The Dream of Gerontius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by

Edward Elgar was not the first composer to think about setting

Edward Elgar was not the first composer to think about setting  Composition proceeded quickly. Elgar and August Jaeger, his editor at the publisher

Composition proceeded quickly. Elgar and August Jaeger, his editor at the publisher

"Elgar, Sir Edward William, baronet (1857–1934)".

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 22 April 2010 . Shortly after the premiere, the German conductor and chorus master Julius Buths made a German translation of the text and arranged a successful performance in ''The Dream of Gerontius'' received its US premiere on 23 March 1903 at The Auditorium, Chicago, conducted by Harrison M. Wild. It was given in New York, conducted by Walter Damrosch three days later. It was performed in Sydney, in 1903. The first performance in Vienna was in 1905; the Paris premiere was in 1906; and by 1911 the work received its Canadian premiere in

''The Dream of Gerontius'' received its US premiere on 23 March 1903 at The Auditorium, Chicago, conducted by Harrison M. Wild. It was given in New York, conducted by Walter Damrosch three days later. It was performed in Sydney, in 1903. The first performance in Vienna was in 1905; the Paris premiere was in 1906; and by 1911 the work received its Canadian premiere in

Newman's poem tells the story of a soul's journey through death, and provides a meditation on the unseen world of

Newman's poem tells the story of a soul's journey through death, and provides a meditation on the unseen world of

"Elgar, Sir Edward."

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed 21 October 2010. Richter signed the autograph copy of the score with the inscription: "Let drop the Chorus, let drop everybody—but let not drop the wings of your original genius."''

The Best of Me – A Gerontius Companion

* * * * *

The Elgar Birthplace Museum

''The Dream of Gerontius'' on CD

*

(Note: Elgar used about half the poem in his libretto.)

* ttp://www.elgar.org/3gerontt.htm Elgar – His Music : ''The Dream of Gerontius'' – A Musical Analysis– first of a set of six pages on the work

A comparative review of the available recordings, at least up to 1997

''The Dream of Gerontius'' (1899–1900), analysis

an

synopsis

BBC {{DEFAULTSORT:Dream Of Gerontius, The Music based on poems Compositions by Edward Elgar Oratorios 1900 compositions Music for orchestra and organ Death in music

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

in 1900, to text from the poem

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in E ...

by John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican priest and later as a Catholic priest and ...

. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment before God and settling into Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgat ...

. Elgar disapproved of the use of the term " oratorio" for the work (and the term occurs nowhere in the score), though his wishes are not always followed. The piece is widely regarded as Elgar's finest choral work, and some consider it his masterpiece.

The work was composed for the Birmingham Music Festival of 1900; the first performance took place on 3 October 1900, in Birmingham Town Hall. It was badly performed at the premiere, but later performances in Germany revealed its stature. In the first decade after its premiere, the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

theology in Newman's poem caused difficulties in getting the work performed in Anglican cathedrals, and a revised text was used for performances at the Three Choirs Festival

200px, Worcester cathedral

200px, Gloucester cathedral

The Three Choirs Festival is a music festival held annually at the end of July, rotating among the cathedrals of the Three Counties (Hereford, Gloucester and Worcester) and originally fea ...

until 1910.

History

Edward Elgar was not the first composer to think about setting

Edward Elgar was not the first composer to think about setting John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican priest and later as a Catholic priest and ...

's poem " The Dream of Gerontius". Dvořák had considered it fifteen years earlier, and had discussions with Newman, before abandoning the idea. Elgar knew the poem well; he had owned a copy since at least 1885, and in 1889 he was given another as a wedding present. This copy contained handwritten transcriptions of extensive notes that had been made by General Gordon, and Elgar is known to have thought of the text in musical terms for several years. Throughout the 1890s, Elgar had composed several large-scale works for the regular festivals that were a key part of Britain's musical life. In 1898, based on his growing reputation, he was asked to write a major work for the 1900 Birmingham Triennial Music Festival. He was unable to start work on the poem that he knew so well until the autumn of 1899, and did so only after first considering a different subject.Moore, p. 296

Composition proceeded quickly. Elgar and August Jaeger, his editor at the publisher

Composition proceeded quickly. Elgar and August Jaeger, his editor at the publisher Novello Novello may refer to:

Places

* Novello, Piedmont, a ''comune'' in the Province of Cuneo, Italy

* Novello Theatre, a theatre in the City of Westminster, London, England

People Given name

* Clara Novello Davies (1861–1943), Welsh singer, named af ...

