Tenedos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish, is an island of  Tenedos is mentioned in both the ''

Tenedos is mentioned in both the ''

The island is known in English as both Tenedos (the Greek name) and Bozcaada (the Turkish name). Over the centuries many other names have been used. Documented

The island is known in English as both Tenedos (the Greek name) and Bozcaada (the Turkish name). Over the centuries many other names have been used. Documented

Tenedos is roughly triangular in shape. Its area is . It is the third largest Turkish island after

Tenedos is roughly triangular in shape. Its area is . It is the third largest Turkish island after

Ancient Tenedos is referred to in Greek and Roman mythology, and archaeologists have uncovered evidence of its settlement from the Bronze Age. It would stay prominent through the age of classical Greece, fading by the time of the dominance of

Ancient Tenedos is referred to in Greek and Roman mythology, and archaeologists have uncovered evidence of its settlement from the Bronze Age. It would stay prominent through the age of classical Greece, fading by the time of the dominance of

Tenedos was occupied by

Tenedos was occupied by  In March 1657, an Ottoman Armada emerged through the Dardanelles, slipping through a Venetian blockade, with the objective of retaking the island but did not attempt to do so, concerned by the Venetian fleet. In July 1657, Köprülü made a decision to break the Venetian blockade and retake the territory. The Peace Party in the Venetian senate thought it best to not defend Tenedos, and Lemnos, and debated this with the War Party. Köprülü ended the argument by recapturing Tenedos on 31 August 1657, in the Battle of the Dardanelles (1657), the fourth and final one.

In March 1657, an Ottoman Armada emerged through the Dardanelles, slipping through a Venetian blockade, with the objective of retaking the island but did not attempt to do so, concerned by the Venetian fleet. In July 1657, Köprülü made a decision to break the Venetian blockade and retake the territory. The Peace Party in the Venetian senate thought it best to not defend Tenedos, and Lemnos, and debated this with the War Party. Köprülü ended the argument by recapturing Tenedos on 31 August 1657, in the Battle of the Dardanelles (1657), the fourth and final one.

Following the victory, the Grand Vizier visited the island and oversaw its repairs, during which he funded construction of a mosque, which was to be called by his name. According to the Mosque's Foundation's book, it was built on the site of an older mosque, called Mıhçı Mosque which was destroyed during Venetian occupation. By the time Köprülü died in September 1661, he had built on the island the businesses of a coffee-house, a bakery, 84 shops, and nine mills; a watermill; two mosques; a school; a rest stop for travelers and a stable; and a bath-house.

Rabbits which drew the attention of Tafur two-and-a-half centuries ago were apparently still abundant in the mid 17th century. In 1659 the traveler

Following the victory, the Grand Vizier visited the island and oversaw its repairs, during which he funded construction of a mosque, which was to be called by his name. According to the Mosque's Foundation's book, it was built on the site of an older mosque, called Mıhçı Mosque which was destroyed during Venetian occupation. By the time Köprülü died in September 1661, he had built on the island the businesses of a coffee-house, a bakery, 84 shops, and nine mills; a watermill; two mosques; a school; a rest stop for travelers and a stable; and a bath-house.

Rabbits which drew the attention of Tafur two-and-a-half centuries ago were apparently still abundant in the mid 17th century. In 1659 the traveler

