaw the passage of the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1829. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic emancipation throughout the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, but opposed the Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament, Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major chan ...

. He continued as one of the leading figures in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

until his retirement and remained Commander-in-Chief of the British Army until his death.

Early life

Family

Wellesley was born into an aristocraticAnglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

family, belonging to the Protestant Ascendancy, in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

as The Hon.

''The Honourable'' (British English) or ''The Honorable'' (American English; see spelling differences) (abbreviation: ''Hon.'', ''Hon'ble'', or variations) is an honorific style that is used as a prefix before the names or titles of certain ...

Arthur Wesley. Wellesley was born the son of Anne Wellesley, Countess of Mornington

Anne Wellesley, Countess of Mornington (''née'' Hill-Trevor; 23 June 1742 – 10 September 1831) was an Anglo-Irish aristocrat. She was the wife of Garret Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington and mother of the victor of the Battle of Waterloo, Arthur ...

and Garret Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington

Garret Colley Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington (19 July 1735 – 22 May 1781) was an Anglo-Irish politician and composer, as well as the father of several distinguished military commanders and politicians of Great Britain and Ireland.

Early lif ...

. His father, Garret Wesley, was the son of Richard Wesley, 1st Baron Mornington

Richard Colley Wesley, 1st Baron Mornington ( – 31 January 1758) was an Irish peer, best remembered as the grandfather of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington.

Biography

Richard Colley (as he was christened) was born around 1690, the son ...

and had a short career in politics representing the constituency Trim

Trim or TRIM may refer to:

Cutting

* Cutting or trimming small pieces off something to remove them

** Book trimming, a stage of the publishing process

** Pruning, trimming as a form of pruning often used on trees

Decoration

* Trim (sewing), or ...

in the Irish House of Commons

The Irish House of Commons was the lower house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from 1297 until 1800. The upper house was the House of Lords. The membership of the House of Commons was directly elected, but on a highly restrictive fra ...

before succeeding his father as 2nd Baron Mornington in 1758. Garret Wesley was also an accomplished composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and Defi ...

and in recognition of his musical and philanthropic achievements was elevated to the rank of Earl of Mornington

Earl of Mornington is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1760 for the Anglo-Irish politician and composer Garret Wellesley, 2nd Baron Mornington. On the death of the fifth earl in 1863, it passed to the Duke of Wellington; si ...

in 1760. Wellesley's mother was the eldest daughter of Arthur Hill-Trevor, 1st Viscount Dungannon

Arthur Hill-Trevor, 1st Viscount Dungannon ( 1694 – 30 January 1771), was an Irish politician.

Born Arthur Hill, he adopted the surname Hill-Trevor in 1759. He was the second son of Michael Hill of Hillsborough, M.P. and Privy Councillor, and ...

, after whom Wellesley was named.

Wellesley was the sixth of nine children born to the Earl and Countess of Mornington. His siblings included Richard, Viscount Wellesley (1760–1842); later 1st Marquess Wellesley

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

, 2nd Earl of Mornington

Earl of Mornington is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1760 for the Anglo-Irish politician and composer Garret Wellesley, 2nd Baron Mornington. On the death of the fifth earl in 1863, it passed to the Duke of Wellington; si ...

, Baron Maryborough

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

.

Birth date and place

The exact date and location of Wellesley's birth is not known; however, biographers mostly follow the same contemporary newspaper evidence which states that he was born on 1 May 1769, the day before he was baptised in St Peters Church, Dublin. However, states "registry of St. Peter's Church, Dublin, shows that he was christened there on 30 April 1769". His baptismal font was donated to St. Nahi's Church inDundrum, Dublin

Dundrum (, ''the ridge fort''), originally a town in its own right, is an outer suburb of Dublin, Ireland. The area is located in the Dublin postal districts, postal districts of Dublin 14 and Dublin 16. Dundrum is home to the Dundrum Town Centr ...

, in 1914. As to the place of Wellesley's birth, he was most likely born at his parents' townhouse, 24 Upper Merrion Street

Merrion Street (; ) is a major Georgian street on the southside of Dublin, Ireland, which runs along one side of Merrion Square. It is divided into Merrion Street Lower (north end), Merrion Square West and Merrion Street Upper (south end). It h ...