, exchanged frequent, sometimes daily, letters, which show how Jaeger helped in shaping the work, and in particular the climactic depiction of the moment of judgment.Moore, p. 322 By the time Elgar had completed the work and Novello had printed it, there were only three months to the premiere. The Birmingham chorus, all amateurs, struggled to master Elgar's complex, demanding and somewhat revolutionary work. Matters were made worse by the sudden death of the chorus master Charles Swinnerton Heap and his replacement by William Stockley, an elderly musician who found the music beyond him. The conductor of the premiere, Hans Richter, received a copy of the full score only on the eve of the first orchestral rehearsal. The soloists at the Birmingham Festival on 3 October 1900 were Marie Brema, Edward Lloyd and Harry Plunket Greene. The first performance was, famously, a near disaster. The choir could not sing the music adequately, and two of the three soloists were in poor voice. Elgar was deeply upset at the debacle, telling Jaeger, "I have allowed my heart to open once – it is now shut against every religious feeling & every soft, gentle impulse for ever." However, many of the critics could see past the imperfect realisation and the work became established in Britain once it had had its first London performance on 6 June 1903, at the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

Westminster Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral is the mother church of the Catholic Church in England and Wales. It is the largest Catholic church in the UK and the seat of the Archbishop of Westminster.

The site on which the cathedral stands in the City o ...

. Kennedy, Michael"Elgar, Sir Edward William, baronet (1857–1934)".

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 22 April 2010 . Shortly after the premiere, the German conductor and chorus master Julius Buths made a German translation of the text and arranged a successful performance in

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

on 19 December 1901. Elgar was present, and he wrote "It completely bore out my idea of the work: the chorus was very fine". Buths presented it in Düsseldorf again on 19 May 1902 in conjunction with the Lower Rhenish Music Festival. The soloists included Muriel Foster and tenor Ludwig Wüllner, and Elgar was again in the audience, being called to the stage twenty times to receive the audience's applause. This was the performance that finally convinced Elgar for the first time that he had written a truly satisfying work. Buths's festival co-director Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic music, Romantic and early Modernism (music), modern eras, he has been descr ...

was impressed enough by what he heard that at a post-concert banquet he said: "I drink to the success and welfare of the first English progressive musician, Meister Elgar". This greatly pleased Elgar,Moore, p. 368 who considered Strauss to be "the greatest genius of the age".

The strong Roman Catholicism of the work gave rise to objections in some influential British quarters; some Anglican clerics insisted that for performances in English cathedrals Elgar should modify the text to tone down the Roman Catholic references. There was no Anglican objection to Newman's words in general: Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan (13 May 1842 – 22 November 1900) was an English composer. He is best known for 14 operatic collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including ''H.M.S. Pinafore'', '' The Pirates of Penzance ...

's setting of his " Lead, Kindly Light", for example, was sung at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

in 1904.''The Times'', 13 February 1904, p. 13 Disapproval was reserved for the doctrinal aspects of ''The Dream of Gerontius'' repugnant to Anglicans, such as Purgatory. Elgar was unable to resist the suggested bowdlerisation

Expurgation, also known as bowdlerization, is a form of censorship that involves purging anything deemed noxious or offensive from an artistic work or other type of writing or media.

The term ''bowdlerization'' is a pejorative term for the pract ...

, and in the ten years after the premiere the work was given at the Three Choirs Festival

200px, Worcester cathedral

200px, Gloucester cathedral

The Three Choirs Festival is a music festival held annually at the end of July, rotating among the cathedrals of the Three Counties (Hereford, Gloucester and Worcester) and originally fea ...

with an expurgated text. The Dean of Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east of t ...

refused admission to the work until 1910. This attitude lingered until the 1930s, when the Dean of Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

banned the work from the cathedral. Elgar was also faced with many people's assumption that he would use the standard hymn tunes for the sections of the poem that had already been absorbed into Anglican hymn books: "Firmly I believe and truly", and "Praise to the Holiest in the Height".

''The Dream of Gerontius'' received its US premiere on 23 March 1903 at The Auditorium, Chicago, conducted by Harrison M. Wild. It was given in New York, conducted by Walter Damrosch three days later. It was performed in Sydney, in 1903. The first performance in Vienna was in 1905; the Paris premiere was in 1906; and by 1911 the work received its Canadian premiere in

''The Dream of Gerontius'' received its US premiere on 23 March 1903 at The Auditorium, Chicago, conducted by Harrison M. Wild. It was given in New York, conducted by Walter Damrosch three days later. It was performed in Sydney, in 1903. The first performance in Vienna was in 1905; the Paris premiere was in 1906; and by 1911 the work received its Canadian premiere in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most pop ...

under the baton of the composer.