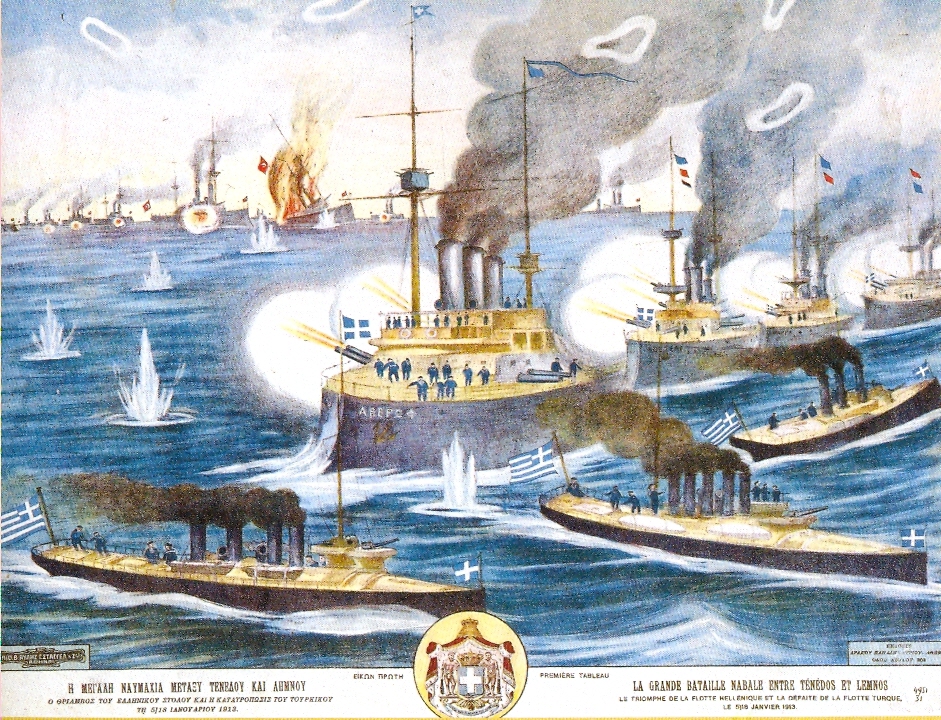

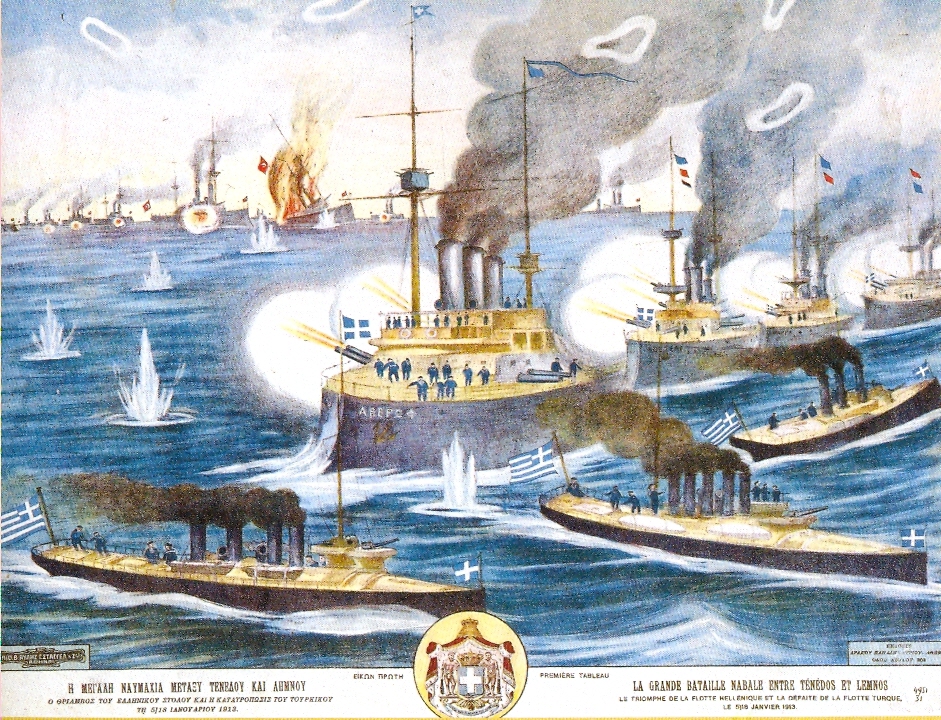

During the

During the

/ref>

/ref> The Greco-Turkish rapprochement of 1930, which marks a significant turning point in the relations of the two countries, helped Tenedos reap some benefits too. In September 1933, moreover, certain islanders who had emigrated to America were allowed to return to and settle in their native land. Responding to the Greek good will over the straits, Turkey permitted the regular election of a local Greek mayor and seven village elders as well as a number of local employees. In the 1950s, tension between Greece and Turkey eased and law 1151/1927 was abolished and replaced by law no. 5713 in 1951, according to the law regular Greek language classes were added to the curriculum of the schools on Tenedos. Also, as restriction of travel to the island was relaxed, a growing number of Greek tourists from Istanbul and abroad visited Tenedos. These tourists did not only bring much needed additional revenues, but they also put an end to the twenty-seven-year long isolation of the islands from the outside world. However, when tensions increased in 1963 over

/ref> In recent years there has been some progress in the relations between the different religious groups on the islands. In 2005, a joint Greek and Turkish delegation visited Tenedos and later that year Turkish Prime Minister

In 1854, there were some 4,000 inhabitants on the island of Bozcaada, of which one-third were Turks.

According to the Ottoman general census of 1893, the population of the island was divided as follows: 2,479 Greeks, 1,247 Turks, 103 Foreign Nationals and 6 Armenians.

In 1912, when the

In 1854, there were some 4,000 inhabitants on the island of Bozcaada, of which one-third were Turks.

According to the Ottoman general census of 1893, the population of the island was divided as follows: 2,479 Greeks, 1,247 Turks, 103 Foreign Nationals and 6 Armenians.

In 1912, when the

Traditional economic activities are fishing and wine production. The remainder of arable land is covered by olive trees and wheat fields. Most of the agriculture is done on the central plains and gentle hills of the island. Red poppies of the island are used to produce small quantities of sharbat and jam. Sheep and goats are grazed at hilly northeastern and southeastern part of the island which is not suitable for agriculture. The number of farmers involved in grape cultivation has gone up from 210 to 397 in the recent years, though the farm area has gone down from to .

Tourism has been an important, but limited, economic activity since the 1970s but it developed rapidly from the 1990s onwards. The island's main attraction is the castle last rebuilt in 1815, illuminated at night, and with a view out to the open sea. The island's past is captured in a small museum, with a room dedicated to its Greek story. The town square boasts a "morning market" where fresh groceries and seafood are sold, along with the island's specialty of tomato jam. Mainlanders from Istanbul run some bars, boutiques and guesthouses. In 2010, the island was named the world's second most-beautiful island by

Traditional economic activities are fishing and wine production. The remainder of arable land is covered by olive trees and wheat fields. Most of the agriculture is done on the central plains and gentle hills of the island. Red poppies of the island are used to produce small quantities of sharbat and jam. Sheep and goats are grazed at hilly northeastern and southeastern part of the island which is not suitable for agriculture. The number of farmers involved in grape cultivation has gone up from 210 to 397 in the recent years, though the farm area has gone down from to .

Tourism has been an important, but limited, economic activity since the 1970s but it developed rapidly from the 1990s onwards. The island's main attraction is the castle last rebuilt in 1815, illuminated at night, and with a view out to the open sea. The island's past is captured in a small museum, with a room dedicated to its Greek story. The town square boasts a "morning market" where fresh groceries and seafood are sold, along with the island's specialty of tomato jam. Mainlanders from Istanbul run some bars, boutiques and guesthouses. In 2010, the island was named the world's second most-beautiful island by  Fishing plays a role in the island's economy, but similar to other Aegean islands, agriculture is a more significant economic activity. The local fishing industry is small, with the port authority counting 48 boats and 120 fishermen in 2011. Local fishing is year-round and seafood can be obtained in all seasons. The fish population has gone down over the years, resulting in a shrinking fishing industry, though increase in tourism and consequent demand for more seafood has benefited the industry. The sea off the island is one of the major routes by which fish in the Aegean sea migrate seasonally. During the migration period, boats from the outside come to the island for fishing.

Fishing plays a role in the island's economy, but similar to other Aegean islands, agriculture is a more significant economic activity. The local fishing industry is small, with the port authority counting 48 boats and 120 fishermen in 2011. Local fishing is year-round and seafood can be obtained in all seasons. The fish population has gone down over the years, resulting in a shrinking fishing industry, though increase in tourism and consequent demand for more seafood has benefited the industry. The sea off the island is one of the major routes by which fish in the Aegean sea migrate seasonally. During the migration period, boats from the outside come to the island for fishing.