, Dublin, now the Merrion Hotel

Merrion Hotel is a hotel in Dublin, Ireland, which comprises a block of four terraced houses on Upper Merrion Street, built in the 1760s by Charles Monck, 1st Viscount Monck, for wealthy Irish merchants and nobility. He lived in No. 22, which b ...

. This contrasts with reports that his mother Anne, Countess of Mornington, recalled in 1815 that he had been born at 6 Merrion Street, Dublin. Other places have been put forward as the location of his birth, including Mornington House

Mornington House was the Dublin social season Georgian era, Georgian residence of the Earl of Mornington, Earls of Mornington. It is Number 24 Merrion Street, close to Leinster House, the former city residence of the Duke of Leinster, Dukes of Lei ...

(the house next door on Upper Merrion), as his father had asserted and the Dublin packet boat

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

.

Childhood

Wellesley spent most of his childhood at his family's two homes, the first a large house in Dublin and the second

Wellesley spent most of his childhood at his family's two homes, the first a large house in Dublin and the second Dangan Castle

Dangan Castle is a former stately home in County Meath, Ireland, which is now in a state of ruin. It is situated by Dangan Church on the Trim Road. The castle is the former seat of the Wesley (Wellesley) family and is located outside the villag ...

, north of Summerhill Summerhill or Summer Hill may refer to the following places:

Australia

* Summer Hill, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney

*Summerhill, Tasmania, a suburb of Launceston

* Summerhill (Mount Duneed), a prefabricated iron cottage in Victoria

Canada

* ...

in County Meath

County Meath (; gle, Contae na Mí or simply ) is a county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Ireland, within the province of Leinster. It is bordered by Dublin to the southeast, Louth to the northeast, Kildare to the south, Offaly to the sou ...

. In 1781, Arthur's father died and his eldest brother Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

inherited his father's earldom.

He went to the diocesan school in Trim

Trim or TRIM may refer to:

Cutting

* Cutting or trimming small pieces off something to remove them

** Book trimming, a stage of the publishing process

** Pruning, trimming as a form of pruning often used on trees

Decoration

* Trim (sewing), or ...

when at Dangan, Mr Whyte's Academy when in Dublin, and Brown's School in Chelsea when in London. He then enrolled at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

, where he studied from 1781 to 1784. His loneliness there caused him to hate it, and makes it highly unlikely that he actually said "The Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton", a quotation which is often attributed to him. Moreover, Eton had no playing fields at the time. In 1785, a lack of success at Eton, combined with a shortage of family funds due to his father's death, forced the young Wellesley and his mother to move to Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

. Until his early twenties, Arthur showed little sign of distinction and his mother grew increasingly concerned at his idleness, stating, "I don't know what I shall do with my awkward son Arthur."

In 1786, Arthur enrolled in the French Royal Academy of Equitation in Angers

Angers (, , ) is a city in western France, about southwest of Paris. It is the prefecture of the Maine-et-Loire department and was the capital of the province of Anjou until the French Revolution. The inhabitants of both the city and the prov ...

, where he progressed significantly, becoming a good horseman and learning French, which later proved very useful. Upon returning to England in later the same year, he astonished his mother with his improvement.

Early military career

United Kingdom

Despite his new promise, Wellesley had yet to find a job and his family was still short of money, so upon the advice of his mother, his brother Richard asked his friend the

Despite his new promise, Wellesley had yet to find a job and his family was still short of money, so upon the advice of his mother, his brother Richard asked his friend the Duke of Rutland

Duke of Rutland is a title in the Peerage of England, named after Rutland, a county in the East Midlands of England. Earldoms named after Rutland have been created three times; the ninth earl of the third creation was made duke in 1703, in who ...

(then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kingdo ...