In the first decades after its composition leading performers of the tenor part included Gervase Elwes and John Coates, and Louise Kirkby Lunn

Louise Kirkby Lunn (8 November 1873 – 17 February 1930) was an English contralto (sometimes classified as a mezzo-soprano). Born into a working-class family in Manchester, She appeared in many French and Italian operas, but was best known as ...

, Elena Gerhardt and Julia Culp were admired as the Angel. Later singers associated with the work include Muriel Foster, Clara Butt, Kathleen Ferrier

Kathleen Mary Ferrier, CBE (22 April 19128 October 1953) was an English contralto singer who achieved an international reputation as a stage, concert and recording artist, with a repertoire extending from folksong and popular ballads to the c ...

, and Janet Baker as the Angel, and Heddle Nash, Steuart Wilson, Tudor Davies and Richard Lewis as Gerontius.Farach Colton, Andrew, "Vision of the Hereafter", ''Gramophone'', February 2003, p. 36

The work has come to be generally regarded as Elgar's finest choral composition. The ''Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language ''Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and the ...

'' rates it as "one of his three or four finest works", and the authors of '' The Record Guide'', writing in 1956 when Elgar's music was comparatively neglected, said, "Anyone who doubts the fact of Elgar's genius should take the first opportunity of hearing ''The Dream of Gerontius'', which remains his masterpiece, as it is his largest and perhaps most deeply felt work." In the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Michael Kennedy writes, " e work has become as popular with British choral societies as ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

'' and ''Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/ YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books ...

'', although its popularity overseas did not survive 1914. Many regard it as Elgar's masterpiece. ... It is unquestionably the greatest British work in the oratorio form, although Elgar was right in believing that it could not accurately be classified as oratorio or cantata."

Synopsis

Newman's poem tells the story of a soul's journey through death, and provides a meditation on the unseen world of

Newman's poem tells the story of a soul's journey through death, and provides a meditation on the unseen world of Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

theology. Gerontius (a name derived from the Greek word ''geron'', "old man") is a devout Everyman

The everyman is a stock character of fiction. An ordinary and humble character, the everyman is generally a protagonist whose benign conduct fosters the audience's identification with them.

Origin

The term ''everyman'' was used as early as ...

. Elgar's setting uses most of the text of the first part of the poem, which takes place on Earth, but omits many of the more meditative sections of the much longer, otherworldly second part, tightening the narrative flow.

In the first part, we hear Gerontius as a dying man of faith, by turns fearful and hopeful, but always confident. A group of friends (also called "assistants" in the text) joins him in prayer and meditation. He passes in peace, and a priest, with the assistants, sends him on his way with a valediction. In the second part, Gerontius, now referred to as "The Soul", awakes in a place apparently without space or time, and becomes aware of the presence of his guardian angel

A guardian angel is a type of angel that is assigned to protect and guide a particular person, group or nation. Belief in tutelary deity, tutelary beings can be traced throughout all antiquity. The idea of angels that guard over people played a ...

, who expresses joy at the culmination of his task (Newman conceived the Angel as male; Elgar gives the part to a female singer, but retains the references to the angel as male). After a long dialogue, they journey towards the judgment throne.

They safely pass a group of demons

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in Media (communication), media such as comics, video ...

, and encounter choirs of angels, eternally praising God for His grace and forgiveness. The Angel of the Agony pleads with Jesus to spare the souls of the faithful. Finally Gerontius glimpses God and is judged in a single moment. The Guardian Angel lowers Gerontius into the soothing lake of Purgatory, with a final benediction and promise of a re-awakening to glory.

Music

Forces

The work calls for a large orchestra of typicallate Romantic

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

proportions, double chorus with semichorus, and usually three soloists. Gerontius is sung by a tenor

A tenor is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The low extreme for tenors i ...

, and the Angel is a mezzo-soprano. The Priest's part is written for a baritone, while the Angel of the Agony is more suited to a bass

Bass or Basses may refer to:

Fish

* Bass (fish), various saltwater and freshwater species

Music

* Bass (sound), describing low-frequency sound or one of several instruments in the bass range:

** Bass (instrument), including:

** Acoustic bass gui ...

; as both parts are short they are usually sung by the same performer, although some performances assign different singers for the two parts.