In 2000, a

In 2000, a

The island is windy throughout the year and this makes the climate dry and warm enough to grow grapes. In classical antiquity wine production was linked with the cult of

The island is windy throughout the year and this makes the climate dry and warm enough to grow grapes. In classical antiquity wine production was linked with the cult of

Pindar, Nemean Odes, 11, For Aristagoras of Tenedos on his election to the presidency of the senate

/ref>

Bozcaada, An Island for Those who Love the Aegean

* Hakan Gürüney: From Tenedos to Bozcaada. Tale of a forgotten island. In: Tenedos Local History Research Centre. No. 5, Bozcaada 2012, . * Haluk Şahin, The Bozcaada Book: A Personal, historical and literary guide to the windy island also known as Tenedos, Translated by Ayşe Şahin, Troya Publishing, 2005

Papers

presented to the II. National Symposium on the Aegean Islands, 2–3 July 2004, Gökçeada, Çanakkale. *

Bozcaada government website

(Turkish)

Bozcaada Blog website

(Turkish)

Bozcaada Museum (private)

(Turkish)

*

Bozcaada GuideUne fin de semaine sur l'ile de Bozcaada

(slide show)

Website, Municipality of Bozcaada

(Turkish) {{Authority control History of Turkey Islands of Turkey Ancient Greek archaeological sites in Turkey North Aegean islands Locations in the Iliad Tenea Fishing communities in Turkey Bozcaada district Islands of Çanakkale Province Members of the Delian League Populated places in the ancient Aegean islands Populated places in ancient Troad Greek city-states

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans an ...

. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Province

Çanakkale Province ( tr, ) is a province of Turkey, located in the northwestern part of the country. It takes its name from the city of Çanakkale.

Like Istanbul, Çanakkale province has a European (Thrace) and an Asian (Anatolia) part. The E ...

. With an area of it is the third largest Turkish island after Imbros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

(Gökçeada) and Marmara. In 2018, the district had a population of 3023. The main industries are tourism, wine production and fishing. The island has been famous for its grapes, wines and red poppies for centuries. It is a former bishopric and presently a Latin Catholic titular see.

Tenedos is mentioned in both the ''

Tenedos is mentioned in both the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' and the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'', in the latter as the site where the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, Albania, Greeks in Italy, ...

hid their fleet near the end of the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ha ...

in order to trick the Trojans

Trojan or Trojans may refer to:

* Of or from the ancient city of Troy

* Trojan language, the language of the historical Trojans

Arts and entertainment Music

* ''Les Troyens'' ('The Trojans'), an opera by Berlioz, premiered part 1863, part 189 ...

into believing the war was over and into taking the Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'', with the poem ending before the war is concluded, ...

within their city walls. The island was important throughout classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

despite its small size due to its strategic location at the entrance of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. In the following centuries, the island came under the control of a succession of regional powers, including the Achaemenid Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest emp ...

, the Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pl ...

, the empire of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, the Kingdom of Pergamon

The Kingdom of Pergamon or Attalid kingdom was a Greek state during the Hellenistic period that ruled much of the Western part of Asia Minor from its capital city of Pergamon. It was ruled by the Attalid dynasty (; grc-x-koine, Δυναστ� ...

, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

and its successor, the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

, before passing to the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

. As a result of the War of Chioggia

The War of Chioggia ( it, Guerra di Chioggia) was a conflict between Genoa and Venice which lasted from 1378 to 1381, from which Venice emerged triumphant. It was a part of the Venetian-Genoese Wars.

The war had mixed results. Venice and her alli ...

(1381) between Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of t ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

the entire population was evacuated and the town was demolished. The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

established control over the deserted island in 1455. During Ottoman rule, it was resettled by both Greeks and Turks. In 1807, the island was temporarily occupied by the Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

. During this invasion the town was burnt down and many Turkish residents left the island.

Under Greek administration between 1912 and 1923, Tenedos was ceded to Turkey with the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conf ...

(1923) which ended the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) began with the Young Turk Revolution which restored the constitution of 1876 and brought in multi-party politics with a two-stage electoral system for the Ottoman parliament. At the same ti ...

in the aftermath of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The treaty called for a quasi-autonomous administration to accommodate the local Greek population and excluded the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, Albania, Greeks in Italy, ...

on the two islands of Imbros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

and Tenedos from the wider population exchanges that took place between Greece and Turkey. Tenedos remained majority Greek until the late 1960s and early 1970s, when many Greeks emigrated because of systemic discrimination and better opportunities elsewhere. Starting with the second half of the 20th century, there has been immigration from mainland Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

, especially Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

from the town of Bayramiç

Bayramiç is a town and district of Çanakkale Province in the Marmara Region, Marmara region of Turkey. According to the 2000 census, population of the district is 32,314 of which 13,420 live in the town of Bayramiç. The district covers an area ...

.

Name

The island is known in English as both Tenedos (the Greek name) and Bozcaada (the Turkish name). Over the centuries many other names have been used. Documented

The island is known in English as both Tenedos (the Greek name) and Bozcaada (the Turkish name). Over the centuries many other names have been used. Documented ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

names for the island are Leukophrys, Calydna, Phoenice and Lyrnessus (Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, ...

, HN 5,140). The official Turkish name for the island is Bozcaada; the Turkish word "boz" means either a barren land or grey to brown color (sources indicate both of these meanings may have been associated with the island) and "ada" meaning island. The name Tenedos was derived, according to Apollodorus of Athens

Apollodorus of Athens ( el, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος, ''Apollodoros ho Athenaios''; c. 180 BC – after 120 BC) son of Asclepiades Pharmacion, Asclepiades, was a Greeks, Greek scholar, historian, and grammarian. He was a pup ...

, from the Greek hero

Hero cults were one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion. In Homeric Greek, " hero" (, ) refers to the mortal offspring of a human and a god. By the historical period, however, the word came to mean specifically a ''dead'' ...

Tenes

In Greek mythology, Tenes or Tennes (Ancient Greek: Τέννης) was the eponymous hero of the island of Tenedos.

Family

Tenes was the son either of Apollo or of King Cycnus of Colonae by Proclia, daughter or granddaughter of Laomedon.

M ...

, who ruled the island at the time of the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ha ...

and was killed by Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's '' Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Pe ...

. Apollodorus writes that the island was originally known as Leocophrys until Tenes landed on the island and became the ruler. The island became known as Bozcaada when the Ottoman Empire took the island over. Tenedos remained a common name for the island along with Bozcaada after the Ottoman conquest of the island, often with Greek populations and Turkish populations using different names for the island.

Geography and climate

Tenedos is roughly triangular in shape. Its area is . It is the third largest Turkish island after

Tenedos is roughly triangular in shape. Its area is . It is the third largest Turkish island after Marmara Island

Marmara Island ( ) is a Turkish island in the Sea of Marmara. With an area of it is the largest island in the Sea of Marmara and is the second largest island of Turkey after Gökçeada (older name in Turkish: ; el, Ίμβρος, links=no ''I ...

and Imbros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

(Gökçeada). It is surrounded by small islets, and is situated close to the entrance of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

. It is the only rural district (''ilçe

The 81 provinces of Turkey are divided into 973 districts (''ilçeler''; sing. ''ilçe''). In the early Turkish Republic and in the Ottoman Empire, the corresponding unit was the ''kaza''.