) to consider Arthur for a commission in the Army. Soon afterward, on 7 March 1787, he was gazetted ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

in the 73rd Regiment of Foot. In October, with the assistance of his brother, he was assigned as '' aide-de-camp'', on ten shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

s a day (twice his pay as an ensign), to the new Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Buckingham

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

. He was also transferred to the new 76th Regiment

The 76th Regiment of Foot was a British Army regiment, raised in 1787. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the Duke of Wellington's Regiment, 33rd (Duke of Wellington's) Regiment to form the Duke of Wellington's Regiment in 1881.

Hi ...

forming in Ireland and on Christmas Day, 1787, was promoted lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

. During his time in Dublin his duties were mainly social; attending balls, entertaining guests and providing advice to Buckingham. While in Ireland, he overextended himself in borrowing due to his occasional gambling, but in his defence stated that "I have often known what it was to be in want of money, but I have never got helplessly into debt".

On 23 January 1788, he transferred into the 41st Regiment of Foot

The 41st (Welch) Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, raised in 1719. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot to form the Welch Regiment in 1881.

History

Early hist ...

, then again on 25 June 1789 he transferred to the 12th (Prince of Wales's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons and, according to military historian Richard Holmes, he also reluctantly entered politics. Shortly before the general election of 1789, he went to the rotten borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorat ...

of Trim

Trim or TRIM may refer to:

Cutting

* Cutting or trimming small pieces off something to remove them

** Book trimming, a stage of the publishing process

** Pruning, trimming as a form of pruning often used on trees

Decoration

* Trim (sewing), or ...

to speak against the granting of the title "Freeman

Freeman, free men, or variant, may refer to:

* a member of the Third Estate in medieval society (commoners), see estates of the realm

* Freeman, an apprentice who has been granted freedom of the company, was a rank within Livery companies

* Free ...

" of Dublin to the parliamentary leader of the Irish Patriot Party

The Irish Patriot Party was the name of a number of different political groupings in Ireland throughout the 18th century. They were primarily supportive of Whig concepts of personal liberty combined with an Irish identity that rejected full inde ...

, Henry Grattan

Henry Grattan (3 July 1746 – 4 June 1820) was an Irish politician and lawyer who campaigned for legislative freedom for the Irish Parliament in the late 18th century from Britain. He was a Member of the Irish Parliament (MP) from 1775 to 18 ...

. Succeeding, he was later nominated and duly elected as a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) for Trim

Trim or TRIM may refer to:

Cutting

* Cutting or trimming small pieces off something to remove them

** Book trimming, a stage of the publishing process

** Pruning, trimming as a form of pruning often used on trees

Decoration

* Trim (sewing), or ...

in the Irish House of Commons

The Irish House of Commons was the lower house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from 1297 until 1800. The upper house was the House of Lords. The membership of the House of Commons was directly elected, but on a highly restrictive fra ...

. Because of the limited suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

at the time, he sat in a parliament where at least two-thirds of the members owed their election to the landowners of fewer than a hundred boroughs. Wellesley continued to serve at Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the se ...

, voting with the government in the Irish parliament over the next two years. He became a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 30 January 1791, and was transferred to the 58th Regiment of Foot

The 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot was a British Army line infantry regiment, raised in 1755. Under the Childers Reforms it amalgamated with the 48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot to form the Northamptonshire Regiment in 1881.

His ...

.

On 31 October, he transferred to the 18th Light Dragoons

The 18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary's Own) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, first formed in 1759. It saw service for two centuries, including the First World War before being amalgamated with the 13th Hussars to form the 13th/18th Royal H ...

and it was during this period that he grew increasingly attracted to Kitty Pakenham

Catherine Sarah Dorothea Wellesley, Duchess of Wellington (; 14 January 1773 – 24 April 1831), known before her marriage as Kitty Pakenham, was the wife of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington.

Early life

Catherine Pakenham was born on 14 ...

, the daughter of Edward Pakenham, 2nd Baron Longford

Edward Michael Pakenham, 2nd Baron Longford (1 April 1743 – 3 June 1792) was an Irish sailor and landowner.

Early life

Pakenham was the son of Thomas Pakenham, 1st Baron Longford and Elizabeth Cuffe, 1st Countess of Longford. His parents had ...