The choir plays several roles: attendants and friends, demons, Angelicals (women only) and Angels, and souls in Purgatory. They are employed at different times as a single chorus in four parts, or as a double chorus in eight parts or antiphonal

An antiphonary or antiphonal is one of the liturgical books intended for use (i.e. in the liturgical choir), and originally characterized, as its name implies, by the assignment to it principally of the antiphons used in various parts of the ...

ly. The semichorus is used for music of a lighter texture; usually in performance they are composed of a few members of the main chorus; however, Elgar himself preferred to have the semi-chorus placed near the front of the stage.

The required instrumentation comprises two flutes (II doubling piccolo), two oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

...

s and cor anglais

The cor anglais (, or original ; plural: ''cors anglais''), or English horn in North America, is a double-reed woodwind instrument in the oboe family. It is approximately one and a half times the length of an oboe, making it essentially an al ...

, two clarinets in B and A and bass clarinet

The bass clarinet is a musical instrument of the clarinet family. Like the more common soprano B clarinet, it is usually pitched in B (meaning it is a transposing instrument on which a written C sounds as B), but it plays notes an octave ...

, two bassoons and contrabassoon

The contrabassoon, also known as the double bassoon, is a larger version of the bassoon, sounding an octave lower. Its technique is similar to its smaller cousin, with a few notable differences.

Differences from the bassoon

The reed is cons ...

, four horns, three trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standar ...

s, three trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the air column inside the instrument to vibrat ...

s, tuba

The tuba (; ) is the lowest-pitched musical instrument in the brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, the sound is produced by lip vibrationa buzzinto a mouthpiece (brass), mouthpiece. It first appeared in the mid-19th&n ...

, timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditiona ...

plus three percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a beater including attached or enclosed beaters or rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or struck against another similar instrument. Exc ...

parts, harp, organ, and strings. Elgar called for an additional harp if possible, plus three additional trumpets (and any available percussionists) to reinforce the climax in Part II, just before Gerontius's vision of God.

Form

Each of the two parts is divided into distinct sections, but differs from the traditional oratorio in that the music continues without significant breaks. Elgar did not call the work an oratorio, and disapproved when other people used the term for it. Part I is approximately 35 minutes long and Part II is approximately 60 minutes. Part I: # Prelude # Jesu, Maria – I am near to death # Rouse thee, my fainting soul # Sanctus fortis, sanctus Deus # Proficiscere, anima Christiana Part II: # I went to sleep # It is a member of that family # But hark! upon my sense comes a fierce hubbub # I see not those false spirits # But hark! a grand mysterious harmony # Thy judgment now is near # I go before my judge # Softly and gently, dearly-ransomed soulPart I

The work begins with an orchestral prelude, which presents the most important motifs. In a detailed analysis, Elgar's friend and editor August Jaeger identified and named these themes, in line with their functions in the work. Gerontius sings a prayer, knowing that life is leaving him and giving voice to his fear, and asks for his friends to pray with him. For much of the soloist's music, Elgar writes in a style that switches between exactly notated, fully accompanied recitative, and arioso phrases, lightly accompanied. The chorus adds devotional texts in four-partfugal

In music, a fugue () is a contrapuntal compositional technique in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation (repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the c ...

writing. Gerontius's next utterance is a full-blown aria ''Sanctus fortis'', a long '' credo'' that eventually returns to expressions of pain and fear. Again, in a mixture of conventional chorus and recitative, the friends intercede for him. Gerontius, at peace, submits, and the priest recites the blessing "Go forth upon thy journey, Christian soul!" (a translation of the litany ''Ordo Commendationis Animae''). This leads to a long chorus for the combined forces, ending Part I.Grove; Jenkins, Lyndon (1987), notes to EMI CD CMS 7 63185 2; and Moore, Jerrold Northrop (1975), notes to Testament CD SBT 2025

Part II

In a complete change of mood, Part II begins with a simple four-note phrase for theviola

; german: Bratsche

, alt=Viola shown from the front and the side

, image=Bratsche.jpg

, caption=

, background=string

, hornbostel_sachs=321.322-71

, hornbostel_sachs_desc=Composite chordophone sounded by a bow

, range=

, related=

*Violin family ...

s which introduces a gentle, rocking theme for the strings. This section is in triple time, as is much of the second part. The Soul's music expresses wonder at its new surroundings, and when the Angel is heard, he expresses quiet exultation at the climax of his task. They converse in an extended duet, again combining recitative with pure sung sections. Increasingly busy music heralds the appearance of the demons: fallen angel

In the Abrahamic religions, fallen angels are angels who were expelled from heaven. The literal term "fallen angel" never appears in any Abrahamic religious texts, but is used to describe angels cast out of heaven"Mehdi Azaiez, Gabriel Said ...

s who express intense disdain of men, mere mortals by whom they were supplanted. Initially the men of the chorus sing short phrases in close harmony, but as their rage grows more intense the music shifts to a busy fugue, punctuated by shouts of derisive laughter.