Most provinces bear the same name as their respectiv ...

'') of Turkey without any villages, and has only one major settlement, the town center.

Geological evidence suggests that the island broke away from the mainland producing a terrain that is mainly plains in the west with hills in the Northeast, and the highest point is . The central part of the island is the most amenable to agricultural activities. There is a small pine forest in the Southwestern part of the island. The westernmost part of the island has large sandy areas not suitable for agriculture.

The island has a Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate (also called a dry summer temperate climate ''Cs'') is a temperate climate sub-type, generally characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, fairly wet winters; these weather conditions are typically experienced in the ...

with strong northern winds called etesian

The etesians ( or ; grc, ἐτησίαι, etēsiai, periodic winds; sometimes found in the Latin form etesiae), ''meltemia'' ( el, ετησίες,μελτέμια; pl. of meltemi), or meltem (Turkish) are the strong, dry north winds of the Aegean ...

s. Average temperature is and average annual precipitation is . There are a number of small streams running from north to south at the southwestern part of the island. Freshwater sources though are not enough for the island so water is piped in from the mainland.

History

Prehistory

Archeological findings indicate that the first human settlement on the island dates back to theEarly Bronze Age II

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, M ...

(ca. 3000–2700 BC). Archaeological evidence suggests the culture on the island had elements in common with the cultures of northwestern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

and the Cycladic Islands

The Cyclades (; el, Κυκλάδες, ) are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The nam ...

. Most settlement was on the small bays on the east side of the island which formed natural harbours. Settlement archaeological work was done quickly and thus did not find definitive evidence of grape cultivation on the island during this period. However, grape cultivation was common on neighboring islands and the nearby mainland during this time.

According to a reconstruction, based on the myth of Tenes, Walter Leaf

Sir Walter Leaf (26 November 1852, Upper Norwood – 8 March 1927, Torquay) was an English banker, classical scholar and psychical researcher. He published a benchmark edition of Homer's Iliad and was a director of Westminster Bank for many ye ...

stated that the first inhabitants of the island could be Pelasgians

The name Pelasgians ( grc, Πελασγοί, ''Pelasgoí'', singular: Πελασγός, ''Pelasgós'') was used by classical Greek writers to refer either to the predecessors of the Greeks, or to all the inhabitants of Greece before the emergen ...

, who were driven out of the Anatolian mainland by the Phrygians

The Phrygians (Greek: Φρύγες, ''Phruges'' or ''Phryges'') were an ancient Indo-European speaking people, who inhabited central-western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) in antiquity. They were related to the Greeks.

Ancient Greek authors used ...

. According to the same author, there are possible traces of Minoan

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from 3500BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000BC, and then declining from 1450BC ...

and Mycenaean Greek

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language, on the Greek mainland and Crete in Mycenaean Greece (16th to 12th centuries BC), before the hypothesised Dorian invasion, often cited as the '' terminus ad quem'' for the ...

influence in the island.

Antiquity

ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–50 ...

. Although a small island, Tenedos's position in the straits and its two harbors made it important to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

powers over the centuries. For nine months of the year, the currents and the prevailing wind, the etesian

The etesians ( or ; grc, ἐτησίαι, etēsiai, periodic winds; sometimes found in the Latin form etesiae), ''meltemia'' ( el, ετησίες,μελτέμια; pl. of meltemi), or meltem (Turkish) are the strong, dry north winds of the Aegean ...

, came, and still come, from the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, ...

hampering sailing vessels headed for Constantinople. They had to wait a week or more at Tenedos, waiting for the favorable southerly wind. Tenedos thus served as a shelter and way station for ships bound for the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont ( ...

, Propontis

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

, Bosphorus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

, and places farther on. Several of the regional powers captured or attacked the island, including the Athenians

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, the Persians, the Macedonians under Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

and the Attalids

The Kingdom of Pergamon or Attalid kingdom was a Greek state during the Hellenistic period that ruled much of the Western part of Asia Minor from its capital city of Pergamon. It was ruled by the Attalid dynasty (; grc-x-koine, Δυναστε ...

.

Mythology

Homer mentionsApollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

as the chief deity of Tenedos in his time. According to him, the island was captured by Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's '' Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Pe ...

during the siege of Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Çan ...

. Nestor

Nestor may refer to:

* Nestor (mythology), King of Pylos in Greek mythology

Arts and entertainment

* "Nestor" (''Ulysses'' episode) an episode in James Joyce's novel ''Ulysses''

* Nestor Studios, first-ever motion picture studio in Hollywood, L ...

obtained his slave Hecamede

In the ''Iliad'', Hecamede (Ancient Greek: Ἑκαμήδη), daughter of Arsinoos, was captured from the isle of Tenedos and given as captive to King Nestor. Described as "skilled as a goddess", "fair" and "proud", Hecamede was not a concubine ...

there during one of Achilles's raids. Nestor also sailed back from Troy stopping at Tenedos and island-hopping to Lesbos. ''The Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'' mentions the Greeks leaving Troy after winning the war first traveled to nearby Tenedos, sacrificed there, and then went to Lesbos before pausing to choose between alternative routes.

Homer, in the Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

mention that between Tenedos and Imbros

Imbros or İmroz Adası, officially Gökçeada (lit. ''Heavenly Island'') since 29 July 1970,Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities in Greece And Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), ''Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1 ...

there was a wide cavern, in which Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

stayed his horses.

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

, in the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'', described the Achaeans hiding their fleet at the bay of Tenedos, toward the end of the Trojan War, to trick Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Çan ...

into believing the war was over and allowing them to take the Trojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'', with the poem ending before the war is concluded, ...

within Troy's city walls. In ''Aeneid'', it is also the island from which twin serpents came to kill the Trojan priest Laocoön

Laocoön (; grc, , Laokóōn, , gen.: ), is a figure in Greek and Roman mythology and the Epic Cycle. Laocoon was a Trojan priest. He and his two young sons were attacked by giant serpents, sent by the gods. The story of Laocoön has been the s ...

and his sons as punishment for throwing a spear at the Trojan Horse. According to Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

(Nemean Odes no. 11), the island was founded after the war by bronze-clad warriors from Amyklai, traveling with Orestes

In Greek mythology, Orestes or Orestis (; grc-gre, Ὀρέστης ) was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and the brother of Electra. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness and ...