. She was described as being full of 'gaiety and charm'. In 1793, he proposed, but was turned down by her brother Thomas, Earl of Longford, who considered Wellesley to be a young man, in debt, with very poor prospects. An aspiring amateur musician, Wellesley, devastated by the rejection, burnt his violin

The violin, sometimes known as a ''fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone (string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in the family in regular ...

s in anger, and resolved to pursue a military career in earnest. He became a major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

by purchase in the 33rd Regiment in 1793. A few months later, in September, his brother lent him more money and with it he purchased a lieutenant-colonelcy in the 33rd.

Netherlands

In 1793, the Duke of York was sent to

In 1793, the Duke of York was sent to Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

in command of the British contingent of an allied force destined for the invasion of France. In June 1794, Wellesley with the 33rd regiment set sail from Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

bound for Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

as part of an expedition bringing reinforcements for the army in Flanders. They arrived too late to participate, and joined the Duke of York as he was pulling back towards the Netherlands. On 15 September 1794, at the Battle of Boxtel, east of Breda

Breda () is a city and municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the province of North Brabant. The name derived from ''brede Aa'' ('wide Aa' or 'broad Aa') and refers to the confluence of the rivers Mark and Aa. Breda has ...

, Wellington, in temporary command of his brigade, had his first experience of battle. During General Abercromby's withdrawal in the face of superior French forces, the 33rd held off enemy cavalry, allowing neighbouring units to retreat safely. During the extremely harsh winter that followed, Wellesley and his regiment formed part of an allied force holding the defence line along the Waal River

The Waal (Dutch name, ) is the main distributary branch of the river Rhine flowing approximately through the Netherlands. It is the major waterway connecting the port of Rotterdam to Germany. Before it reaches Rotterdam, it joins with the Afg ...

. The 33rd, along with the rest of the army, suffered heavy losses from attrition and illness. Wellesley's health was also affected by the damp environment. Though the campaign was to end disastrously, with the British army driven out of the United Provinces into the German states, Wellesley became more aware of battle tactics, including the use of lines of infantry against advancing columns, and the merits of supporting sea-power. He understood that the failure of the campaign was due in part to the faults of the leaders and the poor organisation at headquarters. He remarked later of his time in the Netherlands that "At least I learned what not to do, and that is always a valuable lesson".

Returning to England in March 1795, he was reinstated as a member of parliament for Trim for a second time. He hoped to be given the position of secretary of war in the new Irish government but the new lord-lieutenant, Lord Camden

Marquess Camden is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1812 for the politician John Pratt, 2nd Earl Camden. The Pratt family descends from Sir John Pratt, Lord Chief Justice from 1718 to 1725. His third son from his ...

, was only able to offer him the post of Surveyor-General of the Ordnance

The Surveyor-General of the Ordnance was a subordinate of the Master-General of the Ordnance and a member of the Board of Ordnance, a British government body, from its constitution in 1597. Appointments to the post were made by the crown under Le ...

. Declining the post, he returned to his regiment, now at Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

preparing to set sail for the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. After seven weeks at sea, a storm forced the fleet back to Poole

Poole () is a large coastal town and seaport in Dorset, on the south coast of England. The town is east of Dorchester and adjoins Bournemouth to the east. Since 1 April 2019, the local authority is Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Counc ...

.The 33rd was given time to recuperate and a few months later, Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

decided to send the regiment to India. Wellesley was promoted full colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

by seniority on 3 May 1796 and a few weeks later set sail for Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

with his regiment.

India

Arriving inCalcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

in February 1797 he spent 5 months there, before being sent in August to a brief expedition to the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, where he established a list of new hygiene precautions for his men to deal with the unfamiliar climate. Returning in November to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, he learnt that his elder brother Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

, now known as Lord Mornington, had been appointed as the new Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

.

In 1798, he changed the spelling of his surname to "Wellesley"; up to this time he was still known as Wesley, which his eldest brother considered the ancient and proper spelling.

Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

As part of the campaign to extend the rule of the

As part of the campaign to extend the rule of the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

, the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

The Fourth Anglo-Mysore War was a conflict in South India between the Kingdom of Mysore against the British East India Company and the Hyderabad Deccan in 1798–99.