Gerontius cannot see the demons, and asks if he will soon see his God. In a barely accompanied recitative that recalls the very opening of the work, the Angel warns him that the experience will be almost unbearable, and in veiled terms describes the stigmata of St. Francis. Angels can be heard, offering praises over and over again. The intensity gradually grows, and eventually the full chorus gives voice to a setting of the section that begins with ''Praise to the Holiest in the Height''. After a brief orchestral passage, the Soul hears echoes from the friends he left behind on earth, still praying for him. He encounters the Angel of the Agony, whose intercession is set as an impassioned aria for bass. The Soul's Angel, knowing the long-awaited moment has come, sings an Alleluia.

The Soul now goes before God and, in a huge orchestral outburst, is judged in an instant. At this point in the score, Elgar instructs "for one moment, must every instrument exert its fullest force." This was not originally in Elgar's design, but was inserted at the insistence of Jaeger, and remains as a testament to the positive musical influence of his critical friendship with Elgar. In an anguished aria, the Soul then pleads to be taken away. A chorus of souls sings the first lines of Psalm 90 ("Lord, thou hast been our refuge") and, at last, Gerontius joins them in Purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgat ...

. The final section combines the Angel, chorus, and semichorus in a prolonged song of farewell, and the work ends with overlapping Amens.

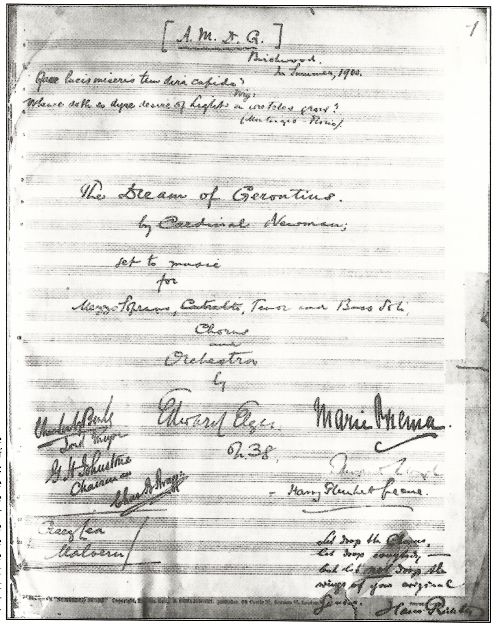

Dedication and superscription

Elgar dedicated his work "A.M.D.G." ('' Ad maiorem Dei gloriam'', "To the greater glory of God", the motto of theSociety of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

or ''Jesuits''), following the practice of Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wo ...

, who would dedicate his works "S.D.G." ('' Soli Deo gloria'', "Glory to God alone").Moore, p. 317 Underneath this he wrote a line from Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

: "Quae lucis miseris tam dira cupido?" together with Florio's English translation of Montaigne's adaptation of Virgil's line: "Whence so dyre desire of Light on wretches grow?"

At the end of the manuscript score, Elgar wrote this quotation from John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and po ...

's ''Sesame and Lilies'':

:This is the best of me; for the rest, I ate, and drank, and slept, loved and hated, like another: my life was as the vapour and is not; but ''this'' I saw and knew; this, if anything of mine, is worth your memory. McVeagh, Diana"Elgar, Sir Edward."

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed 21 October 2010. Richter signed the autograph copy of the score with the inscription: "Let drop the Chorus, let drop everybody—but let not drop the wings of your original genius."''

The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainze ...

'', 1 November 1900, p. 734

Recordings

Henry Wood made acoustic recordings of four extracts from ''The Dream of Gerontius'' as early as 1916, with Clara Butt as the Angel. Edison Bell issued the work in 1924 with Elgar's tacit approval (despite his contract with HMV); acoustically recorded and abridged, it was swiftly rendered obsolete by the introduction of the electrical process, and soon after withdrawn. HMV issued live recorded excerpts from two public performances conducted by Elgar in 1927, with the soloistsMargaret Balfour

Margaret Balfour (1889 – January 1961) was an English classical contralto of the 1920s and 1930s. She is best remembered as the angel in Elgar's own recorded excerpts of ''The Dream of Gerontius'' (1927) and one of the 16 soloists in the ...