.

According to myth, Tenes

In Greek mythology, Tenes or Tennes (Ancient Greek: Τέννης) was the eponymous hero of the island of Tenedos.

Family

Tenes was the son either of Apollo or of King Cycnus of Colonae by Proclia, daughter or granddaughter of Laomedon.

M ...

was the son of Cycnus :''The butterfly genus ''Cycnus'' is now synonymized with '' Panthiades.

In Greek mythology, multiple characters were known as Cycnus (Ancient Greek: Κύκνος) or Cygnus. The literal meaning of the name is "swan", and accordingly most of them en ...

, himself the son of Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

and Calyce. Philonome, Cycnus's second wife and hence Tenes's stepmother, tried to seduce Tenes and was rejected. She then accused him of rape leading to his abandonment at sea along with his sister. They washed up on the island of Leucophrys where he was proclaimed king and the island renamed Tenedos in his honor. When Cycnus realized the lie behind the allegations he took a ship to apologize to his son. The myths differ on whether they reconciled. According to one version, when the father landed on the island of Tenedos, Tenes cut the cord holding his boat. The phrase 'hatchet of Tenes' came to mean resentment that could not be soothed. Another myth had Achilles landing on Tenedos, while sailing from Aulis to Troy. There his navy stormed the island, and Achilles fought Tenes, in this myth a son of Apollo, and killed him, not knowing Tenes's lineage and hence unaware of the danger of Apollo's revenge. Achilles would also later kill Tenes's father, Cycnus, at Troy. In Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

's ''Philoctetes

Philoctetes ( grc, Φιλοκτήτης ''Philoktētēs''; English pronunciation: , stressed on the third syllable, ''-tet-''), or Philocthetes, according to Greek mythology, was the son of Poeas, king of Meliboea in Thessaly, and Demonassa o ...

'', written in 409 BC, a serpent bit Philoctetes in the foot at Tenedos. According to Hyginus

Gaius Julius Hyginus (; 64 BC – AD 17) was a Latin author, a pupil of the scholar Alexander Polyhistor, and a freedman of Caesar Augustus. He was elected superintendent of the Palatine library by Augustus according to Suetonius' ''De Gramma ...

, the goddess Hera

In ancient Greek religion, Hera (; grc-gre, Ἥρα, Hḗrā; grc, Ἥρη, Hḗrē, label=none in Ionic and Homeric Greek) is the goddess of marriage, women and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she ...

, upset with Philoctetes for helping Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted th ...

, had sent the snake to punish him. His wound refused to heal, and the Greeks abandoned him, before going back to him for help later during the attack on Troy. Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of t ...

quoted Nymphodorus's remarks on the beauty of the women of Tenedos.

Callimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variet ...

talked of a myth in which Ino's son Melikertes washed up dead in Tenedos after being thrown into the sea by his mother, who killed herself too; the residents, Lelegians, built an altar for Melikertes and started a ritual of a woman sacrificing her infant child when the town's need was dire. The woman would then be blinded. The myths also added that the custom was abolished when Orestes' descendants settled the place.

Neoptolemus

In Greek mythology, Neoptolemus (; ), also called Pyrrhus (; ), was the son of the warrior Achilles and the princess Deidamia, and the brother of Oneiros. He became the mythical progenitor of the ruling dynasty of the Molossians of ancient Ep ...

stayed two days at Tenedos, following the advice of Thetis

Thetis (; grc-gre, Θέτις ), is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, or one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

When described as ...

, before he go to the land of the Molossians

The Molossians () were a group of ancient Greek tribes which inhabited the region of Epirus in classical antiquity. Together with the Chaonians and the Thesprotians, they formed the main tribal groupings of the northwestern Greek group. On t ...

together with Helenus

In Greek mythology, Helenus (; grc, Ἕλενος, ''Helenos'', la, Helenus) was a gentle and clever seer. He was also a Trojan prince as the son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, and the twin brother of the prophetess Cassandra. He wa ...

.

Archaic period

It was at Tenedos, along with Lesbos, that the first coins with Greek writing on them were minted. Figures of bunches of grapes and wine vessels such asamphorae

An amphora (; grc, ἀμφορεύς, ''amphoreús''; English plural: amphorae or amphoras) is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storag ...

and kantharoi

A ''kantharos'' ( grc, κάνθαρος) or cantharus is a type of ancient Greek cup used for drinking. Although almost all surviving examples are in Greek pottery, the shape, like many Greek vessel types, probably originates in metalwork. In i ...

were stamped on coins. The very first coins had a twin head of a male and a female on the obverse side. The early coins were of silver and had a double-headed axe imprinted on them. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

considered the axe as symbolizing the decapitation of those convicted of adultery, a Tenedian decree. The axe-head was either a religious symbol or the seal of a trade unit of currency. Apollo Smintheus, a god who both protected against and brought about plague, was worshipped in late Bronze Age Tenedos. Strabo's Geography writes that Tenedos "contains an Aeolian

Aeolian commonly refers to things related to either of two Greek mythological figures:

* Aeolus (son of Hippotes), ruler of the winds

* Aeolus (son of Hellen), son of Hellen and eponym of the Aeolians

* Aeolians, an ancient Greek tribe thought to ...

city and has two harbours, and a temple of Apollo Smintheus" ( Strabo's Geography, Vol. 13). The relationship between Tenedos and Apollo is mentioned in Book I of the Iliad where a priest calls to Apollo with the name "O god of the silver bow, that protectest Chryse and holy Cilla and rulest Tenedos with thy might"(''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' I).

During the later part of the Bronze Age and during the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

, the place served as a major point between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Homer's ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' mentions the Tenedos of this era. The culture and artisanship of the area, as represented by pottery and metal vessels recovered from graves, matched that of the northeastern Aegean. Archaeologists have found no evidence to substantiate Herodotus's assertion Aeolians had settled in Tenedos by the Bronze Age. Homer mentions Tenedos as a base for the Achaean fleet during the Trojan war.

The Iron Age settlement of the northeast Aegean was once attributed to Aeolians, descendants of Orestes

In Greek mythology, Orestes or Orestis (; grc-gre, Ὀρέστης ) was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and the brother of Electra. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness and ...

and hence of the House of Atreus in Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. ...