This was the final conflict of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. The British captured ...

broke out in 1798 against the Sultan of Mysore

Mysore (), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern part of the state of Karnataka, India. Mysore city is geographically located between 12° 18′ 26″ north latitude and 76° 38′ 59″ east longitude. It is located at an altitude of ...

, Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He int ...

. Arthur's brother Richard ordered that an armed force be sent to capture Seringapatam

Srirangapatna is a town and headquarters of one of the seven Taluks of Mandya district, in the Indian State of Karnataka. It gets its name from the Ranganthaswamy temple consecrated at around 984 CE. Later, under the British rule the city wa ...

and defeat Tipu. During the war, rockets were used on several occasions. Wellesley was almost defeated by Tipu's Diwan, Purnaiah

Purnaiah (Purniya) (1746 – 27 March 1812), aka Krishnacharya Purniya or Mir Miran Purniya was an Indian Administrator and statesman and the 1st Diwan of Mysore. He has the rare distinction of governing under a sultan and a maharaja, Tip ...

, at the Battle of Sultanpet Tope. Quoting Forrest,

At this point (near the village of Sultanpet, Figure 5) there was a large tope, or grove, which gave shelter to Tipu's rocketmen and had obviously to be cleaned out before the siege could be pressed closer to Srirangapattana island. The commander chosen for this operation was Col. Wellesley, but advancing towards the tope after dark on the 5 April 1799, he was set upon with rockets and musket-fires, lost his way and, as Beatson politely puts it, had to "postpone the attack" until a more favourable opportunity should offer.The following day, Wellesley launched a fresh attack with a larger force, and took the whole position without any killed in action. On 22 April 1799, twelve days before the main battle, rocketeers maneuvered to the rear of the British encampment, then 'threw a great number of rockets at the same instant' to signal the beginning of an assault by 6,000 Indian infantry and a corps of Frenchmen, all ordered by Mir Golam Hussain and Mohomed Hulleen Mir Miran. The rockets had a range of about 1,000 yards. Some burst in the air like shells. Others, called ground rockets, would rise again on striking the ground and bound along in a serpentine motion until their force was spent. According to one British observer, a young English officer named Bayly: "So pestered were we with the rocket boys that there was no moving without danger from the destructive missiles ...". He continued:

The rockets and musketry from 20,000 of the enemy were incessant. No hail could be thicker. Every illumination of blue lights was accompanied by a shower of rockets, some of which entered the head of the column, passing through to the rear, causing death, wounds, and dreadful lacerations from the long bamboos of twenty or thirty feet, which are invariably attached to them.Under the command of General Harris, some 24,000 troops were dispatched to

Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

(to join an equal force being sent from Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

in the west). Arthur and the 33rd sailed to join them in August.

After extensive and careful logistic preparation (which would become one of Wellesley's main attributes) the 33rd left with the main force in December and travelled across of jungle from Madras to Mysore. On account of his brother, during the journey, Wellesley was given an additional command, that of chief advisor to the Nizam

The Nizams were the rulers of Hyderabad from the 18th through the 20th century. Nizam of Hyderabad (Niẓām ul-Mulk, also known as Asaf Jah) was the title of the monarch of the Hyderabad State ( divided between the state of Telangana, Mar ...

of Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River (India), Musi River, in the northern part ...

's army (sent to accompany the British force). This position was to cause friction among many of the senior officers (some of whom were senior to Wellesley). Much of this friction was put to rest after the Battle of Mallavelly

The Battle of Mallavelly (also spelled Malvilly or Malavalli) was fought on 27 March 1799 between forces of the British East India Company and the Kingdom of Mysore during the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War. The British forces, led by General George H ...

, some from Seringapatam, in which Harris' army attacked a large part of the sultan's army. During the battle, Wellesley led his men, in a line of battle of two ranks, against the enemy to a gentle ridge and gave the order to fire. After an extensive repetition of volleys, followed by a bayonet charge, the 33rd, in conjunction with the rest of Harris's force, forced Tipu's infantry to retreat.