, Steuart Wilson, Tudor Davies, Herbert Heyner, and Horace Stevens

Horace Ernest Stevens (26 October 187618 November 1950) was an Australian bass-baritone opera singer, army officer during the First World War, singing teacher, and sculler.

Early life and career

Stevens was born on 26 October 1876 in Prahran, ...

. Private recordings from radio broadcasts ("off-air" recordings) also exist in fragmentary form from the 1930s.

The first complete recording was made by EMI in 1945, conducted by Malcolm Sargent with his regular chorus and orchestra, the Huddersfield Choral Society and the Liverpool Philharmonic

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic is a music organisation based in Liverpool, England, that manages a professional symphony orchestra, a concert venue, and extensive programmes of learning through music. Its orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmo ...

. The soloists were Heddle Nash, Gladys Ripley, Dennis Noble

Dennis Noble (25 September 189814 March 1966) was a noted British baritone and teacher. He appeared in opera, oratorio, musical comedy and song, from the First World War through to the late 1950s. He was renowned for his enunciation and di ...

and Norman Walker. This is the only recording to date that employs different singers for the Priest and the Angel of the Agony. The first stereophonic recording was made by EMI in 1964, conducted by Sir John Barbirolli. It has remained in the catalogues continuously since its first release, and is notable for Janet Baker's singing as the Angel. Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

's 1971 recording for Decca was noted for its fidelity to Elgar's score, showing, as the '' Gramophone'' reviewer said, that "following the composer's instructions strengthens the music's dramatic impact". Of the other dozen or so recordings on disc, most are directed by British conductors, with the exception of a 1960 recording in German under Hans Swarowsky and a Russian recording (sung in English by British forces) under Yevgeny Svetlanov

Yevgeny Fyodorovich Svetlanov (russian: Евгéний Фёдорович Светлáнов; 6 September 1928 – 3 May 2002) was a Russian conductor, composer and a pianist.

Life and work

Svetlanov was born in Moscow and studied conducting wi ...

performed 'live' in Moscow in 1983. Another Russian conductor, Vladimir Ashkenazy

Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazy (russian: Влади́мир Дави́дович Ашкена́зи, ''Vladimir Davidovich Ashkenazi''; born 6 July 1937) is an internationally recognized solo pianist, chamber music performer, and conductor. He i ...

, performed the work with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and its choral and vocal soloists in 2008 and this too has been released on CD.

The BBC Radio 3

BBC Radio 3 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. It replaced the BBC Third Programme in 1967 and broadcasts classical music and opera, with jazz, world music, drama, culture and the arts also featuring. The st ...

feature "Building a Library" has presented comparative reviews of all available versions of ''The Dream of Gerontius'' on three occasions. Comparative reviews also appear in '' The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music'', 2008, and ''Gramophone'', February 2003. The recordings recommended by all three are Sargent's 1945 EMI version and Barbirolli's 1964 EMI recording.

Arrangements

Prelude to ''The Dream of Gerontius'', arranged by John Morrison for symphonic wind band, publisher Molenaar Edition. Taking his cue from Wagner's ''Prelude and Liebestod'', Elgar himself made an arrangement entitled ''Prelude and Angel's Farewell'' subtitled "for orchestra alone" which was published in 1902 by Novello. In 1917 he recorded a drastically abridged version of this transcription on a single-sided acoustic 78rpm disc.In popular culture

The work features as a key plot point in the 1974 BBC ''Play for Today

''Play for Today'' is a British television anthology drama series, produced by the BBC and transmitted on BBC1 from 1970 to 1984. During the run, more than three hundred programmes, featuring original television plays, and adaptations of stag ...

'' by David Rudkin, '' Penda's Fen''.

See also

*Notes

Sources

* * * * *Further reading

The Best of Me – A Gerontius Companion

* * * * *

External links

The Elgar Birthplace Museum

''The Dream of Gerontius'' on CD

*

(Note: Elgar used about half the poem in his libretto.)

* ttp://www.elgar.org/3gerontt.htm Elgar – His Music : ''The Dream of Gerontius'' – A Musical Analysis– first of a set of six pages on the work

A comparative review of the available recordings, at least up to 1997

''The Dream of Gerontius'' (1899–1900), analysis

an

synopsis

BBC {{DEFAULTSORT:Dream Of Gerontius, The Music based on poems Compositions by Edward Elgar Oratorios 1900 compositions Music for orchestra and organ Death in music