, from across the Aegean from Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

, Boiotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its la ...

and Akhaia

Achaea () or Achaia (), sometimes transliterated from Greek as Akhaia (, ''Akhaïa'' ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Western Greece and is situated in the northwestern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. The ...

, all in mainland Greece. Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

, in his 11th Nemean Ode, hints at a group of Peloponnesians, the children of the fighters at Troy, occupying Tenedos, with Orestes, the son of Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husb ...

, landing straight on the island; specifically he refers to a Spartan Peisandros and his descendant Aristagoras, with Peisandaros having come over with Orestes. Strabo places the start of the migration sixty years after the Trojan war, initiated by Orestes's son, Penthilos, with the colonization continuing onto Penthilos's grandson.

The archaeological record provides no supporting evidence for the theory of Aiolian occupation. During the pre-archaic period, adults in Lesbos were buried by placing them in large jars, and later clay coverings were used, similar to Western Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

. Still later, Tenedians began to both bury and cremate their adults in pits buttressed with stone along the walls. Children were still buried covered in jars. Some items buried with the person, such as pottery, gifts and safety-pin-like clasps, resemble what is found in Anatolia, in both style and drawings and pictures, more than they resemble burial items in mainland Greece.

While human, specifically infant, sacrifice has been mentioned in connection with Tenedos's ancient past, it is now considered mythical in nature. The hero Paleomon in Tenedos was worshipped by a cult in that island, and the sacrifices were attributed to the cult. At Tenedos, people did sacrifice a newborn calf dressed in buskins

A buskin is a knee- or calf-length boot made of leather or cloth, enclosed by material, and laced, from above the toes to the top of the boot, and open across the toes. A high-heeled version was worn by Athenian tragic actors (to make them lo ...

, after treating the cow like a pregnant women giving birth; the person who killed the calf was then stoned and driven out into a life on the sea. According to Harold Willoughby, a belief in the calf as a ritual incarnation of God drove this practice.

Classical period

From the Archaic to Classical period, the archaeological evidence of well-stocked graves establishes Tenedos's continuing affluence. Tall, broad-mouthed containers show grapes and olives were likely processed during this time. They were also used to bury dead infants. By the fourth century BC, grapes and wine had become relevant to the economy of the island. Tenedians likely exported surplus wine. Writings from this era talk of a shortage of agricultural land, indicating a booming settlement. A dispute with the neighboring island ofSigeum

Sigeion (Ancient Greek: , ''Sigeion''; Latin: ''Sigeum'') was an ancient Greek city in the north-west of the Troad region of Anatolia located at the mouth of the Scamander (the modern Karamenderes River). Sigeion commanded a ridge between the Aeg ...

was arbitrated by Periander of Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

, who handed over political control of a swath of the mainland to Tenedos. In the first century BC this territory was eventually incorporated into Alexandria Troas

Alexandria Troas ("Alexandria of the Troad"; el, Αλεξάνδρεια Τρωάς; tr, Eski Stambul) is the site of an ancient Greek city situated on the Aegean Sea near the northern tip of Turkey's western coast, the area known historically a ...

.

According to some accounts, Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regard ...

of Greece died in Tenedos. Cleostratus

Cleostratus ( el, Κλεόστρατος; b. c. 520 BC; d. possibly 432 BC) was an astronomer of ancient Greece. He was a native of Tenedos. He is believed by ancient historians to have introduced the zodiac (beginning with Aries and Sagittarius) ...

, an astronomer, lived and worked in Tenedos, though it is unknown whether he met Thales there. Cleostratus is one of the founders of Greek astronomy, influenced as it was by the reception of Babylonian knowledge. Athens had a naval base on the island in the fifth and fourth century BC. Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual pro ...

mentions Apollodorus, a trierarch commanding a ship, talking of buying food during a stopover at Tenedos where he would pass the trierarchy to Polycles. In 493 BCE, the Persians overran Tenedos along with other Greek islands. During his reign, Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the a ...

, father of Alexander the Great, sent a Macedonian force sailing against the Persian fleet. Along with other Aegean islands such as Lesbos, Tenedos also rebelled against the Persian dominance at this time. Athens seemingly augmented its naval base with a fleet at the island around 450 BC.

During the campaign of Alexander the Great against the Persians, Pharnabazus, the Persian commander, laid siege to Tenedos with a hundred ships and eventually captured it as Alexander could not send a fleet in time to save the island. The island's walls were demolished and the islanders had to accept the old treaty with the Persian emperor Artaxerxes II

Arses ( grc-gre, Ἄρσης; 445 – 359/8 BC), known by his regnal name Artaxerxes II ( peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 405/4 BC to 358 BC. He was the son and suc ...

: the Peace of Antalcidas. Later, Alexander's commander Hegelochus of Macedon

Hegelochus ( el, Ἡγέλοχος), son of Hippostratus, was a Macedonian general, and apparently the nephew of Philip II's last wife, Cleopatra. Hegelochus survived the disgrace of his relative, Attalus, who was murdered on Alexander the Great' ...

captured the island from the Persians. Alexander made an alliance with the people in Tenedos in order to limit the Persian naval power. He also took on board 3000 Greek mercenaries and oarsmen from Tenedos in his army and navy.

The land was not suitable for large-scale grazing or extensive agriculture. Local grapes and wines were mentioned in inscriptions and on coins. But Pliny and other contemporary writers did not mention grapes and wines at the island. Most exports were via sea, and both necessities and luxuries had to imported, again by sea. Unlike in Athens, it is unclear whether Tenedos ever had a democracy. Marjoram

Marjoram (; ''Origanum majorana'') is a cold-sensitive perennial herb or undershrub with sweet pine and citrus flavours. In some Middle Eastern countries, marjoram is synonymous with oregano, and there the names sweet marjoram and knotted mar ...

(Oregano) from Tenedos was one of the relishes used in Greek cuisine.

The Tenedians punished adulterers by cutting off their heads with an axe. Aristotle wrote about the social and political structure of Tenedos. He found it notable a large part of the populace worked in occupations related to ferries, possibly hundreds in a population of thousands. Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

* Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of ...

noted some common proverbs in Greek originated from customs of the Tenedians. "He is a man of Tenedos" was used to allude to a person of unquestionable integrity, and "to cut with the Tenedian axe" was a full and final 'no'. Lykophron, writing in the second century BC, referred to the deity Melikertes as the "baby-slayer". Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...

described the Spartans

Sparta (Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: wikt:Σπάρτη, Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the nam ...