=Seringapatam

= Immediately after their arrival atSeringapatam

Srirangapatna is a town and headquarters of one of the seven Taluks of Mandya district, in the Indian State of Karnataka. It gets its name from the Ranganthaswamy temple consecrated at around 984 CE. Later, under the British rule the city wa ...

on 5 April 1799, the Battle of Seringapatam

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

began and Wellesley was ordered to lead a night attack on the village of Sultanpettah, adjacent to the fortress to clear the way for the artillery. Because of a variety of factors including the Mysorean army's strong defensive preparations and the darkness the attack failed with 25 casualties due to confusion among the British. Wellesley suffered a minor injury to his knee from a spent musket-ball. Although they would re-attack successfully the next day, after time to scout ahead the enemy's positions, the affair affected Wellesley. He resolved "never to attack an enemy who is preparing and strongly posted, and whose posts have not been reconnoitred by daylight".

Lewin Bentham Bowring

Lewin Bentham Bowring (1824–1910) was a British Indian civil servant in British India who served as the Chief Commissioner of Mysore between 1862 and 1870. He was also an author and man of letters.

Family

He was the second son of Sir John Bowr ...

gives this alternative account:

One of these groves, called the Sultanpet Tope, was intersected by deep ditches, watered from a channel running in an easterly direction about a mile from the fort.A few weeks later, after extensive artillery bombardment, a breach was opened in the main walls of the fortress of Seringapatam. An attack led by Major-General Baird secured the fortress. Wellesley secured the rear of the advance, posting guards at the breach and then stationed his regiment at the main palace. After hearing news of the death of the Tipu Sultan, Wellesley was the first at the scene to confirm his death, checking his pulse. Over the coming day, Wellesley grew increasingly concerned over the lack of discipline among his men, who drank and pillaged the fortress and city. To restore order, several soldiers wereGeneral Baird General Sir David Baird, 1st Baronet, of Newbyth, GCB (6 December 1757 – 18 August 1829) was a British Army officer. Military career He was born at Newbyth House in Haddingtonshire, Scotland, the son of an Edinburgh merchant family, and enter ...was directed to scour this grove and dislodge the enemy, but on his advancing with this object on the night of the 5th, he found the tope unoccupied. The next day, however, the Mysore troops again took possession of the ground, and as it was absolutely necessary to expel them, two columns were detached at sunset for the purpose. The first of these, under Colonel Shawe, got possession of a ruined village, which it successfully held. The second column, under Colonel Wellesley, on advancing into the tope, was at once attacked in the darkness of night by a tremendous fire of musketry and rockets. The men, floundering about amidst the trees and the water-courses, at last broke, and fell back in disorder, some being killed and a few taken prisoners. In the confusion Colonel Wellesley was himself struck on the knee by a spent ball, and narrowly escaped falling into the hands of the enemy.

flogged

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, Birching, rods, Switch (rod), switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging ...

and four hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging in ...

.

After battle and the resulting end of the war, the main force under General Harris left Seringapatam and Wellesley, aged 30, stayed behind to command the area as the new Governor of Seringapatam and Mysore. While in India, Wellesley was ill for a considerable time, first with severe diarrhoea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

from the water and then with fever, followed by a serious skin infection caused by trichophyton

''Trichophyton'' is a genus of fungi, which includes the parasitic varieties that cause tinea, including athlete's foot, ringworm, jock itch, and similar infections of the nail, beard, skin and scalp. Trichophyton fungi are molds characterized ...

.

Wellesley was in charge of raising an Anglo-Indian expeditionary force in Trincomali

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

in early 1801 for the capture of Batavia and Mauritius from the French. However, on the eve of its departure, orders arrived from England that it was to be sent to Egypt to co-operate with Sir Ralph Abercromby in the expulsion of the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. Wellesley had been appointed second in command to Baird, but owing to ill health did not accompany the expedition on 9 April 1801. This was fortunate for Wellesley, since the very vessel on which he was to have sailed sank in the Red Sea.

He was promoted to brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

on 17 July 1801. He took residence within the Sultan's summer palace and reformed the tax and justice systems in his province to maintain order and prevent bribery. He also defeated the rebel warlord Dhoondiah Waugh in the Battle of Conaghull, after the latter had escaped from prison in Seringapatam during the battle there.