' sacking the place in 389 BC, but being beaten back by an Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

fleet when trying again two years later.

In Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax

The ''Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax'' is an ancient Greek periplus (περίπλους ''períplous'', 'circumnavigation') describing the sea route around the Mediterranean and Black Sea. It probably dates from the mid-4th century BC, specifically ...

writes that the astronomer Kleostratos ( grc, Κλεόστρατος) was from Tenedos.

Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

In the Hellenistic period, the Egyptian goddess Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic language, Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician language, Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major ancient Egyptian deities, goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughou ...

was also worshipped at Tenedos. There she was associated closely with the sun, with her name and title reflecting that position.

Roman period

During the Roman occupation of Greece, Tenedos too came under their rule. The island became a part of the Roman Republic in 133 BC, whenAttalus III

Attalus III ( el, Ἄτταλος Γ΄) Philometor Euergetes ( – 133 BC) was the last Attalid king of Pergamon, ruling from 138 BC to 133 BC.

Biography

Attalus III was the son of king Eumenes II and his queen Stratonice of Pergamon, and h ...

, the king of Pergamon, died, leaving his territory to the Romans. The Romans constructed a new port at Alexandria Troas

Alexandria Troas ("Alexandria of the Troad"; el, Αλεξάνδρεια Τρωάς; tr, Eski Stambul) is the site of an ancient Greek city situated on the Aegean Sea near the northern tip of Turkey's western coast, the area known historically a ...

, on the Dardanelle Strait. This led to Tenedos's decline. Tenedos lost its importance during this period. Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

, in ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'', stated the harbour was deserted and ships could not moor in the bay during his time. Processing of grapes seems to have been abandoned. Olive cultivation and processing did possibly continue, though there was likely no surplus to export. Archaeological evidence indicates the settlement was mostly in the town, with only a few scattered sites in the countryside.

According to Strabo there was a kinship between the peoples of Tenedos and Tenea (a town at Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

).

According to Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

a number of deified human beings were worshipped in Greece: in Tenedos there was Tenes

In Greek mythology, Tenes or Tennes (Ancient Greek: Τέννης) was the eponymous hero of the island of Tenedos.

Family

Tenes was the son either of Apollo or of King Cycnus of Colonae by Proclia, daughter or granddaughter of Laomedon.

M ...

.

Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

* Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of ...

, mention at his work Description of Greece

Pausanias ( /pɔːˈseɪniəs/; grc-gre, Παυσανίας; c. 110 – c. 180) was a Greek traveler and geographer of the second century AD. He is famous for his ''Description of Greece'' (, ), a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece ...

that Periklyto, who was from Tenedos, has dedicated some axes at Delphoi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracle ...

.

During the Third Mithridatic War

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies dragging the entire east of th ...

, in around 73 BC, Tenedos was the site of a large naval battle between Roman commander Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and government service, he conquered the eastern kingd ...

and the fleet of the king of Pontus

This is a list of kings of Pontus, an ancient Hellenistic kingdom of Persian origin in Asia Minor.

Kings of Pontus

* Mithridates I Ktistes 281–266 BC

* Ariobarzanes 266 – c. 250 BC

* Mithridates II c. 250 – c. 220 BC

* Mithridates III c. ...

, Mithridates

Mithridates or Mithradates ( Old Persian 𐎷𐎡𐎰𐎼𐎭𐎠𐎫 ''Miθradāta'') is the Hellenistic form of an Iranian theophoric name, meaning "given by the Mithra". Its Modern Persian form is Mehrdad. It may refer to:

Rulers

*Of Cius (al ...

, commanded by Neoptolemus. This Battle of Tenedos was won decisively by the Romans. Around 81–75 BC, Verres

Gaius Verres (c. 120–43 BC) was a Roman magistrate, notorious for his misgovernment of Sicily. His extortion of local farmers and plundering of temples led to his prosecution by Cicero, whose accusations were so devastating that his defence adv ...

, legate of the Governor of Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian language, Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from th ...

, Gaius Dolabella, plundered the island, carrying off the statue of Tenes and some money. Towards 6 BC, geographical change made the mainland port less useful, and Tenedos became relevant again. According to Dio Chrysostom

Dio Chrysostom (; el, Δίων Χρυσόστομος ''Dion Chrysostomos''), Dion of Prusa or Cocceianus Dio (c. 40 – c. 115 AD), was a Greek orator, writer, philosopher and historian of the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD. Eighty of his ...

and Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

, Tenedos was famous for its pottery ca AD 100. Under Rome's protection, Tenedos restarted its mint after a break of more than a century. The mint continued with the old designs, improving on detail and precision. Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

, writing in this era, noted the temple built to honor Tenes, the founder whose name the island received, and of the harsh justice system of the populace.

Byzantine period

WhenConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

became a prominent city in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, from AD 350 on, Tenedos became a crucial trading post. Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

ordered the construction of a large granary on Tenedos and ferries between the island and Constantinople became a major activity on the island. Ships carrying grain from Egypt to Constantinople stopped at Tenedos when the sea was unfavorable. The countryside was likely not heavily populated or utilized. There were vineyards, orchards and corn fields, at times abandoned due to disputes.

The Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

placed the diocese of Tenedos under the metropolitanate of Mytilini during the ninth century, and promoted it to its own metropolitanate in early fourteenth century. By this time Tenedos was part of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

but its location made it a key target of the Venetians, the Genoese

Genoese may refer to:

* a person from Genoa

* Genoese dialect, a dialect of the Ligurian language

* Republic of Genoa (–1805), a former state in Liguria

See also

* Genovese, a surname

* Genovesi, a surname

*

*

*

*

* Genova (disambiguati ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The weakened Byzantine Empire and wars between Genoa and Venice for trade routes made Tenedos a key strategic location. In 1304, Andrea Morisco Andrea Morisco (in el, Ἀνδρέας Μουρίσκος, ''Andreas Mouriskos'') was a Genoese pirate active in the Aegean Sea in the late 13th century, who in 1304 entered the service of the Byzantine Empire. As an admiral and corsair, he was ac ...

, a Genoese adventurer, backed by a title from the Byzantine emperor Andronikos III, took over Tenedos. Later, sensing political tension in the Byzantine empire just before the Second Byzantine Civil War, the Venetians offered 20,000 ducats in 1350 to John V Palaiologos

John V Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Ἰωάννης Παλαιολόγος, ''Iōánnēs Palaiológos''; 18 June 1332 – 16 February 1391) was Byzantine emperor from 1341 to 1391, with interruptions.