=Dhoondiah Waugh insurgency

= In 1800, whilst serving as Governor of Mysore, Wellesley was tasked with putting down aninsurgency

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irregu ...

led by Dhoondiah Waugh, formerly a Patan trooper for Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He int ...

. After the fall of Seringapatam he became a powerful brigand, raiding villages along the Maratha–Mysore border region. Despite initial setbacks, the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

having pursued and destroyed his forces once already, forcing him into retreat in August 1799, he raised a sizeable force composed of disbanded Mysore soldiers, captured small outposts and forts in Mysore, and was receiving the support of several Maratha ''killedar Kiladar was a title for the governor of a fort or large town in medieval India. During the Maratha Empire, the title was commonly pronounced 'Killedar' (Marathi: किल्लेदार). The office of ''Kiladar'' had the same functions as that ...

s'' opposed to British occupation. This drew the attention of the British administration, who were beginning to recognise him as more than just a bandit, as his raids, expansion and threats to destabilise British authority suddenly increased in 1800. The death of Tipu Sultan had created a power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has repla ...

and Waugh was seeking to fill it.

Given independent command of a combined East India Company and British Army force, Wellesley ventured north to confront Waugh in June 1800, with an army of 8,000 infantry and cavalry, having learnt that Waugh's forces numbered over 50,000, although the majority (around 30,000) were irregular light cavalry and unlikely to pose a serious threat to British infantry and artillery.

Throughout June–August 1800, Wellesley advanced through Waugh's territory, his troops escalading forts in turn and capturing each one with "trifling loss". The forts generally offered little resistance due to their poor construction and design. Wellesley did not have sufficient troops to garrison each fort and had to clear the surrounding area of insurgents before advancing to the next fort. On 31 July, he had "taken and destroyed Dhoondiah's baggage and six guns, and driven into the Malpoorba (where they were drowned) about five thousand people". Dhoondiah continued to retreat, but his forces were rapidly deserting, he had no infantry and due to the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

weather flooding river crossings he could no longer outpace the British advance. On 10 September, at the Battle of Conaghul, Wellesley personally led a charge of 1,400 British dragoons and Indian cavalry, in single line with no reserve, against Dhoondiah and his remaining 5,000 cavalry. Dhoondiah was killed during the clash, his body was discovered and taken to the British camp tied to a cannon. With this victory, Wellesley's campaign was concluded, and British authority had been restored.

Wellesley, with command of four regiments, had defeated Dhoondiah's larger rebel force, along with Dhoondiah himself, who was killed in the final battle. Wellesley then paid for the future upkeep of Dhoondiah's orphaned son.

Second Anglo-Maratha War

In September 1802, Wellesley learnt that he had been promoted to the rank ofmajor-general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

. He had been gazetted on 29 April 1802, but the news took several months to reach him by sea. He remained at Mysore until November when he was sent to command an army in the Second Anglo-Maratha War

}

The Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805) was the second conflict between the British East India Company and the Maratha Empire in India.

Background

The British had supported the "fugitive" Peshwa Raghunathrao in the First Anglo-Maratha War, ...

.

When he determined that a long defensive war would ruin his army, Wellesley decided to act boldly to defeat the numerically larger force of the Maratha Empire

The Maratha Empire, also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy, was an early modern Indian confederation that came to dominate much of the Indian subcontinent in the 18th century. Maratha rule formally began in 1674 with the coronation of Shi ...

. With the logistic assembly of his army complete (24,000 men in total) he gave the order to break camp and attack the nearest Maratha fort on 8 August 1803. The fort surrendered on 12 August after an infantry attack had exploited an artillery-made breach in the wall. With the fort now in British control Wellesley was able to extend control southwards to the river Godavari

The Godavari ( IAST: ''Godāvarī'' �od̪aːʋəɾiː is India's second longest river after the Ganga river and drains into the third largest basin in India, covering about 10% of India's total geographical area. Its source is in Trimbakesh ...

.