Biography

John V was the son of E ...

for control of Tenedos. When John V was captured in the Byzantine civil war, he was deported to Tenedos by John VI Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Ángelos Palaiológos Kantakouzēnós''; la, Johannes Cantacuzenus; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under A ...

.

John V eventually claimed victory in the civil war, but the cost was significant debt, mainly to the Venetians. In the summer of 1369, John V sailed to Venice and apparently offered the island of Tenedos in exchange for twenty-five thousand ducats and his own crown jewels. However, his son (Andronikos IV Palaiologos

Andronikos IV Palaiologos or Andronicus IV Palaeologus ( gr, Ἀνδρόνικος Παλαιολόγος; 11 April 1348 – 25/28 June 1385) was the eldest son of Emperor John V Palaiologos. Appointed co-emperor since 1352, he had a troubled rel ...

), acting as the regent in Constantinople, rejected the deal possibly because of Genoese pressure. Andronikos tried but failed to depose his father. In 1376, John V sold the island to Venice on the same terms as before. This upset the Genoese of Galata. The Genoese helped the imprisoned Andronikos to escape and depose his father. Andronikos repaid the favor ceding them Tenedos. But the garrison on the island refused the agreement and gave control over to the Venetians.

The Venetians established an outpost on the island, a move that caused significant tension with the Byzantine Empire (then represented by Andronikos IV)and the Genoese. In the Treaty of Turin, which ended the War of Chioggia

The War of Chioggia ( it, Guerra di Chioggia) was a conflict between Genoa and Venice which lasted from 1378 to 1381, from which Venice emerged triumphant. It was a part of the Venetian-Genoese Wars.

The war had mixed results. Venice and her alli ...

between Venice and Genoa, the Venetians were to hand over control of the island to Amadeo of Savoy and the Genoese were to pay the bill for the removal of all fortifications on the island. The Treaty of Turin specified that the Venetians would destroy all the island's "castles, walls, defences, houses and habitations from top to bottom 'in such fashion that the place can never be rebuilt or reinhabited". The Greek populace was not a party to the negotiations, but were to be paid for being uprooted. The baillie

A bailie or baillie is a civic officer in the local government of Scotland. The position arose in the burghs, where bailies formerly held a post similar to that of an alderman or magistrate (see bailiff). Baillies appointed the high constable ...

of Tenedos, Zanachi Mudazzo, refused to evacuate the place, and the Doge

A doge ( , ; plural dogi or doges) was an elected lord and head of state in several Italian city-states, notably Venice and Genoa, during the medieval and renaissance periods. Such states are referred to as "crowned republics".

Etymology

The ...

of Venice, Antonio Venier, protested the expulsion. The senators of Venice reaffirmed the treaty, the proposed solution of handing the island back to the Emperor seen as unacceptable to the Genoese. Toward the end of 1383, the population of almost 4000 was shipped out to Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest ...

and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

. Buildings on the island were then razed leaving it empty. Venetians continued to use the harbor.

The Venetians were zealous guarding the right to Tenedos the Treaty of Turin provided them. The Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

wanted to build a fortification at the island in 1405, with the knights bearing the cost, but the Venetians refused to allow this. The island remained largely uninhabited for the next decades. When Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo Ruy may refer to:

Arts and Entertainment

*Ruy, the Little Cid, Spanish animated television series

*Ruy Blas, a character in the eponymous tragic drama by Victor Hugo

People

*another form of Rui, a Portuguese male given name

*another form of the S ...

visited the island in 1403 he remarked that because of the Treaty of Turin "Tenedos has since come to be uninhabited." 29 May 1416 saw the first battle at sea between the Venetians and the emerging Ottoman fleet at Gallipoli. The Venetian captain-general, Pietro Loredan

Pietro Loredan (1372 – 28 October 1438) was a Venetian nobleman of the Loredan family and a distinguished military commander both on sea and on land. He fought against the Ottomans, winning the Battle of Gallipoli (1416), played a leading role ...

, won, wiped out the Turks on board, and retired down the coast to Tenedos, where he killed all the non-Turk prisoners who had voluntarily joined the Turks. In the treaty of 1419 between Sultan Mehmed and the Venetians, Tenedos was the dividing line beyond which the Turkish fleet was not to advance. Spanish adventurer Pedro Tafur

Pedro Tafur (or Pero Tafur) (c. 1410 – c. 1484) was a traveller, historian and writer from Castile (modern day Spain). Born in Córdoba, to a branch of the noble house of Guzmán,He dedicated his manuscript to Don Fernando de Guzmán, Chief Co ...

visited the island in 1437 and found it deserted, with many rabbits, the vineyards covering the island in disrepair, but the port well-maintained. He mentioned frequent Turkish attacks on shipping in the harbor. In 1453, the port was used by the commander of a single-ship Venetian fleet, Giacomo Loredan, as a monitoring point to observe the Turkish fleet, on his way to Constantinople in what would become the final defense of that city against the Turks.

Ottoman period

Tenedos was occupied by

Tenedos was occupied by Sultan Mehmet II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

in 1455, two years after his Conquest of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

ending the Byzantine empire. It became the first island controlled by the Ottoman Empire in the Aegean sea. The island was still uninhabited at that time, almost 75 years after it had been forcefully evacuated. Mehmet II rebuilt the island's fort. During his reign the Ottoman navy used the island as a supply base. The Venetians, realizing the strategic importance of the island, deployed forces on it. Giacopo Loredano took Tenedos for Venice in 1464. The same year, Ottoman Admiral Mahmud Pasha recaptured the island. During the Ottoman regime, the island was repopulated (by granting a tax exemption). The Ottoman fleet admiral and cartographer, Piri Reis

Ahmet Muhiddin Piri ( 1465 – 1553), better known as Piri Reis ( tr, Pîrî Reis or '' Hacı Ahmet Muhittin Pîrî Bey''), was a navigator, geographer and cartographer. He is primarily known today for his maps and charts collected in his ''K ...

, in his book ''Kitab-i-Bahriye'', completed in 1521, included a map of the shore and the islands off it, marking Tenedos as well. He noted that ships heading north from Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

to the Dardanelles passed usually through the seven-mile strip of sea between the island and the mainland.