=Assaye, Argaum and Gawilghur

= Splitting his army into two forces, to pursue and locate the main Marathas army, (the second force, commanded by Colonel Stevenson was far smaller) Wellesley was preparing to rejoin his forces on 24 September. His intelligence, however, reported the location of the Marathas' main army, between two rivers near

Splitting his army into two forces, to pursue and locate the main Marathas army, (the second force, commanded by Colonel Stevenson was far smaller) Wellesley was preparing to rejoin his forces on 24 September. His intelligence, however, reported the location of the Marathas' main army, between two rivers near Assaye

Assaye is a small village in the Jalna district of the state of Maharashtra in western India. The village was the location of the Battle of Assaye in 1803, fought between the Maratha Empire and the British East India Company

The East Indi ...

. If he waited for the arrival of his second force, the Marathas would be able to mount a retreat, so Wellesley decided to launch an attack immediately.

On 23 September, Wellesley led his forces over a ford in the river Kaitna and the Battle of Assaye

The Battle of Assaye was a major battle of the Second Anglo-Maratha War fought between the Maratha Empire and the British East India Company. It occurred on 23 September 1803 near Assaye in western India. An outnumbered Indian and British forc ...

commenced. After crossing the ford the infantry was reorganised into several lines and advanced against the Maratha infantry. Wellesley ordered his cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

to exploit the flank of the Maratha army just near the village. During the battle Wellesley himself came under fire; two of his horses were shot from under him and he had to mount a third. At a crucial moment, Wellesley regrouped his forces and ordered Colonel Maxwell (later killed in the attack) to attack the eastern end of the Maratha position while Wellesley himself directed a renewed infantry attack against the centre.

An officer in the attack wrote of the importance of Wellesley's personal leadership: "The General was in the thick of the action the whole time ... I never saw a man so cool and collected as he was ... though I can assure you, 'til our troops got the order to advance the fate of the day seemed doubtful ..." With some 6,000 Marathas killed or wounded, the enemy was routed, though Wellesley's force was in no condition to pursue. British casualties were heavy: the British losses amounted to 428 killed, 1,138 wounded and 18 missing (the British casualty figures were taken from Wellesley's own despatch). Wellesley was troubled by the loss of men and remarked that he hoped "I should not like to see again such loss as I sustained on 23 September, even if attended by such gain". Years later, however, he remarked that Assaye, and not Waterloo, was the best battle he ever fought.

Despite the damage done to the Maratha army, the battle did not end the war. A few months later in November, Wellesley attacked a larger force near Argaum, leading his army to victory again, with an astonishing 5,000 enemy dead at the cost of only 361 British casualties. A further successful attack at the fortress at Gawilghur

Gawilghur (also, Gavalgadh, Gawilgarh or Gawilgad, Pronunciation: �aːʋilɡəɖ was a well-fortified mountain stronghold of the Maratha Empire north of the Deccan Plateau, in the vicinity of Melghat Tiger Reserve, Amravati District, Mahara ...

, combined with the victory of General Lake

Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake (27 July 1744 – 20 February 1808) was a British general. He commanded British forces during the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and later served as Commander-in-Chief of the military in British India.

Background

He was ...

at Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

forced the Maratha to sign a peace settlement at Anjangaon

Anjangaon is a city and a municipal council in Amravati district in the state of Maharashtra, India. Anjangaon City got the status of Municipal Council in 1930. It is the first municipal council established in Amravati district and the second ...

(not concluded until a year later) called the Treaty of Surji-Anjangaon

The Treaty of Surji-Anjangaon was signed on 30 December 1803 between the British and Daulat Rao Sindhia, chief of the Maratha Confederacy at Anjangaon town located in Maharashtra.

On 30 December 1803, the Sindhia signed the Treaty of Surji-Anj ...

.

Military historian Richard Holmes remarked that Wellesley's experiences in India had an important influence on his personality and military tactics, teaching him much about military matters that would prove vital to his success in the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

. These included a strong sense of discipline through drill and order, the use of diplomacy to gain allies, and the vital necessity of a secure supply line. He also established high regard for the acquisition of intelligence through scouts and spies. His personal tastes also developed, including dressing himself in white trousers, a dark tunic, with Hessian boots and black cocked hat (that later became synonymous as his style).

=Leaving India